10. AMERICA RECOVERS – 1865-1880

THE BATTLE FOR THE WEST

CONTENTS

The American-Indian Wars during the The American-Indian Wars during the

Civil War

The routes West The routes West

Cowboys and farmers Cowboys and farmers

The Indians' "Last Stand" The Indians' "Last Stand"

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 329-339.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1860s |

The Western frontier continues as a problem ... especially during the Civil War

1862 With the Civil War as

America's major military obsession, American Indians have resumed their attacks on

unprotected White settlers in the West ... with Sioux (Eastern Dakota) tribesmen killing

several hundred German settlers at New Ulm (Aug); Lincoln sends Federal

troops to stop the

attacks; 300 Indians are are convicted of murder ... though only 38 are

hanged

1863 Federal troops (led by Kit Carson) begin the round up

Navajo and Apache tribes ... in

order to relocate them to the bleak Pecos River region in New Mexico

1864 White

bitterness against Indians in the West brings ongoing conflict ... with

700 Federal troops attacking an

actually peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho community at Sand Creek, killing women and children ... while the men were away hunting buffalo (Nov)

In Northern Texas,

Federal troops under Carson moved to stop the Indian attacks on settlers following the Santa Fe

trail to the West ... and engaged a huge Comanche and Kiowa Indian coalition at the Battle of Adobe Walls (late Nov)

1867 The Chisolm

Trail is laid out ... to bring cattle north from southern Texas to the

railhead at Abilene Kansas

|

| 1870s |

The struggle for the West intensifies as White farmers pour into the region

1875 With the

invention of barbed wire, homesteads on the Great Plains can protect

farmlands ... but also serve to block

the movement of cattle herds across those plains from Texas to Kansas

1876 A huge Indian coalition (led by Sitting Bull) – attempting to drive Whites from the Dakotas and Montana – are confronted by Federal troops led by Sheridan; one of his divisions led by Custer is grandly defearted by

the Indians (Jun) at Little Bighorn River ... merely strengthening the

resolve of Whites to finally end completely "the Indian Problem"

|

| 1880s | The struggle continues

1880s The number of buffalo that once covered the Great Plains drops to almost the extinction level ... making life for the American Indian very difficult

|

| 1890s | The West is "won" for White America

1890 The Indians undertake a supreme effort to remove the White Man from their world ... taking up the Ghost Dance in the belief that this would make them immune to the White Man's bullets; Sitting Bull is arrested ... but killed by Indian police (mid-Dec) ;

At the same time (late Dec) federal troops attack Lakota Indians at Wounded Knee Creek, with numerous

Indians killed ... basically ending any further Indian idea of

resistance to White expansion

|

|

THE

AMERICAN-INDIAN WARS DURING THE CIVIL WAR |

|

Wars between the American settlers and the

American Indians had been going on, of course, virtually since the

arrival of Englishmen to the shores of North America in the early

1600s. Certainly they continued even while America was caught up deeply

in its Civil War – and particularly during those times – because

federal troops protecting settlers had been pulled from Western service

to fight the Confederacy. Thus the Civil War days saw some intense

fighting between the settlers and the Indians. There were hundreds of

Indian attacks in an Indian effort to drive the White settlers off

their lands. There was no sparing of women, children and the elderly as

these were battles of whole communities over the matter of land

ownership, vital to the survival of both Indians and Whites. In the

span of the four years of the Civil War over a thousand settlers' lives

were lost to these Indian attacks

The Sioux War in Minnesota

The most intense action occurred in

Minnesota in 1862 when Dakota tribes attacked German settlements at New

Ulm and Hutchinson, killing several hundred (300-400) settlers. Local

militiamen did what they could to hold back the Sioux, and Lincoln

quickly sent federal troops to help them. Battles thus broke out

between the federal and Indian troops over a six-week period, resulting

finally in breaking the Sioux offensive. Over 400 Sioux were

subsequently arrested, 300 of which were convicted of murder and

sentenced to be hanged. Lincoln however pardoned most of them (much to

the great irritation of local White authorities) and only thirty-eight

of them were subsequently hanged, the largest such event nonetheless in

American history.

Ultimately such Indian attacks brought a

bitter White response, in the form of countering attacks of White

militia and federal troops on the Indians. There was an attempt to be

fair in the size of the response. But the anger raging between both

sides made this a matter very difficult to manage. A huge and

unwarranted loss of Indian life during this period occurred at Sand

Creek in eastern Colorado in late November of 1864, when some 700

federal troops attacked a peaceful community of Cheyenne and Arapaho

Indians, most of whose men were away hunting buffalo. 130 were killed

or wounded, mostly women and children but also a number of the members

of the Cheyenne Council, tragically those most supportive of the idea

of peace with White society. This action thus strengthened the hand of

the pro-war Indian Dog Soldiers. It also brought into action a federal

court of inquiry and condemnation of the federal officers involved. But

no other punishment resulted.

Kit Carson and the Navajo, Kiowa, and Comanches Kit Carson and the Navajo, Kiowa, and Comanches

Meanwhile in the American southwest, action

led by Union General Carleton – but carried out largely by the living

legend Kit Carson1 – was

undertaken in early 1863 to round up the Navajo and Apache tribes and

move them to a reservation along the bleak Pecos River, where they

could be more easily prevented from making raids on the White settlers

in the New Mexico Territory. The roundup proved difficult because the

Indians knew how to hide themselves in the mountains, driving Carson to

take harsher measures to break the will of the Navajo (the ones who had

not already joined the Apache in a flight to the West to form an

anti-White army.) By early 1864 Navajo resistance had been broken and

thousands of them were rounded up and sent off to the reservation,

where many died of cold and hunger. Eventually they were allowed to

return to their former homes, though as a submissive people.

By late 1864 Carson had turned his

attention to the Kiowas and Comanches who had been conducting raids on

White settlements in the Texas Panhandle region. In November Carson and

his men met a grand Indian coalition of several thousand warriors at

the Battle of Adobe Walls. Carson's men were vastly outnumbered and

quickly out of ammunition and thus forced to retreat, but managed to

inflict massive casualties on the Indians in the process. This battle

proved to be a turning point in the Indian wars in the region, greatly

undermining the power of both tribes and ultimately bringing the Kiowas

and Comanches to sue for peace in 1865.

1Penny novels were already being written about his exploits as a mountain man and Indian hunter.

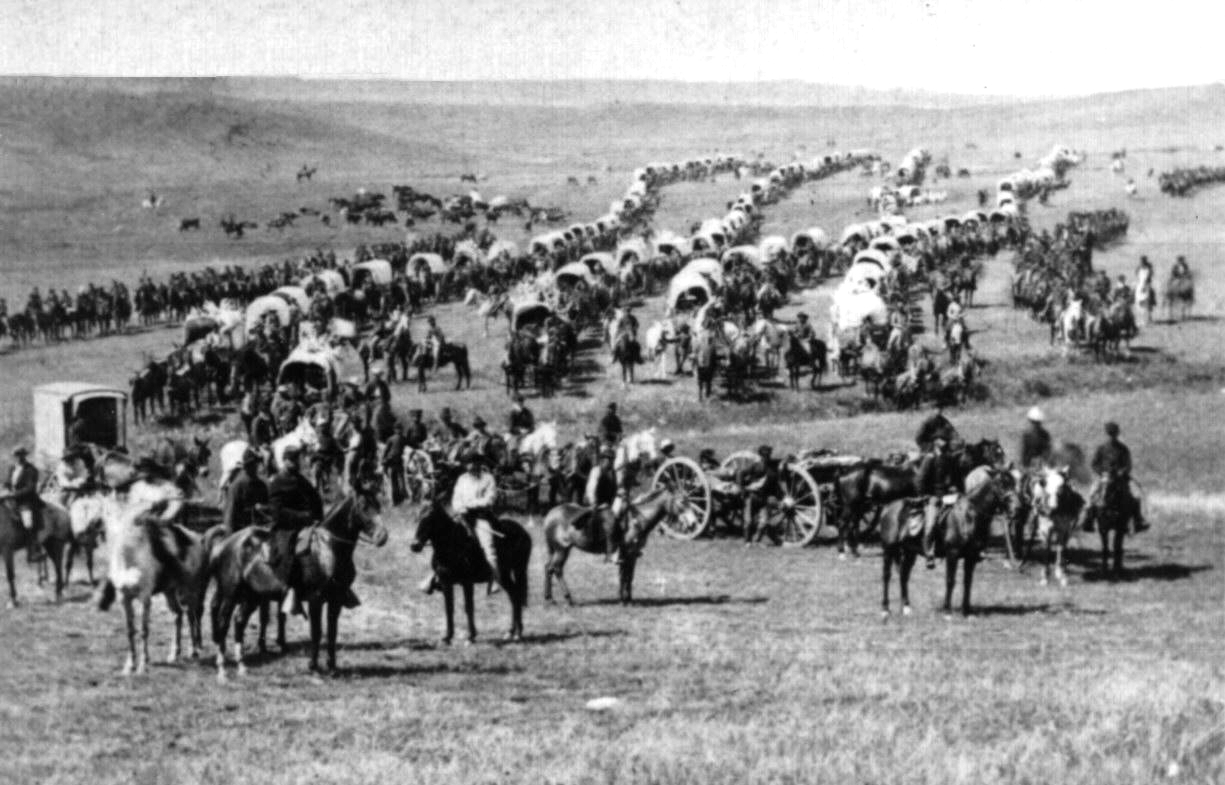

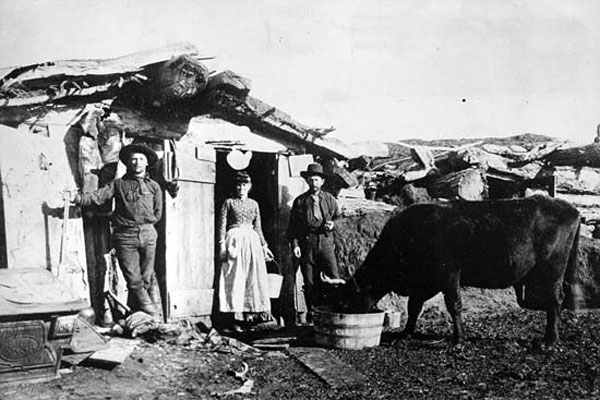

Settlers under militia protection

during the Dakota or Sioux War of 1862 in Minnesota

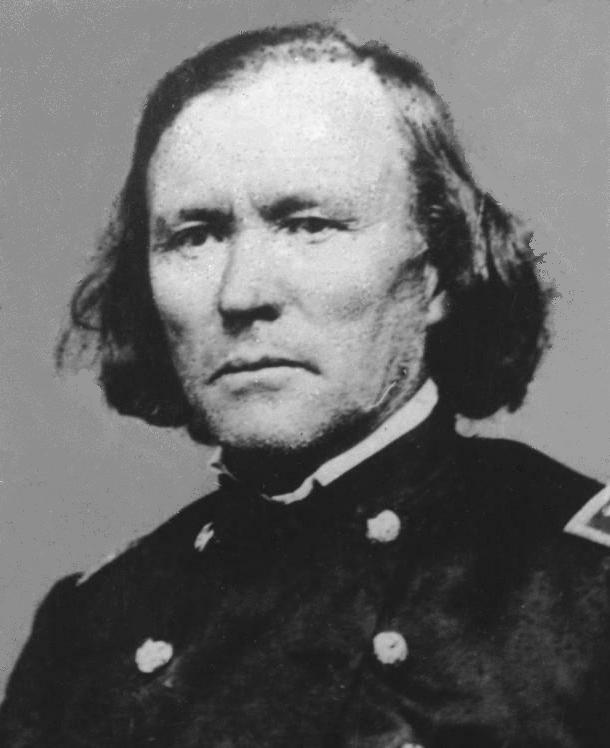

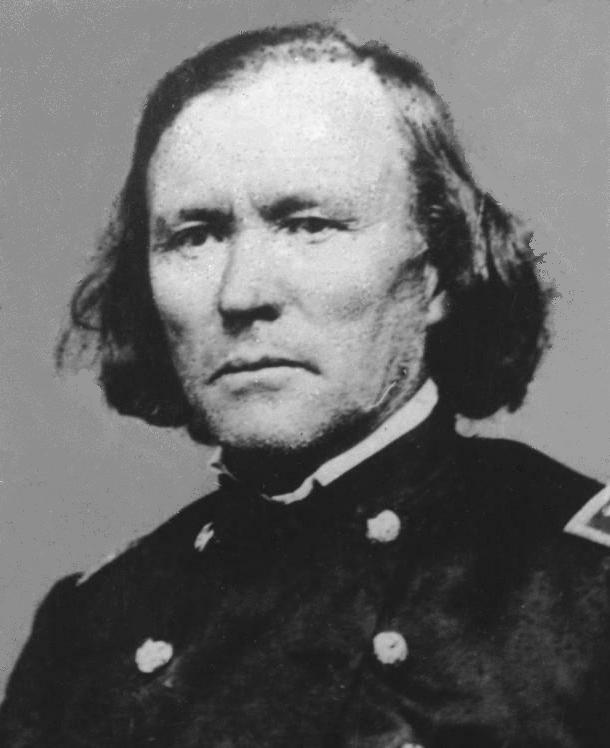

Lt. Colonel George

Armstrong Custer with his favorite Indian scout, Bloody Knife (kneeling

left)

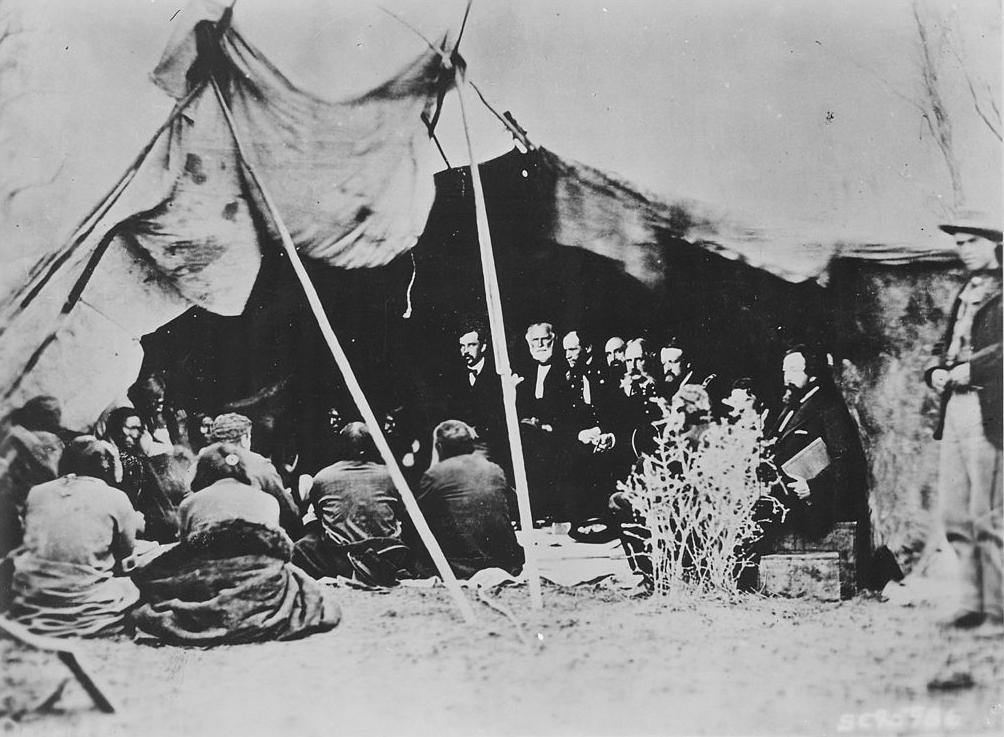

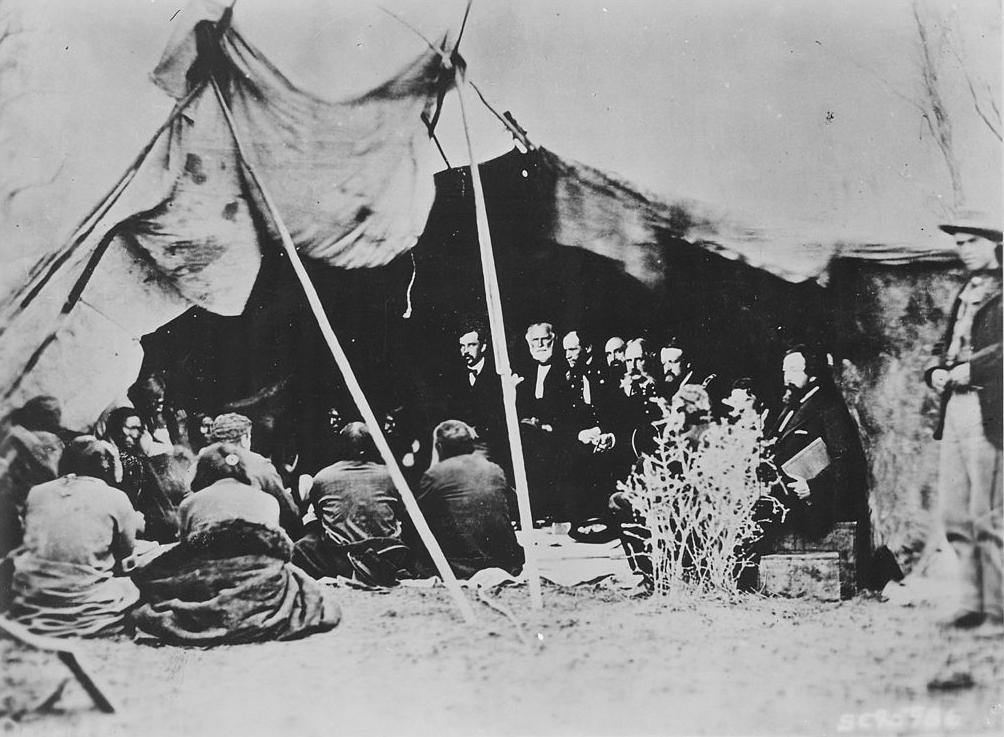

Gen.

William T. Sherman and commissioners in council with Indian chiefs at Ft. Laramie,

Wyoming – ca. 1867-1868

The National Archives

|

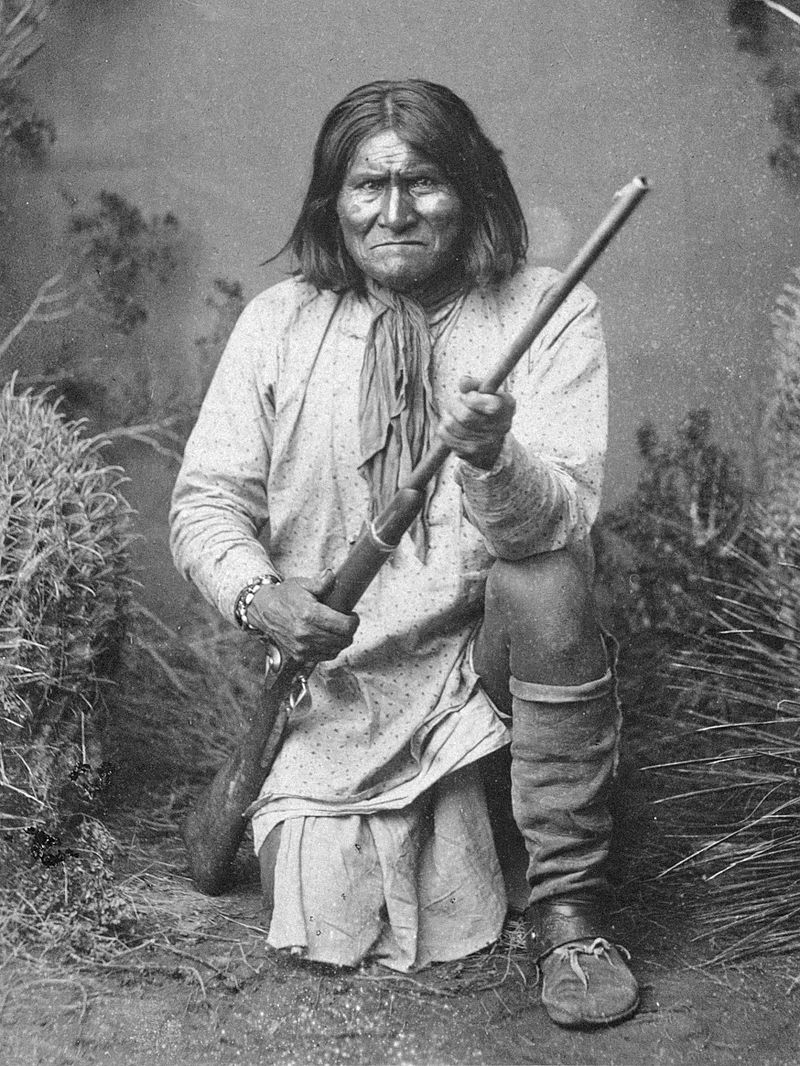

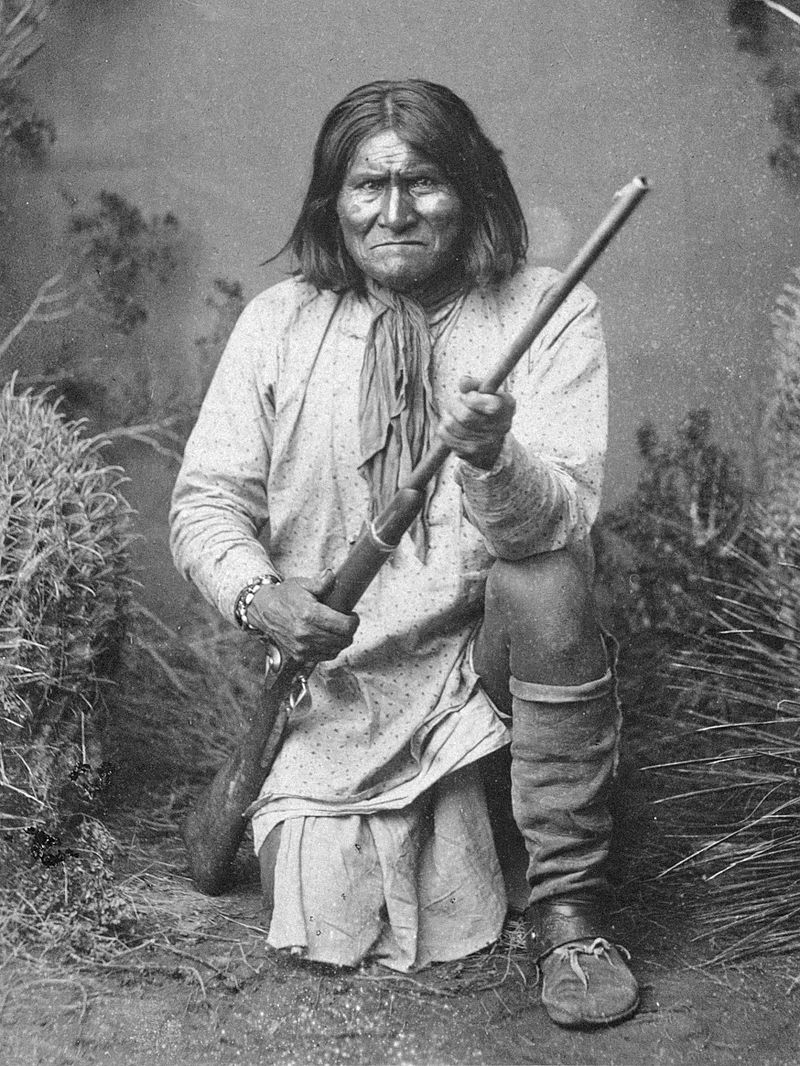

Geronimo and his Apache raiders

But alongside Kit Carson, the Indians could

provide heroics of their own, such as the Apache raider Geronimo. He

was part of a military tradition that reached back to the wars earlier

in the 1800s between the Apaches and the Mexicans. These wars were

constant and without definitive results. Then when the American

frontiersmen came on the scene, Geronimo included their settlements in

his raids. He actually never commanded a band larger than forty or

fifty warriors. Yet his skills brought his name to some kind of fame

among the Apache – and the White settlers as well! He eventually was

forced into retirement on the Apache reservation by the U.S. military

(with also Mexican cooperation), breaking out three times between 1876

and 1886 when he grew restless under the restrictions of reservation

life. Eventually he and his Chiricahua tribe were moved to Florida and

then to Oklahoma. But his name was so well known that several times he

was featured at several major expositions back East and even rode

horseback (in native attire, of course) in Teddy Roosevelt's inaugural

parade in 1905!

|

Apache warrior Geronimo

A scene in Geronimo's Apache Natches' camp prior to surrender to Gen. Crook -

March 27, 1886

The Library of Congress

A band of Apache Indian prisoners at a rest stop beside a South Pacific

train – Sep 10, 1886

Among

those on their way to exile in Florida are Natchez (center front) and,

to the right, Geronimo and his son in matching shirts.

The National Archives

|

The grand Western migration

On they came – White men, women and children – by

steamer or river barge (as far as the rivers would take them westward),

then by wagon train, following trails set out by trail-blazing

frontiersmen, and eventually by train as the American railroads pushed

West and Southwest deep into Indian lands. They laid claim to railroad

land and set up their own farms, as well as towns to service the

fast-growing farming world of the West.

Some such as the Mormons came looking for

religious utopias, much in the manner that had brought the Puritans to

America in the early 1600s. Indeed, Brigham Young's Mormons were

particularly successful in this matter, developing communities centered

on their City of Zion of Salt Lake City (founded by Young in 1847), but

reaching far and wide from Utah into Idaho, Arizona, Nevada,

California, Colorado, and even northern Mexico.

In 1857 a war began to brew between the

Mormons and the U.S. government, the latter in 1850, after having

secured the area from Mexico in the Mexican-American War, declaring the

region to be off limits to the practice of polygamy (a common practice

among the Mormons). U.S. troops were sent to Utah to enforce the ruling

against the rebellious Mormons, although the Mormons fought back mostly

by simply refusing to supply the troops with needed food and material.

Then in the summer of 1858, just as the Mormons were making a move to

leave Utah, pressure from Congress brought U.S. President Buchanan to

declare an end to the Mormon suppression. The war was now officially

over and the Mormons returned to their homes in Utah.

One unfortunate result of the war however was the massacre2

by Mormons (disguised as Indians) in 1857 at Mountain Meadows in

southern Utah of a party of 120 to 140 adult Arkansas "Gentiles"

(non-Mormon Whites) passing through Mormon territory with a huge herd

of cattle on their way West to California. All were killed, except

children under six who were spared however and taken in by Mormon

families. Blame for the massacre was never fully ascertained (Young

claimed to have had no involvement in the decision to execute the group

of Gentiles), and only in 1877 was one of the supposed perpetrators

finally successfully tried and executed.

The

rumors of gold (but also silver and

copper) also brought Americans west, though not usually entire families

but instead merely single male fortune hunters. States such as

California, Nevada (with its fabulous Comstock Lode), Montana, Idaho,

and Washington were states particularly sought out by these fortune

hunters. Towns would quickly appear wherever mineral sites were

discovered, bringing not only the fortune-hunting miners, but also

barkeeps and prostitutes to entertain the miners, but also bankers,

clergy, and general store operators to bring some degree of American

civilization to the towns as well. Then when the mines yielded up all

their bounty, everyone moved on to opportunities elsewhere – and then

yet another bustling mining town would turn into a deserted ghost town.

2The

decision to massacre the entire group was made when the Mormons feared

that some of the Gentiles had discovered that their attackers were

Whites (Mormons) and not really Indians.

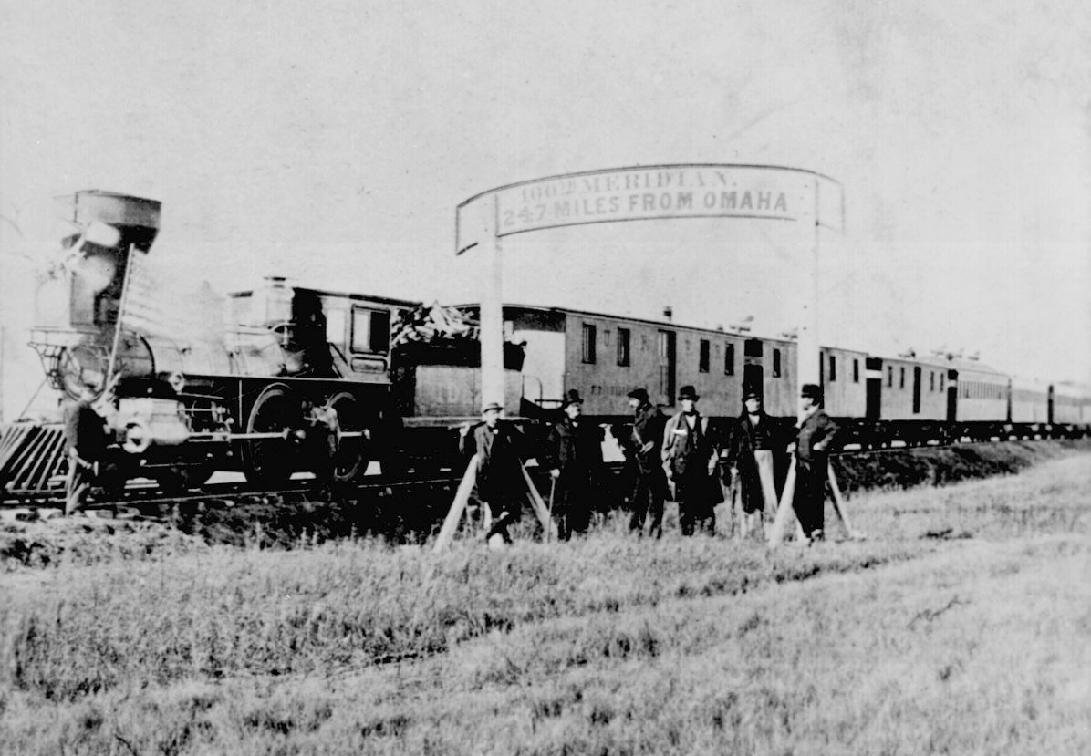

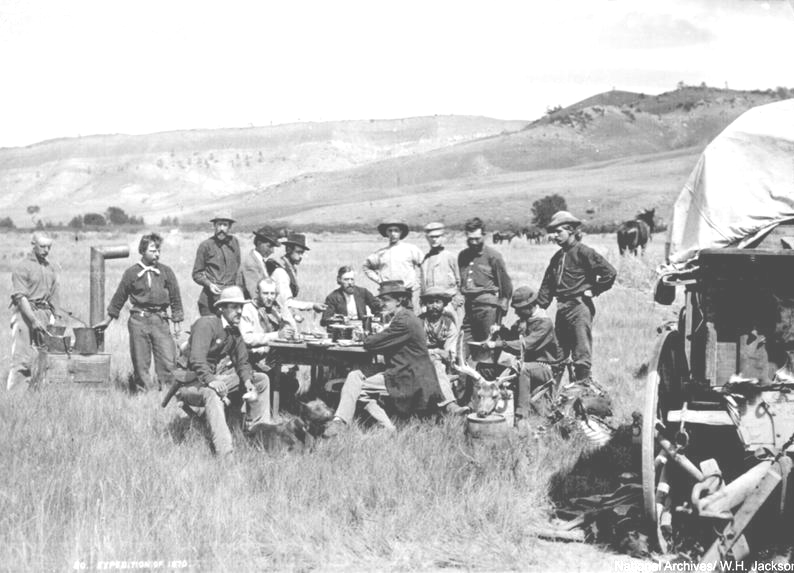

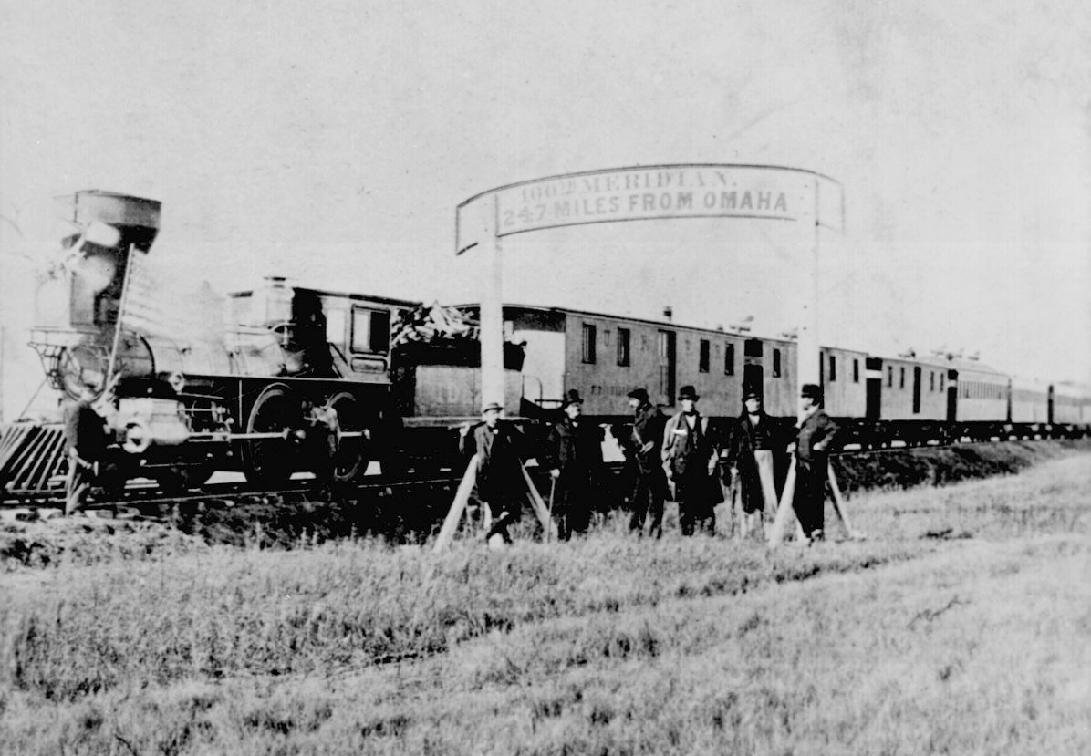

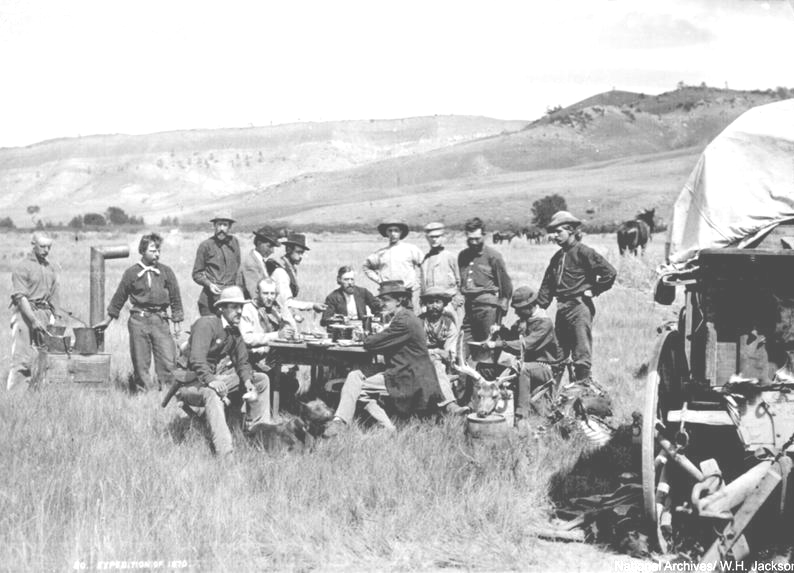

Directors of the Union

Pacific Railroad, approximately 250 miles west of Omaha -

1866

The train in the

background awaits the party of Eastern capitalists, newspapermen and other

prominent figures invited by the railroad executives

The National

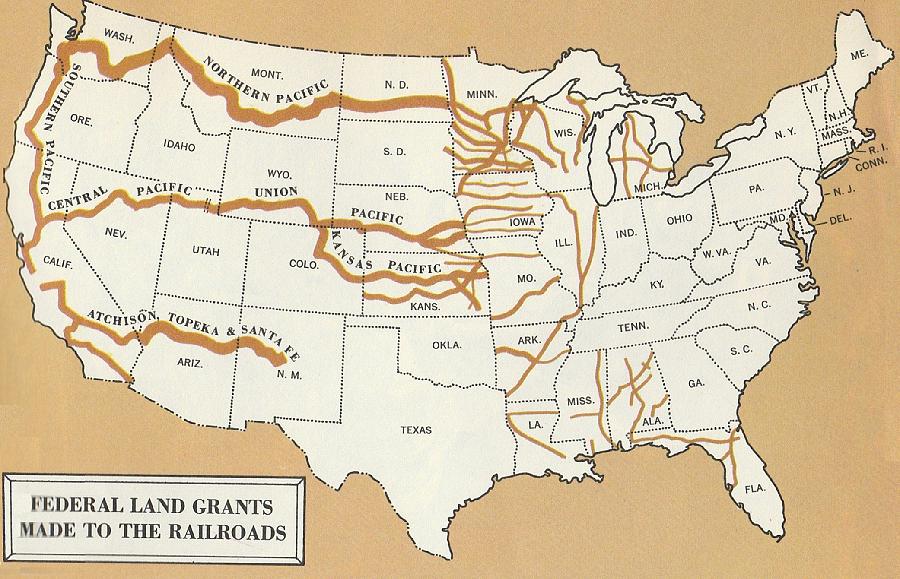

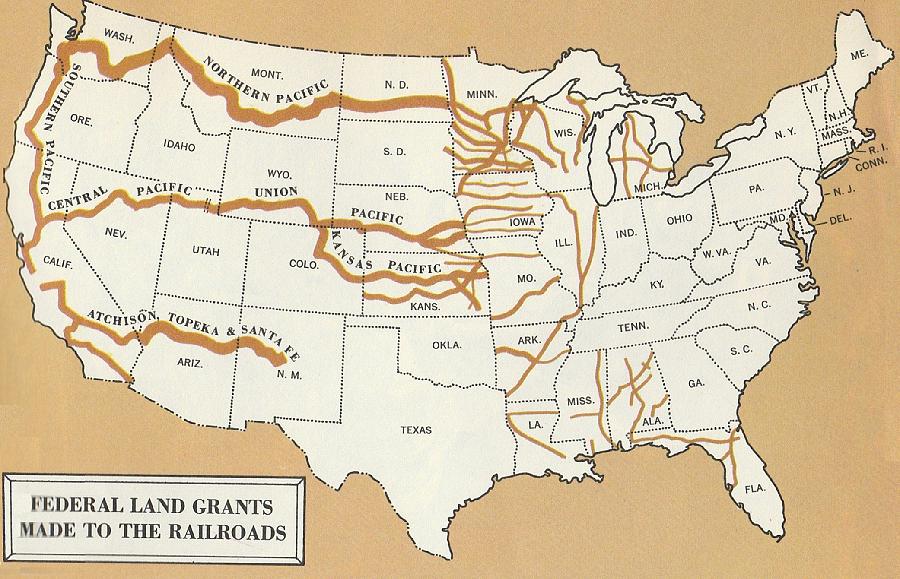

Archives  Approximate areas of federal land grants to the railroads are shown by the dark lines on the map. Part of the cost of building these railroads was met by selling some of this land to farmers who came to settle there. Approximate areas of federal land grants to the railroads are shown by the dark lines on the map. Part of the cost of building these railroads was met by selling some of this land to farmers who came to settle there.

American Heritage New Illustrated History of

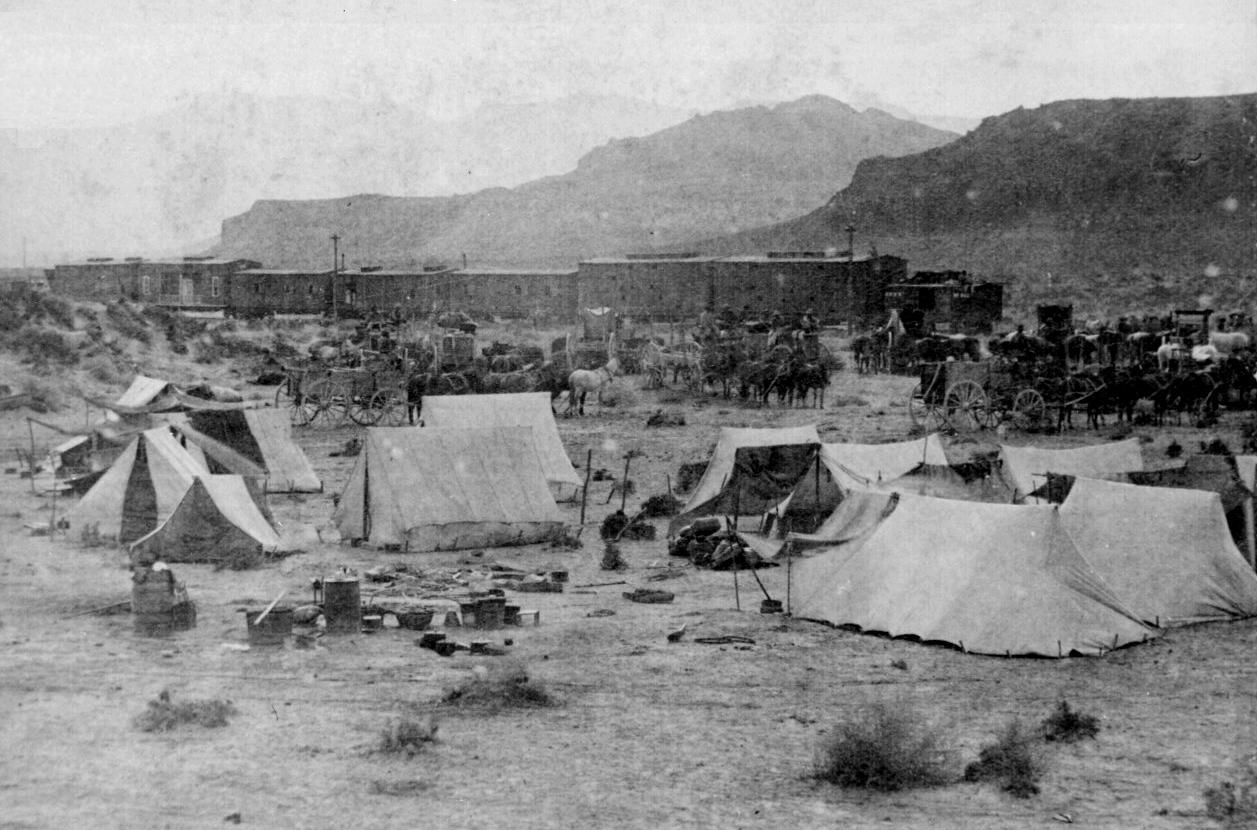

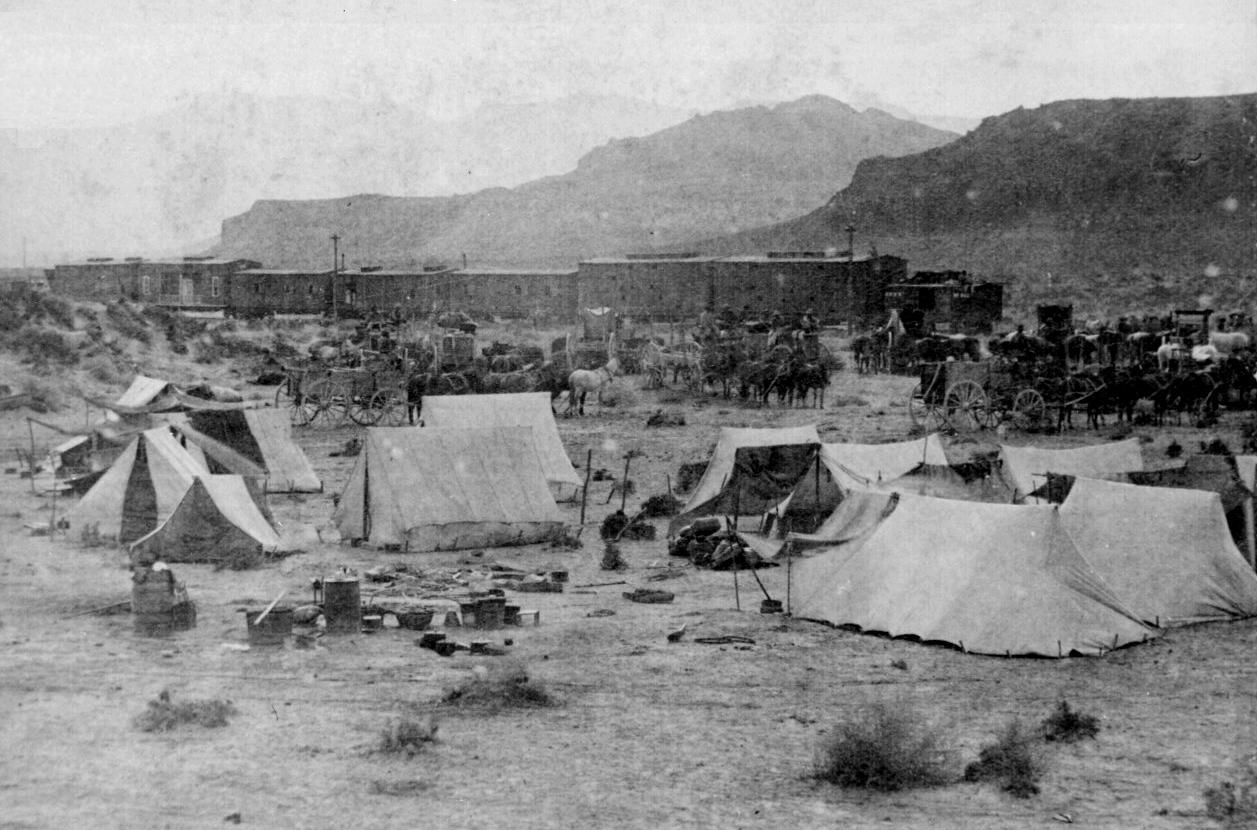

the United States, 1971, p. 853 End of the track – near Humboldt River Canyon -

1868

Campsite and

train

of the Central Pacific Railroad at the foot of mountains

The National Archives  Joining the tracks for the first

transcontinental railroad, Promontory, Utah Territory – 1869 Joining the tracks for the first

transcontinental railroad, Promontory, Utah Territory – 1869

The National Archives

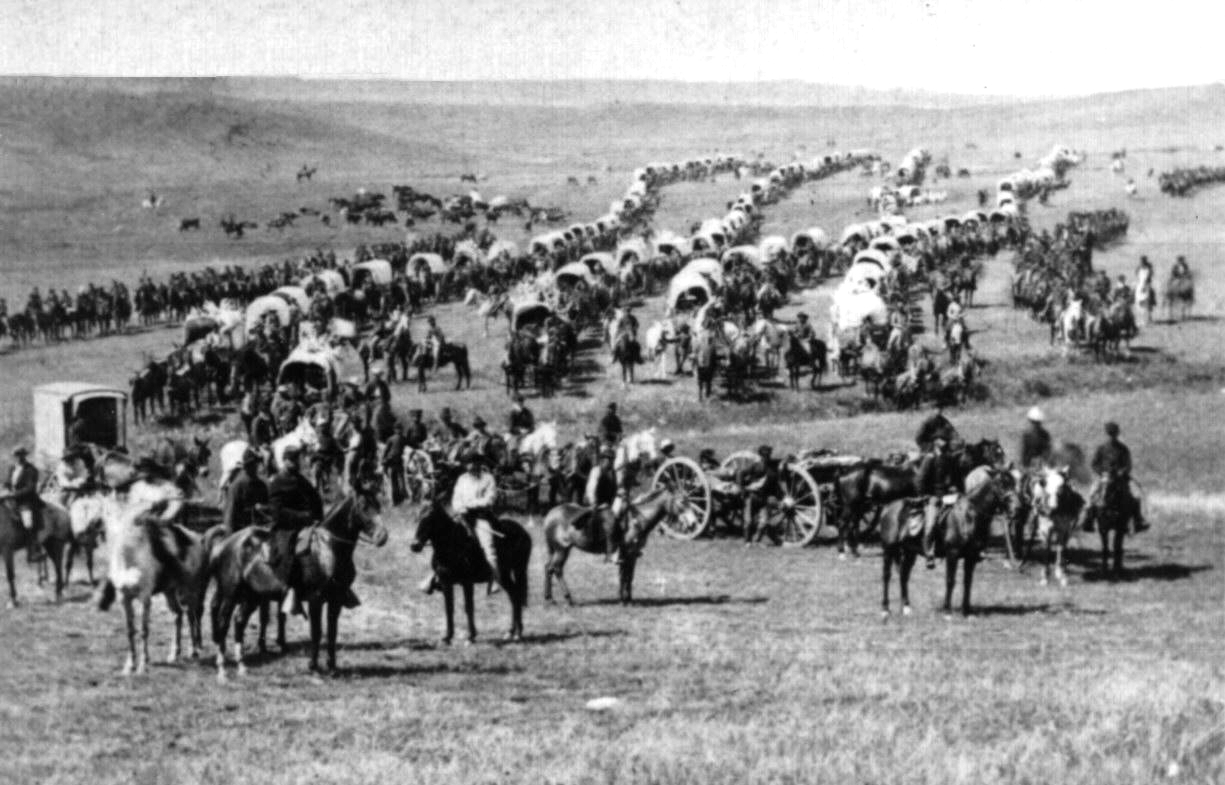

A column of cavalry, artillery, and

wagons, commanded by Gen. George A. Custer,

crossing the plains of Dakota

Territory – 1874 Black Hills expedition

The National Archives

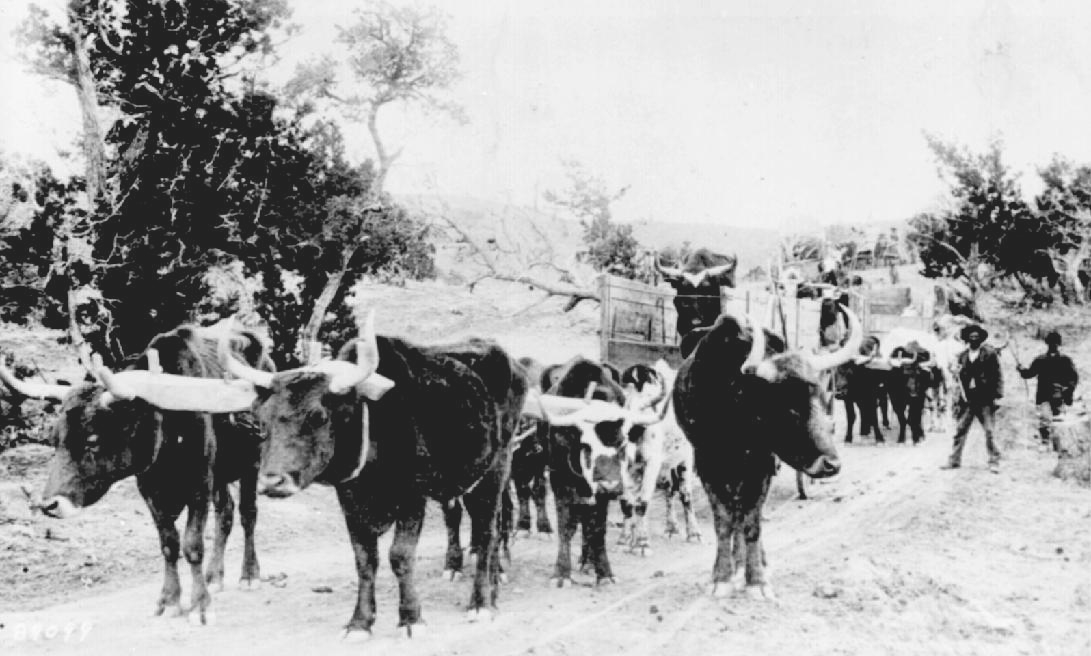

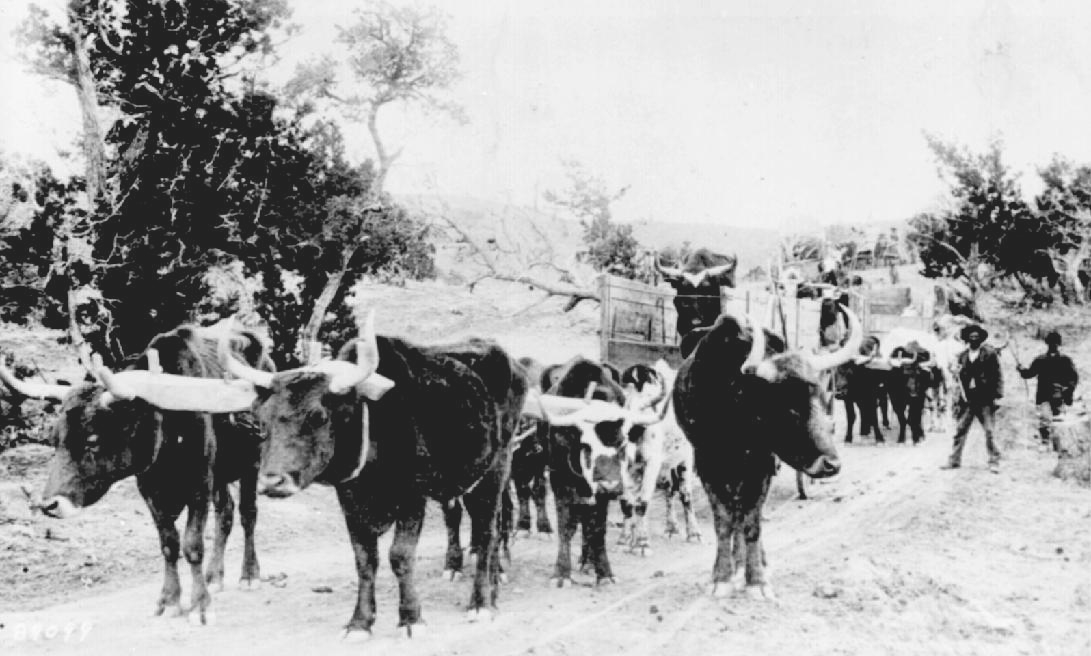

An ox train used to transport supplies in the

Arizona Territory – 1883

The National Archives

|

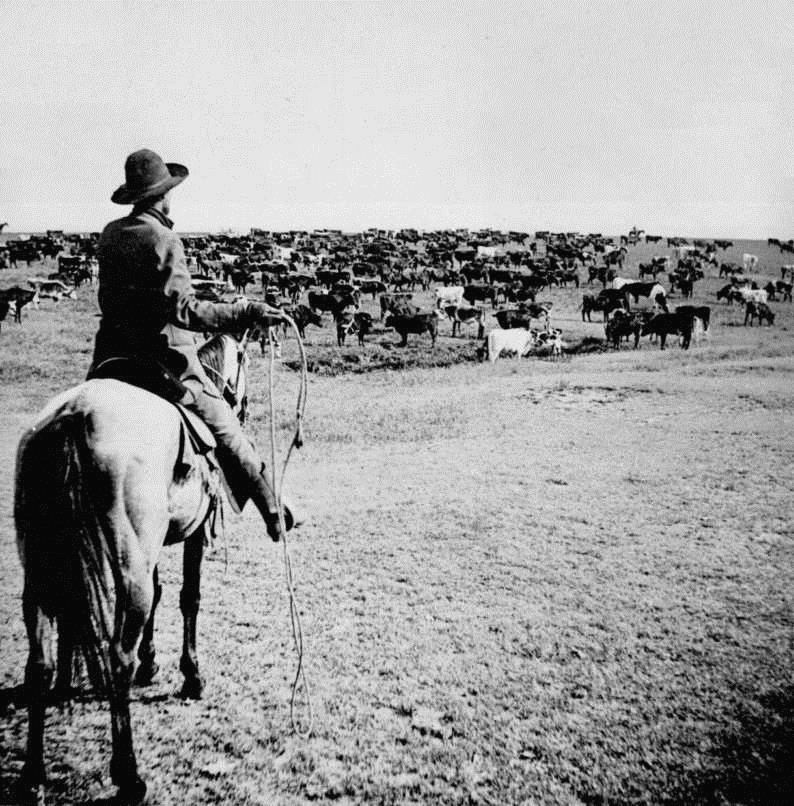

The West's Cattle Kingdoms (1860s–1880s)

Cow trails and cattle barons.

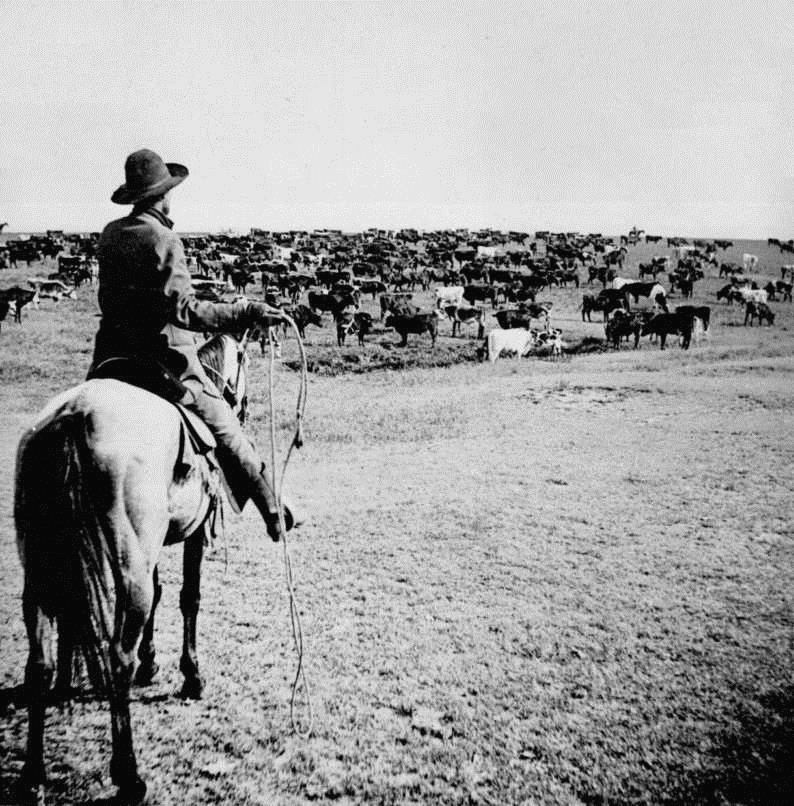

With the advent of the railroads into the West, new opportunities

opened up for the lucrative trade in beef cattle. Thousands of cattle

would be herded north from the grasslands of Texas, through the Indian

territory of Oklahoma, to the various railheads of the Kansas Pacific

Railroad. For instance, in 1867, when the new Chisholm Trail was first

laid out, 35,000 head of cattle were brought up from Texas to the

railhead at Abilene in that first year alone. From Kansas the cattle

were then herded onto boxcars and shipped up to Chicago (or west to

Denver for shipment to the Pacific coast). In Chicago the

slaughterhouses would be kept busy preparing meat to be shipped up the

Great Lakes waterway to the populous Eastern cities.

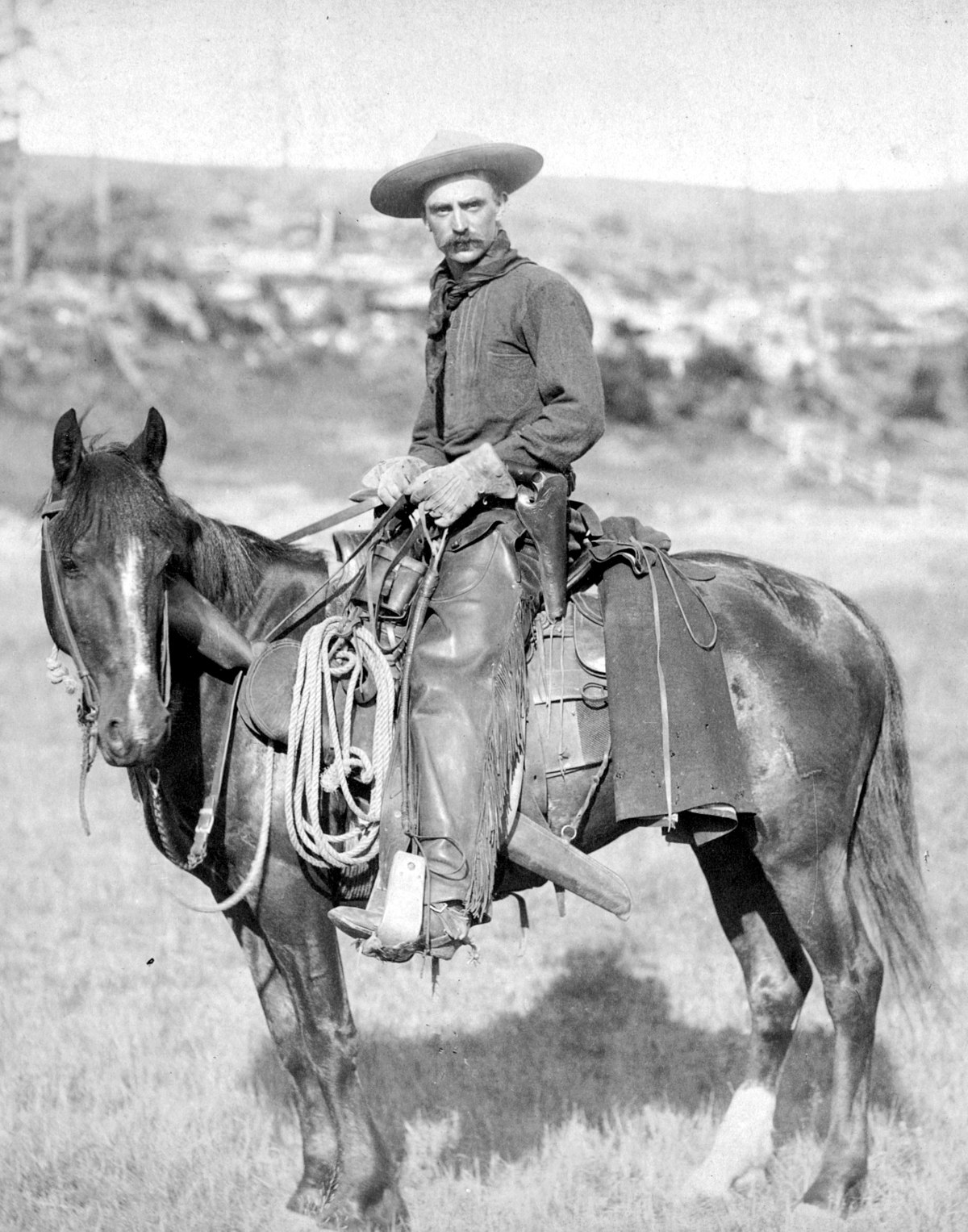

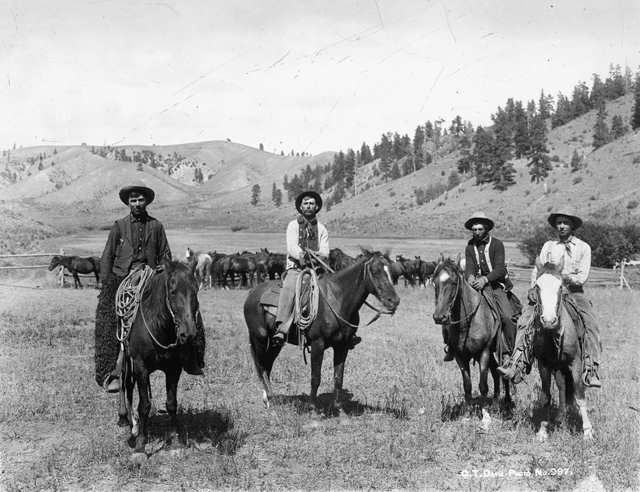

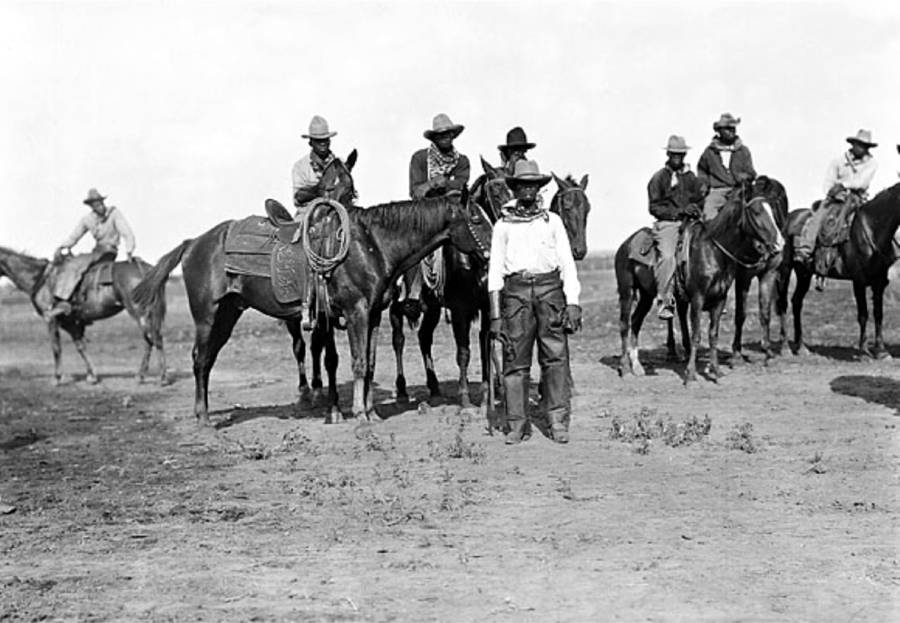

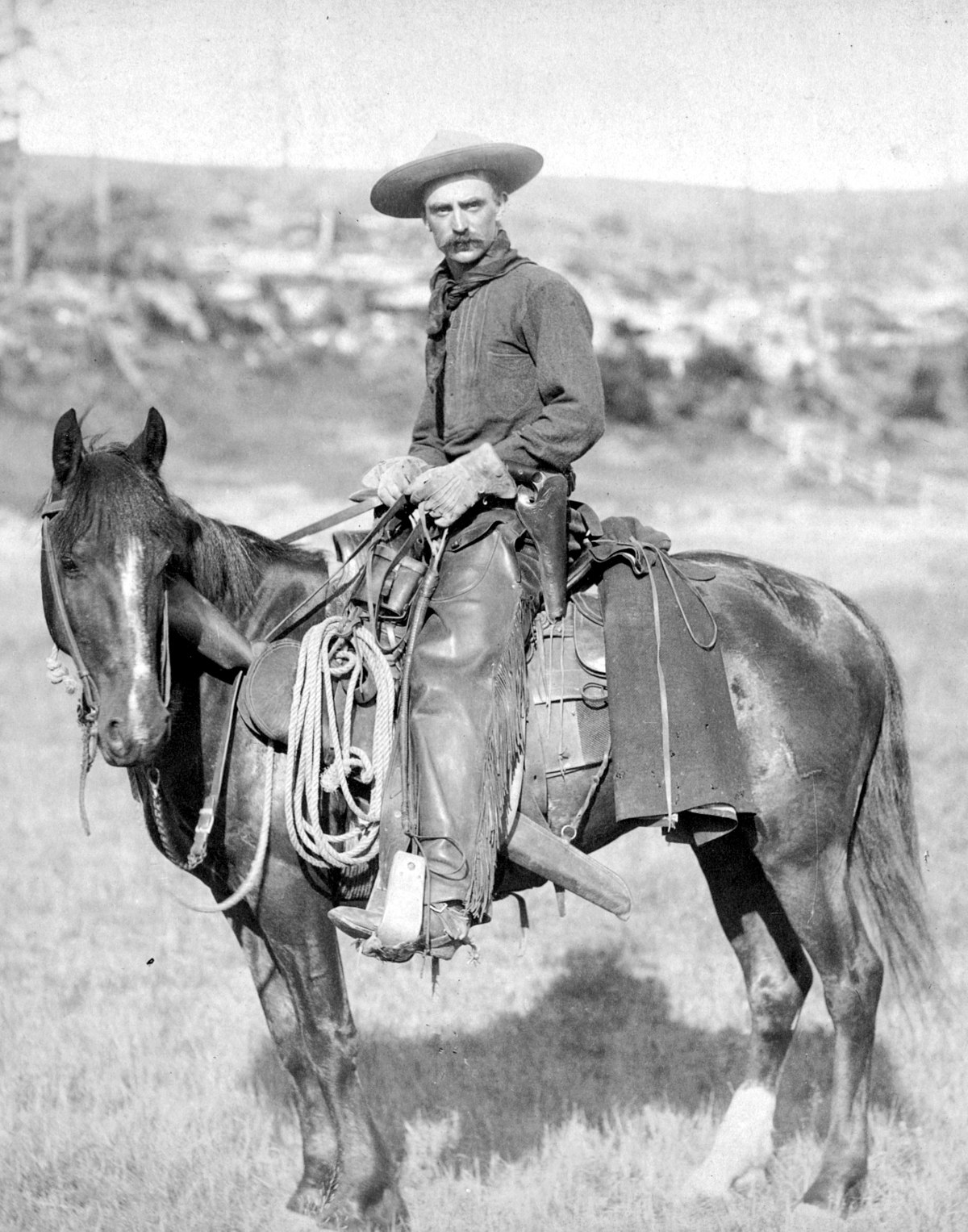

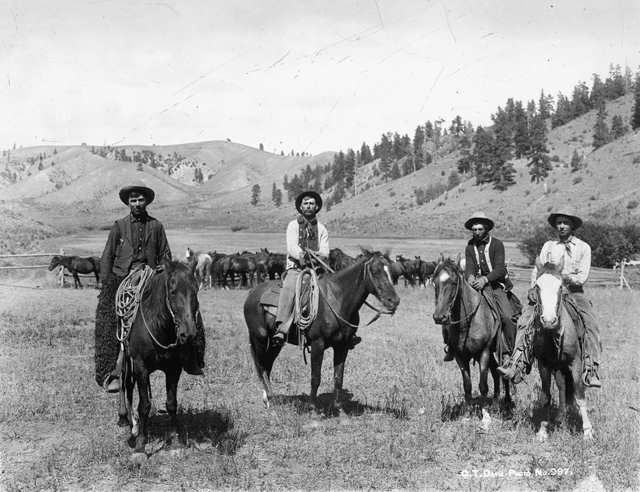

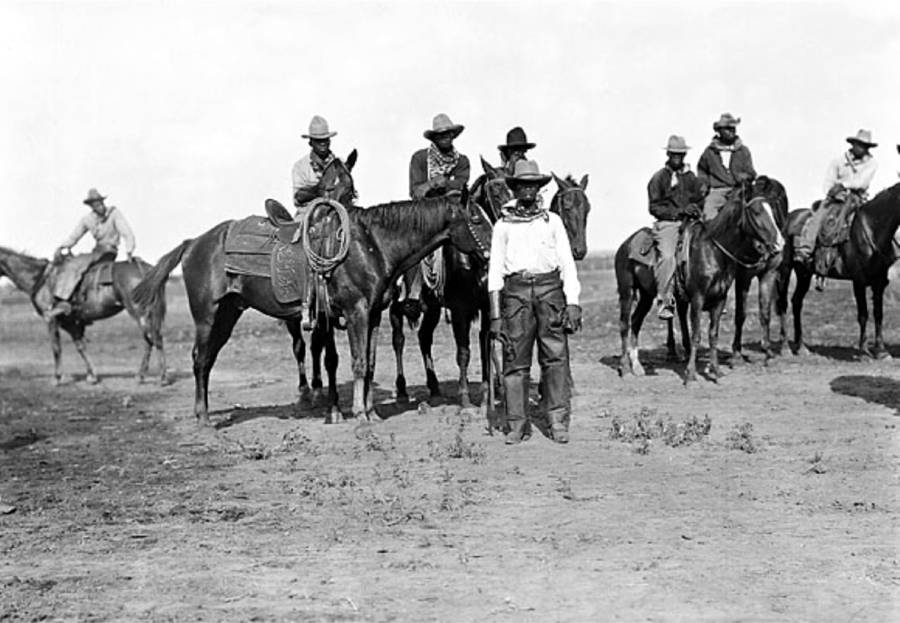

The fabled cowboy.

From the end of the Civil War to the mid–1880s the cattle business

boomed, making a lot of cattle barons very rich – and creating a fabled

American proto-type, the American cowboy. The battalions of cowboys

conducting these drives were hard-working, hard drinking, young men on

whom endless popular stories of American fortitude would be based. They

were a restless lot, not destined to set down family roots while they

remained in the business of cattle herding. Greatly exaggerated however

were the multitude of stories of gun battles conducted by them in the

Kansas bars, where, being finally paid for their work, they were

supposedly emboldened by booze and prostitutes to the point of

murderous manliness (but still, these stories made for great reading!).

Nonetheless, the cowboy exemplified a spirit that seemed to simply roll

out of the manliness demanded of the American male during the Civil

War. The cowboy was, indeed, an inspiring symbol of a young,

aggressive, expansive America, a nation with a growing sense of destiny.

|

|

But three things would bring this era to a close:

the steel-bladed plow, the barbed-wire fence, and the overgrazing of

the cow trails. The grassy plains through which the cattle trails led

were covered by a thick undergrowth of tough grass with deep roots,

which made the land prohibitively difficult to plow – that was until

the steel plow began to come under wide usage (sometime in the 1870s

and 1880s). With this invention, homesteaders could now begin to settle

the plains, with their plowed fields and domestic animals able to

support the lives of their families. To protect their investment, they

began to secure their landholdings by the relatively cheap means of the

new barbed wire fencing (developed in the mid–1870s).

Now the cattle herds found their paths along

their cow trails blocked here and there by these fenced-in homesteads,

and trouble began to brew between these two categories of Westerners,

the farmer and the cattleman. For years the cattlemen had been allowed

freely to graze their herds on the vast federal lands of the Great

Plains (reaching from Texas to the Dakotas). But now homesteaders were

rapidly filling these open lands. Little by little the cattle herding

business was pushed ever more westward, increasing the difficulty and

costs of the herding itself.

Furthermore, the herds had expanded to such a

size that the price of beef began to drop – at a time in which the

cattle lands and trails were beginning to be overgrazed by this vast

number of cattle. When a very bad winter hit in 1886–1887, hundreds of

thousands of cattle died from exposure and the lack of sufficient grass

or even grain for feed. A number of cattle barons never truly recovered from this bitter blow.

|

The Rapid growth of the American West

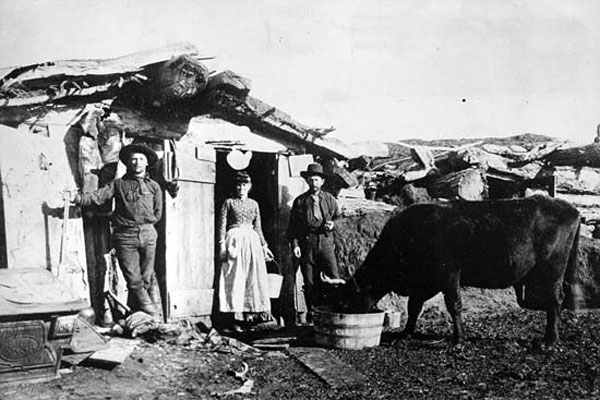

The rise of the American farmer.

Anyway, the business of farming was slowly taking over from the

business of cattle herding. And truly a business it was. The families

who came West and acquired their 160-acre tract of land found that 160

acres in the West did not provide the financial security that 160-acres

in the East once had. At best these small homesteads could feed their

large families. But beyond that, there was little additional income

from their fields that could allow them to purchase the extras needed

for the good life. For instance, the Great Plains was devoid of

woodlands and thus wood had to be purchased rather than simply cut from

the surrounding woods as was the case back East. Sadly for many

homesteaders, their sole building material was the sod they cut from

the ground and turned into something like bricks to frame their houses

and barns. The sod houses that dotted the landscape of the Great Plains

were hardly a lasting solution to the challenge of settling the West.

In short order, numerous homesteaders (perhaps as many as

three-quarters of them) had to simply abandon the effort and move on to

try their luck elsewhere.

But this opened the opportunity for the

more entrepreneurial-minded homesteader to pick up abandoned

neighboring land, adding to his holdings until he possessed many

hundreds of – even a thousand – acres of farmland.

This was nicely timed with the invention

of farming machinery that made the plowing, cultivation and harvesting

of vast fields an attainable goal for an industrial farmer. And indeed,

America began to see such industrial farms grow in number during the

latter part of the 1800s. In America, farming had finally become very

big business, the Western farms fully able to feed the Eastern cities

which were also growing rapidly in size.

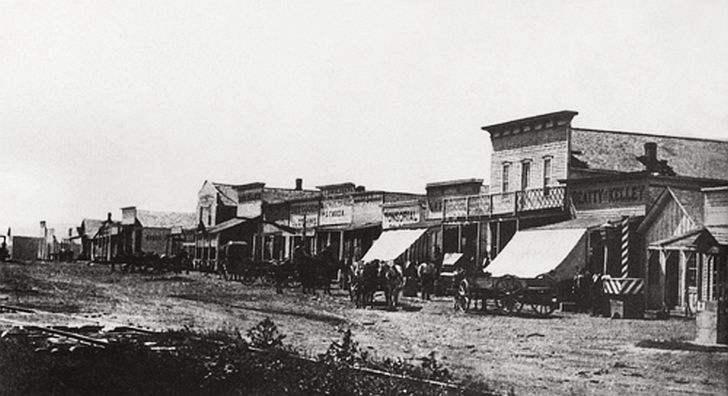

Urbanization comes to the West.

Towns located along the growing number of rail lines crisscrossing the

American Great Plains or Midwest began quickly to develop as economic

and social centers for the agricultural industry of entire counties.

Thus as the farming business boomed, churches, schools, banks, and

general stores began to appear in these towns, bringing American

civilization to the Midwest. In many ways this too, along with the

cowboy, was fast becoming a major cultural symbol representing the

young and fast-growing America.

Meanwhile... the American South.

Sadly the South had slipped out of the picture, caught up locally in

trying to heal the economic and cultural wounds left by the Civil War.

It would take many generations before the South was finally able indeed

to rise again.

|

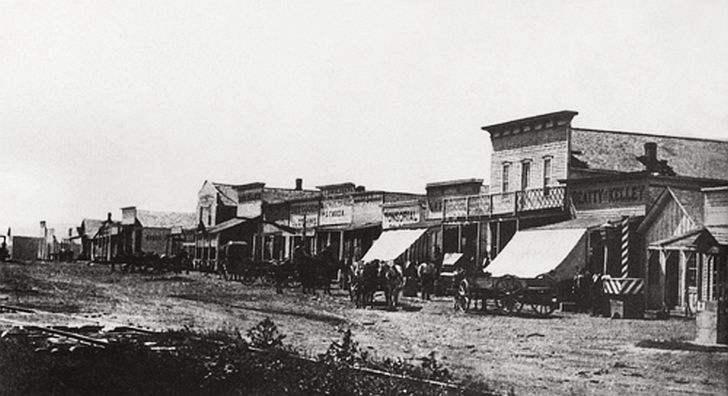

Dodge City, Kansas 1876

A saloon (with attentive ladies) in Cripple Creek, Colorado.

And a brothel in Montana to entertain the boys

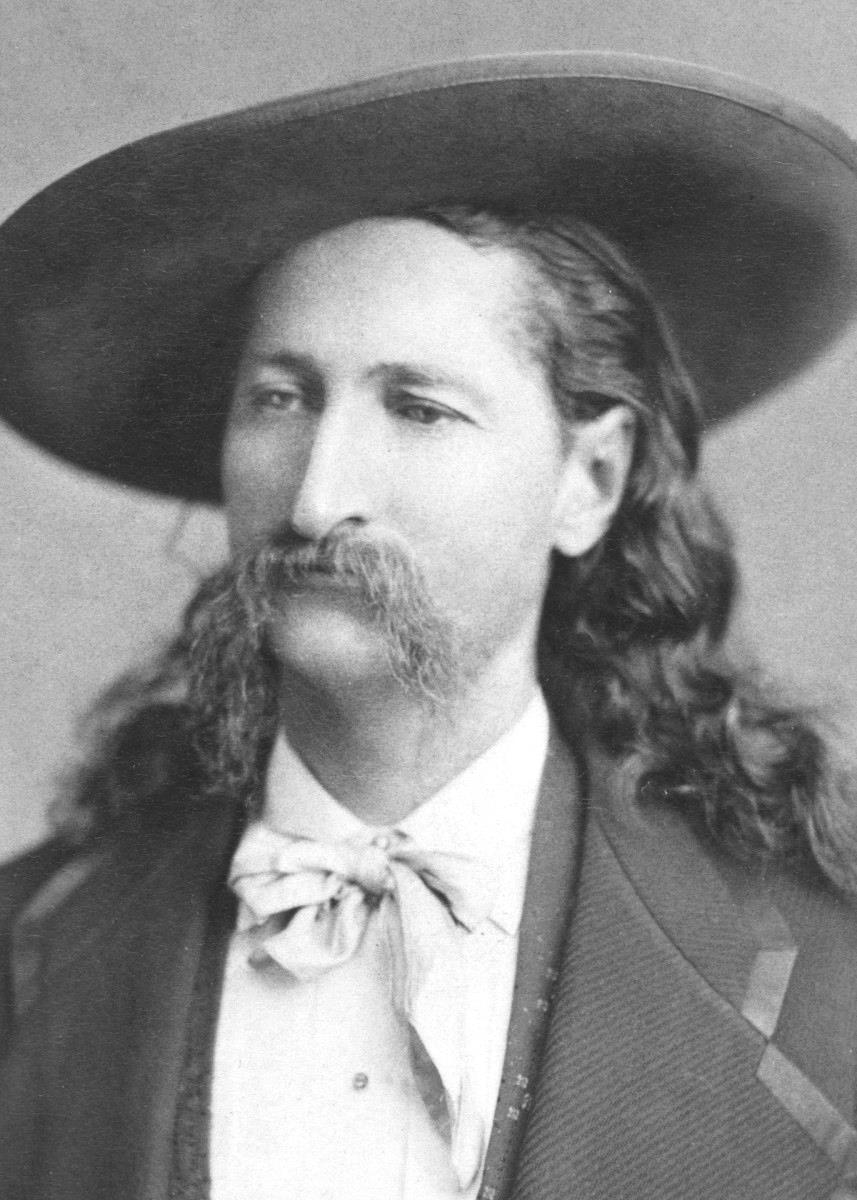

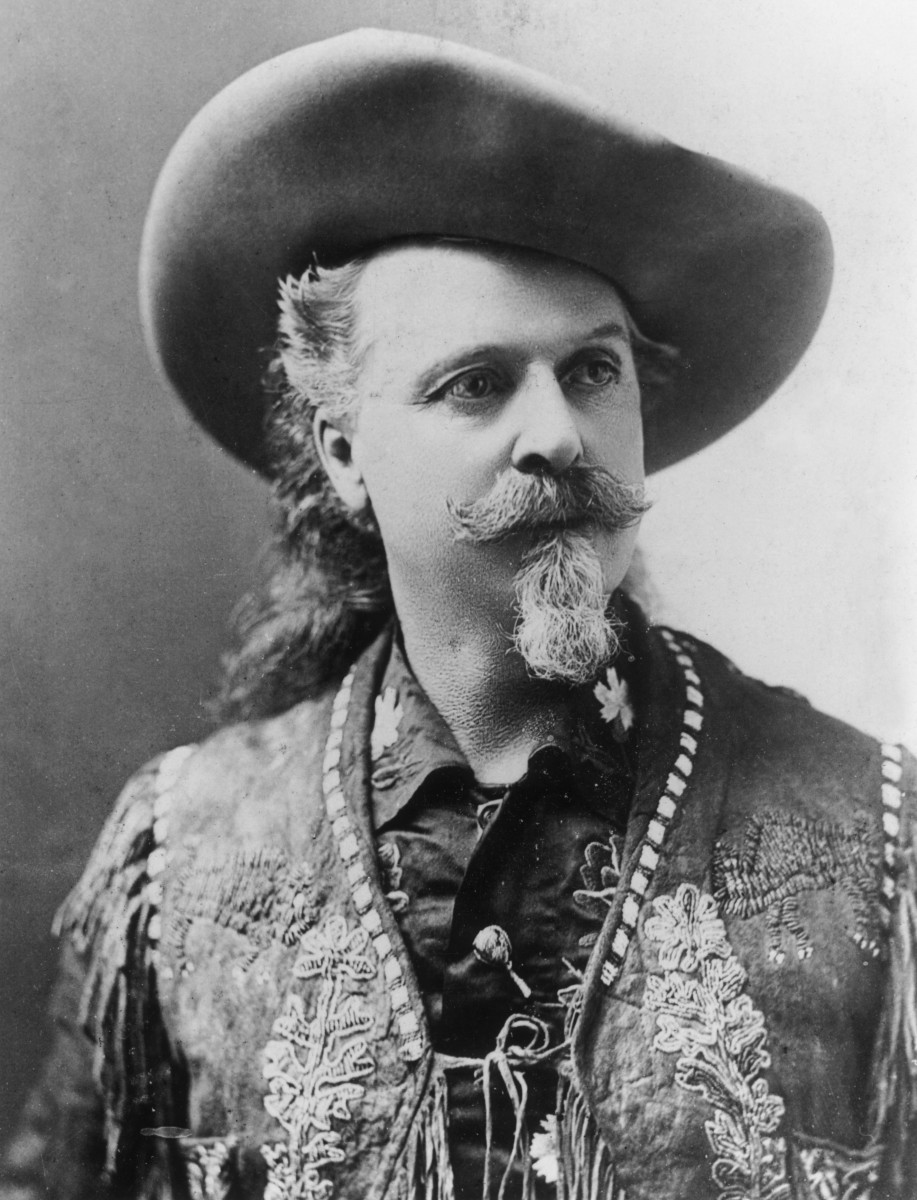

And lawmen to keep some semblance of order in the midst of the rowdy crowd

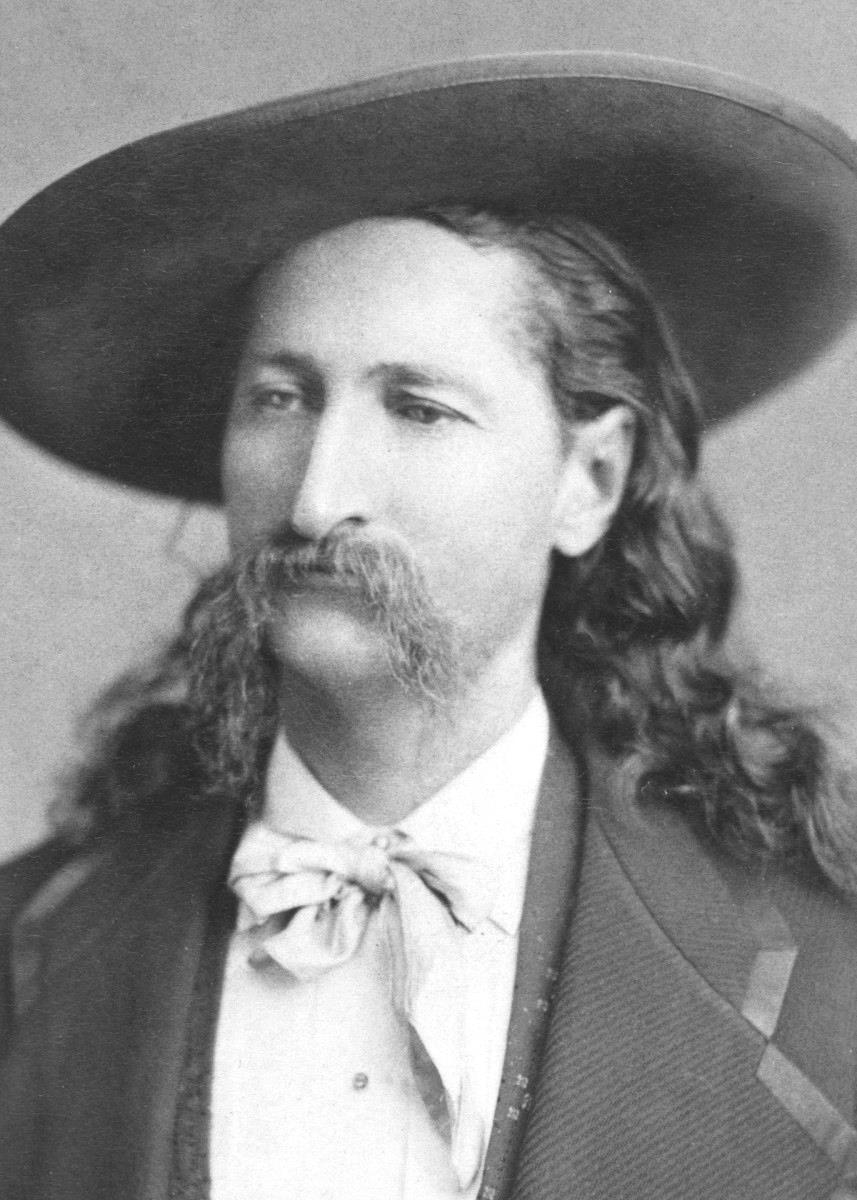

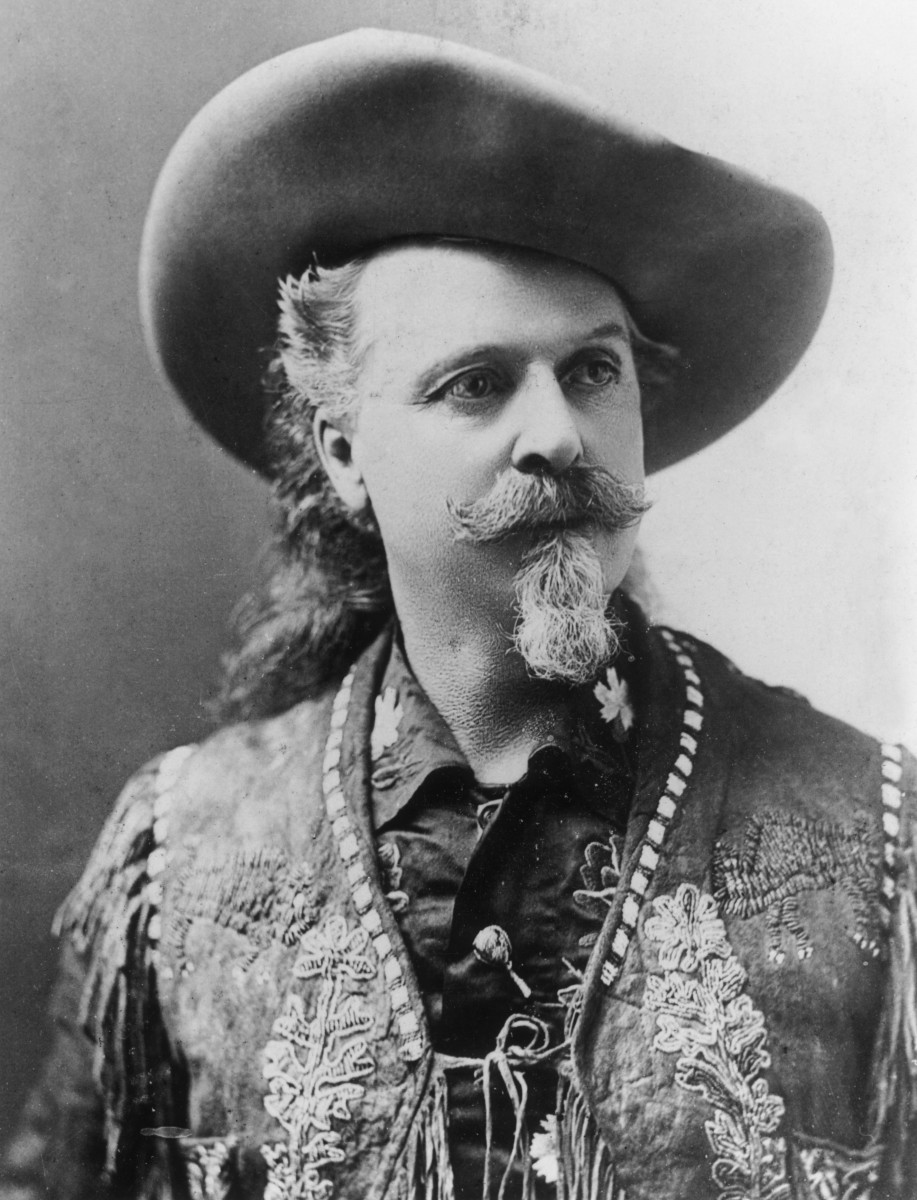

And there were the celebrities to add a sense of adventure And lawmen to keep some semblance of order in the midst of the rowdy crowd

And there were the celebrities to add a sense of adventure

to those watching frontier life from afar

James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok

William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody

Annie Oakley

THE

INDIANS' "LAST STAND" |

|

At the end of the Civil War whatever Indian

communities still remained East of the Mississippi were quite small and

isolated, hardly registering at all in the social-political scheme of

things. However, in the American Southwest, widely scattered

communities of Navajo and Hopi maintained something of an undisturbed,

though marginal, agricultural existence (their land was arid, even much

of it desert.) Neighboring Apache meanwhile led a nomadic lifestyle

hunting game from horseback. In the American Northwest a number of

tribes led fairly comfortable and quiet agricultural lives, along the

lines that the Eastern Indians had once led, prior to the arrival of

the Europeans.

The most active, and violent,

Indian-European dynamic was on the Great Plains, where Indians

constantly struggled against White Americans for control of the land.

The Plains Indians had once been farmers. But with the rapid growth of

the herds of Spanish horses that had escaped to the wild – horses that

the Indians learned how to tame – the Indians had developed great skill

as horsemen and left the farming world for the world of the hunter,

becoming dedicated hunters of the vast bison herds which covered the

Great Plains. They had so completely adapted to the lifestyle of

bison-hunter that without these herds to hunt they would not know how

to survive. And therein lay one of the biggest problems for them.

The other problem of course was like the

one also faced by the American cowboy: the American homesteaders who

were moving onto the Great Plains to establish fenced-in farmlands for

themselves and their families. By the last quarter of the 1800s it was

increasingly apparent to the Plains Indians that the two societies

could not coexist. For the Indians, survival meant simply chasing the

American homesteader off the land. Thus Indian-American war loomed.

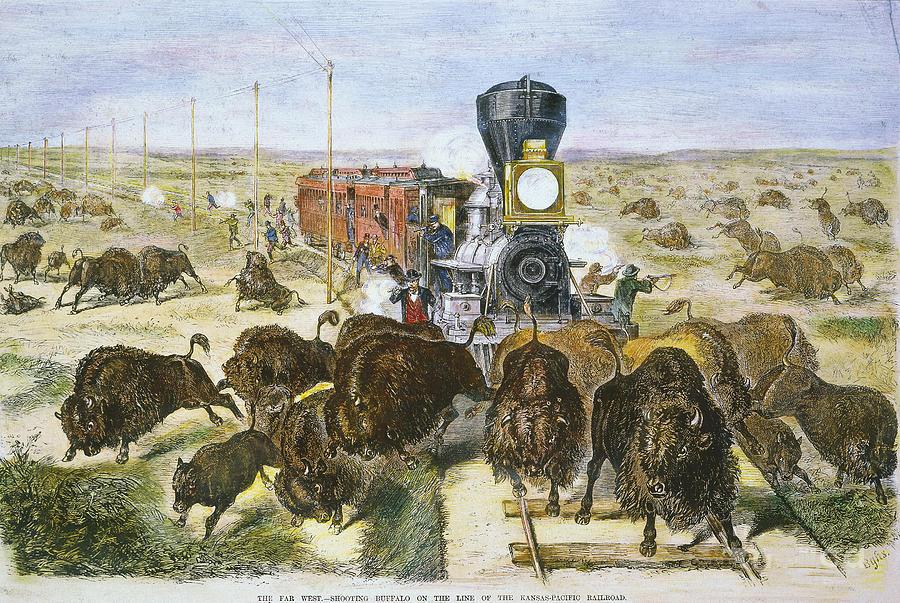

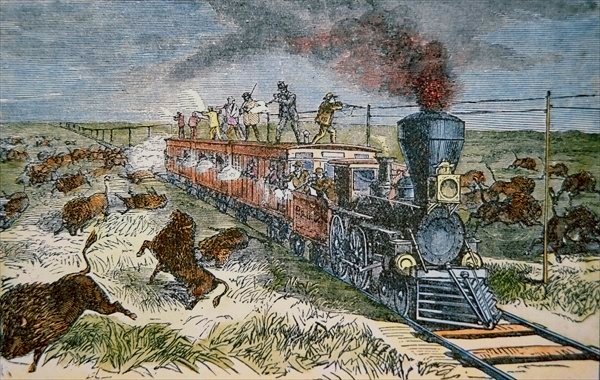

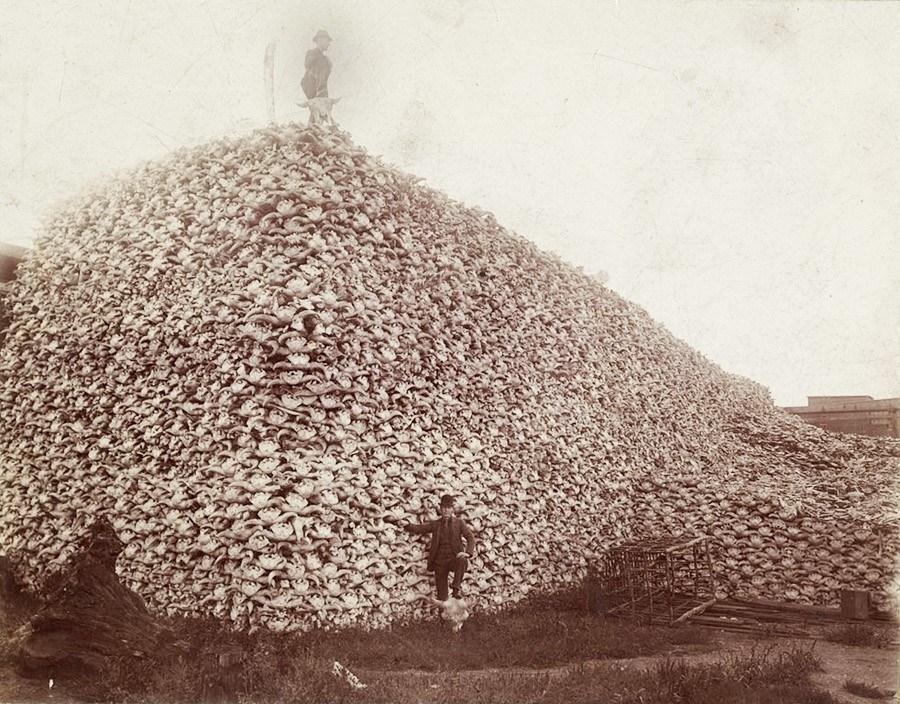

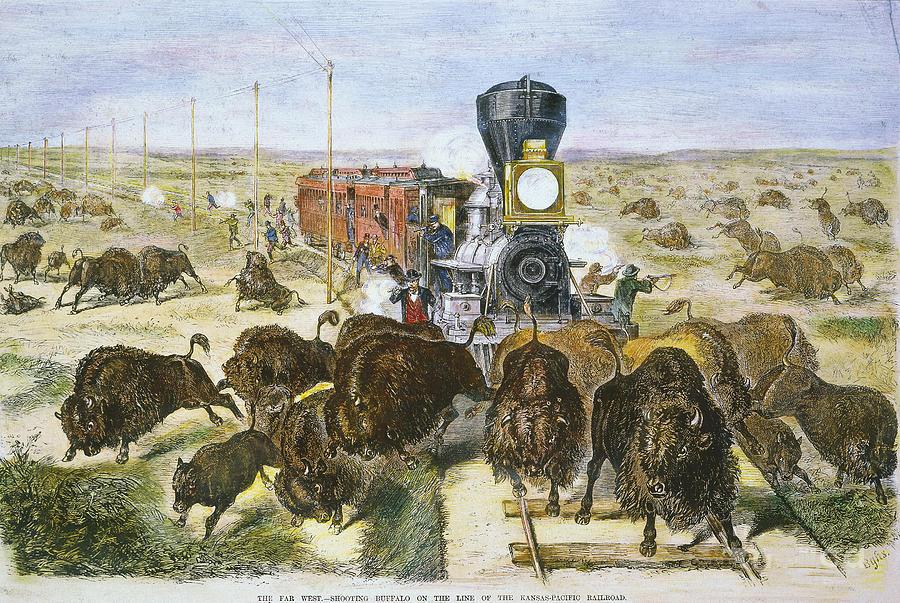

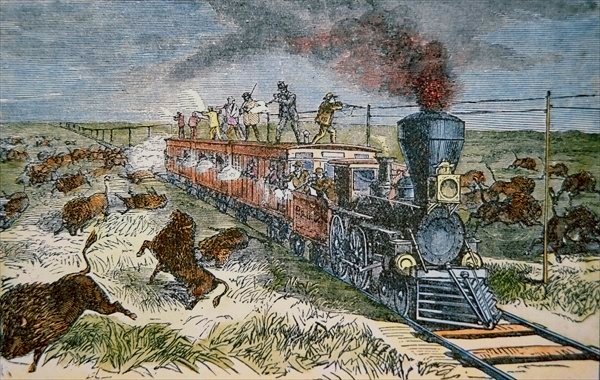

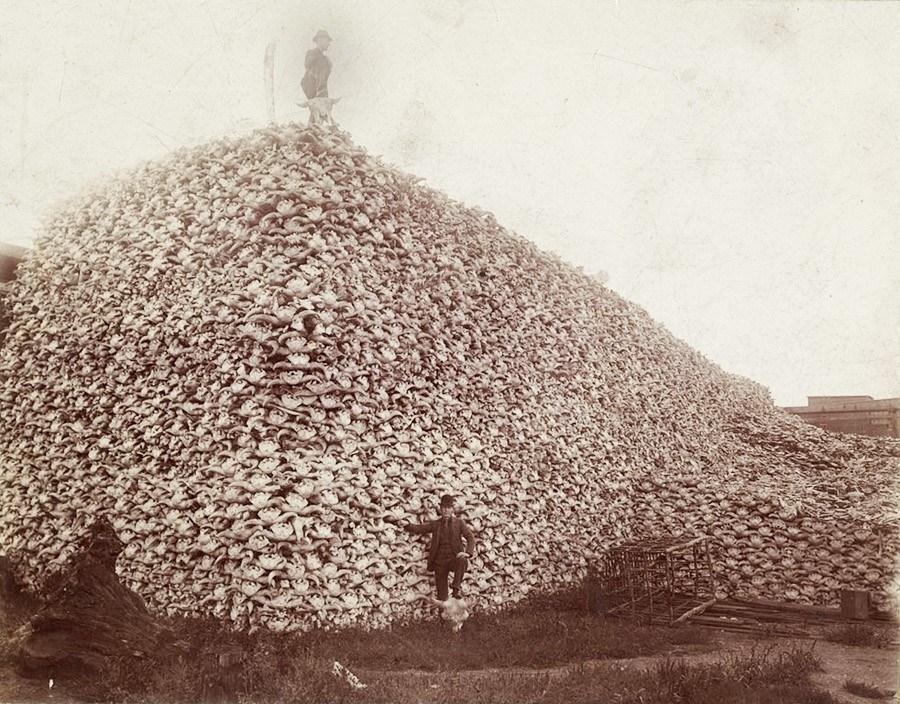

The decline of the buffalo herds

Concerning the bison or buffalo herds and

their rapid decline, there is still much controversy as to the cause.

But certainly the effect was clear enough: deprived of their buffalo,

the Plains Indians could not survive as a society. Explorers to the

West prior to the Civil War were astounded by the size of the buffalo

herds, hundreds of thousands of them in a single herd. But already by

the time of the Civil War the herds were beginning to thin out. The

Plains Indians themselves were well-known for their extravagance in the

killing of the herds, given their own marksmanship with the hunting

rifle and skill on horseback. The herds also lacked protective

instincts and so they were easily slaughtered in vast numbers.

The Whites of course also participated in

the slaughter, hunting them for their hides, sometimes just hunting

them (for instance from passing trains) for sport – or ultimately to

deprive the Plains Indians of their sustenance. By the 1880s the total

number of buffalo had dropped to only mere hundreds, to the point of

near specie-extinction.

|

The debate over what to do about "the Indian Problem"

While events on the frontier itself seemed to

take their own course as frontiersmen saw the necessity, back East a

huge debate raged over what the proper policy toward the Indian should

be.

Humanism was a response natural to those back

East who were comfortably removed from the terror of frontier life. In

a Rousseauian fashion,3 Humanists took the rather romantic view of the

Indian as the pre-civilized natural man, possessing all the pure or

sinless qualities of man that he possessed before Adam and Eve's Fall

into sin (or before the corruptions of civilization had produced their

disastrous effect). Humanists thus believed that the Indians should be

simply left alone, that White intrusion into the West should be slowed

up or even halted completely. But that romantic dream was also simply

not going to happen. Thus the Humanist program was largely irrelevant

to the solution of the Indian Problem.

Others, notably evangelical Christians, felt

strongly that God wanted Christian Americans to help the Indians come

out of their primitive (and pagan) ways, to personally bring them the

good news of the higher life to which God called all his American

children (including the American Indians). Thus missionaries took

themselves to the tribal lands of the Indians to bring them to

Christian ways and to the life-style of Anglo-Americans – setting up

schools and churches to show the Indians the way to proper or civilized

life.

But as the Cherokee and other Southeastern

Indians themselves had discovered earlier in the 1800s, converting to

the settled, agricultural, Christian life-style of the White

frontiersman did not guarantee any kind of larger protection when these

White frontiersmen sought their land. Thus ultimately this was not a

terribly good solution to the Indian Problem, at least not from the

Indian point of view.

Ultimately the decision came in the form of the

policy of rounding up the nomadic Plains Indians tribes and placing

them all on Indian reservations, promising that within those

reservations they could live as they chose – but that they were not

ever to leave those reservations or they would face the wrath of the

U.S. military sent to enforce the reservation policy of Washington's

Bureau of Indian Affairs.

As Commander of the U.S. military enforcing

that policy, Civil War veteran cavalry leader General Philip Sheridan

proved to be a strict enforcer. The only problem here was that the

Indians themselves knew from previous treaties undertaken with the U.S.

government that these reservations were generally only temporary

promises of respect for Indian rights, before such reserved territory

was once again taken away from them by land-hungry Whites.

Ultimately, the Indians understood that they

were going to have to have their own say in shaping policy, which meant

only one thing: they were going to have to fight – and fight savagely –

to protect themselves from extinction as a unique society or people.

Meanwhile, wars between the Indians on the one hand

and White settlers and U.S. Army units on the other had been fairly

constant on the American Plains since the days of the Civil War, with

the Indians typically receiving the worst end of these encounters. But

by the mid–1870s the Indians were putting aside their ancient tribal

differences and beginning to work in concert with each other.

Thus in 1875, Sioux (or Lakota) Chief Sitting

Bull and his tactician Crazy Horse decided it was time to leave the

Dakota Reservation to take to the offensive against settlers invading

the Dakota Black Hills, sacred Sioux land. By the summer of the next

year (1876) Sitting Bull had linked up with a large number of Northern

Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors in Southern Montana. Sent to deal with

this huge gathering of thousands of Indians was Sheridan's cavalry.

Sheridan divided his cavalry into separate units, to converge on the

huge Indian gathering from three different directions and force these

Indians back onto their reservations.

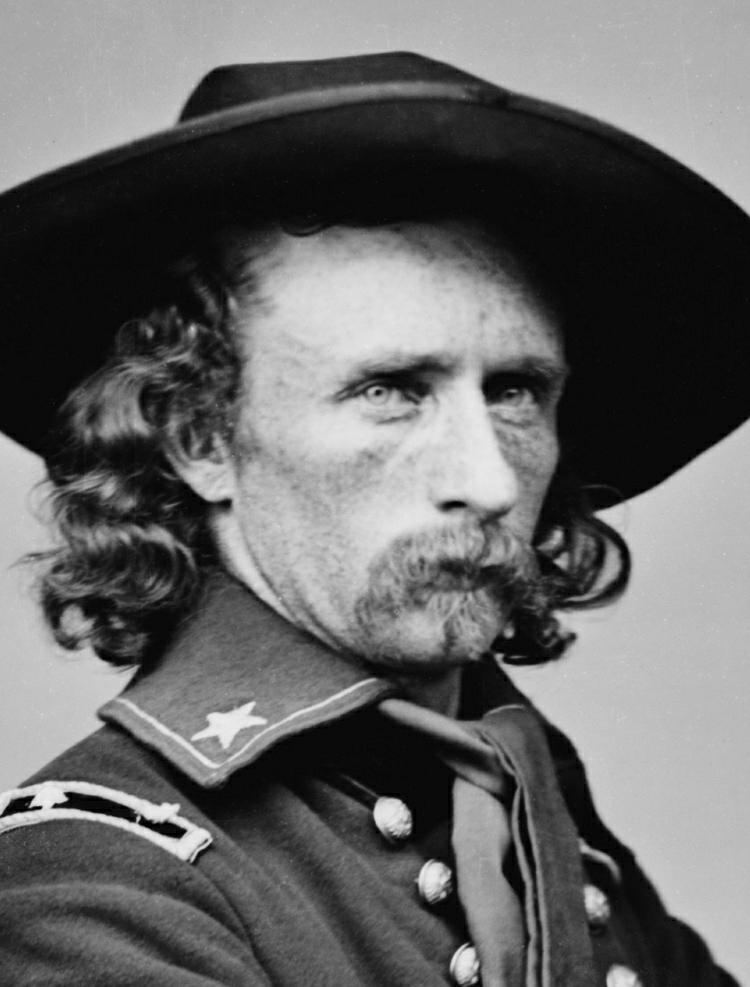

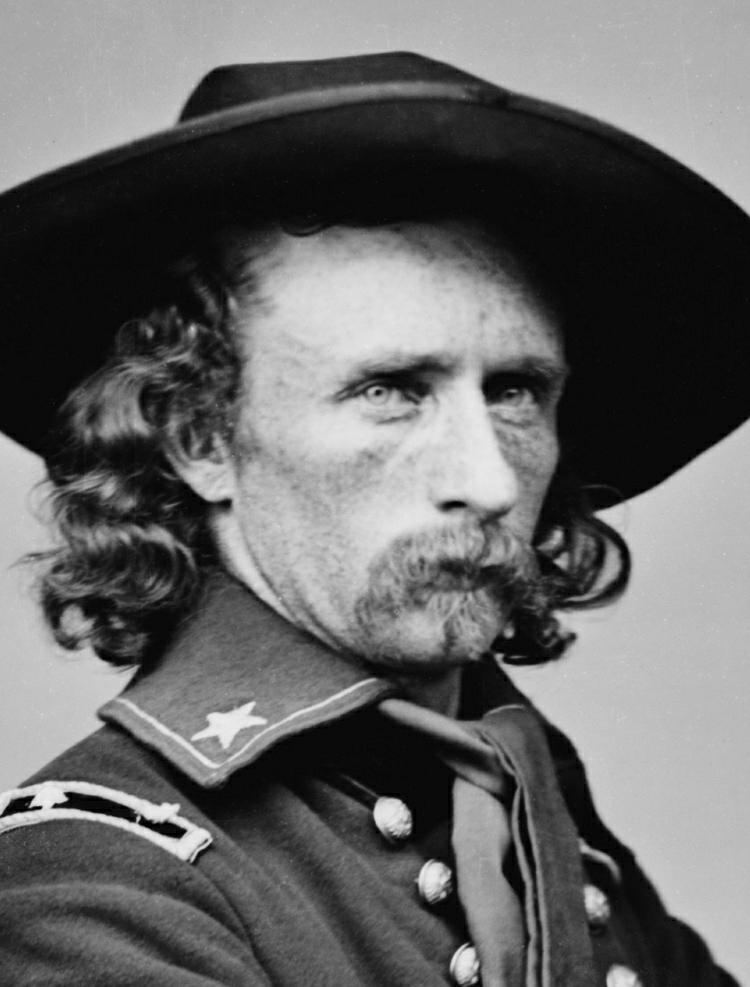

Things did not go well for Sheridan, as the

Indians took on one of these detachments and forced them into

humiliating retreat. Trying again, Sheridan sent out 700 troops under

the colorful Civil War celebrity, George Custer, Custer dividing his

force into a number of units, he himself leading a large detachment of

those men. On June 25-26 at the Little Bighorn River he and his

soldiers were also to discover the fighting prowess of the Indians,

when his entire detachment, including Custer himself, was either killed

(268 men) or severely wounded (55 men, 6 later dying from their wounds)

in an encounter with Crazy Horse and his warriors.

But this massacre did not break the will of the

U.S. military. Ironically it had the opposite effect, turning Custer

into some kind of iconic martyred hero, and merely deepening the

determination of the military to crush definitively all Indian power.

Realizing that his actions had simply awakened an angry and massive

White nation, Sitting Bull reappraised the situation and decided simply

to take himself and his people back to their Dakota reservation. And

this would be the last of the great Indian efforts to hold off by force

the advancing White Americans.

3Jean-Jacques

Rousseau was a French-speaking Swiss philosopher of the mid–1700s who

in his widely-read book, Social Contract, idealized the "natural man" –

even citing the American Indian as a perfect example – claiming that

sin and corruption was not itself natural to man, but came upon the

social scene only with the rise of civilization. Of course he had the

very obvious corruptions of the European royal courts in mind as he

wrote, and from a commoner's point of view such highly "civilized"

courts (as kings and their attendants saw themselves) were indeed very

corrupt, with their perfumed wigs, expensive entertainment, and general

uselessness as overseers of the lives of the multitudes of Europeans

not part of the privileged class.

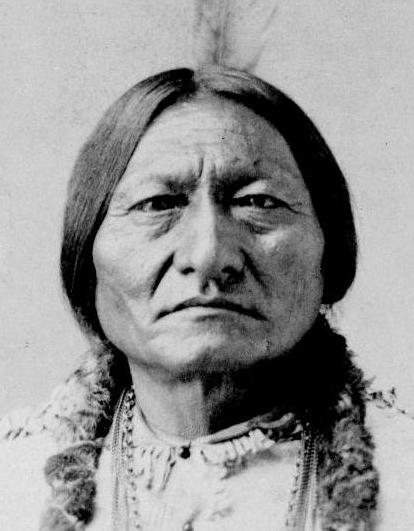

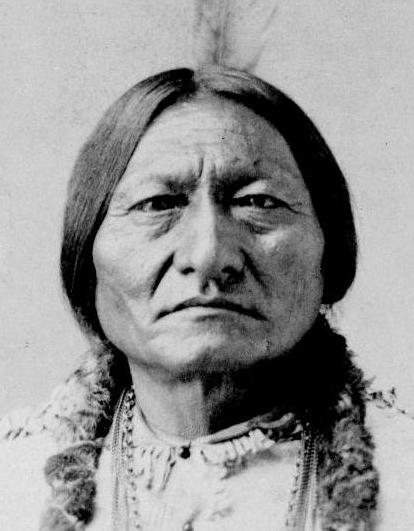

Colonel George Custer

Chief Sitting Bull

|

Indians assigned to Reservations

under the Dawes Severalty Act (1887).

Indians assigned to Reservations under the Dawes

Severalty Act (1887). Finally in 1887, Washington came to some kind of

conclusion about the Indian Problem when it passed the Dawes Severalty

Act. It attempted to turn the Indian reservations into homesteading

territories, each Indian family assigned the proverbial 160 acres, all

Indians to receive English instruction, and eventually all becoming

U.S. citizens. That these proud nomads however were not naturally

farmers was clearly demonstrated in the crushing of the Indian social

morale, and the widespread alcoholism that quickly descended upon the

reservations. But at least from White America's point of view, the

Indian Problem had been solved.

In keeping with the moral climate of the

times, it was not long until the Bureau of Indian Affairs fell right

alongside the railroad business into deep corruption. Government money,

unaccountable to market forces but distributed solely through political

considerations, invited all sorts of patronage appointments, at a cost

(kickbacks) of course. But it was not long before a vigilant news media

caught wind of the corruption, and scandals erupted into the public

view, dirtying the reputations of a number of American politicians.

The Ghost Dance, Sitting Bull, and Wounded Knee (1890).

But White Americans were not the only ones

to take note of the corruption, which merely added to the Indians'

sense of demoralization. Nothing that they could do seemed to improve

the Indians' sense of social significance. They were an entirely

defeated people. Thus it was that in 1890 the Sioux got caught up in

the Ghost Dance craze, believing that the performance of this ritual

would finally clear the land of the White man, even with the wearing of

special shirts to make the Indians invulnerable to White man's bullets

if it should come to armed conflict. And it soon came to such conflict

– in which Sitting Bull was killed along with a dozen of his warriors.

Then the 7th Cavalry was sent in to impose order and at Wounded Knee

even greater fighting broke out, in which 200 Sioux men, women and

children were killed – along with 25 U.S. soldiers killed and 39

wounded. It would be the last sad (and probably accidental) such

episode in the long-standing feud between the American Indian and the

American White.

Indeed, the Indian Problem had now been solved definitively.

|

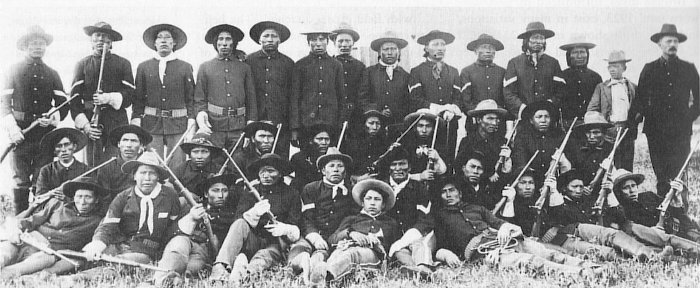

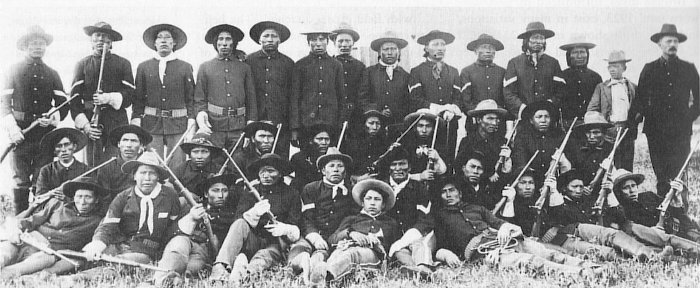

Indian Scouts serving the U.S.

Cavalry

Indian bodies gathered for mass burial after the

battle at Wounded Knee Creek – 1890

Go on to the next section: Capitalism in the "Gilded Age"

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

The American-Indian Wars during the

The American-Indian Wars during the Kit Carson and the Navajo, Kiowa, and Comanches

Kit Carson and the Navajo, Kiowa, and Comanches