11. CAPITALISM ... AND INDUSTRIAL GROWTH

CAPITALISM IN THE "GILDED AGE"

CONTENTS

Capitalism in the "Gilded Age" Capitalism in the "Gilded Age"

The "Captains of Industry" (or "Robber The "Captains of Industry" (or "Robber

Barons" as others termed them!)

The extravagance of this wealthy elite The extravagance of this wealthy elite

The American "Middle Class" is doing The American "Middle Class" is doing

pretty well for itself as well

Americans can afford even the luxury of Americans can afford even the luxury of

idealizing the American

woman

Of course not all was

perfect in the Of course not all was

perfect in the

picture of American "Middle Class" life

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 340-347.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1890s |

America's entry into the "Gilded Age" (for some Americans anyway)

1890 At this point, some mere 1 percent of the American population at the top of the social ladder earns over 50 percent of the nation's wealth ... with – at the other end of the social ladder – 44 percent of the population together earning only 1 percent of the nation's wealth

The Sherman Antitrust Act comes into force (Jul) ... originally designed to break up trade unions ...

but ultimately used to go after industrial monopolies

Also,

Sherman's Silver Purchase Act goes into effect (Jul) in support of the

"silverites"

In

Congressional elections, Republicans lose more Congressional seats (Nov)

1892 Harrison loses his reelection to Cleveland (Nov) ... and his wife to tuberculosis two weeks before the election

1893 Another economic panic hits America ... which Cleveland worsens by having Congress repeal Sherman's

Silver Act; industrial unemployment expands greatly as companies shut

down

1894 The economic situation worsens further with widening worker unrest ... stirred by Socialist Debs; hard hit is the railroad industry, with 125 thousand workers on strike – Cleveland sending troops to break the strike at the Pullman (luxury railroad car) plant

Cleveland's Democrats suffer a huge setback in the 1894 Congressional

elections (Nov)

1895 Cleveland finally accepts Morgan and Rothchild's offer to sell 3.5 million ounces of gold to the US Treasury (in exchange

for 30-year bonds) ... saving the dollar from collapse

1896 Edison invents the movie projector

The strongly silverite Bryan defeats

pro-gold Cleveland as Democratic Party candidate ... but loses

the national election to Republican McKinley ... McKinley's

campaign skillfully directed by Hanna

|

| 1900s | American politics, economics and culture as the country enters the 20th century

1900 McKinley is renominated as Republican candidate for US president, with Roosevelt as his vice-presidential

candidate; Mckinley wins the election a second time against Bryan

1901 But McKinley is only six months into his second term when he is shot and killed; Roosevelt is thus now US president

Carnegie sells

his steel business to J.P. Morgan for $480 million; he gives most of

his earnings away to various charities and social endeavors

1903 Ford sets up the Ford Motor Company in Detroit

The Wright

brothers test their first engine-powered, human-piloted plane (Dec)

1904 The Olds Motor Vehicle Company of Michigan is the leading US car manufacturer at this point

Roosevelt easily

wins reelection as US president (Nov) ... but promises not to run again

1905 The Wright brothers fly a plane 24 miles in 39 minutes!

1906 A huge earthquake hits San Francisco hard (Apr)

A strong

pentecostal Christian revival breaks out on Azusa Street in Los Angeles

(also Apr) – and continues in one form

or another until around 1915 ... ultimately inspiring the creation of

the Assemblies of God – and other forms of pentecostalism to follow ... all the way up to today

1907 Morgan forms a group of investors to put money back into a failed Wall Street ... saving the American economy from

collapse; he also buys a failing industrial conglomerate; Roosevelt does not press the matter

of potential monopolitistic practices ... for the action is well needed

He does however

act strongly in supporting the Tillman Act ... preventing corporate

contributions to federal political campaigns – so as not to let the big-money boys control the democratic process (that law would be set aside by the Supreme Court with rulings in 2010

and 2014 ... in effect making it "unconstitutional" to set boundaries on campaign contributions!)

1908 Ford introduces the Model T Ford at $825 ... comparatively very inexpensive (with prices dropping every year as production expands rapidly)

The Wright

brothers fly their newest model before the disbelieving but now

astonished French ... and the US military (Sep)

Roosevelt ends

his presidency by sending a fleet of 16 white-colored battleships on a

cruise around the world ... to announce America's arrival as a great power

Roosevelt's

friend Taft easily wins the Republican Party presidential nomination

... and the presidential election itself (Bryan again the Democratic Party candidate)

|

| 1910s | America ... just prior to the outbreak of "The Great War" (World War One)

1912 The Republican Party presidential convention splits in a confrontation between Roosevelt and Taft ... supporting Taft – and sending Roosevelt off to start his own Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party

With the

Republicans split, the Democratic Party candidate Wilson wins the

presidential election

1913 The 16th Amendment is ratified (Feb), allowing Congress to collect an income tax directly from the American citizenry

The 17th

Amendment is ratified (Apr) "democratizing" the US Senate ... making

the election of US senators no longer the

responsibility of the states (their governors or legislatures) but now a matter of direct election by the American voter

The Federal

Reserve is founded to intervene with funding when the American economy

seems in danger of collasping

Rockefeller

establishes his Foundation with $250 million in startup funds for

medical research

Ford institutes his new moving assembly line ... making the Model T even cheaper – affordable by even his own assembly workers

1914 At this point American industry is responsible for one-third of the world's total industrial production ... more than

Britain, France and Germany combined ... though these European nations

still see America as a rather backward society

|

CAPITALISM IN THE "GILDED AGE" |

|

During the time of post-Civil-War recovery, a new

social dynamic had been rising within the fast-growing American cities:

the adoration of modern technology and those who provided it, the

promise of wealth flowing out of this dynamic, and the seeming control

over life provided by the scientific mentality that undergirded this

whole social-cultural revolution. This was due in no small part to the

Civil War and its lasting effect on the American economy. The war's

demand for steel, and the iron ore and coal to make it, and the

railroads and boats to ship it, and the financial institutions to fund

its initial outlay, and the laborers to work the whole system – all

this had made a deep impact on what was formerly almost purely an

agrarian society.

Apart from the early railroad ventures

during and immediately after the war, the government played in the

post-war period only a minimal role in the on-going development of this

new industrial society, especially as the war and its needs receded

from view and the system seemed to run simply under its own dynamics

rather than on the basis of popular social-political demands.

Nor was God invited to play a role in the

development of this new society. America's Grand Destiny now seemed to

be driven forward largely by the huge material rewards that fell to the

particularly ambitious and fearless. Fortunes could be made rather

quickly by very enterprising individuals (and they could be lost almost

as quickly). And these fortunes were awesome, often exceeding

(sometimes vastly) the levels of wealth of the European nobility.

Indeed, it was a Gilded Age (Age of Gold) for successful American

industrialists.

This was a perfect setting for the spirit

of Darwinism to soar. Certainly the basic theme of this rising social

order was quite Darwinian: progress through survival of the fittest. To

the strong belonged the spoils of their conquests. But for those who

fell to the wayside in this struggle for survival there would be no

tears wept. But the risk of this competitive struggle seemed worth it,

at least to those who anticipated striking it rich in this new game of

potentially limitless opportunity (if you were willing to play it hard

and fast).

For others, however, this game offered

virtually no opportunity – only drudgery and painful hardship on this

path of survival. With the closing of the Western frontier and loss of

the ability to secure cheap Indian land, farm boys were forced to find

work in these industrial enterprises, not with the hope of striking it

rich, for there was almost no entry point for them into a game that

required substantial startup money or capital to get up and running in

this new capitalist system. These farm boys came penniless, offering

only their labor. But for their labor they received very little in

return. In the eyes of the Darwinists these new industrial workers were

not seen as people, as fellow Americans to whom they owed some sense of

mutual responsibility. Instead they were viewed by the rising class of

wealthy capitalists only as economic costs, costs which they had to

keep low in order to gain the profits that would win them victory in

this Darwinian game. What was happening to America? Had it

gone from African slavery only to replace it with a shockingly similar

wage-slavery? Was this the social outcome that so many young men had

given their lives for in the recent Civil War?a name="Captains-of-Industry"> |

THE "CAPTAINS OF INDUSTRY" (OR "ROBBER BARONS" AS OTHERS TERMED THEM!) |

|

The rapidly widening gap between hard-working

American laborers and the Captains of Industry was vast … and shocking.

According to a survey done in 1896,1

of a total of 12½ million American families in 1890, 125,000 very

wealthy families, or 1 percent of the total number of families in

America, earned over 50 percent of America's total family wealth. The

well-to-do, comprising about 11 percent of the total number of

families, earned about 35 percent of the nation's family wealth, the

middle classes, comprising about 44 percent of the total, earned about

12½ of the total wealth, and the poorer classes, comprising another 44

percent of the families, earned only about 1 percent of the total

wealth.

And among this very wealthy 1 percent of

the population, an even smaller number of families stood out way above

the rest. A few are mentioned here just to point out how capitalism was

working in the latter part of the 1800s.

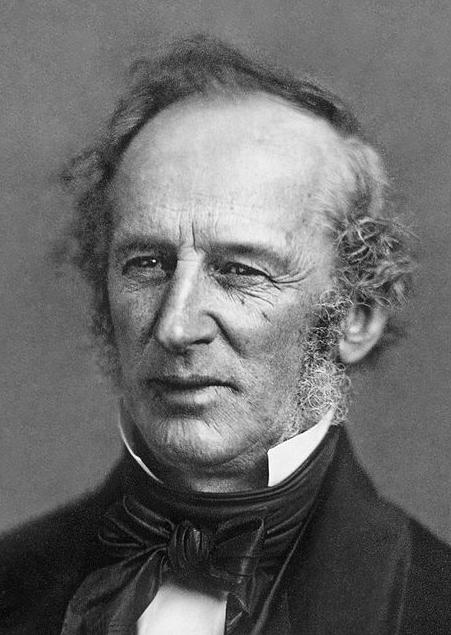

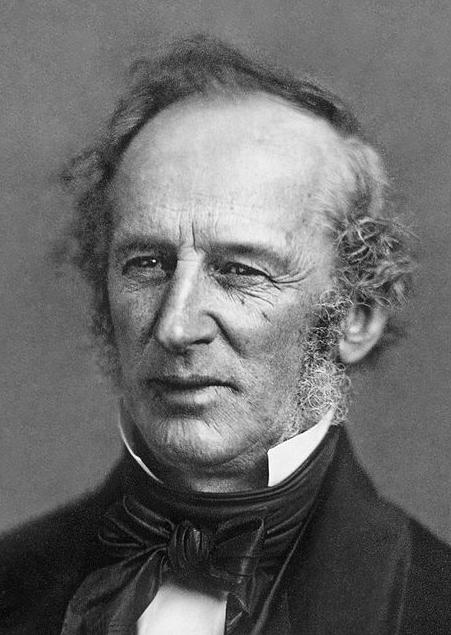

Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt

was nicknamed "Commodore" because he got his climb out of poverty as a

boat operator back in the 1810s, ferrying New York passengers between

Staten Island and Manhattan. It was a very competitive business, but

Cornelius Vanderbilt knew how to compete. He fought against the

well-defended steamboat monopolies that had secured privileged routes

around New York, buying out companies, although at times he even had

some of his own operations bought out by others. Vanderbilt

was nicknamed "Commodore" because he got his climb out of poverty as a

boat operator back in the 1810s, ferrying New York passengers between

Staten Island and Manhattan. It was a very competitive business, but

Cornelius Vanderbilt knew how to compete. He fought against the

well-defended steamboat monopolies that had secured privileged routes

around New York, buying out companies, although at times he even had

some of his own operations bought out by others.

But

by the end of the 1830s, Vanderbilt had secured a number of his own

steamboat monopolies, and in the early 1840s he began to manage small

railroads that connected with his steamboat lines. In 1847 he took over

a major railroad running from New York to Boston, and bought out a

number of competitors, putting his railroad line in a dominant position

on that vital route. Then with the beginning of the California gold

rush in 1849 he switched to shipping on the high seas, even at one time

attempting to put together a group to build a canal across Nicaragua

between the Atlantic and Pacific. He failed at this attempt, but did

set up a land and water connection between the two oceans, and then

developed a Pacific steam line to California.

In

the 1850s he bought a large company that manufactured the steam engines

for the steamboat industry, and also jumped into the trans-Atlantic

steamship business. Even at one point he found himself deeply involved

in Central America against a major competitor – and various authorities

supporting that competitor ... including some military action. So

Vanderbilt moved his operations further south to Panama and then

acquired a monopoly on a steamship line running from there to

California.

During the Civil War he donated and staffed at his own expense his flagship, the Vanderbilt, which was used to hunt Confederate raiders (such as Confederate Admiral Semmes and his warship, Alabama).

After

the war he was joined by his son Billy in acquiring a number of New

York railroads, and brought them together as the future New York

Central Line, one of the first corporate giants in America. He also

constructed a large railroad terminal in Manhattan on 42nd Street, also

the forerunner of New York's Grand Central Terminal, the world's

largest train station.

The

only time Vanderbilt found his move blocked was in his attempt to buy

up the Erie Railroad, which Jay Gould and his associate James Fisk

fought off by watering down stock (quite in violation of the law, which

Fisk avoided by bribing New York legislators!), to weaken Vanderbilt's

position after Vanderbilt had bought up, at some considerable expense,

what he thought

would be a controlling share of the business. This massive issue of new

stocks by Gould and Fisk devalued Vanderbilt's stocks so badly that his

losses were enormous. This created a deep and lasting enmity between

Vanderbilt and these two equally ambitious and notoriously clever

financial wizards. But Vanderbilt would not again be on the losing side

of this rivalry, a rivalry that lasted all the way up to his death in

1877.

At his death he was worth the monumental sum of $100 million,2

most of which went to his son Billy (although he was very generous to

his other many sons and daughters). He also donated the $1 million that

founded the university in Nashville, Tennessee, that still carries his

name, which at the time was the largest charity contribution ever

offered by a single donor. He also gave rather generously to churches,

including the 8½ acres which he gave to the Moravian Church on Staten

Island for a cemetery, where he himself is buried.

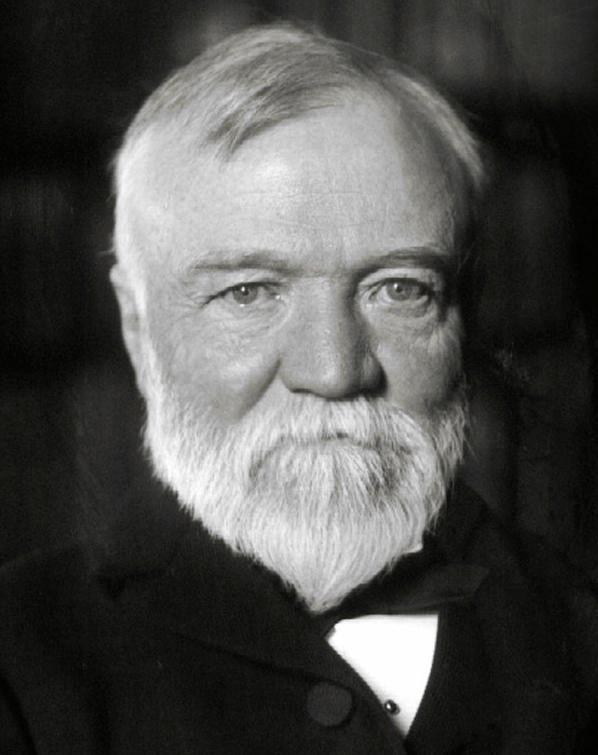

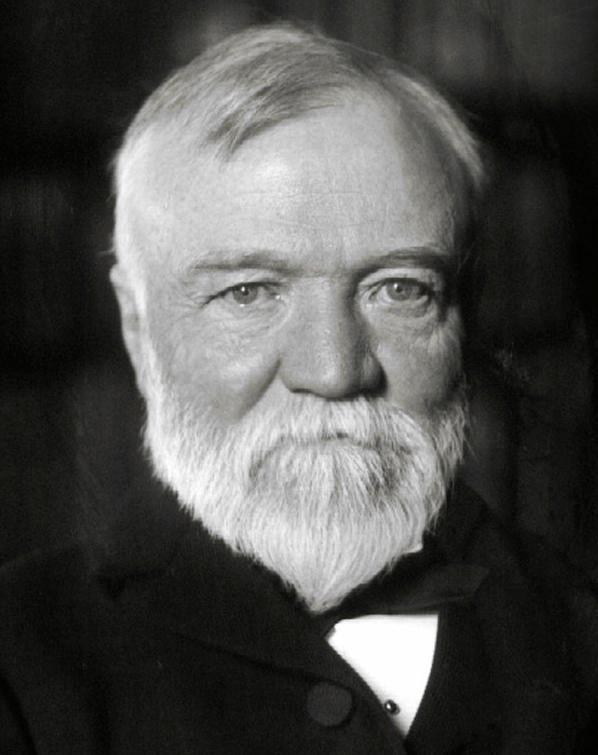

Carnegie

came with his very poor parents from Scotland to Pittsburgh in 1848 at

age thirteen, to live with relatives, and soon found a menial job to

help support the family. But he quickly taught himself to read Morse

Code messages without having to first translate them, impressing

officials at the Pennsylvania Railroad who hired him for just such

work. Obvious to his supervisor, Carnegie was an eager and fast

learner, and as he studied the larger world of business he proved to be

a great strategic thinker – one who thought about how different

industrial operations could be combined to produce a complete in-house

operation, from securing a company's own raw materials, to building its

own machinery, and shipping on its own carriers to its own distribution

centers. Taking up this process of industrial combination himself,

Carnegie detected the central importance of the iron industry and set

up his own company to build the iron bridges that would be needed by

the railroad industry. He then branched into the world of iron

production, supplying his bridge company with its own iron. He then

advanced to the bigger business of steel production, assembling a huge

team of steel engineers, and soon was helping America to outpace

Britain and Germany (Prussia) in steel production. He then complemented

this business by going into the coal/coke business to supply his

ever-improving furnaces with their own fuel. His operations were so

efficient that he was able to slash steel prices, increasing immensely

the demand for his steel production. By the end of the 1800s Carnegie

was producing steel at the rate of 6,000 tons per day. Carnegie

came with his very poor parents from Scotland to Pittsburgh in 1848 at

age thirteen, to live with relatives, and soon found a menial job to

help support the family. But he quickly taught himself to read Morse

Code messages without having to first translate them, impressing

officials at the Pennsylvania Railroad who hired him for just such

work. Obvious to his supervisor, Carnegie was an eager and fast

learner, and as he studied the larger world of business he proved to be

a great strategic thinker – one who thought about how different

industrial operations could be combined to produce a complete in-house

operation, from securing a company's own raw materials, to building its

own machinery, and shipping on its own carriers to its own distribution

centers. Taking up this process of industrial combination himself,

Carnegie detected the central importance of the iron industry and set

up his own company to build the iron bridges that would be needed by

the railroad industry. He then branched into the world of iron

production, supplying his bridge company with its own iron. He then

advanced to the bigger business of steel production, assembling a huge

team of steel engineers, and soon was helping America to outpace

Britain and Germany (Prussia) in steel production. He then complemented

this business by going into the coal/coke business to supply his

ever-improving furnaces with their own fuel. His operations were so

efficient that he was able to slash steel prices, increasing immensely

the demand for his steel production. By the end of the 1800s Carnegie

was producing steel at the rate of 6,000 tons per day.

But his aggressive industrial

empire-building put him at odds with his skilled laborers (as opposed

to the larger unskilled work-force he employed), who were driven less

by a desire for personal success than by a desire to see high wage

rates applied collectively to their craft union. As Carnegie viewed

matters, this was designed merely to produce among the skilled workers

a sense of wage and labor security rather than individual opportunity

for advancement. And worse, the union seemed to be running his

Homestead Plant ever since their victory in the 1889 strike. Thus when

in 1892 Carnegie's aggressive corporate supervisor Henry Clay Frick

decided to break the growing power of the craft union by declaring a

huge reduction in skilled workers' wages, a massive strike was again

called by the union at the huge Homestead plant. (This strike Frick

would have to deal with himself because Carnegie was back in Europe at

the time). The strike was finally broken by the heavy-handed measures

of the Pinkerton agents (resulting in deaths on both sides of the

conflict). And Frick was shot twice by a frenzied anarchist, but

survived the ordeal, the shooting helping to stir a general antipathy

against the striking workers.

Soon after this, Carnegie was

ready to get out of the business world (the Carnegie Steel Company had

by that time achieved the awesome goal of producing more steel than all

of Britain's mills combined!) and in 1901 sold his entire operation to

the financial titan J.P. Morgan for $480 million (the largest such

corporate transaction ever, amounting to over $13 billion in today's

dollars), thus helping to create the United States Steel Corporation.

This also made Morgan the uncontested giant of the American financial

world and Carnegie a very rich man, though over the next years Carnegie

would give most of that wealth away to various charities and social

endeavors and spend the rest of his life traveling.

1Charles B. Spahr, An Essay on the Present Distribution of Wealth in the United States, New York: T.Y. Crowell & Co.,1896, p. 69.

2This

would make him the second richest man in American history, ranking only

behind Rockefeller. The $100 million would be approximately equivalent

to $150 billion in today's dollars. Interestingly, he lived modestly.

All the lavish Vanderbilt estates that were built across the American

East were actually commissioned later by his descendants.

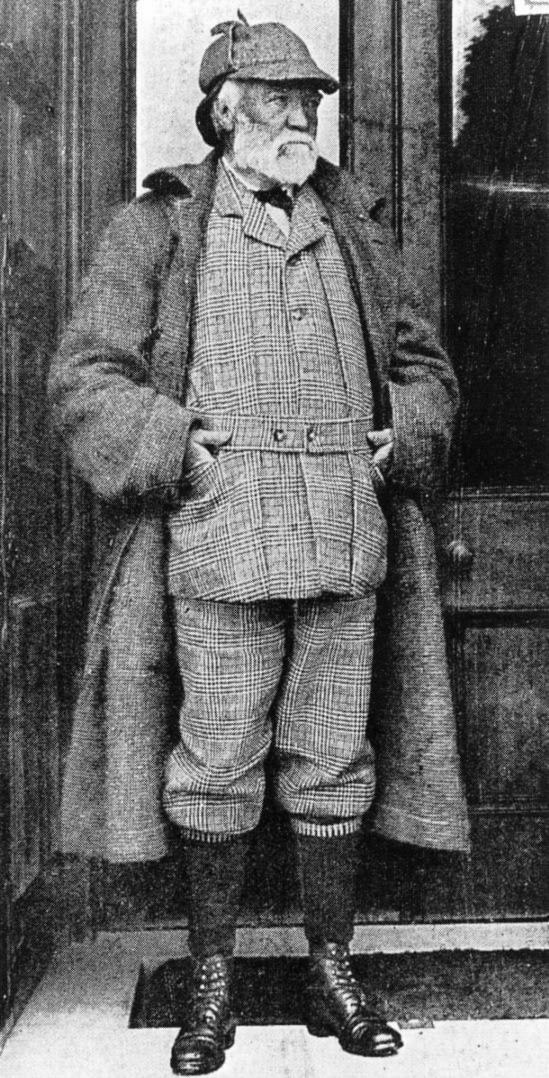

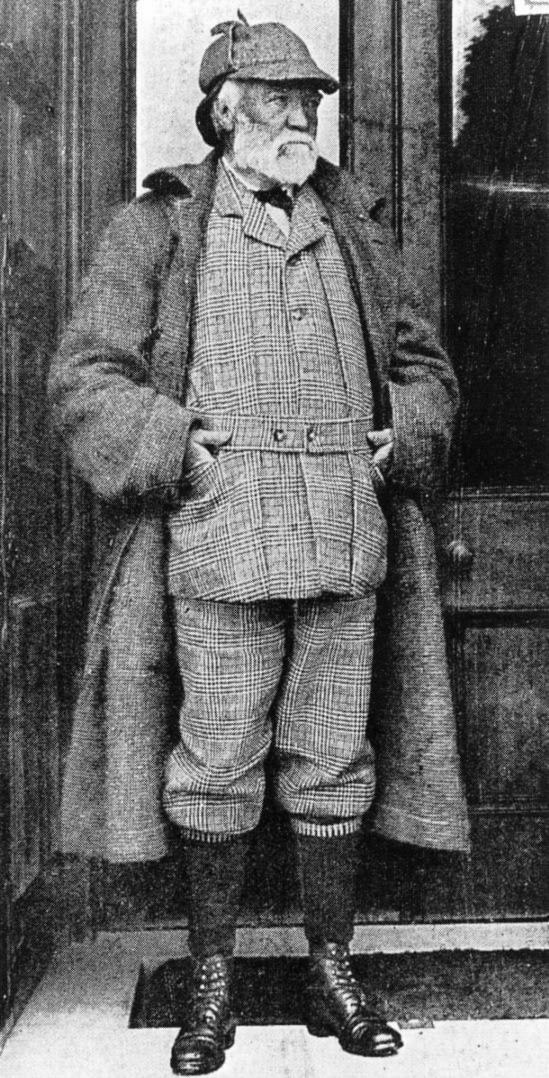

Andrew Carnegie in his Scottish

attire

Andrew Carnegie in his Scottish

attire

|

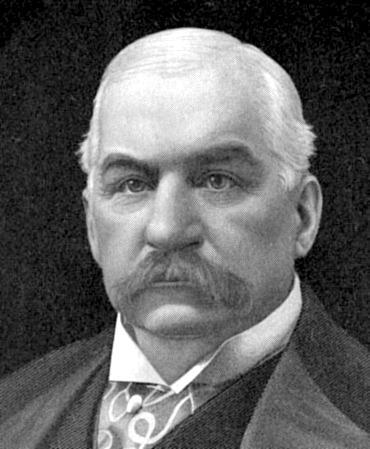

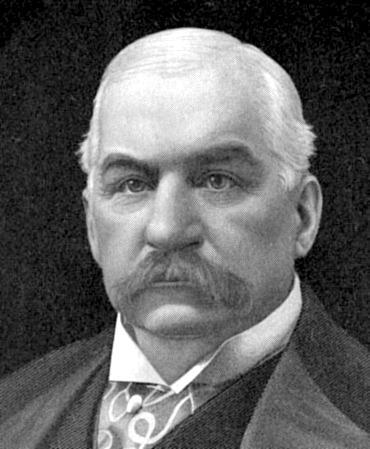

Morgan

was born in 1837 at the opposite end of the social scale from Carnegie,

Morgan being the son of a very successful Connecticut businessman and

banker, schooled in his youth at fashionable schools in Boston,

Switzerland and Germany. Finishing his schooling, he joined his

father's banking office in London for a year before returning to the

States to work for his father's company in New York City. He was a

clever financier, for instance during the Civil War purchasing 5,000

rifles from a Union depot at $3.50 and then reselling them to the U.S.

Army for $22 each! Morgan

was born in 1837 at the opposite end of the social scale from Carnegie,

Morgan being the son of a very successful Connecticut businessman and

banker, schooled in his youth at fashionable schools in Boston,

Switzerland and Germany. Finishing his schooling, he joined his

father's banking office in London for a year before returning to the

States to work for his father's company in New York City. He was a

clever financier, for instance during the Civil War purchasing 5,000

rifles from a Union depot at $3.50 and then reselling them to the U.S.

Army for $22 each!

Over the years he demonstrated his skill

at buying up struggling companies at bargain rates and then

reorganizing them into profitable operations. He even at one point came

to the aid of the U.S. Treasury in the midst of the Panic of 1893, when

by 1895 the Federal Treasury was nearly out of gold and facing

financial default. Morgan joined with the Rothschild bankers of Paris

to offer to sell the government 3.5 million ounces of gold in exchange

for thirty-year bonds. At first U.S. President Cleveland turned down

the offer, but then realizing how close the government was to default,

finally accepted Morgan's offer. It indeed saved the status of the U.S.

Treasury, but undercut Cleveland's standing with the agrarian wing of

his Democratic Party.

Again in 1907 Morgan stepped in to rescue

the American economy, this time caused by a massive sell-off on Wall

Street after the failure of a large copper venture threatened to pull

down a number of banks that had invested heavily in the venture

(actually Knickerbocker, New York's third largest trust company, did

fail). This crisis was so big that Morgan did not attempt to answer the

challenge alone, but gathered a number of other New York banks to join

him in putting money back into Wall Street and restoring investors'

confidence, thus averting a stock market collapse.

Another crisis soon followed, this time

caused by the collapse of a major industrial conglomerate invested in

coal, iron, and railroads. With President Teddy Roosevelt's permission,

Morgan stepped in to take over the fallen conglomerate, aware that this

would invite charges of monopolistic behavior. But it had to be done to

avert yet another panic in the world of American investment.

But as a result of these interventions,

the U.S. government finally (1913) made the move to set up a government

agency, the Federal Reserve, to intervene when such economic crises

began to show signs of developing. In a sense, Morgan himself had shown

the U.S. government the proper procedure by which to intervene when

necessary, contributing greatly to the stability of the U.S. economy,

which throughout the 1800s had experienced one speculative crisis after

another.

|

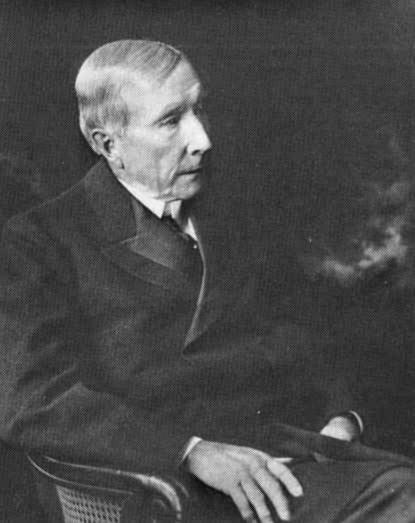

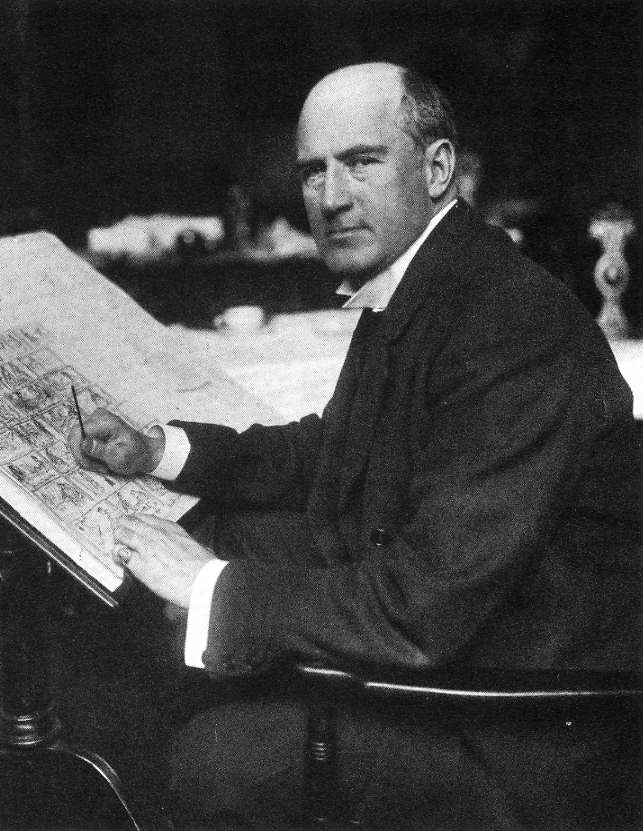

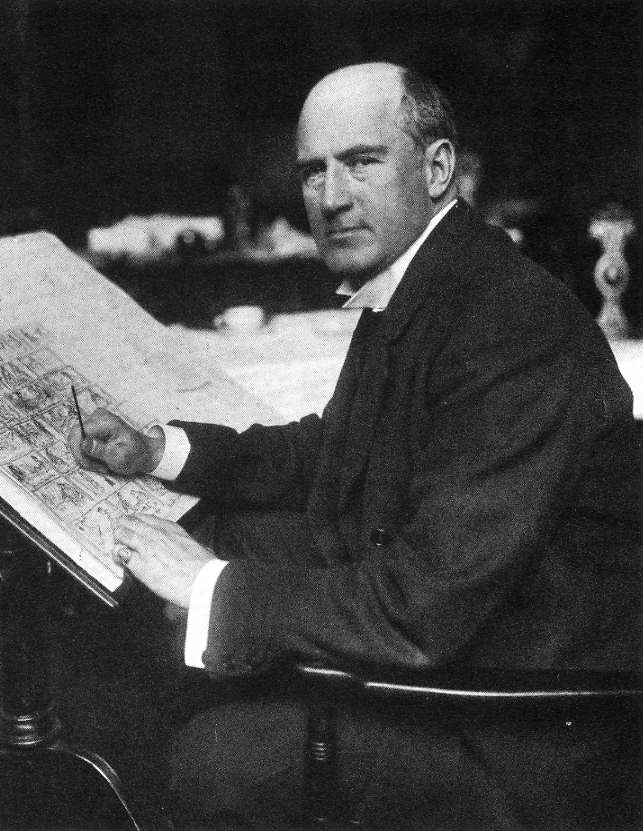

J.P. Morgan with his daughter

Louisa and son J.P., Jr.

J.P. Morgan with his daughter

Louisa and son J.P., Jr.

John Pierpoint Morgan

(1837-1913)

John Pierpoint Morgan

(1837-1913)

Frederick W. Nash / William

Howard Taft National Historic Site

|

Rockefeller

was raised in tough circumstances in upstate New York and then in Ohio,

his father being a wandering con-man who only infrequently visited the

home, his mother however being a very strong, positive influence on his

life. As a youth he proved himself to be very bright, quick with

numbers, hard-working, and loving learning, putting himself through a

large amount of schooling. He was also a person of deep Christian

faith. Together these elements made him an eager challenger of the

larger world. Rockefeller

was raised in tough circumstances in upstate New York and then in Ohio,

his father being a wandering con-man who only infrequently visited the

home, his mother however being a very strong, positive influence on his

life. As a youth he proved himself to be very bright, quick with

numbers, hard-working, and loving learning, putting himself through a

large amount of schooling. He was also a person of deep Christian

faith. Together these elements made him an eager challenger of the

larger world.

During the Civil War he and his brother

raised the capital to found a business providing produce to the Union

armies, and then the two of them in 1863 joined a team of investors to

build in Cleveland's fast-growing industrial area an oil refinery

designed to produce kerosene, helping to move the country away from

expensive whale oil as the source of its lighting. In 1865 he bought

out the leading partners of the business and through considerable

borrowing put himself (and the remaining investors, including his

brother) in a well-placed position within an economy turning more and

more to the use of kerosene.

By 1870 he moved to establish the

Standard Oil Company, which quickly became Ohio's largest oil company.

Then moving into the shipping business, he was able to acquire for his

oil business special railroad rates that allowed him vast advantage in

his competition with smaller oil companies, which he was quick to buy

out when they stumbled. Then in 1874 he signed a secret deal with his

largest New York competitors, Pratt and Rogers, to buy out their oil

company and bring the two on his company as partners. And thus

Rockefeller proceeded to move through the infant oil industry, buying

out company after company until, by the end of the 1870s, Standard Oil

owned 90 percent of America's oil business. He even at one point took

on the huge Pennsylvania Railroad Company, starting a price war in

shipping rates, which finally forced the railroad to sell its own oil

interests to Standard Oil (actually Rockefeller was moving away from

shipping by rail to shipping by pipeline). But this in turn brought

charges of monopolistic practices (not the first time, however, nor the

last) in the courts of Pennsylvania and other states. These court cases

Rockefeller found himself battling constantly, gaining for Rockefeller

a very negative national reputation.

Adding to this negative image was when in

1882 Rockefeller set up the Standard Oil Trust, a move to bring the

many separate state corporations under a single domain (at that time

companies were licensed to operate within only the state granting the

corporate license). Not only did the creation of this new trust produce

a huge outcry of monopoly in the nation's press, other corporations,

seeing the benefits of this move, were quick to set up similar

organizations, birthing the age of the massive American trust

companies. He also birthed the practice (taken up by New York's

National Petroleum Exchange) of selling oil futures on the open market

as shares or certificates based on oil held in storage, thus making the

pricing of oil a public matter.

Eventually Rockefeller ventured into the

growing world of international oil production, then moved from kerosene

production into the business of natural gas, and even the refinement of

gasoline (previously considered just a wasteful byproduct of kerosene

production), just as the world of automobiles, with their new internal

combustion engines, was opening up.

But the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act,

originally designed to break up labor organizations, would soon be

turned against Rockefeller, especially as he moved to acquire oil

fields in other American states, his vast oil fields in Pennsylvania

beginning to play out. He also entered the business of iron ore

production and shipment with Carnegie, causing a huge public uproar.

With the arrival of the 20th century, Rockefeller found himself under

constant attack, by U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt, wielding the

Sherman Antitrust Act wherever he could; by Ida Tarbell, publishing a

lengthy exposé on Standard Oil’s underhanded business practices; and

finally in 1911 by the U.S. Supreme Court, which handed down the

decision that as a monopoly violating the Sherman Act, Standard Oil had

to be broken up into thirty-four separate companies (eventually

becoming Conoco, Amoco, Chevron, Exxon, Mobil, Sohio, Pennzoil, etc.).

Yet Rockefeller remained a significant stockholder in these various

companies, and the oil business continued to be personally very

profitable for Rockefeller. This eventually made Rockefeller the

richest man in the world at the time (and by comparison, even still

today!).

But like Carnegie, Rockefeller’s business

sense was based on a larger view of his responsibilities to the world

around him. He never saw the making of money as evil, seeing how though

some people would fall by the wayside in the competitive world of

business and finance, the overall effect was clearly one of economic

advancement for the society as a whole.

True, some benefitted vastly more than

others in this trend, but even here Rockefeller felt a sense of

responsibility to his world, setting up charity organizations designed

to help the young and ambitious climb to greater social heights.

Indeed, this was part of his understanding of his Christian

responsibilities, which began with his church tithing even as a

teenager, and which interestingly included teaching Bible at the

Baptist church he attended as an adult. But his charity helped turn by

1900 a small Baptist college into the University of Chicago, his grants

to church mission produced the Central Philippine University in 1905,

and ultimately his sense of charity led to the creation of an

outstanding medical research center in New York City. In 1913 he

established the Rockefeller Foundation, granting it $250 million to aid

in medical research and training, and in 1918, granted $550 million for

another foundation (later absorbed into the Rockefeller Foundation) for

social research.

|

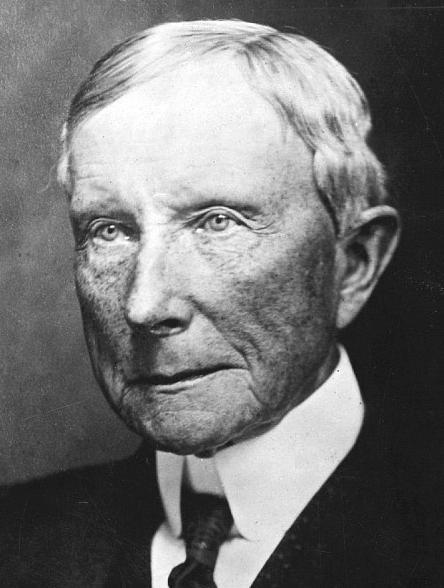

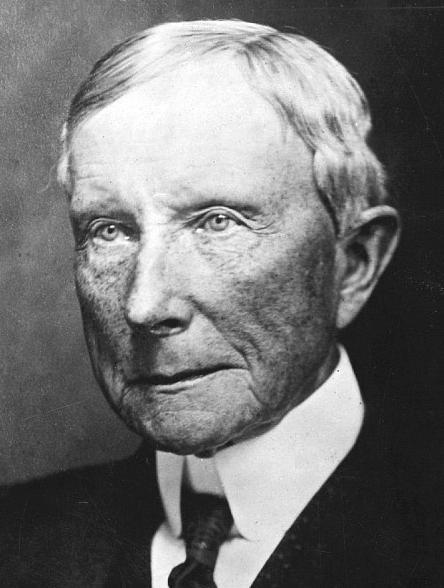

John D. Rockefeller – founder

of Standard Oil Company and America's first billionaire

John D. Rockefeller – founder

of Standard Oil Company and America's first billionaire

Library of

Congress

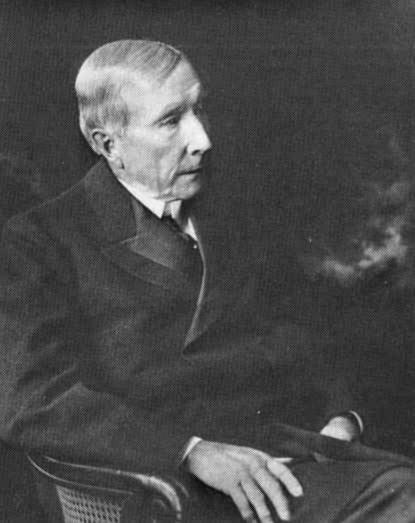

John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937)

and his son, John Jr.

John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937)

and his son, John Jr.

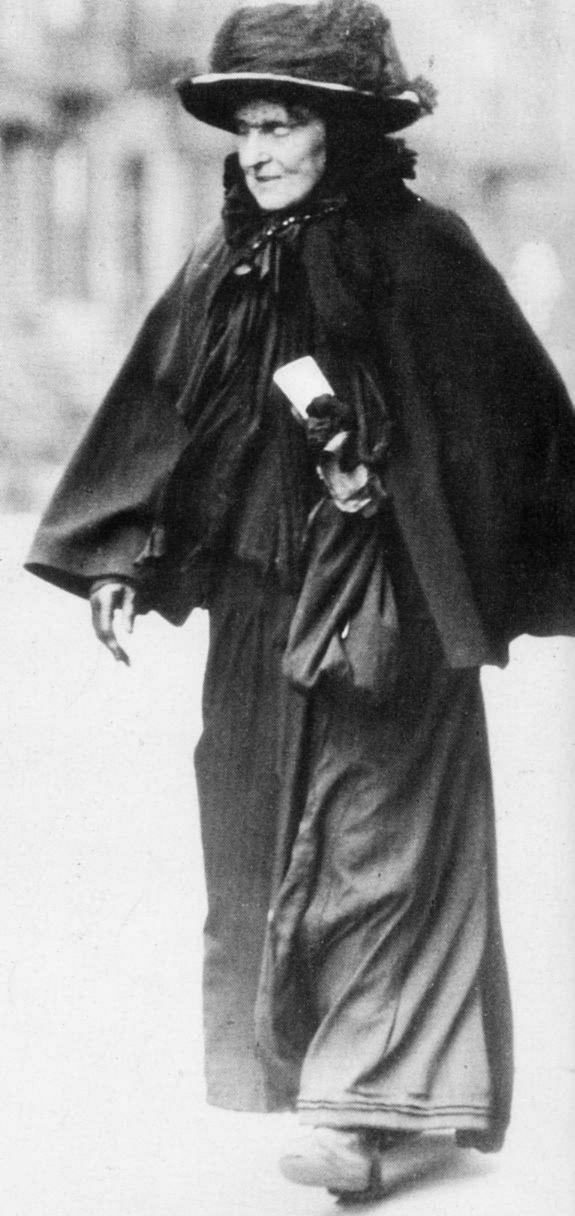

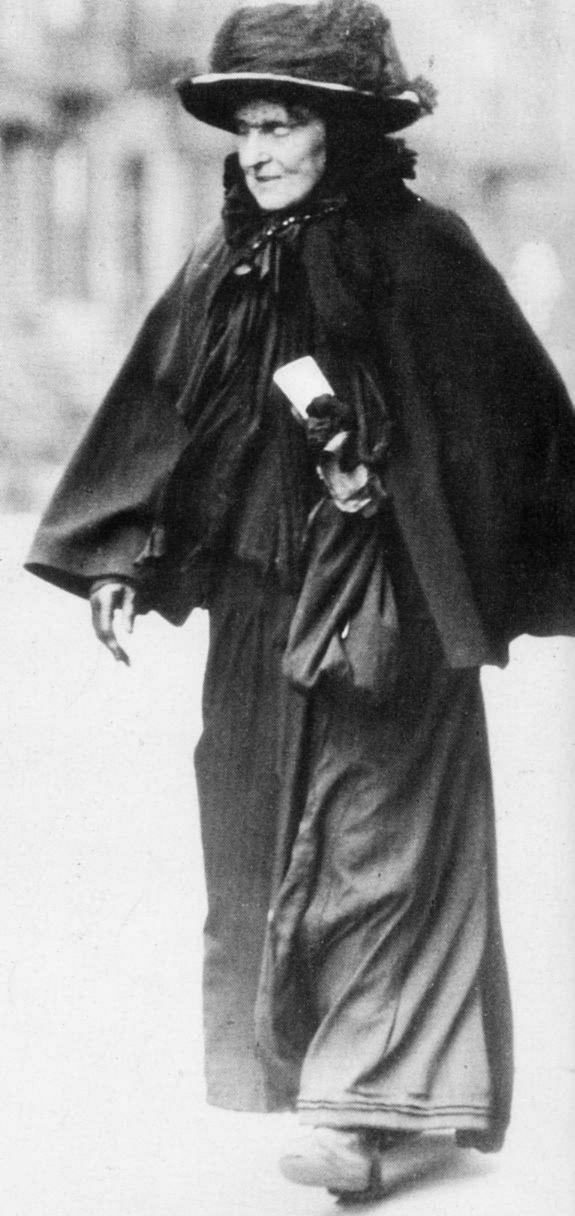

Hetty Green – America's

wealthiest

woman (and most miserly) (1835-1916)

Hetty Green – America's

wealthiest

woman (and most miserly) (1835-1916)

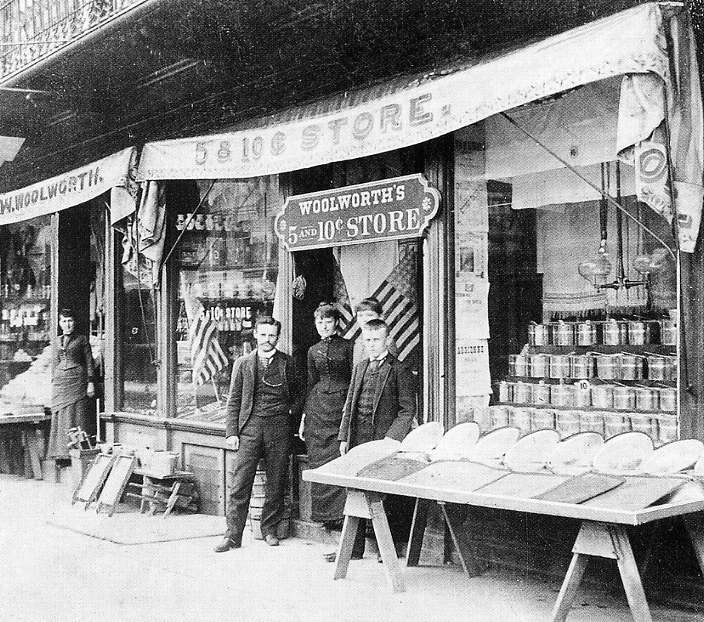

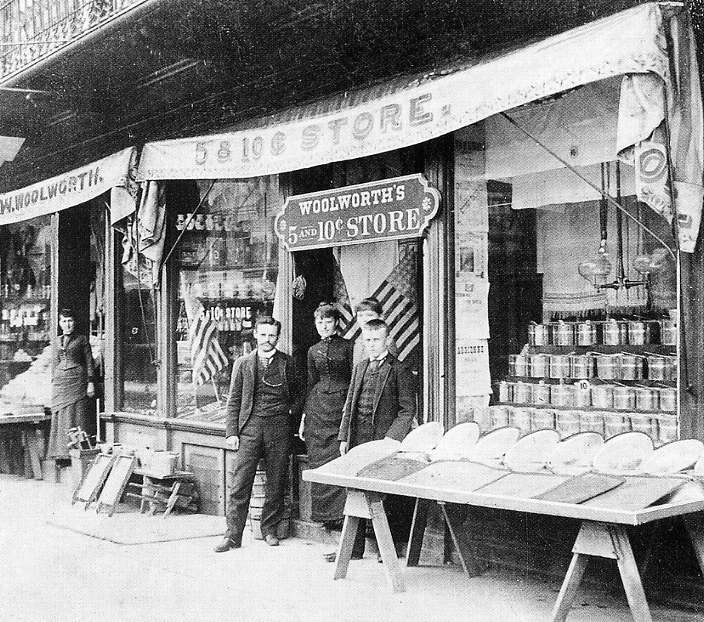

Frank W. Woolworth and his

first 5 and 10 cent store in Lancaster, PA – 1879.

Frank W. Woolworth and his

first 5 and 10 cent store in Lancaster, PA – 1879.

At the height of his retail

chain's success it owned 8,000 stores worldwide.

THE EXTRAVAGANCE OF THIS WEALTHY ELITE IN CONTRAST WITH THE OLDER PURITAN IDEALS OF YANKEE

AMERICA IS MIND-BOGGLING |

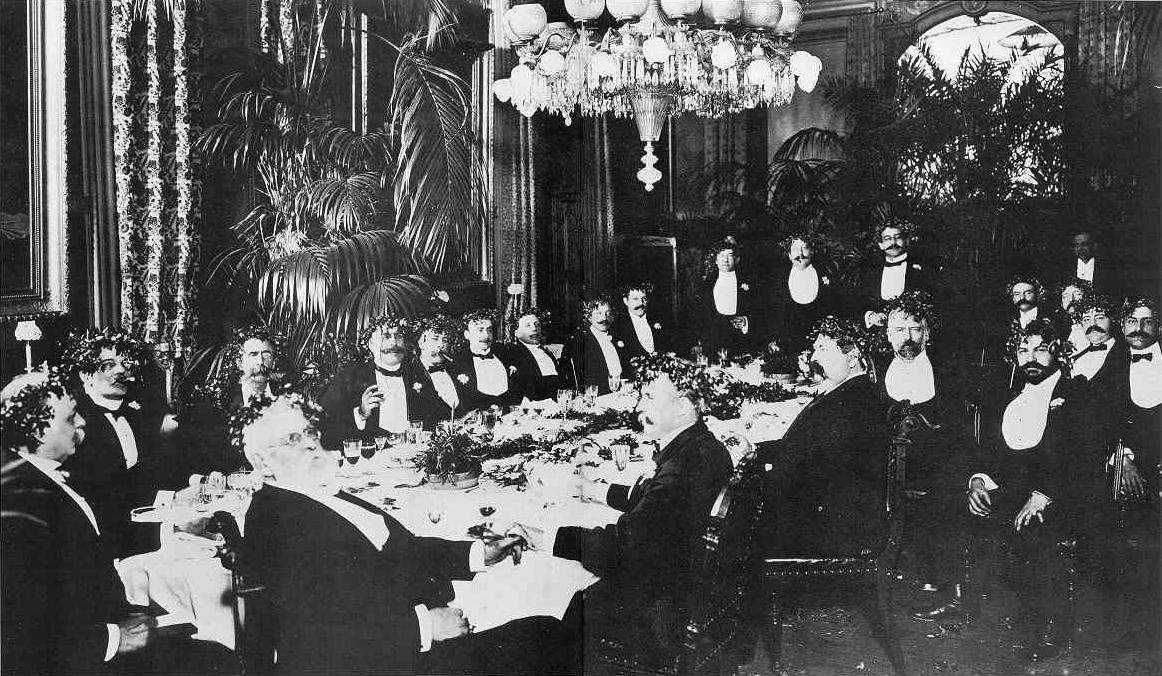

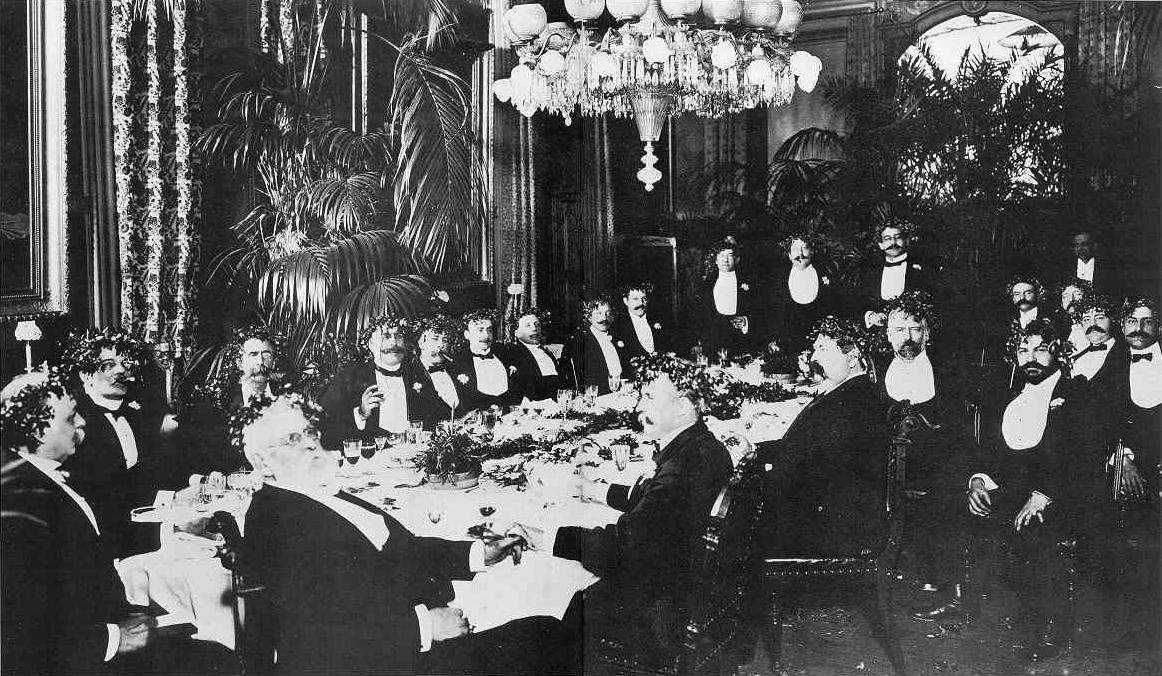

An Olympian fellowship of

America's wealthiest men at a banquet honoring Harrison

Grey Fiske (center) – 1901

An Olympian fellowship of

America's wealthiest men at a banquet honoring Harrison

Grey Fiske (center) – 1901

The Byron Collection, Museum

of the City of New York

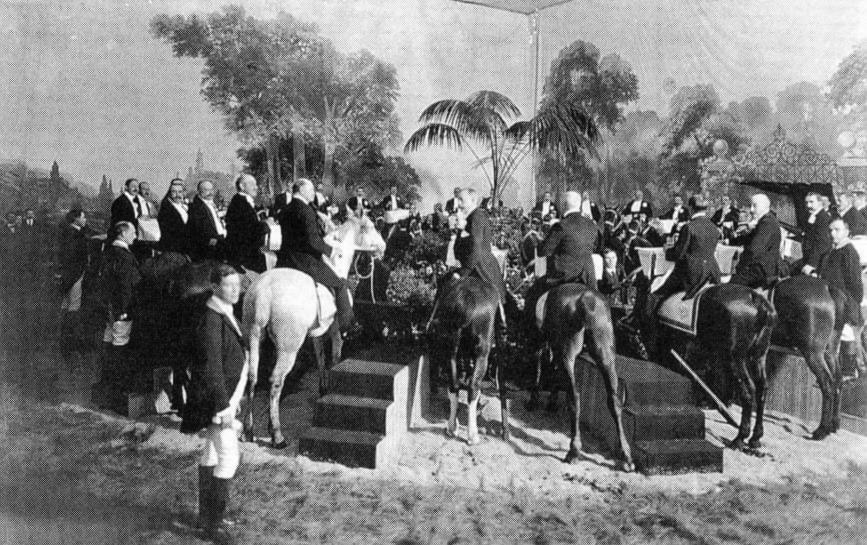

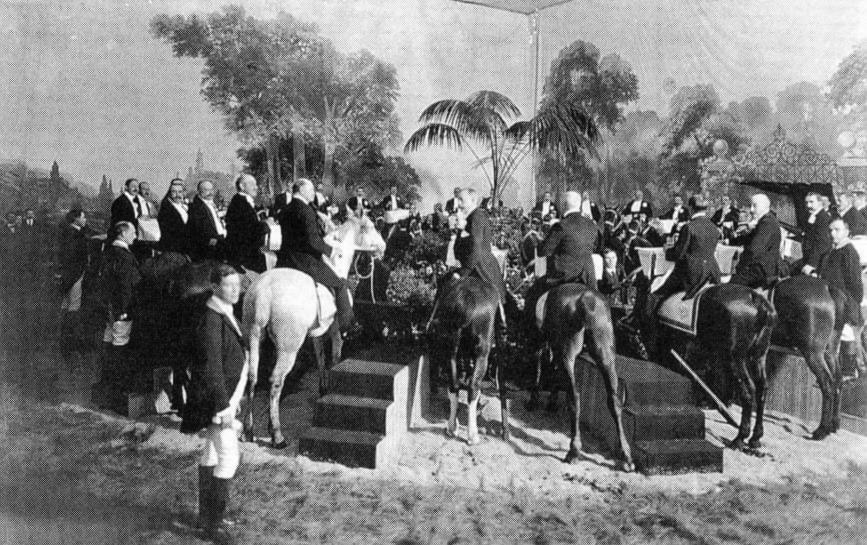

Dinner on horseback at Sherry's

Restaurant – New York, 1903

Dinner on horseback at Sherry's

Restaurant – New York, 1903

Byron / Museum of the City

of New York

One of four Vanderbilt mansions

[Cornelius Vanderbilt's] on 5th Avenue in Manhattan

One of four Vanderbilt mansions

[Cornelius Vanderbilt's] on 5th Avenue in Manhattan

Cornelius Vanderbilt's summer

mansion, "The Breakers," in Newport, Rhode Island

Cornelius Vanderbilt's summer

mansion, "The Breakers," in Newport, Rhode Island

William Vanderbilt's summer

mansion, "Marble House," in Newport

William Vanderbilt's summer

mansion, "Marble House," in Newport

The dining room in William

Vanderbilt's "Marble House"

The dining room in William

Vanderbilt's "Marble House"

Promenading on the Newport

greensward

Promenading on the Newport

greensward

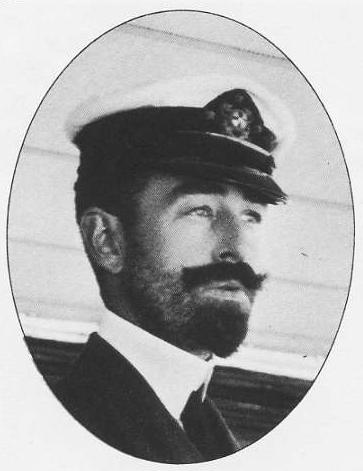

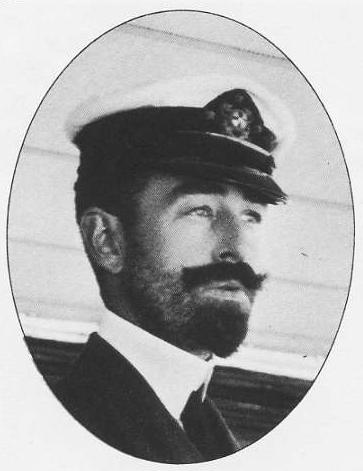

Commodore C.

Vanderbilt

Commodore C.

Vanderbilt

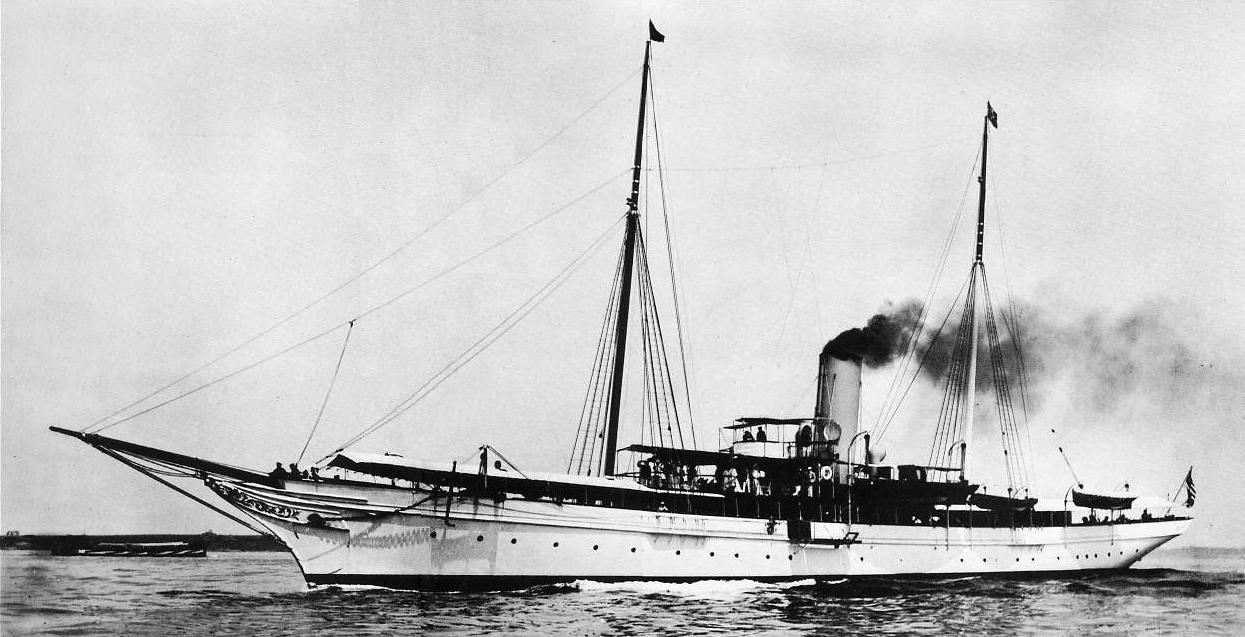

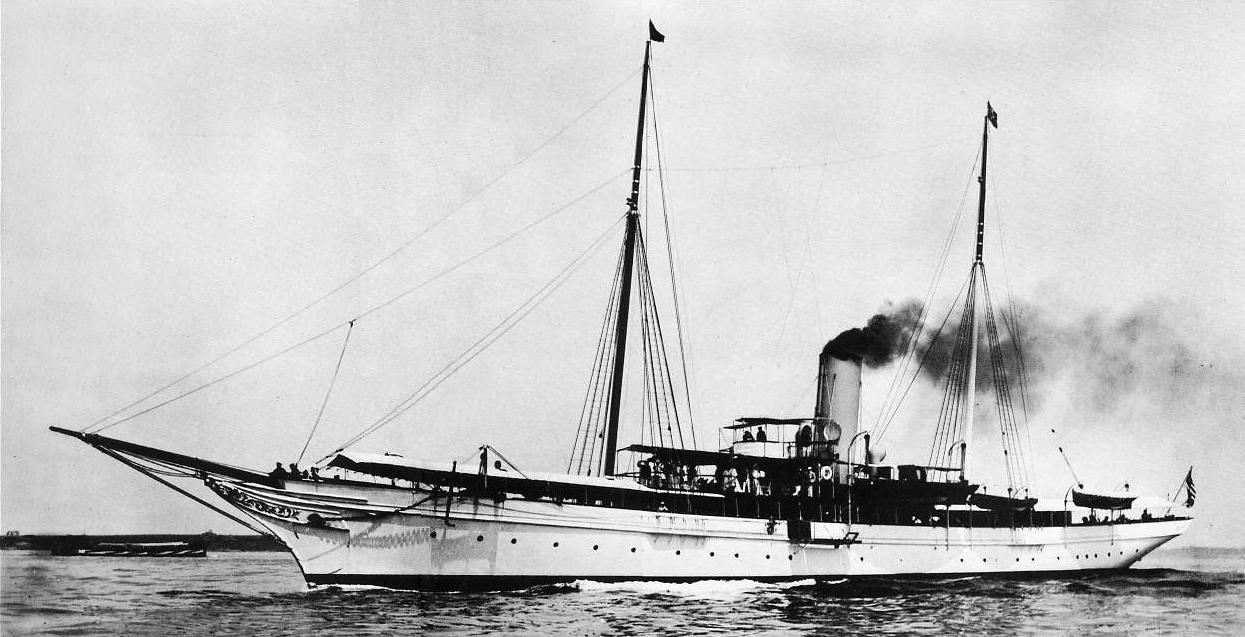

Commodore C. Vanderbilt's

256-foot yacht "North Star"

Commodore C. Vanderbilt's

256-foot yacht "North Star"

The dining room of

"North Star"

The dining room of

"North Star"

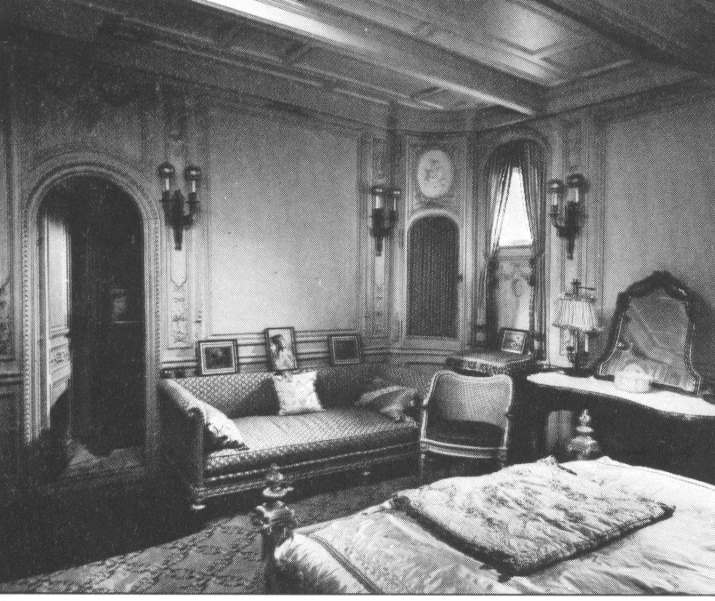

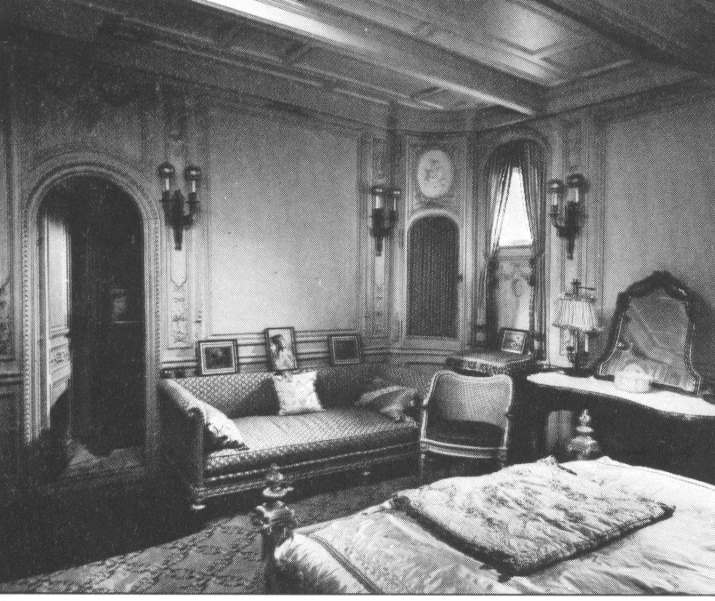

The stateroom of "North

Star"

The stateroom of "North

Star"

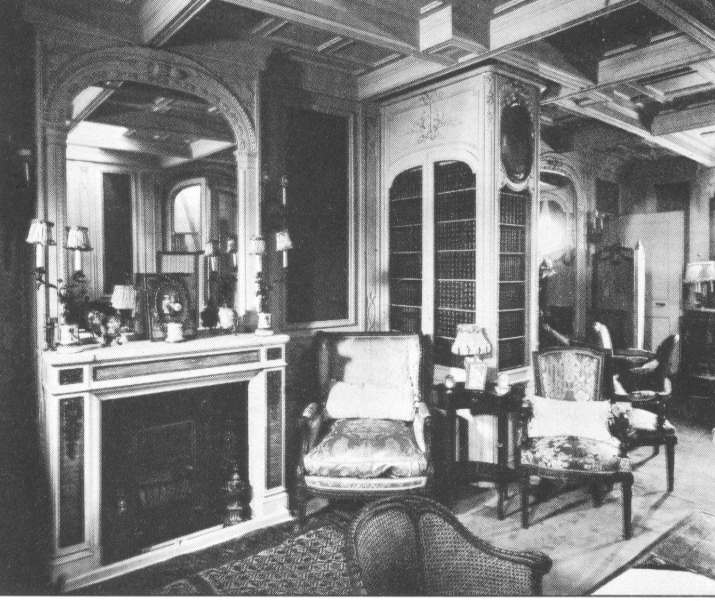

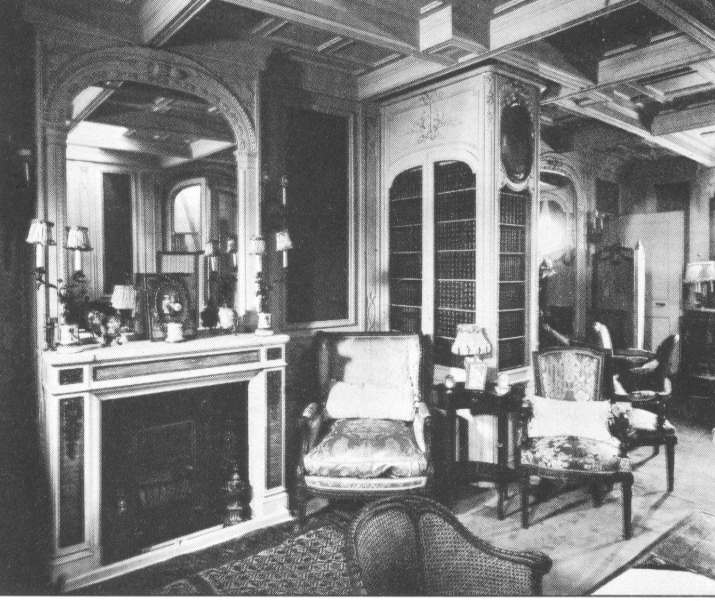

The library of "North

Star"

The library of "North

Star"

Consuelo Vanderbilt (married

to the Duke of Marlborough) at the coronation of Edward VII

Consuelo Vanderbilt (married

to the Duke of Marlborough) at the coronation of Edward VII

THE AMERICAN "MIDDLE CLASS" IS ALSO DOING PRETTY WELL FOR ITSELF |

Comfortable Middle-Class

American Family – 1906

Comfortable Middle-Class

American Family – 1906

The St. Louis World Fair

- 1904

The St. Louis World Fair

- 1904

Daytona Beach, Florida -

1904

Daytona Beach, Florida -

1904

The first Rose Bowl game

in Pasadena, California – New Year's Day 1902

The first Rose Bowl game

in Pasadena, California – New Year's Day 1902

(Michigan beat Stanford

49-0)

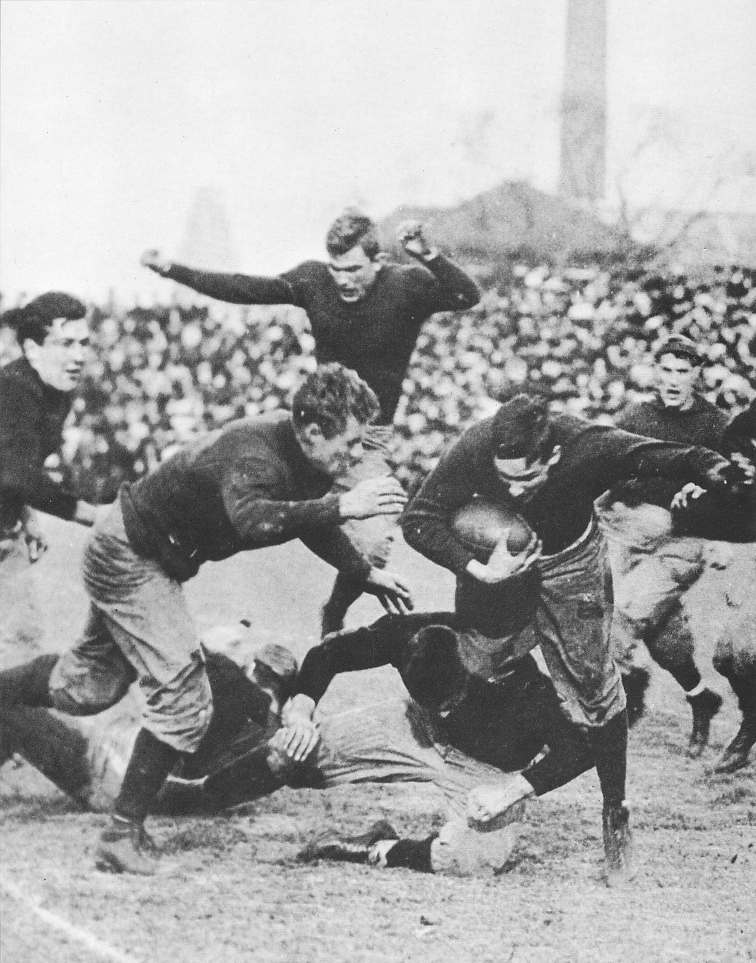

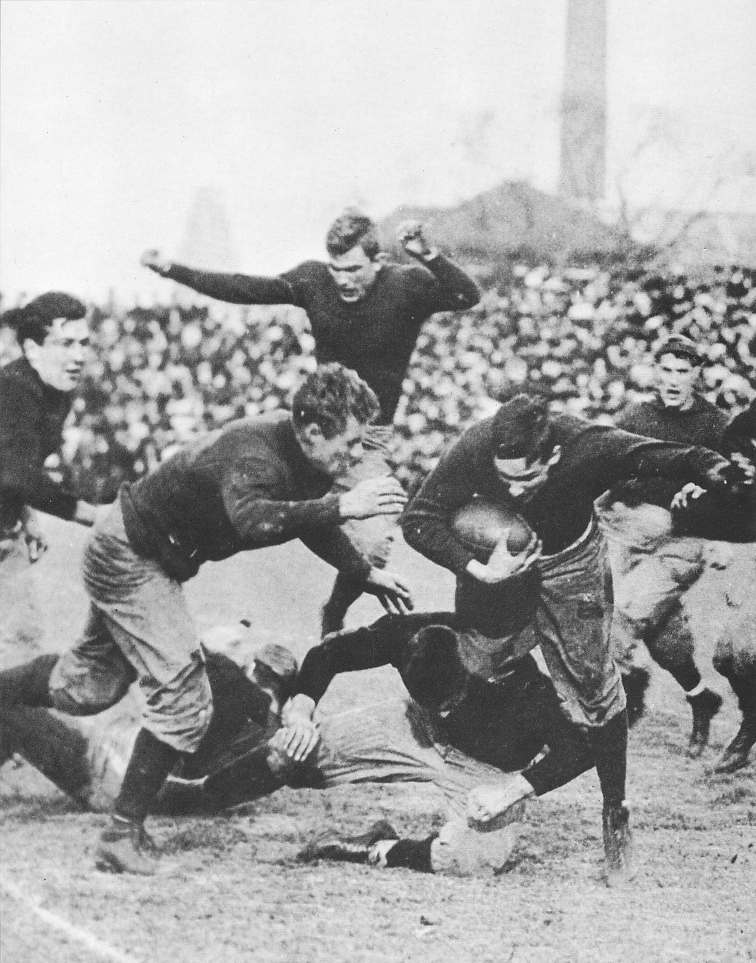

The Harvard-Yale championship

football game of 1907

The Harvard-Yale championship

football game of 1907

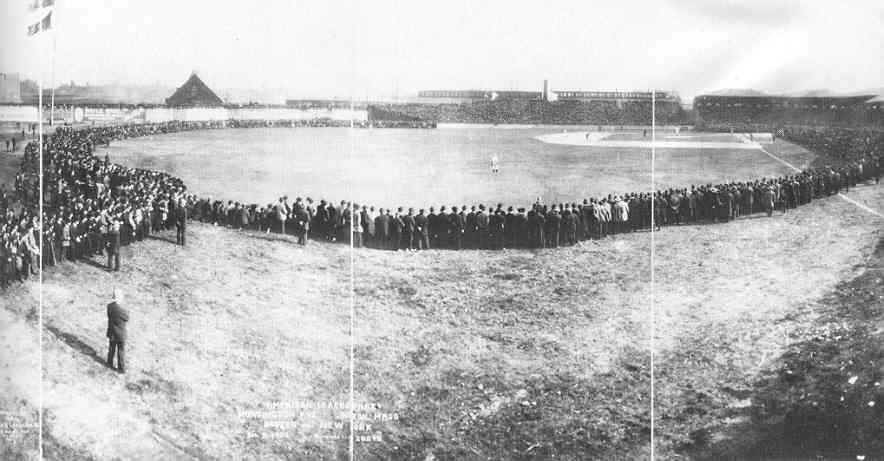

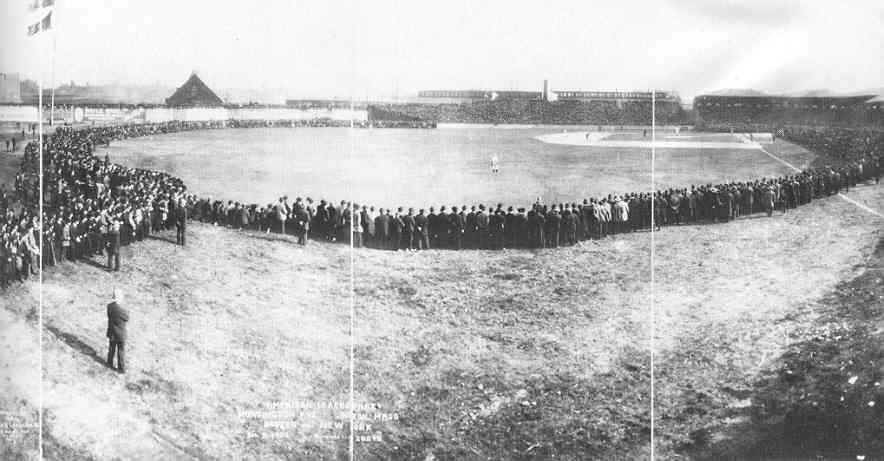

American League Baseball

- Boston vs. New York at Boston – 1904

American League Baseball

- Boston vs. New York at Boston – 1904

Library of

Congress

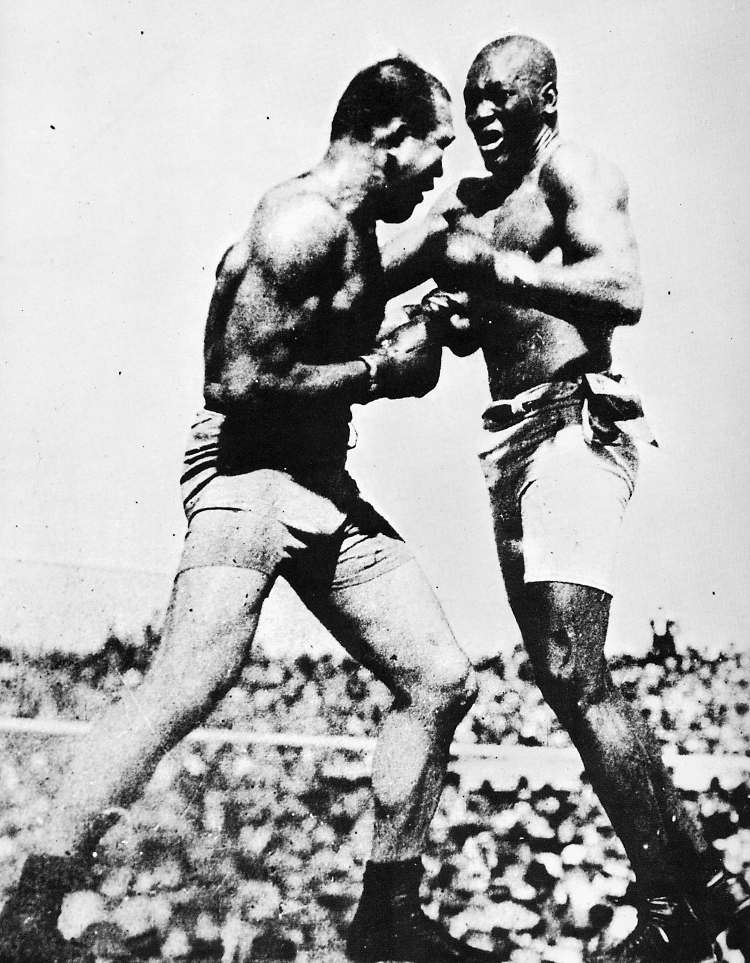

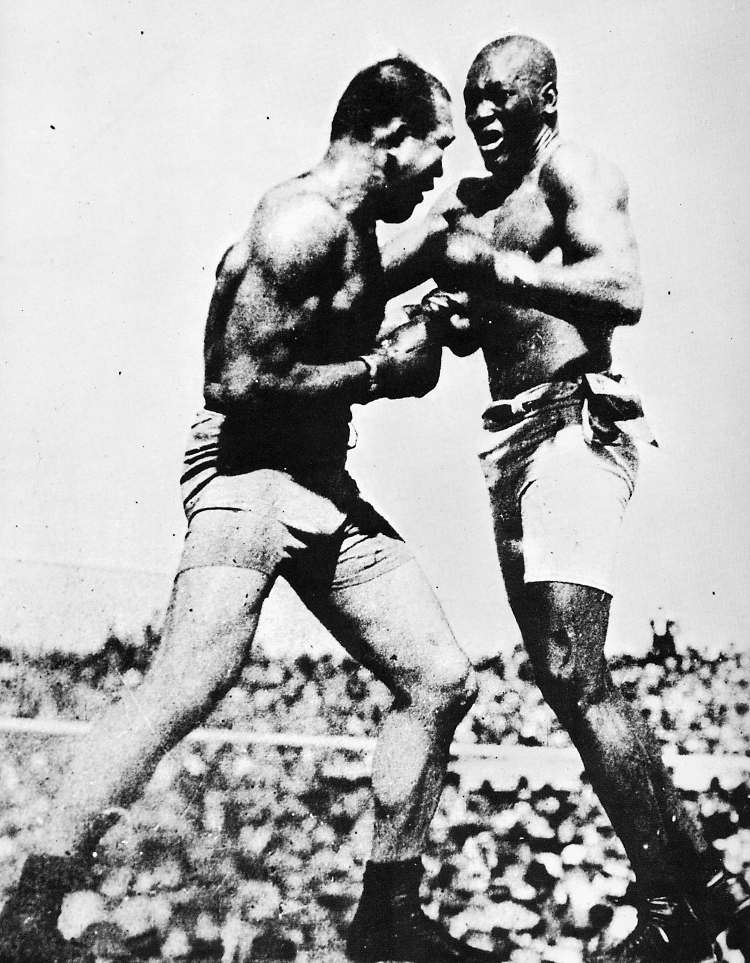

The Jim Jeffries – Jack Jackson

heavyweight championship bout – July 4, 1910

The Jim Jeffries – Jack Jackson

heavyweight championship bout – July 4, 1910

AMERICANS CAN AFFORD EVEN THE LUXURY OF IDEALIZING THE AMERICAN WOMAN |

Dana

Gibson

Dana

Gibson

The Gibson girl – the idealized

American beauty created by artist Dana Gibson

The Gibson girl – the idealized

American beauty created by artist Dana Gibson

Alice Roosevelt, daughter

of the President – "woman of the decade"

Alice Roosevelt, daughter

of the President – "woman of the decade"

OF

COURSE NOT ALL WAS PERFECT IN THE PICTURE OF THE GILDED AGE |

A horrible shattering of

that picture occurred in on April 8, 1906 - the San Francisco earthquake

and fire

San Francisco earthquake

and fire, April 18, 1906

San Francisco earthquake

and fire, April 18, 1906

The San Francisco earthquake

and fire – April 18, 1906

San Francisco Burning – April

18, 1906

San Francisco Burning – April

18, 1906

People on Russian Hill look toward San Francisco's downtown, (including the Hall of Justice, Merchants Exchange, and

Mills Building), burning after being shocked by a powerful earthquake.

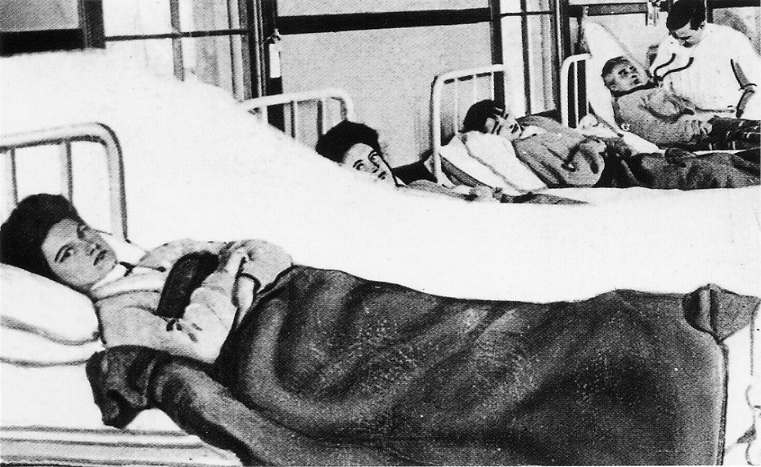

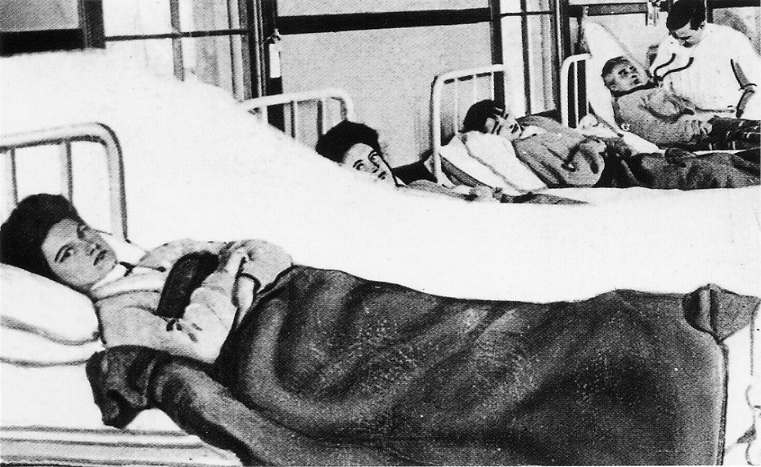

"Typhoid Mary" Mallon – a

cook for wealthy families who caught her disease. Although she was diagnosed

with the disease in 1907, she continued to work under various aliases until

1915 – when she was finally institutionalized for life.

"Typhoid Mary" Mallon – a

cook for wealthy families who caught her disease. Although she was diagnosed

with the disease in 1907, she continued to work under various aliases until

1915 – when she was finally institutionalized for life.

| | |

Capitalism in the "Gilded Age"

Capitalism in the "Gilded Age"

The "Captains of Industry" (or "Robber

The "Captains of Industry" (or "Robber The extravagance of this wealthy elite

The extravagance of this wealthy elite

The American "Middle Class" is doing

The American "Middle Class" is doing Americans can afford even the luxury of

Americans can afford even the luxury of Of course not all was

perfect in the

Of course not all was

perfect in the