14. ATTEMPTS AT RECOVERY (THE 1920s)

THE BIRTH OF FASCISM

Poland

Poland

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 116-120

.

POLAND |

| In

1919, in accordance with the Treaty of Versailles, Poland was once

again a formerly recognized independent nation. The Poles hoped

that this would be the final resolution of a political humiliation

lasting since the country was carved up into pieces awarded to Prussia,

Russia and Austria. Indeed, this hopefully marked the end of a

long period of political decline that had been underway since the early

1600s when Poland was part of a great Eastern European Republic or

Commonwealth which had it allied with Lithuania and which included the

Polish heartland, the Eastern Baltic nations, Ukraine, and substantial

parts of western Russia. Now in 1919, with the goal of restoring

the Polish nation, the huge problem presented itself in that no one

could agree on where exactly the Polish boundaries should now be located Because of the confusion caused by this problem Poland found itself immediately engaged in a series of battles with its neighbors. Leading the Polish military effort was the Polish hero of the Great War, Jozef Pilsudski. The biggest struggle was with Russia – itself caught up in a terrible civil war. At first Pilsudski’s troops were able to reach deep into western Russia and Ukraine. But then as Lenin gained greater control over Russia, the Bolsheviks were better able to turn their attentions to the Polish threat – and pushed the Poles out of Ukraine and Western Russia. But eventually Pilsudski’s exhausted troops were able to halt an equally exhausted Bolshevik advance – providing the opportunity finally to negotiate a line of demarcation between Poland and Russia ... and at the same time to block Lenin's effort to link up militarily with Communist insurrectionists in Germany and elsewhere in Central Europe. Thus the Polish borders were finally recognized internationally by the Treaty of Riga (1921) along a line negotiated by British Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon. Pilsudski and his officers had hoped for better. But the political leaders of the Polish Republic were content – stirring feelings of hostility between the Polish military and Polish civilian leaders. The next five years was a time in which Poland attempted to discover what it truly meant to be a modern republic – and largely failed. The country was split politically into a number of contending power groups, and corruption within the ranks of the government was widespread. And the military was unwilling to submit itself to civilian authority. The blow finally came in 1926 when Pilsudski led a military coup overthrowing the civilian government – and Poland entered into a period of tight-fisted dictatorship under Pilsudski that lasted until his death in 1935. Some degree of unity was forced on Poland, and it did undergo some economic growth – though not nearly at the rate that its population was growing. Also it lived a very precarious existence squeezed between two naturally hostile powers, Germany and Russia. Non-aggression pacts were signed with both countries. But as events would soon prove, these pacts were meaningless. |

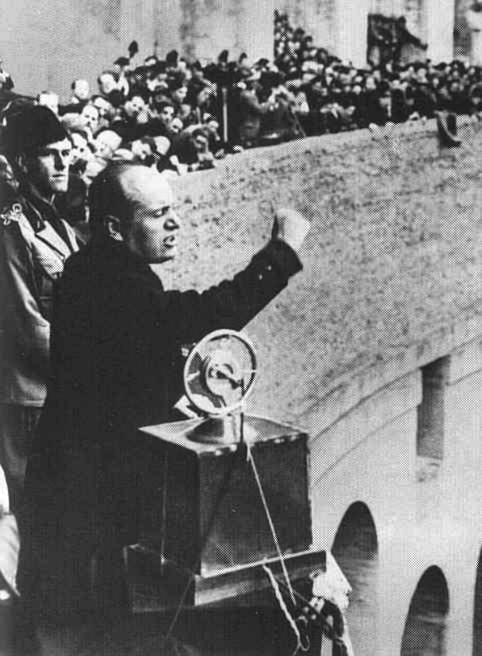

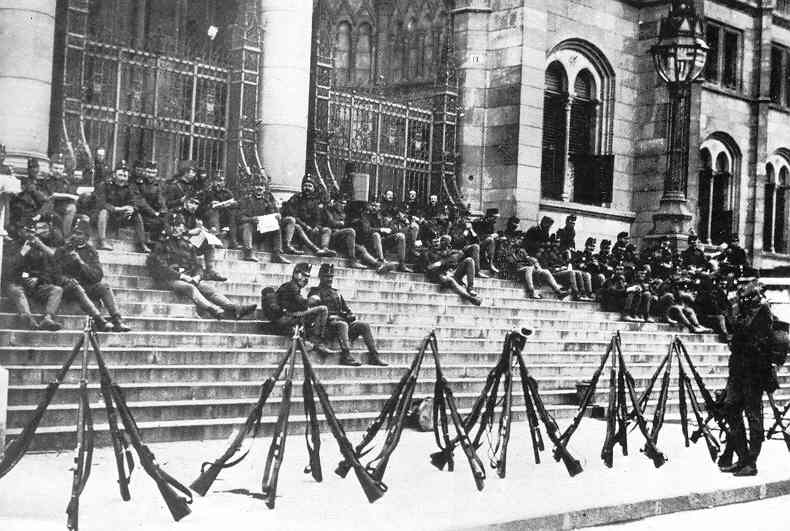

HUNGARY |

| But the colonistsWhen

the newly instituted Hungarian Republic (carved out of the former

Austro-Hungarian Empire) proved unable to protect itself from the

seizing of Hungarian territory by its new neighbors Poland,

Czechoslovakia and Romania, the Communists took over the

government. The Communist leader Béla Kun, a close friend

of Lenin’s, attempted to reorganize Hungary along Soviet lines ... but

succeeded only in throwing the economy into massive inflation and

disarray. He then in the summer of 1919 attempted to carry the

Communist challenge into Rumania ... but in realizing his motives much

of his army deserted and the Rumanians drove his weakened army into

humiliating retreat. This soon undercut the last of his support

in Budapest and he and other Communist leaders were forced to flee

Hungary. This in turn inspired a campaign of violence (the 'White Terror') against Communists ... but also against leftist Socialists and even Jews ...when Hungarian war hero Admiral Miklós Horthy was invited to take control of Hungary as 'Regent.' Horthy took the side of social-political conservatism and soon brought the country under his control, arresting massive numbers of radicals and liberals. He also undid most of the liberal reforms enacted during Kun’s rule, including very importantly Kun’s land reform, turning the land back over to the tiny but highly privileged class of landowners ... and as a result setting up a political controversy that would shake the country during the entire 1920s and 1930s. This in turn drove the Horthy regime deeper into Fascism ... and a second ill-fated alliance with Germany. |

Hungarian communist politician

and journalist Béla Kun (1923). Briefly head of the Hungarian

Soviet Republic (1919)

The Communist revolution in Hungary was actually crushed in 1919 by an invading Romanian army

He took over the country in order to swing it back to traditionalism

YUGOSLAVIA |

| Much

like the other new states carved out of the divided up Austro-Hungarian

Empire, Yugoslavia was itself actually a mix of a number of national

subgroups, the most prominent being the dominant Serbs, but also the

highly national self-aware Croatians and Slovenes (plus the

Montenegrins, Macedonians, Muslim Bosnians, Albanian Kosovars,

Hungarians and others). On top of this, the country was divided

into contending religious groups, 47% Eastern Orthodox, 39% Catholic

and 11% Muslim. Holding it all together was a constitutional monarchy, with the Serbian heir to the throne, Alexander, as king. The democratic aspect of the constitution was truly beyond the comprehension of the largely illiterate population and the national legislature in the capital Belgrade (also the Serbian capital) seemed to be responsive to no other interests than its own Serbian agenda. Finally in 1929 King Alexander simply suspended the constitution and attempted to enact social reforms on his own in the hopes of pulling his kingdom together ... then granting the country a new constitution in 1931 which changed very little about how the kingdom was actually governed. Alexander’s attempt to soften the cultural divisions actually seemed only to make them worse, driving the national groups into a stronger defensive posture as they sensed his effort to undercut their spirit of nationalism. When Alexander was assassinated in 1934, his son Peter was too young to take the throne … so a Regency under Alexander’s cousin, Prince Paul, was established. Paul attempted to appease the minority nationalists by granting greater local autonomy ... especially to the most vocal of the national subgroups, the Croats. But this only irritated the Slovenes all the more when the same rights were not immediately extended to them. But then before that challenge could be addressed World War Two intervened, and the political agenda changed drastically.

|