14. ATTEMPTS AT RECOVERY (THE 1920s)

POST-WAR PEACE

CONTENTS

The brutal reality facing a post-war The brutal reality facing a post-war

Europe

Nationalism versus internationalism Nationalism versus internationalism

The Russian Civil War (1917-1922) The Russian Civil War (1917-1922)

The German Weimar Republic The German Weimar Republic

The post-war treaties The post-war treaties

The League of Nations The League of Nations

The Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921) The Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921)

The Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) The Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 97-108.

THE BRUTAL REALITY FACING A POST-WAR EUROPE |

Ypres, Belgium, after the

Battle of the Lys

Ypres, Belgium, at War's

end - 1919

Ypres, Belgium, at War's

end - 1919

Passchendael - before and

after the War

Passchendael - before and

after the War

Imperial War

Museum

The Town Square, Arras, France.

February, 1919.

National Archives

NATIONALISM VERSUS INTERNATIONALISM |

Four

empires – Russian, German, Austrian and Turkish – had completely

disappeared because of the four-year bloodletting. And what

replaced them was hardly an immediate advance forward in peace and

prosperity of the nations involved. Chaos, not peace and

prosperity under new progressive governments, was what greeted the

people with the loss of their former autocratic governments.

As

for the League of Nations ... it had virtually no impact on the way any

of these major crises played out. As a protector of the

international peace it proved itself to be completely useless.

Almost all of what developed did so as a matter of direct intervention

by a number of national powers who conducted their diplomacy in

accordance with their own respective national interests.

This would be a sign of things to come. Maybe it will always be

this way, despite the dreams of those who still look for some kind of

transcending principle or organization that they believe might finally

act in service to a higher sense of international order.

|

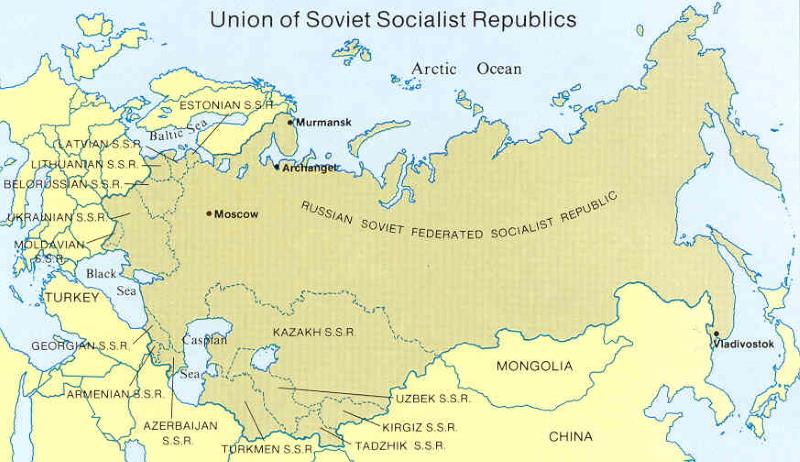

The Russian Civil War (1917-1922)

The worst case of post-war choas was that of Russia, which fell into a four-year civil

war that destroyed more Russian life than had the European war

itself. Armies of Whites (a scattered coalition of supporters of

Kerensky’s Provisional Government, tsarists, Cossacks and an array of

various conservative groups) and Reds (Lenin and Trotsky’s Bolsheviks)

ranged back and forth across Russia, pillaging, slaughtering, and

burning farms and villages as they went, leaving behind pure desolation

as they passed through to another battle with their enemies. Also

involved were a number of foreign armies (British, American, Czech,

Japanese) sent to Russia to support the Whites in the hope of keeping

Russia in the war ... but who stayed on even after the war was over to

continue that support. Sadly, this participation of the foreign

troops on the side of the Whites gave the war the appearance among

Russians of the Bolsheviks fighting for the national rights of Russia

against the efforts of Whites to put Russia under foreign rule.

Adding to the confusion, a number of non-Russian national groups within

the Russian Empire saws this as an opportunity to break free from

Russian domination and establish national independence for themselves

(opening up local political contests among themselves in the

process). Thus the Russian Empire collapsed into a state of

bloody chaos.

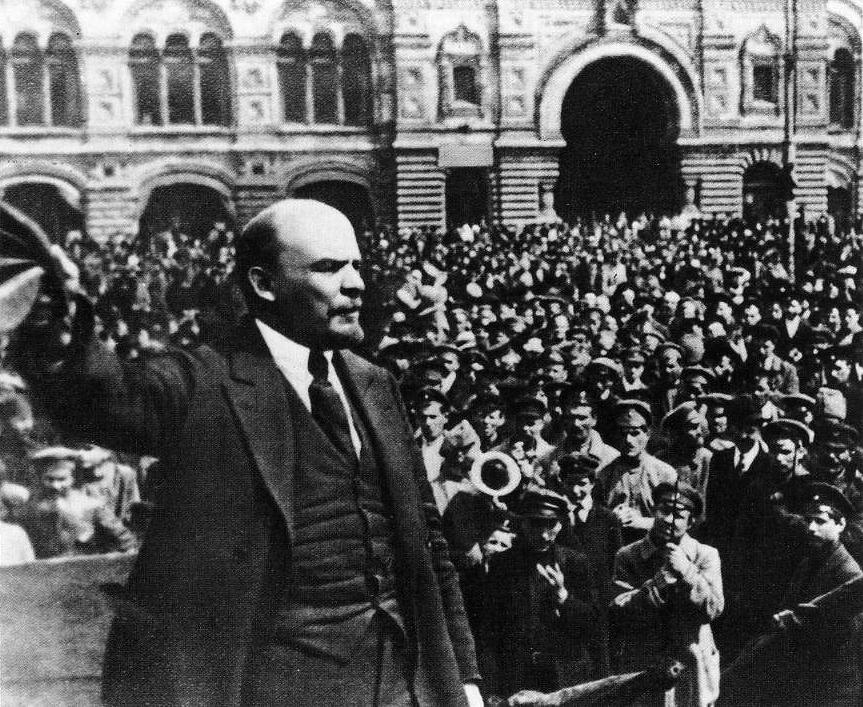

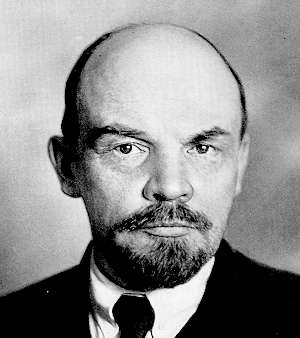

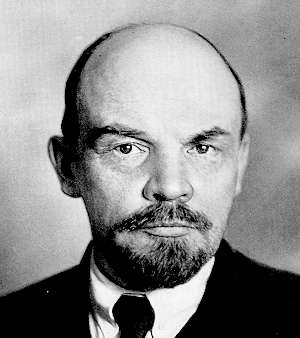

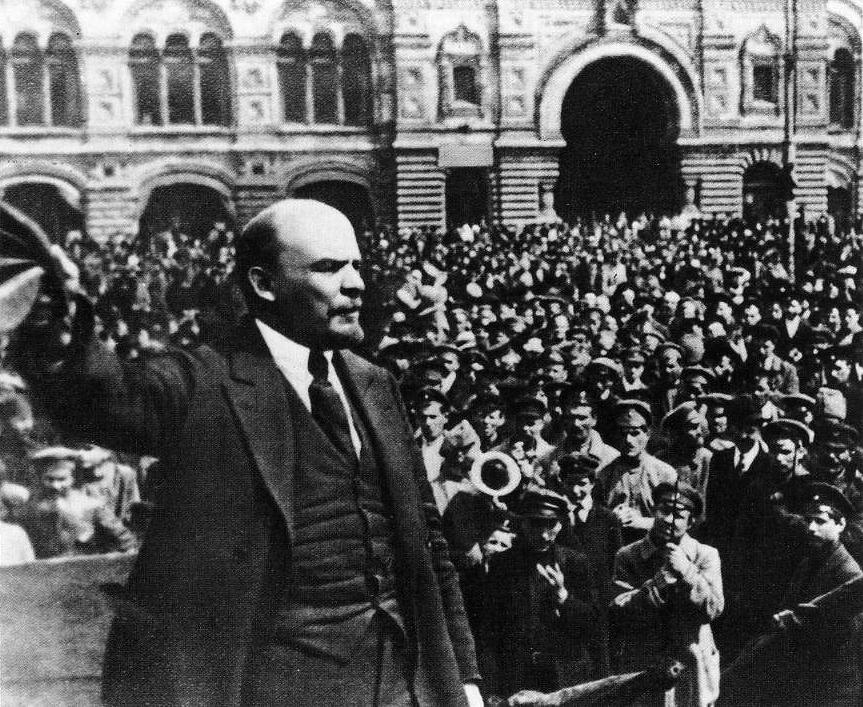

Lenin Lenin |

Lenin addressing a crowd

in newly renamed "Red Square" Moscow - 1919

Lenin addressing a crowd

in newly renamed "Red Square" Moscow - 1919

William Manchester, The

Last Lion: Winston Churchill, Visions of Glory, (Boston: Little, Brown

& Co., 1983), p. 678.

William Manchester, The

Last Lion: Winston Churchill, Visions of Glory, (Boston: Little, Brown

& Co., 1983), p. 678.

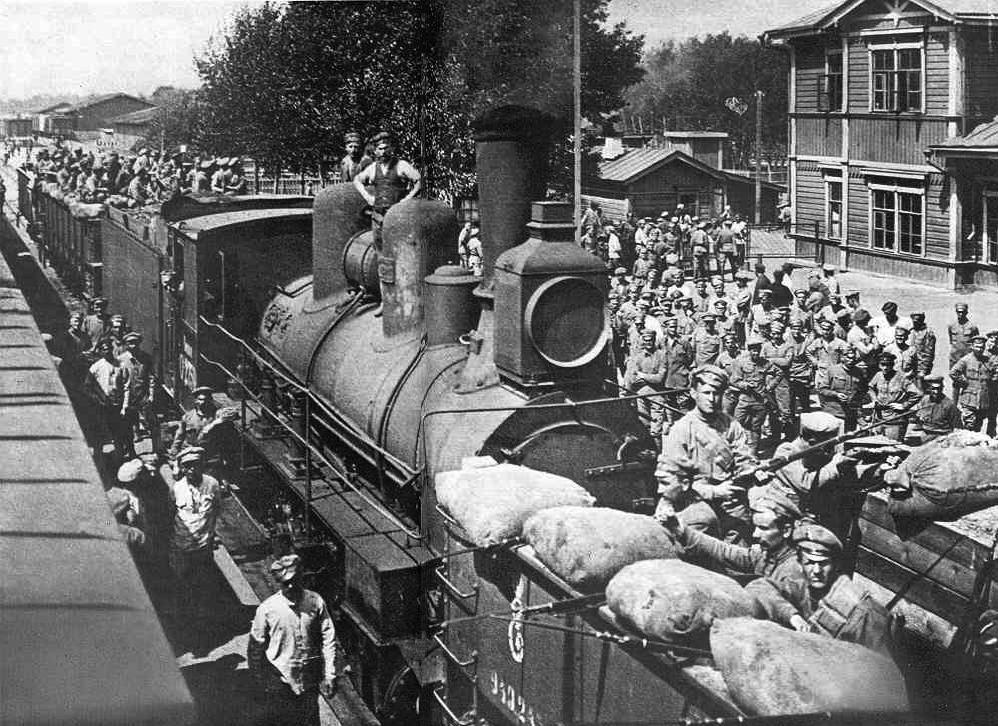

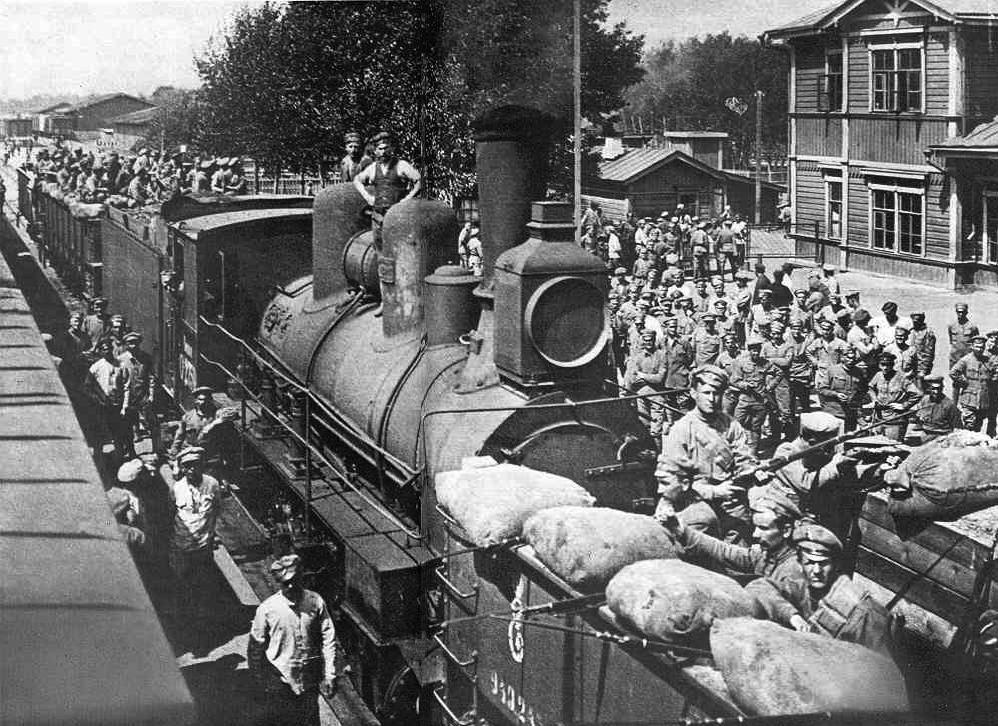

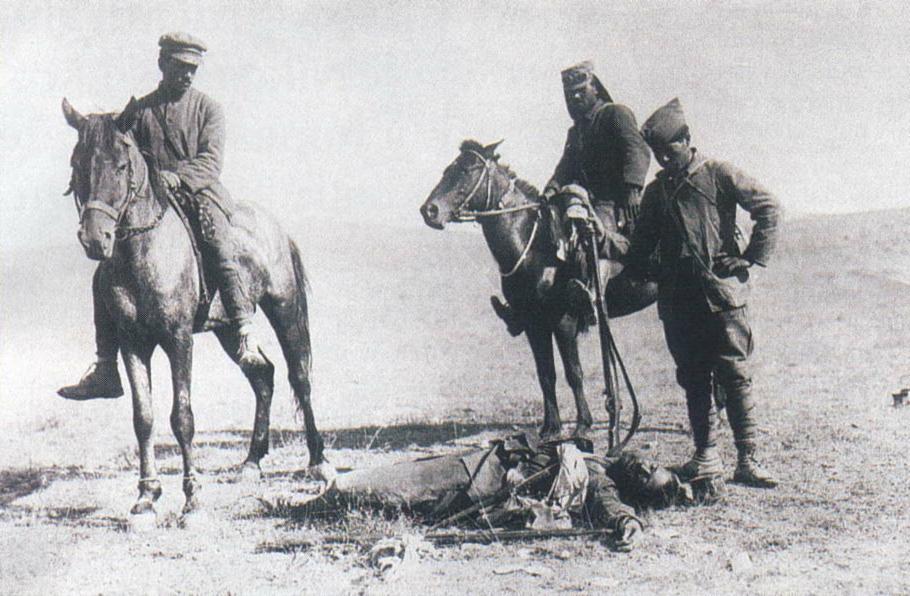

Red troops advancing against

the Whites in the Crimea - late 1919

Russian White soldiers standing

over the bodies of dead Bolsheviks or Reds – 1919

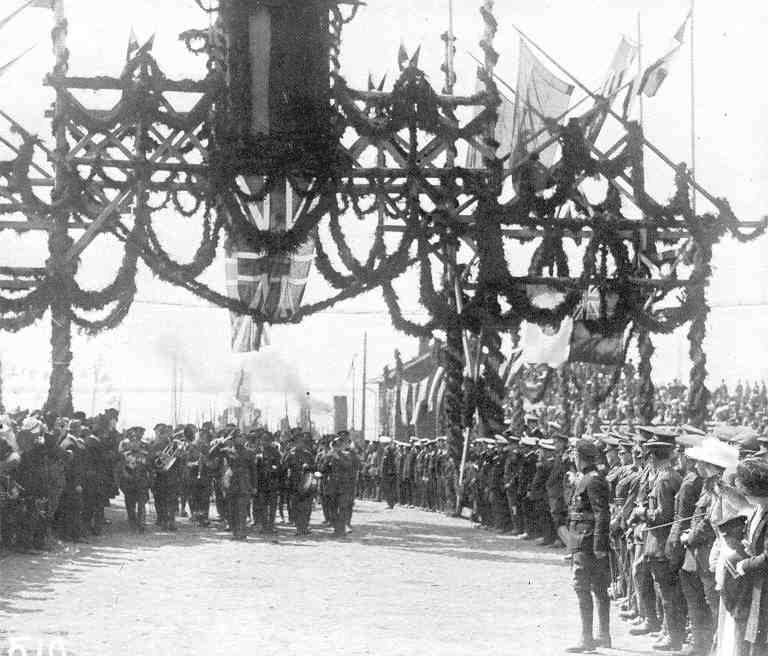

American troops in Arkangelsk – aiding the resupply of the White army.

American troops in Arkangelsk – aiding the resupply of the White army.

American soldier ladling

out soup to a Russian prisoner in Archangel

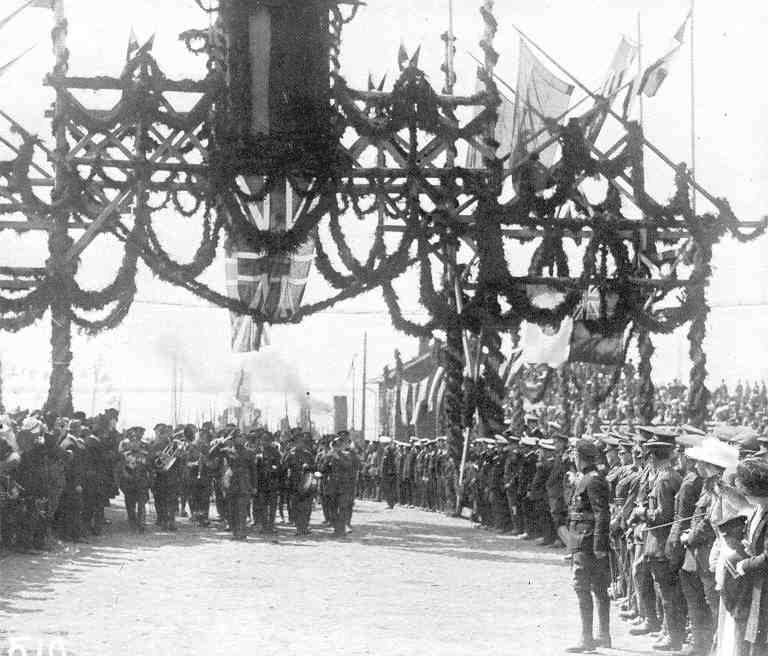

American troops in Vladivostok

on parade. Japanese marines are standing

to attention

as they march by. Siberia, August 1918

17 U.S. dead being brought

out of Romonofska, Siberia

British troops arriving in

Arkangelsk to replace the American troops who will be going home – early

1919.

British troops arriving in

Arkangelsk to replace the American troops who will be going home – early

1919.

The Czech legion as it is

about to embark across Siberia in the hope of getting home – by sea.

Lenin's call to arms in Moscow

against invading Poles – May 5, 1920

Anti-Bolshevik Japanese troops

in Vladivostok during the Russian Civil War – 1921

Anti-Bolshevik Japanese troops

in Vladivostok during the Russian Civil War – 1921

National Archives

|

Lenin's move to secure his Soviet social order

In the meantime, Lenin set about immediately to put into force a social

strategy he had worked out well beforehand. He decreed the

transfer of the large landholdings (including lands belonging to the

church) to the peasants who actually worked the farms ... not only

winning the hearts of the peasants, but stirring fear in their hearts

that if the Whites were to win the civil war the peasants would lose

title to their lands. Lenin also moved quickly to put large

industries under Bolshevik control, although workers’ committees were

set up to give the industrial workers a sense of ownership of the

production of these industries ... again, to win the loyalties of the

Russian working classes. Lenin also set up a bureaucracy of

Bolshevik agents who were sent out in the country to monitor these

changes. And finally, Trotsky was assigned the task of

professionalizing the Bolshevik army (the Red Army), reshaping it

quickly as an effective fighting force designed to protect the rights

of the common people against the former ruling classes ... a task in

which Trotsky succeeded brilliantly.

Lenin also moved quickly and ruthlessly to eliminate all members of the

social classes (the nobility and the bourgeoisie or middle class that

had not yet fled Russia) most likely to oppose his revolution.

Even peasants considered to be suspicious of anti-revolutionary

loyalties were executed or exiled to Siberia. All political

parties other than the Bolsheviks were outlawed and the Russian press

was brought into conformity with the Bolshevik revolution ... or shut

down completely. The Cheka, a secret police (modeled after the

Tsarist secret police), was created to remove outspoken opponents of

the new regime.1 And finally, on July 18, 1918, the Tsar and his

family were executed out of fear that they might fall into the hands of

an advancing White army.

The Orthodox Church and the Christian faith also became objects of

Lenin’s social revolution. The church had long been supporters of

the Russian autocracy and thus according to Lenin’s logic needed to be

destroyed. But he was also opposed to the Christian faith itself,

held dearly in the hearts of most Russians, for he feared that it

harbored conservative attitudes that would stand in the way of the

cultivation of a revolutionary conscience among the new class of

proletarian comrades foundational to Lenin’s rising social order.

Ultimately, little by little Trotsky’s Red Army was able to gain ground

against the less well-organized White Armies. Kolchak’s White

army, at first successful in Siberia, was finally defeated by the Reds,

as was a coalition of Whites in Ukraine (1919-1920). Remnants

held out in the south until finally driven out of Crimea in late

1920. In October of 1922 the Reds were able to secure all of

Siberia when the Japanese pulled out of the far eastern region and the

last White army in Siberia at Vladivostok surrendered. From

that point on only small scattered groups of Whites continued the

struggle. Thus Lenin had finally secured his Soviet state.

But things were not going quite as well for Lenin as he had hoped for

in those first years of the establishment of the Soviet state.

The economic disruption of the civil war was immense. Industrial

production dropped to one-fifth the level it had stood at in 1913

before the European war. Towns were deserted as workers fled to

the countryside in the search for food. Even production on the

farms was less than half what it had been before the war. There

was no stable currency the farmers could count on or even manufactured

good they might want to buy, so most farmers reduced their food

production to levels sufficient merely to feed their own

families. By 1920 widespread malnourishment and disease was

rampant in the country, claiming hundreds of thousands of lives.

1Since

opponents of Lenin’s regime were arrested secretly (usually in the

middle of the night) no numbers were kept of the people "liquidated"

(usually killed directly) by the Cheka. Estimates vary from 50

thousand to hundreds of thousands. So bad was its reputation that

in 1921 its name was changed to the Government Political Office (GPU)

... as if a name change might improve the reputation of the Leninist

regime.

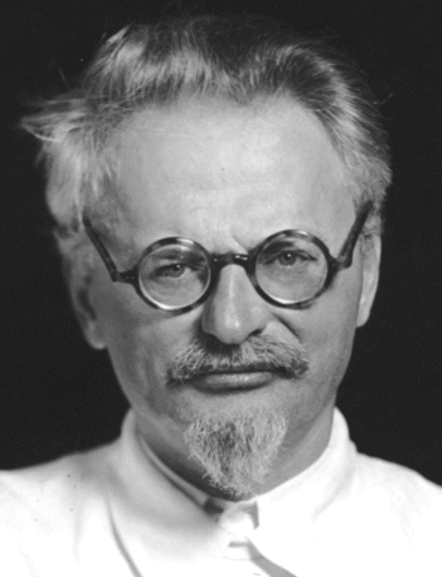

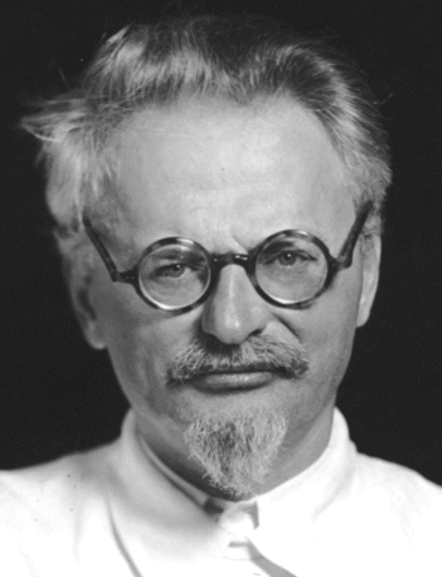

Leon Trotsky in

1921

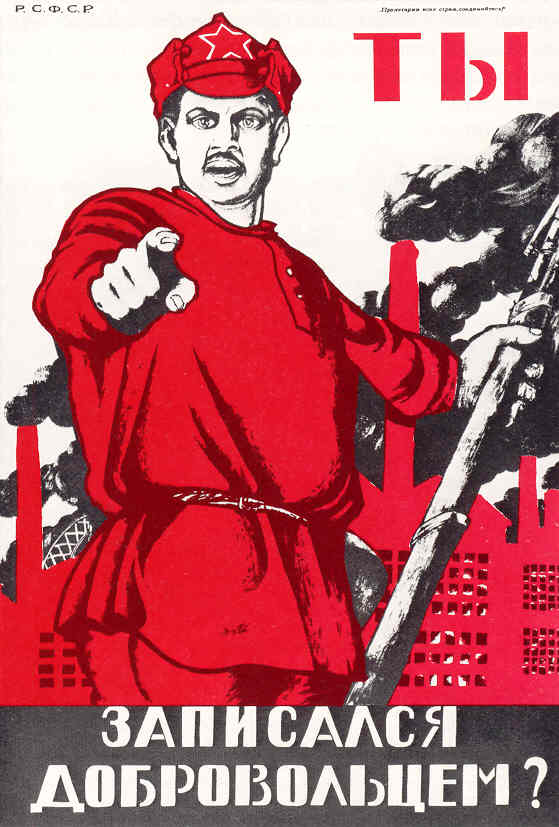

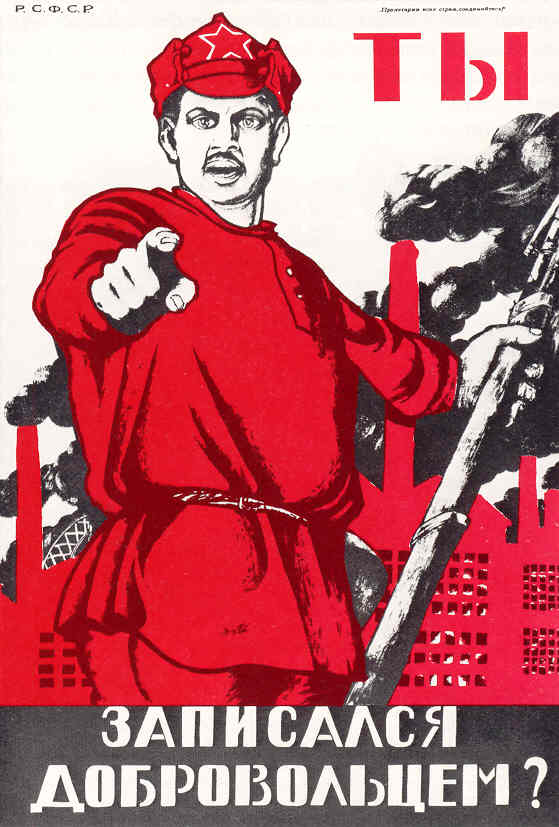

A Red Army recruiting

poster

A Red Army recruiting

poster

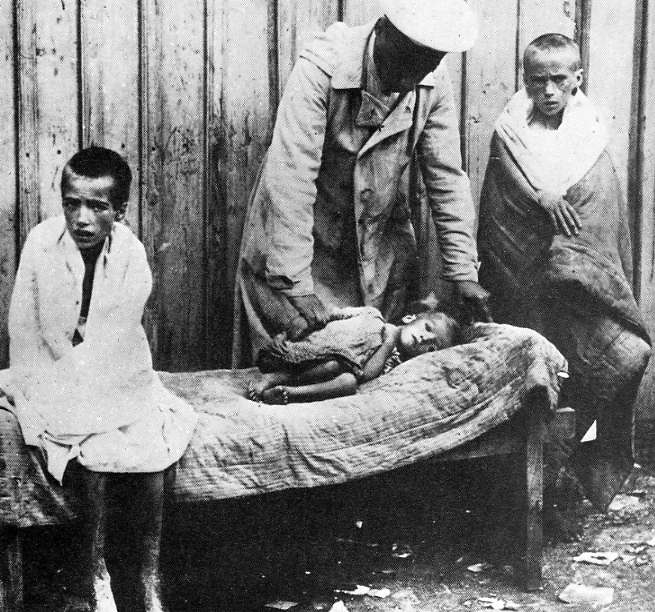

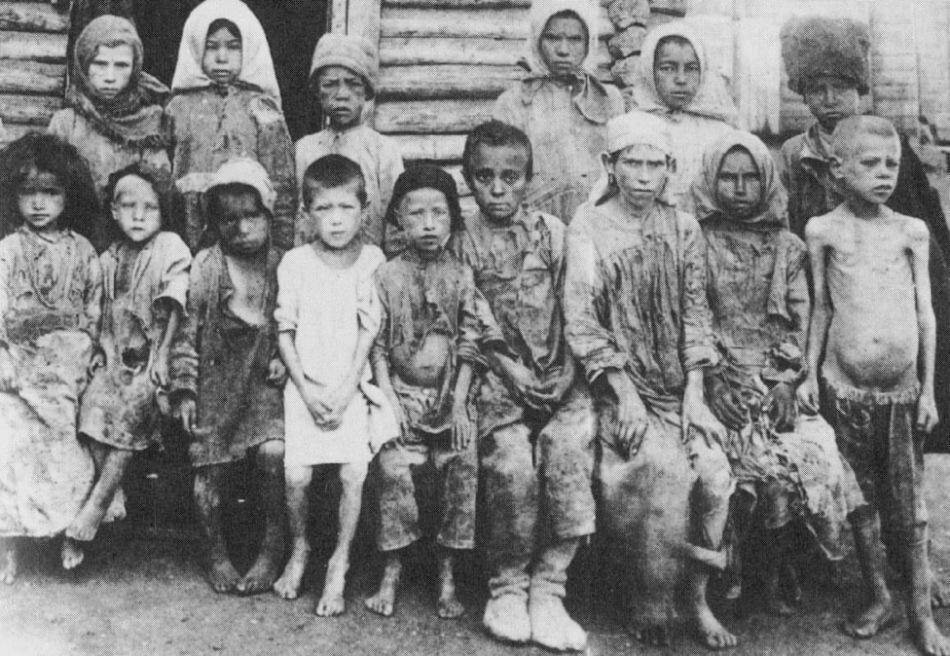

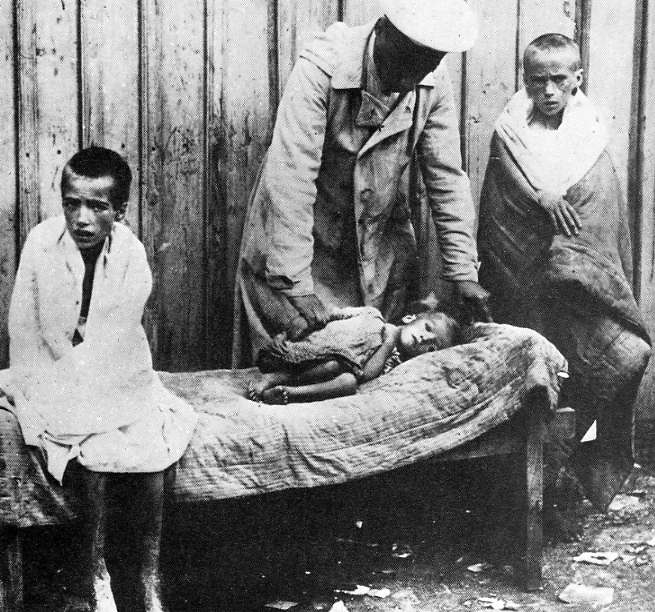

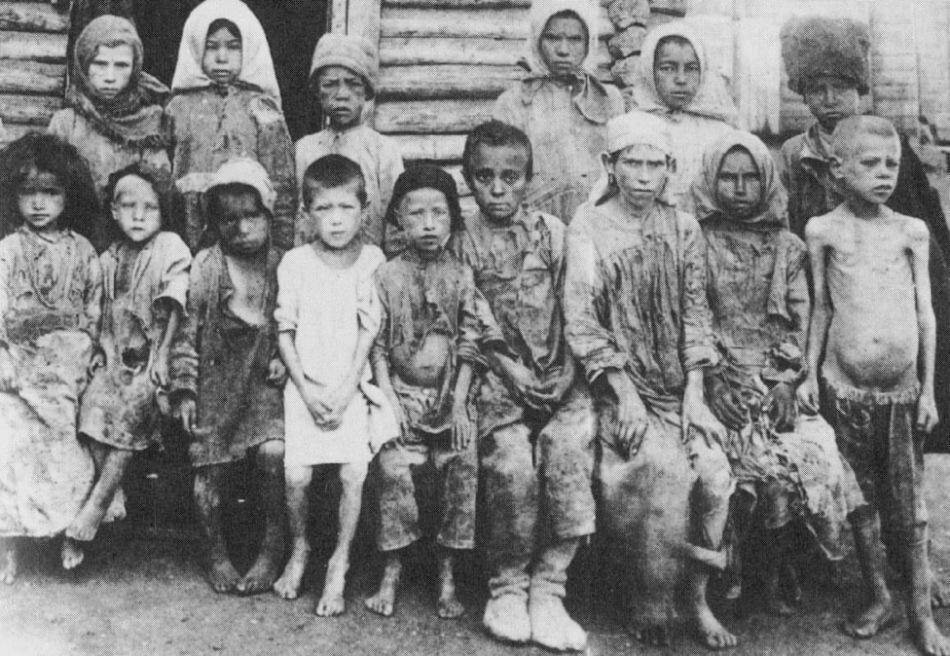

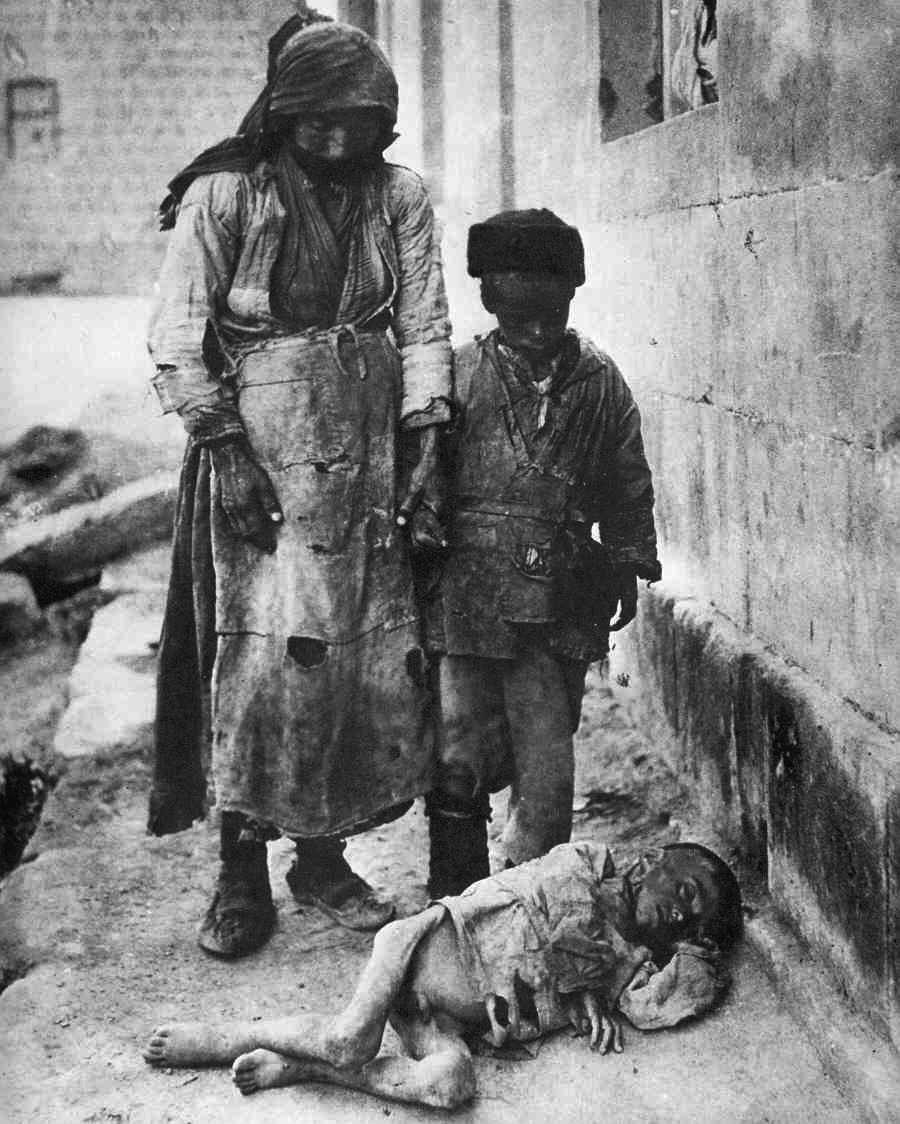

Starving children in

Russia

Starving children in

Russia

In the five years of the

Russian

civil war 15 million people lost their lives

- most of them hapless civilians.

Starving Russians during

the drought of 1921

Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP)

By 1921 Lenin was ready to try another approach to industrial and

agricultural production. He came up with a plan termed the New

Economic Policy (NEP) which opened up the economy to the development of

small private enterprises and private trading beyond the official state

program. He put the rouble back into operation in order to

facilitate that trade. He established a standard agricultural tax

rather than the state requisitions of food products as payment to the

state. He did maintain the state monopoly on the major industries

however. Yet slowly the economy started signs of growth under the

NEP, especially in the realm of agriculture where the revival was

fairly quick. Even in the industrial sector, Russia was back up

to 1913 production levels by 1927.

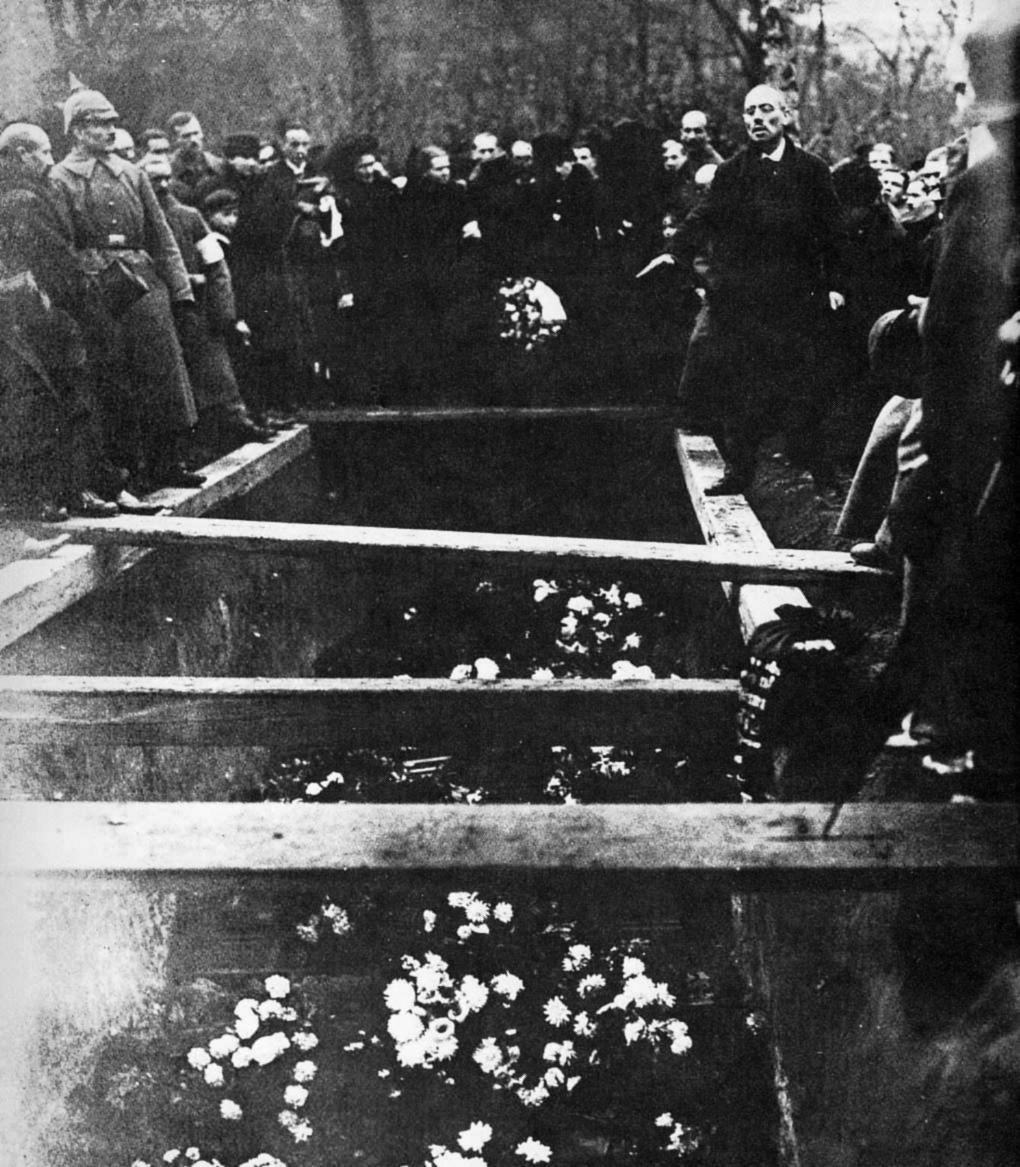

However, Lenin would not live to see the fruit of his labors. His

work took its toll on his health, which began to show signs of decline

toward the end of 1921 ... and in May of 1922 he suffered a stroke

which partially paralyzed him. He largely recovered ... though

now he had to look to others to carry much of the work. Then in

early 1924 he died. Now would begin a struggle for power among

the party elite that would have a highly determinative effect on the

further development of the Russian Soviet Union.

|

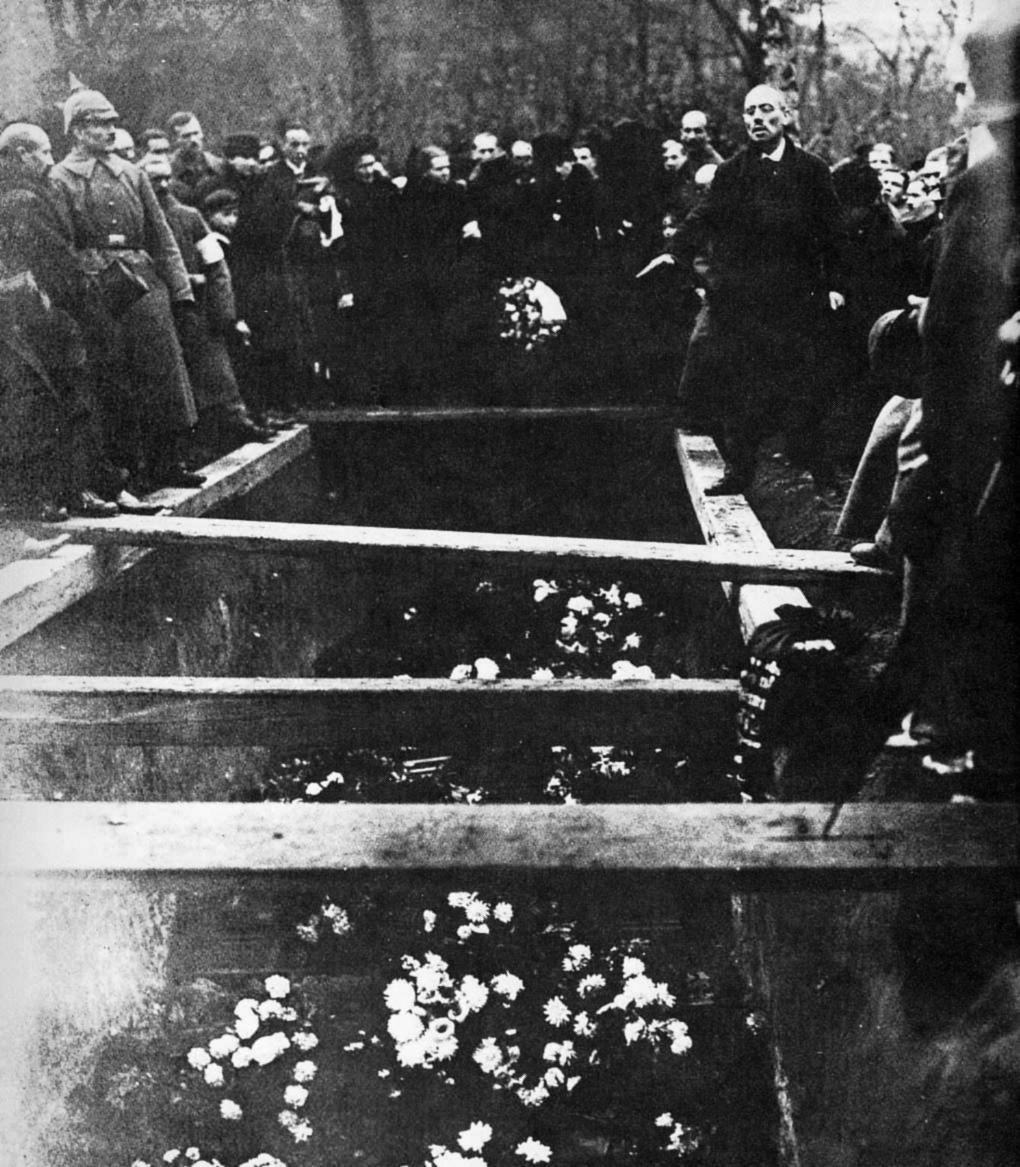

Funeral of V.I. Lenin -

1924

THE GERMAN WEIMAR REPUBLIC |

The

Germans themselves had not asked for a democracy or republican form of

government. It had been pushed on to them as a pre-condition

imposed by their enemies as the price required to secure the peace the

Germans so eagerly sought. To be sure there would be those

(mostly intellectuals of the Socialist variety) who supported the idea

of a German republic. But for most of the Germans this mattered

little. Eventually (the early 1930s) the Republic would be

considered even a bit treasonous because of its birth in what

increasingly came to be understood as a wartime betrayal of Germany.

Actually, very little changed about German society because of this

changeover to a republican government. Although the heads of the

various states making up the German union were gone, their

bureaucracies remained, conducting political business as usual in

Germany.

The street violence that sent Wilhelm into exile continued to mount,

giving opportunity (November 1918 to January 1919) to a group of

leftist radicals (the Sparticists, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa

Luxemburg) to attempt to spark a German revolution similar to

Lenin’s. But they ran into the stiff resistance of returning

soldiers who formed themselves into anti-socialist units (the Freikorps

or Free Corps) who went about gunning down radicals whenever they

gathered. A similar attempt to establish a Soviet Republic in

Bavaria (April-May 1919) was also taken out by the Freikorps.

Thus the only events resembling something of a real revolution in

Germany were quickly snuffed out.

Less radical Socialists quickly moved to fill the political void

created by the departure of Wilhelm. A Provisional Government was

quickly established and Friedrich Ebert, a Social Democrat, was made

its head. Elections were soon held (January 1919), in which a

number of parties (many makeovers of the parties of the days of

Imperial Germany) took their seats in the Reichstag, although the

Social Democrats were by far the largest. Ebert was elected as

the republic’s new President. Being concerned about how easily

urban mobs (Paris, Petrograd and now Berlin) were able to dominate

their nation’s politics he decided move the task of writing a new

constitution to the town of Weimar.

|

German troops marching home

from the war through the Brandenburg Gate victory arch

Smashed grocery store windows

in hungry Berlin - 1919

The "Sparticists" attempt

a Communist capture of post-war Germany

Leftist soldiers during Christmas

fights in the Berlin City Palace - December 1918

Leftist soldiers during Christmas

fights in the Berlin City Palace - December 1918

Deutsches

Bundesarchiv

German Sparticists crowding

the streets of Berlin - January 1919

German Sparticists crowding

the streets of Berlin - January 1919

Sparticist militia in the streets of

Berlin

Sparticist militia in the streets of

Berlin

Karl Liebknecht addressing

a crowd of pro-Soviet or Communist Sparticists in Berlin (January 1919)

Karl Liebknecht at a funeral

of of followers killed by the Freikorps - January 1919

(he himself was assassinated

a few days later)

German Free Corpsman (member

of one of the Freikorps) at a Berlin street barricade

during the March

1919 Sparticist uprising

Nurses tending wounded German

Free Corpsmen - 1919

Nurses tending wounded German

Free Corpsmen - 1919

German Free Corpsman resting

- 1919

Foreign Records Seized,

1941, National Archives

A converted British tank

put to German service in Berlin helping to crush the Communist

uprising there - January 1919

Library of

Congress

Berlin - Executed Sparticists - March

1919

Berlin - Executed Sparticists - March

1919

Deutsches

Bundesarchiv

Meanwhile

Germany was waiting to see what were going to be the exact terms

required of it in order to secure formally a new post-war peace.

They were harsh.

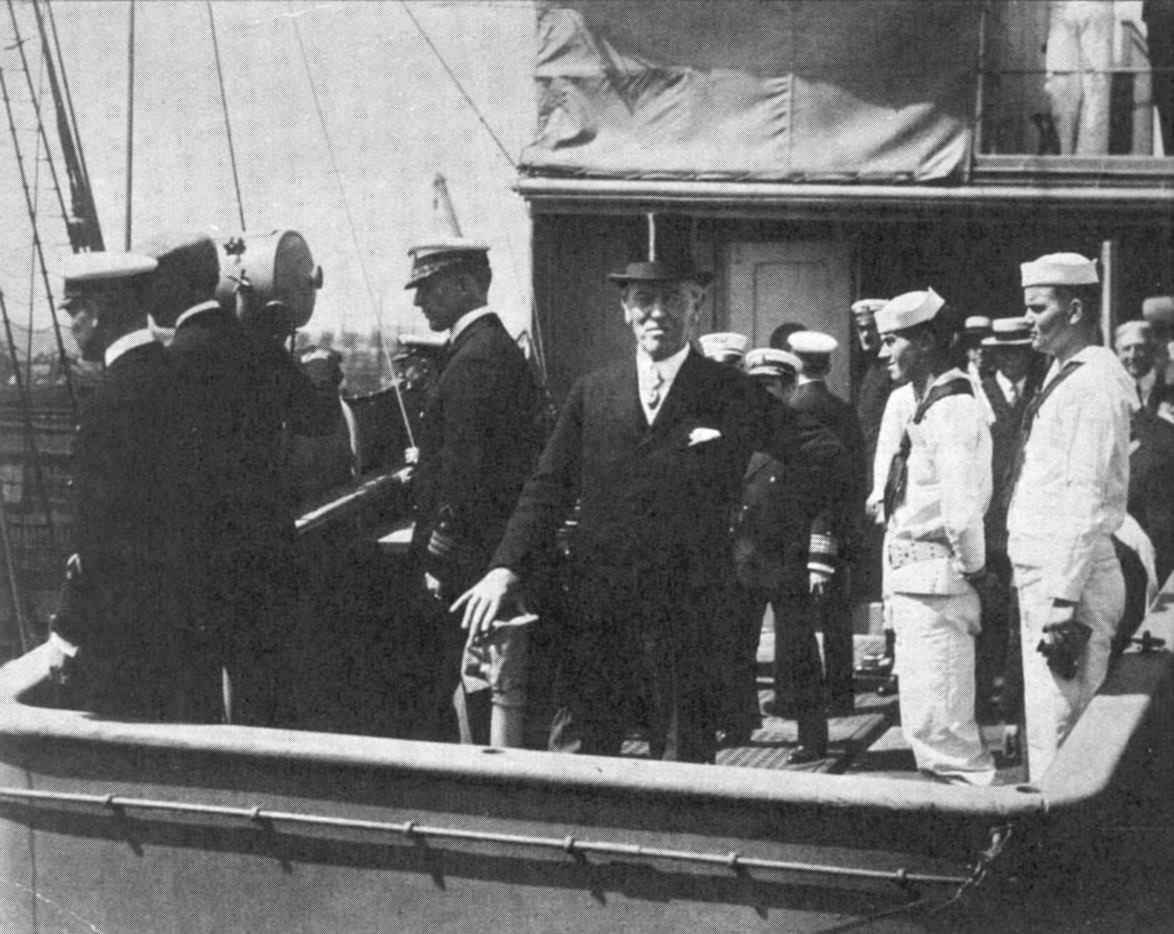

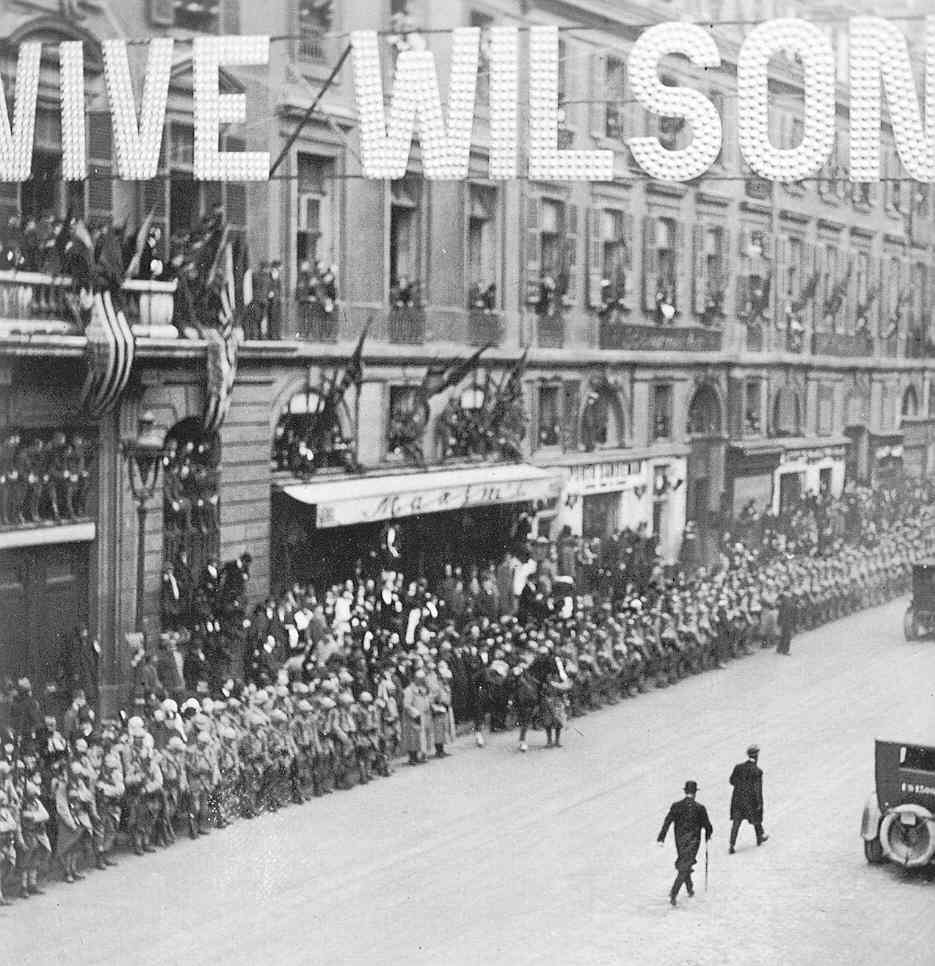

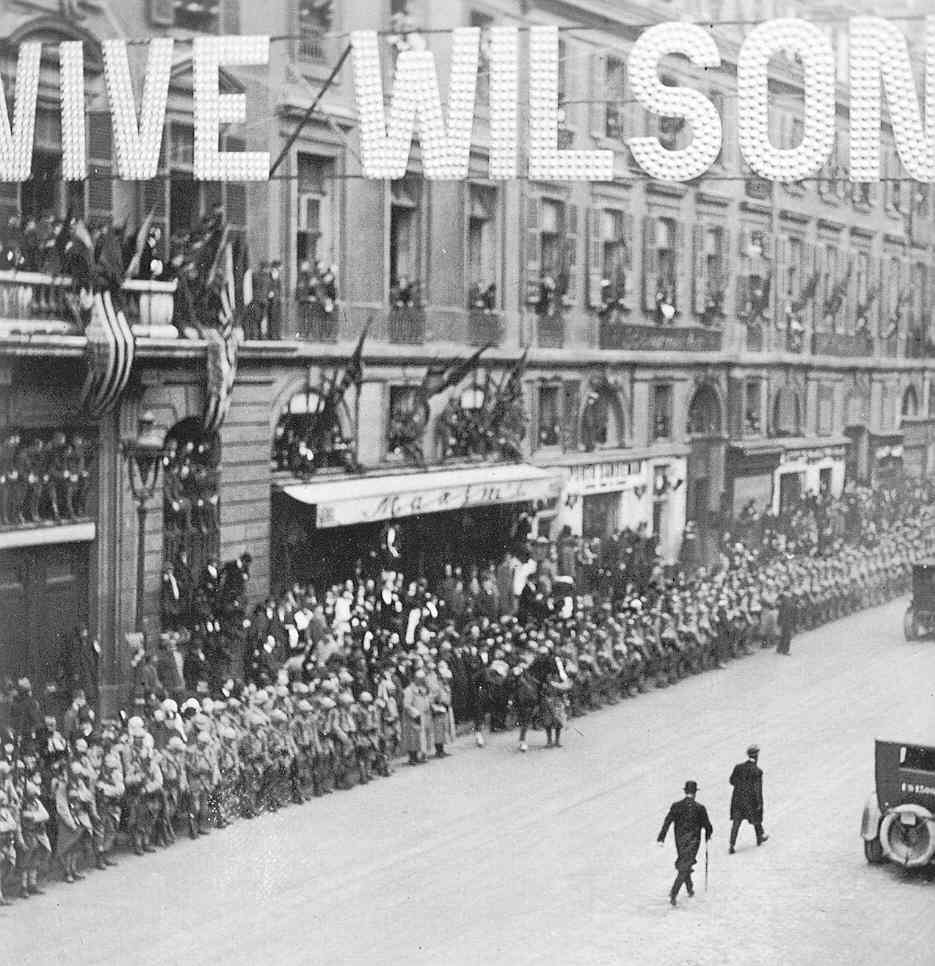

Wilson's (and Americas') grand disappointment. Wilson had himself traveled to Paris to ensure personally that his

promised Fourteen Points would be the terms by which the final peace

settlement with Germany was shaped. Upon his arrival in Europe he

was celebrated so wildly by the cheering crowds that he certainly

expected to be supervising the treaty negotiations from a position of

great strength. But his own idealism blinded him to the actual

social dynamic taking place. The Europeans were cheering him

because his American troops had seemingly tipped the balance of

military power in Europe so as to finally give the Allies their

long-sought victory. They saw in him their national victory ...

not some abstract idea of a new world of international peace and

understanding. Their sense of victory over a hated enemy was what

excited them. Years of slaughter, of destruction of homes and

villages, of wounded family and friends returning from the front, was

what filled their minds.

The European leaders responsible for negotiating a peace with Germany

understood what was expected of them. Their people wanted revenge

... not reconciliation and equity.

Sadly, Wilson at that point had nothing more to bring to the

negotiating table. America had played its part ... and had

departed, back to homes and towns unaffected by the war. America

had not suffered as the Europeans had. It was thus easy for the

Americans to be high-minded about a future peace. After all, that

had been the motif of the American entry into the war from the

beginning.

But that American high-mindedness was soon to turn to bitterness, not

just by Wilson but by the American people who were shocked when they

heard of the political deals being worked out among the British, French

and Italians. Nothing had seemed to change in the behavior of the

cynical Europeans. Americans had asked for nothing in its

participation in the war except for the Europeans to join them in

building a new and safer world. But the Old World seemed to have

betrayed the Americans: glad to get American help but only to advance

their own greedy national interests. Americans now grew bitter,

ready to wash their hands of any further dealings with the cynical Old

World.

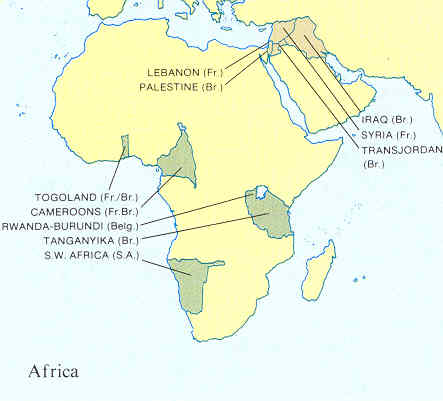

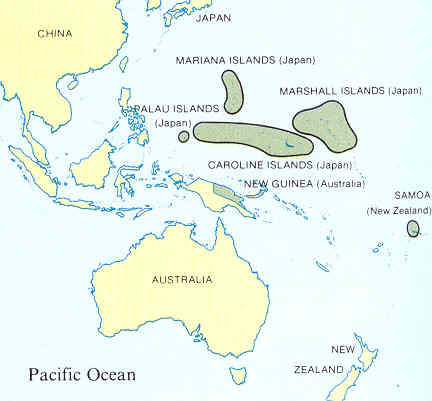

Germany. Indeed, the terms imposed on the Central Powers were harsh. In

the Versailles Treaty, Germany was forced to acknowledge total

responsibility in having started the war (remembering the Germans as

bullying ‘Huns,’ Americans were as insistent as the Allies on this

point). This then justified the subsequent punishment imposed on

Germany (here the Americans differed): the loss of lands to the newly

reconstituted state of Poland, of Alsace and Lorraine (plus for all

practical purposes the coal rich Saar) to France, and small sections of

Germany to Belgium (and in the future to Denmark). All the German

colonies in Africa and Asia would be given over to one or another of

the Allies (even the Japanese and Portuguese). The German army

and navy were to be reduced in size to a point of uselessness.

And massive reparations payments were to be made to the Allies for war

damages inflicted by Germany (the precise amount to be determined by a

special commission) ... and the heartland of German industry, the

Rhineland, to be occupied for the next 15 years to ensure compliance

with the reparations requirement.

In May of 1919 the German delegation received the terms prepared by the

Allies, expecting to be part of a discussion of those terms ... and

shocked when it was made clear that these were largely not

negotiable. The German cabinet resigned rather than agree to

these terms. President Ebert also wanted to resign but was

persuaded not to do so because refusal to agree to these terms meant

the resumption of the war. The French were ready at the border

... and the German army at this point was largely demobilized.

The Germans were given until June 22nd to accept these terms, or the

war would be resumed the next day. Thus very grudgingly did the

Germans accept these terms on the 22nd, the Assembly voting 227 to 138

to accept.

Austria-Hungary.

As for Austria-Hungary, two separate treaties (Saint-Germain and

Trianon) divided the empire into a number of independent states,

including Austria and Hungary – which now existed as separate nations,

each greatly reduced in size. Two new states were created from

this dismemberment: "Czechoslovakia," combining Bohemia, Moravia and

Slovakia and "Yugoslavia," combining Serbia with Slovenia, Croatia,

Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Macedonia.

Other provisions.

Romania, as promised previously, was awarded the Hungarian lands

of Transylvania. And Italy was given land along the southern

slope of the Alps and along the Adriatic Sea at Fiume – also as

previously promised.

And Poland was brought back into being

– having disappeared as a separate nation a century earlier (the late

1700s) – made up of lands taken from Germany, Austria-Hungary and

Russia.

Bulgaria was also reshaped by the Treaty of Neuilly,

with the new Yugoslavia receiving a section. But more

importantly, Greece received a key portion of Bulgarian Thrace which

had formerly given Bulgaria a position along the Aegean coast and thus

also direct access to the Mediterranean. Consequently, Bulgaria

had access only to the Black Sea and so now (like Russia) had to pass

through Turkish waters to reach the Mediterranean and the high seas.

Although the Russians were not part of the post-war negotiations, the

lands Russia had given up to Germany in its agreement ending its war

with Germany came up for redistribution. Out of this land were

carved the newly independent states of Finland, Estonia, Latvia,

Lithuania ... and what would become the eastern portion of the newly

recreated Poland.

In accordance with the Treaty of Sèvres, The Ottoman Empire was also

dismembered, with the setting up of "independent" Arab kingdoms

... under French and British supervision (principally Iraq, Syria,

Palestine, and Transjordan). And Greece was awarded huge sections

of Western Asia Minor ... so that what was left for a Republic of

Turkey was a greatly reduced territory comprising the interior

Anatolian plateau of Asia Minor. But this treaty was never

ratified by the Sultan, was rejected subsequently by the new Turkish

Republic, and after a major Greek-Turkish war was finally redrawn as a

less harsh 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

Serious problems.

Overall, the final treaties had left large groups of nationals in

foreign territory, especially Germans, but also Bulgarians and Magyars

(Hungarians). In rebirthing Poland (a result of France hoping to

secure an ally to the east of Germany to help keep Germany in check),

huge sections of German territory – the entire province of Posen and

most of West Prussia, including the "Polish corridor" of the Danzig

region, and of upper Silesia – were given over to Poland.

The

vast majority of Germans would then flee Poland over the next years,

straining even more the relations between the new German Republic and

the new Republic of Poland. Austria was reduced to a

third-rate power with the huge capital of Vienna, once the cultural and

political center of a vast empire, now reduced to supervising a

German-speaking hinterland only two times greater in population than

the capital itself. Economically (and culturally) this was

unsustainable.

Also a huge German-speaking population living in

the Sudetenland had been incorporated into the new Slavic-speaking

state of Czechoslovakia ... another sore point for the German

world. Hungary too was badly sliced up in losing two-thirds of

her land and population ... and like Austria, its capital Budapest

greatly overshadowed the tiny country to which Hungary had been

reduced. Also Bulgaria had not only lost its position on the

Aegean it had lost 1.7 million Bulgarians to foreign rule. And

Turkey would find itself in such a sour mood over the loss of its vast

empire that it was a powder keg ready to explode ... which it did in

1922 – with devastating results for the Greeks who thought that victory

in the Great War had set them up as the new major power in the Aegean.

All of this redrawing of Europe’s political map meant one thing:

in an age of nationalism these geographic revisions would serve to stir

a bitter revanchist mood among those cut off from the nationalist

heartland ... and an opportunity for demagogues to use such nationalist

hurts to reopen wounds left behind by the Great War and its

not-so-great peace treaties. Hitler in fact would depend on this

revanchist spirit to get his political career up and running.

|

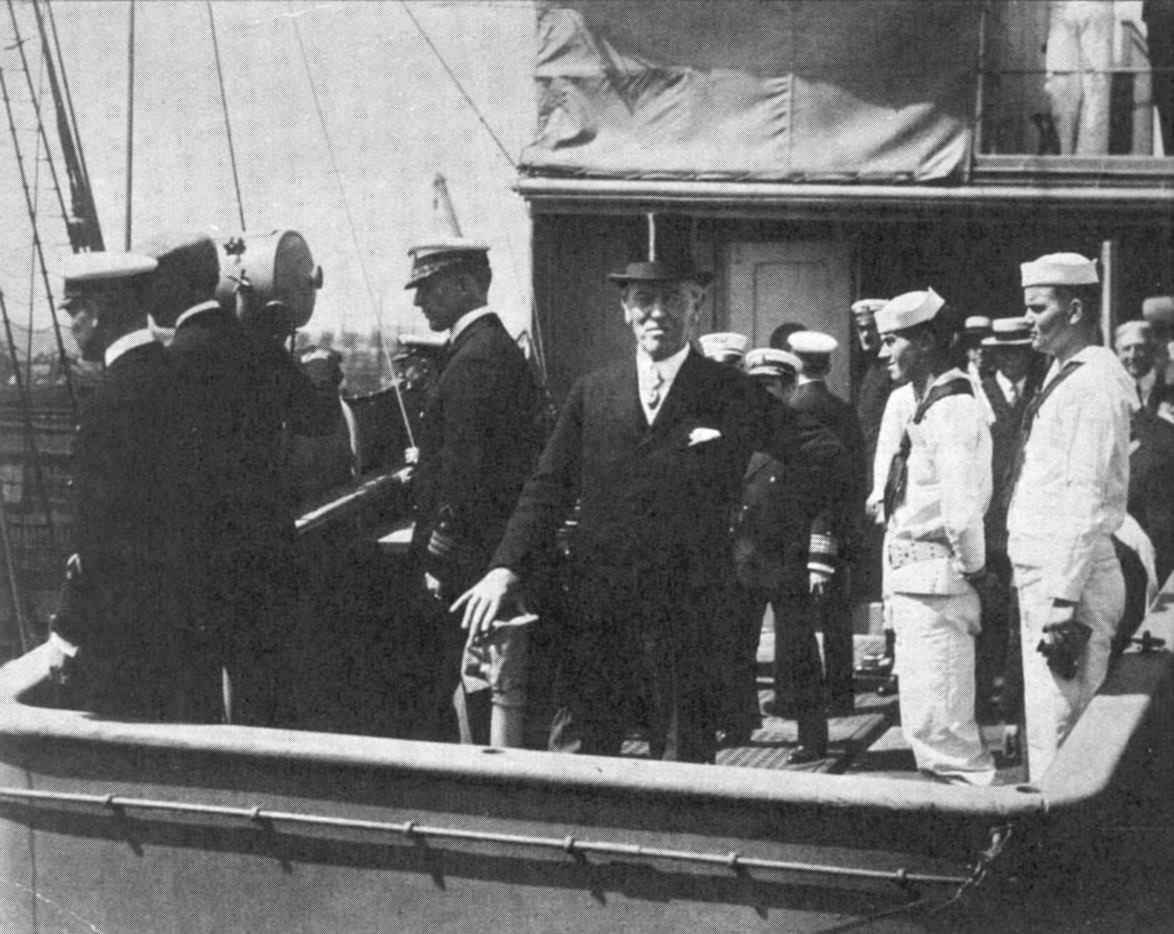

As he heads to Europe, Wilson

has no idea of the difficulties he will be facing to get a 'fair' post-war agreement between

the Allies and the Central Powers at the Paris peace negotiations

Woodrow Wilson leaving for

the Peace Conference in France

Wilson being hailed upon

his arrival in England

National Archives

The Paris crowds waiting

for President Wilson

National Archives

Paris - Wilson and

Poincaré

Paris - Wilson and

Poincaré

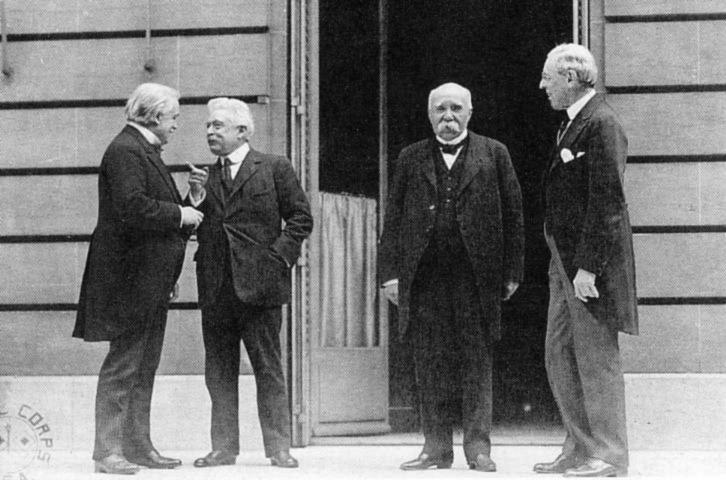

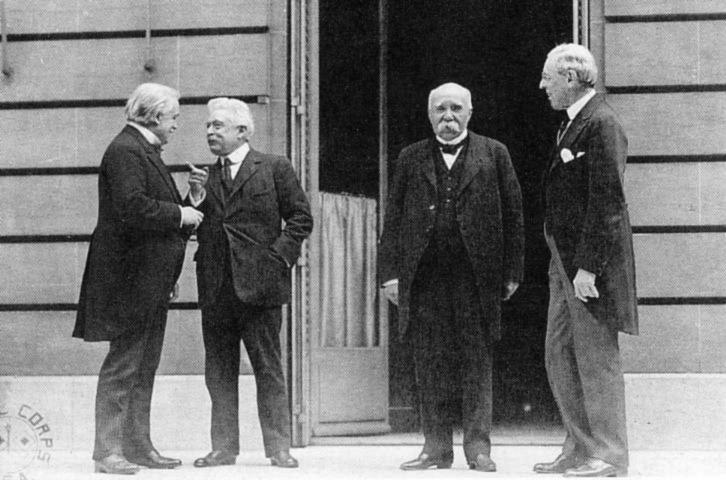

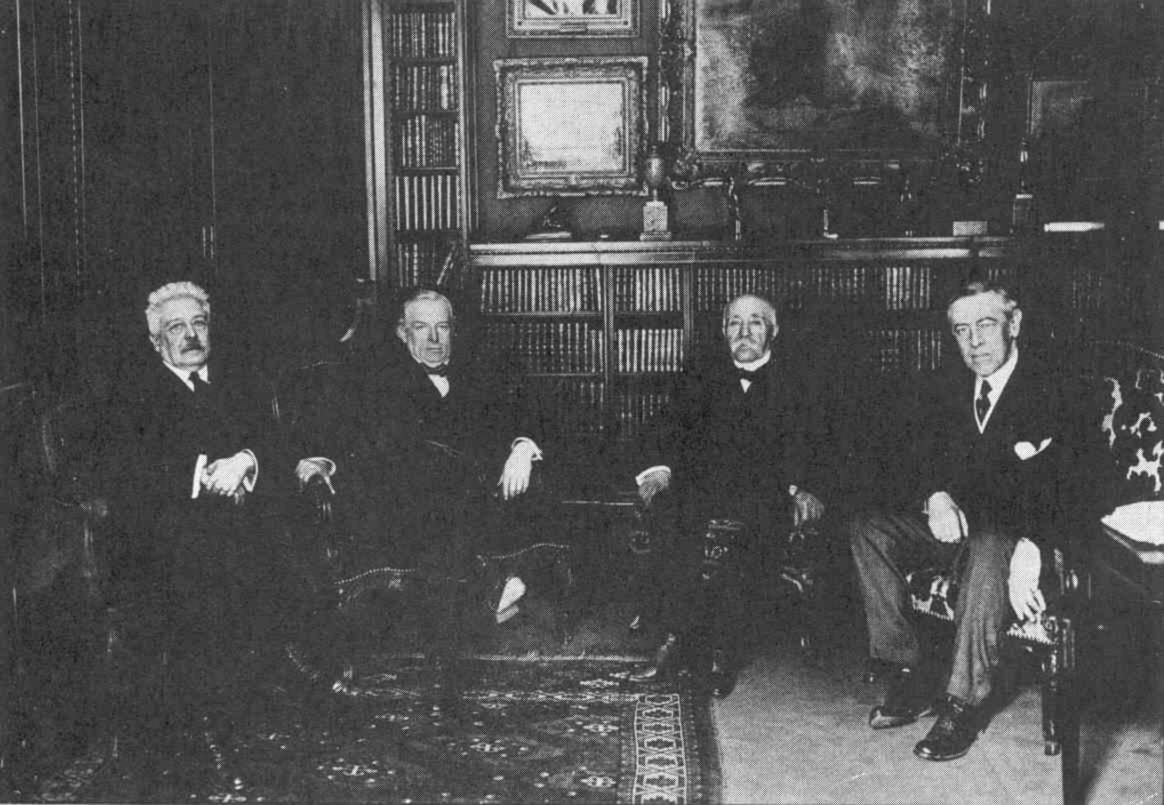

The Paris Big Four:

David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow

Wilson

The Paris Big Four:

David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow

Wilson

National Archives

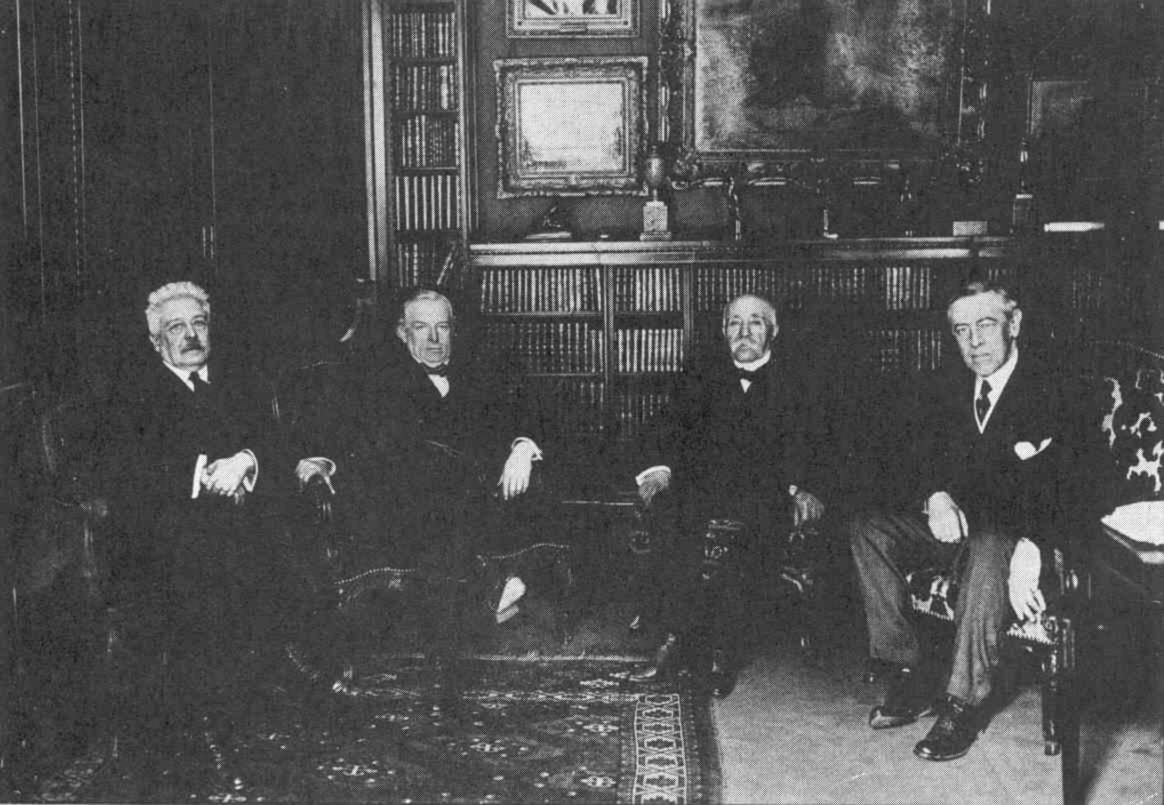

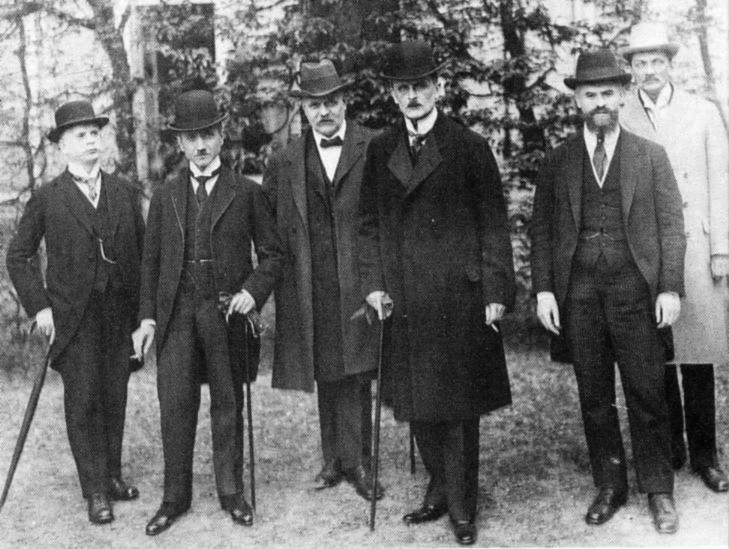

Orlando, Lloyd-George,

Clemenceau

and Wilson

The German delegation at

Versailles - 1919

The German delegation at

Versailles - 1919

National Archives

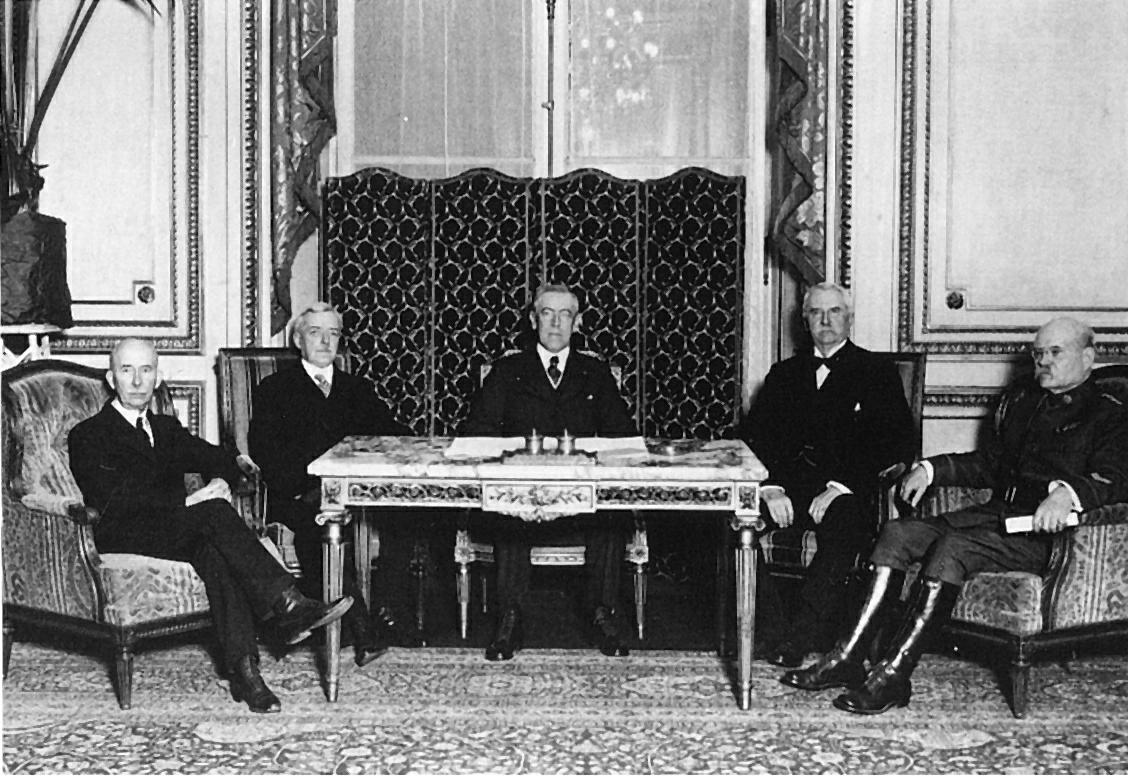

Wilson and the American

Delegation

at Versailles - 1919

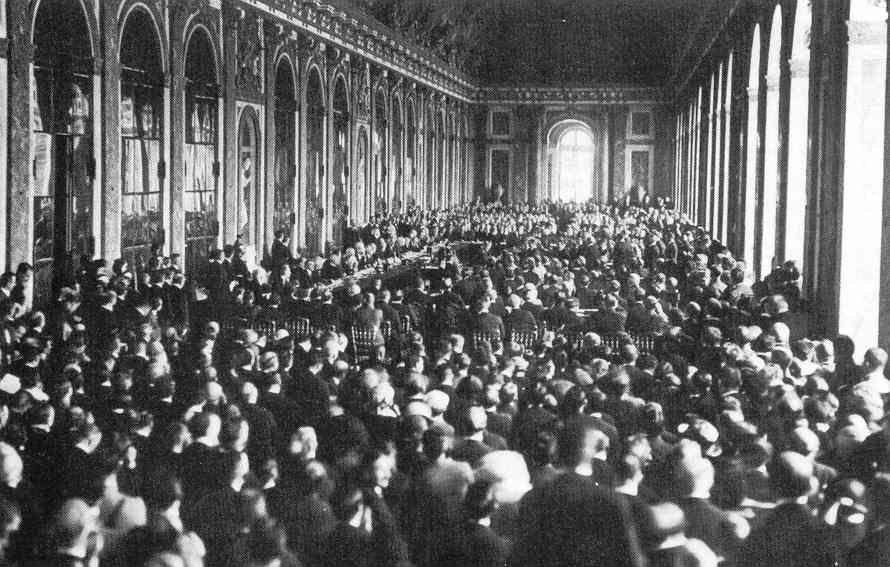

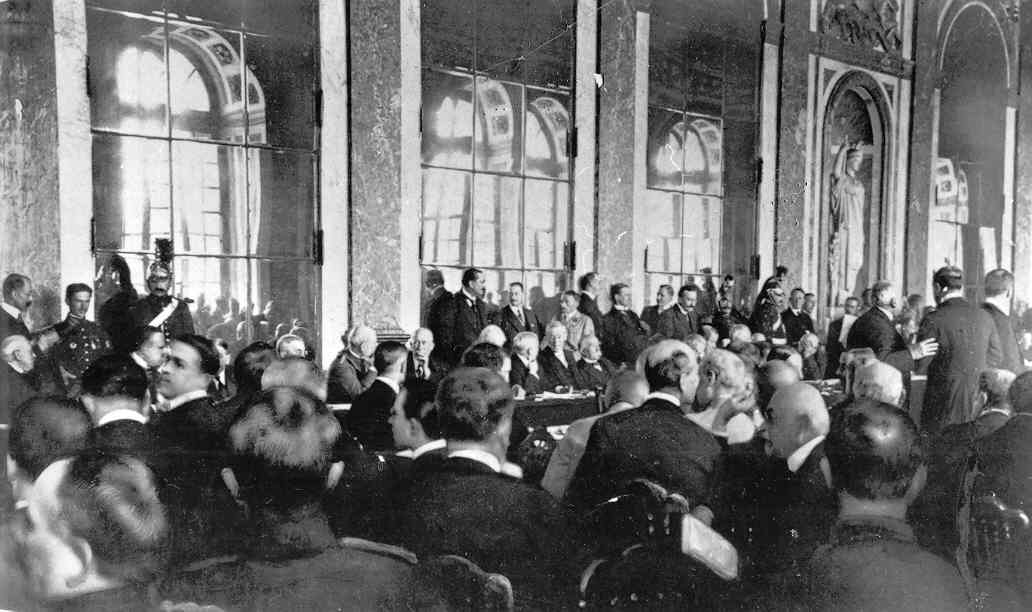

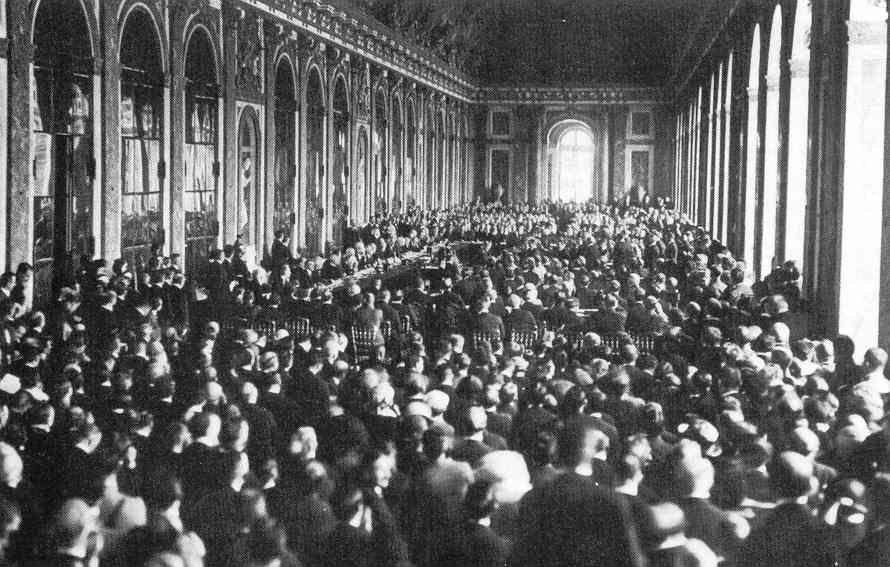

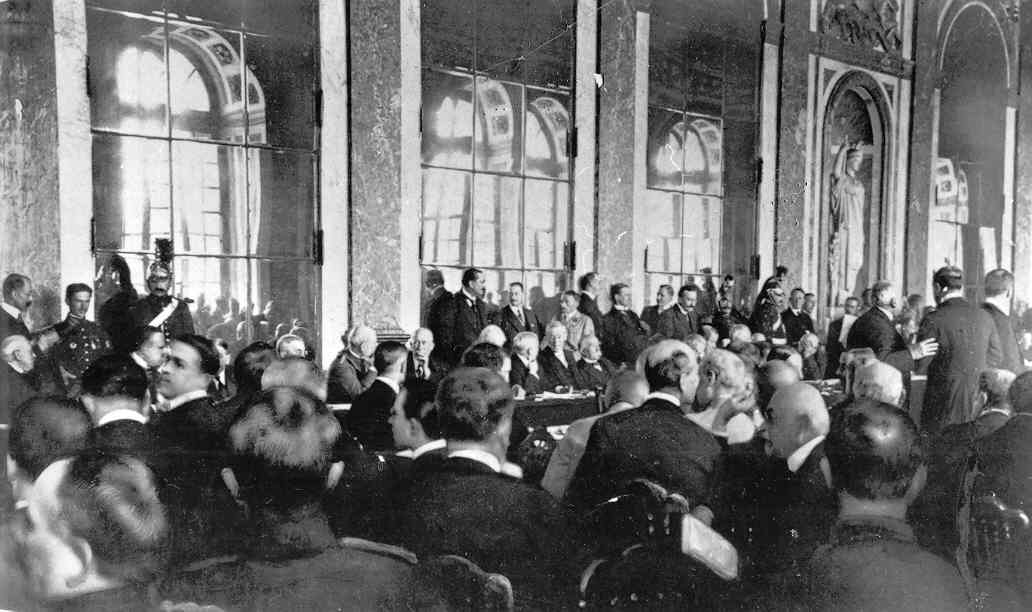

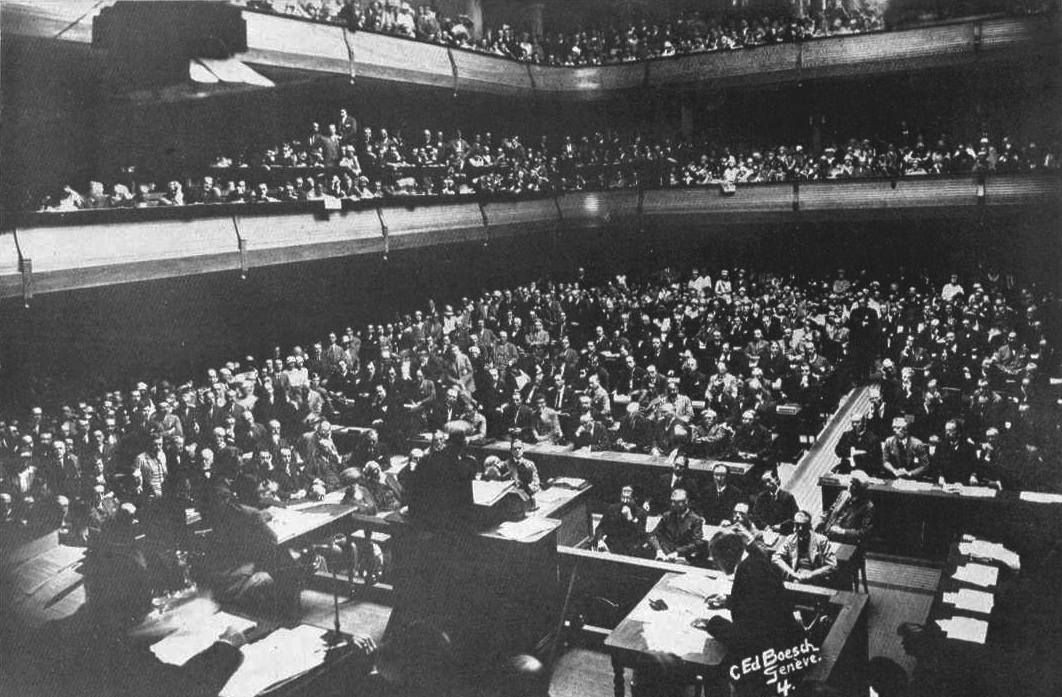

The signing of the peace

treaty at the Palace of Versailles – June 28, 1919

National Archives

The Signing of the Treaty

of Versailles

Spectators craning to see

the German signing of the Versailles Treaty - June 28, 1919

Spectators craning to see

the German signing of the Versailles Treaty - June 28, 1919

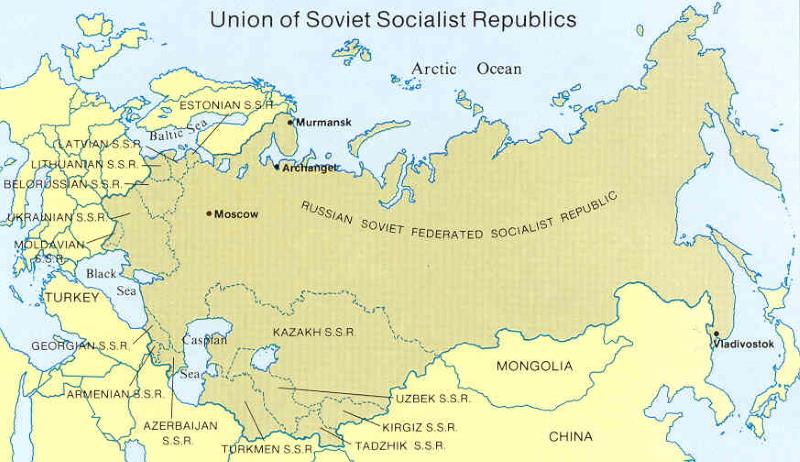

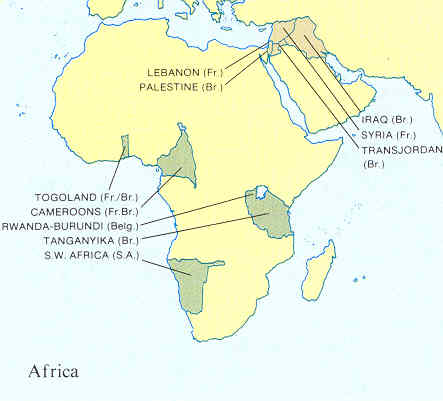

The territorial changes resulting from the post-war treaties

Europe after World War One

- 1923

German colonial territory

in Africa and the Pacific and Turkish imperial holdings

in the Middle East lost after World War

One

Wilson

himself was extremely unhappy at how the ‘peace’ went ... but held

fiercely to one hope: the Allies’ acceptance of (or covenant with) his

new League of Nations, an international organization that would bring

the nations together in diplomatic discussion before problems should

evolve to the point of disaster such as had been the case in the

startup of this recent war. Wilson was convinced that had there been

such an organization in 1914 the world would have been spared the

horror of this war.

Most importantly he hoped that once nationalist passions settled down,

cool headed diplomats could use the League to revisit these treaties

foisted on the war-wearied Central Powers and amend them in order to

produce a more just outcome, one that would remove the temptation of

the losers in this war to seek revenge in another war. Not being

able to back off the vengeful Allies in terms of the treaties, he

relied at least on their acceptance of the League to give him something

to bring home to America to show that its effort in the war had not

been wasted.

But in fact he came home to an America so burned by the behavior at

Versailles that it viewed with deep suspicion any kind of further

involvement in international affairs, much less European affairs ...

especially when it looked as if Wilson’s proposed League of Nations

might possibly take away from Congress and the nation the sovereign

right to decide for itself the nation’s particular stand on

matters of war and peace. Thus when the treaty was put

before the Senate for ratification it was defeated by a vote of 55 to

39.2 Further efforts to get it passed failed ... and eventually

the matter was dropped. Thus not only did the US not formally

recognize peace between itself and Germany3 ... it would not be joining

Wilson’s League of Nations (also part of the rejected Versailles

treaty).

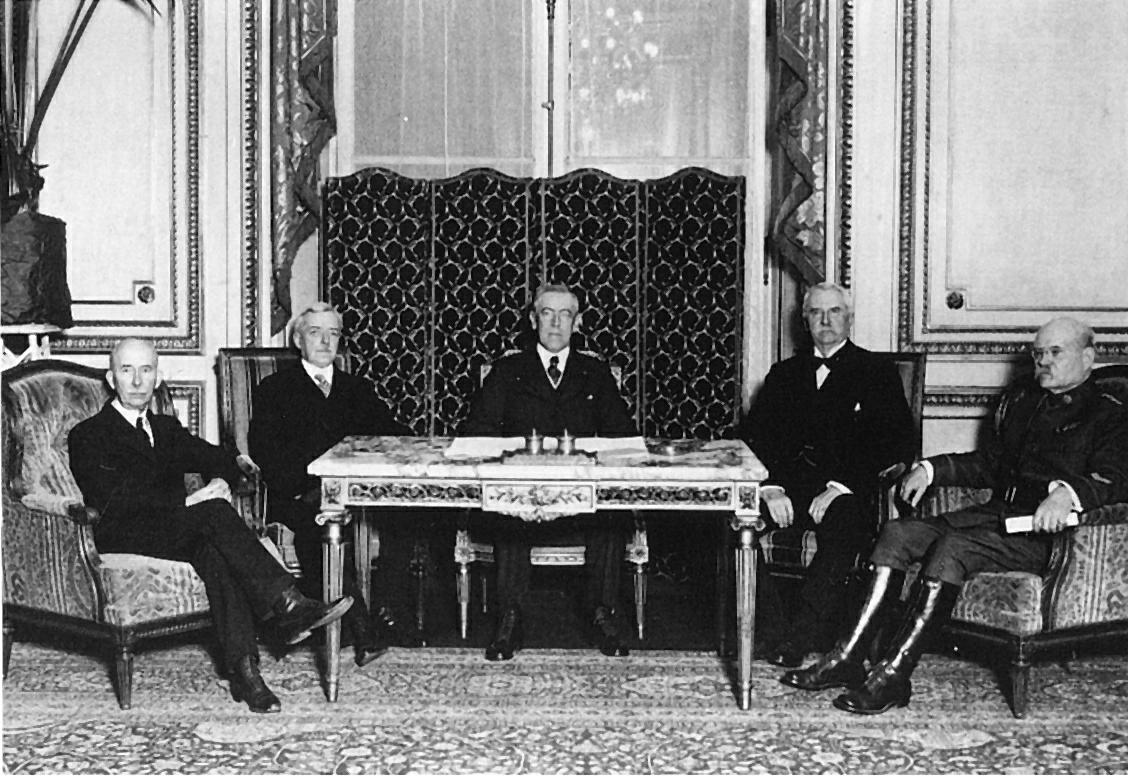

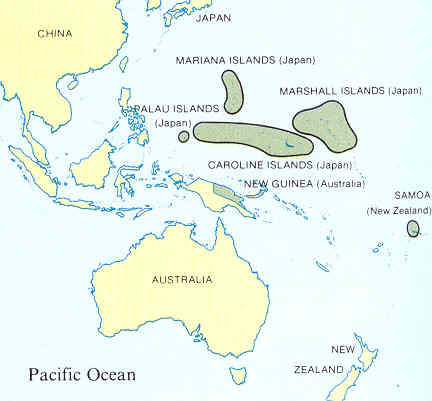

But

forty-four nations did sign the League's Covenant in June of 1919 and

then set up an international organization headquartered in Geneva,

Switzerland. It included a League Assembly – where all the

members had a voice. But it also included a League Council –

where four "Permanent Members, Britain, France, Italy and Japan

(America was originally expected to be its fifth Permanent Member) were

joined by four (ultimately ten) other members rotated among the rest of

the League membership … this smaller body to take on the more sticky

diplomatic matters as the "enforcers" of League policy. As

matters brought to the Council for action were considered to be of a

much more critical concern, decisions of the Council had to be fully

unanimous ... except in cases where one of the members of the Council

was involved. That nation was not entitled to vote on the matter.

Besides

these representative bodies, there existed in Geneva a full-time staff

or Permanent Secretariat to oversee the League’s business on a daily

basis. These were bureaucracies authorized to act on a

number of particular issues – such as health, education, labor, women's

rights, the drug trade, slavery and other such social questions ... all

very much in keeping with the rising spirit of Socialism in Europe (and

Progressivism in America) in the early 1900s.

The League was

also empowered to supervise a Permanent Court of International Justice

(PCIJ) located in the Hague (the Netherlands) – a world court designed

to try cases involving international law. Bringing cases before

the PCIJ occurred frequently during the 1920s ... most concerning

boundary questions raised by the treaties ending the Great War.

But as matters became darker and more bitter in the 1930s, the PCIJ was

involved less and less in the developing political dynamics.4

As long as these issues did not involve directly any of the major

powers, they were settled more or less peacefully and equitably ...

because it was in the interests of the major powers to see these issues

resolved in this manner. But when the major powers were

themselves involved, things did not work out so well ... often with one

or another of the major powers resigning from the League in

protest.5

Thus the Wilsonian dream (and the dream of others like

him) that a realm of reason could override narrower social interests

proved to be exactly that: just a dream. Nationalist power

considerations still prevailed in the international realm.

2The vote fell eight short of the required two-thirds vote needed for the Senate's approval of any U.S. treaty.

3It would do so in a separate treaty with Germany in 1921.

4The

PCIJ was nonetheless highly respected and was one of the several League

organizations that was carried over as part of the new United Nations

when it was set up in 1945.

5The

PCIJ was nonetheless highly respected and was one of the several League

organizations that was carried over as part of the new United Nations

when it was set up in 1945.

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

(Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee)

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge

(Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee)

Library of Congress

LC-USZ62-96172

President Woodrow Wilson,

seated at desk with his 2nd wife, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, standing at his

side. He was paralyzed on his

left side, so Edith holds a document steady while he signs - June 1920.

Library of Congress

The League's Palace of Nations - Geneva

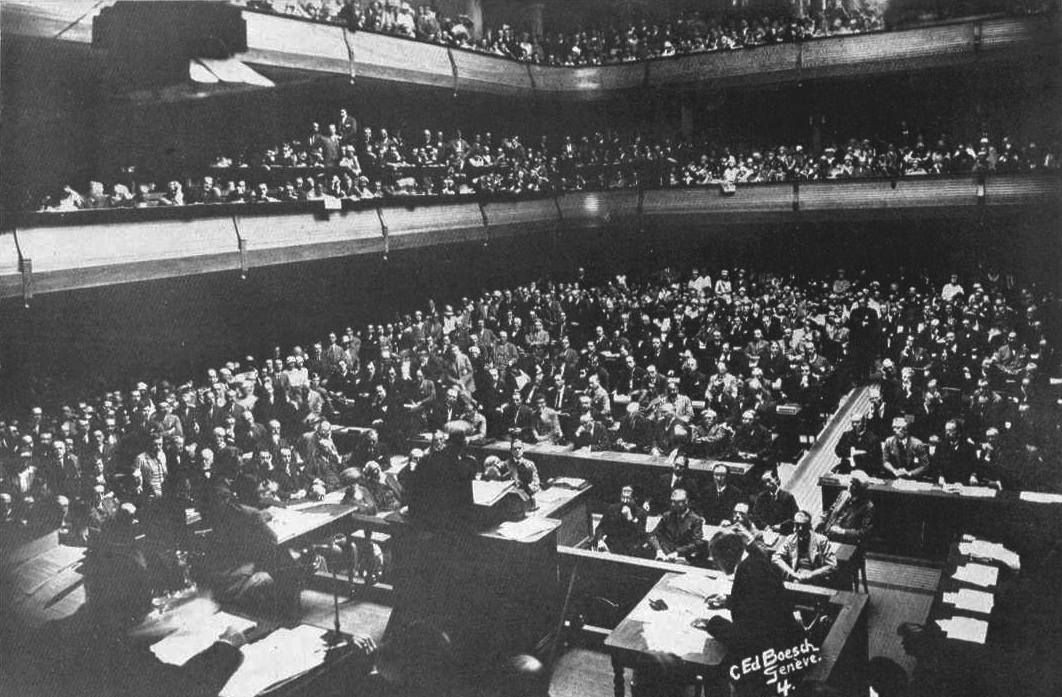

The September 10, 1926

meeting of the

League of Nations on the occasion of Germany's

entry into the

League. Foreign Minister

Gustav

Stresemann of Germany is addressing

the Assembly with his initial

speech.

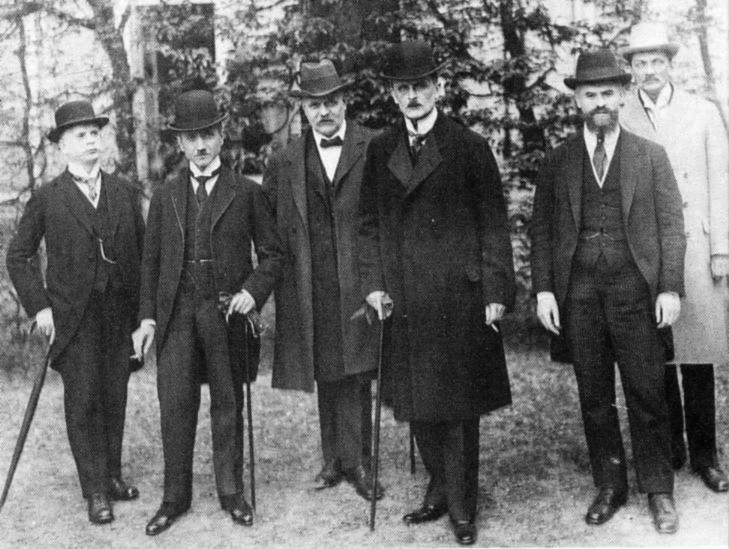

THE POLISH-SOVIET WAR (1919-1921) |

Poland

was restored as a nation by taking sections from defeated Germany and

Austria-Hungary ... and also a huge section of the former Russian

empire that had been given over to Germany as the price of Russia’s

armistice with Germany and which now, despite Germany’s defeat, could

not be recovered by Russia because Russia was so completely distracted

by its intense civil war. The new Polish Republic’s Head of

State, Józef Piłsudski, a Polish Socialist and Poland’s leading wartime

military commander, sensed the fragility of the new Polish state,

especially with respect to the Russian lands it had acquired ... and

pushed for the expansion of its borders eastward into Russia to

increase its security. Lenin, on the other hand saw Poland as

directly in his path as he planned to spread or at least link up with

the communist revolutions to the west in Germany, Hungary and other

places in Europe where revolution seemed imminent. Sensing that

the Russians were about to invade Poland, Poland decided to strike

first.

Initially the Polish were largely successful, especially as they headed

their expansion toward Ukraine to the southeast (the April 1920 ‘Kiev

Offensive’). But as the Bolsheviks began to secure more control

in Russia (the Polish attack actually generated a new sense of Russian

patriotism supportive of the Bolsheviks) the Russians were able more

effectively to counter the Polish expansion ... and even by late May

begin to reverse course. By July the Polish troops

were in full retreat. And by August Lenin’s Russian troops were

just outside the Polish capital Warsaw.

With Poland seeming about to collapse, political disorder begins to

infect all parties involved, domestically and internationally.

Piłsudski’s opponents at home made their move against him adding to the

Polish panic. The Poles turned on the large Jewish community,

seeing it as an ally of Russian Bolshevism. British Prime

Minister David Lloyd George’s reluctant effort to send military aid to

Poland by was met by the threat of a general strike by the pro-Soviet

Trades Union Congress which succeeded in blocking any arms

shipments. Instead a threat was issued to Russia that Britain

would intervene on Poland’s side if the Russians did not pull back to

the Curzon Line (outlined in December 1919 by Lord Curzon who attempted

to define actual ethnic boundaries between the Polish and the

Russians). The Russians ignored the threat. And the British

Labour Party, which was also blocking shipments to British troops still

in Russia trying to help the Whites, announced that they would do so as

well for any attempt to help Poland. The French, for their part,

sent a small military party as advisers to the Polish army ... and

tried also to send an army of mostly Polish expatriates to France –

which the Czechs refused to let pass through their country.

But at this point a dispute erupted between Soviet Generals

Tukhachevsky and Yegorov, and Soviet General Budyonny (and seemingly

also Soviet Commissar Joseph Stalin) decided to fight the Poles at

Lwów, rather than join their fellow generals at Warsaw ... and the

Russian effort at Lwów failed miserably. Now things began to turn

against the Soviets. Polish General Sikorski now took to the

offensive (August) and with Piłsudski joining him the Russian army was

thrown into disarray, with the Russians retreating deep into Russian

territory. At this point the Russians were ready to negotiate ...

with the Poles holding the decided advantage. But the Poles

themselves were exhausted and ready to end hostilities ... and the

League of Nations was pressuring Poland to settle. But it was

Polish domestic politics that settled the matter when Piłsudski’s

enemies forced him to give up territory (leaving a million Poles within

the Soviet Union ... to face subsequent persecution from the Bolshevik

authorities). Likewise, Piłsudski’s Ukrainian allies were also

left in Bolshevik hands ... with sad results. Thus in March of

1921 the Peace of Riga was signed between Poland and Russia, officially

ending the war.

Nevertheless the Polish-Soviet War did the West a great favor in

shutting down Lenin’s plans for a grand Soviet revolution throughout

Europe (industrial workers across Europe supported strongly just such a

revolution). It would inadvertently play also a role in the

contest for control of the Soviet Union between Trotsky and Stalin ...

fought over the issue of whether the Russian revolution was merely a

starting point for an even greater European revolution (Trotsky) or

whether the Bolsheviks should now simply look after “socialism in one

country,” Russia (Stalin). The war with Poland greatly

strengthened Stalin’s argument! But it also helped the newly

established countries of central Europe secure their independence ...

especially Lithuania which Lenin was planning to absorb – before Russia

lost its war with Poland. And the war brought forward Piłsudski

as Poland’s national hero and once again future leader ... and also

French military advisor Charles de Gaulle and Polish General Władysław

Sikorski, both of whom would lead their national armies during World

War Two.

|

THE GRECO-TURKISH WAR (1919-1922) |

Meanwhile,

further to the south, the carve-up of the defeated Ottoman Empire

created a range of social dynamics that disrupted, confused and nearly

collapsed any semblance of a post-war social order within what was left

of the Ottoman Empire. In the Turkish political heart of the

empire a deep split occurred between Ottoman authority (the autocratic

rule of the Ottoman Sultan/Caliph and his conservative supporters) and

a rising breed of Turkish revolutionaries descended from the Young Turk

mentality.

In many ways what broke out in Turkey resembled closely what had broken

out in Russia. Indeed, Lenin and his Bolsheviks would be key

supporters to the Turkish Nationalist Movement ... ultimately led by

the hero of Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal ... soon to be given the title

Atatürk, roughly equivalent to "Father of the Turks."

A big part of what inspired the Turkish Nationalist Movement was the

humiliating way the Sultan bowed to the dictates of the victorious

allies ... and how he allowed the near total takeover of Ottoman lands

by their wartime enemies. In part it was also motivated by the

idea that if Turkey did not modernize in every social respect possible

(economy, education, even world view, as well as politics and military)

Turkey would remain a victim to the whims of their occupiers.

Thus soon after the war ended Turkey found itself in a state of

domestic turmoil as the traditionalists and the modernizers fought each

other for control of Turkish society.

The conflict between the two Turkish parties actually broke out in the

summer of 1919 when a conference was called by the revolutionaries to

begin the process of modernizing Turkish society from top to

bottom. They also created a negotiating team to meet in Paris

with the Allies in order to give stronger representation to Turkey,

hoping to counter the weak representation the Sultan’s emissaries had

given the Turkish empire. That fall they moved to set up a new

government at the city of Ankara in the Turkish heartland ... in

opposition to the Sultan and his weakened government in

Constantinople. In short, Turkey now had two governments.

At the same time similar activities were going on among the Greeks, who

had joined the Allies under the promise by British Prime Minister

Lloyd-George of the further expansion of Greek territory as a reward

for Greek participation. The Greeks were led to believe that

their country would be expanded against Ottoman holdings not only in

the Balkans but also in coastal Asia Minor and the Anatolian interior

as well. The coastal regions of Asia Minor had anciently been

quite Greek – but over the more recent centuries had been heavily

re-cultured along Turkish-Muslim lines. Nonetheless, almost 20%

of the population of Asia Minor/Anatolia was still Greek Christian in

language and religion. A Greek community of some size existed

along the coastal regions of Asia Minor around the city of Smyrna – and

the Greeks probably rightly feared for their safety against Turkish

ethnic hostilities encouraged by the strongly Turkish nationalist Young

Turks (Christian Armenians had suffered horribly during the war at the

hands of the Young Turks and their Turkish nationalist

supporters). Also the spirit of Greek nationalism ran strong –

with the hope that even the ancient center of Greek or Byzantine

culture at Constantinople (Istanbul) might be restored to the Greeks.

Unfortunately, as was frequently the case, the Allies had made offers

to other national groups (such as the Italians) that were destined to

conflict with the post-war picture that had been presented the

Greeks. Within Greece itself the question of getting involved in

the war at all also had badly split Greek politics. The liberal

political leader Venizelos was much in favor of joining the Allies

whereas King Constantine was fearful of the consequences of such

involvement and stood firm in his intention to keep Greece a neutral

nation. In the end Venizelos won out, King Constantine was

deposed (his son Alexander taking the throne, but being basically a

puppet to Venizelos), the Greeks joined the Allies, and at war’s end

Greece was looking forward to building a greater Greece that resembled

the territorial reach of Greece thousands of years ago.

But the Italians, who partially as descendants of the once great Empire

of Venice, were also looking forward to seeing Italian power extended

deep into the Eastern Mediterranean ... and into the Asia Minor

peninsula (roughly today’s Turkey) as well, a matter which now required

the negotiators in Paris to handle matters very carefully (the Italians

were already upset that they were not getting what they expected on the

eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea ... and had even left Paris in a huff

for a while!). Also Britain and France had their own plans for

the Ottoman Empire, not just in setting up puppet Arab Kingdoms but

even in the occupation of the Asia Minor peninsula and even the capital

Constantinople itself. The Turks consequently were left to rule

on their own only a tiny portion of what had once been a great empire.

This is what decided Venizelos to push from the Smyrna region of

western Asia Minor that had finally been allocated to the Greeks

eastward, deeper into Asia Minor. He was counting on the support

of the Allies ... or at least the British, which he did get, though not

greatly. In May of 1919 the Greeks made their move by landing

twenty thousand Greek soldiers at the port city of Smyrna. From

there the Greek troops, encountering only rather light or disorganized

Turkish resistance, began spreading their zone of control towards the

east, into the Anatolian interior. By August of 1920 the

government of the Turkish Sultan was ready to agree to terms of a full

treaty (the Treaty of Sèvres) ending for them their part in the Great

War. The treaty was extremely generous to Greece – and very

humiliating to Turkey.

At first the Greeks were greatly victorious in their encounters with

the Turks, who seemed unable to get a strong defense organized.

Deeper and deeper into Turkish territory the Greeks went, with the

Turks giving up position after position. All through 1920 the

Greeks registered success after success. But then King Alexander

died (bit by a monkey), Venizelos called a national election ... which

he then lost (most of the Greeks were very tired of all the warring

that had been going on under Venizelos). The opposition (strongly

Royalist in nature) called Constantine back to the throne ... throwing

into confusion the matter of the Greek expansion in Asia Minor.

Now things began to go wrong for the Greeks.

Twice in early 1921 the Greeks were thrown back by the fierce Turkish

resistance organized by their leader Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk). The

Italians, who had been jealous of the Greeks, and the French, who

considered the Greeks now merely British clients, began to throw their

support to Kemal’s Turkish forces. Also Russia was supplying the

Turks with important weapons in exchange for some territory it received

from the Turks.

Atatürk had taken over the Turkish defenses and pulled his troops back

across a river to heights overlooking the river. On came the Greeks ...

and found themselves up against a Turkish army determined to give no

more ground to the Greeks. The battle raged on and soon became

one of resupply. Finally the Greeks felt it was time to pull

back. But once the retreat got underway it never seemed to find a

point to dig in and halt. Now it was Atatürk’s troops doing the

pushing ... rapidly advancing against retreating Greeks. At this

point Greek civilians in the west of Asia Minor began to panic.

On came the Turks even finally to the last Greek stronghold at Smyrna

... and there crushed the last of the Greek resistance (and burned out

the Greek and Armenian sections of this huge city). By

mid-September (1922) the Greeks had lost everything.

The war was over – and a new treaty (Treaty of Lausanne) had to be

drawn up between Turkey, Greece, Britain, France and Italy. It

provided for the transfer of populations: 500 thousand Muslims to be

relocated from Thrace to Asia Minor and over a million Greeks from Asia

Minor to Thrace, Macedonia and Attica (Eastern Greece).

Considering the scale of the ethnic cleansing that had occurred on both

sides during this war (whole communities of Turks on the one hand and

Greeks and Armenians on the other were completely obliterated) this

transfer of populations, though cruel in execution, was preferable to

remaining behind and being slaughtered in the heat of the intense

Greek-Turkish hatred that now existed between these two people.

This definition of

"Turk" comes largely at the expense of what it means to be "Armenian (during the Great

War) or "Greek" (during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922)

Ottoman Emperor Abdul Hamid

II (reigned 1876-1909). He was deposed by the

Young Turks in

1909 because they hated his weakness - but lived until 1918 just as the once-great Ottoman Empire

was being carved up by the World War I peace treaties

The Turks, both during and

after the War brutally refashion a sense of what it means to be a "Turk." In particular they vent

their powerful national feelings on a helpless Christian people - the Armenians

Armenians slaughtered by

the Turks - 1915

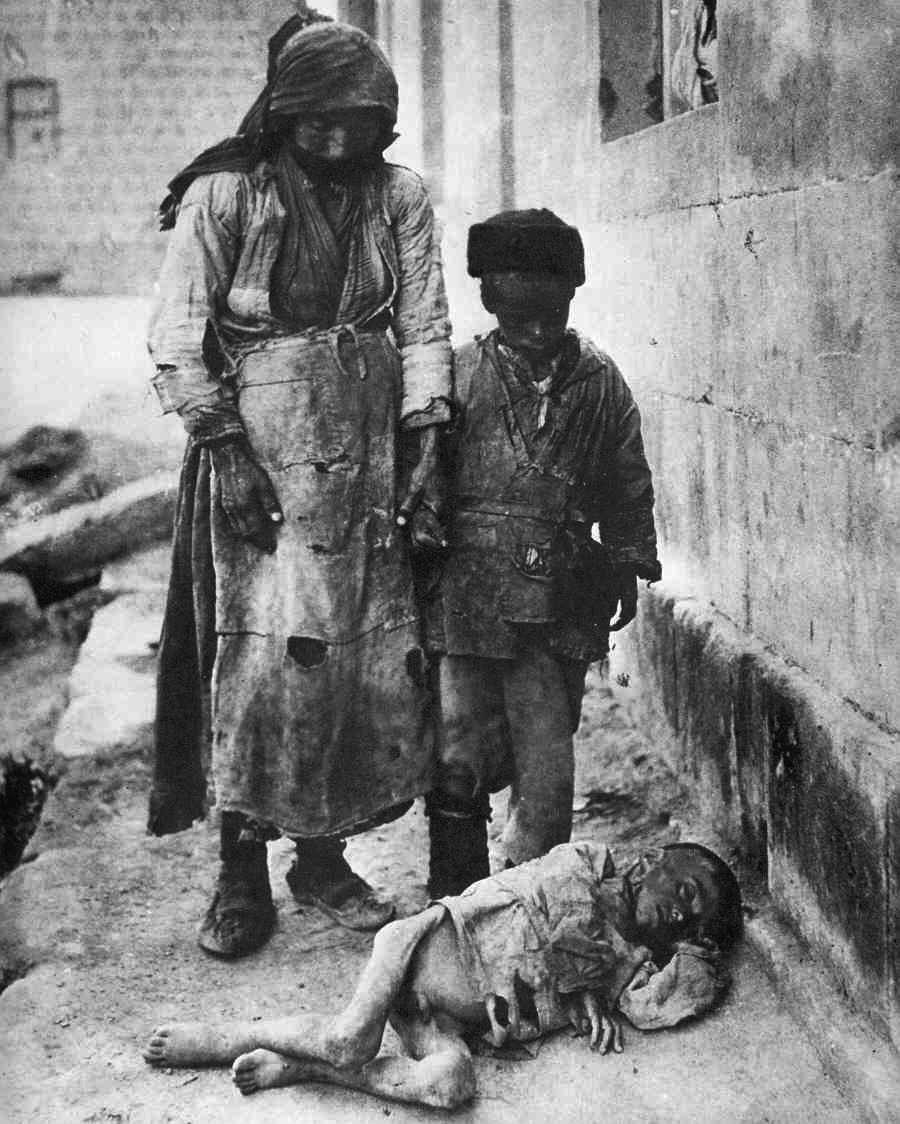

A starving child in Yerevan,

where the Armenians attempted to set up an independent republic after the War to avoid further

massacre by the Turks

The Greco-Turkish War of

1919-1922

The Greeks, sensing Turkish

weakness, decide to expand Greek territory from the Western

coastline (inhabited heavily by Greeks)

into the Anatolian interior of Asia Minor.

This will prove to be

a huge error.

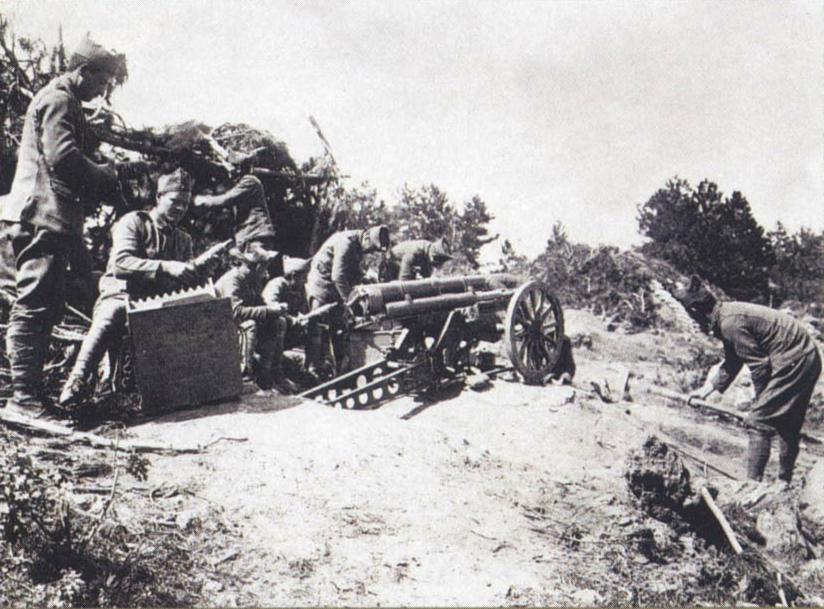

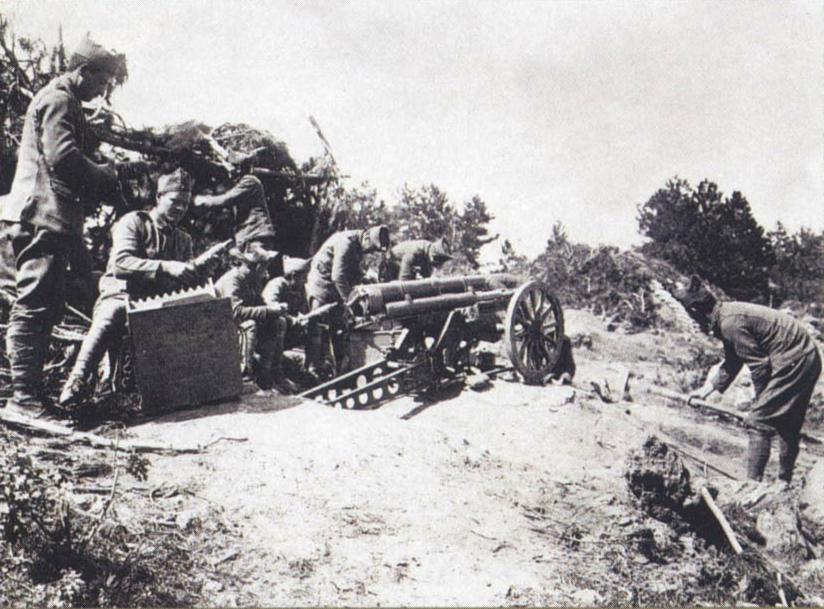

Greek artillery supporting

an infantry assault into Anatolia - August 1921

Greek artillery supporting

an infantry assault into Anatolia - August 1921

National Archives

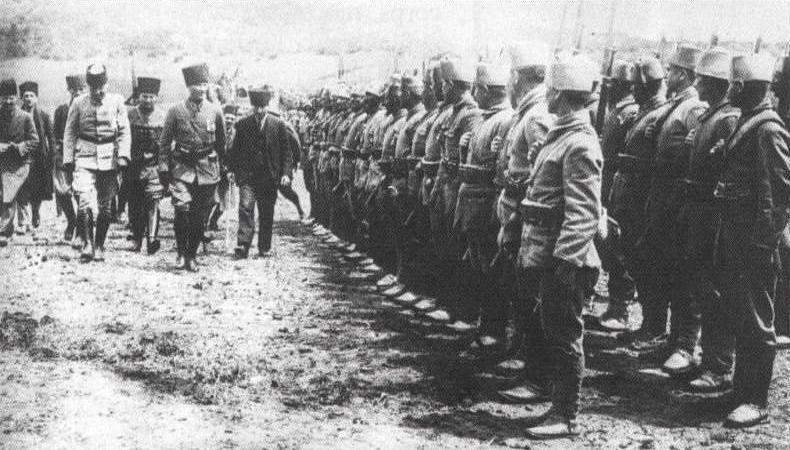

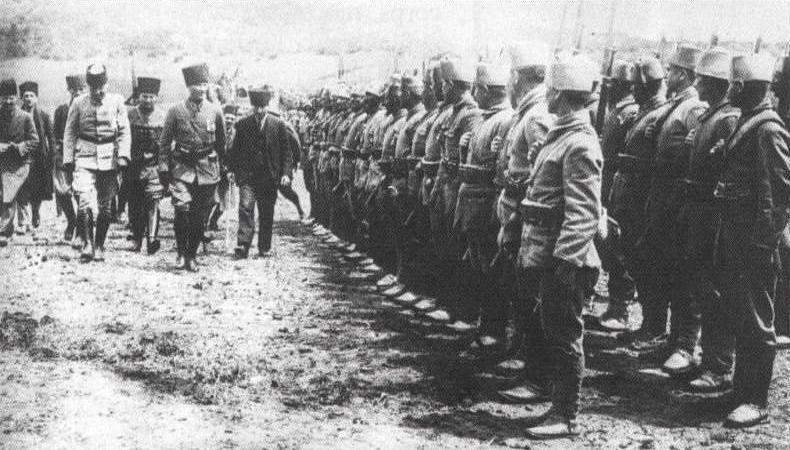

Mustafa Kemal (Turkish “hero

of Galipoli” during World War One) reviews Turkish troops at the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish

War. He will lead the Turks to a huge victory over the Greeks ... and will earn

for himself the title "Ataturk : "Father of the Turks"!

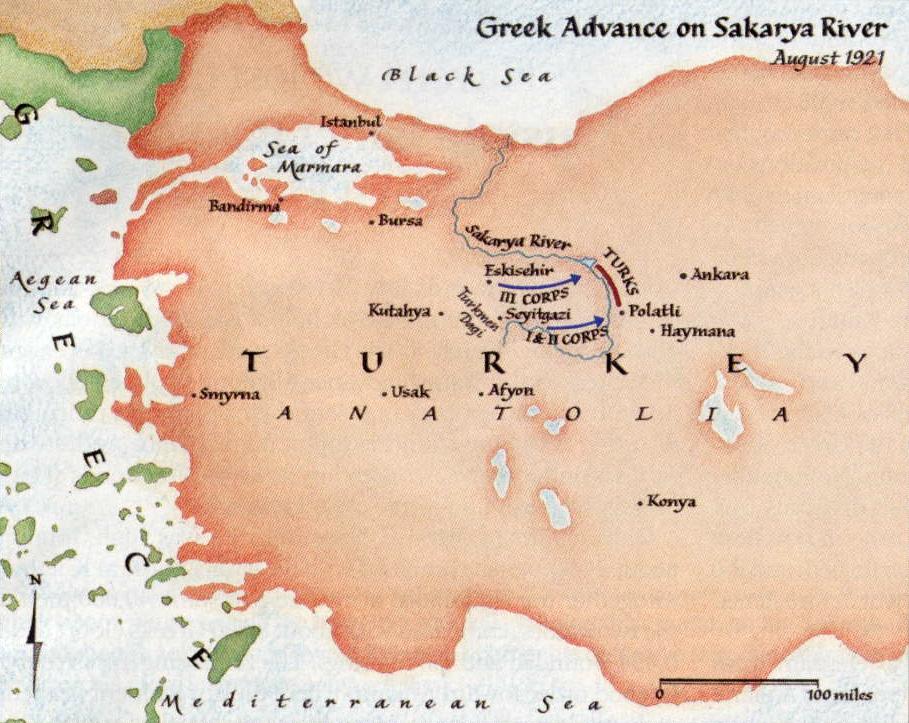

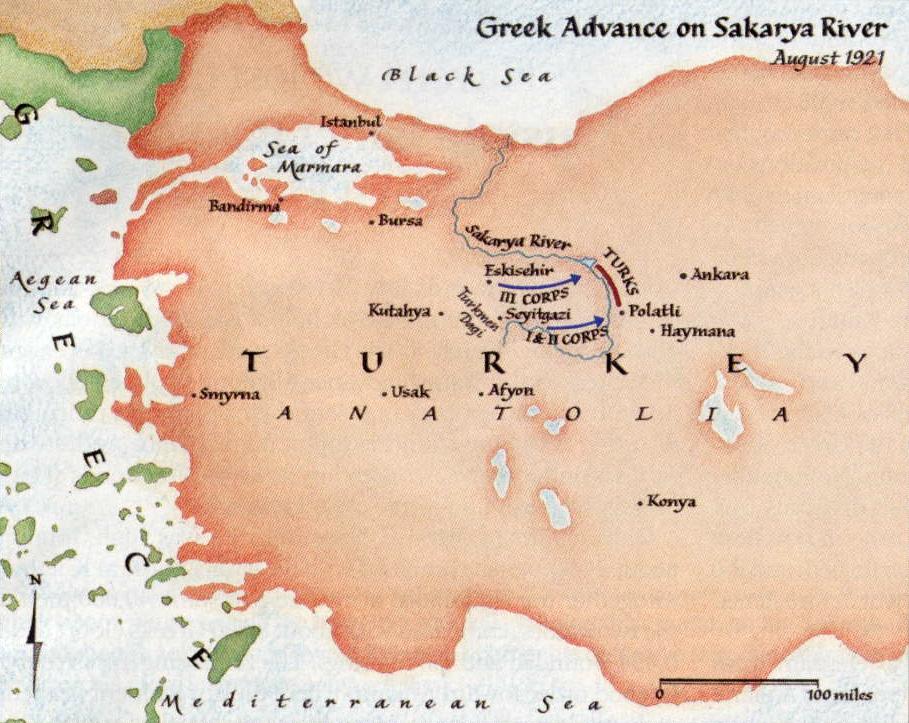

The Greek army's two-pronged

advance on the Sakarya River - August 1921. Ataturk drew his troops

back to a more compact line of Turkish defense across the river -- which would be the further

line of retreat before he began the Turkish advance against the Greeks

Joan Pennington

- Military History,

September 2006, p. 53

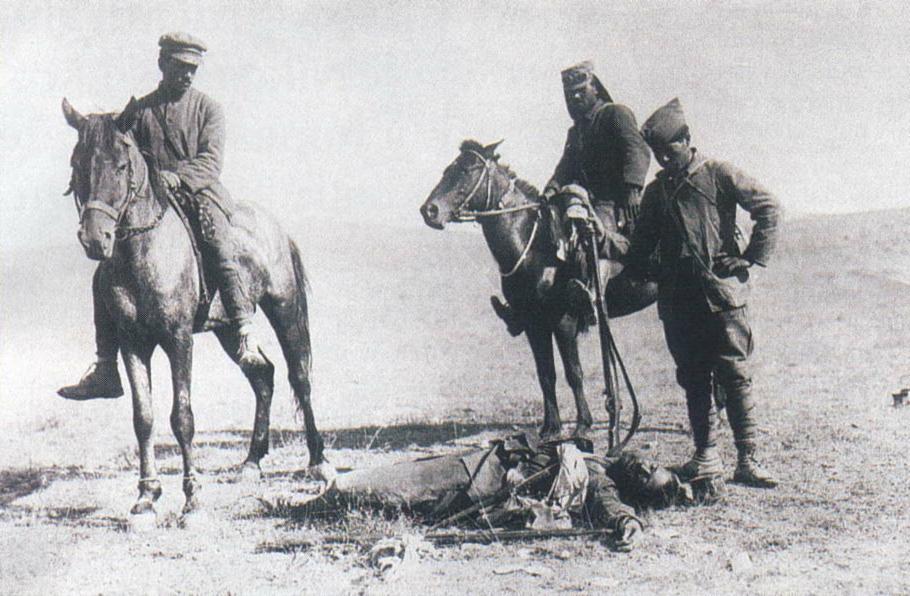

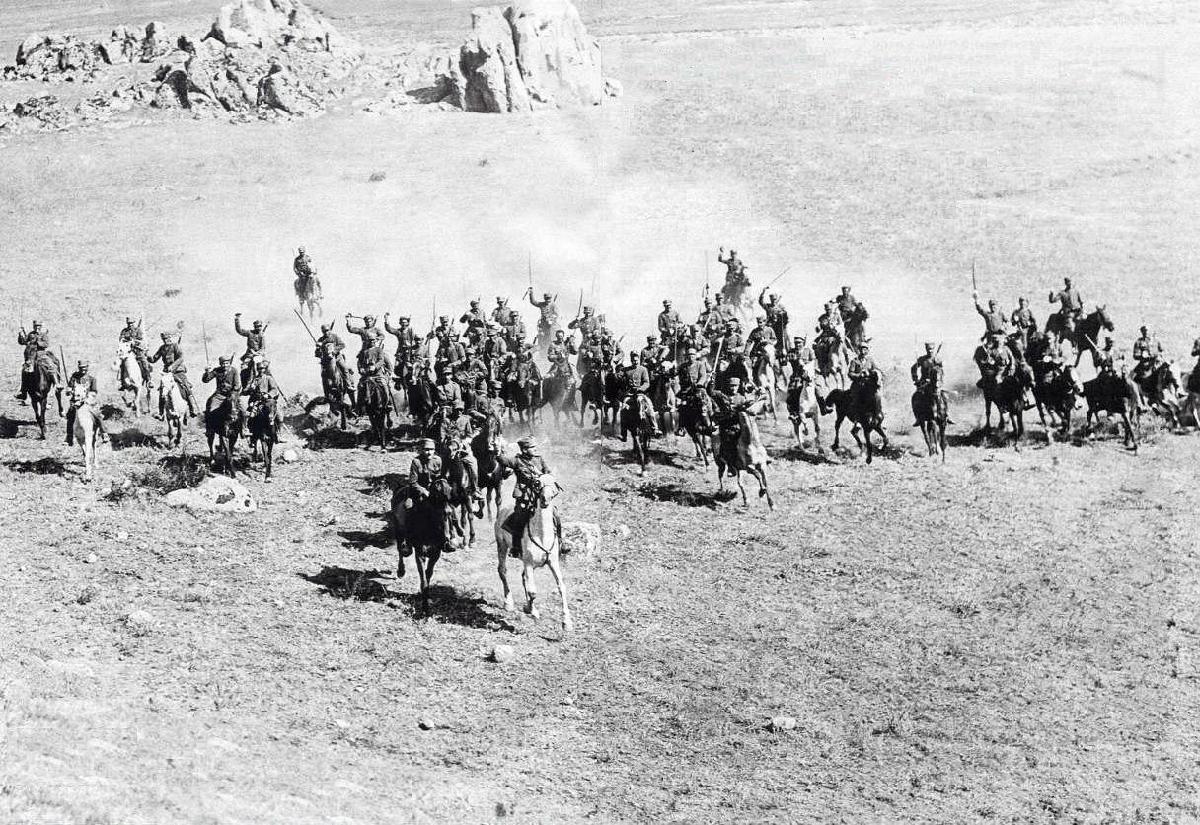

Greek troops stop before

a body of a Turk killed during their march to the Sakarya River

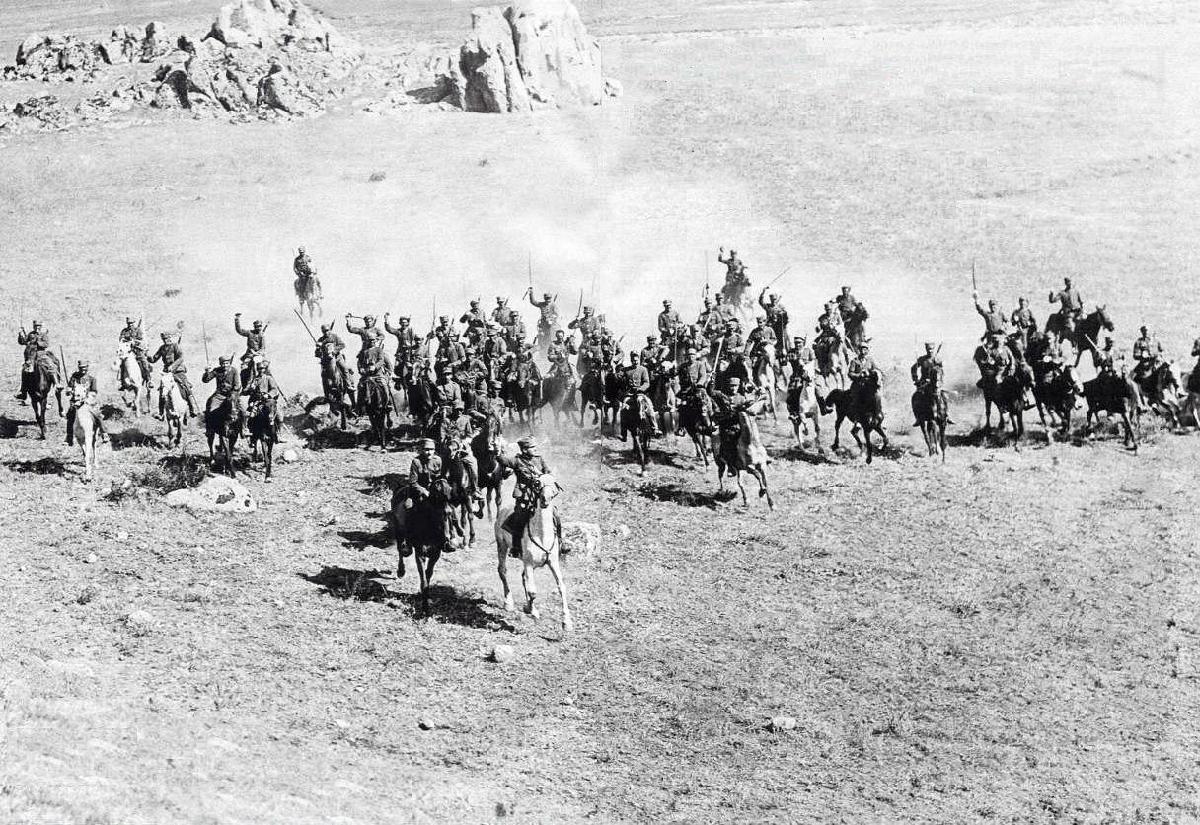

Greek cavalry trying to hold

back a Turkish advance toward the port of Smyrna - Sept. 16, 1922

Greeks fleeing Turkey -

1922

Atatürk then moves on to modernize Turkey.

So completely taken was Turkey by Atatürk’s success, that the Turks

seemed most willing to follow whatever path he seemed to want to take

the country down at this point. And for Atatürk, that meant

modernization … deep modernization.

There was no real

opposition to his ending the Ottoman sultanate and replacing it with a

new Turkish Republic (1922-1923), with himself as the Republic’s new

president (1923-1938), voted there through universal male adult

suffrage … adding women’s suffrage to the dynamic in 1930.

He

also understood that if Turkey were to be able to protect itself fully

from Western intrusions, it was itself going to have to take on Western

ways – economically and culturally as well as politically. That

was not going to please Muslim traditionalists. But at this point

they had nothing to offer in opposition to Atatürk’s reforms.

Thus

Atatürk redesigned the Turkish written language … taking it from an

Arabic alphabet to a Latin-based alphabet. He took on Western

attire (the military had actually already done this) as a civilian

political leader … and extended this same updating in attire to women,

no longer forced to wear Islamic attire. Education would now be

conducted by public educators … rather than by the traditional Muslim

mullahs. And so it went with the "Kemalizing" of Turkey. |

Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881-1938)

and his wife Latife Hanm. Now the undisputed leader,

Ataturk leads the country in a massive secular program of modernizing Turkish society

… something only he could have achieved

because of his huge

popularity | | | | |

The brutal reality facing a post-war

The brutal reality facing a post-war Nationalism versus internationalism

Nationalism versus internationalism

The Russian Civil War (1917-1922)

The Russian Civil War (1917-1922)

The Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921)

The Polish-Soviet War (1919-1921)

The Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)

The Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)