|

|

The fabled Trojan War The fabled Trojan War

Homer and this Higher Order Homer and this Higher Order Hesiod and an ordered pantheon Hesiod and an ordered pantheon Dionysianism Dionysianism Orphism Orphism |

|

|

For centuries, the tale of this single event – the war between the Greeks and the Trojans – served as a social-religious explanation of life, its purpose, its powers, and its limitations.

The "judgment of Paris." The war supposedly began as a result of a beauty contest among the goddesses Hera, Athena and Aphrodite ... with the unfortunate Prince Paris of Troy as the judge. The other two goddesses were burned when he awarded Aphrodite title as the most beautiful goddess ... and Aphrodite "rewarded" Paris by having the exceedingly beautiful Helen, wife of Spartan King Menelaus, fall in love with Paris. The Achaean alliance. When both Paris and Helen fled for Troy, King Agamemnon of Mycenae (and brother of Menelaus) organized a huge Achaean Greek army and navy (some 100,000 men and over a thousand ships) and headed to Troy to try to get Helen back. Leading soldiers of the Achaean army were Achilles – the greatest of all Greek warriors – and Odysseus the adventurer ... and on the Trojan side, Hector, son of the Trojan king and kindly hero but also a very courageous and capable military leader. The intervention of the gods. But in any case it would be more than human dynamics that would determine the outcome ... for the Olympian gods themselves became very involved in the events, some supporting the Achaeans, others the Trojans. Deception was often the tool used by the gods to confuse matters. The walls of Troy were insurmountable (thanks to the help of the gods) and despite the very bloody action between the two sides (often one-on-one battles among the heroes) years went by with the Achaeans unable to breach those walls ... although Achaean warriors, such as Ajax, laid waste to the territories surrounding Troy. Achilles kills Hector. Years of failure began to break down Achaean morale ... and Achilles abandoned the effort when he and Agamemnon fell into a dispute over a concubine. The Trojans and Achaeans then finally met in open field for battle which raged back and forth (thanks in part to the intervention of the gods). Achilles returned to battle when his friend Patroclus was killed by Hector ... and took on Hector directly and killed him (dragging Hector’s dead body behind his chariot as he circled the walls of Troy). Then the story as narrated in the Iliad ended with Hector’s funeral. The Achilles heel.

Other legends then take up the narrative from there. One stated

that Achilles was killed by an arrow shot by Paris, who struck

Achilles’s heel ... the only part of Achilles not protected by his

mother’s holding him there in order to dip him into the River Styx for

his eternal protection.

The Trojan horse. The famous ending to the Trojan War (in its tenth year) was the story told by the later Roman writer Virgil in his epic poem, the Aeneid, (also mentioned in Homer’s Odyssey) about the wooden horse that was left behind in front of the walls of Troy as the Achaeans finally ‘departed’ (though only just out of sight) ... which the Trojans took as a sign of Achaean acknowledgment of Troy’s ultimate victory. The Trojans foolishly rolled the horse inside the gates of Troy ... despite the warning of the Trojan priest Laoco÷n to “beware of Greeks bearing gifts”! Indeed, that night, as the Trojans fell into a wildly drunken stupor, Achaean soldiers hidden inside slipped out of the horse and opened the Trojan gates, allowing returning Achaean troops to enter Troy to slaughter, rape, pillage and burn the city ... to the ground. |

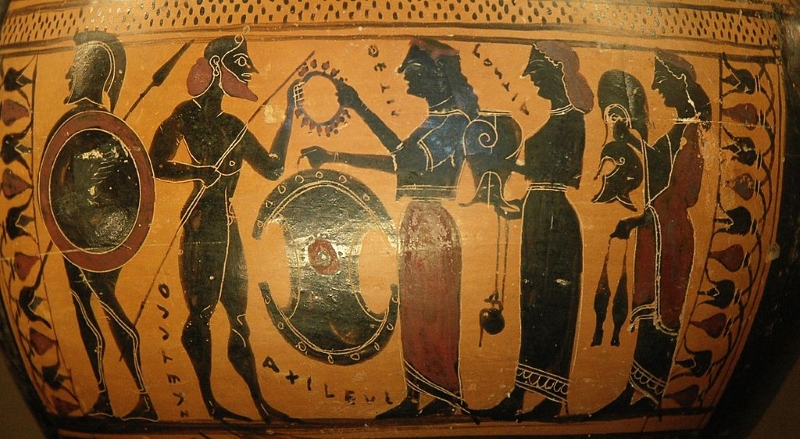

Thetis gives her son Achilles weapons forged by Hephaestus

Paris, Louvre Museum

Achilles treating Patroclus wounded by an arrow

Berlin, Altes Museum

Hector fighting Achilles

British Museum

The earliest-known depiction of the Trojan Horse – from the Mykonos vase (c. 670 BC)

Archeological Museum of Mykonos

|

|

In Homer's saga, the Iliad, the gods have taken sides in this war between the Greeks and the Trojans. They serve as protectors over some of the key human players in the drama – most notably Hector and Achilles. But their

powers are limited – not

just by Zeus' dominion, but by forces which even Zeus cannot control.

The Greek heros can be protected by the gods – but their ultimate fate,

and the timing of such fate, not even the gods can set aside. Zeus

can hold the scale by which the length of the life of the hero Achilles

is measured – but Zeus himself cannot influence the outcome.

‘Fate’

has a higher power than even the Olympian gods.

Also, we see in Homer's work a very strong moral as well a religious or cosmological message. It seems that the sagas

of Homer were designed to touch the hearts of the aristocratic, more military

minded of the Greeks. Very likely this was some carryover from the

religions brought into Greece by the Greek (Aryan) invaders – offering

religious encouragement and moral justification for their dominant political

roles. The moral theme underlying these sagas was (not surprisingly)

that of valor – valor of the lone conquering hero in the face of overwhelming

odds and even death.Thus it was that by the time of Homer the ultimate or cosmological Order was beginning to be understood as somehow transcending the world of the humanlike Olympian gods. Such Order is a mystery – yet it is quite real. |

|

|

Anaximenes (anak-SI-muneez) was reportedly a pupil of Anaximander's and the third in the trio of great Milesian philosophers. He rejected most of Anaximander's theories about the world and the surrounding universe. He felt that it was self-evident that the world was a flat object, not a cylinder, and he rejected the idea of the earth just hanging in a void of space. Like Thales, Anaximenes looked to a less mysterious source of all things, to a primary material substance foundational to all things, one more readily present in our observable world. Anaximenes concluded that the primal substance of life was air or mist (pneuma) – an invisible substance that filled all the universe. It could be both the source of all things, and yet one of the created things itself – because of its power to change form. Here too, it was probably natural for Anaximenes to accord air the honor of being the primal substance or underlying material of all things. Greeks commonly understood air to be the ‘breath’ or ‘spirit’ (also pneuma) of life, the source of the soul, and so it was logical to think that air might be the primal substance of all things, the soul or spirit of all life. In any case, he argued that through a process of becoming more or less dense, air could change form. Thus fire was air in its most rarified form. The natural progress from there as air thickened was: wind, clouds, water, earth, and stone. Also, the soul quality of air (as the Greeks understood it) could explain movement, events, life itself. All in all, Anaximines' theory of the substance of life seems more complete than his Milesian predecessors. It was truly a great intellectual accomplishment – though being founded on a faulty premise, we find it interesting only for its methodology and not for its conclusions. |

|

|

Side by side with the Olympian pantheon existed a number of religious ideas and practices of the Greeks. Some of it came in with the Doric invaders of the 1100s BC and some of it either predated all Aryan Greek invasions – or else came in later from the East. These tended not to be so orderly but instead seemed to anticipate the disorder of life caused by gods who needed to be appeased directly (through sacrifices) and often. Among the Greeks one of the most persistent and widely popular of such non-Olympian religions was Dionysianism. This was a rather wild fertility cult that perhaps predated the Greeks – a cult which managed to get a quite a hold on the Greeks at some point in their history. The Thracian story of Dionysus/Bacchus seems to have developed many versions over the centuries--especially as the story was assimilated into Greek theology. It may have originally included blood sacrifice – perhaps even human as well as animal. Indeed part of the original Dionysian myth brings the hero Dionysus to a bizarre death at the hands of female devotees, who literally tore him limb from limb in a religious frenzy. One of the major versions tells us that Dionysus/Bacchus (called also Zagreus) was the "illegitimate" son of the god Zeus and the goddess Persephone. He was torn to pieces and eaten as a boy by the Titans--set up in their fury by a jealous Hera, the wife of Zeus. The Titans then themselves took on divinity from such a grisly meal. But in turn, the Titans were struck by lightning--and turned to ashes. But from the ashes of the Titans grew the human race: which is thus part divine (Zagreus) and part evil (the Titans)! But also: Bacchus' heart was not eaten but given to Zeus, who used it to bring Bacchus back to life. Some versions of the story tell that this happened as Zeus swallowed the heart himself. Other versions tell that this happened when the heart was given to Semele--who swallowed it and gave birth to Dionysus. Another version of the story tells us that Dionysus was reputedly the son of Zeus and Semele (Phrygian goddess of the "earth" or "Earth Mother"). By mysterious circumstances, Semele was destroyed by Zeus' power of lightning--along with the boy. But Zeus rescued the boy from the ashes, taking him up and encasing him in his thigh--from which he was reborn later in his maturity. According to most accounts, Dionysus traveled the world to teach the cultivation of grapes (and to spread his worship among men). According to several different accounts, Dionysus was killed by either a group of crazed women--or by his own his own mother--in a frenzy of the very worship which he introduced to the people. Thus the tearing and eating of raw flesh of a sacrificial animal (symbol of Bacchus) was understood to impart divinity to the devotee--as it did the Titans.

Being a fertility cult, it was a rite closely associated with the growing season – especially of the grape, the source of the Greek's precious wine. Drunkenness was thus a natural accompaniment to the festivities. It seems however that gradually this worship form was toned down by the Greeks – until it became a respectable worship form involving even the Greek aristocracy (who were always the bastions of original Olympian worship). Indeed, it was the refinement of Dionysianism that produced Greek drama – for it was at the Dionysian festivals that the famous Greek playwrights (Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes, etc.) offered their new theatrical pieces to their Greek audiences. |

|

|

Orphism seems to have been part of that effort to tame Dionysianism. But even this later development within Dionysianism is so clouded with mythology that it is hard to tell how or where it all started. The figure of Orpheus stands at the heart of this Dionysian "movement." There may have actually been a religious reformer who gave rise to the Orphic myth. But by and large, the Orpheus that has come down to us in story or myth seems to belong to the world of the gods rather than men. The common story was that he was the son of the Thracian king Oeagrus (or some Thracian god) and a Muse. From his mother's side he inherited great musical talents. From his father's side he inherited his love of adventure.As an adventurer, he took part in the Argonaut expedition of Jason--where he played a key role with his music making. Later stories have him as a wandering philosopher in search of knowledge. He married Eurydice, who was bitten by a serpent and died. Being inconsolable over this loss, Orpheus went down to Hades to get her back. He wooed her from the gods with his beautiful music--who let her go. But they did so on the promise that she would not look back on her way out of Hades. But she failed in this important stipulation--and was returned to Hades as a ghost. As a result, Orpheus vowed to have nothing more to do with women. But the Thracian women (or frenzied Maenads?), during a Dionysian orgy, tore him apart--the same fate that met Dionysus. (Beware of Thracian women!) Ultimately Orphism developed into a theological refinement of the Bacchic religion. At first it was strongly persecuted by Bacchic priests. But eventually it became established within the Bacchic system. Orphic teachings that began to come forth over time had much in common with Hinduism and Buddhism (perhaps from mutual Aryan roots). Orphism held a sense of dualism about human existence: 1) the earthly or physical existence (derived from the Titans) and 2) the heavenly or spiritual existence (derived from Zagreus or Bacchus or Dionysius). Within Orphism, earthly life was seen only as a merciless round of pain and trouble (product of evil). Though we humans belong to the heavens, to the stars (as semi-gods), we are also bound to life by a cycle of death and rebirth. The goal of life: escape from earthly existence and release to eternal life. But the fate for most folks was really not escape--but rather a period of death (and torment) and then rebirth--according to the merit of one's earthly deeds. Thus Orphism held much concern about

the after-life. It included instructions on how to enter the after-world.

Likewise, it sought to reform Bacchic or Dionysian worship in order to

increase one's spiritual nature--and diminish the portion of one's physical

being so as to become one with Bacchus (or Dionysus). Orphism shared many features in common with another worship form found further to the East: Hinduism. Orphism developed a theology of reincarnation and transmigration of the souls through endless cycles of birth, growth, decay and death – in which escape from the grip of this eternal dance was the desired goal of the Orphic devotee (as with Hinduism's offshoot, Buddhism) Orphism, as a worship or religious form also had various kinds of purity rituals designed to help the devotee avoid certain types of contaminating influences. Thus the most rigorous practitioner avoided animal food (as with the Hindus) except for sacrificial rituals. Further, despite its connection with wild Dionysianism, the Orphic devotee took wine only as a sacramental act--as a symbol indicative of the mystical enthusiasm of one who sought union with the god Bacchus--or Eros!

Orphism shared many features in common with another worship form found further to the East: Hinduism. Orphism developed a theology of reincarnation and transmigration of the souls through endless cycles of birth, growth, decay and death – in which escape from the grip of this eternal dance was the desired goal of the Orphic devotee (as with Hinduism's offshoot, Buddhism) |

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges