18. WORLD WAR TWO

AMERICA ENTERS THE WAR

CONTENTS

The Atlantic Charter (August 1941) The Atlantic Charter (August 1941)

Growing Japanese-American tensions Growing Japanese-American tensions

"A date that will live in infamy" "A date that will live in infamy"

(December 7, 1941)

The new United Nations The new United Nations

America cranks up the industrial war America cranks up the industrial war

machine

The war on the "Home Front" The war on the "Home Front"

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 20-26.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1940s |

America is brought into the war

1941 America is so unhappy about Japanese action in China and Southeast Asia that it places an embargo on sales of oil, iron and other strategic goods to Japan (Jul)

Roosevelt meets Churchill at sea (Aug), to agree to mutual wartime goals (the Atlantic Charter) ... though America is officially at war with no one at that point

The Atlantic Charter will be adopted by many other countries (Sep) ...

and become the basis of the group termed the "United Nations"

Hitler continues

to ignore America's pro-British" neutrality" ... although a German

Uboat sinks an American

destroyer protecting a merchant convoy (Oct) ... leading Congress to

put aside its Neutraliy Acts

Japan, anxious to reach the resources of Dutch Indonesia – and worried about America's strategic position in the Philppines across Japan's path to those resources – decides to bring America to its knees by

knocking out America's Pacific fleet anchored in Hawaii (Dec); but

Roosevelt is not interested in

any form of surrender ... and gets Congress immediately to declare war

against Japan; a few

days later, Hitler foolishly decides to honor his pact with Japan and

declares war on America;

America is now fully involved in World War Two ... on two fronts,

Europe and the Pacific

|

THE ATLANTIC

CHARTER – AUGUST 1941 |

|

The Roosevelt-Churchill conference and the Atlantic Charter

(August 1941)

Whereas America was still a country at peace, it

had also become clear that the mood in the country was slowly shifting

to the idea of giving support (exemplified in Lend Lease) to the

countries struggling to hold off the aggressions of Fascism. Roosevelt

decided that it was time to discuss diplomatic goals (if not actual war

goals) that America might hold in common with Great Britain.

Thus in mid-August of 1941, Roosevelt met

with Churchill on a battleship anchored just off the Canadian coast to

discuss broad principles or goals that they both wanted to see pursued

in the struggles of the democracies against the dictatorships.

A week later Roosevelt sent a message to

Congress in which he outlined the basic principles agreed on at this

meeting with Churchill: no territorial gain or adjustments that did not

accord with the wishes of the people involved; self-government of all

people; equal access to world trade; economic cooperation for social

advancement; the rebuilding of Europe following the destruction of the

Nazi Empire; freedom of travel on the high seas; and a general

disarmament.

This Roosevelt-Churchill agreement was

issued at first simply as a Joint Declaration on August 14, 1941. This

was an amazing document, considering the fact that America was not

officially at war with anyone at that point. Yet it clearly laid out

war aims – in many ways resembling Wilson's Fourteen Points, which he

had hoped a generation earlier would direct warring parties to a new

and just global peace.

The broader impact of the Atlantic Charter: The "United Nations"

The following month (September) this

document was put forward and unanimously adopted at a meeting in London

of Great Britain and her wartime allies – the governments-in-exile of

Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway,

and Poland, plus representatives from the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia,

and the non-Vichy Free French (representing General de Gaulle) as a

basis of a common set of wartime goals. Thus this agreement proved to

be one of the first steps towards the formation of the United Nations

(at that time describing only a grand military alliance). Also, by this

time the document was being referred to as the Atlantic Charter.1

The Axis Powers interpreted these

diplomatic agreements as a potential alliance against them. Adolf

Hitler saw it as evidence of collusion between the UK and the USA, even

as an international Jewish conspiracy. In the Japanese Empire, the

Atlantic Charter rallied support for the militarists in the government,

who pushed for a more aggressive approach to the UK and US.

1Official

statements and government documents imply that Churchill and FDR signed

the Atlantic Charter. Actually, no signed copies are known to exist. A

British writer, H V Morton, who traveled with Churchill's party on the

Prince of Wales, states that no signed version ever existed. The

document was thrashed out through several drafts, says Morton, and the

finalized text was telegraphed to London and Washington. The British

War Cabinet replied with its approval and a similar acceptance was

telegraphed from Washington.

Winston Churchill's edited copy of the final draft of the

charter

Winston Churchill's edited copy of the final draft of the

charter

No territorial gains. First, their countries [The United States and Great Britain] seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other;

Territorial adjustments. Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

Self-government.

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of

government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign

rights and self government restored to those who have been forcibly

deprived of them;

Equal access to world trade.

Fourth, they will endeavor, with due respect for their existing

obligations, to further the enjoyment by all States, great or small,

victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to

the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic

prosperity;

Economic cooperation.

Fifth, they desire to bring about the fullest collaboration between all

nations in the economic field with the objector securing, for all,

improved labor standards, economic advancement and social security;

A post-Nazi peace.

Sixth, after the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny, they hope to

see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of

dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford

assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in

freedom from fear and want;

Freedom of travel on the high seas. Seventh, such a peace should enable all men to traverse the high seas and oceans without hindrance;

General disarmament.

Eighth, they believe that all of the nations of the world, for

realistic as well as spiritual reasons, must come to the abandonment of

the use of force. Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea

or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or

may threaten, aggression outside of their frontiers, they believe,

pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general

security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential. They will

likewise aid and encourage all other practicable measures which will

lighten for peace loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments.

|

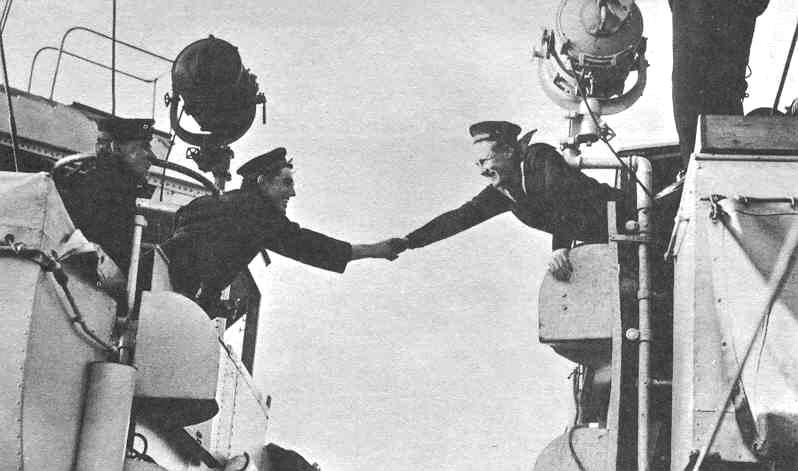

Winston Churchill aboard

HMS Prince of Wales off Newfoundland at the time of the Atlantic

Charter meeting with Roosevelt

USS McDougal

(DD-358) alongside HMS Prince of Wales, to transfer President

Franklin

D. Roosevelt to the British battleship for a meeting with Prime Minister

Winston Churchill. Photographed in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland.

Donation of Vice Admiral

Harry Sanders, USN (Retired), 1969.

USS McDougal

(DD-358) alongside HMS Prince of Wales, to transfer President

Franklin

D. Roosevelt to the British battleship for a meeting with Prime Minister

Winston Churchill. Photographed in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland.

Donation of Vice Admiral

Harry Sanders, USN (Retired), 1969.

U.S. Naval Historical Center

Photograph

British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill meets with President Franklin D. Roosevelt on board USS

Augusta

(CA-31), off Argentia, Newfoundland, August 9, 1941.

Assisting the President is his son, Army Captain Elliot Roosevelt.

D. Roosevelt, Jr., USNR, is at left.

Church service on the

after deck of HMS Prince of Wales, in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland,

during the conference.

FDR and Churchill worshiping

together aboard the Prince of Wales. Standing directly behind

them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall,

U.S.

Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army; Admiral Harold R. Stark,

USN; and Admiral

Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins,

talking with W. Averell Harriman.

FDR and Churchill worshiping

together aboard the Prince of Wales. Standing directly behind

them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall,

U.S.

Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army; Admiral Harold R. Stark,

USN; and Admiral

Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins,

talking with W. Averell Harriman.

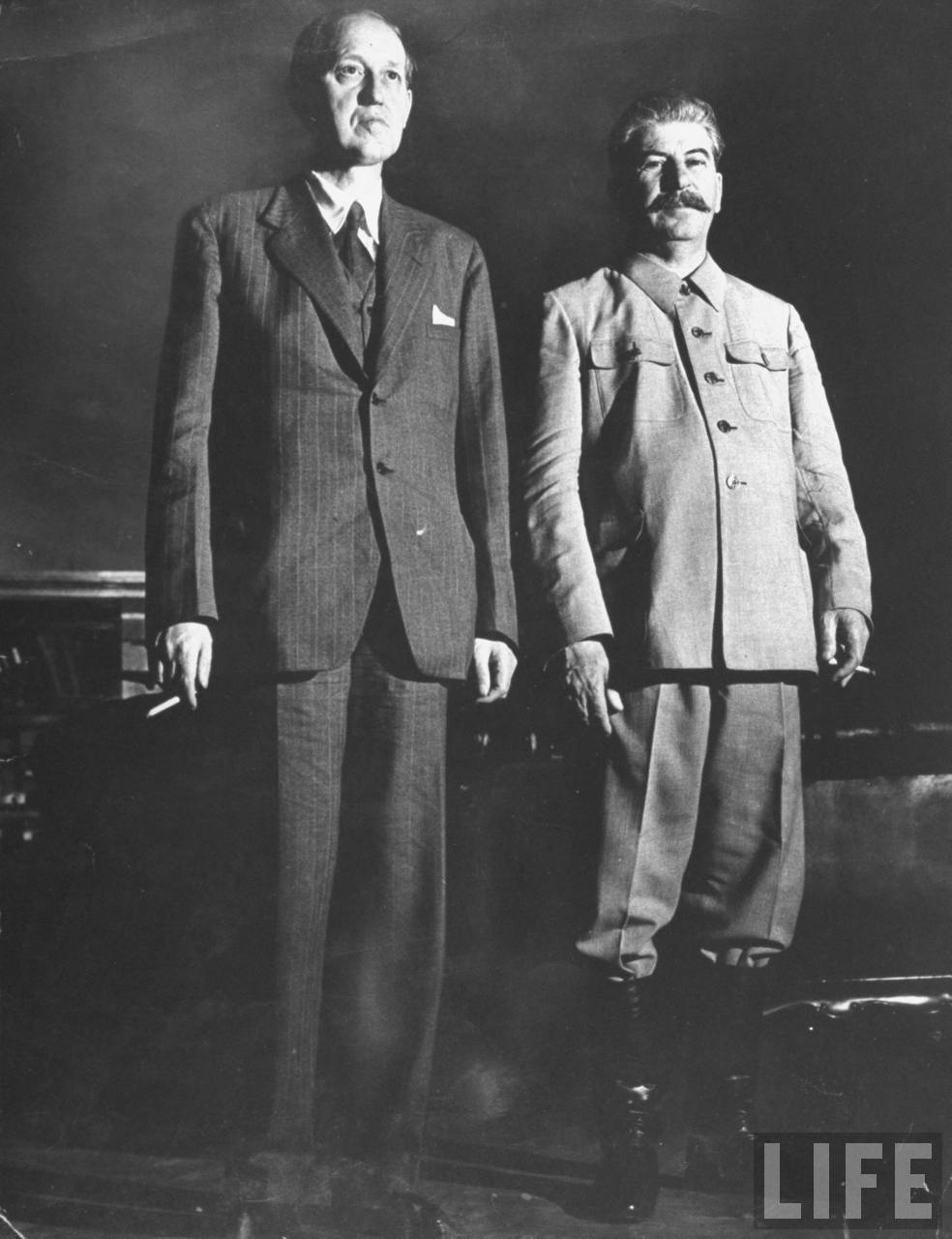

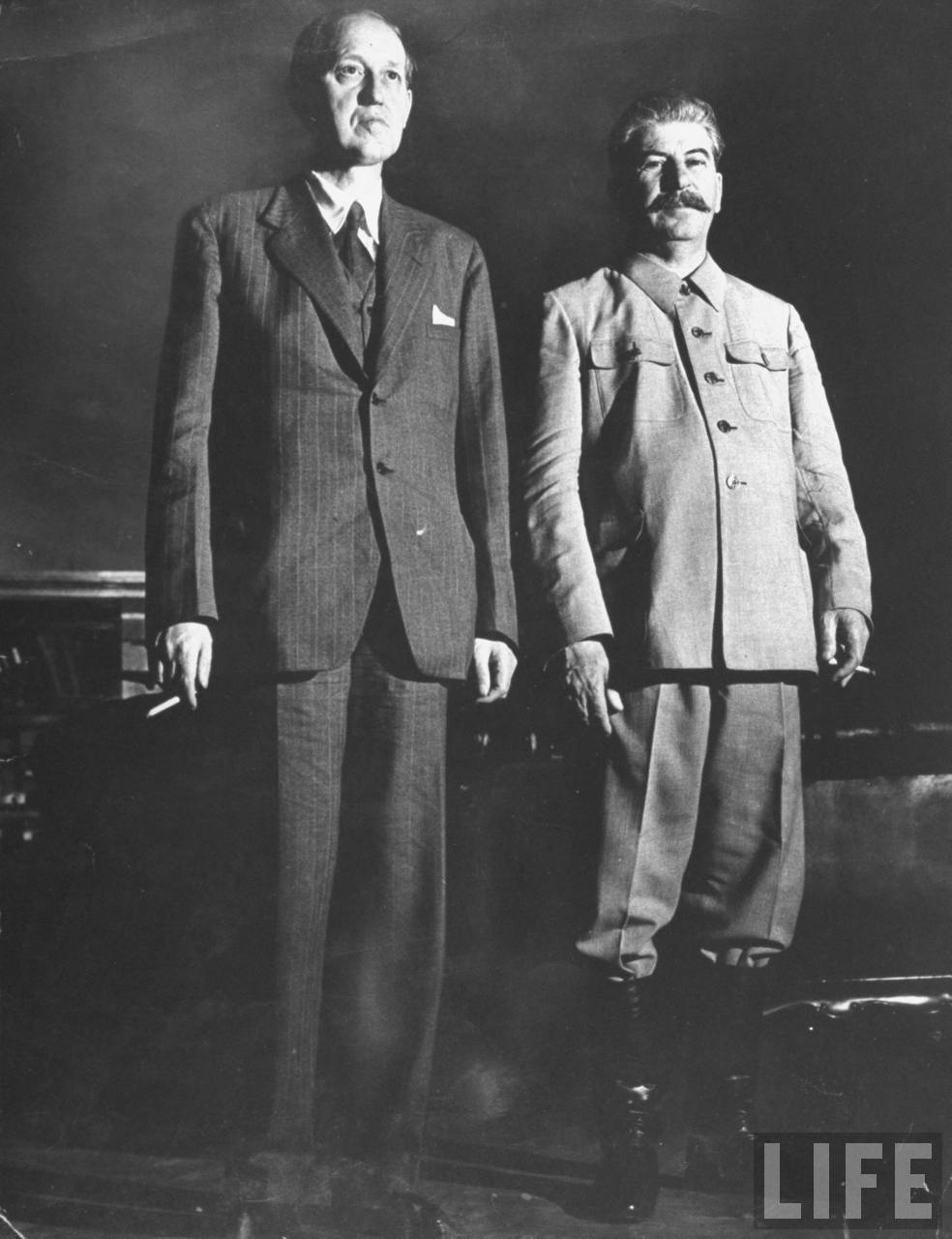

Harry Hopkins meets with

Stalin to investigate the possibilities of working together against Hitler – August 1941

Harry Hopkins meets with

Stalin to investigate the possibilities of working together against Hitler – August 1941

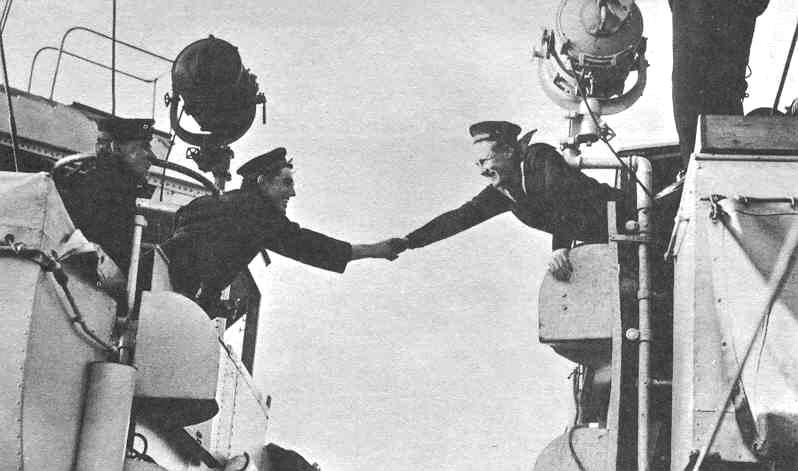

British sailors congratulating

each other for having brought over 2 of 50 "mothballed" American

destroyers

British sailors congratulating

each other for having brought over 2 of 50 "mothballed" American

destroyers

GROWING JAPANESE-AMERICAN TENSIONS |

|

With France's fall to Germany in June of 1940 and

the creation of the Vichy Government in southern France, the French

colony of Indochina was only weakly held by the French. The Japanese

took advantage of this weakness, demanding of the Vichy government

access to Indochina in order to have a base from which to move against

the Chinese enemies in the South of China.

America was alarmed by this expansion of

Japanese power into Indochina and in July decided to place an embargo

on the sale of strategic goods (aircraft parts, key minerals, oil and

scrap iron) to Japan, irritating Japan immensely. This, plus

anti-Japanese racial attitudes reflected in American limits on Japanese

immigration, infuriated the Japanese military leaders, who were

suffering from some of the same racial illusions of greatness that had

infected the Nazis.

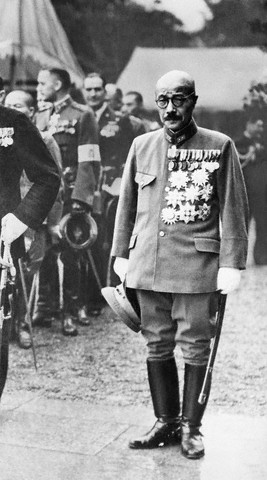

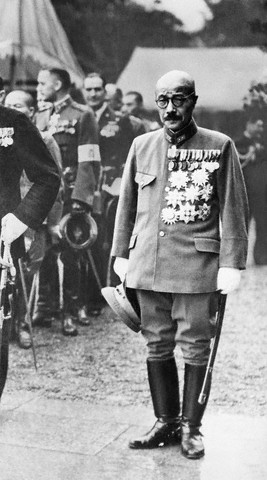

The Japanese military leaders, who

dominated all Japanese politics, were themselves divided on what to do

about the "American problem." Eventually General Hideki Tojo and his

group won the day (with the help of the Emperor Hirohito) and readied

Japan to deliver a huge crippling blow that they were certain would

force America to have to sue for peace – entirely on Japanese terms.

The Japanese would take out the American naval fleet stationed at Pearl

Harbor, destroying all American capabilities in the Pacific and Asia.

At the same time, they would seize the oil-rich Dutch East Indies – and

all the lands along the way, principally the American-protected

Philippines, independent Thailand, British Malaya and the British naval

base at Singapore. The French government at Vichy, forcibly allied with

Hitler's Nazi Germany, had already given its permission to the Japanese

to occupy French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia).

Not all the Japanese were certain that

this plan would work, notably Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the

Japanese navy, Isoroku Yamamoto, who had studied for two years at

Harvard and who offered the opinion that if this strike did not work as

planned, the endeavor would succeed only in awakening a sleeping lion,

with dire results for Japan. Nonetheless he submitted himself to the

majority of his military colleagues and went along with the plan.

|

The Japanese prepare themselves

for a major offensive against the Western democracies in Asia and the Pacific

Imperial

Marines

Imperial

Marines

Gen. Hideki

Tojo

Gen. Hideki

Tojo

Hideki Tojo, Prime Minister

of Imperial Japan (October 1941–July 1944)

Isoroku Yamamoto, Japanese

Fleet Admiral

"A DATE WHICH WILL LIVE IN INFAMY" |

|

Thus at dawn on Sunday morning, December 7th, 1941, without a declaration of war or any warning2

to the Americans, Japanese carrier-based airplanes attacked the Pearl

Harbor naval station, sinking all the battleships anchored there and

wiping out nearly all of the airplanes still parked at the air station.

But the attack had an effect quite opposite what the Japanese had

intended. Instead of forcing America to cringe before Japanese power,

the attack pushed America overnight to a willingness to become a

dedicated fighting nation.

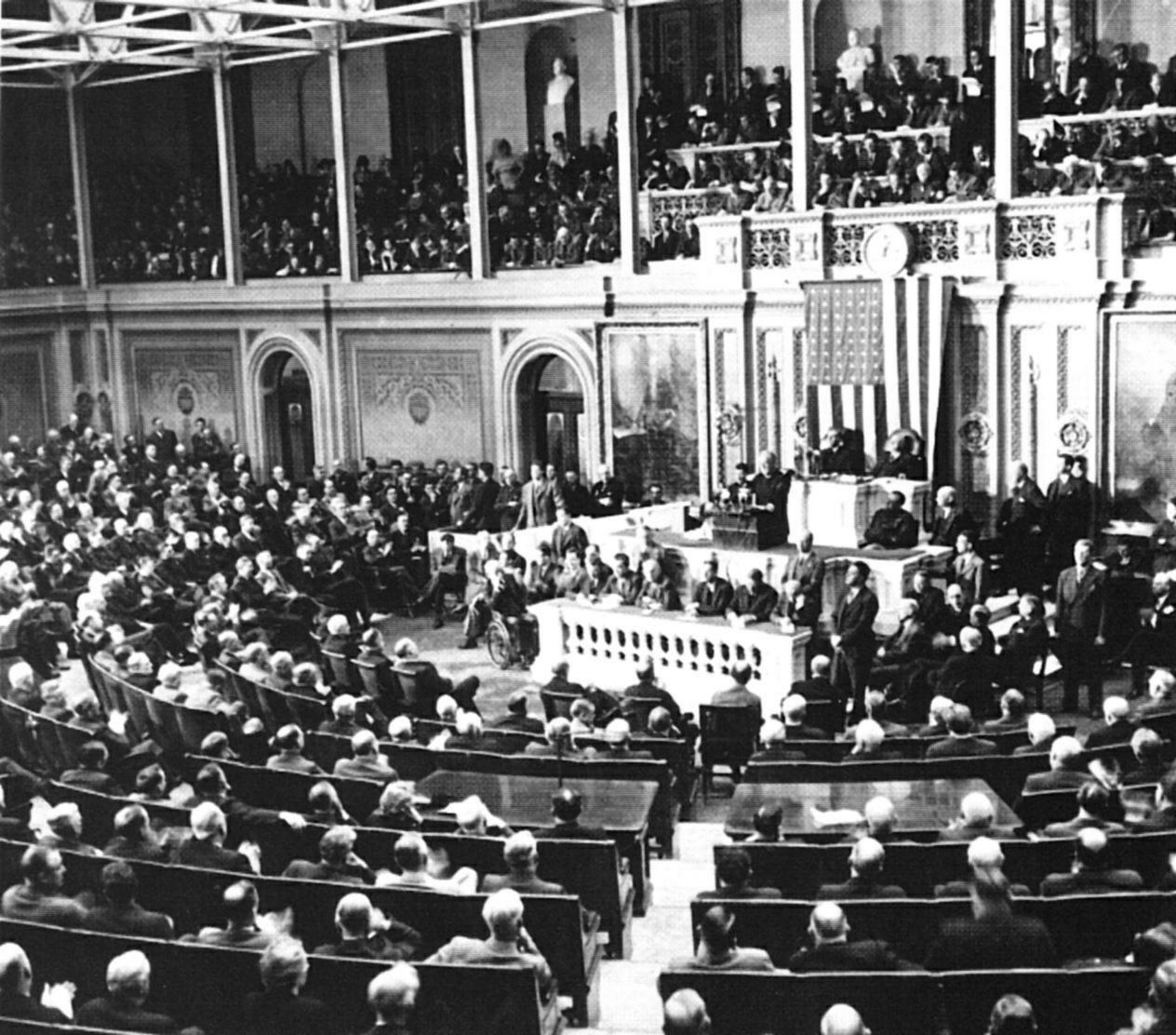

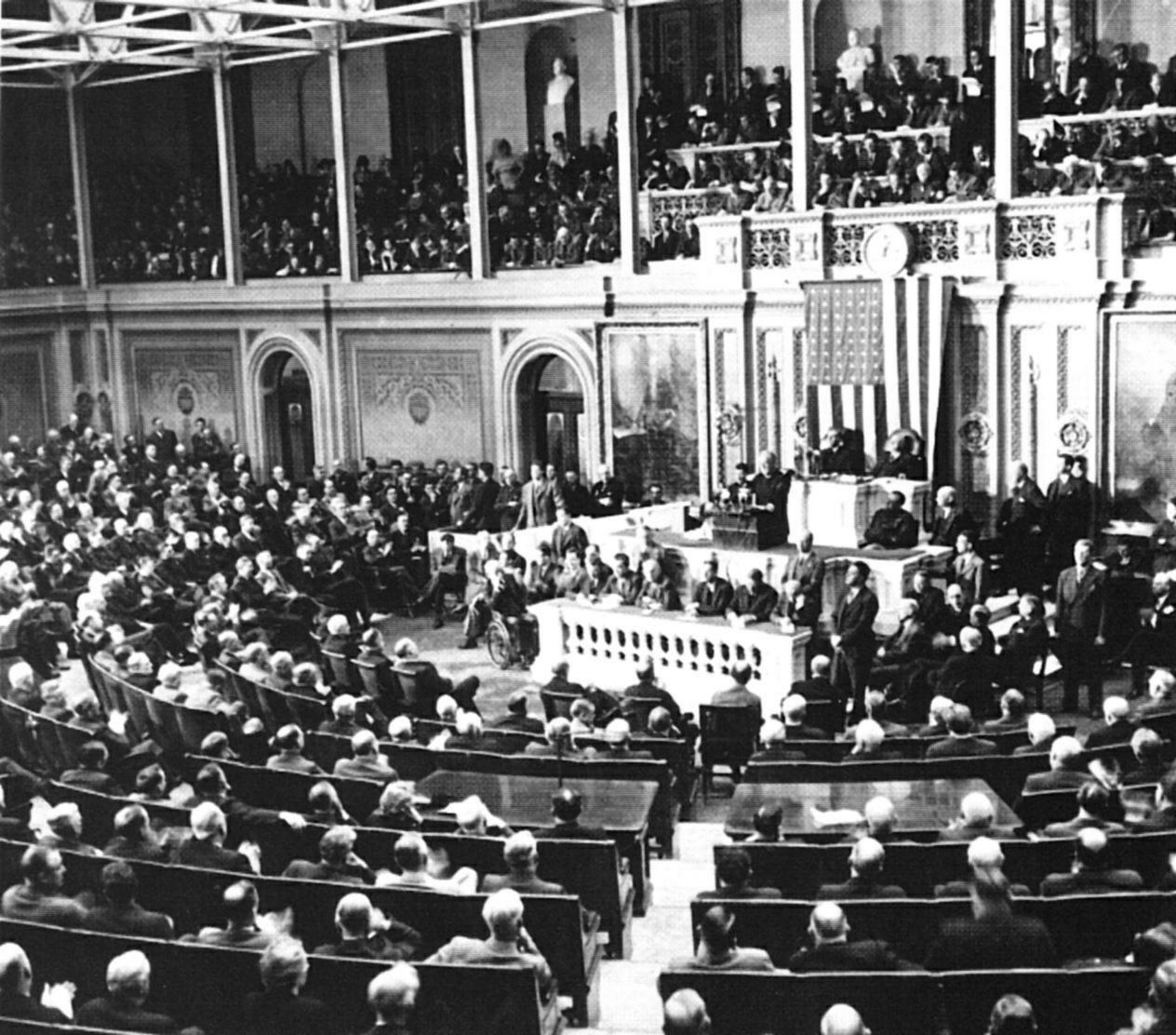

On the following day, December 8th,

Roosevelt stood before Congress to request a declaration of war against

Japan. His speech was unlike Wilson's 1917 speech with Wilson's lofty

rhetoric of high ideals (which Americans by this time were highly

suspicious of) but instead a simple reference to the criminality of

Japan's behavior, begun simply with the statement,

Yesterday,

December 7, 1941 – a date which will live in infamy – the United States

was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the

Empire of Japan.

He mentioned the treachery of the

Japanese in pretending to be negotiating for peace when in fact Japan

had already decided days before to attack America. He did not gloss

over the huge loss of life and military equipment, and pointed out that

this was part of a wider Japanese aggression, timed with an attack in

the Philippines and other areas in the Pacific. His appeal was strictly

to the sense of national outrage, and to the American spirit that would

never let Japan get away with such treachery. Thus:

As Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense.

But always

will our whole nation remember the character of the onslaught against

us. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated

invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through

to absolute victory.

I believe

that I interpret the will of the Congress and of the people when I

assert that we will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will

make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again

endanger us.

Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory and our interests are in grave danger.

With

confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounded determination of our

people, we will gain the inevitable triumph so help us God.

There it was, plainly said. We

Americans would fight – not to save the world for some kind of high

ideal, but rather to defend ourselves from the treachery that

threatened us, our territory, our interests. It was a hard and precise

piece of political realism. And we were ready to back that declaration

– with our lives – so help us God.

Congress's vote for war was unanimous

in the Senate and only one vote short (Liberal feminist Jeanette Rankin

opposed) of being unanimous in the House. At 4:00 p.m. on the 8th of

December America was formally at war, though at this point only against

the Japanese.

Hitler declares war on America

Several days later Hitler, puffed up

with his growing sense of military genius, announced that he was

respecting the Tripartite Pact with Japan in declaring that a state of

war now existed between Germany and the United States. So whatever

America's hesitant feelings had been previously about the war in

Europe, they no longer mattered. By Hitler's own bizarre decision,

America was at war not only with the Japanese but also with the Germans.

"With God's help, we will triumph"

This was not a good time for America to

be getting into a war against two successful empires, with few proven

allies for America to count on (France had been knocked out; Great

Britain and Russia were not looking very good at this point) and

America's own military was in a deplorable state of unpreparedness. But

the spirit of America in 1941 was such that Americans chose not to look

at the situation as worldly eyes would see things (very bad indeed) but

as the higher vision of God might see things: the need to take a stand

against evil – and trust in God to support us in our struggle. When

Roosevelt added the words "so help us God" at the end of his address

requesting of Congress a declaration of war, that was not merely

religious cant, that was an important call to connect "the unbounding

determination of our people" with the vital aid and guidance of God.

America was determined to gain the inevitable triumph ..."so help us

God."

2Japanese

civilian diplomats had been in Washington claiming to want to negotiate

an improvement in Japanese-American relations, when they were

instructed instead to deliver a declaration of war. But they were still

working on a translation of the declaration when the attack got

underway in Hawaii.

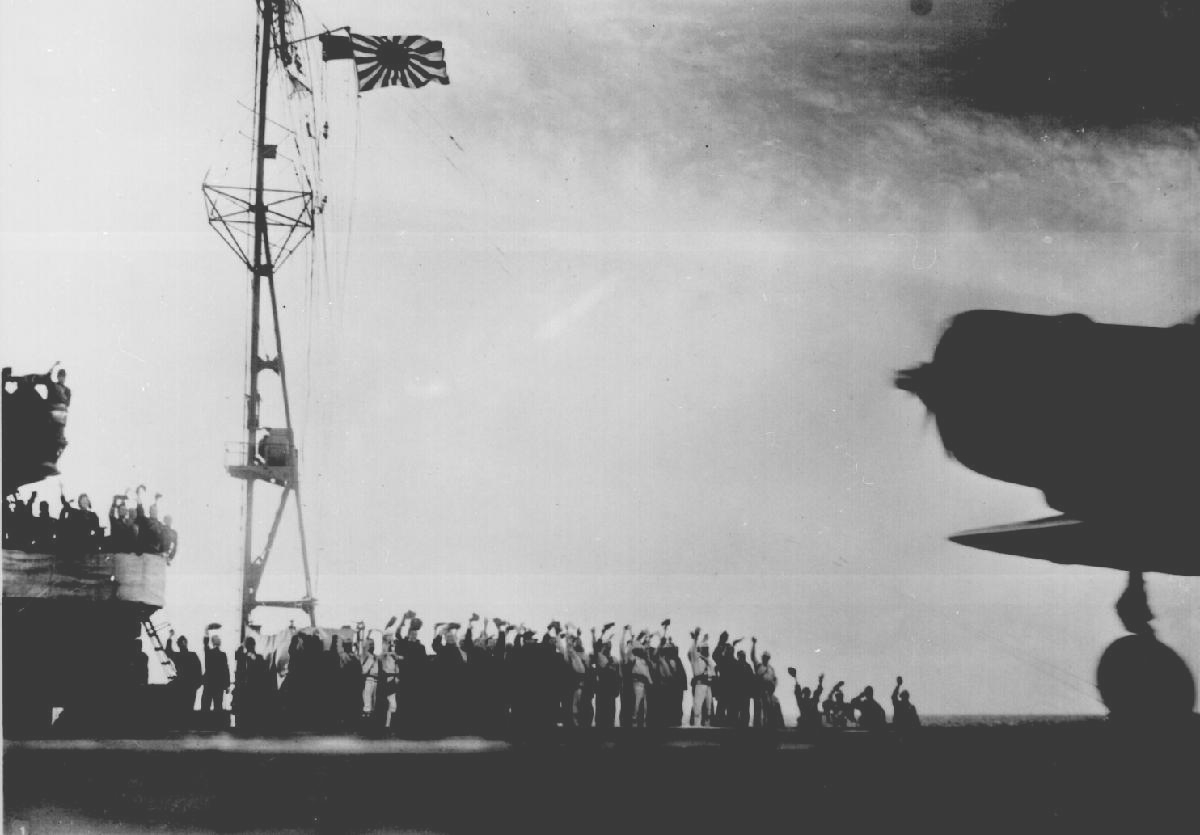

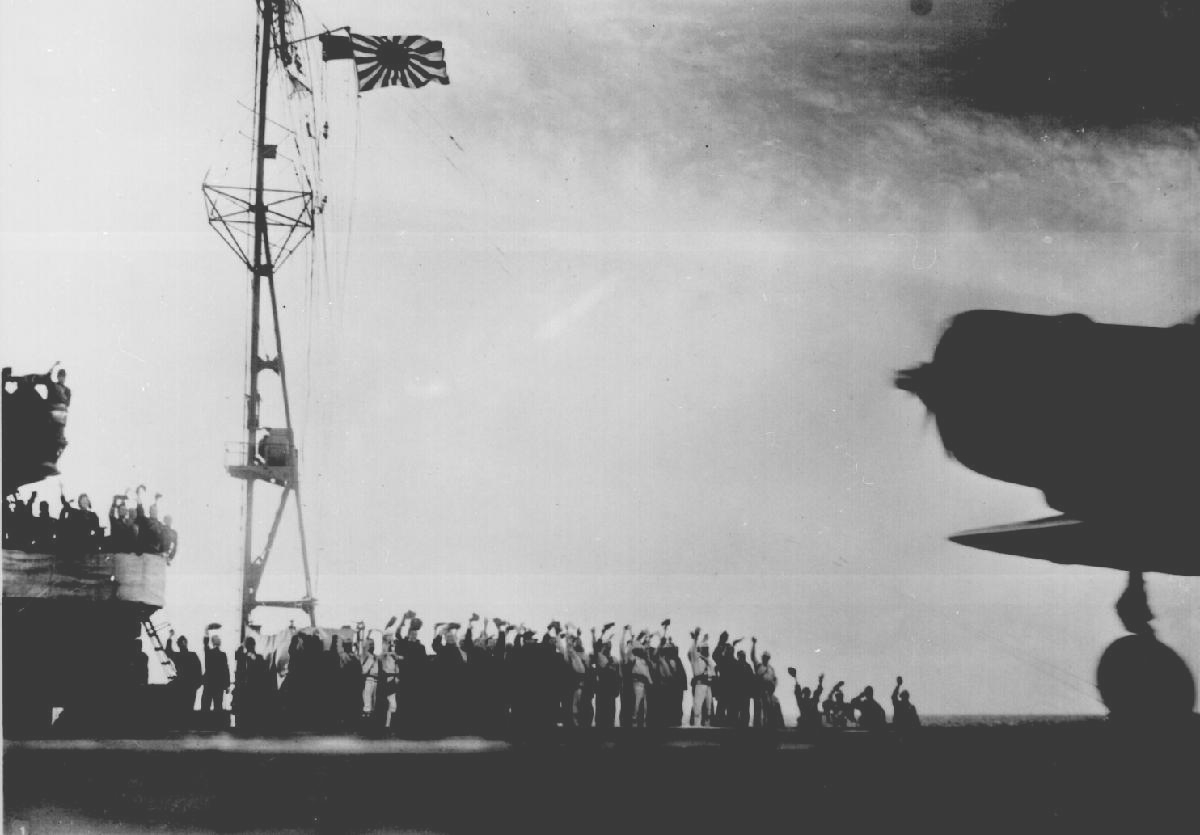

Captured Japanese photograph taken aboard

a Japanese carrier before the

attack on

Pearl Harbor,

Hawaii, December 7, 1941. Photograph from a Japanese

plane of Battleship Row at the beginning of the attack. The explosion in the center

is a torpedo strike on the USS Oklahoma

Photograph from a Japanese

plane of Battleship Row at the beginning of the attack. The explosion in the center

is a torpedo strike on the USS Oklahoma

Captured Japanese photograph taken during

the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. In the distance,

the

smoke rises from

Hickam Field.

Japanese Aichi D3A1 "Val"

dive bombers of the second wave preparing for take off. Aircraft carrier Soryu

in the background.

"USS Shaw (DD-373)

exploding during the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor."

The USS Arizona (BB-39)

burning after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941. USS Arizona sunk

at Pearl Harbor. The ship is resting on the harbor bottom. The supporting

structure

of the forward tripod mast has collapsed after the forward magazine

exploded.

The US Naval Air Station

at Pearl Harbor under Japanese attack

Franklin Roosevelt asks Congress

to declare war on Japan – December 8, 1941

At 4 P.M. that same

afternoon,

President Roosevelt signed the declaration of war. Furious at the

brutal attack and drawing inspiration from Roosevelt's address, the American

people united behind a massive mobilization for war.<

President Roosevelt signing

the declaration of war against Japan – December 8, 1941

Adolf Hitler delivers a speech

to the Reichstag on the subject of Roosevelt and the war in the Pacific, declaring war on the United

States – December 11, 1941

|

The Atlantic Charter as the moral foundation of the new United Nations

On January 1st, 1942, the United Nations of

twenty-two countries around the world were formed into an alliance in

order to oppose the Fascist or Axis nations of Germany, Italy and

Japan. These United Nations – led by the Big Four of America, Great

Britain, Russia and China – signed the Atlantic Charter as a joint

Declaration by the United Nations and committed themselves to pursue the

war with the aim of a total victory against the Fascist enemy. Over the

next few years an even greater number would sign on as members of the

"United Nations."

The major guiding principles of this new

military alliance, the United Nations, were to be those of the Atlantic

Charter. This document would also become a foundational document for

the organization of that same name that would be formed at war's end.

The Atlantic Charter and Declaration

outlined how an anti-Fascist military alliance was to operate – and how

a post-war world would be shaped and also operate. The latter part

would be particularly important in the way in which after the war much

of the world would indeed take shape, especially economically.

However, politically the Atlantic Charter

would ultimately prove to be much more Idealistic than any of the great

powers, when pressed for specifics, were willing to support at the end

of the War. This was particularly the case again with respect to the

rights of national self-determination of people (the old Wilsonian

ideal). Germany would lose a lot of its ethnic territory (which Poland

would gain after expelling its German population); Russia's grab and

absorption into the Soviet Union of the Baltic countries of Estonia,

Latvia and Lithuania and the eastern half of Poland would be left

unchallenged; Indochina would remain in French hands (Vietnam would not

be granted the national independence it sought); Indonesia would remain

in Dutch hands, etc.

|

America was back in business again, very focused

on the clear goal of defeating – at all costs – the Fascism that had

destroyed the peace of the world.

And to get the job done, a much-revived

private capitalism was going to work very closely with Roosevelt's

rather socialist state, in producing the means to destroy enemy

Fascism. Under such cooperation, the federal government funded the

building of new industrial plants, encouraged industrial producers to

work together (and thus had to suspend the antitrust laws outlawing

just such behavior) in order to optimize war production, much to the

annoyance of some of FDR's New Deal supporters who still considered

industrial capitalism to be a vile philosophy!

Industrial production got off to a

relatively slow start, but picked up the pace rapidly. Automobile

plants switched to the production of war goods, such as Chrysler, which

turned to the mass production of tanks. Industrial companies grew

rapidly and in the last years of the war were producing war goods at an

astronomical rate. For instance, the Calship Yards in Los Angeles in

the last year of the war (January-August 1945) alone produced 247

Victory ships, more than one huge ship coming into operation per day.

In Stratford Connecticut, another industrial company alone produced

some 6,000 corsair fighter planes during the course of the war.

With men entering military service in

mass numbers, the country now found itself short in manpower, and

turned to womanpower. The country's vocational schools turned to the

converting of traditional secretaries, housewives, etc. into

assembly-line specialists, welders in shipyards, etc. Indeed, the

Women's Army Corps had WACs fly bombers from American assembly plants

to airfields overseas (principally England) to put them in the hands of

the men who would then conduct the bombing runs over German-occupied

Europe.

|

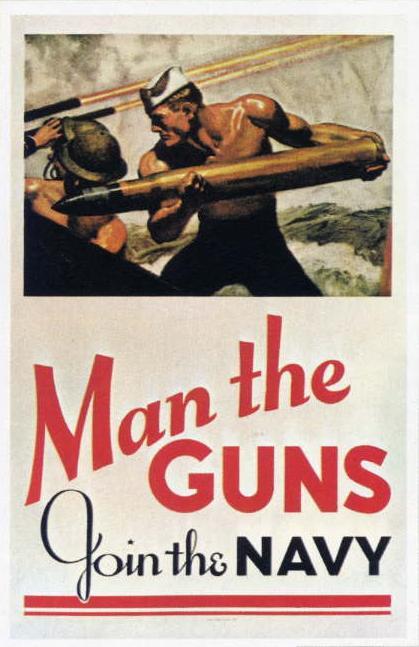

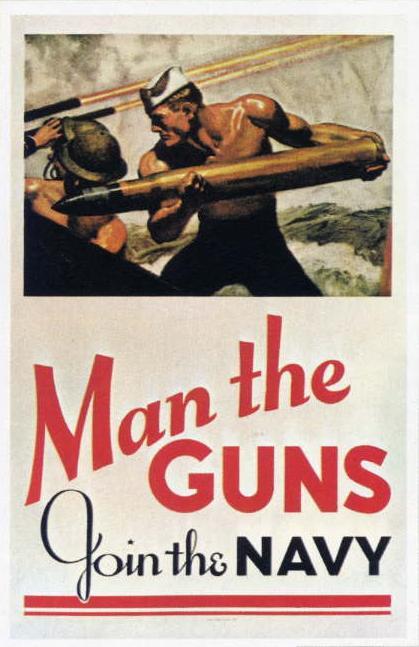

An Army recruiting poster

(same one used in World War One!)

Library of

Congress

A Navy recruiting poster

A Navy recruiting poster

Library of Congress

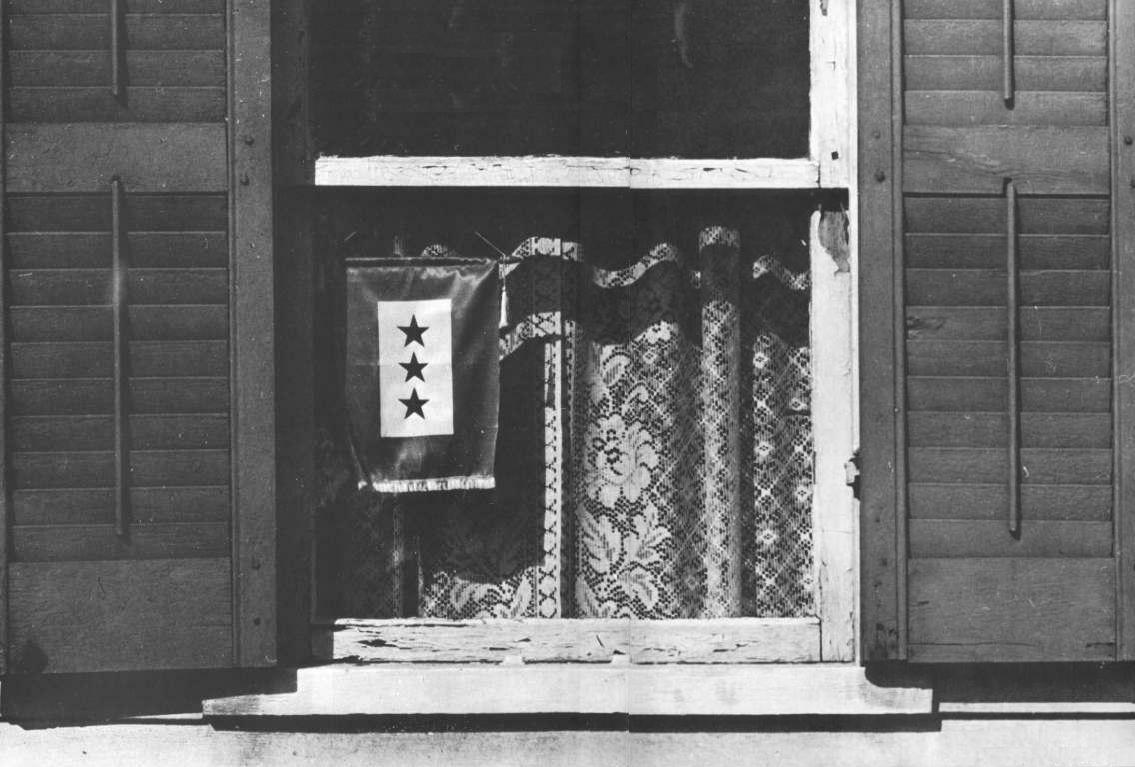

New recruits in Macon, Georgia,

heading off to training in Virginia

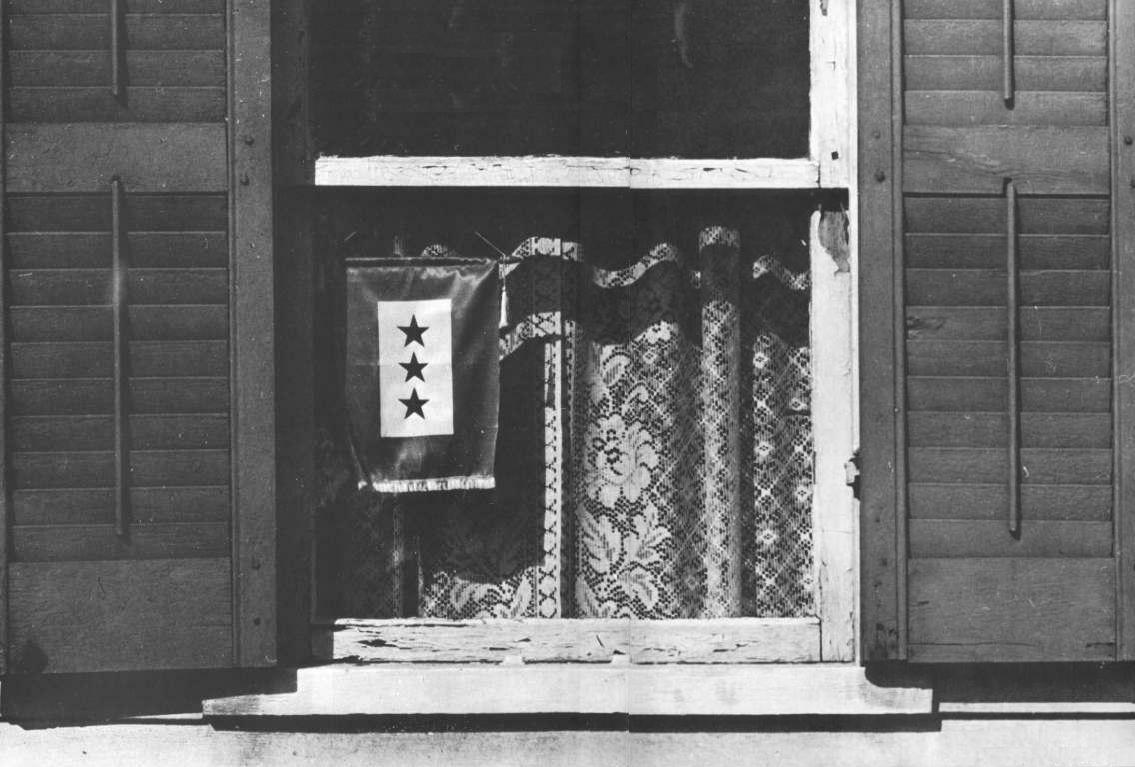

A Home with three men in

the armed service

Library of Congress

Eleanor Roosevelt with US

troops – 1942

Hollywood actor (age 33) Jimmy

Stewart

joining the Army in March of 1941

(8 months before Pearl

Harbor)

He had just won the 1940

Oscar for his part in The Philadelphia Story. He

was of an old Pennsylvania military family, and had already clocked in

over 400 hours of flight time. He would become a highly decorated

Army Air Corps bomber pilot and full colonel in rank, having

officially led 20 bombing missions over Germany (and others

unofficially!). He would eventually retire from the Air Force

Reserves in 1968 as a Major

General. |

CRANKING UP THE INDUSTRIAL WAR MACHINE |

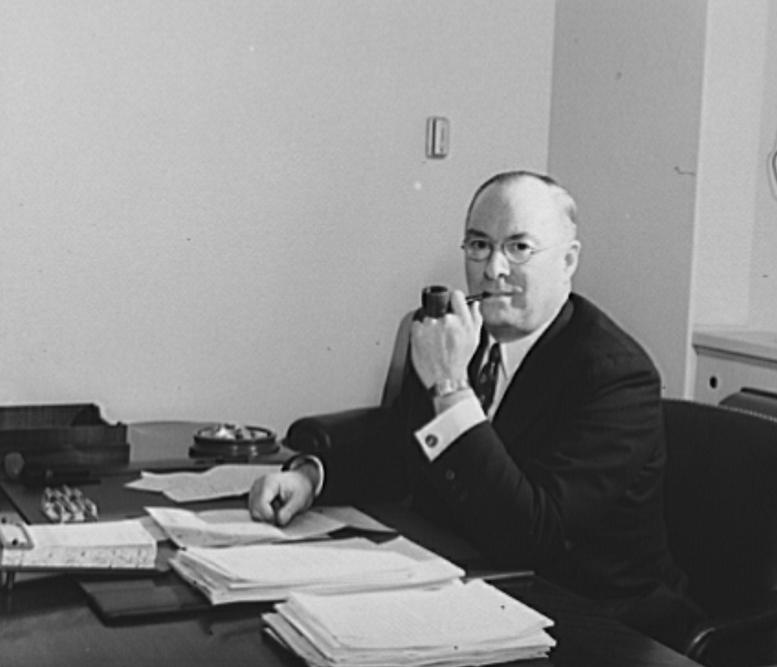

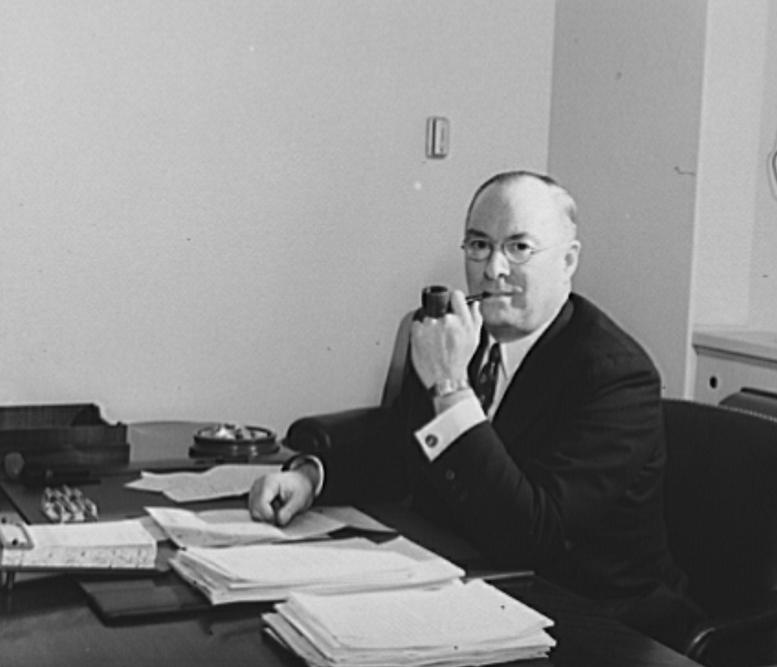

Donald Nelson (of Sears,

Roebuck & Co.) headed the War Production Board

(1942-1944)

Donald Nelson (of Sears,

Roebuck & Co.) headed the War Production Board

(1942-1944)

|

The

Federal government funded

the building of new industrial plants, encouraged industrial producers

to work

together (and thus had to suspend the antitrust laws outlawing just

such behavior) in order to optimize war production ... much to the

annoyance of FDR's New Deal supporters who still considered industrial

capitalism to be a vile

philosophy!

|

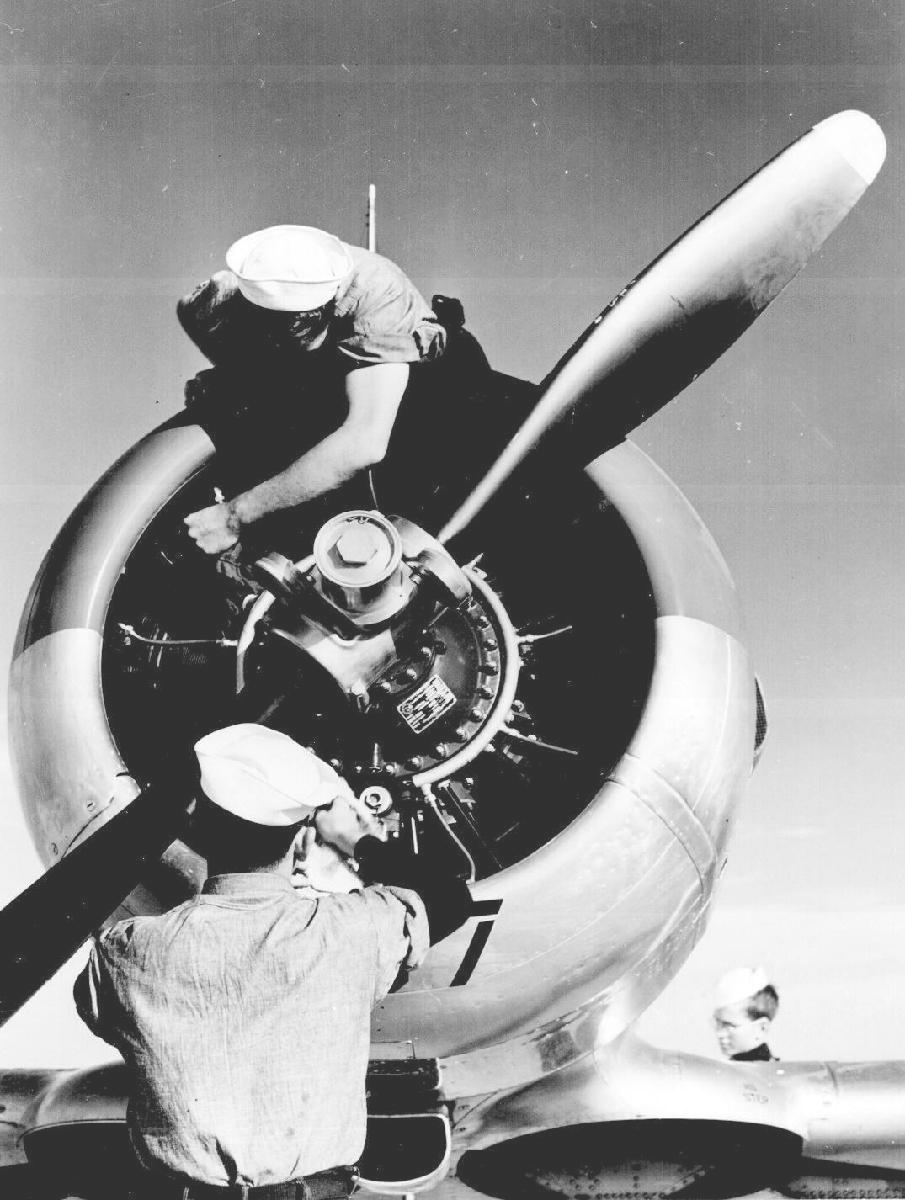

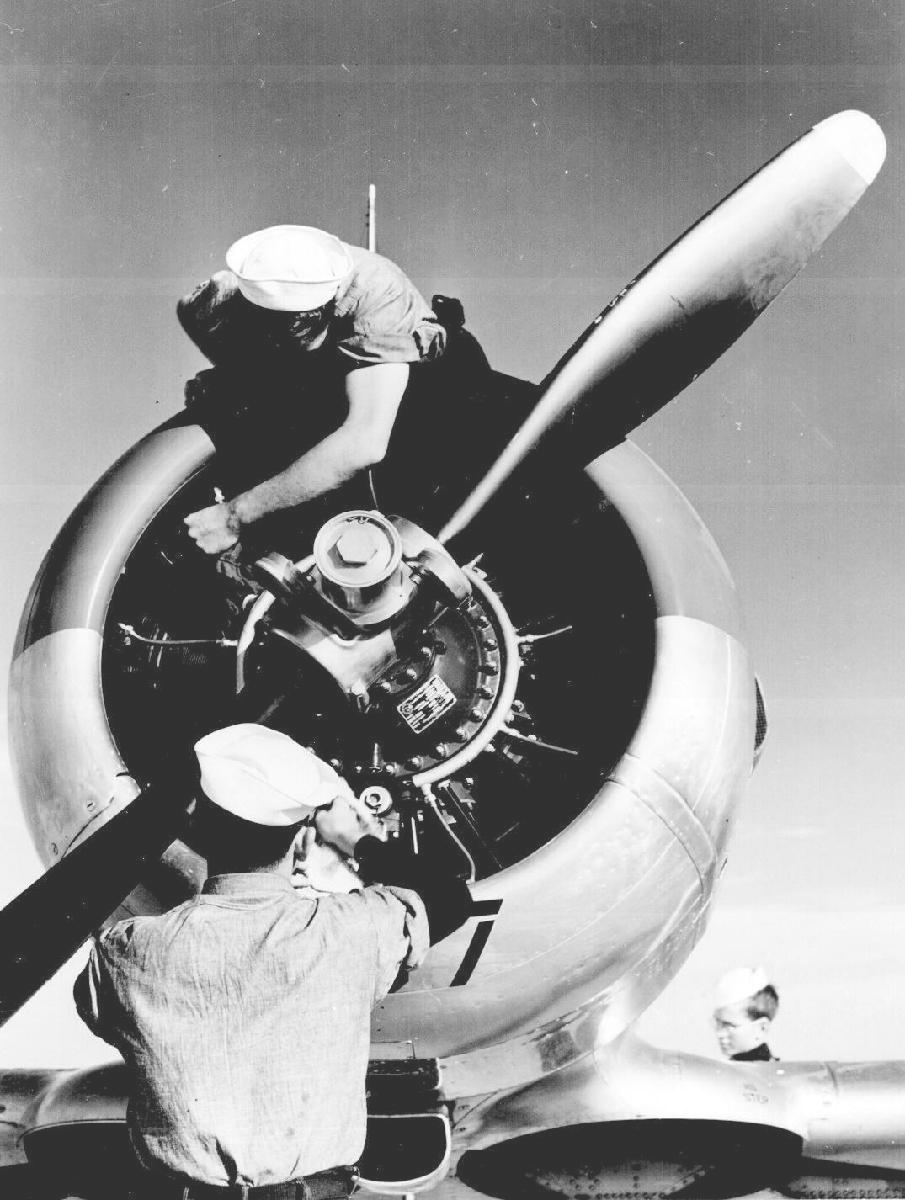

"Mechanics check engine of SNJ at Kingsville

Field, NATC, Corpus Christi, Texas."

Lt. Comdr. Charles Fenno Jacobs, November

1942.

National Archives

80-G-475186

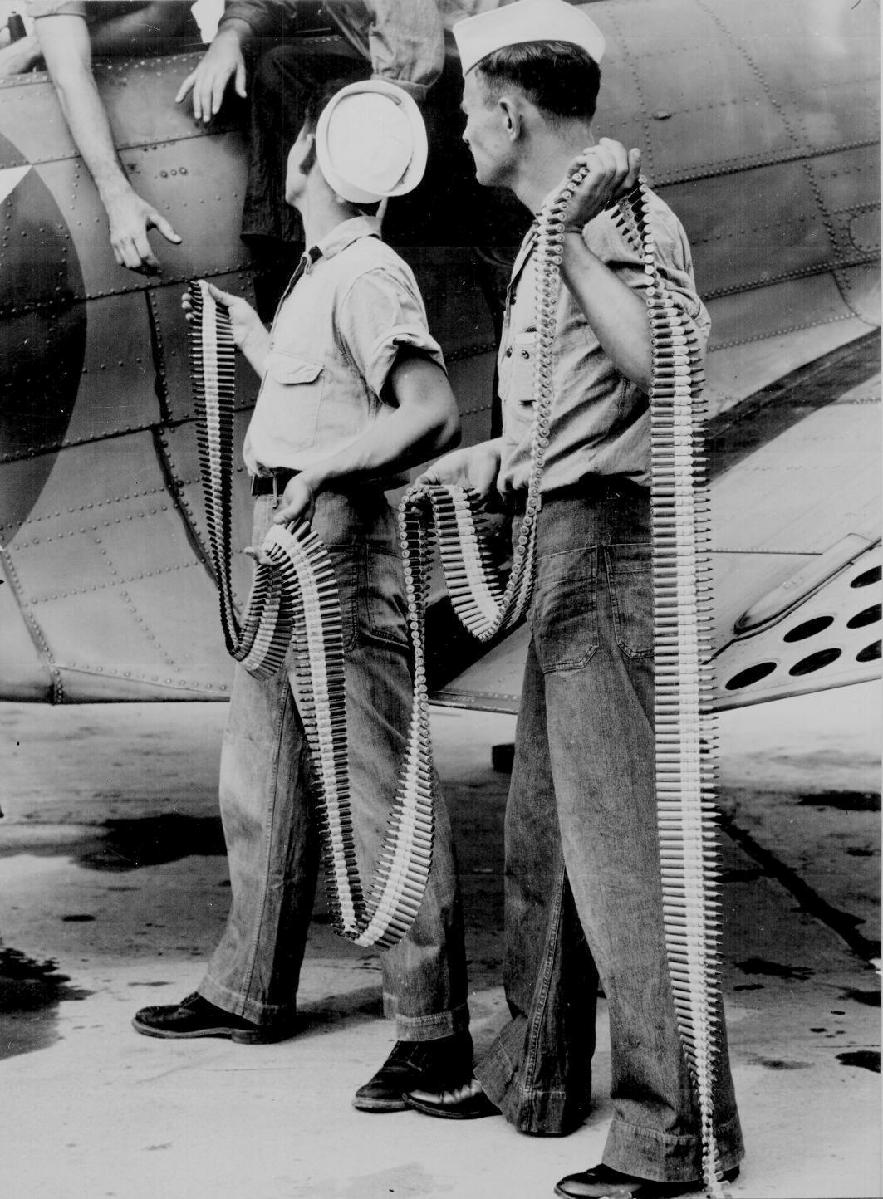

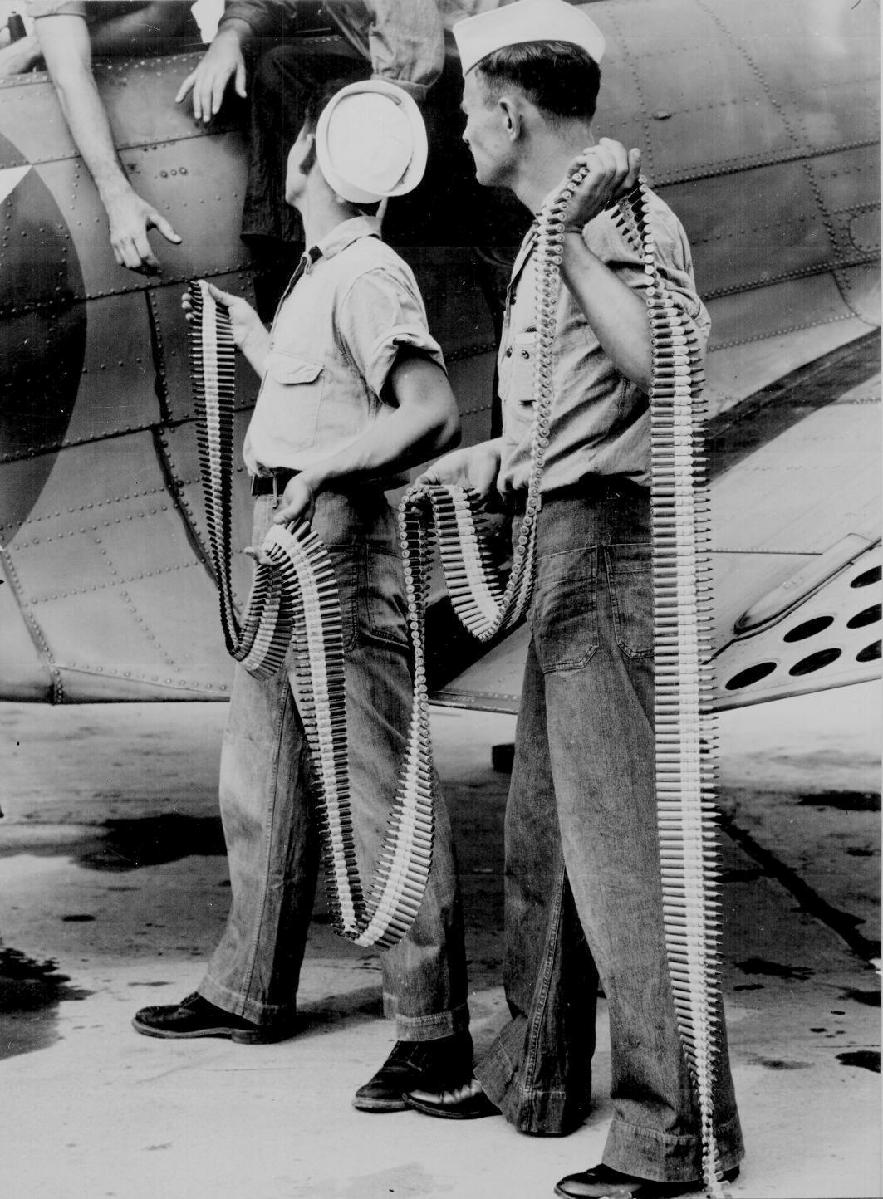

"Ordnancemen loading belted cartridges

into SBD-3 at NAS Norfolk, Va." September 1942

National Archives

80-G-472528

"Man working on hull of U.S. submarine

at Electric Boat Co., Groton, Conn."

Lt. Comdr. Charles Fenno Jacobs, August

1943.

National Archives

80-G-468517

"Launching of USS ROBALO 9 May 1943,

at Manitowoc Shipbuilding Co., Manitowoc, Wis."

National Archives

80-G-68535

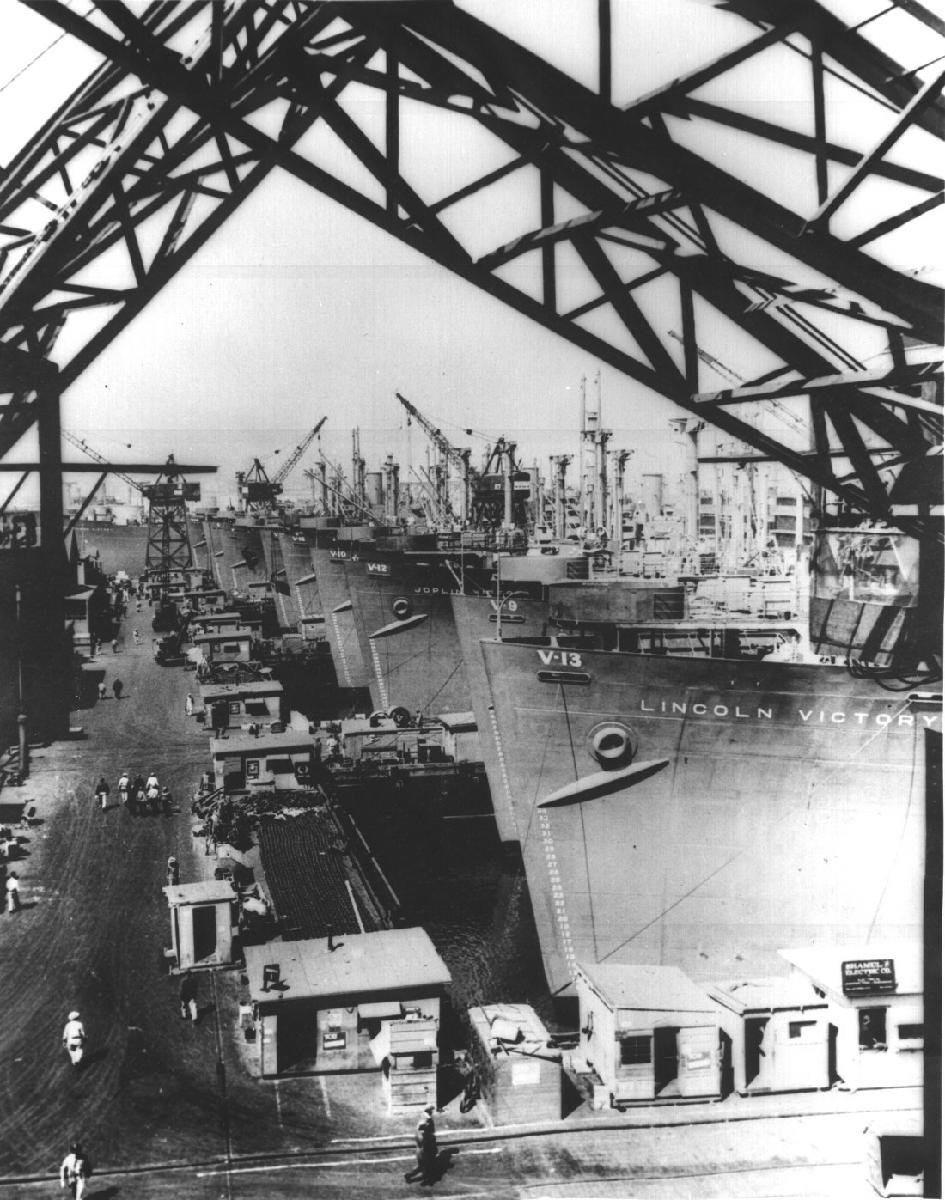

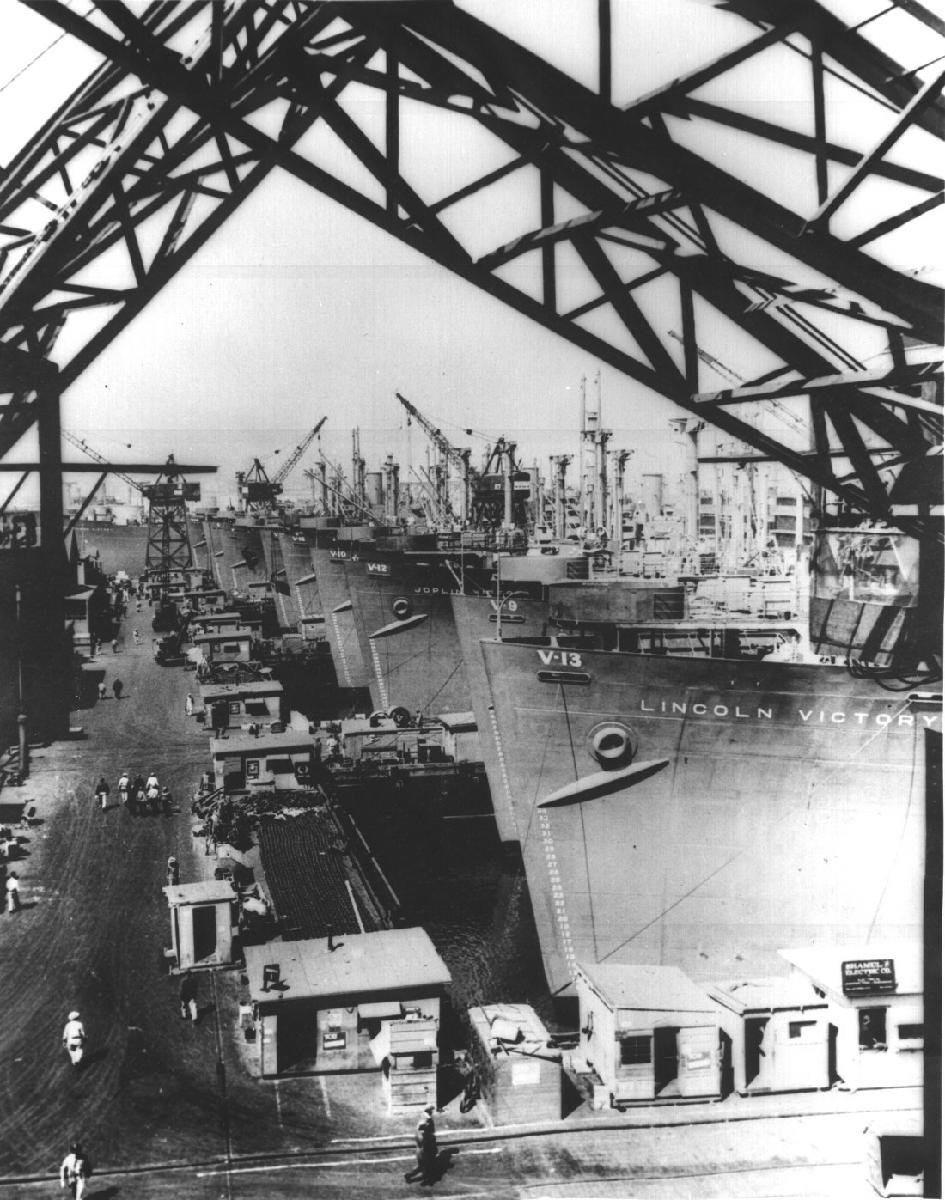

"Victory cargo ships are lined up at

a U.S. west coast shipyard for final outfitting before they are loaded with supplies for Navy

depots and advance bases in the Pacific." Ca. 1944

National Archives

208-YE-2B-7

The construction of Victory

ships at the Calship Yards, Los Angeles (247 were built in the

first 212 days

of 1945)

Chrysler tanks being checked

out as they come off the assemby line (Chrysler produced

25,507 in total)

Some of the 6000 Corsair

fighter planes produced at this plant in Stratford, Connecticut

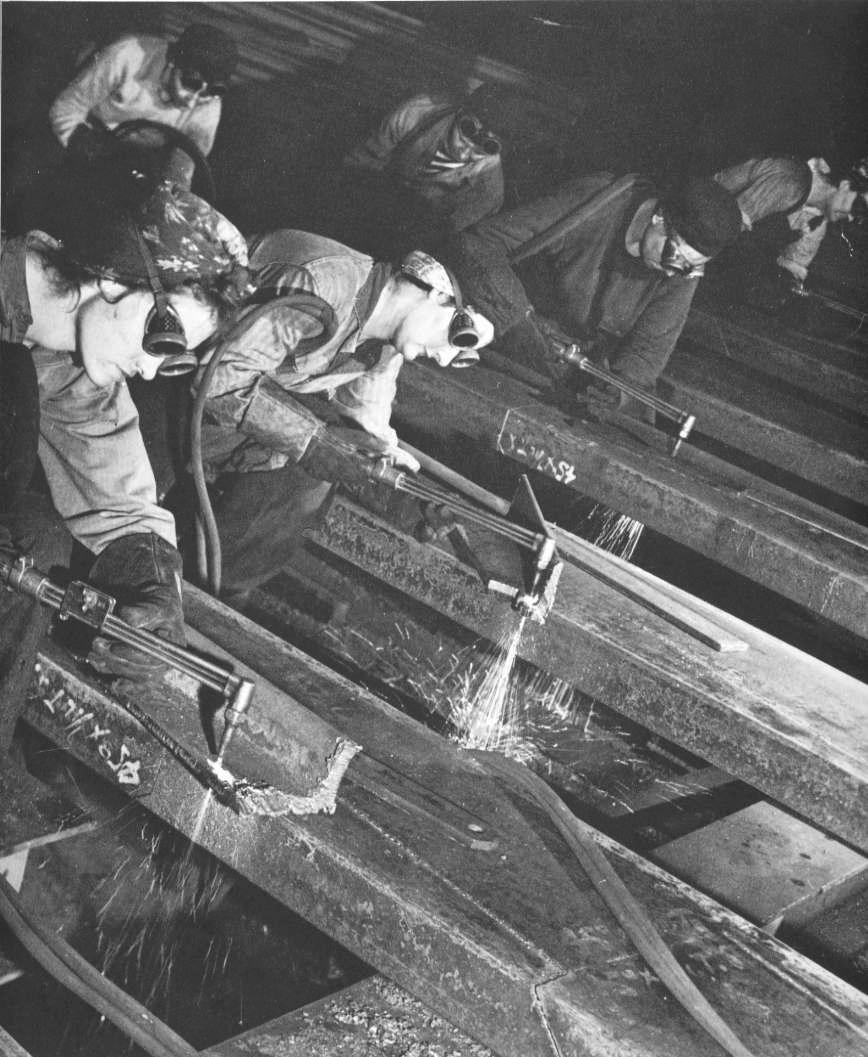

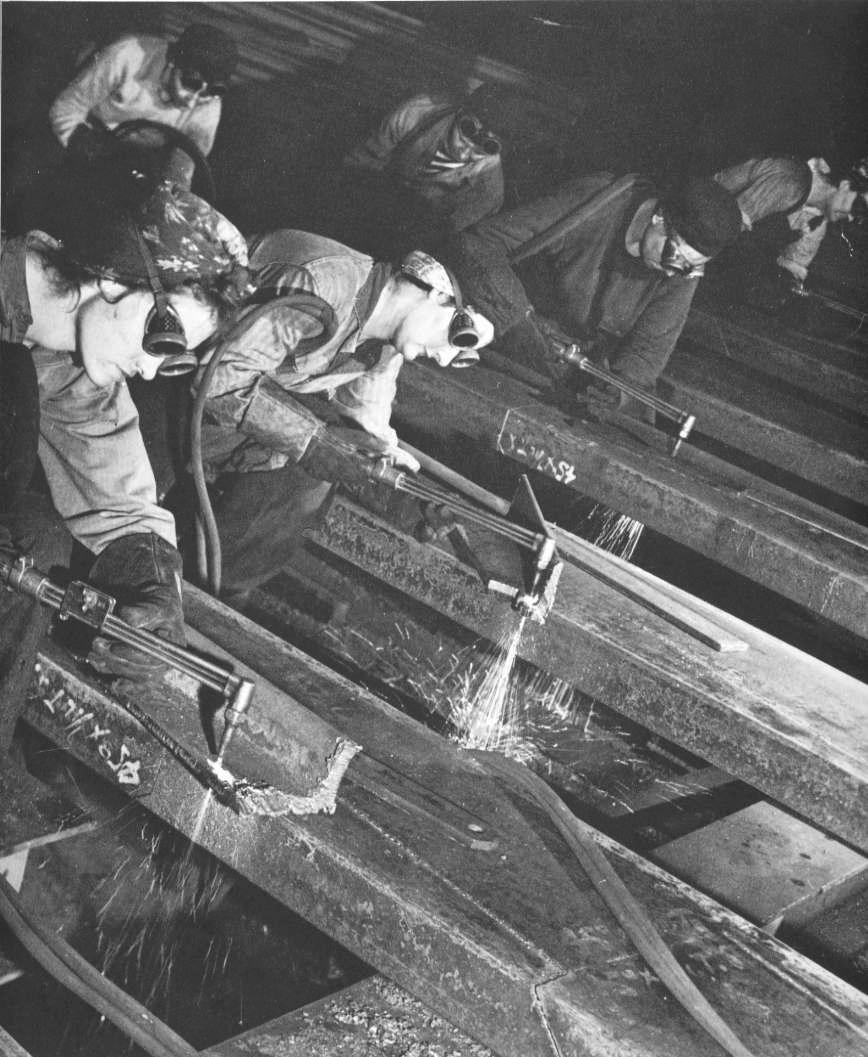

With

men drawn away to war

overseas, women are recruited to help make up the industrial labor shortage

Secretaries, housewives,

women from all over central Florida are getting into vocational schools to learn

war work. Typical are these in the Daytona Beach branch of the Volusia county

vocational school – April 1942

National Archives

"Line up of some of women welders including

the women's welding champion of Ingalls [Shipbuilding Corp., Pascagoula, MS]."

Spencer Beebe, 1943.

National Archives

86-WWT-85-35

Women cutting armor

plating

Female riveter at Lockheed

Aircraft Corp., Burbank, CA

National Archives

The Women Take Up the Task

of War Production (Bomber noses) at Douglas Aircraft, Long Beach, California

National Archives

A

number of women donned

the uniform of the WACs (Women's Auxiliary Corps)

WACs delivering bombers to

England for action

WACs delivering bombers to

England for action

Smithsonian

Institution

THE WAR ON THE "HOME FRONT" |

|

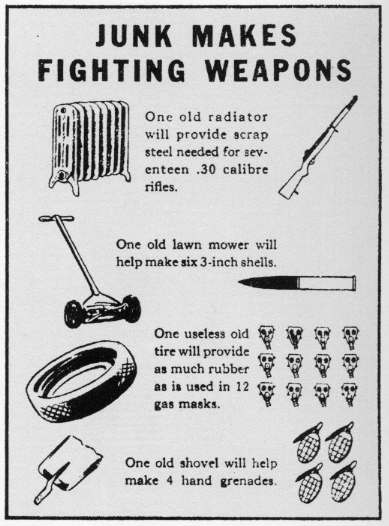

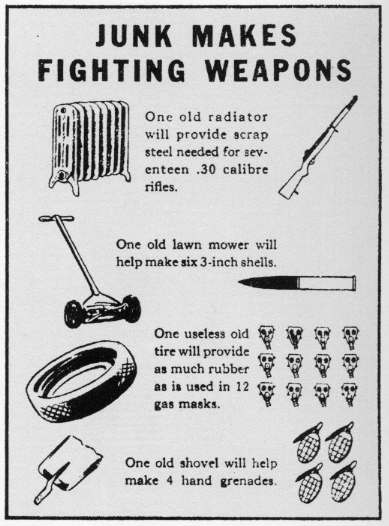

Even

beyond that, all Americans were called to do their part on behalf of

the men fighting for their nation. Scrap of all sorts (paper, rubber

tires, tin cans, brass locks, scrap steel, even the metallic toothpaste

tubes) were collected for conversion into military material.

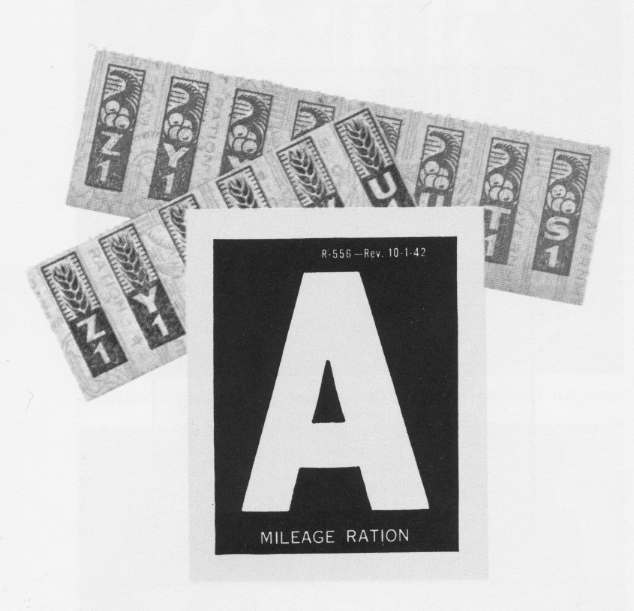

Furthermore food (which was being produced at a slower rate with so

many farm boys in uniform) was rationed, everything from meat, to

sugar, to can goods, virtually everything sold in a grocery store.

Money made no difference in the amount a family could buy, because all

families were under a point system of rationing, receiving on the basis

of family size just so many points in coupons, coupons that had to be

submitted with each purchase of food.

Integrity on the Home Front

But

by and large, the call to patriotic duty on the part of everyone was so

strong that relatively little cheating or corruption found its way into

American operations. But to make doubly sure, Missouri Senator Harry

Truman headed up a Congressional committee that examined closely the

accounting books of the industrial companies that were receiving

millions of dollars in government contracts for their war-materials

production. But amazingly things ran on a quite clean basis, especially

considering the vast amounts of money circulating because of war

production.

|

Thanks to the Senate's "Truman

Committee," there was a very close watch over the huge government funding to make

sure that it was used properly in advancing the American war industry.

Thanks to the Senate's "Truman

Committee," there was a very close watch over the huge government funding to make

sure that it was used properly in advancing the American war industry.

Miller Nichols Library -

University of Missouri – Kansas City.

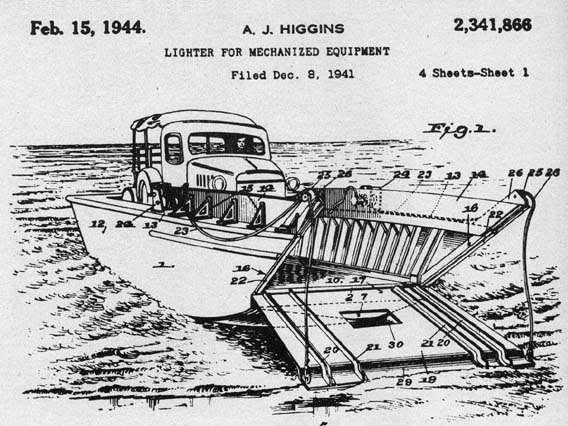

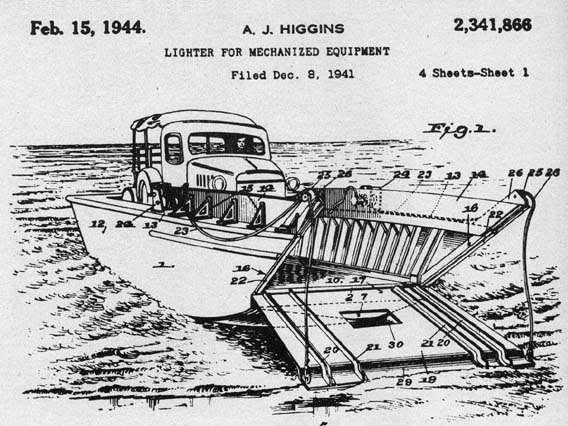

One of the most amazing

developments

of the industrial ingenuity of American industry was the "Higgins boat," the plywood landing craft

(20,000 built) that would be invaluable in getting troops and supplies

from the ships to the beach

|

A.J.

(Andrew Jackson) Higgins

had to fight the bureaucratic resistance of the Bureau of Ships which refused to accept his design, favoring their own version

which proved unstable and prone to sinking. Thanks to the Truman

Committee, Higgins was finally given

the go-ahead to build the boats that Eisenhower would come to credit as a saving piece of the entire

war effort, without which the war would have been delayed ... if not even

unwinnable.

|

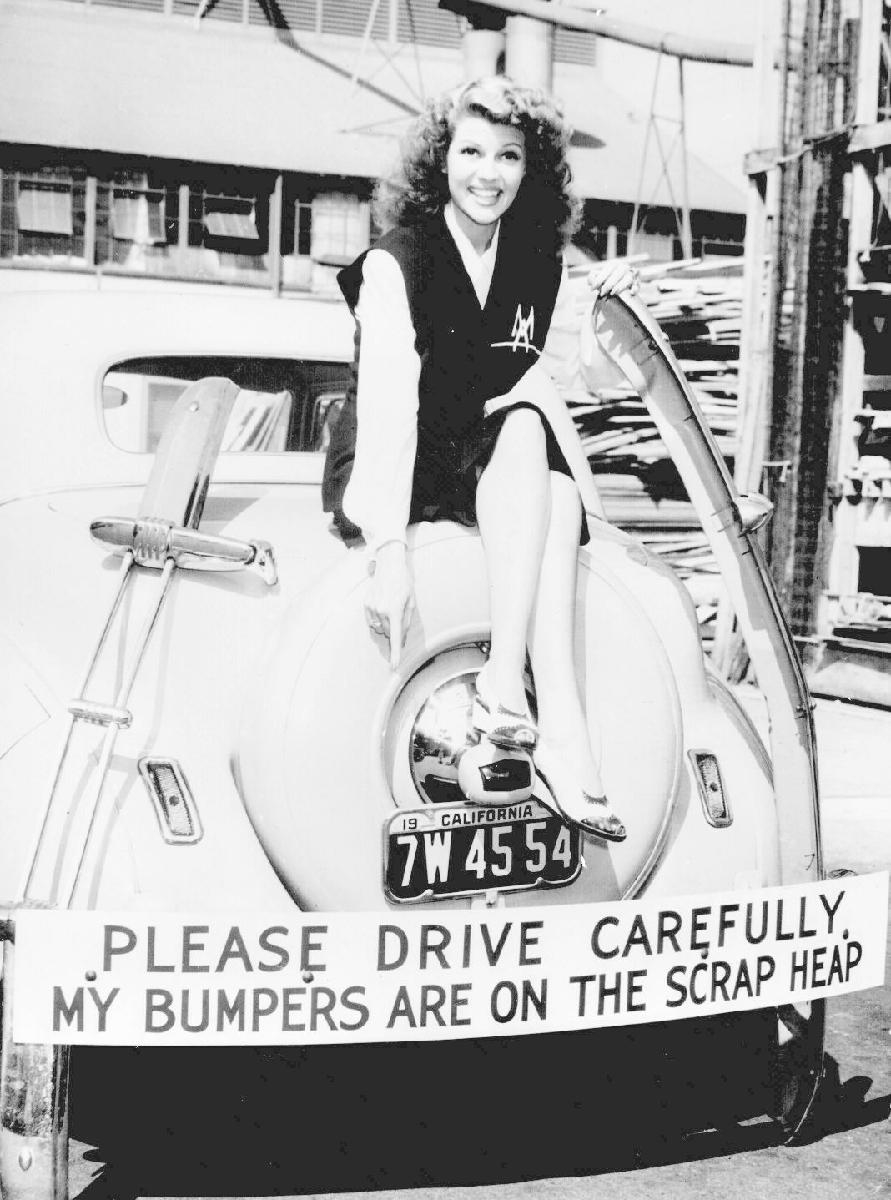

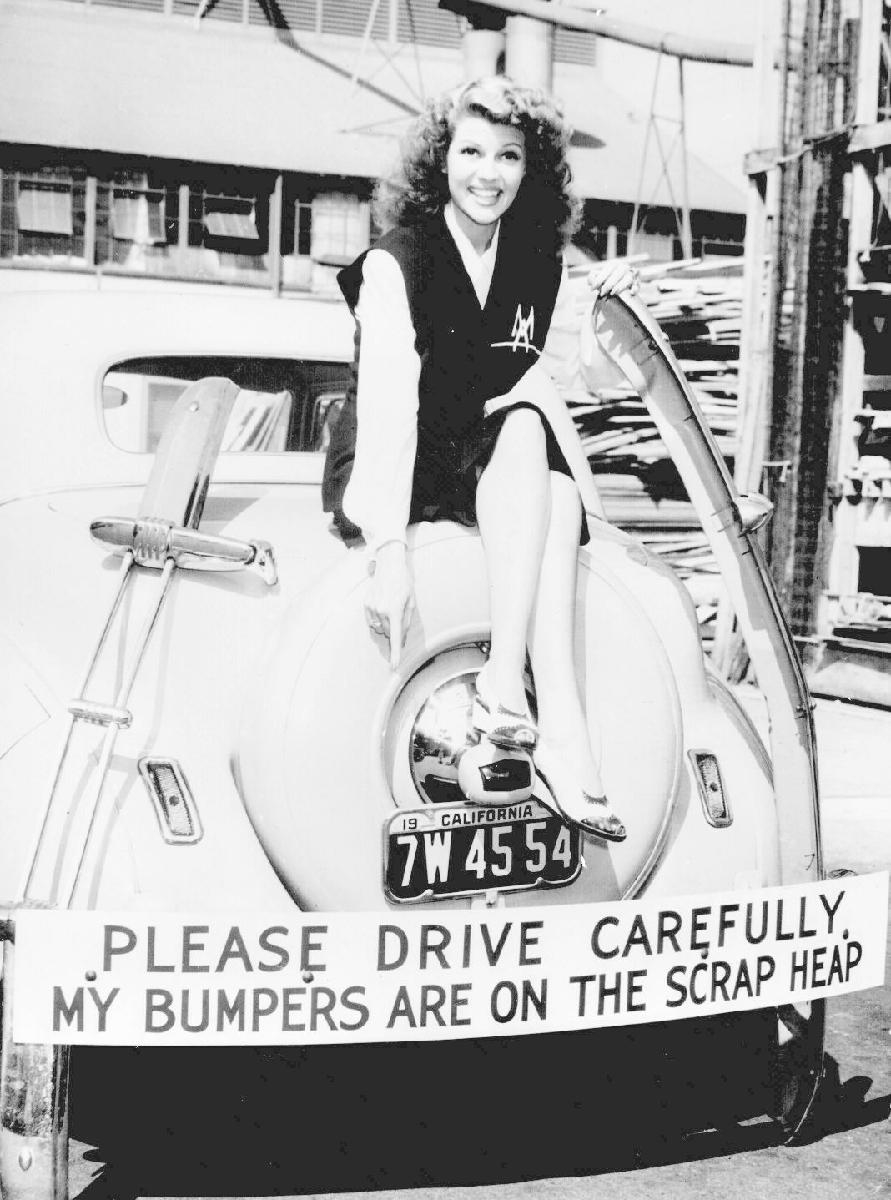

Movie star Rita Hayworth sacrificed

her bumpers for the duration. Besides setting an example by turning

in unessential metal car parts,

Miss Hayworth

has been active in selling

war bonds." 1942.

National Archives

208-PU-91B-5

A Victory Garden in downtown

New Orleans

Twins serving as Red Cross

volunteers folding bandages in West Lafayette, Indiana

Flattened tin cans being

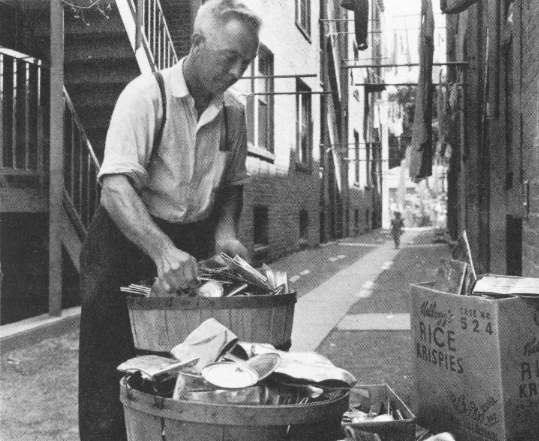

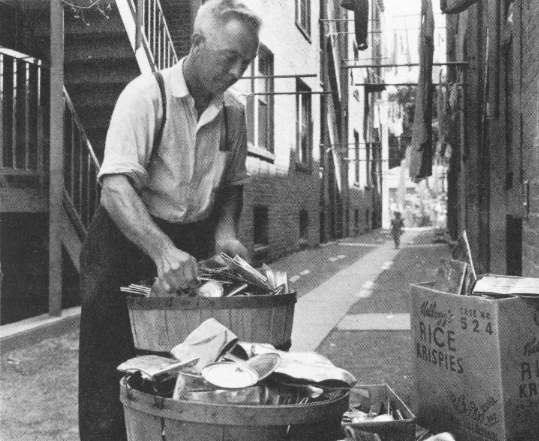

collected as recycled war materiel.

Flattened tin cans being

collected as recycled war materiel.

Library of Congress

Padlocks being collected

for their bronze and steel components

Padlocks being collected

for their bronze and steel components

A woman giving bacon grease

for use in making ammunition

A woman giving bacon grease

for use in making ammunition

Library of Congress

A woman passing on her nylon

stockings for use in powder bags

A woman passing on her nylon

stockings for use in powder bags

Library of Congress

Newspapers being collected

for use in making packing boxes

Library of Congress

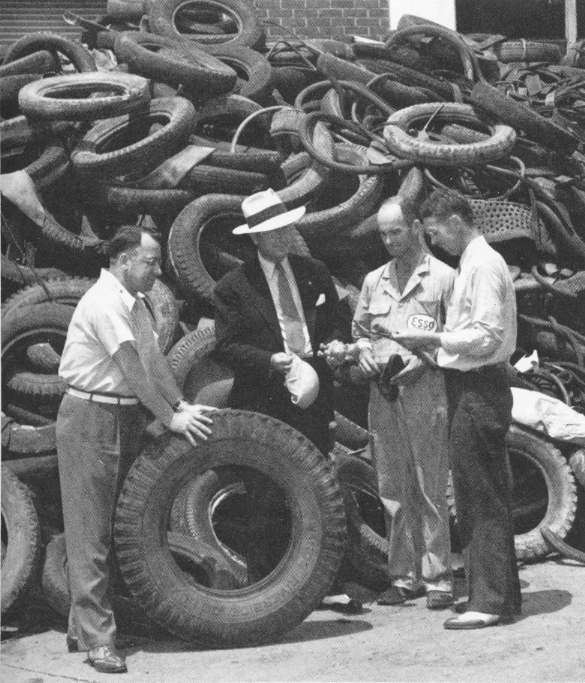

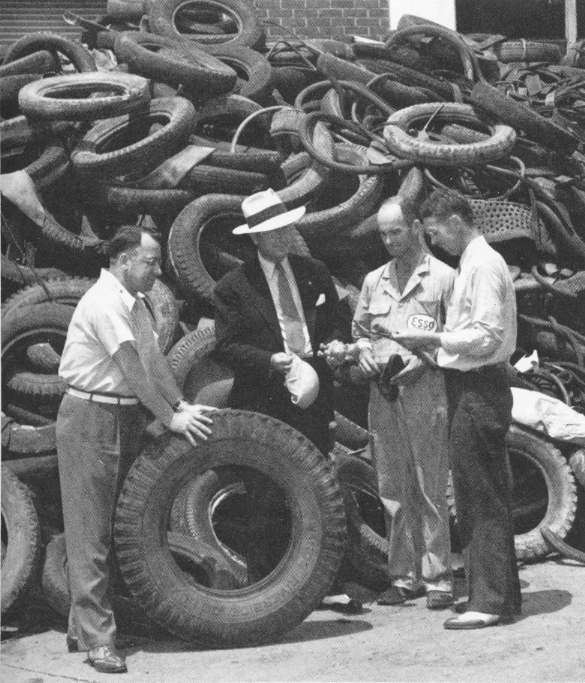

Worn-out tires being collected

as scrap rubber

Worn-out tires being collected

as scrap rubber

State Department of Archives

and History, Raleigh, N.C.

Toothpaste tubes being collected

for their metal content

Toothpaste tubes being collected

for their metal content

Library of Congress

A poster explaining the many

uses of common household scrap

A poster explaining the many

uses of common household scrap

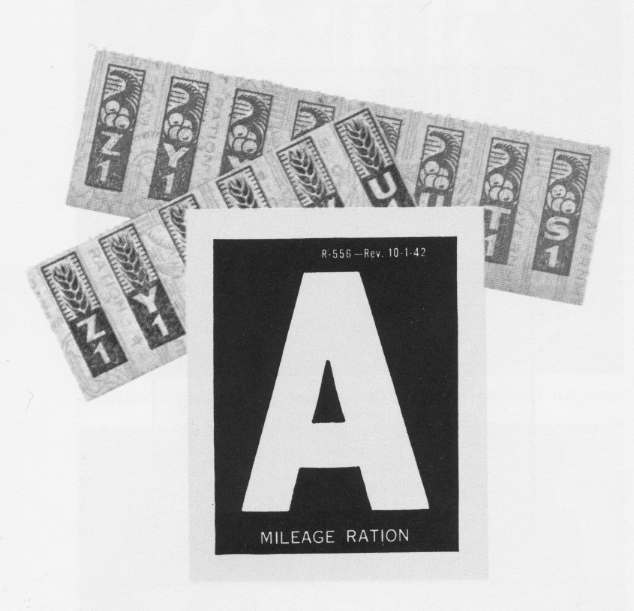

"Rationing" helped direct American wealth away from personal use ... to wartime use

The federal Ration Board

in Bristol, Connecticut

Ration stamps

Ration stamps

Sugar rationing.

National Archives

208-AA-322I-2

The point system for meat

rationing

Library of Congress

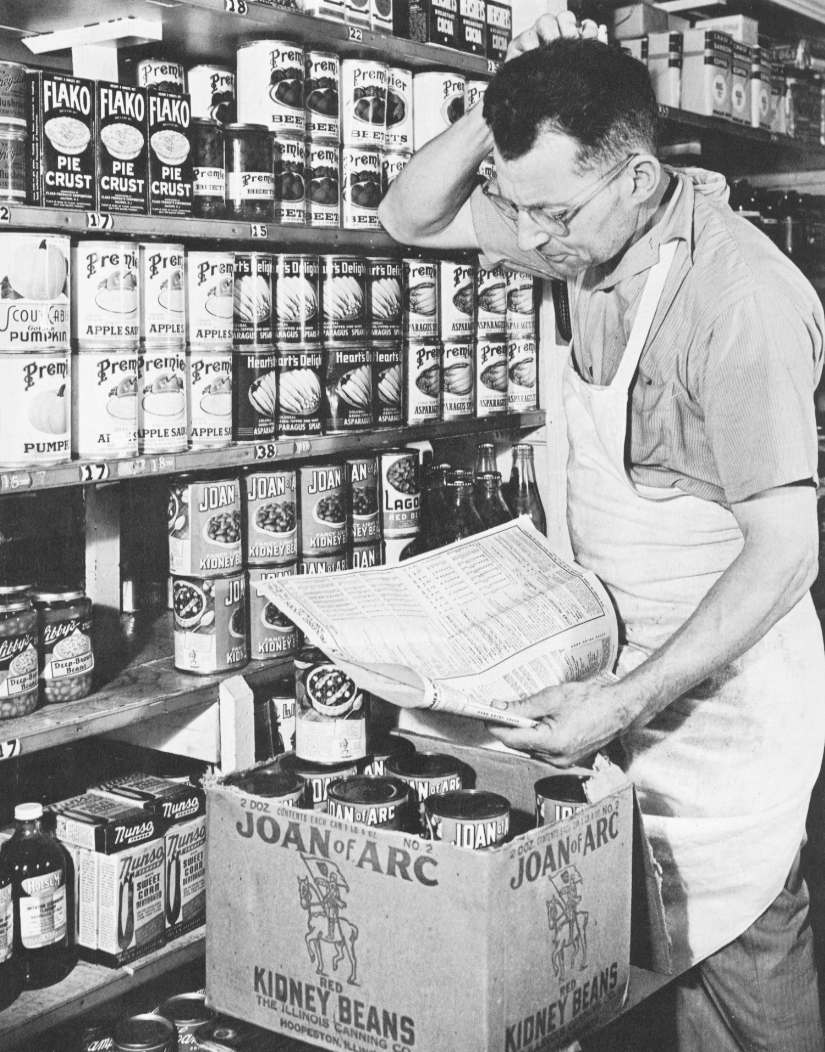

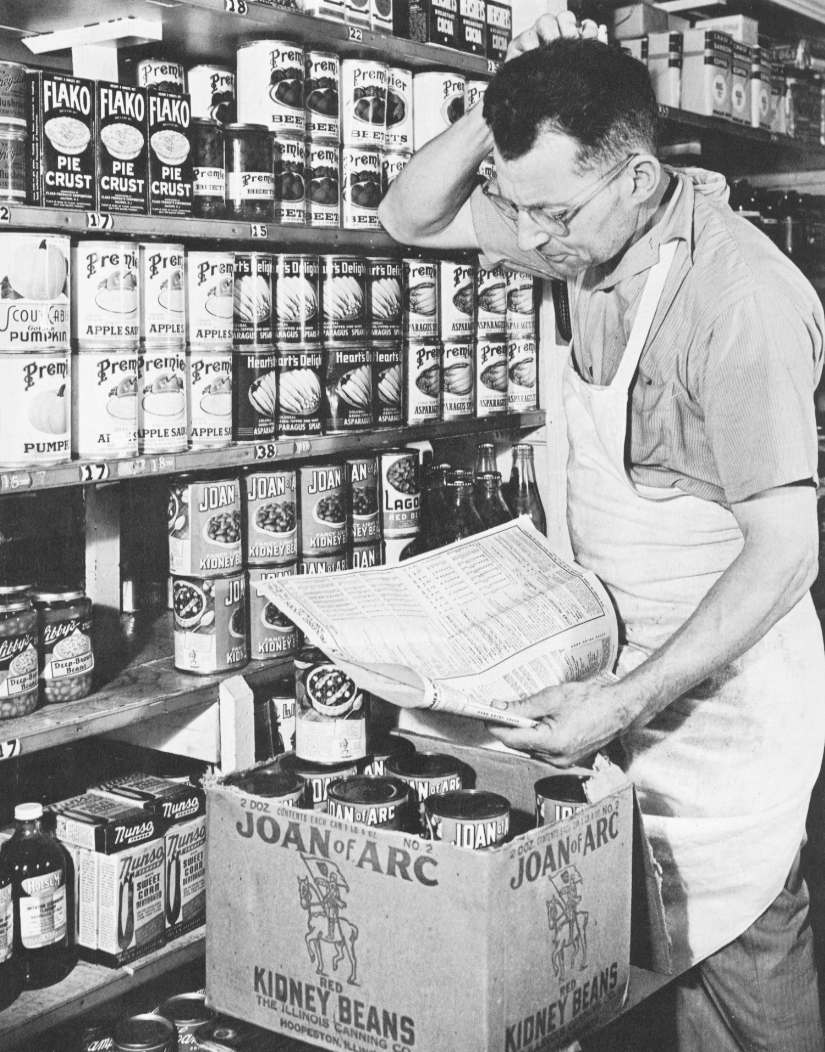

A grocer trying to figure

out the point system

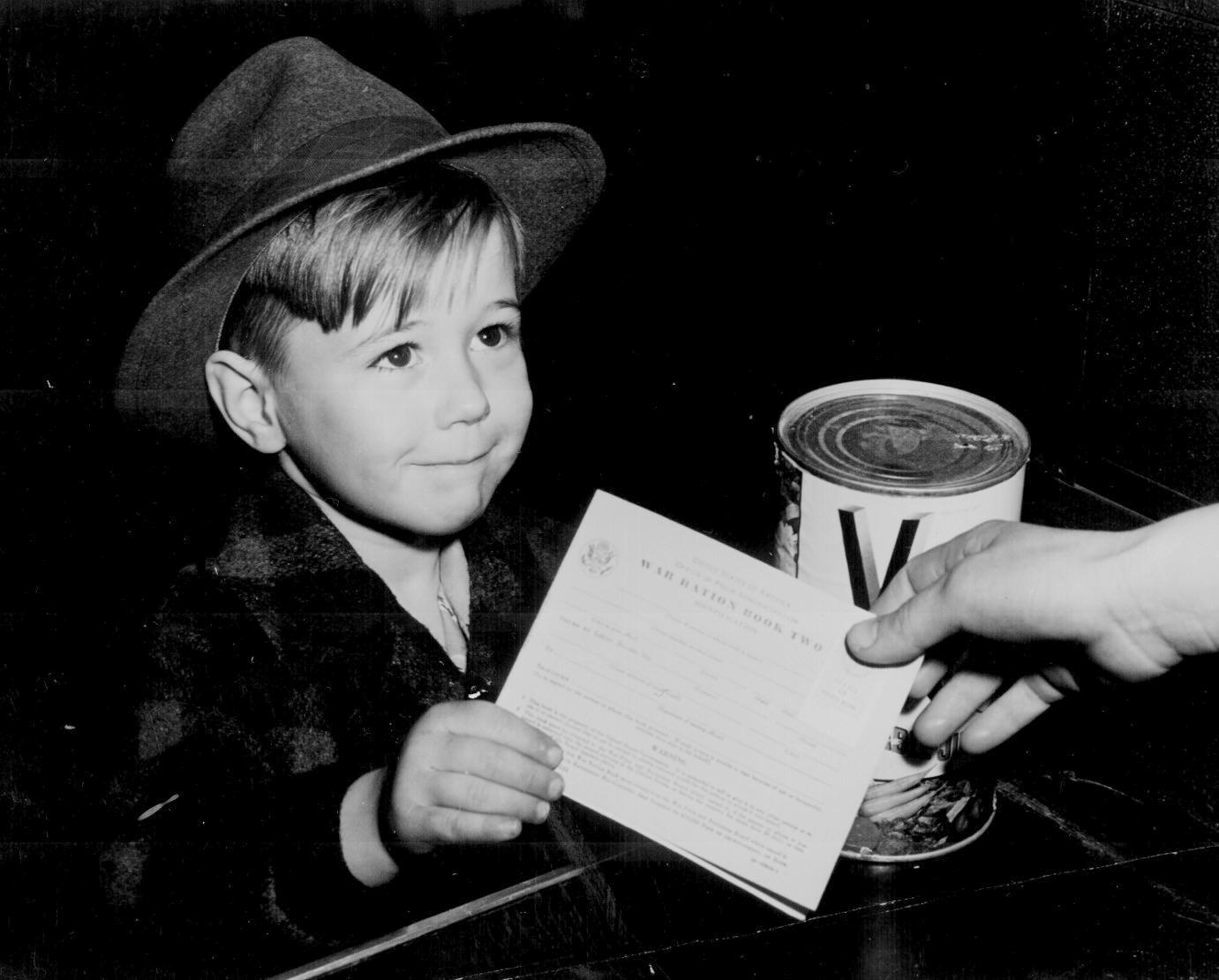

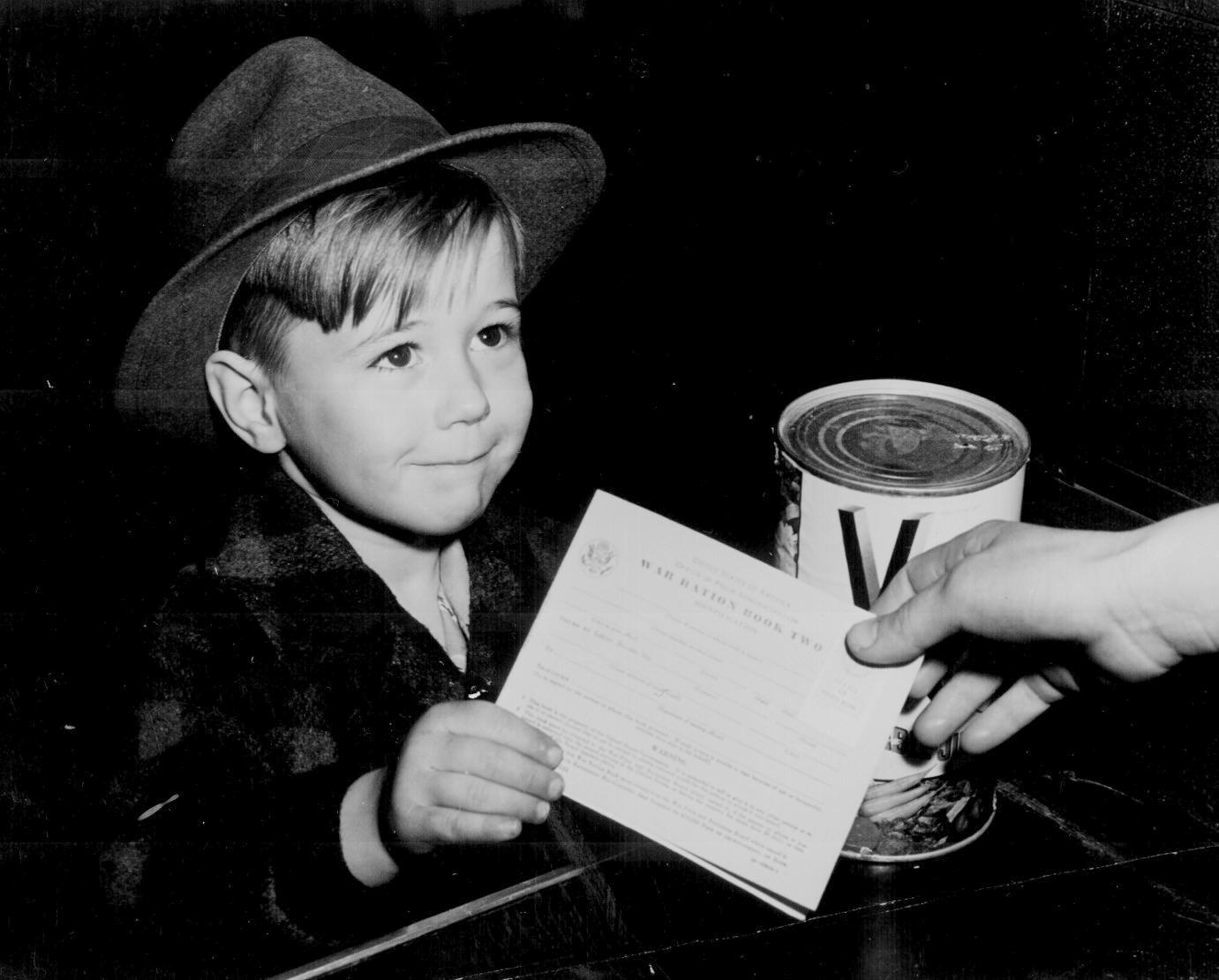

"An eager school boy gets his first

experience in using War Ration Book Two. With many parents engaged in war work,

children are being taught the facts of rationing for helping out

in family marketing." Alfred Palmer, February 1943

National Archives

208-AA-322H-1

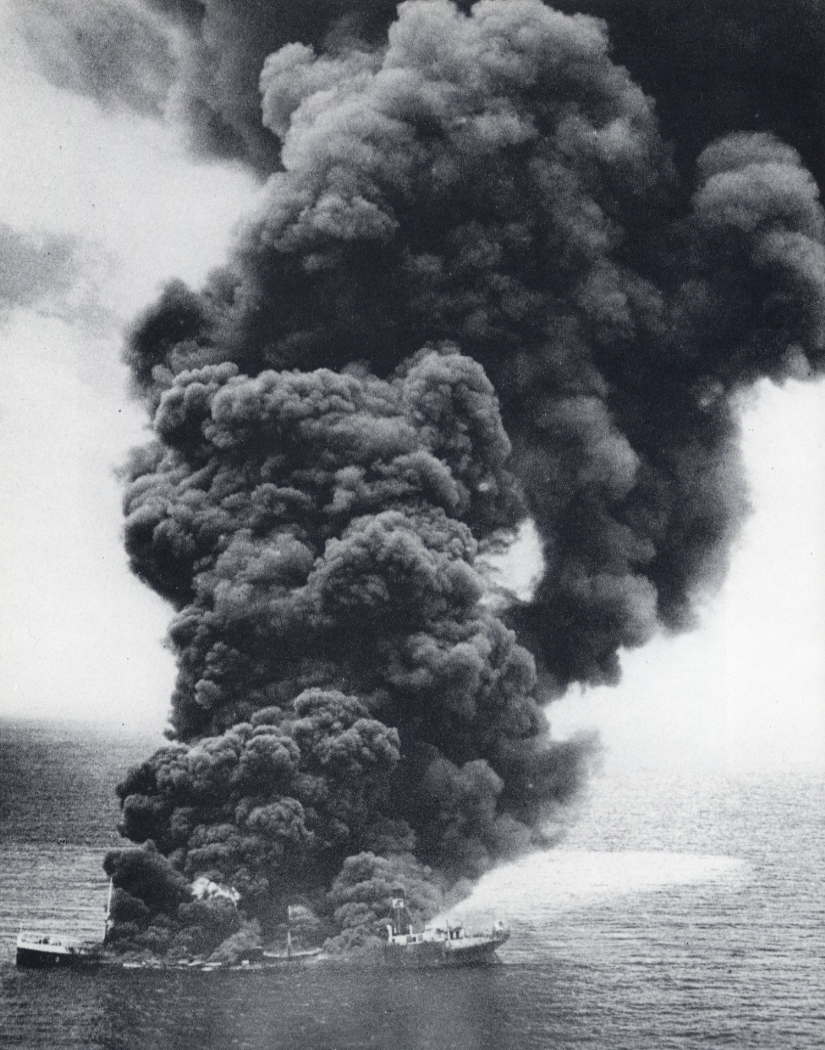

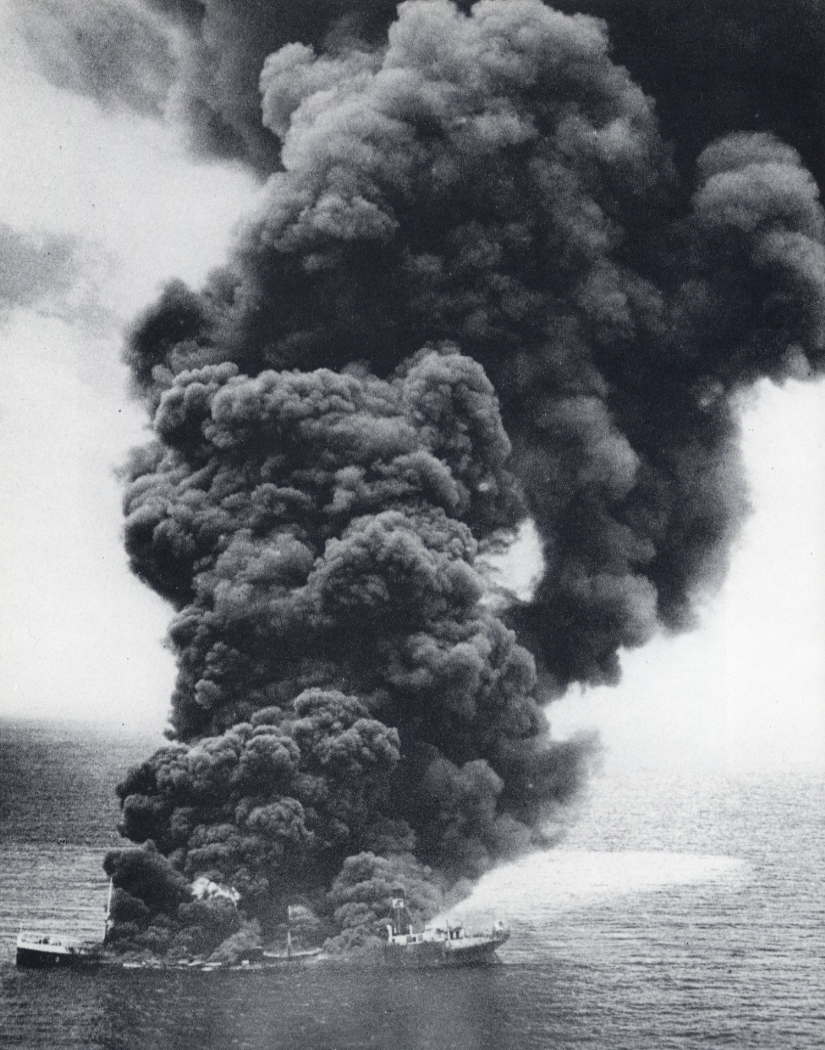

Occasionally the war comes all the way up to America's doorstep

A US tanker hit by a German

submarine off the Florida coast – 1943

United

States Army Air Force

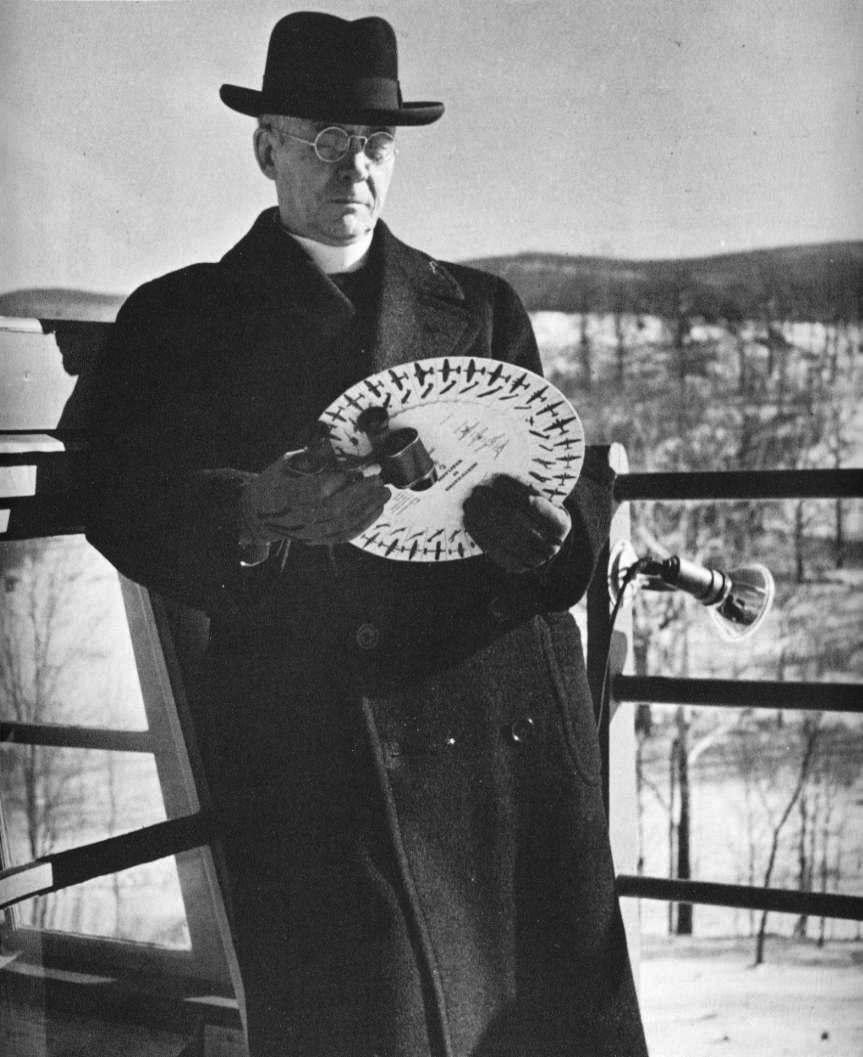

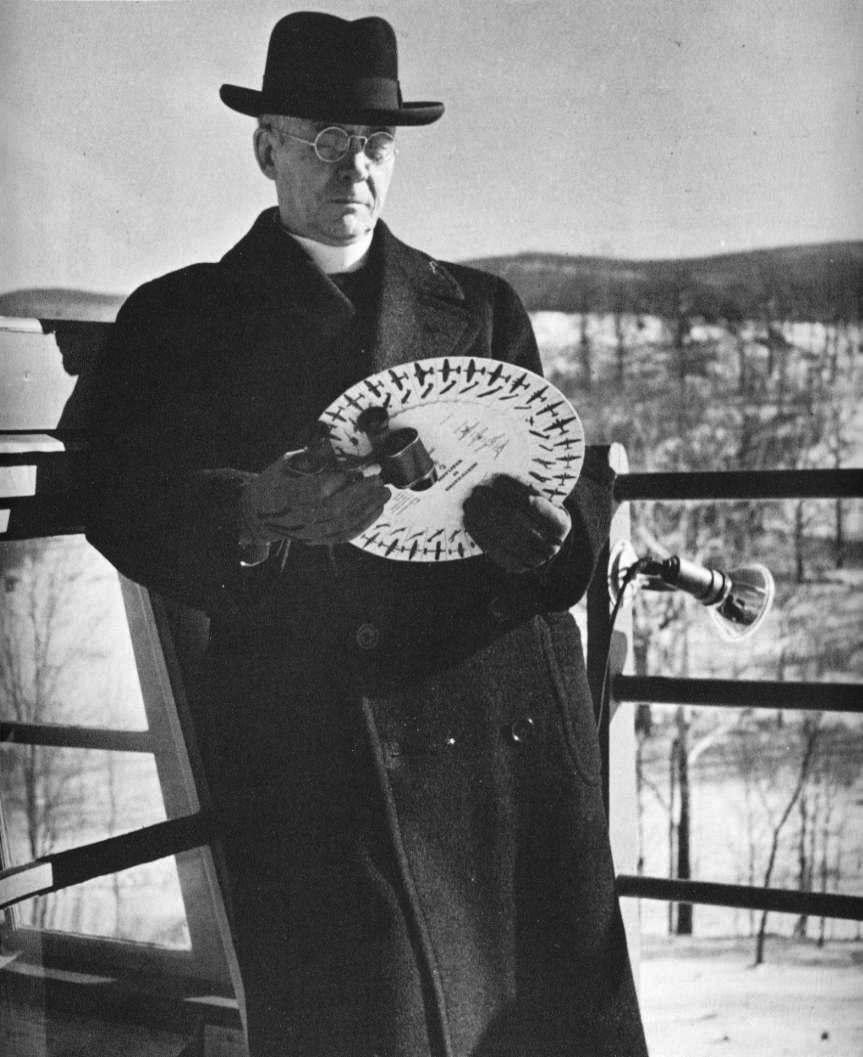

An air spotter at his post

in Kent, Connecticut

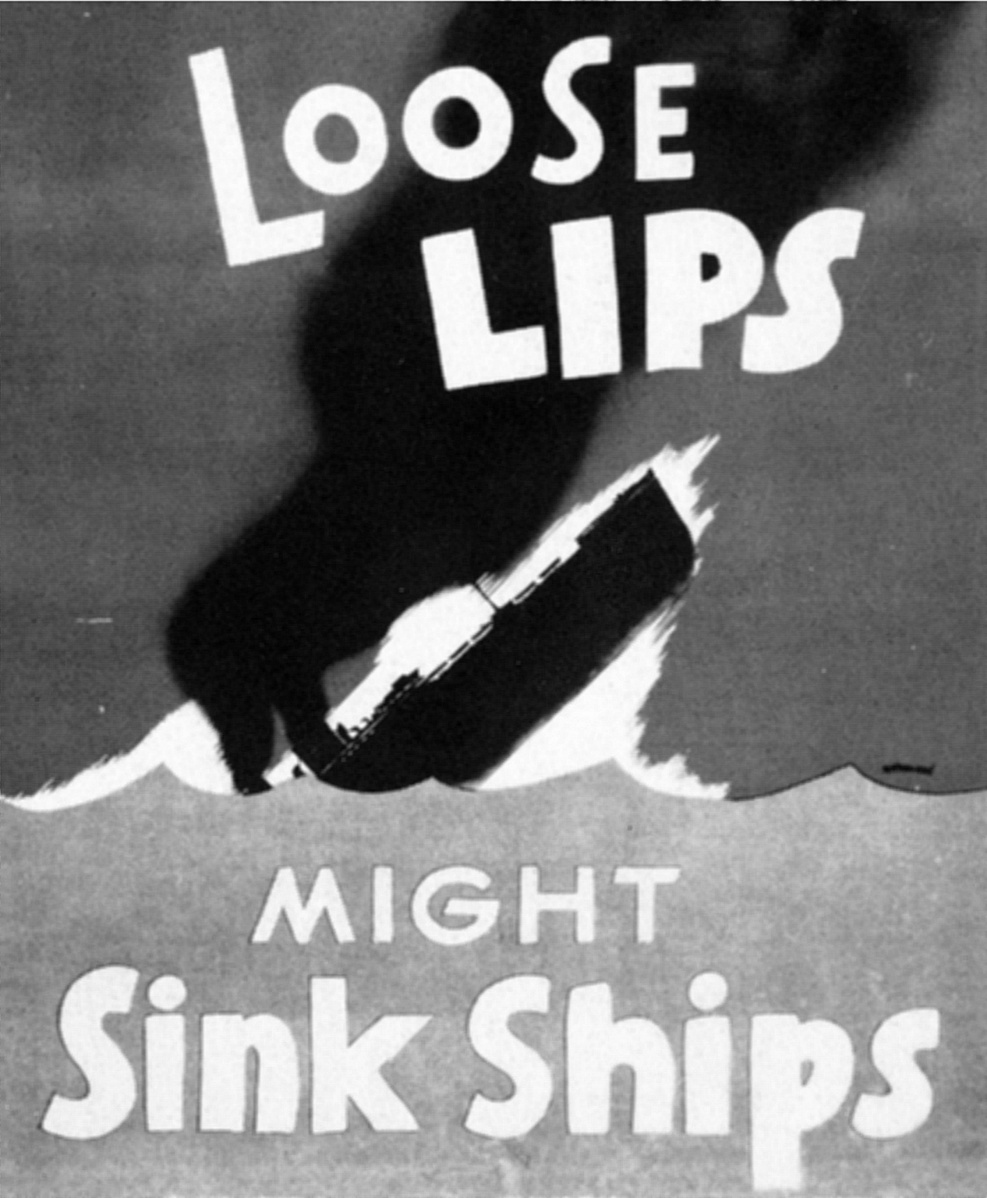

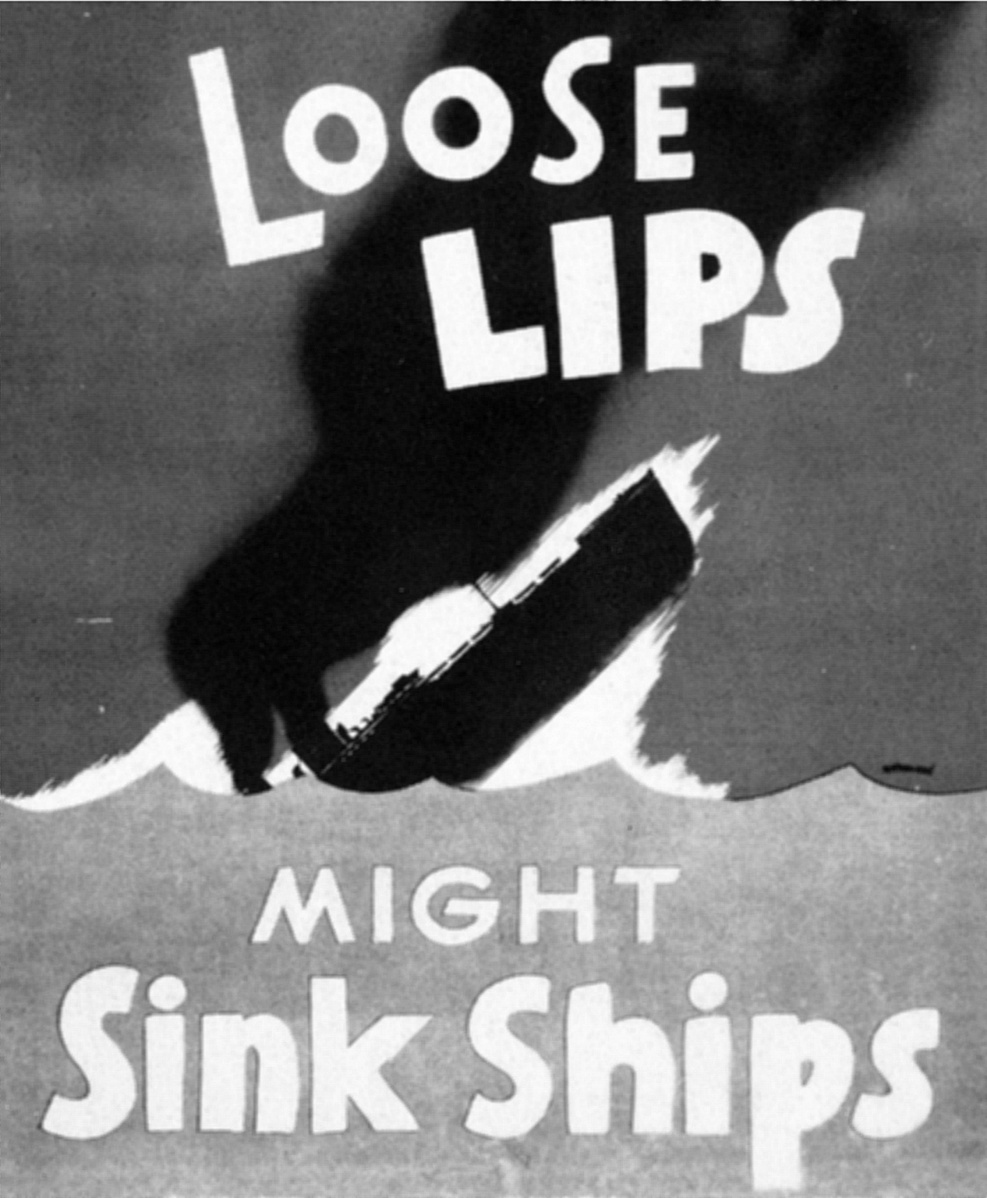

Loose Lips might sink

ships.

Loose Lips might sink

ships.

National Archives

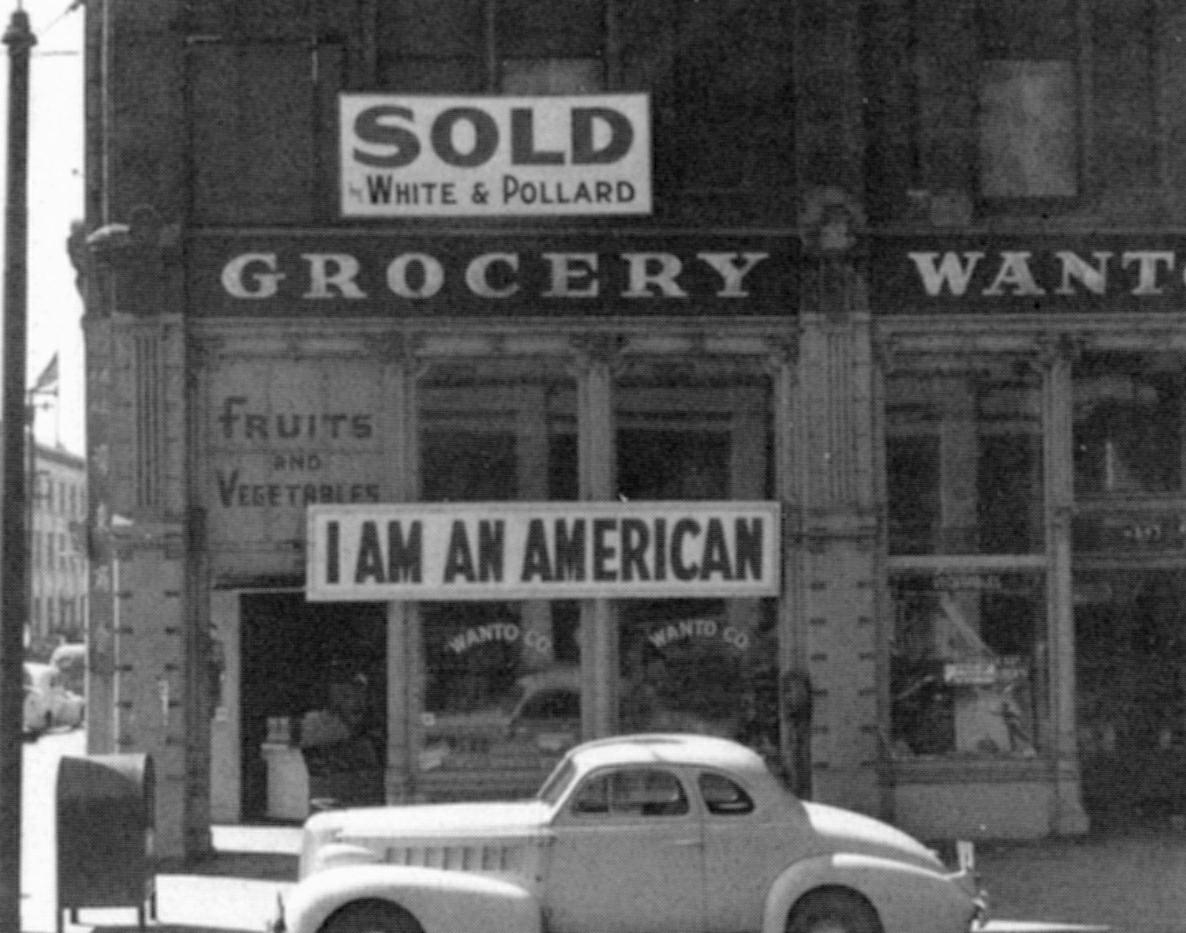

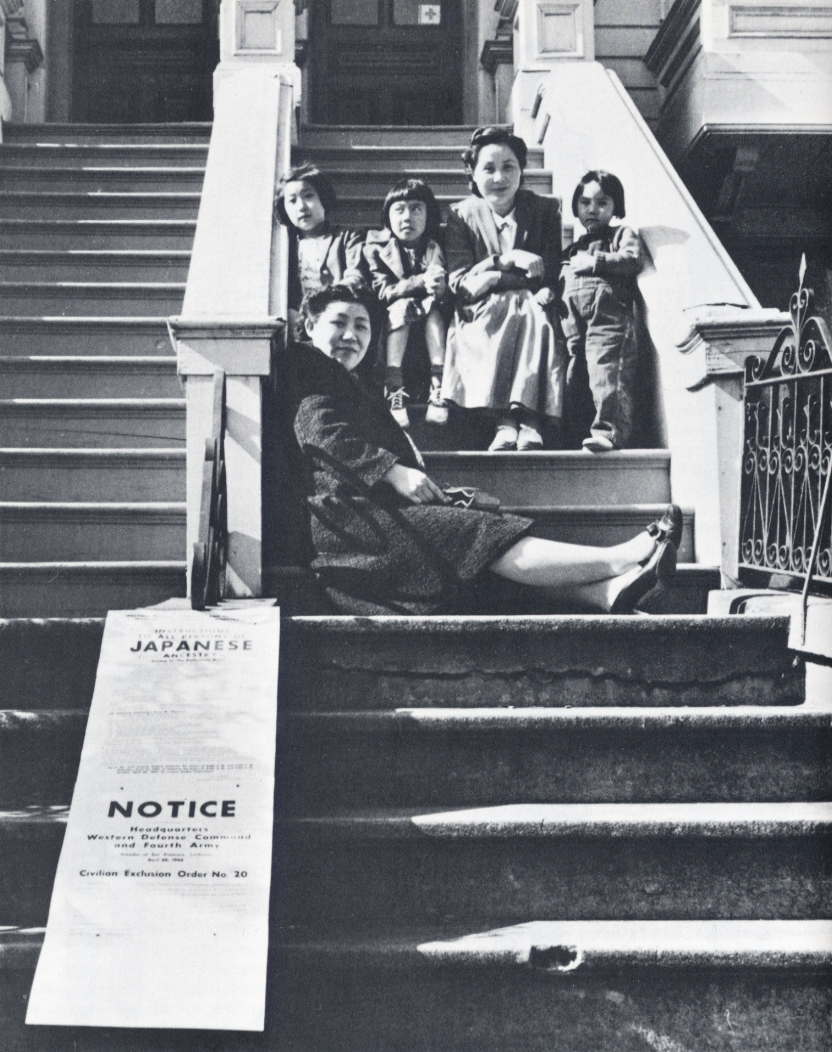

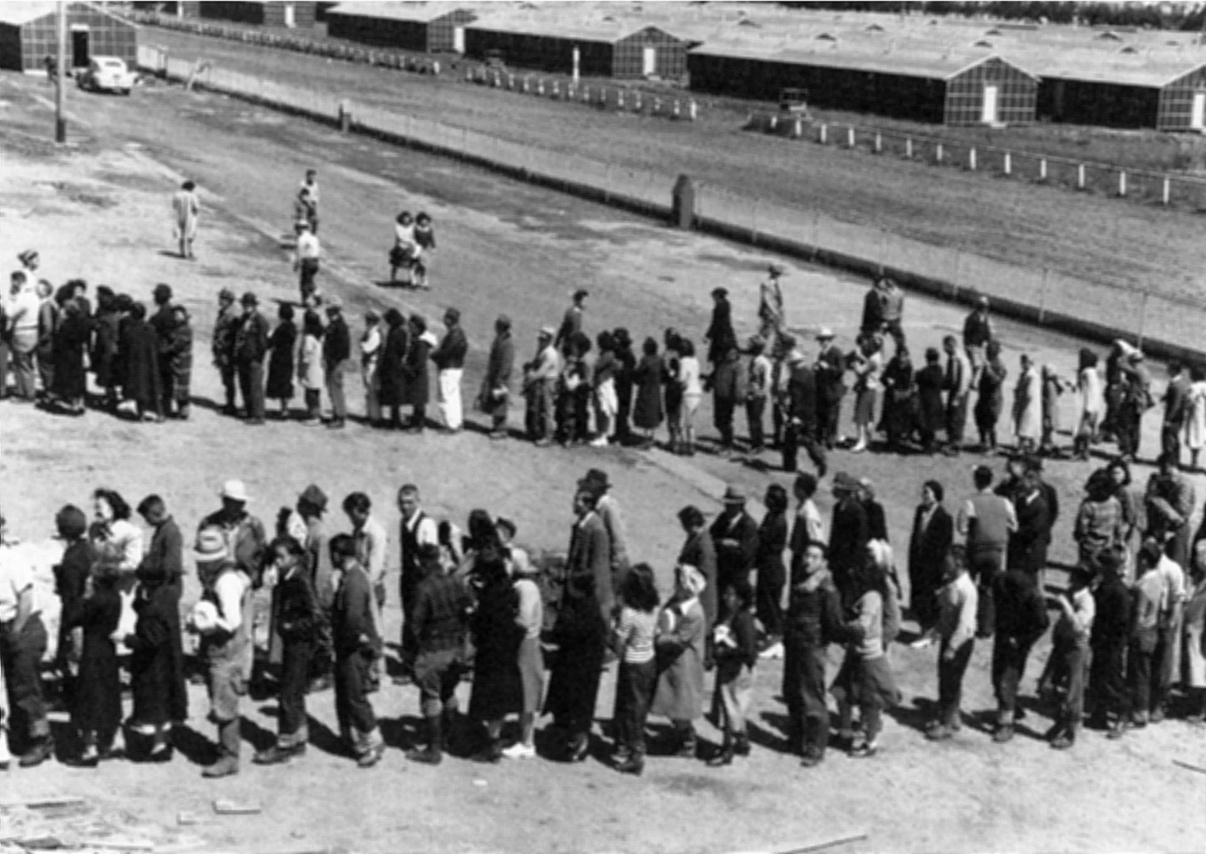

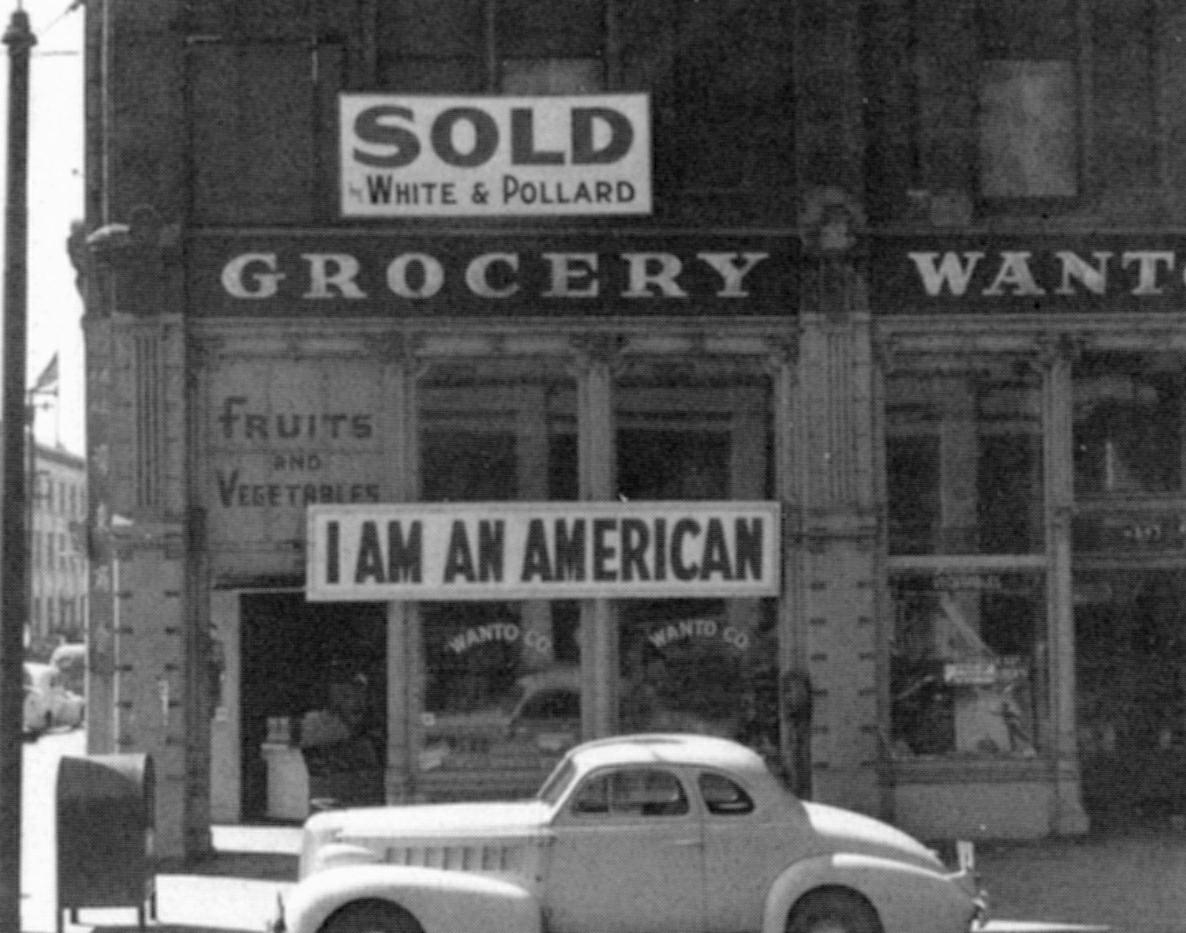

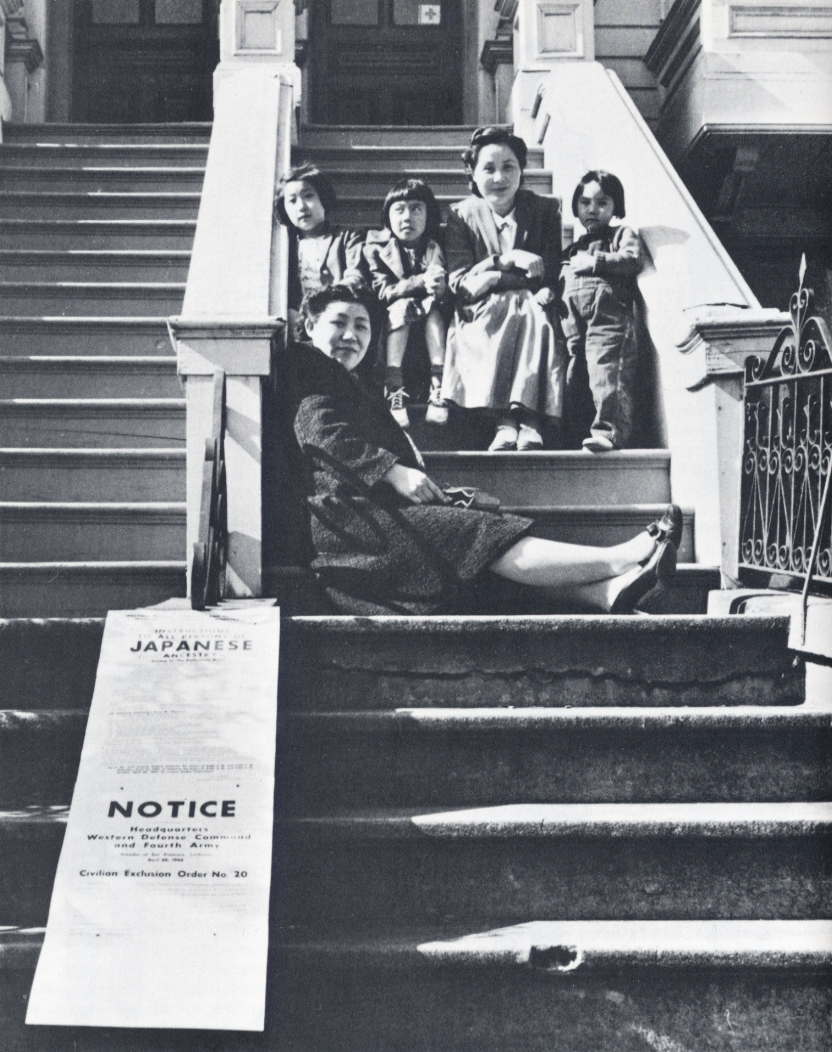

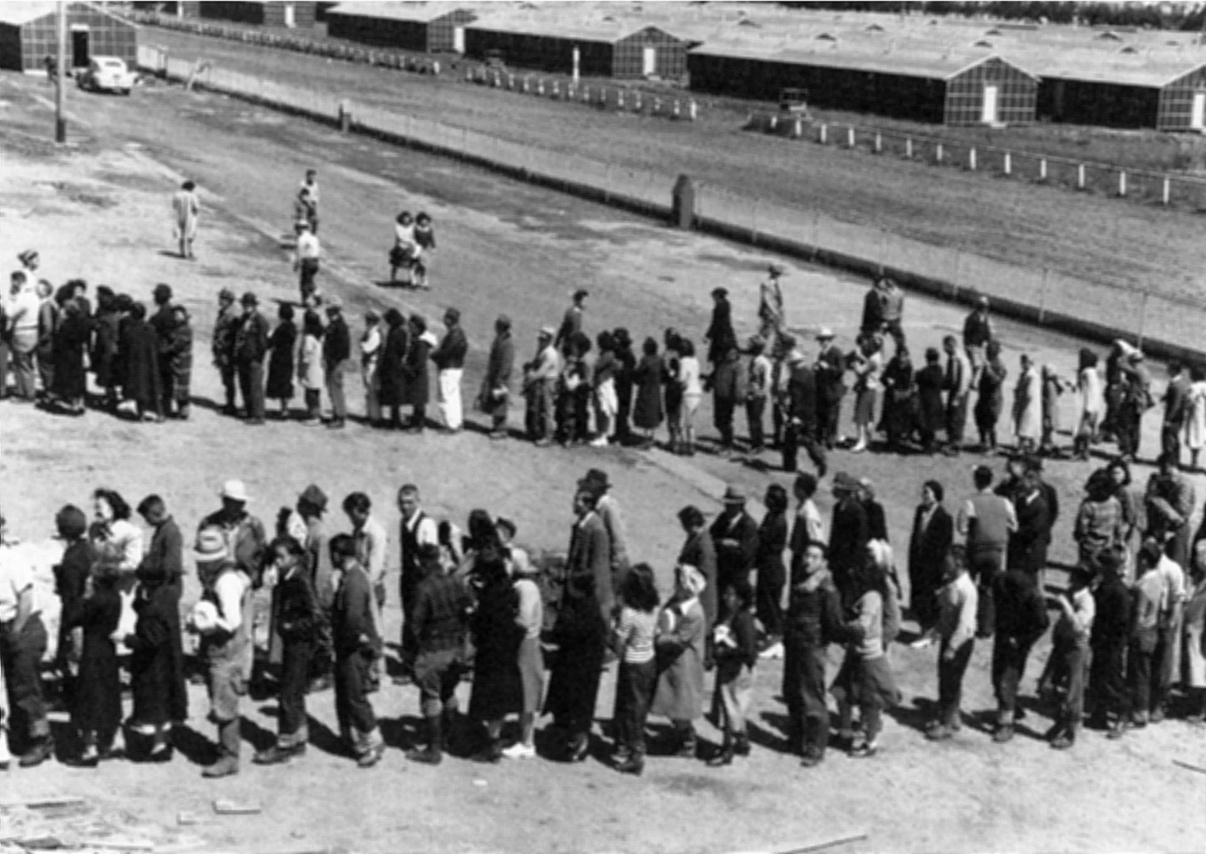

Japanese "internment"

One sad chapter in the story of America's wartime

government-society relationship was the 1942 Executive Order 9066

ordering 110,000 civilians of Japanese descent (included in that number

were 71,000 actual American citizens) living along America's West Coast

(principally California) to be sent to internment camps, huge camps of

bleak and depressing barracks-style housing – where these ethnically

Japanese families could be contained. The program was justified on the

basis that the Japanese had acted so treacherously in their attack on

Hawaii, that fear became widespread that Japanese-Americans might

secretly be part of a "Fifth Column" at home (the Fifth Column refers

to the large communities of German residents in neighboring countries

which worked closely with Hitler's Nazis by purposefully created chaos

in those lands so as to make the Nazi conquest of Germany's neighbors

all the easier).

The move is all the more shameful in the

targeting of Japanese-Americans, when German-Americans and

Italian-Americans were not only not interned, but served quite readily

in the US military in fighting Germany and Italy. Actually, some

Japanese-Americans would enter US military service. But in general, the

internment of the Japanese-Americans was widespread, causing these

American citizens to lose their homes and businesses permanently. But

the Japanese were amazingly graceful in the face of this huge betrayal

of American democratic (even Christian) norms.

"A crowd of onlookers on

the first day of evacuation from the Japanese quarter in San Francisco, who themselves

will be evacuated within three days." By Dorothea Lange, San Francisco,

California, April 1942

National Archives

Japanese-American store sold

- 1942

"Members of the Mochida family

awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags

were used to aid in keeping a

family unit intact during all phases of

evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five

greenhouses

on a two-acre site in Eden

Township." By Dorothea

Lange, Hayward,

California, May 8, 1942

"Members of the Mochida family

awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags

were used to aid in keeping a

family unit intact during all phases of

evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five

greenhouses

on a two-acre site in Eden

Township." By Dorothea

Lange, Hayward,

California, May 8, 1942

National Archives

A San Francisco Japanese-American

family awaiting relocation

Go on to the next section: The War in Asia and the Pacific

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | |

The Atlantic Charter (August 1941)

The Atlantic Charter (August 1941)

Growing Japanese-American tensions

Growing Japanese-American tensions

"A date that will live in infamy"

"A date that will live in infamy" America cranks up the industrial war

America cranks up the industrial war