1. THE ANCIENT GREEK LEGACY

ALEXANDER AND HELLENISM

The Late 300s to 3 B.C.

CONTENTS

A general overview of the Hellenistic A general overview of the Hellenistic

Age

Alexander ... and his conquest of the Alexander ... and his conquest of the

East

Alexander's Empire is carved up Alexander's Empire is carved up

The Antigonid Dynasty The Antigonid Dynasty

The Seleucid Empire in the East The Seleucid Empire in the East

Ptolemaic Egypt Ptolemaic Egypt

The development of Hellenistic culture The development of Hellenistic culture

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 52-71.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period BC

359 Philip II comes to power in Macedon (r. 359-336 BC)

340s Demosthenes issues his "Philippics," publicly denouncing Philp as a great danger to Athens

338 Philip takes control as hegemon of Athens and Thebes after the Battle of Chaeronea

336 Philip is murdered by a member of his own bodyguard ... bringing young Alexander to power

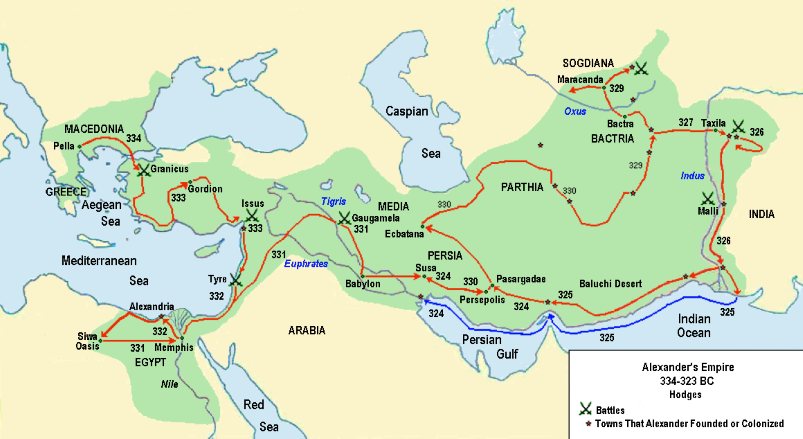

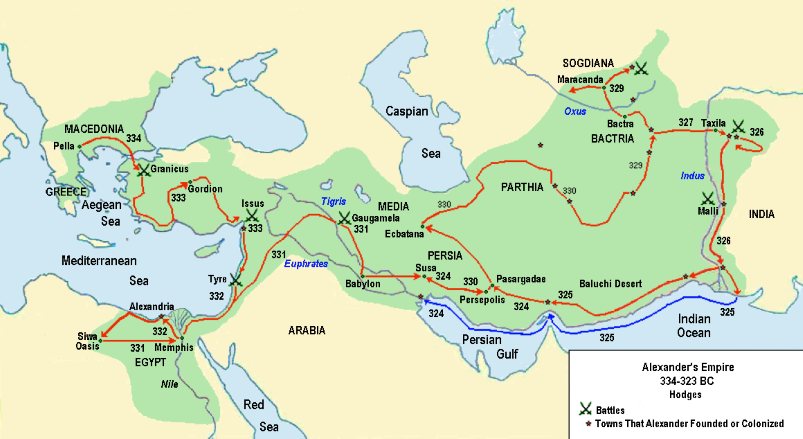

334 Alexander (only 22!) takes on the Persian Empire, starting with the battle at Granicus

333 Alexander's army destroys the Persian army at Issus ... then takes Syria and Palestine

332 Alexander takes Egypt ... and begins to build the city of Alexandria, Egypt

331 Persia is completely defeated at Gaugemela ... Alexander then taking the Persian throne

328 Alexander begins his march deeper into central Asia ...

326 Alexander's army reaches all the way to India (at the Indus River)

But his tired troops then refuse to advance further East

324 An exhausted Alexander finally finds himself back in Persia

323 A young Alexander (only 32) dies in Babylon ... mourned deeply by his troops

Cavalry general Perdiccas takes administrative control of the empire

Ptolemy I Soter however rules Egypt (323-283 BC)

321 Perdiccas is assassinated ... beginning the breakup of Alexander's empire

319 Alexander's wife Roxana and his son Alexander are poisoned ... ending all hope of union

305 General Seleucus Nicator rules (305-281 BC) from Babylon nearly all of the Asian portion of the Empire

Ptolemy takes the title of Egyptian Pharoah ... establishing the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt

283 Ptolemy II Philadelphia (283-246 BC) secures Ptolemaic rule in Egypt against Seleucid ambitions

He also has the

Jewish Bible translated into Greek (the "Septuagint Bible")

277 Antigonus II takes the kingship in Macedonia ... and then Greece

247 Arsacid Parthia breaks from from the Seleucid Empire ... reviving Persian resistance

217 Young Antigonid King Philip (221-179 BC) ends the Achaean-Aetolian war

200 Romans, in alliance with Greek rebels, bring Philip's Greece under Roman authority

188 Antiochus III's Seleucid army is defeated by Rome ... giving Rome dominion in much of the former Seleucid Empire

168 Romans defeat the Macedonian army at Pydna ... 300,000 Greeks carried off to slavery

63 Mithridates loses the last of the Selucid Syrian holdings with his defeat by Pompey

55 Ptolemy XII is placed back on the Egyptian throne ... but only as a Roman client

31 Marc Antony's Roman forces are defeated by Octavian's Roman forces at Actium

Marc Antony and

his lover Cleopatra VII chose suicide ... ending the Ptolemaic dynasty

Egypt is now just another Roman province

A GENERAL

OVERVIEW OF THE HELLENISTIC AGE |

|

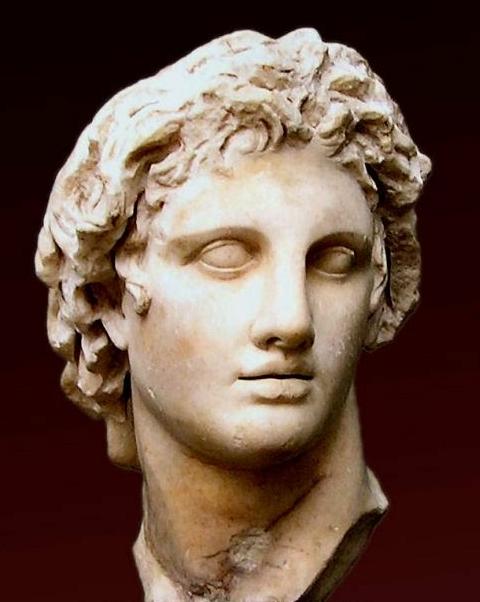

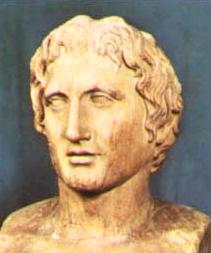

Alexander the Great (356-323 BC)

The brief, meteoric rise (and sudden loss) of the young conqueror of

the Greek North – Alexander of Macedonia – marks a critical turning

point in the evolution of Greek or Western cosmology. Everything

that seemed to lead up to the life of this conqueror of the known

civilized world of his times and everything that proceeded onward from

this amazing life threw the comfortable Greek cosmology into confusion,

disorder.

The Decline of the Greek City-State

The century prior to Alexander's arrival on the scene had been a time

of gradual decline from the self-understood grandeur of Greece (during

the "Age of Pericles" around 450 BC). True, the material culture

of Greece even reached new heights during this period. But

the moral- ethical foundations of Greek's cherished public life had

been undergoing quite noticeable decay. From the time that the

Athenian citizenry pronounced the death sentence upon Socrates (399

BC), philosophers had begun to wonder about whether things were indeed

so orderly in Greece. Indeed, reaching back even to the beginning

of the "Troubled Times" of the wars of the city-states in Greece

(starting in 459 BC), Athens had been growing increasingly imperious in

its relations with its neighboring city-states. Power, wealth,

status seemed only to corrupt the Good Greek order.

Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics

Around the time of Alexander (around 330 BC) a series of new schools of

political thought were founded by philosophers from around the Greek

realm (especially around its eastern borders). Though each of

these new schools was unique they all shared in common a view that the

private life was the only place that a person could trust things to go

right. They thus all drew back from the older Greek view that the

highest good for a person was in the contributions they might make to

the public life. These new philosophers instead looked within the

human soul in their search for order, good, truth, beauty. They

all tended to invite people to build a safe haven of life by withdrawal

from the public domain and a focus on personal intellectual

development. Here was where the blissful order could be

found. But some, like the Skeptics, were not even sure that this

was entirely a reliable haven. A sense of prevailing chaos seemed

to be getting a grip on the Greek mind.

Opening Up to the East

Alexander's conquest of the grand and vast Persian Empire to the East

in Asia began what some might feel ironically as the spiritual conquest

instead of the European West by the Asian East! Perhaps this is a

bit of an exaggeration. Yet certainly intimate contact with the

East through the new Greek Selucid (Syria and Palestine) and Ptolemaic

(Egypt) monarchies opened Greek culture to strong Eastern influences –

ones that reached to the heart of Greece, even to the venerable

Athens. Here a mystical vision of the divine order – perhaps not

too much different from Pythagoras' vision (whom we suspect had also

been profoundly influenced by Eastern thinking through his travels

there) – moved deeply into Greek thinking. Concepts such as life

after death (or – a return to life of an eternal soul as a new person),

notions such as the most noble life being found in a mystical union

with the very essence of God, these were ideas that began to take hold

in Greek thinking.

On-going Platonism and the new Stoicism stepped right into this thought

mode. So would elements of Judaism and, eventually, much of

Christianity.

ALEXANDER ... AND HIS CONQUEST OF THE EAST |

|

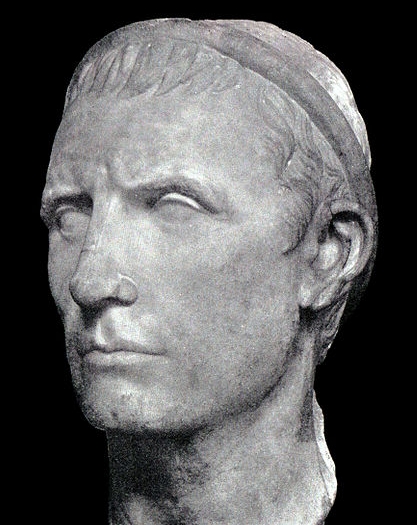

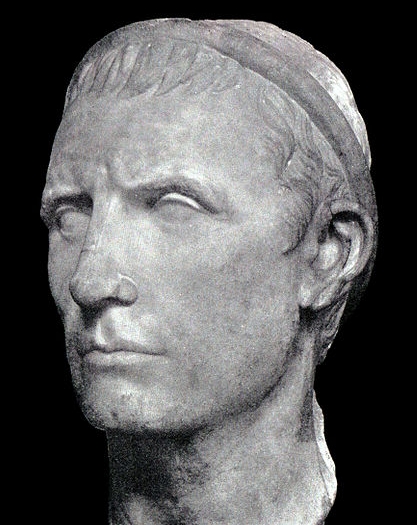

Philip II of Macedon (359-336 BC)

While

the city-states of Classical Greece seemed to be enjoying tremendous

prominence (when not fighting each other), a new power was growing to

the North of Greece: the semi-Greek kingdom, Macedonia, under its ruler

Philip II (382-336). Many of the Greeks, including some

influential Athenians, looked to Philip to rescue Greece from its

military and political follies. While

the city-states of Classical Greece seemed to be enjoying tremendous

prominence (when not fighting each other), a new power was growing to

the North of Greece: the semi-Greek kingdom, Macedonia, under its ruler

Philip II (382-336). Many of the Greeks, including some

influential Athenians, looked to Philip to rescue Greece from its

military and political follies.

But

others, most notably the Athenian statesman and orator Demosthenes, saw

in the ascendancy of Philip the end to Greek political values and

liberties. Demosthenes spoke fervently and often (his Philippics) about the dangers to Athens posed by Philip. But all to no avail.

The

son of the Macedonian King Amyntas, as a youth Philip was held hostage

by the Greek city-state of Thebes (at that time the strongest of the

Greek city-states). During that four-year captivity Philip

learned much about military and diplomatic strategy from his teacher

Epaminondas. He was able to return to Macedonia in 364 BC, where

he quickly proved himself in both battle and the conduct of diplomacy

... securing Macedonia from a threat coming from Thracians, Paeonians

and several thousand Athenian mercenary troops (359 BC).

That

same year, at age 23, he received the throne of Macedonia when the last

of his brothers died in battle. He immediately set himself to the

task of rebuilding his infantry corps or phalanx and proceeded to throw

Macedonian control over the surrounding states in northern Greece …

securing valuable gold fields in the region … bringing him frequently

in conflict with Athens. He spread Macedonian dominance to the

south in Thessaly (356-352 BC), turned again to focus on consolidating

his power at home in growing Macedonia, then in 349 BC resumed his

movement against Athens, Thebes and the other leading city states in

southern Greece. Only Sparta was spared the threat of Macedonian

domination. Finally in 338 he defeated the armies of both Athens and

Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea, opening for him the opportunity to

create the League of Corinth with himself as its hegemon or

leader. By this diplomatic action he finally brought peace to

Greece … under Macedonian supervision (despite ongoing political

opposition urged by Demosthenes).

Then

in 336 BC he was murdered by one of his bodyguards on the way to the

wedding of one of his daughters. At this point the Macedonian

challenge seemed to have suddenly disappeared as quickly as it had

arisen. Or so many hoped.

Young

Alexander

No

one was giving much thought to Philip's son, a young man of only

20. But Alexander surprised everyone by quickly revealing himself

to be every bit the man (even more so) than his father. Under his

father's sposorship, he had been carefully raised in Greek ways,

studied under Aristotle (when not off somewhere fighting battles!) –

thus combining personally the scholarly interests of his Athenian

teacher with the political talents of his Macedonian father. No

one was giving much thought to Philip's son, a young man of only

20. But Alexander surprised everyone by quickly revealing himself

to be every bit the man (even more so) than his father. Under his

father's sposorship, he had been carefully raised in Greek ways,

studied under Aristotle (when not off somewhere fighting battles!) –

thus combining personally the scholarly interests of his Athenian

teacher with the political talents of his Macedonian father.

Coming

to power in 336 BC, he quickly put down challenges to his kingship in

Macedonia ... and in Greece. He crushed and destroyed the

city-state of Thebes, sending a clear message to Athens to behave

(Demosthenes had turned his invective on Alexander since Philip's

death). Thus very quickly, Alexander demonstrated to the

surrounding Greek, Thracian and Illyrian peoples that, though young, he

was very much made of the same stuff as his father.

He

then in 334 BC moved to further galvanize his rule by turning the

combined Macedonian-Greek state he now ruled toward the idea of ending

the Persian threat to Greece forever. He intended to invade

Persia – and not just wait as they had in the past for the Persians to

take the initiative in their strained relations.

He

divided his Macedonian army (leaving some behind to keep his power

secure in Greece) and added a large number of Greek soldiers to his

ranks and then crossed into Asia Minor to raise the flag of

anti-Persian rebellion by the various subject peoples living there

under Persian tutelage.

When he and his army set off toward Asia Minor in 334 BC no one had any

idea of how far Alexander's ambitions in Asia were going to take them.

|

|

Granicus (334

BC)

Persian

royal power had been in decline for a while, corruption within the

bureaucracy was growing rapidly, and the subject peoples were quite

restless. Alexander saw his incredible opportunity as liberator

or deliverer of these subject peoples.

To

meet this challenge from Alexander, a Persian army was quickly

organized by the satraps of Asia Minor ... and proceeded to come out to

meet him at the Granicus River. The Persian forces expected to

demolish Alexander and his Macedonian-Greek forces in short order.

But

instead, Alexander and his army proceeded to crush the Persian forces

... much to the Persian dismay of the Persians. However,

Alexander was wounded in battle ... but continued to fight until the

Persians fled before him.

At this point the Persian regional capital at Sardis capitulated to

Alexander … and Alexander moved his troops onwards along the Ionian

coast (today's western coast of Turkey), with city after city going

over to his side (depriving the Persians of naval bases along the

Aegean Sea).

Then Alexander used the next months to consolidate his position as the new master of Asia Minor.

The Battle of Issus

(333 BC) and occupation of Syria/Palestine

He

then headed east towards Syria where in late 333 BC he met near the

town of Issus a huge Persian army ... led by the Persian king Darius

himself. But the area of the battlefield was narrow in scope, not

allowing Darius to bring the full force of his 400,000 man army against

Alexander's mere 40,000 troops. Alexander himself led a

cavalry charge straight into the Persian ranks … startling Darius and

causing him to flee … thus breaking the morale of his Persian army and

turning the battle into a slaughter of retreating Persians (and again,

also Greek mercenaries serving in the Persian ranks).

Onwards, towards Egypt

This

victory then opened up the eastern end of the Mediterranean to Greek

expansion. Indeed, Alexander easily entered Syria and Palestine

as liberator/conqueror, facing serious resistance only from Tyre and

Gaza, both of which he destroyed. Most other cities opened their

gates to the conqueror without resistance – and were met with fair

treatment.

Then

at this point he strangely turned away from chasing the humiliated

Persian Emperor ... and headed instead to Egypt. Here too he was

received without resistance ... in fact being received even as

liberator rather than as an enemy.

Was Alexander the son of a God? What might seem to be a mere side incident in the story is actually a

very major piece in Alexander's life. No doubt out of a desire to

get to the bottom of a story (and perhaps in part also out of a desire

to impress his troops) that Philip was not his true father – that

Alexander was actually descended on his father's side from one of the

gods – Alexander journeyed to the Siwa Oasis in the Libyan desert to

inquire of the famed priests of Ammon there as to the truth to the

story. They confirmed that indeed the story was true.

Indeed, Egyptian priests greeted him as a divine instrument of their

god Ammon and crowned him Pharaoh.

The establishment of Egypt's greatest city, Alexandria. While in Egypt he planted a Greek colony at the edge of the Nile delta

– a fabulous Greek-Egyptian city bearing (as did so many of the towns

or cities he founded) his name, Alexandria. It would soon grow to

outclass all other cities around the Mediterranean ... and hold that

position for centuries. Even with the rise of Rome, Greek

Alexandria retained the reputation for being the most sophisticated

city in the Western world. It would be the center of fabulous

Greek scholarship for at least another thousand years.

Gaugemela/Arbela and the defeat of Persia (331 BC)

But

soon it was time for Alexander to turn his attentions back to the

Persians. The Persians had been assembling the largest

multi-ethnic army ever seen before in western Asia. But

Alexander's army was more disciplined, more maneuverable and more

personally loyal to its leader than the Persian army. The two

prior defeats of the Persians also contributed to the high morale of

the Greeks and the nervousness of the Persians. In 331 BC the

Greeks and the Persians met in a mighty clash at the Battle of

Gaugamela (or Arbela). Once again the Greeks were victorious, and

once again the Persians and their king Darius were routed. Darius

was eventually hunted down (330 BC) – and put to death for his

cowardice by his own men as Alexander approached.

Victorious

in battle, Alexander now focused his attentions on consolidating his

rule over his newly acquired territories. Interesting, and

convenient for Alexander, even in the very heart of the Persian empire

Alexander was greeted as a liberator/conqueror. Babylon and even

Susa, the old Persian capital, greeted him as a liberator, and indeed

Alexander did what he could in service as "protector" of these grand

cities. He wanted to rule over a land of wealth, not ruin.

The sack of Persepolis

However

the new Persian capital of Persepolis proved to be a different

matter. The city tried to take a military stand in its own

defense – and chose the unwise tactics of parading before Alexander's

army 800 badly mutilated Greeks who had been captured earlier,

presumably as a ploy to demoralize the Greeks. Instead it merely

infuriated them (and Alexander) – and the Greek troops went wild,

slaughtering its inhabitants and burning Persepolis to the ground.

Consolidating his conquests by creating an East-West synthesis

Though

Alexander's power was clearly based on the support of his very

practical-minded Macedonian-Greek army, Alexander soon began to

envision himself as a great Oriental god-king sent to rebuild

civilization in what he supposed was the entire reach of the

world. He planted cities with Greek colonists wherever he went,

urged his soldiers to take wives from among the Persians and other

Oriental peoples (as he himself did in marrying the Bactrian princess,

Roxana), and did what he could to rebuild Western Asian civilization on

a mix of Greek and Oriental culture. His loyal troops humored him

in his thoughts, though they themselves were very unlikely candidates

for ever seeing Alexander as a god – as the Orientals so easily came to

see their new ruler. Though

Alexander's power was clearly based on the support of his very

practical-minded Macedonian-Greek army, Alexander soon began to

envision himself as a great Oriental god-king sent to rebuild

civilization in what he supposed was the entire reach of the

world. He planted cities with Greek colonists wherever he went,

urged his soldiers to take wives from among the Persians and other

Oriental peoples (as he himself did in marrying the Bactrian princess,

Roxana), and did what he could to rebuild Western Asian civilization on

a mix of Greek and Oriental culture. His loyal troops humored him

in his thoughts, though they themselves were very unlikely candidates

for ever seeing Alexander as a god – as the Orientals so easily came to

see their new ruler.

Onward

to Central Asia and India

Alexander

would not let up on his conquering ways, particularly as he began to

learn of other lands that lay to the north and east beyond the Persian

empire. He pressed on with his Macedonian-Greek army, first into

central Asia (328 BC), where he faced bitter conditions and bitter

resistance and where there was very little of value (Roxana excepted!)

to add to his already vast dominions. He then turned eastward

(327 BC), again passing through bitter situations in Afghanistan in an

attempt to reach India with its rumored wealth and splendor.

Crossing the high Hindu Kush Mountains he descended into the Indus

River Valley (326 BC) where at the Jamnia River he defeated King Porus

and his Indian army – though turning them into allies after all.

The reluctant end to the conquering

Hearing

of the wealth of India further East along the Ganges River he decided

to press on with his conquests, only to be faced with firm resistance

from his troops. They would go no further East. In fact,

after nine years of conquest, they were ready to return home to Greece

and Macedonia. For the first time ever, Alexander and his

ambitions faced defeat. Against the resistance of his own troops

he could do nothing.

The

Journey Back to Babylon

He

thus turned South along the Indus River, ran into trouble at Malli,

where he led a charge and was nearly killed – but rescued by his own

troops – putting him in convalescence for several months, before

continuing his journey back towards the West. He divided up his

troops, able to send only half of them back to Babylon by ship, the

other half having to take the desert route (today's Balochistan) –

which through heat and thirst left ten thousand of his soldiers dead

along the way and Alexander himself physically and mentally exhausted

in his arrival back in Persia.

His Last Days

On

arriving at Babylon he cleaned out much of the corruption that had set

in on his administration during his absence. He then returned to

the program of integrating his Greek and Persian supporters – including

organizing (in 324 BC) a massive marriage ceremony between his Greek

soldiers and Persian women, taking two Persian princesses as additional

wives of his own (a very non-Greek concept). He then had

rebellions to face down, including one among his own Greek troops (also

324 BC). His last enterprise (323 BC) was to have been a massive

exploration of the water link between Babylon and Egypt by 1000 ships

he had built for the occasion. But his body was spending itself

out – not only because of his constant exertions, but because of his

deep drinking and carousing that went on for hours. Just prior to

his departure on this grand sailing expedition he caught a fever which

his tired body could not shake – and as he lay dying ten days later his

army passed silently before him to bid their hero farewell. He

died the next day, June 13, 323 BC.

Most

interestingly, Alexander is remembered greatly not only in the West but

also in the East ... where he is known as Iskandar ... and his exploits

celebrated there as much as they have come to be celebrated in the

West. He was truly an outstanding individual ... empowered by the

forces of heaven, which every religion (except secular materialism)

knows well as being the ultimate source of all human greatness.

Alexander himself knew this to be so in his own case.

|

The palace at Pella in Macedonia

... where it all began

The palace at Pella in Macedonia

... where it all began

Miles Hodges

Miles Hodges

Miles Hodges

Alexander attacking Darius

III in the the Battle of Issus (mosaic) – First century BC in Pompeii

in the House of the Faun.

Alexander attacking Darius

III in the the Battle of Issus (mosaic) – First century BC in Pompeii

in the House of the Faun.

Perhaps after an earlier

3rd century BC Greek painting of Philoxenus of Eretria.

Archeological Museum of

Naples

Alexander attacking Darius

during the Battle of Issus – detail

Alexander attacking Darius

during the Battle of Issus – detail

ALEXANDER'S EMPIRE IS CARVED UP |

With

Alexander's sudden death, a crisis arose over the matter of who was to

succeed him in overseeing his empire. Alexander's Bactrian wife

Roxana was pregnant, and if she were to deliver a son it was assumed

that he should rule … under the regency of Antipater of

Macedonia. But this set the generals themselves to fighting among

themselves for power (the "Wars of the Diadochi").

Perdiccas. At

first Alexander's cavalry general Perdiccas took control by killing

Meleager, the commander of Alexander's foot soldiers – leaving himself

in unquestioned command. But when Perdiccas attempted to make his

own assignments with regard to the governance of the various regions of

the empire, he found himself strongly resisted by Ptolemy of Egypt and

Antipater of Macedonia - individuals previously assigned their regional

commands by Alexander.

Cassander.

When

Perdiccas was then assassinated by his own officers (321 or 320 BC),

the foundations of the Alexandrian Empire began to break up. In

310 BC Cassander – who took his father Antipater's position when

Antipater died in 319 BC … and who was once an early friend of

Alexander and fellow student of Aristotle – had Alexander's wife Roxana

and their 13-year old son Alexander poisoned. Thus any likelihood

of a continuing single Alexandrian domain ended. What at that

point was taking

place was the rise of a number of independent kingdoms, usually founded

by one or another of Alexander's generals.

|

THE

ANTIGONID DYNASTY IN MACEDONIA-GREECE |

Antigonus,

governing the region of Syria and Asia Minor (today's central Turkey),

first stayed out of the in-fighting among the Alexandrian

generals. However, the migrating Celtic-speaking Gauls began to

invade a weakened Macedonia and Asia Minor at this point. This is

what brought Antigonus II to action, and in defeating the Gauls in 277

BC, brought him to kingship in Macedonia, and then in Greece

itself. But then he had to face another challenge, from the Greek

general Pyrrhus, who had been off fighting and defeating the Romans in

Italy, but at a great cost to himself financially and in the loss of

many of his troops (thus the term "Pyrrhic" victory). At first

Antigonus was brought to defeat by Pyrrhus. But then Pyrrhus was

killed in another battle deeper into Greece, effectively returning

Antigonus to power in Macedonia and Greece.

But the Greeks themselves were attempting to regain their independence

from Macedonian rule … resulting in a string of Greek rebellions – even

on into the reign of the next Antigonid, Demetrius, and after him,

Antigonus III. But the latter was able not only to hold off a new

group of invaders from the north, the Dardanians, but also put down a

Spartan rebellion – largely by working diplomatically with the Achaean

League (cities of the Peloponnese Peninsula – except the hostile

Sparta).

In

221 BC, the 17-year-old Philip (221-179 BC) was finally able to take

the Antigonid throne ... and soon proved his worth in forming a new

Hellenic League, which brought to an end the "Social War" (220-217 BC)

between the Achaean League and the Aetolian League (Corinth and cities

on the northern mainland), giving Philip full respect in both Macedonia

and Greece. In

221 BC, the 17-year-old Philip (221-179 BC) was finally able to take

the Antigonid throne ... and soon proved his worth in forming a new

Hellenic League, which brought to an end the "Social War" (220-217 BC)

between the Achaean League and the Aetolian League (Corinth and cities

on the northern mainland), giving Philip full respect in both Macedonia

and Greece.

Rome now enters the picture.

But mounting problems with Rome would occupy Philip greatly. At

one point he entered into a treaty with Carthaginian General Hannibal

(then ransacking the Italian countryside) ... only to have the Romans

enter into an alliance with the Aetolian League – which tended to

remain hostile to Macedonian rule. But with the Romans deeply occupied

with their 2nd Punic War with Carthage, Philip was able to finally

crush the Aetolian League in 205 BC. But in 200 BC, the Romans

took up the cause of some of the still-rebellious Greek cities and

attacked Philip's Macedon, bringing Philip and his army to defeat.

The Romans allowed Philip to keep his throne, but put him under Roman

dependency ... and forced him to pay an indemnity of a thousand talents

annually. But Philip proved to be cooperative with the Romans in

their war with the Seleucid King Antiochus III and eventually the

indemnity was lifted and Philip was allowed to rebuild his weakened

rule.

Perseus

(179-166 BC), who followed upon the death of his father Philip, would

be the last Antigonid king. At first Perseus conducted fairly

friendly relations with the domineering Romans. But the Romans

finally decided that he was a bit too independent and went to war with

him (Third Macedonian War, 171-168 BC) ... in which Perseus was

defeated and captured at the Battle of Pydna, was paraded in Rome in

chains and was imprisoned by the Romans. Additionally, some

300,000 Greeks were deported and enslaved by the Romans ... and their

land given to Roman settlers. This would finally bring an end to

the rule of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia-Greece. Perseus

(179-166 BC), who followed upon the death of his father Philip, would

be the last Antigonid king. At first Perseus conducted fairly

friendly relations with the domineering Romans. But the Romans

finally decided that he was a bit too independent and went to war with

him (Third Macedonian War, 171-168 BC) ... in which Perseus was

defeated and captured at the Battle of Pydna, was paraded in Rome in

chains and was imprisoned by the Romans. Additionally, some

300,000 Greeks were deported and enslaved by the Romans ... and their

land given to Roman settlers. This would finally bring an end to

the rule of the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia-Greece.

Finally in 146 BC, Rome simply declared Macedonia to be a Roman

province. This then prompted the Greeks – spurred on by foolish

demagogues of the Greek cities of the Achaean League – to rise up in

revolt ... which turned out to be suicidal for the Greeks. As a

result, the city of Corinth was laid waste (similar to what happened to

Carthage that same year).

Following this, there were no further thoughts among the Macedonians or

Greeks about the possibilities of independence from Rome. They

were now permanently part of the Roman Empire.

1The

Roman legion proved itself to be a military formation superior to the

traditional Greek phalanx (more easily maneuvered in battle).

THE

SELEUCID EMPIRE IN THE EAST |

|

In the division of Alexander's Empire, infantry General Seleucus

Nicator would receive the largest section of the empire, approximately

the equivalent of the former Persian Empire … and all the problems that

went with it. Locating his own capital at Babylon in 305 BC,

Seleucus ruled Anatolia, Syria and Palestine, Mesopotamia, Persia,

Kuwait, Bactria (Afghanistan and Turkmenistan), and parts of what is

today Pakistan. However when Seleucus ran into serious opposition

in the eastern reaches of his empire from the Indian general

Chandragupta Maurya,2 he

entered into alliance with Chandragupta, handing over to him not only

much of the far eastern portions of the Empire (Afghanistan and

Pakistan) but also his daughter in marriage … receiving 500 elephants

in return – which Seleucus subsequently used to great advantage in his

battles elsewhere. In the division of Alexander's Empire, infantry General Seleucus

Nicator would receive the largest section of the empire, approximately

the equivalent of the former Persian Empire … and all the problems that

went with it. Locating his own capital at Babylon in 305 BC,

Seleucus ruled Anatolia, Syria and Palestine, Mesopotamia, Persia,

Kuwait, Bactria (Afghanistan and Turkmenistan), and parts of what is

today Pakistan. However when Seleucus ran into serious opposition

in the eastern reaches of his empire from the Indian general

Chandragupta Maurya,2 he

entered into alliance with Chandragupta, handing over to him not only

much of the far eastern portions of the Empire (Afghanistan and

Pakistan) but also his daughter in marriage … receiving 500 elephants

in return – which Seleucus subsequently used to great advantage in his

battles elsewhere.

But

much territory still remained to the new Seleucid dynasty that he

established. And into this land the Greeks migrated in large

numbers, bringing their language and culture ... leaving a permanent

mark on Central and West Asia that would only be replaced very slowly

by a return of the pre Greek cultures (but much changed through Greek

influence).

Seleucus'

son and grandson, Antiochus I (281-261 BC) and Antiochus II (261-246 BC), faced constant

challenges in the West as well – from the Egyptian Ptolemies and the

Celts (Gauls or Galatians) who were migrating into Asia Minor.

This ended up distracting Antiochus II so much that he lost control of

the satrapies of Bactria and Sogdiana (Afghanistan and

Turkmenistan) ... which however moved to independence as Greek Bactrian

States (c. 250 BC), Greek  power centers by their own rights. power centers by their own rights.

Indeed, Greek

Bactrian King Demetrius I Aniketos

("the Invincible") would invade India in 180 BC and set up a Bactrian

Greek-Indian kingdom that would last over a century and a half.

Parthian independence (247 BC).

And Parthia (northeastern Iran) also moved to independence under the

Greek satrap Andragoras (also around 250 BC) … but was not able to

maintain its independence. An Asian (of Scythian origin?) named Arsaces

soon overthrew him and laid the foundations in Parthia for the Arsacid

Dynasty … which would eventually come to dominate all of Persia for

five centuries as the powerful "Parthian Empire" (247 BC – 224 AD).

Antiochus III and the Romans. Antiochus

(223-187 BC) then made the fateful political decision to cooperate with the

Carthaginian General Hannibal – whose army at the time was thrashing

the Romans in their own homeland – in Antiochus's effort to liberate

mainland Greece from Roman influence. That was a mistake.

In four years of fighting between Antiochus's Seleucid army and the

Roman legions, Antiochus was slowly ground down by the Romans, in 188

BC had to accept humiliating terms for peace, and watched the eastern

provinces he had worked so hard to return to Seleucid control once

again go on their independent way. Likewise, he lost land in the

West (Anatolia, today's central Turkey) to Rome's allies Pergamum and

Rhodes. The next year he was killed (assassinated?) raiding

Persia in an attempt to gain the gold he was required to pay Rome as an

annual indemnity ... at the same time helping to establish Arsacid rule

in Persia in reaction to Antiochus's maneuvering. Antiochus III and the Romans. Antiochus

(223-187 BC) then made the fateful political decision to cooperate with the

Carthaginian General Hannibal – whose army at the time was thrashing

the Romans in their own homeland – in Antiochus's effort to liberate

mainland Greece from Roman influence. That was a mistake.

In four years of fighting between Antiochus's Seleucid army and the

Roman legions, Antiochus was slowly ground down by the Romans, in 188

BC had to accept humiliating terms for peace, and watched the eastern

provinces he had worked so hard to return to Seleucid control once

again go on their independent way. Likewise, he lost land in the

West (Anatolia, today's central Turkey) to Rome's allies Pergamum and

Rhodes. The next year he was killed (assassinated?) raiding

Persia in an attempt to gain the gold he was required to pay Rome as an

annual indemnity ... at the same time helping to establish Arsacid rule

in Persia in reaction to Antiochus's maneuvering.

Rome

now pretty much dictated matters ... at least within the Western

reaches of the Seleucid Empire (while the Eastern portions became

increasingly rebellious and independent). Seleucid kings came and went

in rapid succession ... and containing (or causing) civil strife

occupied most of their time in power.

By

the beginning of the 1st century BC little more than Damascus and the

area of Syria immediately around it was about all that the Seleucids

truly governed ... although they remained deeply involved in the

dynastic politics of the Eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea.

Far greater in power and importance by that time was the Greco Persian

(semi-Seleucid) kingdom of Pontus, to the north of Seleucid Syria ...

and encompassing all of Asia Minor and Anatolia (modern Turkey).

For a while Pontus's leader Mithridates VI

was able to hold off Roman power, defeating a Roman army in 89 BC. But

Rome was not going to let matters stand at that, and in 66 BC Roman

General Pompey took on Mithridates and set him and his army in flight.

Three years later. With Pompey closing in on him … and not wanting him

and his family to be subjected to a triumphal parade in Rome –

Mithridates chose suicide. At this point Seleucid Syria was simply

converted into a Roman province under the rule of a Roman governor. For a while Pontus's leader Mithridates VI

was able to hold off Roman power, defeating a Roman army in 89 BC. But

Rome was not going to let matters stand at that, and in 66 BC Roman

General Pompey took on Mithridates and set him and his army in flight.

Three years later. With Pompey closing in on him … and not wanting him

and his family to be subjected to a triumphal parade in Rome –

Mithridates chose suicide. At this point Seleucid Syria was simply

converted into a Roman province under the rule of a Roman governor.

2It is said that in a battle in 305

BC between the Greek and the Indian generals, Chandragupta was able to

field 600,000 troops and 9,000 elephants.

PTOLEMAIC (GREEK) EGYPT (323 - 30 BC) |

Ptolemy I Soter.

With Perdiccas's death, wide support existed for Ptolemy (r. 323-283

BC) to head up the Alexandrian Empire. Ptolemy wisely refused the

honor, understanding the many problems such an position would create

for him. Instead, he further consolidated his well-established

position in Egypt … as well as outlying areas along and across the

Mediterranean Sea. Ptolemy I Soter.

With Perdiccas's death, wide support existed for Ptolemy (r. 323-283

BC) to head up the Alexandrian Empire. Ptolemy wisely refused the

honor, understanding the many problems such an position would create

for him. Instead, he further consolidated his well-established

position in Egypt … as well as outlying areas along and across the

Mediterranean Sea.

Then in 305 BC he took the title of Pharoah, helping to legitimatize

his position among the Egyptians themselves. He hereby

established the beginning of a dynasty that would rule Egypt for the

next three centuries.

He also began the process of turning the Ptolemaic capital city

Alexandria into not only an economic and political power center ... but

also the most noble of all Hellenistic cities in terms of its

intellectual achievement (founding the great Royal Library of

Alexandria) ... one that even the eventual conquest of Egypt by the

Romans would not diminish.

His son and successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphia (283-246 BC)

proved to be an equally capable ruler, his navy succeeding in fending

off a Seleucid attempt to grab southern Syria (Palestine/Judah).

And he also held off an attempt by invading Celts or Gauls to try to

establish themselves in Egypt (they did take control of part of Asia

Minor ... known subsequently as Galatia His son and successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphia (283-246 BC)

proved to be an equally capable ruler, his navy succeeding in fending

off a Seleucid attempt to grab southern Syria (Palestine/Judah).

And he also held off an attempt by invading Celts or Gauls to try to

establish themselves in Egypt (they did take control of part of Asia

Minor ... known subsequently as Galatia

He also continued the policy of his father to support the intellectual

development of the capital Alexandria ... expanding the Library and

supporting scientific research. It was during his rule that Greek

culture would establish itself as the dominant culture of Egypt.

The Septuagint Bible. And most importantly for Western Civilization, he was instrumental in having the Hebrew Bible translated into Greek as the Septuagint Bible.3

This brought this key piece of Jewish law and literature out of its

narrower Hebrew cultural world into the much broader Hellenistic world,

offering that almost "universal" Greek speaking world of the day easy

access to what would eventually become the start up section of Western

civilization's most foundational writing.

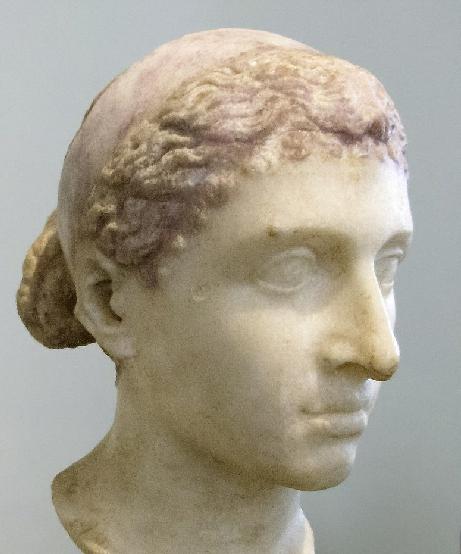

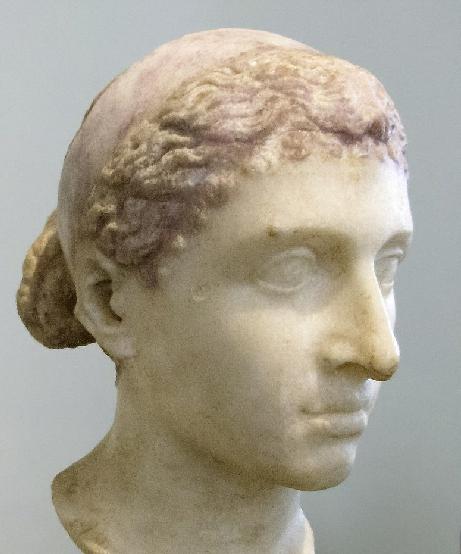

More Ptolemies … and Cleopatras!

Following Ptolemy II's death there were a succession of Ptolemies (for

a total of thirteen!). They increasingly took on Egyptian ways

... especially in marrying their sisters (frequently of the name

Cleopatra) such as the ancient Egyptian pharaohs had done.

Indeed, one of these Cleopatras (II) would rule from c. 175 BC to her

death in 116 BC through a series of husband brothers (Ptolemy VI:

180-145 BC; Ptolemy VIII: 144-132 BC) and then by herself (132-127) and

again with Ptolemy VIII and her daughter Cleopatra III (131-127

BC). It was all very incestuous ... and all very Egyptian.

Ptolemy VI "Philometor" ("loves his mother")

and his sister-wife Cleopatra II

Ptolemy VI "Philometor" ("loves his mother")

and his sister-wife Cleopatra II

(or possibly her daughter Cleopatra III)

Louvre, Paris

And as a general rule among the Alexandrians, these Ptolemies found

themselves usually at war with the Seleucids of Syria as well as the

Macedonians of old Greece. And of course these dynastic quarrels

and the political confusion they generated began to weaken seriously

the Ptolemaic dynasty ... so much so that the Romans simply moved

themselves gradually into the position of protectors of Ptolemaic Egypt

(just as they had done initially with Macedonia) … after 80 BC when an

Alexandrian mob lynched Ptolemy XI (who ruled only a few weeks) after

he murdered his stepmother – who was also his cousin and probably half

sister.

The next Ptolemy (Ptolemy XII, popularly known as "Auletes"

or "Flute player") was actually more of a Roman client than a true

Egyptian ruler. At one point he was driven from power (58 BC) and

exiled to Rome by his daughter Bernice IV ... but restored to his

throne in 55 BC by the Romans (after Ptolemy made a payment of 10,000

talents to one of Roman Consul Pompey's Generals). But at this

point Auletes enjoyed his power only through the support of Rome. The next Ptolemy (Ptolemy XII, popularly known as "Auletes"

or "Flute player") was actually more of a Roman client than a true

Egyptian ruler. At one point he was driven from power (58 BC) and

exiled to Rome by his daughter Bernice IV ... but restored to his

throne in 55 BC by the Romans (after Ptolemy made a payment of 10,000

talents to one of Roman Consul Pompey's Generals). But at this

point Auletes enjoyed his power only through the support of Rome.

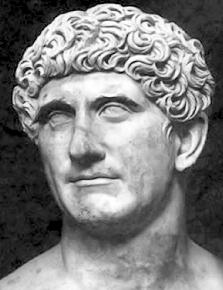

Cleopatra VII and Mark Anthony.

When he died of illness in 51 BC, he was followed on the throne by

another daughter, the 18 year old Cleopatra VII – who had served with

him as co regent during the last year of his life – as well as her

brother and husband Ptolemy XIII ... but the latter only briefly.

After a failed attempt to win Julius Caesar's support by murdering

Pompey, who had fled to Egypt to escape Caesar, Ptolemy XIII was

defeated (with the help of Caesar, who was her lover!) and died in 47

BC in a civil war he waged against her. Cleopatra then chose another

younger brother (and husband) Ptolemy XIV to rule with her. Cleopatra VII and Mark Anthony.

When he died of illness in 51 BC, he was followed on the throne by

another daughter, the 18 year old Cleopatra VII – who had served with

him as co regent during the last year of his life – as well as her

brother and husband Ptolemy XIII ... but the latter only briefly.

After a failed attempt to win Julius Caesar's support by murdering

Pompey, who had fled to Egypt to escape Caesar, Ptolemy XIII was

defeated (with the help of Caesar, who was her lover!) and died in 47

BC in a civil war he waged against her. Cleopatra then chose another

younger brother (and husband) Ptolemy XIV to rule with her.

When Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, she attempted to have her son,

Caesarion (born from the affair with Caesar) to take his place in

Rome. But Caesar's grandnephew Octavian took that position

instead. Nonetheless, she had her brother Ptolemy XIV murdered

(also 44 BC) and then elevated her son Caesarion to co rulership with

her in Egypt.

Following the assassination of Caesar, Rome itself fell into a series

of civil wars among a number of Roman contenders for power.

During this period the Eastern half of the Roman Empire (including

Egypt) came under the command of the Roman politician and general Mark

Antony (ca. 42 BC) ... with the Western half under his ally Octavian

Caesar.

This

eventually brought Mark Antony into a relationship where he and

Cleopatra openly became lovers (including the birthing of three

children) ... despite the fact that Mark Antony was married to

Octavian's sister, Octavia. This would become part of the reason

for a growing split between the former allies Octavian and Mark

Antony. By 33 BC the two Roman leaders were in full conflict with

each other and in 31 BC, in a major battle at Actium, Octavian's forces

decisively defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. This

eventually brought Mark Antony into a relationship where he and

Cleopatra openly became lovers (including the birthing of three

children) ... despite the fact that Mark Antony was married to

Octavian's sister, Octavia. This would become part of the reason

for a growing split between the former allies Octavian and Mark

Antony. By 33 BC the two Roman leaders were in full conflict with

each other and in 31 BC, in a major battle at Actium, Octavian's forces

decisively defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

Both Mark Antony and Cleopatra presumably chose suicide rather than

face the humiliation at the hands of Octavian. Cleopatra's 17

year old son Caesarion was executed soon after. The Ptolemaic

line of pharaohs had come to end. Egypt was now formally a Roman

province under the rule of a Roman governor (30 BC).

3"Septuagint"

from the idea of "Seventy" ... the number of Jewish scholars

commissioned by Ptolemy II to come up with a Greek translation of

the Hebrew Scripture or Bible. These 70 scholars worked

independently of each other. In the 70-day period in which they did their work, they presumably came up with exactly the same Greek translation – word for word – something considered miraculous then ... and today!

The Nile mosaic of Palestrina,

showing Ptolemaic Egypt (c. 100 BC) The Nile mosaic of Palestrina,

showing Ptolemaic Egypt (c. 100 BC)

Paris, Louvre Museum

Hellenistic soldiers circa

100 BC - A detail of the Nile mosaic of Palestrina

THE DEVELOPMENT

OF HELLENISTIC CULTURE |

|

The dominating role of the Greek language

With Alexander's success, the civilized "Western" world was united by a

new sense of Greek cultural hegemony. Though local peoples might

cling to their more ancient tribal or regional ways, the Greek language

and culture quickly established themselves throughout the whole of the

Eastern Mediterranean (and the hinterland) as the medium of literature,

philosophy and science.

Thus Alexander did more than any actual Greek in establishing the Greek

language as the dominant international tongue used by scholars,

scientists, tradesmen, governing officials, not only in Alexander's day

but for centuries to come. Even when Rome expanded its military

power into the Eastern Mediterranean it did not supplant Greek with its

own Latin. Indeed the Roman government itself took up the use of

Greek in administering its Eastern holdings.

The original works of Christian Scripture were not in Hebrew (which

anyway had passed out of daily use in Jesus's times) or even Aramaic (a

local Semitic language used in Syria/Palestine) ... but in Greek,

considered the only language adequate to cross the lines separating the

various cultural groups making up the Middle East. Even Paul's

letter to Rome was written in Greek, not Latin. Eventually a

translation had to be made from the Greek into Latin (the Latin

"Vulgate" translated by the monk Jerome in the late 300s, long after

Christianity had been formally accepted as the official religion of the

Roman Empire) – which the Western Church then went on to adopt as its

official translation of the original Greek.

A shift to a new sense of order in life

But this great Greek achievement came at a time of continuing confusion

among the Greeks as to what the ideals of life ought to be.

Certainly Alexander's imperial political legacy made trivial any

residual Greek affections for the city-state – though certainly such

sentiments were slow to die. The domain of politics now rested in

the hands of lofty rulers – ones who even took on the Eastern

affectation of being "gods." The noble Greek citizen directing

the course of his cherished city was now an anomaly, even a dangerous

one at that.

But even beyond these changes in political style and vision lay other

major changes in Greek life. Just as politics seemed to slip out

of the hands of the Greek commoner and move to the loftier realm of

royal, almost god-like authority, so even the sense of the source of

life seemed to move away in the same direction. Life now seemed

shaped by forces that greatly transcended direct human

management. To achieve any sort of sense of connectedness with

such transcendent sources, a person now had to look well beyond the

realm of the surrounding physical or material reality – to the mystical

realm of the Divine. True, the Greeks held on to their gods,

personal protectors whom they hoped would protect them and intercede on

their behalf with the higher forces of the universe. But

ultimately they knew that it was with these higher forces that all

things in the end drew their power, their direction, their life.

Such a realm was not necessarily hostile. It was not necessarily

chaotic. Indeed, a new Order seemed to be the rule of the

day. But it was distant, beyond the easy understanding of the

common man, mysterious in its nature and action. To reach such a

realm required enormous amounts of concentration of human thought and

understanding. Perhaps only those who had the luxury of free time

could ever achieve such a connection, such a relationship with the

ultimate.

Thus

in general, common folk turned increasingly to the mystery cults and

religions brought forward out of older times ... such as the Eleusinian

Mysteries involving the secret cults of Demeter and Persephone – cults

that reached all the way back to the Mycenean age. They also

looked to religions brought in from outside the Hellenistic world ...

such as Mithraism, a part of the Persian or Iranian Zoroastrian

tradition.

But while this tended to satisfy the general population, it seemed to

have less impact on the more educated of Hellenistic society ... who

attempted to keep alive the rich Hellenic philosophical tradition of

intellectual inquiry into the kosmos and its ways.

However Hellenistic philosophy began to take on a more complex

character. It could no longer be found just in simple dialogues

between a teacher and a citizen-student as in Socrates' days. It

now required profound devotion to study, a deep focusing of oneself on

the task, meditation, prayer even, to reach the goal of

understanding. Philosophy was now itself a mystical, spiritual

enterprise – engaged in by specialists.

A big part of that mysticism came from the deep reverence for the

starry heavens, which Greek philosophers (such as Aristotle) had been

certain presided over life on earth. Thus ongoing "scientific" study of

the heavens was supposed to bring new insights into related events on

earth ... even the power to predict the course of future events both

social and personal. Thus there was a huge development of

astrology.

However this derived not only from the research that the Greeks had

undertaken in their study of the heavens, but also from the quite

sophisticated astrological mysteries brought in from the East – thanks

to Alexander's conquest and subsequent uniting of the Asian East with

the Greek West.

In short, the mysticism of the East inserted itself deeply into the

pragmatism of the West, producing an amalgam Greek in language but

Asian in spirit which we call Hellenism.

Cynicism and Skepticism

Cynicism

and Skepticism involve two different degrees of questioning life's

underlying or fundamental order … the two philosophies being in ancient

Greek times almost the reversal of what they have come to represent

today. Today, skepticism implies that someone is holding some doubts

about how things seem to appear to be. To the skeptic, they may not be

what they seem to be. Cynicism today means having no doubts at all

about such matters … for to the cynic, nothing is ever to be trusted!

To the ancient Greek, these ideas were quite the opposite of what we

hold them to be today.

Cynicism actually started even before the Alexandrian era … most notably under the Greek philosopher Diogenes of Synope (c. 412-323 BC).

Diogenes, a contemporary of Plato and Aristotle, simply chose to escape

the world of wealth and power and try to live the simplest life

possible, such as does an animal. To Diogenes, the life of a dog

(Greek: kuon or kyon, from which the word "cynic" is derived) has

greater integrity than the life of the wealth-and-power-grasping

human. But like his contemporaries, Plato and Aristotle, Diogenes

still believed that it was possible, by deciding to go down the right

road in life, to come to excellence as a person. In short, he was not

at all cynical about human possibilities … though skeptical at times!

He truly believed that there was hope that humankind could pull out of

the mess he was observing around him in his pre-Alexandrian Greece. |

Diogenes the Cynic in his tub - by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1860)

Walters Art Museum - Baltimore

But in the post-Alexandrian world, that optimism seemed to fade away. Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360-270 BC)

took on something similar to a Buddhist or Hindu attitude in concluding

"skeptically" that true knowledge, true goodness, true anything, was

humanly unattainable. He felt that life would be simpler and

happier if people simply gave up trying to find perfection … and

accepted the fact that life has its times of grand disappointment as

well as moments of glory – and that there is little that we can do to

determine those results. Also to Pyrrho, simply following tradition –

rather than trying to come up with new, more progressive ideas

intellectually – worked better for everyone in the long run. But in the post-Alexandrian world, that optimism seemed to fade away. Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360-270 BC)

took on something similar to a Buddhist or Hindu attitude in concluding

"skeptically" that true knowledge, true goodness, true anything, was

humanly unattainable. He felt that life would be simpler and

happier if people simply gave up trying to find perfection … and

accepted the fact that life has its times of grand disappointment as

well as moments of glory – and that there is little that we can do to

determine those results. Also to Pyrrho, simply following tradition –

rather than trying to come up with new, more progressive ideas

intellectually – worked better for everyone in the long run.

But exactly what those more useful traditions actually happened to be

Pyrrho never clarified … leaving the matter for the individual to

decide. Ultimately, there was nothing to keep a skeptic from

disavowing all intellectual standards and simply following a life of

wantonness.

Epicureanism

Epicurus (342-270 BC)

was not actually the "eat, drink, and be merry" individual that we

associate with being an "Epicurean" today. He did however

certainly support the idea of the pursuit of pleasure. But to

him, such pleasure was found in a life free of pains and hurts, because

a person has chosen to live a life of virtue. But what that life

of virtue actually consisted of Epicurus was not of Socrates's variety

… that is, of finding the higher realm of truth and goodness and then

staying focused on living according to those standards. Rather,

to Epicurus, the definition of the virtuous life that brings real

pleasure was a rather subjective one … not really anchored on standards

lying above an individual's own preferences on the matter. In

short, because to Epicurus pleasure was purely subjective, a person was

easily led to the understanding that whatever a person craves is the

ultimate good for that person. Epicurus (342-270 BC)

was not actually the "eat, drink, and be merry" individual that we

associate with being an "Epicurean" today. He did however

certainly support the idea of the pursuit of pleasure. But to

him, such pleasure was found in a life free of pains and hurts, because

a person has chosen to live a life of virtue. But what that life

of virtue actually consisted of Epicurus was not of Socrates's variety

… that is, of finding the higher realm of truth and goodness and then

staying focused on living according to those standards. Rather,

to Epicurus, the definition of the virtuous life that brings real

pleasure was a rather subjective one … not really anchored on standards

lying above an individual's own preferences on the matter. In

short, because to Epicurus pleasure was purely subjective, a person was

easily led to the understanding that whatever a person craves is the

ultimate good for that person.

Epicurus also believed that we were wasting our time speculating on the

nature of some kind of higher realm, especially one that perhaps

follows death, that we would do well simply to explore the

material-mechanical world around us … and make the most of that

practical or physical world.

Stoicism

Stoicism actually had its origins in Cynicism … although Zeno of Citium (336-264 BC)

took the matter well beyond a simple retreat from the material world in

to a life of simplicity. Zeno, who came to Athens to teach his

ideas to students gathered under him at the Stoa (Porch) located in the

Athenian marketplace (thus "Stoicism"!) believed that there was great

purpose in bringing to anyone's life the practice of deep contemplation

about the mysteries of the world … bringing human life under such

mystical discipline in order to truly free up that life. Stoicism actually had its origins in Cynicism … although Zeno of Citium (336-264 BC)

took the matter well beyond a simple retreat from the material world in

to a life of simplicity. Zeno, who came to Athens to teach his

ideas to students gathered under him at the Stoa (Porch) located in the

Athenian marketplace (thus "Stoicism"!) believed that there was great

purpose in bringing to anyone's life the practice of deep contemplation

about the mysteries of the world … bringing human life under such

mystical discipline in order to truly free up that life.

Following something of a Socratic or Platonic tradition, Zeno was

confident that there existed some kind of Divine Reason (the Logos), an

ultimate reality beyond mere physical appearances. Thus he taught

that the human mind could – and most certainly should – attach itself

to this Logos in pure devotion.

He also taught (in strong distinction to Epicurus) that we should bring

our personal cravings under the mastery of a mind-over-matter

life. In the face of life's many difficulties, this was

particularly important … that is, important to stay focused on the

Logos – and not the worries or hurts of the moment. This

"quietism" ultimately became the hallmark of the Stoic.

Most interestingly – perhaps because it offered such hope to a world

that seemed to find little logic in the way political and social

affairs seem to be moving at the time – Stoicism soon became a

widespread philosophy across the Greek world. It would even make

its way into the Roman realm.

The development of the physical sciences

But at the same time, the larger Alexandrian world seemed to offer a

new sense of order … or at least point to the possibility of one being

achieved – in the same way that Alexander had so quickly achieved so

much.

Thus Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310-230 BC)

came to have a very lofty view of the universe, even as a young man

publishing a work (lost to us today) declaring that the sun was 19

times the size and distance of the moon (actually the figure is about

400 times the size and distance) – something that seemed to defy the

common sense of his times that the sun and moon differed only in the

intensity of their light, not their size and distance. He even

stated that the sun was much larger than the earth … and therefore it

was most likely that the smaller earth circled the larger sun (the

heliocentric theory), rather than the reverse (the geocentric theory) –

as it was viewed at the time. Of course all of this was

ridiculed in Aristarchus's day … though defended and promoted (a

century later) by Seleucus. But sadly, it ultimately got dropped

in Western thinking for the longest time. Thus Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310-230 BC)

came to have a very lofty view of the universe, even as a young man

publishing a work (lost to us today) declaring that the sun was 19

times the size and distance of the moon (actually the figure is about

400 times the size and distance) – something that seemed to defy the

common sense of his times that the sun and moon differed only in the

intensity of their light, not their size and distance. He even

stated that the sun was much larger than the earth … and therefore it

was most likely that the smaller earth circled the larger sun (the

heliocentric theory), rather than the reverse (the geocentric theory) –

as it was viewed at the time. Of course all of this was

ridiculed in Aristarchus's day … though defended and promoted (a

century later) by Seleucus. But sadly, it ultimately got dropped

in Western thinking for the longest time.

Then there was Eratosthenes (c. 276-192 BC),

the head librarian at the huge museum and library of Alexandria Egypt,

who conducted an unheard-of experiment in calculating the curvature of

the earth by measure the length of shadows at the exact same moment in

two different locations in Egypt … and came up with a figure that gave

the earth the estimate of being (by today's measurements) 24,660

miles in circumference … only 200 miles less than the actual

measure! He also made the bold claim that a person could

theoretically sail around the world and arrive back at the same staring

point, provided that he never changed course along the way. And

additionally, he cataloged nearly 700 stars … as well as a system of

calculating prime numbers. Then there was Eratosthenes (c. 276-192 BC),

the head librarian at the huge museum and library of Alexandria Egypt,

who conducted an unheard-of experiment in calculating the curvature of

the earth by measure the length of shadows at the exact same moment in

two different locations in Egypt … and came up with a figure that gave

the earth the estimate of being (by today's measurements) 24,660

miles in circumference … only 200 miles less than the actual

measure! He also made the bold claim that a person could

theoretically sail around the world and arrive back at the same staring

point, provided that he never changed course along the way. And

additionally, he cataloged nearly 700 stars … as well as a system of

calculating prime numbers.

Tragically these amazing discoveries did not fit well with the

preconceptions of the times … and were dismissed by other

intellectuals.

For instance, Hipparchus (fl. 145-130 BC)

argued strongly against Aristarchus's heliocentric theory … pointing out

that there were serious problems mathematically with the theory.

Of course, neither he nor Aristarchus had taken into account the

gravitational effect of the sun's surrounding planets or the elliptical

way that things seemed to move in the heavens. That would come

only many, many centuries later. Thus it was that he would help

the mathematician Ptolemy (fl. early 100s AD) use very complicated

mathematical formulas to put the earth back at the center of

things … the geocentric theory that would last all the way to the time

of the West's Renaissance in the 1500s (Copernicus) and the early 1600s

(Brahe, Galileo, and Kepler).

Mathematics was another field of great accomplishment, Euclid (fl. c. 300 BC) putting together in his Elements,

a clear and precise explanation of the laws of geometry … used all the

way down to modern times as the model for that mathematical

field. And there was Archimedes of Samos (c. 310-230 BC) who

in his Sand Reckoner (212 BC) not only laid out the major laws of

engineering and physics … but was able to put those to use in helping

his native city of Syracuse defend itself using his clever inventions

against besieging Romans (although tragically the Romans won

anyway). Interestingly also, he came very close to inventing the

calculus, something not finally attained until 1,900 years later

(Newton and Leibniz).

Euclid Archimedes

|

Go on to the next section: Society and Culture of the Roman Republic

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | | |

A general overview of the Hellenistic

A general overview of the Hellenistic Alexander ... and his conquest of the

Alexander ... and his conquest of the Alexander's Empire is carved up

Alexander's Empire is carved up

The Seleucid Empire in the East

The Seleucid Empire in the East

The development of Hellenistic culture

The development of Hellenistic culture

Though

Alexander's power was clearly based on the support of his very

practical-minded Macedonian-Greek army, Alexander soon began to

envision himself as a great Oriental god-king sent to rebuild

civilization in what he supposed was the entire reach of the

world. He planted cities with Greek colonists wherever he went,

urged his soldiers to take wives from among the Persians and other

Oriental peoples (as he himself did in marrying the Bactrian princess,

Roxana), and did what he could to rebuild Western Asian civilization on

a mix of Greek and Oriental culture. His loyal troops humored him

in his thoughts, though they themselves were very unlikely candidates

for ever seeing Alexander as a god – as the Orientals so easily came to

see their new ruler.

Though

Alexander's power was clearly based on the support of his very

practical-minded Macedonian-Greek army, Alexander soon began to

envision himself as a great Oriental god-king sent to rebuild

civilization in what he supposed was the entire reach of the

world. He planted cities with Greek colonists wherever he went,

urged his soldiers to take wives from among the Persians and other

Oriental peoples (as he himself did in marrying the Bactrian princess,

Roxana), and did what he could to rebuild Western Asian civilization on

a mix of Greek and Oriental culture. His loyal troops humored him

in his thoughts, though they themselves were very unlikely candidates

for ever seeing Alexander as a god – as the Orientals so easily came to

see their new ruler.

This

eventually brought Mark Antony into a relationship where he and

Cleopatra openly became lovers (including the birthing of three

children) ... despite the fact that Mark Antony was married to

Octavian's sister, Octavia. This would become part of the reason

for a growing split between the former allies Octavian and Mark

Antony. By 33 BC the two Roman leaders were in full conflict with

each other and in 31 BC, in a major battle at Actium, Octavian's forces

decisively defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

This

eventually brought Mark Antony into a relationship where he and

Cleopatra openly became lovers (including the birthing of three

children) ... despite the fact that Mark Antony was married to

Octavian's sister, Octavia. This would become part of the reason

for a growing split between the former allies Octavian and Mark

Antony. By 33 BC the two Roman leaders were in full conflict with

each other and in 31 BC, in a major battle at Actium, Octavian's forces

decisively defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra.