4. THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC

THE FINAL PRODUCT

| CONTENTS

The process of coming to an agreement The process of coming to an agreement

A Federation replaces the Confederation A Federation replaces the Confederation

A government that draws its powers from A government that draws its powers from

the people – not vice versa

What were the guarantees that this would What were the guarantees that this would

work?

The Federalist Papers and the process of The Federalist Papers and the process of

ratification

The geographic redesign of the Union The geographic redesign of the Union

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 156-173.

|

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1780s |

The American Union's new Republic (1787)

1787 A Convention of the various state representatives meets during a long hot summer in Philadelphia (May-Sep), debating the interests of the small states (equal representation of all states vested in the New Jersey Plan) versus the interest of the large states (proportional representation according to population size vested in the Virginia Plan)

With debate

largely deadlocked between the contending interests, the American sage,

Ben Franklin, in late June, calls for daily meetings to begin in prayer, to get the

representatives to think higher than merely their own

state's political interests ... reminding them that God had plans for

America that had nothing to do with their respective political interests

Roger Sherman's "Connecticut Compromise (or "Great Compromise") is

gradually (Jul) accepted, finally opening the

way finally to the drafting of a Constitution for the new Federal Union

The Continental

Congress meanwhile passes the Northwest Ordinance (Jul) setting up

plans for a number of slave-free

states, eventually to become members of the new Federal Union

1788 Federalists (nationalists) and Anti-Federalists (states-righters) debate constitutional ratification; Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay write The Federalist Papers, (some 85 articles) advocating ratification

The Federalists

carry the day, bringing the new Constitution to ratification (summer)

|

THE PROCESS OF COMING TO AN AGREEMENT |

|

A

note of caution here

It is extremely important to note that the

delegates who gathered in Philadelphia to devise a new political

formula for the purpose of a closer political union among the thirteen

states, were not (like the French) inexperienced in republican

self-government. Not only had Americans been operating for years under

the Confederation government, but the states these delegates

represented had already put into effect their own constitutions as

independent states. Thus each of them had a pretty good idea of what

American government was to look like, at least in principle.

Indeed, Americans had been practicing some form or

other of constitutional self-government since their ancestors put

England behind them in coming to America, some century and a half

earlier.1

Thus it is important to note that these Founding

Fathers of the late 1700s were not inventing self-government. They

already understood quite well the principles involved in effective

self-government. Rather, they were trying to figure out a formula for

collective self-government that would allow them to continue to work

together as a union at a level higher than each newly independent

state.

They were not naive (like the French, and like

many Americans today), believing that some utopian formula discovered

by some political genius among them was what they needed. Rather, they

knew that each delegate that gathered there had a somewhat different

political agenda he would be pursuing – and they were going to have to

work together in full respect of those different agendas or interests

if together they were going to find the necessary common ground on

which to build a new union government.

With the benefit of considerable political

experience, and with God's counsel opening their hearts to each other,

they would succeed.

In short, American government itself was not

birthed in 1787 – as we so often tend to imply when we talk about the

birth of the Republic that year. Actually, long-standing traditions in

American government were simply adjusted to meet the ever-clearer needs

for a more effective union among the thirteen newly independent states.

Divergent interests

By no means did the

fifty-five delegates who gathered in Philadelphia at the end of May in

1787 have the same idea, some widely agreed upon logic, as to what was

supposed to result from their work. They represented not only a wide

array of states, big and small, but also different life-styles (major

plantation owners, prosperous urban tradesmen, lawyers, etc.). The

states they represented also found themselves in deep contention about

how exactly their particular borders extended to the West beyond the

Appalachian Mountains. And most important, they held very different

ideas about what kind of government reforms they wanted to see take

place.

Federalists and Anti-Federalists

Some like

Washington, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison were

strong nationalists or Federalists who were hoping to see a much

stronger political hand holding the thirteen states together. But

others who came to Philadelphia were of the opposite opinion, thus

strongly Anti-Federalist, fearing that just such a political union

would usurp the very freedoms they had so recently fought to secure

against the ambitions of the English King George III. In fact, major

figures in the recent War of Independence, such as Samuel Adams and

Patrick Henry had refused to participate in the Convention, fearing

that it would saddle them with just such a government. Likewise, the

tiny state of Rhode Island did not even bother to send participants to

the meeting, fearing the loss of their independence to the interests of

the larger states such as Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania and

Virginia.

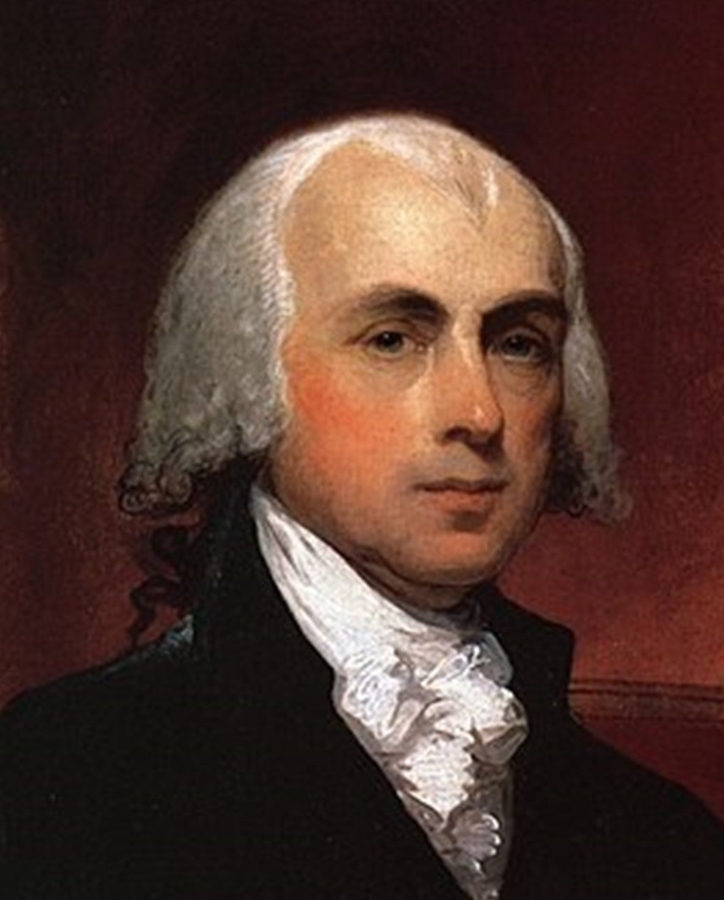

The Virginia Plan

Almost immediately upon arrival to Philadelphia the delegates set aside

the idea of merely amending the Articles of Confederation. Indeed,

James Madison had busied himself in drafting up a proposal before the

Convention had even convened. His proposal set out some basic

principles which pointed to a national government with a number of

strong powers, which his own Virginia delegation and the Pennsylvania

delegation were quick to agree on, thus giving it considerable weight.

Indeed his Virginia Plan was put forward at the Convention as the

opening document, calling up countering documents, or at least offering

itself as a document to which amendments and details could then be

added.

Almost immediately upon arrival to Philadelphia the delegates set aside

the idea of merely amending the Articles of Confederation. Indeed,

James Madison had busied himself in drafting up a proposal before the

Convention had even convened. His proposal set out some basic

principles which pointed to a national government with a number of

strong powers, which his own Virginia delegation and the Pennsylvania

delegation were quick to agree on, thus giving it considerable weight.

Indeed his Virginia Plan was put forward at the Convention as the

opening document, calling up countering documents, or at least offering

itself as a document to which amendments and details could then be

added.

His Virginia Plan provided for a bicameral

legislature of two separate bodies, an upper and a lower house, on the

order of the English Parliament with its House of Lords and House of

Commons, a principle followed as well in the design of the governments

of most of the individual states. In this it departed from the

Confederation's single or unicameral assembly (the Continental

Congress), which had demonstrated how a unicameral legislature tended

to be easily susceptible to the swings of political mood which

accompanied popular politics (politics of the people). The hope was

that a second legislative body could counterbalance the passions of a

popular assembly because, like the English House of Lords, the second

body would be expected to be made up of a smaller group of more

distinguished statesmen. However, how that group might be chosen was

left open as a key question.

Also Madison's Virginia Plan provided for a

stronger, more independent executive, not quite like a king but

stronger than the executives of the Confederation – and many of the

states – who were largely dependent on the legislative bodies for their

powers, and thus lacking in any significant power to direct and lead

the nation. Anyway, most of the delegates were expecting Washington to

head up the new government, and it was important to assign him

sufficient powers and independence of action to bring his talents to

full service to the country. But the question remained: was he to be

the sole executive (and thus more like a king) or was he to share his

function with one or two others (as was done anciently)? What would be

his term of service: serving for life (and thus indeed like a king), or

elected, and probably re-elected, annually or for periods of greater

length?

And there was the matter of the judiciary or body

of judges, who by English tradition were extensions of the king's

authority. Efforts of the states to make their judges instead dependent

on the appointive powers of the legislatures had produced less than

distinguished judges, and elements of well-known political corruption.

How such judges should be selected was thus a major problem that

brought on much debate.

The debate begins

The first issue to come

under heated debate was the selection of the representatives to the new

Congress. The Virginia Plan assumed that the size of the representation

in Congress (both upper and lower houses) would be on the basis of the

number of voters in each state, which would clearly give the bigger

states a dominant voice in the new government. But Virginia seemed

willing to listen to some kind of compromise that would bring the

states together in their thinking.

1The royal charters of the 1600s that birthed each of the American colonies

were themselves "constitutions" of sorts, describing precisely the

purposes and practices that the colonies were to live by.

| The smaller states were hoping for equal

representation by the states, irrespective of size. Representing the

interests of the smaller states, the New Jersey delegates thus offered

a counter-proposal to the Virginia Plan which called for the continuing

existence of the Continental Congress as a single unicameral body, with

each member state holding equal representation, despite the size, large

or small, of each state.2 But it would be given new powers such as in

the collecting of taxes and the power to override the state laws. This

gave the smaller states a rallying point to put forward their political

interests. But overall it was an idea that the larger states clearly

were unwilling to accept.

The Connecticut Compromise

Then Roger Sherman of Connecticut offered an idea supporting the

Virginia Plan's call for a bicameral Congress, but with one chamber

(the House of Representatives) giving the states representation on the

basis of the relative size of their population, but the second chamber

(the Senate) giving each of the states equal representation (desired by

the smaller states). At first Sherman's idea was rejected, as the

states large and small were holding out in protection of their

respective political interests.3 Also there were other issues that

undermined the spirit of compromise necessary to break the political

impasse.

Then Roger Sherman of Connecticut offered an idea supporting the

Virginia Plan's call for a bicameral Congress, but with one chamber

(the House of Representatives) giving the states representation on the

basis of the relative size of their population, but the second chamber

(the Senate) giving each of the states equal representation (desired by

the smaller states). At first Sherman's idea was rejected, as the

states large and small were holding out in protection of their

respective political interests.3 Also there were other issues that

undermined the spirit of compromise necessary to break the political

impasse.

One of the issues that would long stir turmoil in

the new Republic was this matter of slavery. Almost half of the

delegates to the Convention (and all of the Virginia and South Carolina

delegates) were slave owners. But in general Northerners tended to be

adamantly opposed to the idea and practice of slavery; indeed many of

the Northern states had included a total prohibition of slavery in

their new state constitutions. But Southerners could not bring

themselves to imagine seriously a Southern economy able to function

without slavery. Some made it clear that they would not join the new

Union if slavery were somehow disallowed.

Moreover, the Southern states were adamant on the

matter of including their slaves in the calculation of the

representation in the House of Representatives. But Northerners were

quick to point out that slaves weren't citizens. Thus should they be

counted at all? Some Northerners even quipped that since slaves had

merely the status of property rather than of free citizen, Northern

cattle should be added to the count for the Northern representation in

the House of Representatives!4

Ultimately another compromise was eventually reached when it was decided that slaves should count as three-fifths of a person!

Anyway, most of the Southern Framers were of the

opinion that slavery would soon die a natural death, though they had no

idea of how that might happen. And so they basically dodged the issue –

and would continue to do so until it blew up in their faces in the

early 1860s.

2The

Continental Congress which had guided the 13 states during the War of

Independence had given each state simply a single vote, regardless of

the number of individuals – usually two to six or seven – a state had

representing it in Congress.

3It

was at this point that Franklin asked the Convention to bring God into

its deliberations as a means of transcending their deep differences.

4Indians were never part of the count!

A FEDERATION REPLACES THE CONFEDERATION |

Signing the Constitution

of the United States – by Howard Chandler Christy

Architect of the Capitol

The U.S. Constitution

What

the Framers ultimately came up with as they concluded their work in

mid-September was a central or federal political authority with just

enough power to keep the states working together in a sense of American

unity, but with enough limits to its powers to insure that it would not

fall into the human sin of unchecked power hunger that led inevitably

to tyranny.

In a sense what they had finally

agreed on was a new treaty of political alliance among the thirteen

independent states,5 a treaty stronger than the one that had empowered

the Confederation. This new treaty instead provided for a federation,

meaning a political union with strong powers (though only in certain

carefully prescribed areas of governance) assigned to a central

authority by the still quite strong individual state governments that

made up the Union.

5Although

Rhode Island did not send a delegation to participate in the drafting

of the new Constitution, Rhode Island did finally join the Union in

1790.

|

Congress or the legislative branch of the federal government

The heart of this federation was to be a newly empowered Congress (one with

wider powers than the older Continental Congress), which would meet

periodically to enact certain categories of legislation for the Union.

This Congress, as per the Connecticut Compromise, was to be made up of

two separate assemblies. The lower house, the House of Representatives,

would represent the American people directly, elected by them and thus

giving the new federal Union something of a democratic quality. But the

upper house, the Senate, would represent instead the states, each of

the participating states being permitted to select and send two of its

most respected statesmen to Congress to give direct voice to the

interests of their respective states. Also, the Senate was supposed to

be something of a more aristocratic assembly, a council of political

dignitaries who were to keep cooler political heads than what might be

expected of the representatives of the people in the House of

Representatives.6 But in any case, Congress would be able to function

only as both the House and the Senate worked together.

6However,

the Senate was "democratized" in 1913 with the passing of the

Seventeenth Amendment, having the voters of each state, rather than the

state assemblies, select their two senators.

|

The president or the executive branch

Congress was intended to be the political center of the whole system: a

place where representatives of the states and the American people

themselves might gather to do the business of the Union. But the

Constitution provided also for an executive officer, a president, whose

primary job was to oversee the ongoing unity of these United States. He

was to be no king but only a political supervisor elected for a term of

four years (presumably renewable however), elected not by the people,

but by the states whose union he presided over. Actually it was the

duty of an electoral college to choose the president (called into

existence every four years solely for that single purpose), each state

accorded a number of electors equal to the number of representatives

they were entitled to have in the House of Representatives, plus an

additional two electors (as thus also each state had two senators).

Each state was given the right or responsibility to decide who those

electors were to be, with the important restriction being that they

could not be chosen from among the ranks of a state's congressional

representatives or senators.

The president was given a key leadership duty in

being the one to call Congress into legislative session (even call

special sessions of Congress if need be) and to report to Congress on

his observations as to the "State of the Union." He was also expected

to be the enforcer, that is, the one assigned the task of seeing that

the laws passed by Congress were indeed faithfully executed or followed

throughout the Union. In short, he was seen primarily as an executor of

Congress's legislation, although possessing limited veto or blocking

power if he deemed such legislation inappropriate to the health of the

Union. But even then, if Congress could on a second attempt at passage

gather, instead of just the usual simple majority for passage, a full

two-thirds vote approving the proposed bill (a much more difficult

political feat to carry off), Congress could override the president's

veto, and the bill would become in fact actual law.

The president did have additional functions that

fell to him alone, such as sending and receiving diplomats, symbolizing

the majesty of the United States, and along those same lines was given

the responsibility of overseeing the country's relations with other

countries. He also was given the responsibility of serving as the

commander in chief of the U.S. military, a vital role in the follow-up

to his foreign policy responsibilities (however he could not actually

employ this military except when specifically authorized to do so by

the Congress). And also, as Congress met only periodically, he (and his

cabinet staff) was given the task of the ongoing or day-to-day

administration of the federal system at the all-union or national7

level.

7Actually,

it would be wrong to characterize the United States as a nation at this

point. Certainly citizens had some kind of collective or national

identity as Americans. But that sentiment would develop in depth only

later. At the moment they still saw themselves primarily as New

Yorkers, Virginians, Georgians, etc.

|

The Supreme Court or the judicial branch

The Constitution also described a Supreme Court of federal judges or

justices, largely expected to act in accordance with British legal

tradition in seeing to the fair application of the laws of the

legislature (Congress) in disputes that might arise with the actual

application of the law to particular circumstances. The judges were to

see that such disputes were indeed settled in accordance with their

well-informed understanding of the meaning of the law (they were

themselves lawyers of course).

The judges would be appointed by the president,

but be able to take office only after a confirming vote by the

Senate. At the time it was anticipated that the federal judges

would be

involved mostly in issues arising largely around this tricky matter of

the relationship among the different states of the Union.

The Framers obviously did not foresee that the

judges or justices serving on the Supreme Court (but also the district

courts as well) would step by step go well beyond the scope of the

originally designed Constitution to begin to reshape the law according

to the judges' own "more enlightened" personal interpretations as to

how the law ought actually to read in its application to national life.

By this is meant the justices' ability to shape, revise, or even set

aside the law of the land in accordance with merely the personal

ideological, moral or "rational" inclinations of the nine supreme court

justices themselves – or often only upon the decision of a simple

majority five of the nine justices, against the objections of the other

four. In short, over time, step by step, these individuals, possessing

unchecked and thus unlimited legal powers, would succeed in making the

Supreme Court – not Congress – the supreme legislative or law-making

body found within the American federal system. But we will have more

(much more) to say about this matter in later chapters.

The limited powers of the central government

Indeed, there was only a very limited internal or domestic governmental

role anticipated for the newly created Congress and President (and

Supreme Court) by the Framers of the new Constitution. It was

understood that the principal concern of Congress, the unifying voice

of the different states and the American people, would be limited to

those matters primarily concerning the new Union's foreign civil and

military relations with the outside world.

There were some domestic responsibilities assigned

to Congress. It had a number of financial powers, such as creating its

own tax sources; establishing, regulating and protecting a national

coinage or currency; borrowing on credit; standardizing the rules of

bankruptcy throughout the United States. Congress could establish a

Union-wide postal service and post roads. It was to encourage the

development of science and the arts through standardizing weights and

measures, creating uniform copyright or trademark protections. It was

to create uniform rules by which people could attain citizenship

("naturalization").

The most interventionist of

the clauses of the

Constitution in the domestic affairs of the Union was the power

assigned to Congress to regulate commerce among the states (the

interstate commerce clause). But interstate commerce was seen simply

as the issue of the states raising trade protections against each other

– a practice the Constitution was designed to bring to an end. It was

not intended as an open door for Congress (or the president or the

Supreme Court) to become involved in the internal affairs of America

(as would in time indeed become the case).

The residual powers of the states in the federal system

So, with the exception of the specifically named powers of Congress to

act on domestic issues, the states – and the states alone – were the

only part of the federal system authorized to provide the people

domestic government, that is, government inside the Union itself, as

the American people themselves chose to do so through their

representatives elected and commissioned to serve on their state

assemblies and governing councils.

A republic rather than a democracy

It is

important to note that the word "democracy" never appeared in the

Constitution. The Constitution did define the political nature of this

new political order as being republican – very specifically stating

that any new states eventually joining the Union (Kentucky stood at the

door expecting to become part of the Union very soon at that point)

must be republican in character. The republican character of the Union

was a matter that Congress itself was importantly to look after.

The rule of law rather than personal or even popular will

To the Framers, democracy, as much as monarchy or aristocracy, implied

the rule of the human will, whether the will of the many, of only one

or of a special few. The framers understood that any form of government

directed by the will of human agents, however many or however few, was

easily susceptible to tyranny.

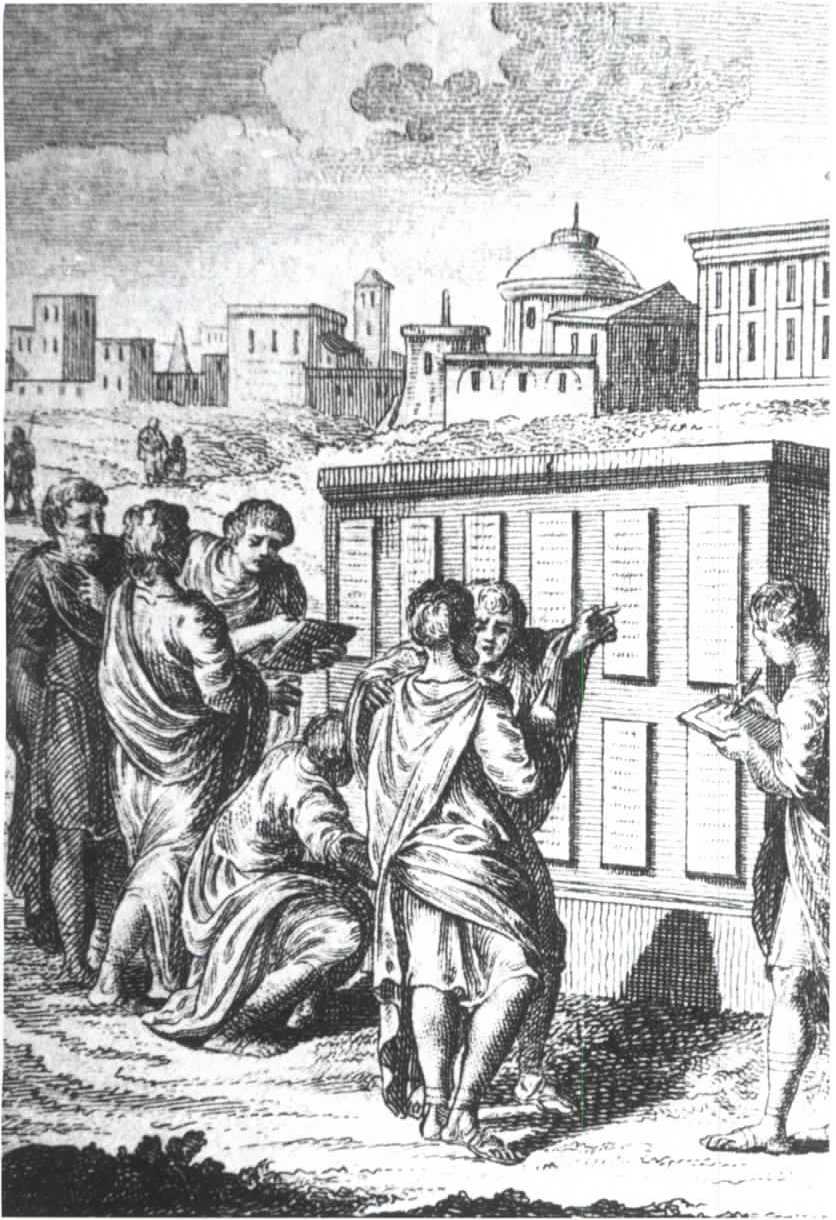

Rome's Twelve Bronze Tablets

Rather, the Framers were looking to establish the

rule of law – concrete principles that could be etched into stone or

inscribed in bronze (as they anciently had been in the Roman Forum),

principles that would stand for all times for the community. Humans and

their personal desires would come and go. But laws carefully enacted

through the constitutional directives they were putting into effect

would not be easily swayed by changing human desires and fancies. No,

the new government would be a government not of men but of laws.

The Romans had constructed such a political

system. They too had believed (in accordance with the ancient Romans'

typical love of order over impulse) that a government should be a

system of laws, not personal wills. The Framers agreed strongly with

this same principle. Their hope was that, unlike the Romans who failed

to hold to this fundamental principle, Americans would remain vigilant

in maintaining the idea of government as a regime of laws rather than

human wills.

This was the central idea directing the

deliberations of the Framers of the Constitution that summer of 1787.

They would create a Republic built solidly on constitutional law. But

the question still remained: would the American people be able to

maintain this Republic any better than had the Romans?

|

A GOVERNMENT THAT DRAWS ITS POWERS FROM THE PEOPLE – NOT VICE VERSA |

| Further

securing the rights of the people against governmental tyranny –

through the addition of 10 Amendments. Not surprisingly, the final

draft of the Constitution the Framers put together still left

unresolved considerable concern among some Americans about the dangers

of potential tyranny in this new system. Consequently, in order to win

over the reluctance of such Anti-Federalist or states'-rights people as

Jefferson and other prominent Virginians, a promise was made by the

Framers that the Constitution would be immediately amended upon taking

effect to include a number of additional constitutional Articles

further guaranteeing American freedoms against this new government,

something Americans know today as their Bill of Rights.

Prominent among these guarantees is the very First of these Amendments:

Congress shall make no law respecting an

establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or

abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the

people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a

redress of grievances.

This Amendment concerning the people's right to

worship, speak, read, gather peacefully and petition their government

was placed in the prominent position as the First Amendment to the

Constitution, emphasizing the guarantee that the new federal authority

would not infringe on the personal rights of Americans, rights that

Americans had built their lives on and therefore rights that they

demanded full respect for by any governing body taking social authority

in their world.8

The Second and Third Amendments concerned

respectively the right of the people to keep and bear arms, and the

forbidding of the stationing of troops in people's homes without their

consent.

The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth

Amendments concerned the rights of the people in the official process

of an arrest, trial and sentencing.

And the Ninth and Tenth Amendments made it clear

that the states and the people retained full rights on all matters not

specifically assigned by the Constitution to the central authorities

within the federal system:

9. The enumeration in the Constitution, of

certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others

retained by the people.

10. The powers not delegated to the United

States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are

reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

These last two Amendments were extremely critical – in promising that other than the powers specifically described in the

constitutional document as accorded to the central or national branches

of the federation, all other powers of government would remain reserved

entirely as the privilege and responsibility of the states, or the

people of those states.

The question nonetheless remained: would such

constitutional guarantees be sufficient to hold back the tendency of

social authorities, especially those who see themselves as

exceptionally enlightened, to want to expand their powers of control

over the people? This was very much part of the great political

question that had bothered philosophers since ancient times: quis

custodiet ipsos custodes / who (or what) will govern those who govern?

Will the people control their government – or will their government

control them? Who will be sovereign: the people themselves, or some

special government authority towering over them?

This matter of sovereignty

The issue of sovereignty, whether the states' or the people's, had

weighed heavily over the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention.

The word sovereignty means rule over. According to long established

European political custom, the sovereign was the king. The king ruled

over his subjects. The people literally lived and functioned at his

tolerance and under his direction. French King Louis XIV (1643-1715)

had perfected this idea in France: the king rightly should enjoy total

or despotic powers over the people because he would be expected to be

the most enlightened member of the community and therefore in the best

position to know what was right for the community he ruled over. This

idea was then quickly picked up by other European kings, including, a

century later, the English king George III. The issue of sovereignty, whether the states' or the people's, had

weighed heavily over the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention.

The word sovereignty means rule over. According to long established

European political custom, the sovereign was the king. The king ruled

over his subjects. The people literally lived and functioned at his

tolerance and under his direction. French King Louis XIV (1643-1715)

had perfected this idea in France: the king rightly should enjoy total

or despotic powers over the people because he would be expected to be

the most enlightened member of the community and therefore in the best

position to know what was right for the community he ruled over. This

idea was then quickly picked up by other European kings, including, a

century later, the English king George III.

This piece of royalist logic did not sit well with

the American subjects of the English king. For a century and a half,

since they had left England and crossed a great ocean to start life

anew in America, they had needed no king to do their thinking for them.

For that century and a half they had been left alone to rule

themselves. Families and local communities managed their own affairs on

a daily basis, and on special occasions when there was a need to do

some colony-wide business, they would elect representatives to be their

voice in the management of the larger affairs of the colony. They had

done just fine as self-sovereigns and resented it immensely, finally to

the point of rebellion, when George III and his Tory supporters in

Parliament attempted to bring these free peoples under tight royal

control.

The people's divine rights

Lingering

behind this debate was the question of political legitimacy. European

kings founded or justified their despotic powers not just on the basis

of enlightenment (for even commoners could bring themselves to

enlightenment) but also on the basis of Divine will. For centuries

European kings had been claiming that they enjoyed their sovereign

position because of the desire of God himself that they should so rule.

God caused them to be born to this position. So how could anyone

question what God had decreed. After all, Deus vult, "God wills it."9 European kings (as they saw things) thus ruled by divine right.

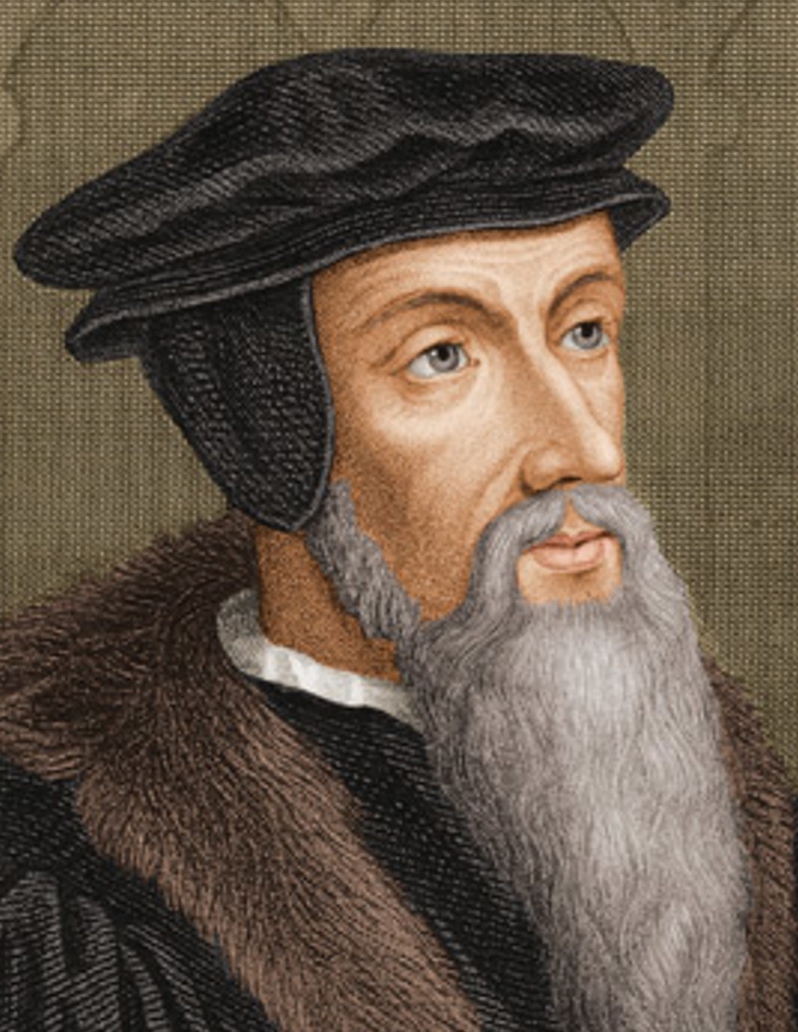

But

Americans not only had learned the art of self-rule through a century

and a half of effective self-government, they too felt that they had

done so as a legitimate matter – also of divine rights. They were

Protestants, heavily shaped in their thinking by the Protestant

Reformer Calvin,10 who had raised the idea that all people, kings and

commoners, enjoyed equally important responsibilities before God even

though the roles they played in society were different. As the Apostle

Paul pointed out in his letter to the Corinthians, although people are

gifted in their service to the community differently, they are all

equally important in the eyes of God and in the functioning of the

community. Each person has a distinct calling (vocation) from God to

play a key role in the life of the community. Each receives empowerment

from God in the performance of his or her vocation; each is equally

responsible before God for the proper carrying out of that vocation.

There is no room for laziness, no room for cheating, and no room for

lording it over others, for God's justice is not to be mocked. Their

ultimate accountability therefore is not to some human authority, but

to God himself. But

Americans not only had learned the art of self-rule through a century

and a half of effective self-government, they too felt that they had

done so as a legitimate matter – also of divine rights. They were

Protestants, heavily shaped in their thinking by the Protestant

Reformer Calvin,10 who had raised the idea that all people, kings and

commoners, enjoyed equally important responsibilities before God even

though the roles they played in society were different. As the Apostle

Paul pointed out in his letter to the Corinthians, although people are

gifted in their service to the community differently, they are all

equally important in the eyes of God and in the functioning of the

community. Each person has a distinct calling (vocation) from God to

play a key role in the life of the community. Each receives empowerment

from God in the performance of his or her vocation; each is equally

responsible before God for the proper carrying out of that vocation.

There is no room for laziness, no room for cheating, and no room for

lording it over others, for God's justice is not to be mocked. Their

ultimate accountability therefore is not to some human authority, but

to God himself.

Thus when English King George III invoked divine

rights in his attempt to bring the American colonies under his complete

control they answered with their own Divine Rights Theory.

Again, this is well stated in the opening paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence:

We hold these truths to

be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed

by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are

Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these

rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just

Powers from the consent of the governed ...

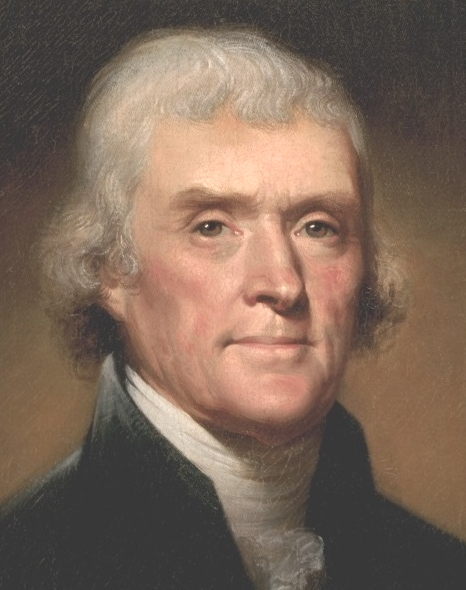

Thomas Jefferson elaborated on this a few years later in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), although note that he was talking about slavery in the harshest of terms (odd, he himself being a slaveowner): Thomas Jefferson elaborated on this a few years later in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781), although note that he was talking about slavery in the harshest of terms (odd, he himself being a slaveowner):

God who gave us life gave us liberty. And can

the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their

only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these

liberties are a gift from God? That they are not to be violated but

with His wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God

is just, and that His justice cannot sleep forever.

Regardless of the source of the problem (King

George's tyranny or the evil of slavery), it was quite obvious that

there was a strong understanding in America at the time that the rights

of the people did not come from some human authority, nor from some

human institution. Those rights (and accompanying responsibilities)

came from God, and God alone.

So for those who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787

to work out the Constitution of a new American government the question

of political sovereignty was clear: it belonged (by the will of God) to

the people – or to them through the states, which, through their

elected representatives, the sovereign people controlled with their

right to vote. The rights of the American people did not, and would

never, derive from the institution of some governing state, whether

kingly, or aristocratic or even bureaucratic (professionals working

full-time for the state). It belonged naturally, by the will of their

Creator, with the people themselves. The new federal government with

its carefully defined and limited authority would function only as the

sovereign American people should empower it, either directly through

the House of Representatives or indirectly through the Senate

(representing the states, whose own political officials were generally

elected in whole or in part by the people).

Protecting and preserving the sovereignty of the people

The people's rights, of course, are hard to hang on to, as the Framers

of the Constitution were well aware, having just fought a bitter battle

against the English king and his armies to preserve their rights as

Americans. What could possibly serve as some kind of guarantee that

these rights would not be lost again, that some kind of tyranny of

those who lust after political power (and find ingenious ways of

justifying this lust morally) would not eventually arise in America?

They were quite familiar with the failures of Athens, Rome and Israel

in this regard. What could guarantee that this would not also happen to

them? This is why Franklin answered the query as to what the

Constitution architects had created: "A Republic ... if you can keep

it."

8Note

that the First Amendment makes no mention of the "separation of church

and state" which has come (via Thomas Jefferson) to be understood today

as meaning that traditional religion (Christianity, for the most part)

may not be practiced or involved in the ever-widening realm of the

nation's public domain (most notably, public schools and public grounds

of any kind). Actually, the Amendment clearly meant that the state had

no business whatsoever regulating the practice of religion – which it

does extensively today via the federal courts – in establishing

Secularism (Humanism) as the only religion allowed to be practiced in

the public domain. Precisely, the Supreme Court has taken the authority

to describe in detail exactly when and where religion could be

practiced legally, and where it is to be prohibited from being freely exercised – in clear and total violation of the First Amendment.

9An

expression that went all the way back to 1096 when Christian Crusaders

headed off to the Middle East to liberate the Holy Lands. But

eventually it became the proclamation of English kings as they

authorized new royal rules.

10Especially

the Puritans or Congregationalists, the Scottish Presbyterians, the

Dutch Reformed, the German Reformed and French Huguenot communities in

America. The Baptists (offshoots of Calvinism) and Quakers also had

this same understanding of society and its politics.

WHAT WERE THE GUARANTEES THAT HIS WOULD WORK? |

But

all of them knew the answer to that question: their sovereign rights,

their personal freedoms, could be guaranteed by no living being, no

matter how kindly disposed he might originally be. According to their

Puritan understanding, man was by nature invariably a sinner. Given

enough opportunity, power would corrupt any human heart.

A mechanical system of checks and balances

Certainly they had been careful to build into the government a system

of checks and balances which would actually use human selfishness or

political greed to good effect. The system was set up so that

cooperation among a number of various branches of government would be

required to make the system work. And cooperation meant compromise, the

necessity of having to give up the desire for total power, in order to

employ any power at all. If one of the branches of government would

start to assume more power for itself (a rather certain possibility)

this would stir the indignation of the other branches, which out of a

self-serving sense of the relative loss of their own power, would gang

up on the usurper of their joint power! A very ingenious system!

In God We Trust

But by no means did they

rely entirely – or even mostly – on this ingenious mechanical system.

They were well aware, just as Franklin had stated, that this whole

enterprise would ultimately succeed or fail on one issue, and that

alone: the will of God. They needed to stay closely in line with the

will of God, who after all had given them the victory against royal

tyranny in the first place. They needed to look to God in full trust

for such protection, look to God as "In God We Trust." Otherwise

nothing, not even clever mechanics, would protect them from human evil.

George Washington stated the case very clearly

in the speech he addressed to the nation as he took office in 1789 as

America's first president:

It would be peculiarly improper to omit, in

this first official act, my fervent supplication to that Almighty

Being, who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of

nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect,

that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of

the people of the United States, No people can be bound to acknowledge

and adore the invisible hand which conducts the affairs of men more

than the people of the United States. Every step by which they have

advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been

distinguished by some token of providential agency, We ought to be no

less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be

expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and

right, which Heaven itself has ordained.

This was not mere political posturing, this

reference to the all-important role that God had played in winning for

America its national independence, Washington's appeal to Americans to

continue to look to that same God for divine support as the nation now

moved forward. his appeal to God's favor was very serious business for

it rested on a Truth that recent experience had made very, very clear.

This was not just religious platitude, designed by Washington to

comfort the people with an assurance that he was a proper church-going

Christian (which he frequently was not). This was testimony to the

reality of politics that all of these quite astute practitioners of

politics had come to understand – at a very deep level. The American

venture would not fail, as had Athens' and Rome's and Israel's attempts

at self-government, as long as it retained a very deep sense of

connectedness to God and his hand in the affairs of man.

Christian Realism – and the Christian Covenant

In the end what we will term as the philosophy which guided these

framers of the American Constitution is "Christian Realism." This

philosophy was founded on the understanding that man can be both an

angel and a devil, prone to do good and prone to do evil. Man must be

allowed enough opportunity to put into effect his ability to do the

good, while at the same time be put under enough legal restraint to

check him against his equal ability to do evil. Ultimately only God

could be counted on to do the truly good. But man and God could work

together, with man operating under God's judgments, inspired by an awe

of God and desire to please God – yet at the same time fearful of what

might happen if he did not remember to obey God. Thus this Constitution

would work for American society, as long as Americans understood the

rules and as long as Americans freely chose to keep this Constitution

as a Covenant with God. Anything else would fail.

As Christians, the Framers of the Constitution

were well aware of the words of advice – and warning – that Moses gave

Israel as it entered the Promised Land (the very same verses that

Founding Father John Winthrop referenced in his 1630 sermon, just as

the Puritans were about to embark to begin their great Puritan

experiment):

Observe

the commands of the LORD your God, walking in his ways and revering

him. For the LORD your God is bringing you into a good land – a land

with streams and pools of water, with springs flowing in the valleys

and hills; a land with wheat and barley, vines and fig trees,

pomegranates, olive oil and honey; a land where bread will not be

scarce and you will lack nothing; a land where the rocks are iron and

you can dig copper out of the hills. Observe

the commands of the LORD your God, walking in his ways and revering

him. For the LORD your God is bringing you into a good land – a land

with streams and pools of water, with springs flowing in the valleys

and hills; a land with wheat and barley, vines and fig trees,

pomegranates, olive oil and honey; a land where bread will not be

scarce and you will lack nothing; a land where the rocks are iron and

you can dig copper out of the hills.

When you have eaten and are satisfied, praise

the LORD your God for the good land he has given you. Be careful that

you do not forget the LORD your God, failing to observe his commands,

his laws and his decrees that I am giving you this day. Otherwise, when

you eat and are satisfied, when you build fine houses and settle down,

and when your herds and flocks grow large and your silver and gold

increase and all you have is multiplied, then your heart will become

proud and you will forget the LORD your God, who brought you out of

Egypt, out of the land of slavery. ...

You may say to yourself, My power and the

strength of my hands have produced this wealth for me. But remember the

LORD your God, for it is he who gives you the ability to produce

wealth, and so confirms his covenant, which he swore to your

forefathers, as it is today.

If you ever forget the LORD your God and follow other gods and worship

and bow down to them, I testify against you today that you will surely

be destroyed. Like the nations the LORD destroyed before you, so you

will be destroyed for not obeying the LORD your God. (Deuteronomy 8:6-20 NIV)

|

THE FEDERALIST PAPERS AND THE PROCESS OF RATIFICATION |

|

The process of ratification

Whereas some of the states were

quick to approve (ratify) the new Constitution, not everyone was

completely sold on the new Constitution. As a result, it was not until

June of the following year (1788) when New Hampshire, the ninth of the

thirteen states voting to ratify, finally put the Constitution into

full effect.11

During the debate over ratification,

Anti-Federalists, such as Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry, had voiced

their fears through various newspaper articles that the individual

states were simply surrendering too much of the people's sovereign

rights to this new central authority. What were the guarantees that

this new government would not come to assume the powers of the royal

government they had so recently fought to free themselves from?

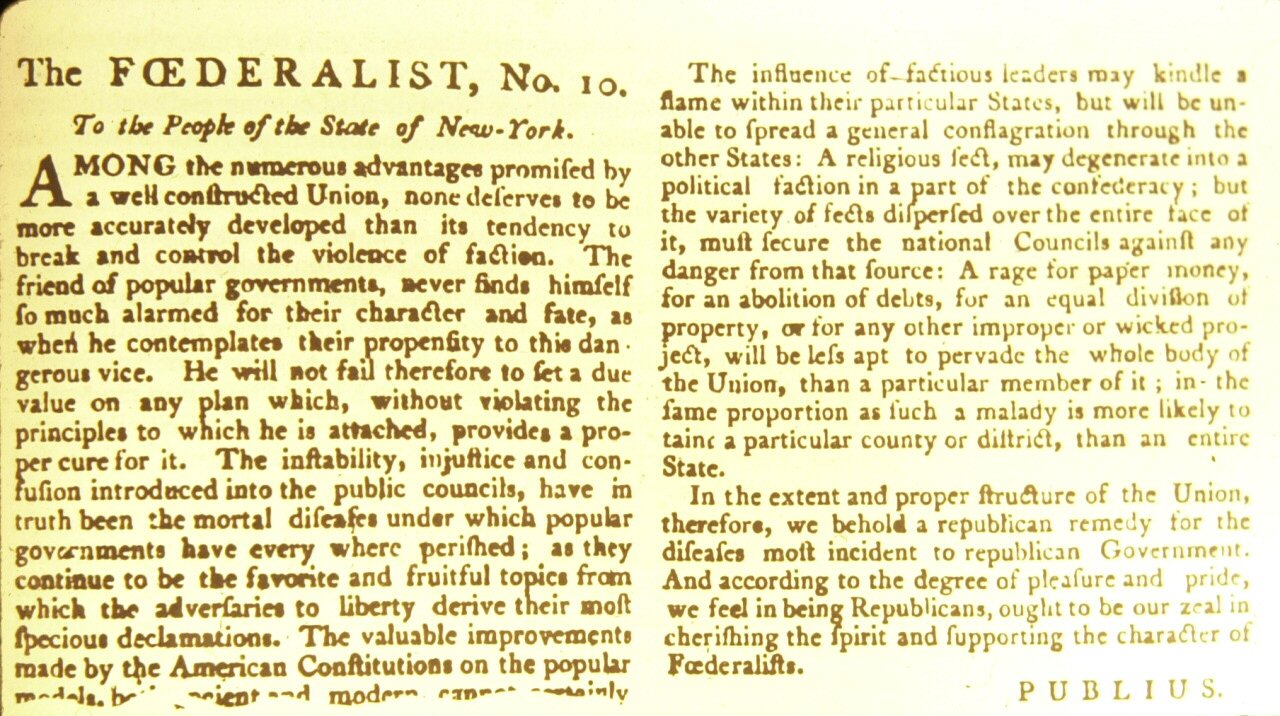

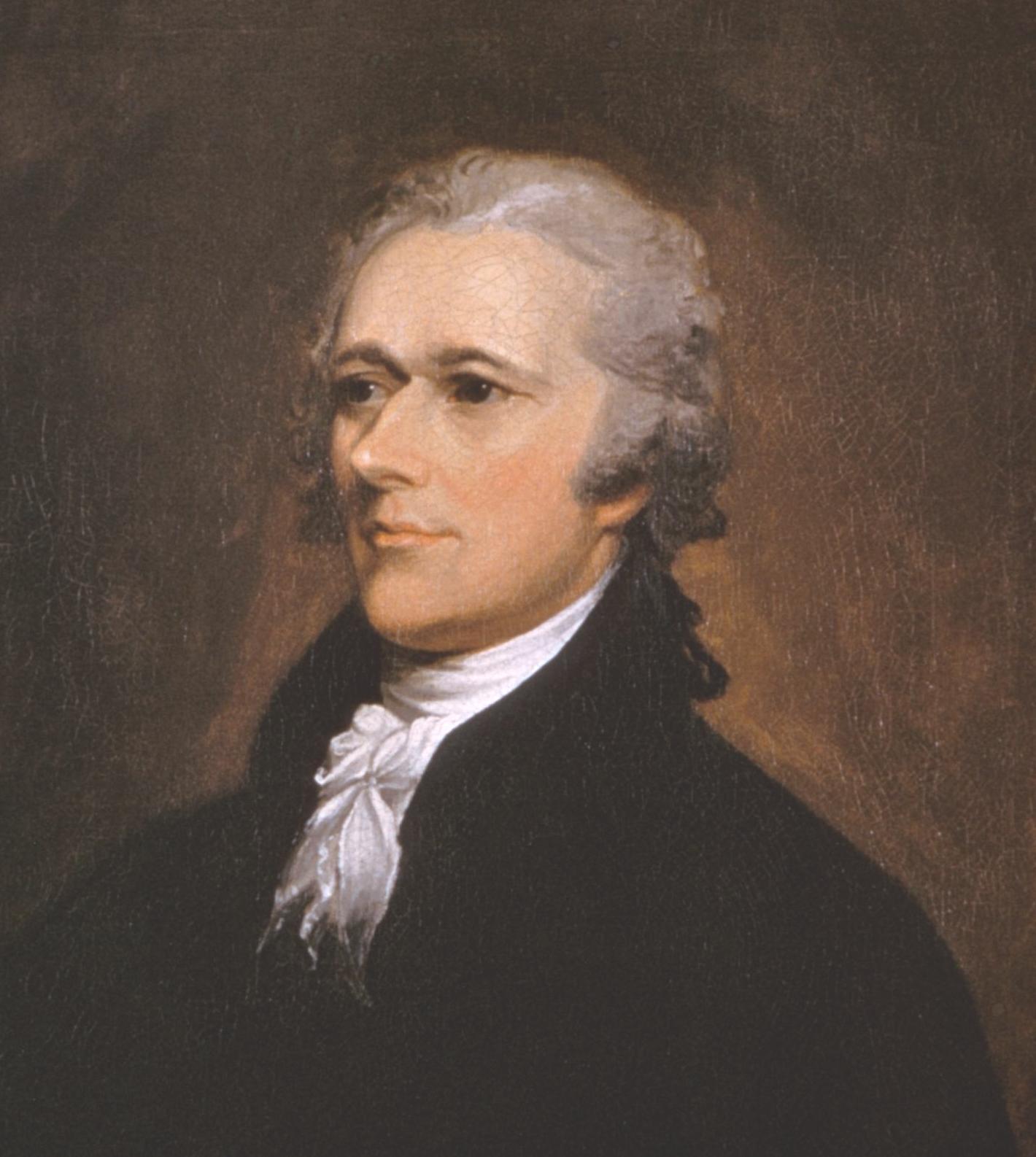

Federalists were quick to take up the challenge,

James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay writing replies to these

questions under the pen name Publius. Some eighty-five articles were

published by these three men, each article carefully explaining the

workings and benefits of this new Constitution, a collection of

articles which have come down to us today as the famous Federalist Papers.

Madison turned some of the criticism of the Anti-Federalists on their

head, pointing out that factions would form within the government,

simply because of the size of the new country, but these factions would

serve the useful purpose of checking each other's ambitions for power,

forcing debate and clarity of thought in government, and encouraging

the people to follow political developments closely rather than just

letting government officials go about their business quietly out of the

public sight, where tyranny might then truly develop. Hamilton, for his

part, stressed how a stronger central authority would more likely

attract society's natural leaders, involving them more closely in the

building of a financially sound economic system, the best guarantee of

a society's stability (and consequently its ability to protect personal

freedom and prosperity).

And thus it was that the Federalists were able to bring the country to approving this new experiment in republican government.

The last days of the Confederation

The new

federal Constitution was not submitted to the Congress of the old

Confederation, where it probably would have faced such resistance that

it would not have passed, but was sent directly to the states for their

approval. Each state was invited to set up its own process of

ratification, usually through a special session gathered for

specifically that purpose: to approve (or reject) the new Constitution.

Thus the Congress of the Confederation was left entirely out of the

process that would bring its own existence to an end.

However, the Confederation did perform for the new

nation one final and very important service when in 1787 it set out

clearly with the passing of the Northwest Ordinance the basis for

designing and admitting new states into the Union. Having been accorded

the right by the Treaty of Paris to develop the land west to the

Mississippi as American land, the Congress had a two-fold job: 1) get

the states to stop arguing over the ownership of that land and 2)

instead set up in this territory, at least in the Northwest, a number

of candidate-states, open to settlement and to eventual admission to

the Union as full members states – as they gained a certain size of

population and established their own state Constitutions.

Thus it was that the Northwest Territory (today's

Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and what would become the

eastern portion of Minnesota) was divided originally into a number of

territories or future states (ten originally, but ultimately the

five-plus described above). Also plans were drawn up for the creation

within these territories of towns and townships – according to a

precise grid pattern where each township was defined as a square of six

miles on each side, further divided into thirty-six sections of 640

acres each (one square mile). Also a section within each township was

ordered by the Northwest Ordinance to be set aside for sale for the

support of public education; and a public university was also to be

established within each of these major states.

11Delaware,

Pennsylvania and New Jersey had quickly ratified in December of 1787

and Georgia and Connecticut followed soon after in early January of

1788. Massachusetts (narrowly) ratified in February, Maryland in April,

and South Carolina in May, before New Hampshire signed on in June.

However, Virginia followed later in that same month, and New York in

July, thus assuring the Constitution that it would have the full

support of the heavyweight states. North Carolina did not ratify until

December of that year. Rhode Island, after first voting against

ratification, finally in May of 1790 approved the Constitution.

|

The three authors of the Federalist Papers: Hamilton, Madison, and Jay

|

These 84 newspaper articles were written to explain the workings of the new Constitution and its political benefits ... in the effort to get the new document officially ratified by the states.

Alexander Hamilton – by John

Trumbull (1806)

Alexander Hamilton – by John

Trumbull (1806)

National Portrait Gallery – Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

James Madison

White House

Chief Justice John Jay – by Gilbert Stuart

Chief Justice John Jay – by Gilbert Stuart

National

Archives

THE GEOGRAPHIC REDESIGN OF THE UNION |

|

Miles H. Hodges Miles H. Hodges

| | | | | | | |