26. BUSH (II) FUMBLES THE BALL

ONGOING CULTURAL CONFLICT

ONGOING CULTURAL CONFLICT

The Federal courts help to establish

The Federal courts help to establishSecularism as the nation's religion

Thus the

battle over the appointment of

Thus the

battle over the appointment of

new Supreme Court justices

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume Two, pages 386-392.

THE FEDERAL COURTS HELP TO ESTABLISH SECULARISM AS THE NATION'S RELIGION |

|

During the Bush years Boomers reached the age where they would begin to enter the ranks of federal judges, giving them the chance to put their cultural instincts into play as law, law entered into force by simple judicial decree. To these new judges the law was "whatever" they felt it ought to be – in light especially of how they were inclined to read the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The Boomers had never been fond of their parents' dedication to Christianity and had fought long and hard to put Christianity under the restraints of Secularism. As the Boomers saw things, the First Amendment was about the people's right of free speech, press and assembly, that is, protection from dominance or control by the state. But when it came to religion, the issue was viewed the other way around. As the Boomers understood the First Amendment, the "separation of church and state" was meant not to protect religion from dominance or even influence by the state, but rather to protect the state (meaning all public life) from dominance or control by their parents' religion. Interesting, but not anywhere near what the original authors had intended by the First Amendment. But there was more than just the Christian religion itself that Boomer federal courts felt that they must confine or restrict. The Christian moral legacy, the Christian worldview, the Christian view on the value of life itself, came under strong Boomer challenge. Even when the people themselves voted in state plebiscites, or when Congress, reflecting the spirit of the majority of the nation, passed legislation reflective of the continuing influence of this Christian ethic, the simple decree of a federal judge (usually with the help of the ACLU as the typical counsel for the anti-Christian plaintiff) could strike a deadly blow to the heart of such legislation. All judges had to do was to cite the Fourteenth Amendment, claiming that the particular law as voted on by either a legislature or by a popular referendum deprived the complainant of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law, or denied them the equal protection of the laws. "Due process" and "equal protection" were concepts that had the wonderful quality of meaning anything that the judges wanted them to mean. All that they had to do was to decide that the complainant had some particular prior rights that had been taken away from them by the law. A famous case pointing out how far the federal courts were able to go in re-legislating federal law was the Newdow v. U.S. Congress case. In 2000 Michael Newdow brought suit against the local school board for requiring his daughter to recite the pledge of allegiance, which includes the words "under God," stating that this portion of the pledge was in violation of the Constitution's establishment clause. The U.S. Magistrate and Federal District Court claimed that the pledge did not violate the Constitution. Newdow then appealed the decision to the very Liberal Ninth Circuit Court. Unsurprisingly, a panel of three Liberal judges in 2002 sided with Newdow. Their view was that the phrase was placed in the pledge for distinctly religious reasons by President Eisenhower and the U.S. Congress in 1954, quite in violation of the Constitution's non-establishment clause. This decision of the Ninth Circuit Court drew a strong reaction around the country. 150 members of the House of Representatives gathered in front of the Capitol building to pledge allegiance as a sign of support for the pledge as it reads; the Senate passed nearly unanimously (one person absent) a resolution affirming its support of the pledge. Soon thereafter the child's mother filed a complaint with the Court, pointing out that she alone had legal rights over the child, the father did not. Her daughter was fully Christian and the father's intervention could prove harmful to the child. The Ninth Circuit Court, in order to protect its original decision, answered that the father, though he did not have legal rights, did have paternal rights and therefore he possessed the same right as the mother to have his (atheistic) views presented to the child as she did her (Christian) views. Then the following year, Newdow was awarded joint legal custody over his child, clearing away the objection that he had no legal right to present the case. The Case then went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in March of 2004 presented the decision that since Newdow did not have legal custody at the time the case was presented, his case before the Ninth Circuit Court was not valid. Thus the Ninth Circuit Court's decision was overturned for technical reasons, although several of the Justices wrote separate opinions supporting the idea that the pledge did not violate the Constitution. Another version of the pledge case again

came up for action by the Liberal Ninth Circuit Court in 2005, and

again the Court declared that the pledge was unconstitutional. This

decision was then appealed by the Becket Fund in December 2007. The

Becket Fund's most telling argument was that "under God" had long been

in U.S. history a concept that protected rights, not denied rights; the

long tradition in American politics was that the rights of Americans

"are not given to us by the government, but by a source higher than

the government."1 Meanwhile, Newdow moved his anti-pledge

crusade (supported by the Freedom from Religion Foundation) to New

Hampshire in October 2007. Here too the Becket Fund took up the

challenge on behalf of the New Hampshire public schools. Finally in 2010 the federal courts came to a decision on the matter. In March the Ninth Circuit Court finally upheld the constitutionality of the pledge, and in November the First Circuit Court (Boston) also affirmed the right of the New Hampshire public schools to recite the pledge. Another case that demonstrated the way the federal courts attempted to set the moral cultural agenda of the country occurred in the U.S. District Court of Judge John Jones III. On December 20, 2005 Jones issued his decision and supporting findings in the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District case. This case concerned the Dover Pennsylvania School Board's requirement that beginning January 1st 2005, 9th-grade science teachers should read a short four-paragraph statement that advised that Darwin's theory of evolution is indeed just a theory and that Intelligent Design is an alternative explanation that students might want to explore in the book Of Pandas and People. The decision to require the reading of this short passage had been bitterly fought within the school board during its deliberations on the matter in October and November of 2004. And when the Board voted its approval, 6-3, the three opposing School Board members resigned in protest. By the next month, December, the ACLU and eleven parents from the District had filed suit in the District Court to prevent the requirement of this reading of the passage from going into effect. Judge Jones's decision the following

December (2005) was that "it is unconstitutional to teach ID

[intelligent design] as an alternative to evolution in a public-school

science classroom." His explanation was that ID was a religious view,

and not science, because it violated a centuries-old ground rule of

science by invoking supernatural causation. ID was in fact nothing more

than creationism in new clothing, which the Edwards v. Aguillard

case back in 1987 had made amply clear was unconstitutional. Jones was

annoyed at the defenders of ID, claiming that they had used lies,

illogic and disingenuous argumentation (pretending that ID was not

simply creationism in disguise) to promote their case. He assessed the

actions of the School Board by stating:

This line of thinking automatically forbids any consideration of the origins of the universe and of life on this planet except in atheistic terms. To close off consideration that creation might have started with some kind of "intelligent design" and to insist that creation resulted only through a natural process of random accident is itself to force a Darwinist article of pure faith, not science, on all learning. The fact that the District Court chose to accept as scientific truth this article of faith presented by the experts of these strongly pro-Darwinist organizations was to enter into a realm considerably beyond its judicial capacity. But nonetheless that is exactly what Jones did. He personally decided what was science and what was not. On the other hand, the Foundation for Thought and Ethics (FTE), a very respectable organization of scientists and scholars who had quite compelling arguments against pure Darwinism, wanted to present its findings in answer to the experts brought in by the ACLU, AU and the NCSE. Judge Jones denied their request, even though the FTE's publication Of Pandas and People was widely discussed in the course of the trial and FTE should have been allowed to answer the discussion. But not only did Jones apparently know early on how he wanted to resolve this case, he also knew that he was developing a landmark case and wanted to make sure that everyone got the point. There was to be no more such sneaking of creationist religion into the classroom through the guise of Intelligent Design.

In the end, the Dover Area School District, made up of new members (the

six defendants in the case having been voted out of office by the Dover

voters in November 2005 just prior to the court decision), had to come

up with one million dollars in legal fees and damages due the lawyers

in the case. This too made the point quite clear. As Richard Katskee of

the AU put matters in the NCSE's February 24th, 2006 newsletter:

1(becketfund.org/ index.php/case/131) 2The

financial penalty was enormous. But the AU felt that it was being

charitable in asking only for $1 million in settlement. The AU had this

to say on its website concerning the case:

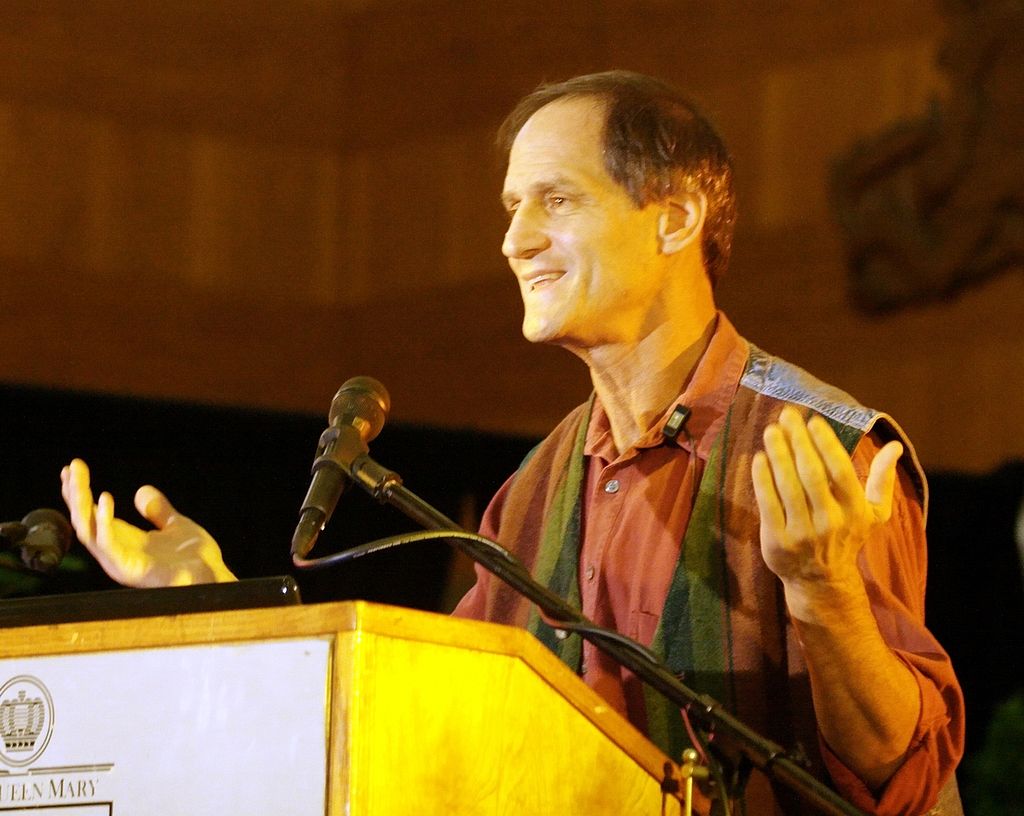

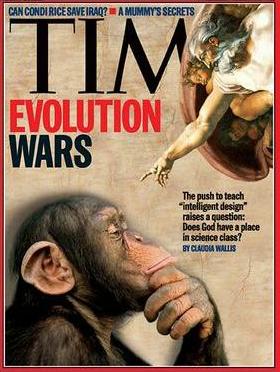

Newdow speaking at the Atheist Alliance International Convention in Long Beach, California, 2008   The reaction of Time Magazine The TV program NOVA

|