14. ATTEMPTS AT RECOVERY (THE 1920s)

EUROPE TRIES TO REBUILD

The immediate challenges

The immediate challenges

Weimar Germany struggles to get on its

Weimar Germany struggles to get on its

feet

Austria struggles to survive among the

Austria struggles to survive among the

political ruins

The new Republic of Czechoslovakia

The new Republic of Czechoslovakia

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume Two, pages 108-116.

THE IMMEDIATE CHALLENGES |

BRITAIN'S RECOVERY |

| The first years after the end of the war were good times for Britain

economically. The wartime industrial economy had been booming and the

English accumulated wealth ... which after the war was available for

the purchase of goods, which because of the priority of wartime

production, had not been available at that time. Built up demand was

now released on the British economy, helping to keep the British

economy on a continuing roll. Also the wartime destruction on the

continent meant that European nations were not able to meet their own

needs ... and turned to British goods to answer the demand. This too

aided greatly in keeping British industry moving at a time of

conversion from military to civilian production ... and at a time when

millions of British soldiers were returning to civilian life and

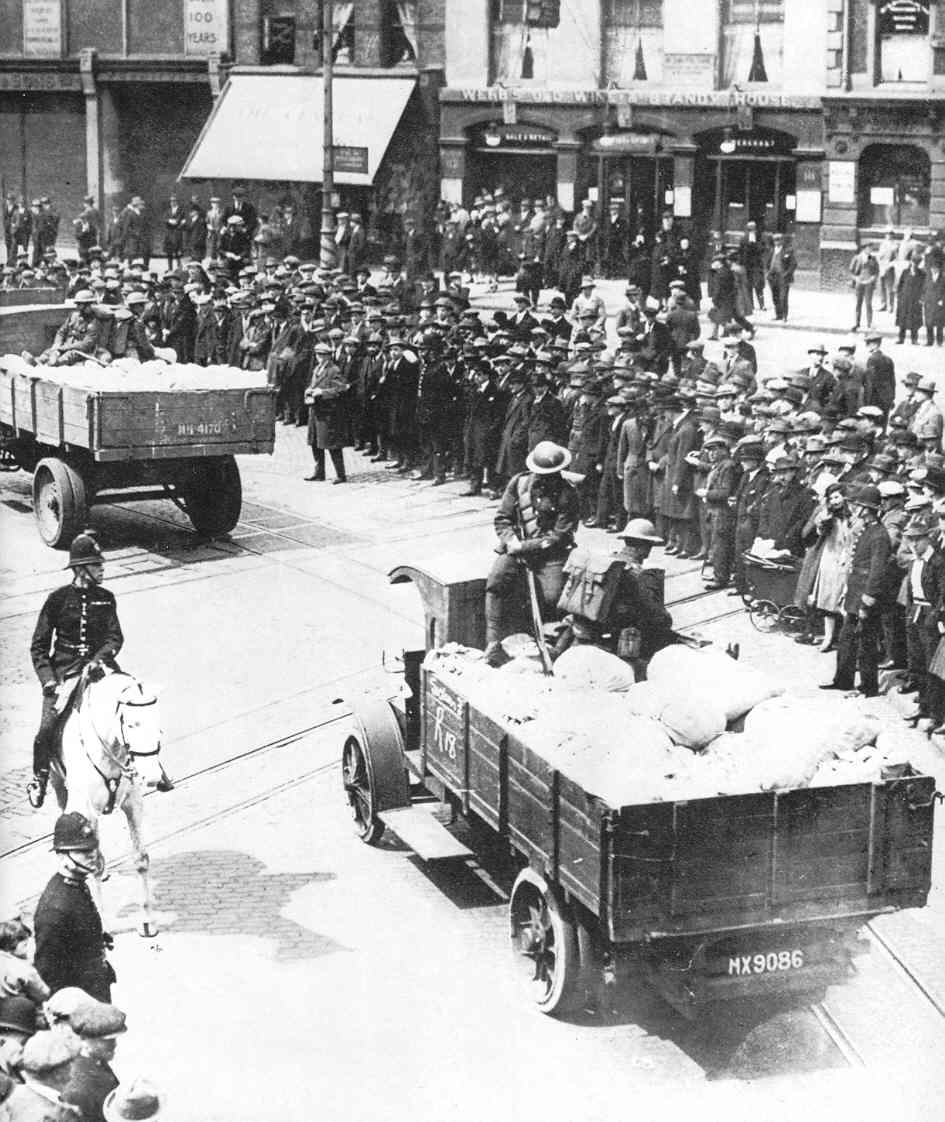

looking for work. Then the British economy slowed down as Europe’s continental nations got their own factories back up and running ... and by 1921 the slowdown was turning into a shutdown of the British export business. For Britain, heavily dependent on the import-export sector of its economy, this was tragic (for instance, three-fourths of Britain’s food came from overseas). There was not an easy remedy to Britain’s economic problems because much of it was based on the fact that in the early 1920s Britain was trying to keep its aged factories moving in competition with the newly built or rebuilt factories coming on line on the continent, employing new machinery and the latest technology. Thus Britain’s immediate postwar advantage of an intact (but aging) industrial system now began to work against it. Also the British coal industry which formerly provided Britain a major part of its overseas income was suffering from the fact that some of the continental nations were substituting oil and hydroelectric power for coal as their primary fuel ... while other nations were opening up coal fields of their own. Unemployment rates thus began to climb perilously high in Britain ... and the British labor movement began to take on a much more angry tone as it searched for explanations and solutions concerning the growing problem. In 1926 a General Strike was called by the British trades unions – shutting down the British economy and causing a fear of a Bolshevik-like workers’ revolution. This merely stirred the British right-wing to an even greater interest in the doctrine of Fascism – threatening to radicalize British politics on both extremes of the political Right and the political Left. Thus during this postwar period the political spectrum in Britain changed deeply. In the 1922 elections the wartime Liberal-Conservative coalition led since 1916 by the Liberal Party leader David Lloyd George went down to defeat and was replaced by a Conservative Party government led by Stanley Baldwin, which lasted only briefly (and which largely ended the glory days of the Whigs or Liberal Party), before having to form a coalition with the rising Labour Party led by Ramsay MacDonald, in order to govern. The Conservative Baldwin and the Labourite MacDonald were to dominate British politics for the next fifteen years ... years of extreme caution given the potential volatility of the political world both at home and abroad. |

The Strike was ended on May 12 and this photo shows the invitation to return to work posted at the Chiswick bus depot. Some employers tried to improve conditions before taking strikers back, or offered worse terms. Many regarded as ring leaders were refused work on any terms.

THE IRISH QUESTION |

| A

major problem troubling deeply the political waters of the British

Empire was the Irish Question. Many of the Irish, after centuries

of mistreatment by the English, had longed for independence from

Britain... and had been promised since even the times of Gladstone in

the late 1800s to be given "home rule." But the promise failed to

be delivered ... until 1914, and even then the necessities of war kept

it from being fully implemented. Thus in 1916 a small incident

exploded into a major Irish uprising on Easter Day in the Irish

capital, Dublin, leading rebels to declare the creation of an Irish

Republic. However, a German promise of aid did not occur and the

Easter Rebellion was put down forcefully by British troops. But

the Irish goal of independence was now fully set in the minds of a

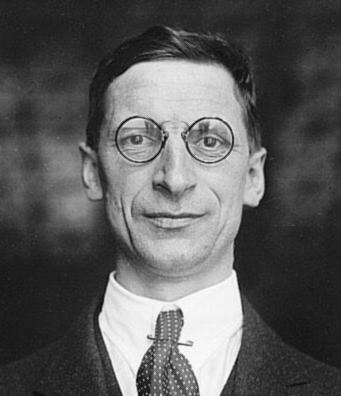

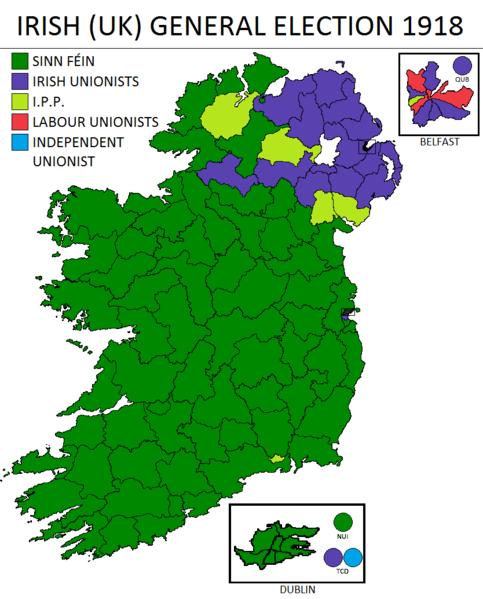

number of active Irish. In the 1918 British parliamentary elections, the Sinn Féin – a newly formed Irish political party under the leadership of Arthur Griffith and American-born Éamon de Valera – won 73 of the 105 seats accorded to the Irish in Parliament. But the Sinn Féin refused to serve in Parliament and instead gathered in Dublin as the foundation of a new Irish national assembly, the Dáil Éireann. The British sent soldiers to Ireland to shut down the Assembly ... and fighting resulted, led on the Irish side by the newly created Irish Republican Army (the IRA) which under the leadership of Michael Collins, took up a fighting style similar to the one used by the Boer commandos of South Africa. Over the next few years the violence intensified, becoming extremely brutal on the part of both the Irish and the British. Finally (1921) with both the British and the Irish exhausted (and the Irish themselves highly divided on this matter of Irish independence) a truce brought the conflict to a relative standstill. A subsequent treaty between the Irish and the British government provided for the creation of an Irish Free State, largely independent and affiliated with the British crown on the same basis as the dominions of Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. But the treaty allowed the six counties of the northern Ulster Province – which were predominantly Protestant in character – to opt out of the Irish Free State if they chose to do so (which they did). With the elections held the following year (1922), Griffith was elected the Free State’s new President and Collins the head of the new Irish military (de Valera refused to be identified with the treaty and abandoned his position of leadership in the Dáil). At this point fighting broke out again ... but this time largely among the Irish themselves. In the course of what was coming to be an extremely bloody civil war, Collins was assassinated in an ambush by radical elements of the IRA ... further enraging the Irish forces supporting the Free State and thus intensifying the civil war even more. In the meantime the Catholic Church placed its support behind the Free State ... as did the majority of the population. And finally, little by little the IRA was forced to give ground to the Free State forces. But de Valera was also losing political ground. He declared himself to be the head of a new Republican government ... made up mostly of the members of the Dáil that had voted against the treaty. But the IRA rejected de Valera’s leadership in favor of the IRA’s own claim to lead the movement toward Republicanism. Finally, de Valera decided to participate in the 1923 elections to the Irish Free State Dáil, helping to settle the conflict somewhat (though he himself was arrested and imprisoned by the British when he dared to campaign openly for election to the Dáil). At the end of that year Ireland became a member of the League of Nations, indicating its new status as a largely independent nation. But Valera, freed from prison in 1924, eventually decided to leave the Sinn Féin Party ... and in 1926 founded the ultra-nationalist Fianna Fáil party. He continued to press the Irish to secure full independence from Britain as an Irish Republic ... which he insisted must also include the six counties of the northern (and largely Protestant) Ulster province. Thus deep political tensions (and occasional violence) would continue on into the 1930s. Nonetheless, the Irish Free State seemed finally to have secured itself on fairly strong political footings in Ireland ... at least for the time being. |

With the end of the Great War and the promise of Wilson of the right of "self-determination"

of all peoples, the Irish quest for independence from England gathers new momentum

Arthur Griffith Arthur Griffith

|

Seán Hogan's

Flying Column, 3rd Tipperary Brigade, IRA

FRANCE STRUGGLES TO REBUILD |

|

The ravages of war in France

After World War One France was plagued by deep internal political conflicts and a general spiritual exhaustion. Though supposedly because of France's "victory" (represented in the Versailles Treaty) it should have been cheered by the outcome of the war, the war had been outrageously costly in terms of lost life and material resources. The ten northern departments of France, the formerly most active industrial part of the country, had been laid waste by the war. Hundreds of towns were simply a pile of rubble. The countryside was laced with trenches and laden with shell holes (and dangerous, unexploded ordnance). Coal mines had been flooded, dynamited, filled with waste or even set ablaze, and steel mills and textile factories destroyed by the Germans. And of the nearly 8 million Frenchmen who had served in the French military, nearly 1.5 million of them had been killed or were missing and another 1.5 million of them seriously wounded. And overall, the French population during the war years dropped from 41.6 million to 38.6 million. As far as the French were concerned, the Germans were going to have to pay dearly for what they did to France. The fact that Germany itself was economically a disaster and thus unlikely to be able to meet that demand was to the French besides the point. They must pay. The post-war splintering of French politics

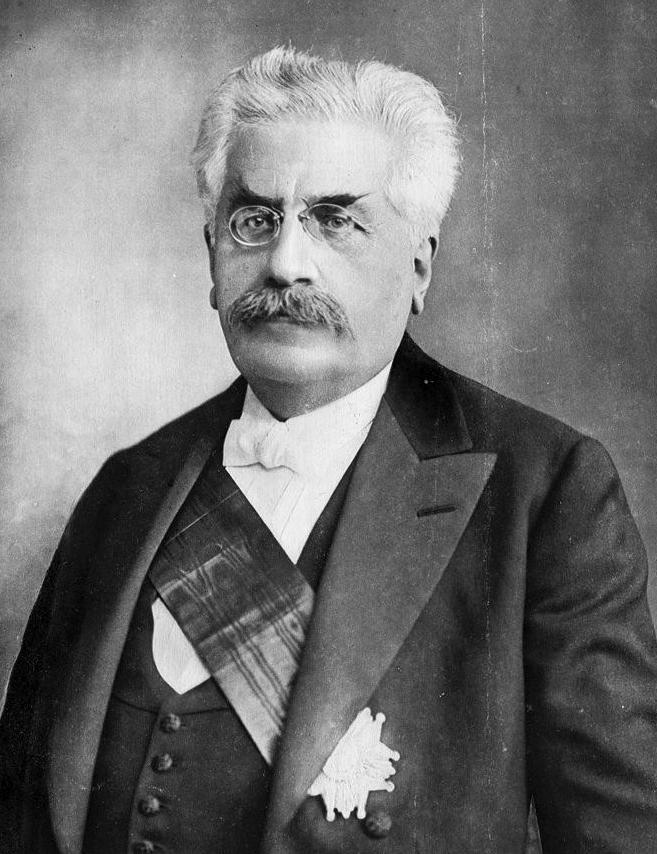

Also, France was so shaken up by the war morally and intellectually that it was not sure what ideas or symbols to rebuild its post-war national honor around. The conservative political organization Action Française wanted the French Orléanist monarchy and Catholic Church restored to their former places of glory – believing that France's lack of decisive victory was due to the weakness of Republican political principles. On the other side of the French political spectrum (the "Left"), the large socialist political organization was itself split deeply. The Socialists, who had originally supported the war (much to the distress of the Marxist purists on the left wing of the party), found themselves discredited by the war. War weariness and the generally deplorable lot of the French worker after the war came to haunt the Socialists for their earlier patriotic enthusiasm. In 1920 left-wing Socialists split deeply over how to react to Lenin and Trotsky's Communist revolution in Russia – which many Socialists claimed was not truly Marxist, but merely opportunist. Nonetheless, the majority of the Socialists decided in 1920 to align themselves with Lenin's new "International" and reformed themselves as the French Communist Party. One of the disturbing facets of this new French Communist Party was how extensively they then took their political cues from Lenin's Bolshevik Communists in Russia. There were many other strongly-held political viewpoints astir in France: the Radical -Socialists, who were in fact rather centrist (on the left) and the somewhat militarily oriented Croix-de-Feu which was strongly conservative (monarchist and Catholic), but Bonapartist in sentiments and thus strongly opposed to Action Française. Occupying something of the 'center' of this widely split political spectrum, the French ‘Radicals’ – in coalition with other small centrist parties and by the remnants of the old French Socialist Party – actually supplied France with most of its prime ministers after the war (e.g.. Poincaré, Herriot, Daladier). Rebuilding the French economy

Because of the huge expense of the war the French government found itself deeply in debt. The hope was that German reparation payments might be a major solution to the problem ... but those payments were never seriously forthcoming, not anywhere to the extent the French had hoped for anyway. The French franc fell perilously ... not to the extent of the German mark, but at least to the point that it was worth only a couple of cents (American) by 1926. Wartime leader Poincaré was brought out of retirement, he put the government under tight financial discipline, and by early 1927 the French economy seemed to be stabilizing. Indeed the French economy began to pick up as business orders and tourism grew to prewar levels. Then the Great Depression hit over the winter of 1929-1930

At first it looked as if France might escape its grip ... but by 1931 the French economy was slipping into the Depression as well. The next few years would be extremely tough for France economically. |

Raymond Poincaré – French President (1913-1920) and French Prime Minister (1922-1924 and 1926-1929). In 1923 he ordered the French military occupation of the Rhineland to force the Germans to make the reparations payments to France required in the Versailles Treaty.

French military occupation of the German industrial Rhineland (beginning in 1923)

WEIMAR GERMANY STRUGGLES TO GET ON ITS FEET |

|

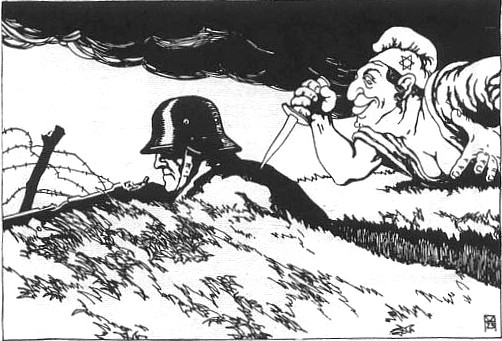

The Dolchstoßlegende (stab-in-the-back myth)

Germany had been spared the chaos of the post-war Russia. But the economic situation in Germany was grim. Unemployment was widespread, mass starvation was threatening (the British, despite the armistice, insisted on maintaining the blockade against food imports to Germany until a full peace treaty could be signed) and the new Republic inspired very little loyalty among the German people. The strong German military spirit, not an up-swelling of some kind of a German democratic spirit, is what held Germany together. Indeed, the notion began to build quickly in Germany that "our army did not lose the war" ... but instead they had been 'stabbed in the back': sold out to their enemies by German traitors who had been much too quick to agree to the humiliating terms of the November 1918 Armistice. The fact that a large number of Jews could be found within the ranks of the Socialists responsible for signing the Armistice and setting up the new Weimar Republic only made the notion of a horrendous Jewish 'conspiracy' all the more believable to the average German. An additional part of the theory was that the Socialist leaders had also been 'bought out' by international financial capitalists ... among which also Jews were found in great number. This Jewish conspiracy made a great deal of sense to a number of Germans who saw their world turned upside down in just a matter of months following the signing of the Armistice. To them a conspiracy on a massive scale could be the only explanation for such a turn of events. Inflation and devaluation of the mark

To make matters even worse, the German mark, the very foundation of the German financial order, had been losing value rapidly as more marks were being printed, first to meet wartime needs, then post-war industrialists’ investment needs and workers’ salary demands, and finally to meet reparations requirements imposed by the Versailles Treaty. During the period from the end of the war to the first half of 1922 the mark went from four to the dollar to over 300 to the dollar. Attempts were made by a reparations commission in June 1922 to find a solution to the growing German insolvency – but none was forthcoming. At that point the German mark collapsed in value with such a runaway inflation that the mark was valued at 8000 per dollar by December. When in January of 1923 Germany announced that it could not continue to make reparation payments, French and Belgian troops entered the German industrial region of the Ruhr to seize the industrial assets of Germany. They were determined to ensure that reparations payments were made in goods rather than in worthless German marks. This move in turn was met by general strikes of the German workers – which only drove the German economy further into the ground. By the fall of 1923 the value of the mark was less than the cost of the paper it was printed on. Finally in November of 1923 a new revalued mark, the Rentenmark, was introduced – by cutting 12 zeros off the denomination: the mark thus went from 4,200,000,000,000 to the dollar to 4.2 to the dollar. The German currency eventually stabilized. The inflationary spiral was over. But in the process all German pensions and savings accounts had been completely ruined. Germans were having to start their savings over again from point zero. Though the Germans were relieved to be finished with the inflation there was deep resentment against those who Germans were certain had conspired to cause this ruin: foreigners designing to destroy Germany, notably foreign bankers, and especially Jews (many of the leading international bankers of the day were Jewish). Of course this also made the Weimar Republic itself look to many as being totally useless, if not even part of the anti-German conspiracy. On-going social strife

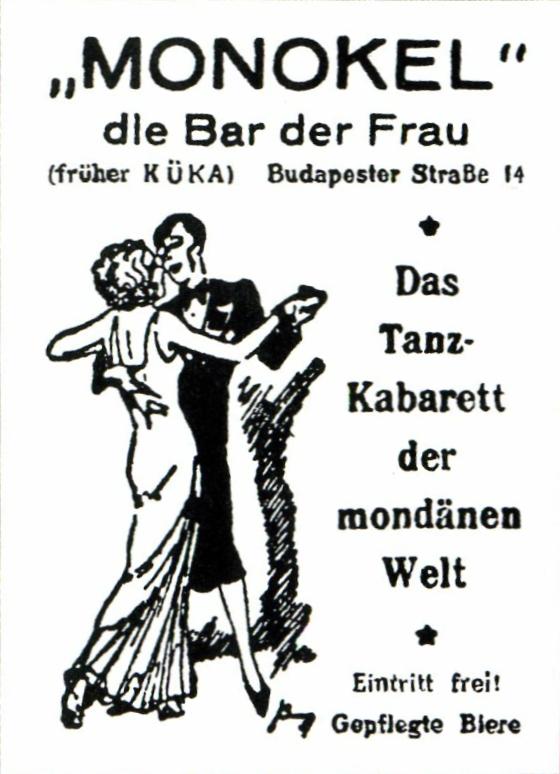

In those hard years after the war Germany struggled to avoid social collapse. The Left-wing socialist and communist paramilitary Red Guard and the Right-wing super-nationalist Freikorps battled with each other in the streets, catching innocent citizens in the brutal crossfire. General strikes were called by Leftist labor organizers and produced not better working conditions but merely crippled a German economy struggling to get back on its feet. Unsuccessful attempts were made to take over one or another of the smaller states comprising the German union – further shaking the German social order. A widening moral-social divide

Eventually things settled down for Germany as the 1920s rolled along. Rural life in Germany recovered sufficiently so that it was finally able to take on its more traditional character. Urban life however looked in a different direction as life settled in. Urban Germany was excited about the new life-style offerings of post-war industry and commerce. New material goods such as cars, radios, home appliances – plus the exciting distractions of movies and cabarets – seemed to point to the opening up of a wonderful new world (which rural Germany did not fully understand or admire). Traditional moral standards gave way as urban Germany experimented with new cultural ideas and behavior. Urban Germany was not prudish to begin with ... but its sexual freedoms would become particularly bold and challenging – as traditional Germany understood how things were supposed to be. Later Hitler would play heavily on this moral divide, targeting particularly the rampant homosexuality that seemed to infect urban Germany (particularly Berlin), making himself even more popular with rural and small-town Germany in the process. Also the migration into Germany of Jews from the East (principally from Russia and Poland) would play into this widening moral divide as this migration would become a major irritant to German national feelings. Jews had long suffered in Russia and Poland as a distinct religious minority in that they were never allowed to secure stable property rights ... and thus were forced to invest their assets in things other than land: notably gold, jewelry and other mobile valuables. With the increase of the persecution of Jews during the heat of rising nationalism in Russia and Poland before and during the war, this mobility of Jewish wealth actually made it much easier for the Jews to make the decision to finally abandon their homes and head west. Germany was a natural destination ... as most of them spoke Yiddish (actually Jüdisch) a German dialect, making assimilation into Germany a relatively easy move. In arriving in Germany, they were able to use their mobile assets to purchase German businesses that had fallen on hard times, engendering a deep bitterness among Germans who saw their neighbors lose their businesses to these Jewish intruders. It all seemed like further proof of a grand Jewish conspiracy to undermine Germany. Here too Hitler would play on these feelings to promote himself and his fiercely anti-Jewish Nazi program among bitter Germans. |

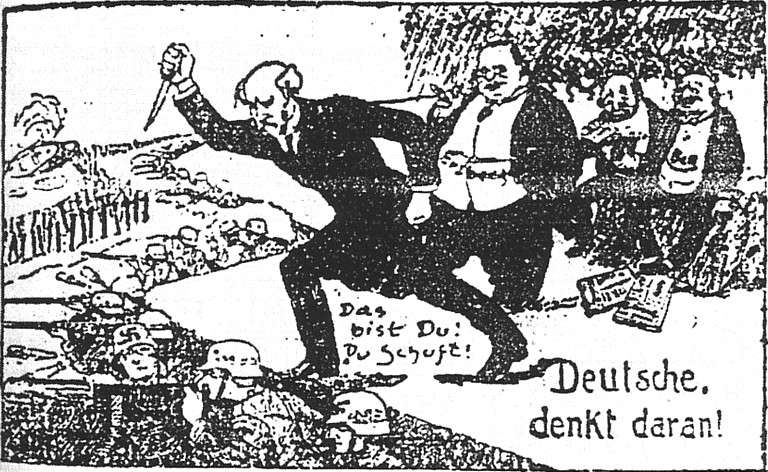

Jews (who were numerous among the Socialists) came in for special blame for the chaos ... and "sellout" to Germany's enemies. The Jews had "stabbed Germany in the back" ... thus the Dolchstosslegende (stab-in-the-back myth) that many – and most notably Hitler – would exploit politically to the fullest.

A 1919 post-card illustrated with the "stab-in-the-back" theme. Notice the stereotyped Jew with the

dagger

| A crude 1924 cartoon showing Philipp Scheidemann, the German Social Democrat who declared the creation of the Weimar Republic and who became its second Chancellor, backstabbing hapless German troops (note the Nazi insignias on the helmets). Behind him stands Matthias Erzberger, a Center Party leader who signed the Armistice with the Allies. And behind them sit international financiers with their money ... again, presumably Jewish. |

Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert1919-1925

1925-1933

German 50 million Mark banknote

printed on September 1, 1923 and worth about $1 at the time. The back side was left

blank to keep printing costs down.

A few weeks later it would be

totally worthless.

The Germans attempt to rebuild something of a military reput ation ... despite the severe limits placed on them by the Versailles Treaty

General Hans von Seeckt, who masterminded the secret treaty

by which Germany and Russia trained and equipped each other's growing armies in violation of the

Versailles Treaty limiting Germany to a 100,000-man army.

This also fortified the German military

as an independently-operating state within the state.

General Hans von Seekt, architect

of the post-war Reichswehr. He trained a very professional

German officer corps – despite Versailles limitations

German make-believe tank with cardboard armor – "conforming" to Versailles restrictions

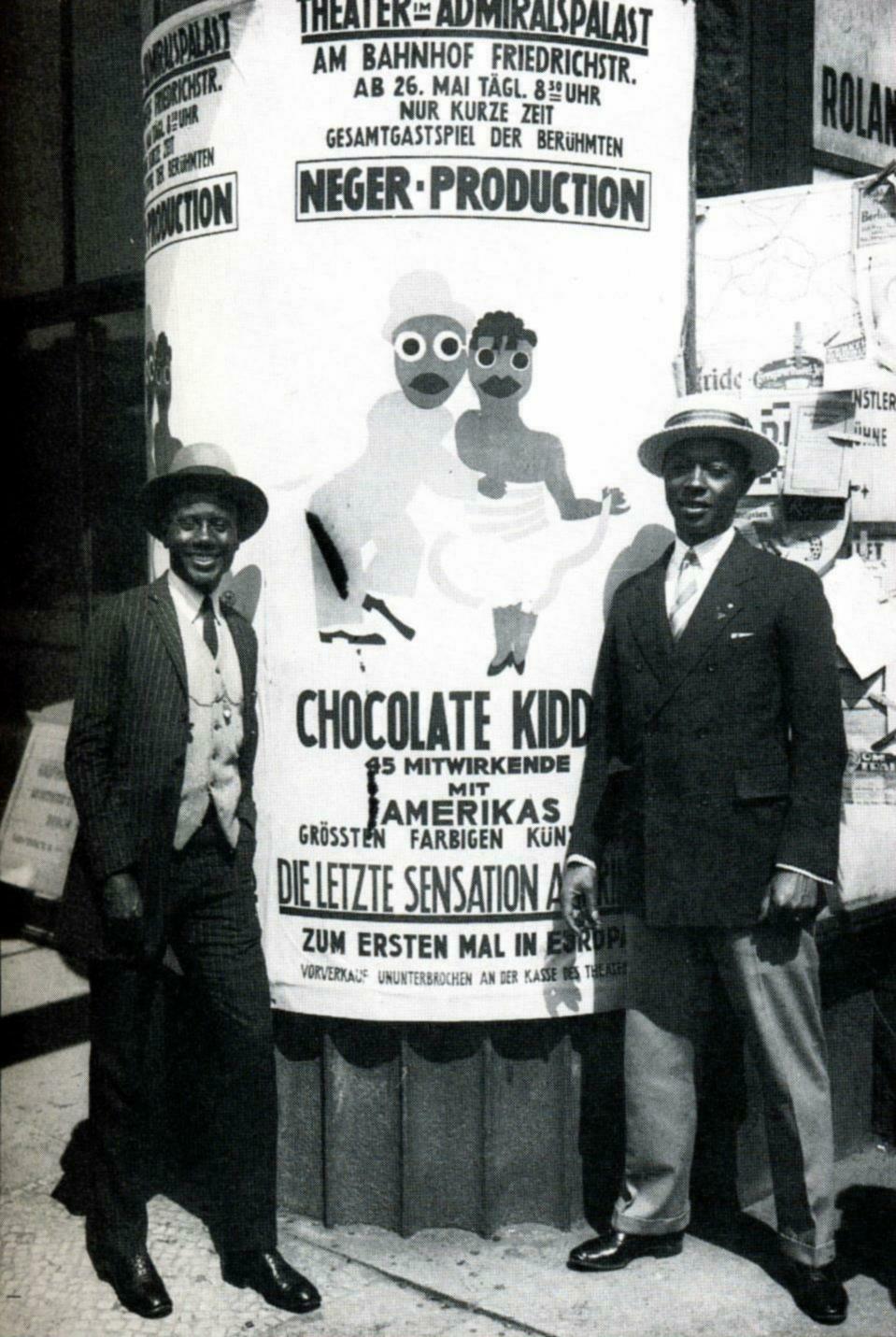

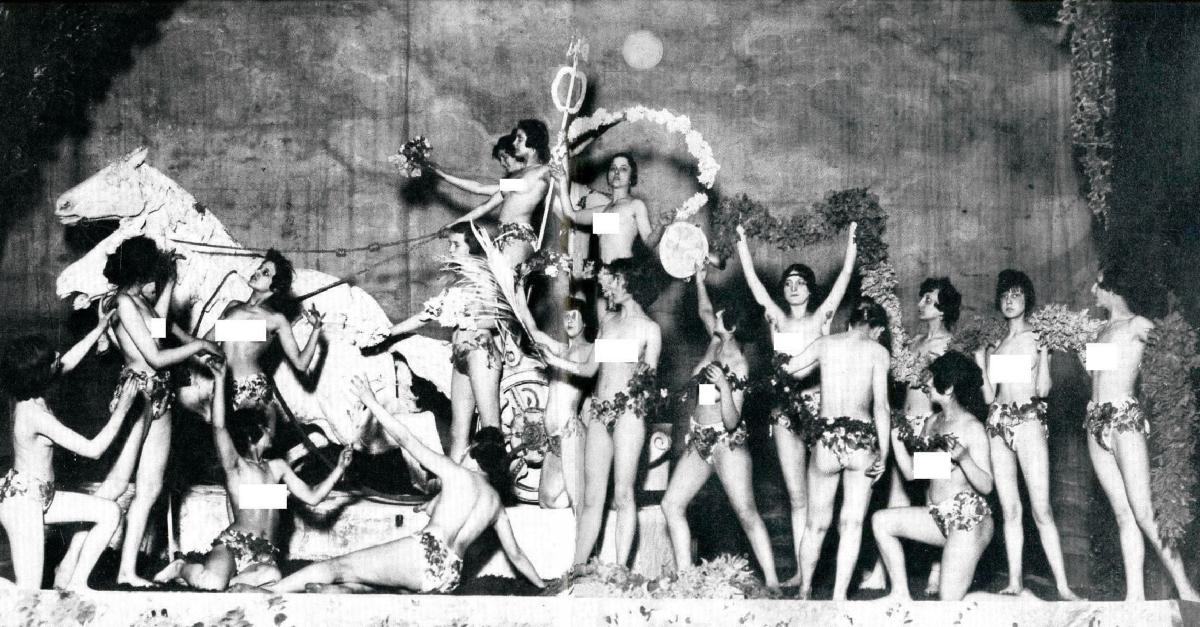

Berlin becomes noted for its wild abandon – its dizzying decadence

The girls of Berlin's Apollo

Theater forming a topless "tableau" in imitation of the victory

statues atop Berlin's Brandenburg Gate

AUSTRIA STRUGGLES TO SURVIVE AMONG THE POLITICAL RUINS |

| With

the rise of nationalism in the late 1800s it had been a huge challenge

of the Habsburg Eastern Empire (Österreich) or Dual Monarchy of

Austria-Hungary simply to survive the many challenges to its existence

posed by the independence movements of the various national groups

making up its existence. Then with Wilson’s goal of seeing ‘the

rights of national self-determination of peoples’ (self-government)

extended everywhere across the world (but particularly throughout the

empires of the enemy nations Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey)

Austria-Hungary’s fate was sealed with its ‘defeat’ in the Great

War. National groups came to Versailles to press their case for

independence ... and were very quickly recognized as having a just

claim to independence. Thus when the carving up of the Habsburg

empire was completed, there was very little left geographically of what

was to carry on as ‘Austria.’ And what was left was heavily

mountainous and devoid of much by way of natural assets. And her

economy, once built around the empire’s once huge internal trade zone,

now found itself cut off from those same markets by tariff barriers

erected by the newly independent nations once making up her

empire. Economically, survival looked nearly impossible for the

little rump state left over from the carve-up. There was some thought of simply linking German-speaking Austria to the new German Weimar Republic ... but that idea was shot down by the Allies’ fear of adding strength to a Germany which was supposed to be put under very tight oversight, to ensure that its Hunnic instinct would never rise again. Indeed in the Versailles Treaty such union (Anschluss) of the two German states was strictly forbidden except by express permission of the League of Nations... which was very unlikely ever to occur. Reparations had been imposed on the new Austrian Republic (similar to though not of the same scale as those imposed on Germany) and as with Germany had invited an inflation that by 1922 had nearly bankrupted the new republic. The League agreed to suspend the reparations payments ... and the currency began to stabilize. The economy began to then pick up. But politically Austria seemed unable to bridge an ideological gap that separated the Social Democrats from the Christian Socialists. The former were strongly supported by an urban-based industrial workers movement of the Marxist variety, whereas the latter represented the conservative interests of the Austrian countryside. The rivalry grew so bitter that Austria could never find a middle ground politically on which to move ahead. Then with the economic crisis of the early 1930s the confusion worsened ... with a rising group of Austrian Fascists pressing for union with Hitler’s Nazi Germany ... and with both the Christian Socialists and the Social Democrats fervently opposed. Engelbert Dollfuss served as the head of the Christian Social Party and became head of a coalition government in 1932 - but with such a slim majority that it made his position very shaky. Voting irregularities in the following year caused the coalition to collapse. But Dollfuss convinced the Austrian President, Miklas, to let him rule without parliament - as virtual dictator - pointing out the threat of a German Nazi takeover of Austria as the alternative (the Nazis were gaining popularity rapidly in Austria at this time). However in 1934, Dollfuss was assassinated in an attempted German Nazi takeover of Austria, the "July Putsch." His assassins were arrested and the coup was thus thwarted. Dr. Kurt von Schuschnigg took over the office of Chancellor after Dolfuss's assassination and in 1935 was able to disband the Heimwehr, a paramilitary group similar to the Nazis, in an effort to get Austria settled down. But Schuschnigg was ultimately unable to hold back the rising Nazi spirit demanding the Anschluss (joining or uniting) with Hitler’s Germany. Thus heading into the latter 1930s, Austria was facing a crisis it could not seem to overcome.

Go on to the next section: The Birth of European Fascism

|