10. AMERICA RECOVERS – 1865-1880

RECONSTRUCTION

CONTENTS

Johnson and the Radical Republicans Johnson and the Radical Republicans

Reconstruction in the South Reconstruction in the South

Black Reconstruction Black Reconstruction

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 319-323.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1860s |

Johnson replaces Lincoln ... and the Radical Republicans take command

1865 Vice President

Johnson becomes American president ... but faces the wrath of Northern

Republican "Radicals" – led principally by Stevens and Sumner – when he attempts to follow Lincoln's idea of North-South

reconciliation; Radicals view the Democrat Johnson as being simply

"pro-South" ... and do everything they can to block his presidency

1866 Johnson's effort (Mar) to block Congress's authorization of the 14th Amendment (equality of all citizens before

the law ... but also excluding from federal office anyone who had

fought against the Union) merely

produces a strong political reaction in the North ... one that

increases greatly the Republican

position in Congress in the elections (Nov) ... which in turn then

enables the Republicans/Radicals

to easily overturn Jounson's vetoes of their other Reconstruction

programs

Former

Confederate General Forrest forms the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to fight

Southern Reconstruction

1867 US Secretary of State Seward negotiates the purchase of Alaska from the Russians for $7.2 million (Mar) – to block further Russian expansion into North America; the purchase price was considered by many to

have been excessive ... and called the deal "Seward's Folly"

1868 Johnson is impeached by the House (Mar) and only one vote short of being convicted by a required two-thirds Senate vote (May) of "high crimes and misdemeanors"

The 14th Amendment is finally ratified (Jul)

|

JOHNSON AND THE RADICAL

REPUBLICANS |

|

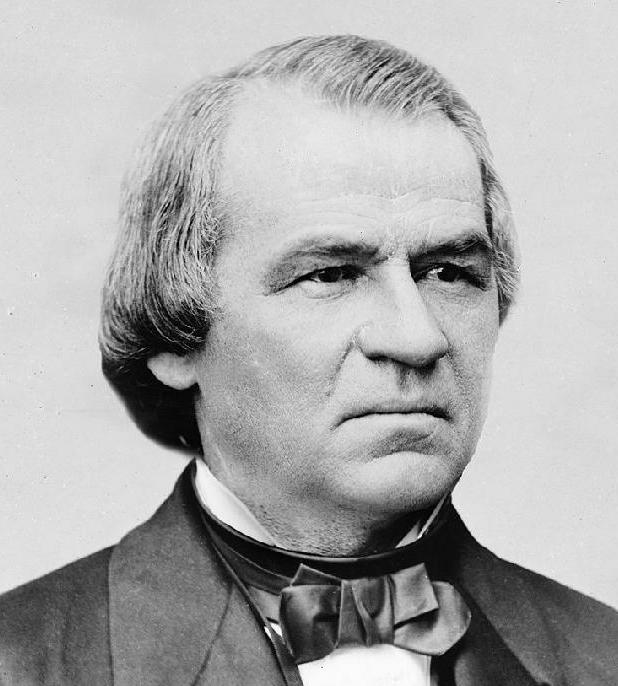

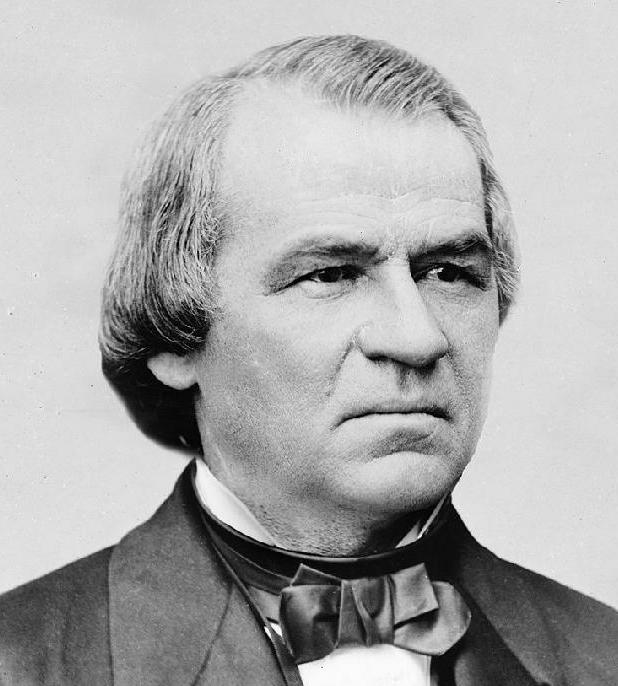

With Lincoln's assassination, Vice President

Andrew Johnson was automatically elevated to the presidency. But

he had neither the personal skills nor the political support necessary

to carry the nation forward through a post-war healing process. Johnson

was a Southerner (from Tennessee) with something of Northern attitudes,

and as a Democrat (not a Republican, as was Lincoln) put on the

presidential ticket with Lincoln in 1864 to flesh out the National

Union ticket that both Lincoln and Johnson ran under. This left

Johnson

in the peculiar position of being on the political spectrum too

moderate for many Republicans and too radical for many of his fellow

Democrats.

He generally believed that he understood

and supported the policies that Lincoln had previously laid out as his

intentions for the South, but would find it virtually impossible to

carry out those policies. He had no personal political leverage that

would enable him to do so.

Thus despite the Constitutional powers of

the presidential office, Johnson himself had no real personal political

power to mobilize in his effort to follow up the Lincoln policy, a

reminder that the man makes the office rather than the office makes the

man.1

Johnson was opposed to slavery, but as

with many in the North, was not convinced that freed Blacks or

"freedmen" were yet capable of conducting the responsibilities of

citizenship (voting and holding office).

Thus he was in no hurry to see the right

to vote extended to the freedman. Rather, he turned his attention to

the issue of reintegrating the Southerners back into the Union. Like

Lincoln, he generally opposed the widespread retribution against

Confederates called for by Northern Radicals. Thus to the Radicals, in

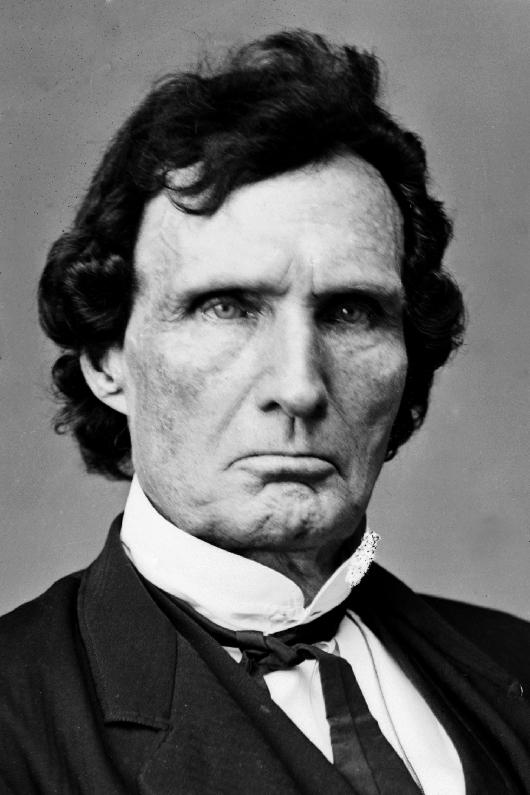

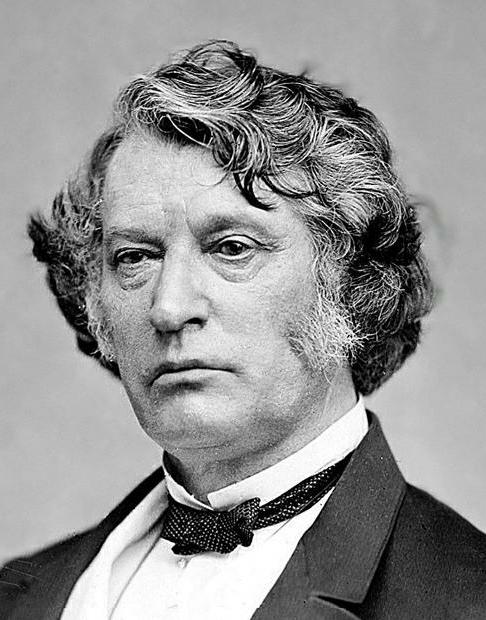

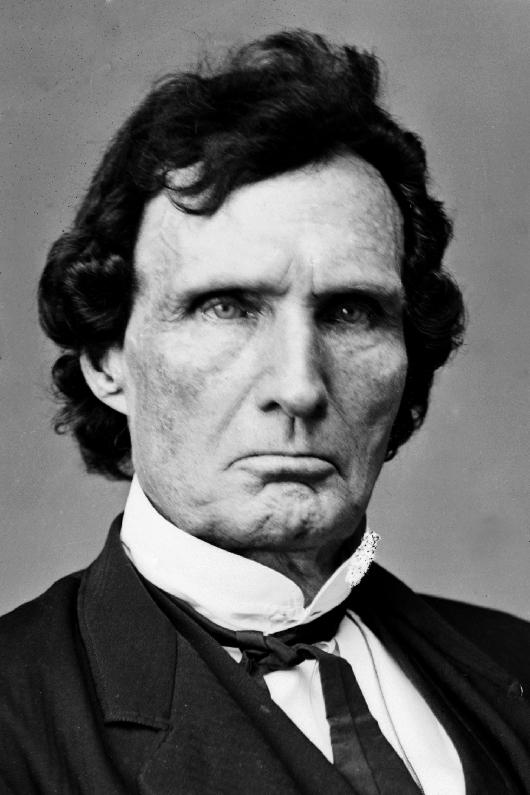

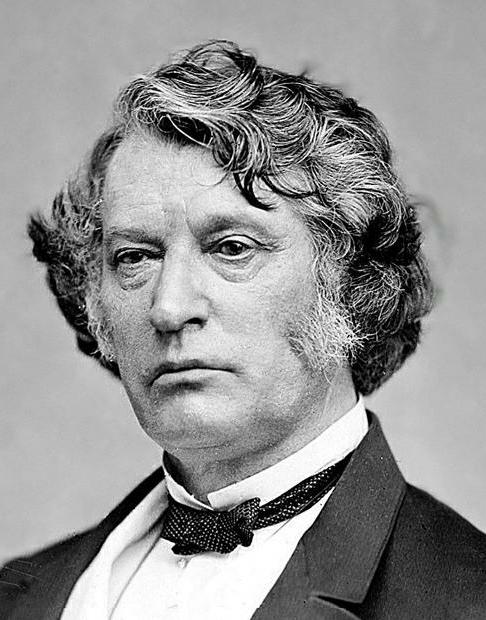

particular Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner (the latter who had

finally recovered from his nearly fatal beating in 1856 by Southern

Democrat Preston Brooks), Johnson seemed treasonously pro-South.

The Congressional election of 1866

returned a large number of Republican Radicals, who then began to

design their own Reconstruction policy (whose bills Johnson vetoed –

only to have each veto overturned by a two-thirds vote in Congress).

And thus it was that Johnson found himself slowly alienated from the

powers that ruled Washington. Earlier that year, the split between

Johnson and Congress was birthed by the 1866 Civil Rights Act affirming

the legal equality of American Blacks, which was passed despite his

veto (Johnson claimed that as per the Tenth Amendment, only the states

had the right to determine the legal status of its citizens). And

seeing a challenge to the new law coming from the South, Congress then

authored the Fourteenth Amendment reaffirming the intent of the Civil

Rights Act (full equality for all Americans, although exempting Indians

and Confederate army veterans!). Johnson's opposition to the Fourteenth

Amendment thus merely served to build the strength of the Radicals in

the 1866 elections, and point to his own political demise.

Eventually, in early 1868, Johnson would

be formally impeached by the House of Representatives (March 2) and

placed on trial by the Senate for his unconstitutional behavior,2

nearly being found guilty and thus removed from office (May 16). Only

the lack of a single vote to produce the Senate's two-thirds majority

necessary to convict spared him this enormous humiliation. But in any

case after that, during the remaining two years in office, Johnson

proved totally powerless in trying to shape events developing in the

country, both North and South.

1This

would be a matter that Americans in general would have a very hard time

understanding, especially those who get caught up in the glory of

nation-building, devoted to designing for others (and imposing, if

possible) a perfect social-political system of various offices and

powers drawn up on paper – as was the case of American involvement in

Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. There were even strong elements of this

same mentality in Wilson's taking America into World War One with the

idea of freeing and redesigning many of the world's societies around Wilson's own highly idealized principles of democracy.

2Of

the eleven charges brought against him, the primary charge concerned

his removal of the Radical Republican Edwin Stanton as secretary of war

and replacement by the more moderate Ulysses S. Grant. This was in

violation of the Tenure of Office Act passed in 1867, itself a highly

questionable constitutional act that Congress enacted specifically to

end Johnson's power to remove cabinet appointments (such as in the

specific case of Stanton, where considerable friction had been

developing between Stanton and the president).

Andrew Johnson – US President 1865-1869

"Home Again" by Dominique Fabronius – depicting a returning wounded Union soldier

Senate Committee to try President Johnson's Impeachment charges (May1868)

National

Archives

Leaders of the Radical Republicans, Thaddeus Stevens

... and Charles Sumner

RECONSTRUCTION IN THE SOUTH |

|

Southern Reconstruction had actually already begun

before war's end, as Lincoln had placed pro-Union administrations in

each of the Southern states as they came under Union control:

specifically Tennessee, Arkansas and Louisiana. Slaves had technically

been freed as of Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation coming into effect

on January 1, 1863, but the economic reality of what newly freed slaves

might do to feed and take care of themselves had created a huge amount

of confusion. Many joined the ranks of the Union army, thus fitting

them into some kind of a place within the social scheme of things. That

helped. But with war's end, the future of the freedman was still in

doubt. Radicals talked of giving each freedman some forty acres and a

mule to start out life with.3 But that idea had never been put into some kind of specific political formula before Lincoln's assassination.

Anyway for most Blacks who received no

title to any land, the only alternative they had was to sign on with a

White plantation owner either as a tenant farmer, or as a sharecropper,

where the plantation owners provided the land and the sharecroppers the

labor (actually the majority of Southern sharecroppers were poor

Whites). Lacking property, the Blacks soon were to discover what poor

Southern Whites had long known, that they were unlikely to achieve the

American dream (although in fact a small number of Blacks were

ultimately able to acquire land and a settled place in the Southern

scheme of things).

Indeed, the situation for the Whites was

often not much better than that facing the Black freedmen after the

war, haggard soldiers and starving women and children scrounging

through burned-out towns and farms looking for food or anything else of

value.

And there was the question of what to do

with those who had served in the Southern rebellion as Confederate

soldiers. Radicals were ready to have every Confederate officer

imprisoned and many even executed. A number of Confederate families,

expecting the worst – or just monumentally angry over the war's outcome

– left the country, Mexico and Brazil being favored destinations. For

his part, Lincoln had wanted the South reintegrated as quickly as

possible, and stood adamantly opposed to the vengeance sought by the

Radicals. But the South tragically had lost Lincoln's critical

advocacy. Then when Johnson tried to follow Lincoln's program, but

lacking Lincoln's political base, he ended up merely making his

personal political standing in Washington all the worse.

What Johnson decreed as the requirement

for a Southern state's readmission to the Union was a minimum of ten

percent of that state's population to pledge allegiance to the United

States. The Radicals were hotly opposed to these easy terms. Even more,

they were outraged that readmission to full status in the Union legally

exempted the Southerners from having their land seized, something the

Radicals eagerly sought as a means of redistributing Southern land to

the benefit of property-less Blacks.

Further, this meant that Southerners could elect their own state

officials and send Congressional representatives to Washington, many of

whom were simply former political leaders and military officers of the

Confederacy. The Radicals were furious, and refused to seat these

Southern representatives in the House and Senate.

Nonetheless, little by little and in

subtle ways, traditional Southern culture began to reassert itself. And

whatever plans the Radicals had for reforming the South were to come to

nothing. Black codes were passed throughout the South, forcing Blacks

to contract their labor to Whites, requiring Blacks to obtain official

permission to travel or move outside their counties, and imposing harsh

vagrancy penalties of stiff fines or even imprisonment on any

unemployed Blacks. Also, the professions and skilled trades tended to

be closed to Blacks. And Blacks were forbidden to bear arms (in clear

violation of the Second Amendment).

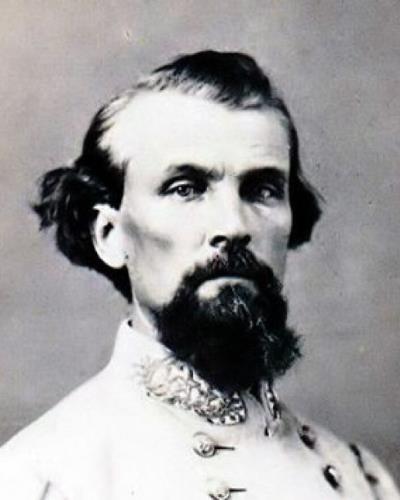

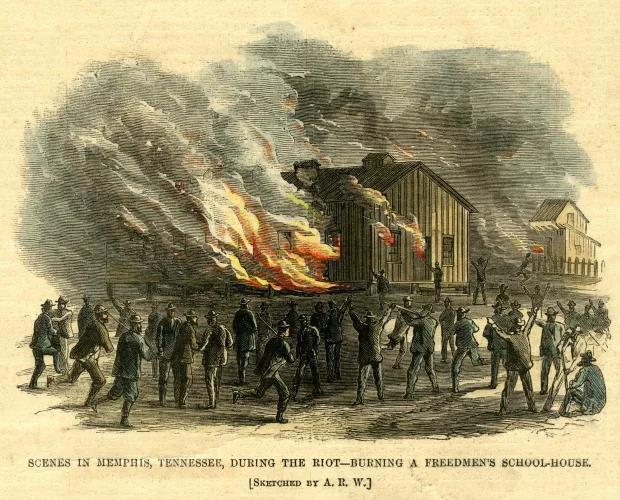

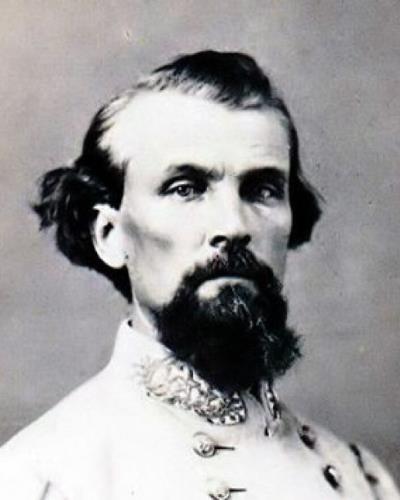

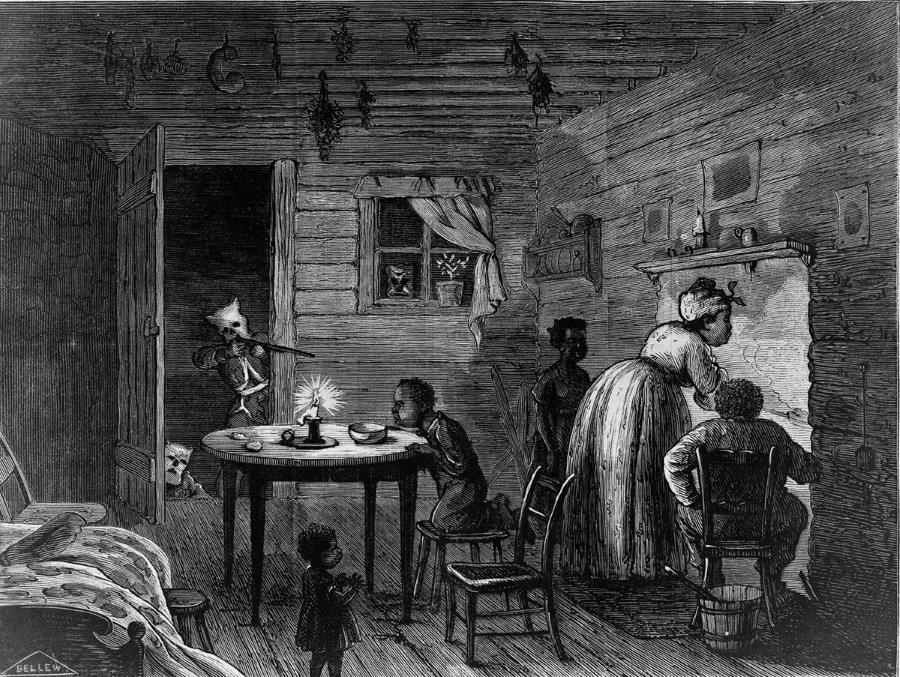

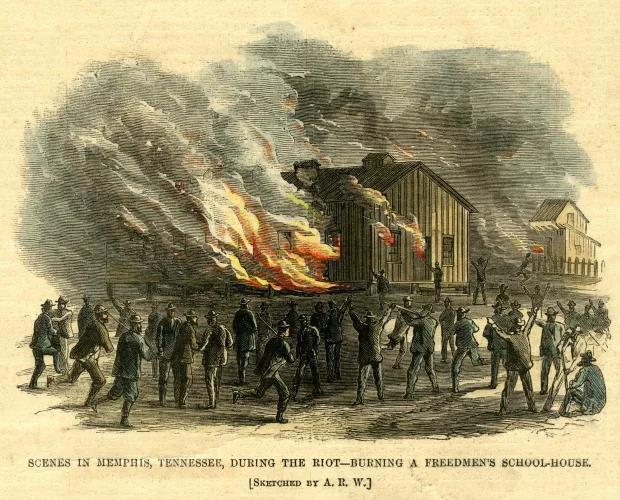

Then there was the creation (1866) of the

Ku Klux Klan, headed up by Confederate cavalry General Nathan Bedford

Forrest, which terrorized the Blacks in order to keep them in their

place. But the KKK could be just as hard on Southern Whites whom they

interpreted as being too sympathetic to the Blacks, burning crosses

being left prominently at strategic spots by the KKK to remind the

terrorized individuals as to who and what was in charge of Southern

society.

3This

idea had actually been put into action by Sherman as he swept through

the South, settling some forty-thousand freedmen on South Carolina's

Sea Islands.

Charleston under Reconstruction

Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest forms the Ku Klux Klan

serving as its first Grand Wizard (1867)

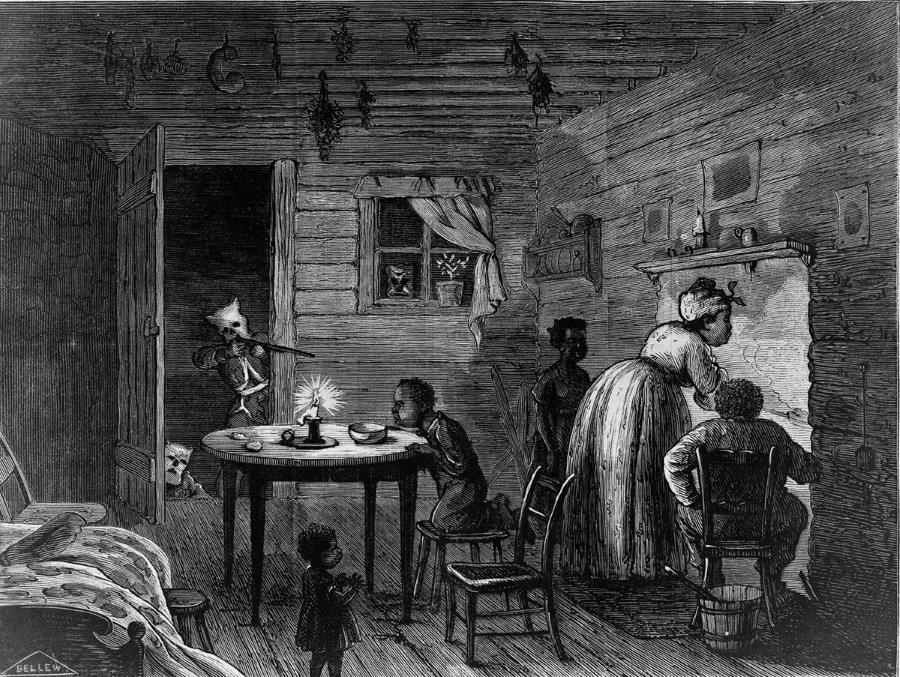

Visit of the Ku-Klux – Frank Bellew (1872)

|

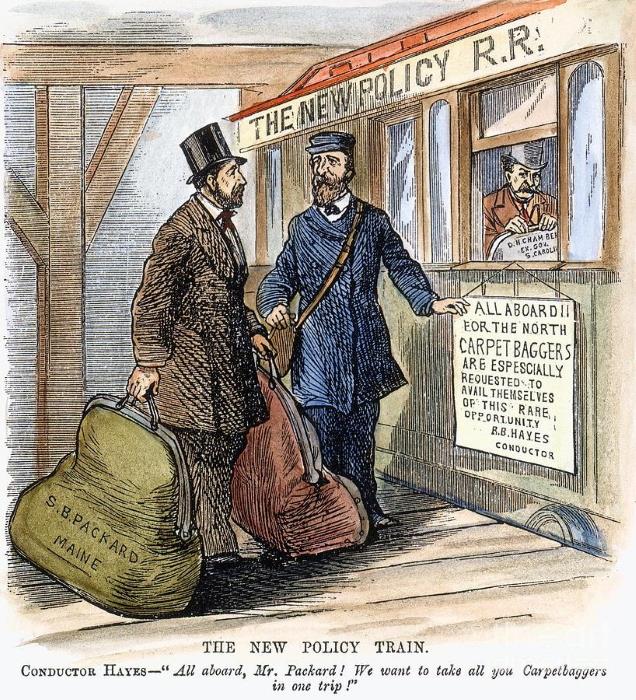

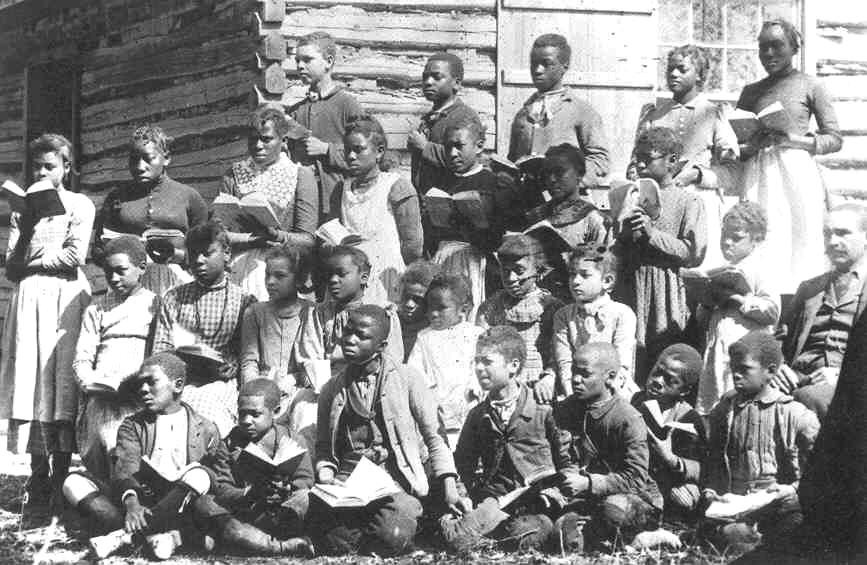

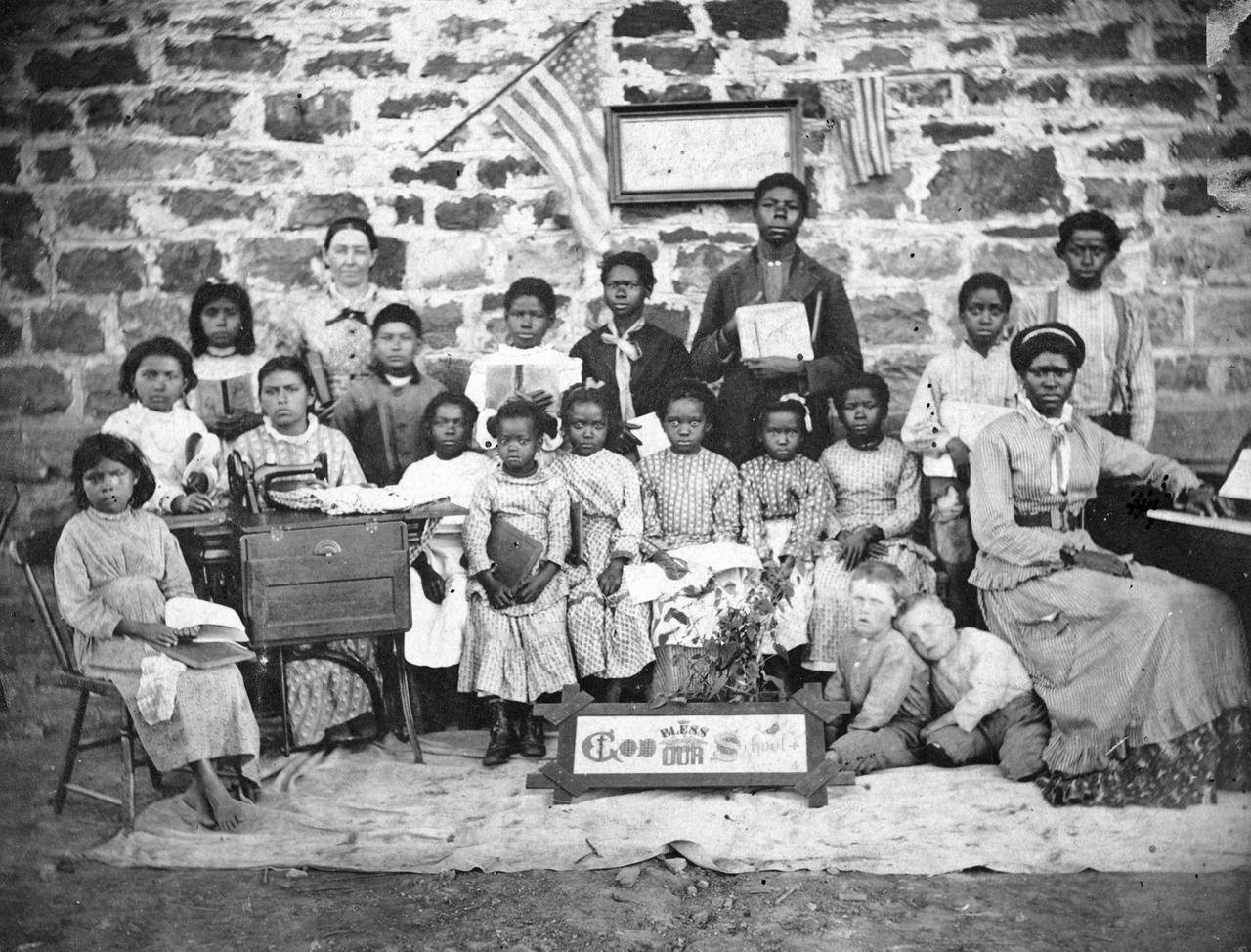

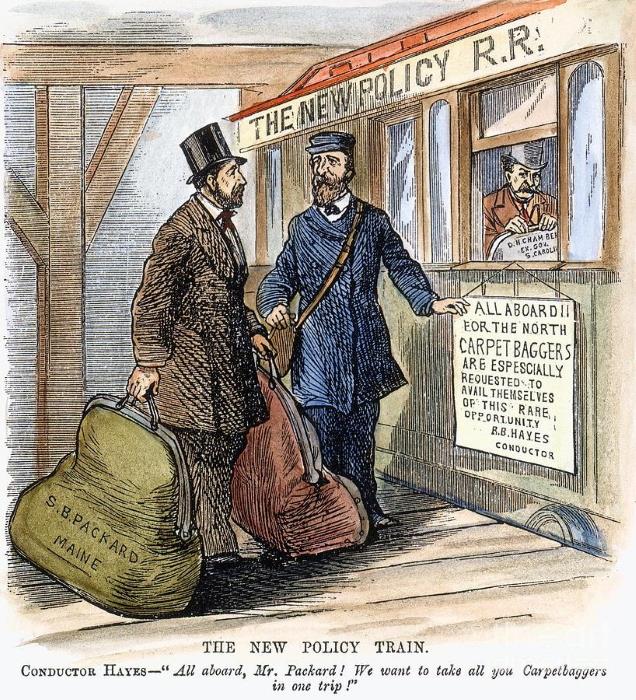

Facing this recalcitrant Southern attitude were

large numbers of Northern Whites who descended on the South, many sent

by the new Freedmen's Bureau, to help the Blacks make the transition

away from slavery. These "carpetbaggers"4

were disliked intensely by Southern Whites (especially the poorer

Whites), but they did help bring some education to thousands of Black

children (although absenteeism among Black students was very high and a

serious problem in trying to bring the Black population into mainstream

American culture).

These reformers were backed by an 1867

Military Reconstruction Act which stripped the South of its governments

set up under Johnson's liberal reconstruction policies. The new law

dismissed these state governments and divided the South into five

military districts commanded by Union generals and enforced by a

60,000-strong Union Army positioned throughout the South. And the terms

for readmission to the Union now required not ten percent but a full

majority of a state's citizens, which now included Black voters.

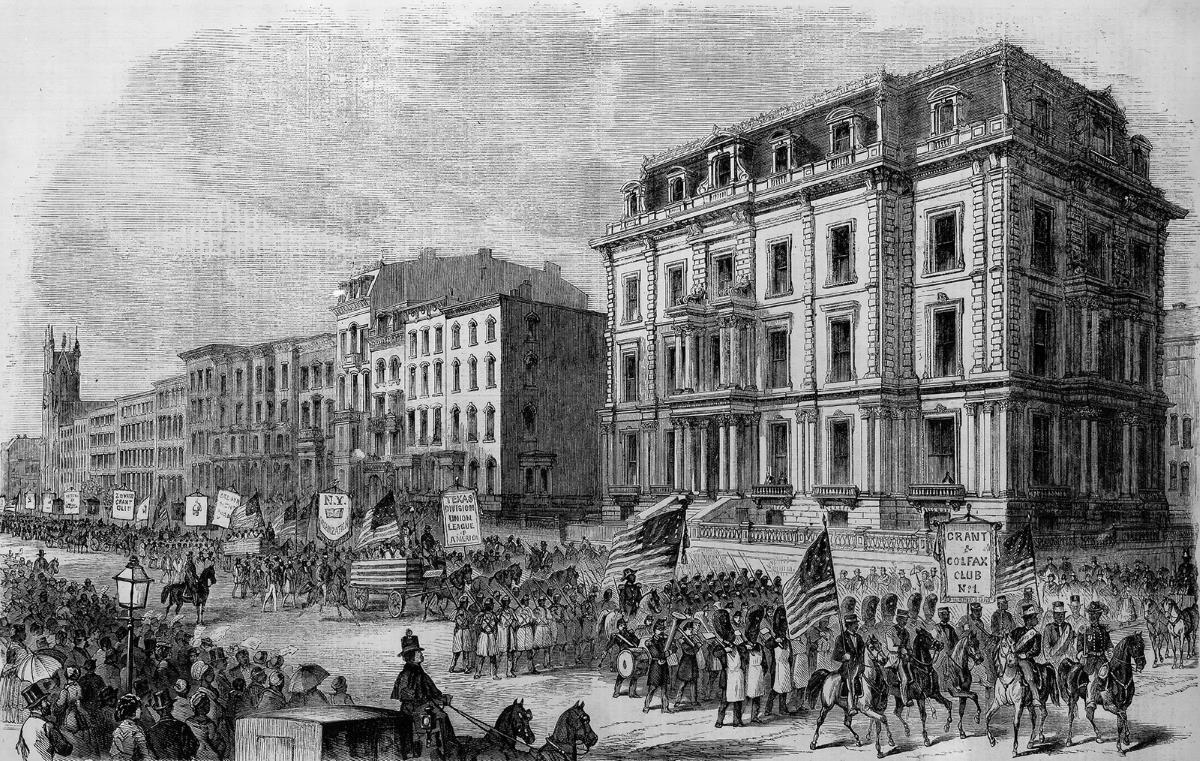

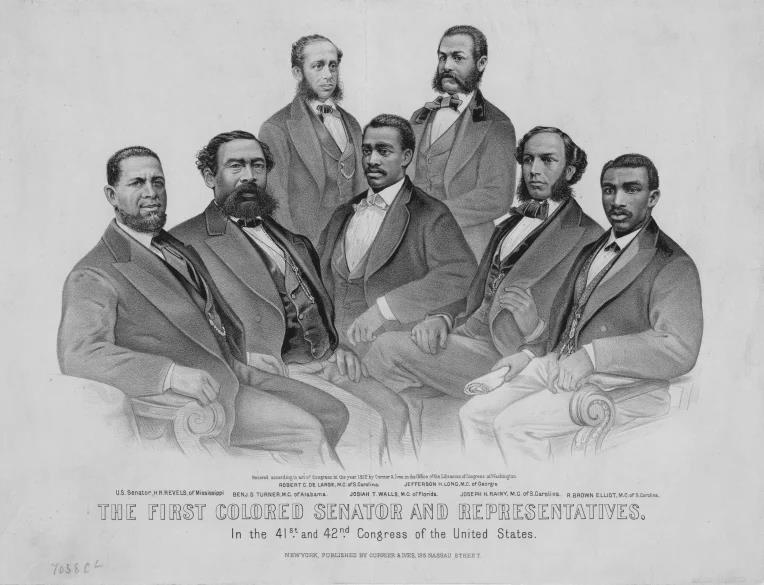

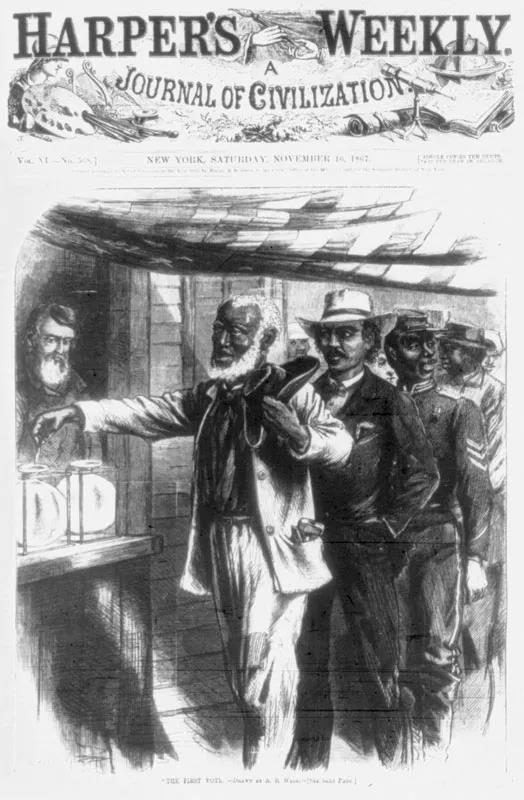

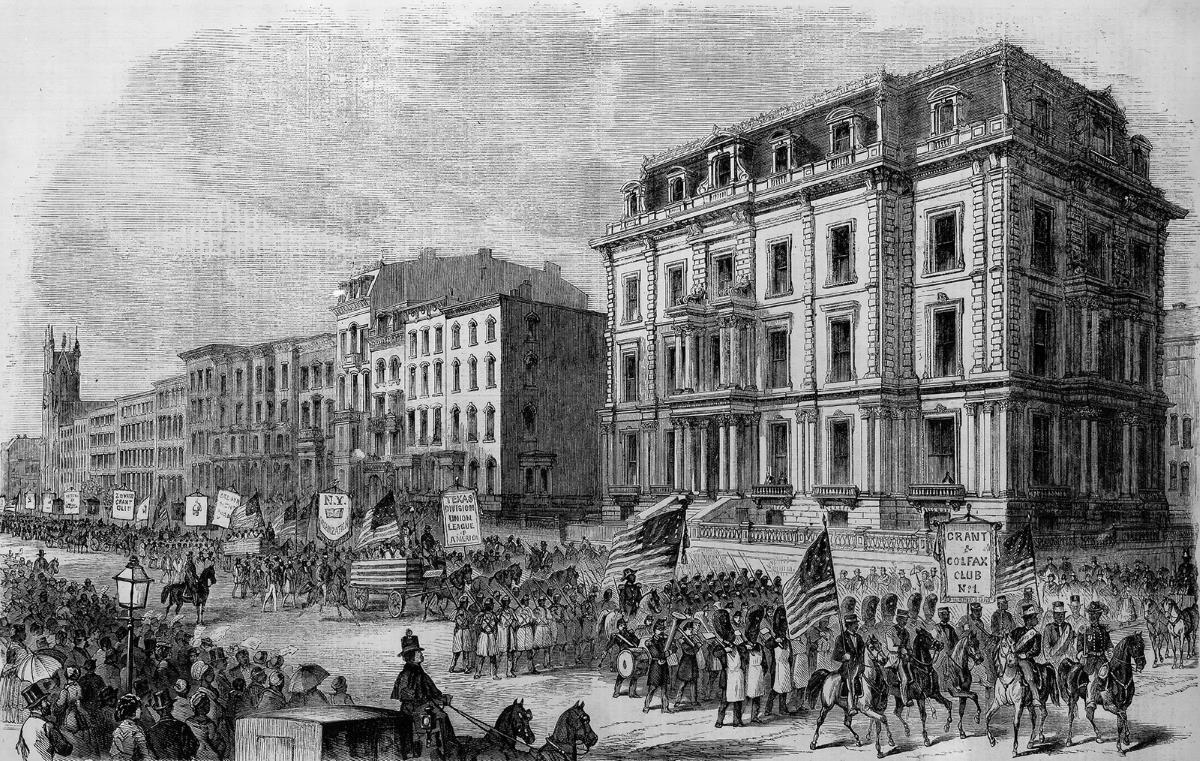

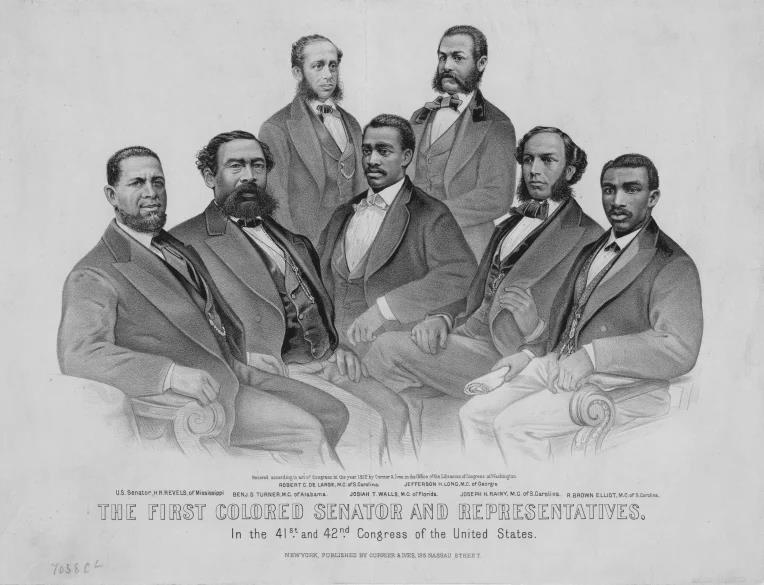

In fact, the tendency of White voters to

boycott the new elections advantaged considerably the Black vote. As a

result, the South saw its first Black politicians (almost universally

members of Lincoln's Republican Party) take their place in the states'

assemblies, and even in the nation's Congress.

None of this however served to bridge the

ever-widening emotional gap between Southern Whites and Blacks. But for

the time being – as long as this military administration was kept in

place in the South – there was little that Southern Whites could do

about a situation that they detested (including their anger directed at

the North for its "imperialistic" behavior).

4Named for the type of luggage they arrived with: a large bag made of heavy cloth or carpeting.

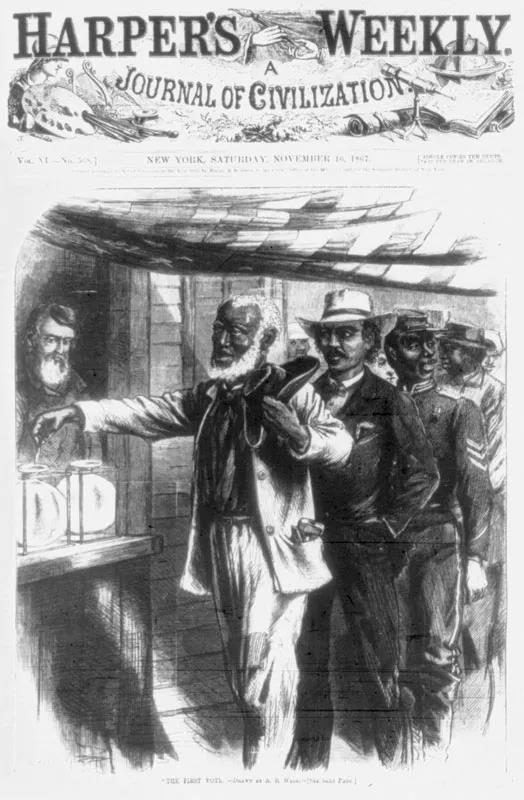

Blacks voting for the first time

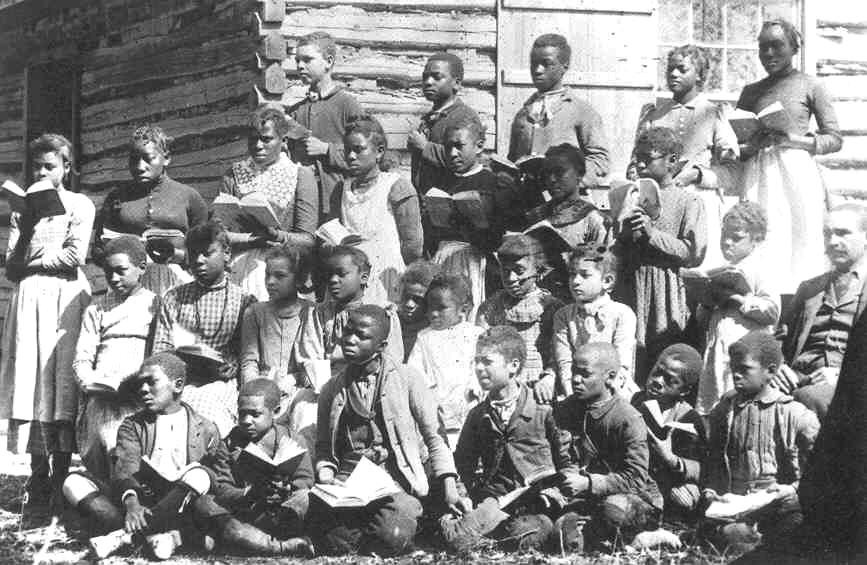

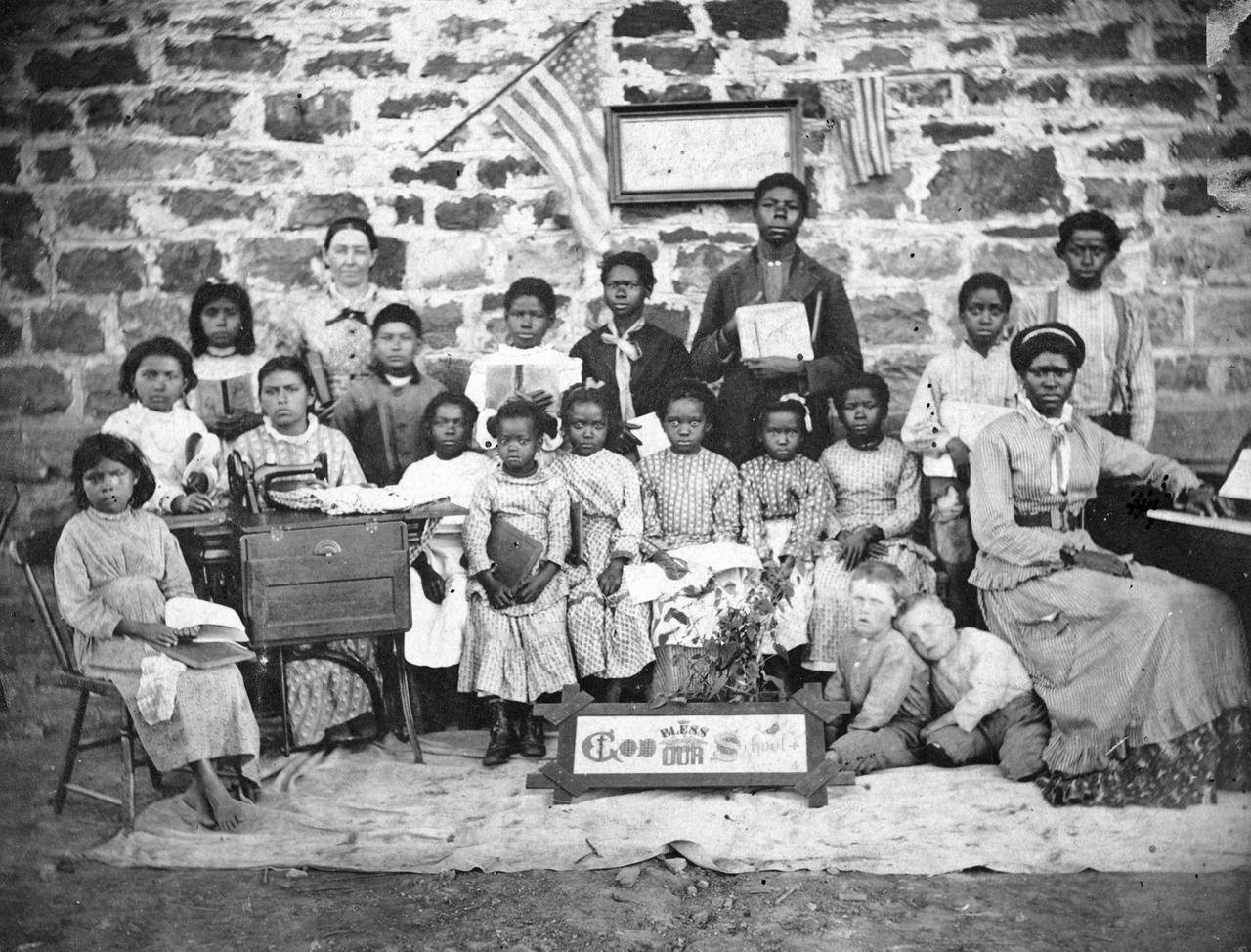

A Freedmen's Bureau school

for former slaves

Blacks marching in support of the 15th Amendment guaranteeing the right to vote despite race, color or previous servitude (i.e., slavery) – passed in Congress in February of 1869 and ratified a year later

Hiram Revels – First Black

Congressman

(appointed to serve a 1-year unexpired term in the Senate)

- 1870

Black Congressmen serving - 1869 to 1873

To gain the presidency in 1876, Hayes agreed to recall all Federal "Carpetbaggers"

from the South. This ended North-directed Reconstruction.

The South was on its own now.

| | | | |

Johnson and the Radical Republicans

Johnson and the Radical Republicans