22. THE LATER 1960s

JOHNSON ATTEMPTS TO BUILD A "GREAT SOCIETY"

CONTENTS

The American presidency under The American presidency under

Johnson ... not quite Camelot!

The making of Lyndon Baines Johnson The making of Lyndon Baines Johnson

(LBJ)

The civil rights movement gains steam The civil rights movement gains steam

Johnson's "Great Society" program – Johnson's "Great Society" program –

May 1964

American politics takes a left turn under American politics takes a left turn under

Johnson

The continuing attempt to protect The continuing attempt to protect

religion from Secular-Judicial regulation

Race relations worsen Race relations worsen

Affirmative action also for women and Affirmative action also for women and

Hispanics as suffering "minorities"

The growth of the Federal state ... and The growth of the Federal state ... and

the Federal debt

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 171-190.

THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY UNDER JOHNSON ... NOT QUITE CAMELOT! |

|

The changing of the guard at the White House

Americans were stunned by the thought that they

had lost the very charming, very charismatic president who gave

American politics even within sophisticated Europe the reputation of a

quite high level of sophistication itself. But now Americans

awakened to the realization that with Vice President Johnson now as the

new U.S. President, that style was gone, very gone. Instead

Johnson gave off the appearance of being simply another Southern "good

old boy."

But appearances can be quite deceiving!

With the assassination of the young

President Kennedy in 1963, actually in Lyndon Baines Johnson

(LBJ) a quite sophisticated (in his own way) veteran of Capitol Hill

politics now assumed the Presidency. Lyndon Johnson's political goals

were similar to Kennedy's: a Liberal Democrat who emphasized the

importance of American civil rights and also one who understood that

Communism was still the greatest threat to America. However, his

political strategy and style in addressing these challenges to America

was drastically different.

The original expectation of "business as usual"

in the presidential changeover

At the time Johnson stepped into the

American Presidency, "government" meant the Americans themselves. The

state did not rule. The people ruled. A formal government consisting of

the people's representatives existed solely to service the people and

their general will, as the people themselves directed these

representatives (the power of the voting booth). The economy belonged

to the people as consumers and their private businesses that answered

their consumer demands. Educational policy belonged to the American

families and their local school boards. Health care belonged to

the people and their doctors.

National government was largely left only

to deal with international issues, as had been the intention of the

original Framers of the Constitution, and had largely been the pattern

since then.1

Of course, the Great Depression and then

World War Two had challenged deeply that view. During that time period

(the many years of FDR's presidency) the Washington political

Establishment had taken a very commanding position in American life.

But those periods were considered merely temporary, necessitated by the

extreme demands facing America in those days. It was also expected, and

indeed seemed to be the case, that when those emergencies were put

behind the country, it would then return to national business as usual.

Thus it was that going into the new

Johnson presidency, there was still little sense that the national

government in Washington had any important role to play in the nation's

domestic affairs. True, there was the huge domestic program, Social

Security, a pension fund for the elderly, managed by the national

government. But in this the Washington government was considered to be

only the caretaker of this huge pension fund, not the owner of

it. Social Security too belonged to the people.

In any case, there seemed to be little

reason under the new president for things to change in Washington,

other than simply a different personality now living in the White

House. There were no earth-shaking national crises that required a

dramatic shift in America's "business as usual." True there were issues

at hand, as always. Black civil rights was an issue needing national

attention. But Congressional politics, voicing the changing will of the

American people on this matter, was supposedly quite sufficient to

handle this matter. And as far as foreign policy was concerned, the

Cold War was still on, but not really much changed in character over

the recent years. And again, Washington's small but capable foreign

policy teams in the White House and Congress seemed more than able to

handle this challenge, as it had since the end of World War Two.

Thus it was that Americans, stunned by

the tragic loss of President Kennedy, nonetheless carried on, expecting

things to continue forward pretty much in a rather widely accepted

traditional manner.

But

actually, all this would all change – change drastically – during the

five years of Johnson's presidency. And this was because the new

president brought to Washington politics a very different understanding

of what "business as usual" was supposed to look like.

1The 10th Amendment – the famous "Reservation Clause" – concludes the Bill of Rights: The

powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor

prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States

respectively, or to the people. This meant that unless the

Constitution had specifically assigned powers to Congress to act in

certain matters, all other political activities were reserved to the

States and the people ... the federal counterbalance of the states in

"checking" the powers of the national government – against the tendency

of all ruling bodies to want to expand their powers at will. But such

checks on central (Washington, D.C.) power would be put aside during

the Johnson years.

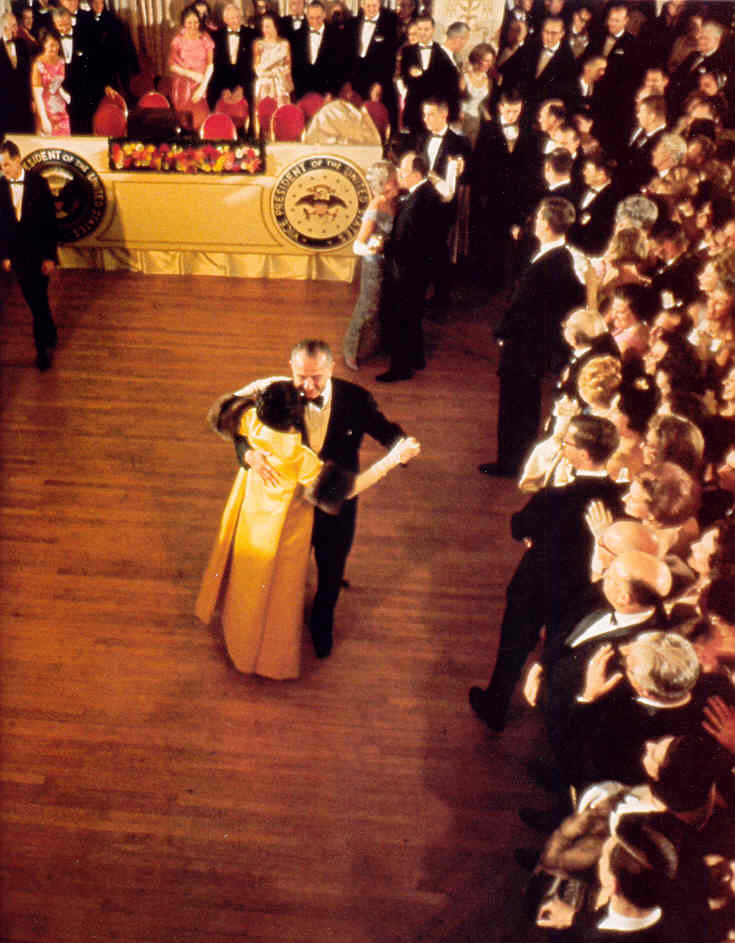

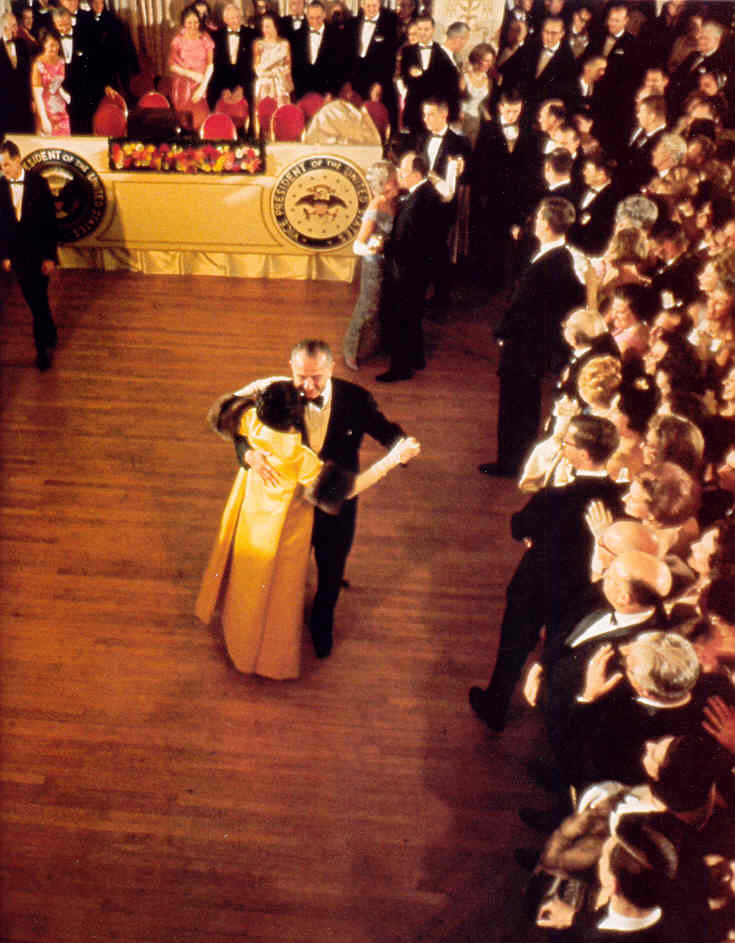

Nice ... but not quite

Camelot. Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson

dancing at LBJ's inaugural ball – January 20, 1965 (Vice President Hubert Humphrey

and his wife in the background)

THE MAKING OF LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON (LBJ) |

|

Johnson grew up on a farm in the tiny and

rather remote community of Stonewall, Texas, in a condition of constant

poverty and humble social circumstances, although his family had a

somewhat impressive history dating back to the early days of Texas. In

fact, the nearest town in the region, Johnson City, was named after one

of his relatives. The young Lyndon attended high school in Johnson

City, and eventually entered Southwest Texas State Teachers College in

San Marcos, where he developed a taste for politics and ended up as

editor of the school newspaper. He took time off during his studies to

teach a full school-year to Hispanic-American children, which touched

deeply an old nerve in Johnson, one that never failed to make him

greatly concerned about the problems that people face living in utter

poverty – something he personally could identify with closely.

Graduating in 1930, he found a position

teaching high school public speaking in Houston and also got involved

in Richard Kleberg's Congressional campaign. With Kleberg's victory in

late 1931, Johnson followed him to Washington, D.C., where he found

himself by natural impulse organizing Congressional aides into

something of a political fellowship. Eventually that fellowship would

include staff members of newly elected President Roosevelt. But it

would also grow to include even a direct friendship with Vice President

John Nance Garner and powerful Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, both

Texans. In fact, Johnson's relationship with Rayburn would grow over

the years, forming a strong political bond between the two.

In 1934 he married Claudia ("Lady Bird")

Taylor of Texas, whose mother (of aristocratic Alabama ancestry) died

when Ladybird was only five. Her father was a strong-willed Alabama

sharecropper who managed to move to Texas and put together a fortune,

coming to own 15,000 acres of cotton and two general stores. Growing

up, Lady Bird ventured back and forth between Texas and Alabama, but

eventually attended and graduated from the University of Texas, and

then headed on to Washington, D.C., where she met Johnson, marrying him

only ten weeks later.

In 1935 he returned to Texas to became

head of the Texas National Youth Administration, a big part of

Roosevelt's New Deal, given the task of setting up government-sponsored

jobs and job-training for unemployed Texas youth. This was a key

component of Johnson's understanding of the proper role of government,

one that would stay with him during the years ahead as he entered more

fully into political life.

In 1937, financed heavily by his wife, a very ambitious Johnson ran

successfully in a special Congressional election, and would continue to

serve in the U.S. House of Representatives during the next dozen years,

most importantly during World War Two, proving to be a key supporter of

Roosevelt's legislative agenda. He joined the U.S. Naval Reserve in

1940, was commissioned as a Lieutenant Commander, and when America

entered the war in December of 1941, he was called to active duty. He

wanted a combat appointment but instead was put to use by Roosevelt

during the early part of the war as an investigator into general

conditions of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, this leading him eventually

to be a chairman of a key subcommittee of the House Naval Affairs

Committee investigating navy contracts with America's manufacturers

(similar to Truman's role in the Senate investigating army contracts

during the same period).

After the war, in the 1948 national

election, Johnson ran for a U.S. Senate seat, gaining (very narrowly,

and very questionably) the Democratic Party nomination, and thus in the

Dixiecrat South (which included Texas) most assuredly the subsequent

election itself (Southerners at that time were still refusing to vote

Republicans to any office). Now in the Senate, Johnson was quick to

befriend the powerful Senator Richard Russell and also help create and

then lead a Senate subcommittee investigating government contracts with

the defense industry, very similar to the role he played in the House

of Representatives.

By 1951 he had gained the key position of

Senate Democratic Party Majority Whip. Then when in the 1952 elections

(which brought Eisenhower to the White House) the Republicans swept the

Democrats out of power in both houses of Congress, in the new Senate

political reshuffle in early 1953 Johnson was elected by fellow

Democrats as the new minority party leader. This made him the youngest

person ever to be elected to that powerful position (he was only

forty-four at the time). Then when in the 1954 elections the Democratic

Party regained the majority in the Senate, Johnson became the majority

party leader. This would make him not only one of the youngest but also

one of the most powerful leaders in Washington, D.C.

Johnson grew up in a family that had a

number of Baptist pastors in its recent genealogy on his mother's side

of the family, whereas his father had merely a distant relationship

with the world of religion, only occasionally attending the Disciples of

Christ (DOC, or just "Christian") Church in Johnson City. But it was in

this church that Johnson would grow up, a rather different sort of

denomination than the Southern Baptists and Methodists of the

camp-revival variety that dominated the local religious scene. The DOC

had been founded in the 1800s in an effort to create a Christian form

that adhered to no particular doctrinal or liturgical structure. And

this seemingly left its mark on Johnson, who in later years (really

only after he became president in late 1963) would find himself

comfortable in any of America's Christian denominations, even Catholic.

And he especially loved to find himself in the company of pastors, of

any variety. But actually, Johnson seemed to develop a preference for

the more liturgical (Catholic and Episcopalian) churches to attend,

although ultimately he could be wide-ranging in his choice of where he

would worship on any particular Sunday, sometimes even attending more

than one church on that same morning. Part of this was that he truly

felt at home within the broader spectrum of Christianity. But he also

liked to be out in the crowds (always hating to be alone). Of course

this never hurt his political status either. Also it kept him one step

ahead of the press, who naturally wanted the week's latest story on

where Johnson had attended church (he loved to keep the press guessing).

But clearly the one person who meant the

most to the president in the religion category was the evangelist Billy

Graham (whose contact with President Kennedy had been quite minimal).

Graham and Johnson became very close over the years of the Johnson

presidency. Graham was called on to speak at every one of the

presidential prayer breakfasts in those years, and Graham met

frequently with the president both in the White House and on Johnson's

Texas farm, to pray and offer comfort to a personal friend who was well

aware of the troubles his presidency had come to encounter. Johnson

even asked him in 1964 as to who he thought would make the best running

mate, to which Graham wisely declined to give an answer! Graham stayed

with Johnson the president's last night at the White House, and

eventually would be called on to conduct Johnson's funeral service

(1973). But very little of this close relationship was known outside

the inner Johnson social-political circle.

Johnson never saw the need to personally

inspire, through his own spiritual qualities, a "Christian America." He

did not usually talk about his religion publicly, or bring religion

into his public arena. Although he himself personally was a fairly

strong Christian, and found himself in personal prayer often over his

work, his public working-world was strictly Secular, and would remain

that way, even through all the difficulties he would face in trying to

lead the nation.

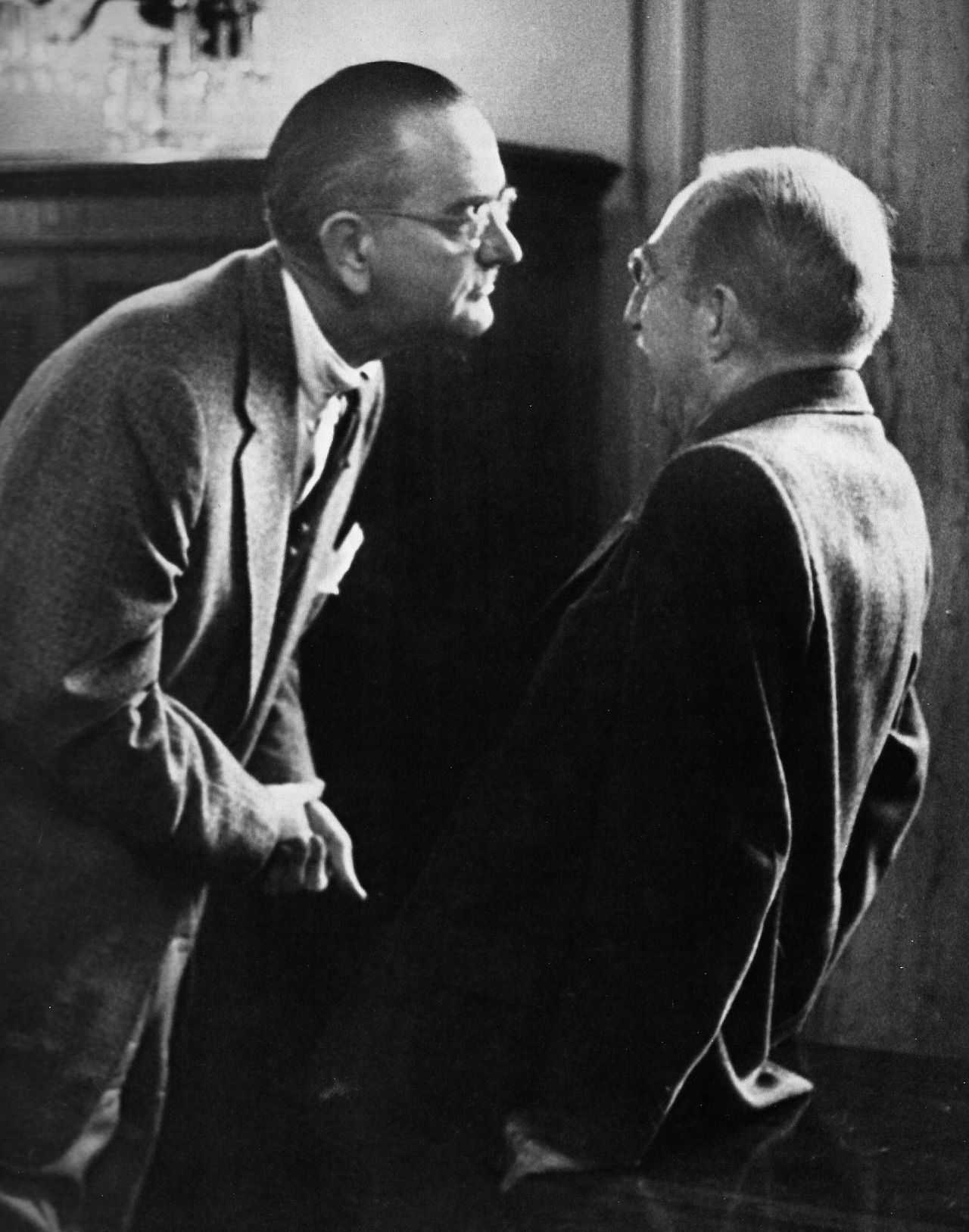

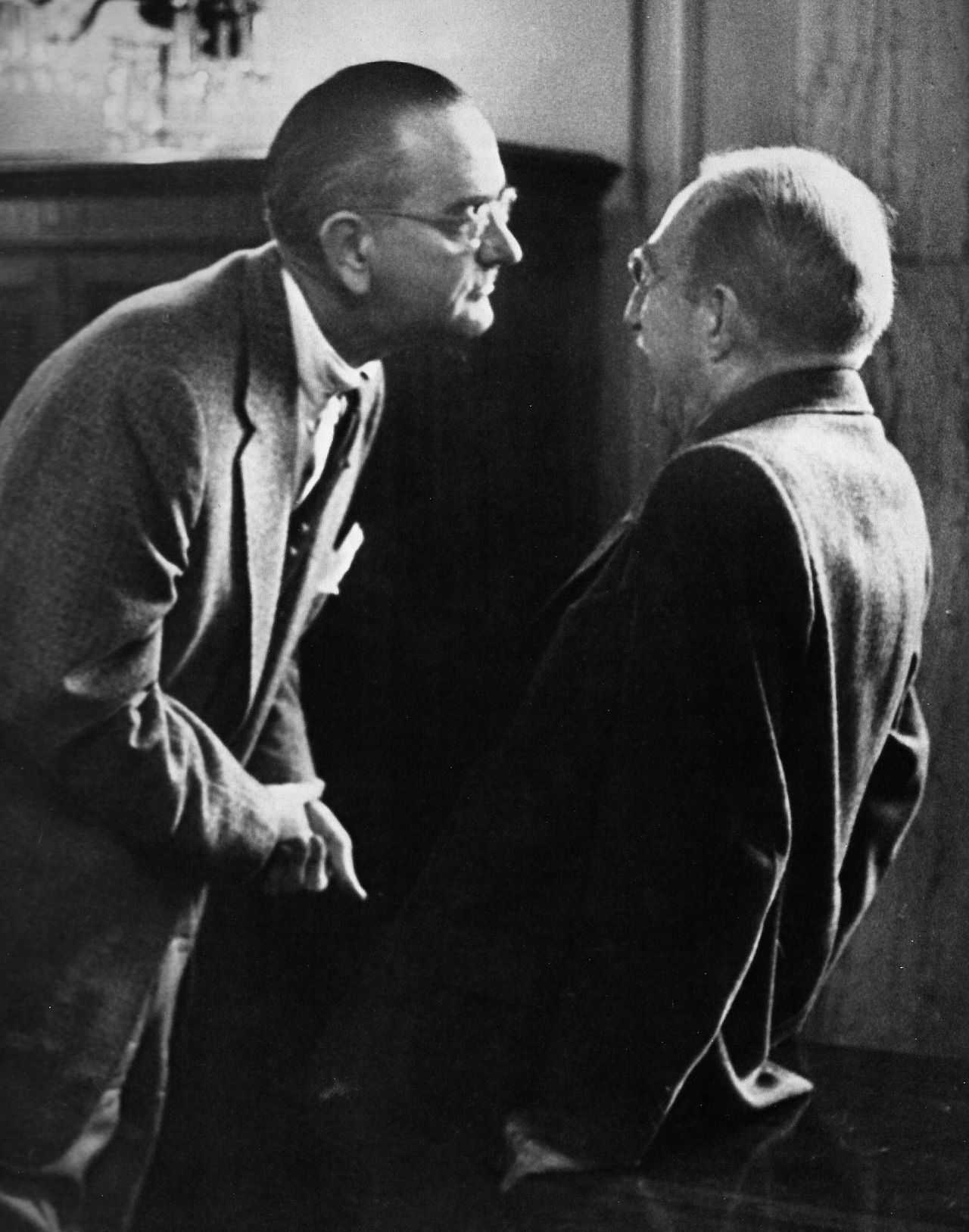

Johnson carefully researched every person

he would have to work with in Washington, finding their strengths and

weaknesses, their positions on various issues. Indeed, he was

well-known for his ability to go to work on his political colleagues,

towering over them hugely (he was a big man) in personal face-to-face

discussions, literally so, only an inch or two separating his face from

theirs as he pressed his views upon his intimidated victims.

He was very sensitive to the blemish of

poverty still afflicting the supposedly prosperous nation. Very

importantly in how he viewed this issue, he had come into the world of

politics as a young man deeply committed to Roosevelt's New Deal

program, and had a strongly ingrained sense that the government in

Washington was the best source of solid political, economic and social

reform for the nation – despite whatever the Constitution had to say on

these matters.

Also, as a Southerner, personally stung

by the way fellow Southerners had dug in their heels against Black

civil rights, he was by no means convinced that a mere appeal to the

American conscience was sufficient to get Americans to do the right

thing. Thus to Johnson it seemed to make more sense to him, on a number

of different political fronts, that real reform had to come to America

by way of a strong central authority, namely the Washington government

that Johnson had come to know quite well.

Besides, he was well-aware of the fact

that he lacked the personal qualities that could charm the American

people to action like Kennedy. He did not have a charismatic

personality that could move the public like King. No, he was a

behind-the-scenes political maneuverer – a very effective one at that.

He could get things done in Washington that not even a Kennedy or a

King could achieve, because of the huge amount of personal political

leverage he had developed in dealing with the other members of Congress

as Senate minority and then majority leader.

Johnson was also one very impressed with

professional credentials, ones that distinguished the experts of

Washington's powerful political circles from the common folk back home.

He was very definitely a deeply committed "Washington insider," as few

U.S. presidents before him had been.

Thus he would eventually come to put

forward his Great Society idea, a set of government programs run out of

Washington by political professionals, which he felt was the most

effective way to bring America to perfection. To Johnson's way of

thinking, professional economists, public administrators, lawyers,

etc., brought to Washington to engage in their professional work and

duties, seemed by far to be the best way to get the job done of

perfecting America.

So it was that Johnson pursued American

politics not along the lines of great idealistic challenges to equally

idealistic (and socially self-motivated) Americans, as Kennedy had, but

more in terms of an aggressive out of sight herding forward of the

Washington congressional and executive bureaucratic machinery. He

relentlessly pushed forward his political program of social reforms

through this Washington political machine – expanding it to rather

colossal proportions in the process.

Under Johnson, Washington D.C. transformed itself into a great imperial

metropolis – also improved greatly in appearance through his wife Lady

Bird's huge efforts to make the capital appear indeed to be just such

an imperial metropolis.

|

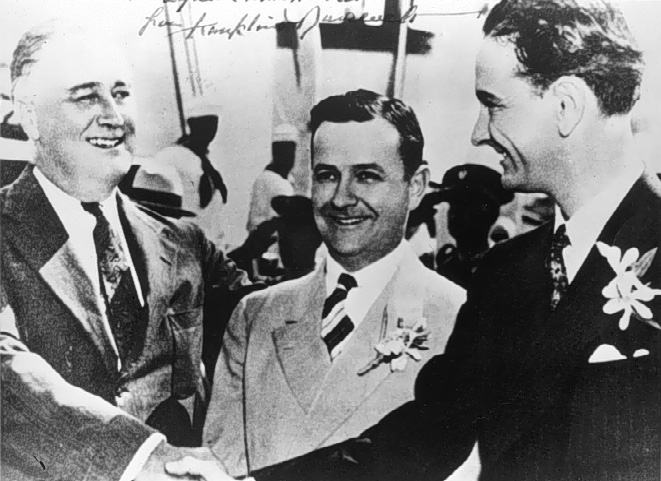

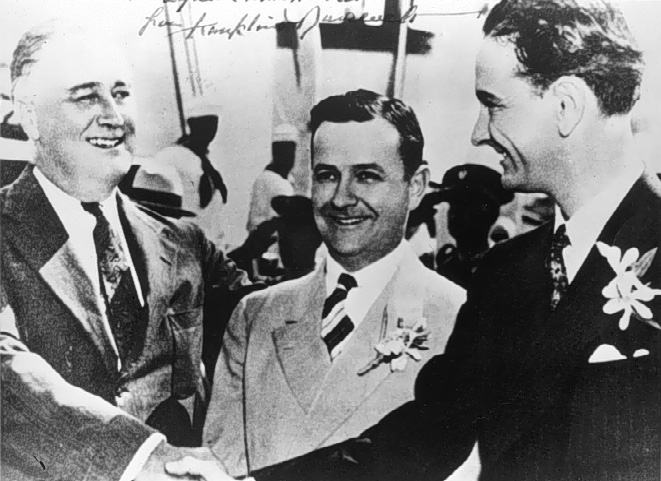

1937 – President Roosevelt, shaking hands with LBJ ...

with Texas Governor James Allred between the two men

1942 – LBJ in his naval uniform

Johnson with Lady Bird and their two daughters – 1948

Johnson as U.S. Senator from Texas

Senator Green getting the "Johnson Treatment" – 1957

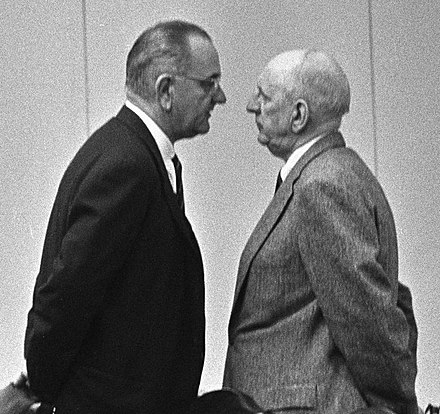

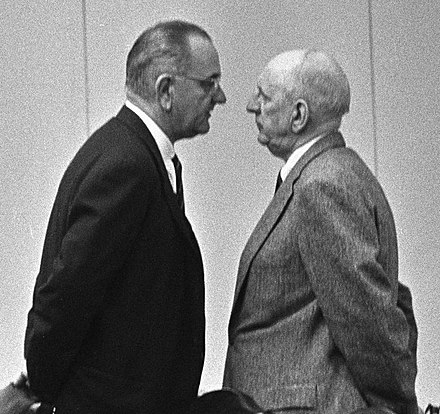

Sen. Russell having a heart-to-heart (or nose-to-nose) talk with Johnson! – 1963

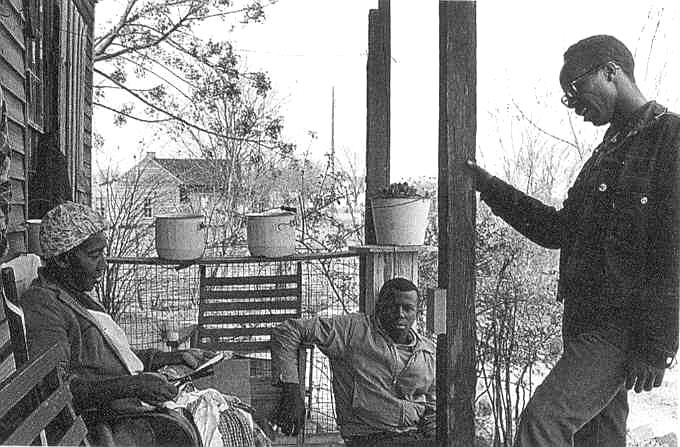

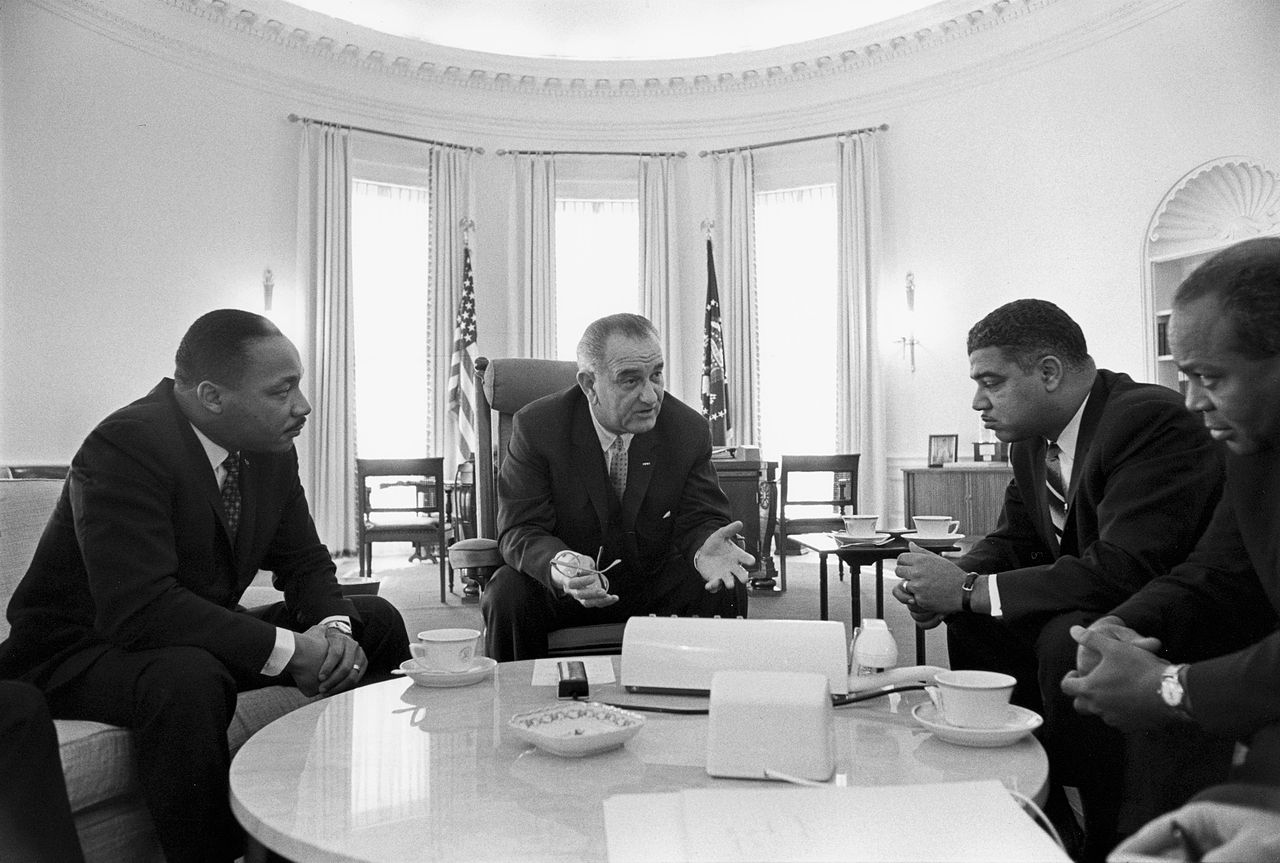

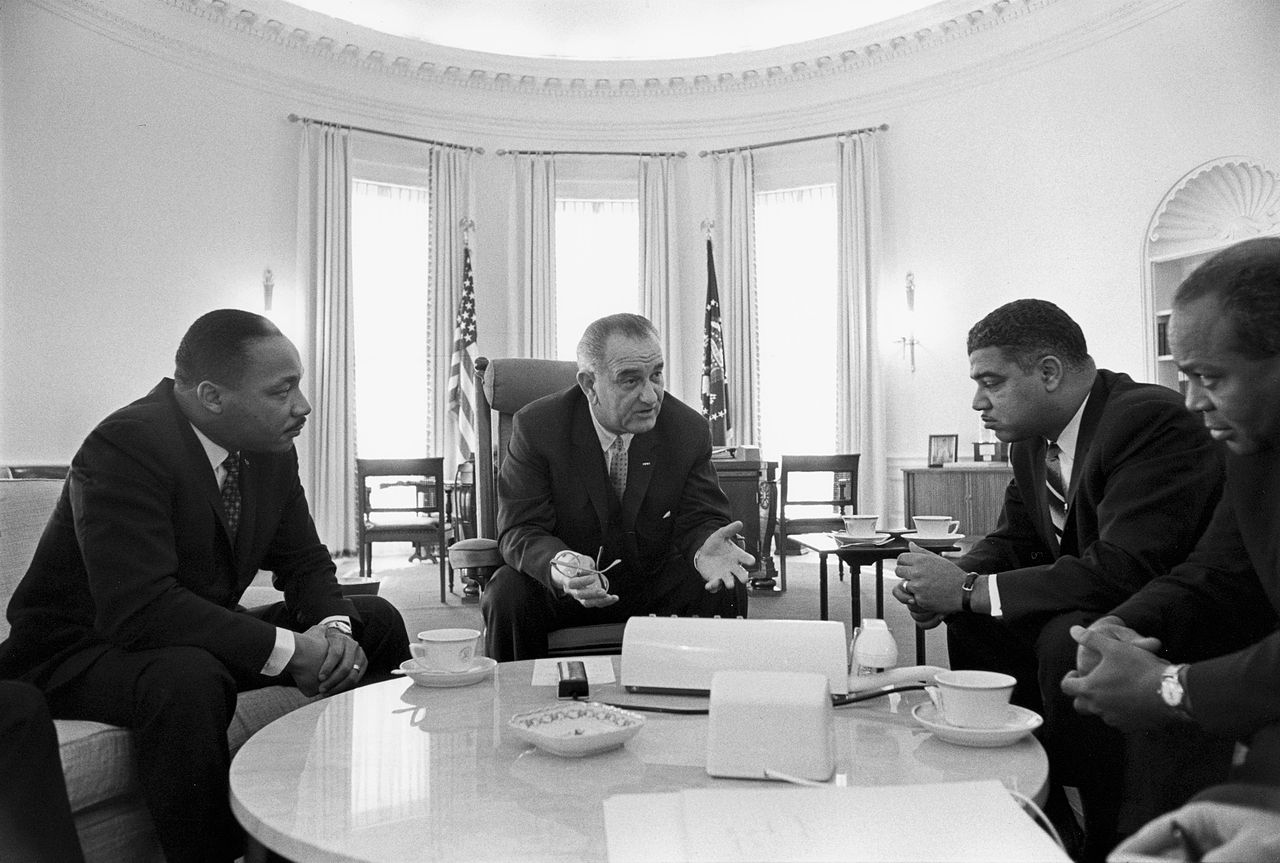

Johnson in discussion with civil rights leader Whitney Young – 1966

THE

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT GAINS STEAM |

With strong encouragement

from President Johnson, the civil rights movement gains steam – but not without some tragic

moments along the way

|

In Cold War terms, what Johnson was doing seemed

at the time to make great sense. To win the ideological struggle with

international Communism, America was truly going to have to shine. It

would have to conduct a war of its own on any American social blemish

that the Communists might pounce on as a way of embarrassing America,

thus advancing the Communist cause. No more cruel treatment of racial

minorities. But also, no more pockets of poverty, of illiteracy, of

poor health anywhere in America.

"Civil rights" thus began to take on a

broader social definition – not just legal voting rights empowering

individuals to move unrestrictedly in shaping their own personal

destinies, but the rights of everyone in America to enjoy the full

blessings of American citizenship, blessings placed in their hands by a

caretaker government operating above them. These were their

"entitlements" as Americans. And the political machine that Johnson

directed in Washington D.C. was going to be a center of command that

would bring this new system of social entitlements into existence. This

political machine was to be the means by which Johnson's Great Society

would be built.

|

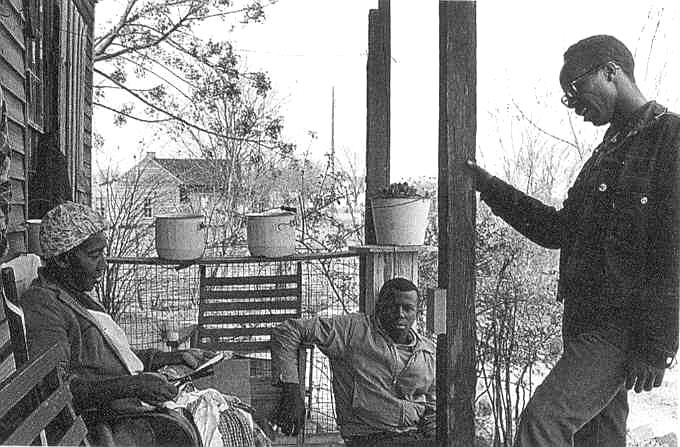

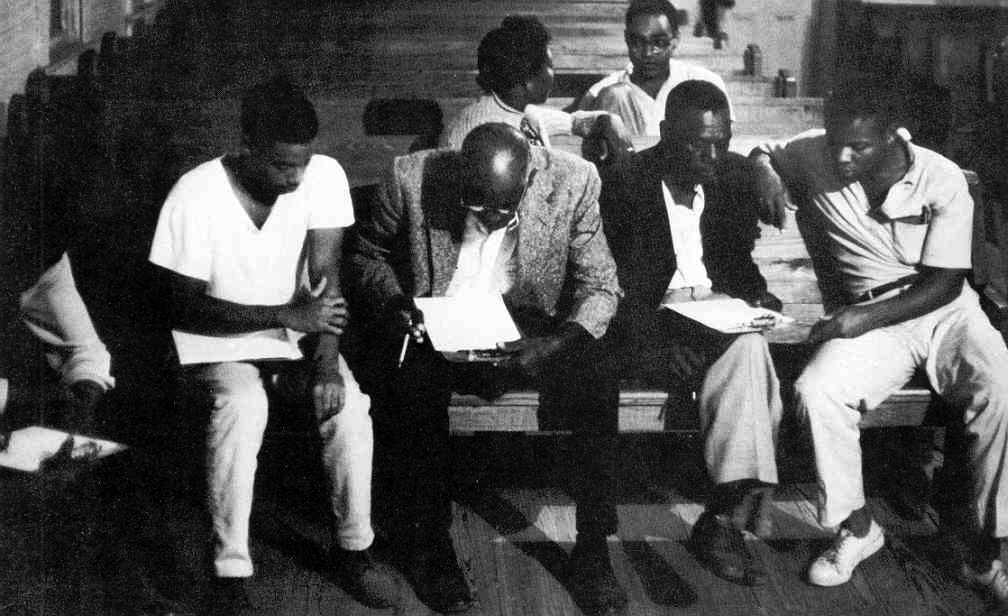

A SNCC worker in Mississippi

during the "Freedom Summer" campaign – 1964

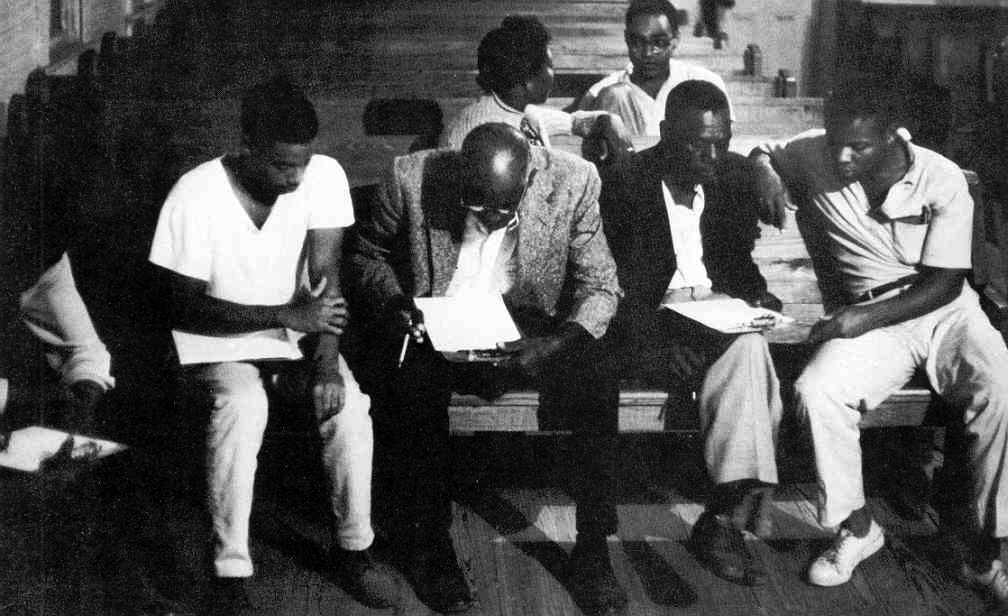

A SNCC-conducted voter

registration

in the South – early 1960s

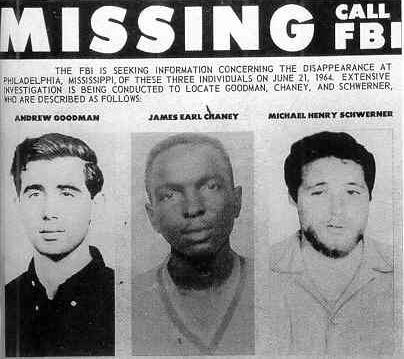

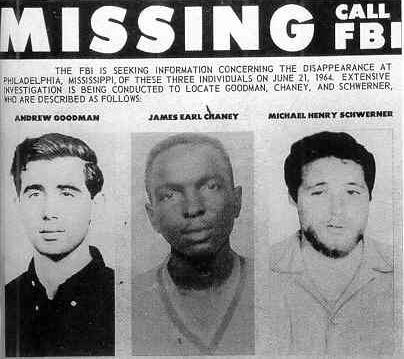

Three civil rights workers

missing in Philadelphia, Mississippi, on June 21, 1964 – whose bodies were

found on August 4.

The Chaney family at James'

funeral

The Chaney family at James'

funeral

Mississippi sheriff Lawrence

Rainey (right) and deputy Cecil Ray Price on trial for the murder

of the 3 civil rights workers – 1967

Nonetheless despite, and

perhaps because of, Southern excesses, Johnson got Congress

to finally

move on a Civil Rights Bill (1964)

promising equality of treatment of all Americans

in a number of different

areas:< voting, schooling, workplace,

public eating

and entertainment place, etc. discrimination

President Johnson signs the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law

Cecil Stoughton, White House

Press Office

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

receiving the Nobel Peace Prize – 1964

But having a Federal civil

rights law on the books, and getting people to abide by it, are still two different

things in the South. Consequently the struggle

continued:

The March from Montgomery to Selma Alabama – March

1965

Martin Luther and Coretta

King leading a march in Selma, Alabama, demanding Black voters' rights

March 1965

Martin Luther King and 25,000

marchers from Selma to Montgomery – March 1965

Police outside of Selma,

Alabama, attempting to stop a civil rights march across the South,

March

7, 1965

Alabama state troopers attacking

civil rights demonstrators on a Selma-to-Montgomery walk

March 7,

1965

And yet the Blacks began

finally to make considerable strides forward toward equality

President Johnson, the Rev.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks at the signing of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965 (August 6)

This measure attacked the

Southern practice of finding unique ways of disqualifying Black voters

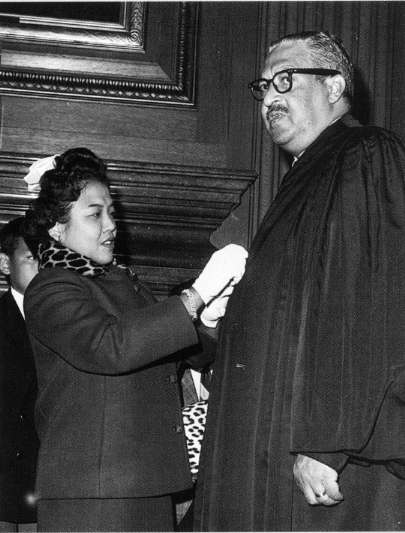

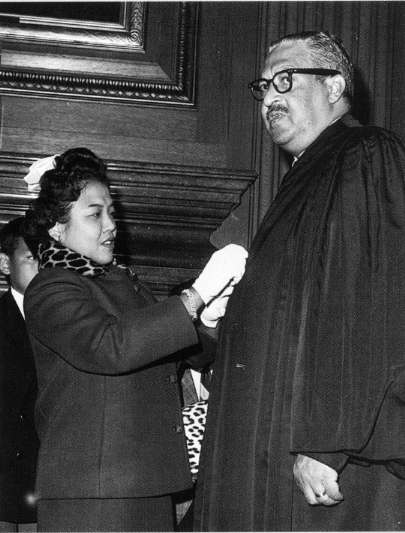

Thurgood Marshall – first

Black member of the US Supreme Court – and his wife Cecilia

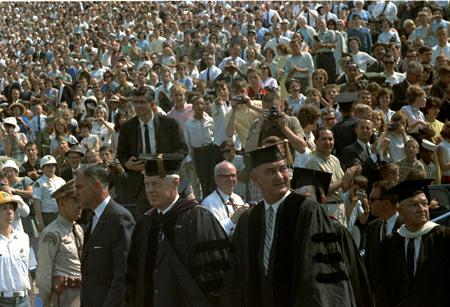

JOHNSON'S "GREAT SOCIETY" PROGRAM |

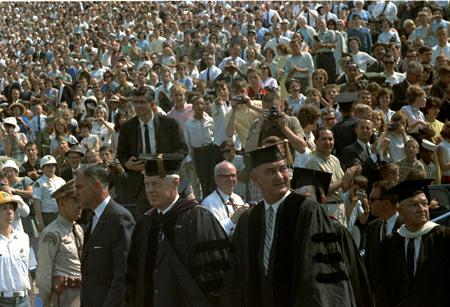

LBJ at the University of

Michigan, May 22, 1964 –

announcing the outline of

his "Great Society" Program

LBJ Library – University

of Texas

|

What Americans did not understand at the time was

that they were handing their political powers, the basis of American

democracy, over to a professionally-run state, which would then govern

autocratically – because supposedly (at least as members of this

autocracy themselves believed) this enlightened super-state was in a

better position to deliver the goods for the Americans than supposedly

they could do this for themselves. Thus Americans began to find

themselves falling into a state of dependency on the powers of

Washington and its officers.

Tragically, this was the same understanding that ancient Republican Rome2

moved to when it transferred the power of the people over to the

efficiently-run Roman legions, with the presumption that this would not

only better serve Rome, but would also better serve the Romans

themselves. And thus the Roman Republic had become the Roman Empire.

And with that, Roman society would fall into a moral laziness, one that

even eventually infected the autocratic leaders that Rome looked to for

correction and guidance.

What America did not know at the time was that they were about to make the same bargain with the powers-that-be in Washington.

Johnson's "Great Society" program

On May 22, 1964, standing before students

graduating from the University of Michigan, Johnson announced the

particular details of his new Great Society program that he was about

to launch. He began by explaining how through invention and

industriousness America had progressed over the generations to being a

rich and powerful society … but how today

we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.

He

explained that the Great Society would dedicate itself not only to

ending all poverty and racial injustice in America but also to

improving the realm of American education and professional development,

to protecting the country's natural beauty, and to reshaping America's

rapidly developing urban life.

More particularly he stressed, first of

all, the importance of rebuilding an even stronger urban America – not

only materially in the face of such challenges as offering housing for

all, containing suburban sprawl, and improving urban infrastructure,

but also in developing a stronger sense of community within urban

America. He claimed literally that we needed to rebuild the entire

urban United States over the next forty years.

Secondly, the Great Society would look to

the preservation of America's beautiful countryside – threatened by

pollution, overcrowding and the disappearance of its fields and forests.

And thirdly, the Great Society would

ensure that all young Americans were given the opportunity for a

complete education, in high school and college. This required better

teacher training and the development of the love of learning among

America's youth.

Those three items, urban development,

protection of the countryside and the improvement of American education

formed the heart of his New Society proposal. And how was all of this

going to be brought to fulfillment?

Johnson stated:

While our Government has

many programs directed at those issues, I do not pretend that we have

the full answer to those problems.

But I do promise this: We are going to assemble the best thought and the

broadest knowledge from all over the world to find those answers for

America. I intend to establish working groups to prepare a series of

White House conferences and meetings on the cities, on natural beauty,

on the quality of education, and on other emerging challenges. And from

these meetings and from this inspiration and from these studies we will

begin to set our course toward the Great Society.

The solution to these problems does not rest on a massive program in

Washington, nor can it rely solely on the strained resources of local

authority. They require us to create new concepts of cooperation, a

creative federalism, between the National Capital and the leaders of

local communities.

"Democracy from above" by socio-economic technicians

This was a very technical vision Johnson

laid out. It would require special expertise to devise answers to these

social challenges. Johnson made it clear that he would have to assemble the best thought and the broadest knowledge from all over the world

to find those answers for America. The work involved would be done by

White House conferences and meetings. In other words, the inner circle

of power located in the nation's capital would govern this effort to

build America's Great Society.

Johnson claimed that the solution to these problems did not rest on a massive program in Washington but required a creative federalism

between the National Capital and the leaders of local communities. How

he planned to broaden the circle of involvement beyond the White House

conferences and National Capitol meetings, however, he did not explain.

And in the end his Great Society indeed would rest on exactly that – a

vast array of massive programs coming out of Washington, and that alone.

This was a very different definition of

American government than what the nation had been used to. Americans

had accepted this role of a towering central authority during the

horrible years of the Depression and World War Two – as a matter of

grand necessity. But where was that compelling necessity now, something

as dire as a Great Depression and a World War afflicting America – and

thus forcing the nation to look to its national leaders for social,

economic and political solutions? Why this need in today's world for

massive government planning and social control?

But Johnson would effectively use the

powers of the presidency to shift the idea of American government very

strongly in the direction of his own thinking.

And he would take his Democratic Party along with him in this reshaping of America's political dynamics.

America's "government" was now to be

found in Washington, D.C. – not in Omaha or Topeka or Dallas or Denver,

or any of the thousands of small towns across America, or the homes of

the people living in those towns. Under Johnson, it was Washington that

now governed America – and would continue to do so now that Johnson's

technocracy ("government by technical experts") was well in place. No

one was ever going to change America's new political profile.

2It

was also the same mistake that ancient Israel made when it ended its

direct dependency on God and instead placed its dependency on a ruling

monarch – much like the rest of the ancient world. That would briefly

bring Israel great glory – and then soon thereafter the beginning of

its tragic decline.

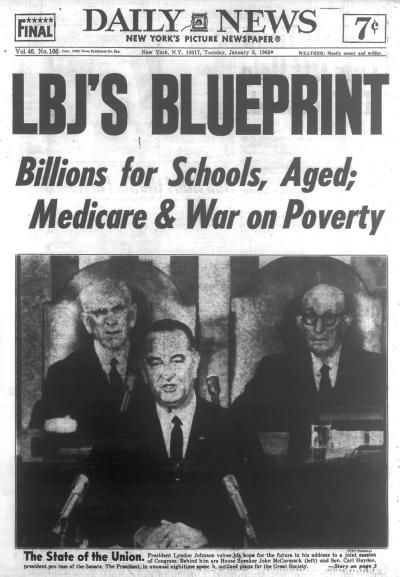

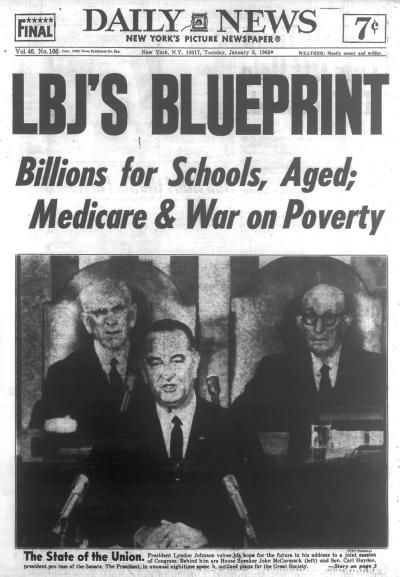

January 1965 – Johnson in his State of the Union address before Congress details even further the content of what he wants to see take shape as his "Great Society" program

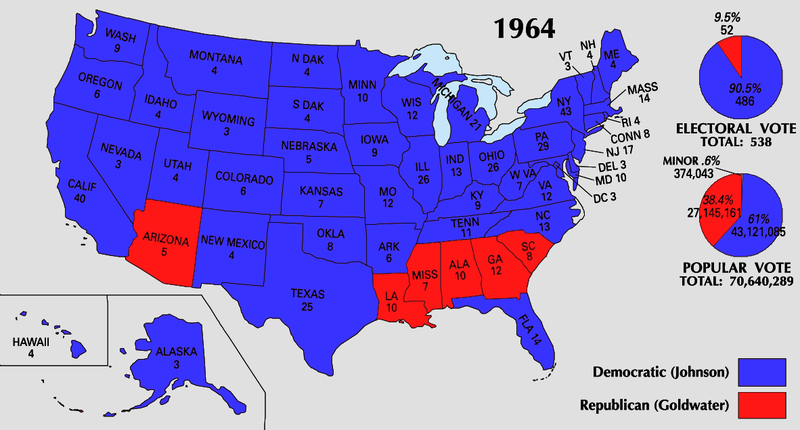

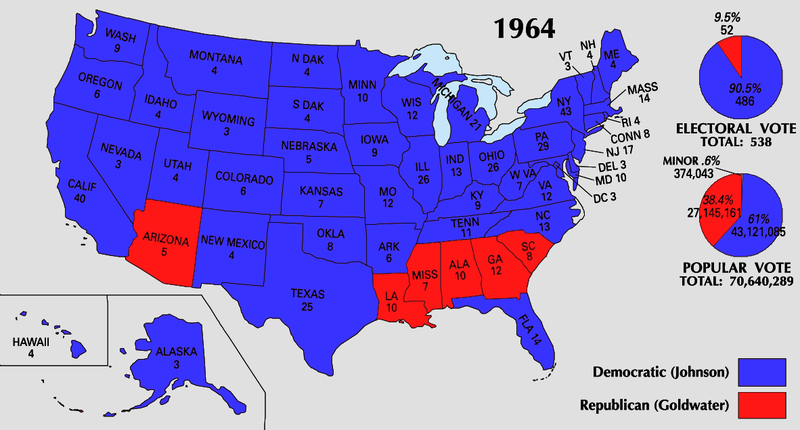

AMERICAN POLITICS TAKES A LEFT TURN UNDER JOHNSON |

Nov. 1964 – Johnson is elected overwhelmingly to the

Presidency

and holds that position now by his own right

|

The cultural split between the Republican and Democratic Parties

Johnson would rebuild the Democratic Party around

his Big Government vision (some would say "Big Brother" vision, as in

the Orwellian understanding of the term). Ultimately this would serve

to deepen immensely a growing cultural split separating not just

American Blacks and Whites, but also the very Christian middle-class

and very Secular intellectuals. It would also separate the rising

generation of Boomers, and their Vet parents.

One side in this split, now represented

by the Republican Party were the White, Christian Middle Class Vets,

who would become very suspicious of this rapid growth of Washington's

powers, seeing "government" taken from their hands and transferred to

an unchecked Washington bureaucracy – and an equally activist federal

judiciary.

On the other side of this split, now

represented by the Democratic Party, were those social groups, the

"minorities" (or later, "victim groups") as they saw themselves, whom

the Great Society was especially designed to promote. In particular the

Democratic Party enlisted the voting support of Blacks, who clearly had

fallen well behind White society in their ability to work themselves

upward economically and socially. According to the Democratic Party,

Blacks would need a lot of "affirmative action," that is, special

governmental support to compensate for and ultimately eliminate the

disadvantages they experienced in their quest for social status and

cultural importance. They were "entitled" to such special treatment

(federal government programs3)

because of prejudice they and their ancestors had experienced at the

hands of White racism, supposedly now identified with the "privileged"

White middle-class Republican voter. In taking up this line of racist

thinking they conveniently overlooked the fact that it was young White

males who fought and died by the hundreds of thousands in the 1860s

(America's Civil War) so that their Black ancestors might be set free

from the scourge of slavery.

But the category of "minorities" would

come also to include women, some women anyway, at least those who

tended to feel that the professional world (dominated by men) was more

important for them and their futures than the traditional world of

family – and thus would see men as their adversaries rather than as

colleagues in life as they pushed ever deeper into the professional

world.

To this list would also be added gays and

lesbians, Hispanics, American Indians – and even intellectuals

(professors, journalists, media celebrities), soon joined by

college-aged Boomer youth very ready to undertake a great crusade

against the "Establishment" of White, Protestant and "straight" males.

"Democracy" takes on a new meaning

The second half of the 1960s would thus

become a time of massive (and frequently quite violent) change in the

very character of American democracy. "Democracy" would still refer to

the ideal of whom the government served ("the people"), but it would no

longer refer to the ideal of who it was that actually directed such

service. Government would take on the character of rule more by elitist

decree and less by popular consent and active support. Increasingly

"the government" would become less and less the public will and more

and more the will of professional politicians filling the growing ranks

of unelected (and virtually unremovable) officials directing the very

expensive and very expansive federal bureaucracy ... and the equally

expansive (in terms of political-cultural scope) federal judiciary.

But supposedly such government by the legal and technical experts would "progress" greatly the democratic character of society.4 But Marxism-Leninism (Communism) also made the same claim.

And indeed, Johnson's Great Society

program involved a distinct move toward Socialism and away from the

Puritan-founded grass-roots democracy that had been the very political

foundation of America, at least in the American North and West, and

with the outcome of Civil War a century earlier, becoming finally the

political ideal of all the country.

Now under Johnson's skillful political

management, the Democratic Party would identify itself as the party of

the "Liberals," meaning (in other social contexts such as that of

Europe) the "Socialists." Furthermore, most of Johnson's work would

remain intact after his departure from office at the beginning of 1969,

to the extent that the massive buildup of government officialdom in

Washington, D.C., and the governmental financial debt that went with

it, not only remained in place but would continue to grow in the years

ahead – a social dynamic carefully defended and protected by the mass

of political technicians making up this huge and unshakable Washington

Establishment.

"Liberal" intellectuals retake the cultural high ground in America

American intellectuals had been under

fire during the 1950s as being questionably patriotic because they did

not adhere closely to the American Middle-Class cultural system so

dominant everywhere in the nation. Now in the 1960s – with memories of

World War Two and the considerable sacrifices that Middle America

undertook to save the nation now fading from view – these alienated

intellectuals saw their chance to retake what they thought was their

natural position as national leaders. Intellectuals now saw before them

the rise of a newly emerging political culture, one directed not by

middle-class citizenry but by professionals from the upper or

"high-brow" reaches of American culture. Not only were these American

intellectuals detached from middle-class values, they were strongly

opposed to them and sought their removal from the central position in

the American culture that they had occupied for centuries.

Now a newly rising federal state provided

a particularly useful place for them, as trained social managers, to

put their new cultural revolution into effect (the nation's press and

universities being additional platforms from which to conduct this same

intellectualist revolution).

A cultural split within American academia

A result of this gathering social shift

in the 1960s was a huge battle which also began to develop at this time

in the various social science departments (sociology, economics,

political science) of America's universities. This battle pitted a body

of rising "social scientists" against the old guard of professors who

approached their subjects on a rather historical/philosophical basis.

This rising group of quite idealistic scholars were typically the

younger members of the department, very optimistic about their "social

science" that they intended to bring to the study of society, and very

contemptuous of the old-fashioned approach to the subject pursued by

the older members of the department. These older professors had long

approached the study of politics more as a matter of narrating

historical events which offered not only a laboratory of social

examples to draw lessons from but also moral or inspirational insights

into political behavior in general. But for the newly rising group, it

was time to move past such an antiquated methodology.

The younger academics called themselves

"Behaviorists," taking cues from the science of psychology which

claimed to be making tremendous progress through the new behaviorist

theory in putting human behavior under experimental laboratory analysis

(with marvelous mathematically precise results that could be presented

as statistical charts and graphs), and thus under better control by the

doctors of psychology.

The young social scientists had the same

vision: to approach the study of social dynamics from a rather clinical

or experimental angle. Obviously, however, no one can put an entire

society under a carefully-controlled laboratory experimentation. So

what they proposed to do was to uncover great social truths by

conducting carefully-controlled experiments in small-group social

behavior. But how they exactly planned to expand small-group theory to

serve mass-group theory (the dynamics are actually quite different) was

never explained – nor for that matter ever discovered. But these young

idealists had not yet advanced to the stage of confronting such social

reality quite yet. In fact, they were not in a hurry to get there

either!

Nonetheless, they were religiously

certain that they would eventually uncover the truly scientific (purely

"mechanical") principles of the behavior of whole societies, principles

that would allow the doctors of society to better control society's

dynamics – in order to institute proper political-social-cultural (even

intellectual and spiritual) reform of society, the very kind of

approach that Johnson's Great Society Program was calling for. Indeed,

these young and energetic academics were looking forward to the

opportunity to become consultants, or even full-time directors in the

building of this new Great Society. They were quite certain that their

new "social science" would allow them to manage society on a much

better basis, ending the haphazard traditional approach which seemed to

them to offer little of substance in the effort to perfect society.

These young Behaviorists took their

inspiration from their ranks of young economists, already being trained

and prepared to manage not only business firms or corporations but the

financial and industrial systems of entire countries (and the rising

international economic system led by American capitalism). The young

Behaviorists of all social studies fields were certain that they could

soon achieve in their own social studies fields the goal of developing

something equivalent to Samuelson's Economics, the economics textbook

of the 1960s found in virtually every American university (and many

European universities as well). Samuelson's textbook was a virtual

manual on good economic management. It offered charts, graphs, tables,

algebraic formulae that seemed to cut through the mystery of wealth and

its creation and distribution, making economics truly a science.

Supposedly such precise, mathematically-derived insights into

economic behavior could finally solve not just the problems of

the rise and fall of market trends, but the very matters of wealth and

poverty themselves. Economists (who flocked to Washington in huge

numbers) were certain that they possessed the factual foundations to

truly bring the Great Society into being – a society of vast prosperity

and economic justice.

From the point of view of the other

experts in the fields of the new social science, this could, and

should, be done in their social-intellectual disciplines as well. They

were also going to make their contributions to the prosperity and

justice that awaited the development of the Great Society.

And indeed, as it turned out, they would

soon (very soon) have a front seat in observing exactly how all this

new "science" was going to bring America to the state of social

perfection.

3The

Democratic Party's extensive government programming – which gave the

multitudes of new government "experts" their jobs as well as their

sense of political importance – made this army of technocrats also

major supporters of the Democratic Party. Republicans who came to

Congress to cut back on the nation's massive governmental expansion

would thus automatically find themselves opposed, even effectively

undercut, by their natural opponents in Washington's technocratic "deep

state."

4Actually,

this was not a new interpretation of "democracy." It paralleled quite

closely Wilson's and FDR's understanding of the concept as well.

THE CONTINUING ATTEMPT TO PROTECT RELIGION FROM SECULAR/JUDICIAL REGULATION |

|

Increasing "judicial activism"

And the federal judiciary would also get drawn

ever more deeply into this new political attitude. Regional Circuit

Court and national Supreme Court Justices would take up the cause of

legal progressivism over the objection of a smaller group of

"originalists" in the judiciary who were opposed to such a development.

Judicial activists would not merely sit in judgment of the proper

application of the law, but move to reshape those laws, even laws

properly passed by Congress and signed into law by the President, when

various federal judges felt that circumstances warranted a more

"progressive" application of those laws.

In short, the federal judiciary was

becoming not only the Supreme Court but also the "Supreme Legislature"

of the United States, with no known checks available to block such

judicial overreach, except for (usually, Republican) Presidents to

appoint more originalists to the bench whenever vacancies occurred.

Thus the battle in the U.S. Senate over confirming new presidential

appointments to the federal judiciary would become increasingly bitter

as America moved down the road of judicial activism. The very idea of

American democracy was at stake in those appointments.

A second effort to protect religion from Federal regulation

With Representative Celler's success in

undercutting the momentum of the Becker Amendment in the House, the

Congressional effort to back the Supreme Court off its anti-prayer,

anti-Bible-reading position in public education now moved to the

Senate. In March of 1966, the Republican Party's Senate Minority Leader

Everett Dirksen of Illinois took up the cause by introducing in the

Senate a constitutional amendment (the Dirksen Amendment) similar to

the failed Becker Amendment.

In the time period since the failure of

the Becker Amendment, Christian denominations had continued to struggle

in deciding where exactly they stood on this matter of prayer and

Bible-reading in their schools.

In general, the denominational leaders and national officials still

seemed opposed to any such Amendment, continuing to claim that the

Court was actually trying to protect the right of prayer and

Bible-reading in America, not undercut that right. But clearly the

Christian rank-and-file laity were seeing things quite differently.

Even the Baptists, with a long history of wanting to keep the affairs

of religion and state entirely separate in order to protect their

religion (not protect the state), found themselves drawn into this

controversy as well. At their 1964 summer meeting, delegates to the

Southern Baptist Convention argued heatedly over the matter, finally

finding a compromise – which probably resolved nothing on the matter.

Over the next months the issue simmered

on the back burner, as other issues (civil rights, Johnson's Great

Society Program, the Vietnam War) received most of the country's focus.

But by 1966, Congressmen were receiving so many letters of Americans

still concerned about the matter of prayer and Bible reading in their

schools that Dirksen (after having helped put much of the civil rights

legislation through to successful adoption) turned his attention to

this religious matter, he himself being a very strong believer in the

importance of prayer in the life of America and its people.

Debate in the Senate followed typical

Liberal-Conservative lines, as outside groups also lined themselves up

for or against the Dirksen Amendment:

Nothing

contained in this Constitution shall prohibit the authority

administering any school, school system, educational institution or

other public building supported in whole or in part through the

expenditure of public funds from providing for or permitting the

voluntary participation by students or others in prayer. Nothing

contained in this article shall authorize any such authority to

prescribe the form or content of any prayer.

Debate

swung back and forth as the Senators attempted to fathom the extent of

national support or opposition to this amendment. Once again, tending

to oppose any such amendment were most of the denominational leaders,

their voices presented strongly through the organization of the

National Council of Churches. On the other hand, the massive number of

letters sent to Congress indicated a very strong support of the

amendment by the laity, though exactly what percentage of the laity

(including local clergy) was in favor of the amendment was never a

clear matter. Certainly there seemed to be a majority in favor of the

amendment. But how big was that majority?

In

September of 1966 it was time simply

to bring the matter to a vote before the full Senate. The results were

49 in favor (nearly all Republicansand most of the Southern Democrats)

and 37 opposed (3 Republicans and the rest Democrats) to the amendment.

5 Failing by nine votes to gain the necessary 2/3rds vote for a constitutional amendment, the matter died.

But the moral-spiritual division that had

developed over this this issue of prayer (and the place of God) in the

development of America's future generations did not die. It merely

clarified how deeply the nation was split on a matter of fundamental

importance to its very moral-spiritual character.

5Still

to this day it is not clear why the Democrats are so readily opposed to

the role of Judeo-Christianity in the life of the nation.

Senator Everett Dirksen

BUT IRONICALLY, RACE RELATIONS SEEM TO WORSEN RATHER THAN IMPROVE WITH AMERICA'S REFORMS |

|

The Blacks' "Revolution of Rising Expectations"

\Also at this same time another major shift in the

American cultural profile was taking place, this one within the Black

community. Young Blacks were growing more radicalized as shifts in the

racial status quo began to occur. Despite quite visible progress in

getting a cultural shift moving in America – one attempting to make way

for Blacks to come into full and equal participation in American

society – it was never fast enough for young Blacks. This rising group

of young and quite militant Blacks was beginning to voice its deep

hostility to the White society around it, a White society that it

claimed was still standing in the way of Black development.

By 1965 that hostility was taking the

form of attacks on White businesses in Black neighborhoods, even

pillaging and burning them in demonstration of the outrage that was

growing in their hearts against White injustice. And the crime rate

within Black communities began to skyrocket. The social order seemed to

be crumbling rather than improving with the government's efforts to

better the lot of Blacks in America.

Idealistic or Liberal Whites could not

understand this strange response of the Blacks to White efforts at

reform. They probably had never heard the term "the revolution of

rising expectations." They did not understand that people long

compliant to oppressive authority do not automatically rise up to throw

off their chains just because the oppression is great.

Idealists (such as, for instance, Karl

Marx) however believed/believe religiously that this was how the noble

human spirit would automatically and inevitably produce the great

revolution that would one day usher in the class-less, state-less,

totally egalitarian, totally voluntary society (voluntary with respect

to a person's willingness to work hard for the common good). As

oppression worsened, people would begin to move automatically toward

revolution, even violent revolution.

But things just do not work out that way in the real world. People

actually are quite able to accommodate themselves to their chains. This

is not a very noble picture of human nature. But it is a realistic

picture. Action moving people to change things does not happen until

the people begin to have reason to believe that change is possible.

They will not throw off the way they have learned to live with

oppression until they are fairly confident that change, that some kind

of release from the oppression, is possible.

Then once they see the system bending or

cracking, they begin to become bolder in their push for change. As the

oppressing system begins to back down, they then easily become irate

and indignant at the injustice of the way things were and impatient

waiting for reform or change. Once they finally see that things are

moving in their favor, they then become defiant, even heroic in that

defiance. That's when they finally become truly "revolutionary." But

not until then.

Thus the more that the White society

began to accommodate Black interests in the 1960s, those interests

began to gather momentum, until they became truly a storm of passion.

It was not because just at that point that oppression was just starting

to get severe, but because at that point the severity of it seemed to

be lifting. Then all the impatience at the slowness of the process of

change began to set in. Then the anger mounted, then the violence

picked up. This was the phenomenon the Whites were observing, rising

Black militancy in response to the Whites' honest interest in seeing an

improvement in the Black situation.

But the Whites had no idea of why the

more they tried to improve things, the more indignant and resentful the

Blacks became. It was just human nature. But American Idealists had

(and still have) very little accurate insight into human nature. They

had made man into a rational, loving man-God. But this man-God was

behaving neither rationally (as Idealists understand "rational") nor

lovingly in the American streets as the 1960s rolled along.

White guilt vs. White bitterness

The White effort to make sense of their

Idealistic universe gradually took the form of either 1) a rising White

self-hatred and the deep need to apologize for their ancestors having

left such a horrible legacy of racism (the typical response of

self-shaming Liberal intellectuals and Boomers), or 2) a rising White

bitterness about the Blacks' inability to maintain a decent sense of

law and order among themselves (the typical response of the Vets).

Political lines were beginning to be drawn up for battle as the

situation in America worsened.

At the same time, America was now

witnessing a deepening of the bitterness of Black America as high

expectations for rapid progress in Black social development failed to

be met immediately by the "system." Young Blacks now turned on the

system in anger, looting and burning the world immediately around them.

In 1965, the Watts section of Los Angeles was looted and burned, also

involving thirty-four deaths in the accompanying violence, done so to

the refrain of "Burn, Baby, Burn" ... with police sirens answering back

in refrain as Black Power advocates were carted off to jail, either as

self-sacrificing heroes or dangerous criminals, depending on which side

of the ideological divide you found yourself on.

The arrest of a Black cab driver in

Newark, NJ in mid-July of 1967 also set off a rampage by Blacks in that

city. Firebombs and looting degenerated into sniper shooting. A curfew

was imposed on the city, which slowly restored order. But eleven people

had been killed, 600 wounded or injured and whole sections of the city

were completely gutted by fire.

When several days later a prescheduled

National Unity Conference was held in that city, the language was one

not of unity but of declared war. Black power advocate H. Rap Brown

urged the gathering to "wage guerrilla war on the White man." Los

Angeles Black Nationalist Ron Karenga stated "Everybody knows Whitey's

a devil. The question is what to do about it."

Meanwhile, moderate Black leaders such as

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Roy Wilkins, and Whitney Young, Jr.

avoided the conference.

In late July, violence broke out in

Detroit. Learning from Newark, Detroit mayor Cavanagh immediately

called in the National Guardsmen. But seven thousand Guardsmen,

complete with tanks and armored cars, could not restore order. Governor

George Romney (who was understood to be a potential Republican

candidate for the Presidential election in 1968) contacted President

Johnson for assistance. Johnson held back until Romney confessed before

the public that he had lost control of the situation. Then Johnson sent

in U.S. paratroopers to retake the city, house by house, block by

block, similar to a Vietnam military action. When a week later the

troops had brought Detroit back to order, forty-three people had been

killed and over a thousand injured.

Meanwhile the violence spread to New York

City where a 28,000-man police force with experience in riot control

restored order to East Harlem after three nights of violence. Two

people were killed.

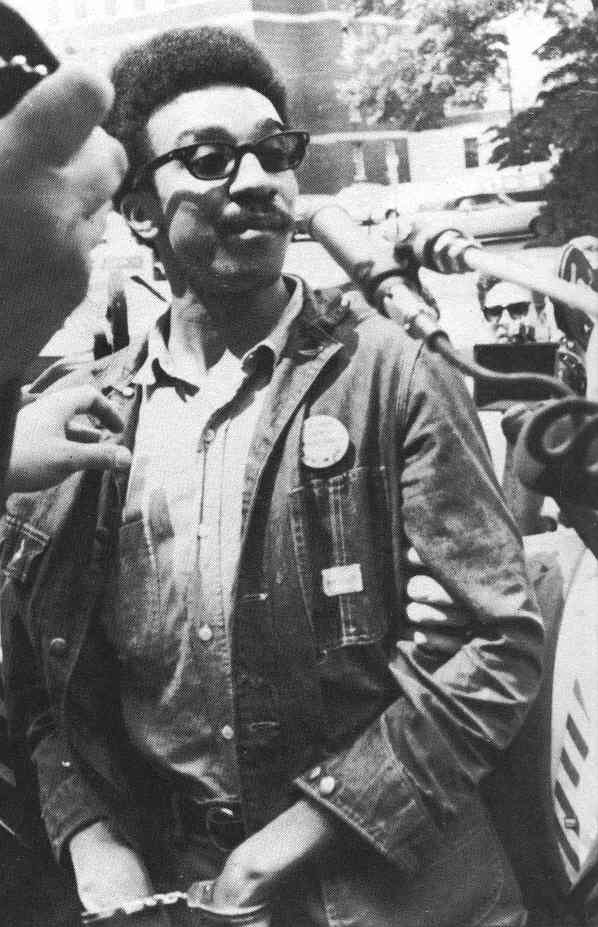

H. Rap Brown had in the meantime moved on

to Cambridge, Maryland, and following a Black-power rally there, the

town was subjected to looting and arson. Brown was arrested for

inciting a riot. As he was led away by FBI agents, Brown challenged:

"We'll burn the country down."

Faced with this confusing and mounting

crisis, Johnson appointed a study commission to investigate the root

causes of the violence. What it announced in its preliminary report in

late February of 1968 indicated a situation of high expectations among

the Blacks for extensive social reform, met with little practical

chance that such improvements would actually come about quickly. Also,

the inner cities abandoned by White flight to the suburbs left Blacks

who had migrated to the northern cities with no jobs and a rapidly

deteriorating urban infrastructure. Educational levels were very low,

with poor and dangerous schools able to provide no remedies.

It quickly became the assumption within

Johnson's Great Society government that huge amounts of governmental

money were going to have to be poured into the inner cities where

Blacks had congregated to correct these problems of jobs, schooling and

housing. Clearly, Johnson's government had no expectations that the

Black communities would be able to address or correct these social

challenges themselves. They would have to come to depend on government

"assistance" – on a massive scale – if any serious improvement in the

Black social situation were ever to occur.

|

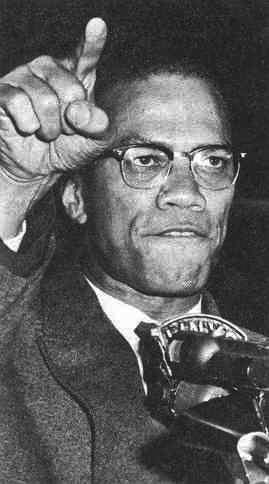

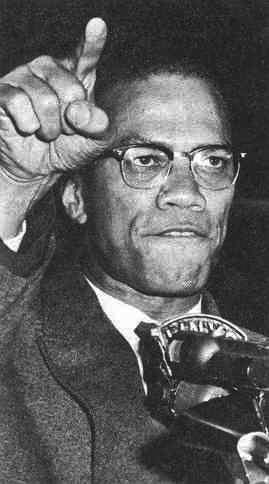

Malcolm X,

1925-1965

Malcolm

X

Malcolm

X

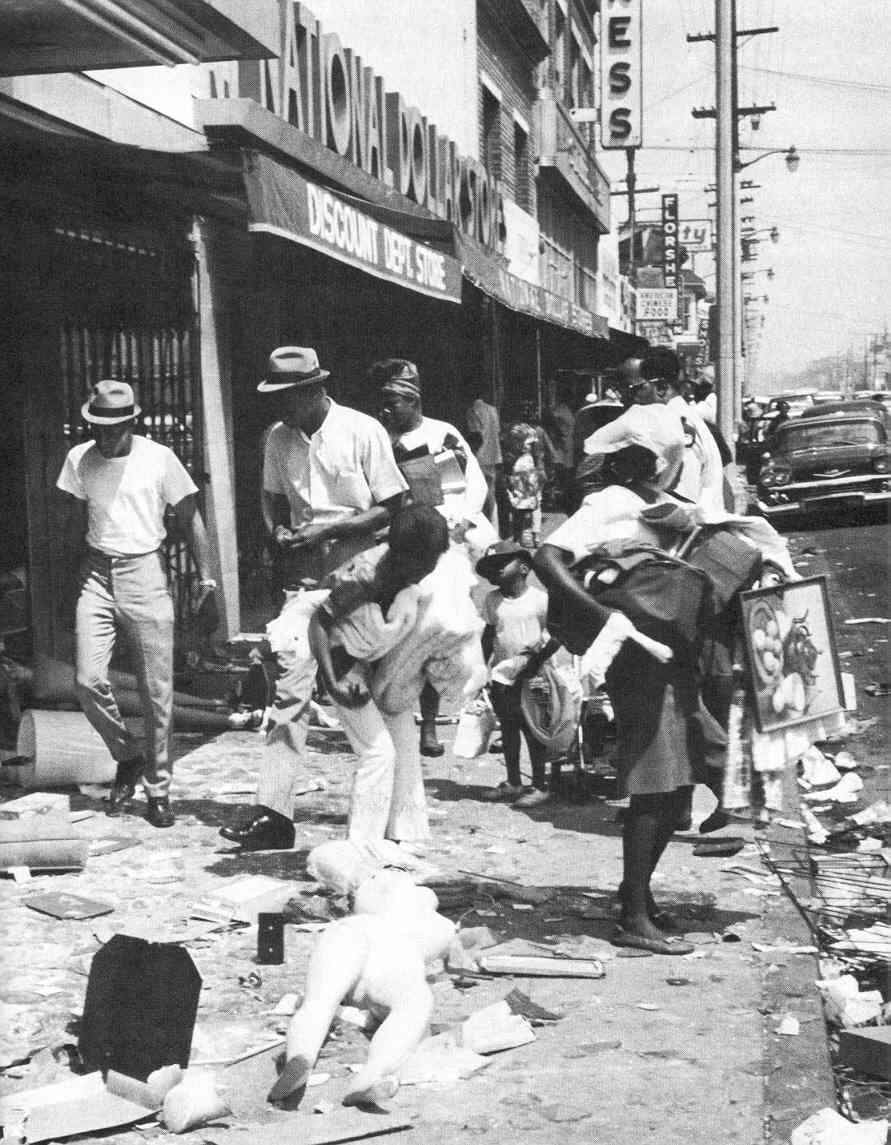

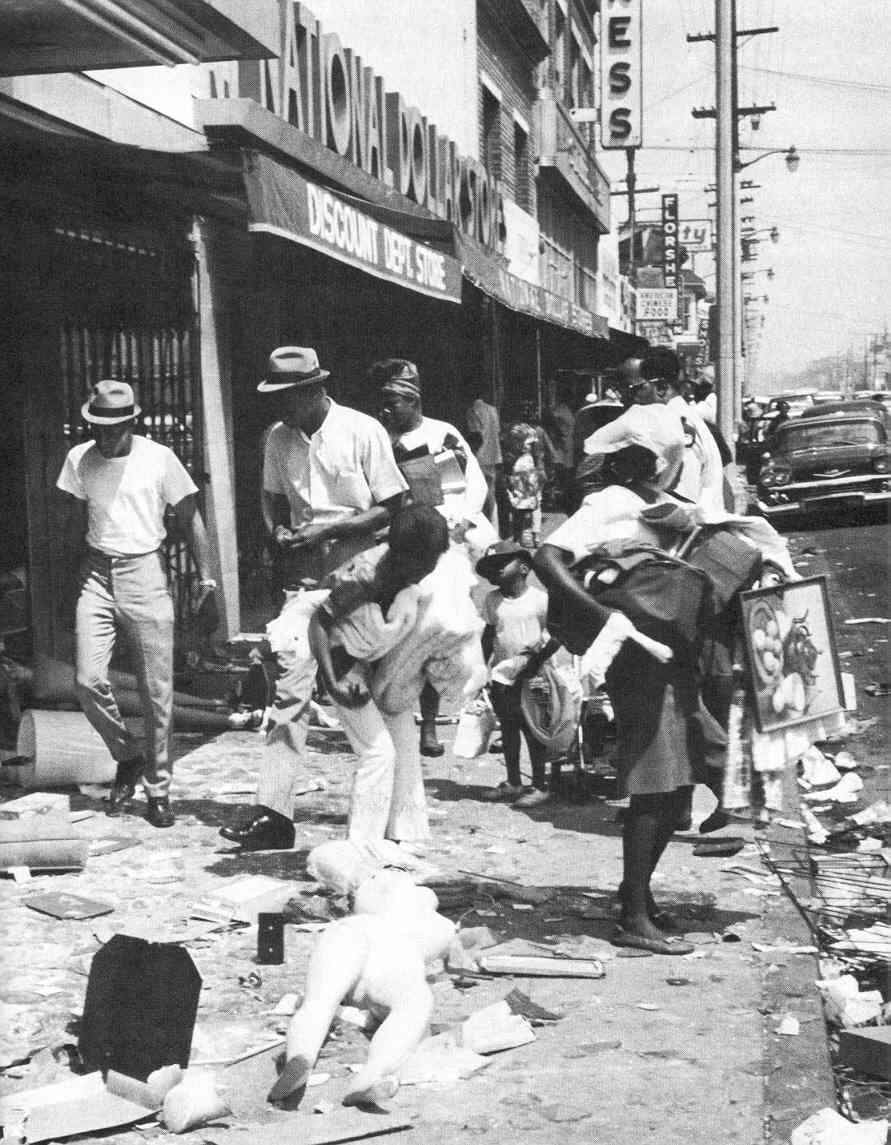

Blacks demonstrate their

new freedoms by torching the world around them (what exactly was the logic

in this behavior?)

Rioting and arson in Watts

- 1965 (less than a week after the passing

of the Voting Rights Act)

Black looters in the Watts

section of Los Angeles – August 1965

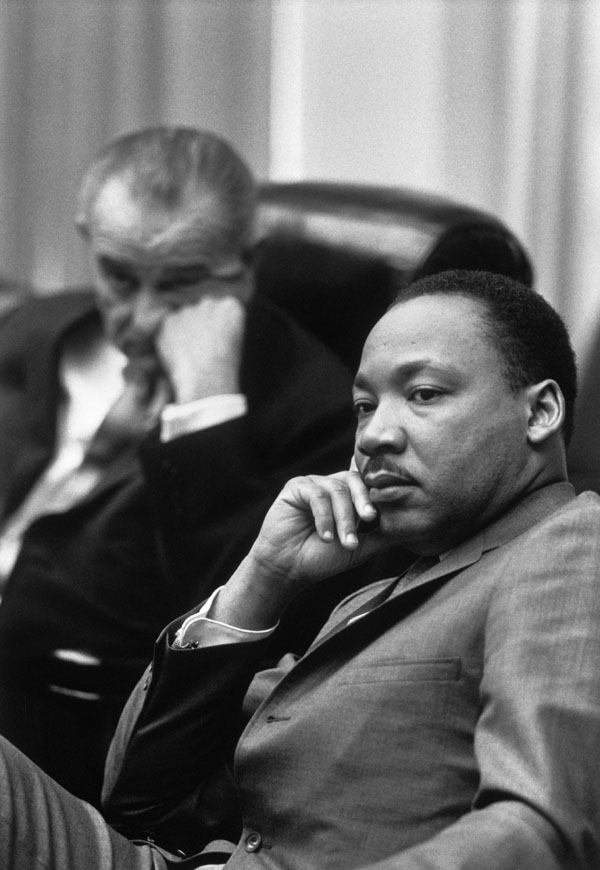

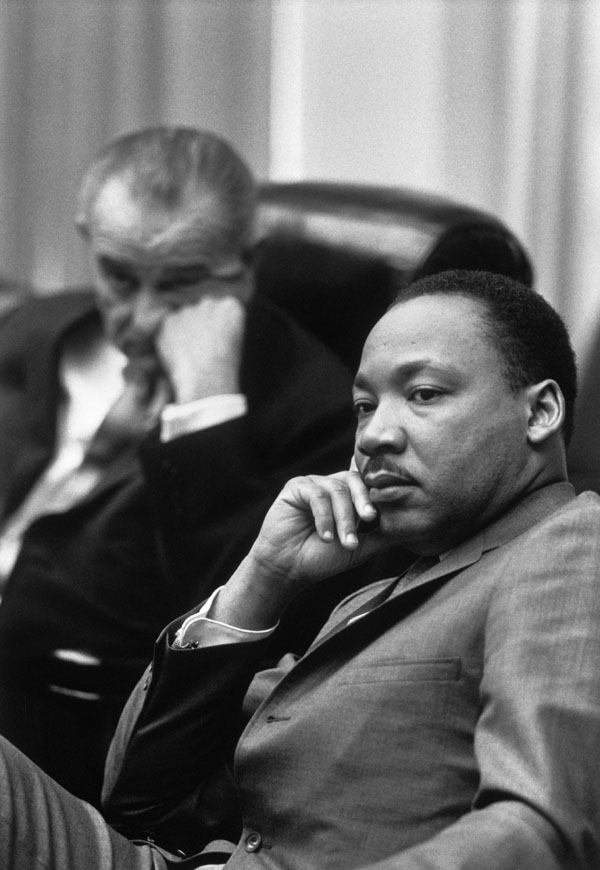

Rev. Martin Luther King,

Jr.; President Lyndon Johnson in background (the breakdown of social

order was not at all what either of them expected or wanted

the civil rights

movement to develop into)

By Yoichi Okamoto, Washington,

DC, March 18, 1966

Lyndon Baines Johnson Library,

National Archives

Blacks lining up for the

vote in rural Peachtree, Alabama – May 3, 1966

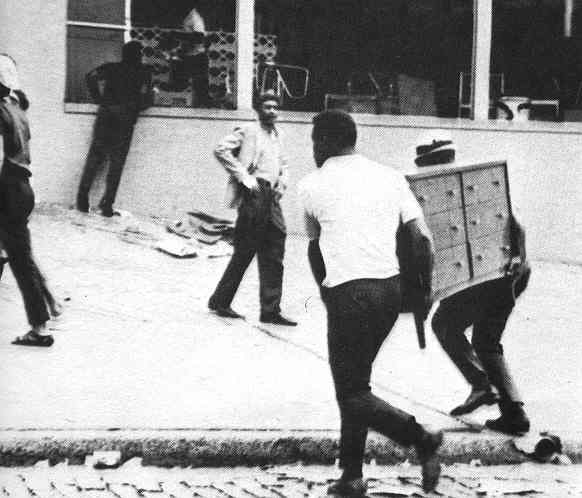

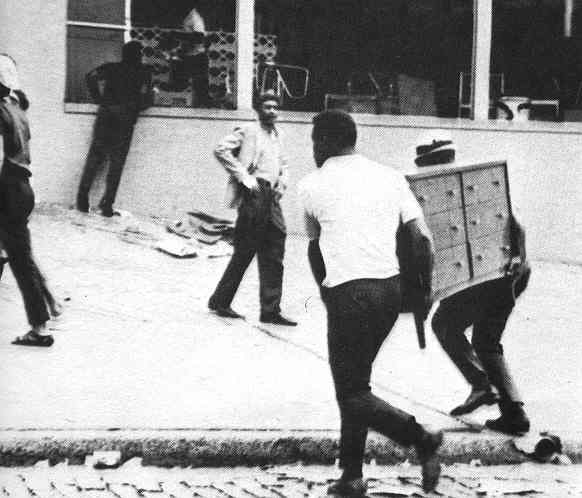

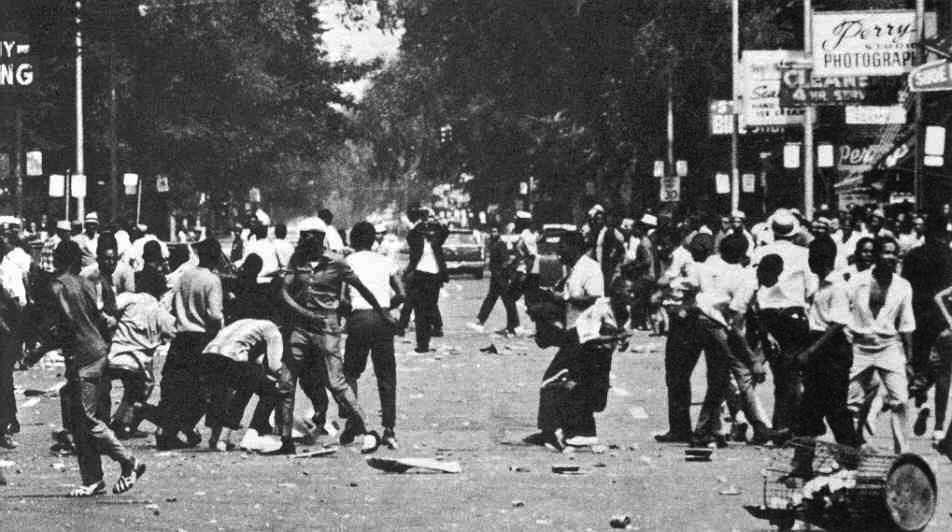

For many young Blacks, 1967

was yet another summer for looting and burning (giving rise to the new

mantra: "Burn baby, burn")  Looters in Newark's riots

– mid-July 1967

Looters in Newark's riots

– mid-July 1967

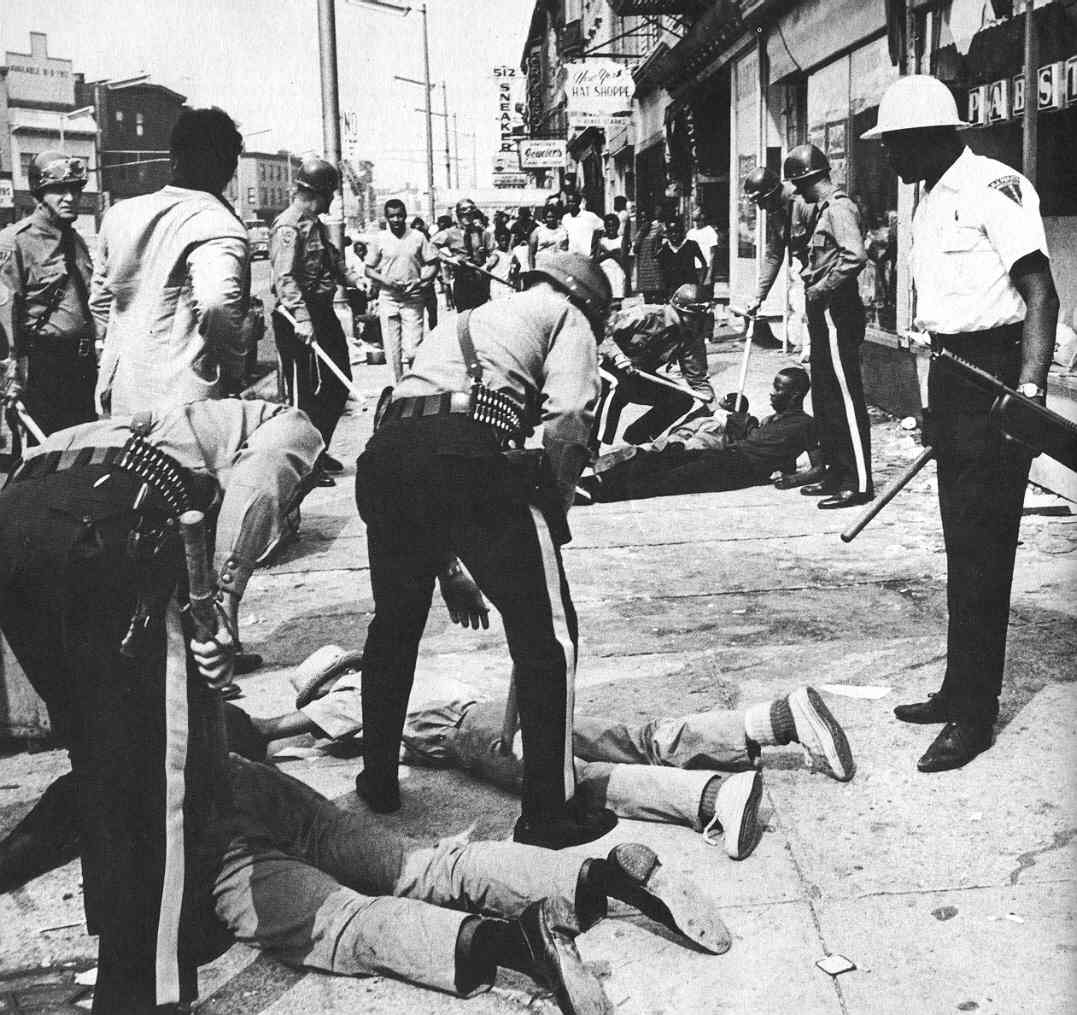

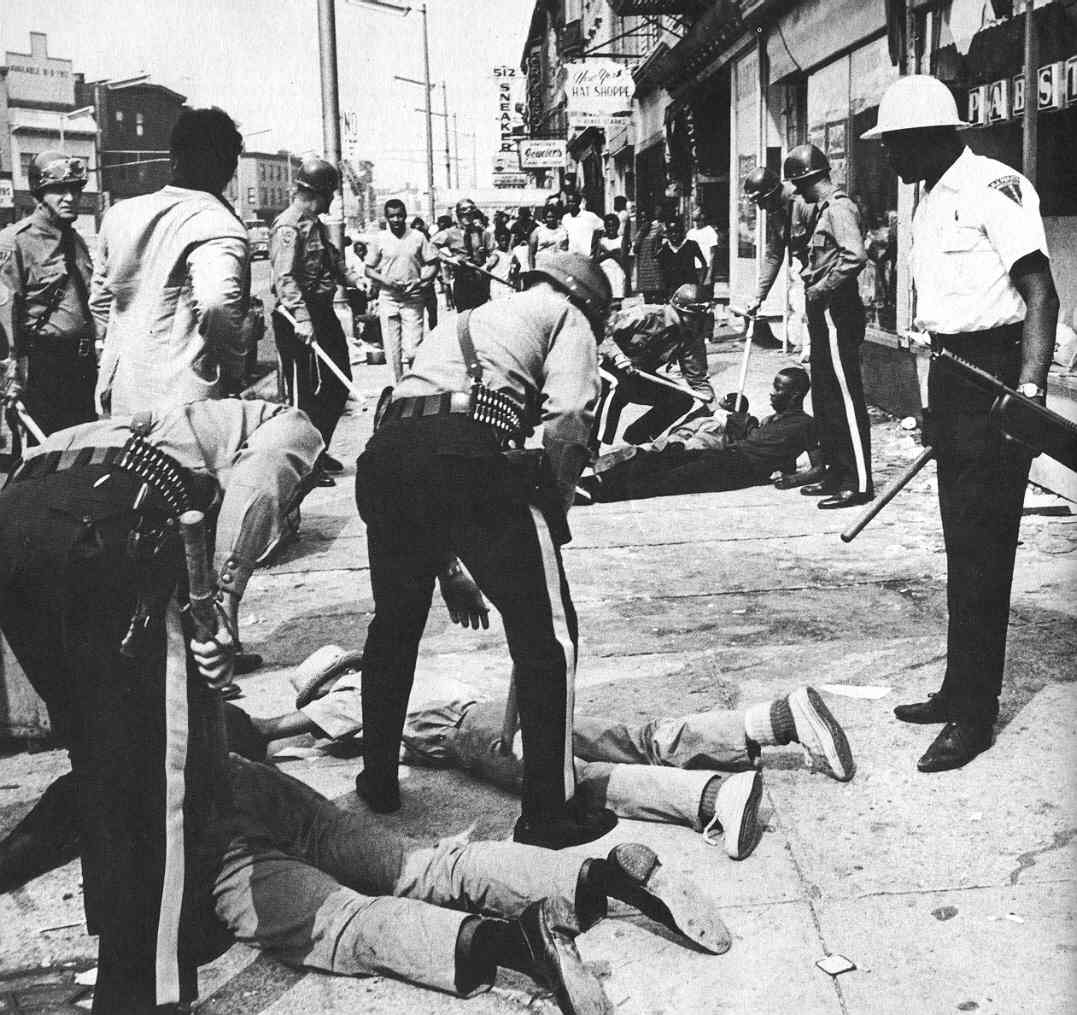

National Guardsmen and police

arresting looters in Newark's riots – mid-July 1967

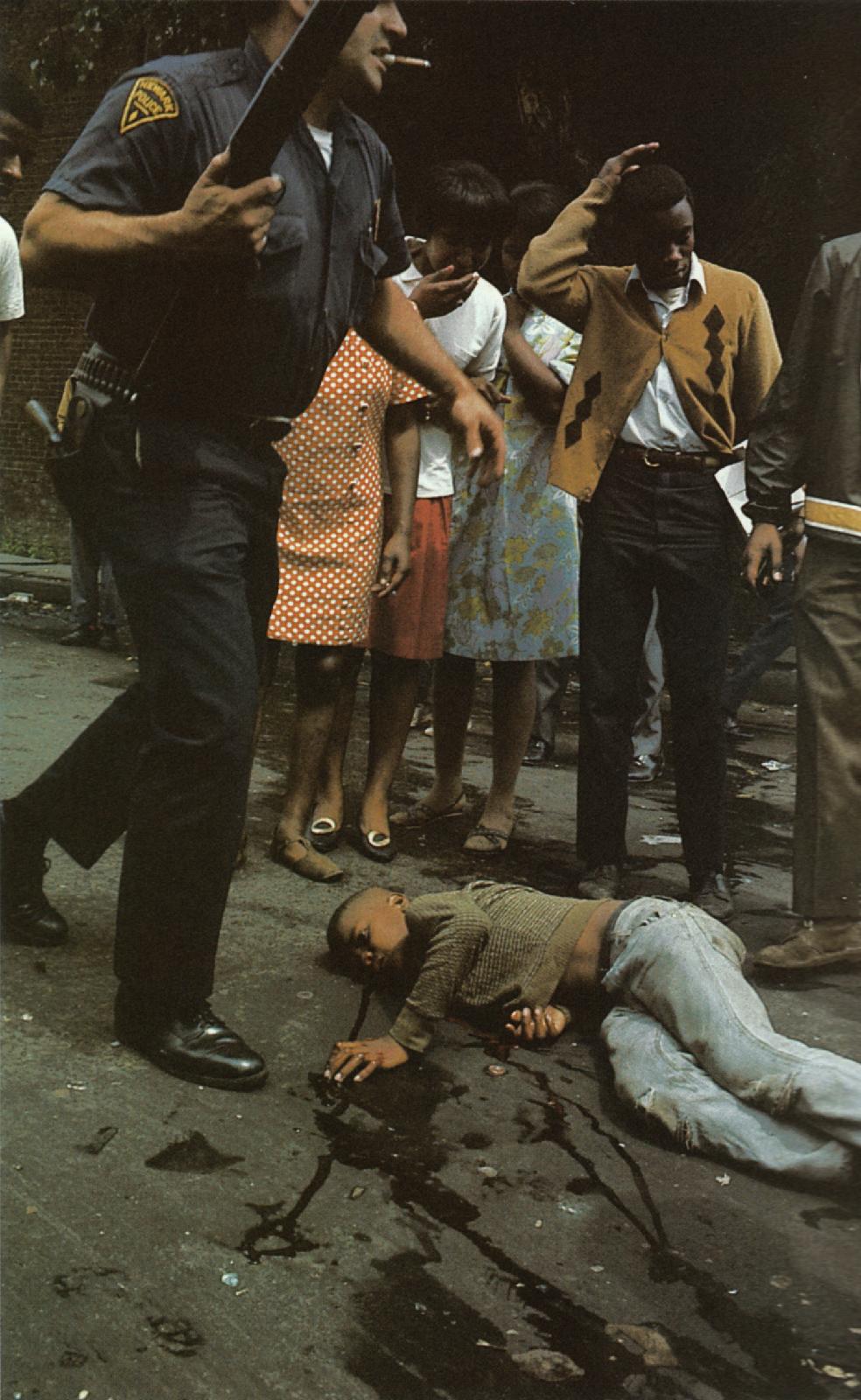

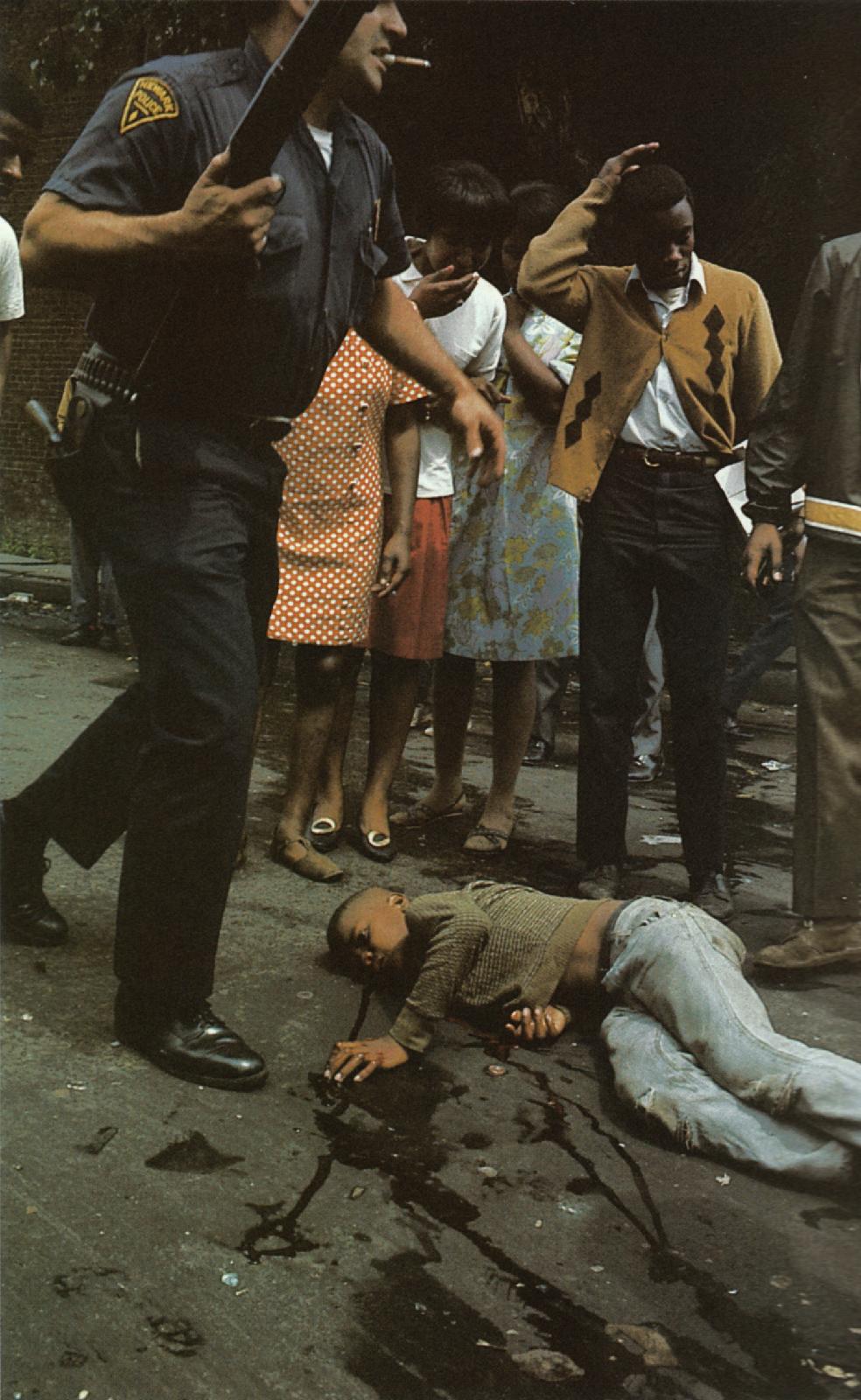

A boy wounded in the Newark

riots – 1967 (26 died)

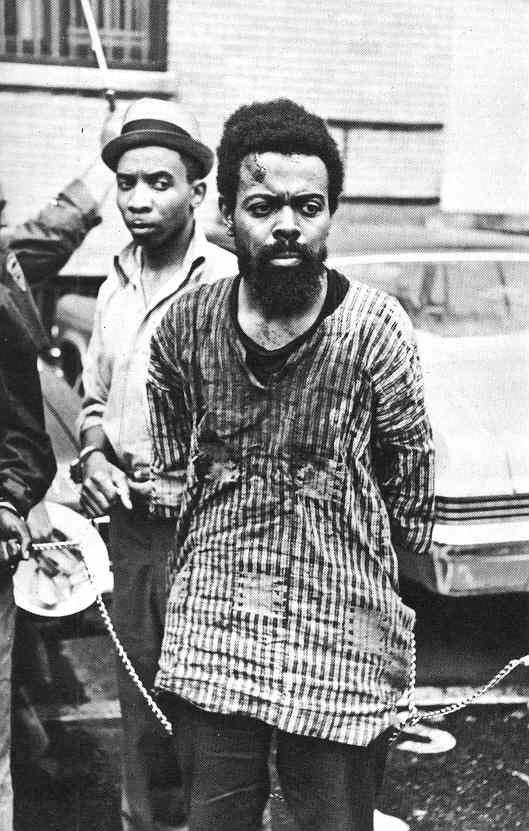

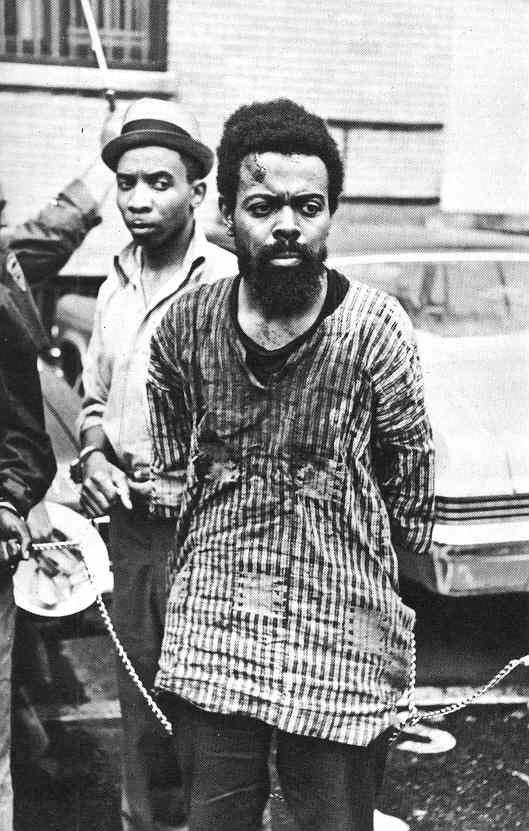

Playwright LeRoi Jones arrested

in Newark for possessing two loaded pistols – mid-July 1967

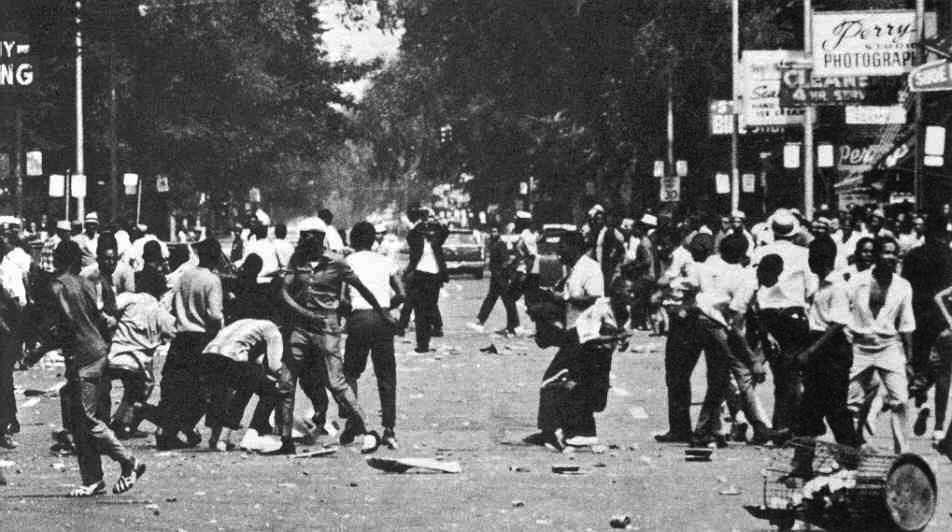

Detroit – 1967:

Black

summertime rioting and pillaging

Blacks rioting in Detroit

– July 1967

Black district in Detroit

set afire – July1967.

One of the many burned-out

sections of Detroit – late-July 1967

A burned out Black middle

class section of Detroit – 1967 (43 people died)

National Guardsmen in Detroit

– July 23, 1967

A National Guardsman standing

watch in Detroit as firemen battle blazes set by rioters – late-July

1967

H. Rap Brown arrested for

inciting the Cambridge, MD riot – late July 1967

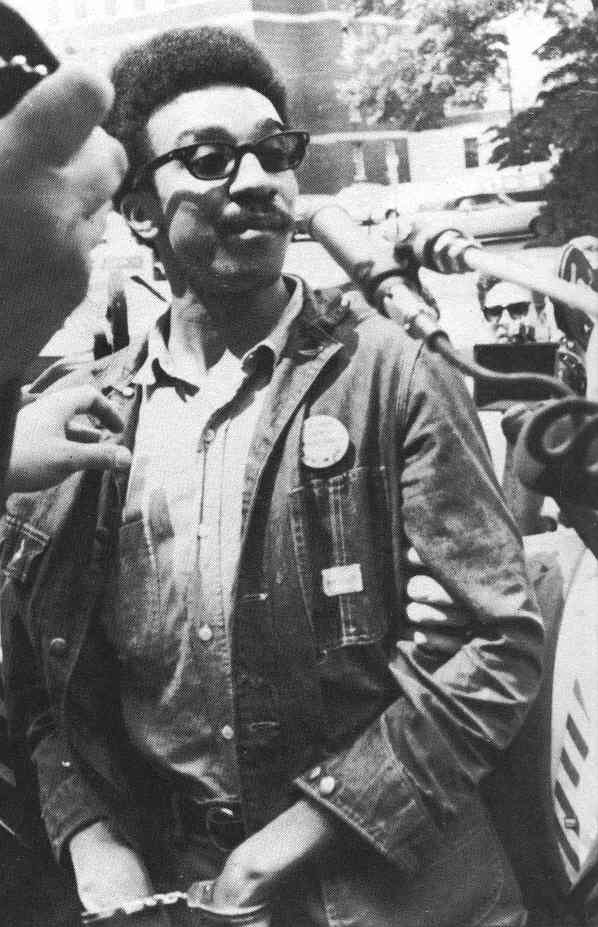

Black Panthers in a defiant

mood Black Panthers in a defiant

mood

Bobby Seale and Huey Newton

Bobby Seale and Huey Newton

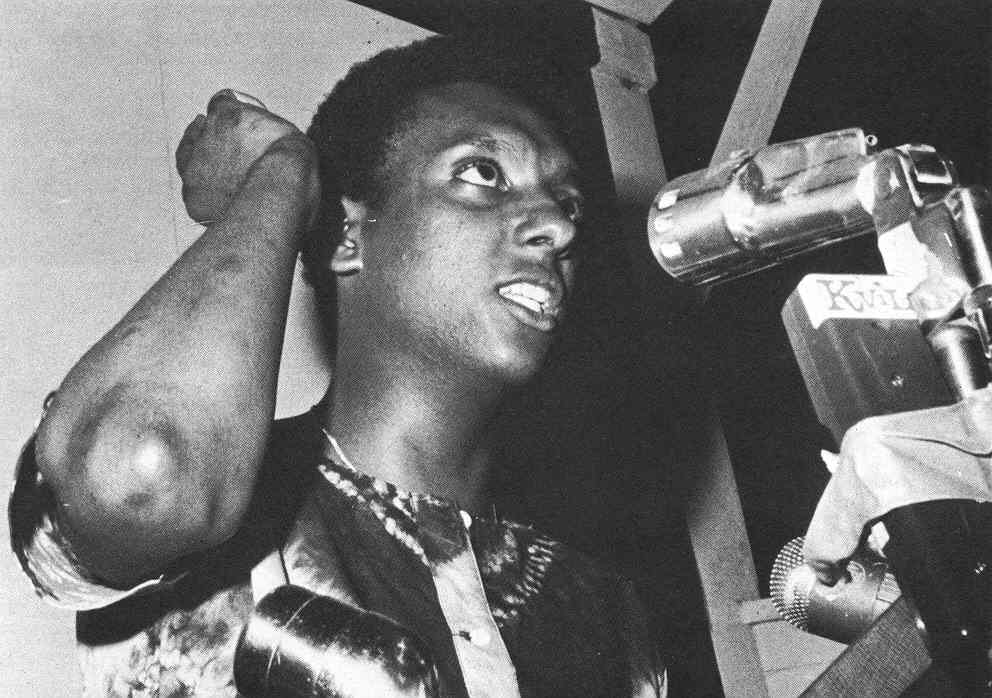

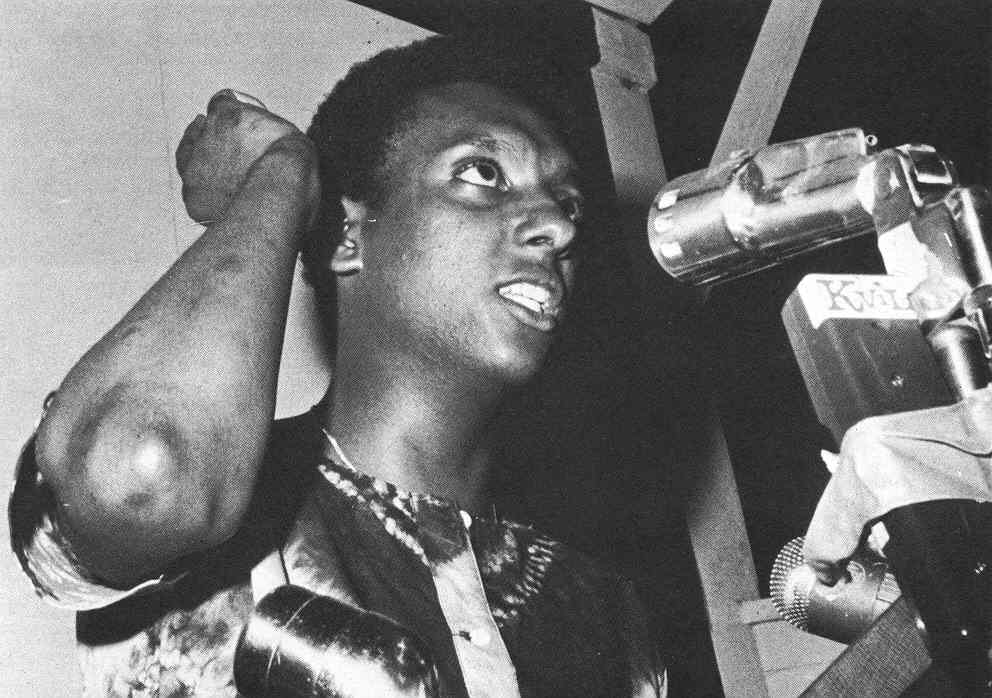

SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael

at a University of Texas gathering, denouncing US imperialism

A RISING CALL FOR AFFIRMATIVE ACTION FOR

WOMEN AND HISPANICS AS SUFFERING "MINORITIES" |

A new feminist movement stirs in America ... "Liberated" women claiming that they too suffer

from discrimination and want full equality with men in the professional world ... now.

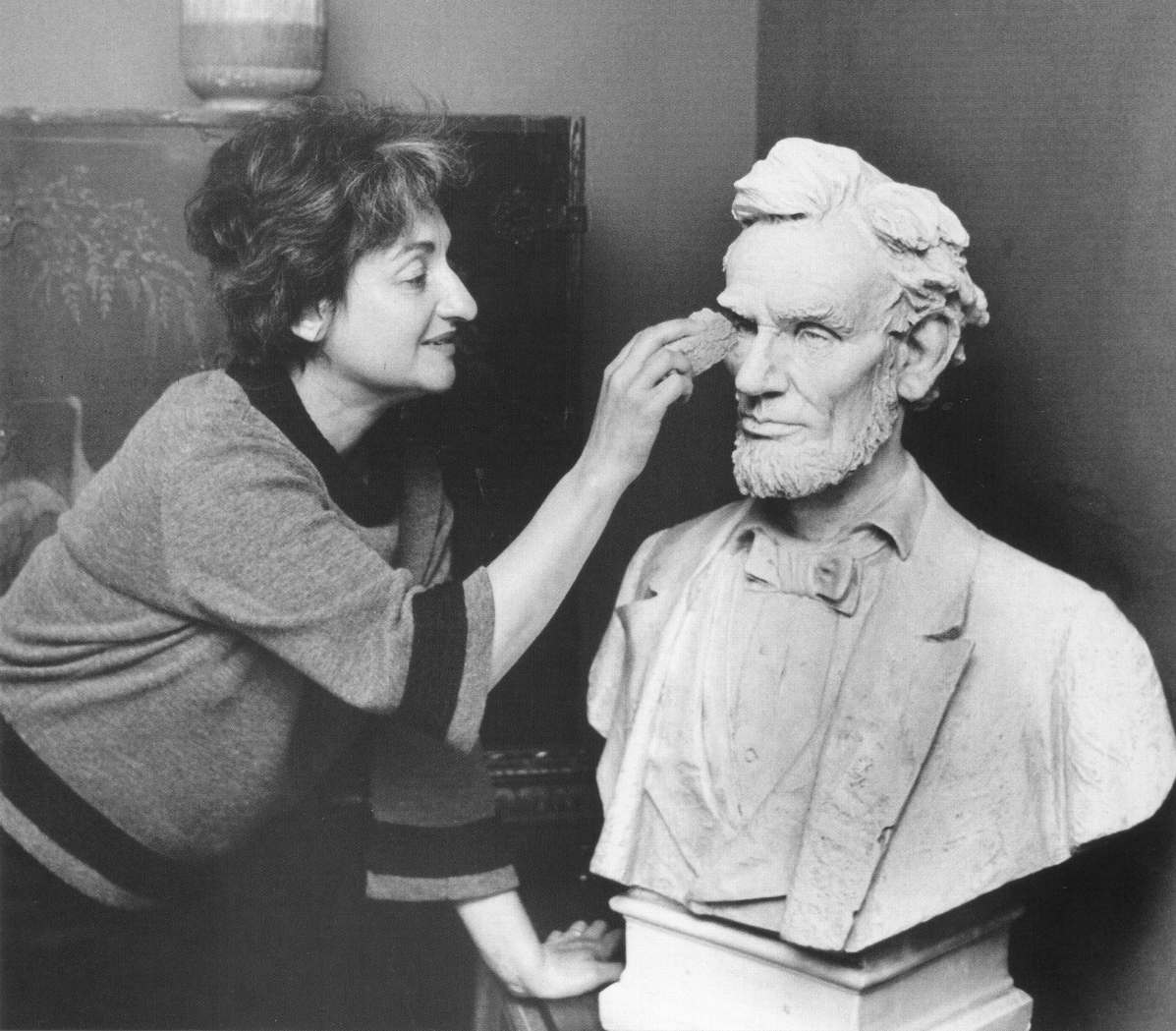

Betty Friedan, author of

The

Feminine Mystique, who attacked the 1950s idealization

of the American stay-at-home housewife and helped start the 1960s feminist

movement, demanding the opening up of the traditional male workplace to

women

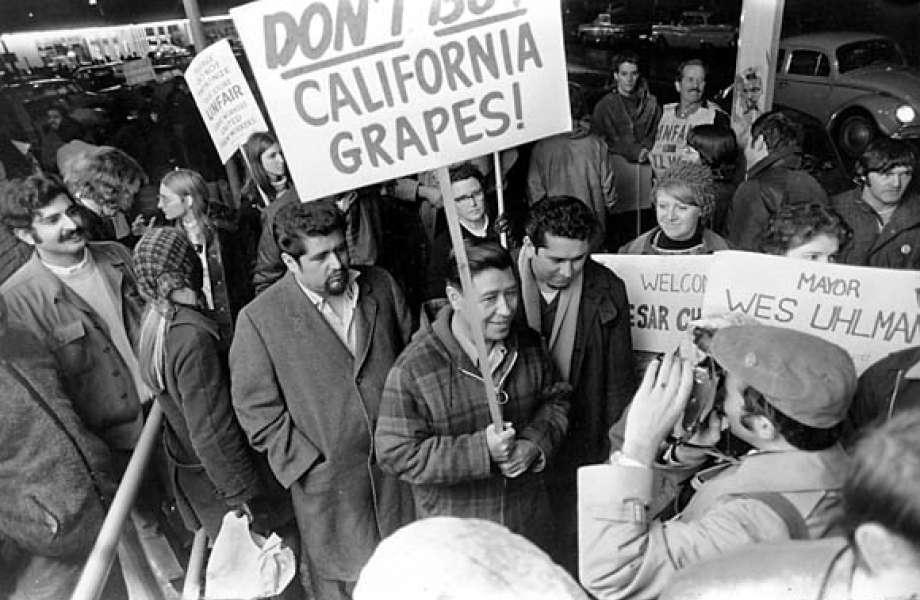

Meanwhile, the civil rights

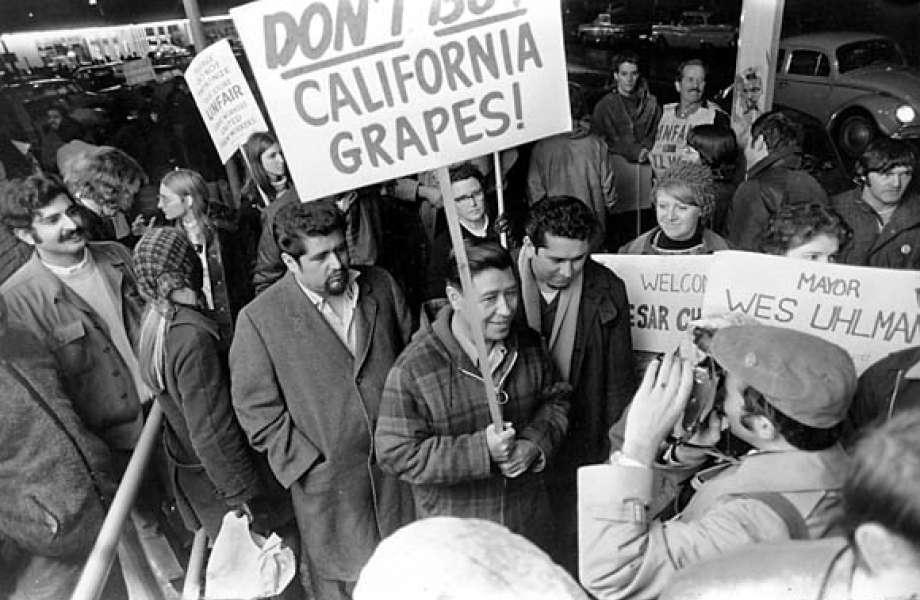

movement is building along another front: the call for a national

boycott of California grapes in

protest against the miserable working conditions of the Mexican migrant worker

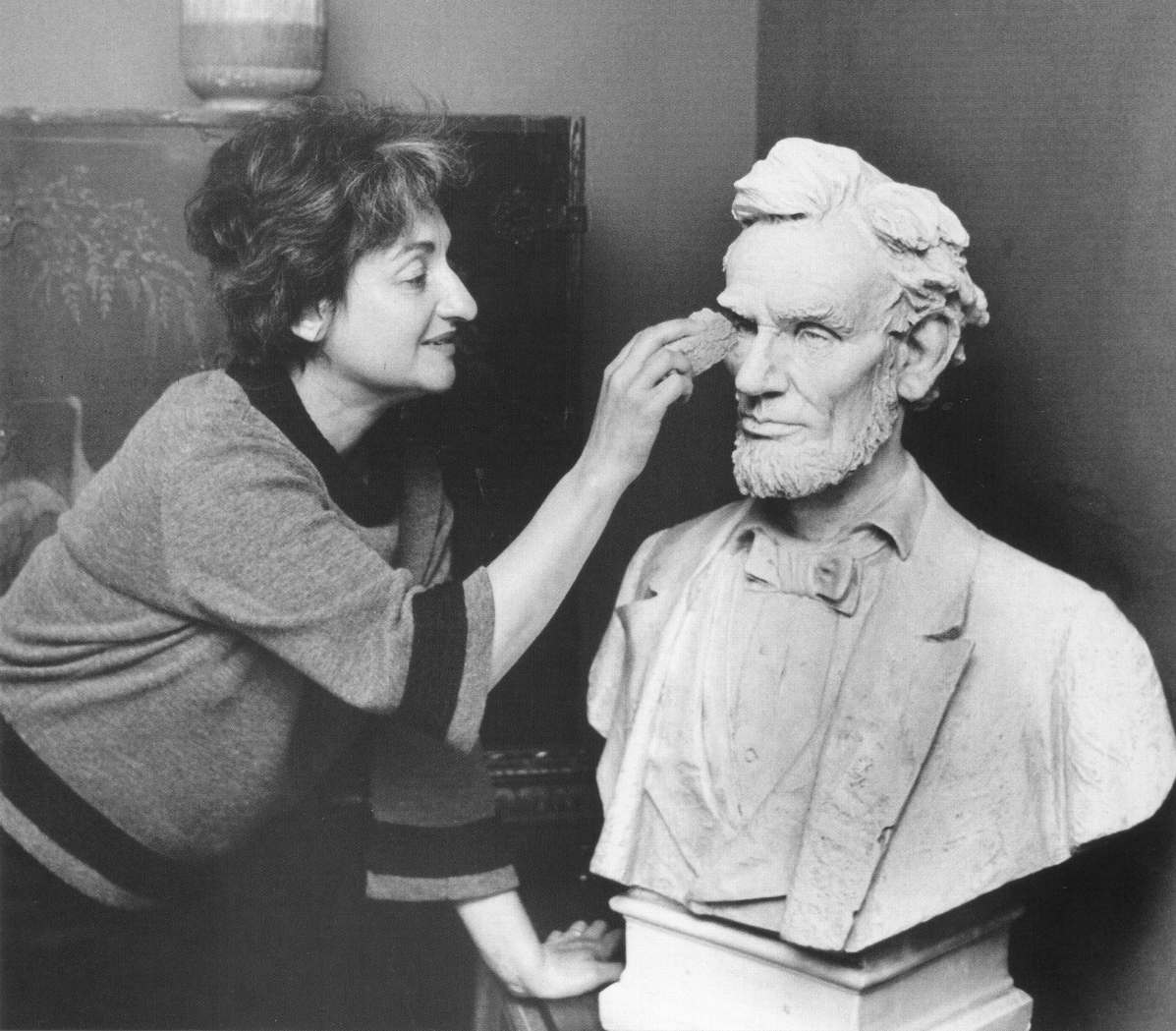

Cesar Chavez organizing grape

pickers in California – 1965

Chavez calling for a national boycott of California grapes – 1969

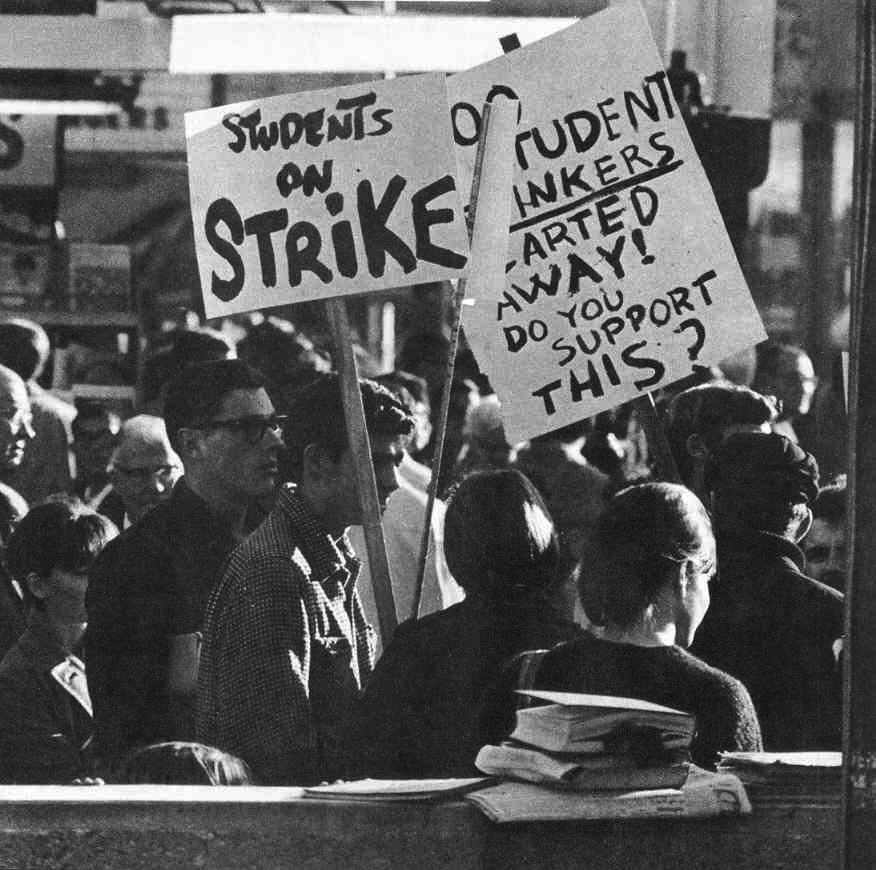

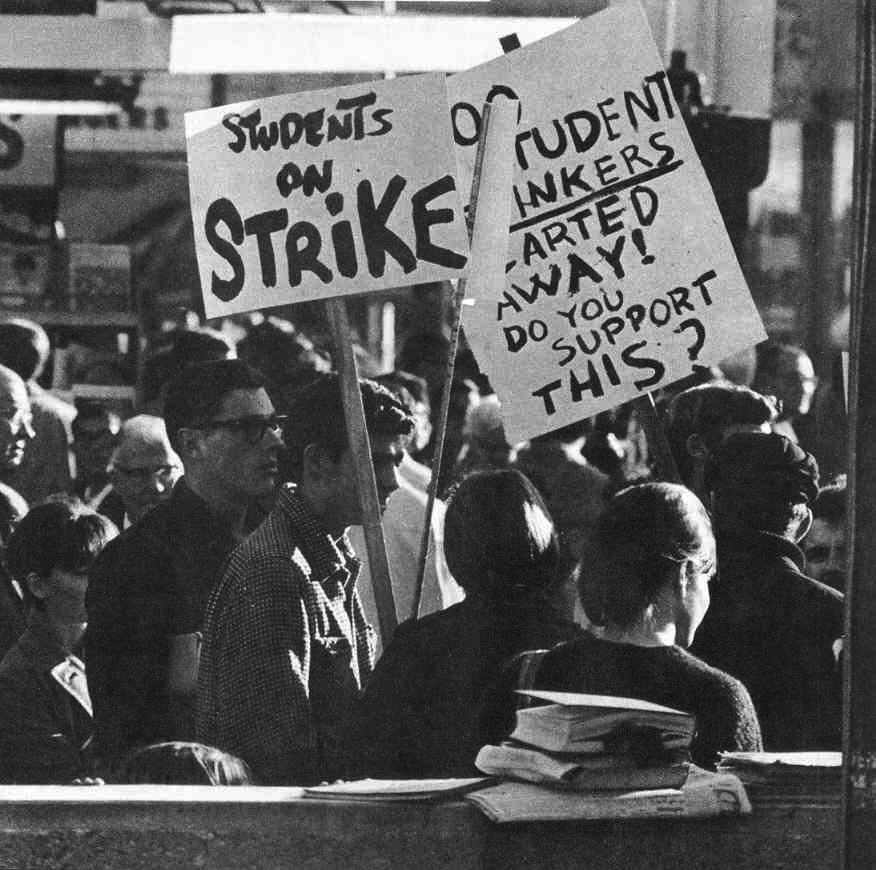

And just in general, Boomers find themselves crusading for most any cause – including a Free Speech Movement ... as if in America free speech is restricted?

The startup of the Free Speech Movement – 1965

A Free Speech Movement nighttime vigil – 1965

THE GROWTH OF THE WASHINGTON WELFARE STATE ... AND THE RAPIDLY GROWING FEDERAL DEFICIT |

|

The growth of the Washington Welfare State

And thus it was that Black society began to

understand its rights as outlined by the Johnson Administration, and

thus to begin to demand not only assistance but also compensatory

action on the part of the national authorities. Blacks demanded their

rights be honored by those in power, not just rights to equal

opportunity in the pursuit of their personal destinies, as Dr. King had

expressed the dream, but rights to special advantages (affirmative

action) and compensations (public welfare) for past wrongs, in other

words preferential treatment or "entitlements." In this they would be

joining the Boomers in their understanding of the role of the American

government, and their sense of citizenship entitling them to be

receivers from, rather than contributors to, the strength of the nation.

Sadly this would lead only to a form of

social-cultural dependency on political favors and handouts, ones that

would block a robust personal growth arising from the self-help that

was historically typical of how Americans were supposed to work their

way to success. This kind of political dependency would slow rather

than speed up the advance of Blacks in American society economically

and socially.

But it did serve conveniently to give the

federal state in Washington all the justification it needed to expand

its social management programming "from above." And it created a whole

new category of professional "community developers" whose role was to

help redistribute or divert the nation's wealth in the direction of

their particular political constituencies.

It was the same game that urban bosses

had played with immigrants coming to their cities in the late 1800s and

early 1900s. "Support us in power and we will support you in the way

you live out your lives on a daily basis." But now it was a game being

played with America's "minorities" by the national bosses operating out

of their offices in Washington, essentially played for the same reason

that motivated the old urban bosses: to receive continuing political

support from their political wards (their minority clients) so as to be

able to stay in power, or better yet, so as to be able to expand their

power bases.

It was an old political game that shifted

locations simply in accordance with the fact of where American power

was to be found. As power shifted to Washington, so did all the old

political dynamics shift along with it. This was just crude power

dynamics at work, not the scientific social management that the

Behaviorists dreamed of.

The rapidly growing Federal Debt

Although this problem did not present

itself in as dramatic a form as other events of the times, nonetheless

a huge financial problem was brewing, one that threatened the health of

the government and the nation. By 1967 the amount of government

spending involved in both Johnson's Great Society and his heavy

military investment in Vietnam was outpacing enormously the

government's income from all of its tax sources. A huge deficit or

government debt began to build up as a result. In that year a

Commission on Budget Concepts studied the problem and concluded that a

proposed 1968 national budget was going to entail a (what was then

huge) deficit of anywhere from $2 to $8 billion in size.

Using the justification of

"rationalizing" the entire national or federal government budgeting

process, including the Social Security budget, which at that time was

largely self-running and not considered part of the national budget (or

"off budget"), the Commission recommended integrating the Social

Security budget with the regular operating budget of the federal

government. At that time the Social Security program, originally

focused on retirement or pension benefits of Americans but in 1965

adding also Medicare (health insurance for the elderly) and Medicaid

(health care for the poor, shared as a joint expense with the States),

was actually running a huge surplus, taking in each year in the form of

Social Security tax revenue more than it was spending for its various

programs. By combining the deficit-running federal budget with the

surplus-running Social Security budget, the government's budget deficit

built up by Johnson's programs could now be recast as being greatly

reduced, or possibly even be shown as running a surplus.

Thus in January 1968, Johnson introduced

the new unified budget. Yet even with the inclusion of the Social

Security surplus with the regular federal budget, Johnson was forced to

admit that the new unified budget would still be running up a $8

billion deficit (the government's expenditures were turning out to be

vastly greater than anticipated in 1967). But the figure was a lot

lower than it would have been without adding in the Social Security

surplus.

|

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | |

The American presidency under

The American presidency under The making of Lyndon Baines Johnson

The making of Lyndon Baines Johnson The civil rights movement gains steam

The civil rights movement gains steam

Johnson's "Great Society" program –

Johnson's "Great Society" program – American politics takes a left turn under

American politics takes a left turn under The continuing attempt to protect

The continuing attempt to protect Affirmative action also for women and

Affirmative action also for women and The growth of the Federal state ... and

The growth of the Federal state ... and

Black Panthers in a defiant

mood

Black Panthers in a defiant

mood