15. DEPRESSION ... AND MORE DICTATORSHIP

(THE 1930s)

THE DEPRESSION'S IMPACT ON EUROPE

CONTENTS

Britain and the Great Depression Britain and the Great Depression

Rebuilding the French economy Rebuilding the French economy

Austria Austria

The new Republic of Czechoslovakia The new Republic of Czechoslovakia

Germany, Italy and Japan move into a Germany, Italy and Japan move into a

closer relationship

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 136-139.

BRITAIN AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION |

Britain

would join the industrial world in the great catastrophe which fell in

the West at the beginning of the 1930s ... but would fare better than

many of the other nations. At first the British financial and

industrial sectors were hard hit by the panic of the capital markets

... and by the American decision to impose tariffs on non-American

goods in the hope that this would protect struggling American goods

against foreign products. But this merely produced the decision

of other governments to do the same, drastically restricting global

markets at a time when they needed to be more open than ever in order

to invite production.

Britain responded by creating a protected

trade region with its dominions overseas ... large enough to encourage

the continuing movement of raw materials and finished products back and

forth within the imperial zone. Thus Britain and the dominions

fared better than much of the rest of the world ... though Britain

still had to watch government expenditures (especially such items as

military men and equipment in a time of "peace"). But British

industry was also modernizing and developing new lines of efficiency

that would help the British economy enormously.

REBUILDING THE FRENCH ECONOMY |

Then

the Great Depression hit over the winter of 1929-1930. At first

it looked as if France might escape its grip ... but by 1931 the French

economy was slipping into the Depression as well. The next few

years would be extremely tough for France economically.

The Popular Front

By 1934 France was being shaken by political revolts ... especially

after the revelation of the Stavinsky scandal in which a number of

Leftist cabinet members were found to have been involved in the massive

purchase of worthless bonds. In February of that year a massive

protest over this scandal by Paris mobs – which many thought was the

prelude to an attempt at a right-wing political coup – had to be

dispersed by the force of arms. Order was restored to France.

However, over 200 had been killed and over two thousand badly wounded

in the riot.

Consequently, Leftist suspicions of on-going Fascist plots – plus

similar Right-wing suspicions of Communist plots to take over France –

split the country into two political groupings whose hostility toward

each other grew ever deeper ... literally immobilizing French politics

at the center. By 1935, an originally veterans organization, the

Croix de Feu, had grown into a para-military organization of some

300,000 ... with characteristics similar to the Fascist organizations

of Italy and Germany, giving signs of a readiness to take over the

French government by storm (in the manner that Hitler had just done in

Germany).

After the left-wing Socialists split from the more centrist Socialists

to form the Communist Party, the more centrist Socialists decided

to enter into various governing coalitions with the French Radicals

(also largely centrists), coalitions which came to be termed the

"Popular Front" Also, as Stalin eventually became more concerned

about the dangers of Hitler than the dangers of Western capitalism and

bourgeois democracy, the Popular Front came to include the

participation of the French Communists. In the 1936 elections the

French fear of fascism was substantial enough to give the Popular Front

a clear majority in Parliament and thus a Popular Front government

under Léon Blum was formed (the Right received only a little over a

third of the vote).

This was an extremely difficult time for Blum to be given the

responsibility of leading the nation. Employment levels in France

were so low that only about a half of the French workers were employed

full time. Unemployment payments by the government had again

nearly completely drained the French treasury of its gold

reserves. And workers’ strikes were breaking out all over the

country. Blum responded with legislation mandating the 40-hour

work week, paid vacations, and collective bargaining ... which greatly

settled the mood of the French industrial workers. Likewise for

the French farmer prices were set by government so as to set the price

of the industry’s all-important wheat crop. And a number of

industries (such as the armaments industry) were nationalized ... or at

least brought under strict government regulation.

Unfortunately for the French economy these measures only ignited a huge

French price inflation of all these regulated goods. Wheat prices

were higher ... therefore so was the price of bread for the average

Frenchman. Shortening the industrial work week forced

industrialists to have to raise prices in order to draw any profit for

their operations, which made French products less competitive on the

open international market. Consequently this French ‘New Deal’

failed to solve the problem of widespread unemployment, industrial

bankruptcy and the devaluation of the franc. Worse, it crippled

the French armaments industry ... at a time that Germany was rapidly

rearming under Hitler’s direction.

Then besides the Left-Right deadlock over the basic political path the

country should take in terms of domestic policy, the evolution of the

larger world of European politics during the 1930s made French national

politics even more difficult. The French could not decide which

rising power to the East, Nazi Germany or Communist Russia, posed the

greater danger to Western, or at least French, civilization.

Along with this went wide disagreement on how to respond to Mussolini

in Ethiopia and the civil war raging next door in Spain

Ultimately the poor economy, and Blum's decision not to support the

leftist Republicanists in the Spanish Civil War, caused the defection

of the Communists – and the collapse of his government in 1937 ...

though so shaky was the situation that he was returned to office in

1938 ... briefly. Then the centrist Radicals took control under Édouard

Daladier and Blum’s Socialists were dropped from the cabinet. But

Daladier also had a very difficult time navigating France through the

tough times of unemployment, the impact on the economy of the shortened

workweek, a growing government deficit ... and a drop in French arms

manufacture. In 1938 measures were taken to allow the armaments

factories to stay open six days of the week (in the hopes of answering

the growing German threat) ... but this would prove to be too little

too late. |

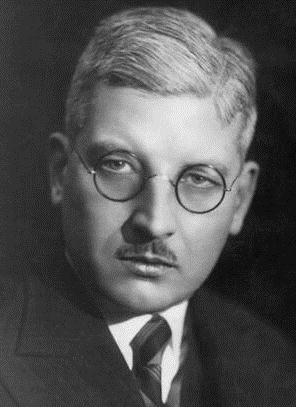

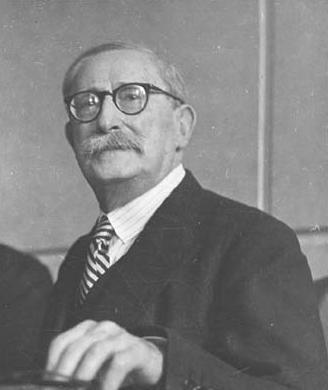

Léon Blum - leader of the French SFIO (French Section of the Workers' International) and one of France's prime ministers during the French leftist

"Popular Front" of 1936-1938

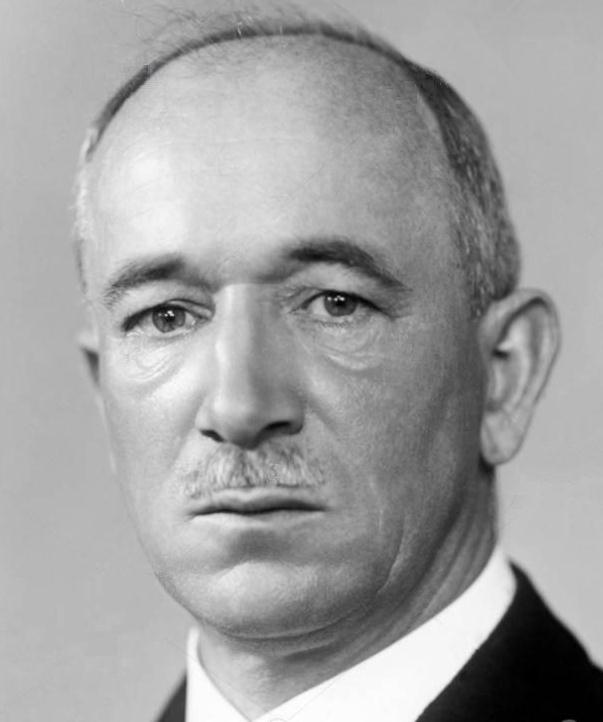

Édouard Daladier ... head of the French Radicals (not so "radical" really!) and French Prime Minister

after the fall of the Popular Front in 1938

Then

with the economic crisis of the early 1930s the confusion worsened ...

with a rising group of Austrian Fascists pressing for union (Anschluss) with

Hitler’s Nazi Germany ... and with both the Christian Socialists and

the Social Democrats fervently opposed. Englebert Dollfuss served

as the head of the Christian Social Party and became head of a

coalition government in 1932 - but with such a slim majority that it

made his position very shaky. Voting irregularities in the

following year caused the coalition to collapse. But Dollfuss

convinced the Austrian President, Miklas, to let him rule without

parliament - as virtual dictator - pointing out the threat of a German

Nazi takeover of Austria as the alternative (the Nazis were gaining

popularity rapidly in Austria at this time).

However in 1934, Dollfuss was assassinated in an attempted German Nazi

takeover of Austria, the "July Putsch." His assassins were

arrested and the coup was thus thwarted.

Dr. Kurt von Schuschnigg took over the office of Chancellor after

Dolfuss's assassination and in 1935 was able to disband the Heimwehr, a

paramilitary group similar to the Nazis, in an effort to get Austria

settled down. But Schuschnigg was ultimately unable to hold back

the rising Nazi spirit demanding the Anschluss with Hitler’s

Germany. Thus heading into the latter 1930s, Austria was facing a

crisis it could not seem to overcome.

|

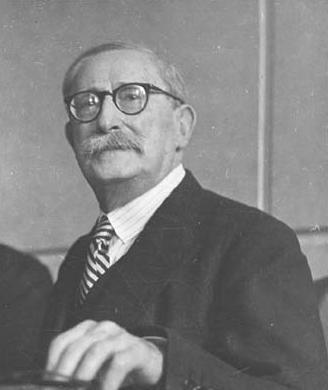

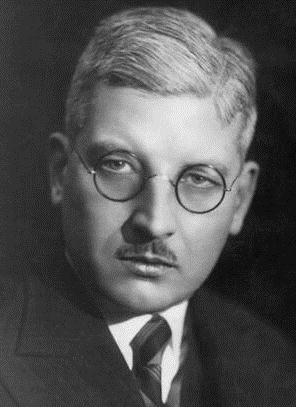

Engelbert Dollfuss - Chancellor

(then dictator) of Austria (1932-1934)

Verlag Christian Brandstätter,

Vienna

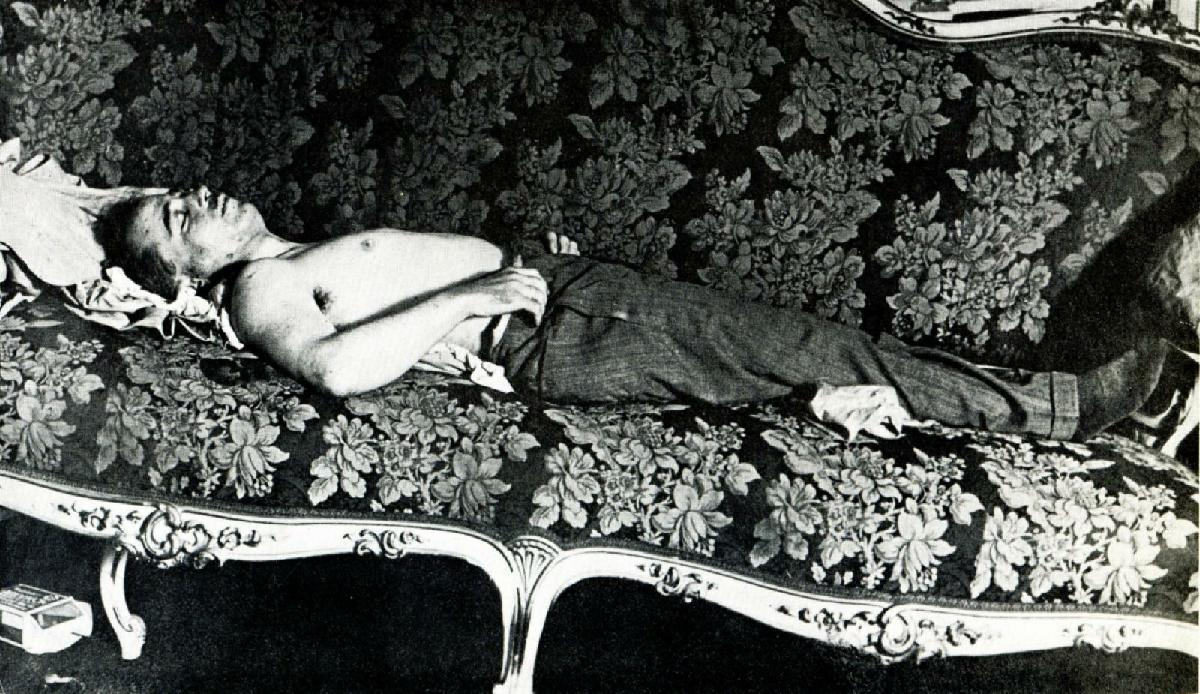

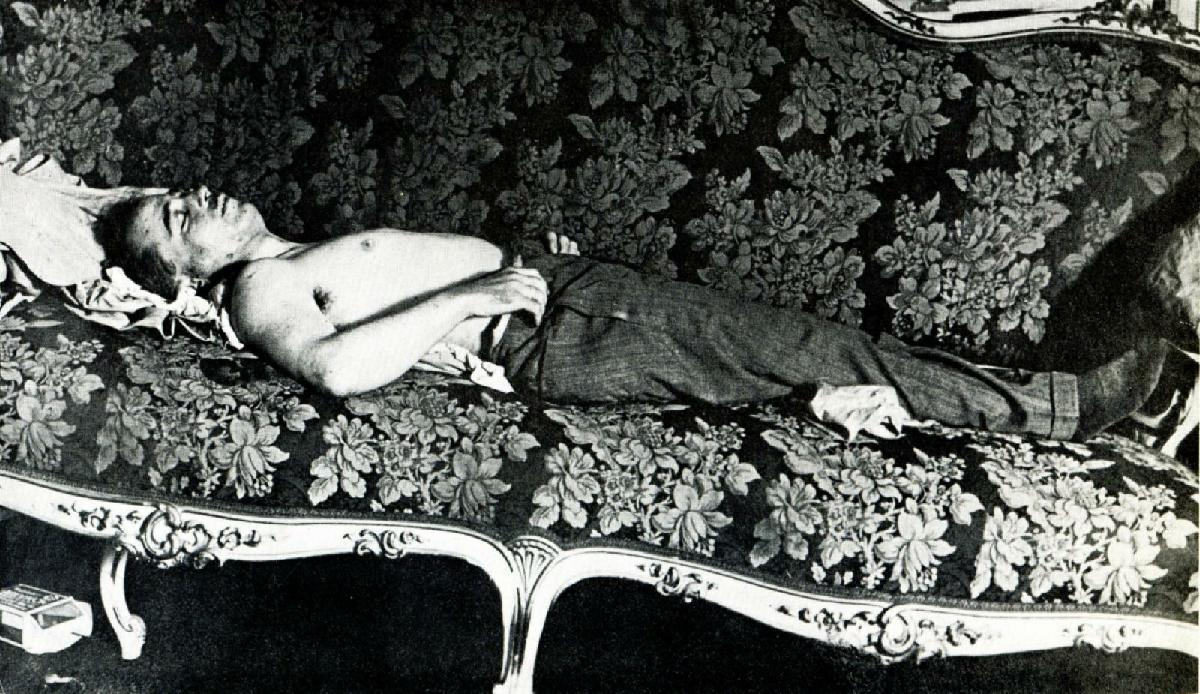

Austrian Chancellor Engelbert

Dollfuss, who bled to death in his Vienna office, assassinated by Nazis in

a (failed) attempt to overthrow the Austrian government - July 25, 1934.

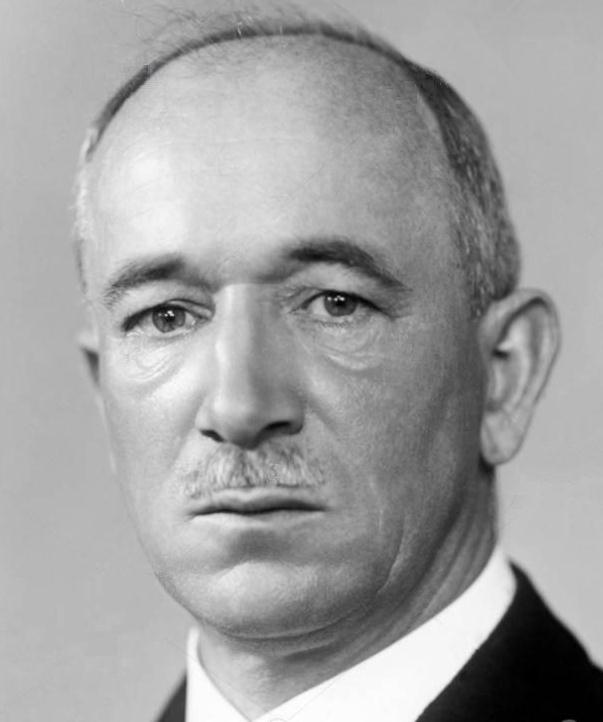

Kurt Schuschnigg - Chancellor

of Austria (1934 - 1938). He attempted to hold off a Nazi grab of Austria ... and called for a national plebiscite to let the Austrians choose for themselves their destiny. But just two days before the scheduled plebiscite Hitler threatened Schuschnigg ... who then resigned (March 12, 1938).

THE NEW REPUBLIC OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA |

| But

as with the rest of Europe, the Depression hit the country hard.

Friendly relations that once united the cultural subgroups making up

the Republic began to turn sour. The Slovaks and the Hungarians

of the Ruthenian district in fact became increasingly bitter about the

Czech domination within the Republic. And the Germans in the

Sudetenland began to take a louder interest in an escape from Czech

domination and an embrace of unity with Hitler’s Germany. Hitler

would eventually play this complaint to great personal and national

advantage.

|

Edvard Beneš - Czech President

GERMANY, ITALY AND JAPAN MOVE INTO A CLOSER RELATIONSHIP |

Italy and Germany signed a treaty of Friendship on October 25, 1936. Mussolini would term this the "Axis Pact" ... referring to a central line of European power running from Berlin to Rome

A month later, on November

25th, Germany and Japan signed an Anti-Cominten Pact directed against

Stalin's Communist expansion ... but also recognizing formally Japan's takeover of Manchukuo in Northern China. A year later Italy would

join the Pact.

Go on to the next section: Stalin's Soviet Russia

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| |

Britain and the Great Depression

Britain and the Great Depression

The new Republic of Czechoslovakia

The new Republic of Czechoslovakia

Germany, Italy and Japan move into a

Germany, Italy and Japan move into a