24. GLORY: THE REAGAN-BUSH (I) ERA

FOREIGN POLICY DEVELOPMENTS DURING THE REAGAN PRESIDENCY

CONTENTS

Troubles in the Middle East Troubles in the Middle East

The Iran-Contra affair threatens to pull The Iran-Contra affair threatens to pull

down the Reagan presidency

China begins to self-reform under Deng China begins to self-reform under Deng

Xiaoping

The rapid decline of the Soviet Empire The rapid decline of the Soviet Empire

Another

event adds a strong touch of Another

event adds a strong touch of

tragedy to the Reagan years

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 279-288.

TROUBLES IN THE MIDDLE EAST |

|

The Middle East's disillusionment with the West

In the years since the overthrow of the Shah of Iran in 1979, Islam had

taken on an increasingly militant anti-Western stance. Whatever Arabs,

Iranians, Turks, etc. had hoped that copying Western culture might

yield, by the 1980s they had begun to lose confidence in that hope.

They were also very bitter about the treatment of their fellow Arabs,

the Palestinians, who had been run out of their homes, their shops and

their farms, to make way for Western Jews pouring in from Europe after

World War Two. The fact that the West, and America in particular,

always seemed to take the Jewish or Israeli side, supporting Israel with guns, tanks and airplanes (though the Israelis

soon developed a number of armaments industries of their own), angered

the Arabs deeply. Finally, seeing America helplessly lose its most

faithful ally in the Middle East, the Shah of Iran, and equally

helplessly unable to do anything about the fervently anti-American

Islamic Republic that replaced the Shah's government, such American

weakness served to embolden greatly a growing number of Islamic

jihadists, who vowed to inflict as much pain and death as possible on

the West, and in particular the "Great Satan," America.

A number of Arab states (Egypt, Libya, Syria, Iraq), actually quite

secular in character (Arab Socialist), had also often taken strong

anti-Western positions with the growing Arab irritation with the

Israeli intrusion. They had engaged Israel in war several times from

the 1950s through the 1970s.

Sadat and Mubarak's Egypt a key exception

However, since the time of

Egyptian President Anwar as-Sadat in the mid-1970s, and, after his

assassination by Muslim fundamentalists in 1981, with the new

presidency of Hosni Mubarak, Egypt turned to the West, principally the

United States, for close friendship. Both of these Egyptian presidents,

Sadat and Mubarak, whose regimes were quite secular in nature, well

understood the dangers of Islamic fundamentalism, the need to have

peaceful relations with Egypt's neighbor Israel, and the need for the

vital support of the United States to give muscle to this policy.

With the cooling of Arab nationalism in Egypt, there

was almost an automatic transfer of radical nationalism next door to

Libya. Under the presidency of a young Muammar al-Gaddafi, Libya became

an Arab Socialist state with a very strong pro-Soviet orientation.

Gaddafi came down hard on the Italians living in Libya (former

colonials who now had to flee the country) and any Libyans opposing him

or his policies (many were murdered even abroad by special Libyan

agents). At the same time, his country became a haven for radicals of

all sorts – Irish, German, Japanese as well as Arab terrorist groups.

And he financed a number of other anti-Western terrorist groups around

the world.

Actually, Gaddafi was quite erratic in his political tendencies, after

first trying Arab Socialism (spreading the benefits of the Libyan oil

economy widely to all Libyans), then undercutting his own government

bureaucracy with efforts to create local-community initiative on the

basis of his personal call to Revolution through the distribution of

his Green Book (not unlike Mao's Cultural Revolution with his Little

Red Book ) to serve as the source of inspiration for his Revolution.

Then after having seized all private property, he decided to try to restore private economic initiative

again. He also succeeded in alienating the strong Muslim Brotherhood

operating in Libya, when he endeavored to institute Shari'a (Muslim

law) through his revolutionary organization, the Jamahiriya, rather

than through normal Islamic clerical organizations. And he could be

ruthless when he felt that his programs were being opposed by

individuals and groups.

The same held true in his erratic foreign policy. He was once a

supporter of Egyptian President Nasser's pan-Arab nationalism – but

became a bitter opponent of Nasser's successor in Egypt, President

Sadat. At one point he turned to pan-Africanism as his latest identity

direction, funding all sorts of local African groups, usually

liberationist in character, thus angering fellow African heads of

State. He also supported terrorist groups such as the Irish Republican

Army and Islamist jihadists in the Philippines. He also had a run-in

(October 1985) with America when he was attempting to monitor American

navy exercises being conducted in the Mediterranean Sea – and President

Reagan responded by authorizing the shooting down of Libyan jets.

In April of 1986 Gaddafi was behind the bombing of a Berlin discotheque

which a number of U.S. soldiers frequented. This time Reagan retaliated

by directing a massive American air attack on numerous Libyan military

sites, as well as Gaddafi's Presidential Palace.

The United Nations howled, and passed a resolution condemning the

United States for this attack. But a number of countries stood with the

United States. And the Soviet Union spoke out against the attack, but

was unwilling to give any comfort to Libya, because the Soviets

themselves were becoming concerned about some of the rogue actions of

their Libyan ally. This event began the backing away of Soviet support

for Libya.

The non-state military organizations

But with time, the real struggle

for Arab rights would be fought not by Arab states but by non-state

organizations that had no official location in the Middle East, but

simply drifted back and forth across Arab state boundaries in

conducting their anti-Israeli, anti-West, anti-American missions. The

oldest of such Arab non-state organizations in the Middle East (formed

in the 1960s) was the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). It was

officially sponsored by the Arab League and supported financially by a

number of Arab states. Its mission was more particularly focused on

removing the Jewish "intruders" from the PLO's homeland, Palestine.

Another Arab organization, Hezbollah, grew up in the early 1980s and

reflected a new Shi'ite militancy coming from Iran1 after the Shah's overthrow. Indeed, Hezbollah was formed with the help of Iran for the

purpose of supporting the Shi'ites living in multi-ethnic Lebanon

(Sunnis, Druzes, Christians and others, as well as Shi'ites, make up

this multi-ethnic society).

Then later in the 1980s a new Palestinian group, Hamas, came forward,

as it began to appear that the PLO was willing to work out some kind of

compromise with Israel to share Palestine. Hamas refused adamantly to

enter into any such compromise. Hamas was much less secular than the

PLO and more militantly Islamic (Sunni) in its ideology, a sign that

the Islamic faith was beginning to upstage secular Arabness as the

basis for political identity in the Middle East.

1Iran was/is staunchly Shi'ite, whereas the rest of the Muslim Middle

East tends to be Sunni; the two wings of Islam have an intense hatred

of each other.

|

In November of 1986 a newspaper story in Lebanon

made its way back to America and exploded into a full-scale U.S.

government scandal, which would make Watergate look puny by comparison.

However politically, the results were quite different from those of

Nixon's Watergate, because politically the times were quite different.

It was first revealed that U.S. weapons had been sold to Iran, in part

to help gain the release of American hostages in Lebanon from

Hezbollah, operating there presumably with Iran's assistance.

In part the sale was made also to provide funding for a CIA-backed

guerrilla group, the "Contras," attempting to overthrow the leftist

Sandinista government of Nicaragua (drug money was also supposedly

being funded to support the Contras).

The context of the Contra support was the turmoil that shook the whole

of Central America. El Salvador and Nicaragua were being deeply

challenged by pro-Socialist guerrillas attempting to overthrow

traditional regimes, regimes blamed for very sluggish economies cursed

with high unemployment. Things were also tense in Guatemala and

Honduras. But the violence was running very high in El Salvador. And

worse, the pro-Socialist (Communist?) Sandinistas in Nicaragua were

getting a lot of support from Castro's Cuba, indicating an even greater

threat to America's allied governments and the American political

position itself in this key Central American country. Thus the support

of the anti-Sandinista Contras.

However, all of this support of the Contras was not only being

conducted clandestinely, but also quite illegally. A

Democratic-Party-controlled Congress had passed a ruling that the

Administration was not to assist the Contras in their rebellion. And

the thus-illegal operation clearly had the authorization somewhere rather high up in the Reagan

administration. Reagan's role himself in the whole affair was not quite

clear.

The Tower Commission Report

A three-man Tower Commission that was

quickly set up by Reagan to look into the matter (and in general to

survey the role of the National Security Council in monitoring such

matters) concluded its work the following February (1987), finding

little concerning any direct involvement of Reagan in the matter.

In March, Reagan, in a TV address, apologized to the nation for the

crisis. He explained that besides trying to set innocent Americans

free, he was trying to improve Iranian-American relations by working

more closely with Iran's political "moderates."

Finally that November, a report published jointly by Senate and House

committees set up in January, which had conducted widely-watched

televised hearings from early June to early August, concluded that

there were no grounds for bringing criminal charges against the

President. But the rreport also concluded that Reagan should have been

more careful in supervising what was going on right under his nose.

Reagan's national approval rating plummeted abruptly from over

two-thirds of the nation to less than one-half because of the scandal.

But Reagan was not going to be "Watergated" out of office, even with

the huge Democratic Party majority in both houses of Congress.

Politically it was too dangerous to take him on, particularly as

Reagan's approval rating soon climbed back up again because American

eyes were turned more to his successes with Gorbachev in settling the

Cold War than they were to his failures in the Iran-Contra affair.

Nonetheless, the affair undermined seriously the American commitment

never to pay for hostages, lest payoffs should encourage more political

kidnaping in the Middle East (which it certainly did). And the affair

made relations with Latin American neighbors much more difficult.

Impeachment now a commonly used political weapon It also served to

make presidential impeachment – which had been unused for over a

century (1868-1973) – now since Watergate a rather frequent

Congressional political tool designed to bring down an occupant of the

White House. To turn this into a now frequently-employed partisan

political instrument was a very dangerous precedent to bring to

American democracy.

To undercut the authority of a national leader by having that leader

arrested and convicted for "crimes against society" was a frequent

political game played in Third World countries. To have U.S.

Congressional opposition now frequently taking up this same political

weapon (or then backing down when it became apparent that this action

was politically suicidal for the accusing group) should have caused great concern

within democratic America. But sadly, political impeachment had now

become part of modern America's new bag of political tricks.

In any case, in 1987 the American public had made it quite clear to

their representatives in Washington that they liked their strong

president and had no desire to see their country fall back into

ideological division such as it had gone through in the later part of

the 1960s and the whole of the 1970s – and which Reagan had finally

brought the country out of. Impeachment was not an option ... not at

the moment, anyway.

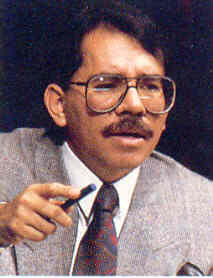

|

Nicaraguan President and

Sandinista leader, Daniel Ortega,

campaigning in support of his government

- 1984.

Sandinista leader Daniel

Ortega elected President of Nicaragua – 1985

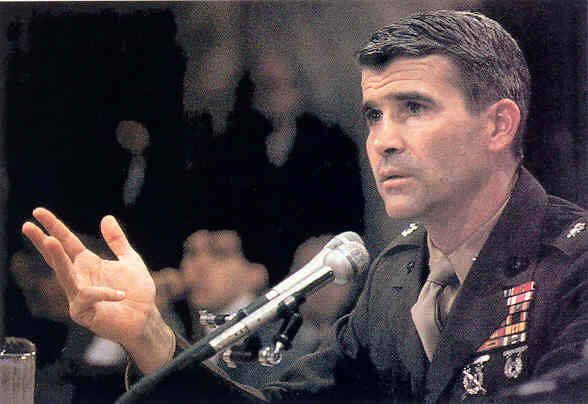

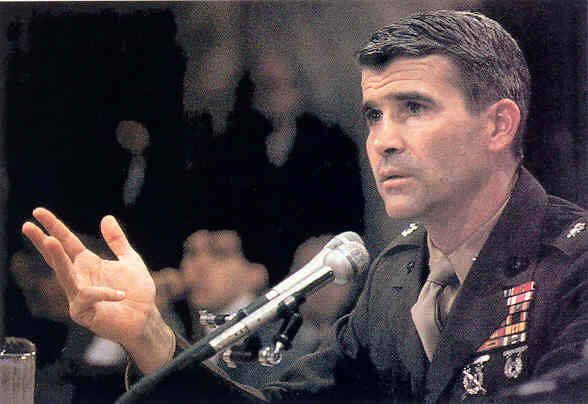

Lt. Col. Ollie North Testifying

before Congress in the Iran-contra affair – July 1987

Oliver North testifying about

the Iran-Contra affair.

President Regan received

the Tower Commission Report in the Cabinet Room

with Senators John Tower

(l.) and Edmund Muskie (r.) attending – February 26, 1987.

CHINA BEGINS TO SELF-REFORM UNDER DENG XIAOPING |

|

Although the radical phase of Mao's Cultural

Revolution was over as China entered the 1970s (Army General Lin Biao

had been called in to settle the young Red Guards down and get things

back to work, Mao remained still very much in control of the Chinese

Communist Party (CCP). And the Idealism of the Cultural Revolution also

remained in place. According to Mao, the Chinese economy was not to be

run by party or government bureaucracy (as in Russia) nor by a

capitalist class (as in America) but from the commitment of the Chinese

people themselves to work toward high social goals – as outlined by Mao

himself, of course.

During the border conflict with the Russians in 1969, General Lin Biao

had taken on too much authority, and Mao purposely raised his long-time

friend, the political pragmatist Zhou Enlai to power, to counterbalance

the radical hardliner Lin's influence. Ultimately Lin overplayed his

hand (he was also very opposed to Zhou's opening up to the Americans)

and was killed in a plane crash as he was making an escape to Soviet

Russia in September of 1971. But soon Mao's actress wife Jiang Qing

took over Lin's position as the head of the CCP radicals.

In 1972 Mao suffered a stroke – and Zhou was diagnosed with cancer.

Thus the CCP moved to rehabilitate formerly-disgraced (and imprisoned)

Deng Xiaoping, as Zhou's possible heir. He too, like Zhou, was of the

pragmatist, not radical, political mindset. But this then stirred Jiang

Qing and some of her radical allies to counter-action. Things got tense

inside the party as Mao's struggle with his health intensified.

Then in January of 1976 Zhou died, and Mao replaced Deng with Hua

Guofeng (Hua was someone who stood somewhere in the middle of the

radicals and pragmatists). But then in September Mao died. And without

Mao's protection, Mao's wife Jiang and others of the radical "Gang of

Four" were arrested the following month. In the meantime, Hua tried to

make himself appear to the Chinese people as the spiritual successor to Mao.

But the CCP was moving step by step in the direction of the

pragmatists. Many of the three million officials purged during the

Cultural Revolution were slowly restored and gradually a number of

pragmatists were reinstated to the CCP Central Committee. At this

point, although Hua remained at the top executive post, the real power

behind the party was the restored Deng.

However Deng had evolved substantially in his thinking on economic

matters over the years, and had come to the realization that China

needed to open itself up to foreign investment in China and become

active in the global market (like Chinese Taiwan) if the Chinese

economy were ever to come to real growth. Thus in 1977 the Cultural

Revolution was declared over, and the next year Deng announced his Four

Modernizations program (agriculture, industry, science and defense).

Fourteen cities were designated as investment centers, with the idea of

opening the Chinese economy to foreign investment, to get the Chinese

economy back up and running again.

In 1980 and 1981 Hua was removed from some of his government positions,

and a number of party leaders were appointed instead to some of these

same positions. Deng took for himself only the position as chairman of

the Central Military Commission. Nonetheless from this position Deng

would hold tight control over Chinese politics during the entire 1980s.

In 1981 Jiang Qing and the other three members of the Gang of Four were

finally put on trial for treason. All four were convicted (death

sentences, soon reduced to life imprisonment) and the Maoist radical

wing of the Party was basically dismissed or silenced.

Deng now moved China toward his more "pragmatic" program of

market-based economic reform. Although the party and its bureaucracy

would still preside over matters, the actual initiative in the

development of the Chinese economy was directed toward the Chinese

themselves, especially among the more personally ambitious, much as in

the West's own market-driven system.

Deng's bringing the Chinese on board with his program at the

grass-roots level would produce amazing achievements, but ones however

that would fail to take hold elsewhere within the Communist or

Socialist world (including Russia, as we shall see below). Chinese

exports now began to grow rapidly. This occurred particularly because

China's new Western trading partners (who were strong supporters of

this Chinese economic transition to market economics) allowed the

official subsidizing of the Chinese currency exchange rate. This kept

the prices of Chinese products very low on the international market,

and the cost of foreign goods very high in China. This gave the Chinese

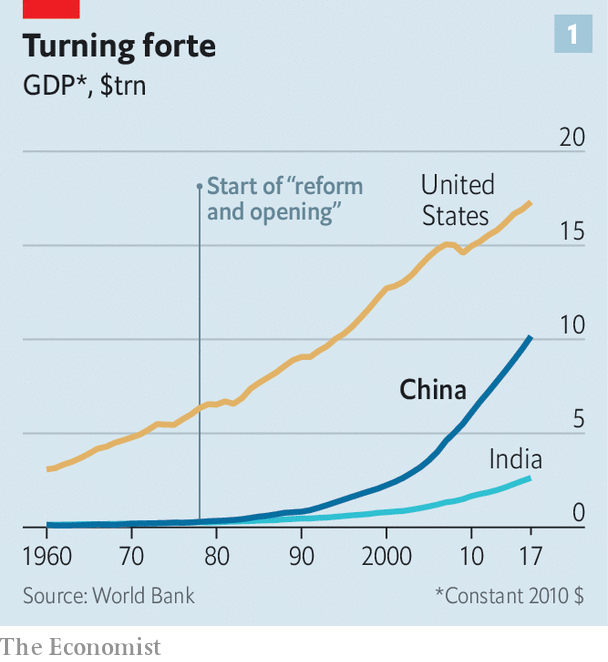

economy a major boost. Chinese industrialism now took off at incredible growth rates of around 8-10

percent annually during the 1980s and 1990s (although there was a dip

in 1989-1991).

|

Deng Xiaoping

A huge billboard in Shenzhen celebrating Deng's economic reforms

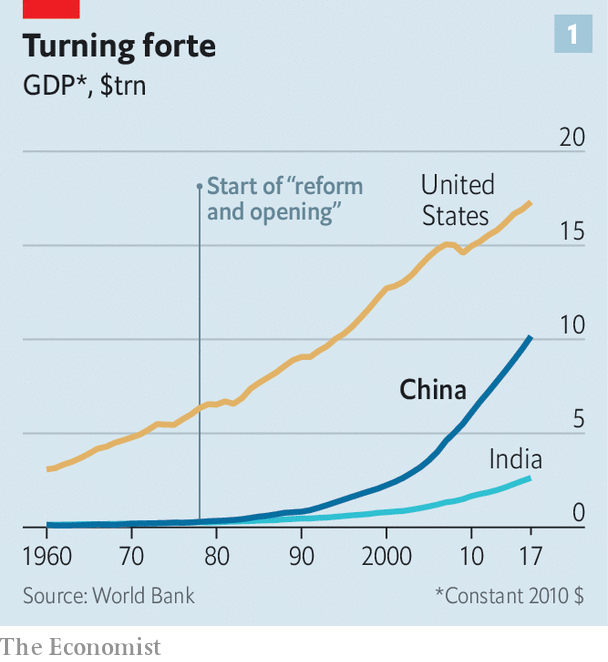

Comparative economic growth of US, China and India 1960-2017

THE RAPID DECLINE OF THE SOVIET EMPIRE |

|

Economic and social crisis in the Soviet Union

A

similar social-economic crisis had hit Soviet Russia during the 1970s,

but unlike China, it continued into the 1980s. And also unlike China,

Soviet Russia would not find a successful path out of this crisis.

Soviet farming had never done well since the days of Stalin's forced

collectivization, and Russia, once a major exporter of grain, long had

to import grain to feed its people, a great burden on its foreign

currency reserves. Also the high cost of Soviet armaments had long cut

into the ability of the state to offer its people a level of civilian

material housing and comforts that a "workers' paradise" should have

had. Most Soviet workers knew well that their worker counterparts in

the capitalist West lived much better off than they did. In the Soviet

Union, the workers' paradise had the feel of a Third World country.

This in turn was creating a decided drop in "working class patriotism"

which was taking the form of a large amount of worker absenteeism at

the job site, and even when workers did show up, it was not unusual for

them to be drunk. The Soviet economy was in trouble, big trouble.

The one thing Russia had in ample supply that was greatly needed abroad

and could bring in hard currency to finance Soviet economic

shortcomings was oil (and eventually also natural gas). Thus the Soviet

Union's decision in 1981 to break from the oil pricing of the OPEC oil

cartel and sell oil, lots of oil, for whatever price it could get. And

with the underbidding of oil pricing by the Soviets, the price of oil

came tumbling down.

Thus the Soviets would not reap the windfall profits from oil that they

had been hoping for. Indeed, many of the oil exporting nations now also

found themselves in difficulty as their expected revenue from oil

dropped away and they had to cut back drastically on investment plans

for growth.

The Soviet quagmire in Afghanistan

In Soviet Russia things continued

to go from bad to worse. The Muslim revolution in Iran had quickly

spilled over into neighboring Afghanistan in the early 1980s as Afghani

Muslims answered the call to jihad (the struggle against Evil) against

the Soviets and their puppet Communist regime in Kabul. At the same

time, America did not want the Soviets occupying Afghanistan, a point from which they

could put pressure on the Persian Gulf region (the major source of the

West's oil). Consequently, America undertook to supply the Afghan

rebels (the mujahedin) with advanced missiles that could easily kill

Soviet tanks and jets. The Soviets were finding themselves bogged down

in a war that, even with a massive military presence in the country,

they could not bring to a favorable close. It was as if Afghanistan

were the Soviets' "Vietnam." Soon anti-war feelings began to grow

within Russian society, and even within the military itself. Russia was

in deep trouble in Afghanistan.

Thus by the early 1980s Soviet morale was sagging terribly, at a time

when America's was picking up. Finally in 1988 the decision was made to

withdraw from Afghanistan, the task completed by early 1989.

The rapid turnover in Soviet leadership (1982-1985)

When Brezhnev died

in late 1982, he was replaced as head of the regime by a KGB (Soviet

secret police and intelligence operations) hardliner, Yuri Andropov.

Andropov tried to tighten party discipline and clamp down on the

political dissent that was spreading rapidly around the country. But

his health was failing and only a little over a year later he died. He

was replaced by another equally sick official, Konstantin Chernenko,

who served as Soviet leader no more than a year before he too died. But

this time Soviet leadership was taken over by a younger and strongly

reform-minded Mikhail Gorbachev, who knew that something dramatic was

going to have to take place to save the Soviet Union from simply

collapsing.

Reagan meanwhile had been stiffening his

position against the Russians, announcing back in 1982 in a speech

before the British Parliament how he intended to push the Russian "Evil

Empire" to the point of collapse. He put the B1-Bomber program back in

place (which Carter had canceled), armed NATO with America's Pershing

II missiles, and in 1983 announced a plan (the Strategic Defense

Initiative)2 to develop a laser-guided anti-missile defense system that

would block incoming nuclear missiles, thus undercutting the Soviet

nuclear deterrent. It would be expensive, at least expensive enough

that the Soviets, whose economy was stumbling at this point, would be

unable to answer the challenge with a countering program of their own.

But in general, the American population was quite approving of Reagan's

new "Star Wars" program. But in the end, the program would not really

be needed, for the Soviet Empire crumbled before the decade was out.

But mostly this challenged Russia in a way that the new Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev knew that his country could

not effectively answer. Gorbachev responded instead by offers of a new

look to the Soviet Union and a new attitude toward the West.

Reagan, while carrying Teddy Roosevelt's "Big Stick" (his ramping up

of America's defense posture) was also ready to follow Roosevelt's

policy of "walking softly" with respect to the Soviet Union's new

leader Gorbachev. Reagan began to meet with Gorbachev to see what

possibilities existed to develop a new thaw in East-West relations

(similar to what was happening in U.S.-Chinese relations at that point).

In 1986, Gorbachev began to put into operation a number of social

reforms for Russia, the most important of which were glasnost (a new

openness in the society), perestroika (a restructuring of the economic

system) and demokratizatsiya (democratization of the political system).

This was designed to put a new lease on life in Communist culture.

Gorbachev's reforms were greeted with great enthusiasm everywhere – in Russia, in Eastern Europe and even in America.

But for Reagan, this was not yet enough. In June of 1987, as he stood

before the Berlin Wall at the Brandenburg Gate, Reagan uttered a

challenge which would have a dramatic impact on everyone:

. . . if you truly want peace and liberalization, Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

The gate did not open right away. The wall was not torn down right

away. But things were now headed that way. In the last years of his

administration, Reagan had become a fond friend of Gorbachev, visiting

back and forth between America and Russia. Reagan truly wanted to

support Gorbachev in his effort to reform Russia.

But in the process Gorbachev had set loose in the Soviet Union a small

opportunity for the revolution of rising expectations to take root.

Could he reform Russia without having it break down in revolutionary

chaos in the process?

The answer to that question would reveal itself soon after the new

American presidential administration under Reagan's Vice President,

George H.W. Bush, got underway in 1989.

2Termed derisorily by Kennedy as Reagan's "reckless Star Wars schemes."

|

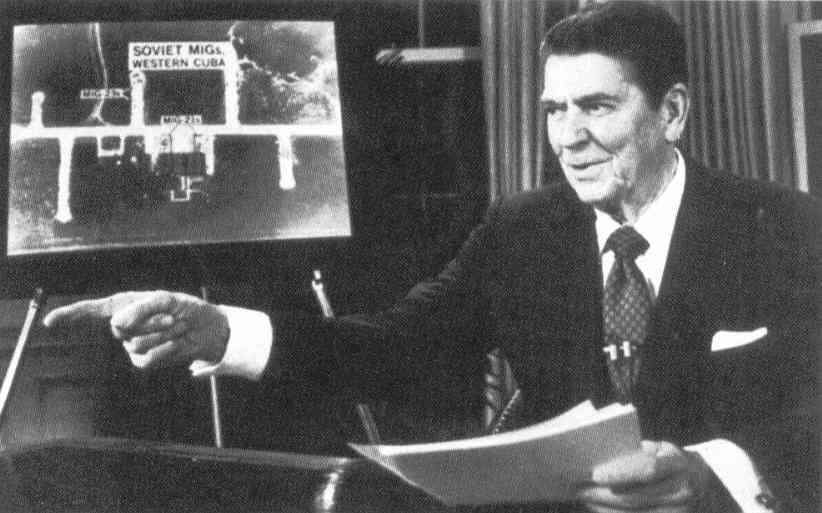

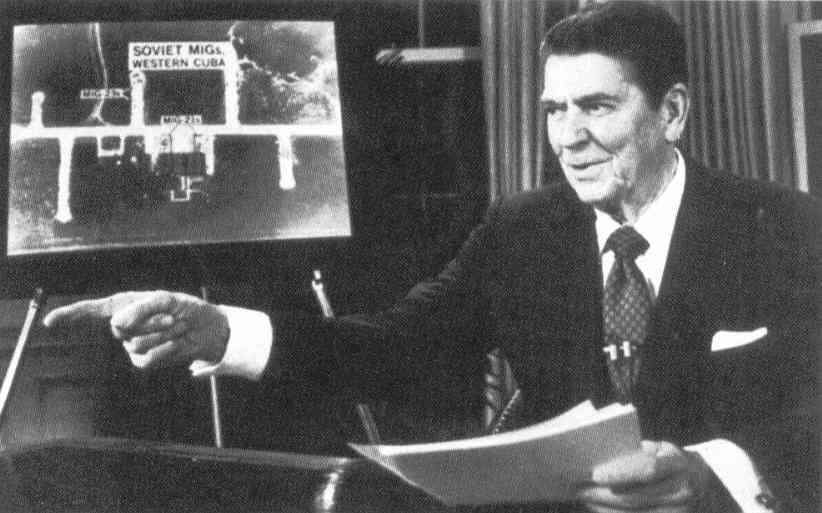

Reagan challenges the cash-short

Soviets to another round in the arms race

with the introduction of the

"Star Wars" strategy

In a televised speech, Reagan

reveals his Strategic Defense Initiative

or "Star Wars" plan – March 23,

1983

A political stirring is rising in the

Soviet empire in East Europe

The huge Polish reception

to Pope John Paul II's visit in June of 1979

constituted a huge challenge

to the authority of the Polish Communists

Then, led by Lech Walesa's and his dock-workers' union "Solidarity,"

Polish workers give serious

affront to the Communist system in Poland

Lech Walesa leading the strike

of workers at the Lenin Shipyards in

Gdansk, Poland – August 30, 1980

Striking workers at the Lenin

Shipyard – 1980

Polish military under Gen.

Jaruzelski, fearful of a Soviet military reprisal (such as occurred in

Czechoslovakia in 1968), retake Poland from Solidarity – December 1981

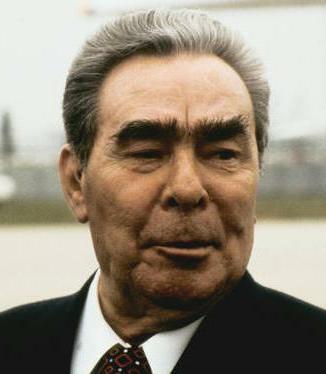

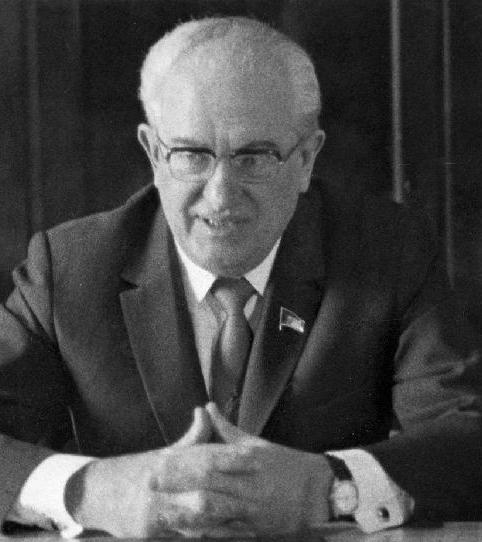

But things are also stirring in the Soviet Union, as the Soviet Empire's leadership

changes hands rapidly over the course of the early-to-mid 1980s

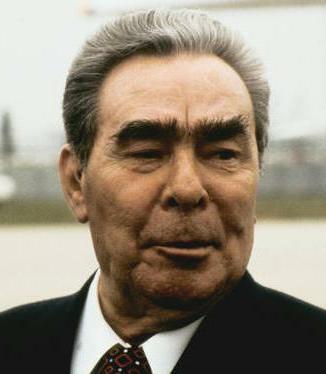

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Brezhnev

Communist Party Chairman

1964-1982

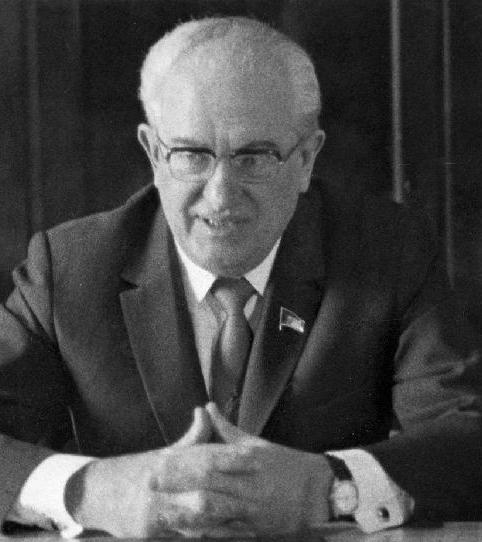

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Andropov

Communist Party Chairman

1982-1984

Konstantin Cernenko

Konstantin Cernenko

Communist Party Chairman

1984-1985

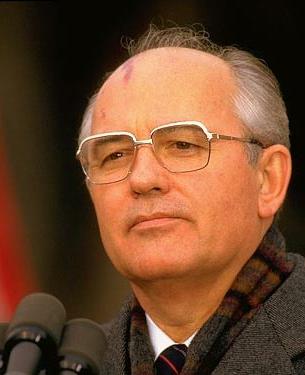

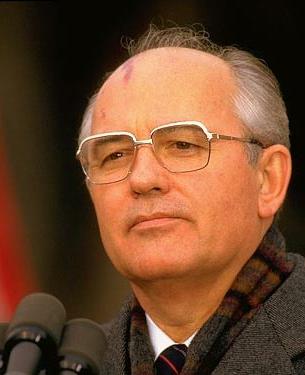

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Gorbachev

Communist Party Chairman

1985-1991

Also ... the Soviet position in Afghanistan begins to come apart (early 1980s)

Babrak Karmal

chairman of the Revolutionary Council of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

(1979-1986). The Soviets had installed

this Afghan Communist leader in Kabul in 1979 in the hopes

that he might

keep more effective control over Afghan politics than had

his Communist predecessor, Hafizullah Amin – whom Soviet troops assassinated

when they first invaded the country in 1979.

Babrak Karmal

chairman of the Revolutionary Council of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

(1979-1986). The Soviets had installed

this Afghan Communist leader in Kabul in 1979 in the hopes

that he might

keep more effective control over Afghan politics than had

his Communist predecessor, Hafizullah Amin – whom Soviet troops assassinated

when they first invaded the country in 1979.

Soviet paratroopers aboard

a BMD-1 in Kabul

Soviet helicopters working

with Soviet tanks in Afghanistan

Afghan village destroyed

by Soviet troops

Reagan listening to the

mujahidin's

description of Soviet atrocities in Afghanistan – February 1983

Texas Congressman Charlie

Wilson in Afghanistan

Wilson was a prime mover

in Operation Cyclone, in which the US sent $ millions to support the

mujahidin in their fight against the

Soviets (unfortunately much of the money ended up in corrupt Pakistani

military hands). Resistance by conservative

Muslim mujahidin however is grinding down the Soviet effort to maintain Communist control

in Afghanistan.

|

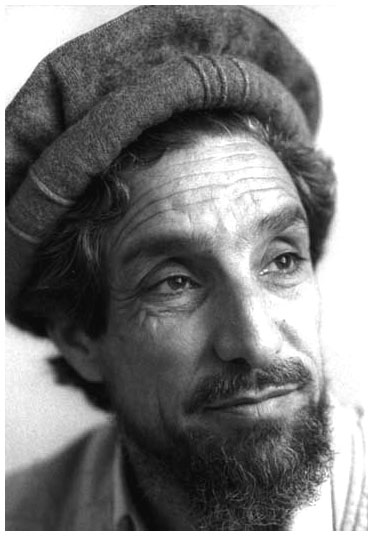

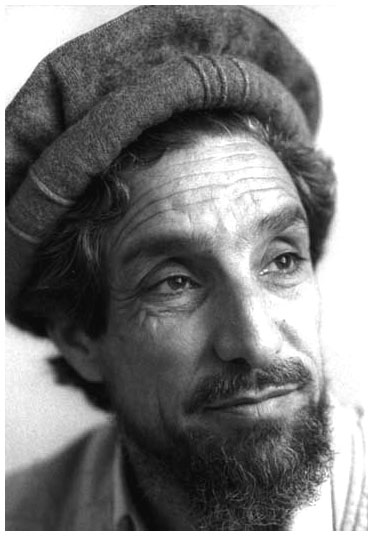

Ahmad Shah Massoud – the

"Lion of Panjshir"

Ahmad Shah Massoud – the

"Lion of Panjshir"

|

This

engineer-turned-mujahidin

proved to the the most effective of the Afghan resistance commanders. When the Taliban later

took over the country, he became their prime opponent. The Taliban

assassinated him just days before the September 11, 2001 attack

on the New York Twin

Towers)

|

Well armed mujahedin

confronting

Soviet troops in Afghanistan

The new Soviet leader Gorbachev was pushing for a new face

to Communism

with the policies of perestroika (economic reform), glasnost (personal freedom),

and demokratizatsiya (democratization)

A Russian practicing

glasnost

on a Russian street

Gorbachev welcomed in Prague

for his reforms

Soviet Premier Gorbachev

meets with French President Mitterrand in Paris – 1985

Reagan and Gorbachev at the

first Summit in Geneva, Switzerland – 19 November 1985

Gorbachev and Reagan meet

in Reykjavik, Iceland – autumn 1986

"Mr. Gorbachev, tear down

this wall!" – June 1987

"Mr. Gorbachev, tear down

this wall!" – June 1987

Gorbachev, realizing that the Afghan War was merely weakening further the Soviet strategic

position globally, decides to call it quits in Afghanistan – July 1987

Soviet Commander Boris Gromov

announcing the Soviet troop pullout from Afghanistan – July

1987

Afghan troops (on the left)

watching Soviet troops leaving Afghanistan – 1988

Gorbachev with Reagan on

a summit visit to Washington – 1987

The Gorbachevs visit the

Reagans in Washington – December 1987

Gorbachev and Reagan sign

the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in Washington – 1987

A Soviet sentry guarding

ICBMs scrapped under a 1987 disarmament treaty with the US

Gorbachev and Reagan in Moscow

- 1988

Gorbachev and Reagan in Moscow

- 1988

President Ronald Reagan visiting

with Soviet Premier Mickail Gorbachev in Moscow,

chatting in front of St.

Basil's Cathedral on Red Square

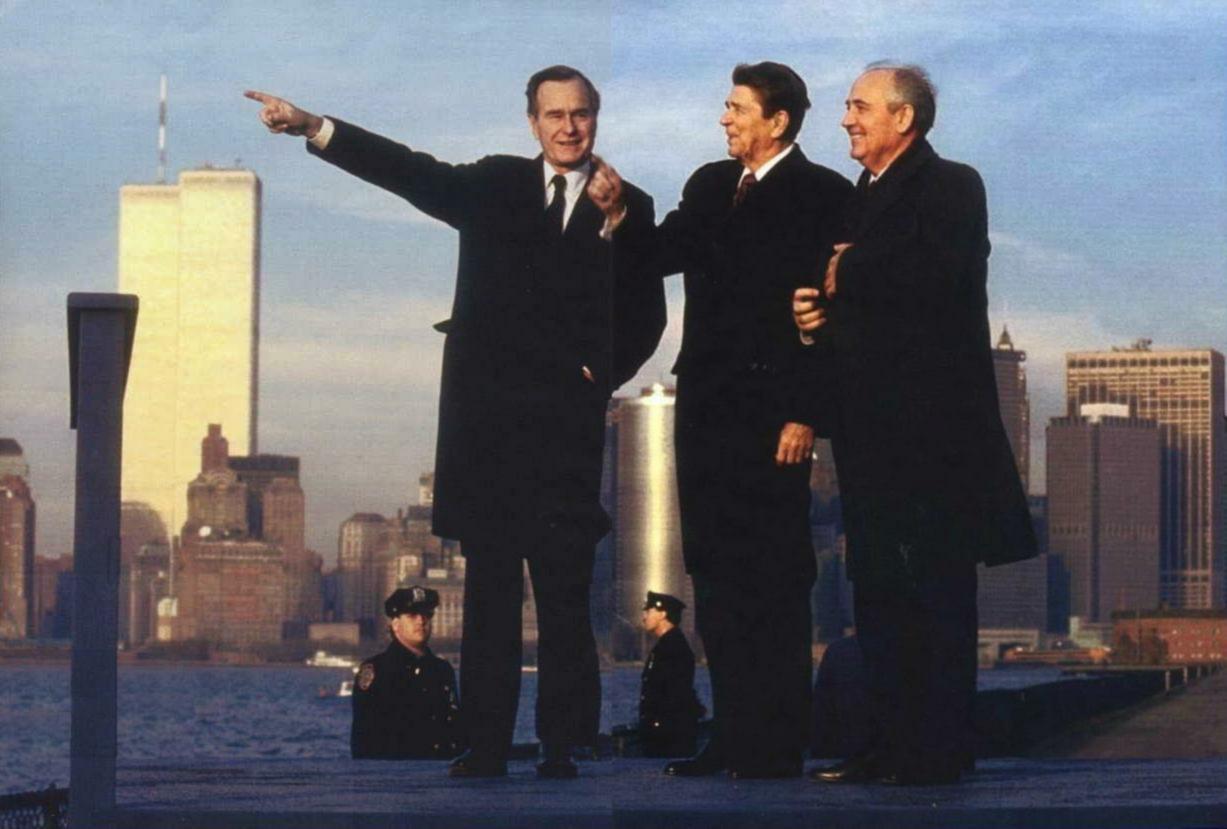

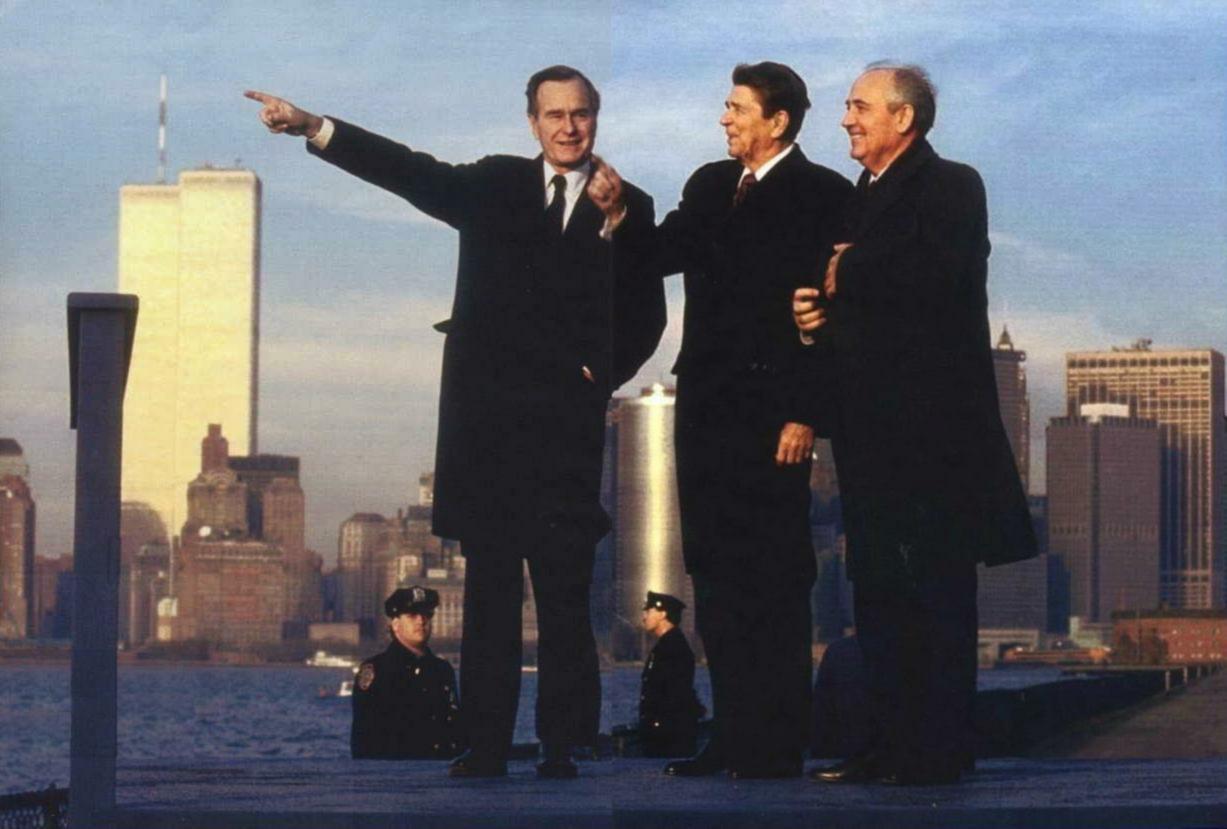

Soviet Premier Gorbachev

visiting Reagan and Bush in New York shortly after the latter's

electoral victory in 1988

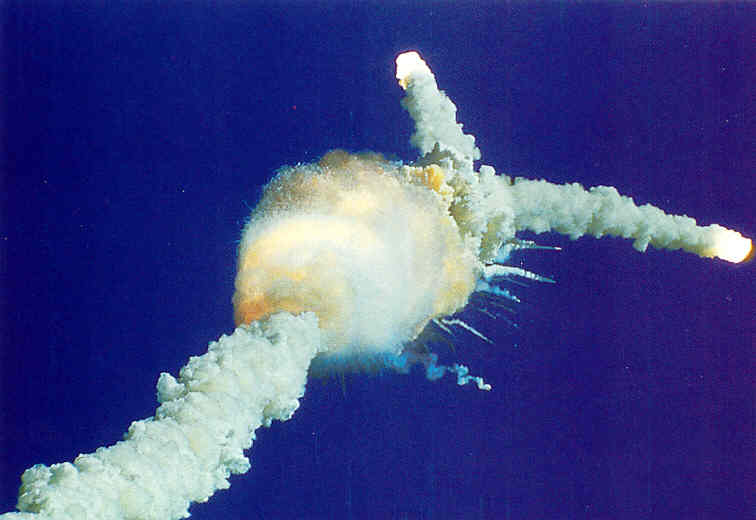

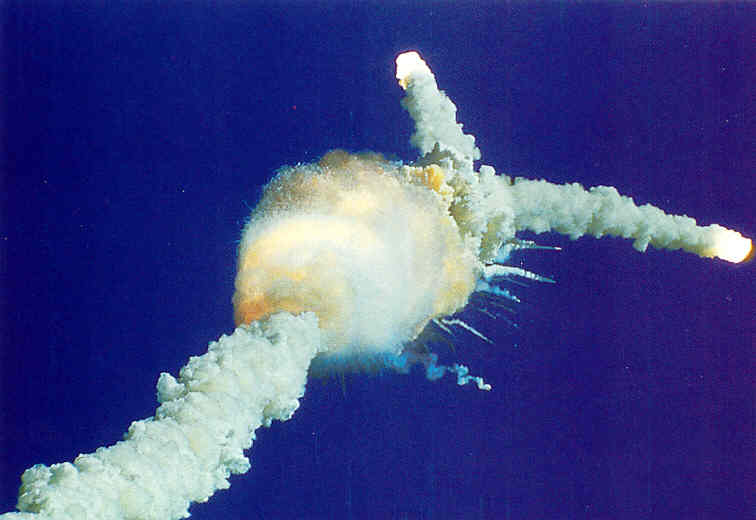

ANOTHER EVENT ADDS A STRONG TOUCH OF TRAGEDY

TO THE REAGAN YEARS |

On January 28, 1987 the space shuttle

Challenger exploded soon after launch -- killing all 7 crew-members aboard.

|

Go on to the next section: Bush (Sr.) and the World

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| |

Troubles in the Middle East

Troubles in the Middle East

The Iran-Contra affair threatens to pull

The Iran-Contra affair threatens to pull China begins to self-reform under Deng

China begins to self-reform under Deng The rapid decline of the Soviet Empire

The rapid decline of the Soviet Empire

Another

event adds a strong touch of

Another

event adds a strong touch of