11. CAPITALISM ... AND INDUSTRIAL GROWTH

NATIONAL POLITICS DURING THE LATE 1800s

CONTENTS

Dealing with the "spoils system" Dealing with the "spoils system"

The election of 1880 ... and Garfield's The election of 1880 ... and Garfield's

brief presidency

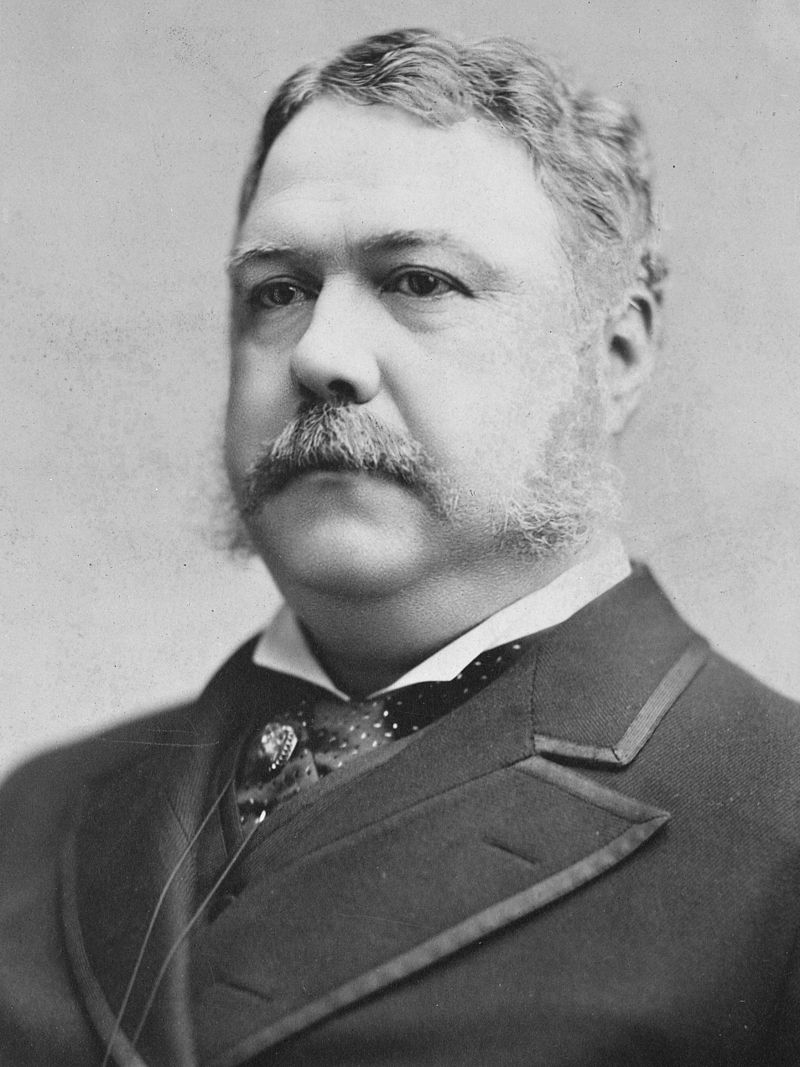

Chester A. Arthur Chester A. Arthur

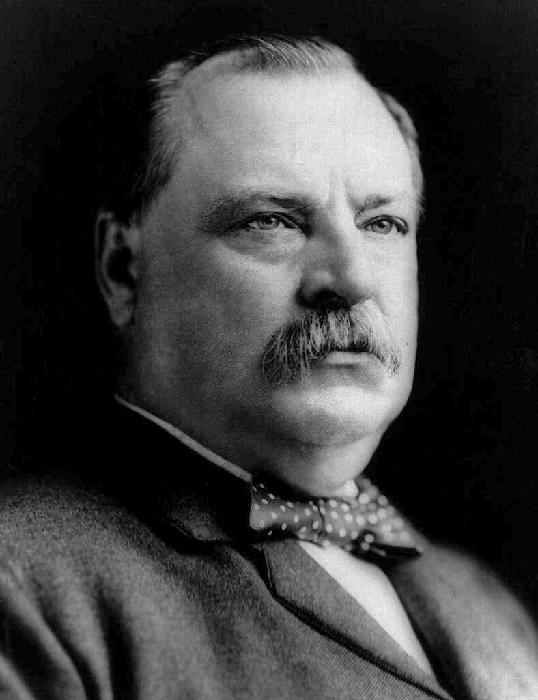

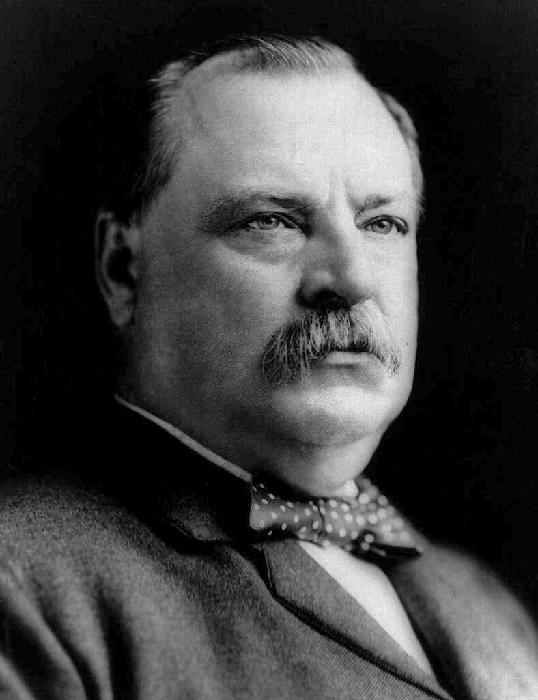

Grover Cleveland Grover Cleveland

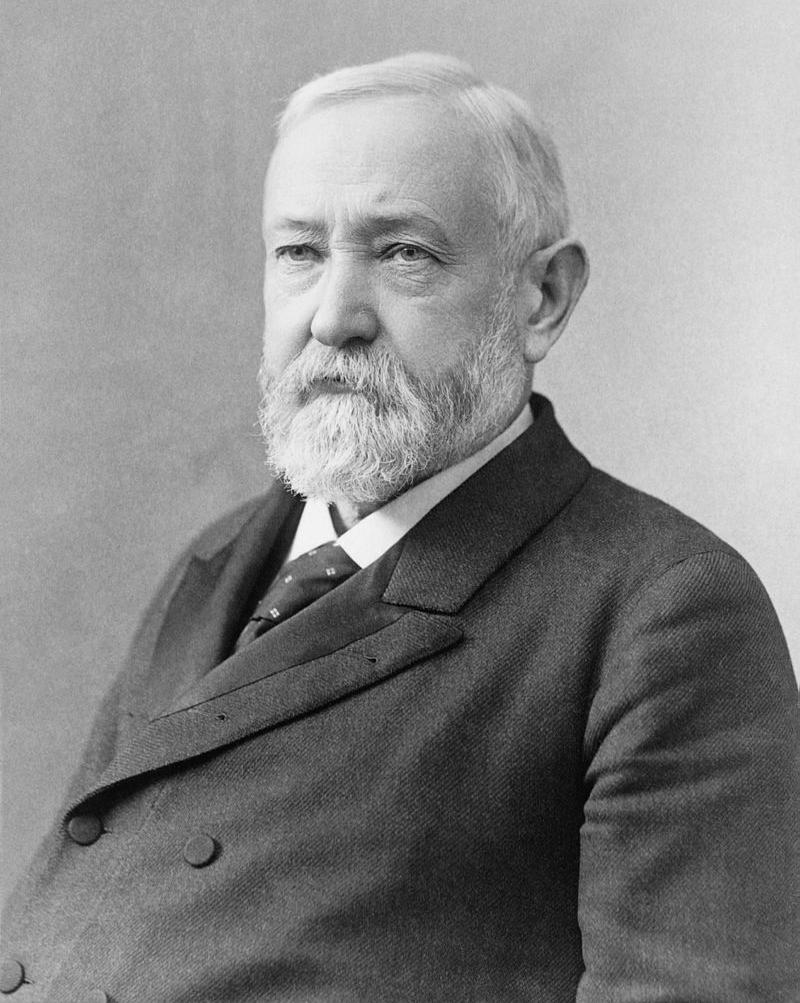

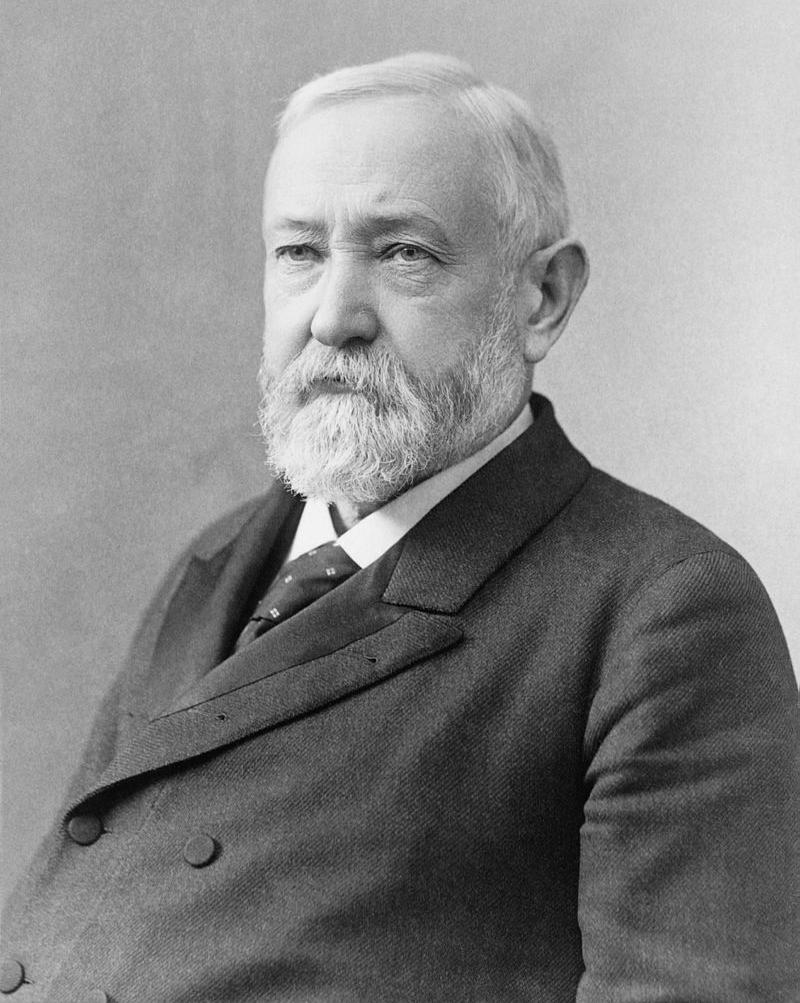

Benjamin Harrison Benjamin Harrison

Cleveland's second term in office Cleveland's second term in office

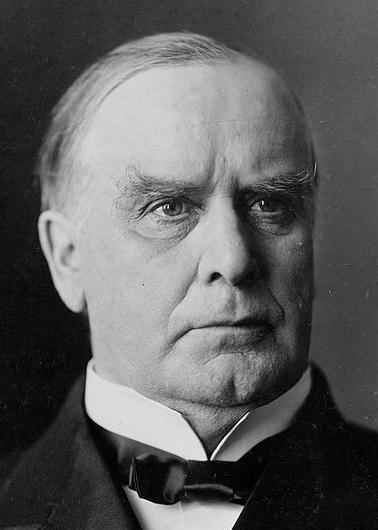

William McKinley brings the 19th century William McKinley brings the 19th century

to a close

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 351-360

DEALING WITH THE "SPOILS SYSTEM"1 |

|

Presidential and congressional politics were

fairly tame during the late 1800s. With the issue of Reconstruction

simply fading away and with the government-financed railroad to the

Pacific completed, the federal government seemed to be called on to

play only a secondary role in the further development of American

society. America seemed to run mostly on the basis of its own

industrial-economic dynamics, rather than on the deep involvement of

the Washington government in the life of the nation, such as was the

case during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Social reform would be a big issue during

this time. But the initiative for action came not from the halls of

Congress or the White House but from the public itself. Through the

publicity of America's newspapers, from books written by social

reformers, from Christian pulpits, much energy would be given to the

idea of perfecting American society. And it would eventually involve

the national government, in the form of legislation designed to firm up

a reform that the public was demanding. But in this, the government

played not the initiating role but merely the confirming role.

One issue however did occupy much

governmental attention: the vast corruption going on within its own

ranks. President Hayes had tried to clean up some of the corruption

left behind by the Grant administration. But Hayes's effort to do so

only weakened his position in the face of the considerable political

forces benefitting from the spoils system of awarding political

appointments as reward for the political support needed to bring

politicians to power. The spoils system was understood simply as how

politics was expected to work. To try to change things would merely

upset the entire political system.

But such spoils became easy targets for

journalists looking for a spectacular story to uncover and report.

Consequently, there was considerable pressure coming from such molders

of public opinion to do something about the problem.

Hayes tried to answer this call for

reform when he took action to remove Chester A. Arthur from the

lucrative (in terms of spoils) job of director of the New York

customs-house. This brought the wrath of New York Boss Conkling, and

the anti-reformist Stalwarts in the U.S. Senate who, with the

Democrats, held up confirmation of Hayes's subsequent government

appointments. Then the Democrats reversed the publicity spotlight,

turning it on the Republican Hayes, bringing up the corrupt nature of

the deal Hayes had worked with the Louisiana governor to get himself

elected to the presidency. But this merely unified Republican Party

support for Hayes, though it hardly appeased the press.

1This

involved the assigning of government jobs and contracts as the reward

for the support needed to bring politicians to power.

THE ELECTION OF 1880 ... AND GARFIELD'S BRIEF

PRESIDENCY |

|

But when election-time came around again, Hayes

could not muster enough support from his Republican Party to get

himself re-nominated. There were a large number of contenders,

including Grant, who was supported by the Stalwarts for a third term.

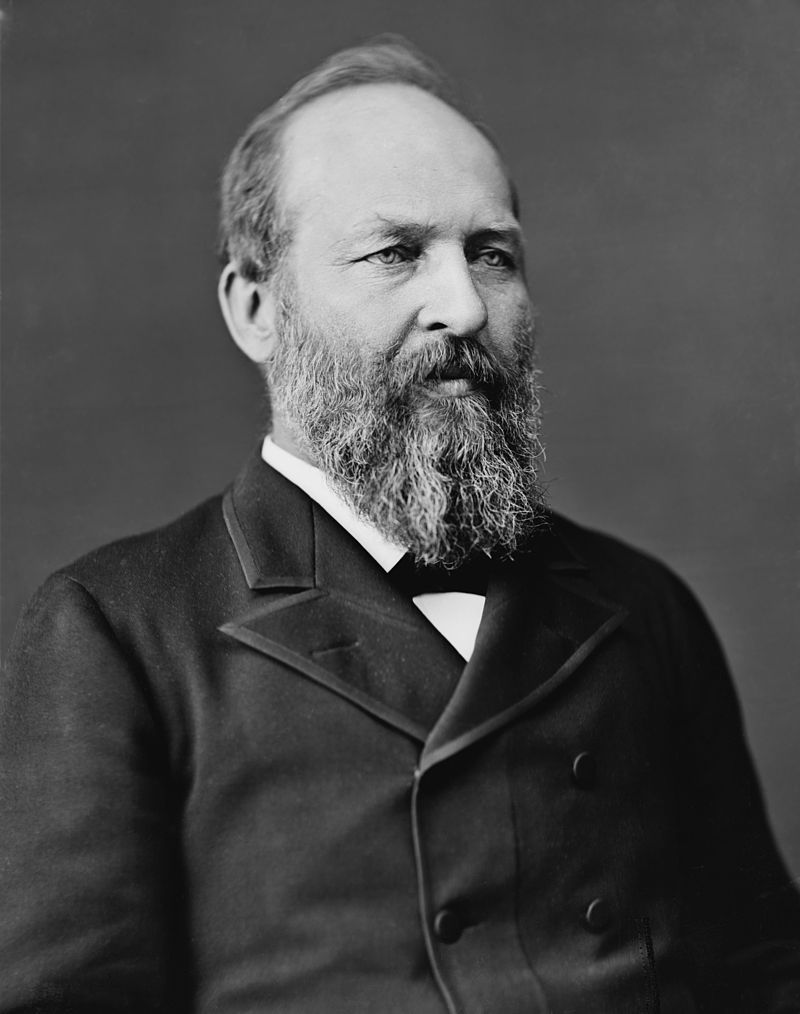

Finally, after 36 ballots, the Republicans turned to a relatively

unknown James A. Garfield, and, to Hayes’s great shock, Chester A.

Arthur as his vice-presidential running-mate.

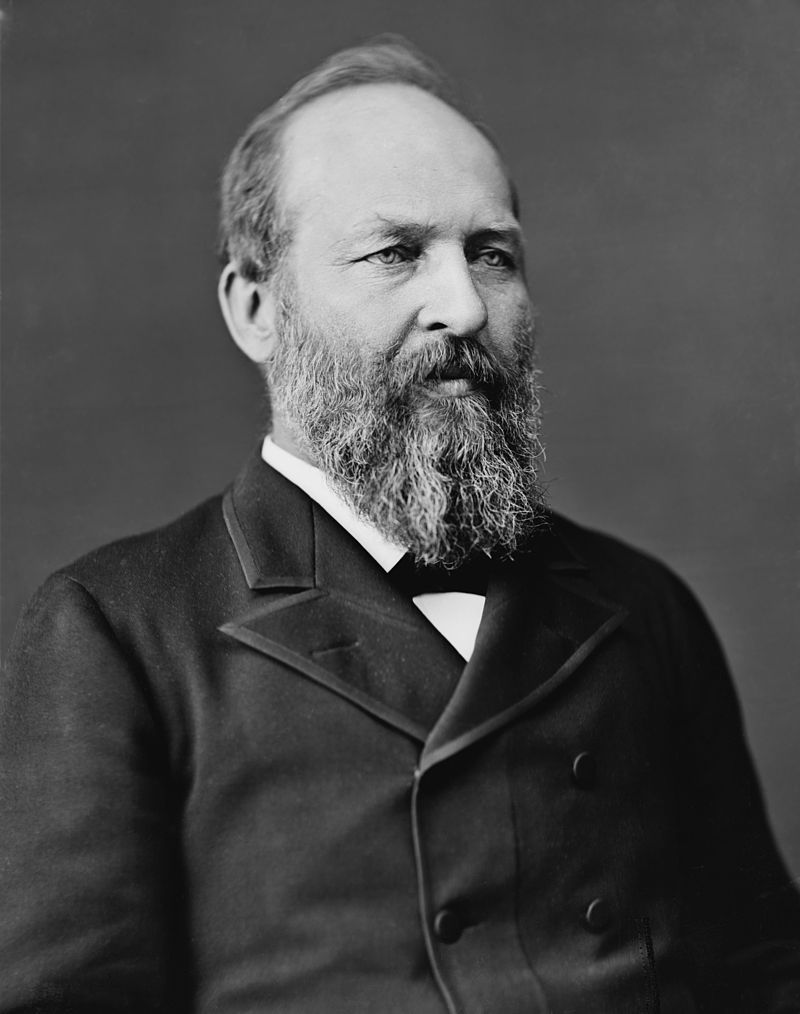

Garfield was actually an excellent

choice, hard-working, intelligent (once a college president), brave

(rose to the rank of brigadier general during the Civil War), and

politically experienced (having served in both houses of Congress).

Running against him as the Democratic Party nominee was the well-known

(but politically inexperienced) former Union General Winfield Scott

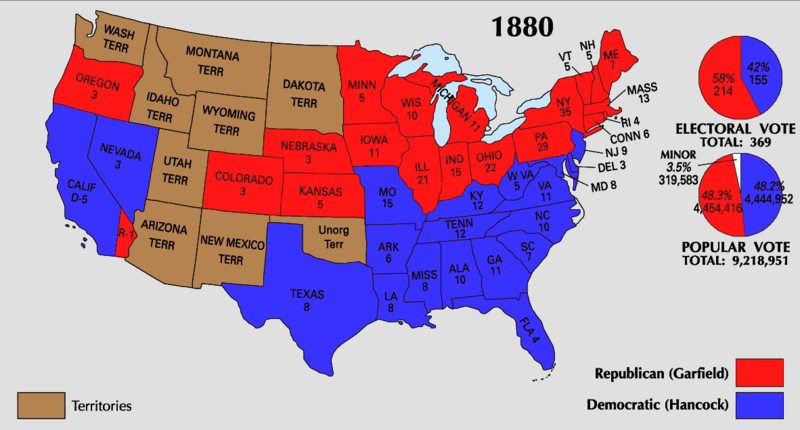

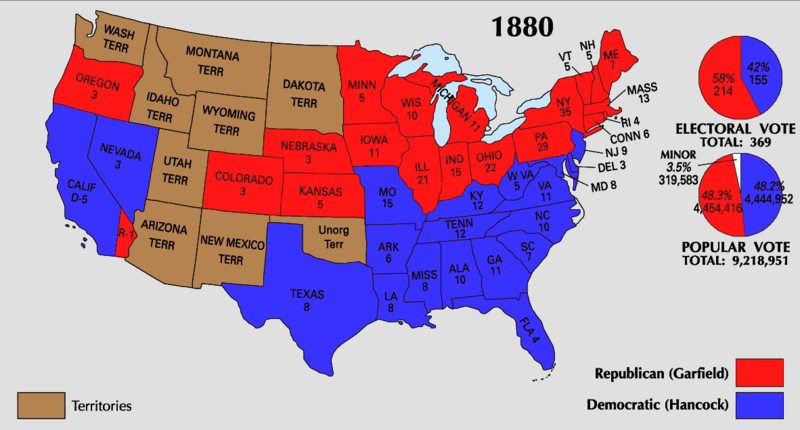

Hancock. The election was close, except again in the electoral college

where Garfield gained 214 votes to Hancock's 155.

Chester Arthur's vice-presidential

nomination had been the price paid to get Conkling's New York support.

But once in office, Garfield had other ideas about how much he owed

Conkling in patronage and worked hard to get truly qualified

individuals posted to government jobs. In the end, Conkling overplayed

his hand, and New Yorkers turned against Conkling.

But also in the end, it was this

patronage question that made Garfield's presidency short-lived. He was

in office only a few months when he was shot by an unhappy and mentally

unstable office seeker – and Garfield died 2½ months later of the wound

doctors were unable to heal (they could not find the bullet).

|

James A.

Garfield

|

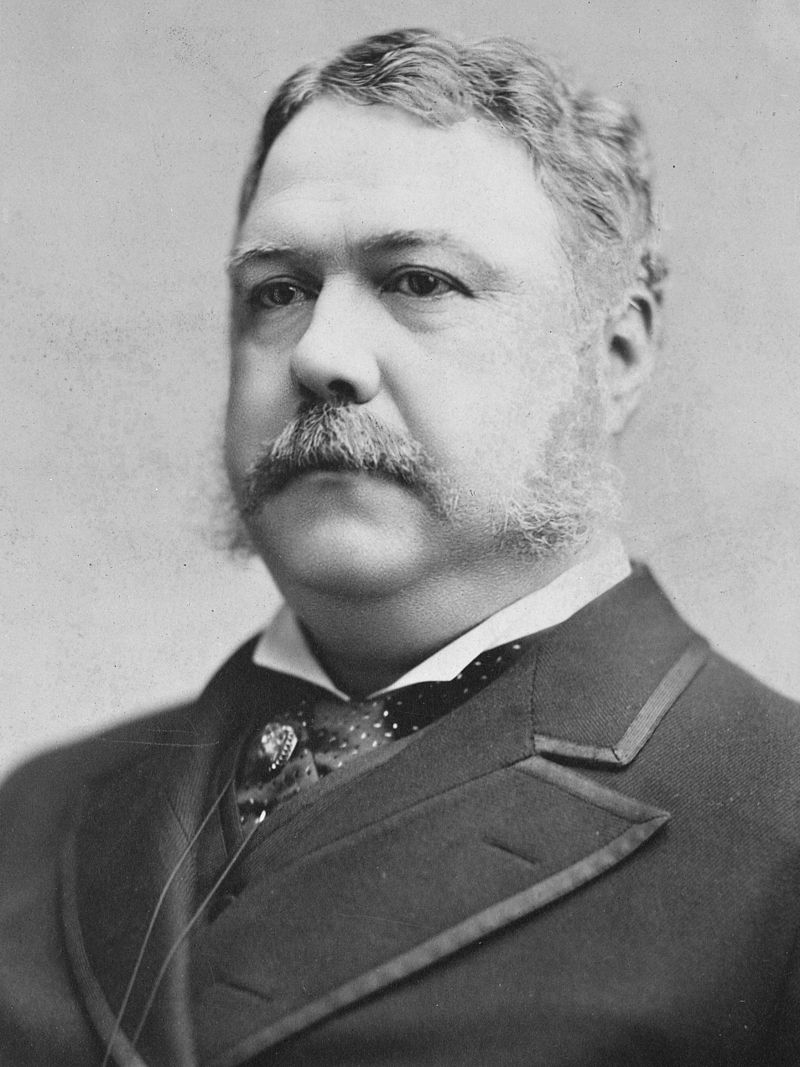

Actually, the man who had been dismissed from his

job at the New York customs house proved, in inheriting the office of

U.S. president, to be one of the country's leading anti-corruption

reformers. He personally vetoed bills coming out of Congress (most

importantly the Rivers and Harbors Act) that were merely opportunities

for more political patronage and financial corruption. He also signed

into law the 1883 Pendleton Act which turned an increasing number of

civil service appointments over to a Civil Service Commission charged

with the responsibility of filling government positions on the basis of

proven merit rather than political connections.

Finally gaining the deep respect that few at the outset of his

presidency ever would have expected, he nonetheless chose to retire

from politics after one term in office rather than run for re-election

(he was suffering from poor health).

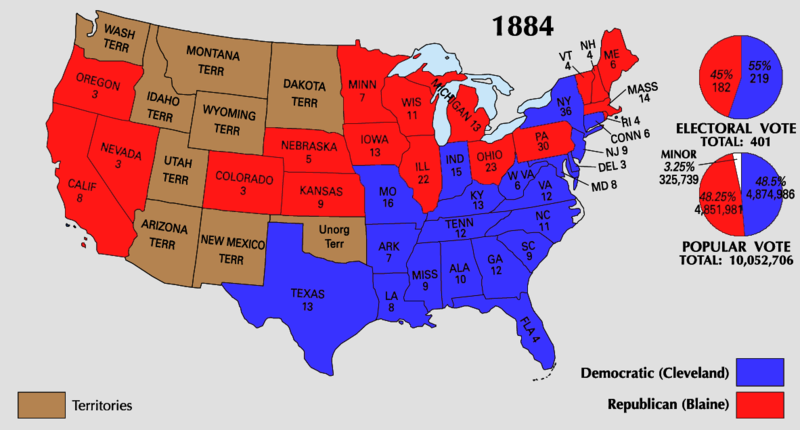

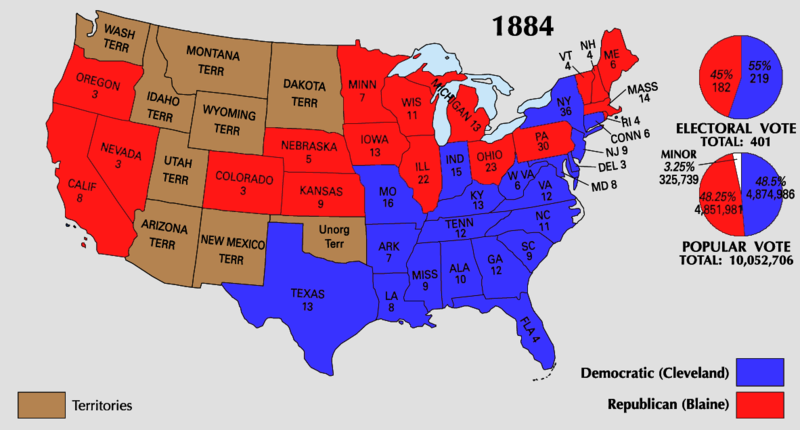

The 1884 election was fought largely over

the issue of personal integrity, the Republican candidate, James

Blaine, suffering from a well-known history of deep involvement in the

railroad industry spoils system and the Democrat candidate, Grover

Cleveland, on the other hand well-recognized for his incredible

integrity – except for the claim raised by opponents that the unmarried

Cleveland (but he would soon marry in the White House) had once

fathered a child out of wedlock.

The election was so very close that it

came down to the electoral vote of New York, in which the final tally

gave Cleveland a little over a thousand more votes than Blaine out of a

total of over a million votes cast in New York. Part of what ended this

long Republican control of the presidency was when a number of

reformist Republicans, the Mugwumps,2 cast their votes for the Democrat Cleveland because they viewed Blaine as being simply too corrupt.

2From

an old Algonquin term meaning "a person of importance," implying that

those who bolted from the party were being ridiculously sanctimonious

or morally condescending in refusing to support their party's

candidate, Blaine.

Chester Arthur

James Blaine

|

|

During his first term in office (1885-1889)

Cleveland faced the usual problem of filling government jobs with

personal appointments, a deep change in personnel usually accompanying

the election of a new president, especially if from a different party

than the previous president. But Cleveland announced that he would not

remove office holders because of their political affiliation, though he

did intend to reduce the size of a greatly inflated federal bureaucracy

(because of the spoils system). But eventually he bent to pressure from

fellow Democrats to replace some of the Republican officeholders with

Democrats, though he was even then restrained in doing so by comparison

to previous presidential administrations.

He also tackled the job of improving the

navy, by getting rid of inferior ships built by corrupt contractors. He

also had much of the railroad land in the West claimed by the

railroads, but undeveloped by them, returned to federal government

control. And being a limited-government supporter, he cut back on the

government's financial support of veterans and farmers that he felt

appeared more like spoils than compassion, and which he was certain

would merely set up a form of dependency on continuing government

bail-outs.

Another troubling (and persistent) issue

he faced was over this matter of the value of the national currency,

the U.S. dollar. The country was caught in deep controversy over the

matter of inflation, easy credit, and a cheap dollar – versus a tight

money policy. Logically speaking, it would seem that this was a matter

for the government's financial experts to handle. But after the Civil

War this issue had become a matter of almost religious dimensions, so

much had been printed and proclaimed on the subject. It had become a

matter of simple faith, especially among America's large farming and

industrial working-class sectors, that the road to happiness would be

easy credit and inflation: to gain higher wages at the workplace or to

be able to pay back a loan later in currency that was cheaper in value

than when the loan was first assumed. The best way to do that was

simply to have the government print dollars, lots of them. Industrial

owners and financiers however were very concerned about rising labor

costs and the relative loss of the value of their investments through

just such inflation and therefore they wanted dollars to remain

relatively scarce and thus of ever-greater value.

For most ordinary Americans, the monetary

theories involved in this matter were far too complex to follow, so

they used the symbols of silver and gold to represent their respective

positions. Gold was scarce, and the tight money people insisted that

each dollar printed be backed up in the nation's treasury by an

equivalent value of gold, and gold alone. Silver, on the other hand,

was considered to be abundant and ever-increasing through the

relatively easy possibility of more silver mining, and the easy-money

people demanded that instead of gold (or at least in addition to gold)

silver be the metallic basis for the nation's dollar supply.

So, silver versus gold became the hot

national issue, symbolizing the deeper antagonisms between the

industrial workers on the one hand and the business owners on the

other, between the much humbler American classes in rural America and

the growing numbers of up-East financiers – especially problematic if

they happened to be Jewish.

In short, gold and silver became the

rallying points in a growing class or social-cultural struggle tearing

at the nation. Of course these tensions had complex causes, but how

easy it was to sum it all up in the question of gold versus silver! And

it all made for great conspiracy theories so appealing to the people

who struggled to make sense of the difficult times they faced.

Like Grant before him, Cleveland was a

gold man. Cleveland responded by attempting to cut back on the silver

coinage which the government was required to mint under the

Bland-Allison Act of 1878. This cutback merely put Southerners and

Westerners and their representatives in Congress in a deeply angry

mood, inspiring Bland, author of the 1878 bill, to try to pass a new

bill in 1886 calling for the unlimited minting of silver currency. The

bill did not pass, but left a bitter issue unresolved.

Another issue Cleveland was forced to

tackle was the U.S. tariff. Cleveland strongly opposed the high tariffs

imposed on foreign goods in order to protect the pricing of goods

produced in America. The tariff revenues collected on imports by the

government were so high (about 47 percent of the value of the product

itself) that the government was actually registering an embarrassing

surplus in its operating budget. But in trying to reduce those tariffs,

Cleveland encountered stiff opposition from congressmen fearing that

American industry might be damaged badly if those tariff protections

were lowered. Thus he got nowhere on this issue.

|

Grover

Cleveland

|

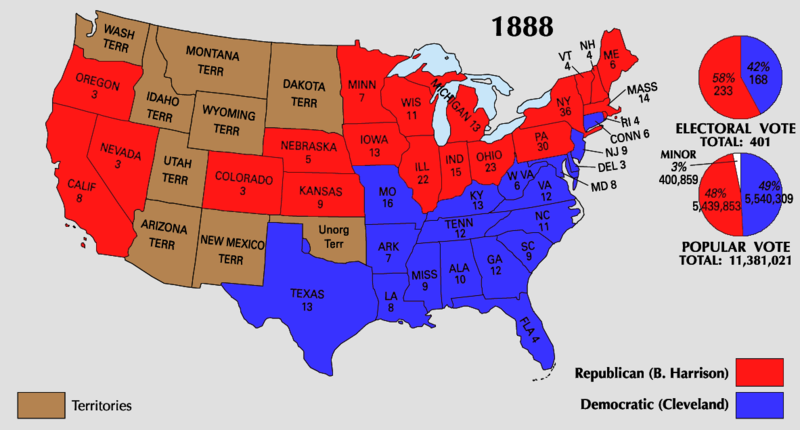

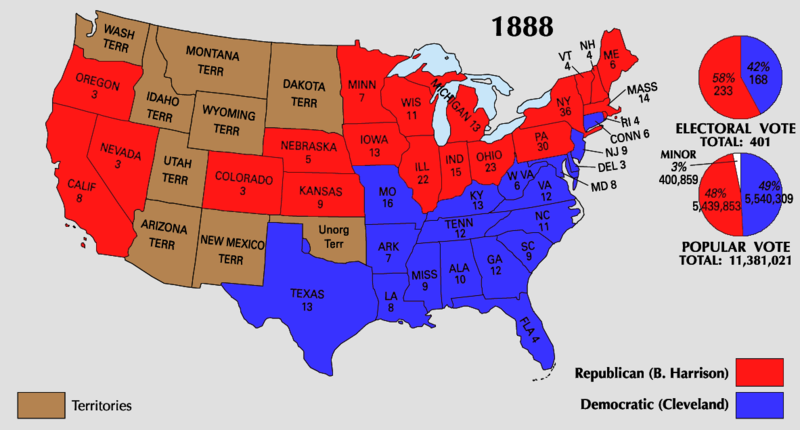

Benjamin Harrison wins the election of 1888

Although Cleveland won the popular vote in the

election, he lost the electoral vote and thus his bid for a second

term. A big part of his defeat occurred because of his position on the

tariff issue (he lost most of the northern industrial states). Also the

team of his Republican opponent, Benjamin Harrison, had conducted a

very aggressive (and somewhat questionable) campaign. Cleveland even

lost (narrowly) his home state of New York, because of the opposition

organized against him by Tammany Hall. If a mere 600 New York votes had

gone to Cleveland instead of Harrison it would have given Cleveland the

New York electoral vote (and the presidency), the voting being so close.

Harrison was the grandson of the Harrison

who served only briefly as U.S. president before dying from a cold

caught during his long inaugural address; grandson Benjamin's speech

was half the length, also conducted in the rain, under an umbrella held

by outgoing President Cleveland!

Harrison reversed Cleveland's course with

respect to the tariff and veteran pensions, but tried to emulate

Cleveland in appointing government personnel on the basis of proven

merit rather than mere political connections. But his idea of merit

tended to favor those of his home state of Indiana and his Presbyterian

church affiliation, to the anger of politicians from other parts and

religious convictions of the nation. And his generous pension payments

to Civil War veterans (regardless of the merit) merely opened the

opportunity for graft within the Pension Bureau, and a much-criticized

reduction in the federal surplus. And with the passage of the McKinley

Tariff, Congress went even further than Harrison wanted to go,

increasing the tariff even more, purposefully making some products

impossible to import.

In answer to the clamor of farmers and

miners, Harrison stood behind an Act sponsored by Senator John Sherman,

thus the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. Government purchase of

silver had long been a goal of the farming world, and to this was added

the voice of the mining world which was panicking because of the

oversupply of silver produced by the metal's easy availability. The

price of silver dropped away (making it even more attractive to debtors

as currency) putting the silver mining industry in a panic. Silverites

wanted full acceptance of silver as currency backing, at a fixed rate

(well above the actual market value of the metal). Sherman did not meet

the full expectations of the Silverites, but did commit the government

to a fixed amount of silver purchase, helping to keep the silver market

from collapsing and confirming the government's commitment to silver as

currency backing. This was not a good long-term solution to any problem

– and would ultimately serve as a major contributor to the Panic of

1893.

On the more positive side of the

political ledger during Harrison's presidency was the antitrust

legislation sponsored by the same Senator John Sherman (the Sherman

Antitrust Act as it has been known subsequently) which Harrison signed

into law in 1890. Actually, the motivation behind the law was

originally aimed as much at organized labor (labor unions) as it was at

the huge financial trusts that controlled a great deal of the American

rail, steel and financial industry.

Harrison also attempted to extend through the Justice Department

protection of the civil rights of Black Americans by prosecuting those

violating protective legislation already in place. But this effort was

stymied by the unwillingness of White juries to convict these

violators. Harrison's civil rights push for Blacks in other areas also

failed in the face of opposition which arose in both Congress and the

Supreme Court.

But towards the end of his presidential

term the economic picture of the nation was worsening (just ahead of

the Panic of 1893). Things were not looking good for his re-election.

Republicans had already lost seats in the 1890 elections and Harrison

was experiencing the loss of support by members of his own party (many

still upset over the lack of government appointments by Harrison). Also

American producers were awakening to the fact that the McKinley Tariff

was hurting themselves badly as consumers. As a consequence, though

re-nominated by the Republican Party, Harrison faced the national

election without the party support nor the popular enthusiasm needed to

retain the presidency.

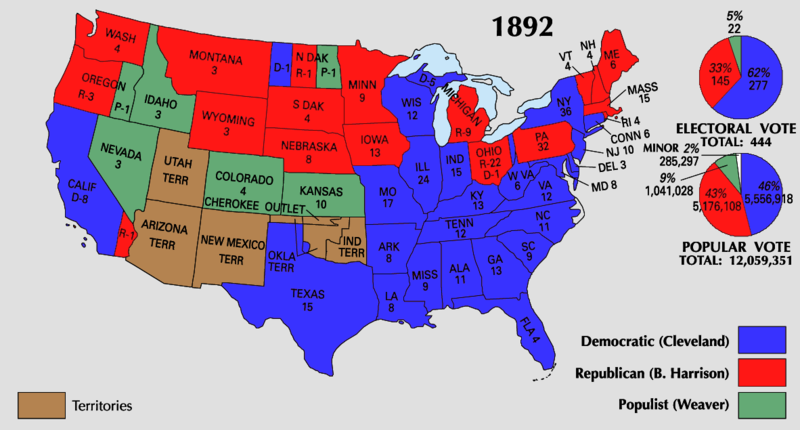

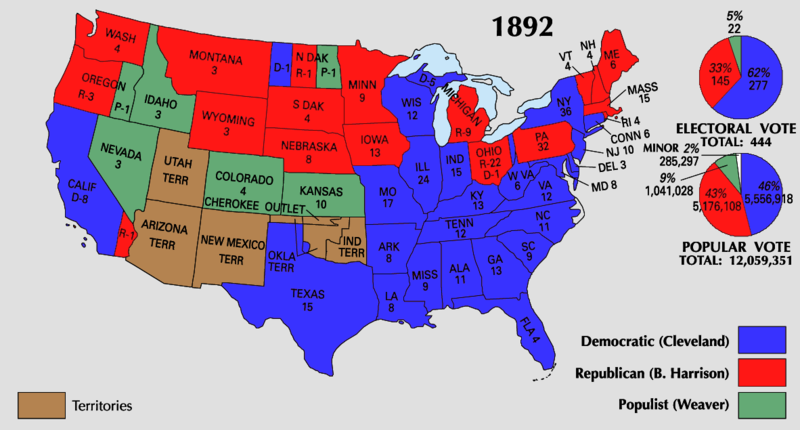

Harrison found himself facing his old

opponent, the Democrat and former President Grover Cleveland, replaying

the same issues as four years earlier. But unlike previous elections

this one would be clean, and quiet. In the end, the 1892 election would

prove to be a sad event for Harrison, not only in losing the election

rather decisively but also his wife to tuberculosis just two weeks

prior to the election itself.

|

Benjamin

Harrison

CLEVELAND'S SECOND TERM IN OFFICE (1893-1897) |

|

Cleveland returns to office just in time for the Panic of 1893!

A combination of bad economic news that hit at

about the same time (early 1893) caused a run on America's scarce gold

supply, leaving the federal treasury nearly out of gold and facing

financial default. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad had become too

ambitious and instead found itself in deep debt, so much so that just

before Cleveland was sworn into office in March of 1893 the railroad

company declared bankruptcy. This was combined with a huge drop in

wheat prices, a major international income earner for the nation.

Nervous investors, both at home and abroad, holding national and

corporate bonds began to demand banks, including the U.S. Treasury, to

exchange their bonds for gold. Seeing this trend, others jumped in

quickly, including the holders of silver coinage – which was greatly

overvalued because of the nation's huge silver production stimulated by

the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

Seeing the Sherman Silver Purchase Act as

part of the problem, Cleveland convinced Congress to repeal the Act,

ending the requirement of the government to purchase a fixed amount of

silver. This in turn caused the price of silver to drop drastically,

hurting people who held cash reserves in silver (which included a lot

of people!).

But Cleveland's action did not bring the Panic to an end. Businesses

and then banks began to fail, one after another as investors backed out

of the world of investment, or simply just failed as stock values

crashed.3 Soon

unemployment went from 3 percent in 1892 to nearly 12 percent in 1893,

to over 18 percent the following year, and then it hung at around the

14 percent figure for the next three years after that.

Labor unrest rocked the nation. In 1894

Ohio businessman Jacob Coxey led a march of unemployed workers on

Washington. Many dropped out along the way and the final demonstration

was fairly tame, though it certainly alerted the nation to the growing

discontent of the U.S. workforce. More violent was the Pullman Company

strike by workers (organized by the Socialist leader Eugene Debs)

demanding an end to the policy of low wages and the twelve-hour work

day. The strike quickly spread to other railway workers until by

mid-1894, 125 thousand of them were on strike, virtually shutting down

the U.S. rail network. Since the trains carried the mail, Cleveland

went after the strikers for violating federal law, resorting finally to

sending troops to various points across the nation to make his point.

Meanwhile, Cleveland's assault on the

silver market led the Populists (widely popular among American wheat

and cotton farmers) to claim that undercutting silver and trying to

rebuild the nation's gold holdings was simply an international

conspiracy – predominantly Jewish – designed to destroy the American

economy. However, at this point America was bleeding its gold reserves

badly, not rebuilding them.

Then the formidable J.P. Morgan proposed

to Cleveland that he would join with the Rothschild bankers of Paris to

sell the government 3.5 million ounces of gold (about $65 million in

value at the time) in exchange for thirty-year bonds. As previously

mentioned, at first U.S. President Cleveland turned down the offer but

finally in 1895 accepted Morgan's offer. Thus the U.S. Treasury was

spared default.

Cleveland's efforts to resolve the

complexities of the Panic seemed merely to undercut his standing with

the agrarian and labor wings of his Democratic Party, which suffered a

huge setback in the 1894 Congressional elections. Then when in the

summer of 1896 the Democratic Party gathered to nominate a presidential

candidate, Cleveland was faced by William Jennings Bryan, of the

strongly populist and Silverite wing of the party – a fiery orator who

roused the convention with his challenge, "you shall not crucify

mankind upon a cross of gold." Bryan was subsequently nominated by the

Democratic Party, and Cleveland went into political retirement at

Princeton, New Jersey (becoming a trustee of the university).

3Estimates are that 500 banks and 15 thousand businesses failed during the 1893-1898 years of the Panic.

"Coxey's Army" of unemployed -

1894

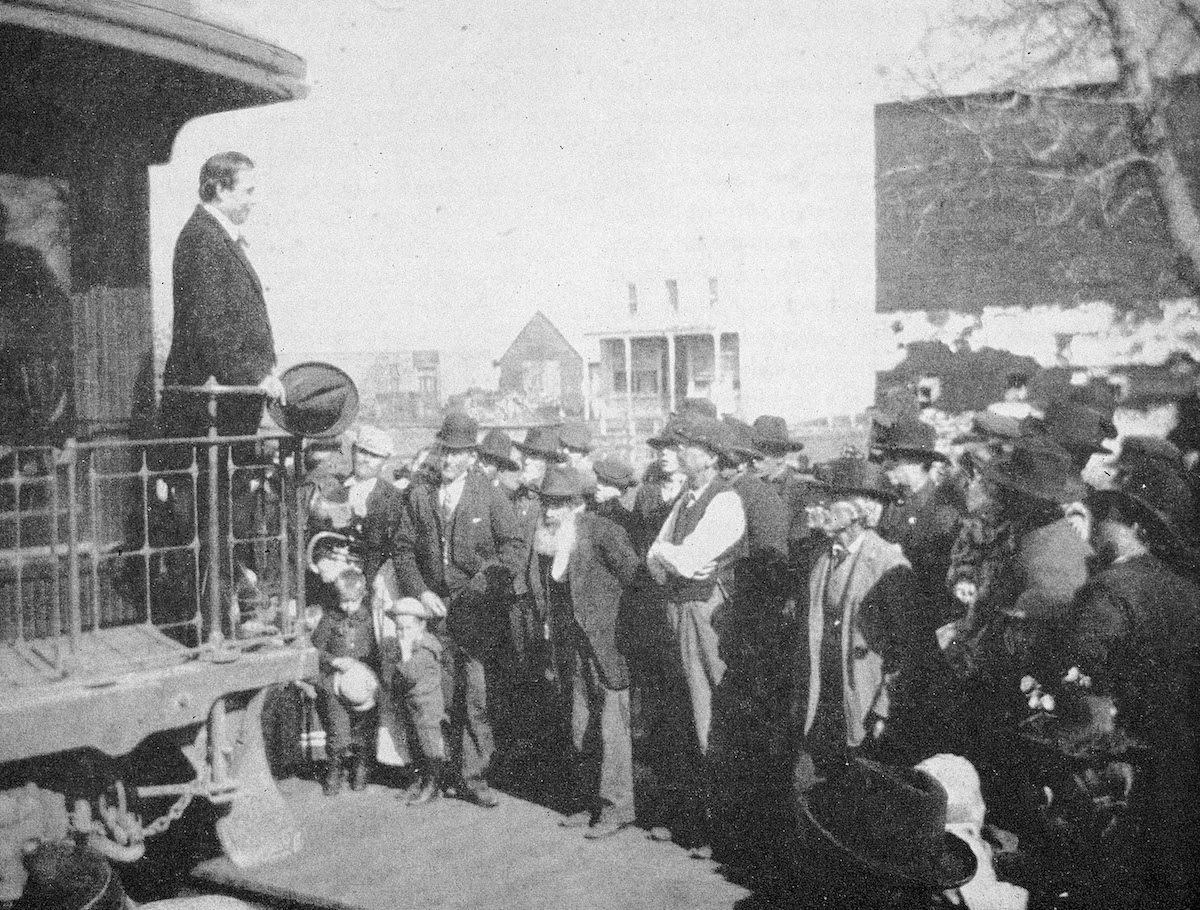

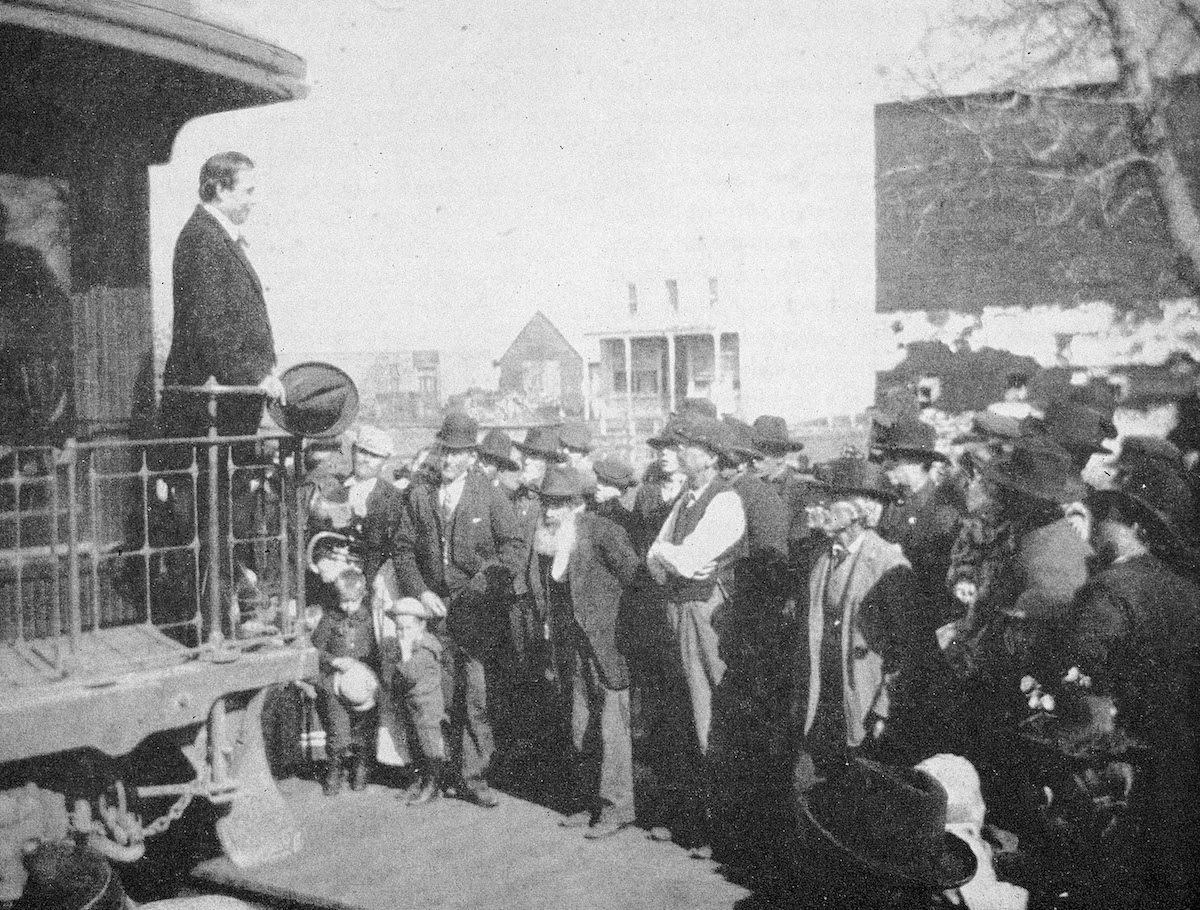

His political opponent, William Jennings

Bryan – speaking (c. 1896)

WILLIAM McKINLEY BRINGS THE 1800s TO A

CLOSE |

|

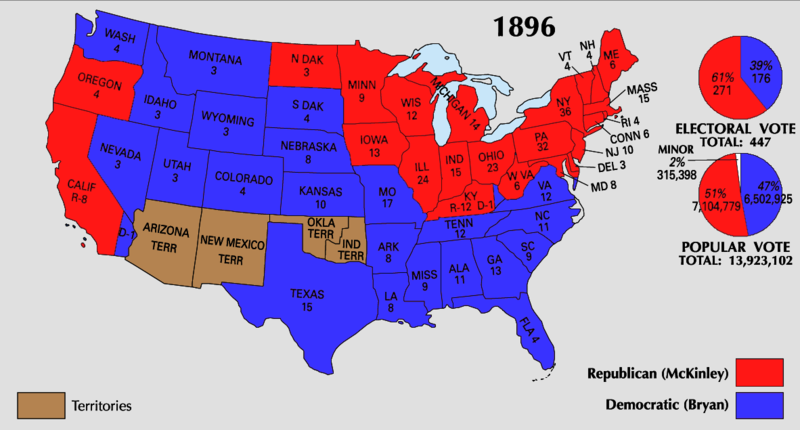

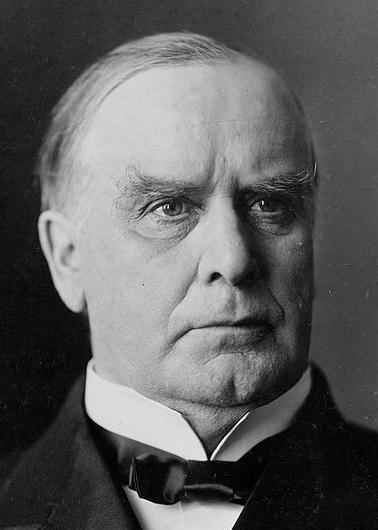

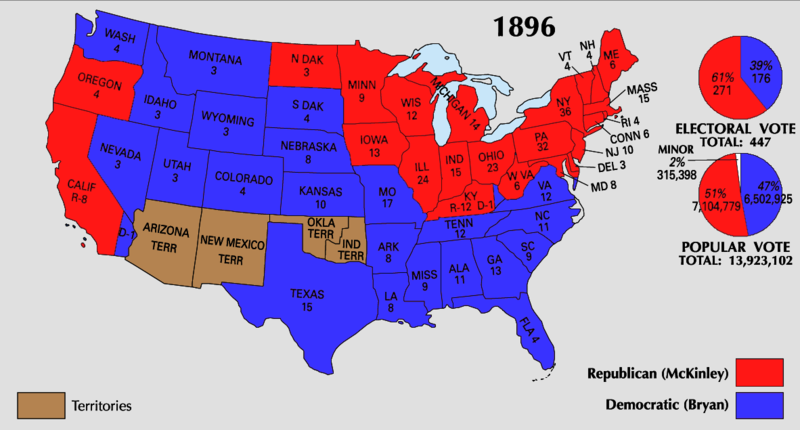

The victor in that election, the Republican candidate William McKinley,

represented the transition from the late 19th century governmental

minimalism and the governmental activism initiating the 20th century.

He was the last president to have served in the Civil War (starting as

a private but advancing to brevet major) and as president was an

unapologetic supporter of American imperialism, viewed at that time as

a natural part of the international responsibilities thrust on America

as a rising power. The victor in that election, the Republican candidate William McKinley,

represented the transition from the late 19th century governmental

minimalism and the governmental activism initiating the 20th century.

He was the last president to have served in the Civil War (starting as

a private but advancing to brevet major) and as president was an

unapologetic supporter of American imperialism, viewed at that time as

a natural part of the international responsibilities thrust on America

as a rising power.

He had been an Ohio lawyer elected in

1876 as a Republican representative to Congress where he sponsored the

McKinley Tariff protecting American industries from overseas

competition. He lost his seat in 1890 with the huge Democratic victory

of that year, but the next year he was elected Ohio governor and again

two years after that (1893). As governor he gained a reputation as a

skillful mediator between business and labor, and his very skillful

political campaigning for the Republican Party in 1892 and in 1894

brought much party attention to him as a possible future presidential

candidate.

His close friend Mark Hanna

skillfully worked those expectations into a reality at the 1896

convention where he was chosen as the Republican Party candidate to

come up against the Democratic Party candidate Bryan. The Democratic

Party was deeply divided over the gold-silver issue (as was also the

Republican Party – although to a lesser extent) which undercut severely

national support for the dynamic speaker Bryan, despite his strong

standing among midwestern farmers. Indeed, McKinley barely left his

front porch during the campaign and yet was able to gain a substantial

victory in the hotly contested November elections that year, largely

because Hanna had been as busy as the Democrats in issuing endless

publications, focused heavily on the gold-silver issue. Also with

McKinley's high tariff and pro-gold stance, he easily drew strong

support from the industrial East. His close friend Mark Hanna

skillfully worked those expectations into a reality at the 1896

convention where he was chosen as the Republican Party candidate to

come up against the Democratic Party candidate Bryan. The Democratic

Party was deeply divided over the gold-silver issue (as was also the

Republican Party – although to a lesser extent) which undercut severely

national support for the dynamic speaker Bryan, despite his strong

standing among midwestern farmers. Indeed, McKinley barely left his

front porch during the campaign and yet was able to gain a substantial

victory in the hotly contested November elections that year, largely

because Hanna had been as busy as the Democrats in issuing endless

publications, focused heavily on the gold-silver issue. Also with

McKinley's high tariff and pro-gold stance, he easily drew strong

support from the industrial East.

Protective tariffs and the gold standard

As president, McKinley made good on his

campaign promises, signing into law in 1897 the Dingley Tariff,

offering strong protection of American industry, and in 1900 the Gold

Standard Act, establishing gold as the sole standard in the redemption

of the dollar, making the dollar very strong, and expensive (the gold

standard was dropped in 1933 as one of the first acts of Roosevelt's

New Deal).

But it was in the area of foreign affairs

that the most notable feature of the McKinley presidency stands out.

America had long been taking a protective interest in the events

occurring to the South of the country in Latin America. But a rebellion

in Cuba by those seeking independence from Spain became a major

political issue in America when the uprising turned particularly

brutal. In 1898 McKinley led the nation to war against Spain,

eventually securing not only Cuban independence (under American

protection) but also full American possession of the former Spanish

colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. And on top of that,

it was during McKinley's presidency that America seized the Republic of

Hawaii as a new U.S. territory.

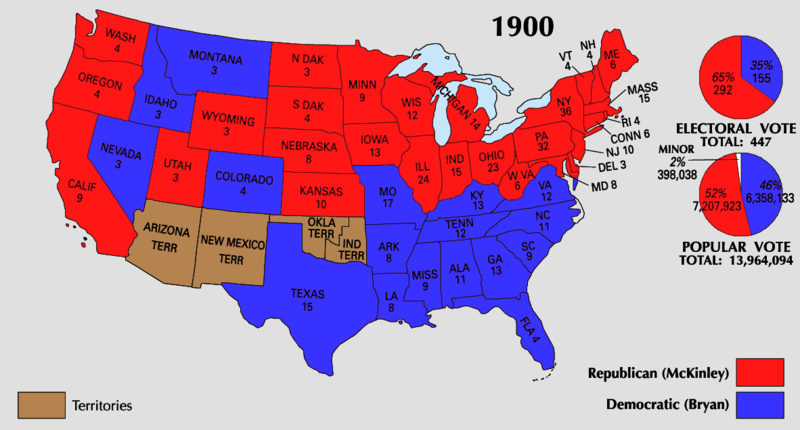

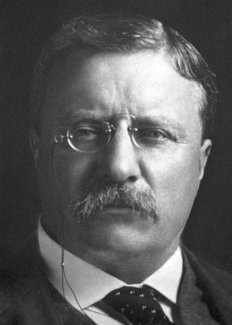

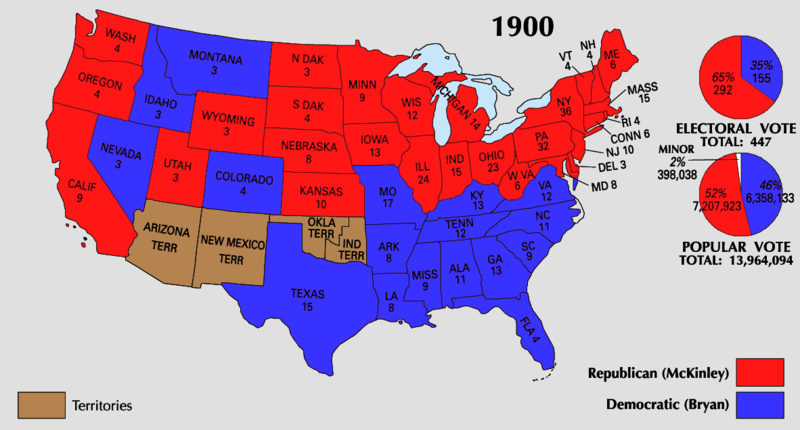

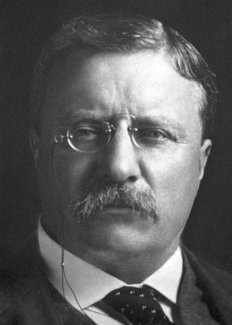

The

election of 1900. When the reelection campaign rolled around again in

1900, McKinley again found himself facing Bryan as his opponent.

McKinley's vice-presidential running mate ended up being New York's

governor, Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt,

put forward by New York's Republican Party boss Thomas Platt, who

promoted Roosevelt in order to remove him from New York politics! The

vice-presidential position was intended by Platt to shift Roosevelt to

a place of little significance. The

election of 1900. When the reelection campaign rolled around again in

1900, McKinley again found himself facing Bryan as his opponent.

McKinley's vice-presidential running mate ended up being New York's

governor, Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt,

put forward by New York's Republican Party boss Thomas Platt, who

promoted Roosevelt in order to remove him from New York politics! The

vice-presidential position was intended by Platt to shift Roosevelt to

a place of little significance.

Although the campaign might have appeared

as a replay of the 1896 election, America had changed greatly during

the four years of McKinley's first term. The nation was experiencing a

"Full Dinner Pail" as the Republicans termed the prosperity that the

nation was experiencing. Also American victory in the war with Spain

had American pride (and support for their president) running strong.

And Bryan's running on the silver platform now had none of the impact

that it did in 1896. Also his criticism of American imperialism under

McKinley lost him a lot of national support. Otherwise the campaign

style did not change much, Bryan on the road delivering endless

speeches and McKinley greeting visitors from his porch in Ohio.

And the results were again the same,

although McKinley registered a slightly larger majority of the votes

than in the previous election. Thus McKinley took office for a second

four-year term.

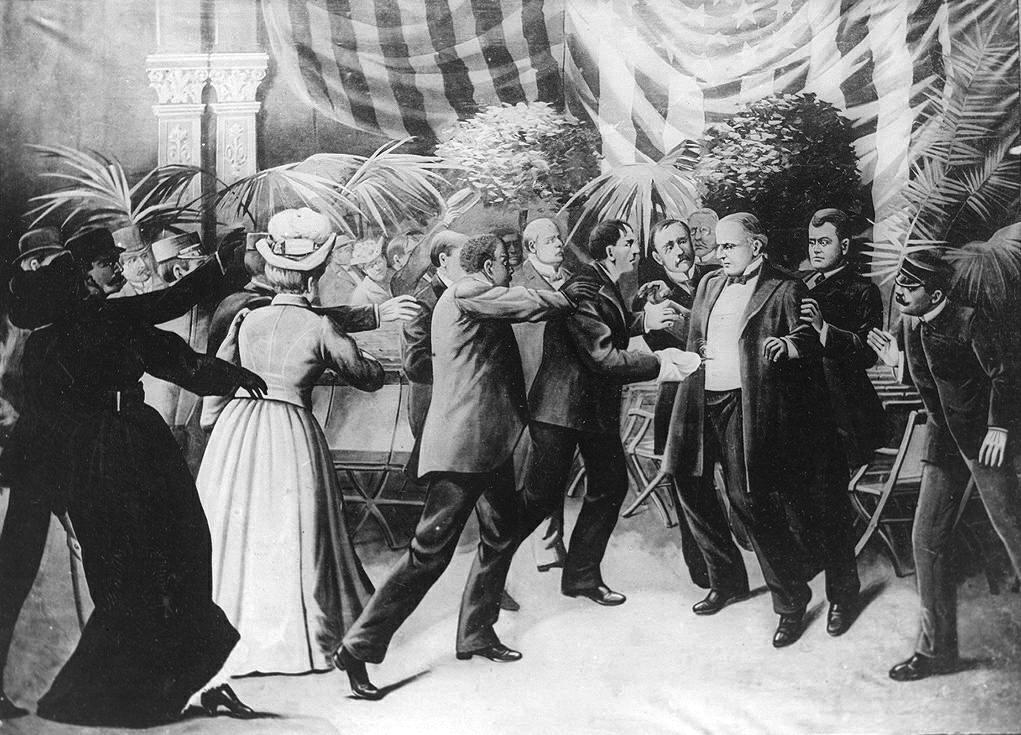

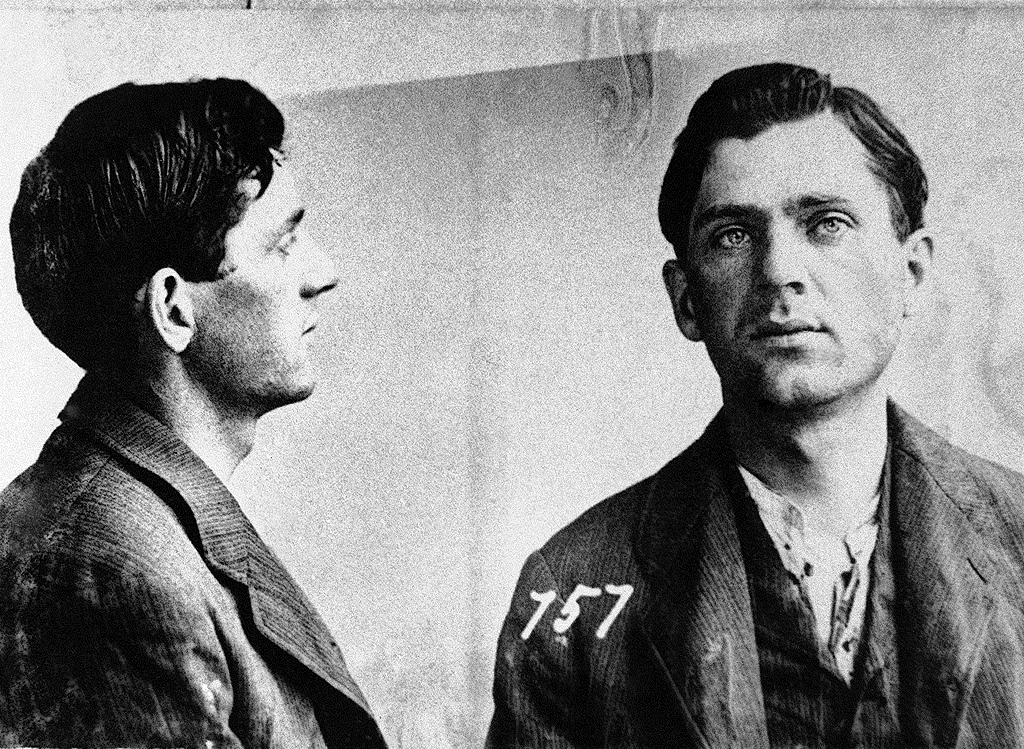

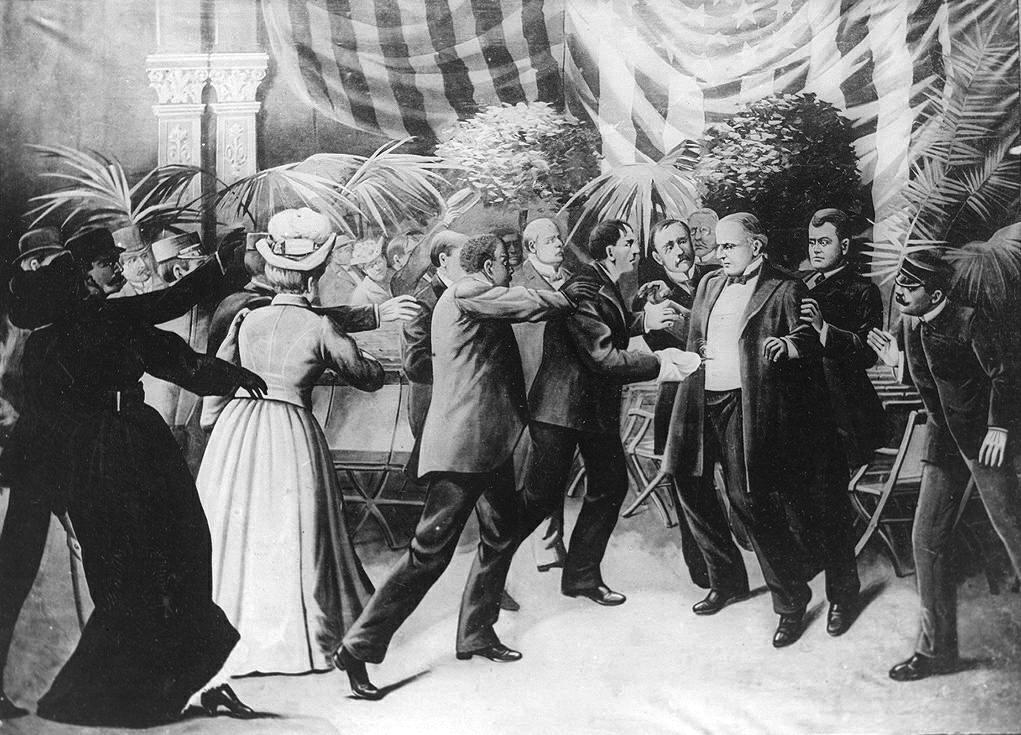

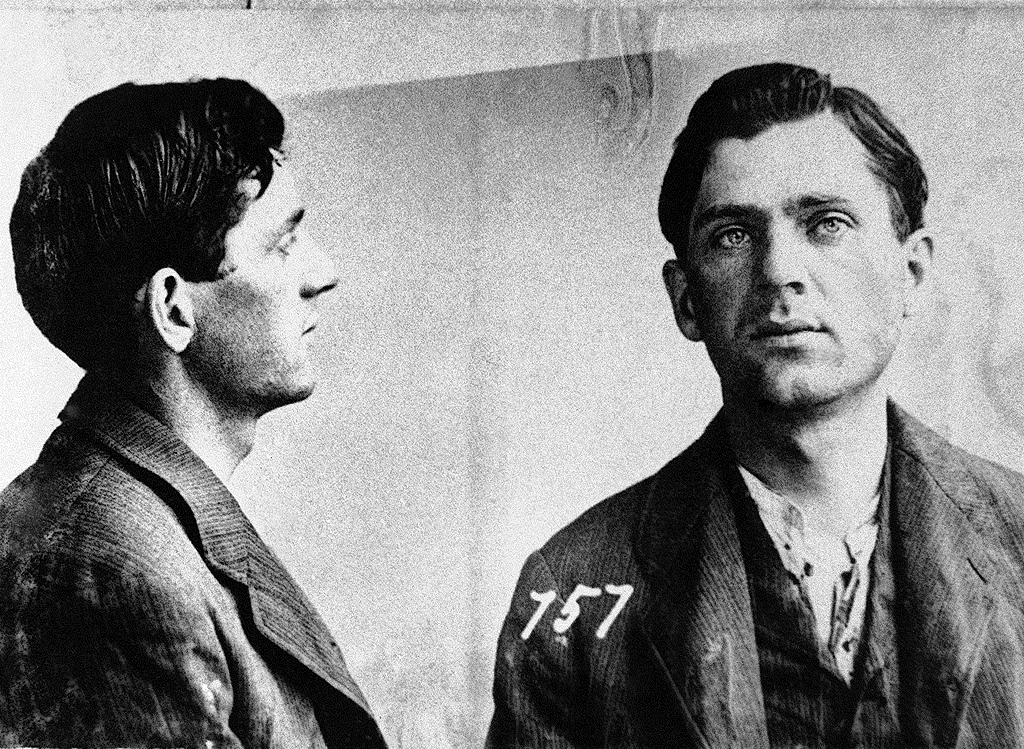

But McKinley was only six months into his

second term when he was shot in the stomach twice by a deranged

anarchist at a presidential reception at the Pan-American Exposition in

Buffalo, New York. A week and a half later he died of his wounds. The

insignificant Vice President Roosevelt was thus thrust into the office

as the nation's new president.

This would move the pace of political change started under McKinley even further, much further.

|

The McKinley and Hannah families

Hannah (left) dining with McKinley (right)

Bryan on the campaign trail

Assassination of William

McKinley - September 6th, 1901. Czolgosz shoots President McKinley with a concealed revolver at

the Pan-American Exposition reception. McKinley dies a week later.

His assassin – Leon Czolgosz

His assassin – Leon Czolgosz

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

Dealing with the "spoils system"

Dealing with the "spoils system"

The election of 1880 ... and Garfield's

The election of 1880 ... and Garfield's Cleveland's second term in office

Cleveland's second term in office

William McKinley brings the 19th century

William McKinley brings the 19th century

The victor in that election, the Republican candidate

The victor in that election, the Republican candidate  His close friend

His close friend  The

election of 1900. When the reelection campaign rolled around again in

1900, McKinley again found himself facing Bryan as his opponent.

McKinley's vice-presidential running mate ended up being New York's

governor,

The

election of 1900. When the reelection campaign rolled around again in

1900, McKinley again found himself facing Bryan as his opponent.

McKinley's vice-presidential running mate ended up being New York's

governor,