|

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm,

Germany, in early 1879. The following year his family moved to Munich

where his father, Hermann, and uncle, Jacob Einstein, established a small

electical engineering operation.

Early Life

Einstein showed no particular aptitude

for formal schooling and was thought by his teachers to be a slow learner.

But he had a strong curiosity about the doings of his father's engineering

works--and his uncle Jacob was careful to teach young Albert some of the

mathematical principles involved in the workings of the electrical dynamos.

At the same time a maternal uncle, Caesar Koch, taught him basic principles

of science.

Problems in his father's company

forced the family to leave Germany--to settle in Milan, Italy. Albert

was sent back to school, this time in Switzerland. Eventually he

found his stride and in 1900 successfully completed a four-year course

of study at the Federal Polytechnique Academy in Zurich. Soon thereafter

he became a Swiss citizen and took a position in the Swiss Patent Office

in Bern.

In 1903 he married a classmate from

the Academy, Mileva Maric.

Special

Relativity: 1905 Special

Relativity: 1905

In 1905 Einstein entered for publication

in the monthly journal, Annalen der Physik, a number of articles

relating molecular action to heat, light, and body mass. These were

the foundational pieces for his Special Theory of Relativity. Immediately

the genius in these works was recognized, and University of Zurich awarded

him the Ph.D. for his work.

Einstein left his work at the Patent

Office and took up teaching, eventually becoming a full professor at the

University of Prague. Then in 1912 he returned to Switzerland to

a teaching position at the Federal Polytechnique in Zurich.

World War One: Family Turmoil

The years leading up to World War One

(1914) were a time of great contentment for Einstein, his wife and his

two sons, Hans Albert and Edward.

But World War One intervened to upset

this serene picture. In the spring of 1914 the family moved to Berlin

where Einstein had accepted a position at the University of Berlin.

That summer his wife and sons left on vacation for Switzerland, but when

the war broke out in September, they were unable to return to Berlin.

The physical separation eventually evolved into an emotional separation--and

Einstein and his wife divorced.

The growing tragedy of the war led

Einstein to an ever more vocal pacifist position--which put Einstein quite

out of step with his very nationalistic, even militaristic, professorial

colleagues. Einstein was appalled by the ability of the supposedly

highly civilized European nations to rationalize the massive murderousness

of the war effort.

General

Relativity: 1916 General

Relativity: 1916

Nonetheless Einstein's work on a pet

project of his had been making headway and in 1916 he published an article

in Annalen der Physik entitled "The Foundation of the General Theory

of Relativity." Here he laid out the basic principles for a theory

that united a number of his special laws of relativity into a single General

Theory of Relativity.

In late 1918, with the end of the

"Great War," as World War One was then called, Einstein looked forward

to the rule of peace and reason within the West, and in Germany in particular.

In 1919, with a solar eclipse that

validated his theories about the action of light as it passed close to

a massive body, Einstein's fame became truly international in its extent.

A Growing Personal and Social Life

In that same year, 1919, he remarried--taking

for his wife his own widowed second cousin, Elsa, and fashioning a new

home with her and her two daughters.

Berlin in those days was a scene

of emotional-political turmoil, vented on the Communists and Jews who,

according to German ultra-nationalists, were supposedly conspiring to take

over the German nation. This was the beginning of very hard times

for Jews in Germany. It was at this time that Einstein, though a

religious agnostic, began to focus more on his own cultural Jewishness--by

taking up the Zionist cause. He even came to the United States in

1921 to raise money for the Palestine Foundation Fund, used to resettle

Jews in British-controlled Palestine (modern-day Israel).

Needless to say, he was much sought-after

as a lecturer on his new theories of physics and he found himself travelling

much over the next years, lecturing in Europe, America, and Asia.

In 1921 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics.

His

Quest for a Theory of Everything His

Quest for a Theory of Everything

Einstein was now focusing his thoughts

on the matter of how a simple principle stood behind the workings of the

whole universe. He was looking for a unified field theory--a theory

of "everything."

Unfortunately, the discovery of quantum

physicists (Bohr, Heisenberg and others) that there was a built-in indeterminacy

or uncertainty about the behavior of the fundamental particles of matter

(quanta) made Einstein's study of "everything" problematic at its

its very heart. Einstein himself refused to accept the uncertainty

principle as a final statement about the behavior of the universe's fundamental

material--and continued to look for a theory that could side-step this

uncertainty.

He

Leaves Germany for America He

Leaves Germany for America

In the meantime the very hard times

of the late 1920s and early 1930s touched even Einstein. The Zionist

program to resettle Jews in Palestine was getting unyielding oppostion

from the British authorities in Palestine--and violent opposition from

the Arabs living there. And in Germany, Hitler's Nazis were gaining

popularity by bashing Jews as national demons (along with international

capitalists, Communists, Socialists, Gypsies, homosexuals and a few other

categories of "undesireables"). Einstein's hope was also sinking

quickly that a new international legal order, embodied in the League of

Nations, would bring peace to the world. Increasingly the League

was proving itself unable to deal with the growing number of diplomatic

crises afflicting the world. Einstein grew bitter in his disappointment

over this failure.

In 1933, with Hitler's appointment

as Chancellor of Germany, Einstein renounced his German citizenship and

left the country. His mood now changed from one of pacifism to adamant

opposition to the Nazi regime, even calling on Europe to arm itself against

Hitler.

He

soon thereafter (October 1933) came to Princeton, New Jersey, to become

part of the faculty of the new graduate Institute for Advanced Study.

Here he lived quietly and routinely with his wife (until her death in 1936)--rarely

leaving Princeton over the years. Eventually he became an American citizen. He

soon thereafter (October 1933) came to Princeton, New Jersey, to become

part of the faculty of the new graduate Institute for Advanced Study.

Here he lived quietly and routinely with his wife (until her death in 1936)--rarely

leaving Princeton over the years. Eventually he became an American citizen.

World War Two and the Bomb

As war clouds gathered in Europe (1939)

Einstein was informed by his friend Niels Bohr that in accordance with

Einstein's theories, the uranium atom had been split, giving off a small

amount of its mass in the form of energy. This pointed to the thought

that this process could be--and most probably would be--controlled to produce

a bomb of catastrophic proportions. The question was--who would be

the first to achieve this goal: Germany or its enemies? Einstein

himself decided to write President Roosevelt to make him aware of the critical

challenge that nuclear power posed--and the need to develop atomic weaponry

before the Germans did. Thus was born the idea of the Manhattan Project.

Einstein

himself was not part of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico,

where America's atomic bombs were developed during the war years.

Nonetheless his own hand in developing the theoretical foundations underpinning

the nuclear age was quite evident to everyone. However, at war's

end, the pacifist in Einstein now reasserted himself, and Einstein's thoughts

now ran to the question of securing a world free from the terror of nuclear

arms--rather than to the challenge of staying ahead in the nuclear arms

race. Einstein

himself was not part of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, New Mexico,

where America's atomic bombs were developed during the war years.

Nonetheless his own hand in developing the theoretical foundations underpinning

the nuclear age was quite evident to everyone. However, at war's

end, the pacifist in Einstein now reasserted himself, and Einstein's thoughts

now ran to the question of securing a world free from the terror of nuclear

arms--rather than to the challenge of staying ahead in the nuclear arms

race.

Einstein Moves to the Sidelines

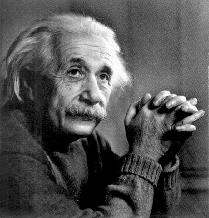

In his later years he remained focused

on the quest for a unified field theory. In 1950 Einstein published

a paper on the subject. But most physicists remained unconvinced

that his theories, though carefully worked out mathematically, were valid.

And this growing sense of separation

from the mainstream of physics and mathematics remained with Einstein all

the way to his death in Princeton in April of 1955. |

Go

to the history section: The Emerging Realm of Quantum Mechanics

Go

to the history section: The Emerging Realm of Quantum Mechanics

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges