|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

BC

c. 1000 Latins, Umbrians, Sabines, Samnites migrate into Italy

c. 900 Etruscans migrate into northern Italy ... and over the following centuries establish their dominance over other Italian societies

500s Etruscan power and culture (similar to the Greeks) under the Tarquins is at its height

The Tarquins build up the city of Rome ... governing through several comitia (councils)

509 Romans join with other Latins to overthrow Tarquin power in their region ... and establish their own Republic

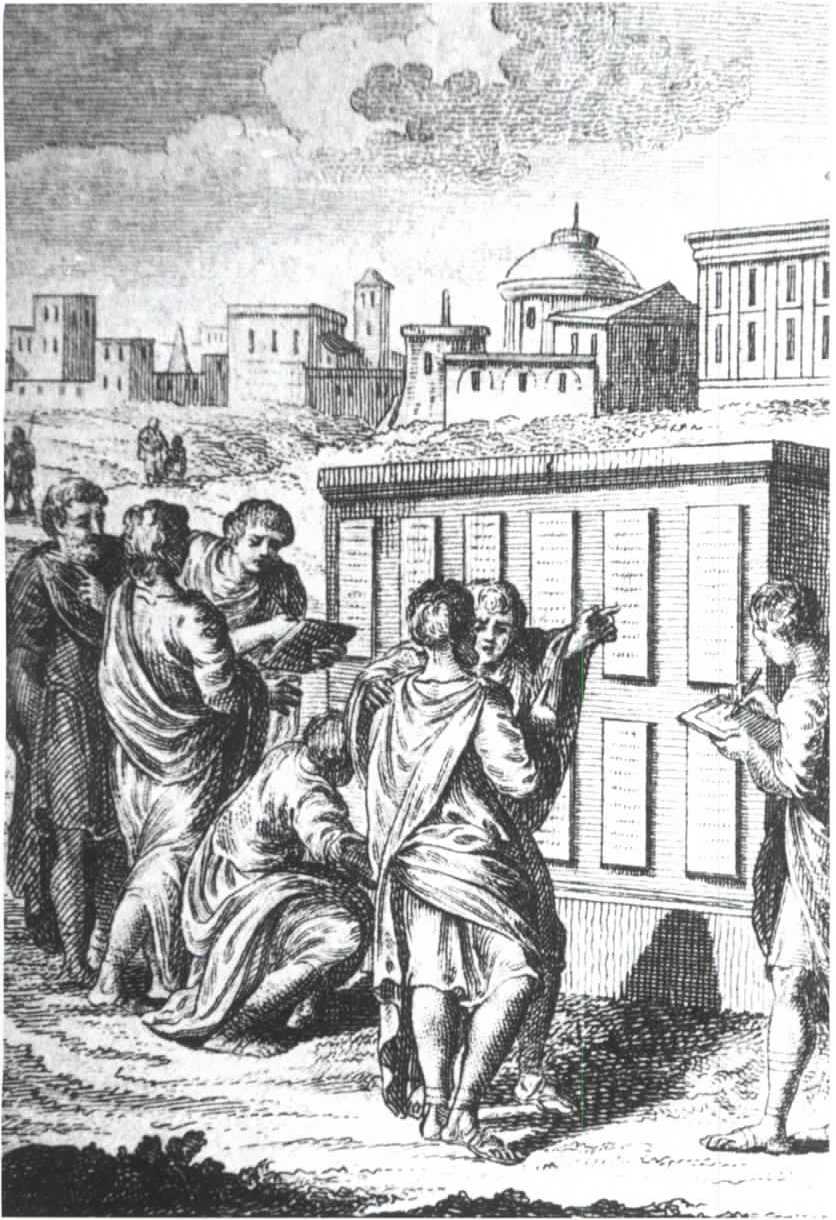

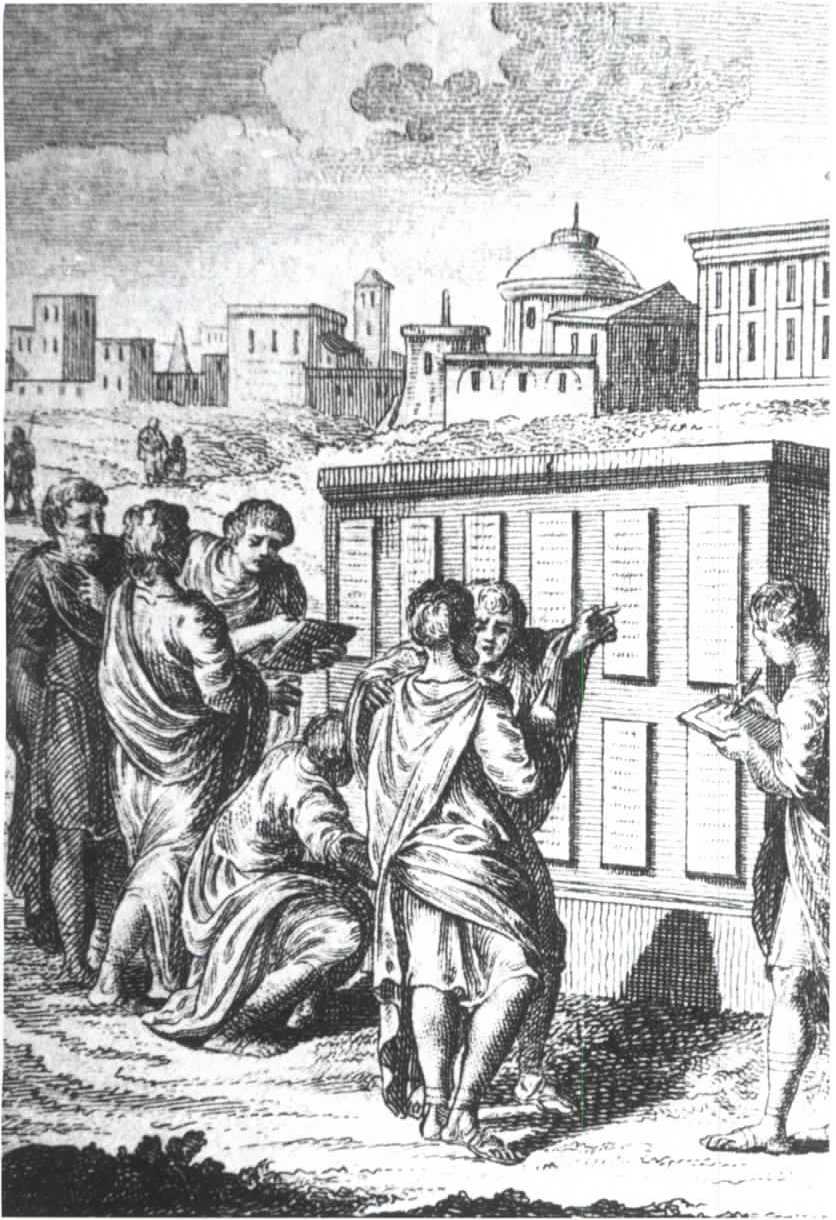

c. 450 Rome's extensive law code is displayed on 12 bronze tablets in the Roman Forum

400s Rome moves to dominance within the Latin League

396 Rome under Camillus (perhaps real, perhaps legendary), slaughters the Etruscans at Veii ... weakening deeply Etruscan power

390 Gauls invade from the north, destroying the Etruscans ... and nearly Rome as well

But Camillus (supposedly) is able to rally the Romans and then destroy

the Gauls ...

who retreat back north

338 Latin cities rise up against Roman domination ... but get crushed by the Romans

But the Romans wisely extend Roman citizenship to the inhabitants of

those cities

300 By this time, Rome has become deeply Hellenized (Greek) in culture

295 The Battle of Sentinum: Samnites also are finally brought under Roman control

275 The Battle of Beneventum: Greek King Pyrrhus of Epirus has been trying to force Roman Italy under his authority (280-275 BC), is defeated

also soon bringing Greek southern Italy (Magna Graecia) under Roman

authority

264 The beginning of the Punic Wars: Rome and Carthage (in north Africa) fight each other for control of the central Mediterranean

241 Carthage is defeated and expelled from Sicily, ending the First Punic War (264-241 BC)

220 Carthaginian general Hannibal invades Spain, crosses the Alps, and sets up Carthaginian power in northern Italy ... and overwhelms Roman power in many

subsequent battles

202 Roman general Scipio takes the offensive to Carthage itself, defeats Hannibal there, and breaks Carthage's power ... ending the Second Punic War (220-201 BC)

214 Rome organizes a Greek rebellion against Macedonian authority ... ultimately placing Greece, Macedonia and even Syria under Roman "protection"

187 Jealous Roman patricians, led by Cato (the Elder), falsely accuse Scipio and his brother of corruption; Scipio simply retires from public life

168 Greeks tire of Roman "protection" and revolt ... but are defeated at Pydna

149 A fast reviving Carthage inspires the Roman Senate to attack Carthage, destroy it, and make the region ("Africa") a Roman province, ending the Third Punic War

in 146 BC

148 Greeks at the same time rebel again against Roman authority ... but are finally (also 146 BC) brought by Rome under full Roman authority

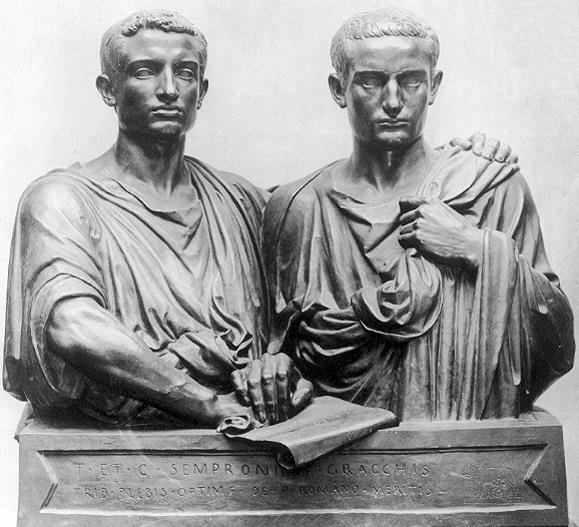

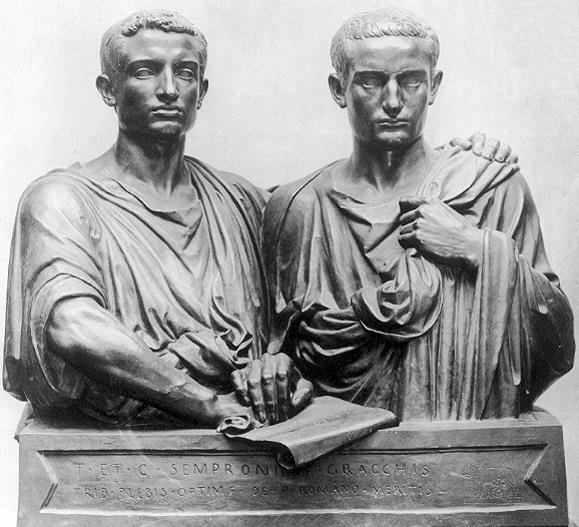

133 The Gracci brothers, Tiberius and Gaius (Tribunes 133-121 BC), attempt to reform the

Roman constitution (land reforms) in favor of the common people (the

plebians);

121 The aristocratic (patrician) Senate reacts against the brothers violently (both die)

108 Very successful (and popular) military leader Marius is Consul (108-100 BC), and uses his military authority to put in place numerous reforms of the Roman

political system

91 Plebian tribune Drusus is assassinated in his effort to extend citizenship to all Italians ... sparking and plebian revolt and the beginning of the

Social War (91-87 BC)

88 Sulla marches his men on Rome to settle down a dispute that erupted over the Senate's extending citizenship to all Italians ... toughening Rome's politicial

system

86 Marius returns (also at the head of a Roman army) as consul and puts his own reforms back in place ... but dies soon thereafter

82 Sulla returns with his army to Rome and replaces Marius's reforms with his own rules

73 Slaves, under the leadership of Spartacus, rise in rebellion against Rome, but are crushed by Crassus's army (71 BC) ... lining the Appian Way with 6,000

crucified slaves

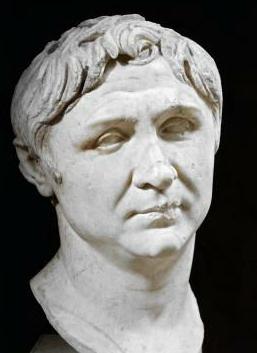

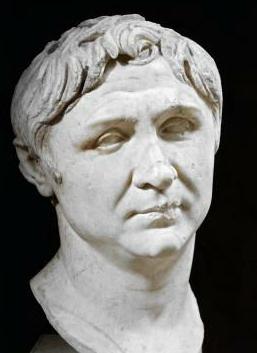

64 Roman general Pompey comes to fame in annexing Syria as part of the Roman empire

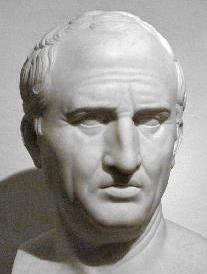

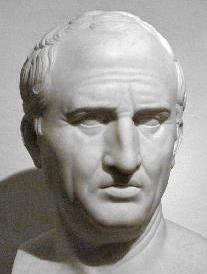

63 Cicero is elected Consul ... and attempts to move Rome back to traditional civilian (republican) rather than mililtary (imperial) government ... though he

will have little power to back up his efforts

60 Crassus, Pompey and Caesar form a Triumvirate (group three men) to direct Rome's affairs abroad

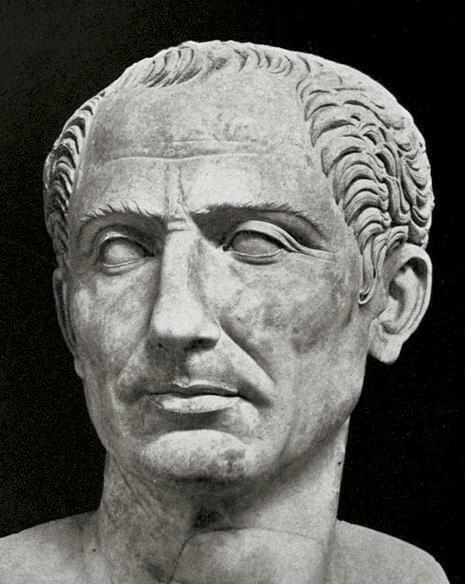

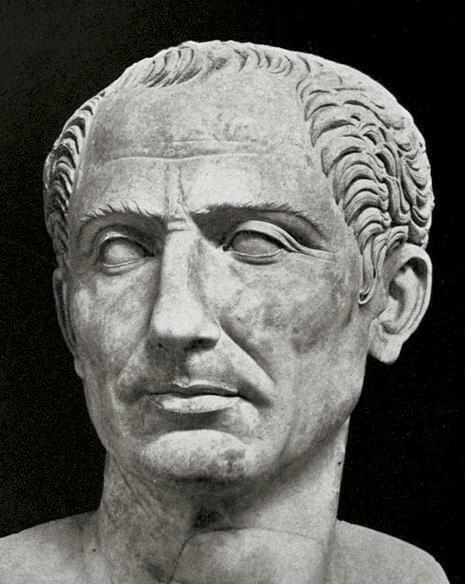

58 Julius Caesar comes to fame with his military victories in the Gallic Wars (58-50 BC)

53 Crassus is killed in battle with the Parthians (Persians);

52 With support of the Senate, Pompey takes control of Rome as sole Consul (52 BC)

49 Caesar learns that Pompey and the Senate are plotting to have him removed from all military command ... and marches his army on Rome ... scattering his

enemies.

Rome is now

totally under his military (imperial) control! The Republic is

dead.

AN OVERVIEW

OF REPUBLICAN ROMAN SOCIETY AND CULTURE |

The

Romans, coming along behind the Greeks (after defeating the Greeks

militarily in 146 BC and turning Greece into a Roman province), put

into effect a wonderfully ordered material civilization. This

civilization indeed gave witness to the power of human reason or human

engineering to work with the natural world in producing a place that

people often thought was perfection itself. Roman civilization

bore out the hope of the Greeks – by giving the West a practical

example of the orderly life.

The Romans were not intellectual innovators – as the Greeks were with

their powerful philosophies. Rather, the Romans were powerful

administrators – such as the Greeks themselves were never able to

be. The Romans, with their sense of legal or administrative

order, put the Greek ideas to work in life. Probably had not the

Romans done so, the Greek contribution might itself have been put aside

with its own growing cynicism and skepticism. Thus the Romans

contributed immensely to (materialistic) Western civilization by

demonstrating clearly that orderly cooperation with nature could

produce amazing results.

The ongoing influence of Hellenistic thought

Yet even under the practical-minded Romans, Western philosophy

continued to develop. But Roman philosophy tended to follow the

lines laid down by Hellenistic Greece in the two previous

centuries. Indeed, as once Eastern thought captured its Greek

conquerors centuries before, now Greek thought began to capture its

Roman conquerors. Thus did Greek Platonism and Stoicism continue

to draw Western philosophy forward, though now under Roman

patronage. Indeed despite Roman political ascendancy, the

Greek-speaking eastern provinces of the Roman Empire continued by their

own right to be vibrant and at times even dominant

cultural-intellectual centers within the Roman Imperium.

Indeed, once the Romans conquered the Greeks and turned Greece

into a Roman province, actually things Greek rapidly became the

standard for "higher" or "more civilized" ways of thinking and behaving

just in general.1

A Roman's ability to read, write and speak Greek fluently was

considered a necessary sign of higher social standing. Thus

schooling for Roman youth included lessons in Greek at a very early age

– and almost always instruction in Greek by Greek professors at the

higher levels of Roman education.

Thus it was that Roman art, literature, drama, philosophy, and even

religion were strongly shaped by Greek tastes and

interpretations. There were unique Roman contributions to each of

these intellectual forms of course. But at the foundations, the

Greek character of Roman culture was unmistakable. Indeed,

despite Roman political ascendancy, the Greek-speaking eastern

provinces of the Roman Empire continued by their own right to be

vibrant and at times even dominant cultural-intellectual centers within

the Roman Imperium.

The Roman concept of the "legal order"

Where things Roman differed from things Greek was mostly in the area of

politics and social organization. The Greeks (in particular the

all-dominant Athenians) seemed to see politics more in terms of the

general will of society – wherever that might take things … greatly

directed of course by clever manipulators of public opinion, such as

the Sophist-trained orators who specialized in the art of "demagoguery"

or manipulation of the public will. The Romans thought of

politics more in terms of what the legal order permitted or required of

those who would practice politics. In this area the Romans

strangely enough proved to be more abstract than their Greek

counterparts.

The Romans were greatly enamored with the idea of "order" in almost

everything they designed or developed. The Romans had a very well

organized law code which allowed them to rise above the tribal

mentality (all members of society related by blood and members of a

single genealogical line) and instead create a monumental society built

on a mutual respect for a politically neutral Code of Law ... one that

made all who came under its authority coequal partners in the Roman

social experiment.

In Roman eyes the Law – not the public will – dictated what was

supposed to be done ... and how it was to be done. Thus lawyers

rather than orators tended to dominate the Roman political scene – at

least during the Republican era. And thus also it was the Romans

who came up with the concept of the "state," a powerful but impersonal

institution that granted authority to various assemblies and officers

acting on behalf of this state – termed a "Republic"2 – in fulfilling the duties of their "office" as defined by the Roman legal system.

Thus Roman Law, though abstract in its design, was highly effective in

bringing a wide variety of peoples into a vibrant state of political

unity. In this area the Romans strangely enough proved to be more

abstract than their Greek counterparts.

Indeed, in this realm of social development, Rome left a legacy in the

West that exists to this day: the understanding that society ought to

be a community of laws, not of personalities or special social groups.

Of course that is a very high standard to which to aspire ... or to

maintain if achieved. Ultimately Rome itself could not maintain

such a lofty concept ... and declined as it left that standard behind

it. But the legacy remained and still serves to this day as a

major political ideal among Western societies ... whether actually

achieved or not.

Thus it is that we tend to idealize the Republic – probably a bit

caught up too much in the idealized vision of the Republic put forth

(and still read today) by Cicero, who wrote even as he saw his beloved

Republic coming to an end. Actually for most of its days the

Republic was run by a privileged elite, drawn from the very old

aristocratic patricians and from upstart plebeians who were able to

attain incredible wealth (usually at the expense of the other

commoners) and status through intermarriage with the patricians and

through acquiring a place in the Senate, which they guarded

jealously. There were Tribunes, selected for short terms (one

year) to watch out for the interests of the commoners, plus the

Assembly, which was supposed to give voice to commoners'

interests. But by and large during the Republic, the Senate did

what it could to keep a tight hold on the political life of the

Republic.

Rome's Cultural-Religious Pluralism

Another reason for its grand success was that Rome proved to be quite

tolerant of the social and cultural "pluralism" within its borders – as

long as everyone showed due respect to Roman authorities and their

gods. When the authorities themselves posed as gods this all

became quite curious. But for the most part everyone was willing

to play along with the Roman thing. Morally and ethically, Rome

didn't reach deeply into the private hearts of its subjects. That

belonged to their local gods and religious traditions.

The Roman Economic Order

The Romans also organized the world around them physically and

materially as they conquered it, building roads (still standing today

in many places) to provide rapid communication, troop movement and

ultimately commerce connecting the Roman center to its outlying

territories. Wherever they conquered, they planted military camps

on a perfectly uniform grid pattern ... which became the heart of new

commercial towns which quickly grew up around these garrisons.

They cleared the seas of pirates and kept marauding tribal raiders from

central and east Europe closed out beyond a well-defended line running

from the Rhine River in Germany to the Danube in the Balkan Peninsula.

Consequently, under Roman rule Europe, North Africa and the Eastern

Mediterranean area experienced an unprecedented peace and prosperity

that made "Rome" the very model of civilization itself to millions of

people.

However, ancient Rome went through a number of deaths – and a number of

reincarnations, springing back to life as a society reinvented into

some new form, always "Rome" but never the Rome it once was.

Maybe such change was a good thing. Maybe it was not. But

in any case, those who loved the Rome they were born to would suffer

tremendously from the loss or death of the Rome familiar to them.

The Roman Military

In the very early days of the Republic the army was basically a citizen

militia, whose soldiers, like the Greek hoplite army, supplied

their own armor and weapons and who trained and fought in tightly

packed formations (similar to the Greek phalanx) hurled at similar

enemy formations. With time this heavy but cumbersome structure

was broken up into a more flexible system of forming smaller and more

mobile units called maniples of approximately 100 men each. 30

maniples, supported by protecting cavalry and more lightly armed but

very maneuverable light infantry, formed a legion (typically 4,000 to

5,000 men).

Overall, such formation gave the Roman military tremendous advantages

in the conduct of battle … a major reason for Rome's incredible

political expansion across the Mediterranean world.

In those earlier years of Rome, its soldiers originally were simply

farmer-soldiers, propertied and thus with a personal vested interest in

the outcome of battle. But as time went on, with the increased

use of soldiers for political as well as frontier service, the ranks

thinned out from the huge number of casualties – and proletarii

(landless, usually urban, citizens) were recruited and salaried for

their service. Also foreign troops (often tribal cavalry units)

were recruited – for pay. By the end of the Republic, Roman

soldiers were more or less paid professional soldiers – motivated less

by a sense of civic duty than an affection for their commander who

rewarded or supported them with pay and whose own political fortunes

were what seemed most to motivate his legions. This shift in the

nature and purpose of the Roman legions was probably the single most

important factor in the death of the Republic and its replacement by

the Empire.

1This

however was also due in part to the earlier Etruscan influence, for the

Etruscans themselves modeled much of their cultural ways after the

Greeks.

2The word republic is derived from

Rome's Latin language, much as the word democracy is drawn from the

Greek language. In the Latin, republic is written as res publica,

meaning "thing of the people," that is, a government created by Roman

law belonging to no particular social group, no dynasty, but to all the

people.

THE

ORIGINS OF THE ROMANS |

|

The first

Italians

Three

groups of Italian-speaking tribes – the Latins, the Umbrians and the

Samnites – migrated down into Italy from the north just about the same

time that the Dorians were overrunning Greece (around 1000 BC).

They too conquered with iron weapons, thus introducing the iron age to

Italy. They eventually settled into the mountainous center of the

Italian peninsula and in the west-central lowlands facing the

Mediterranean Sea. Basically, these peoples were farmers, cattle

raisers and sheep herders.

This

wave of conquest and settlement was followed in around 900 BC by

another – that of the Etruscans, who invaded central Italy from the

east. The Etruscans established ascendancy over the Italians, and

reached the peak of their power during the mid-500s BC. They

established cities and a high order of a material civilization – quite

like the Greeks … who seemed to have influenced deeply Etruscan culture

over the centuries.

Greek Italy

We

have already seen that the southern part of Italy, including Sicily,

was settled heavily by the Greeks as Magna Graecia. Here Greek

civilization attained great heights of achievement. It certainly,

along with the Etruscan culture, left a strong material legacy among

the Italians – though the latter held tenaciously to their distinct

Italian language.

The

actual origins of Rome itself are submerged beneath a heavy overlay of

patriotic myth – and thus it is hard to get at the "facts." The

town was created through the joining of a number of settlements found

among the "seven hills" located along the middle Tiber River.

These eventually came to comprise early Rome.

Myth

says that two Latin brothers, Romulus and Remus, were responsible for

laying out the foundations of Rome on the Palatine Hill in 753

BC. But an Etruscan royal line (the Tarquins) seems to have

established itself in Rome by the 500s BC. The Tarquin monarchy

ruled the town and environs – though it was by and large a positive

rule, building up Rome with an extensive city wall, public buildings

and public water and drainage works and bringing commercial prosperity

to Rome. It also developed a very effective military force.

The Etruscans also gave Rome its first experience in representative

government, laying out Rome's basic governmental framework of several

councils (comitia and their

leaders or consuls) to oversee Rome's various civil and military

functions. It was at this time that a body of local "first

citizens" or Roman patricians grew in prestige and influence within

Rome itself.

4The

origins or ethnic background of the Etruscans remains a grand mystery

to historians. They apparently spoke a non-Indo-European language

unrelated to the Greek, Roman, Celtic languages of the region ...

perhaps having roots in the region even prior to the arrival of these

Indo-Europeans.

Etruscan warrior or Mars

(mid 400s BC) bronze

Florence, Museo

Archeologico

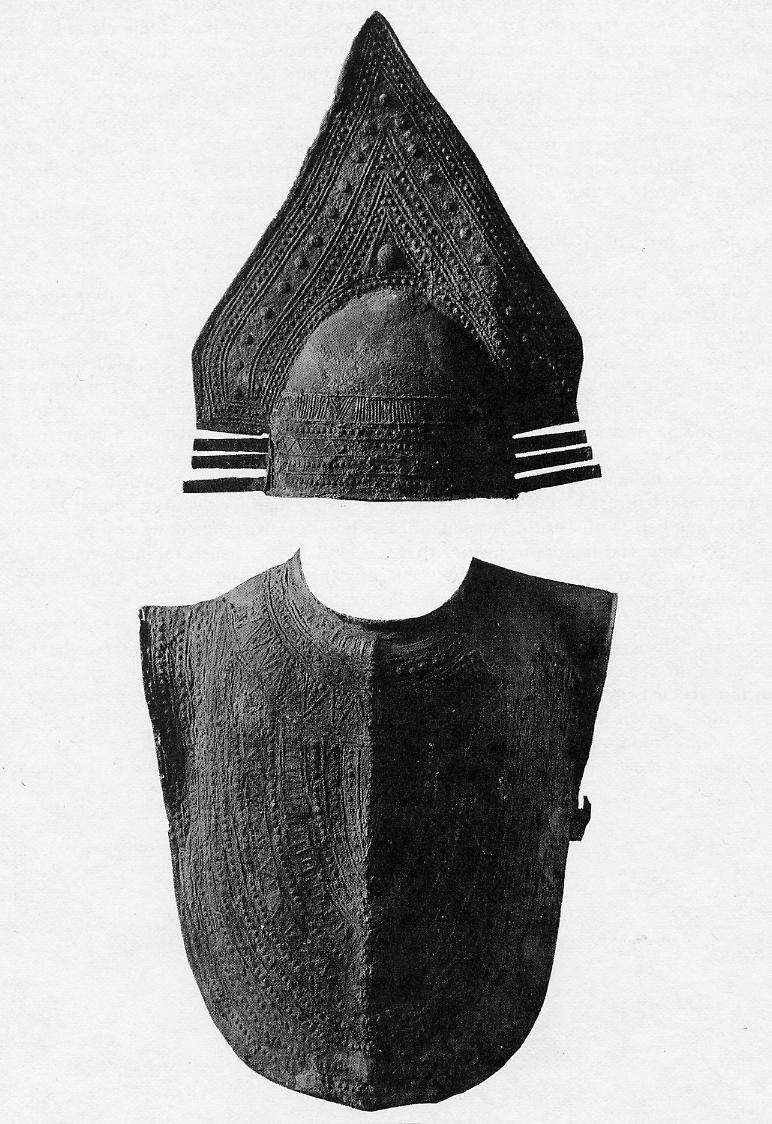

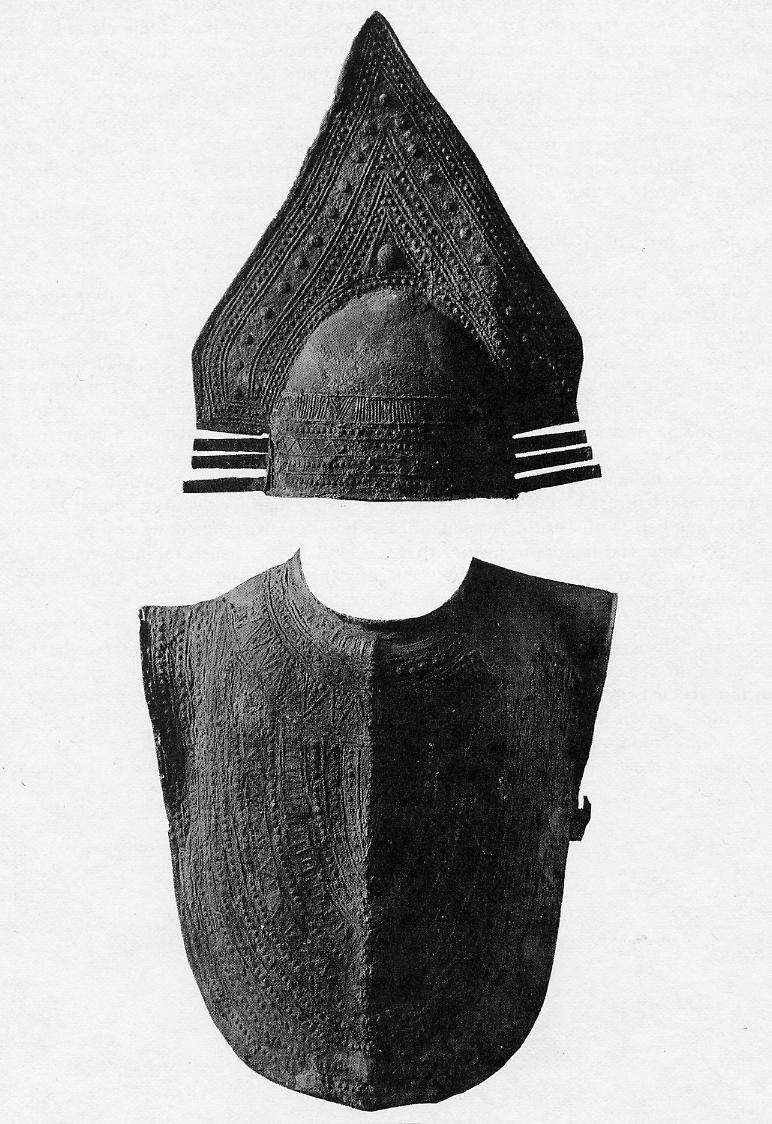

Villanovan (Etruscan) helmet

and body armor Villanovan (Etruscan) helmet

and body armor

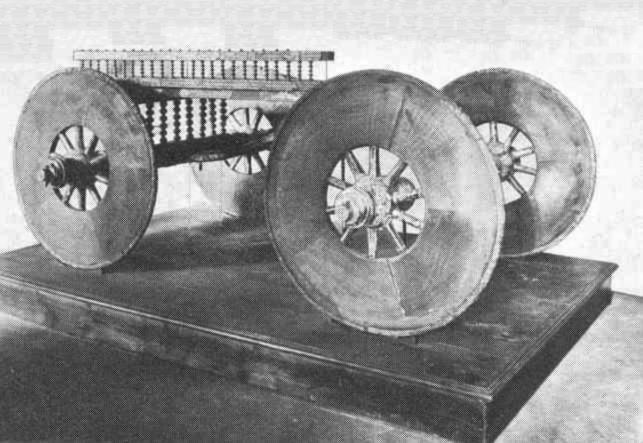

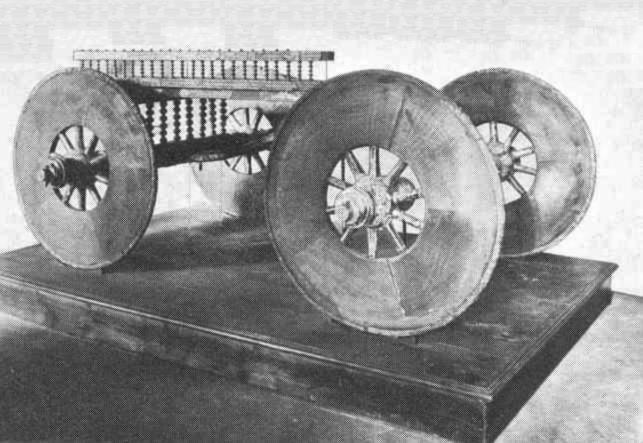

Etruscan horse-drawn

chariot

Museo Civico di

Como

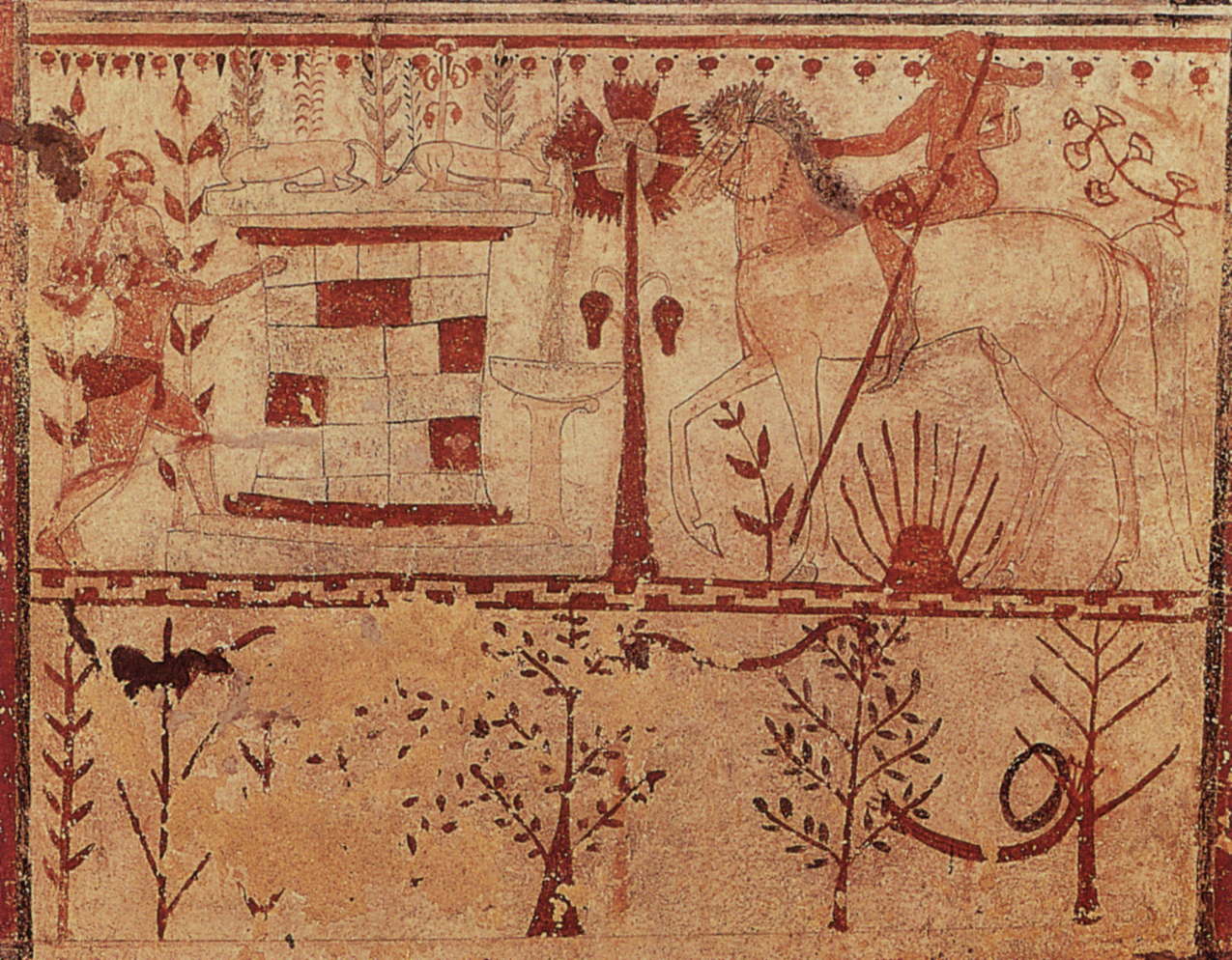

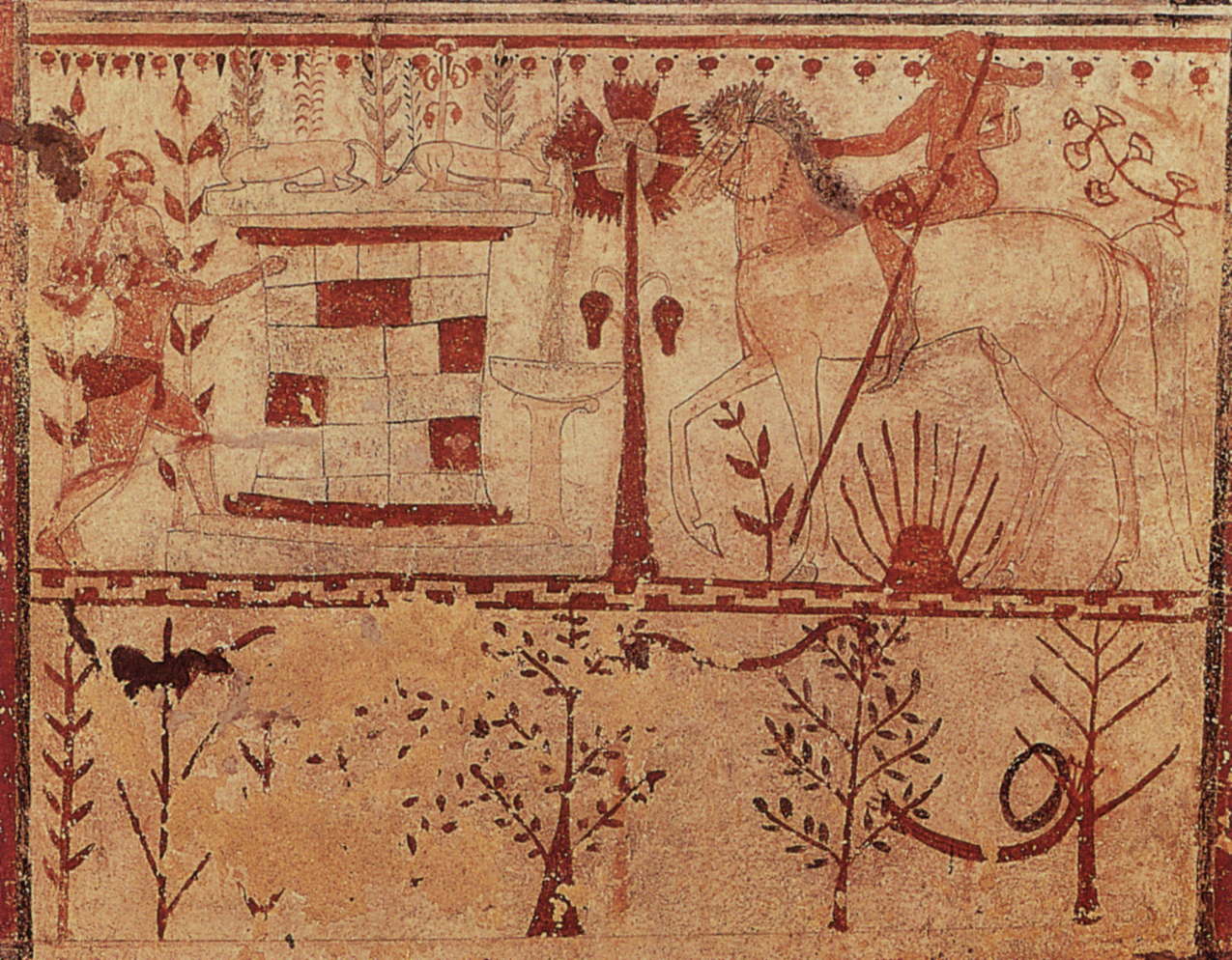

Ambush of Prince Troilus

by Achilles — Detail of painted wall

Etruscan Tomb of the Bulls,

Tarquina (540-530 BC)

Etruscan Sarcophagus of

the Spouses (late 500s BC) polychrome terra cotta – from

Cerveteri

Paris, Musée du

Louvre

Two Etruscan

Warriors

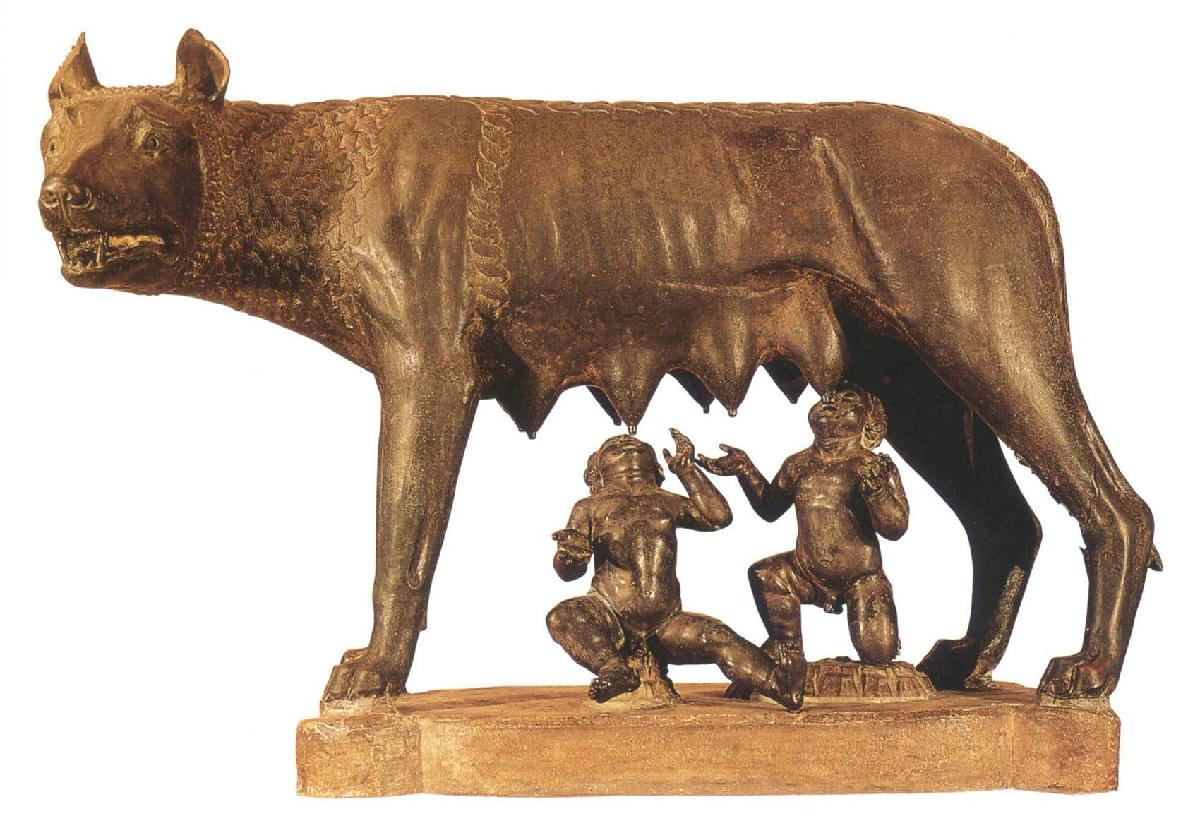

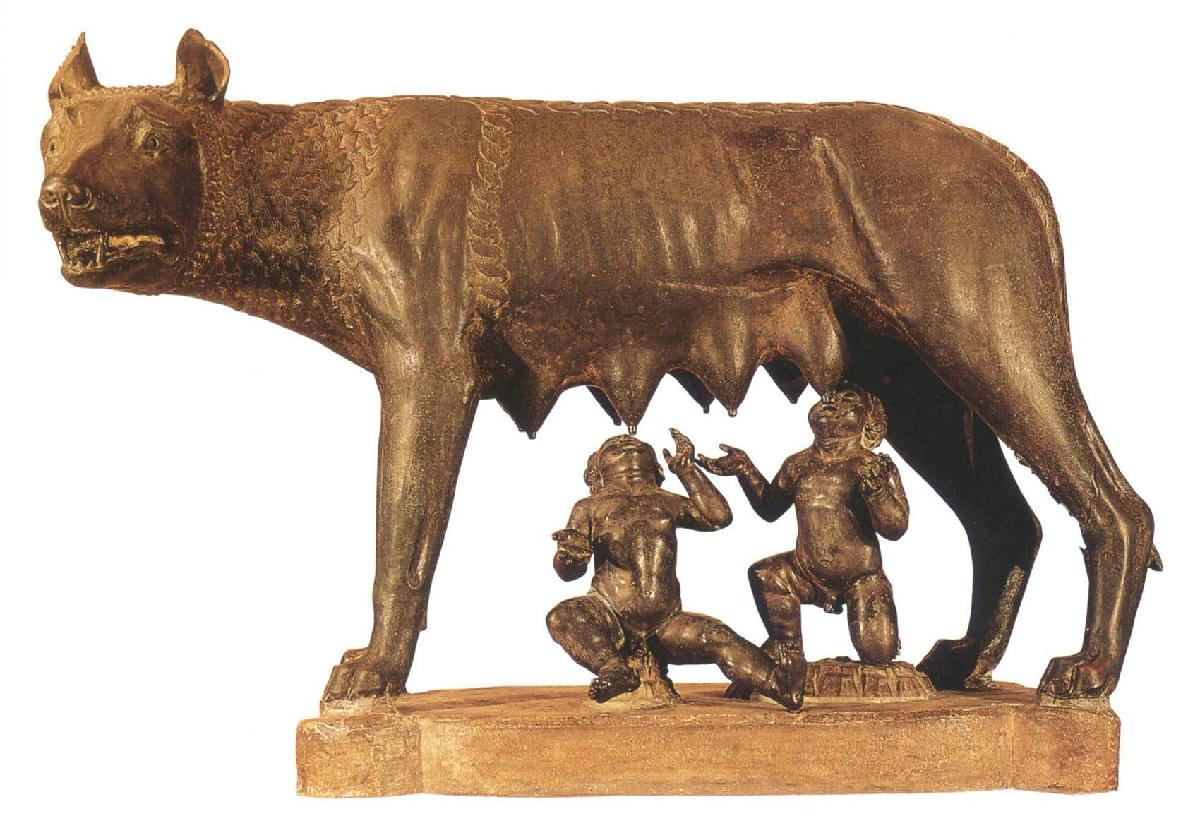

The

"Capitoline" she-wolf

(early 400s BC and possibly Etruscan) bronze

(the twins, Romulus and Remus,

probably date from the

late 1400s)

Rome, Palazzo dei

Conservatori

THE

EXPANSION OF REPUBLICAN ROME |

|

Early rise among the

Latins

In

the late 500s BC Rome began its expansion by entering into alliance

with other Latin cities against Etruscan dominance. In 509 BC

they expelled the Etruscan King Tarquin ... and established their own

Republic.

But

gradually over the next century and a half, Roman leadership within the

alliance turned to dominance within the alliance (much as Athens was

doing at about the same time).

With

this growing power, Rome put increasing pressure on the Etruscans. In

396 BC, during an ongoing conflict with the nearby (and quite wealthy

and powerful) Etruscan city of Veii, the Romans awarded the temporary

position of dictator to Furius Camillus, who led the Romans finally to

success in the conflict ... slaughtering the entire male population of

Veii and enslaving its women. Henceforth the Etruscans would

remain troublesome – but no longer a major threat – to Roman designs in

Italy.

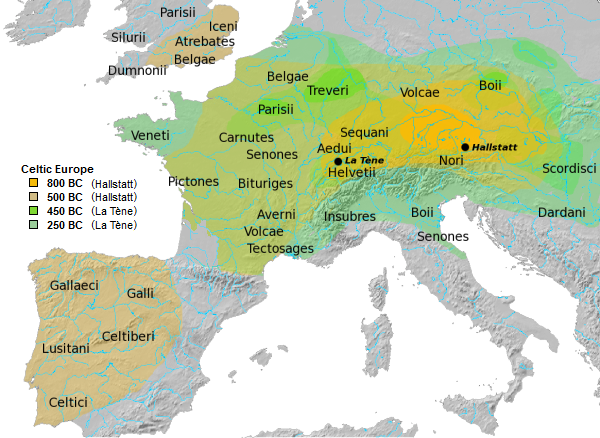

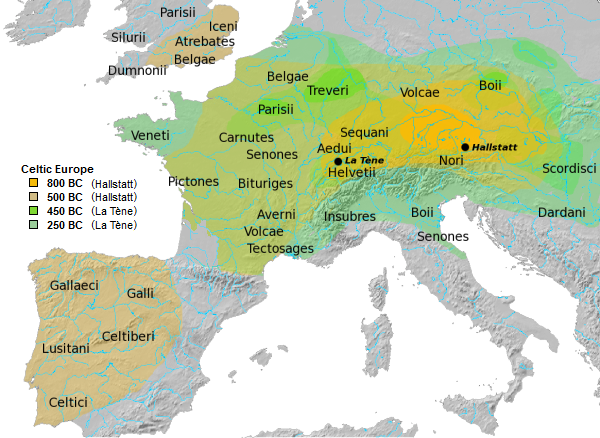

Against the Celts

But

just as the Romans were beginning to enjoy the fruits of victory, Celts

or Gauls invaded from the north and not only crushed the Etruscans,

they sacked Rome itself (but failed to capture its citadel) in 390

BC. Once again the Romans called on Camillus (who had been

banished by jealous rivals) ... and at the head of a 12,000 man army he

and his army slaughtered the Gauls – who had fallen into a drunken

stupor after pillaging Rome. Then – largely to restore unity

within a socially divided Rome (plebeians or commoners against the

patrician class) – Camillus turned his troops on neighboring cities in

the region.

After

that, as quickly as they had come, the Celts also retreated from

Rome. Soon the Celts settled back into northern Italy, leaving

Rome to recover quickly.

Etruscan collapse

But

the Etruscans were quite thoroughly devastated by the Celts. The

Etruscans soon lost power as a vibrant society – and mysteriously their

culture disappeared. They left us with no knowledge of their

language and very little of their history.

Roman expansion

This began the process of the extensive development of Rome’s citizen

army ... and the aggressive policy by which Rome approached the rest of

Italy. This in turn sparked bloody wars with Rome’s neighbors –

which Rome crushed one by one.

Absorption of the Fellow Latins and the Samnites

In 338 BC a number of Latin cities rose up in revolt against Roman

dominance. But the Romans responded swiftly both militarily in

crushing the Latin uprising and diplomatically in extending Roman

citizenship to the conquered Latins.

Also, the fellow Italian Samnites in the mountain valleys of central

Italy tried to block Roman expansion through a series of wars or

uprisings beginning in 343 BC – though they too (along with some

Umbrian, Etruscan and Celtic/Gallic allies) finally fell to Roman power

at Sentinum in 295 BC.

Relations with the Greeks in Southern

Italy

For

a while the Greeks and the Romans were cooperative, with the Romans in

fact adopting many Greek cultural features – many of them transmitted

earlier to the Romans by the Etruscans during the monarchy.

Notably there was the Roman adoption (with many modifications) of the

Greek alphabet. Indeed, by 300 BC the process of Hellenizing

Roman culture was moving rapidly forward – especially through the

romanticizing of Alexander and his exploits, which led the Romans to

idealize Greek power, Greek culture, Greek philosophy, Greek religion.

But

Roman political expansion and the question of which of the two powers

was to dominate southern Italy was destined to produce friction with

the Greeks in Italy. A Greek reaction – joined by some Latin allies

also resenting Roman dominance – finally took form around the ambitions

of King Pyrrhus of Epirus, who (equipped with some awesome elephants)

managed at first to defeat the Romans in several battles. But

these victories were so costly to Pyrrhus ("Pyrrhic victories") that it

depleted Greek power and discouraged their Latin allies – to a point

where the Romans were finally able to defeat Pyrrhus in 275 BC at

Beneventum. Quickly thereafter Roman mastery of southern Italy

became complete. But there was still a mighty Greek presence in eastern

Sicily in the form of prosperous Syracuse.

Against

Carthage

Carthage5

was a great sea power located on the North African coast just across

from Sicily, as well as in western portions of Sicily itself. At

first competition for the Carthaginians came from the Greeks (during a

century-long war from 367; the Romans were fairly friendly to the

Carthaginians). But after the defeat of the Greeks by the Romans,

the Romans and Carthaginians were left facing each other for ultimate

dominion over the seas around southern Italy and the lands around the

western Mediterranean that began to interest the Romans.

The

clashes came in the form of a series of wars – the Punic Wars – fought

between Rome and Carthage over the next 120 years (264-146

BC). Carthage was a formidable opponent, with a powerful

navy and a huge, prosperous urban population to put muscle to their war

effort. But Rome had an experienced, battle-tested land army.

The First Punic War (264-241 BC) linked Hieron II of Syracuse with the Romans in expelling the Carthaginians from Sicily.

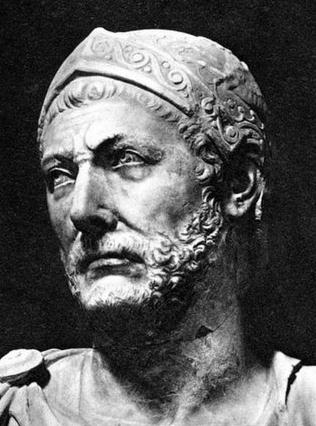

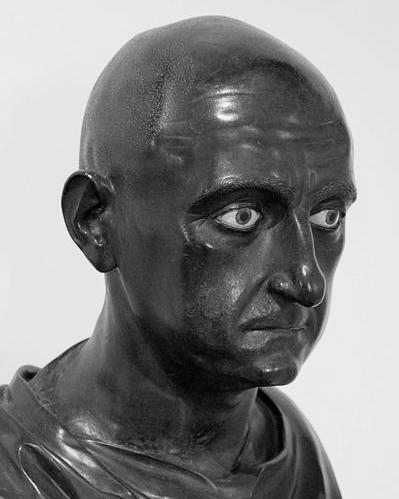

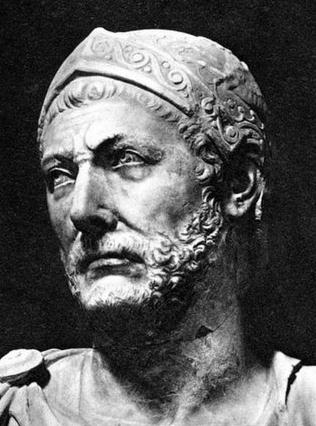

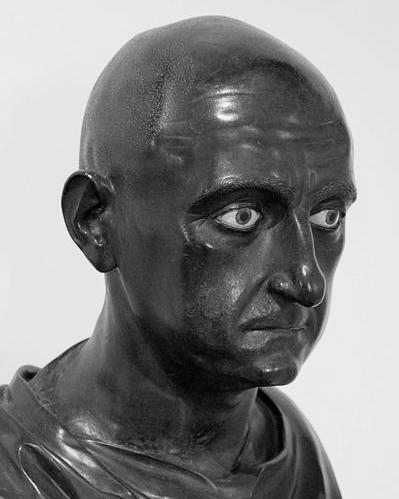

The Second Punic War (220-201)

started when the Carthaginian leader Hannibal Barca attacked Roman

Saguntum in Spain, then crossed the Alps with a mighty army and

for 15 years held off Roman efforts to dislodge him from northern Italy

– until Rome decided to take the war to Carthage itself, where at Zama

(202 BC) Hannibal lost his only battle (but also the war) to the Roman

general Scipio "Africanus" (considered still today as one of the best

generals in history). Carthage was stripped of its war-making

powers as a result of the war. Tragically, the Roman patricians

(upper-class) were jealous of the popular Scipio and brought him to

trial for unfounded charges of bribery and treason, resulting in his

retreat in disgust from Roman public life.

Carthaginian

General Hannibal Barca / Roman General Scipio Africanus

The Third Punic War (149-146)

occurred when the leading families in the Roman Senate decided that it

wanted no further competition from a fast-reviving Carthage, found an

incident that permitted them to return to war, eventually marched on

the city, and after a 3-year siege, burned it to the ground.

Carthage was destroyed and Africa (the region around Carthage) became a

Roman province.

Against the Greeks

Philip

V of Macedonia unfortunately had chosen to ally himself with Hannibal

during the Second Punic War and Rome. Once Hannibal had been

defeated, The Romans turned their attention to Philip and led a

rebellion of Greek states against the Macedonian monarchy in 214

BC. This drew Rome deeply into Greek affairs and a number of wars

involving Rome in Greece – and also in Macedonian Asia Minor and Syria

under Antiochus. Rome "liberated" these Greek cities and

placed them under Roman protection – as Macedonian power was chipped

away.

But

eventually Roman dominance bred its own opposition in the Greek

East. Perseus of Macedonia tried to rally these Greek sentiments

– but the Romans quickly marched out to defeat him at Pydna (168

BC). The Romans did not follow up their victory in such a way to

discourage further thoughts of rebellion ... until 148 when a final war

with the Greeks and Macedonians (148-146 BC) brought Macedonia under

full Roman dominion as a Roman province and the rest of Greece under

the full "protection" of the Roman governor in Macedonia.

In

Asia Minor and Syria the Romans continued the pretense of a mere

"protection" placed over local Greek power – but made and unmade kings

and rulers at will. Roman rule was in fact complete in these

regions.

5Carthage

was itself a colony established in today's Tunisia by the

Semitic-speaking Phoenicians of the Eastern Mediterranean coast

(largely today's Lebanon) in the 9th century BC.

EARLY

ROMAN POLITICAL ORGANIZATION |

|

The Monarchy and the Comitia

The Tarquinian monarchy in Rome shared its power with several

assemblies or comitia whose power increased/decreased over the

centuries: the Comitia Curiata or popular assembly of all

freemen, the Comitia Centuriata or military assembly, and the Comitia

Tributa or tribal assembly (presided over by 10 Tribunes). There

was also the Senate, a council of elders serving for life as advisors

to the king – a council which grew in power and eventually took the

lead in the political life in Rome after the overthrow of the monarchy

(traditionally in 509 BC).

The Patricians and the Plebeians

There were among some of these early Romans a number of families of

"worthier" nature – the patrician families – marriage into which

offered a preferential placement in the Roman scheme of

things. The powerful Senate of course was dominated by

these patrician families.

Yet simple membership in any of the families of the permanently settled

Romans – the common citizens or "plebeians" – accorded itself some

important rights in the life of the Roman community. Indeed,

there was a most unusual openness about Roman life, its readiness to

adopt others into its communal life – even freed slaves. In fact

a freed slave living in Rome automatically became a Roman citizen.

The Republic

According to tradition, the Tarquinian monarchy was overthrown in 509

BC. The patricians were behind this action and it represented the

victory of the traditional Latin agrarian gentry over the newer

commercial groups closely connected to the Etruscans and Greeks through

trade. It marks a time of decline of Etruscan power – and the

growth of Roman military expansion.

With the new Republic, two patrician Consuls (serving one-year terms)

replaced the king as the head of the Senate and the military

Centuriata. But eventually (through plebeian pressures) a number

of Tribunes, representing the interests of the plebes, were accorded

both the power to protect the poorer Romans and certain veto powers

over the acts of the aristocratic Republic

.

There were a number of other Roman officials, the Quaestors (judges),

the Censors (tax officials), Aediles (public works supervisors) and

others whose powers, along with the whole governmental structure,

were carefully defined in the 12 tablets of the Roman constitution (ca.

450 BC) – posted in the Forum for all to see. All Romans knew

these laws well.

|

The 12 Tablets of the Law

|

The Dominance of the Roman Senate

This rise from an expansive agrarian power in west-central Italy to the

point where Rome now commanded the fabulous civilizations that ranged

around the Mediterranean (Macedonian Egypt, however, had not yet fallen

to Roman rule) – all this change was bound to have a profound effect on

the internal disposition of Rome.

Over time, but particularly during the wars with the Carthaginians, the

Roman Senate had become the center of all Roman power. It was a

club of old patrician families and new plebeian wealth (new landowners)

which closed its ranks and became a ruling oligarchy. Meanwhile

rising taxes and competition from slave labor were bringing the Roman

commoners to ruin. Roman power, especially the power of the Roman

military, was built on the services of these commoners. Something

drastic needed to be done to save Rome from collapse or revolution.

The Efforts to "Reform" the Roman Constitution

For three centuries the unchanging character of the Roman Constitution,

fixed on those Twelve Tablets, had served Rome well in keeping

political ambitions under fair control. But political ambition is

very difficult to manage … and for Rome the difficulty merely increased

with the increase in power of Rome itself.

Much of the social-political trouble was between the patricians or the

"equestrian" class dominating the Senate and controlling the wealth of

the countryside and the populare or common citizens demanding greater

influence in the life of the Republic. This conflict was greatly

complicated by the demands of the Italian allies for full Roman

citizenship (entry to which had been tightened up since it had become

so much more profitable since the Punic Wars).

Tragically for Rome, well-intended reformers finally stepped forward

with proposals to bring economic and political reform to Rome.

But what they did not realize was that such reform would merely open

the door wider to political contests … as "reforms" in favor of one

political group soon led to "counter-reforms" of an opposing political

group. Thus the rigidity of the 12-tableted Constitution now

became more "flexible" … that is, subject to political intrigue.

As a consequence, Rome's firm foundation on Law rather than Human Will

began to shatter … and the Constitution became no longer

"constitutional."

Roman Law would now read according to the interests of one group or

another that had managed to take control of Rome's political

dynamic. And tragically Rome's legal standards now became simply

the matter of the political interest of this group or that.

Rome's Republic was in trouble … deep trouble ... and sadly had no idea

of what could be done about mounting political animosities that only

worsened once the process of "reform" got underway.6

The Gracchi brothers (133-121 BC)

Two brothers, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchi, elected successively as

Tribune, tried to act on behalf of the plebeians to bring economic and

political reform to Rome. Essentially, they proposed the increase

of common lands for the use by the small farmers, the allotment of

newly acquired lands to retired soldiers, and the broadening of the

powers of and the electorate for the Assembly.

But

the brothers' reforms were blocked by the Senate. When riots

resulted, martial law was declared by the Senate and Tiberius was

murdered in the confusion. Gaius, who took his brother's place at

the head of the plebeian party, had Senate partisans sent after him and

he committed suicide rather than face arrest. Nothing serious

came of the reform efforts.

Marius (108-100 BC)

A

mix of events then brought to the fore a capable military leader, Gaius

Marius, who through his important military victories became so

influential that he was repeatedly elected consul (seven times!).

On numerous occasions he moved to clean out political corruption or

incompetency in the army and public administration, save Rome itself

from invading barbarians, and institute reforms in the army to make it

more democratic and higher in morale. But the power to enact such

reforms came not from the people through the workings of the

constitution ... but instead through the use of the intimidating power

of the Roman armies Marius led (plus his own dangerous and bloody

obsession with removing anything or anyone who got in his way).

Having succeeded in his reforms, he retired. A

mix of events then brought to the fore a capable military leader, Gaius

Marius, who through his important military victories became so

influential that he was repeatedly elected consul (seven times!).

On numerous occasions he moved to clean out political corruption or

incompetency in the army and public administration, save Rome itself

from invading barbarians, and institute reforms in the army to make it

more democratic and higher in morale. But the power to enact such

reforms came not from the people through the workings of the

constitution ... but instead through the use of the intimidating power

of the Roman armies Marius led (plus his own dangerous and bloody

obsession with removing anything or anyone who got in his way).

Having succeeded in his reforms, he retired.

The "Social War"

his

title describes various events that accompanied a shifting of power

within Roman society as Rome moved through the last century BC.

Reformers now fought back and forth in support of this political

interest or that political ideal – violently. Marcus Livius

Drusus was assassinated in 91 BC after alienating the Senate with his

efforts to move things in favor of the Roman commoners – and Italian

allies desiring full citizenship as members of the Empire.

After revolts by Rome's Italian neighbors, and after Marius was returned to military service – along with a new figure, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

– order in Italy was restored … although the Senate decided in 88 BC to

go ahead and extend citizenship to its neighbors anyway. But this

merely promoted a further spirit of reform under the Tribune, Publius,

bringing the Senate again to reaction. After revolts by Rome's Italian neighbors, and after Marius was returned to military service – along with a new figure, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

– order in Italy was restored … although the Senate decided in 88 BC to

go ahead and extend citizenship to its neighbors anyway. But this

merely promoted a further spirit of reform under the Tribune, Publius,

bringing the Senate again to reaction.

Thus Sulla decided to march his army into Rome and end the reform

momentum … in the process decreeing a number of political changes which

reduced the powers of the people's Tribune and made the aristocratic

Senate more absolutely the ruler of Rome. He also had numerous

individuals arrested and executed … and even turned on Marius –

declaring him to now be an outlaw. He then headed off to Asia

Minor to put down a rebellion there.

This prompted Marius to make his own military move on Rome, killing a

number of opponents, and in 86 BC having himself elected as Consul (his

8th time) … to once again put in place a number of popular

reforms. But he died a few weeks later and chaos thus simply

spread throughout Italy.

Then in 82 BC, with his campaign in the East completed, Sulla returned

to Rome – again in full accompaniment by his army – and confirmed his,

not Marius's, reforms as the model for Rome. Sulla then retired.

The slave rebellion led by Spartacus

However, a

reign of terror rested over the land – producing the semblance of peace

only through fear. Whole regions lay desolate. And in 73-71

BC the slaves (joined by the Roman paupers) even went into revolt led

by the gladiator Spartacus, conditions having become so bad. However, a

reign of terror rested over the land – producing the semblance of peace

only through fear. Whole regions lay desolate. And in 73-71

BC the slaves (joined by the Roman paupers) even went into revolt led

by the gladiator Spartacus, conditions having become so bad.

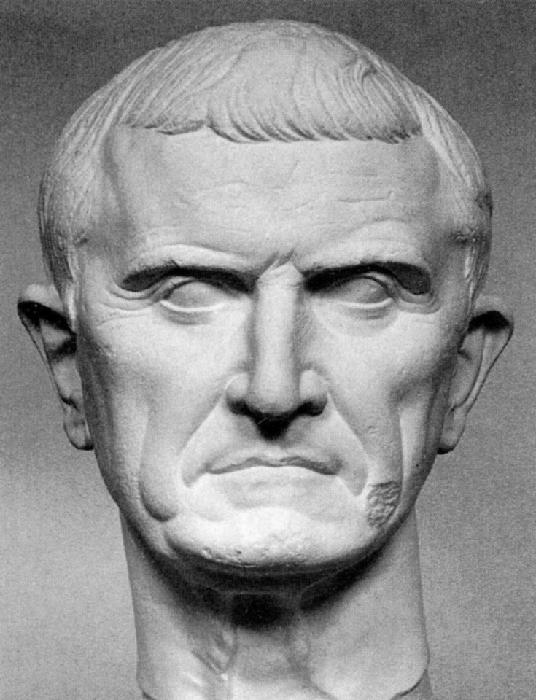

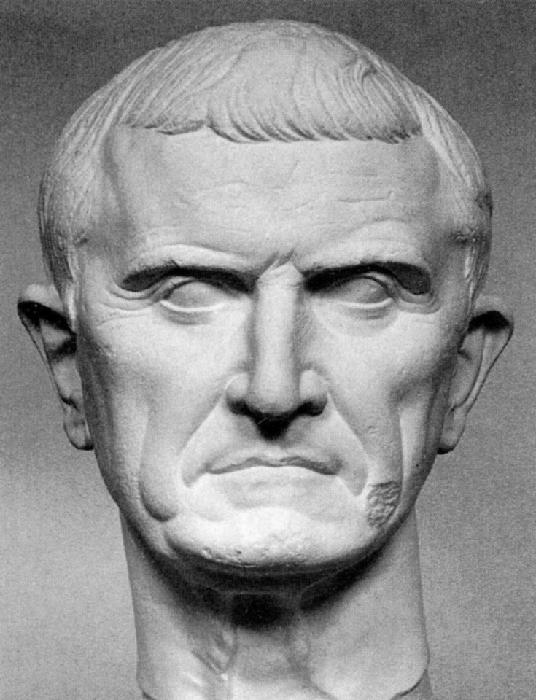

Finally the Senate called on the very wealthy patrician, Marcus Licinius Crassus,

to suppress the rebellion. Crassus's legions chased down

Spartacus's rebel army, crushed the rebellion, and lined the Appian Way

with 6,000 crucified (hung on wooden crosses) bodies from Rome all the

way south to Capua (120 miles).

The End of the Republic

Ultimately Rome was finding itself being captured by its captive

cultures …and by those most responsible for such capture, the Roman

army. Ultimately the Empire, built on military rather than Roman

family power, both noble and common, would replace Republican Rome –

for better or worse.

The Triumvirate: Caesar, Crassus and Pompey.

Three key figures would soon come together in an effort to bring Rome

back to some kind of order. All three, of course, were military

leaders. One of these was Julius Caesar, nephew of Marius and of

the reform party. Caesar was not only a capable military

commander, he was a skilled politician – who understood how important

it was to sell his greatness … by making the Roman world aware of his

successes in war – specifically in the publication of his account of

his actions in the Gallic Wars

(58-51 BC). Previously, in 62 BC, Caesar skillfully aligned

himself politically with the well-respected Crassus, and with the

Senate, getting an agreement – with the equally well-respected Pompey –

to form a three-way joint rule or triumvirate for Rome. Each of

the three would be given areas to govern (on the basis of the military

power under each of them): Crassus was given Syria and the Roman

East to govern; Caesar was given Gaul and the regions across the Alps

(thus his Gallic Wars); and Pompey was given Spain. The Triumvirate: Caesar, Crassus and Pompey.

Three key figures would soon come together in an effort to bring Rome

back to some kind of order. All three, of course, were military

leaders. One of these was Julius Caesar, nephew of Marius and of

the reform party. Caesar was not only a capable military

commander, he was a skilled politician – who understood how important

it was to sell his greatness … by making the Roman world aware of his

successes in war – specifically in the publication of his account of

his actions in the Gallic Wars

(58-51 BC). Previously, in 62 BC, Caesar skillfully aligned

himself politically with the well-respected Crassus, and with the

Senate, getting an agreement – with the equally well-respected Pompey –

to form a three-way joint rule or triumvirate for Rome. Each of

the three would be given areas to govern (on the basis of the military

power under each of them): Crassus was given Syria and the Roman

East to govern; Caesar was given Gaul and the regions across the Alps

(thus his Gallic Wars); and Pompey was given Spain.

Pompey was understood to be the key figure in the triumvirate – and

took the lead in putting down rebellions in Syria (bringing it in as a

Roman province) and even marching his armies all the way East to the

Euphrates River (modern central Iraq) and the Caspian Sea.

Pompey was understood to be the key figure in the triumvirate – and

took the lead in putting down rebellions in Syria (bringing it in as a

Roman province) and even marching his armies all the way East to the

Euphrates River (modern central Iraq) and the Caspian Sea.

But Caesar was just as energetic, not only in bringing Celtic Gaul

under Roman rule, but in undertaking popular public works projects

ranging from public games to new roads. He also pushed for the

extension of Roman citizenship to the Italians of north Italy.

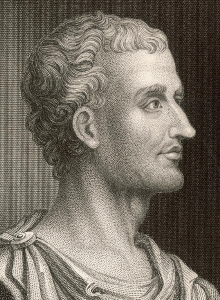

Marcus Tullius Cicero.

Cicero was a self-appointed spokesman for conservative middle-class

interests – neither in favor of the patrician Senate nor the urban mobs

that threatened the old Republic. Cicero's election as Consul in

63 BC was in testimony of his appeal to this middle class, plus the

willingness of the patrician Senators to back him in fear of a worse

fate from the populist radicals. Marcus Tullius Cicero.

Cicero was a self-appointed spokesman for conservative middle-class

interests – neither in favor of the patrician Senate nor the urban mobs

that threatened the old Republic. Cicero's election as Consul in

63 BC was in testimony of his appeal to this middle class, plus the

willingness of the patrician Senators to back him in fear of a worse

fate from the populist radicals.

He was opposed by the fellow Senator Catiline, a very corrupt former

governor of Africa, who conspired to engineer widespread discontent

among a whole spectrum of people within the Republic (from the

supporters of Sulla, to the slaves, to even the people recently brought

by conquest into the Roman order), in order to make himself

dictator. Cicero, informed by Crassus of Catiline's plans,

exposed Cataline's plot – forcing Cataline to leave Rome … and take on

a Roman army sent after him, which resulted in Catiline's defeat and

death in battle.

Cicero was very alarmed at what was the clear deterioration of the

constitutional foundations of the Roman Republic – and thus of the

Republic itself … which he made in his many speeches (recorded in

Orations) and his writings (for instance, his very popular De

Officiis). Sadly, his efforts availed little in keeping the

Republic on its original foundations … although those same efforts

would serve very well in getting much later generations to understand

what constitutes excellent, and what constitutes destructive, social

dynamics.

6The

great American sage, Ben Franklin, was well aware, thanks to Rome's own

historical witness, of this problem facing any constitution.

Franklin had personally observed the severity of the political splits

hindering the creation of America's Constitution of 1787 … and the

difficulties involved in getting these groups to rise above

self-interest in order to finally develop a Constitution for all

Americans. Thus when questioned at the end of the long

Constitutional Convention (May-September 1787) and asked what kind of

government the delegates had finally come up with, he answered: A Republic … if you can keep it.

Tragically America has lost sight of such

wisdom … as it has given fewer and fewer hands (for instance, only a

majority of five Supreme Court justices) full power to rebuild the

American Constitution any way this small group chooses to do so.

Thus America's Constitution itself has become less "constitutional" and

more "political" over time ... like the Roman Republic in its last days.

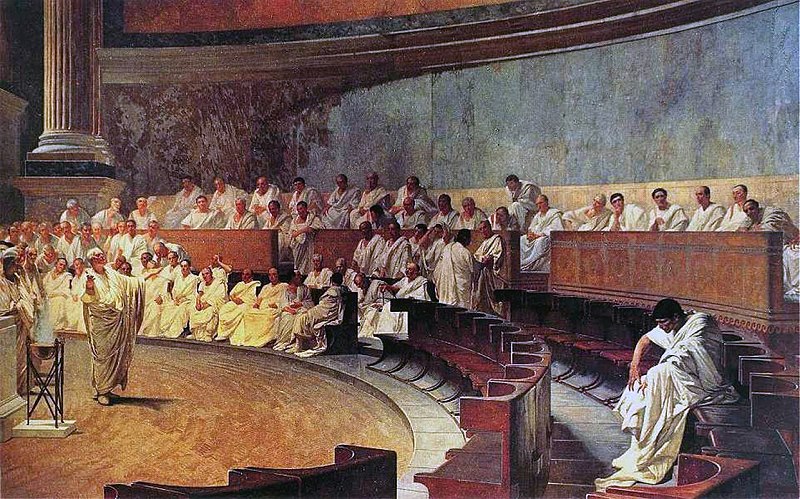

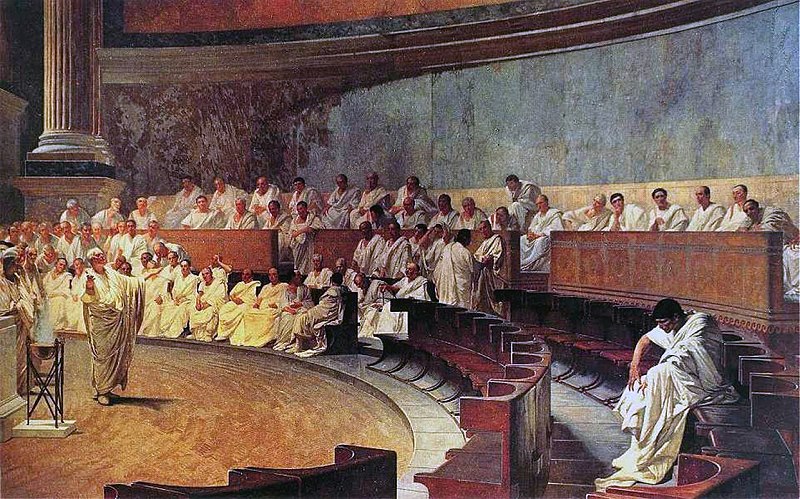

Cicero denounces Catiline

(by Cesare Maccari -1889)

|

Caesar Takes Full Power

When

in 53 BC Crassus was killed in battle against the Parthians (Persians),

a two-way power division now existed between Caesar and Pompey.

Also, despite the putdown of Cataline, riots and general disorder were

increasing in the capital – and in 52 BC even Cicero admitted to the

need to confer extraordinary powers on Pompey, now sole Consul.

Pompey became flattered by his title, and by all the attention of the

Senate … and was soon drawn into a Senate-inspired conspiracy against

Caesar.

The plan was not to renew Caesar's appointment as Consul – and indeed

to have him step down from his military command immediately. This

would then require Caesar to return to Rome to stand for re-election

without the military support that had by this time become all-essential

for success in Roman politics. Caesar refused. The Senate then

expelled his supporters – and Caesar at that point knew that he had to

take drastic steps to save himself. In March of 49 BC he crossed

with his troops into Italy, entered Rome at the head of his army

(Pompey and the majority of the Senate fled to Greece) and became the

sole ruler of Rome. |

ROMAN

INTELLECTUAL CULTURE DURING THE YEARS OF THE REPUBLIC |

|

Rome

never achieved the intellectual uniqueness of the Greek world … nor did

it attempt to do so. It was impressed enough with its ability to

simply draw on that Greek intellectual legacy for its own cultural

purposes. But nonetheless, there were numerous Romans who did

indeed add important items to that now Greco-Roman legacy.

Polybius (ca. 200 to 118 BC

Polybius was not a Roman, but instead a Greek scholar and politician, who wrote a history about the rise

to power of Rome. When Macedonia was defeated by Rome in 168 BC.

he was brought as a political prisoner to Rome. But he was able

to use this misfortune to intervene on behalf of his Greek compatriots

to secure fairly gentle treatment by the Romans of the Greeks (the

Romans tended to be quite impressed with Greek civilization anyway.) Polybius was not a Roman, but instead a Greek scholar and politician, who wrote a history about the rise

to power of Rome. When Macedonia was defeated by Rome in 168 BC.

he was brought as a political prisoner to Rome. But he was able

to use this misfortune to intervene on behalf of his Greek compatriots

to secure fairly gentle treatment by the Romans of the Greeks (the

Romans tended to be quite impressed with Greek civilization anyway.)

Living there another 18 years, and becoming part of the political

circle of the powerful Scipio family, he became familiar with a number

of Roman notables. Thus when he eventually wrote the story of

Rome's rise to power (40 volumes of his Histories

covering the period up to the final conquest of Greece in 164 AD – with

only the first 5 volumes having survived to today), he did so with

particular insight.

Lucretius (96 to 55 BC)

The Roman poet and philosopher, Lucretius (Titus Lucretius Carus), was

a strong contributor to the Roman sense of material order. He was

a naturalist in the tradition of Democritus and Epicurus – holding a

very low view of the religion of his times. In his work De rerum natura (On the Nature of Things) he claimed that popular religion was the source of the worst superstitions and sources of human evil.

Cicero (again!) 106-43 BC.

Although

Cicero considered his political work to be most important activity, his

writings left a huge mark on the intellectual culture of Western

society. His writings set the standard for Latin scholarship all

the way up to modern times. He was a devoted translator and

commentator on Greek philosophy ... in particular Plato ... and wrote

extensively on Greek philosophy in order to introduce it easily to the

Roman citizen. He also develop the art of oratory to professional

standards ... being only second to the Greek Demosthenes in rank as the

greatest orators in Western history. His essy De Officiis

(On Duties), written to his son, set out the principles of honorable or

noble public service ... and had such an impact on Western scholarship

that it was the second book after the Bible printed by Gutenberg. Although

Cicero considered his political work to be most important activity, his

writings left a huge mark on the intellectual culture of Western

society. His writings set the standard for Latin scholarship all

the way up to modern times. He was a devoted translator and

commentator on Greek philosophy ... in particular Plato ... and wrote

extensively on Greek philosophy in order to introduce it easily to the

Roman citizen. He also develop the art of oratory to professional

standards ... being only second to the Greek Demosthenes in rank as the

greatest orators in Western history. His essy De Officiis

(On Duties), written to his son, set out the principles of honorable or

noble public service ... and had such an impact on Western scholarship

that it was the second book after the Bible printed by Gutenberg.

Cicero's prose and oratory changed Latin from a rather ordinary or just

useful language into a powerful verbal tool able to give intricate

expression to the most complex ideas ... building Latin into the

foundational language of Western civilization ... which was then

carried forward in the West by the Christian Church ... and through the

ages the primary reading of young scholars developing their Latin

abilities.

Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro) (70 to 19 BC)

Virgil

was a Roman poet who dignified the Roman nationalist aspiration with

his vivid writings. His biggest project, one that had not yet

been completed to his satisfaction at his death, was the Aeneid.

This was the story of Aeneas, a Trojan survivor of the deadly war with

the Greeks, who set out on his own across the Mediterranean, lived for

a while in North Africa with the beautiful Dido, but in the end

tragically left her in order to journey to Italy and there establish a

settlement at Rome (a version very different from the older story of

the founding of Rome by the brothers Romulus and Remus). This

was, in short, the Roman answer to the Greek works of Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey – designed to put Roman culture on a par with Greek culture, at least in terms of its supposed antiquity and heroic origins.

But it also struck a deep moral-ethical cord (something lacking in

Homer's works) in the way it portrayed Aeneas as a man who understood

the bitter-sweet of his destiny and was willing to face that destiny as

a matter of honor and duty (pietas) – even against odds that were

greater than life.

Horace (Quintus Hortius Flaccus) (65-8 BC)

Horace was a military officer turned poet during the time of Rome's

transition from Republic to Empire ... actually rather closely

associated with Octavian's new regime. Well-born and

well-educated, he found himself on the losing side of tough Roman

politics, but was pardoned and eventually became a civil servant in the

new regime.

Poetry was a sideline of sorts for Horace ... but where he truly left

his mark on his times. He never lost his interest in Roman

politics, and his writings offered some important insights into the

dynamics of his times. His poetry was often satirical, even

caustic at times, such as his Epodes and Satires ... uncovering faults

in the world around him – and in his own life (he was very

autobiographical in his writings). He himself was also deeply

influenced philosophically by the rising Epicureanism and – to a lesser

extent – the Stoicism of the times ... evidenced strongly in his

Satires, Epistles and Odes. But ultimately, his real talent was

in putting before Roman society a higher standard of Latin literary

form ... studied carefully by succeeding generations.

Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso) (43 BC to AD 17 or 18)

Ovid was a poet ... who actually wrote a huge history of the world

(from the "beginning" or "Creation" up to the time of the death of

Julius Caesar) in the form of some 250 myths – in the 15 books

comprising the Metamorphoses.

He was very popular in his time because of the very artful way that he

presented these historical sketches ... and would be a person of great

interest again in the late Middle Ages / Early Renaissance

(1300s/1400s). These "histories" gave him the opportunity to

present matters of virtue and morality ... especially as these touch on

man's relations with the gods.

Livy (Titus Livius) (59 BC-17 AD) Livy (Titus Livius) (59 BC-17 AD)

Livy created an invaluable History of Rome

covering the period from the rise of Rome up to his own time ... just

as the empire was beginning to replace the republic under Augustus

Caesar. Understandably, Livy was very well appreciated in his own

time. Unfortunately, only portions of his work have survived down

to today, probably lost sometime during the Middle Ages. But we

have today Books 1-10 and 20-45 ... the rest (books 11-20 and 46-142)

being lost to us. Nonetheless, what we do have gives us an

excellent glimpse, from a very practical standpoint, of Rome's

development ... beginning as far back as the period of Etruscan

domination and Rome's spread across Italy.

|

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | |

An overview of Republican Roman

An overview of Republican Roman The expansion of Republican Rome

The expansion of Republican Rome

Early Roman political organization

Early Roman political organization

Roman intellectual culture during the

Roman intellectual culture during the