8. THE EUROPEAN RENAISSANCE AND REFORMATION

RENAISSANCE CULTURE

RENAISSANCE CULTURE

The Renaissance: An overview

The Renaissance: An overview

Renaissance philosphy and literature

Renaissance philosphy and literature

The Greats: Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and

The Greats: Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and

Raphael

Other architectural greats of the Italian

Other architectural greats of the Italian

Renaissance

The lifestyle of the Florentine upper-

The lifestyle of the Florentine upper-

bourgeoisie

Renaissance art in Northern Europe -

Renaissance art in Northern Europe -

The 1400s

Renaissance art in Northern Europe -

Renaissance art in Northern Europe -

The later years

Renaissance architecture in Northern

Renaissance architecture in Northern

Europe

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 275-286.

THE

RENAISSANCE: AN OVERVIEW |

|

A Time of Transition

Though there was no specific event to mark the end of the middle ages and the on set of the modern era, the 1400s seem to be the all important transition time. This period of transition into modernity, known today as the "Renaissance," was based heavily in Italy, especially the cities of Venice, Florence, Siena, Mantua, Pisa, Milan, Urbino, Rome and Naples – but was also found in significant portions of Northern (mostly coastal) Europe ... through the natural links that commerce produced and by scholars who studied in Italy and took its learning north. Thus in addition to a number of vibrant Italian cities, the Renaissance also extended to Bordeaux and Paris (France), London and Bristol (England), Bruges and Antwerp (Flanders) and the coastal German cities (such as Lübeck and Hamburg) of the Hanseatic League ... among a number of other European cities. On the face of it, it appears that the Renaissance was essentially an economic affair – consequently, a rapid growth of commercial wealth that aided greatly in producing an intellectual revival in the form of a strong interest in pre Christian Greco Roman philosophy, in a dazzling flowering of the fine arts (painting, sculpture, architecture) ... dedicated to the glorification of man and his talents ("humanism") rather more than God and his traditional role in the Christian world. All of this wealth in trade flowing to the rising European cities would change deeply the way Christians or "Westerners" formed social bonds in order to advance and defend life. In general the merchant cities of Europe went at the matter of acquiring new powers differently than did the princes, the latter tending to see politics as a rather personal matter, something impacting their own status as grand landowners, as overseers of the masses of peasants working those lands for them … and personally as the primary benefactors of the wealth this system provided. The rising cities went at life with a different attitude directing them. Like the richest of all of them, the Republic of Venice, urban politics tended to be corporate, drawing into the position of leadership a wider circle of local interests than the single individual dominated kingdoms and principalities. Most cities were run or managed by a corporate council ... led by individuals elected to office on a regularly recurring basis by committees or guilds of tradesmen and manufacturers. Urbanites were also a different breed of Europeans. Their business world required the ability to read, write and perform complicated mathematical processes (at a time when the rural feudal princes of the vast European countryside were often illiterate, reading and writing not being a very important factor in their rule). Their urban world was also larger than the traditional world of rural feudal Europe. Travel and business connections abroad – not to mention the ability to read and write – gave them a much bigger understanding of how the world works. Europe's urbanites were an independent minded lot, adventurers and risk takers, and always a potential challenge to the medieval ways of rural feudal Europe. But they were tolerated, even encouraged, by local princes in whose territory these cities found themselves located. They were, after all, a source of mobile or moneyed wealth ... increasingly more important to local princes and their ambitions than the feudal vassals who were supposed to offer full support at the princes" command ... but who proved most unreliable in times of real need. So the princes “chartered” the cities ... contracting with them to receive tax monies in exchange for the prince's support of their rather independent ways that the cities required in order to do business successfully. Once a prince or king granted a city its charter, it had full rights to operate as it saw fit. Needless to say, cities guarded jealously those chartered rights. But also kings tended to respect carefully those rights ... because they depended so much on their cities" financial support. Nonetheless this shift in the local political scene still had its dangers. The independence of these towns – in keeping with their actual power in this early stage of development – did not provide the air of legitimacy that they needed to feel secure in their liberties within the newly rising order. At any time these urban charters might be revoked by the local prince or bishop by any whim or fancy (or suspicion). There really was no "right" of their own that the towns could hold up to these lords in order to demand equitable treatment, at least not until the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s gave them the sense that they had the right to accept or reject political authority in accordance with what their own consciences dictated. There was no power on earth, only God alone, who had the right to judge them in matters of conscience, even political conscience. But in any case, the rapid growth of the trade in European goods called forth industrial growth – and industrial growth called forth new technologies. The number of inventions from newly emerging European inventive minds was phenomenal. But a few stand out – not only because they added so much to industrial development but because they also came to have such a profound impact on the European mindset or spirit. The clock, with its carefully interworked systems of gears and wheels, seemed to serve as a symbol of the new sense of order which underpinned the whole universe – an order which existed by its own right. Likewise the compass gave the traveler, especially the new bold class of seafarers, as sense that life had key foundation points – which man of his own could fathom and use for himself. But there is no question that the one technological development that most revolutionized the times was the invention of the printing press. In around 1450 Johannes Gutenberg introduced the new printing process (moveable type) which revolutionized the production of written material – using this new process to produce his amazingly high-quality Gutenberg Bible (in the Latin or Vulgate). The printing process would soon revolutionize the printing and distribution of the Bible in the various European languages actually spoken at the time. Thus a wide number of local-language translations of the Vulgate Bible soon began to appear in widely available printed form: German (1466), Italian (1471), Dutch (1477) Spanish (1478 – but subsequently suppressed), French (1487), and Czech (1488). Tyndale's English translation, the first printed English translation, did not come out until much later,1 around 1525 – after much resistance from the Church and from English King Henry VIII (Tyndale was eventually executed for this "crime"). Oddly enough, only four years after Tyndale's execution, Henry VIII authorized his English-language Great Bible to be published … a translation based largely on Tyndale's work! The 1400s mark both a definite continuity with the long development of Western Christian culture … and yet at the same time a strong departure from many of the ways the Christian community had understood the cosmos around it. The Christian mind had long (a thousand years) seen the sweep of history in a profoundly dualistic fashion: there were the times before Christ and the times since then. Everything before Christ's appearance in history (Before Christ or "BC") had meaning for them only as preparation for this grand event. Everything since that event (Anno Domini – the Year of the Lord … or "AD") was measured in terms of how it gave fulfillment to God's plan of salvation for human life. Christians traditionally had been certainly mindful of the importance of Rome. It seemed to them to be no mere coincidence that Rome reached its greatness (presumably in the reign of Augustus) at about the time Christ was born. To the Christian mind, this was God's way of preparing the civilized world physically to receive the gospel. They were aware of many of the unique features of Roman thought – but either they dismissed that thought as a carryover from darker days – or as metaphor, pointing to and confirming the gospel message. Thus they read Virgil, Ovid, Cicero, Livy with a profoundly Christian interpretation of the meaning of their works. So also did they understand Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. But by the 1400s, without dismissing their Christian loyalties or pieties, the Renaissance mind was looking back on the days of Greece and Rome through a new set of eyes. There had been growing, since the early 1300s (perhaps even earlier) a fascination with Roman ways in themselves, without having to go through some kind of Christian interpretation. This was timed with the reaction against scholasticism as an arid, intellectually arrogant ambition of the human reason to bring all things under systematic theological mastery. This was timed with a desire to explore more deeply the "humane" features of human life: the simple passions, the loyalties, the love that connected human life with God and Christ – and with the rest of the human community. Things came to be of interest in themselves to the enquiring European mind as it moved through the 1300s and entered the 1400s. They came to be of interest not because they conformed to some great intellectual system but because they gave life to human existence. Thus did they now approach Virgil, Ovid, Cicero, Livy – not to further undergird a well rehearsed medieval world view, but to listen to them speak out of their own times, as fellow humans trying to find in life the same deeper qualities of human existence. Having discovered this wealth of ancient human testimony and being deeply touched by the profundity of its spirit – pagan it might be (certainly was!) – they began to detach themselves all the more from the "darker" Christian mood of the centuries that stood between themselves and that "golden age" 1000 years earlier. They saw history now not as some form of single Christian continuum, but as time in which the once greatness of Roman civilization was lost and was now, a thousand years later, being rediscovered. We need to make note at this point that who we are talking about in reality composed only a tiny minority of the people of those days. By and large the mass of the Europeans living in those times probably retained the older medieval world view. When we are talking about the "Renaissance mind" we are describing a small group of wealthy and powerful businessmen, an equally small number of intellectuals, both secular and religious, and a small, curious group of adventurers. However, though small in number, they were very powerful in terms of shaping the events of their day. In any case, it is to them that we look when we describe the Renaissance mind. Though these individuals remained Christian to the core, they began to take a dimmer view of the way that their faith had been mediated by the Church during a 1000 year "dark ages." They instead sought to validate their Christian faith on the basis of personal loyalties and personal virtue. These people were doers – who used their minds in service to the needs of the family and local community – the "patria" as they understood it. They were not contemplatives; monastic life was not for them a Christian ideal. They were not knights living to honor the code of chivalry; that was much to abstract a notion for them. They were practical, "earthy" in their interests, and sought to use their considerable worldly talents for the common good. This was their understanding of their Christian responsibilities, their accountability before God. The church was finding itself hard-pressed to maintain its traditional place of authority within the European cultural sphere. It tried to resist its loss of status – but found that circumstances were making it increasingly difficult to hold its own. For instance, the translation of the Bible from Latin into the languages of the people gave them the power to discern for themselves the word of God. Through the rapid growth of literacy that accompanied the growth in Bible and other book publication this development became quite extensive. Thus the church became very alarmed by the publication of the Bible – more alarmed that it was over the publication of pagan Roman and Greek literature – protesting that this wide dissemination of the Bible would cause the emergence of wrong interpretations and subsequently the spread of new heresies. The church well understood that it was thus rapidly losing its monopoly on learning and authoritative knowledge. Also, with the rise of the secular, humanist spirit, especially in Italy, religion was becoming seen more and more as a matter of internal religious disposition of the individual, and less and less as a matter of the sacraments, teachings and traditions dispensed by the church. Yet interestingly, many of the church leaders themselves chose to join in with the spirit of the times. Certainly there were those clergy who objected. But by and large the view of the church – notably of its popes, who during the 1400s could be very worldly fellows – was that this intellectual revolution was something to be pursued. Thus the church was as active a sponsor in this matter. Indeed, the worldliness of the church was becoming a well-recognized feature. The Roman hierarchy was viewed widely as being venal and corrupt – as secular politics rather than spirituality preoccupied the popes of the 1400s. The dreams and schemes of the Roman church became more grandiose, overstepping even the wealth of Italy, and beginning to drain the wealth of the church north of the Alps. And the personal conduct within the highest offices of the church, including the papacy itself, was at times scandalous. Discontent against the Roman church thus began to spread in the North of Europe by the end of the 1400s. Led especially by a number of northern humanists, many Europeans began to demand reform the church, not only in its ethical behavior but also in its very lines and features as an institution. Reform-minded individuals were beginning to demand that the church should drop its medieval trappings and purify itself along the lines of the early church described in scripture. 1Copies of Wycliff's English Bible (completed around 1384) in manuscript form also were circulated widely – although not in printed form until the early-to-mid 1500s.

Detail of the Angel Appearing to Zacharias – by Domenico Ghirlandaio

(1486-1490) – depicting four prominent members of the Platonic Academy in Florence (left to right):

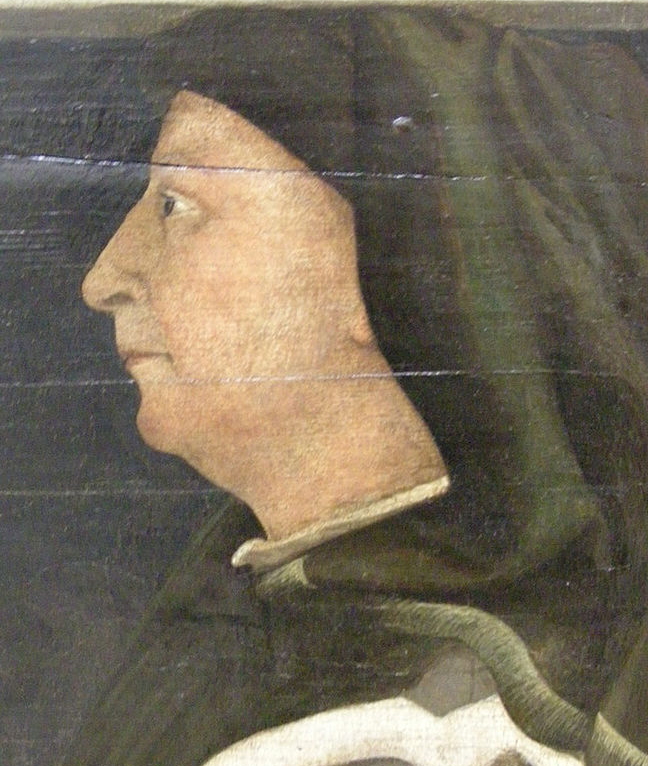

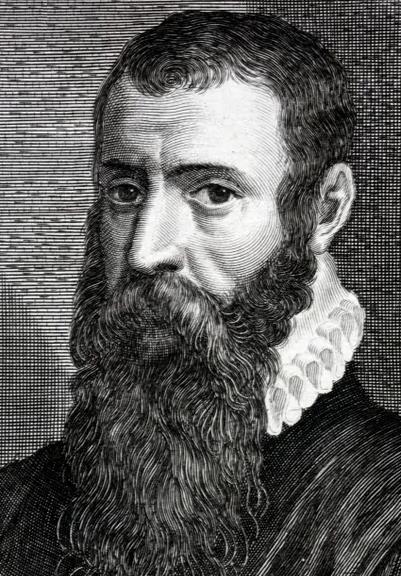

Young Niccolo Machiavelli - by Santi di Tito

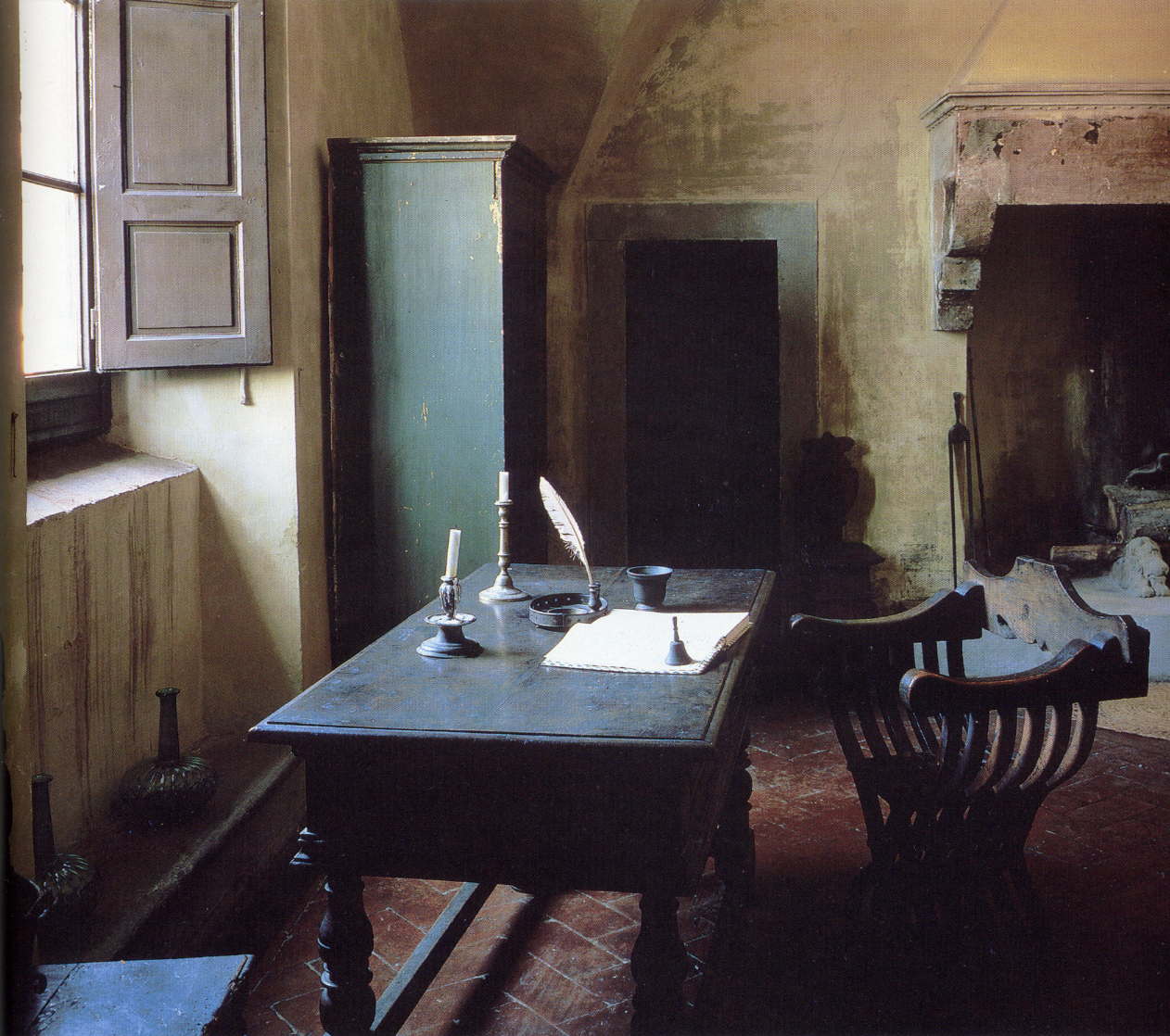

Florence, Palazzo Vecchio Machiavelli's study at his

country villa at Percussina where he penned The Prince

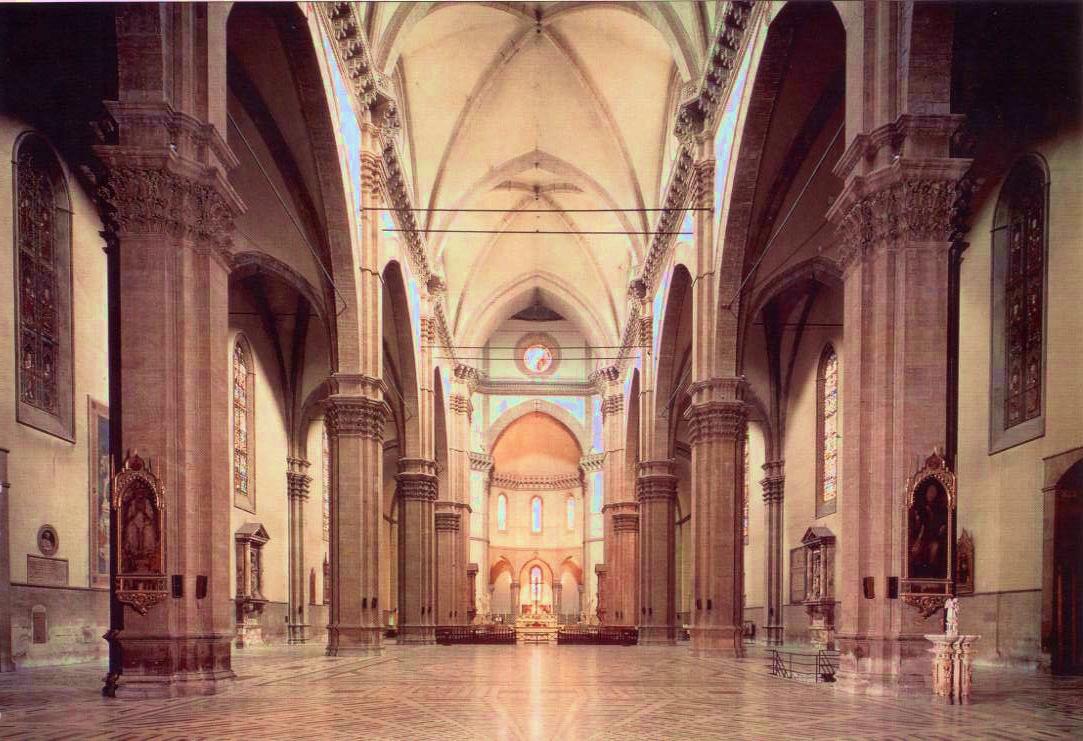

Filippo Brunelleschi's Santo Spirito – Florence (1430s)  Florence's Duomo or cathedral: The Santa Maria del Fiore, with Brunelleschi's dome or cupola (1420s and 1430s) .. and Giotto's campanile or bell tower (1330s) The interior of the Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore

Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello

greatbuildings.com

greatbuildings.com

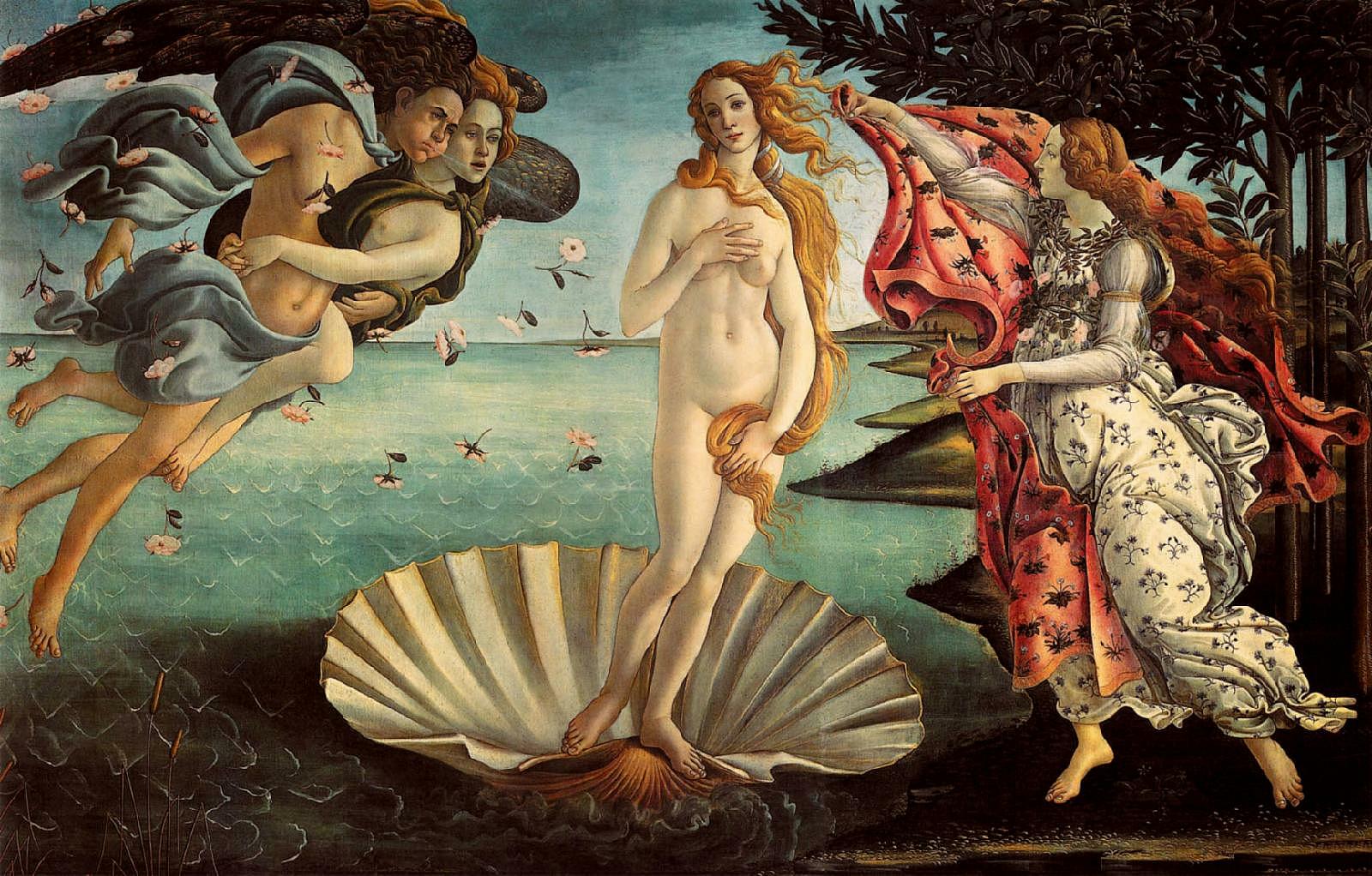

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi

Scala, Florence Städelsches Kunstinstut, Frankfurt

Other quite notable Italian Renaissance artists  The "Gates of Paradise" ...

doors to Florentine cathedral's

baptistry - by Lorenzo Ghiberti (early 1400s)

The "Gates of Paradise" ...

doors to Florentine cathedral's

baptistry - by Lorenzo Ghiberti (early 1400s)

Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Florence, Palazzo Pitti

Bergamo, Accademia Carrara

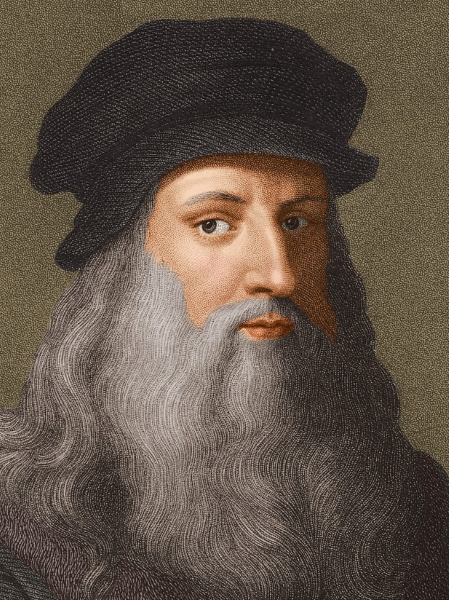

Leonardo da Vinci's self-portrait

(ca. 1512)

A younger da Vinci Leonardo da Vinci's Last

Supper Leonardo da Vinci's Last

Supper – restored Da Vinci's Mona

Lisa

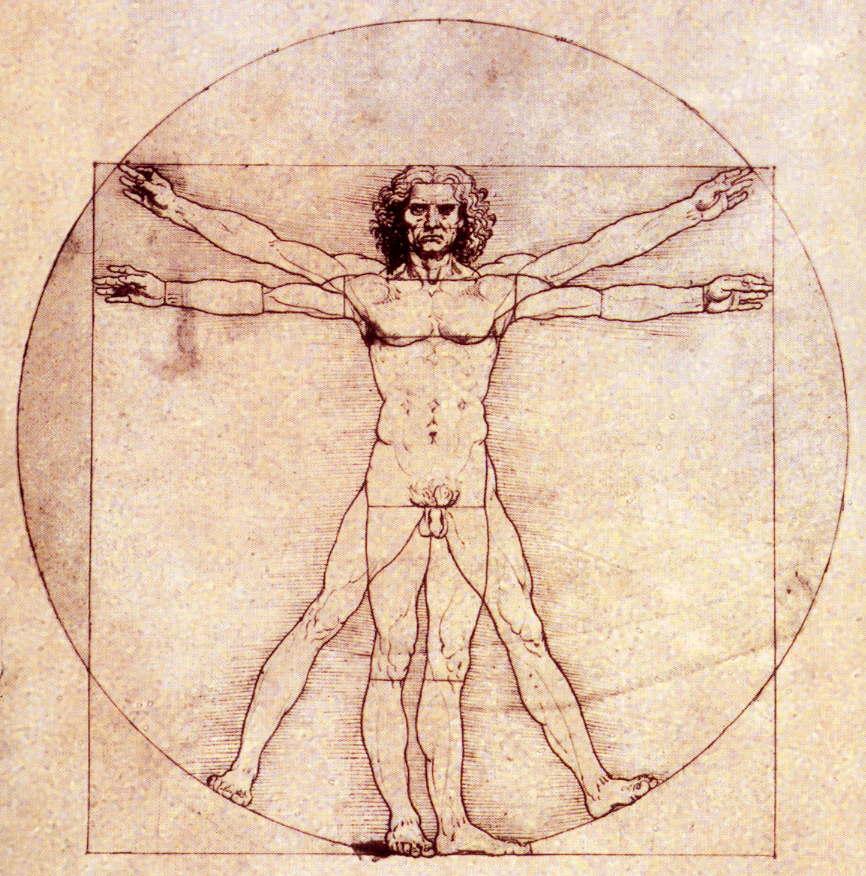

The Vitruvian Man (c. 1485)

From Leonardo da Vinci's

studies of flowers

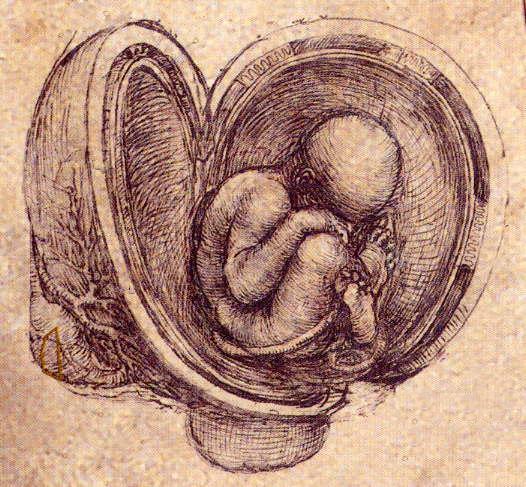

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a fetus in utero

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of an assault vehicle

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a life preserver

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a type of helicopter

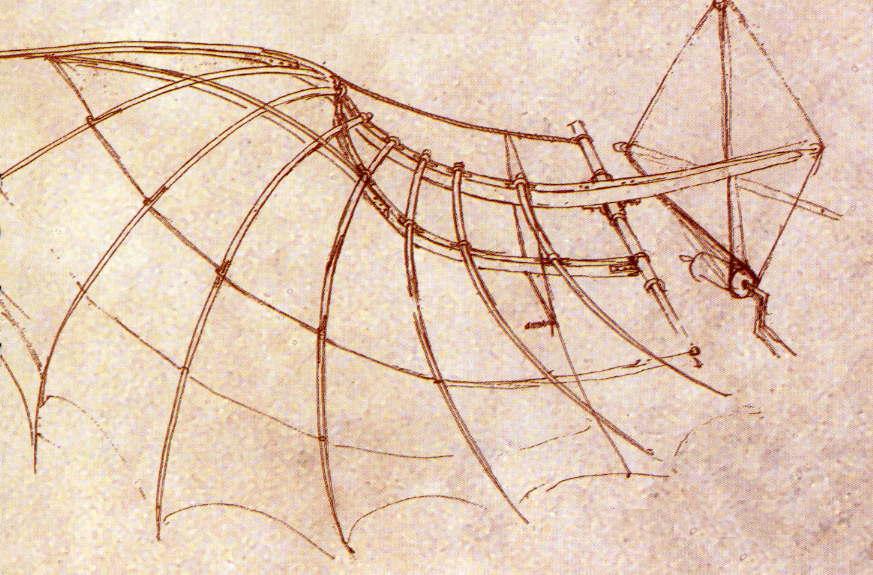

Leonardo da Vinci's sketch

of a mechanical hand-cranked wing

Michelangelo Buonarroti Michelangelo Buonarroti –

bust by Daniele da Volterra Michelangelo's

Pietà Michelangelo Buonarroti

– David (1501-1504) marble

in his design of the Vatican's renovated St. Peter's Cathedral in Rome

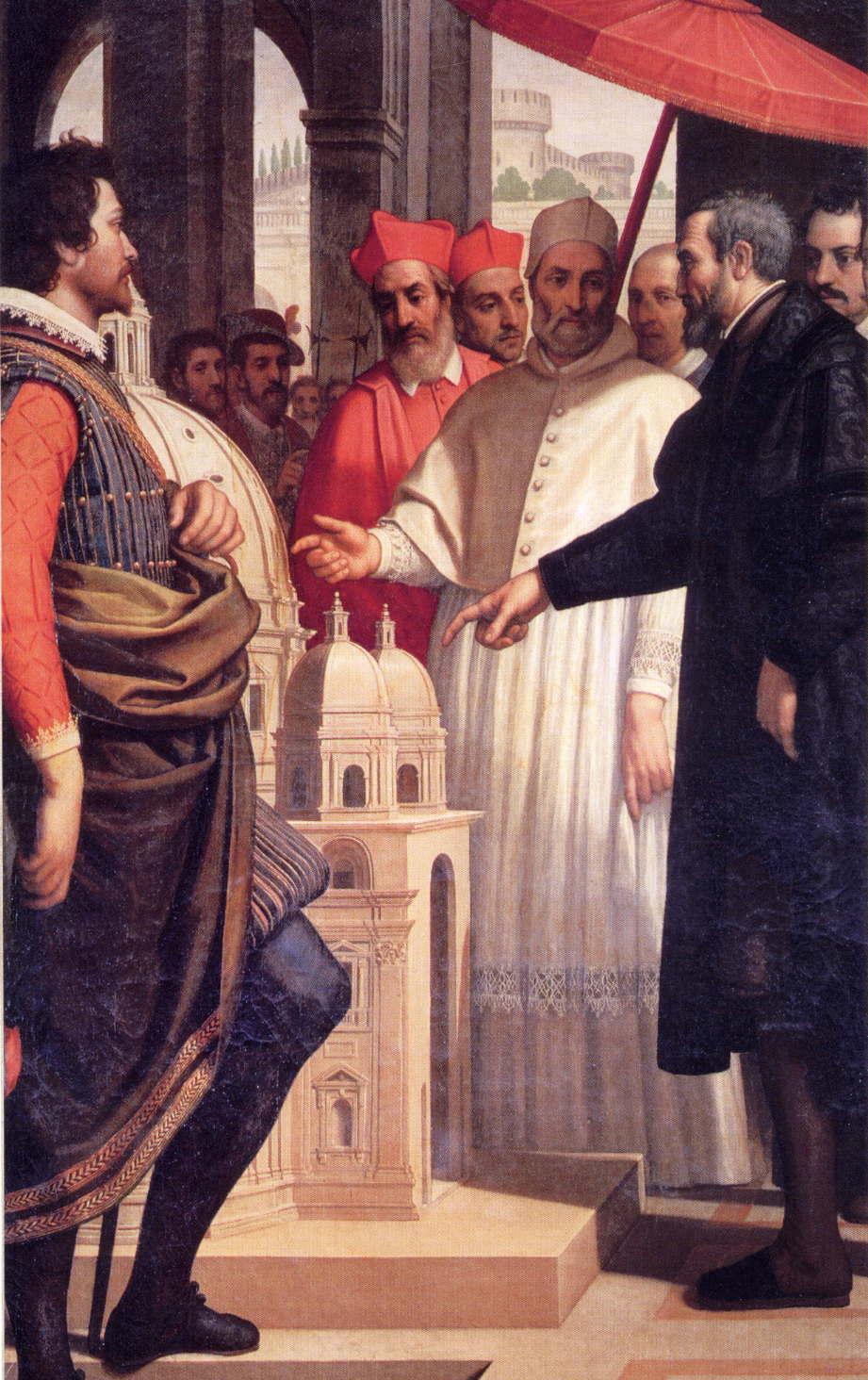

Michelangelo, Bramante and

Raphael meet with Pope Julius II

Michelangelo eventually presents Pope

Paul IV his model of the St. Peter's Cathedral The Sistine Chapel

The ceiling of the Sistine

Chapel – completed by Michelangelo in 1512

The Delphic Sybil – detail

from the Sistine chapel ceiling

| Raphael Sanzio (1483-1520)

Raphael was another Renaissance artist and architect of great note … even at the early age of eleven, taking up his father's court painting business in Urbino when his father died. His early works brought him such attention that in 1508 Pope Julius II had him come to Rome to undertake the production of murals for the pope's library … later known as the "Raphael Rooms"! Among those murals was his famous School of Athens (1509-1511), Raphael – strongly influenced in style by Michelangelo's work on the Sistine Chapel at that same time – actually using individuals of his day (Michelangelo and da Vinci, for instance) to represent these ancient figures! From this point on, Raphael would be kept busy (until his early death at age 37) by subsequent popes working on various projects in the reworking of the Vatican buildings. These three artists – da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael – would influence deeply the character of Italian art (and elsewhere) for the next several generations. |

Raphael Sanzio

Raphael Sanzio –

Portrait

of Agnolo (above) and Maddalena (below) Doni (1505-1506) oil on panel

Florence, Palazzo Pitti

Raphael Sanzio –

Madonna

of the Meadow (1506) oil on panel

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches

Museum

Raphael Sanzio – The

School

of Athens (1509-1511) oil on panel

Vatican City, Apostolic

Palace

Raphael Sanzio –

Baldasare

Castiglione (1514-15) oil on panel

Paris, Musée du

Louvre

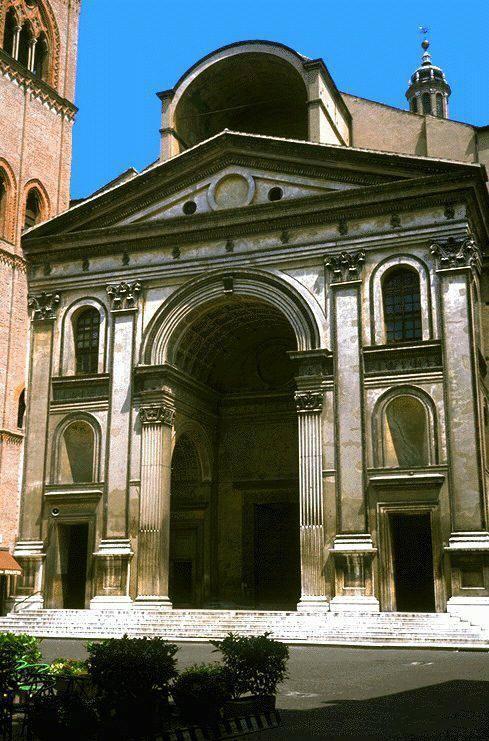

OTHER ARCHITECTURAL GREATS OF THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE |

Andrea Palladio's Villa Rotonda (near Vicenza)

The Palazzo

Medici

Giuliano da San Gallo – Villa

Poggio, Caiano, Tuscany

constructed for Lorenzo

de' Medici, 1480-1485

THE LIFESTYLE OF THE FLORENTINE UPPER BOURGEOISIE |

The Palazzo Davanzati – a typical home of the Florentine elite

The Palazzo Davanzati – entry hall

The Palazzo Davanzati – staircase in the inner court

The Palazzo Davanzati –

the

second floor grand salon (overlooking the street)

The Palazzo Davanzati – the Room of the Parrots

The Palazzo Davanzati –

the

upper-floor kitchen

(located there to keep smoke

and odors out of the house)

The Palazzo Davanzati – one of the bedrooms at the rear of the house

The Palazzo Davanzati

– another bedroom

RENAISSANCE ART IN NORTHERN EUROPE |

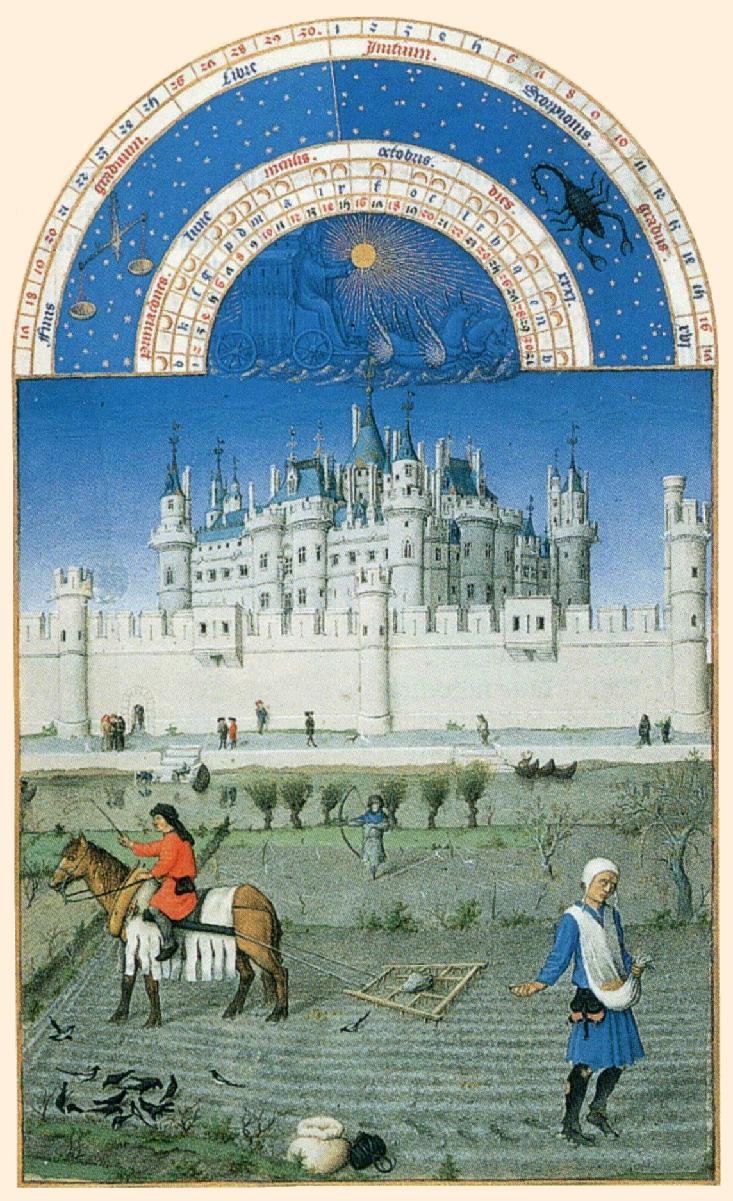

The Limbourg Brothers (Jean and ) late 1300s and early 1400s

Jean de Limbourg – Les

Très

Riches Heures du duc de Berry – October (1413 - 1416)

Chantilly, Musée

Condé

Enguerrand Quarton –

The

Villeneuve-les-Avignon Pieta (c. 1455) oil on panel

Paris, Musée du

Louvre

Jean Fouquet – Virgin

and Child surreounded by Angels (after 1452) tempera on panel

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum

voor Schone Kunsten

FLANDERS

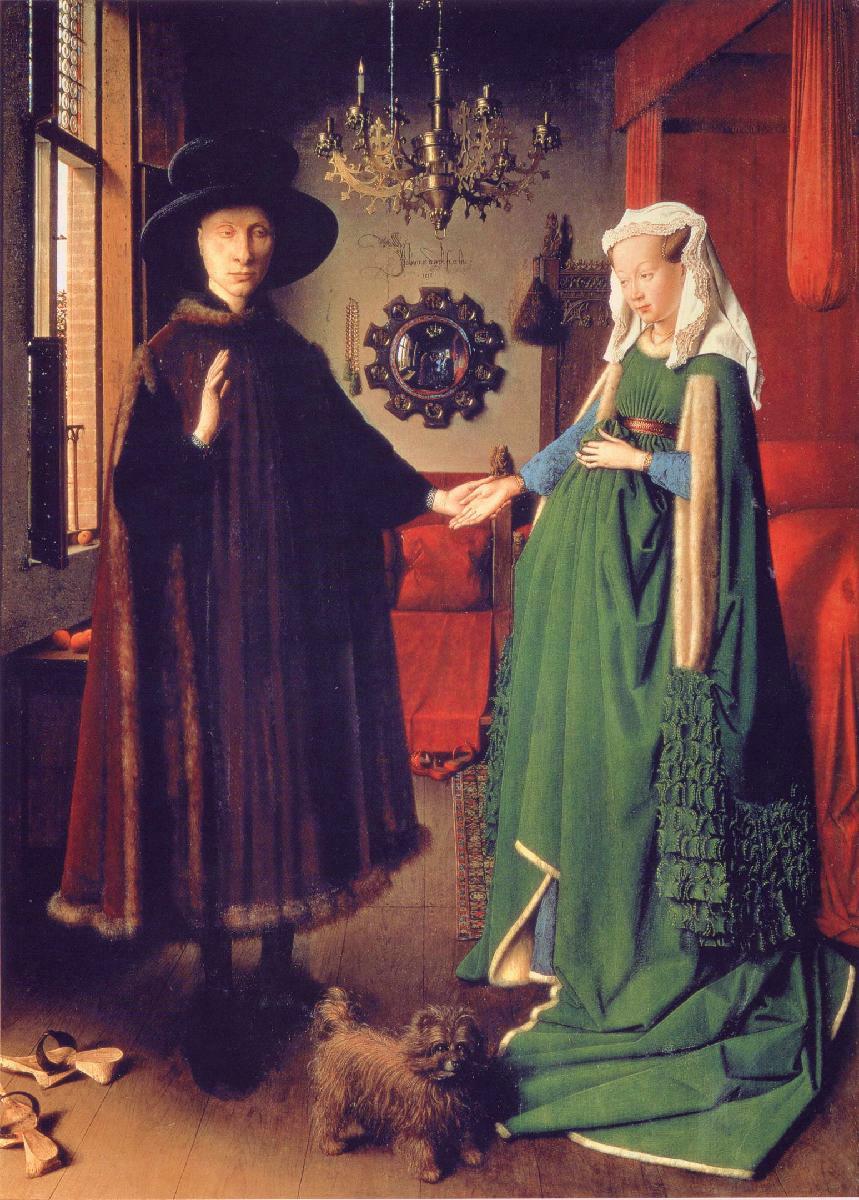

Jan Van Eyck – The

Marriage

of Giovanni Arnolfini and Giovanna Cerami (1434)

London, National

Gallery

Rogier Van der Weyden –

The

Descent from the Cross (c. 1435) oil on panel

Madrid, Museo del

Prado

Konrad Witz – The

Miraculous

Draught of Fishes (1444) oil on panel

Geneva, Musée d'Art et

d'Histoire

Stefan Lochner – The

Virgin

of the Rose Bush (c. 1440) oil on panel

Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz

Museum

RENAISSANCE ART IN NORTHERN EUROPE – THE LATER YEARS |

FRANCE

Tomb of Philippe Pot, Seneschal

of Burgundy (c. 1480)

From the abbey church of

Citeaux

Paris, Musée du

Louvre

FLANDERS

Hugo van der Goes - The

Portinari tryptich (c.

1475)

Florence, Galleria degli

Uffizi

Hans Memling –

Triptych

of St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist (c. 1474-1479)

oil on panel

Bruges, Hôpital Saint-Jean

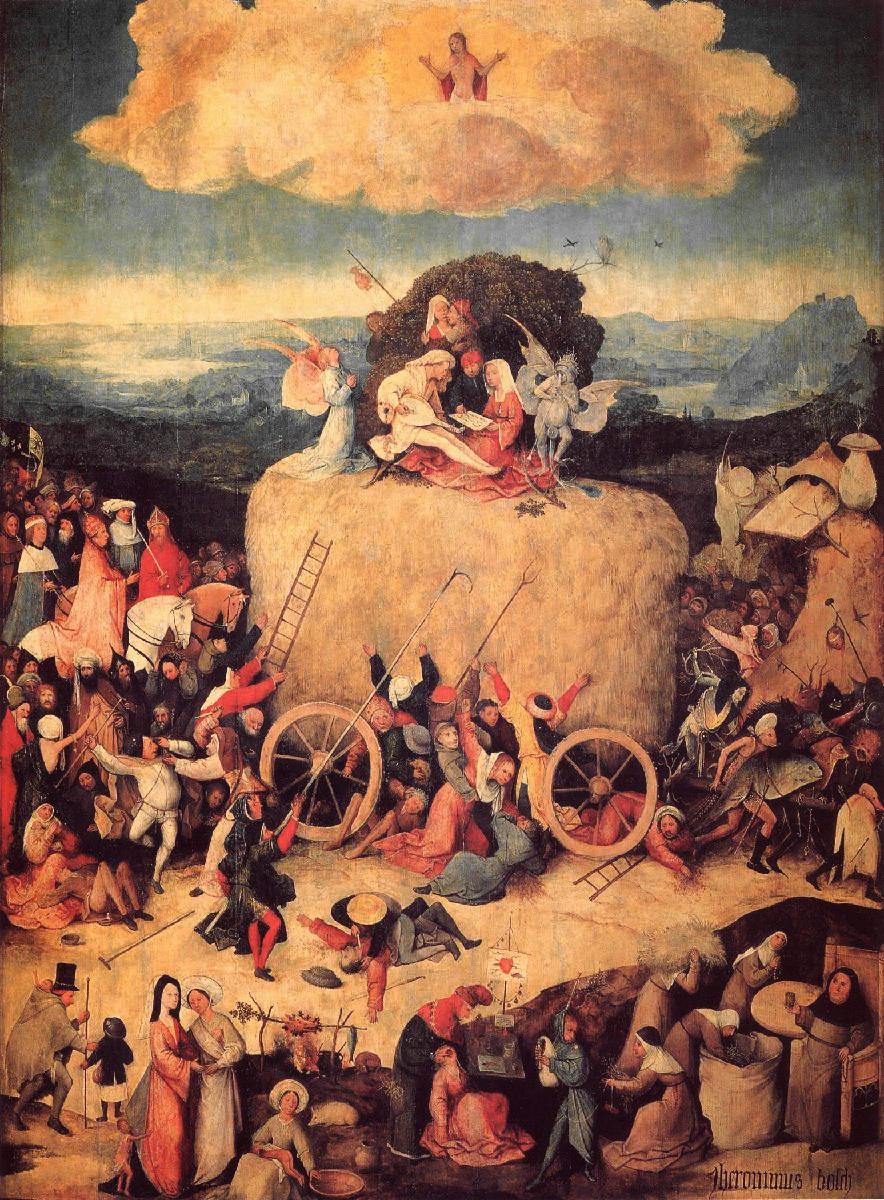

Hieronymus Bosch –

The

Haywain (1500-1502) central panel of a triptych; oil on panel

Madrid, Museo del

Prado

Musée du Louvre,

Paris

Albrecht Dürer (1471 - 1528)

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Alte Pinakothek - Munich

Galleria degli Uffizi - Florence

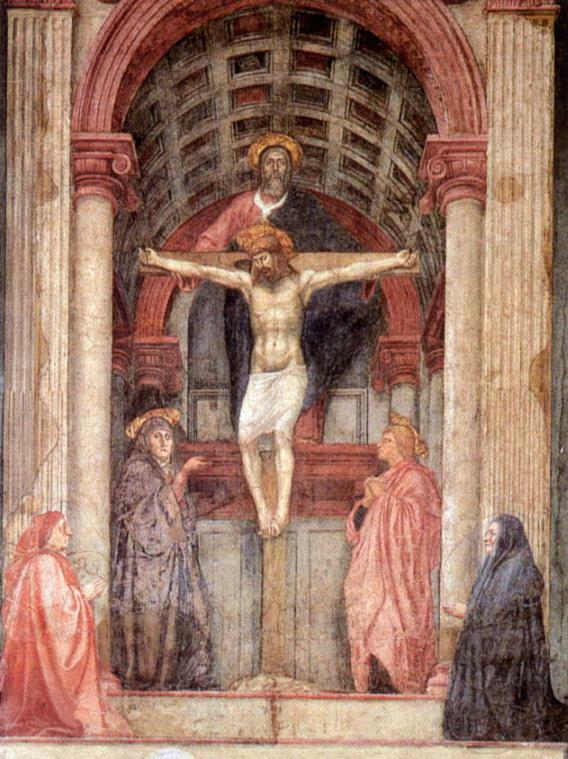

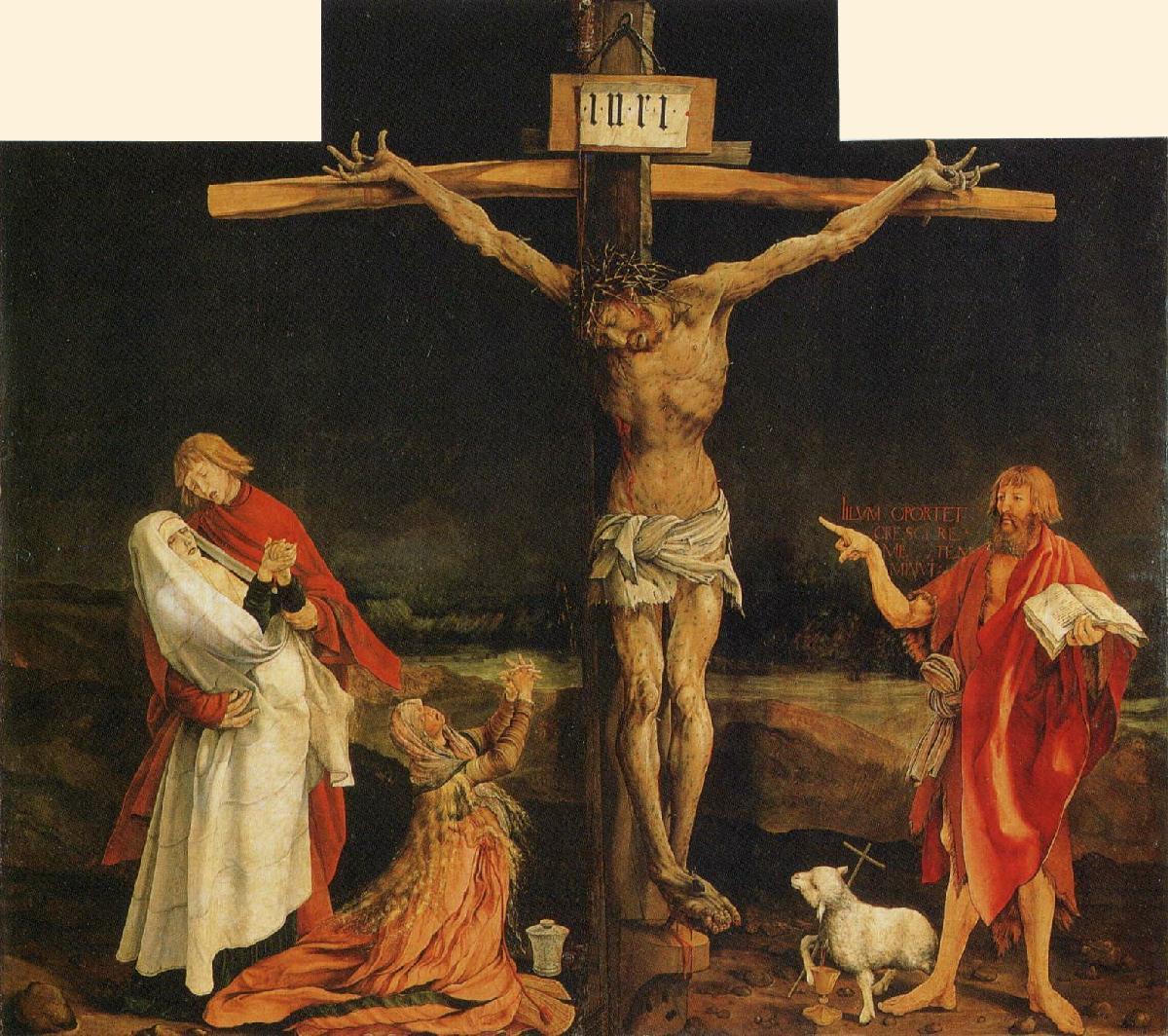

London, National Gallery Matthias Grünewald (c. 1475 - c.1528)

Monastery of the Antonites, Isenheim (Upper Rhine) oil on panel

Colmar, Museum Unter den Linden

| Holbein was a Swiss-based German famous for his masterful portraits of European nobility – most notably the person and court of Henry VIII of England. |

Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica - Rome

Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (1527-1528)

Holbein - The Ambassadors (1533)

National Gallery - London

For more of Holbein's work

For more of Holbein's workPieter Bruegel (1525?-1569)

But

of another style was the Flemish (Dutch) artist Bruegel. He took

Humanism to a new level … painting scenes of local village life … in

all kinds of seasons – involving all kinds of local activities.

Well-known today are such works of his as The Hunters in the Snow (1565) and The Peasant Wedding (1567) … all depicting simply local life. But

of another style was the Flemish (Dutch) artist Bruegel. He took

Humanism to a new level … painting scenes of local village life … in

all kinds of seasons – involving all kinds of local activities.

Well-known today are such works of his as The Hunters in the Snow (1565) and The Peasant Wedding (1567) … all depicting simply local life.

|

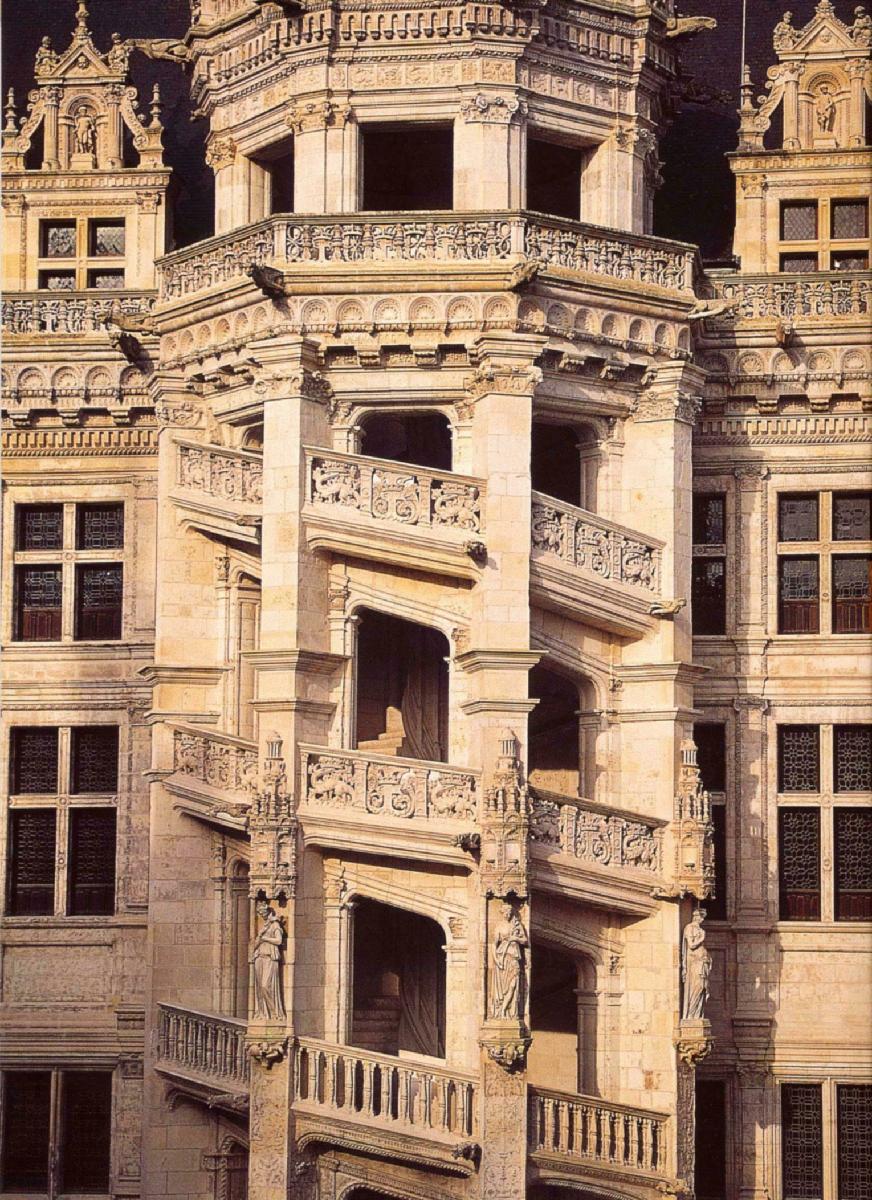

RENAISSANCE ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN EUROPE |

The Château de Fontainebleau - expanded greatly by François I in the 1520s and 1530

Château de Chambord from above!