5. THE YOUNG REPUBLIC

GETTING STARTED

| CONTENTS

George Washington takes the helm George Washington takes the helm

Alexander Hamilton as Treasury Alexander Hamilton as Treasury

Secretary

Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State

Foreign policy problems Foreign policy problems

John Adams takes command (1797) John Adams takes command (1797)

The "midnight" judicial appointments The "midnight" judicial appointments

Life settles in nicely at home in the new Life settles in nicely at home in the new

Republic

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 174-191.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1780s |

The beginning of a period of major change ... in both America and France

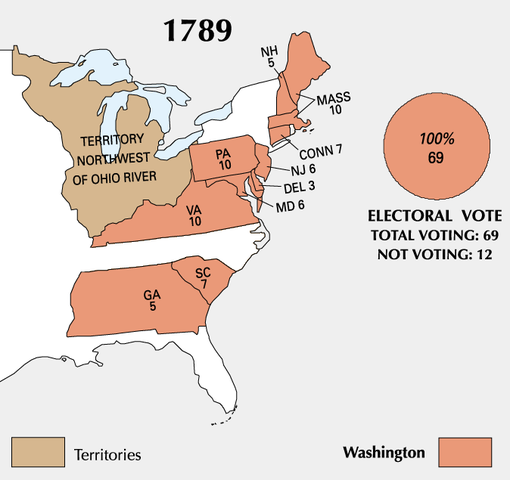

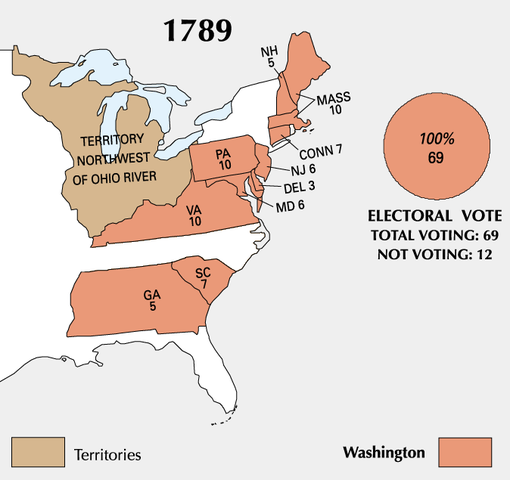

1789 Washington inaugurated in New York as the first U.S. president (Apr)

The French Revolution breaks out (Jul)

spurred by the ideals of the Enlightenment ... and the example of the new American Republic

|

| 1790s |

The Republic struggles to establish new (and hopefully viable) political norms

early 1790s Mounting political feud rises in Washington's Presidential cabinet between Treasury

Secretary

Hamilton (Federalist) and Secretary of State Jefferson

("Republican"/strong states-righter), with

Washington generally supporting Hamilton (to Jefferson's great ire)

1790 Hamilton announces a new national bank’s "assumption" of all public debt (national and state);

Jefferson and his

political ally Madison are strongly opposed to this centralizing of

economic power

1791 Congress approves Hamilton's plan for a US Bank and the plan for central financing of the public debt

The states ratify 10 Constitutional

Amendments (Bill of Rights), guarantying key political protections against the

unlimited growth of central (or ‘national’) governmental power

1793 The French Republic has alienated all other European monarchies; all of Europe is again at war

The political hostility between

Hamilton (pro-British) and Jefferson (pro-French) deepens

Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality is a rather pro-British position

"Citizen Genet" is welcomed by Jefferson as French

Ambassador but proves to be an unwelcome meddler in American politics

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Jay in the Chisolm v. Georgia case affirms that a citizen has the right to sue a state government in a federal court

1794 As an immediate reaction to the Chisolm case, the 11th Amendment is added to the Bill of Rights, affirming the immunity of

the states from such lawsuits (unless a state agrees to a hearing)

The French Republic dissolves into a state of unbounded political slaughter (the "Reign of Terror")

Massachusetts farmers rebel against

Hamilton's excise tax on their whisky production; Washington personally leads a

13,000-man army to swiftly crush the "Whiskey Rebellion"

The Jay Treaty seems to surrender

American maritime rights to the increasingly aggressive English

The cotton gin is invented, vastly

deepening the importance of slavery to the Southern economy

1796 Washington steps aside, serving only 2 terms (and glad to be going home to his farm), ... establishing a tradition

of a peaceful transfer of limited presidential power (to John Adams)

1798 French aggressions on the high seas lead arch-Federalists to want to go to war with France (and to political war with

the pro-French Jeffersonian Republicans ... with the Alien and Sedition

Act)

Adams agrees to a

treaty with the French, thus avoiding war, but getting him no gratitude

from the Republicans and costing him

the support of a number of arch Federalists (and re-election in 1800)

|

| 1800s |

The Federalist / Republican rivalry deepens

1800 The American capital is moved to Washington, D.C., a town mostly yet an ideal rather than a reality

Jefferson is narrowly elected President

(over Burr); Adams is humiliated by his loss

1801 As his last act in office, Adams signs the midnight judicial appointments, including John Marshall as Supreme Court Chief Justice; Marshall will greatly expand the powers of the Federal judiciary branch (1801-1835)

|

GEORGE WASHINGTON TAKES THE HELM |

|

Although the young American republic had a new Constitution, it was a

very slender affair outlining very little of what we have come to understand

today as government. That was just as well. Its brevity sufficed to bring

renewed unity to the competitive-minded states, and its vagueness in detail

left exactly just those details to be developed by the individuals who would

take their place as officers of the new republic.

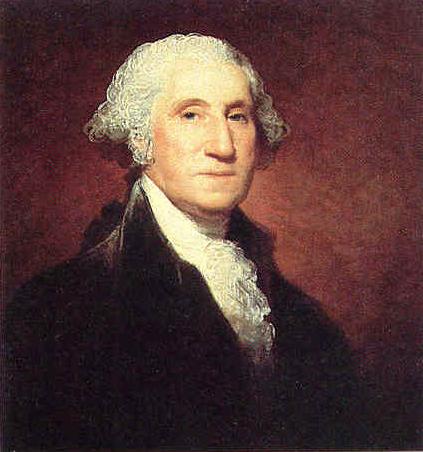

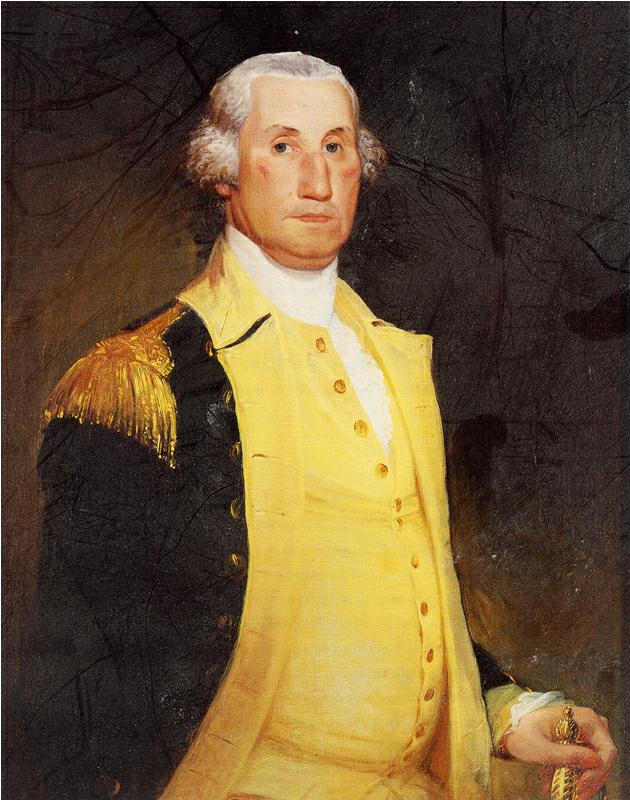

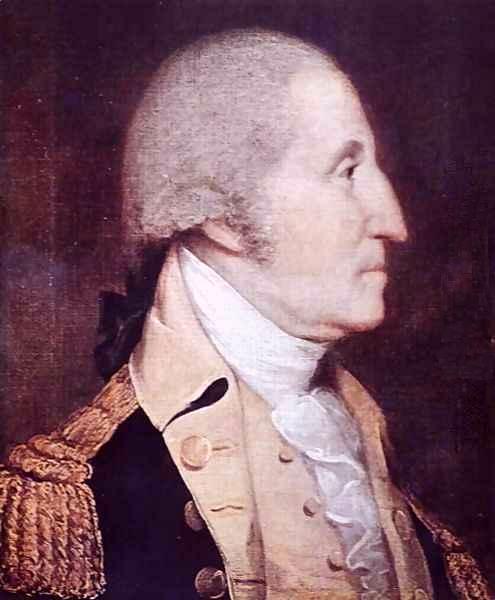

George Washington

It was understood and expected by all (except

perhaps by Washington himself who, after the war, was looking forward to

ending his public duties and heading back to his farm at Mount Vernon to

enjoy a less frustrating set of labors!) that the person to lead the republic as

its new president was to be George Washington. After some soul-searching

he once again yielded to the call of duty when it was apparent that no one

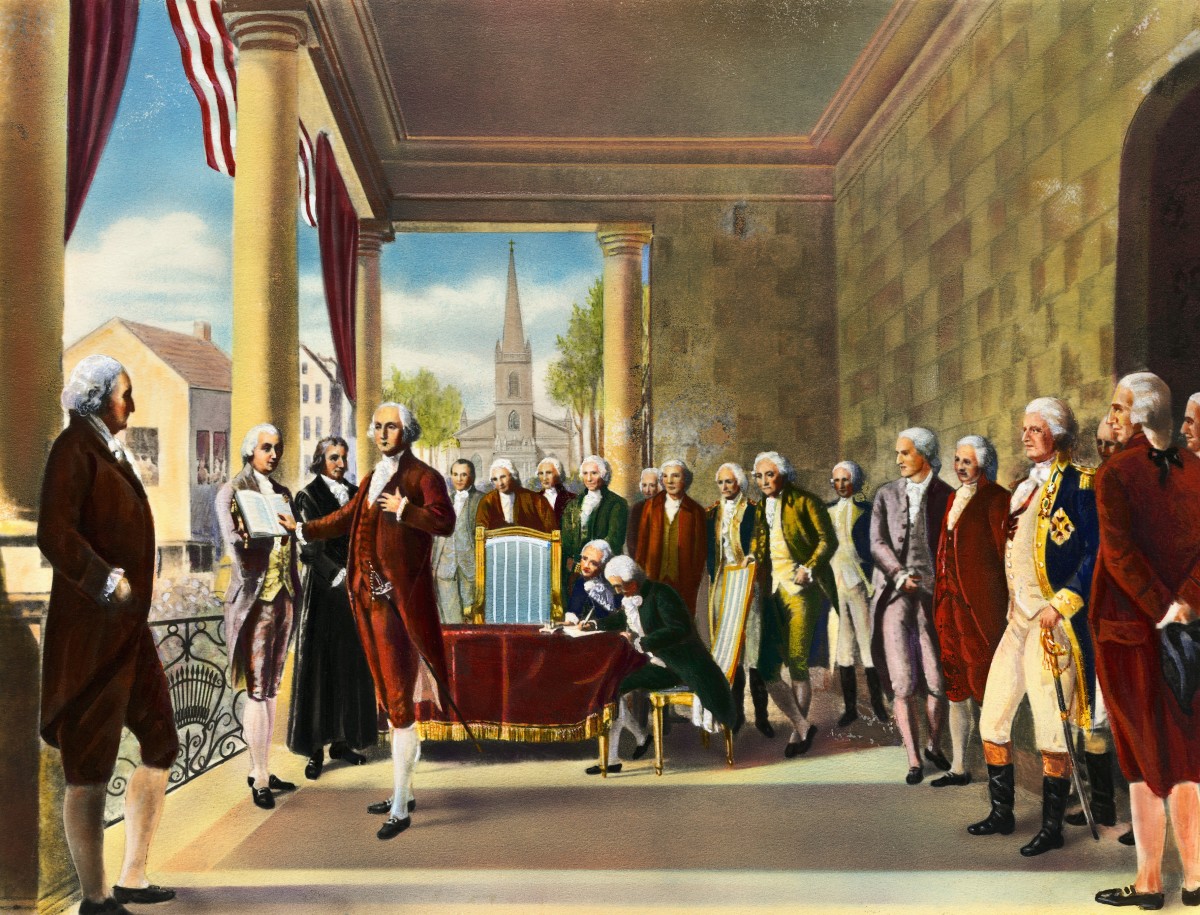

else but he was expected to be the country's new leader. Thus on April

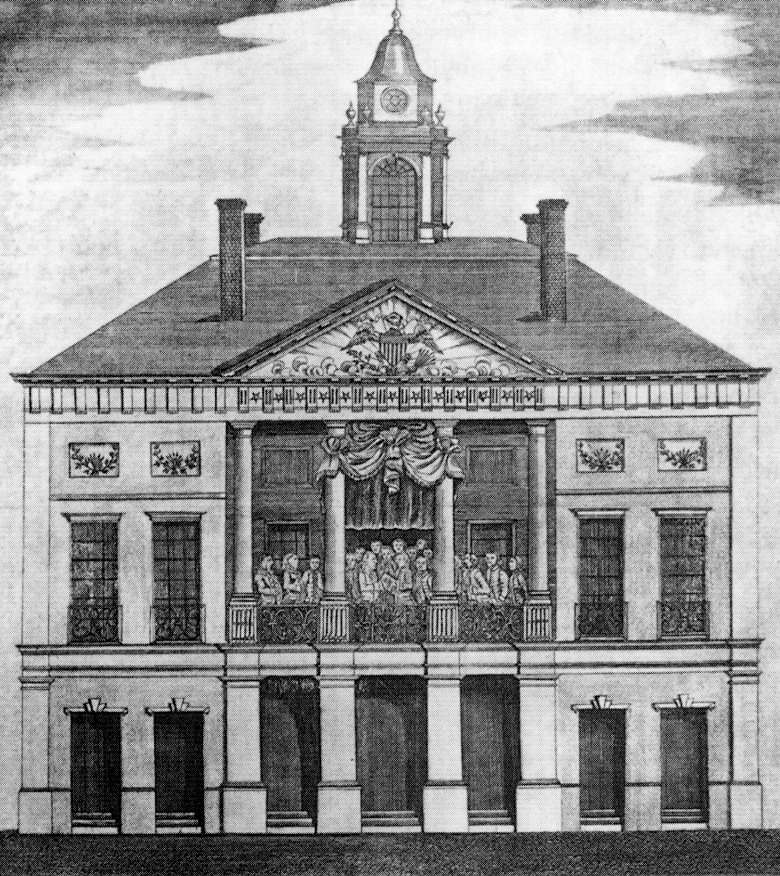

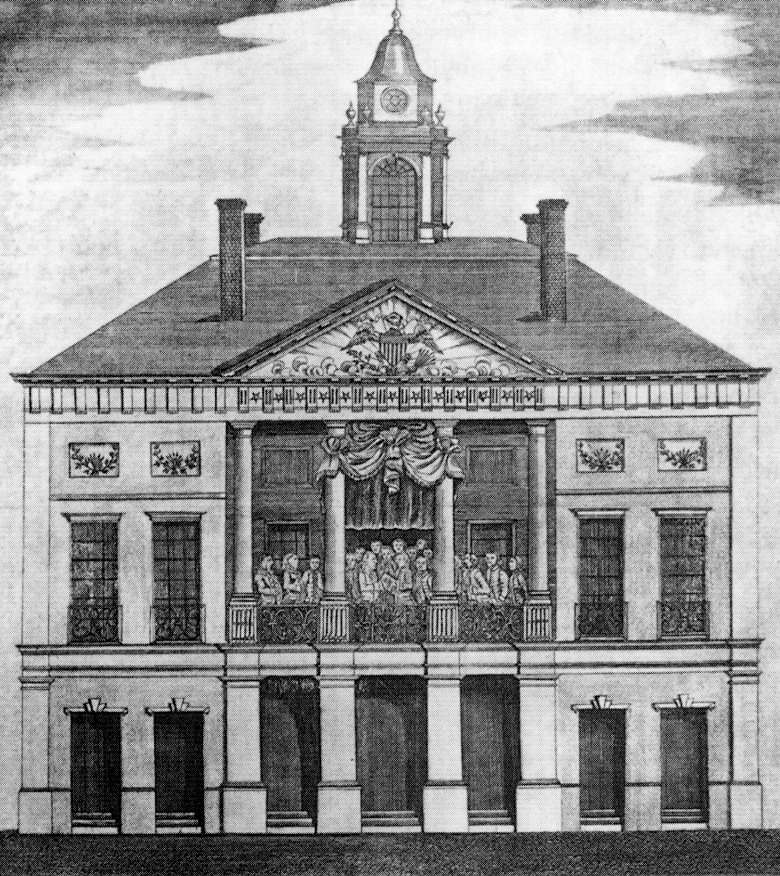

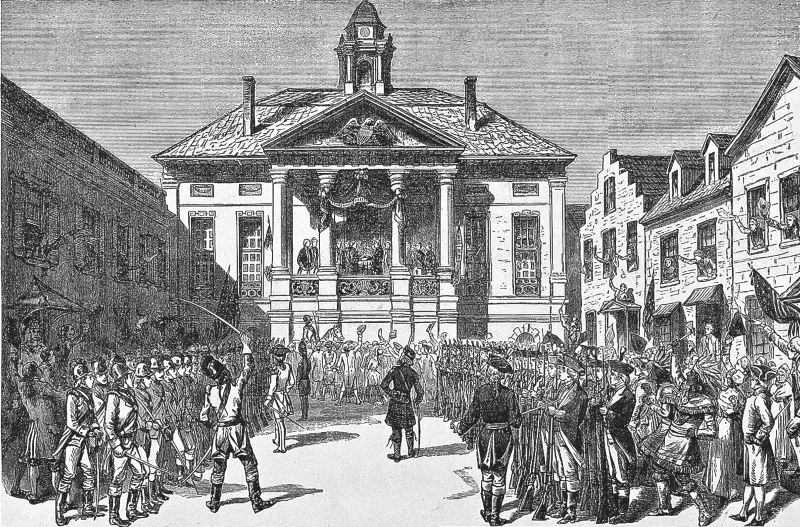

30th, 1789, he stood on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City to take

the oath of office as the republic's first president.

How would he handle the office? There were a multitude of problems

facing the new Republic, none of them particularly military (at least for the

moment) and so his sole experience as a military officer would not give

much indication as to how he would handle the challenges of civil office.

The Constitution mentions only that a president is chosen for a four-year

term, but elected officials in the colonies could be, and frequently

were, repeatedly returned to office with a new election. Would he leave

after serving only four years? Would he want to stay on repeatedly, like a

monarch, ruling until he drew his last breath? Some bitter Anti-Federalists

even claimed that Washington would try to make himself king – although

those who knew him well were quite aware that this would have been the

last thing Washington would have wanted for himself.

In any case, how would he get things started as

president? What kind of legacy would he leave for others to live up to

and develop?

The answer came quickly as he gathered together a

small group of advisors to whom he could assign particular functions, a

group or council similar to the British royal cabinet. Although the

Constitution mentions no such institution, Washington, and all

presidents after him, chose to make very important use of a cabinet of

officials, some serving as personal advisors and some serving as heads

or secretaries of government institutions that American presidents have

long used to administer the office of president.

|

George Washington – by Gilbert

Stuart

National Portrait Gallery

- Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

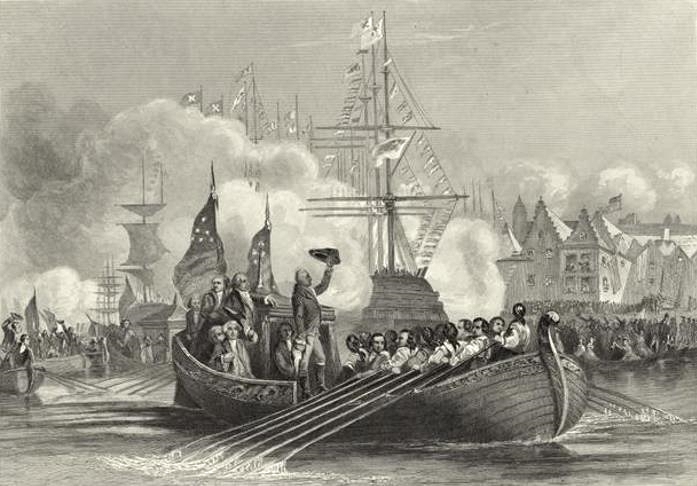

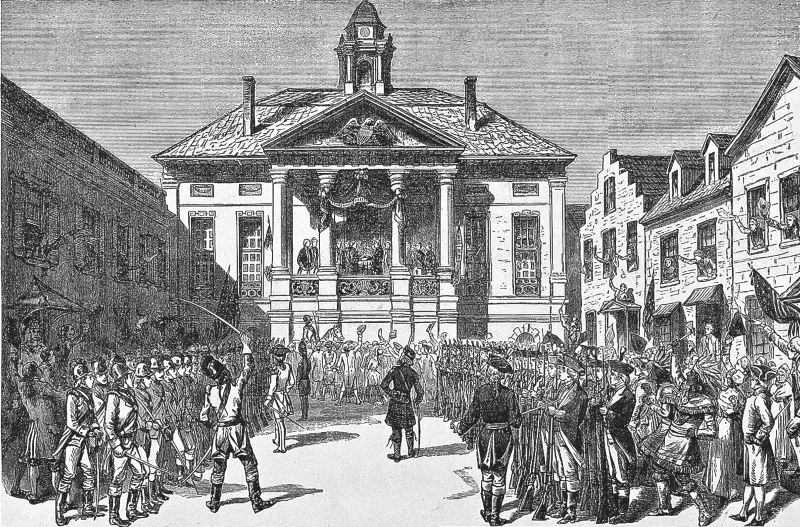

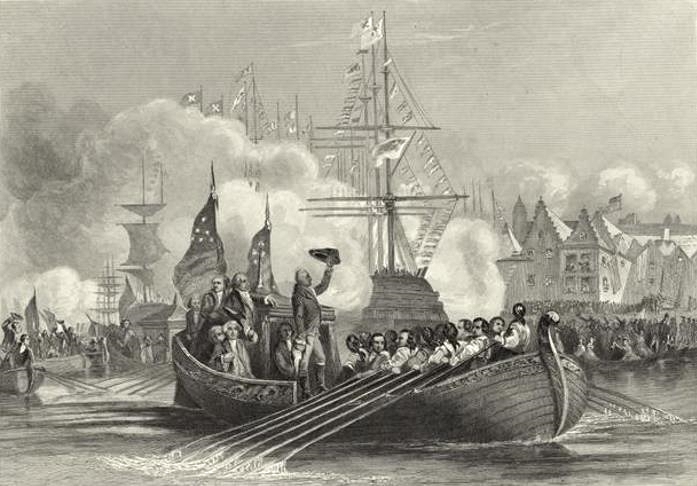

Washington receiving a naval salute upon his arrival at New York City

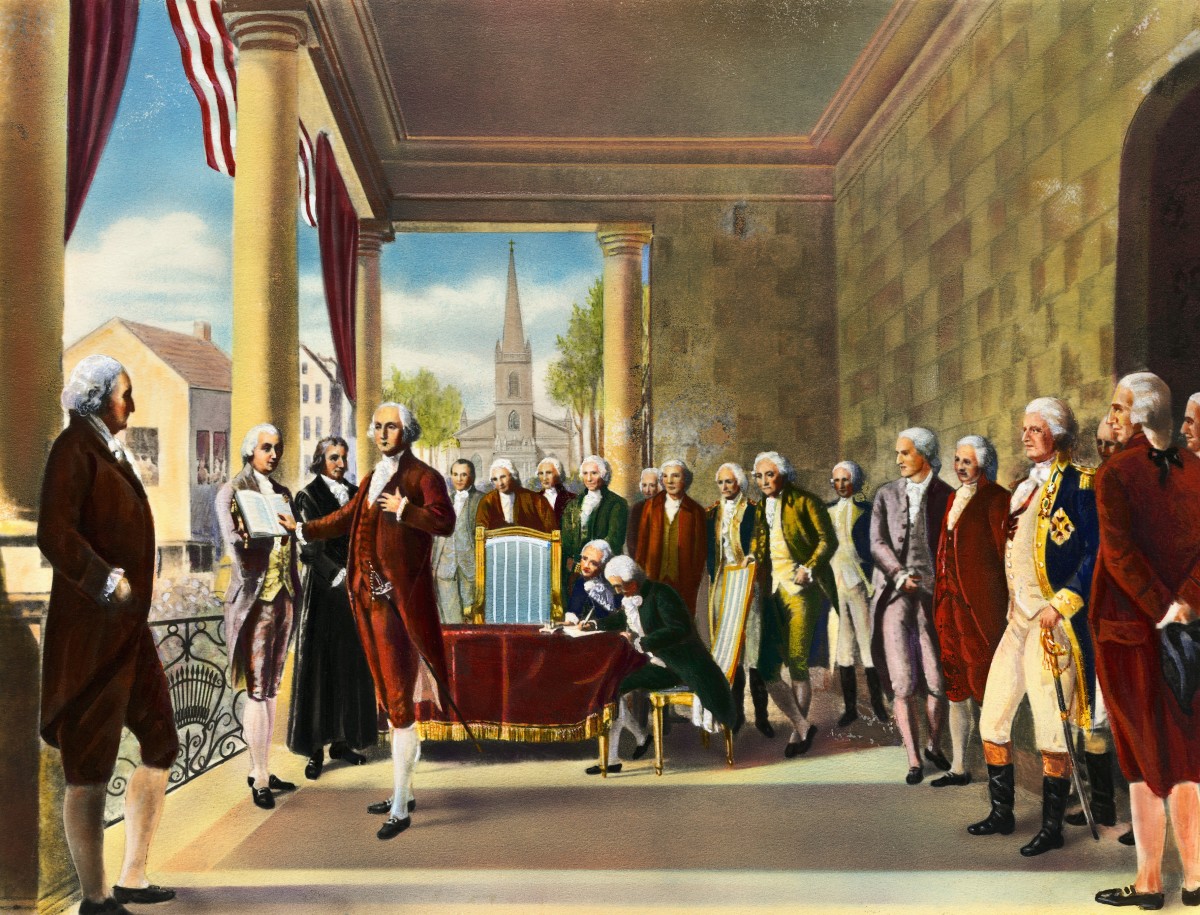

Washington takes the Oath of Office (April 30, 1789)

George Washington – by Joseph

Wright (both portrait and profile)

Washington's Cabinet

ALEXANDER HAMILTON AS TREASURY SECRETARY |

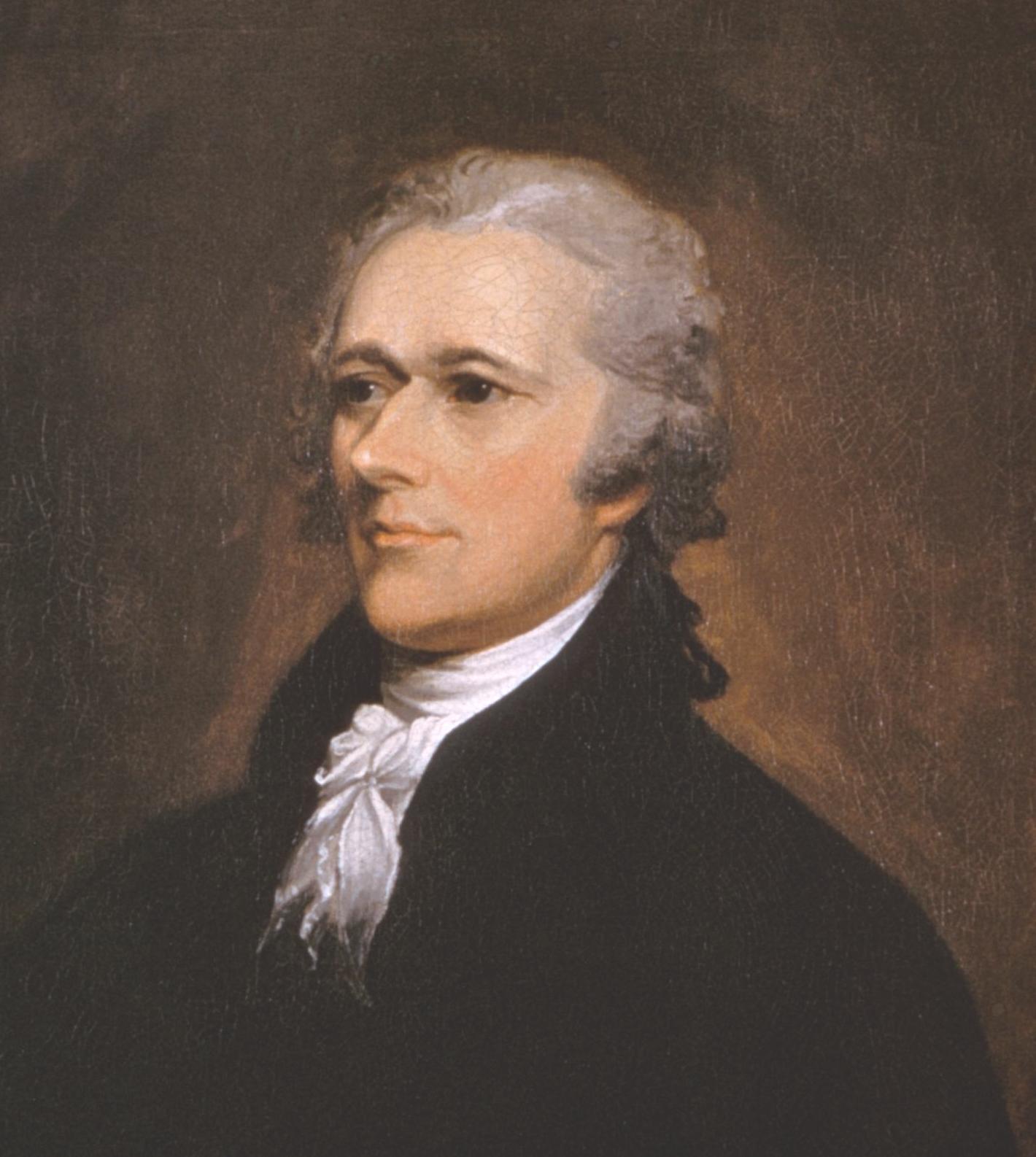

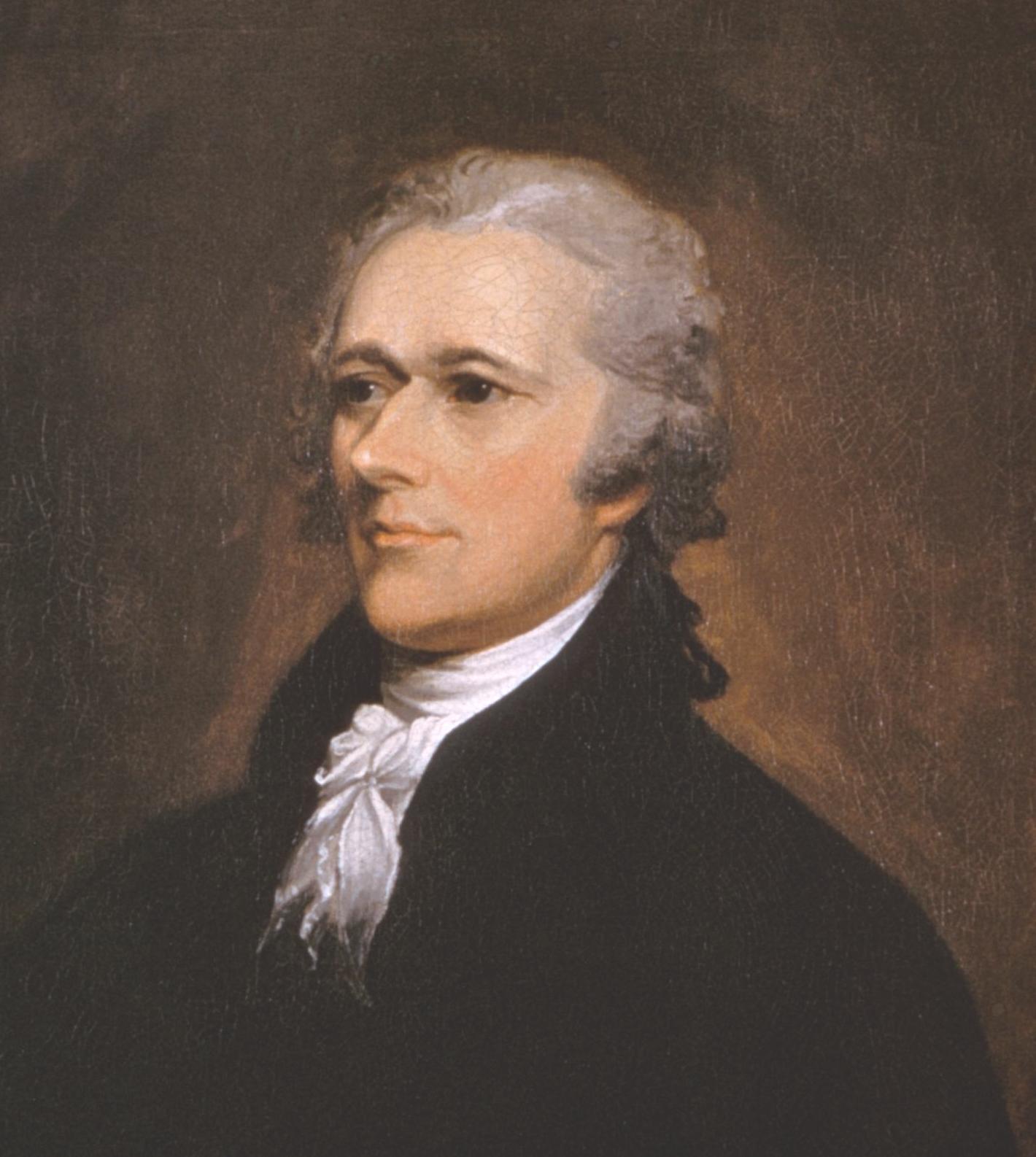

Alexander Hamilton – by John

Trumbull (1806)

National Portrait Gallery

- Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

|

Alexander Hamilton

Once

again, Washington called on the one person he trusted most for hard

work and natural brilliance of mind (and bravery), the one person he

had relied on, time and time again, in the years of the War: Alexander

Hamilton. With the financial status of the new republic being the new

Union's biggest challenge, Washington was quick to assign Hamilton as

the United States' first secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton was actually born (year uncertain) not in

one of the American colonies but in the Caribbean, under peculiar

family circumstances (that would be the object of much commentary by

his later political enemies) and was forced to look after his own

survival at a very early age.1 But he was a very avid reader,

bi-lingual (English-French), and a self-educated apprentice clerking

for a local merchant (possibly his actual father), and at seventeen

wrote an essay published in the local newspaper. The essay was

sufficiently impressive that it led local community leaders to gather a

fund to send Hamilton off to New Jersey in 1772 for formal education

(prep school). In 1773 he began his studies at King's College (Columbia

University) in New York, where he quickly distinguished himself as an

excellent orator supporting the colonies' growing spirit of rebellion

against British royal authority. Hamilton also wrote at the same time a

number of outstanding articles and essays in support of the same cause.

Yet he was also of a cautious or fair mind

(perhaps because of his own sufferings as a youth) and in May of 1775

came to the defense of the college president, allowing the man to

escape an angry mob, while Hamilton challenged the mob not to attack

Loyalists or their cause in this manner.

However, Hamilton was himself quick to take up

arms and join with friends in the New York militia, undertaking at the

same time (again, on his own initiative) the study of military history

and military tactics – and soon put that knowledge to use in leading a

raid on a supply of British cannons in the Battery! He then went on to

organize his own artillery company, elevating himself thereby to the

rank of captain. His company soon joined with Washington's troops in

the various battles that raged across New York City, and then across to

New Jersey, where his artillery kept the Hessians under fire at the

Battle of Trenton.

His talents were quickly recognized, and he was

asked by various generals to join their staff. Yet he understood that

glory was to be found on the field of battle, not on the general staff

of a commanding general ... that was until Washington made the same

request. That was an offer that Hamilton was willing to accept. And

this changed his life, and America's, forever.

As chief of staff he was assigned the task of

maintaining written communications with the Continental Congress, the

governors of the new states, and with other generals. Over the course

of four years, as Washington's confidence in Hamilton became virtually

total, Hamilton himself issued detailed military instructions to

officers under Washington's command, and supervised both diplomatic and

intelligence operations coming from Washington's command. Thus it was

that he met French General, the Marquis de Lafayette, and became close

friends with him in the process.

Finally at Yorktown, Hamilton's long desire to

actually serve directly under fire, came into play – with Washington's

very hesitant permission! It was Hamilton himself who led the American

attack on one of the two vital redoubts still holding the British line

in the latter's desperate defense at Yorktown. It was a brave, but

probably very foolish, move on Hamilton's part. But he obviously

survived, adding even more to his enormous stature in the eyes of

Washington.

After the war he formed a law partnership with a

friend and found himself, among other things, defending Tories who were

suffering from the post-war anti-British backlash, typical of his sense

of fairness. But he was nonetheless very interested in seeing his new

Republic move forward into its own distinct future, and thus in 1784

founded the Bank of New York, the beginning of his entry into the world

of large-scale financing.

He was as interested in the political future of

the country as its financial future and two years later attended the

Annapolis Convention, drafting the resolution which called for the

Constitutional Convention that eventually produced the U.S.

Constitution. The next year he became an assemblyman in the New York

State Legislature, which sent him as one of its three representatives

to the Convention in Philadelphia. And of course it was he who wrote

most of the articles that formed the famous Federalist Papers, advocating the adoption of the new Constitution.

Washington had not forgotten Hamilton and the

military service he had performed for him. He knew Hamilton to be

intensely loyal personally, intensely brave, intensely intelligent,

intensely competent, and intensely dedicated to serving his newly

independent country. And so it was that Washington turned to Hamilton

to see what Hamilton could do to help him put the new country on a

strong financial footing. Thus he asked Hamilton to become his

secretary of the treasury.

Hamilton's debt assumption program

As it

had always been during the war, one of the biggest problems facing

Washington and the struggling young Republic he was expected to lead

was money. Always money! By war's end, the Continental Congress had run

up a $54 million debt, and the states an additional $25 million. Also,

the promissory notes or bonds issued during the war by the Continental

Congress, by the various states, and by the army had been bought up by

speculators after the war at fifteen cents on the dollar. Most people

believed that they were not worth even that much. In other words, the

creditworthiness of the Republic was almost nil.

Hamilton however had some well-developed ideas as

to how he wanted to meet that challenge. He proposed to Congress

(January of 1790) a method of clearing the debt by what he called

assumption: the federal government would assume all of the debts and

begin the process of repaying them – at full value! America would pay

its debts. The world could take confidence in that. It was indeed

financial confidence that Hamilton was trying to restore. To meet this

obligation, the Republic would itself borrow (issuing its own

promissory notes or bonds) to cover the debt through bonds issued by a

newly created national bank: the Bank of the United States (BUS).

Besides financing the repayment of the national debt, principally

through heavy taxes on imports, the BUS would also fund public economic

infrastructure projects and private industrial investment for national

development.

1His

mother was married but separated from another man when she met and

married (thus illegally) James Hamilton, Alexander's presumed father.

When her legal status was brought to light, James left her and young

Alexander. Then when Alexander was only thirteen his mother died,

leaving Alexander an orphan.

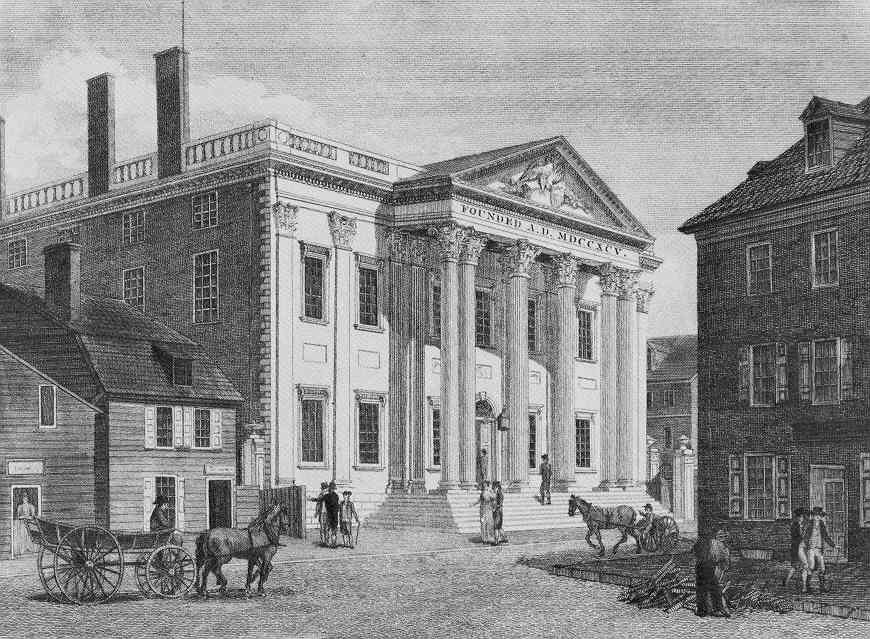

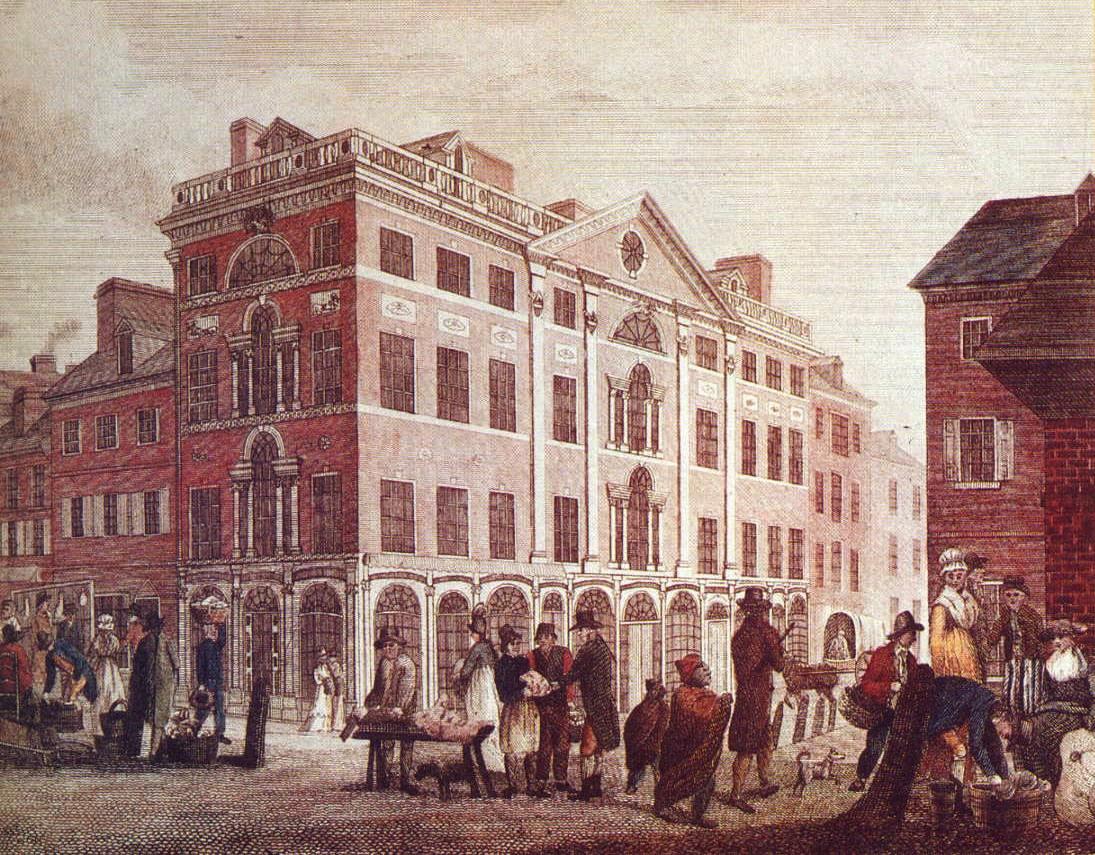

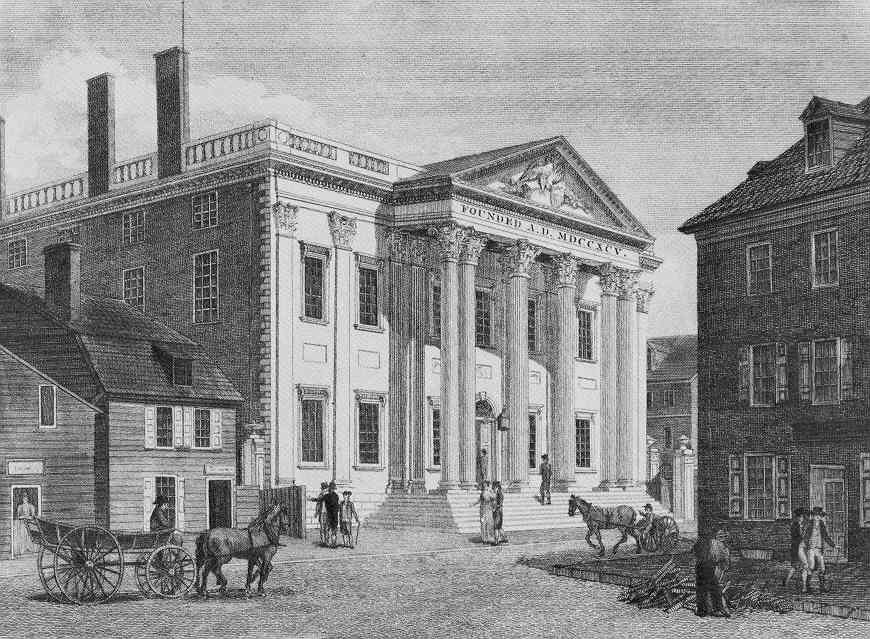

The first Bank of the United

States – Philadelphia

Library of

Congress

| Hamilton's

program was designed to found the nation not on the democratic whims of

the masses but the hard-nosed realism of the moneyed class that

commanded the American economy. Understanding the mind-set of America's

moneyed class, Hamilton planned to involve this class in the new

government by inviting wealthy financiers to exchange the old

Continental Congress's bonds with the Republic's new bonds. This would

give these individuals a very strong financial interest in seeing the

new government succeed. And, most importantly, it would place the new

government's finances on very strong foundations.

Money is power. And the new nation needed power in

order to survive in a very competitive world. Strong financial

foundations were absolutely essential for a Republic trying to

establish itself as a serious, viable institution in a very challenging

world.

But the reaction to his proposals was swift. The

heart of the reaction was this matter of great principle found in the

personal debts hanging over the Patriot foot soldiers during their

wartime service (loans or mortgages for their homes and land they owed

various banks), when they were in no position to meet or pay down on

those debts. After the war they had returned to civilian life only to

find that those debts had gr own even larger while they had been away in

the army. Worse, they had been paid for their wartime services with the

almost worthless notes issued by the Continental Congress. They

retrieved what value they could by selling these notes to speculators

for whatever they could get, never enough however to meet the heavy

financial obligations hanging over them. And now, here was Hamilton

paying those speculators full value for these notes bought on the cheap

from penniless citizens. This all seemed very unfair, sort of a double

slap in the face of America's small heroes.

And there was also the irritation of the states

such as Virginia, which had paid off its own debts in full. Why should

they be part of a program assuming the debt of the states that had not

done what they had done?

There was a lot of anger that arose over Hamilton's

program. Jefferson's friend Madison was most vocal in his indignation

at Hamilton's idea of debt assumption because it seemed to be

developing at the heart of the federal system a power center on the

order of the royal tyranny America had just freed itself from.

Madison's strong stand eventually pushed Jefferson into an

ever-stronger States-Rights (or Anti-Federalist) position. And it cost

Hamilton his friendship with Madison, who as a former Federalist, now

turned into an equally dedicated organizer of an Anti-Federalist group

headed up by his fellow Virginian, Jefferson.

As it turned out, Washington threw his support

behind his treasury secretary and Congress moved ahead to approve

Hamilton's program. And indeed, it did put the new Republic on fairly

firm financial footing. But it had opened a wide political wound

between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists that would not be healed.

As Madison himself had forecast (and in the Federalist Papers had

justified as necessary to the proper functioning of a representative

government) America took its first steps toward a two-party political

system: Hamilton's Federalists in competition with Jefferson's

Anti-Federalists, who under Madison's tutelage would organize

themselves as the Republicans (not related to the modern Republican

Party)

|

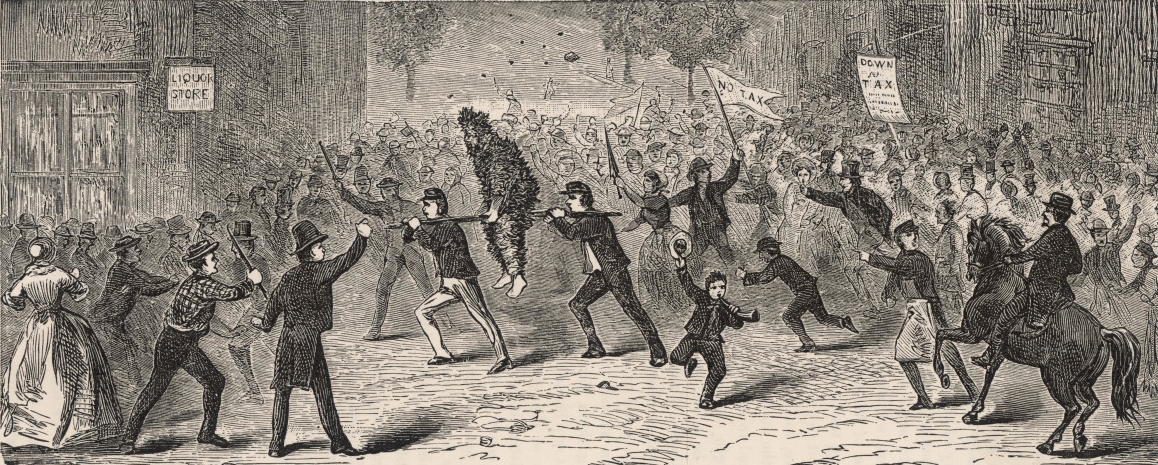

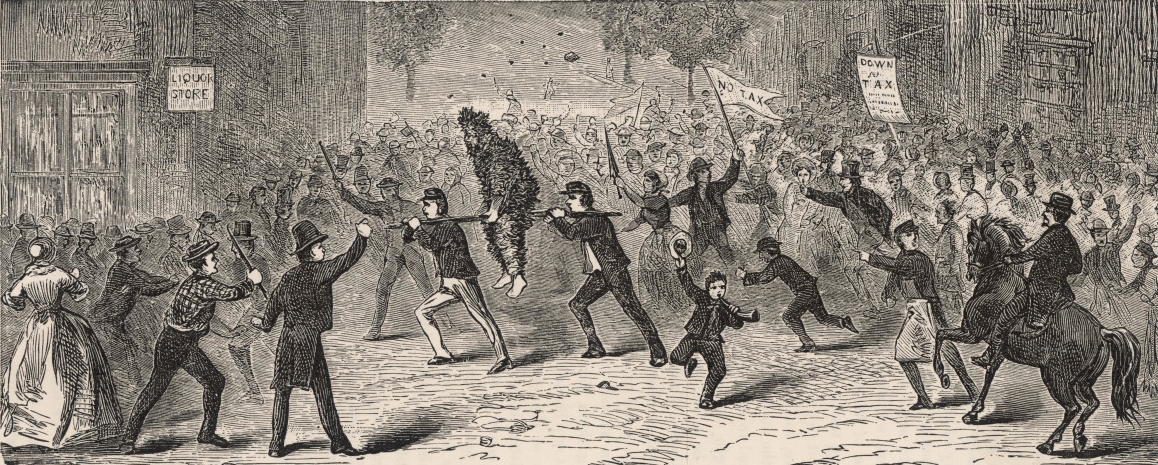

One of Hamilton's federal revenue collectors being tarred and feathered by irate farmers

during the Whiskey Rebellion in Pennsylvania (1791-1794)

|

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1791-1794

But

paying off that debt was proving to be highly difficult. When Hamilton

had raised import duties as high as he felt he could go before it would

start crippling American business, in 1791 Hamilton placed an excise

tax on the production of whiskey, a basic essential in the diet of the

American farmers – and also a means of currency in the farmers'

businesses. Understandably, the new tax met with the same resistance

that had George III's 1773 tea tax imposed on his American subjects to

pay for his wars. Westerners from upstate New York, through Western

Pennsylvania, into Ohio and Kentucky, Western Maryland and the Western

Carolinas all got increasingly involved in the refusal to submit to

Hamilton's tax.

Complicating matters was the fact that Eastern

distillers could be much more efficient in the massive production and

local distribution of their product and thus proportionately much less

burdened by the excise taxes than the frontier farmers. Consequently,

Eastern distillers offered no objection to the new tax. However, this

differing situation facing the Eastern producers and the Western

farmers merely added to the enormous frustration of the latter group.

Washington, however, agreed with Hamilton that the

toleration of the insubordination in the West would collapse the

authority of the Republic. It was a hard thing to do to come up against

these strong souls, many of whom had fought alongside Washington in the

War of Independence, a war that had had similar roots in its resistance

against George III's new taxes.

But ultimately the question was not about taxes

(for a government cannot operate without an income stream of some kind)

but about the legality of those taxes. The Republic needed everyone

involved in the support of their new government, not just the business

and financial classes of the Eastern cities, in order for the Republic

to succeed and not fail.

And finally, just as in the need to maintain

discipline in a war-time army, the Republic would fail in peace-time

unless it too could get compliance to its laws, laws properly or

legally instituted and properly enforced. Lack of political discipline

would certainly destroy the Republic.

Events going on in Paris (the French Reign of

Terror, 1792-1794) at that very same time were making this matter quite

clear. Street mobs had taken control of the effort to birth the new

French Republic and it was looking increasingly likely that the French

Republic was thus going to fail in its efforts to get itself

established. Now the very same threat seemed to hang over the young

American Republic at this point.

Thus in August of 1794 Washington led a 13,000-man

army into Western Pennsylvania to confront protesters (who quickly

melted away at the appearance of Washington and the army). The show of

force broke the rebellion. The authority of the Republic's government

was thus confirmed.

But ultimately, the event only deepened the

distrust by the rural Westerners (and Southerners) of the moneyed class

of up-East Federalists.

The Kentucky Question

This event and the

growing regional distrust would register itself clearly in the form of

a dispute when Kentucky applied for statehood. The up-East Federalists

dragged their feet, fearing they would be overwhelmed in Congress by a

growing Southern/Western coalition lined up against them. Finally a

compromise was reached in 1791 when New England's Vermont was admitted

to the Union, opening the way in 1792 for Kentucky to be admitted as a

new state as a counterbalancing principle in the politics of statehood,

a principle that would be applied again and again as the country

struggled over deep cultural differences that separated the various

regions of the country.

|

Washington leading his troops to put down the Whiskey Rebellion (early October 1794)

Washington undertook this unpleasant task ... because he didn't want America to fall into disorder

... the kind that was destroying France at about the same time.

THOMAS JEFFERSON AS SECRETARY OF STATE |

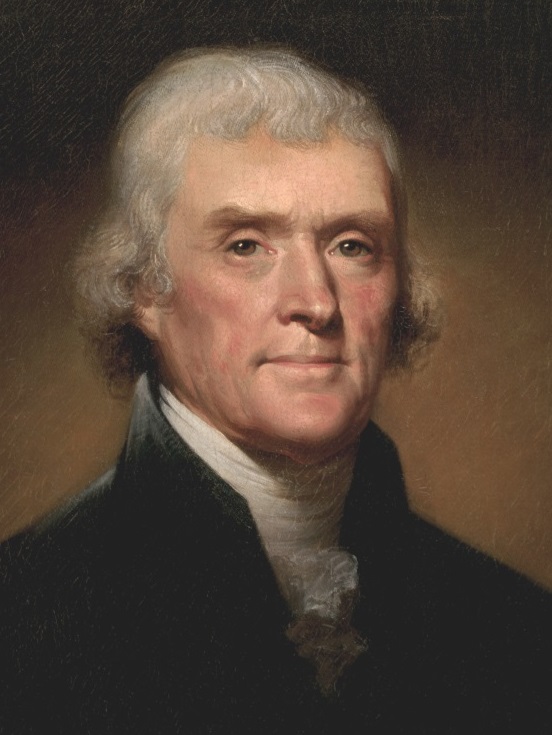

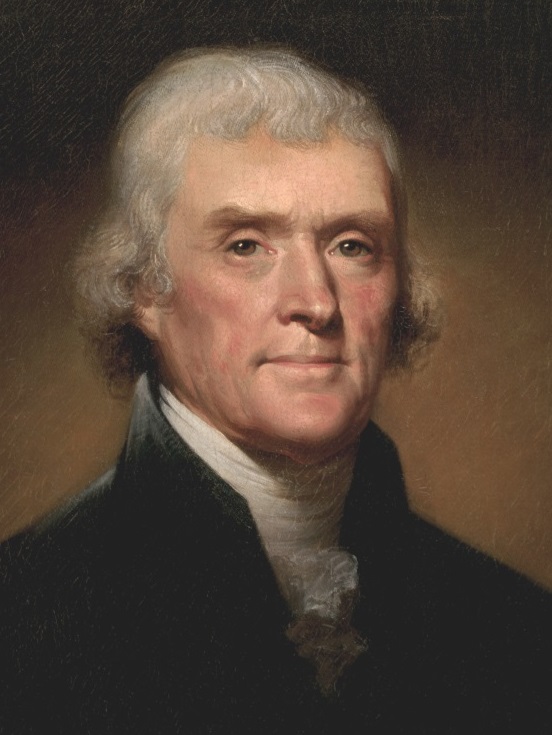

Thomas Jefferson – by Rembrandt

Peale

White House Historical

Association

|

Thomas Jefferson

Washington

had appointed Jefferson to his cabinet as his secretary of state,

charged with overseeing America's diplomatic missions abroad and

(supposedly) advising Washington on foreign policy matters as the need

arose. Jefferson would not be easy to work with.

Jefferson was born to a Virginia planter family,

with important family ties – especially on the side of his mother, Jane

Randolph, a cousin of Peyton Randolph, who was a leading political

figure of Virginia during the 1760s and early 1770s.2 At an early age

Jefferson was tutored along with the Randolph children, and as a youth,

in classic aristocratic fashion, he was taught Latin, Greek and French,

along with history, science and the classics. At age sixteen he entered

the College of William and Mary, where he continued his study of these

same disciplines. He graduated two years later to begin his study of

law under the prominent George Wythe. And at age twenty-one he

inherited 5,000 acres and fifty-two slaves from his deceased father's

estate, including the land where he would begin the building of

Monticello, the place of perfect habitation developed from his own

ideal design.

He was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1767 and as

a practicing lawyer represented his county as a delegate to the House

of Burgesses (1769-1775). In 1772 he married a third-cousin, Martha,

and settled into a period that was perhaps the happiest of his life. In

the ten years of their marriage she bore him six children, only two of

which survived to adulthood.3 They also inherited from her father

another 11,000 acres and 135 slaves to work the land, but also a heavy

debt that accompanied the title.

When he was sent to represent Virginia at the

Second Continental Congress in 1775, he befriended John Adams. And thus

he was invited to join the committee assigned the task (supposedly

Adams's responsibility) of drafting a Declaration of Independence, the

startup version which was ultimately assigned to Jefferson. Some

changes were subsequently made to Jefferson's draft by the committee,

then by the full Congress (as we have already noted, about a fourth of

the whole was cut out, including a section connecting King George and

the slave trade!).

At the time, the Declaration seemed to be a much

less significant matter than all of the new state constitutions being

drafted by the thirteen newly independent states!

Shortly after this (September of 1776), he was

elected to the new Virginia House of Delegates. Here he served on the

committee working on the new Virginia Constitution, and sponsored the

Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, forbidding state support of

religious institutions or doctrines – which however failed to pass. Two

years later he was given the responsibility of reviewing and editing

Virginia's system of laws. And the year after that (1779) he was

elected as the state's governor, undertaking at that point to institute

new laws in pursuit of his personal worldview concerning religion,

education, property rights, etc.

When in 1781 Benedict Arnold, at that point

serving the British, attacked the new Virginia capital at Richmond,

Jefferson and members of the Assembly were able to escape to Monticello

(Richmond was burned to the ground). Then when Cornwallis approached

Monticello, they escaped from there to another of his plantations to

the West.4

After the war (1783) he became a delegate to the

Confederation Congress where he chaired the committee that drafted the

1784 Land Ordinance, removing the Northwest Territories from the

on-going land title conflicts among the states by making them

territories eventually eligible to become states of their own. Also,

slavery was to be outlawed in these territories.5

In 1784 he was sent to join Franklin and Adams in

Europe in the effort to negotiate trade agreements with England, France

and Spain (Franklin returned to America the next year). Jefferson

quickly (1785) made himself at home among the French, befriending the

Marquis de Lafayette in his effort to develop improved trade relations

between the U.S. and France.

He also fell in love with the French lifestyle

(including its wine and books). Then soon after the French Revolution

broke out in July of 1789, he returned to Virginia, intending however

to return soon to Paris. But the request by Washington to serve as his

new secretary of state (charged with the responsibility of supervising

the country's diplomatic mission) caused him to remain in America.

But this would bring him into direct contact with

Hamilton, a man whose views Jefferson by instinct opposed on virtually

every front. Hamilton was very supportive of a strong central

government, able to unify the functioning of the thirteen states,

politically as well as economically. This Jefferson opposed strongly,

fearing that such a strong central authority would compromise greatly

the states' rights to conduct their own affairs as they chose. He was

thus highly opposed to the concept of a national authority (until he

himself later became president of that very nation!).

Furthermore, unlike the almost spiritual rapport

that existed between Washington and Hamilton, Jefferson and Washington

lived in very different universes when it came to foreign policy and

diplomacy. Even though Jefferson was supposed to be in charge of the

conduct of foreign policy, it was usually to Hamilton that Washington

turned rather than to Jefferson when faced with a foreign policy issue

needing to be resolved. Jefferson grew increasingly resentful over

this.

A big part of the problem was that Jefferson was

by nature an intellectual who lived in a world of perfect plans and

grand schemes. He was also personally smitten by French culture and had

become deeply involved in the Enlightenment dreams of the French

intelligentsia that eventually took over the French Revolution – and

drove it to the human butchery of the 1793-1794 French Reign of Terror.

And Jefferson, even though saddened by the gruesome excesses of French

Republicanism, refused to admit that there was any injustice in how

these cruel events were unfolding in France. A greatly self-blinded

Jefferson was quite certain that 99 percent of the Americans supported

strongly, even gladly, the events going on in France. Thus despite the

carnage, he convinced himself that it was France that needed America's

total support in the ongoing English-French conflict.6

Hamilton and Washington, on the other hand,

despite the recent war with their English cousins, still considered

England as America's best partner when it came to the contests

involving European politics and economics, which seemed always

unavoidable, especially to such a trading people as the New England

Yankees.

There really was no way to side-step the ongoing

French-English conflict, and neither France nor England would let

America get away with being merely neutral in the struggle. One way or

the other, America would constantly have to choose sides, not usually

happily, whatever the choice. And in choosing sides it usually ended up

pitting Hamilton and Washington against Jefferson (and Madison).

Jefferson grew increasingly furious about how

Washington was lining up behind Hamilton and the pro-British

Federalists and in December of 1793 resigned his position on

Washington's cabinet. From then on, he and his Republicans would be

active opponents of Washington and his Federalist cabinet.

|

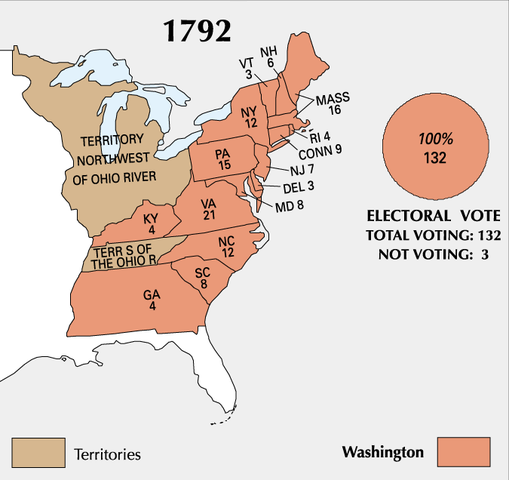

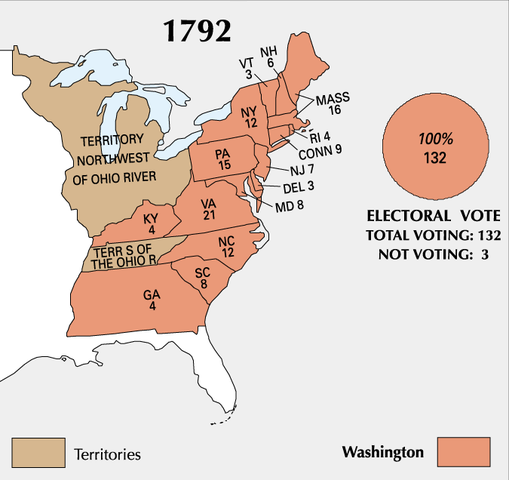

Washington's re-election as U.S. President in 1792

2Randolph

was speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses (1766–1769), was the

president of the First Continental Congress (1774) and president of the

Virginia Convention debating independence from Britain (1775, just

before his death that year).

3Already sick from diabetes and her frequent childbirths, she died in 1782 at age thirty-three in delivering their sixth child.

4It

was later that year decided by the Assembly that Jefferson had acted

appropriately. But he had lost such stature that he was not reelected

governor.

5His

anti-slavery provision was not approved at the time, though

reintroduced and subsequently approved when the ten territories were

consolidated into five territories, the future states of Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin.

6When William

Short, a Jeffersonian supporter, wrote Jefferson from Paris that mobs

had taken over the French Revolution and had executed some of their

French friends, Jefferson in early January of 1793 wrote back a sharp

rebuke: "The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of

the contest, and was ever such a prize won with as little innocent

blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the

martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed I would

have seen half the earth desolated; were there but an Adam & Eve

left in every country, & left free, it would be better than as it

now is."

|

The Citizen Genêt Affair

This

Federalist-Republican conflict came clearly into public view in

1793–1794 when the new French Republic sent Citizen Edmund Charles

Genêt to America as its diplomatic representative. Jefferson was

enthusiastic in receiving this polished Frenchmen.

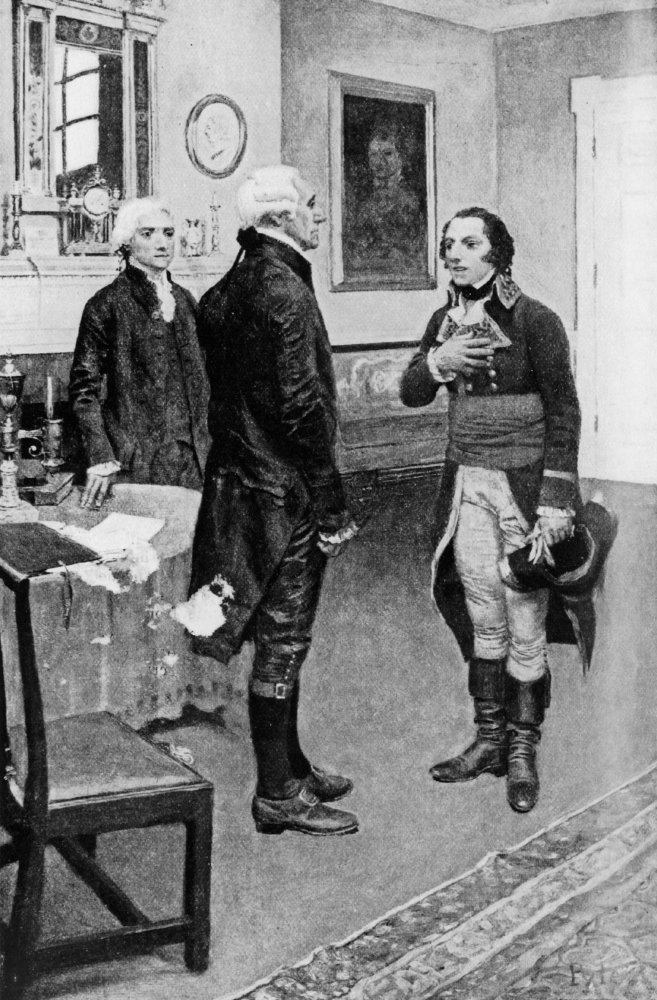

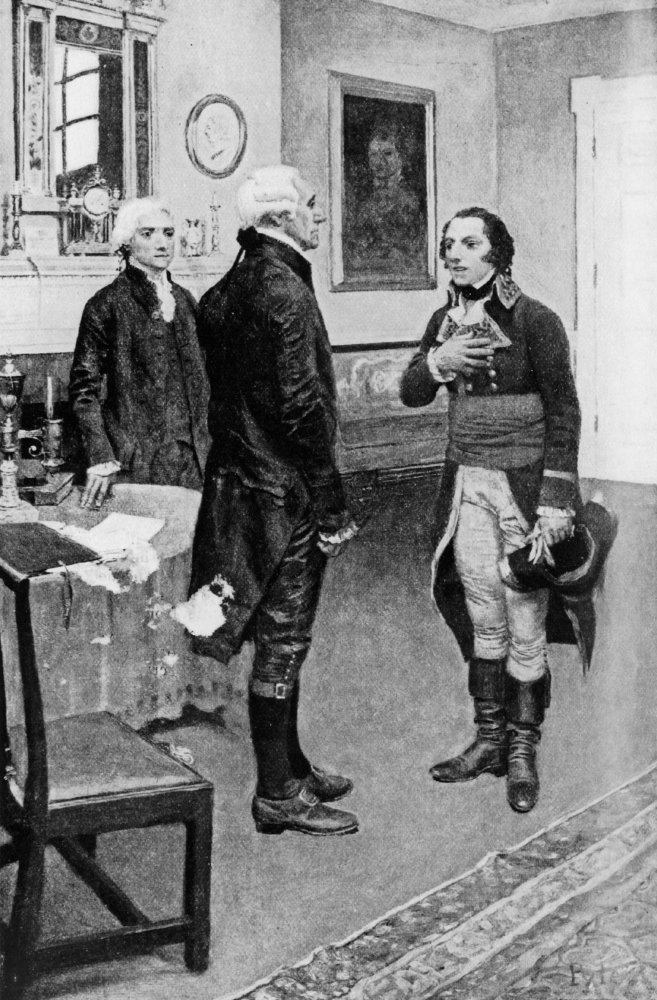

Genêt presenting himself to Washington upon his eventual arrival to Philadelphia.

Then the

problems began. Genêt treated America as if it were a poor

step-child. When Washington declared America neutral in the

French-English war, Genêt began to go around the authority of the

president, maneuvering in different ways to involve America in the war

on the French side. Genêt disregarded all diplomatic protocol by

setting up Americans to attack English and Spanish positions in

Florida, Louisiana, and Canada, even hiring privateers to attack

American shipping heading toward England! Washington was

furious. And at this point even Jefferson and Madison were ready

to back away from him.

In any case when in 1794, during the French Reign of

Terror, the extremely radical Jacobin Party began executing not only

"enemies of the Revolution" but also the rival revolutionary (though

less radical) Girondist Party, of which Genêt was himself a member,

Genêt himself realized that he was now a man on the run.

Washington was gracious enough to grant him asylum, and Genêt spent the

rest of his days quietly in America!

Jay's Treaty (1794)

Despite the formal signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris marking the end

of the American War of Independence, the British had been disregarding

the specific terms of the agreement as if they had never existed. The

British had failed to pay the promised compensation to slave owners

whose slaves the British had freed during the War. But America had also

failed to keep its promise to compensate American Tories who lost their

property when they fled to Canada during the War. In any case, the

British continued to occupy their forts in the Western territories, and

even allied with Indian tribes to block the spread of the American

settlers into those territories.

Despite the formal signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris marking the end

of the American War of Independence, the British had been disregarding

the specific terms of the agreement as if they had never existed. The

British had failed to pay the promised compensation to slave owners

whose slaves the British had freed during the War. But America had also

failed to keep its promise to compensate American Tories who lost their

property when they fled to Canada during the War. In any case, the

British continued to occupy their forts in the Western territories, and

even allied with Indian tribes to block the spread of the American

settlers into those territories.

But what was most disturbing was the high-handed way the

British impressed sailors by boarding American ships and seizing

sailors they claimed were simply their sailors who had deserted to the

easier life under sail in America. In fact, many of these sailors

pressed into British naval service were simply the hardiest looking

American sailors, and not British at all. To try to get the British to

ease up on impressment and to honor the terms of the Treaty of Paris,

Chief Justice John Jay was sent in 1794 to London to negotiate a better

working relationship with the British.

But America was in a distinct position of having to negotiate

from weakness, at a time when the British were more focused on winning

the on-going struggle with the French than on making Americans happy.

As a consequence, Jay returned from England with a new treaty ("Jay's

Treaty" as it was scornfully termed) that seemingly offered America

very little. The idea of Britain compensating the American slave owners

for their property loss was dropped (infuriating the Southerners) and

America agreed to accept limited trade rights as neutrals in exchange

for the British to finally vacate themselves from the American West.

Although Jay could not have extracted anything more from the British

than what they had agreed to in this new treaty, Americans of all

political shades were outraged. Even Washington came under abusive

attack in the press for his acceptance of the treaty.

After a bitter debate in Congress, the treaty was approved

(barely) by the necessary two-thirds vote in the Senate. But

Jefferson's Republicans, holding a strong voting position in the House

of Representatives, were determined to block the appropriations

(spending) necessary to bring the treaty to full force. Discussions in

the House dragged on for months, with both England and France lobbying

representatives to vote up (the British) or down (the French) the

necessary legislation. In the end (by a majority of only three votes)

the House approved the appropriations bill backing the treaty.

But the emotional price paid for passage had been very, very

high. Jefferson's Republicans had lost no opportunity to slander the

Federalists as pro-monarchist because of their pro-British sentiments.

The Republicans awarded themselves the title of true Republicans

because of their support of the French Republic, Americans not yet

having realized, or at least not having been willing to acknowledge,

the brutality of events in Republican France. The American Republicans

were totally supportive of the French Republic's devotion to spreading,

quite violently, anti-monarchical – and often even anti-church -

Republicanism to the rest of the civilized world. Thus Hamilton was

greatly slandered by the Republican press for his pro-monarchist

loyalties (but he was actually not at all a pro-monarchist, as his

actions in the recent war had clearly demonstrated), because he was not

willing to join with the Republicans in their enthusiasm for what was

going on in France. That was a cheap political shot aimed at Hamilton

by the Jeffersonian faction. But Washington was slandered no less for

the same reason!

But the press campaign was very effective. It marked the beginning of

the decline of the Federalist Party.

|

JOHN

ADAMS TAKES COMMAND (1797) |

|

Washington refuses to take on a third term as president

Washington had originally agreed to serve only one term as president

(1789-1793), but had been prevailed upon to run for a second term in

the approach to the 1792 elections. He grudgingly accepted the request.

But now in 1796, as he approached the time for the elections for a

third term in office, he made it very clear that under no circumstances

would he continue to serve as president once his second term in office

ended in early 1797. He was tired of the bickering between the

Federalists and the Republicans and wanted simply to go home to his

farm at Mount Vernon. Washington was thus more than willing to oversee

a smooth handover in power to his successor, which in this case was his

vice president, John Adams.

And so it was that Washington set the

constitutional tradition that two terms in office was something of a

limit to presidential service. America would not be saddled with a

president-for-life, as so frequently happens in new republics.

7President

Franklin Roosevelt, however, would run for a third and even fourth term in the

1930s and 1940s using the emergency of the World War (Two) as

justification for doing so. But Washington's "two-terms-only"

presidential tradition was ultimately confirmed as a Constitutional

Amendment (the Twenty-Second) in 1951.

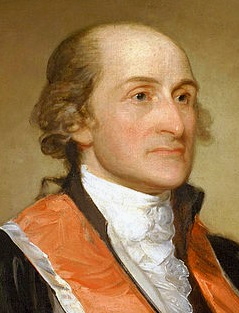

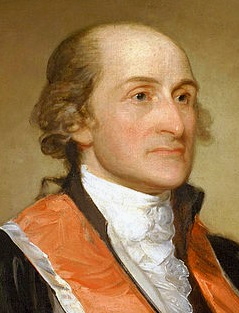

John

Adams – 2nd President of the United States – by Gilbert Stuart

National Gallery of Art

|

John Adams

Although Adams was a staunch Federalist, he was very

sensitive to his own place in the scheme of things politically and

socially, and found himself frequently at odds with not only Jefferson

and his Republicans, but also Hamilton, who after Washington, was the

strongest figure among the Federalists. A man of high moral principle,

Adams unfortunately was lacking in the tact necessary to put those

principles to use without raising a lot of powerful opposition. Sadly,

he went largely unappreciated in his own days and by his own people for

the way he helped follow up Washington's lead in bringing the country

to even greater stability and security – at a time when huge dangers

still swirled around the young Republic.

Adams had grown up in a small Massachusetts town

to a family that held strongly to the original Puritan beliefs and

ethics, stressing basic human equality in God's (and thus man's) eyes,

the importance of working to achieve rather than merely inheriting

one's place in life, and the critical nature of personal integrity, no

matter the possible social cost for living true and honestly. Also in

typical Puritan fashion, there was an early emphasis in his family on

the importance of formal education which Adams began at age six, then

continuing into Latin School, and at age sixteen entering Harvard

College.

But he disappointed his father when he dismissed

any ideas of becoming a minister and graduated from Harvard instead as

a teacher, pondering the question (that he faced most of the rest of

his life) of how to become great. This of course put him in conflict

with his sense of Puritan morality, a conflict that he would never

successfully resolve.

Law nonetheless seemed to offer the best path to

the greatness that he so eagerly sought. Thus he clerked for a

prominent local lawyer and in 1758 received his master's degree from

Harvard and was soon admitted to the bar. Eventually his legal work

would draw him into the cause against growing royal authority in the

colonies, for which he began to write (anonymously) in the Boston

newspapers.

In 1764 he married a third-cousin and preacher's

daughter, Abigail, and proceeded to have six children in fairly rapid

succession (the last however did not survive birth), the second born

(and first son) being the future president, John Quincy Adams.

Adams came to public attention when in 1765 he published a letter sent

to the Massachusetts legislature concerning the highly controversial

Stamp Act, restating in very clear and compelling terms the rights of

Englishmen concerning both taxation and judicial treatment by the

authorities. This helped to bring about his election to public office

as a representative on the town council.

In 1768 he moved his family and law practice to

Boston. But his law practice did not come into prominence until he

defended the British Redcoats accused of murdering members of the

Boston crowd who had been taunting the soldiers. He claimed that he

feared that this might damage his reputation. But instead it helped him

to gain a Boston seat on the Massachusetts legislature three months

later and a considerable increase in his law business.8 Seemingly Adams

had finally found his path to greatness. But this came amidst growing

chaos in Boston, and in 1774 Adams moved his family back to the family

farm in Braintree – permanently.

However, he continued his work in Boston in the

thick of a darkening war cloud. He delivered a hallmark speech in the

legislature challenging the British governor with the claim that

Massachusetts had always been self-governing; that its charter was only

with the King, not Parliament; and that the colonies would have no

other recourse if Massachusetts' rights were not respected by British

authorities than to take the road of full independence from Britain.

These ideas were then extensively developed in a publication that

clearly outlined the legal arguments behind them. At this point Adams

had secured a very prominent position in the growing debate.9

Quite naturally Adams was sent by his state as one

of its representatives to the First and Second Continental Congresses

(1774 / 1775-1777). At first he was looking for ways to bring Britain

and the colonies back into a better relationship. But seeing no

flexibility coming from London, he soon found himself working hard to

convince his colleagues that full independence was the only path at

that point open to the colonies. And in mid-1775 he was the one who put

forward the name of Washington as the one to lead the colonial army

gathering around Boston (a careful move to secure Virginia to the

cause). In 1776 he got confirmation from Virginia with that colony's

Resolution joining the cause, and was subsequently appointed to head

the committee assigned the task of drafting a Declaration of

Independence. Jefferson wrote most of the draft, but it was Adams who

guided its passage through the Continental Congress.

Soon after this, Adams was sent with Franklin to

hear the terms that General Howe was willing to offer after a series of

defeats of Washington's army in New York. But the discussions led

nowhere when the American representatives showed no sign of

compromising on their decision for full independence. Adams was now a

hunted man (on the list of treasonous colonials who would have been

shown no mercy if the rebellion had finally been put down by the

Redcoats).

During the next couple of years Adams worked

tirelessly on a number of committees backing the war effort, learning

important administrative procedures through his extensive service to

the cause. Then in 1778 he was appointed (along with Franklin and

another American) to represent the new United States in negotiating a

treaty of alliance with France, then returning home – only to be sent

back the following year to begin discussions in Paris with British

representatives to work out some kind of peace terms (Adams in the

meantime developing some fluency in the French language!).

Adams was a contentious person (as he himself well

knew) and did not find it easy working with Franklin, whose well-staged

homespun manners that so attracted the French Adams himself detested

with equal vigor. Nonetheless, the British (especially after the

humiliation at Yorktown in 1781) were gradually willing to back down

and acknowledge American independence, and work out the compromise

(land rights to the West and compensation for civilian property losses

on both sides of the conflict) that eventually led to the Treaty of

Paris in 1783.

In the meantime, Adams had been appointed

ambassador to the Dutch Republic (1780), securing that country's

recognition of American independence in 1782 and also securing from

Dutch banks valuable loans needed to help the American states get on

their feet after the war. With peace at hand, Adams was appointed in

1785 as America's first ambassador to the English Court of St. James,

where he sincerely sought to restore friendship between the

English-speaking peoples on both sides of the Atlantic. Here in London

he put together another written work, defending the new U.S.

Constitution just after its adoption in Philadelphia in 1787. Though

not as famous as the Federalist Papers, it was itself a very clear

definition of how in a republic a system of checks and balances among

different branches of the people's government was essential to keeping

power operating safely within the bounds that the designers of the

Constitution intended.

When elections for the presidency of the new

Republic were held in 1789, Adams came in second behind Washington in

the count, thus by the understanding of the times becoming the nation's

first vice president. But with this, Adams disappeared from public

view, as was typical of those called to that office. Washington never

drew on Adams' services, never consulted Adams on any issue. This left

Adams resentful against Hamilton whom the president frequently

consulted and even against the president himself whom he visibly

supported but for whom he developed a personal dislike. But at least

the office put him in something of a position to be the heir-apparent

to the presidency when Washington indicated in 1796 that he definitely

was retiring from public service.

But Adams was going to have to face Jefferson and

his alliance of mostly Southern Republicans, plus the question as to

whether or not Hamilton would put his Federalist support behind Adams

(he did, because Hamilton despised Jefferson more than he disliked

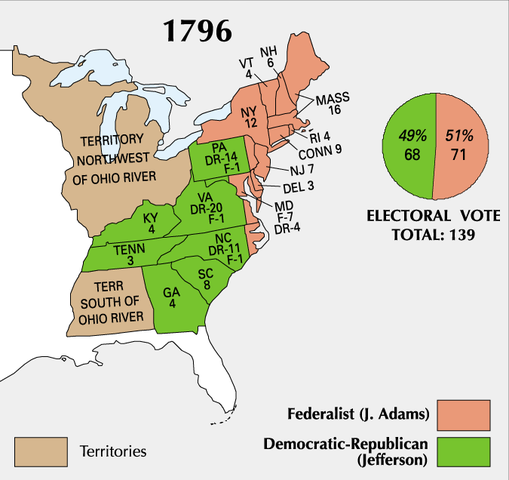

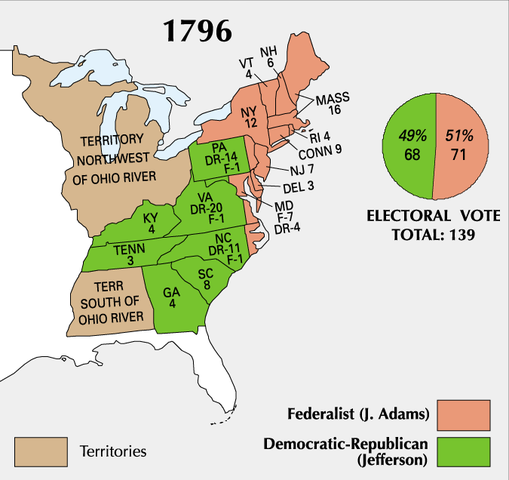

Adams!). In the end Adams narrowly defeated Jefferson with his

seventy-one electoral votes to Jefferson's sixty-eight votes, the

voting being almost entirely a northern versus southern state electoral

division. Thus Adams became the nation's new president, and Jefferson

(being in second place) became the nation's vice president.

The XYZ Affair

Troubles with Europe

continued to rock American politics as Adams assumed his presidential

office. But it was now France's turn to play the role of seizing

American vessels, hundreds of them. Jefferson and his pro-French

Republicans were embarrassed into silence over this French arrogance.

As for Hamilton and his pro-British wing of the Federalists, they

jumped at this opportunity to demand a declaration of war against the

French.

Adams sent a delegation to Paris in 1797 to try to

find a remedy to the problem. But the delegation was met by French

agents X, Y and Z, who demanded bribes and a loan before the Americans

would be allowed to meet with French foreign minister Talleyrand. The

Americans refused and returned to the U.S., with the news of the "XYZ

Affair" stirring even greater war fever among the indignant Federalists

under the slogan, "millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute!"

8Analysts

determined that he had skillfully selected just the right jury members

(many of whom later became pro-British Loyalists), and that from that

moment the outcome of the trial was a foregone conclusion (six soldiers

were acquitted and two convicted of the lesser crime of manslaughter).

9However,

his more flamboyant cousin Samuel Adams was at the time even more

prominent – having led the Boston Tea Party dumping tea in the Boston

harbor in 1773!

|

A cartoon showing American envoys in Paris (October 1797)

refusing to pay bribes to unnamed French agents X Y and Z

|

The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798)

But this then raised among

nervous Federalists the specter of pro-French treason at home (not too

subtly aimed at their Republican rivals). In 1798 the Federalist

majority in Congress rushed through to passage four Alien and Sedition

Acts (which Adams unfortunately signed into law) empowering the

president to deport pro-French traitors and to penalize any pro-French

seditious language that might come from (Republican) newspapers and

public speakers. In the end all this succeeded in doing was drive the

Republicans even deeper in their resolve to oppose the Federalists at

all costs.

The doctrine of nullification

The strongly

Republican Southern and Western states of Virginia and Kentucky, in

bitter reaction to these Acts, passed their own Resolutions (authored

by Jefferson and his ally Madison) affirming that Congress had no

constitutional right to intervene in the internal affairs of the states

and their people. As the Constitution was the product of the action of

the states (or so the Republicans claimed anyway), it was the states,

not Congress, that had the last say in what was constitutional and what

was not. The states were the ultimate sovereign authority within the

Union, not Congress. The states thus reserved for themselves the power

to nullify acts of Congress which they regarded as being

unconstitutional.

This constitutional issue, of course, would be a

matter that would continue to be hotly debated until it finally led to

full civil war in the mid-1800s.

The Quasi-War with France

A conflict boiled over early in 1799 when America's new navy found itself fighting with France on the high seas. Fired up by a major sweep in the 1798 elections (thanks to the XYZ affair), Federalists now pressed harder for a declaration of war against France. Finally Adams took matters in hand to solve this issue tearing the country apart, and sent envoys to Paris to negotiate an improvement in U.S.-French relations. In a resultant treaty, the French agreed leave American shipping alone, thus bringing the "quasi-war" to an end.

The treaty did not at all please the Hamiltonian

Federalists, nor did it suffice to restore for Adams friendly relations

with the Jeffersonian Republicans. But he signed the treaty anyway,

suspecting that by doing so it would end his political career. Indeed,

one month later, during the 1800 presidential elections, Adams was

voted out of office, having served only one four-year term. And thus it

was that Adams had given up the presidency in order to bring the

country back from the brink of war.

|

The American Constellation fighting and defeating the French L'Insurgente (February 9, 1799) during the "Quasi War" (1798-1801)

THE "MIDNIGHT" JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS |

|

Interestingly, the very

last act of his presidency would be the one thing of his presidency

that would come to have lasting constitutional value: the creation by

Congress and appointment by Adams of individuals to some six dozen

judicial posts, including the fateful appointment of the Virginian John

Marshall as chief justice of the Supreme Court.

These mostly new positions resulted from

Congress's recent Judiciary Act of 1801, which expanded the number of

Judicial posts (which indeed were too few to handle the large caseload

before them), an act that was rushed through a lame duck10 Congress of a

majority of Federalists, many of whom had just lost the federal

elections to a new Jeffersonian Republican majority, but had a few

weeks of time remaining in office before the newly elected Congress

could take its place in the new capital city of Washington, D.C.

(actually at this point a forlorn collection of shacks, muddy lanes,

and farm animals!). In fact the job was so rushed that Adams spent his

last night in office completing the task of making these judicial

appointments, thus earning them the reputation from the Republicans as

the "midnight judges."

With this last act of public service completed,

Adams quietly slipped away from the capital to his home in

Massachusetts, a rather tired and bitter old man. He hadn't even

bothered to stay long enough to see the new president of the United

States, his once close colleague but now strong political rival

Jefferson, sworn into office.

But once again, the simplicity of this procedure

would demonstrate that in American political culture, defeat in an

election meant not a prolonged challenge to the results by a resentful

loser, but a peaceful transfer of power to the winner. It had been that

way since the founding of the Anglo-American society in the early

1600s, and would continue as an important political tradition into this

new era of Republican government.

10The

term "lame duck" refers to office-holders who have been voted out of

office in an election that went against them, but who still hold the

office for a brief period until the newly elected officials can take

their place. A lot of frantic legislation is often passed by a lame

duck assembly, realizing that it is about to lose power to its

opponents.

11That

important principle however seems to have been abandoned in the 2016

election, which brought the Republican Trump to the White House.

Democrats not only went to the streets in loud protest over the

results, but Democrat congressmen/women supported by a very Liberal

press corps began immediately to look for grounds to impeach Trump for

having committed "high crimes and misdemeanors" – and would stay

completely focused on that effort for years thereafter. And four years

later, Trump supporters would return the favor in their physical attack

on Capitol Hill when Trump lost the 2020 presidential election to

Biden. This is Third World politics, typical of what happens in

elections (should they even have them) in Asia, Africa and Latin

America. For America this has constituted a grand departure from

America's great constitutional tradition.

LIFE SETTLES IN NICELY AT HOME IN THE NEW REPUBLIC |

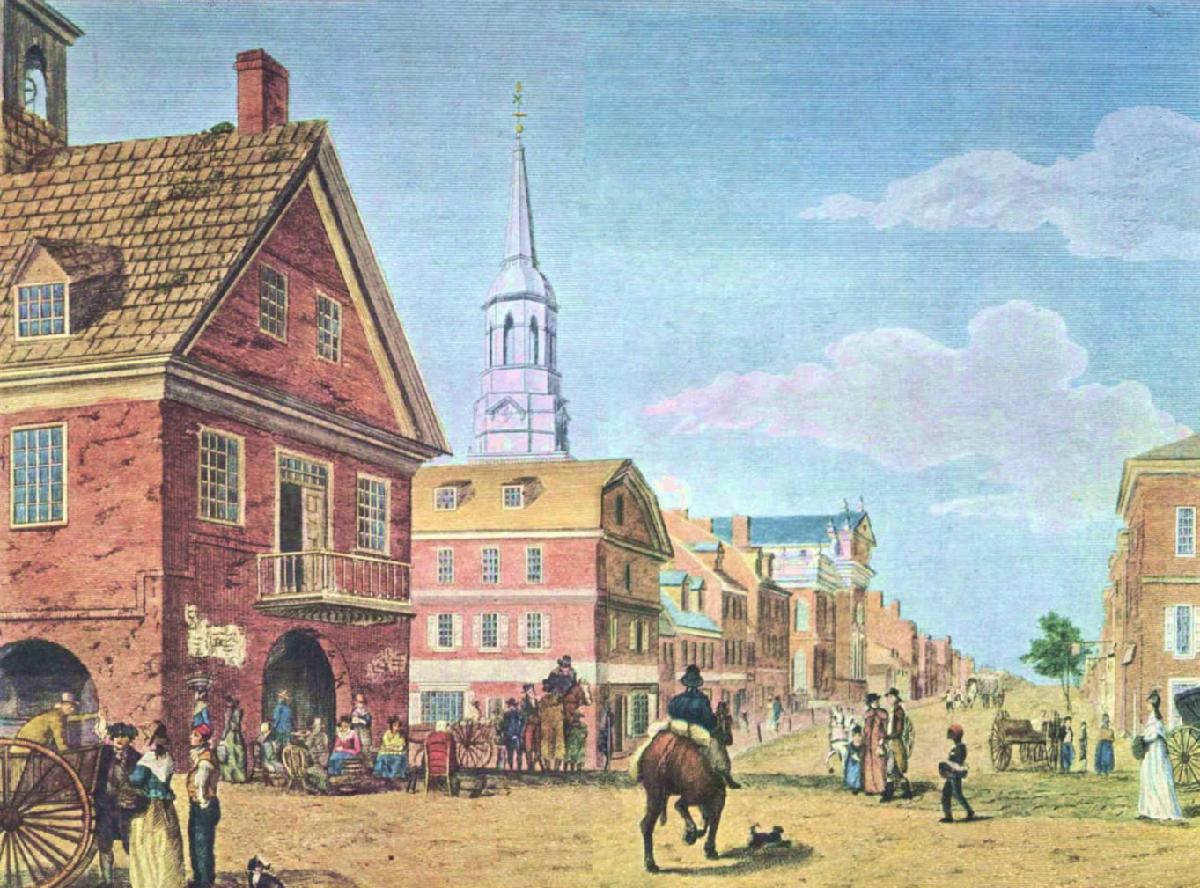

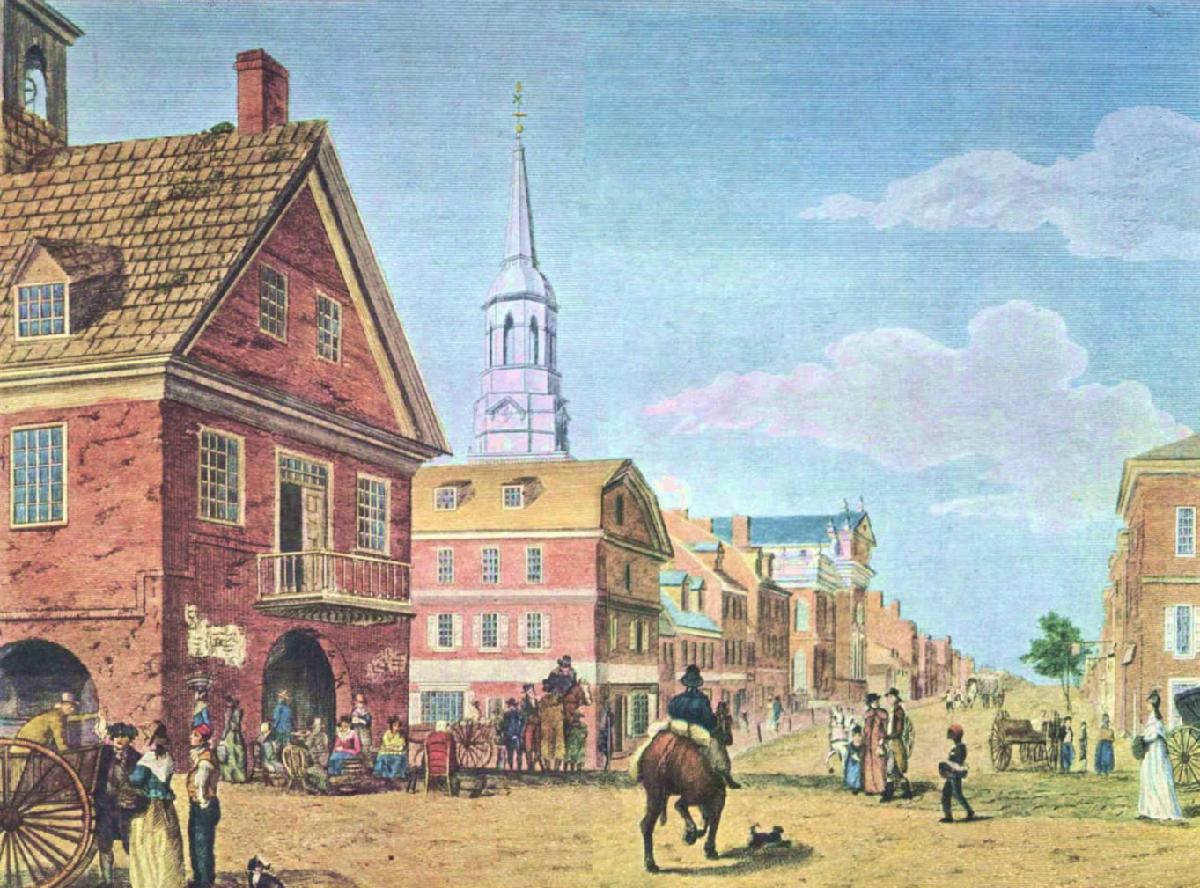

Philadelphia -

1799

Historical Society of

Pennsylvania

Philadelphia street scene

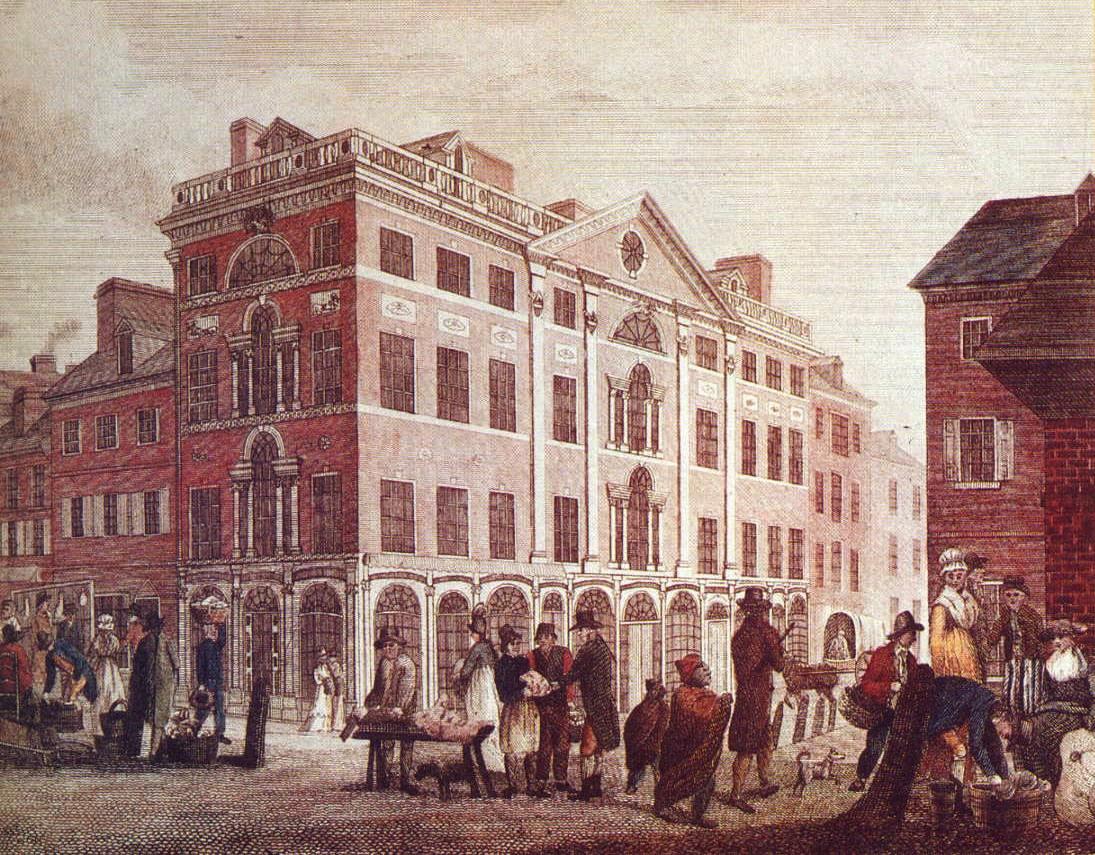

Tontine Coffee House in New York City – (around 1797)

New York Historical Society

Boston – 1800

Miles H. Hodges Miles H. Hodges

| | | | |