23. THE TROUBLED 1970s

CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP IN THE WHITE HOUSE

CONTENTS

Nixon Nixon

Ford Ford

Carter Carter

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 263-270.

|

Where did America's political leaders, as

defenders of the long-standing Christian social order, take their stand

in America's unrelenting move toward Boomer Secular-Humanism – and

"democracy by judicial decree"?

Nixon had been raised in a Quaker home,

second of five boys, in a very Quaker community (Whittier, California).

Nixon's mother was the product of two centuries of Quaker heritage.

However, his Methodist father became a Quaker only in marrying Nixon's

mother, and when Nixon was thirteen, he and his father went forward

together at a local revival to commit themselves to Christ. In high

school Nixon proved himself to be an excellent student and was awarded

his senior year the prestigious Harvard Club prize. But disappointment

accompanied all his hard-earned successes. He lost a hard-fought

election for the position as student body president, was never popular

with the girls, and his family could not pay the balance of the cost of

a Harvard education.1 So instead he headed off to the local Whittier College.

In his senior year in college, his

Christian faith was deeply shaken by his brother's death, and by

extensive exploration of the traditions and claims of his Christian

faith. Although he would continue to identify himself as a Christian,

and observe rather normal Christian practices, his actual spiritual

life from then on would always remain a very private matter.

Receiving a generous scholarship, Nixon headed off to Duke Law School, again doing very well, graduating summa cum laude in

1937. But with the Depression in full swing, jobs were just not to be

found (a Harvard degree would have helped, which Nixon sadly was always

aware of) and he returned to his hometown to practice law there. Here

he met and two years later (1940) married a local school teacher, Pat

Ryan.

In early 1942, in response to America's

entry into World War Two, the Nixons moved to Washington for him to

take up a position in the bureaucracy, a job which Nixon ended up

hating. He soon gained entry into the U.S. Navy as a lieutenant junior

grade and in mid-1943 was moved closer to the action in the South

Pacific. Here he rose quickly in rank as an administrative officer and

would serve until the beginning of 1946. However, he would remain in

the Naval Reserves all the way up until he retired at the rank of

commander in 1966.

At the beginning of 1946 Nixon was called

back to California by the local Republican Party, to take up the

electoral campaign for Congress against the Democratic incumbent Jerry

Voorhis. Questioning Voorhis's intelligence and political sympathies

(suggesting that they were Communist in nature) he soundly defeated his

opponent that November.

In Washington, Nixon was active in his

support of the Marshall Plan, and also the investigation into the

extent of Communist infiltration into American politics, especially at

its highest levels. In 1948 he took the lead in pushing forward the

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigation into the

activities of Alger Hiss. This would begin the problems Nixon would

have henceforth with the members of America's intellectual community,

who were fully convinced of Hiss's innocence, and angry over what they

considered to be Nixon's unwarranted obsession with a "Red Threat"

endangering America. Of course, time would prove that Nixon was

entirely correct in the Hiss matter. And indeed, Nixon was onto the

dangers of the rising Cold War long before many other Americans

understood the challenges and dangers involved in this new form of

ideological battle.

Motivating Nixon was certainly some form

of continuing influence of his Quaker upbringing. Nixon's no-nonsense

approach to moral matters formed the very heart of his personal view of

life, making him both certain and inflexible in his approach to his

public, political life. But there was also another side to his

character, certainly also of Quaker origin, in that he spent much time

in the Bible, and in quiet prayer, which he himself stated was to

listen to God – not tell God what to do. In this he was much like his

Quaker mother: very strict when it came to ideas of moral performance,

but very private when it came to matters of personal faith.

Nixon knew the Bible well, but did not

include Biblical references in his public addresses as president. And

although he frequently referenced God, he seldom spoke of Jesus.

Yet he was well-aware of America's Christian history, and in his 1972

Thanksgiving Address underlined the fact that Puritan founder John

Winthrop was most correct in identifying America as God's "city set

upon a hill," that it was important to follow the Puritan heritage in

being "the light of the world," and that it had always been America's

call by God, and source of the country's greatness, to provide

spiritual leadership to that world. He also stated that every American

president had found cause to turn to God, ultimately leaving office

with a very deep religious faith.

As president, Nixon often held worship

services in the White House, with a variety of pastors of all faiths

(Protestant, Catholic, Jewish) leading the various services. It served

several purposes: cutting down the uproar of press, protesters and just

the curious that accompanied his Sunday attendance at local churches;

setting some kind of religious tone to life in the White House; and, of

course, helping his political image among his many Christian supporters

nationwide.2

Perhaps even more significant in defining

the religious character of the Nixon presidency was the close

relationship Nixon cultivated with the "power of positive thinking"

pastor Norman Vincent Peale of New York City's Marble Collegiate

Church, but even more importantly the evangelist Billy Graham, with

whom Nixon developed a close friendship, perhaps the closest of all.

They met, discussed, prayed together constantly. But ultimately that

friendship would have to pay a huge price for the scandal that

ultimately broke Nixon, indeed, broke many of the Nixon circle:

Watergate.

Because ultimately what will always bring

Americans to measure Nixon as a Christian was Watergate, from Nixon's

vulgar language and commentaries on America's various social groups, to

ultimately his effort to cover up the whole mess of the break-in.

It is a bit reminiscent of the Biblical

King David, Israel's most beloved king, who was caught by the prophet

Nathan trying to cover up his affair with Bathsheba, and the depth David

was willing to go (having her loyal husband killed in battle) in the

affair, in order to also cover up the birth of the child that developed

out of this misadventure. Both Nixon's and David's crises pointed to a

problem that has never been resolved by man – how so easily tremendous

power in the hands of a fully sovereign ruler can come to destroy the

integrity of that same individual. David repented; Nixon resigned. Both

lived on after that. But the favor they had once enjoyed (Nixon's 60

percent vote in 1972, for instance) would be forever ruined after that.

Worse, Nixon is still today not really remembered for all the ways he

served his country extremely well as president. It seems instead that

he will always be remembered by generations to come as Nixon, the evil

president.

1They

needed that money to pay for the health care of Nixon's ailing

older-brother Harold, who died of tuberculosis in 1933 (as had a

younger brother Arthur in 1925) – leaving Nixon deeply shattered over

his brothers' deaths.

2In 1973 the atheist Madalyn Murray O'Hair tried to get a federal court to shut down these White House services.

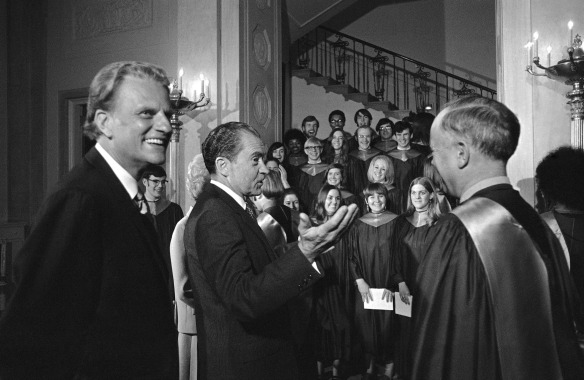

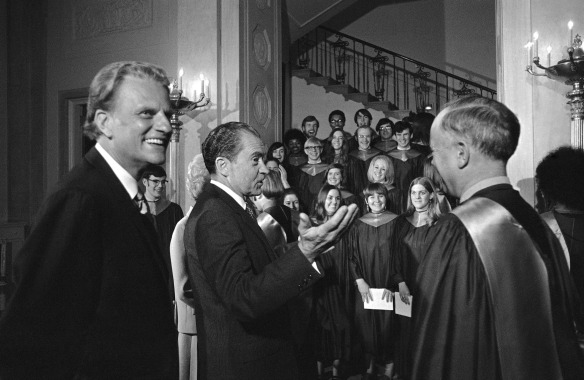

Nixon, following a worship service at the White House conducted by Billy Graham – March 15, 1970

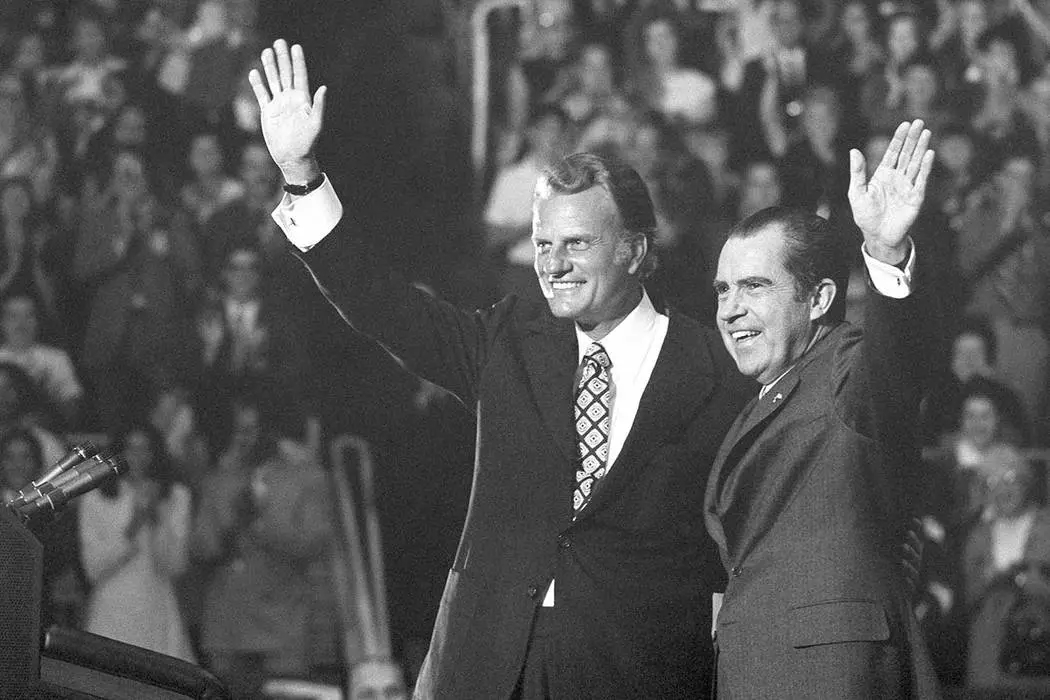

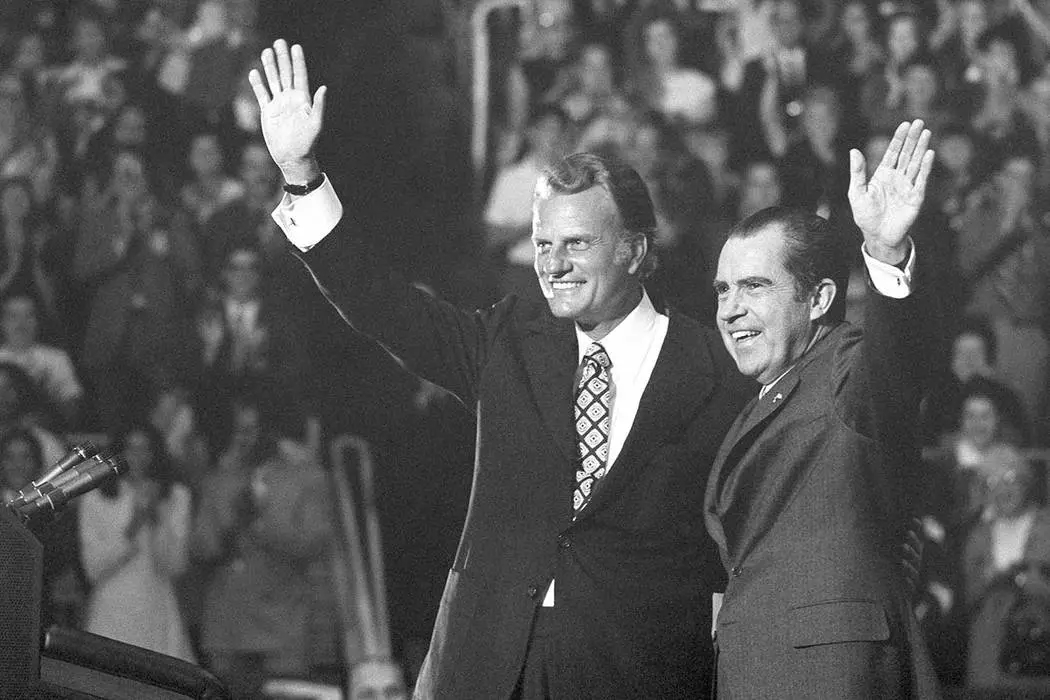

Nixon and Graham in Charlotte, North Carolina – 1971

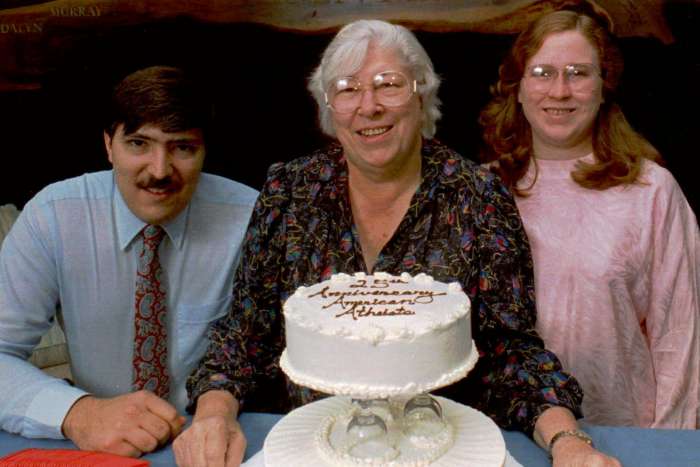

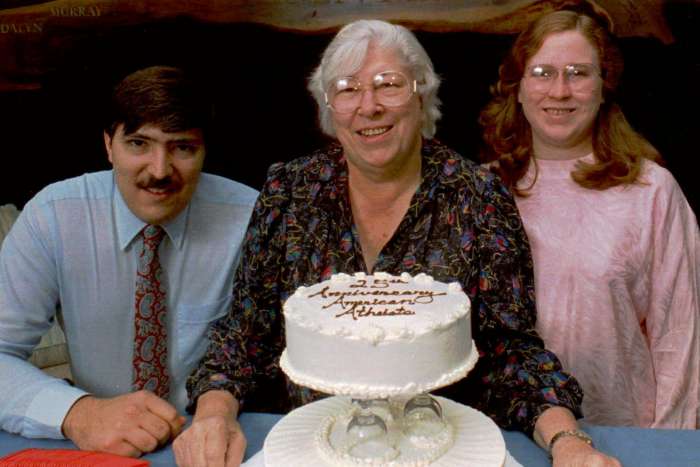

Famous atheist and strongly pro-Communist Idealist, Madalyn Murray O'Hair,

with son Jon and granddaughter Robin - June 1988

Besides

constantly bringing lawsuits to court to block Christian practice in

public, Madalyn had been strongly opposed to Nixon's Christian White

House.

Oddly enough, another son, William (below), would eventually become a

very well-known Christian ... and chairman of the Religious Freedom

Coalition |

|

The individual left with the responsibility of

getting America past this huge mess was indeed a profoundly deep

Christian. He was of course an all-around good guy, able to pull off

one of the greatest feats in American political history which is to get

both his Democrat and Republican colleagues in Congress to like and

respect him deeply.

In his college days he proved to be an

outstanding athlete, whom professional football teams wanted badly to

recruit upon graduation. But Ford chose to go to Yale Law School

instead. And thus his career headed in a political rather than an

athletic direction. He served in the Navy during World War Two, first

as a physical trainer, then aboard an aircraft carrier in the Pacific,

where he experienced the horror of sea battles with the Japanese. After

the war he returned to Grand Rapids to take up law practice. And in

1948 he ran for the local House seat in Congress, and was easily

elected. In fact, he would be easily re-elected to that same House seat

thereafter – all the way up to his Vice-Presidential appointment in

1973.

Spending most of his time in Washington,

he and his wife Betty were very active in the Episcopal Immanuel

Church-on-the-Hill in Alexandria (Virginia), and Ford was a regular

participant with fellow congressmen in a weekly prayer breakfast they

held together.

But the real measure of Ford as a

Christian was how he handled the most important responsibility of his

presidency, dropped into his lap immediately upon taking that

responsibility in August of 1974: getting the nation past this horrible

social-moral trauma of Watergate. The Democrats were prepared to pursue

this matter for however long it took to destroy Nixon, and probably

much of the country's remaining moral nerve along with it. After a

month of constant prayer over the matter, Ford did the one thing that

the nation needed most: forgiveness, so that the nation could move

ahead in its existence. He knew well that this would cost him his standing

with many of his old Congressional friends. He knew that if he had any

thought to continue national service as president, he was undercutting

that possibility, probably irreparably. But a month into his office as

president, after Sunday morning worship, he returned to the White House

to announce to the world that he was issuing a comprehensive

presidential pardon for Nixon. The Democrats, and even many Republicans

were outraged. They wanted revenge for Nixon's acts of injustice, not

pardon.

But for the well-being of the country

this was absolutely the right decision. And he was able to make this

decision because he was a Christian, not a Secular "peace and social

justice" warrior.

Forgiveness always comes at a huge price,

one that human pride finds very difficult to muster. The human ego

instinctively prefers revenge – and has well-developed means by which

to rationalize or justify that burning desire. That's why we hire

lawyers: to achieve "justice." But forgiveness is the most important of

all Christian virtues, powerful in the way it restores broken life

(which "justice" seldom achieves).

God forgave man by placing his son on

that cruel Roman cross, and Jesus uttered those words of that same

forgiveness even as he was dying. Christians – not social justice

warriors – are supposed to understand the totally irrational value of

forgiveness, even when it comes (as it always does) at a huge price.

But it is a price that ultimately saves, saves big, much bigger than

"social justice" (raw revenge).3

And that was Ford the Christian, acting

in a totally Christ-like manner, in order to save his nation from its

self-destructive quest for "justice." It cost Ford dearly, to save

America from itself. But he did, and America moved forward, amazingly

quickly afterwards.

It had to have inspired Graham and others

who had put so much trust in Nixon, and felt so deeply betrayed by

Watergate. But ultimately Graham and some others moved on, even rebuilt

a relationship with the disgraced former president, and Nixon himself

moved on, actually to serve as wise counsel to future presidents and

political officials. The social justice warriors, of course, never

forgave Nixon, and were able to write that unforgiveness into their

history books, even elementary and high school textbooks, ones that

would remember Nixon only as that evil president.

But didn't the social justice warriors

forgive Ted Kennedy for Chappaquiddick? No, not really.

They just simply put it out of their minds and thus avoided having to

pay some kind of personal price in the matter. It was simply as

if the event never actually happened. That's not

forgiveness. That's politics.

3Thus

it was that unlike the British and French who took revenge on Germany

after World War One – and soon paid a heavy price in the form of Nazi

revenge paid back to Britain and France – Truman was quick to forgive

Germany and Japan after World war Two ... and bring them into close

friendship with America.

Ford announces his presidential pardon of Nixon – September 8, 1974.

|

|

Carter grew up in a family of non-conformists

living in an out-of-the-way small town of Plains in Southwestern

Georgia. All of his family went off in different directions, Jimmy

Carter taking the road of a regular church-attending born-again-Baptist

(much like his father, though not his rather independent-minded and

socially quite "Liberal" mother). Carter's dream growing up was to

attend the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. But he had to take a more

normal post-high school route of attending Georgia state colleges for

two years before finally being admitted to the Academy. Here

(1943-1946) he spent the war-years training to become a naval officer.

He did quite well academically, also continuing to maintain his deep

Christian convictions and loyalties. And he did so as well during his

years serving as a nuclear engineer in the world o f the submarine. But

when his father died in 1953, he left the navy to take over part of

(and soon rebuild) the family farm, where back in Plains he became,

like his father, a very active member of the local Baptist church. Here

he also followed his mother's path in resisting the enormous pressures

placed on him to fall in line with the segregationist mindset of the

local community.

In 1962 he turned to politics, defeating

an opponent in a very dirty race waged against Carter for a seat in the

Georgia state Senate. Here he proved to be a very hard-working

legislator (actually a compulsion to stay on top of every detail in

every matter possible, which would always haunt his managerial style).

He also tended to be very critical of the flaws or imperfections of his

political colleagues – which tended to make him something of a

political loner in the state capital. But he got things done.

But when he then chose to run for the position of Georgia governor in 1966,4

he did not even qualify for the Democratic Party runoff, and ultimately

the spot went to the arch-segregationist Lester Maddox. This defeat

threw Carter into something of a personal crisis. But with the help of

his evangelist sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, and some time in prayer, Bible study, and reflection, he underwent

something of yet another born-again experience. This ultimately led him

to take time off to do door-to-door evangelistic work in the North

(Pennsylvania and Massachusetts), most notably in impoverished Hispanic

communities.

But in 1970 he returned to Georgia, again

running for the Democratic Party candidacy as governor (hiding his

Liberal attitudes away from public view) and this time gaining the

Democratic Party nomination and thus also the governor's office at the

capital in Atlanta. During the campaign he never answered the Liberal

attacks of the Atlanta media, which by doing so gave off the impression

that he was indeed the segregationist they accused him of being, which

actually helped build his vote in rural Georgia! But as governor

(1971-1975) he was quick to reveal himself to be not the White

segregationist as many had been led to believe.5

His big push as governor was in the area

of massive bureaucratic restructuring, extensive educational

programming for the poor, racial integration, and environmental

protection, issues not that different from the ones going on in

Washington at the time. Meanwhile, since Georgia governors were limited

to a single term, Carter realized early on that he needed to look more

broadly at his options if he were to remain in the business of

politics. His attempts to bring notice to his name in the 1972

Democratic National Convention got him nowhere. But in 1973 he was able

to get David Rockefeller to make him a part of Rockefeller's

prestigious Trilateral Commission (set up that year to promote

international cooperation among Japan, Western Europe and North

America) – finally bringing some degree of national notice to Carter.

Also, Robert Strauss, chairman of the Democratic National Committee,

asked Carter if he would head up the party's Congressional Campaign

Committee, to help Democratic Party candidates in the 1974

Congressional midterm elections. This would put Carter in close

relationship with national politicians. And thus when the 1976

elections swung into view, Carter was in a position to gain an early

lead in the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary. Suddenly the Carter

name was on everybody's lips. Who was this inspiring new face out of

Georgia?

In the campaign, much attention was paid

to Carter's frequent acknowledgement of his "born-again" relationship

with God in Jesus Christ, something that many of the more secular press

and even the old staid denominations knew little about at that point.

But like Kennedy in 1960, Carter was very careful to distinguish

between his personal faith and his approach to the civic duties of the

U.S. presidency. Mostly, America came to understand what it was that

Carter was trying to clarify in his very Baptist idea of the absolute

separation of church and state. Strength in one area did not mean

weakness in the other. They were just two different worlds.

Well maybe. Certainly Carter made it

clear that Scripture gave no prescriptions on handling environmental

problems, health care programs, national educational policy, etc. Those

were matters of state, not religion, although certainly informed by a

Christian sense of charity for the poor and weak, and the key

understanding of the basic equality of all (and thus equal importance

of all) in the nation. And indeed Carter had been very strong on this

matter as Georgia governor.

In November, 1976, he was elected

president and certainly tried to honor his Christian precepts while

serving in that office. But, as already noted, high principles and

complex realities were not easily blended. When he tried to pursue high

principles, things messed up quickly on the political playing fields.

But he was a fast learner, and ultimately found that high principle is

best served by a strong understanding of the reality of human nature

and behavior (thus Political Realism) – which Christianity itself has

no particular argument with or opposition to (unlike Humanism!).

As president, Carter was actually less

likely than his predecessors to make public demonstration of his

personal faith, sensitive to the possibility of being accused of

forgetting his promise to keep church and state separate during his

presidency. Even Billy Graham was almost never seen around the White

House, although a big part of this was a result of some harsh words

exchanged during the Carter-Ford contest, when Graham proved rather

clearly to be a Ford supporter. 6

Nonetheless, prayers, Bible study and

Christian spiritual reflection were a strong part of the Carter

presidency, all the way to the end of his four-year presidency. And if

nothing else, this certainly helped introduce the nation to the idea of

the more evangelical, born-again side of the Christian faith (which was

also being pushed forward by the growing charismatic movement of the

1970s and after).

4He

could have so easily won the position as Congressman that year if he

had run for the House seat rather than the governorship. But a

Congressional seat would have probably ended the possibilities of his

finding the way to the White House as he ultimately did.

5The

seemingly gentle Carter could get very tough – even cynical – as a

campaigner … and then once in office return to being the high-minded

individual that he was capable of being.

6They would, however, over the coming years develop a quite close relationship.

Presidents Carter, Bush, Sr. and Clinton with Billy Graham

praying at the dedication of the Billy Graham Library – May 2007

Carter delivers a Sunday School lesson at the Baptist Church

in his hometown of Plains, Georgia – August 23, 2015

Go on to the next section: Reagan – Strong Replaces Nice

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

Nixon

Nixon