26. BUSH (II) FUMBLES THE BALL

THE BUSH ECONOMY

CONTENTS

The growing national debt crisis and The growing national debt crisis and

American trade imbalance

The growing income inequality in The growing income inequality in

America

The September 2008 financial meltdown The September 2008 financial meltdown

TARP: Bush

moves to bail out the TARP: Bush

moves to bail out the

troubled firms (October 2008)

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 375-386.

THE GROWING NATIONAL DEBT AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE IMBALANCE |

|

The growth of the American national debt.

During the Bush Presidency the American economy

seemed to stall. The American economy was fairly strong, but not

growing, certainly not at the rate that it had been used to over the

years since the end of World War Two. And it seemed that the primary

way that the economy, and Americans themselves, could maintain the

nation's prosperity was by going into debt, not a good thing over the

long term. Americans sensed the dangers, but were not quite sure what

to do about the situation.

By the beginning of the last full year of

the Bush presidency (2008) the debt of the U.S. government had climbed

to around ten trillion dollars, more than double what it had been when

he took office at the beginning of 2001. This figure meant that every

American citizen, man, woman and child, each shared about $30 thousand

of their government's debt or about $60 thousand for each tax-paying

worker.

During those seven years the national

economy registered dollar growth, but not nearly as fast a rate as the

public debt. In 2001 the public debt stood in size at about 57 percent

of the figure for the national economy or Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

By the beginning of 2008 that figure had grown to 70 percent.

The U.S. Treasury Department could not simply print money to cover that

debt. Instead it had to sell its debt as "securities" to investors who

were willing to buy these securities, with the promise that the owners'

investments would be paid back in the future along with accumulated

interest earnings. Americans themselves bought some of that debt in the

form of government bonds (EE bonds being the favorite). Retirement

programs and insurance companies bought some of the debt as a low risk

(but also low paying) investment. Interestingly nearly half of that

debt was bought by the government itself, in particular the nation's

Social Security program (which at this point held about two trillion

dollars of the debt) and other U.S. government trust funds.

Slightly more than another quarter of the

U.S. public debt was held by foreigners, either governments or banks,

as part of their hard currency reserves (the U.S. dollar gradually

replaced gold as the international monetary standard, and at that point

was still constituting about 60 percent of the world's hard-currency

reserves). The two biggest holders of dollars were by far China and

Japan with each of them possessing about 20 percent of these foreign

holdings.

There are several reasons for anyone

wanting to purchase U.S. government securities. But one of these

reasons certainly is the interest payments that the government had to

make to the owners of these securities. This could however get to be a

very expensive part of the government's operating budget, as in the

past when the Federal Reserve forced American interest rates up to

about 20 percent. Such a high interest rate would mean that the

government could have been paying $200 million a year on each $1

billion in debt, something the government simply could not have

sustained.

Actually, toward the end of the Bush

presidency the Federal Reserve was holding that interest rate to under

1 percent! This made the size of the government's interest payments on

the debt quite manageable. But such low rates were most exceptional

historically. If people and countries were to lose confidence in the

American economy, they could certainly have demanded higher interest

payments before they would be willing to continue to buy these

securities. Having to raise interest rates on these securities would

have been a blow to the government budget, which would have had to

raise taxes, cut back on programs or raise more debt, or a bit of all

three of these measures. This would have put a great strain on the

economy and set off a round of fears about the economy that could have

escalated into even greater problems in selling the national debt.

The huge American trade imbalance

While there was no question about how bad

the American national debt was, the question of the huge imbalance in

American trade was much more debatable: was it a bad thing or a good

thing? Americans were importing more goods than they were exporting.

This produced what is called a deficit in the balance of trade. Since

1997 this deficit had grown monumentally. By the last years of the Bush

presidency the size of the trade deficit was about $700 billion

annually.

The biggest source of the imbalance in

trade was China. America was importing more than four times the value

in goods that it exported to China. This trade deficit with China made

up about a third of the total American trade deficit. As a result of

this, China had been accumulating huge dollar holdings, some of which

it used to purchase U.S. debt, and some of which was used to buy up

assets around the world, such as oil, minerals, corporations, etc.

Originally (back in the 1980s and 1990s)

America had been willing to open up its markets to Chinese goods as a

means of helping China convert from a Communist (Socialist) economy to

a free-market or capitalist economy. At the same time, the Chinese

markets were allowed to be protected against sophisticated American

goods, in order to help China develop its own free-market industries.

And the Chinese currency, the renminbi or yuan, was allowed to be held

artificially low to help keep the prices of Chinese goods low so that

they could be more competitive in the international (and particularly

the American) market.

But those years of infancy in the Chinese

industry at this point were gone. China had the second largest national

economy in the world, and was continuing to grow rapidly around 8

percent to 10 percent a year. But the protections remained in place,

despite American complaints that it was time to let the renminbi float

to a natural market level and to end China's restrictions against the

importation of foreign goods. But America had to tread warily, because

it needed China to buy continuing (growing) American debt. The loss of

the Chinese investor in the American debt would spell serious trouble

for the American government. In a sense, America now found itself in a

financial trap of its own making – with no good means by which to get

out of this situation. This was indeed very bad for America – and

possibly for the world, at least the world that America was trying to

support.

But China was not the only country

benefiting from an American trade imbalance. Nearly every one of

America's major trade partners enjoyed a large surplus in trade (and

thus a strengthening of their dollar holdings) due to the fact that

Americans purchased more than they sold abroad. The argument was often

put forward that this was actually a very good thing for the world

economy. The American consumer market was the engine that ran the

world's economy. It was important not only to China, but also to Japan,

Mexico, Korea, Germany, Britain, and in fact the European Union in

general, where American purchases of their goods added greatly to the

profitability of their companies. Only Canada, America's largest trade

partner, traded at anything like parity with America (but Canada too ran

a small 5 percent surplus in its trade with America).

|

Former long-time Federal Reserve

chairman Alan Greenspan

... and replacement nominee, Ben Bernanke

(2005)

GROWING INCOME INEQUALITY IN AMERICA ... AND

THE CULTURE OF GREED |

The growing income inequality in America

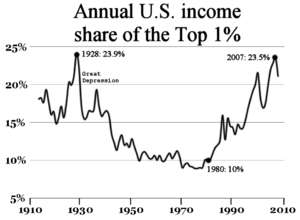

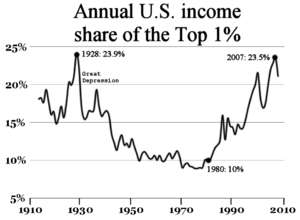

A study put out by the Center on Budget

and Policy Priorities (January 23, 2007), based on figures released by

the Congressional Budget Office, showed how American after-tax incomes

had changed over the period 1979 to 2004. The lowest fifth of income

earners had advanced only by 6 percent during that 25-year period. The

next highest fifth had advanced by 17 percent, the middle fifth by 21

percent, and the next highest fifth by 29 percent. But the incomes of

the highest fifth group had advanced during that time by 69 percent;

and of that last group the top 1 percent of income earners had advanced

by 176 percent. The gap between the richest and poorest Americans was

widening rapidly. This was an economic profile looking very much like

the massive inequality that developed in the late 1800s – the "Gilded

Age" of the industrial "robber barons" (America's super-rich families)!

A similar study published in The New York Times

(March 29, 2007) pointed out that during the one year alone of 2005 the

national income figure increased by almost 9 percent. That sounds like

great growth for the country. However, the study pointed out that

nearly all that growth occurred with the top 10 percent of income

earners; the lower 90 percent actually showed a slight dip in incomes

of 0.6 percent. And of the top 10 percent, it was the top 1 percent

that registered the largest growth, namely 14 percent. Indeed, the top

0.1 percent of the population (some 300,000 individuals) had almost the

same total income as the bottom 50 percent or 150 million Americans.

Their incomes were 440 times the average income of the lower half of

the economic scale, almost twice the disparity that it was in 1980.

There were all kinds of explanations for

this growing gap. The loss in the late 1970s and early 1980s of

decent-paying blue-collar industrial jobs overseas to countries that

pay their workers less was certainly one of the factors. Another was

that as America turned away from manufacturing to service industries in

the areas of banking, insurance, medicine, law, high tech

communications, etc. more education was required of America's workers.

The high-school diploma was no longer adequate, and thus more expensive

post-secondary and even post-collegiate graduate study was required,

necessitating the increase in salaries of those employed in these

service industries in order to cover the schooling expenses they had

incurred. Also the figures were skewed downward by the huge influx of

foreign workers (documented and undocumented) who filled the very

low-paying manual-labor jobs unwanted by Americans. Certainly these

factors contributed to the income gaps between the richest and poorest

in America.

But the gaps were widening at a pace

faster than could be explained by simply the shift in American industry

from manufacture to the service industries. The statistics for the

shift in the one year alone, 2005, demonstrated the size of the

problem. Incomes went up at that rate because some people simply

expected their incomes to go up at that rate. Other Americans were

forced to be content merely with holding their own.

For example, in the field of medicine

each year the size of the average medical insurance premium jumped

anywhere from 6 to 10 or 12 percent. In no way could anyone say that

the medical industry had improved that much over the previous year,

that it therefore justified an annual increase in payments of that

size. Everyone in the medical industry pointed to others in the medical

industry. Hospitals got the biggest blame, right along with trial

lawyers specializing in medical malpractice suits. But people who sued

doctors (encouraged by the trial lawyers) were to blame. So were the

doctors who in the past made sure that there was a scarcity of medical

schools training new doctors. Thus many American medical students went

abroad for their studies, and many practices had recently been taken up

by English speaking immigrants from Pakistan or India in order to fill

the gap.

Or the field of higher education as

another example. Here too expenses (tuition, room, board and books) had

been climbing much faster than the national inflation rate. For middle

and lower-income families this made a higher education almost beyond

reach. Scholarships were available, though these were pegged to the

performance of the economy, which had not been growing much over the

past decade or so. Where did this tuition money go? More classrooms and

teachers? Not usually. America had not only the fanciest hospitals in

the world, it had the fanciest college stadiums, research laboratories,

libraries, student centers and administrative buildings (and

administrative salaries) in the world.

Corporate salaries of company CEOs were

another example of the kind of social differentiation that was going

on, one that set some Americans way above others in social rewards,

prestige, and the ability to demand even more. The explanation was that

if companies did not offer such salaries to their executives, they

would lose out in the salary-bidding game to their competitors. And

this game got more competitive over time. That is why the top salaries

were growing at such a stupendous rate (that included also the salaries

of hospital administrators and university presidents as well as

industrial and commercial presidents).

Indebtedness and "entitlements" as a way of American life

Another reason that the upper income

earners were able to get away with the large annual increases in their

incomes was because the average American believed that people should be

able to have as much as they felt entitled to. There was, so far,

little grudging of the huge incomes of the top earners by those who

were making far less. "Get what you can out of life" was almost a

national mantra (especially with the rise of the Boomers).

In line with this same mentality was the

fact that despite the slow growth in the income level of most

Americans, nothing had stopped them from accumulating the material

blessings that would have come their way had their incomes actually

increased. They simply purchased what they wanted on credit, with the

vague idea that eventually they would pay down their debts – someday.

Credit card companies had been willing to extend credit limits

fantastically beyond what people were realistically able to carry –

even though this would produce a high likelihood of eventual default or

bankruptcy on the part of their customers. Like the stock market craze

of the latter half of the 1920s, greedy expectations had blinded

Americans to the need to bring this destructive thinking under some

kind of discipline.

But then the huge run-up of the national

debt seemed to fit well with this same mentality. The government had

been able to accumulate this massive, virtually unrepayable, national

debt – without alarming the country too much, because indebtedness set

off no alarms to a huge number of Americans any more. Massive

indebtedness had simply become part of the American way of life.

Wikipedia – Financial crisis of

2007-2008

THE 2008 FINANCIAL MELTDOWN |

|

The subprime mortgage crisis

This economic mentality was very much a part of

the housing boom and house-pricing bubble that started to climb in the

mid-1990s, and by around 2005-2006 had hit a very dangerous peak (note

however that this was not just an American phenomenon during this

period but almost universal in the industrial world). People were

watching the prices of houses climb rapidly during this time (the

average price of an American home doubled during that ten-year period),

to a point where two thoughts worked together to get people into the

housing market – and way over their heads in mortgage debt. Firstly,

for first-time buyers, they had a feeling that if they waited, the

prices of their dream houses would get even further beyond their reach.

Secondly, they speculated (as people do typically in times of a growing

bubble) that if they found themselves overstretched with mortgage

payments, they could always sell their houses later at a much higher

price, and even come away with a nice profit in the process. But as

with all such bubblesque or speculative thinking, that was presuming

that prices would continue to climb skyward continuously.

Also most of these buyers financed these

expensive homes with adjustable-interest mortgages (ARMs), which

initially were always a bit lower than fixed-interest mortgage rates.

But of course adjustable interest-rates could do just that, adjust over

time, normally in an upward direction. All of these factors were a

recipe for financial disaster.

Banks were aware that people were buying

houses they could not afford, but they continued to extend to them

anyway subprime mortgages ("subprime" because they were highly risky in

terms of the borrower's real financial ability to meet future

payments), throwing caution to the wind. Banks were competing in the

numbers game to see which of them had the largest dollar amount of

assets.1

The awaiting disaster finally hit in 2007

when housing construction finally began to outpace housing sales,

leading contractors to have to start lowering house prices in order to

clear their inventory of completed but empty houses. Therefore, people

needing to move were finding that they too had to lower the prices on

their houses in order to make a sale. Soon the competition to find

buyers heated up and housing prices began to drop dramatically. Banks

began to get nervous and rescheduled adjustable-rate loans at higher

interest rates. Many subprime borrowers found that they could not keep

up the payments at these higher rates, and lost their houses to the

lending banks. But the banks really did not want the houses, they

wanted the mortgage payments. Now the banks had to turn around and sell

the houses – often for less than the banks themselves had invested in

them in terms of the original mortgages. Thus the banks began to fall

into trouble right along with the failed homeowners. The housing bubble

was bursting.

Americans expected banks and financial

experts to be well-informed and wise about investing in highly risky

ventures such as the subprime mortgage market. After all, housing and

commercial property bubbles occurred all the time. And disasters

accompanied these bubbles all the time. But banks, major banks, seemed

unwilling to move into the housing market cautiously during the

1995-2005 skyrocketing of housing prices. The fear in the short-term of

missing out on the opportunity to gain huge profits from these risky

investments outweighed the fear of being left, in the long term,

holding worthless assets should the heady speculation cease. And thus

banks jumped greedily into the waiting catastrophe.

1A

mortgage owed by a family to a bank is considered a bank's asset,

because mortgage interest is a vital way that banks earn money. And,

after all, the house is also legally the bank's until the mortgage is

fully paid off.

2006 – Housing prices begin to drop for

the first time in eleven years

People are now hard pressed to find buyers for the houses they

cannot continue to afford

|

The September 2008 financial meltdown

Two of the biggest banks in the mortgage market

(holding about half of the mortgages on American homes) were actually

set up by the federal government to aid homeowners in securing

mortgages. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) was

created by President Roosevelt as part of his New Deal during the Great

Depression of the 1930s. The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation

(Freddie Mac) was established in 1970 to facilitate the buying and

selling of mortgages on the secondary market, freeing up money for

banks to be able to make mortgages more readily available to home

purchasers. Contrary to what is commonly believed, these are not

government-owned corporations; they are not (or were not) even

government-backed corporations. They are Government-Sponsored

Enterprises (GSEs) only. Ownership belongs to private investors, just

as with any other corporation. However, many people (including foreign

investors) invested in these corporations believing that they had the

full backing of the U.S. Treasury. As many would soon discover, this

was not the case, at least not originally.

Both GSEs had ventured deeply into the

subprime, Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM) market to keep their earnings

at the level they had been enjoying when the housing market first

heated up in the late 1990s. This all looked very good on paper. But

the fact is that by 2005-2006 both organizations found themselves

hugely overextended. By mid-2007 both of these huge mortgage companies

were in serious trouble.

By late 2007 there were clear signs that

the economy was slowing. The White House decided that what the economy

needed was some economic "stimulus" in the form of new tax breaks for

businesses and large tax rebates for American families (the Economic

Stimulus Act of 2008). In late January and early February Congress

authorized approximately $150 billion in such tax rebates. By late

spring of 2008 the benefits were out, and the economy picked up

(somewhat). But beneath it all was a waiting catastrophe.

The first signs of the looming

catastrophe came with the news that the huge investment bank, Bear

Stearns, was in deep trouble. It was terribly overextended in the

mortgage market, leveraged with debt it had accumulated to invest in

the wildly speculative housing market (it had borrowed about 30 times

as much as it had in real capital). White House economists scrambled to

find a buyer for the company. JP Morgan agreed to the deal, as long as

the government would lend $30 billion to cover the unwanted mortgages

portion of the deal. The company was saved, and a panic on Wall Street

was avoided, for a few months.

Meanwhile, attempts had been made in

previous years by the White House to reign in the speculation of the

two GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; but Democrats resisted these

efforts, defending these organizations as the hope of the little man.

But by mid-2008 the catastrophe hanging over both organizations was

obvious to all. Panic had set in among the mortgage speculators and

both GSEs were facing total collapse. In July, both organizations were

put under tight regulation, and the Federal Reserve was authorized to

step in to offer low interest rate loans to both organizations in an

attempt to restore confidence in them. But the crisis was too big. By

August of 2008 both organizations had lost 90 percent of their stock

values (as compared to their value the previous year). In early

September the government (the U.S. Treasury) had to step in to bail out

both institutions, to the tune of $100 billion of taxpayers' dollars

committed to each of these two institutions in order to get them back

on their feet. These were now in large part (temporarily, it was hoped)

government-owned. The bail-out saved the organizations, but seemed to

have little effect in stopping the panic. Investors were now scared

that other corporations that were over-leveraged in the subprime

mortgage markets were also facing failure.

By the weekend of September 13-14, the

panic was spreading as a major meltdown of the world of investment

banking. The panic hit the huge Lehman Brothers investment bank,

enormously overextended in the wild investment game. It was so

leveraged with its paper assets that it took only a 3 to 4 percent

decline in the value of those assets to collapse this prestigious firm.

But unlike Bear Stearns, no single purchaser could be found for this

long-established investment bank. On the following Monday the company

was forced to file the largest bankruptcy protection in American

history. The consequences were that this huge company had to be carved

up into pieces and sold to various other investment banks abroad,

principally Barclays of London.

The meltdown of the Lehman Brothers so

panicked Wall Street that the last two unregulated investment banks,

Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, whose own stock plummeted

dramatically in September, moved quickly to convert themselves into

traditional banks under the regulation of the Federal Reserve. However,

the famous investment banking and stock brokering firm Merrill Lynch

did not fare as well in the face of its own huge losses, and was

rescued from total catastrophe only when the Bank of America bought out

the company at a bargain basement price. But Washington Mutual,

America's largest savings and loan association, was not this fortunate.

After a 10-day run of people withdrawing their deposits from the bank,

it was taken over by the FDIC (the federal agency which insures

people's bank deposits), its banking subsidiary sold off cheaply to JP

Morgan and the holding company placed in Chapter 11 bankruptcy

protection. This panicked depositors and investors in the Wachovia

bank, the fourth largest American bank. It too was taken over by the

FDIC, and was eventually acquired by Wells Fargo Bank (with Citibank

competing for the purchase) as a joint banking merger.

Meanwhile the largest American insurance

company, American International Group (AIG), nearly self-destructed

when, because of a loss of $18 billion (mostly in the subprime mortgage

market), its credit rating was downgraded. This in turn caused a

panicked sell-off of its stock, to a point where the stock was traded

at only $1.25 a share – down from $70 a share the previous year! Again,

attempts were made to find a buyer for the company. But AIG was too

big. The Federal Reserve stepped in on September 18th to save the

company from extinction by offering a $85 billion taxpayer-funded

government bailout (that amount would be increased by the next year to

a total of over $180 billion). The net result was that the U.S.

government ended up owning (again, presumably only temporarily) 80

percent of this huge insurance company. This put an end to the panic.

But AIG subsequently was forced to sell off many of its subsidiaries in

order to begin to pay down that debt

|

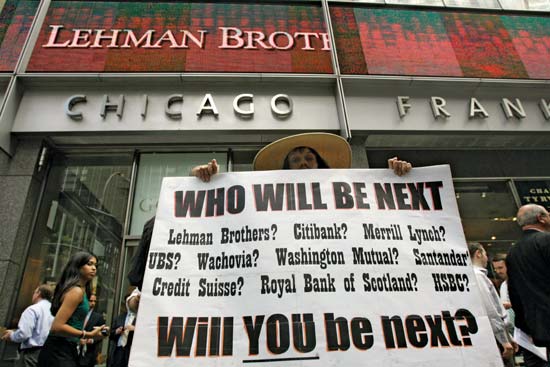

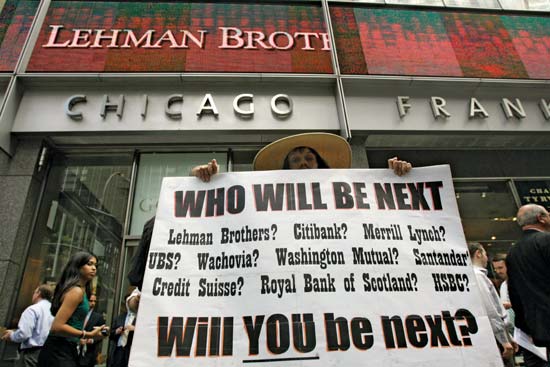

A protest in front of the Lehman

Brothers headquarters in New York

Lehman Brothers CEO

Richard Fuld heckled by protesters upon leaving Capitol Hill – October

2008

TARP: BUSH MOVES TO BAIL OUT THE TROUBLED FIRMS |

|

Bush's TARP (Troubled Assets Relief Program), October 2008

In late September President Bush introduced a

financial bill into Congress called the Emergency Economic

Stabilization Act of 2008. This bill authorized the U.S. Treasury to

extend to various financially distressed firms (especially the

country's largest banks) available loans totaling $700 billion, termed

the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP), to purchase some of the

assets of these companies in order to restore investment confidence in

them. Fears of there being another stock market crash along the lines

of the crash of 1929 if action were not taken immediately were

circulated in an attempt to draw support for this bill from a reluctant

House of Representatives heavily loaded with most Republicans (and many

Democrats) who fervently believed that the government had no right to

get involved with American business.

But despite extensive White House efforts

to line up the necessary support, the bill failed to pass on September

29th when put to a vote: 205 in favor (Democrats 140; Republicans 65),

228 in opposition (Republicans 133; Democrats 95).

However, the scenario of another Great

Depression in the making became more believable when immediately after

the House vote the Dow Jones stock market averages showed a loss of 777

points, the largest single-day loss (up to that point) in the history

of the stock market.2

$1.2 trillion had been lost in stock value in less than three hours!

Two days later the Senate moved on the bill (heavily amended with

"extras" designed to sweeten its provisions), approving the amended

version of the Act, 74 to 25. It then returned in its amended form to

the House where on October 3rd it was finally approved 263 in favor

(Democrats 172; Republicans 91) to 171 opposed (Republicans 108;

Democrats 63). Only hours later Bush signed the bill into law.

This set an interesting precedent – as

some would term it, a "moral hazard" – that somehow it was the

government's job to rescue the capitalist market, in particular firms

that were too big to fail when these companies messed up with bad

investment decisions. True, the TARP very likely would pay for itself

in the long run, presuming that most of these troubled firms recovered

and the government could sell off its holdings in these companies. But

this event provided one more occasion, one more precedent, where the

federal government saw that it had to expand its involvement into new

areas of American life. It had to be the governing backup to the

American economy.

The 2008 bail-out of the American automobile manufacturers

It was not just the American banking

industry that had fallen into trouble in 2008. America's "Big Three"

(Ford, General Motors and Chrysler) auto manufacturers were in trouble,

especially GM and Chrysler. The manufacturers' production capacity was

17 million cars a year; in 2008 the production rate had dropped to only

10 million cars. One of the reasons for the drop was that car purchases

were often financed through second mortgages secured on homes (2

million cars were financed that way in 2007). But with the mortgage

banking crisis in 2008, those types of loans were very hard to obtain.

Also the automobiles of the Big Three were becoming more expensive than

foreign models, because the costs of health care and pensions for an

older work force had to be passed on to the consumer, while at the same

time foreign manufacturers producing their models in the United States

operated with a younger (and largely non-union) work force and thus

cost the foreign manufacturers less in terms of health and pension

costs. This allowed their models to be sold for less than similar Big

Three models. Thus foreign models were taking a larger market share. In

1998 the Big Three accounted for 70 percent of the auto market. By

2008, only ten years later, that figure had dropped to 53 percent.

Another problem was that the Big Three tended to want to manufacture

SUVs and pickup trucks, where the profit margin was much larger (about

15 percent to 20 percent profit on each vehicle), rather than smaller

sedan type car (only about 3 percent profit per vehicle). But the price

of oil had been climbing, and so also gasoline prices at the pump,

reaching $4 per gallon in 2008, causing consumers to back away from the

purchase of the gas-hungry SUVs.

By mid-2008 the panic that had set in

concerning the value of the mortgage banks was also reaching to the Big

Three auto corporations. During the previous several years, GM had been

registering an operating loss which was growing with each year ($10.6

billion loss in 2005; $38.7 billion loss in 2007). By mid-2008 its rate

of sales compared to 2007 were down by 45 percent, and its reserves

that it was drawing from to pay workers' benefits and pensions were

almost completely gone. In mid-November of 2008, representatives of the

Big Three went to Congress to plead for government loans totaling $25

billion to keep their companies from going bankrupt. Republicans were

inclined to let the companies fall into bankruptcy, for this would let

them restructure and get out from under all the expensive workers'

benefits they were forced to accept by the unions. However, Democrats,

fearful of the loss of millions of jobs in the automotive industry,

advocated for an immediate bailout. Meanwhile the shares of the auto

companies dropped away drastically on the stock market.

Finally, after both management and labor

agreed to a reduction in salaries and benefits, an immediate bailout of

$13.4 billion in federal loans and an additional $4 billion early next

year was offered the industry by Congress and Bush out of the TARP fund

(which drew strong criticism as that was supposed to be only for

financial institutions). Along with this went the demand that the

companies had to seriously restructure, before any other TARP funds

would come their way.

2On

March 10, 2020, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by 2000 points on

that day alone, caused by the panic that developed over the spread of

the Coronavirus, which was impacting the world, and making its way

towards America.

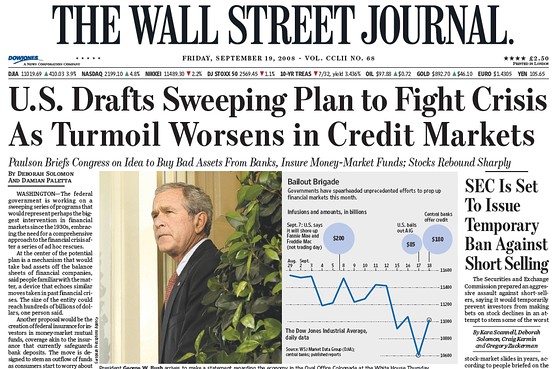

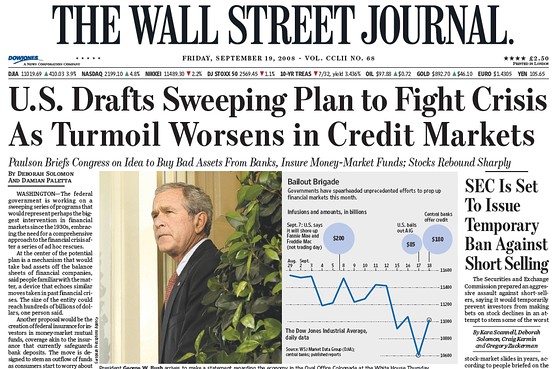

| September 29, 2008 – Treasury

Secretary Hank Paulson (with Federal Reserve chief Bernanke at his side) begs Congress to authorize the

$700 billion corporate bail-out package (the "Paulson Plan"). Congress's first answer

was a "no" ... which immediately plunged the Dow 778

points – the worst single-day loss in the history of the New York's Wall Street stock

market (at that point).

|

|

Bankers (who were literally forced to take

the government bailout) appearing before Congress – February 2009: CEOs Lloyd Blankfein (Goldman

Sachs), Jamie Dimon (JP Morgan Chase), Robert Kelly (Bank of New York Mellon),

Vikram Pandit (Citigroup), John Stumpf (Wells Fargo). Other banks targeted

for the Government's $125 billion stock purchase of their' preferred stock were State Street,

Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley

|

Another car dealer having to go out of

business Another car dealer having to go out of

business

Go on to the next section: On-Going Cultural Conflict

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

The growing national debt crisis and

The growing national debt crisis and The growing income inequality in

The growing income inequality in The September 2008 financial meltdown

The September 2008 financial meltdown

TARP: Bush

moves to bail out the

TARP: Bush

moves to bail out the