23. THE TROUBLED 1970s

A "MORE MORAL" CARTER

CONTENTS

The American Bicentennial – 1976 The American Bicentennial – 1976

Jimmy Carter and the national elections Jimmy Carter and the national elections

of 1976

Carter proposes a foreign policy of Carter proposes a foreign policy of

"Morality"

The surrender of the Panama Canal The surrender of the Panama Canal

The fall of the Shah of Iran The fall of the Shah of Iran

Other international issues during the Other international issues during the

Carter years

American diplomats imprisoned in Iran American diplomats imprisoned in Iran

Drooping American morale Drooping American morale

Volcker's "monetarism" to the rescue? Volcker's "monetarism" to the rescue?

Other political causes continue to Other political causes continue to

advance themselves in America

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 238-252.

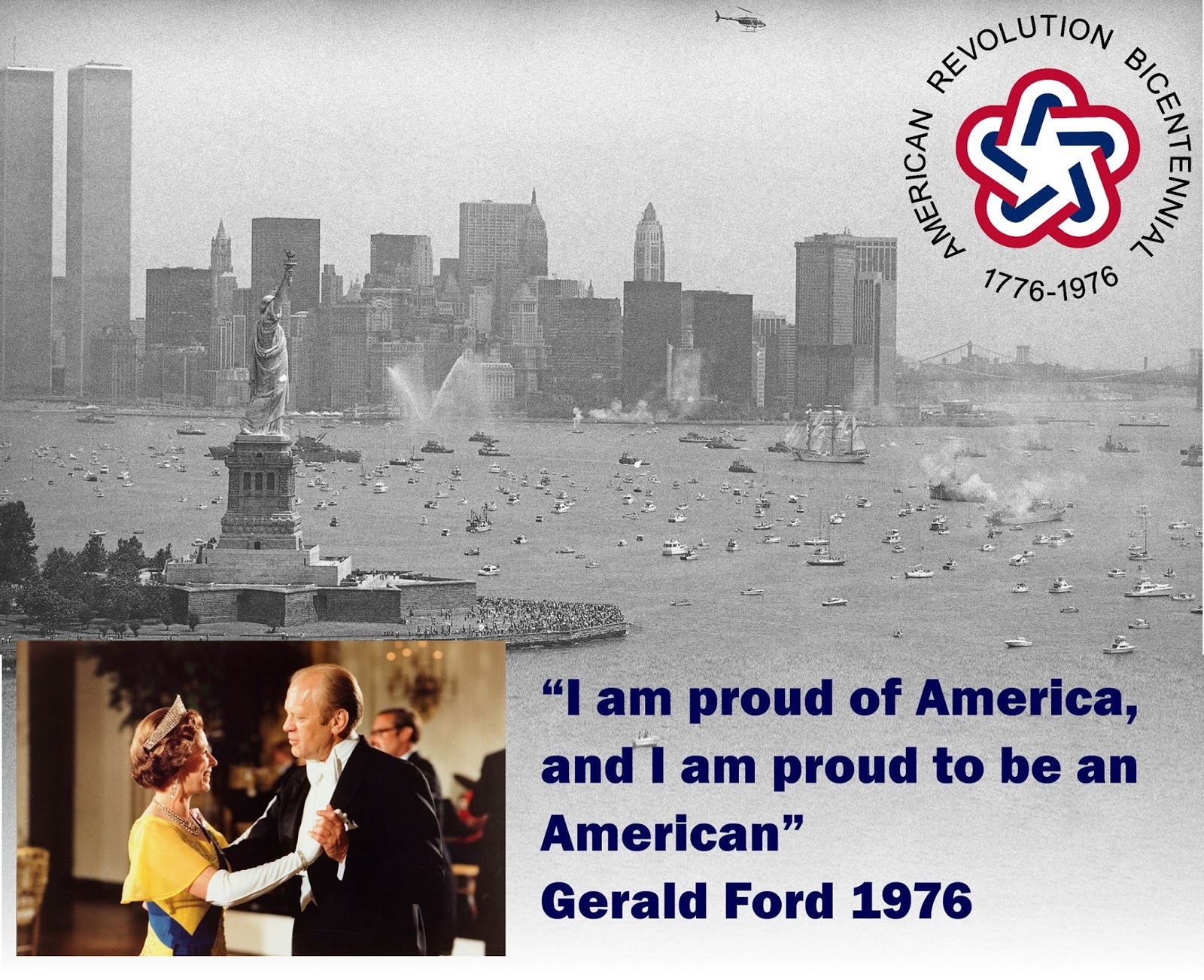

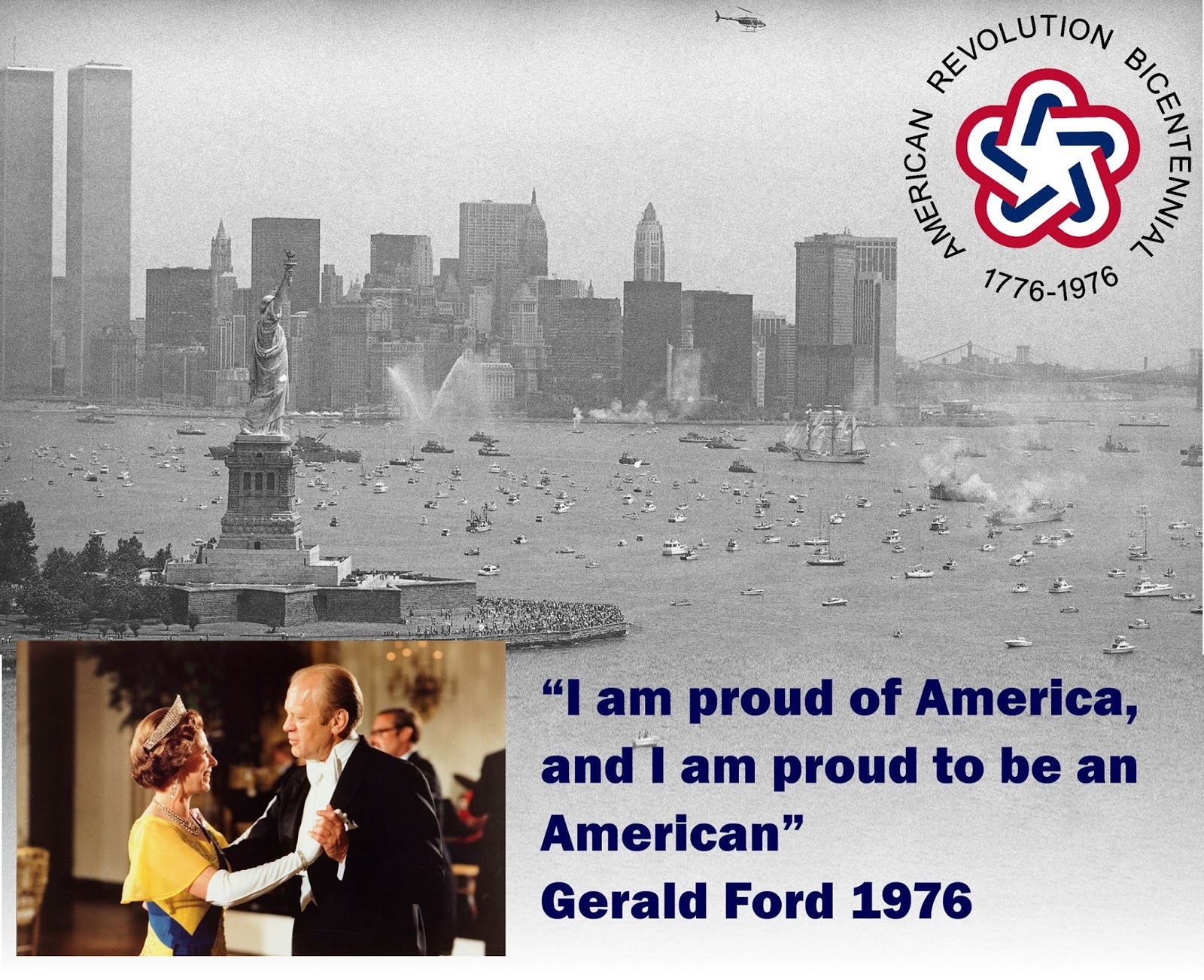

THE AMERICAN BI-CENTENNIAL – 1976 |

|

1976 was the year of the Bicentennial, the 200th

anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It

should have been a year of great celebration, of America looking back

over the past two centuries to see proudly how well the country had

done. But this was not to be. At the moment America was not feeling

very proud. Supposedly democracy had been restored. But somehow

something felt very wrong. America had lost its sense of direction, its

sense of purpose. America was on the defensive, in retreat, without any

sense of when that retreat might stop. This silent understanding was

quite evident in the lackluster bicentennial celebrations.

|

JIMMY CARTER

AND THE NATIONAL ELECTIONS OF 1976 |

|

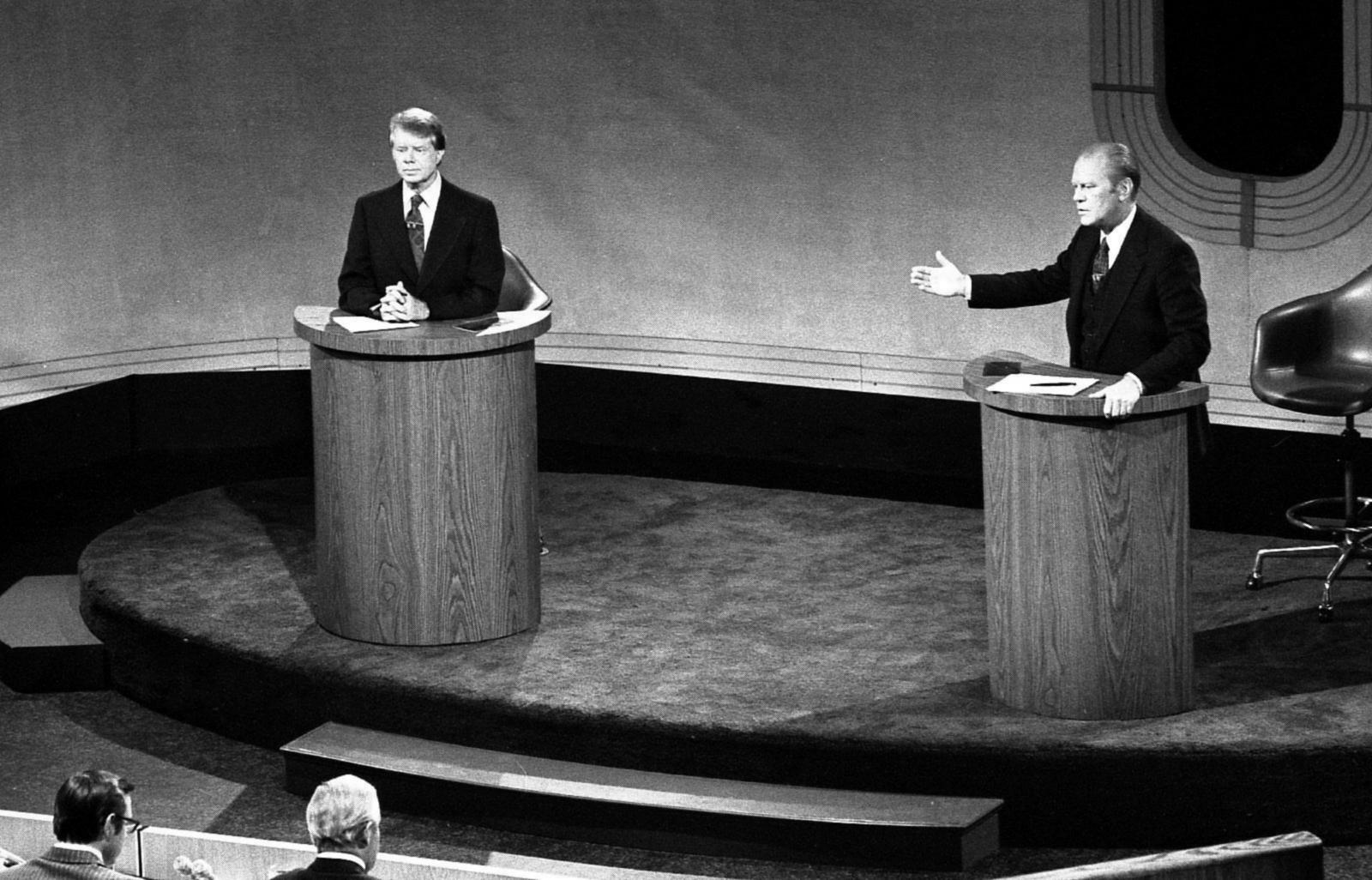

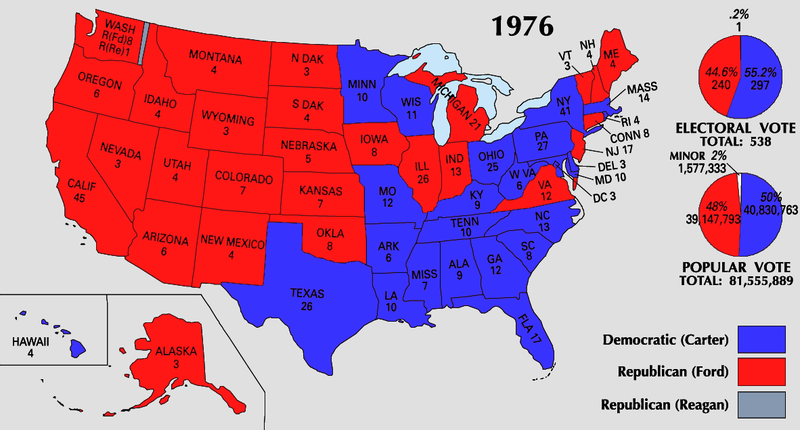

1976 was also an election year for the White

House. The Republicans had swung their support behind Ford and

nominated him as their candidate for the presidency. But the Democrats

had no strong front-runners among the pack of people that could have

been considered potential candidates for the presidential nomination.

Ted Kennedy would have been the logical choice, given the Democratic

Party's love of the name Kennedy. But Ted had the albatross of

"Chappaquiddick" hanging around his neck and he knew that to run he

would have to face that issue again. None of the Democrats wanted that

tragic (and embarrassing) event brought back up for closer inspection.

The Democrats ultimately chose a

virtually unknown one-term governor (1971-1975) from Georgia as their

presidential nominee. The press was totally fascinated with this

seemingly humble peanut farmer (but also ex-Navy man) from Georgia, and

in short order (from late January to mid-March of 1976) from a virtual

nobody he was refashioned into the image of an amazing political genius

by the press. Since so little was known about him, he had only a local

political record to draw from, there was no way to fault this image. In

the space of that small time-period Carter pulled smartly ahead of all

other contenders, and ultimately received the Democratic Party

nomination.1

1It

could also be that it served Ted Kennedy's political ambitions to have

someone in the White House who had no political foundations of his own

to stand on – leaving the way clear for Kennedy to continue to direct

American democracy from his seat in the Senate.

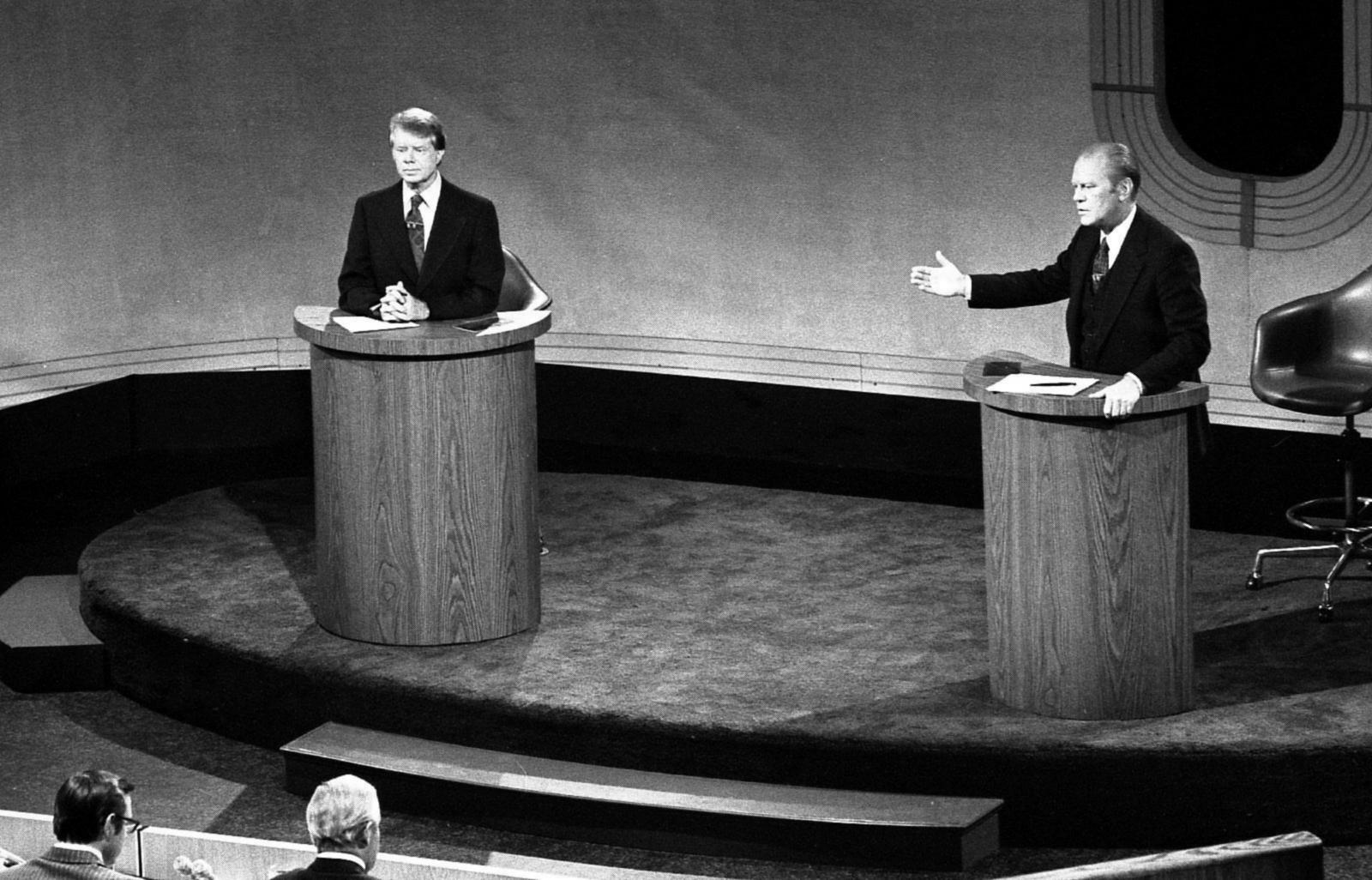

Governor Jimmy Carter

and President Gerald Ford debating

at the Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia – September 23, 1976

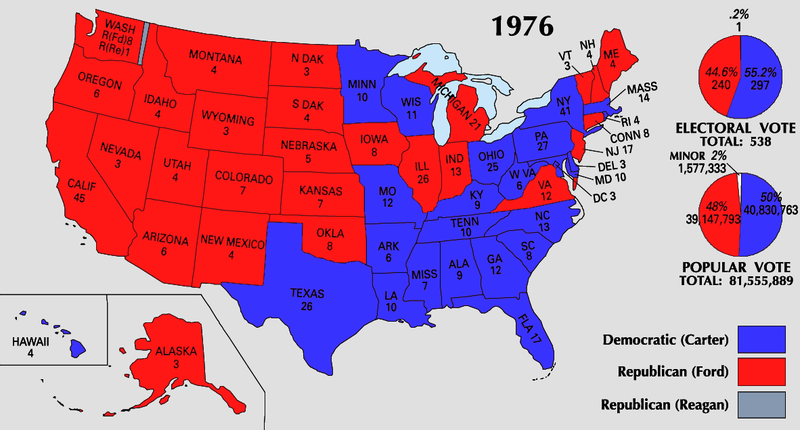

The 1976 Presidential Elections

Carter setting the stage

for his more "down-home" administration

by walking to his inauguration

ceremonies – 1977

Carter taking the oath of office Carter taking the oath of office

Jimmy Carter – President

1977-1981

Jimmy Carter – President

1977-1981

CARTER PROPOSES A FOREIGN POLICY OF "MORALITY" |

In his public debates as the Democratic

nominee, Carter attacked the content and style of the foreign policy of

the Republicans, claiming that with its "secret diplomacy" (such as had

taken place in Nixon's early diplomatic initiatives with the Chinese

and the Russians) it excluded the American people and Congress from

their participation in the shaping of a more democratic American

foreign policy. He attacked America's support of foreign dictators, its

huge involvement in arms sales, and its ignoring of human rights

abroad. The Cold War was over (or so Carter claimed) and it was clear

that America had no further reason to follow the reactive diplomacy of

that era. Thus he made it particularly clear that he strongly opposed

the amoral philosophy of Realpolitik

practiced during the previous eight Republican White House years. He

lauded the high Idealism and moral character of America's traditional

or democratic foreign policy (such as Wilson's or Johnson's?) – and

repeatedly announced the idea that he was going to restore that

high-mindedness in American foreign policy. Among other new policies

that would happen under his presidency, America would no longer support

dictators simply because it was in some Realpolitik understanding of

the "national interest." In particular he put both Iran and South Korea

on notice that they must liberalize their governments, or lose American

support.

This seemed to impress the American voter

sufficiently so that Carter was able to defeat Ford (50.1 to 48.0

percent) and enter the White House in January of 1977, ready to send

America off in a new moral direction.

But very quickly Carter was shown the dangers

of cutting back on American troops in South Korea – as he had proposed

during the campaign (and even NATO troops in Europe as well). Both the

military and Congress were quick to point out the terrible dangers of

undercutting our South Korean ally. So Realpolitik won that issue.

However, he was able to demonstrate some

"moral" movement toward a better world in other foreign policy areas.

He was quick to amplify the opening to China started by Nixon and to

sign with the Soviets a second round of arms limitation treaties (also

started by Nixon) as part of his peace-through-morality crusade.

Likewise, he was able to host a bold effort at

getting a breakthrough in Israeli-Arab relations, bringing into play

the very political "linkage" (horse-trading) that Carter had once

condemned in Nixon's (and Kissinger's) Realpolitik – but which Carter

eventually began to find to be fully acceptable: full diplomatic

recognition of Israel by Egypt as payment for the return of Egyptian

lands seized in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. So it was that finally

Realpolitik helped Carter win on that issue as well. Nonetheless, all

of these were indeed authentic Carter achievements.

|

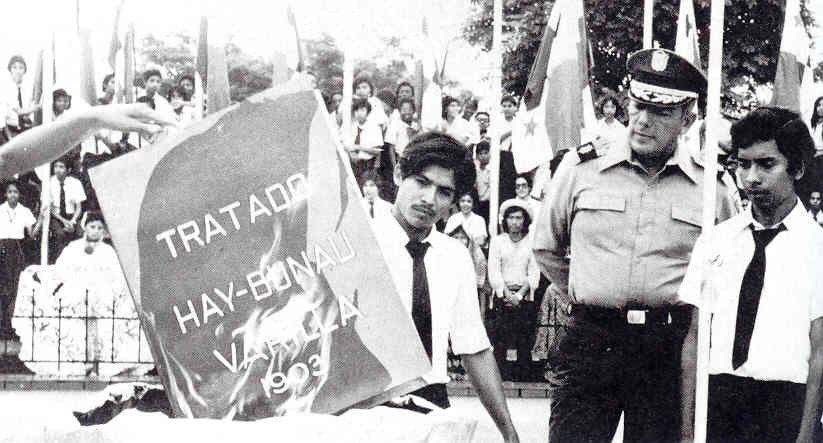

THE SURRENDER OF THE PANAMA CANAL |

|

But an early action of Carter's (September 1977)

would defy all explanations: Idealist or Realist. Carter decided to

"give back" the Panama Canal to Panama – a country which for $40

million in 1903 had turned control of the canal zone over to America so

that America could, at its own expense, build a canal there. Title to

such a valuable piece of property was extended to America in perpetuity

– but with the promise of an annual payment to the new Panamanian

government that Teddy Roosevelt had just helped set up three days

before the canal deal!

Now here was Carter turning the canal

over (by various stages of surrender, to be completed on the last day

of 1999) to a Panamanian military dictator, General Omar Torrijos – who

held power in Panama by military force since his takeover in 1968.

Where were Carter's scruples about not dealing with dictators? And what

was it that he was hoping to gain by giving up a vital American asset

that had taken ten years, millions (now equivalent to billions) of

dollars and thousands of lives to build?

If he thought he was gaining goodwill

among his Latin neighbors to the South, certainly they were glad to see

America retreating from its position of dominance in the area.

But this did not increase their respect, nor even their love, for

America. Why did Carter do it? Certainly also, the Panamanians

themselves wanted to own such a valuable asset – and had long desired

this. And why not? But why now? What was Carter hoping to

gain from this?

Anyway, Americans did not know how to

react to all this. None of Carter's "achievements" seemed at the time

to be of terribly earth-shaking importance or of any notable national

gain to a bleary-eyed America that found greater satisfaction in

watching a U.S. hockey win over the Russians in the February 1980

Winter Olympics held at Lake Placid (New York) in February, or a sense

of moral or spiritual strengthening in watching the movie Rocky (1976) and a Rocky II sequel (1979).

There was not much else to go on that

allowed Americans to feel any pride in their country. In fact, in the

last years of Carter's one and only term in office, America found

itself spiritually in terrible, terrible shape.

|

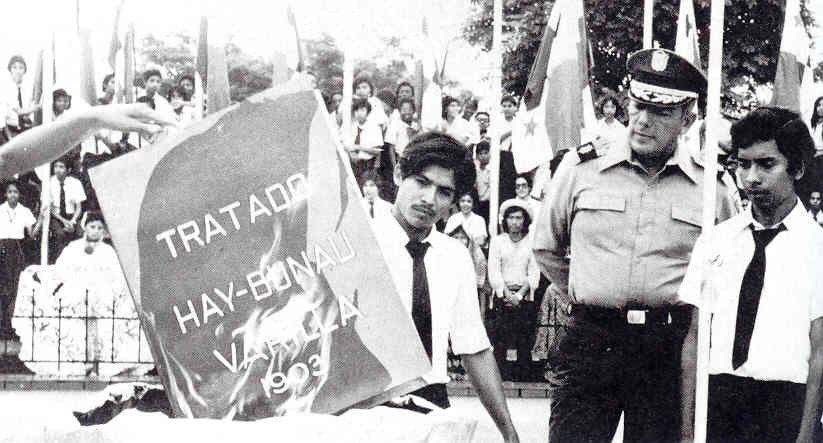

As a first act to reduce

the image of American "imperialism" Carter decides to

surrender the Panama Canal to Panama

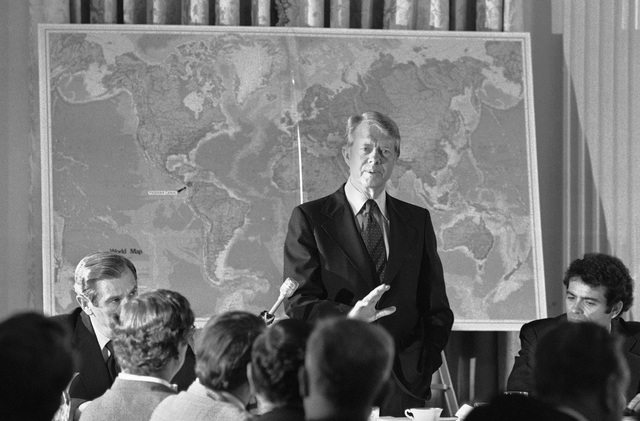

Carter explaining to

representatives of Georgia and Florida his proposed new treaty

to turn the Panama

Canal over to Panama – August 1977

September 1977 – Jimmy Carter

agreeing with Panama's President Omar Torrijos to surrender the Panama Canal over to

Panama –

a sign of our ending the era of American imperialism

Symbolic burning of the 1903

Panama treaty – with Panamanian President Omar Torrijos looking

on

THE FALL OF THE SHAH OF IRAN |

|

Carter: From Idealism to Realism in Iran

Carter's policy toward a key ally in the Middle East, Iran, turned out

to be much more complex – and ultimately a terrible failure. Part of

the problem was that Carter failed to follow a consistent policy on

Iran.

At first Carter took a strong stance with

respect to his warning to Iran's Shah (King) Mohammed Reza Pahlavi that

the Shah was going to have to make some serious moves to improve human

rights in his country if he were to continue to receive American

support. The organization Amnesty International reported that there

were some 3,000 people imprisoned in Iran simply for their political

views. Carter wanted that situation improved, and demanded of the Shah

an opening up of Iran to greater democratic participation or America

was no longer going to continue to supply Iran armaments as it had been

doing (one of the things Carter had attacked Ford for supporting).

Carter had in mind improving the lot of Westernized intellectuals (of

which there were many in Iran) who were clamoring for greater political

freedoms.

But Carter soon came to understand (once again) the situation in Realpolitik

terms. Iran was holding in place a very strong pro-American status quo

in the oil-rich and highly dangerous Persian Gulf region. The Soviets

had long put pressure on Iran in the hopes of bringing the country

under its satellite system, which if successful would have allowed

Russia not only direct access to the strategically important Persian

Gulf and the Indian ocean, but would have also put Russia in a position

to shut down the flow of oil to its rivals in the West. Indeed, such

Soviet pressure was already being applied through the opposition of a

number of Iranian intellectuals demanding an end to the Shah's

government. These the Shah had put in prison for wanting to overthrow

his government and replace it with a "democratic republic," much like

what had happened in neighboring Afghanistan.

Sadly however, the Shah had not made any

kind of distinction between those who wanted to overthrow his

government and those who simply wanted to reform it. In any case,

Carter now began to appreciate the pressure that the Shah was under. He

also came to understand that a similar overthrow of the Afghan Shah and

its eventual replacement by a "democratic republic" in Afghanistan had

turned out to be no more than a move of the Russians to set up another

Soviet puppet regime. And because of this Communist takeover in

Afghanistan, the Soviet Russians had advanced ever closer to the dream

of dominating south central Asia, the Persian Gulf and the Indian

Ocean. Carter finally understood the dangers to America and the West of

a failure to support the Shah.

The Shah moves back and forth

Now that Carter was beginning to see the

Iran situation and the Shah from a new perspective, he began to drop

considerably his talk of human rights reforms. Indeed, Carter made

sure, in a huge trip to various European countries (and India) at the

end of 1977, to also include Iran in the event, celebrating New Year's

Eve in Tehran with the Shah, even publicly praising the Shah's Iran as

"an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world."

But by this time the Shah had already

made many concessions to his political opponents, fearing the loss of

American support. Nonetheless, now that Carter was singing a new

pro-Shah tune, the Shah interpreted this as permission to tighten back

up on the Iranian situation. But in the meantime, the brief window of

opportunity for rising expectations to develop that he had given his

opponents helped embolden and organize their opposition.

And when he then backtracked on their liberties, his opponents exploded

in violent protest. Things in Iran began to unstick, though Carter had

such poor intelligence informing him of the internal situation in Iran

that he was unaware of the extent of the Shah's mounting problems.

Could the Shah's government have been

saved at this point? Probably not. Anyway, the problem had been

building for a while. The 1973-1974 quadrupling of oil prices had made

Iran a very rich country. But sudden wealth can be terribly

destabilizing to any political status quo. Saudi Arabia's royal family

(a strong American ally that Carter had also once criticized as being

dictatorial) had seen to it that all Saudis got a good share of the oil

wealth that turned this Arabian desert kingdom into one of the

wealthiest countries (per capita) in the world. But the Shah had not

bothered to do that, merely letting the few families that controlled

the Iranian oil industry take much of that vast new wealth. That was

truly a huge social blunder. Also, heavy financial inflation had hit

Iran no less than elsewhere in the world – hurting deeply multitudes of

Iranians.

Iran's huge farming population lived off

the profits of the farming industry, not the oil industry. The price of

fertilizer and the fuel prices for their trucks and machinery had risen

with the price of oil. But the price for their farm products, pegged to

the world market's food pricing (determined largely by the massive

share of American food products on the world market), had not increased

any at all. Thus Iran's farming population had actually become much

poorer since the onset of the oil bonanza. The farmers who had once

adored their modernizing Shah now felt him to be indifferent to their

plight, and concerned only with the showy wealth of his family and

close friends. They began to see an evil conspiracy in the whole setup.

Likewise, the voices of the farmers were

joined by multitudes of bitter young Iranians from Iran's rising Middle

Class, graduates from engineering colleges in the West (America,

Germany, England, France, etc.), unable to find work back in Iran.

Sadly, the oil extraction business did not really require the

professional services of many engineers. Thus when these young Iranians

returned home and were greeted with the sad news that there were no

jobs in Iran needing their advanced schooling, they too saw some kind

of evil conspiracy as responsible for their plight.

During the days of economic growth and

expansion that touched most every Iranian in the 1960s the Shah was

actually a very popular figure in Iran. The fact that he was

modernizing or Westernizing Iran seemed to be a very good thing to all,

except the Muslim clergy and some of the bazaaris (bazaar shopkeepers)

who resented this Western intrusion into their traditional Muslim

culture. But mostly the latter were ignored as being voices of

"backwardness," and irrelevant to Iran's future.

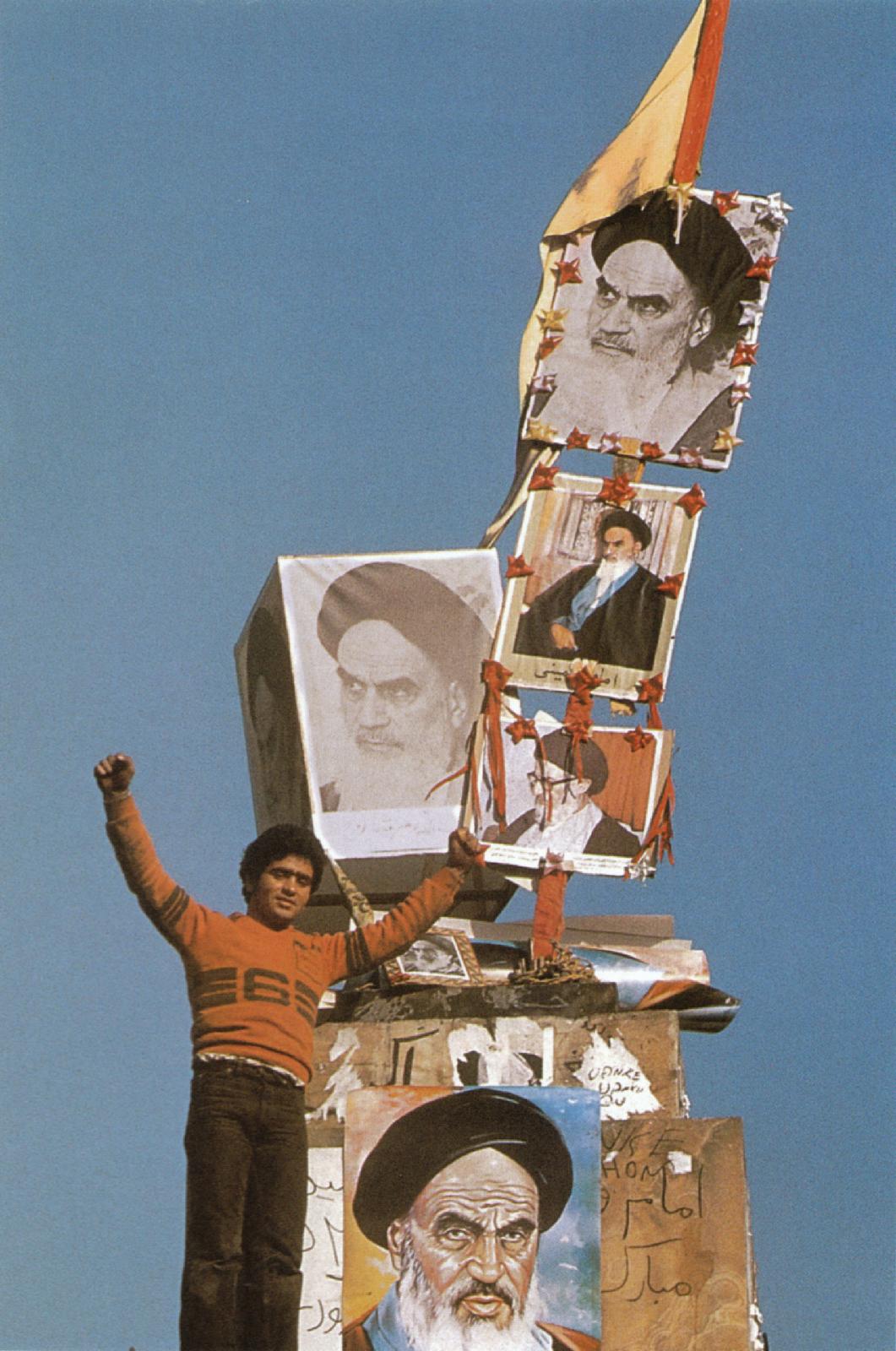

But that assessment of

the Muslim clergy and conservative Muslim faithful would change

considerably in the 1970s. The idea of an "evil conspiracy" fit well

with the Shi'ite Muslim worldview of the great dichotomy in life

between the forces of good and the forces of evil. The Muslim clerics,

led by their ayatollahs, and in particular the Ayatollah Ruhollah

Khomeini in exile in Iraq (and finally Paris), who was sending sermon

cassettes by the thousands back to a growing following in Iran, seemed

to more and more Iranians to make the most sense of an otherwise

desperately confusing situation. God was punishing Iran for having

allowed itself to fall prey to the evil ways of the infidel West, and

in particular to the Great Satan, America

The fall of the Shah's pro-American government

But Carter did not see that last factor

brewing. America had left its intelligence gathering in Iran in the

hands of the Shah's secret police, who had learned long ago not to send

forward any information that might displease the Shah. Thus Carter was

completely blindsided by events brewing in Iran. By the end of the

summer in 1978 strikes were paralyzing Iran, and they only continued to

worsen as the year approached its end.

Finally in mid-January 1979 the Shah went

into exile – and at the beginning of February the Ayatollah Khomeini

returned from Paris to Iran. By mid-February the last of the pro-Shah

forces had been crushed.

Then almost immediately a deep break in

the anti-Shah ranks revealed itself as Khomeini began to move to

undercut a secular "provisional" government, a government supported by

the huge, fully modernized (and rather pro-West) portion of the

population, that had initially taken charge of the country. Immediately

the Muslim crackdown on the voices of liberal dissent got underway.

Iran was not going to become a communist

democracy or even a liberal democracy. It was going to become a

fiercely traditionalist Islamic Republic, a fully Shi'ite society with

an elected government, but one which was ultimately answerable to the

all-powerful religious leaders, the ayatollahs, and in particular to

the Supreme Ruler, the Ayatollah Khomeini. Thus the new

governmental design was put before the Iranian people for

approval. And America, unwittingly (or by careful design by some

Iranians), would help swing Iranian approval for the new Islamic

Republic.

|

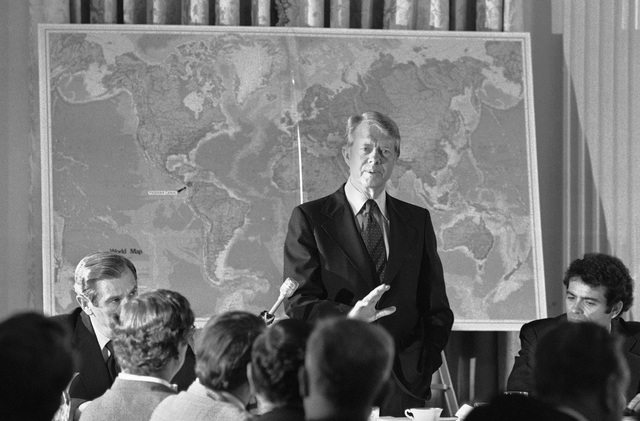

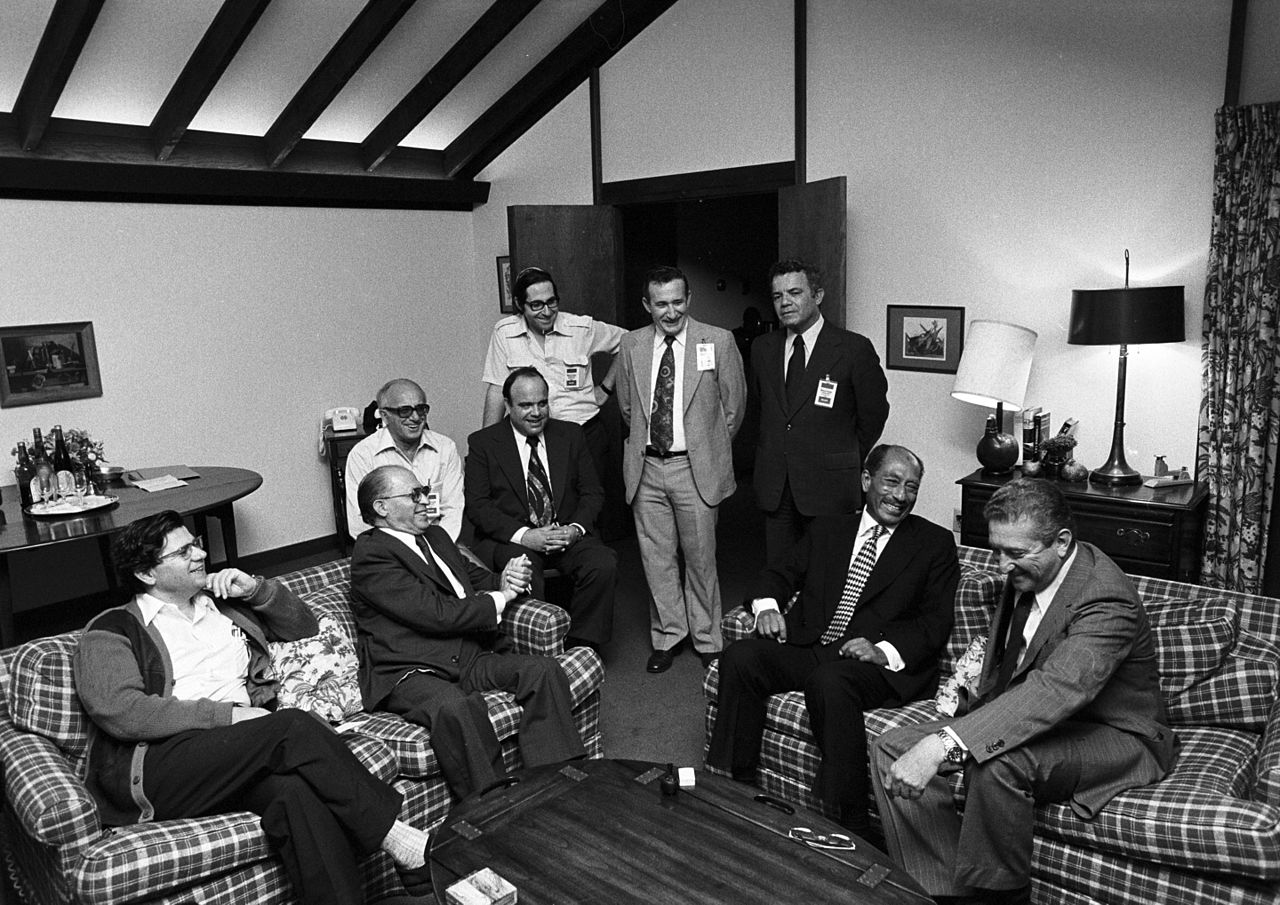

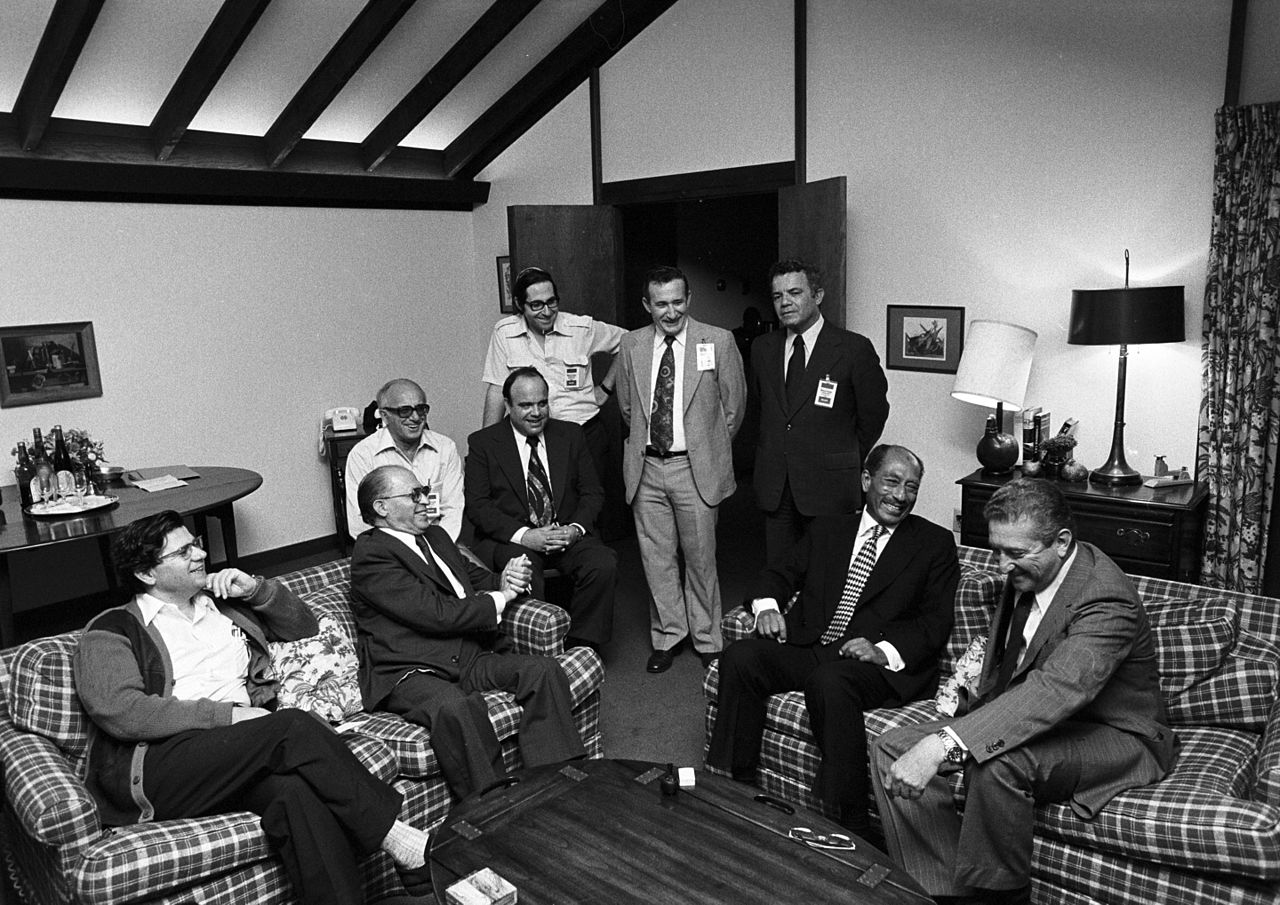

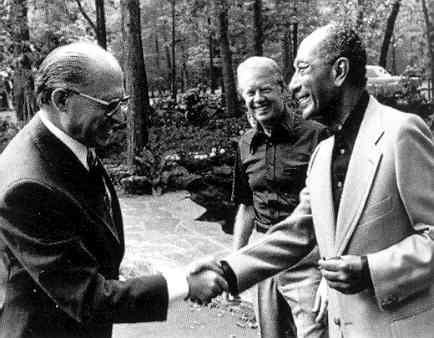

Carter and his cabinet meet

with the Shah of Iran – November 1977

(Carter, 2nd from the right ...

with his secretary of State Cyrus Vance to his right

and his National Security Advisor

Zbigniew Brzezinski to his left ...

discussing with the Shah the political

reforms the Shah must undertake

in order to continue to enjoy American

financial support)

Carter arrives in Tehran in time to celebrate New Year's Eve with the Shah (December 31, 1977)

1978 – Iranian students protesting the

Shah's government

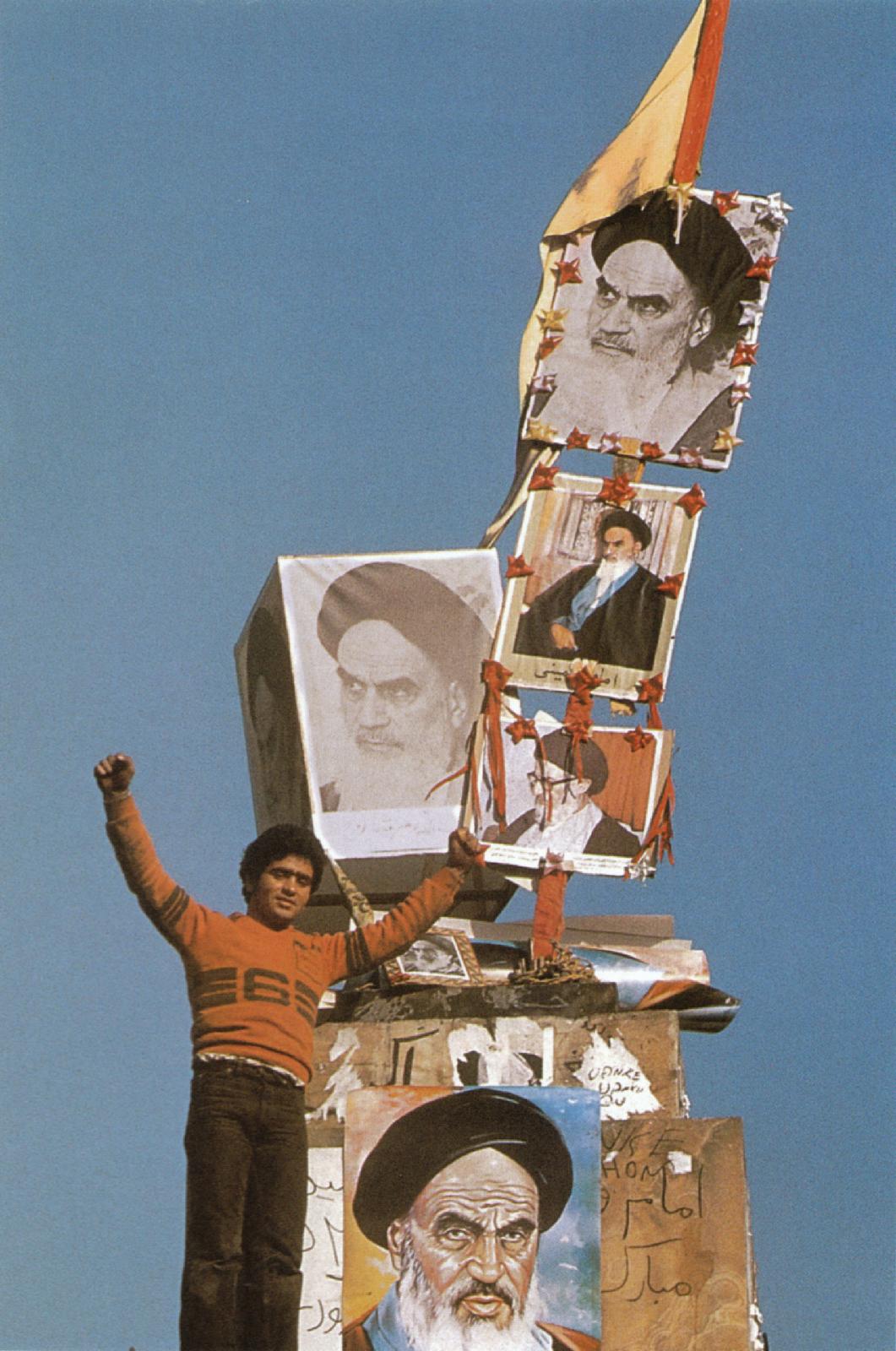

Iranians celebrating in Tehran on

January 17, 1979, after the Shah's departure

Iranian welcome the returning

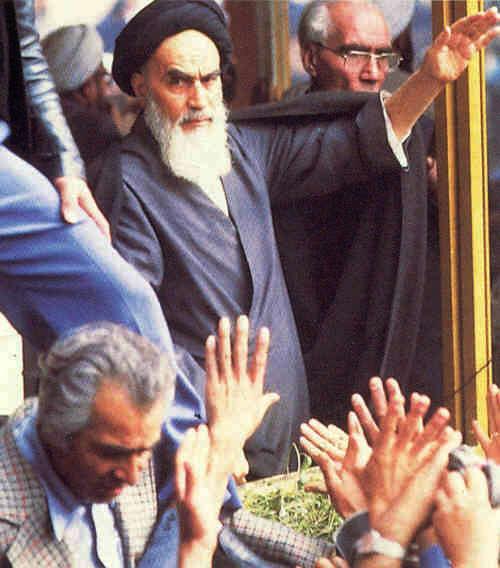

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini – January 1979

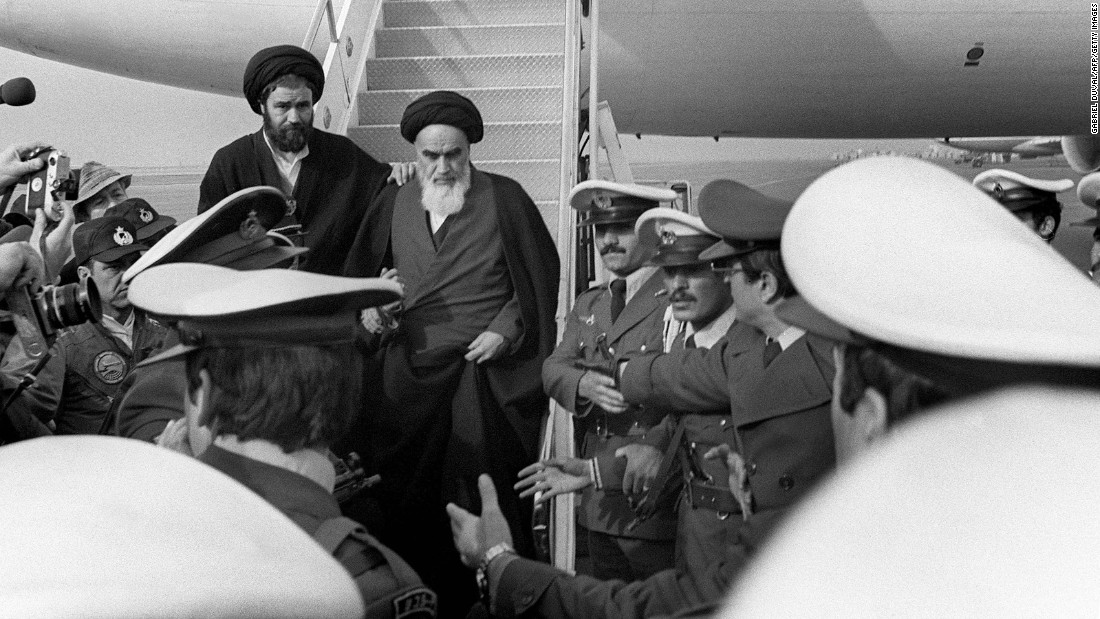

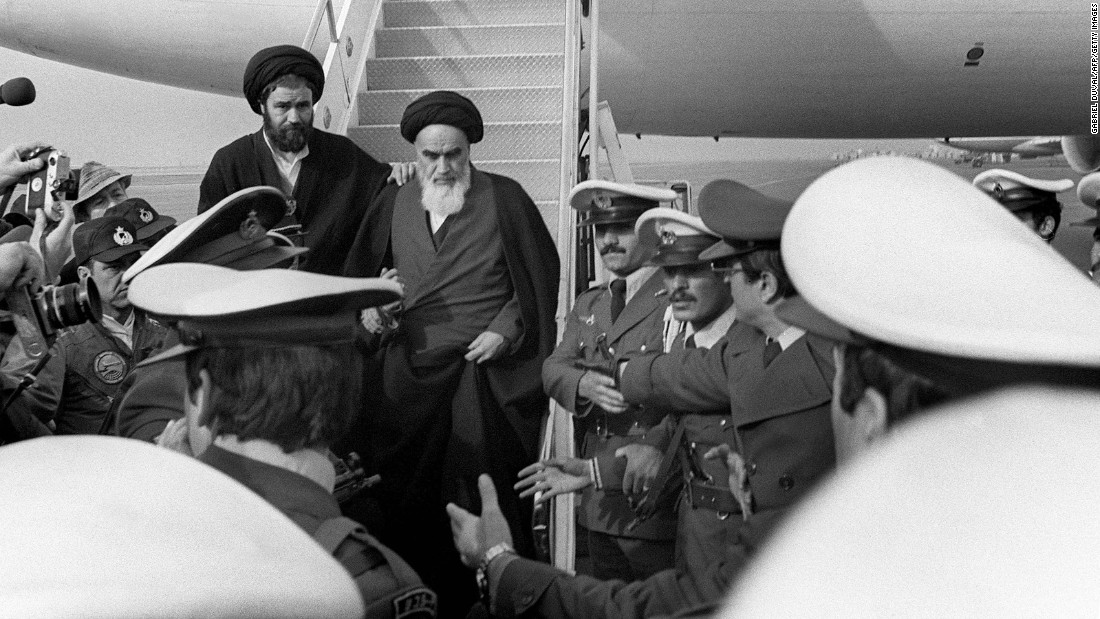

February 1, 1979 – the Ayatollah Khomeini arrives in

Iran

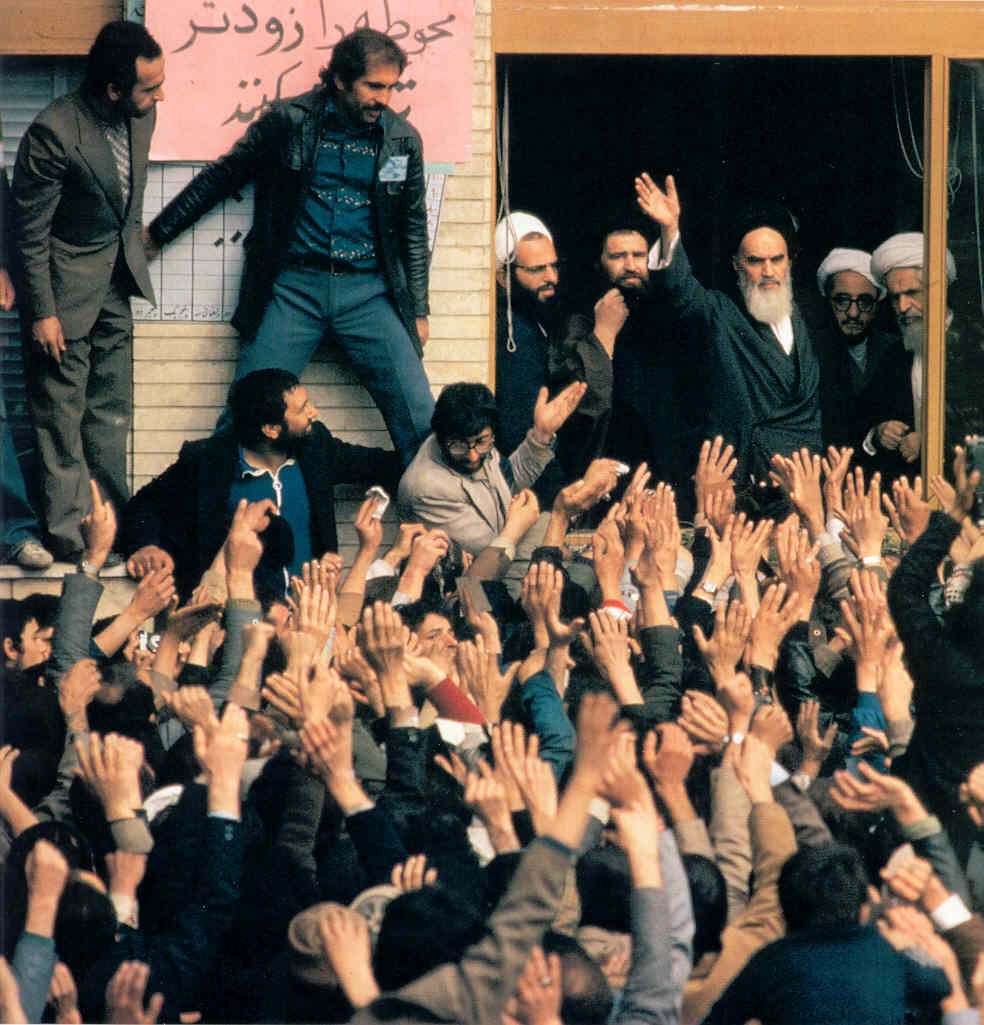

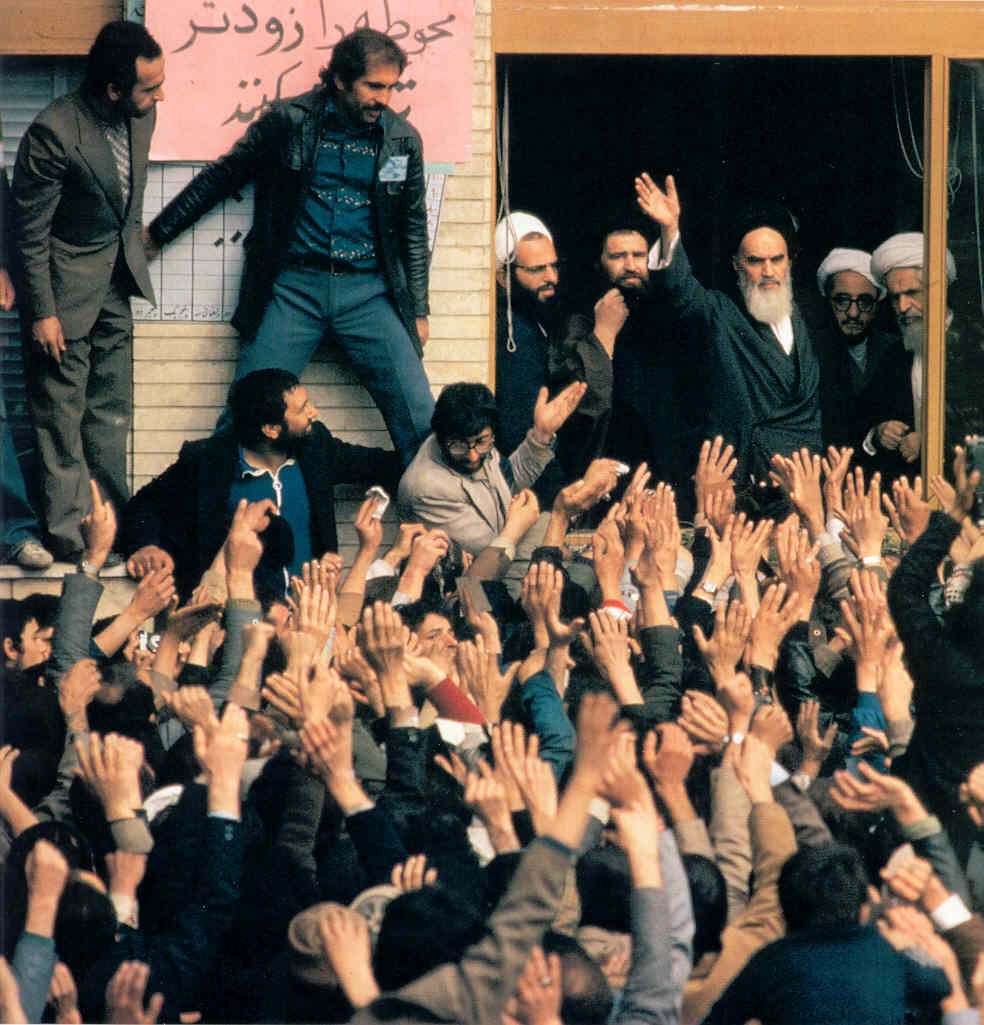

Followers of the Ayatollah

Khomeini celebrating his return to Iran from exile – Feb. 1979.

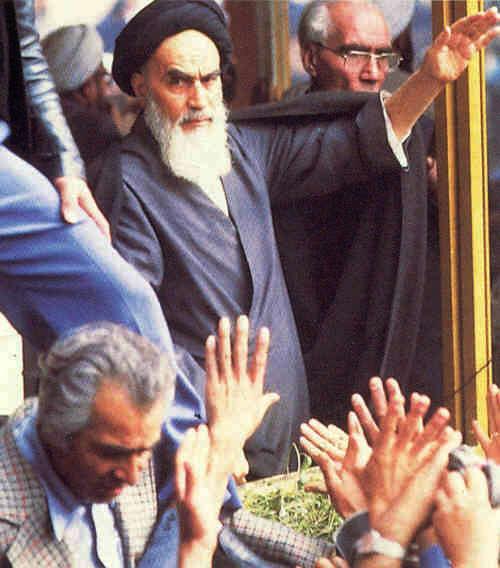

The Ayatollah Khomeini arriving

in Tehran – February 1979  Gas station attendants watching

Carter's July 15, 1979 energy speech

CAMP DAVID, CHINA, SALT II, AFGHANISTAN,

AND IRAN (ROUND TWO) |

|

The Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel (1978)

In September of 1978 Egyptian President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister

Menachem Begin (yes, the one-time leader of the murderous Israeli

terror organization Irgun!) met with Carter for almost two weeks at the

Camp David presidential retreat, to work out some kind of diplomatic

agreement to bring the Arab-Israeli standoff to an end.

Despite various United Nations resolutions and back-and-forth

diplomatic discussions going on between Israel and its Arab neighbors,

nothing had changed in the status quo since the 1973 October War. Egypt

was having economic hard times and Sadat was determined to get some

movement on the return of the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt as some kind of

political offering to his people. He thus decided to break from the

Arab front and do his own separate negotiating with the Israelis

(secretly of course). At the same time, Israel found dealing with a

single Arab nation rather than the broad Arab front, and the

possibility even of breaking up that front, to be a distinct political

advantage, and consequently received probes about a new

Egyptian-Israeli rapprochement gladly. Thus in November of 1977 Sadat

totally surprised the world (including Carter, who had no advance

warning of this development) by flying to Jerusalem and delivering a

speech before the Israeli Knesset (Parliament), calling for new

Egyptian-Israeli relations.

Carter was at first reluctant to get involved in the Byzantine

complexities of Arab-Israeli relations, but finally was convinced of

the need to participate in, even sponsor, formal talks between Begin

and Sadat. Besides, Sadat had put himself in a very vulnerable position

within the Arab world, and some kind of payoff from this diplomatic

initiative needed to be soon forthcoming, or a rather pro-American

Sadat would find himself in deep trouble. Thus Carter called for the

gathering at Camp David.

But the biggest problem was what to do about the Jordanian West Bank

and Gaza Strip (Palestinian territory) issue. Sadat was interested

mostly in the status of Egypt's Sinai Peninsula (still under Israeli

occupation), which was not of critical interest to the Israelis and

thus easily negotiable. But the issue of Palestine (also still under

Israeli occupation) was very much of critical interest to Israel,

though not vital to the interests of Egypt. However, it was a matter of

critical interest to the broader Arab front, whose shadow constantly

hung over the efforts to work out a peace between Egypt and Israel. And

Carter was insistent that there be a Palestinian agreement accompanying

any Egyptian-Israeli agreement over the Sinai. Thus negotiations

dragged on at Camp David day after day.

But in the end neither Begin nor Sadat wanted to alienate Carter with

his strong American position on the matter, nor return empty-handed

from the talks. Consequently Begin agreed to respect U.N. Resolution

242 in all its parts, and pull back Israeli occupation troops from

both the Sinai and the West Bank and Gaza regions, and transfer authority over the

latter region to the Palestinians, over a five-year period (Syria had

not participated and thus the Golan Heights were not included in the

agreement).

Not everyone in the larger or international world was happy. Some were,

including Norway's Nobel Committee which awarded both Sadat and Begin

the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize for this diplomatic breakthrough. Israeli

settlers in the Sinai however were deeply angered by having to pull out

of homes they had built there. Likewise, stiff opposition to the

agreement came from the United Nations, because it did not include all

the territory, and because it had not included the other neighboring

Arab governments in the deal (which actually would have made any

agreement impossible, as had long been the case). In the end, Carter

chose simply to ignore the outcry.

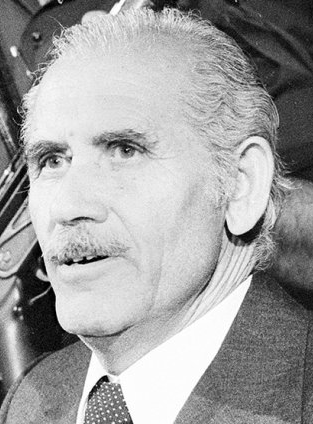

But Sadat paid a big price for his action. Egypt was kicked out of the

Arab League, lost its position as something of the leader of the Arab

world (which then prompted Saddam Hussein of Iraq to aspire to the same

position), and in the end cost Sadat his life – when some of his own

disenchanted troops (members of Egyptian Islamic Jihad) were able to

assassinate Sadat in 1981 during a review of his troops. But

nonetheless, the agreement held, and General Mubarak, in replacing

Sadat, would continue to follow the lines of the original Sadat

agreement.

|

Carter also believed that moral persuasion

might also bring the Arab-Israeli crisis

to a peaceful resolution.

But Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat beat him to the

punch by flying to Israel

to offer Egyptian terms of peace with Israel.

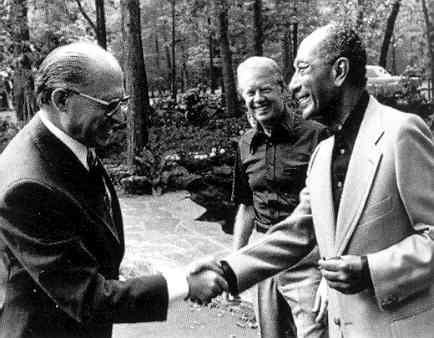

Israel's Prime Minister Menachem

Begin welcomes Egyptian President Anwar Sadat

to Jerusalem – November

1977

| Carter then moved to sponsor a

meeting at the President's Camp David retreat where he intended to see

some serious negotiations take place. Begin was dragging his feet on

some kind of compromise with Sadat ... putting Sadat in political trouble back in

Egypt the longer Begin held out. Carter would have to lean on Begin a bit to get him

to move forward.

|

Begin, Carter and Sadat at

Camp David – September 1978

Anwar Sadat and Menachem

Begin embracing while Jimmy Carter looks on – September 1978

Anwar Sadat, Menachim Begin

and Jimmy Carter at the end of the Camp David talks – September 1978

Menachem Begin and Anwar

Sadat

Menachem Begin and Anwar

Sadat

Egyptian President Anwar

Sadat, President Jimmy Carter and Israeli Prime Minister sign

Camp David

Accords in 1978

China

|

Ever since Nixon's visit to China in 1972 and the

establishing of the U.S. Liaison Office in Beijing in 1973, America had

attempted more or less normal relations with China. Then in 1977,

Carter saw the opportunity to further strengthen Chinese-American

relations (he now understood Realpolitik

quite well), sending his National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski

to China in August to start up a new round of diplomatic talks,

principally about the sticky problem of America's ongoing support of

Taiwan. Eventually U.S. negotiators accepted a full severance of

diplomatic ties with Taiwan, but under the promise of Beijing that

America would be allowed to continue freely its commercial relations

with Taiwan. This agreement thus led to Carter's invitation to Deng to

visit Washington in January of 1979 where together they could sign the

new diplomatic accords, preliminary to the formal recognition of China

later that year.

|

Carter also makes the decision to extend formal diplomatic recognition to the Communist

Government in Beijing ... confirming the fact (set in Nixon's presidency) that America

recognized Taiwan as actually part of China ... under the promise from Beijing

that America could continue to trade freely with Taiwan.

Carter receiving a visit in January of 1979 from Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping

A meeting in the White House of Carter and Deng Xiaoping and their diplomatic teams – January 1979

SALT II and the Soviets

Carter also wanted to follow-up on Nixon's

arms-limitation talks with the Soviets

|

Carter and Soviet Premier Brezhnev's SALT II Treaty (1979)

Then in June of 1979 Carter and Soviet Premier

Leonid Brezhnev met in Vienna to sign a SALT II Agreement, updating the

1972 Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) signed years earlier by

Nixon and Brezhnev. Weapons technology and production levels had

advanced tremendously in the intervening seven years and thus the

purpose of the new agreement was to bring nuclear delivery devices

(notably the MIRV missiles capable of carrying multiple nuclear

warheads) under some kind of restriction or balance. But there were

also political motives behind the agreement, Russia becoming a bit

nervous over the serious improvement in Chinese-American relations

(China and Russia were more adversaries than Communist allies at that

point). And, with the Soviets seeming to be pushing ahead of America in

the arms race, Carter was concerned about one-sided self-limitation in

weapons development, a self-limitation on weapons development that he

himself had once supported strongly. Thus here too, Realpolitik was

now directing Carter in his conduct of American foreign policy.

Nonetheless, there was a huge reaction

(especially among Republicans) that the arms limitations levels agreed

on in Carter's new treaty merely placed limits on arms production if

one or the other of the parties was willing to make such limitations

(which Carter was, as part of his general philosophy), without any

clear enforcement provisions if one of the parties (namely the Soviets)

chose to push ahead in weapons development. But it ultimately came down

to the fact that America was going to have to decide whether to go

ahead and trust Carter on this matter of enforcement, or not.

Consequently, the debate on SALT-II in

the U.S. Senate dragged on endlessly, until December of 1979 when the

Soviets invaded Afghanistan. This abruptly killed the prospects for the

ratification of the treaty. The following month Carter simply withdrew

the treaty from further Senate consideration. SALT II was not

completely dead. But from this point on, only something of a diplomatic

"understanding" on this matter existed between America and the Soviets,

sometimes respected, sometimes not.

|

Carter and

Brezhnev

Carter and

Brezhnev

Carter and Brezhnev sign

SALT II in Vienna – June 1979

HOWEVER ... Carter withdrew the

treaty

from Senate confirmation in January 1980 after the USSR invaded

Afghanistan.

Afghanistan

|

The Soviets, in late December of 1979, had sent

their own special forces into Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, taking

over the governmental offices and presidential palace. This was

accompanied by a larger and broader ground invasion of Soviet troops.

The Soviets were attempting to take over directly the governing of

Afghanistan.

The Afghan government had been in a state

of turmoil since 1973 when the Afghan King Zahir Shah's cousin,

Mohammed Daoud Khan, ousted the Shah and announced the creation of the

Afghan Republic, with himself as president. But Daoud's government was

much too secular for the tastes of the very conservative Afghan Muslim

society, and he failed to establish popular support for his government.

Also he tried to follow a neutral foreign policy in the Cold War,

succeeding only in alienating the Soviets who considered Afghanistan as

part of their sphere of influence. Two competing Afghan Communist

parties, with help from the Soviets, finally got their act together and

started putting pressure on Daoud, who reacted strongly.

In April of 1978 the Communists acted.

Daoud was assassinated and a Communist "Democratic Republic" under Nur

Mohammad Taraki was announced. Taraki began moving swiftly against his

opponents, especially the country's conservative leadership and

pro-Western intellectuals. Perhaps 27,000 of the country's leaders were

arrested and executed in Afghan prisons over the next year and a half.

By October of 1978 a full rebellion in

the Afghanistan countryside was underway, spreading quickly to the

outlying Afghan cities as well. Much of the Afghan army soon went over

to the rebels.

Taraki now called on the Soviet Union for

help (December). Then in mid-1979, Carter began to send secret aid to

the rebels (so much for "open diplomacy"!) The situation for the

Communist government only worsened through 1979 and thus it was that

another Communist leader, Hafizullah Amin, decided to try to save the

situation by getting rid of Taraki (murdered) and taking over the

government. But the Soviets immediately began to have suspicions about

Amin being a reliable ally. Also the United States basically appeared

to be merely lukewarm in its ultimate interest and minor in influence

in the region, and the Soviets thus supposed that they had no reason to

fear any kind of a serious reaction coming from America.

Thus it was that in December of 1979 they

made their move to take direct control of the country. Amin was

assassinated (KGB) and Babrak Karmal was now installed as the new

president, who in turn "invited" the full military assistance of the

Soviet Union.

The Soviet War in Afghanistan was on. But

the Soviets were about to find out what the Americans had discovered in

Vietnam, but apparently had not learned from the experience (nor had

the Soviets learned from their own experience in defeating Hitler's

invasion of Russia).2

Fighting local militia or guerrilla warriors with conventionally armed

troops is an unbalanced contest, favoring heavily the local forces. It

was going to take massive numbers of soldiers and supplies to bring the

Afghans under Soviet rule, something at that time that the Soviets were

increasingly less able to afford.

2Nor had America learned from its own War of Independence against the English King and his troops back in the late 1700s.

Mohammad Daoud Khan

Nur Mohammad Taraki

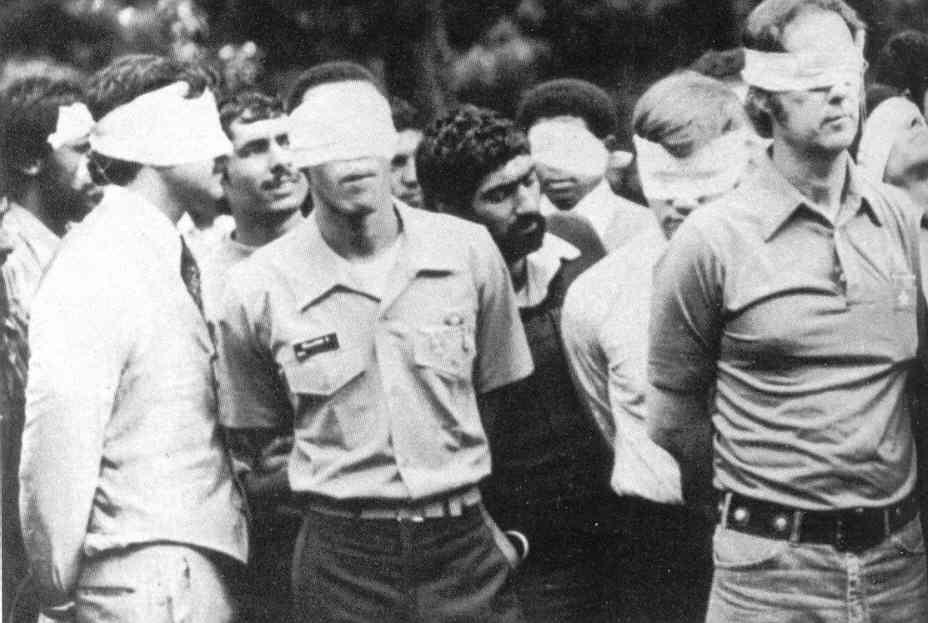

AMERICAN DIPLOMATS IMPRISONED IN IRAN |

|

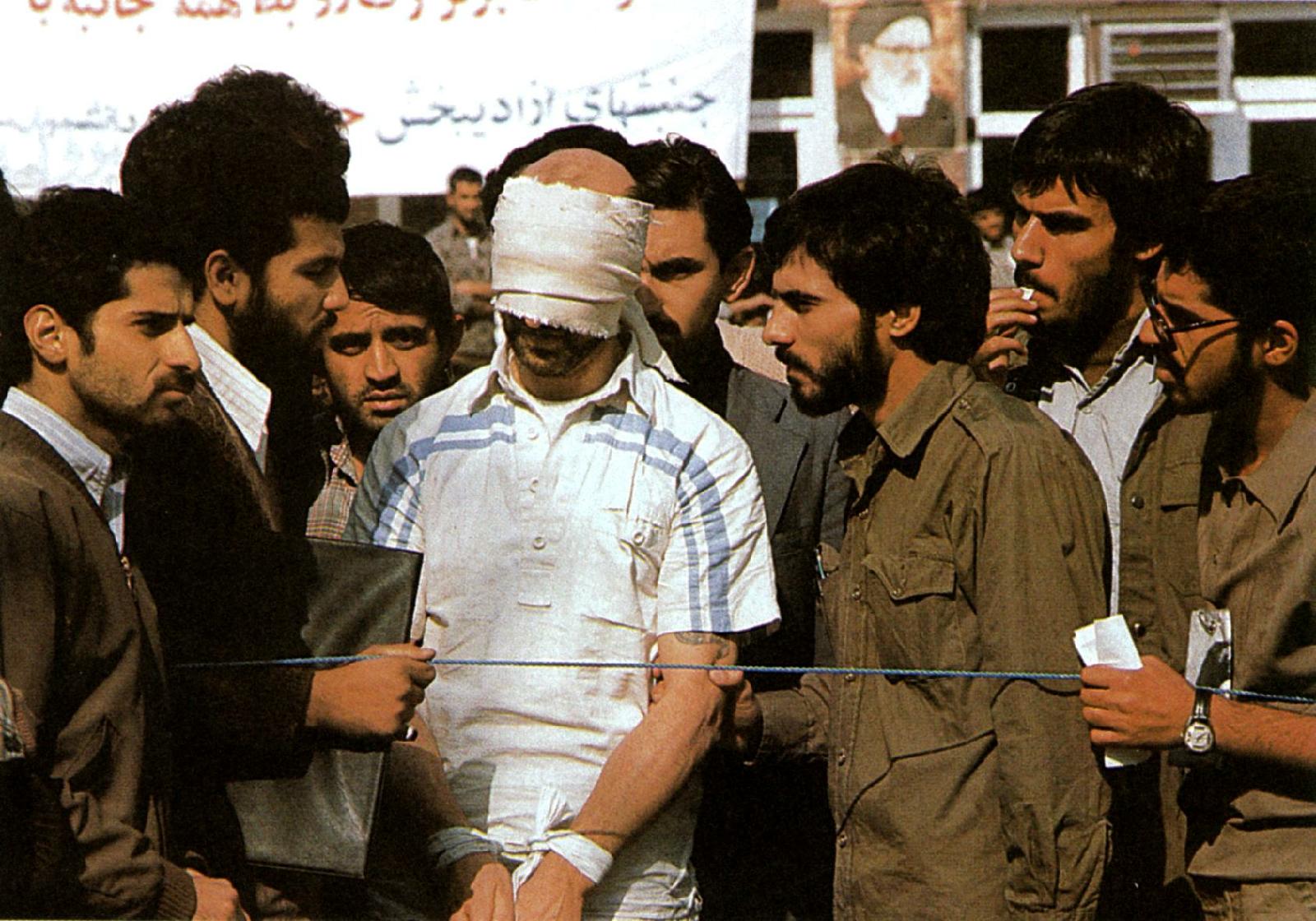

America's further humiliation delivered by Iran

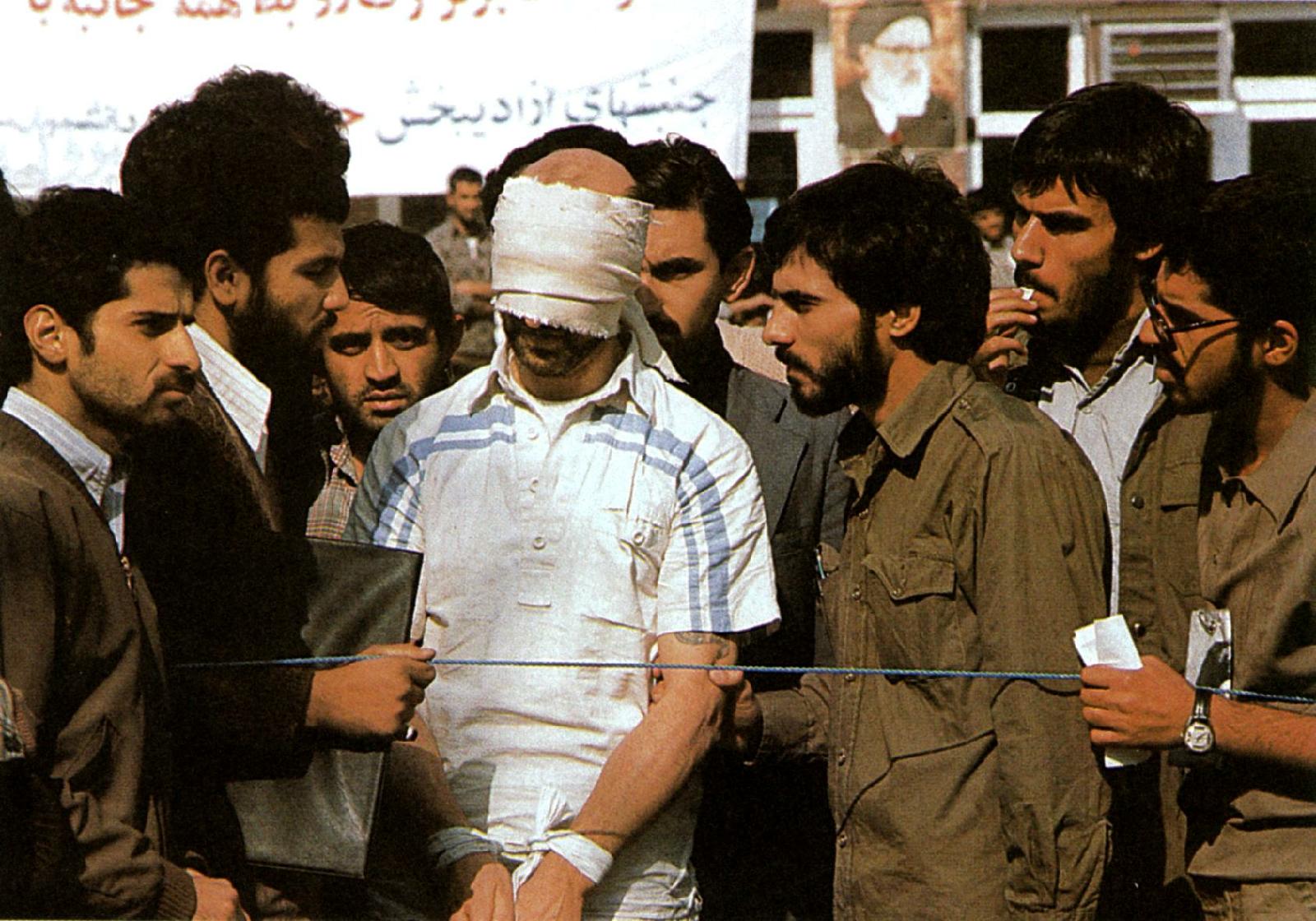

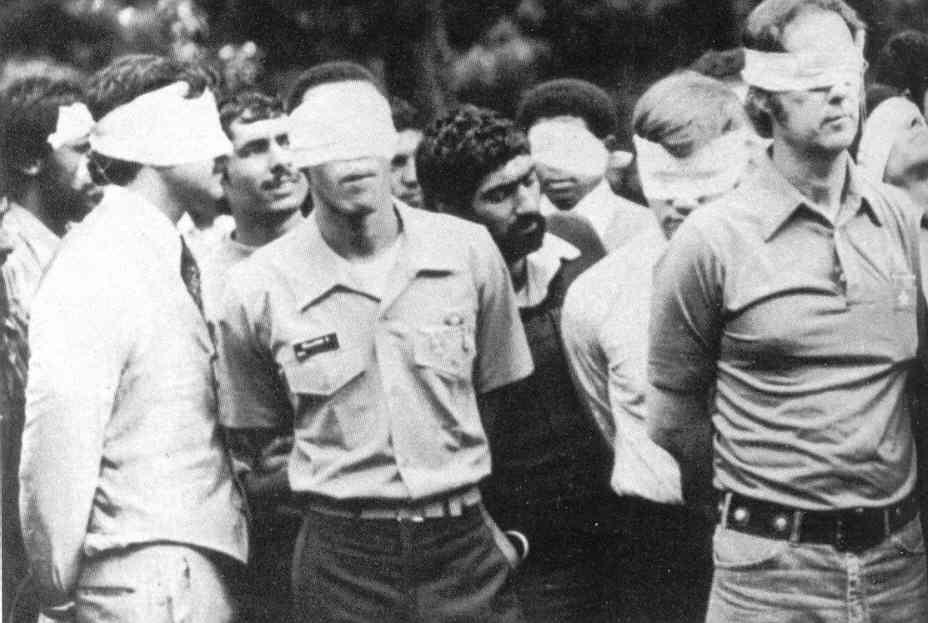

Meanwhile, in October of 1979, the ousted Shah,

who had developed cancer, was under consideration by Carter for

admission to the U.S. for treatment. On hearing this, Muslim students

in Iran went wild, and members of the militant Revolutionary Guard in

early November invaded the American embassy, seizing the staff and

displaying them to the world, tied and blindfolded as their sign of

contempt for the United States. The Iranians loved it, and a month

later, amidst a huge swell of Iranian patriotism, they easily passed

the referendum approving the establishment of their new Islamic

Republic.

For Carter this was the ultimate

humiliation. He was taking hits from the economy as well, because the

Iranian upheaval had severely cut back on Iran's oil production. And

oil prices, as well as inflation, climbed for the second time in the

decade of the 1970s. As a sign of how bad things were for Carter, Ted

Kennedy, who was now feeling more confident about a presidential run of

his own, was unabashedly loud in his attacks on Carter's presidential

performance.

|

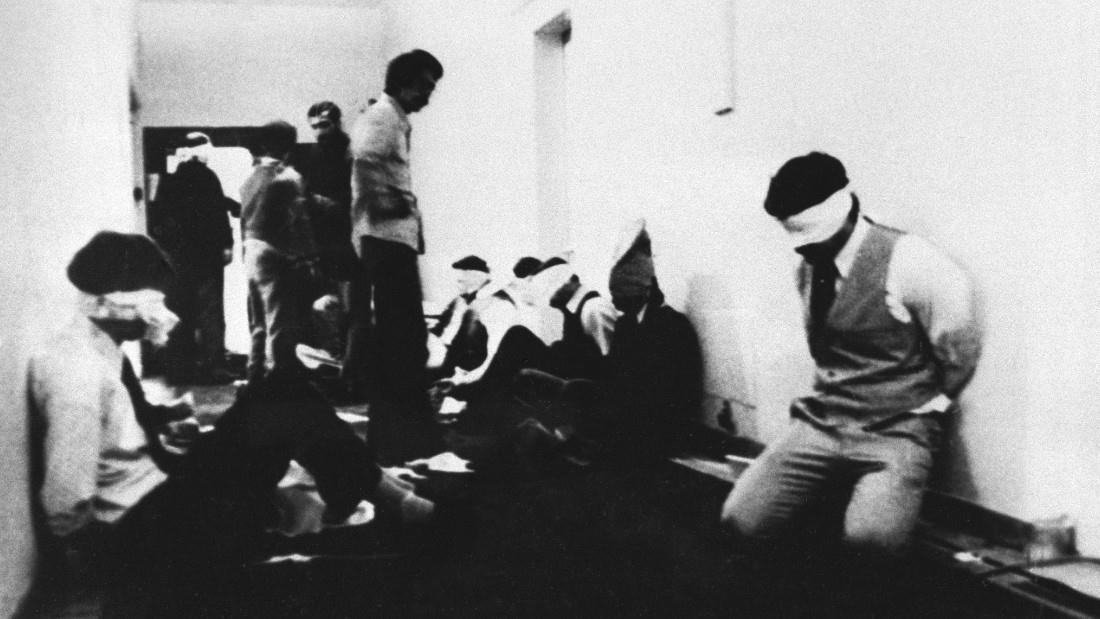

Iranian youth climbing over the wall

of the American Embassy – November 4, 1979

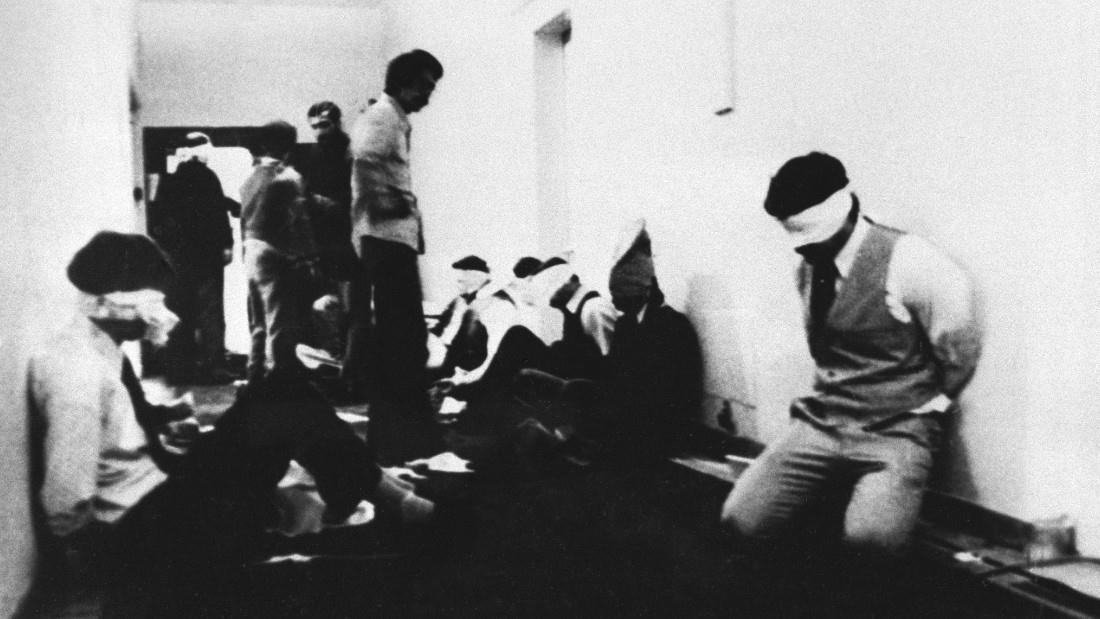

Some of the 90 hostages taken at the US

Embassy – November 4, 1979

American embassy staff taken

hostage in Tehran by Muslim radicals – November 4, 1979

American embassy staff taken

hostage in Tehran by Muslim radicals – November 4, 1979

US Black hostages released by Khomeini in

November (he also released the women hostages as

well)

|

The disastrous rescue attempt in Iran (April 1980).

In an attempt to rebuild his reputation

(especially as he was facing a re-election bid that year), Carter

gambled on an attempt to rescue the American hostages with a Special

Forces raid on Teheran, the Iranian capital (Operation Eagle Claw). His

plan was to drop his Delta troops by eight helicopters outside of

Tehran, convey them by truck at night into a darkened Tehran (Americans

also having first shut down Tehran's electrical grid) to round up the

fifty-two American hostages at the embassy, and then fly them out of

the country.

The raid however turned out to be a total

disaster from the start and never got any further than just inside

southern Iran before it disintegrated in a combination of sandstorm and

mechanical failure of three of the helicopters, and, after the decision

to withdraw, the collision of another of the helicopters with one of

the six C-130 transport planes (involving the deaths of eight American

troops).

Now Carter's humiliation grew even worse – monumentally worse.

|

Wreckage at Desert One, Iran,

where eight Americans died – April 24, 1980

A burned-out and

abandoned US helicopter in Iran (Operation

Eagle Claw)  Carter ready to deliver a

nationally televised speech (April 25, 1980) announcing the failed rescue mission in

Iran

|

America was feeling the sting of failure

abroad and economic worries at home. The oil crisis had thrown the

economy into another recession of industrial slowdown and rising

unemployment, accompanied at the same time by an inflation set off by

fast-rising energy prices. Americans were hurting. The misery index was

rising rapidly as the summer election season was approaching, and

Carter was seeking re-election.

Carter's boycott of the Moscow Olympic Games

Carter only made the situation worse for

himself when he returned to his "moral politics" agenda and announced

that the United States would not be participating in the Moscow summer

Olympics (July 1980) if the Russians had not pulled out of Afghanistan

by then. It was a strange threat, for there was little likelihood that

the threat was going to result in anything except that American

athletes were not going to be able to compete in the big event they had

been training for (the Soviets returned the favor by boycotting the

1984 summer Olympics in Los Angeles). In the end it made Carter look

petty and desperate. It only worsened his image as a national leader.

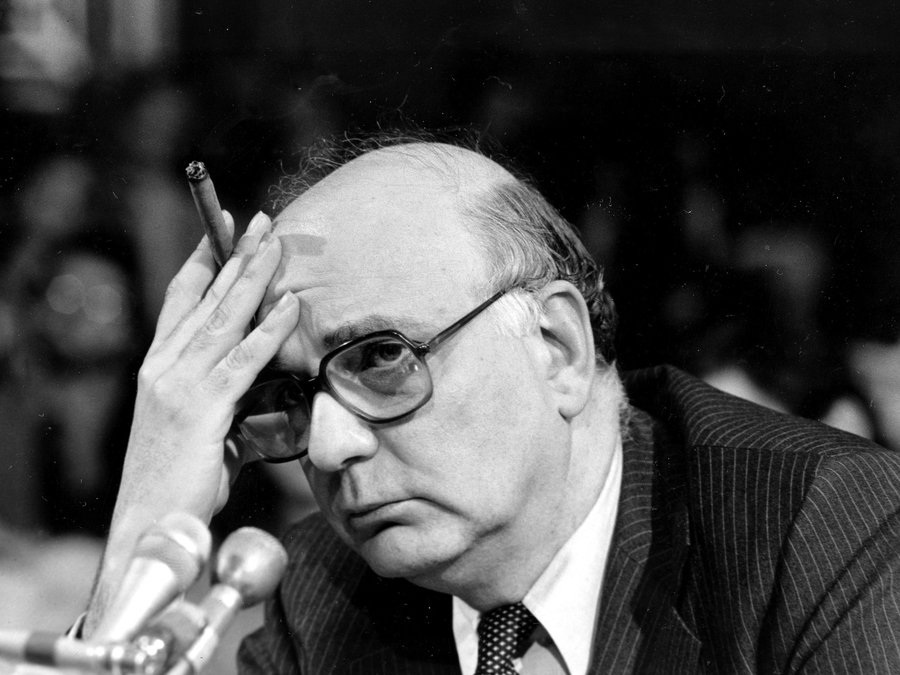

VOLCKER'S "MONETARISM" TO THE RESCUE? |

|

"Stagflation" (Economic Stagnation and Financial Inflation)

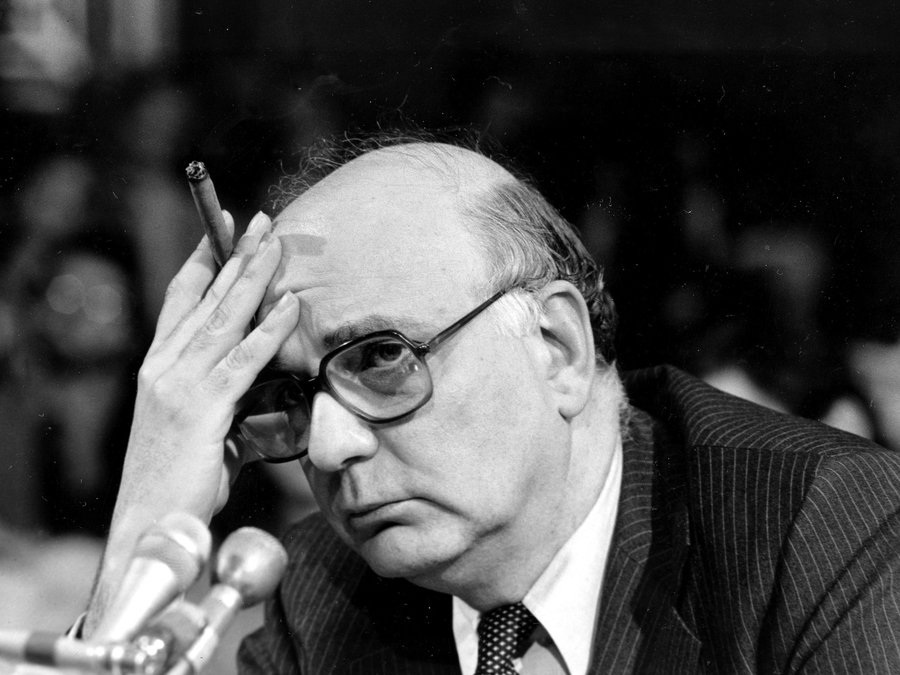

But ultimately what guaranteed that the Carter

presidency would be a one-term presidency was the economy. Carter's own

appointed Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker decided in the latter

part of 1979 to attack the high inflation set loose by the huge

three-fold oil price hike (caused by Iran's withdrawal from the

international oil market) – and the need of the rest of the industrial

economy to raise prices on their products in order to maintain some

degree of profitability in the face of the new energy costs. Volcker

decided that he was going to solve the problem of runaway inflation –

by the Federal Reserve's putting into play a huge tightening of

America's dollar reserves, driving interest rates astronomically high.

He believed that this would indeed kill inflation (if it didn't also

destroy the American economy!).

Thus by cutting back severely the amount

of dollar reserves available for lending to America's banks, Volcker

drove the Federal Reserve discount rate all the way to 20 percent, in

turn forcing the large commercial banks (all of whom borrowed from the

Federal Reserve to maintain their own supply of lending power) to have

to set their prime rates at 21.5 percent, for even their best

industrial customers. This strategy Volcker called "monetarism."

Volcker's "monetarist" (tight money)

strategy was designed to make Americans feel poor enough that they

would stop spending, and thus presumably force down prices, and

supposedly inflation with it. This was also supposed to strengthen the

dollar. At least that was the theory Volcker was supposedly working

under.

What this actually meant was that

industrial enterprises, facing a three-fold increase in their energy

costs in their operations, now found themselves also having to make

huge interest payments on the bank loans on which their businesses

depended. To survive at all, to meet skyrocketing operating costs (now

both energy and interest expenses), they were forced to have to raise

(not lower!) prices on their products quite considerably – to make

enough money just to barely stay in business. In short, Volcker's

monetarist strategy served to drive inflation even further upward.

But far worse, with car loans and house

mortgages borrowed from American banks now running at Volcker's new

rates (forcing the banks' 30-year mortgage rates to run at about 16

percent and industrial prime lending rates up to 21 and 22 percent),

Americans decided to hold off buying a new car or buying that new home.

Thus now with few customers coming through their doors, businesses

found themselves in deep trouble. Soon these businesses began to shut

down, one by one.

Consequently, everywhere the economy not only slowed down, as Volcker intended, it plunged downward in a death spiral.

But Volcker was determined to hang tough

until he single-handedly had "shaken the last of inflation out of the

economy" (or so he said). That was except for the brief period over the

summer of 1980 when Volcker dropped interest rates, to release the

economy from his imposed restraints and thus get it up and moving again

in time to get Carter re-nominated to the Democratic Party ticket. The

economy immediately responded by picking up again.

But before the November elections rolled

around, Volcker decided to take the interest rates right back up again,

plunging the economy back into deep recession, which in turn had the

Americans going to the polls feeling very grumpy. This helped produce a

very humiliating Carter defeat in the 1980 general elections.

But tragically Volcker's monetarist

strategy also helped worsen what were at this point already shaky

American heavy or basic industries (steel, chemicals, cloth,

construction), forcing many businesses either to shut their doors,

never to reopen, or go "offshore" with their operations (to Japan,

India, Thailand, etc.), never to return to America.

And banks, at first making huge windfall

profits on the basis of the new interest charges imposed on their

customers, soon found that they too were losing customers – as no one

came to the banks looking for mortgages or car loans.

And commercial and industrial

bankruptcies were not what the banks wanted either. Commercial

bankruptcy now got pushed onto the creditor banks who had formerly

funded these now-bankrupt companies more than they were now worth.

True, the banks received title to these bankrupt companies. But what

were the banks to do with these companies? They could not sell them to

investors willing to take them off their hands. There were no such

investors willing to take on the financing necessary to purchase even

these bankrupt companies. Thus it was that American banks now found

themselves also in debt. They could, of course, borrow from the federal

reserve. But what bank was foolish enough to take on federal reserve

loans running at times almost at 20 percent interest? Within short

order, American banks also began to fail one by one.

Thus it was that the only thing that

Volcker's monetarism actually achieved was first the ruination of the

American industrial sector and then the collapsing of much of America's

financial sector as a follow-up.

America now fell into a deep recession,

one that American businesses and consumers had no idea of how to climb

out of. Certainly Volcker's federal reserve bank was of no help in

addressing the problem. At this point it was one of the chief causes of

the problem!

|

Once again ... long lines to the gas pumps

Federal Reserve Chairman

Paul Volcker

Federal Reserve Chairman

Paul Volcker

IN THE MEANTIME, A NUMBER OF OTHER POLITICAL

CAUSES CONTINUE TO ADVANCE WITHIN AMERICA ITSELF |

Environment versus Energy

priorities create a festering sore

On

March 28, 1979, large amounts of reactor coolant and radioactive gasses were released into

the atmosphere, forcing the abandonment in a 20-mile radius of 140,000 people from their

Pennsylvania homes. Cleanup took four years ... and greatly advanced the cause of

the anti-nuclear protest groups.

The shut-down Three-Mile Island

nuclear

power plant – April 1979

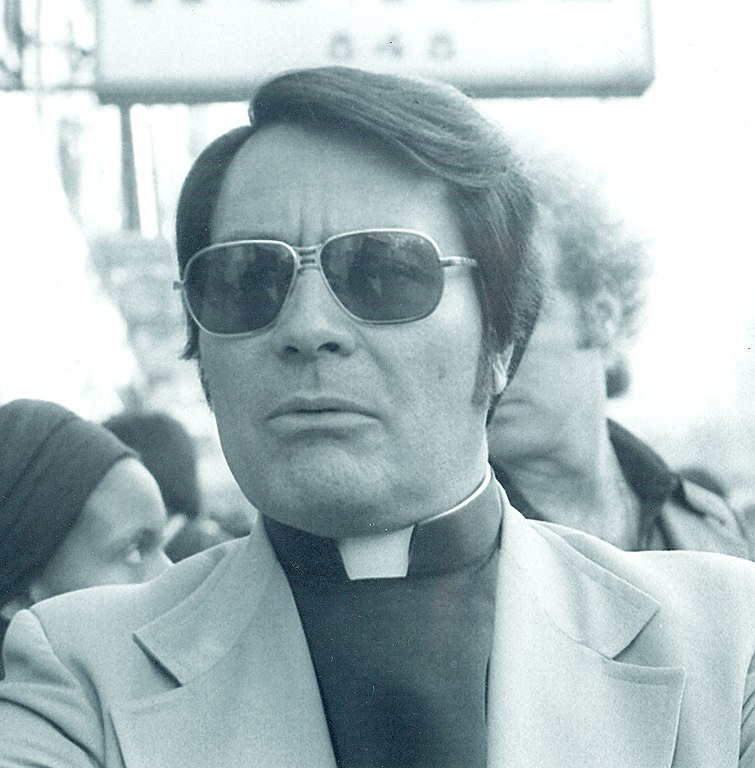

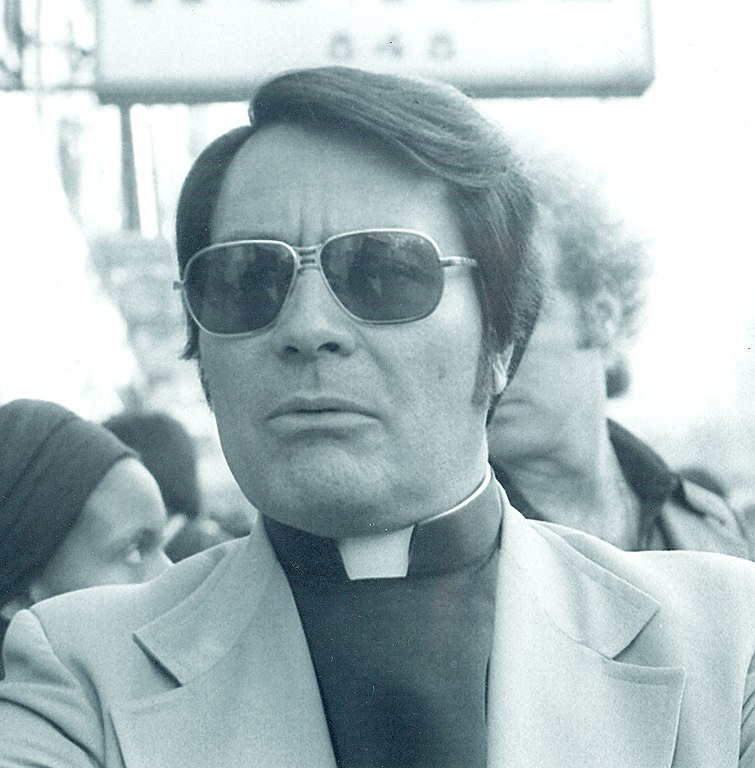

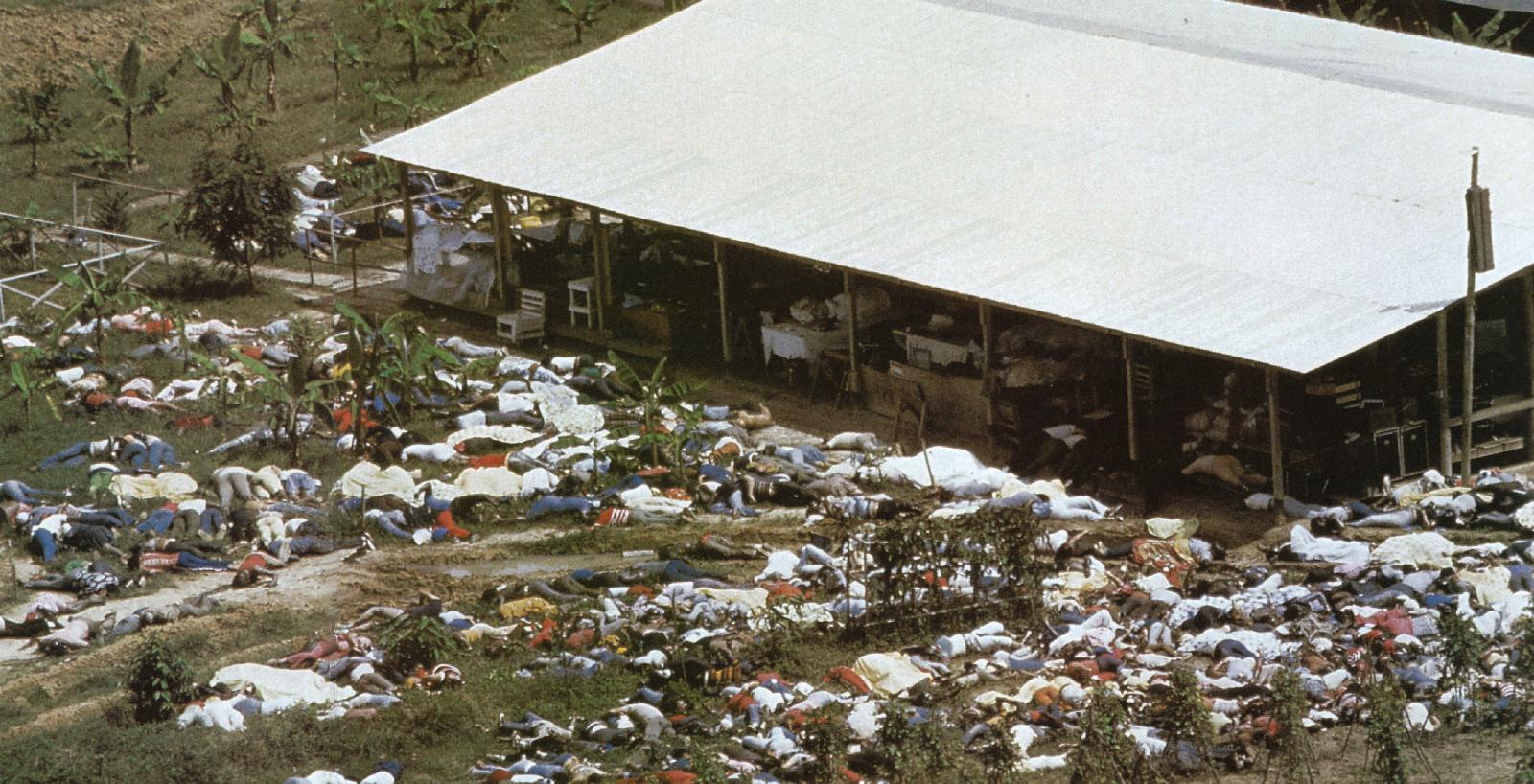

A tragedy that had nothing to do with American politics was the Jim Jones massacre in Guyana

The "Christian" cult leader Rev. Jim Jones (mid 1950s to November 1978)

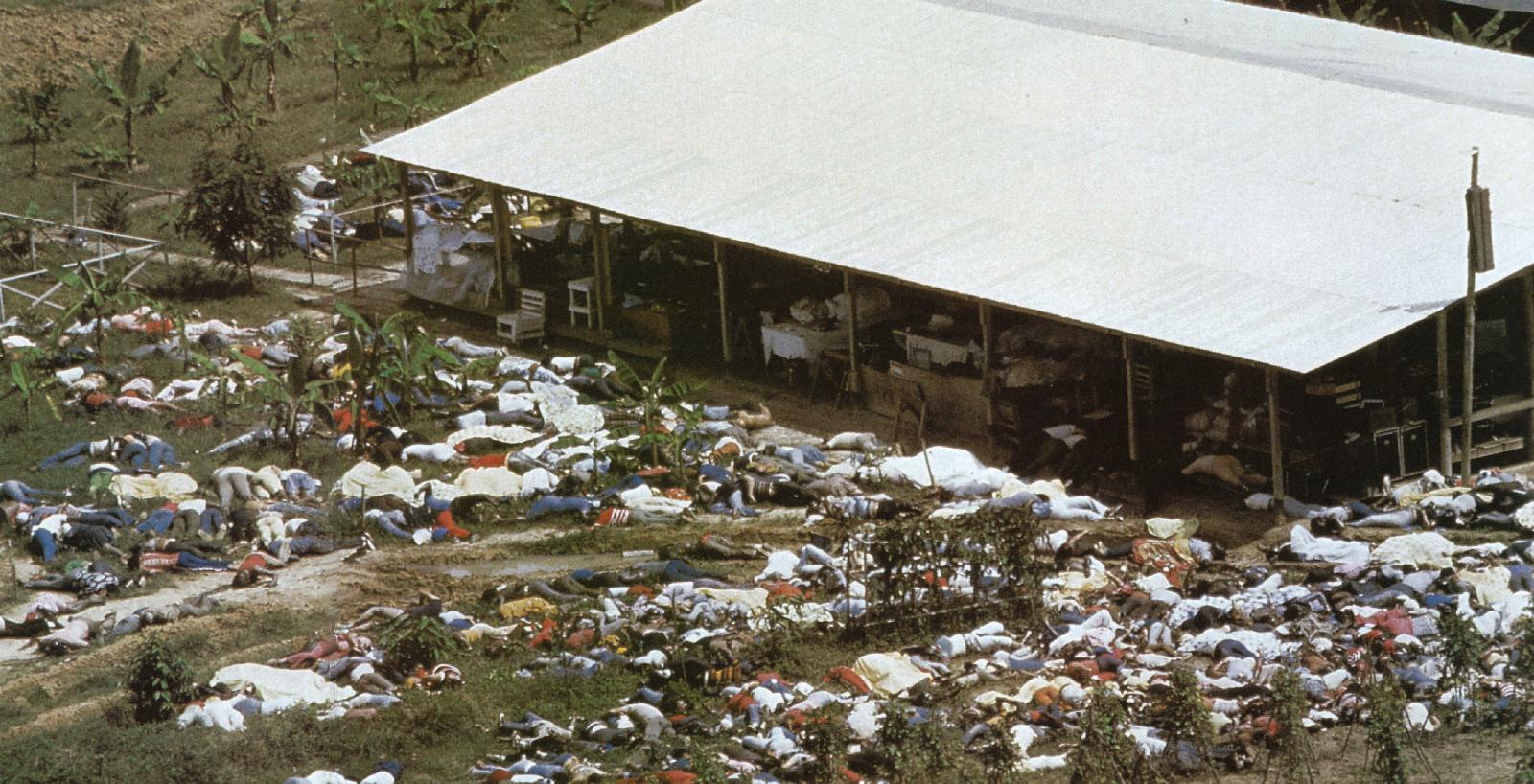

900 dead of self-inflicted (or forced) cyanide (grape-flavored "Kool-Aid") poisoning at the "Peoples

Temple" at the Jim Jones Compound, "Jonestown" November 1978 ... ordered by the cult leader

Jim Jones (he took his own life in the process as well). Also killed (shot) were US Congressman

Leo Ryan and several news reporters as they were leaving the area following a visit to investigate

rumors of massive abuse.

The program was a Jones-developed offshoot of a "Christian socialism" program which originated

in Indianapolis, Indiana ... which extolled the social virtues of living in a "communal" world similar to

the Soviet world (which Jones constantly extolled and even gifted lavishly financially).

Go on to the next section: A Deepening Cultural Split

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

The American Bicentennial – 1976

The American Bicentennial – 1976

Jimmy Carter and the national elections

Jimmy Carter and the national elections Carter proposes a foreign policy of

Carter proposes a foreign policy of The surrender of the Panama Canal

The surrender of the Panama Canal

Other international issues during the

Other international issues during the American diplomats imprisoned in Iran

American diplomats imprisoned in Iran

Volcker's "monetarism" to the rescue?

Volcker's "monetarism" to the rescue?

Other political causes continue to

Other political causes continue to