19. A COLD WAR DEVELOPS

POST-WAR EUROPE

CONTENTS

Truman takes on early global challenges Truman takes on early global challenges

The mounting sense of a Soviet or The mounting sense of a Soviet or

Stalinist danger

Crisis in Greece and Turkey ... and the Crisis in Greece and Turkey ... and the

"Truman Doctrine"

Mounting problems in Western Europe ... Mounting problems in Western Europe ...

and the Marshall Plan

The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia

Helping Tito move out from under Helping Tito move out from under

Stalin's control

The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May

1949)

The ineffectiveness of the UN ... and the The ineffectiveness of the UN ... and the

Creation of NATO

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 56-69.

TRUMAN TAKES ON EARLY GLOBAL CHALLENGES |

|

As we have already noted, Truman was very much

like Churchill in his suspicions about unchecked power. Arriving

abruptly on the diplomatic scene after Roosevelt's death in early 1945,

with not a lot of prepping (while serving only briefly as vice

president, he had been privy to almost none of the military-diplomatic

proceedings going on within Roosevelt's Administration), he had at

first wanted to trust Stalin. But he soon realized that this was not

going to be possible, given the position in which the Russians found

themselves in Eastern Europe, with the Red Army in occupation of nearly

all of the Eastern half of Europe.

For Soviet Russia's Stalin, the matter of

what happened after Germany was defeated was quite simple: the Soviet

Red Army was in occupation of nearly all of Eastern Europe – offering

Stalin and his people a sense of security that they had never felt

since Russia began opening up to Western culture in the 1500s. There

was no way, despite the promises he had made to Roosevelt to hold free

elections throughout Eastern Europe, that Stalin (who personally was

massively paranoid anyway) was going to allow any but the most

Moscow-dependent – actually Stalin-dependent – regimes to be elected to

high office in those countries that his Red Army at that point

controlled directly. In one country after another Stalinist puppets

would soon appear at the head of each of the new governments of Eastern

Europe.

Truman could understand this Russian

desire to keep as much land buffer between itself and the European

West, which had been the source of endless attacks on Mother Russia,

from either the French, the Germans or even the Poles. But Truman

understood also that there was more than just a national security

concern moving Stalin. Stalin had bigger dreams, to bring all the

civilized world under a Godless International Communism directed from

Moscow. Thus Truman was quick to realize that the agreements at Yalta

were largely meaningless. Power – not promise – would be the rule of

the day in Europe.

But convincing the American people of the

dangers posed by an unchecked Soviet Union would be very difficult.

During the war the American propaganda machine had built up in the

American mind the closeness of America's special relationship with

Uncle Joe Stalin. To convince the Americans now to take a firm stand

against Stalin and his expansionist plans in Europe (given also the

American dream at this point of putting all thoughts of war completely

behind them) would be a Herculean task. Also, Americans were exhausted

and looked forward greatly to getting their boys back home and

returning things to normal in America as fast as possible.

Tensions had arisen at the end of the war

over the Soviet entrenchment in Iran. During the war the Americans had

been transporting military supplies to Russia across Iran, to the

distress of the Iranian Shah (king) who was a big Hitler supporter –

and who because of it subsequently got removed from power by an

occupying Russian and American military presence there. There was

however an agreement between the Americans and Russians that this would

be merely a temporary move and that full sovereignty would be restored

to Iran after the war. However, as the war appeared to be finally

coming to an end, the Soviets made a move to set up a

Communist-governed Azerbaijan Republic in the northwestern part of

Iran, an obvious move to leave a permanent Russian presence in the

area. Such a position would give the Soviets not only easy access to

the Persian Gulf and beyond that the Indian Ocean (such a warm-water

port had long been desired by the Russians) but it would also put

Soviet Russia in a position to dominate the major part of the oil flow

out of the Persian Gulf that industrial Western Europe depended on.

Truman was quick to see the dangers posed by this move on Stalin's

part. Truman consequently took the matter to the new United Nations

Security Council, putting such pressure on Stalin that the Russians

pulled out of Iran in early 1946 and Iranian troops moved in to retake

the territory.

But it would be the last time that the

Soviets would back down in the face of a Security Council decision

going against them. The Soviets would soon become well-known for their

ready use of the power reserved to the Big Five (the Permanent Members

America, Britain, France, Russia and China) to veto any Security

Council decision they disliked. From this point on, the hope that

people had that this new United Nations Organization might be a vital

support to world peace was now dead, as dead as a similar hope that had

died with the post-Great-War League of Nations. Big Power tempers were

rising fast – and subsequent crises would be dealt with in direct

diplomacy among these powers, rather than through the UN.

THE MOUNTING SENSE

OF A SOVIET OR STALINIST DANGER |

|

Churchill's warning about an Iron Curtain falling across Europe

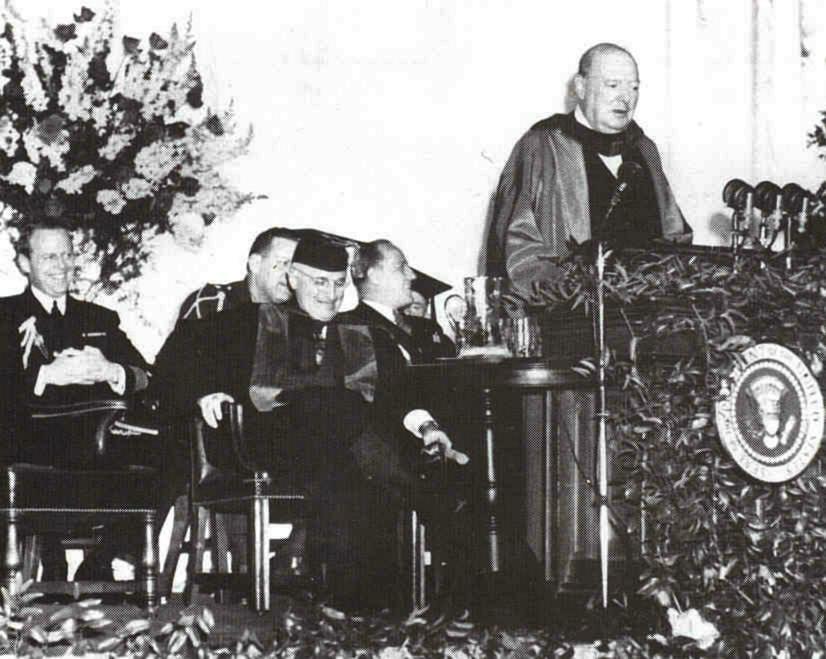

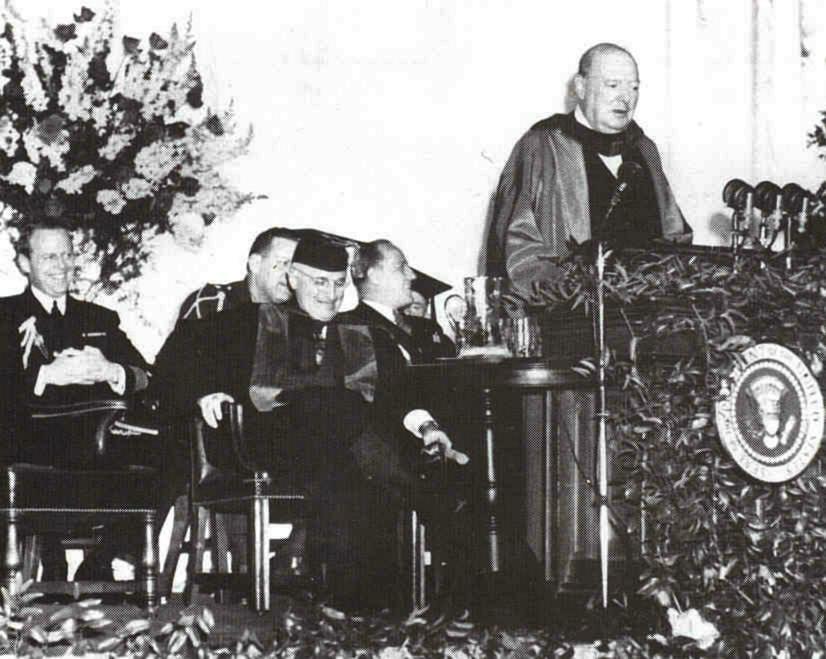

In March of 1946 Churchill (who at the time was largely

unemployed politically thanks to the British voters) accompanied Truman

to his native Missouri to receive an honorary degree from Westminster

College. Here he delivered a speech, acknowledging the global

responsibility that had now fallen on American shoulders.

What Churchill had to say on this matter

would actually come to shock America – though certainly not Truman!

Churchill pointed out that, thanks to Soviet control, an "Iron Curtain"

had fallen across the middle of Europe, stretching from the Baltic Sea

in the North to the Adriatic Sea in the South. And that behind that

curtain, in the Soviet sphere of influence, were the numerous cities

and peoples of Eastern Europe. In these societies, small Communist

parties had succeeded, thanks to Moscow’s increasing control, in

gaining such power as to be able to obtain totalitarian control over

these cities and peoples.

He also raised the issue of exactly how

this situation should be met – especially by the Americans, on whom so

much responsibility for the welfare of the civilized world had fallen,

reminding the Americans that the Russians admired strength and despised

weakness and, although they did not exactly want war, they were

certainly desiring the expansion of their power and the influence of

their doctrines.

As he had done with his own people during

the dark days of World War Two, he was calling now on America to take

up the challenge facing the world. For if the West (under American

leadership) did not act now in a show of strength, it would clearly be

dragged into war a third time in the 20th century. America and Britain

needed to stand together to block Stalin’s aggressions.

At the time, Churchill’s speech was received very negatively, not only

by Stalin (of course!) but also by the American news media. Churchill

was accused by numerous Americans of trying to stir up trouble between

Russia and America, of grandstanding in order to bring himself back to

political prominence (the same accusation made about him during the

1930s when he was trying to warn Britain of the dangers of Hitler’s

rise to power in Germany).

But America would soon come to

acknowledge the danger Churchill had been describing, using his term

"Iron Curtain" as a key part of the vocabulary describing a rising

East-West "Cold War."

For the time being, Truman had to go slow

in getting America back in the business of global affairs. He

personally was viewed widely by Americans simply as an accidental

occupant of the White House, possessing no serious presidential stature

before the American people. But he, with Churchill, understood that if

America did not step up to the responsibilities laid at its feet

because of the way the recent war turned out, the world would soon

enough be facing a problem as big as the one Germany and Japan had just

posed. He needed to stir America to action – though very carefully.

Actually whereas the US State Department

was still caught up in its dream of friendship with the Soviets, one of

their members posted in Kiev, George F. Kennan, answered a request by

the US Treasury Department to explain why the Soviets were not planning

to work with the new World Bank (IBRD) and the International Monetary

Fund (IMF). In his Long Telegram

(February 1946) Kennan described in detail the Soviet anti-capitalist

(and Russian nationalist) mindset, and called for the "firm and

vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies."

The report soon became the basis for a

larger analytical study of Soviet Russian goals and strategies

(September 1946), intended for the president's eyes only. But the

Kennan report itself was so clear in its analysis and call for a

strategic response that it was published in the July 1947 edition of Foreign Affairs

under the authorship of "X." It had the effect not only of helping to

awaken America to the need for vigilance against Soviet aggression but

it also gave the resultant US policy its identifying label:

"Containment" (of Communism).

|

Things begin to stir with

Churchill's "Iron Curtain Speech" delivered to Americans in 1946

President Truman and former

British PM Churchill arriving in Fulton, Missouri – March 5, 1946

Winston Churchill delivering

his "Iron Curtain Speech" at Westminster College,

Winston Churchill delivering

his "Iron Curtain Speech" at Westminster College,

Fulton, Mo. – March 5,

1946

| "From Stettin in the

Baltic to Trieste

in the Adriatic an "iron curtain" has descended across the Continent. Behind

that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern

Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and

Sofia; all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what

I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject, in one form or another,

not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and in some cases increasing

measure of control from Moscow." |

American diplomacy at the

time was well served by a number of very capable

and highly experienced "Wise Men"

Former General, now US Secretary

of State George Marshall

Former General, now US Secretary

of State George Marshall

Also part of the Truman "Wise

Men"

Paul Nitze

Robert Lovett

John McCloy

Averell Harriman

US diplomat George Kennan

who in his "Long Telegram" of 1946

US diplomat George Kennan

who in his "Long Telegram" of 1946

advocated "containment" of an expansive

Soviet Communism

This document,

originally

intended as a briefing paper for Secretary of the Navy Forrestal, was published

in the July

1947 edition of Foreign Affairs under the authorship of "X"

-

which was quickly traced

back to Kennan. But the article clarified the fact that indeed America

was headed for a 'Cold War' with Russia. |

CRISIS IN GREECE AND TURKEY

... AND THE TRUMAN DOCTRINE |

|

Crisis and Greece and Turkey

A major problem was brewing at the eastern end of

the Mediterranean, at Greece and Turkey. Failure to secure a path

to the high seas across Iran brought Stalin to redirect his focus on

gaining control of the Aegean Sea, bordered by Greece on the West and

Turkey on the East. Such control would give his navy based in the Black

Sea free access to the Eastern Mediterranean, and also a dominant

position just above the Suez Canal, through which nearly all the trade

between Asia and Europe passed. But the difference here was that the

Russian troops (as elsewhere in Eastern Europe) were not in direct

occupation of either Greece or Turkey. Stalin instead would have to

work through local Communist organizations, which received direct

orders from Stalin but did not enjoy the backing of Stalin's Red Army

in implementing those orders.

Over the previous century (since the

mid-1800s) the Turks had looked to the British for help in warding off

Russian expansionist instincts. But by 1947 the British had backed off

both militarily and financially in their assistance to the Turks.

Churchill, still out of power, was hoping that America would now take

up that role.

The Greek situation was a bit different.

In Greece it was more the case of the Yugoslavian rather than the

Russian Communists that were the immediate source of Greece's problems.

Yugoslavia, under the presidency of the Communist leader, Marshal

Josip Broz Tito, was sending financial and military aid next door (to

the south of Yugoslavia) to the Greek Communist Party, which was trying

to overthrow the Greek government elected in 1946. Here too the British

had traditionally been the guarantor of Greek political stability. But

by early 1947 Atlee's British Government was abandoning the traditional

British role in Greece as well as Turkey – and everywhere else, for

that matter. Again, Churchill urged Truman to take up Britain's

traditional role of stabilizing the entire region (uncomfortably close

to Britain's vital link to Asia through the Suez Canal). Truman

understood clearly the dynamics of the situation.

Consequently, in March of 1947 Truman

went before Congress to request financial and technical military

assistance to the Turks and Greeks. He specified only a general threat

to the independence of these countries by both outside powers and

domestic insurrectionists that wanted to force free peoples to come

under totalitarian governance (neither the Soviets nor Yugoslavs were

mentioned by name). Truman stated that at this point only America had

the power to help struggling nations achieve democratic stability and

that America needed to act swiftly to make sure that no free people

should ever fall under the power of totalitarian tyranny.

The Republican-controlled Congress finally in May agreed to fund his

financial assistance program to both Greece and Turkey ($400 million),

but held back on the sending of military assistance, for the time being

anyway.

In any case the effort proved a success. Greece was able to head off

the Communist uprising and Turkey felt encouraged enough by American

backing that it refused to bend to Soviet pressures.

|

The Truman Doctrine – President

Truman addressing Congress – March 12, 1947

The Truman Doctrine – President

Truman addressing Congress – March 12, 1947

Harry S. Truman Library

and Museum

Greek women mourning the

loss of their men and boys murdered by Communist guerrillas who came through their Macedonian

town – many killed because they had been seen talking to American military advisers

who had just come through the town – 1947

Greek women mourning the

loss of their men and boys murdered by Communist guerrillas who came through their Macedonian

town – many killed because they had been seen talking to American military advisers

who had just come through the town – 1947

A Greek National Army patrol

sweeping toward the Albanian frontier in search of Communist guerrillas – early 1948

A Greek National Army patrol

sweeping toward the Albanian frontier in search of Communist guerrillas – early 1948

Greek Commanders and Lt.

General James A. Van Fleet, chief US military representative in Greece, standing over dead guerrillas

near the Yugoslav border – May 1949

MOUNTING PROBLEMS IN WESTERN EUROPE

... AND THE MARSHALL PLAN |

|

The effort to return Western Europe to normal life

Meanwhile, post-war Western Europe (Britain, the

Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, etc.) at first looked as if it

were actually going to rebound fairly quickly in its social and

economic life now that peace was at hand. There was much work to be

done, requiring the labor of soldiers returning to peacetime life, thus

preventing the danger of massive unemployment overwhelming their

post-war recovery.

But what permitted this post-war economic

rebound was the remainder of the financial credits held by the various

Western governments, which by the end of 1946 or early 1947 were

running out. Much of this government funding had ended up in America,

to purchase from America basic capital goods needed to restore the

destroyed infrastructure in housing, commercial and industrial

buildings, rail lines and docks. Local currencies were traded for the

dollars needed for these purchases. But by the winter of 1946-1947

Western European governmental financial reserves were drained dry. A

huge dollar deficit developed, bringing the post-war economic revival

in Europe to a halt.

Troubles in Western Europe

Workers were now being let go as businesses were

forced to shut down, causing workers to take to the streets in protest,

and driving many of them into the political arms of the fast-growing

Communist Parties (in France and Italy especially).

These were the kind of conditions that

could produce some very dangerous political mischief, as the politics

of the Great Depression had clearly demonstrated. In fact, the

Communist Parties in a number of Western countries were quite large,

constituting a third of the electorate in France and Italy, for

instance. Part of this was the by-product of the Great Depression, part

the friendly relations with Soviet Russia during the War, part of it

Stalin's strong direction of Europe's Communist movements throughout

Europe. After the war, under Stalin's direction, the French Communist

Party under Thorez and the Italian Communist Party under Togliatti

participated in the Leftist alliances with Socialist and Christian

Parties. The right-wing parties, identified in France with the

collaboration with the Nazis that took place during the Vichy regime

and in Italy with Mussolini's Fascist regime, were largely discredited

and were left out of all political affairs.

At this point it appeared that these

countries with large Communist organizations might be headed toward

Social Democracy (Marxism).

But by 1947 West Europeans were coming to

an understanding of Stalin's intentions to bring all of Europe under

Soviet mastery through his control of the large Communist movement in

the West, through workers' strikes which – though initially supposedly

addressing the problems of rapidly rising inflation and massive

unemployment – soon gave the appearance of being designed mostly to

paralyze the struggling economies of Western Europe. When in France

(May 1947) the Communists were then excluded from the coalition

government governing the country, the workers' rebellion grew even more

radical. Meanwhile the street violence in Italy was growing.

At this point Truman began to send aid

secretly to the anti-Communist labor unions and political party

organizations both in France and Italy.

Stalin responded to this challenge coming

from America with the resurrection of the old Comintern – the Communist

International organization which had been dissolved during World War

Two as a sign of Soviet good will toward Russia's Western allies –

making its new appearance in October of 1947 as the Cominform

(Communist Information Bureau), an alliance of Communist Parties around

Europe, all under Stalin's direction. Cominform membership included

also the huge French and Italian Communist Parties. Stalin clearly

intended to take a stronger hand in reshaping post-war Europe, West as

well as East. |

| In

Western Europe there is also a decided political shift to the Left

following the war. Worse, Leftist parties (principally the French

and Italian Communist Parties) seem to be taking orders from

Stalin directly. In France, the Communists

under Maurice Thorez are demonstrating significant political gains |

French Communist leader Maurice

Thorez (right), Vice Premier in post-war France – Dec. 1946

French Communist leader Maurice

Thorez (right), Vice Premier in post-war France – Dec. 1946

The same movement to the

Left is strongly registered in Italy

Italy's postwar political

coalition – and rivals: Christian Democrat Alcide de Gasperi (rear

left), Socialists Pietro Nenni

(third from left) and Communist Palmiro Togliatti (right) – Rome, December

1945

The long winter of discontent:

1946-1947. Citizens of Krefeld Germany protesting, in demand for food and fuel

(March 1947) The long winter of discontent:

1946-1947. Citizens of Krefeld Germany protesting, in demand for food and fuel

(March 1947)

Bundesarchiv

183-B0527-0001-753

In the Eastern European countries under direct Soviet military occupation, there

is no question about whether their future is "Communist" or not.

Tragically, Truman must simply leave those living under Soviet

occupation to their sad fate.

|

A Polish soldier oversees

Polish elections – January 1947

|

But Truman was as determined that Stalin

should not be able to do that. Truman was keenly aware of the immense

financial crisis Europe was facing – with all of its dangerous

political implications as it found itself running out of the funding

needed to get healthy economies back up and running again. Truman thus

worked out a plan to help Europe with its dollar shortage, by simply

extending huge dollar grants to the European countries to help get them

back on their feet. These were not loans. They were outright financial

gifts, ones that would be given freely as the European countries

submitted to America well-designed proposals for reconstruction. If

these programs seemed doable, then America would provide the financing

for the programs.

Thus it was that Truman's secretary of

state (former general), George Marshall, announced this plan at a

Harvard commencement speech in early June of 1947. And so it was also

that the world came to learn of the famous "Marshall Plan."1

All European countries (including even

former enemies Germany and Italy) were invited to participate in the

Plan. But the Russians saw this as a move that would put America at the

center of the European recovery. Consequently, Russia announced that it

would not be participating. It also became quite clear that neither

would they let any of the East European countries under their control

participate in the Marshall Plan.

Thus sixteen countries of West Europe gathered in Paris in July of 1947

to discuss the Marshall Plan, offering the Europeans billions of

dollars in grants – under the condition that they work together to

determine the way the funds were to be distributed. This was one of the

big objectives of the Plan, to get the Europeans to rebuild Europe

jointly, and not just separately as competing nations. Indeed, the

whole European side of the Plan was put under the multinational

Organization of European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), thus helping to

birth a new European unity movement.

1Truman

himself called for the Plan to go under Marshall's name, knowing that

Marshall had a much better standing than he did with the frugal

Republicans of Congress, who would have to approve the huge spending

that the Plan called for.

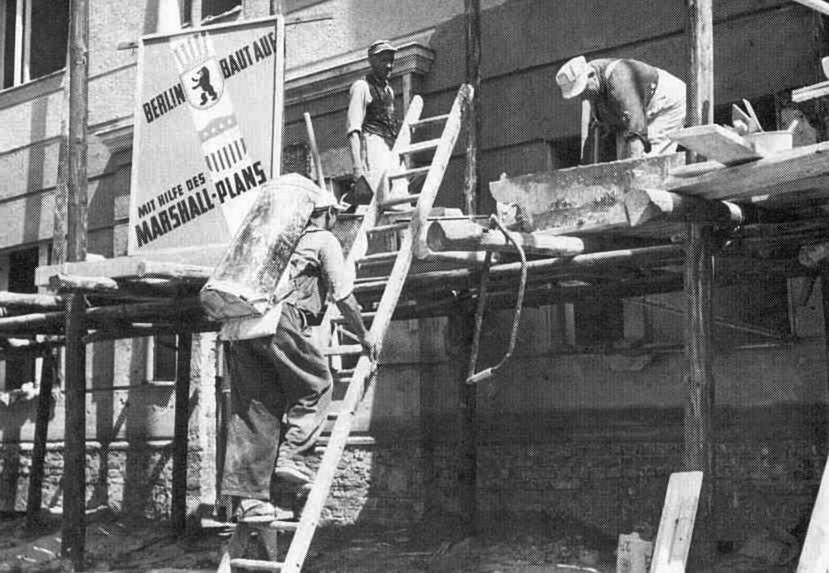

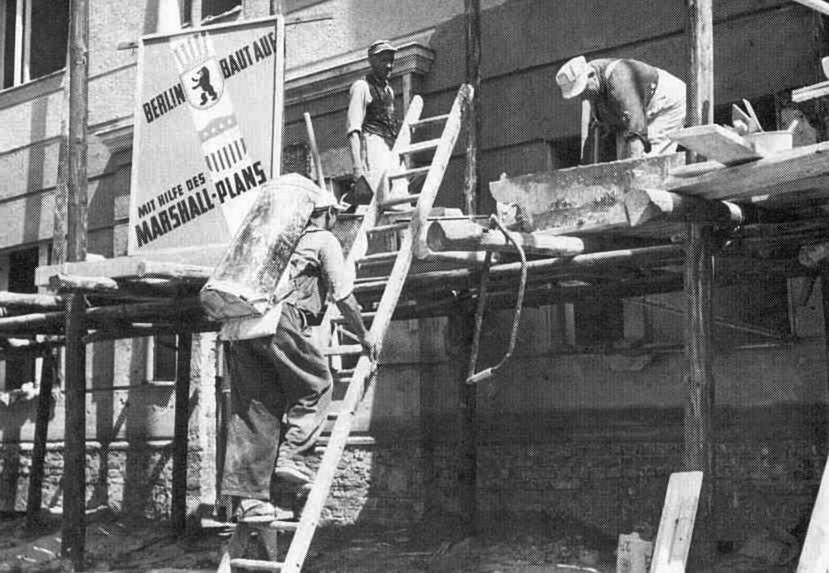

The Marshall Plan to Aid

Europeans in Building a Stable Europe

US Secretary of State (former

General) George C. Marshall explains to Congress details of the European Recovery Program (popularly

named the "Marshall Plan" after him) in January 1948

US Secretary of State (former

General) George C. Marshall explains to Congress details of the European Recovery Program (popularly

named the "Marshall Plan" after him) in January 1948

Marshall Plan food shipments

arriving in Europe

Paid by funds from the US

Marshall Aid Plan, Berliners are employed to clear rubble and begin

reconstruction

Marshall Plan aid working

to rebuild West Berlin

Marshall Plan aid working

to rebuild West Berlin

French farmer using a US

tractor sent under the Marshall Plan

French farmer using a US

tractor sent under the Marshall Plan

Hungry Greek children waiting

for their rations of powdered milk – 1948

A Dutch street before and

after with the help of Marshall Plan assistance

A Dutch street before and

after with the help of Marshall Plan assistance

U.S. International Communications

Agency

Hamburg apartment buildings

in 1943 and again in 1951 – with the help of Marshall Plan assistance

Hamburg apartment buildings

in 1943 and again in 1951 – with the help of Marshall Plan assistance

National Archives

THE SOVIETS TIGHTEN THEIR GRIP ON EASTERN EUROPE ... AND TAKE OVER CZECHOSLOVAKIA |

Electric cable being shipped

by Finland to Russia – 1948 – part of a $300 million

reparations obligation imposed on the Finns by the Soviets

Electric cable being shipped

by Finland to Russia – 1948 – part of a $300 million

reparations obligation imposed on the Finns by the Soviets

|

The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia

But if Truman was having difficulty in awakening

America to the growing danger to Europe and the West coming from

Moscow, an event that took place in early 1948 helped him immensely.

Czechoslovakia, or at least the Czech or western portion of the

country, had long been identified with the modern Western culture of

Europe. It had been a stable democracy before the war, and with its

former president, Edvard Beneš, back in the presidency after the war,

it appeared as if Czechoslovakia would retake its important place in

Western society.

But a number of major problems threatened

that possibility. First was the presence of the Russian Red Army on the

borders of the country, in a position to easily overrun Czechoslovakia

if Stalin decided to do so. Secondly, the Communist Party in the 1946

elections had gained 38 percent of the vote, making it the largest of

the parties in the country, though by no means itself a majority party.

It had been given a number of seats on the national cabinet (though not

a majority of them), but most importantly the premiership (Gottwald)

and the head of the armed forces and the national police. This would

prove to be most strategic for the Communists. Thirdly, the

Czechoslovak cabinet was talking openly about the possibilities of

participating in the Marshall Plan, something that Stalin opposed

strongly. And fourthly, President Beneš was a person who by natural

temperament placed kindly cooperation above all other considerations in

the running of his presidency (he had cooperated with Chamberlain back

in 1938 in agreeing not to use his army of forty well-armed and

well-trained divisions to oppose Hitler’s taking of Czechoslovakia’s

Sudeten borderlands – a huge mistake!). And fifthly, the Communists

looked like they were going to lose a lot of seats in the coming

mid-1948 elections because of a national backlash against their abuse

of their police powers (bullying political opponents, Nazi style).

As 1948 approached, the Communists knew

that they needed to do something bold before they got scooted out of

power. An intervention by the Red Army would likely only backfire

against them. So instead they intensified the use of their police

powers, removing the last of the non-Communist police officials

(despite the outcry of the country). At this point (February 1948) a

number of the non-Communist cabinet ministers offered their

resignations, hoping that it would force Beneš to finally take a firm

stand against the mounting Communist agitation in the government – and

in the streets. But Beneš, fearful of a Soviet military intervention,

accepted the resignations of the non-Communists and, under pressure

from Gottwald, appointed Communists in their place. Then the

Communist-directed police and military began the roundup of

non-Communist officials. Other cabinet members either resigned or bowed

to Communist authority, except Foreign Minister Masaryk, who was found

dead three floors below an open window – declared by the authorities to

be a suicide (actually records opened with the fall of Russias Soviet

government in the early 1990s revealed that in fact he had been thrown

out the window). Thousands of people were arrested, thousands more fled

the country. Then what was left of Czechoslovakian government lined up

behind the Communists, calling for the creation of a new Constitution

(May) – which the voters then approved by an 89 percent favorable vote

(like Hitler's plebiscites!). A vote at the end of May gave the

Communists an absolute majority in the parliament, and soon sole rights

to exist as a political party. At the beginning of June, Beneš resigned

as president, his place was taken by Gottwald, and in September Beneš

died, bringing symbolically Czechoslovakia's democratic era to an

official end. It would be forty years before Czechoslovakia would see

national freedom again.

|

Armed Czech Workers' Militia

who bullied non-Communists into submission marching through Prague

in celebration of the new Communist government ruling

Czechoslovakia

Pro-Western Foreign Minister

Jan Masaryk honored by floral wreath and minute of silence by Communist Premier Klement

Gottwald (left) and Defense Minister Ludvik Svoboda

Pro-Western Foreign Minister

Jan Masaryk honored by floral wreath and minute of silence by Communist Premier Klement

Gottwald (left) and Defense Minister Ludvik Svoboda

HELPING TITO MOVE OUT FROM UNDER STALIN'S CONTROL |

Despite the "Red Scare,"

East-West ideological lines have not yet hardened in America to the point where Truman

can't help Communist leader Tito stay free of Stalin's control

|

Helping Tito's Yugoslavia preserve its independence

Westerners were shocked by the Communist takeover

in formerly free Czechoslovakia ... including finally the

Americans. Truman of course was not. Nor did he come to the same

sense of alarm as did the newly awakened Americans. In America

the Czechoslovakian crisis succeeded in reviving an old Red Scare, one

that would shape nearly all understandings of America's role in the

world for the next generation.

Truman saw things a bit differently. He

certainly understood the challenge that Marxist ideology posed to the

values of Western democracy. But he was more interested in how this

challenge directed political behavior of specific societies, in

particular Stalin's Russia. Truman was more interested in power

politics than in grand ideology. He was thus able to carry off a highly

advantageous diplomatic move, one that within a couple of years would

have been impossible, given the rising ideological mood of America.

This diplomatic move concerned Tito's Yugoslavia.

During World War Two Josip Broz Tito had

headed up a huge military unit of Communist Partisans that gave the

Germans a massive amount of trouble in Yugoslavia. In early 1945, as a

full German defeat looked increasingly likely, Tito took charge of a

new provisional government debating the question of forming a new

republic or continuing the monarchy under the young King Peter II. In

elections held in November of 1945, the pro-monarchists largely

boycotted the event, delivering a huge victory to Tito's

pro-Republicanists – dominated heavily by the Communists, who had

achieved a very high moral standing among Yugoslavia's various ethnic

groups because of their dedication to ousting the Germans from the land.

Though Tito was a loyal Stalinist, he was

also an independent thinker, and had specific plans of his own for

Yugoslavia. Those plans included incorporating all of the Trieste

territory to the northwest of the country (including shooting down

American planes supplying Trieste with aid) plus building his own

diplomatic alliance with the Greek Communists to the south. This upset

Stalin greatly because he was afraid that Tito's activities would call

forward a strong American response (which it did), Stalin having come

to appreciate the strengths of the new American leader, Truman.

Tito also had his own ideas of how he wanted to unite economically the ethnically divided Yugoslavia.

Such independent-mindedness annoyed

Stalin greatly, as he wanted all Communist organizations to function

under his sole authority. Problems between Tito and Stalin thus began

to develop.

Ultimately, Tito refused to attend the

second meeting of Stalin's new Cominform held in June of 1948,

expecting to be verbally attacked by Stalin. Stalin was furious at this

affront and called for Tito's expulsion from the Cominform, Stalin

expecting his personal disapproval to be the undoing of the

independent-minded Tito. When expulsion did not seem to have the

desired effect, Stalin took up his more usual program of seeking to

eliminate any who dared to oppose, or even question, him. None of

Stalin's efforts succeeded however. Tito in turn now went after any

supposed Stalinists in his own country, arresting thousands.

This turn of events opened the way for

Tito to access America's Marshall Plan (1951). Receiving American

financial (and also some military) support did not exactly align Tito

with the growing Western diplomatic alliance headed up by America. But

it effectively made Yugoslavia an openly neutral or non-aligned country

in the Cold War. Indeed, Tito went on to be one of the key leaders of

an international movement – at the time principally among Asian states

– which declared itself to be aligned with neither the West nor the

East. These non-aligned countries saw themselves as comprising a new

"Third World."

Truman was not looking for Yugoslav

loyalty in his swing of economic support behind his former adversary.

What Truman did achieve through this support of Communist Yugoslavia

was keeping Stalin from acquiring Yugoslavia as another satellite

state, one particularly that might have given Stalin the opportunity to

extend his political reach all the way to the Adriatic Sea just

opposite Italy and thus also a position on the Mediterranean Sea, a

goal long sought by the Russians. In supporting the Communist Tito,

Truman had contained Stalin. That loomed in importance much larger in

Truman's mind than the idea of opposing Communism, no matter where it

showed its head, for such ideological crusading would have helped drive

Tito back into Soviet hands, the very thing sought by Stalin.

This was cool-headed thinking on the part

of Truman, something unfortunately that would be lost on the vast

majority of Americans – who at this point were beginning to see things

in absolute Black-White (or Red-White!) dimensions.

|

Marshal Tito (Josip Broz)

- Communist, but anti-Soviet, President of Yugoslavia

Marshal Tito (Josip Broz)

- Communist, but anti-Soviet, President of Yugoslavia

Library of Congress

THE BERLIN BLOCKADE (1948-1949) MAKES THE RUSSIAN COMMUNIST CHALLENGE IN EUROPE OBVIOUS TO ALL |

|

The Berlin Blockade and Airlift (June 1948-May 1949)

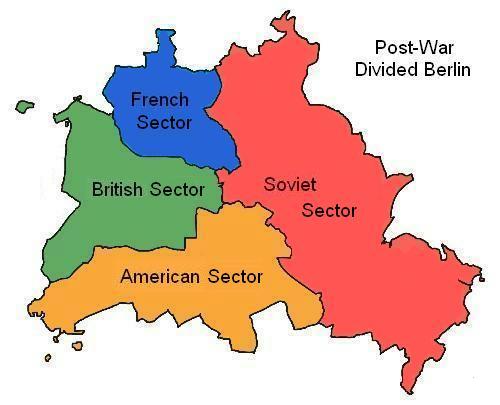

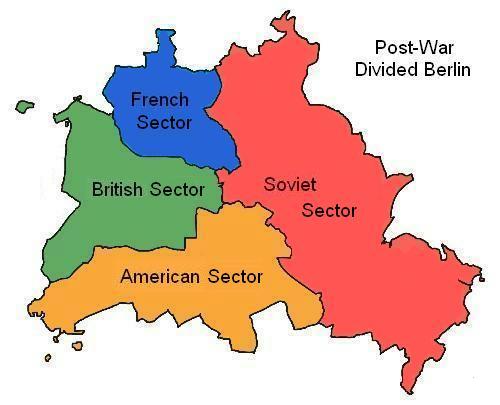

Stalin's expectations at war's end were that the

Western occupation of parts of the Berlin capital city would not last

more than a year or two. But it became increasingly clear over the next

couple of years that the French, British, and Americans were planning

to stay in place in Berlin until the country was fully reunited and all

German occupation zones were vacated by the wartime Allies. Annoyed by

this resistance, Stalin began to put pressure on Berlin by ceasing to

deliver agricultural goods to the city, which in turn caused the Allies

to suspend the shipment from their zones of German industrial machinery

to the Russians. Meanwhile Berliners in the municipal elections were

turning sharply against the Communists, concerning Stalin greatly.

Stalin knew that somehow the Western Allies had to be driven from

Berlin.

To make matters worse for Stalin, the

Western Allies were holding talks in early 1948 about uniting their

three German occupation zones into a single political unit, thus

creating a Federal Republic, complete with its own currency, the

Deutsche Mark, this new Germany also eligible to receive Marshall Plan

funding.

This was the signal for Stalin to shut

down the West’s access to Berlin by way of the rail, highway, and canal

routes which passed through the Soviet-controlled East German zone. The

program started off sporadically at first, the Soviets probably testing

the resolve of the Western Allies. But the Allies responded by

airlifting supplies into Berlin. Then the Soviets eased off their

restrictions, for a while at least, although they harassed the flights

in and out of Berlin (causing a major mid-air crash in April). Finally

in late June with the introduction of the new Deutsche Mark (in West

Berlin as well as the rest of the country) the Russians acted to shut

down completely all land access into Berlin, leaving only air access to

Berlin – but estimating that any such continuing air supply to Berlin

would prove financially ruinous to the Western Allies. On this point

they miscalculated greatly the resolve of Truman not to be bullied out

of Berlin. Berlin and its outcome thus became a symbol of strength and

determination, for both sides of this new contest.

Militarily the Westerners were vastly outnumbered. Soviet military

forces positioned in the Soviet zone numbered about 1.5 million. In

Berlin itself there were only less than 23,000 Western troops, and in

West Germany as a whole less than 100,000. If the Russians decided to

simply grab Berlin, there would have been no way of stopping them. But

that would have constituted an act of war, and the fact that America

now had numerous quite deliverable atomic bombs – and a president

proven willing to use them – caused Stalin to head off any idea of a

shooting war. The idea of shooting down unarmed supply planes was for

the same reason something Stalin knew he could not let happen. But he

believed that he could simply wait out the Westerners, resulting in

their eventual loss of Berlin, and in the process gain a great symbolic

victory. This would then ultimately impress all of Germany with the

idea of who truly ruled in central Europe. Winter was coming and surely

the very expensive airlift would have failed by then.

But the Western airlift by the Americans

and the British was an impressive display of Western resolve, and

Western power. Through the winter the airlift continued, bringing in

more food and fuel than had been brought to the city previously by the

land routes! Also a December 1948 municipal election boycotted by the

Communists led to a complete victory for the pro-Western candidates,

effectively ending the idea of an all-Berlin city government – the

Communists responding by setting up a government of their own in the

Soviet sector of Berlin. Like Germany, Berlin was now divided into two

cities, East and West Berlin. Movement between the two sectors still

continued (ending only with the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961).

But there was now truly an East Berlin and a West Berlin.

The Soviets were gaining nothing by this

maneuver, instead throwing a lot of political advantage to the West.

The French, British, and American sectors found good reason to put

aside any tactical disagreements and work together more closely. The

blockade also inspired the rapid development of the German Federal

Republic. And it impressed the Germans very favorably toward their

French, British and American occupiers who appeared to them more as

their deliverers rather than their occupiers. On the other hand it made

the Russians appear more to be the oppressors of Germany.

And it stirred great sympathy from the Americans for their former German enemies.

Finally in May of 1949, the Soviets

indicated a willingness to end the blockade. The two sides met and the

blockade was lifted. But the bringing of supplies into Berlin by air

continued, just in case. By July the Allies had built up a 3-month

reserve of supplies in Berlin just to send a message to the Soviets to

not ever again try to squeeze the Westerners out of Berlin.

|

A bus used as a roadblock

across a major highway from the West into Berlin

The Berlin Airlift – 1948 – 1949

United States Air Force

The Berlin Airlift – 1948

- 1949 US planes airlifting supplies

into Berlin during the blockade of the city by Stalin

US planes airlifting supplies

into Berlin during the blockade of the city by Stalin

Unloading US planes at Tempelhof

in Berlin

United States Air

Force

US C-54 cargo planes at snow-covered

Wiesbaden Air Base during the Berlin airlift – March

1949

United States

Army

THE INEFFECTIVENESS OF THE U.N. ... AND THE CREATION OF NATO |

|

The increasingly apparent ineffectiveness of the new United Nations

So much had been said at its birth in the last

days of the war – about the way the new United Nations Organization was

going to help establish a secure and lasting international peace – that

expectations ran high in America that finally a formula for preventing

the further outbreak of war (of which Americans had experienced two in

just that many generations) was now no longer a serious danger. Yet,

the major crises that America already found itself facing in the days

and months since the end of the war in no ways seemed to have involved

the United Nations in a constructive way. Was the United Nations just

another one of those fancy dreams sold to the American people by

Idealists, Idealists that had no serious grounding in political

reality? Was the United Nations all just a waste of time and money?

How much Truman had really expected by

way of Russian cooperation in the functioning of the United Nations is

hard to say – though it probably was not much. Americans, however,

became increasingly incensed that the Soviets kept vetoing measures in

the United Nations Security Council (the only part of the United

Nations where forceful international policies could be ordered). Each

Soviet veto was viewed by the Americans as a measure of depravity of

the Soviet position.

Actually, it was the natural response of

a major power that sensed that the vast majority of the members of the

United Nations were for the most part American allies of one sort or

another and thus pretty much lined up against Soviet political

interests everywhere. The Soviets might have wanted to pull out of the

organization altogether but did not, figuring that it was better to

stay in the organization where the Russians at least had veto power,

than to leave the organization to the Americans to rally the rest of

the world in opposing Soviet political interests. Thus the vetoes.

But this meant that American diplomacy

would have to look elsewhere than the United Nations in order to build

a world of peace along lines more favorable to the interests of America

and its West-European allies.

Thus, on April 4th, 1949, some twelve

nations met in Washington, D.C. to sign the North Atlantic Treaty, a

military treaty that bound together the members of this treaty on a

one-for-all / all-for-one basis: America, Canada, Iceland, Great Britain,

Norway, Denmark, Portugal, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and

Luxembourg. For America this was a first: a peacetime military alliance

binding the country to the defense of Europe (actually the defense of

any member, including Canada and Iceland). What inspired this was a

combination of actions already taken among some of the European nations

themselves, plus the crisis of the Berlin Blockade.

The British, French, Dutch, Belgians, and Luxembourgers had already

entered into a similar military agreement in March of 1948 (the Treaty

of Brussels), although that agreement was designed as much as a mutual

defense against a revived Germany as it was an anti-Communist or

anti-Soviet alliance. Then in September of 1948 the treaty members set

up an actual joint military command structure, the Western Union

Defense Organization.

A second piece in the creation of the

North Atlantic Treaty was the political groundwork laid out at home to

get America to join a peacetime military alliance. Here is where the

Berlin Blockade was of great assistance in the effort. But it is

important to note that by 1948 Arthur Vandenberg, the Republican

Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (which must confirm

all American treaties), who had once been an ardent isolationist, had

become an equally ardent internationalist, supporting strongly the idea

of American leadership in a post-war Free World. Talks between

Vandenberg and Marshall's Assistant Secretary of State Dean Acheson and

Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Lovett early in 1948 had touched on

the idea of a North Atlantic military alliance. Vandenberg agreed to

put the matter before the U.S. Senate in May of that year, in the form

of a resolution, to be debated and hopefully supported by the Senate,

clearing the way for America to enter just such an alliance. And indeed

in June the Senate overwhelmingly (eighty-two to thirteen) approved the

Vandenberg Resolution. And thus resulted the gathering in April of 1949

in D.C. of the representatives of the twelve nations to sign the North

Atlantic Treaty.

Very soon a crisis which broke out the

following year (1950) in far off Asia – the Korean War – pushed the

Alliance to take the next step and put into place an actual

organization integrating the contributions by the member nations to the

various military commands, so as to give the Alliance great strength of

unity. Thus out of the North Atlantic Treaty quickly came the North

Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Immediately work began to put

together a number of military divisions (the plan was originally for

ninety-six such divisions, but dropped down in target to thirty-five

divisions) soon to be headed up by General Eisenhower as NATO's Supreme

Allied Commander, working out of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers

of Europe (SHAPE). The organization itself would be headed up by a NATO

secretary general – the first being Churchill’s primary wartime

military assistant, Lord Ismay.

|

Go on to the next section: Post-War Asia

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| |

Truman takes on early global challenges

Truman takes on early global challenges

The mounting sense of a Soviet or

The mounting sense of a Soviet or Crisis in Greece and Turkey ... and the

Crisis in Greece and Turkey ... and the Mounting problems in Western Europe ...

Mounting problems in Western Europe ... The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia

The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia

Helping Tito move out from under

Helping Tito move out from under The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May

The Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May The ineffectiveness of the UN ... and the

The ineffectiveness of the UN ... and the