|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

BC

44 Julius Caesar is murdred at a meeting with the Senate

42 Caesar's great nephew (and adoptive son) Octavian joins forces with Marc Antony ... and at the Battle of Philippi with 17 legions) defeat the army (19 legions) of those responsible for Caesar's death

Octavian takes

leadership in the Western half of the Empire based in Rome ... Marc

Antony leads the Eastern half, from his base in Alexandria, Egypt

33 Marc Antony divorces his wife (Octavian's sister) to marry Cleopatra, embittering Octavian

31 Octavian and Marc Antony meet in battle at Actium ...Octvian is victorious

30 Marc Antony and Cleopatra choose suicide rather than be paraded as prisoners in Rome

29 All of Rome comes under Octavian "Augustus" Caesar (29 BC - AD 14)

The Roman Empire is thus born

AD

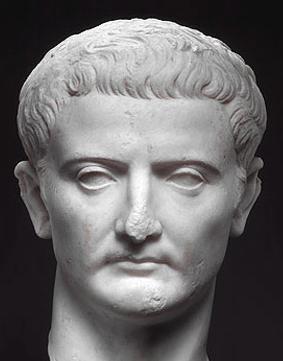

14 Octavian's step-son Tiberius takes power (14-37), an excellent general ... but increasingly

paranoid as Rome's emperor (killing many of those close to him)

41 His grandnephew Caligula was insane ... and assassinated after only 4 years of rule (37-41)

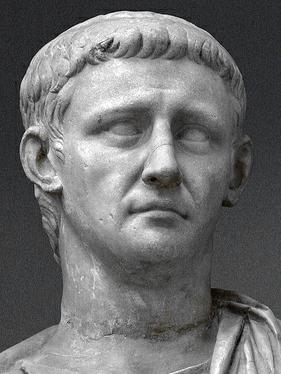

He is replaced by his

uncle Claudius (41-54) ... Claudius put in power by the Praetorian Guard... supposedly imperial body guards, but taking on the role as

emperor-makers

43 Claudius begins the actual conquest of Britain

54 A paranoid Claudius is poisoned ... over the matter of his successor

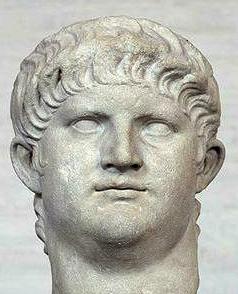

Nero, Claudius's young (only 16) adopted son becomes emperor (thanks to his mother) ...

also eventually proving to be paranoid and murderous

60 Queen Boudica inspires a massive British revolt against Roman domination ... but Rome crushes the revolt the next year (61)

64 Rome burns widely ... and Nero turns cruelly on the Christians to deflect blame directed against him for the fire

65 Nero orders the philosopher Seneca to take his own life

68 Seeing that he has lost all support, a young Nero commits suicide ... ending the Julio-Claudian imperial line

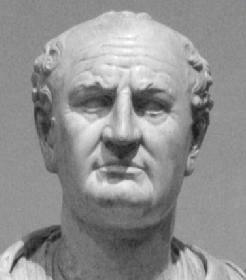

69 After four years of military conflict over emperorship, General Vespasian emerges as the

victor ... having crushed a massive Jewish revolt (67-69)

Vespasian turns out to be an excellent administrator (69-79)

79 His son Titus briefly becomes emperor (dies in 81) ... at a time that Mount Vesuvius erupts and destroys the city of Pompeii (79) ... and Rome undergoes another

huge fire (80)

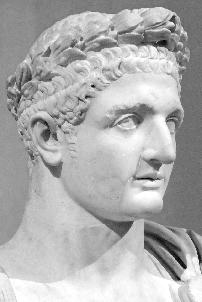

81 His brother Domitian becomes emperor (81-96); balances his government's finances by

seizing the property of this opponents; offers the commoners "bread and

circuses"

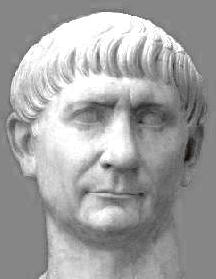

98 Trajan (98-117) brought to power by his military ... which he also uses to extend Roman power deep into Persian territory; he faces another Jewish rebellion;

dies exhausted

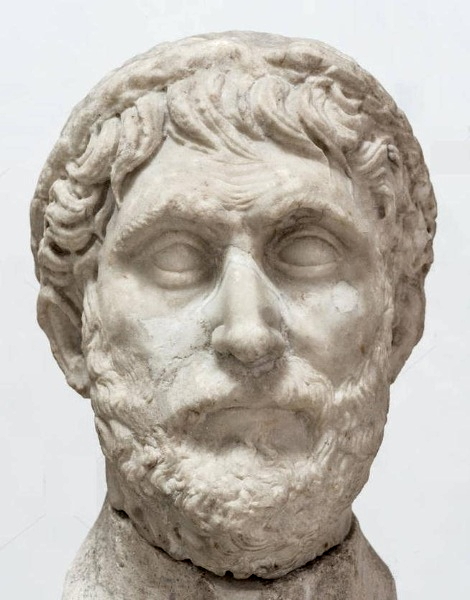

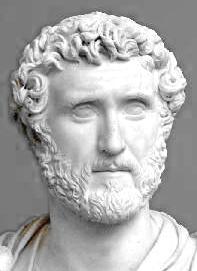

117 Hadrian (117-138) is chosen to succeed Trajan; Hadrian returns territory to the Parthians (Persians) but holds the line in Britain against invading

Scots (Hadrians' Wall - 122)

138 Hadrian's devoted follower, the non-military Antoninus Pius (138-161), comes to power ... and gives Rome a long period of peace as an excellent administrator

150? Mathematician Claudius Ptolemy publishes his Almagest ... carefully calculating the movement of the heavens ... centered not on the sun (heliocentrism) but on the earth (geocentrism)

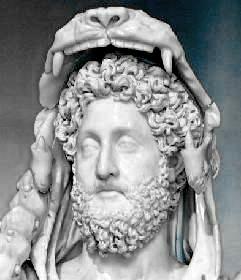

161 Soldier-philosopher (Stoic) Marcus Aurelius (61-180) had ongoing problems with the

Pathians ... and Germanic tribes pushing against Rome's borders

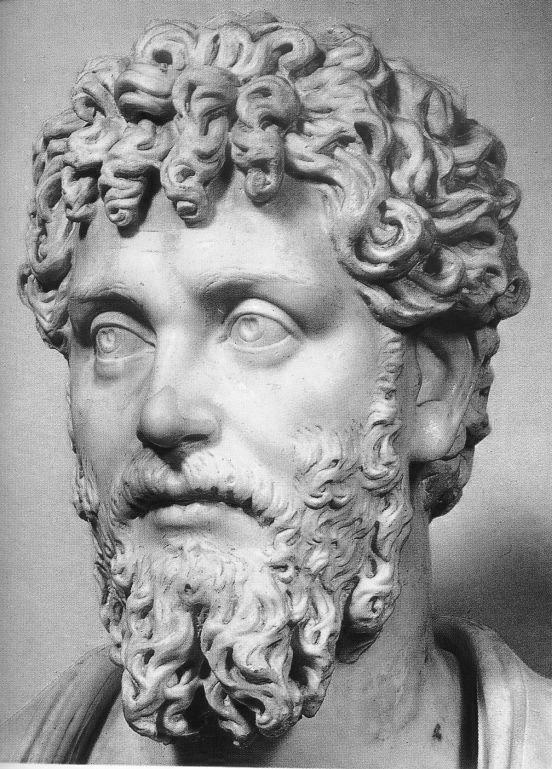

180 Marcus Aurelius's son Commodus (180-192) inherits the emperorship ... developing

paranoia and becoming increasingly insane ... beginning the decline of

the Empire

181 Septimus Severus (181-211) defeats other armies in order to take power ... and finds himself absorbed in fighting the Parthians and the Germanic tribes ...

and extending his power into Scotland – rather successful on all counts ... but exhausting Rome in the process

211 Now Rome is afflicted with weak or rapidly changing leadership ... weakening Rome even further in the face of the continuing Parthian/Gemanic

problems ... the Praetorian Guards acting as emperor-makers rather than emperor-protectors

249 Emperor Decius (249-251) engages in intense persecution of the Christians ... who are growing in number across the Empire

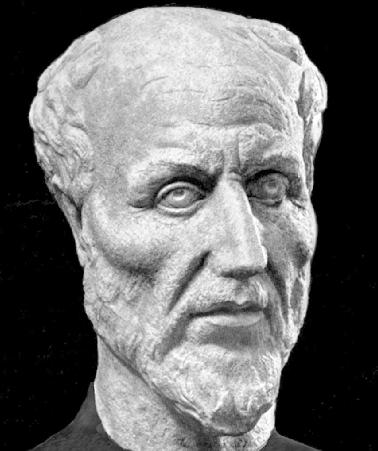

250 The Philosopher Plotinus develops "Neo-Platonism" with his Six Enneads

253 Emperor Valerian (253-260) continues to face the Persian and Germanic threats ... and also

continues the harsh persecution of Christians ... many highly placed in

Roman society

270 Emperor Aurelian (270-275) briefly recovers some of Rome's lost power ... but too is assassinated by Pretorian Guard ambitions

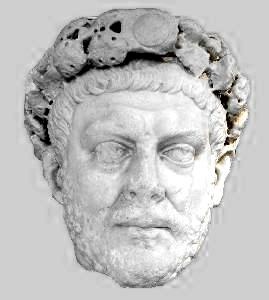

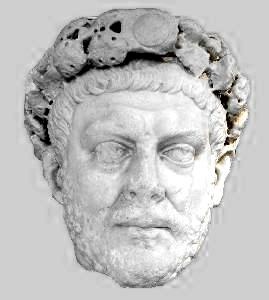

285 Diocletian's troops bring him to power (285-305) as emperor ... who then divides Rome into four major adminstrative territories, each with their own leader (thus

a "tetrarchy") ... and comes down hard on non-pagan religions – first the followers of Mani, a bit of a spin-off from Christianity, and then on Christianity itself

305 Confusion results in the effort to continue the tetrarchy after Diocletian ... setting military contenders (and their sons) up against each other over the next years

312 Constantine defeats his contender for power in the Western half of the Empire

313 With the publication of the Edict of Milan by Constantine and his co-emperor, Licinius, all persecution of Christians comes to an end

324 Constantine defeats and executes Licinius ... making Constantine Rome's sole ruler

THE

BIRTH OF IMPERIAL ROME |

|

Julius Caesar (r. 49-44 BC).

Caesar's rule proved to be surprisingly generous in its response to his

opposition – and in his bringing his own followers in Rome to order.1

In his land allotment to his soldiers he opened new lands – colonies in

Carthage (Africa) and Corinth (Greece) – rather than confiscate land

from his opponents. He tightened up on the administration of the

wheat dole and the number of public events that had made him once so

popular with the Roman masses. Towns in decline in Italy were

rebuilt and resettled and labor was opened up to the many unemployed

commoners. He established the new Julian calendar,2

regularized the public administration, straightened out the treasury,

and removed a great deal of corruption among public officials.

And for himself, he acknowledged only his title as imperator3

– head of the Roman military. But the old constitution still remained

in force – even as it accepted this new approach to governance (but not

unprecedented – as in Sulla's dictatorship). Thus although Rome

continued to present itself as a constitutional Republic, Caesar ran

the government personally and totally.

But

he mistakenly believed that he had finally won the hearts of the

Senators. And thus, just as Caesar was about to depart for the East to

fight the troublesome Parthians (March 44 BC) – and despite warnings

not to do so – he presented himself before the Senate ... only to be

assassinated by those he thought were his friends. Supposedly

this plot was undertaken to save the Republic. But in fact, all

that these senators achieved was chaos in Rome … and the need for

another strong figure to take control – so as to bring Rome back to

good order.

The Republic was now dead … even though Rome would continue to call itself a "Republic."

Civil war.

Again Cicero tried to organize the pro-Republican sentiments among the

people. But Rome was deeply divided in sentiment over the

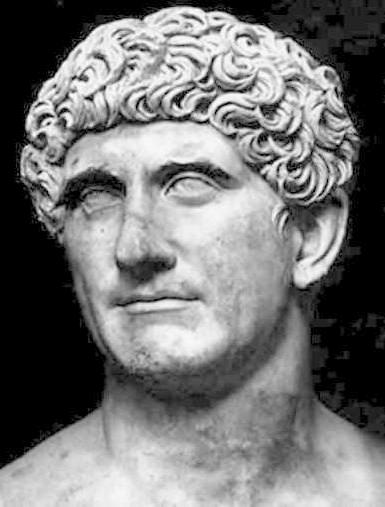

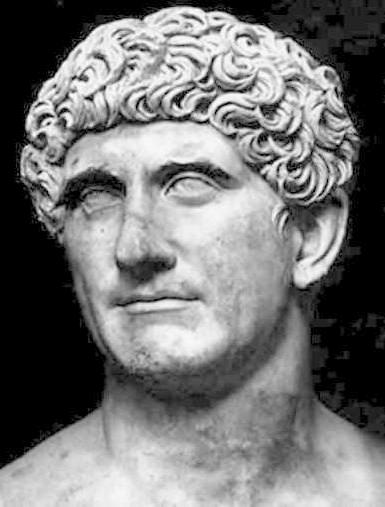

restoration of the old Republic. In the meantime, Marc Antony

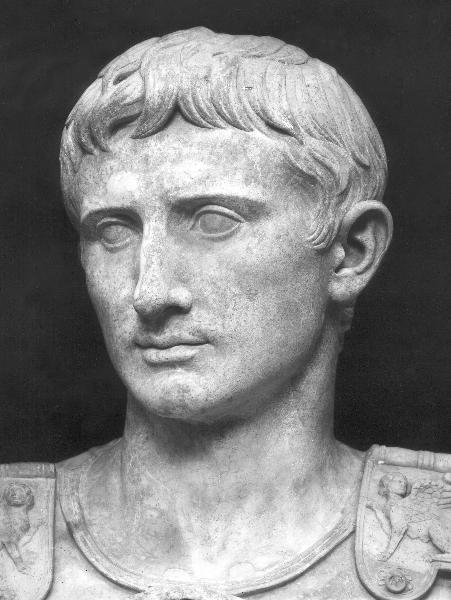

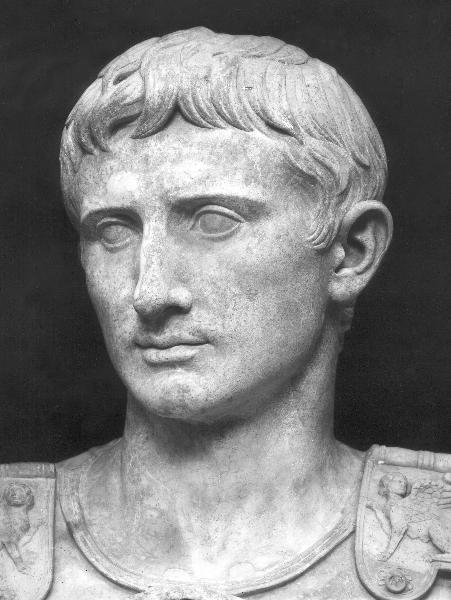

took up the cause of avenging Caesar. Also Octavian Augustus

Caesar (63 BC - AD 14), the 20-year-old great nephew (adoptive heir) of

Caesar, recently elected consul, soon joined forces with Antony – after

a period of bitter rivalry – in 43 BC). The following year they

gathered a huge army (17 legions) and took on the "Liberators"

responsible for Caesar's death (defended by 19 legions) … with Octavian

and Antony ultimately victorious at the Battle of Philippi (in

Macedonian Thrace).

Antony and Octavian thus divided the empire between them, the East

going to Antony and Italy and the West going to Octavian. Upon

that agreement, Antony (who had married Octavia, Octavian's sister in

40 BC as part of their alliance) proceeded to settle into Eastern

cultural ways – in company with Egyptian queen Cleopatra – by whom

Julius Caesar supposedly had previously fathered her young co-ruler

Caesarion ... and by whom March Antony fathered three more

children! Thus it was that Marc Antony took up Alexander's old

dream of instituting a "divine" imperial rule over the East.

Octavian

meanwhile consolidated his political position in Rome. Then when

Sextus Pompey, son of Caesar's old rival – who had tried and failed to

challenge Octavian in the West – died in 35 BC, this finally left

Octavian unchallenged in the West.

Soon Octavian turned to matters in the East. Mark Antony divorced

Octavia in order to marry Cleopatra (33 BC) – more a political than a

sexual matter actually – effectively ending his alliance with

Octavian. Seeing how this was designed to increase the power of

both Marc Antony and Cleopatra, Octavian decided that it was time to

fight. The two met in a huge naval battle at Actium in 31 BC … with

Octavian the winner. Then with Octavian advancing on Egypt, Marc

Antony and Cleopatra ultimately (30 BC) chose suicide rather than

public humiliation. This ended Ptolemaic rule in Egypt … as Egypt

now came under Octavian's direct rule (29 BC).

1

So important did the family name "Caesar" become, that it came to be

used simply as a title of authority by Roman rulers … all the way down

to the 20th century, when Russian rulers were called Czars or Tsars –

simply a Russian rendering of the name Caesar – in the same way the

German emperor was called the Kaiser.

2This

replaced the previous Roman calendar based on 12+ annual lunar cycles,

reallocating days of the lunar calendar, plus adding an additional day

in February ("leap year") to compensate for solar drift. This

would remain as the West's calendar up until 1582, when Pope Gregory

XIII put the new Gregorian calendar into effect – simply accounting for

the slight drift over the centuries … thus, for instance, the 13 days

difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars as of today –

with the Julian calendar still being used by the Eastern Orthodox

Church!

3The words "emperor" and "empire" are simply modern English's translation of the ancient Latin imperator and imperium.

In short, an "empire" (imperium) is a society built on the power of its

military and its military commanders (imperators) – as so many

societies even today find themselves. They may not be huge

"empires," but they are definitely run by the military … … as was the

First French Empire under its Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (1804-1815)!

Octavian Caesar

Marc Antony

Cleopatra VII

|

Octavian "Augustus" Caesar builds all Roman power around himself as "Emperor"

Two

years later (27 BC) Octavian presented a plan for a restored Republic

with powers supposedly returned to the Senate and the people of

Rome. But his reforms of the Roman constitution did quite the

opposite, by turning over to Octavian all major public offices.

He took for himself the title of "princeps," an old title not unknown

to the Republic, and also the designation as augustus.4

In that same year the Senate accorded him for a 10-year period (renewed

several times) oversight of the Imperium as commander-in-chief of the

Roman Army. He also took for himself the civil title of Tribune (tribunicia potestas)

– to broaden the look of his power base so that it appeared as if it

had a traditional Republican foundation as well as just a military

foundation.

Then

in 23 BC he let the older, formerly more important title of consul

lapse ... but retained the military title of imperator for himself – a

clear indication that the military position over the imperium was much

more important than the old leadership position of consul. Thus

it came to be that it was not the constitution, nor the Senate that

mattered most in the new regime, but it was solely the military and its

role in Roman public life that now stood behind all Roman public

power.

And thus Rome as "Empire' was born.

Also

in 12 BC, when an old political ally died, his priestly position as

pontifex maximus was taken up by Augustus. He was careful to

avoid trying to appear in Rome as a mystical ruler, a representative of

the gods. But he easily took up that role in the East where that

was exactly what was expected of their rulers. Eventually this

mindset would enter Rome itself — especially through the slaves brought

in in huge numbers from the East.

The deeper social impact of these changes

Unfortunately,

Octavian based himself on the power of the military at a time (just

about the time of Christ) when the military was depending less and less

on recruits from the Roman middle class and more and more on fortune

hunters drawn from conquered peoples. Their loyalties were less

to Rome than to their generals. Thus also – and most sadly –

under the new Imperial dynamic, it was often in rapid succession that

rising generals (emperors) would take command – as the military (or at

least military fortunes) made and unmade emperors at will. The

Roman public played no role in these developments.

Also,

the military needs and military expenses of the Roman Empire were

limitless. After a while there were no more rich neighbors for

Rome to plunder and the Empire had to rely on the resources of its own

people to pay for its ongoing and extravagant military ventures.

Mercenaries hired from Rome's former (or even continuing) enemies

replaced the patriotic free citizen-soldiers of Rome, the latter,

impoverished from too great a demand for their increasingly lengthy

term of military service, now falling into terrible poverty. Soon

the city's slums were filled with the once free citizen-soldiers and

their families. And thus the Empire lost touch with what it once

was.

True

... military governance acted to unify the Empire. But actually

it was the economic prosperity which Rome clearly brought its world

that kept human hearts loyal to the whole program.

At

first the new imperial system seemed to work well enough.

Octavian Augustus' long rule provided the sprawling empire with the

kind of stability needed for prosperity to become widespread

everywhere. By and large, revolts disappeared and the scene of

Roman legions gathering against each other to secure a change in

political leadership was no longer to be seen … for quite a long while.

Augustus' Successors: The Julio-Claudians (14-68 AD)

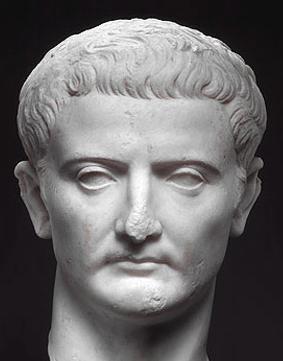

Tiberius (14-37 AD).

Tragically, those that followed Octavian did not have the same strength

of character. And Rome would suffer as a result. Tiberius

started out well. But with time, Tiberius descended into a highly

paranoid condition, executing many around him that he suspected of

personal disloyalty (including many of his personal relatives). Tiberius (14-37 AD).

Tragically, those that followed Octavian did not have the same strength

of character. And Rome would suffer as a result. Tiberius

started out well. But with time, Tiberius descended into a highly

paranoid condition, executing many around him that he suspected of

personal disloyalty (including many of his personal relatives).

His grandnephew Caligula (37-41 AD) was probably insane … and was soon assassinated..

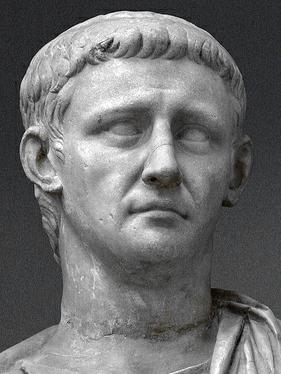

Claudius (41-54).

Caligula's uncle (and Tiberius's nephew) Claudius replaced him – just

as the Senate was giving thought to restoring the Republic. But

the army's Praetorian Guard (personal body guard of the Emperor)

stepped in and declared Claudius emperor – putting an end to the

matter. This would tragically mark the beginning of the role of

the Praetorian Guard as emperor-makers – as well as emperor "unmakers"

or assassins, according to their own political preferences.

Claudius too developed violent suspicions of those around him, in

particular a number of Senators. In AD 54 he was probably

poisoned – possibly by his wife (who was certainly afraid that he was

going to pass over her son Nero in favor of another imperial candidate). Claudius (41-54).

Caligula's uncle (and Tiberius's nephew) Claudius replaced him – just

as the Senate was giving thought to restoring the Republic. But

the army's Praetorian Guard (personal body guard of the Emperor)

stepped in and declared Claudius emperor – putting an end to the

matter. This would tragically mark the beginning of the role of

the Praetorian Guard as emperor-makers – as well as emperor "unmakers"

or assassins, according to their own political preferences.

Claudius too developed violent suspicions of those around him, in

particular a number of Senators. In AD 54 he was probably

poisoned – possibly by his wife (who was certainly afraid that he was

going to pass over her son Nero in favor of another imperial candidate).

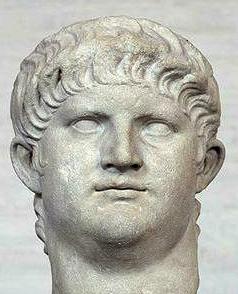

Nero (54-68)

And

then there was Nero who, with the help of his conniving mother (whom he

would anyway execute in 59!), became emperor at age 16. He

started off his reign fairly popular with the people – whom he was

always trying to please. He did what he could to beautify Rome,

building theaters and sponsoring gladiatorial contests to amuse the

people. However, his projects grew increasingly extravagant and

became a serious burden on the finances of the Empire. Also,

arrogant and by nature suspicious, Nero became increasingly paranoid

and ruthless (even murderous) to a large circle of individuals

immediately around him, including his old tutor, Seneca. And

then there was Nero who, with the help of his conniving mother (whom he

would anyway execute in 59!), became emperor at age 16. He

started off his reign fairly popular with the people – whom he was

always trying to please. He did what he could to beautify Rome,

building theaters and sponsoring gladiatorial contests to amuse the

people. However, his projects grew increasingly extravagant and

became a serious burden on the finances of the Empire. Also,

arrogant and by nature suspicious, Nero became increasingly paranoid

and ruthless (even murderous) to a large circle of individuals

immediately around him, including his old tutor, Seneca.

In

64, much of Rome burned (actually not an entirely uncommon

occurrence). Rumors were that he himself had done this in an

effort to clear the Roman slums to make way for his expensive,

ever-expanding urban beautification projects. According to the

historian Tacitus, Nero attempted to deflect the blame for the fire

onto the Christians … who were growing rapidly in number in Rome – and

also gaining a bad reputation for their un-Roman "secret" ways.

He attempted to validate his own accusations against the Christians by

offering the Roman public the entertaining spectacle of horrible deaths

inflicted on members of this "vile sect."

On

the more positive side of the picture, during his reign he encountered

– and largely overcame – rebellions in various parts of the Empire,

most notably in Britain (Queen Boudica's Revolt of 60-61). Also,

Nero actually demonstrated diplomatic talent in the way he resolved a

dispute with Parthia (the former Persia) over the kingdom of Armenia

(63) and in securing a peace between these two empires that would last

50 years.

But

eventually revolt also touched the heart of Rome itself: Nero found

himself facing down rebellion and conspiracy – from many different

directions. Even the army was growing unreliable in its support

of him. Finally hearing of a major rebellion brewing, and finding

that no one supported him any longer, he took his own life (68).

He was only 30 years old at his death. And with his death the

Julio-Claudian line came to an end.

4A

term derived from the Latin, augere (to increase) and thus meaning

approximately "one who increases" … or "majestic" or "venerable."

|

The assassination of Caligula (and his wife and daughter) by the Pretorian Guard (the first of many such instances) ... and the elevation by the same Pretorian Guard of a terrified Claudius (found hiding behind a curtain) to the position of Roman Emperor by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1871)

|

THE

HEIGHT OF THE ROMAN IMPERIUM |

|

The Flavian Dynasty

(69-96)

With

no direct heir to the imperial title, and with Roman armies now more

personally loyal to their generals than to imperial authority, chaos

reigned throughout the empire. Four different emperors,

commanding four different armies, rose and fell in rapid succession in

the year and a half after Nero's death (68-69).

Vespasian (69-79).

Finally Vespasian – one of the Roman generals to have helped bring

Britain into the Roman Empire (43) during Claudius's reign, and the

leader of the Roman effort to crush the Jewish revolt which broke out

in 67 – was declared emperor by his troops in mid-69 and then by the

Senate in late 69. Vespasian (69-79).

Finally Vespasian – one of the Roman generals to have helped bring

Britain into the Roman Empire (43) during Claudius's reign, and the

leader of the Roman effort to crush the Jewish revolt which broke out

in 67 – was declared emperor by his troops in mid-69 and then by the

Senate in late 69.

He

proved to be as excellent an administrator as he had been a

general. He brought Roman public finances that Nero had

squandered back into order – even into surplus – by raising taxes and

by a closer oversight of how public funds were spent. He

broadened the sense of Roman politics and culture by extending to Spain

and Gaul rights and responsibilities that had previously belonged to

Italy alone. He recruited troops for the Roman legions from Spain

and Gaul – and mixed the composition of the legions, separated the

legions into smaller units, and based them more widely along the

frontiers so that the legions no longer represented the interests of

any particular region of the Empire. It also made it more

difficult for any particular individual aspiring to political power to

use the army for political purposes. He expanded

the membership of the Senate (depleted by the murderous policy of his

predecessors) from 200 to 1000, giving representation to new families

and the new regions of the Empire he recently "Romanized." of the Empire he recently "Romanized."

Titus (79-81).

Vespasian's eldest son Titus succeeded his father as emperor. He

had distinguished himself under his father's rule as the commander of

the eastern legions that forced Judea back into submission. As

emperor his rule was short – and troubled. Pompeii was destroyed

by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 and in 80 much of Rome was

destroyed by fire. Otherwise he too was proving to be an

excellent administrator. But Titus died in 81 – seemingly of

natural causes.

Titus's troops carrying off

plunder from the Temple of Jerusalem

Titus's troops carrying off

plunder from the Temple of Jerusalem

(From the Arch of Titus – Rome)

No effort was made to continue the pretense of the Republic's

existence. He ignored the Senate (which grew to hate him) and

surprisingly gave no special favors to his family, very unusual in

imperial politics. He presided over a tightly organized and

surprisingly uncorrupt bureaucracy. He spent most of his time

away from the capital city, leading battles or conducting inspection

tours … and thus the seat of his government tended to be wherever he

himself was located. It was during his emperorship that Celtic

Britain was finally defeated (by General Agricola) and brought into the

Roman Empire … except for the northern portions (Scotland) whose troops

managed to escape the grip of the Roman legions.

He cultivated the support of the crowds – with lavish gladiatorial

games in the new Coliseum and through distributions of monies to the

residents of Rome. Surprisingly, his regime ended with money

still in the state treasury, probably because of all the wealth he

accumulated by seizing the property of people he had begun to

fear. In 96 he was assassinated in a plot directed by his

own court officials. But in any case, this brought the

Flavian line to an end.

The era of the "Five Good Emperors" (96-180)5

The next century or so proved to be a time of relative peace and

prosperity – even what might be termed "the height" of the Roman

Empire. Five emperors peacefully succeeded each other – by the

previous emperor's adoption during his lifetime, as none but the last

of these five had a natural heir of his own. Thus the transfer of

power was based purely on a sense of true merit and not just family

interest. Rome benefitted greatly from this principle.

Nerva (96-98).

Nerva was raised in political, not military circles, and his accession

to power was via the Senate, where he was popular. He immediately

freed the people that Domitian had imprisoned and restored to them

their property he had confiscated. He also attempted to cultivate

popular support in Rome through the lowering of taxes and extensive

welfare grants to the poor. But this created financial problems

for the government. Also Domitian had been popular with the Roman

army. In fact, the Praetorian Guard seized Nerva and forced him

to turn over to them the individuals involved in the death plot against

Domitian. Nerva's rule was brief – he was probably chosen by the

Senate because he was old and childless – and he died of a stroke after

only two years of rule. Nerva (96-98).

Nerva was raised in political, not military circles, and his accession

to power was via the Senate, where he was popular. He immediately

freed the people that Domitian had imprisoned and restored to them

their property he had confiscated. He also attempted to cultivate

popular support in Rome through the lowering of taxes and extensive

welfare grants to the poor. But this created financial problems

for the government. Also Domitian had been popular with the Roman

army. In fact, the Praetorian Guard seized Nerva and forced him

to turn over to them the individuals involved in the death plot against

Domitian. Nerva's rule was brief – he was probably chosen by the

Senate because he was old and childless – and he died of a stroke after

only two years of rule.

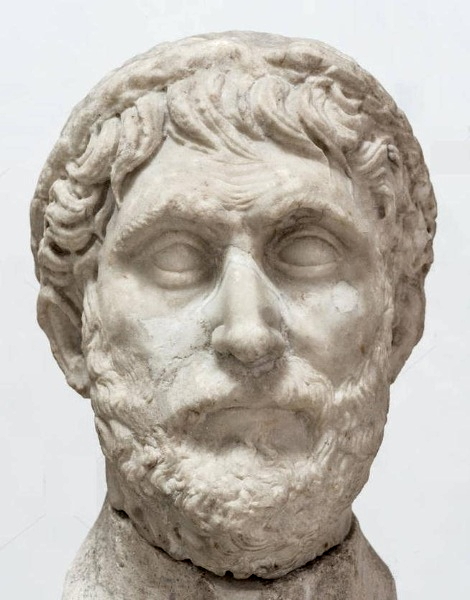

Trajan (98-117).

He was followed by Trajan, who proved to be a capable administrator as

well as a promoter of further military successes for Rome. He

built in Rome both a new forum and market and some important ceremonial

landmarks (Trajan's column). But it is in the area of military

and diplomatic policy that he is best remembered. Under his rule

the Empire reached its furthest extent. He marched into Armenia

and placed his own man on the Armenian throne. Then in 116 Trajan

continued his conquest into Parthia itself, seizing Babylon, Ctesiphon,

and Susa, deposing Osroes, and placing his own ruler on the Parthian

throne. But the venture overtaxed his energies – and he faced

rebellion in many places in the newly expanded Empire.

Mesopotamia was restless, and once again the Jews rose up in rebellion

against Rome. Very ill, he managed to return to Rome before he died

there in 117. The Romans knew that they had lost a great Emperor

– one of their very best. Trajan (98-117).

He was followed by Trajan, who proved to be a capable administrator as

well as a promoter of further military successes for Rome. He

built in Rome both a new forum and market and some important ceremonial

landmarks (Trajan's column). But it is in the area of military

and diplomatic policy that he is best remembered. Under his rule

the Empire reached its furthest extent. He marched into Armenia

and placed his own man on the Armenian throne. Then in 116 Trajan

continued his conquest into Parthia itself, seizing Babylon, Ctesiphon,

and Susa, deposing Osroes, and placing his own ruler on the Parthian

throne. But the venture overtaxed his energies – and he faced

rebellion in many places in the newly expanded Empire.

Mesopotamia was restless, and once again the Jews rose up in rebellion

against Rome. Very ill, he managed to return to Rome before he died

there in 117. The Romans knew that they had lost a great Emperor

– one of their very best.

5This was a term assigned by Roman historians, most of them of the Senatorial class, and thus politically biased in their appraisal of Rome's various

emperors.

The furthest reach of the Empire - 117 AD

He saw himself as something of an intellectual as well. He

greatly admired Greek philosophy and literature (he even started the

fashion of wearing a beard, Greek-style) and considered himself a poet

and a Stoic and Epicurean philosopher.

The end of his rule was marked by a major crisis in Judea – where he

faced a massive and destructive revolt by the Jews, led by Bar

Kokhba. The problem began when Hadrian had Jerusalem rebuilt

(destroyed in the earlier 67-70 Jewish rebellion) – but as a Roman

city, Aelia Capitolina. He also erected a temple to Jupiter on

the foundations of the leveled Jewish Temple. And he decreed an

end to the "barbaric" Jewish practice of circumcision. This

proved to be too much to the Jews and in 132 they rose up again in

rebellion. The Jews proved to be very difficult to tame: Hadrian lost

possibly an entire legion to the Jews, and had to call in legions from

all around the Empire to finally bring the Jews to submission

(135). The loss of Jewish life and social position was

enormous. Furthermore, from that point on, a vindictive Hadrian

dedicated himself to rooting out Judaism from the Empire.

But his health at this point was failing … and he died in 138.

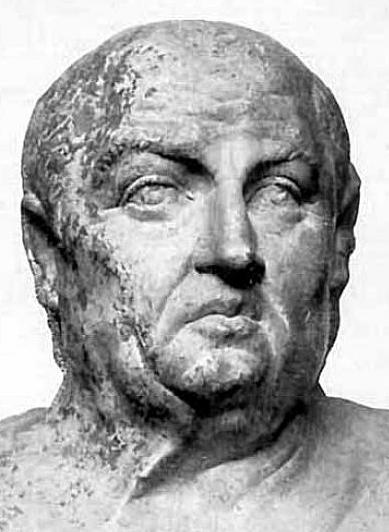

Antoninus Pius (138-161).

Antoninus was a devoted follower of Hadrian, even pressuring the Senate

to deify Hadrian – thus himself receiving the title "Pius" for his

devotion to Hadrian. Interestingly, Antoninus did not come to

prominence as a military man – nor did he ever develop any relationship

with any of the legions, as had those before and after him. His

rule was the most peaceful of any in the long run of the Empire –

though he had to deal with relatively small military disturbances from

time to time. He never left Italy to personally face

disturbances, but always worked through Rome's governors – drawing

praise from many for his relatively peaceful handling of Roman

politics. However, this seemed to have produced the impression of

Roman weakness in the estimation of many of Rome's enemies (such as the

ever-troublesome Parthians) – which his successors would have to deal

with. Antoninus Pius (138-161).

Antoninus was a devoted follower of Hadrian, even pressuring the Senate

to deify Hadrian – thus himself receiving the title "Pius" for his

devotion to Hadrian. Interestingly, Antoninus did not come to

prominence as a military man – nor did he ever develop any relationship

with any of the legions, as had those before and after him. His

rule was the most peaceful of any in the long run of the Empire –

though he had to deal with relatively small military disturbances from

time to time. He never left Italy to personally face

disturbances, but always worked through Rome's governors – drawing

praise from many for his relatively peaceful handling of Roman

politics. However, this seemed to have produced the impression of

Roman weakness in the estimation of many of Rome's enemies (such as the

ever-troublesome Parthians) – which his successors would have to deal

with.

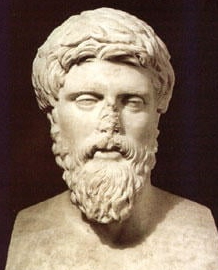

Marcus Aurelius (161-180).

However, the next "Good Emperor," Marcus Aurelius, was very much the

military man … as well as an excellent Stoic philosopher! Marcus Aurelius (161-180).

However, the next "Good Emperor," Marcus Aurelius, was very much the

military man … as well as an excellent Stoic philosopher!

But during his first years in power, he shared the position as emperor

with his adoptive brother, Lucius Verus, whom he raised to power in

order to help him run the huge Empire. Verus proved to be a huge

help in getting the Parthian threat reduced. But Verus would fall

ill and die in 169, leaving Marcus Aurelius to continue his rule alone.

Marcus Aurelius had the very best education of the time and

demonstrated a keen intellect very early in life. He had a

natural affinity for philosophy – which would reveal itself later when

he became Emperor.

Marcus Aurelius was very much the military man – called upon to deal

with not only the ongoing Parthian problem to the East … but to the

increasingly serious problem of the movement of Germanic tribes up to

Rome's northern borders – the Germanic tribes themselves pushed into

that position by other tribes behind them, trying to escape the

pressures of population growth, climate problems, and hunger.

As ruler of a mighty empire, there was something Solomon-like about

Marcus Aurelius. From 170 until his death in 180, he recorded his

thoughts (in Greek) on life, death, virtue, human purpose, etc. – that

had all the qualities of Solomon's philosophical reflections found in

Ecclesiastes in the Hebrew Bible … or even of Buddha's teachings about

the folly of human desire. His writings were later collected into

a single work, Meditations. It is a classic in Stoic thought.

In 178, he was forced to turn his attention back to the Germans along

the Danube. He again defeated the Germans soundly. But

Marcus's health was failing him and he died in 180 at Vindobona

(Vienna) along the German border.

|

|

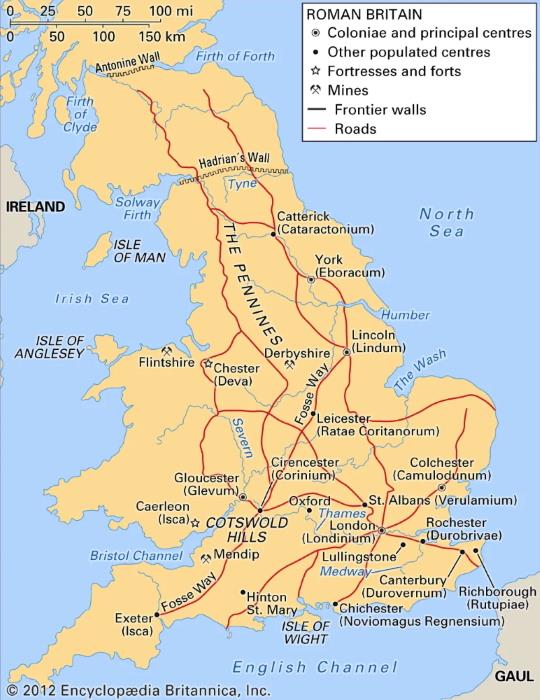

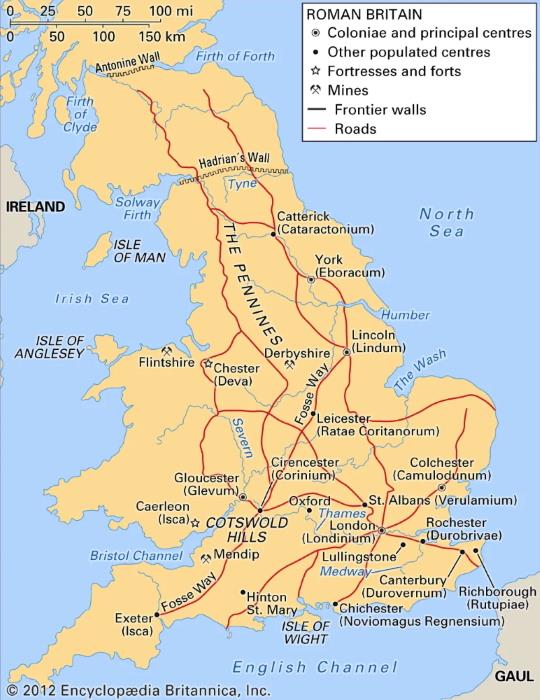

Roman Britain

(basically a footnote!)

Early efforts at establishing Roman rule in Britain.

Julius Caesar invaded Celtic Britain twice, in 55 and 54 BC. No

direct Roman control came of his effort – though a military alliance

with one of the Celtic kings was established (the Celts had long been

trading with Rome anyway – thus there was already some sort of

Celtic-Roman relationship in the works even prior to Rome's political

intrusion). Though the Romans were at this point awake to the

possibility of Roman expansion into Britain, no serious efforts to

subdue Britain were made by the Romans until a century later.

Claudius begins the actual conquest - 43 AD.

Beginning in AD 43, under the Emperor Claudius, the Romans began the

process of subding Britain, a region at a time. By 47 Britain

south of the Humber River and east of Wales was under Roman

control. By 60 (Nero was ruling Rome by this time) the Roman

legions had destroyed the Druid religious or political center at Mona

(or Anglesey).

Boudica's revolt—61 AD.

But the following year, 61, a major Celtic uprising led by the Celtic

Queen Boudica threatened to reverse these Roman victories.

Emperor Nero was even considering abandoning Britain when Roman legions

under Suetonius defeated a huge Celtic army -possibly 10 times the size

of the Roman army – somewhere along the main Roman road (later – in the

Middle Ages – termed 'Watling Street") which ran from the English

Channel to Wales.

Expansion into Wales and Scotland.

Over the next 20 years the Romans extended their control into Wales and

north to the Pennine Mountains – and under the General Agricola (whose

action in Britain earned enough acclaim to eventually make him Emperor)

even reached well into Scotland – though upon his return to Rome the

legions in Britain under less capable generals would be forced to pull

way back from Agricola's forward line of advance.

Holding the line against Scotland: Hadrian's Wall.

Eventually an 80-mile wall would be built across northern Britain under

orders in 122 of the Emperor Hadrian, to keep the troublesome Picts of

Scotland out of Britain. Several more attempts were made by Roman

legions to extend their control north of that line, importantly

including the effort by the Emperor Septimus Severus in the early 200s

to extend Roman rule even to northern Scotland - who slaughtered

countless Scottish Celts but also lost 50,000 of his own men – before

abandoning the effort and falling back to the line of Hadrian's wall. |

A

stretch of Hadrian's Wall

viewed from Vercovicium

near Housesteads in

Northumberland

THE

INTELLECTUAL CULTURE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE |

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (the Younger) (4 BC-65 AD).

Seneca was a Spanish-born Stoic philosopher/statesman who stressed –

and practiced – a gentle virtue in his living. He was of a

distinct intellectual background, his father (Seneca the Elder) having

been a notable rhetorician (polished public advocate before the law)

and author in his time. The younger Seneca was educated in Rome

under the Stoic Attalus, studying rhetoric and philosophy in

preparation to become an advocate (lawyer) like his father. Lucius Annaeus Seneca (the Younger) (4 BC-65 AD).

Seneca was a Spanish-born Stoic philosopher/statesman who stressed –

and practiced – a gentle virtue in his living. He was of a

distinct intellectual background, his father (Seneca the Elder) having

been a notable rhetorician (polished public advocate before the law)

and author in his time. The younger Seneca was educated in Rome

under the Stoic Attalus, studying rhetoric and philosophy in

preparation to become an advocate (lawyer) like his father.

As Seneca grew in stature and respect at Rome, he also drew suspicious

political scrutiny from the imperial party. And in 41 AD he was

banished to Corsica by the emperor Claudius. Eight years later he

was brought out of exile to become the tutor of the young Nero – who

for a while was brought up under the positive influence of Seneca.

In 57 AD Nero (now emperor) appointed Seneca Roman consul. From

this important position Seneca hoped (for a few years) to augment a

regime of enlightenment in Roman political life. But imperial

pride once again worked against the virtuous (and increasingly popular)

Seneca. Nero, now emperor and coming under the influence of an

ambitious and flattering court circle – and presuming himself to be a

great luminary of his age and thus resenting the greater light cast by

Seneca – began to undermine his old tutor's position. Sensing the

danger, Seneca quietly retired from public life.

But in 65 AD the elderly Seneca was accused (along with his

rhetorician-statesman nephew Lucanus) of being part of the failed plot

(led by Gaius Calpurnius Piso) to assassinate Nero. Nero thus

ordered Seneca to take his own life.

With Stoic reserve and resolve Seneca did as ordered – ending his life

in keeping with his Stoic understanding of life: not to place too

much thought on one's physical existence but instead to find such inner

peace that neither life nor death distract someone from his deeper

sense of inner being.

Political historians

Plutarch (ca. 45 to 125 AD). Plutarch was a Greek historian and biographer of a large number of famous Greek and Roman individuals (Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans

– also known as Parallel Lives – being his best-known work) – and the

source of much of our in-depth knowledge of many historical

figures. He came from a noble Greek family, was well educated,

and became a Roman citizen … soon finding himself moving in a circle of

prominent Romans. He ultimately served as a magistrate of his

hometown of Chaeronea – and a representative of his town on various

missions abroad. Thus it was that he wrote his biographies on the

foundation of his own personal knowledge of Greek and Roman politics

from a very practical standpoint. It was even claimed that in

Plutarch's later life Hadrian made him procurator of Achaea. But

interesting also was that in the mid-90s, Plutarch also became a priest

at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi … thus a mystic – as well as a

political secularist! Plutarch (ca. 45 to 125 AD). Plutarch was a Greek historian and biographer of a large number of famous Greek and Roman individuals (Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans

– also known as Parallel Lives – being his best-known work) – and the

source of much of our in-depth knowledge of many historical

figures. He came from a noble Greek family, was well educated,

and became a Roman citizen … soon finding himself moving in a circle of

prominent Romans. He ultimately served as a magistrate of his

hometown of Chaeronea – and a representative of his town on various

missions abroad. Thus it was that he wrote his biographies on the

foundation of his own personal knowledge of Greek and Roman politics

from a very practical standpoint. It was even claimed that in

Plutarch's later life Hadrian made him procurator of Achaea. But

interesting also was that in the mid-90s, Plutarch also became a priest

at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi … thus a mystic – as well as a

political secularist!

In

order to get his theory to work, he (and others after him) had to add a

large number of secondary explanations (following Hipparchus' use of

eccentrics and epicycles) of the peculiar movement of heavenly bodies

around the earth in order to get them to fit his theory.

His theory was widely adopted by Western thinkers – down until the

approach of modern times when it became dislodged – with much

resistance, not least of all from the Christian church.

Plotinus (205 to 270 AD). Plotinus was a developer of "Neo-Platonism." He headed Plato's Academy in Athens and there wrote the wrote The Six Enneads (250). Plotinus (205 to 270 AD). Plotinus was a developer of "Neo-Platonism." He headed Plato's Academy in Athens and there wrote the wrote The Six Enneads (250).

Like Plato, Plotinus accepted that our material world was a mere shadow of the World Soul (Psychè Kósmou)

from which human souls derive their power), which in turn was a shadow

of an even higher world, that of the Nous (where the Ideon are located)

… which was itself a shadow of the unknowable One (’έν – Hen)

or God. In other words, the world has four levels of reality: the

"Divine Triad" of God as the highest level, and then the derivative

world of the divine Nous (or Mind), then the level of the World Soul

(the bridge between the material world and the Divine Nous ... which

actually activates the material world). Then derivative of all

that is finally the visible or "sensible" material world (with its

tragic potential for evil).

According to Plotinus, the wise man would try, by means of very

rigorous self-discipline, to free his soul from the material world or

"matter" … and seek contemplative unity as high up as possible within

the Divine Triad … even possibly attaining a degree of unity with the

One. Very much like an Eastern mystic, Plotinus claimed to have

achieved this unity several times.

His pupil Porphyry organized the treatises of Plotinus (the Enneads)

and also wrote a biography of his master.

The Neoplatonic philosophy was subsequently adopted by the fathers of

the church, Ambrose (c. 339-397) and Augustine (354-430), and was to

remain the philosophical school par excellence … until Aristotle was

rediscovered in the twelfth century.

Diogenes Laertius (200s AD). Likewise, through his important 10-volume work, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers,

we possess a vastly richer knowledge about many of the ancient Greek

philosophers … although we know very little about Laërtius himself.

6Actually an Arab rendering of the title of this work The Great Treatise ('H Μεγάλη Σύνταξις – Hē Megalē Syntaxis)

… because Ptolemy was highly regarded in the Muslim world … and it was

by way of an Arab translation that Ptolemy was reintroduced to the

Western world in the 1100s.

THE DECLINE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE |

Following

the rather grand period of the "Five Great Emperors," Rome then headed

into a decline … one that Rome did not really know how to break free

from. It was all very tragic.

Commodus (180-192).

Commodus, Marcus Aurelius' son, brings the period of the "Five Good

Emperors" to an end. His rule marks the transition to very

troubled times for the Roman Empire. Although his rule began

well, a conspiracy in 182 (promoted primarily by members of his own

family) to assassinate him turned him paranoid. And from paranoia

he slipped into insanity. He loved to project himself as

Hercules, a god of great physical strength. He renamed Rome after

himself, termed all Romans as "Commodians," redrafted the months of the

calendar in using his own twelve names for the months of the

year. He did this less out of guile than out of a case of

increasing simple-mindedness. But it was his behavior in the

public arena that finally braced the Senate sufficiently to organize

his death (he would entertain Roman crowds with his slaughter of

hundreds of animals and hundreds of disabled Romans – and hold hundreds

of bloodless gladiatorial combats, which he always "won," of

course). Finally in 192 he was strangled in his bath by a

wrestler that the Senate had paid to do the job. Commodus (180-192).

Commodus, Marcus Aurelius' son, brings the period of the "Five Good

Emperors" to an end. His rule marks the transition to very

troubled times for the Roman Empire. Although his rule began

well, a conspiracy in 182 (promoted primarily by members of his own

family) to assassinate him turned him paranoid. And from paranoia

he slipped into insanity. He loved to project himself as

Hercules, a god of great physical strength. He renamed Rome after

himself, termed all Romans as "Commodians," redrafted the months of the

calendar in using his own twelve names for the months of the

year. He did this less out of guile than out of a case of

increasing simple-mindedness. But it was his behavior in the

public arena that finally braced the Senate sufficiently to organize

his death (he would entertain Roman crowds with his slaughter of

hundreds of animals and hundreds of disabled Romans – and hold hundreds

of bloodless gladiatorial combats, which he always "won," of

course). Finally in 192 he was strangled in his bath by a

wrestler that the Senate had paid to do the job.

Needless to say, Commodus had made no arrangements for a smooth

succession upon his death. Roman politics fell into further

chaos. Over the next year there were five different generals who

laid claim to the title of Emperor. Assassinations and bribes

followed in rapid succession as claimants attempted to line up soldiers

and Senators behind their claim to the throne.

The Severan Dynasty (193-235)

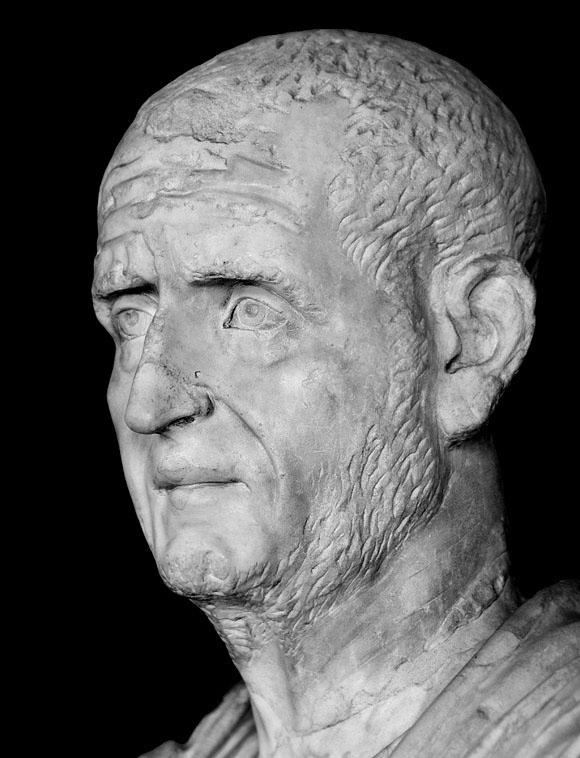

Septimius Severus (193-211).

The Roman general Septimus Severus fought his way to power by having

his army defeat the armies of other Roman generals contending for the

position as Roman emperor. He then took on the Parthians, sacked

the Parthian capital Ctesiphon and retook Mesopotamia for Rome.

He was naturally suspicious of the Praetorian Guard … and replaced

individuals with his own supporters to cover for him while he was away

fighting Rome's enemies. However he let his cousin Plautianus

take on too much authority in the Guard – and had him put to death

(205). Septimius Severus (193-211).

The Roman general Septimus Severus fought his way to power by having

his army defeat the armies of other Roman generals contending for the

position as Roman emperor. He then took on the Parthians, sacked

the Parthian capital Ctesiphon and retook Mesopotamia for Rome.

He was naturally suspicious of the Praetorian Guard … and replaced

individuals with his own supporters to cover for him while he was away

fighting Rome's enemies. However he let his cousin Plautianus

take on too much authority in the Guard – and had him put to death

(205).

Severus ended his days personally directing military operations against

Rome's tribal enemies who were constantly threatening Rome's

borderlands. In 208 he traveled to Britain in order to extend

Roman rule even to northern Scotland. In the process his troops

slaughtered countless Scottish Celts …. but he also lost 50,000 of his

own men. In late 210 he became ill while still in Britain …

and died early the following year.

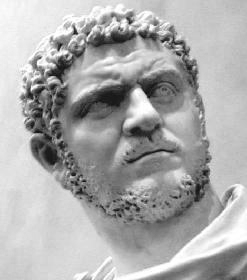

Caracalla (211-217).

Severus's sons Caracalla and Geta succeeded him, though Caracalla

immediately murdered his brother. Then when a satire about his

murder of his brother was produced in Alexandria, Caracalla took

revenge by sending troops to Alexandria to loot and slaughter (over

20,000 Alexandrians killed) … earning Caracalla the reputation as one

of Rome's cruelest emperors. Caracalla (211-217).

Severus's sons Caracalla and Geta succeeded him, though Caracalla

immediately murdered his brother. Then when a satire about his

murder of his brother was produced in Alexandria, Caracalla took

revenge by sending troops to Alexandria to loot and slaughter (over

20,000 Alexandrians killed) … earning Caracalla the reputation as one

of Rome's cruelest emperors.

He treated his army lavishly – understanding the importance of keeping

happy this institution which he both admired and feared deeply.

He also created the last of the great architectural wonders of Rome: a

giant bath that could accommodate over 2,000 at a time (named,

appropriately, the Baths of Caracalla). He was busy during much

of his reign defending Rome's borders against the Germanic Alamanni at

the Rhine frontier. He was, in fact, on his way to renew the war

with Parthia in 217 when he was assassinated by a member of the

Praetorian Guard.

Macrinus (217-218) and Elagabalus (218-222).

The two emperors that followed Caracalla were put in place by the

Praetorian Guard (Macrinus was actually its Prefect) and also brought

down by the same organization. Elagabalus turned out to be a

disappointment (but only 14 when put in his position as emperor)

because of his crude sexual adventures … which led to his assassination.

Alexander Severus (222-235).

Elagabalus's cousin Alexander too was only 14 when he ascended the

throne. In fact it was his mother, Julia Mamaea, who was the real

power behind the throne. In general, his reign was a stable one

for Rome. He did what he could to put Rome back on something of a

moral-legal basis, he attempted to place Rome's governmental structures

on a more rational footing, and he strengthened the economy by cutting

back on governmental extravagance, lowering taxes, improving the

quality of Roman coinage, placing controls on interest rates, etc. Alexander Severus (222-235).

Elagabalus's cousin Alexander too was only 14 when he ascended the

throne. In fact it was his mother, Julia Mamaea, who was the real

power behind the throne. In general, his reign was a stable one

for Rome. He did what he could to put Rome back on something of a

moral-legal basis, he attempted to place Rome's governmental structures

on a more rational footing, and he strengthened the economy by cutting

back on governmental extravagance, lowering taxes, improving the

quality of Roman coinage, placing controls on interest rates, etc.

His problems on the Roman frontier would however make his rule deeply

troubled. A new Parthian dynasty, the Sassanids, had extended

Persian control deep into Roman territory in the eastern reaches of the

Roman empire. When Alexander marched his army out to meet the

Sassanids in 232, the results were something of a standoff for both

sides.

Sassanid kings Ardashir (224-240) and Shapur (240-270)

Two

years later Alexander led his armies out to expel the German armies

that had crossed the Rhine and had overrun eastern Gaul. He

crossed into Germany – and then offered to pay tribute to the Germans

rather than fight them to resolve the issue. The soldiers were

incensed – and plotted his removal and replacement by a soldier popular

among the troops. In 235 Alexander and his mother were both

murdered in a mutiny of his troops.

Fifty years of imperial turmoil (235-285)

The rapid turnover of Emperors.

The assassination of Alexander marked the beginning of a long period of

political, economic and social chaos in which emperors rose and fell in

rapid succession – frequently because they were murdered by the

Praetorian Guard as these "emperor-makers" shifted their loyalties from

one imperial candidate to another (as many as 25 emperors during this

period, depending on how one counts the numerous pretenders to

power). Unfortunately for Rome, generals were more interested in

fighting each other for the title of emperor than in offering battle to

the many tribal peoples who began to cross the Rhine and Danube in

raids into Roman territory. Meanwhile the Sassanids, taking

advantage of this chaos within the higher reaches of Roman power,

extended Persian control into Mesopotamia.

Military decline.

At the same time, the military needs and military expense of the Roman

Empire quickly became almost limitless. After a while there were

no more rich neighbors for Rome to plunder (they left the Germans alone

on the opposite side of their borders because the primitive Germans had

nothing to offer Rome economically). Thus the Empire had to rely

on the resources of its own people to pay for its ongoing and

extravagant military ventures. Mercenaries hired from Rome's

former (or even continuing) enemies replaced the patriotic free

citizen-soldier of Rome, the latter, impoverished from too great a

demand for his increasingly lengthy term of military service,

inevitably falling into terrible poverty. Soon the city's slums

were filled with the once free citizen-soldier and his family.

And so it was that the Empire lost touch with what it once was.

Economic decline.

Direct barter in goods and services (a terribly cumbersome way to do

business) became the accepted means of economic exchange as Roman

coinage became increasingly debased by emperors, who used cheap metals

to pay their soldiers the tribute or financial reward that the soldiers

expected when they threw their support behind a new imperial

candidate. With the military no longer doing its job in

protecting the empire, roads became unsafe – and thus shipping and

trading declined dramatically. Thus also Roman farms ceased being

commercial enterprises – and instead became local enterprises (manorial

estates) producing only for their own immediate needs. Towns were

forced to erect walls and look to themselves for their own

protection. And as farms and towns developed this local,

self-sufficient status, they were less inclined to give significant tax

support to a Roman authority that was increasingly removed from the

world that concerned them.

Distress in the countryside.

Life for the Roman commoners became so difficult during this period

that they were forced to escape the cities for the countryside in order

to find enough to feed themselves and their families – offering owners

of these countryside estates in exchange for their personal survival a

rather permanent servant status, a status that was transferred to their

descendants as well (the beginning of serfdom). Also many small

farmers were just as unable to provide for themselves and thus too fell

into legal bondage to the more successful large-scale farmers in order

to survive.

Buying popular support of the Empire.

The Roman government itself attempted to buy the support of the people

for this decaying system through what was termed by the ancient Roman

poet Juvenal: “bread and circuses” (or bread and games). In a

piece of sharp satire about the state or condition of Rome, Juvenal

commented that the Romans no longer had any interest in defending the

integrity of Rome itself. They had abandoned the older

generations of Romans' noble interest in their public duties, in their

civil and military service to Rome. Instead the people now

anxiously set their hope on just two things: bread and circuses (wheat

distributions and chariot races, gladiatorial contests and an

occasional feeding of Christians to the lions) ... very expensive

entitlements (and huge drain on the public treasury) that the Roman

authorities had accorded the people in order to keep them subdued.

For a vast empire, undergoing obvious moral decay after about 200 AD,

such crass payoffs were not enough. Rome and the Romans were

suffering from a deep moral emptiness that could not be filled with

bread and circuses.

Moral confusion.

Rome was relatively tolerant of the social and cultural 'pluralism'

within its borders – as long as everyone showed due respect to Roman

authorities and their gods. When the Roman emperors themselves

posed as gods this all became quite curious. But for the most

part everyone was willing to play along with the Roman thing.

Morally and ethically, Rome didn't reach deeply into the private hearts

of its subjects. That belonged to their local gods and religious

traditions.

Given

Rome's obvious lack of moral-spiritual focus at this point, a number of

exotic (foreign) religions began to enter vigorously the Empire from

the East – with loftier ideals than the old Roman pantheon of humanlike

gods and goddesses. Mithraism from Persia, with its severe

good/evil dualism, offered its services for a while as the moral

underpinning of an Empire seeing evil swallow up good everywhere.

It was especially very popular within the Roman legions, where life was

either do or die. Also mystery cults from Syria, Babylon and

Egypt were becoming quite popular – though they had no well-organized

advocacy group. Then too the practitioners of Judaism were

numerous in the Empire … and Judaism was opening up its ranks to

newcomers – though it never really developed a full zeal for bringing

the whole of Rome into its ranks.

The heroic Christian witness.

Christianity had no such hesitations, being quite evangelical. At first

it appealed mostly to the poor and helpless who had flocked to the

Roman cities in the desperate hope of finding some remedy to their

plight. In Christianity these Romans found not only comfort, but

an incredible degree of heroic dignity – especially in the face of the

numerous rounds of persecutions that the emperors inflicted on the

members of this strange (very un-Roman) Eastern sect when its members

refused to acknowledge the emperors as gods.

But this persecution seemed only to present Christianity in an ever

more heroic or glorious light to the other Romans watching this

murderous persecution. The bravery of the Christians in the face

of certain death began to move sympathetically the crowds that gathered

to watch these horrifying events. Eventually Christianity's

obvious moral and spiritual strengths were beginning to attract the

interest of even nobler Romans ... which drew even greater wrath from

emperors who saw the old Roman pagan order now coming under serious

challenge from Christianity.

Political fragmentation.

This loss of Roman civic spirit was so pronounced that at one point

(258-274) the Roman empire broke into three separate empires: the

Gallic Empire in the West (Britain, Gaul and Spain), the Palmyrene

Empire in the East (Egypt, Palestine, Syria) – with what was left as

"the Roman Empire" somewhere in between.

Attempts at reform

There were however some notable emperors during this period, who attempted to bring Rome back to order.

Decius (249-251),

though his reign was short, left a major mark on Rome in his efforts to

purge Rome of all but its original state religion (the Christians

suffering greatly as a result) and in his efforts to expel the recently

arrived Goths (which resulted unfortunately in his army's destruction

and his own death in battle).

Valerian (253-260),

though he ruled longer, faced one disaster after another: the Goths who

were pillaging Asia Minor, a plague which broke out within his troops,

and finally his defeat and (presumably) execution by the Sassanids in

his struggle to drive them from Rome's eastern provinces.

Also his reign marked another period of intense persecution of

Christians – many of whom were well-placed socially and politically.

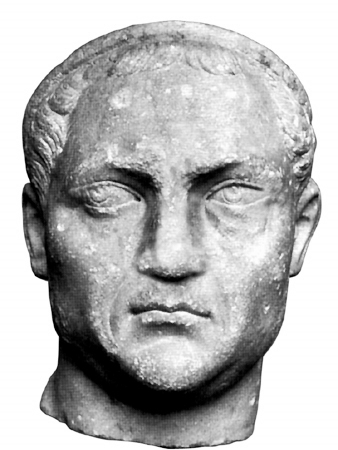

Aurelian (270-275)

was able in 274 to defeat the Empress Zenobia and restore to Rome the

territory she had ruled as the Palmyrene Empire – and in the same year

to bring the Gallic Empire back under Roman authority. But he too

was assassinated by the Praetorian Guard.

Aurelian

|

The Empire divided (258-274)

Valerian bows to his conqueror, Shapur - 260

Valerian bows to his conqueror, Shapur - 260

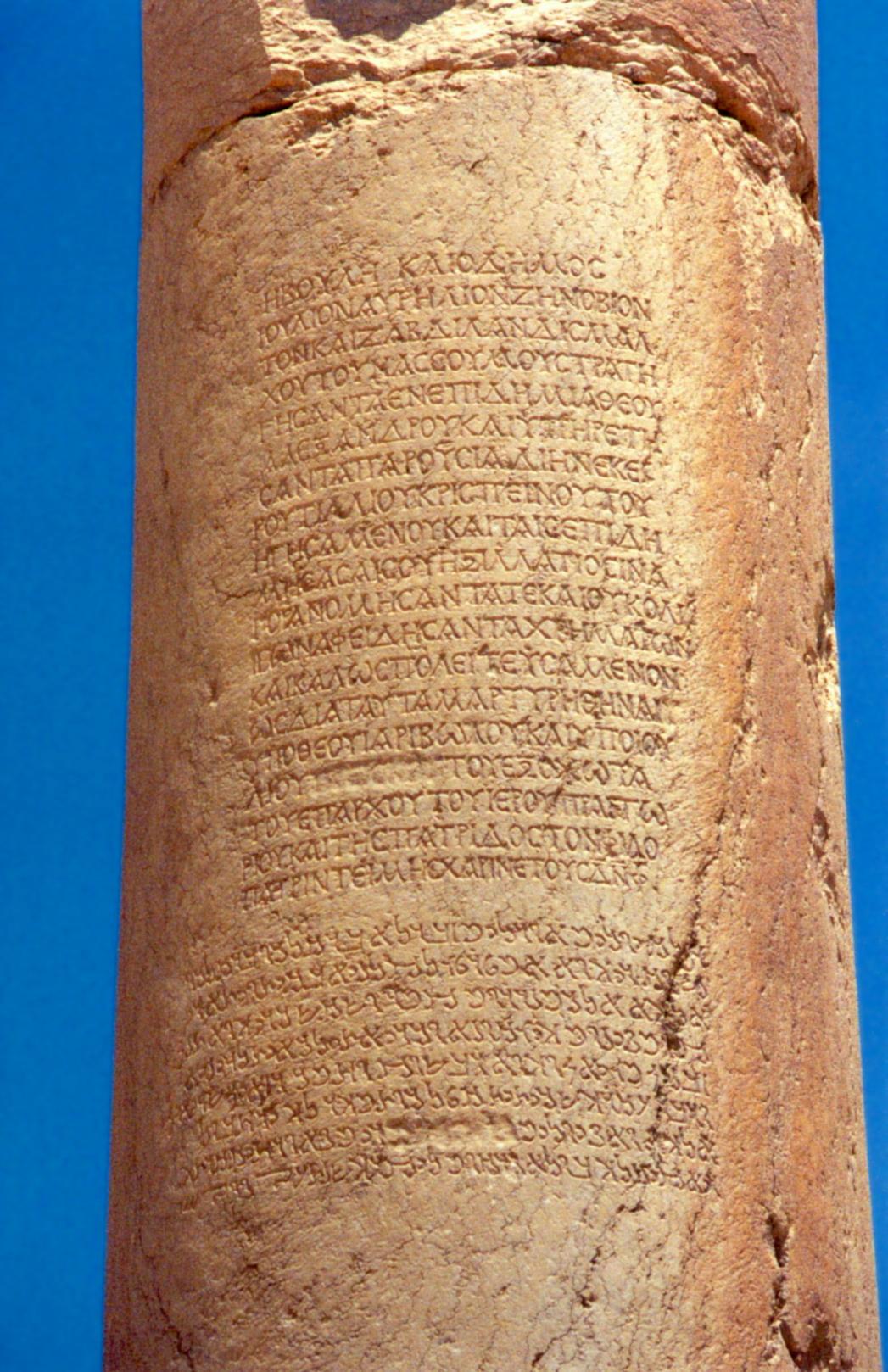

Temple of Bel complex in

the background and the Agora on left center in Palmyra, Syria

In 2017 this was mostly destroyed by Muslim fanatics belonging to the Islamic State

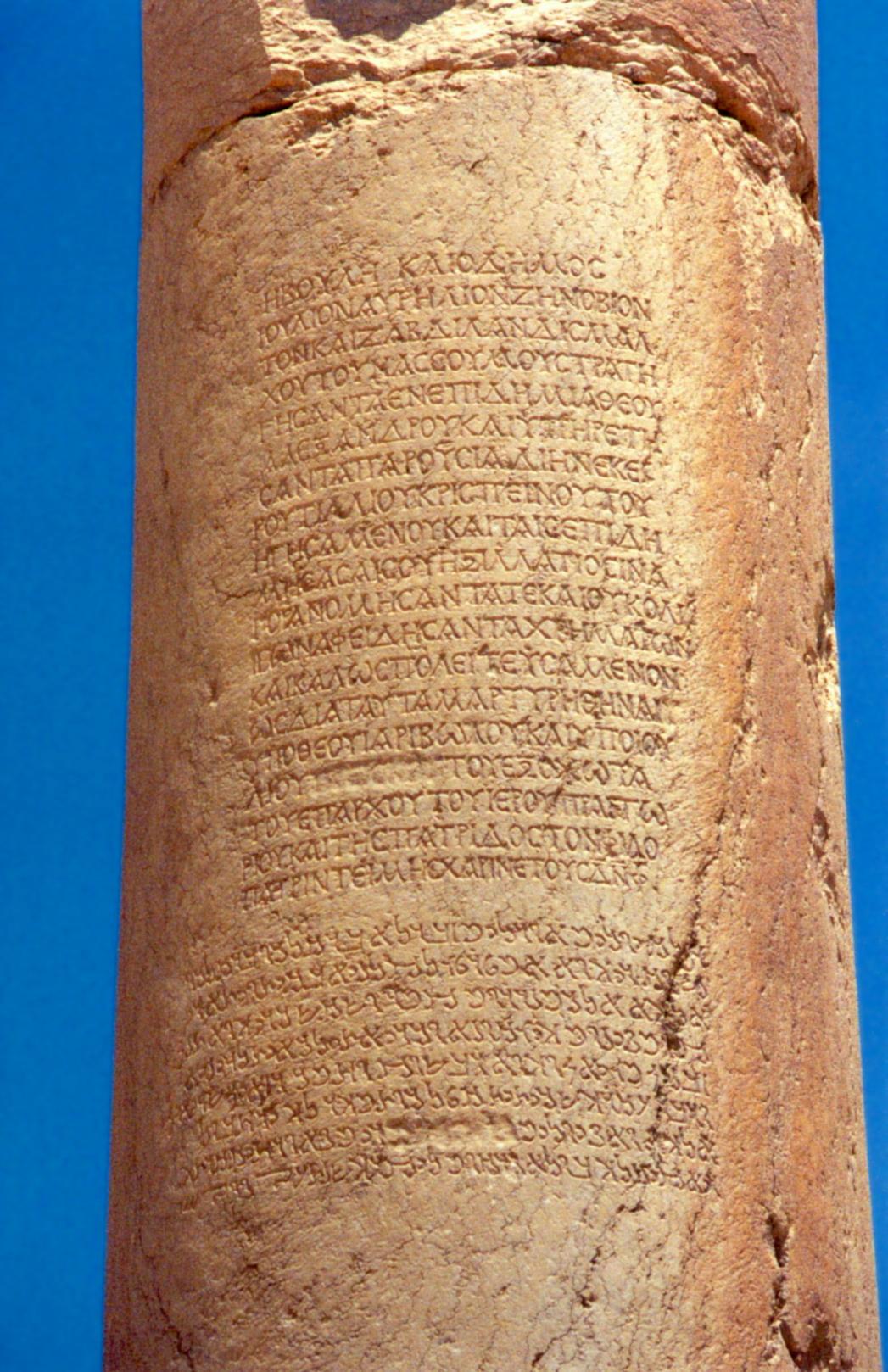

Inscription in Greek and

Aramaic in honour of Julius Aurelius Zenobius,

the father of Queen Zenobia,

at Palmyra

DIOCLETIAN

AND THE TETRARCHY (285-305) |

We

conclude our survey of imperial Rome with Diocletian, a reformer who

attempted to bring this sorry period of Rome to an end. But the

irony is that in his dedicated efforts to restore Rome to some kind of

original purity he succeeded very unintendedly in closing out the age

of Classical Rome and setting up instead Rome's transition into

Christendom (our next section).

The division of the Empire into eastern and western halves and the "Tetrarchy" ("rule of four").

Diocletian was another non-Senatorial figure (born of Dalmatian

commoners) who simply worked his way up the ranks of the Roman legions

to his position of dominance. Aware of the difficulty of one man

giving effective governance to the whole of the Empire, soon after his

acclaim as emperor by Rome's troops in 285 Diocletian recognized fellow

soldier Maximian as co-emperor, with he himself serving as emperor or

"Augustus" over the eastern half of the Empire and Maximian serving as

Augustus over the western half. Then in 293 Galerius and

Constantius Chlorus were called into service as "Caesars" or assistants

(and successors) to the co-emperors, Galerius serving under Diocletian

and Constantius Chlorus serving under Maximian. The division of the Empire into eastern and western halves and the "Tetrarchy" ("rule of four").

Diocletian was another non-Senatorial figure (born of Dalmatian

commoners) who simply worked his way up the ranks of the Roman legions

to his position of dominance. Aware of the difficulty of one man

giving effective governance to the whole of the Empire, soon after his

acclaim as emperor by Rome's troops in 285 Diocletian recognized fellow

soldier Maximian as co-emperor, with he himself serving as emperor or

"Augustus" over the eastern half of the Empire and Maximian serving as

Augustus over the western half. Then in 293 Galerius and

Constantius Chlorus were called into service as "Caesars" or assistants

(and successors) to the co-emperors, Galerius serving under Diocletian

and Constantius Chlorus serving under Maximian.

The

Empire at that point had four rulers, each given different portions of

the Empire to rule. Unfortunately, when it came to fill vacant

positions, this formula proved to be as confusing as Roman politics

ever had been.

The old city of Rome's loss of status.

Not surprisingly, during Diocletian's tenure as Augustus or emperor,

the city of Rome itself (and the Senate) suffered politically … and

socially. Diocletian tended to avoid Rome, preferring to use

Milan or Ravenna as a base of operations when in Italy.

Furthermore, Diocletian's taking for himself the assignment of the

eastern half of the Empire was a clear sign that the political center

of the Empire was also shifting eastward from Italy to the Eastern

Mediterranean.

Religious persecution.

Foreign-born himself, Diocletian compensated by being "super-Roman" …

detesting any foreign intrusions, whether military or cultural, into

Roman life. He also hoped that religious uniformity within the

Empire might further buttress its political unity. Thus both

Diocletian and his assistant or Caesar Galerius took increasingly

hostile attitudes toward a number of popular eastern religions which

were spreading rapidly in the Empire. This became particularly

the case when the traditional temple priests claimed that they were

losing their powers due to the growing influence of these alien

religions, at first most notably Manichaeism.

This was a religion originated by the prophet Mani in the second half

of the 200s, who claimed to be a prophetic successor to Jesus … and the

prophets before him. Manichaeism blended gnostic Christianity

with elements of Persian or Zoroastrian light-dark, good-evil dualism.7

Diocletian detested Manichaeism intensely because of its Sassanid or

Persian connections – because Persia was Rome's main enemy at the time.

Consequently, he began persecutions of the Manichaean faith in the

Eastern Roman Empire in 302, seizing Manichaean property and executing

or enslaving the members of this religion.

Intense Christian persecution.

But he then turned on the Christians. His persecutions would turn

out to be the worst by far that the Christians were ever to experience.

In early 303 he ordered the destruction of all churches and the end to

Christian worship anywhere in the Empire. At the initiative of

his assistant Galerius, Christians were ordered to be dismissed from

the Roman legions. The similar principle was applied to the Roman

bureaucracy. And Christian freedmen (former slaves) were reduced

back into slavery.

This was followed by ever harsher measures: execution by sword or fiery

stake – left mostly to the discretion of local officials, some who were

rigorous in their attempt to eradicate the faith by whatever means

necessary … others less rigorous. For instance, Maximian's

assistant or Caesar Constantius ignored Diocletian's orders in his

western territory of Britain and Gaul.

In 304 Diocletian issued another edict which commanded all Christians

to be brought to a public place and offered the option of sacrificing

to the Roman gods – or facing execution.

This was a very serious problem for Rome itself because at this point

approximately one in every ten Romans was some kind of a Christian.

Pacifying the Empire.

Meanwhile tribal hostilities in the North, rebellion in the East

(Egypt) and a renewed war with Sassanid Persia kept the four rulers

very busy. With respect to the tribal hostilities, Diocletian was

able to strengthen Roman fortifications along the Danube River –

bringing both peace along that front, but also a heavy increase in the

tax burden on Rome. With respect to rebellion in Egypt,

Diocletian was successful in 298 not only in restoring control there

but also in placing a tighter Roman grip over the region. With respect

to the Sassanids, Diocletian was successful in 299 in forcing Persian

recognition of the restoration to Rome of most of Mesopotamia and

Armenia.

Problems of succession.

Then, probably much to everyone's surprise, in 305 both Diocletian and

Maximian stepped down from power, allowing their assistants, Galerius

and Constantius to step up from their positions as Caesars to the full

positions as Augustuses or Emperors. But this now merely opened

the question as to who now was to take the positions as supporting

Caesars. The rivalry became intense.

Thus with so many would-be Caesars contesting each other, in 308

Augustus Galerius and the retired Diocletian and Maximian called a

conference to try to work out a settlement so as to bring things back

to balance. But the effort merely produced even more imperial

claimants (seven) when new appointments were challenged by those left

out of the deal. Thus military chaos would continue to reign over the

Empire.

The Christian persecutions continue.

Meanwhile, the persecutions continued under Galerius, and supporting

Caesar, Maximinus (actually his nephew) – the latter being particularly

a strong enforcer of Christian persecution. Such persecution

continued until 311 when Galerius, now on his deathbed, issued a decree

officially ending the persecutions. However Maximinus –

self-elevated to full status as Eastern Augustus in 310 – soon ignored

the decree and continued the persecutions in his eastern realm … at

least until shortly before his own death in 313.

Constantine versus Maxentius.

At the same time, with the death of Galerius, former (uneasy) allies

Constantine and Maxentius now found themselves facing each other in the

matter of assuming supreme imperial powers in the West as its Augustus

… a position already held by Licinius (resulting from the 308

agreement).

How this conflict would play out would have tremendous implications for

the way Western civilization would develop from this point forward.

7The

Manichaeans professed the old Persian idea of a dualistic divinity: 1)

the creator/god of this physical world is Evil; 2) the god of Good is

master over the spiritual world. The two are in struggle with

each other for supremacy over life.

IMPERIAL

ROME — IN PICTURES |

The Roman

Forum

Miles Hodges

The Roman

Forum

Miles Hodges

The Roman

Forum

Miles Hodges

The Approach to the Coliseum

from the Roman Forum

Miles Hodges

The Coliseum, Rome – (AD

70-80)

Miles Hodges

The interior of the

Coliseum

Miles Hodges

The interior of the

Coliseum

Miles Hodges

Hadrian's Tomb

Miles Hodges

Interior of the Pantheon,

Rome – painting by Giovanni Paolo Panini (early 1700s)

Erected in 17 BC; destroyed

by fire in AD 80; reconstructed by Hadrian in AD 123

Trajan's column (and detail)

— (AD 107-113) marble

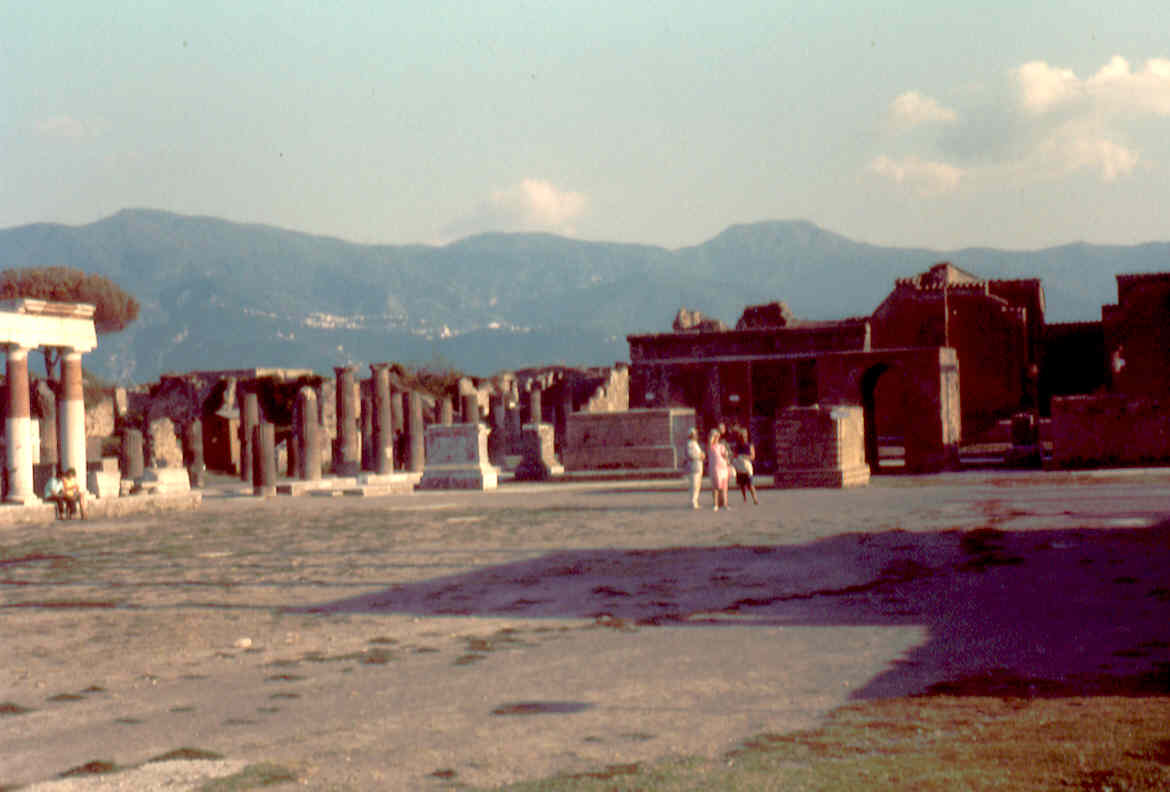

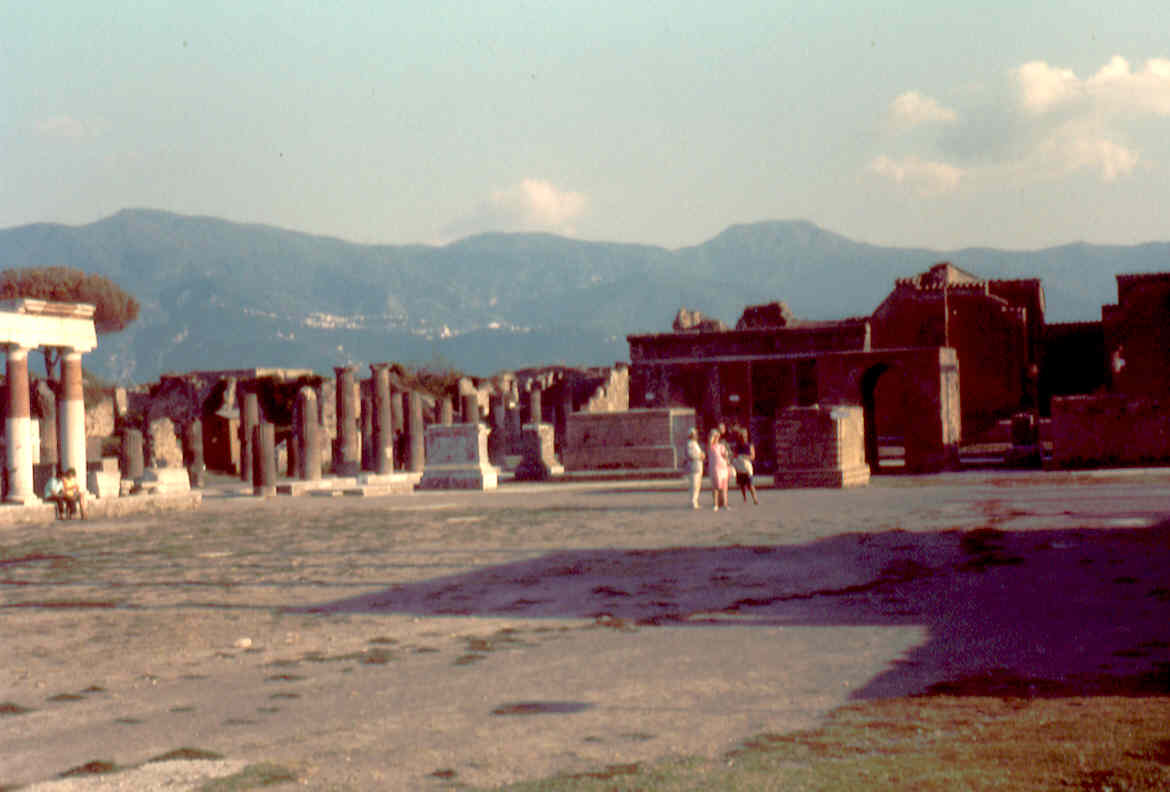

Pompeii: A town frozen in time

Pompeii

Miles Hodges

Me ... at the entrance to

the Temple of Apollo – Pompeii

Miles Hodges

Pompeii

Miles Hodges

Pompeii

Miles Hodges

Pompeii

Miles Hodges

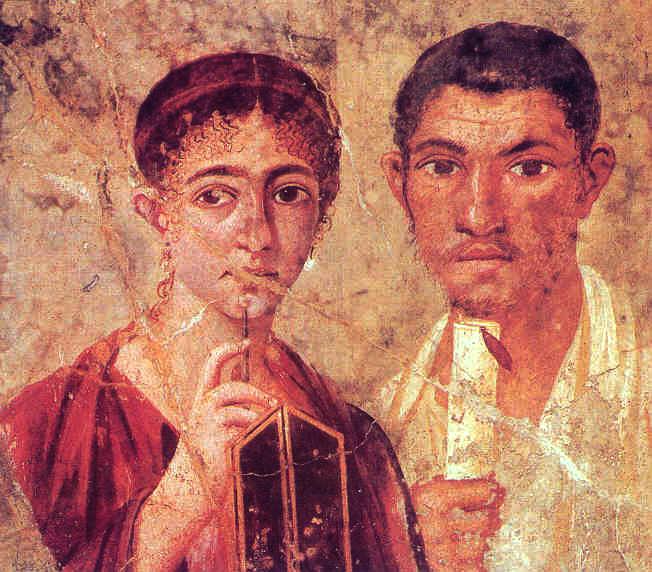

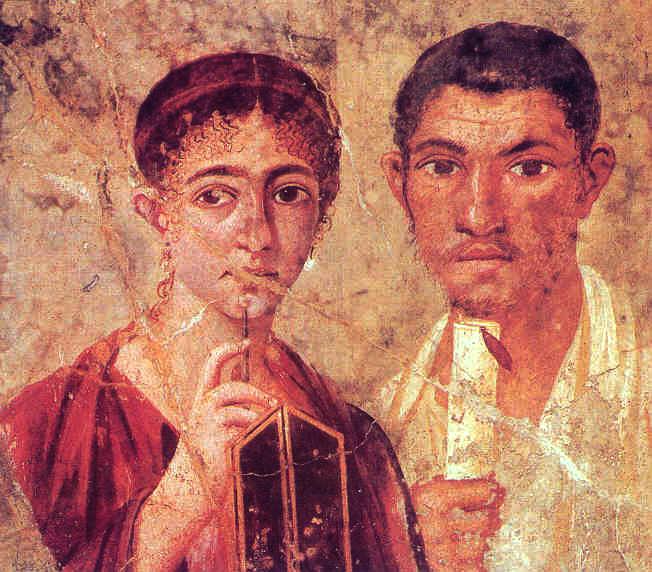

Pompeii – wealthy,

educated

husband and wife ... from the house of Julia Felix

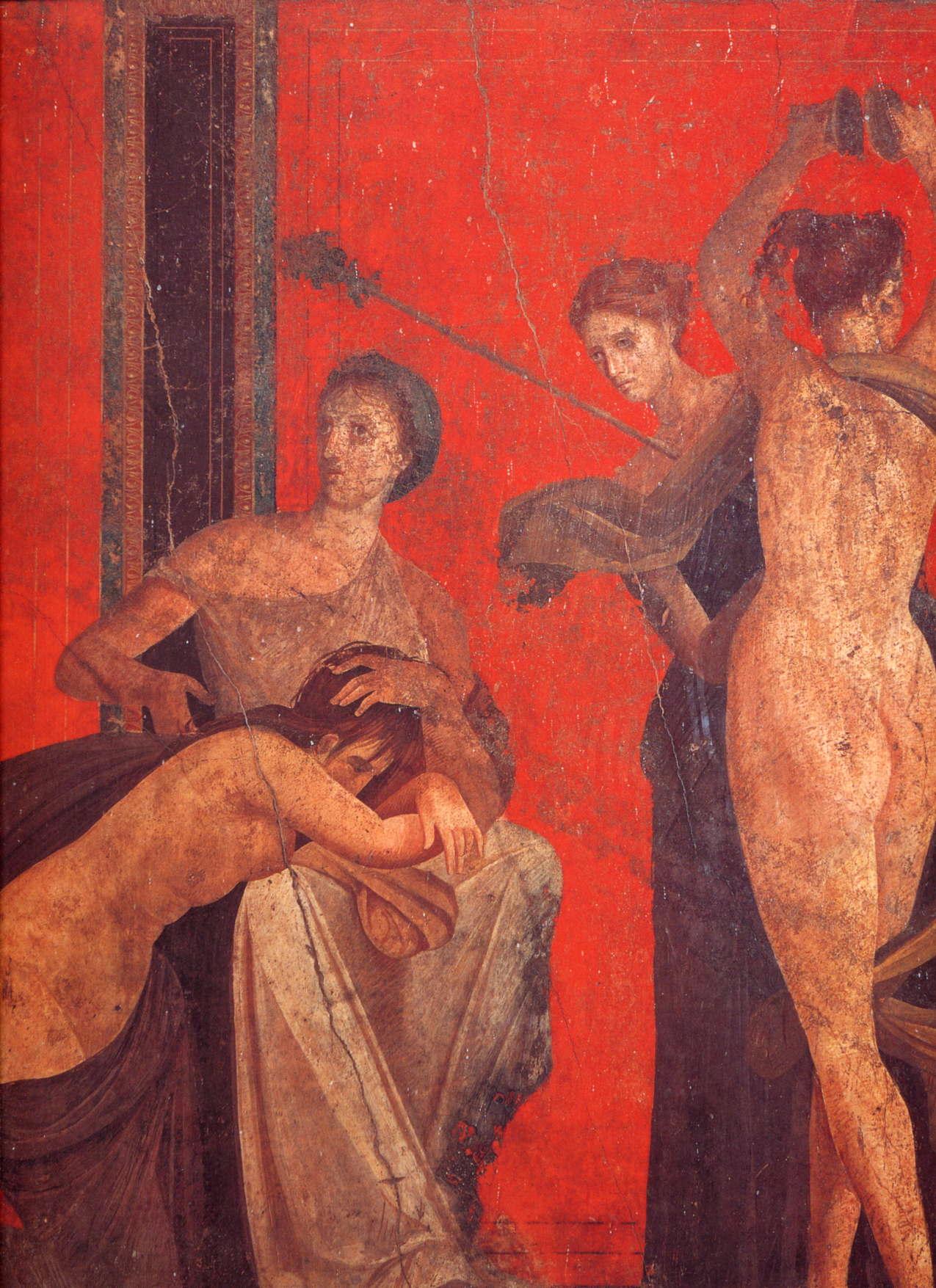

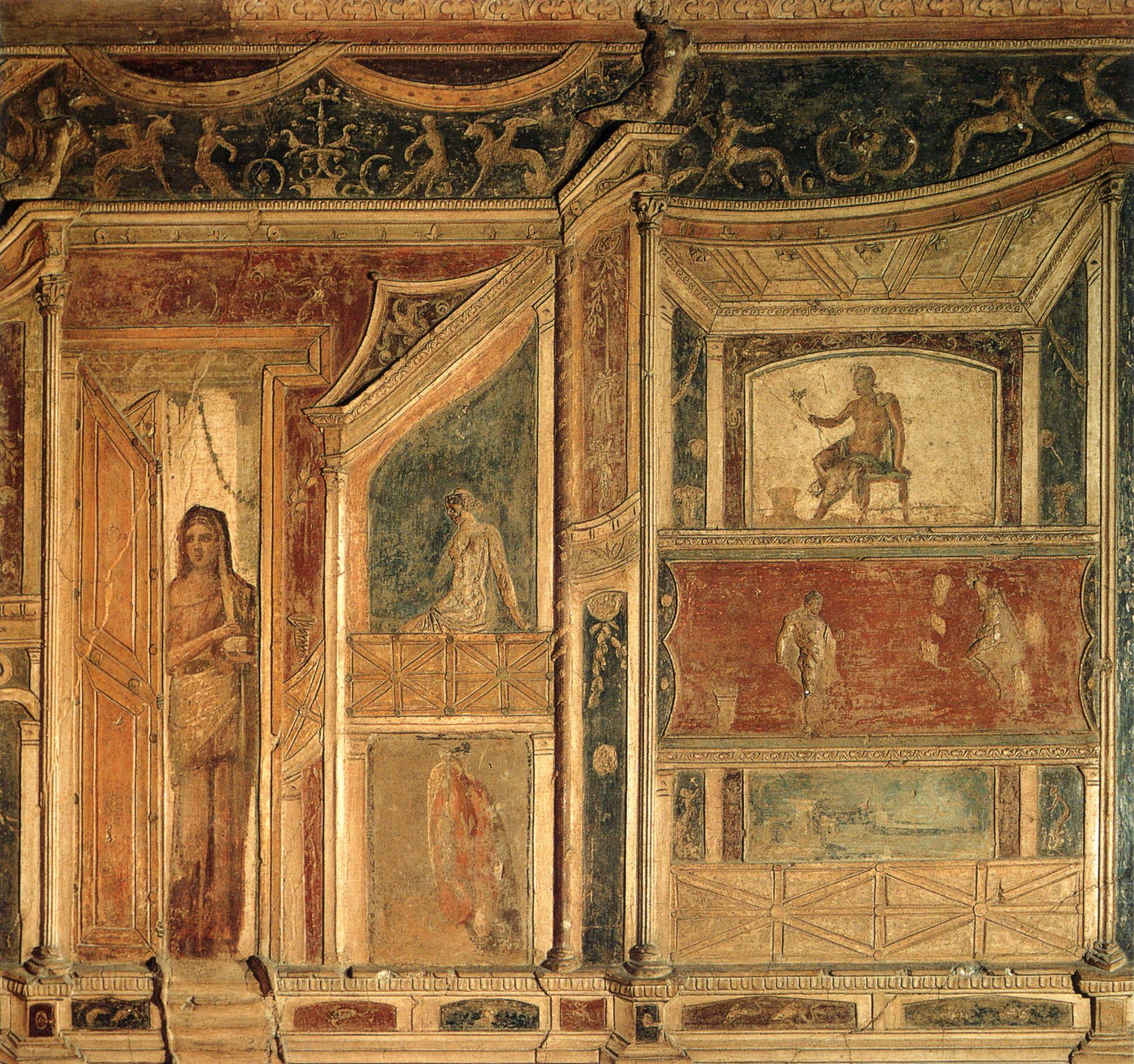

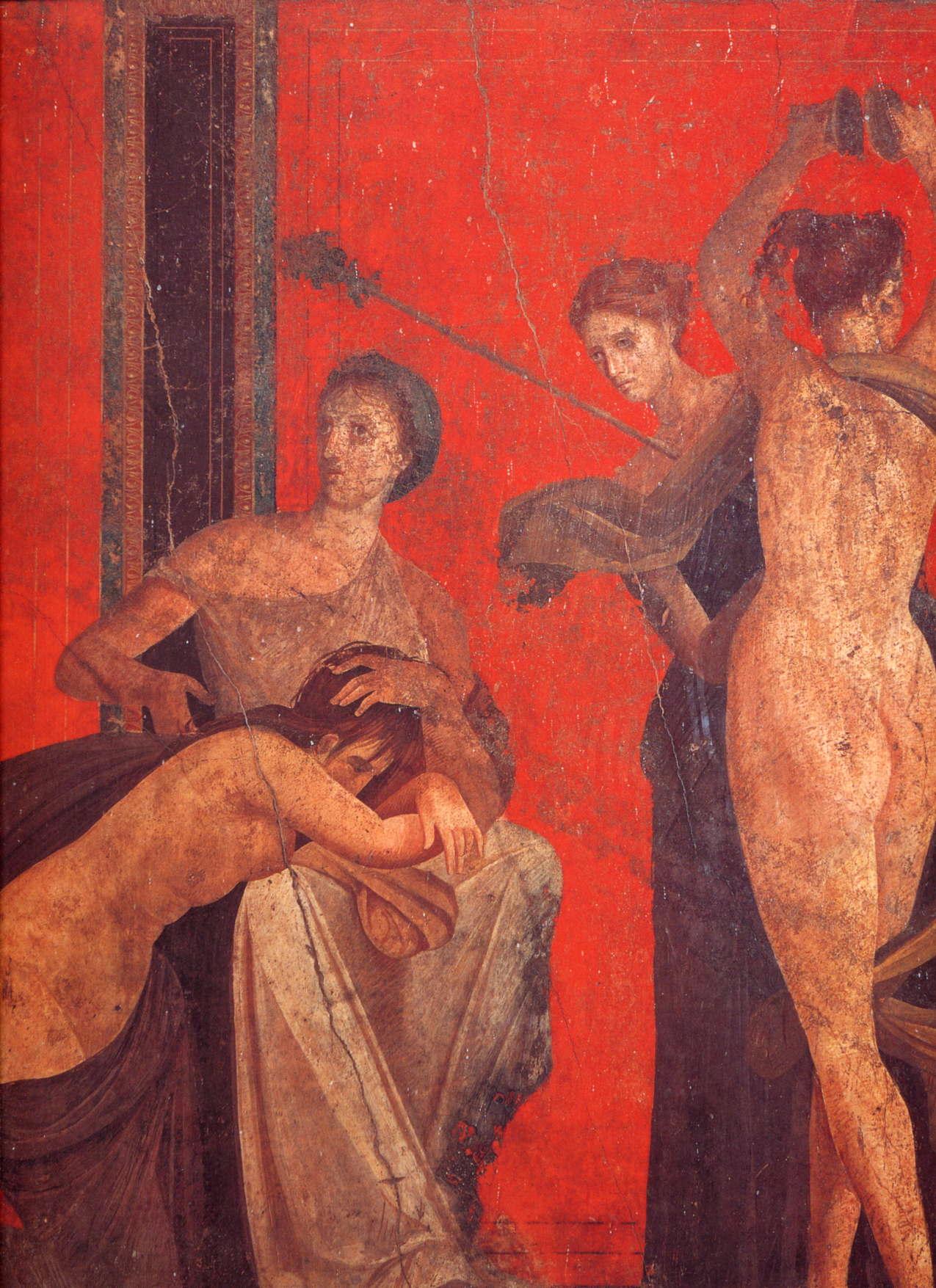

Dionysiac Mystery Frieze – Detail of Second Style wall painting (c. 50 BC)

Pompeii, Villa of the

Mysteries

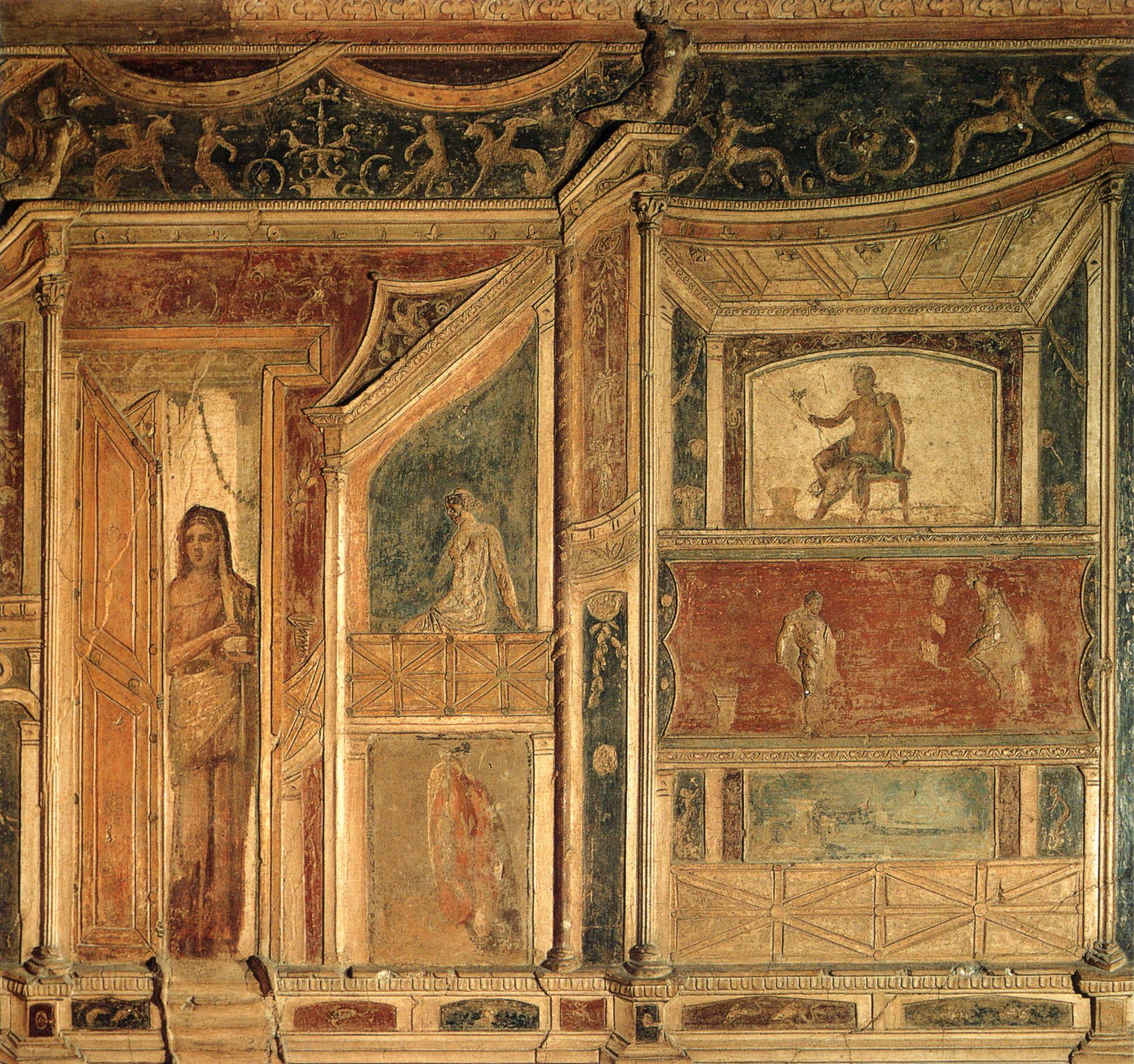

Boscoreale (50 BC)

fresco

Naples, Museo

Archeologico

Boscoreale - Woman playing

a kithara (50 BC) fresco

New York, The Metropolitan

Museum of Art

The further reaches of the Roman Empire

Heading south from

Rome on

the Appian Way (Via Appia)

Miles Hodges

The Appian Way

Miles Hodges Corinth (in Romanized Greece)

Corinth - with

its acropolis in the distance

Miles Hodges

The Lechaion

Road

Miles Hodges

The Agora of

Corinth

Miles Hodges

The Apollo

Temple in Corinth

Miles Hodges

The Apollo

Temple in Corinth

Miles Hodges

A Roman Aqueduct (the Pont

du Gard) at Nimes, France, built in the 1st century AD

Aqueduct of Segovia, Spain

(AD 117-134)

The Library of

Celsus - Ephesus (modern Turkey)

Roman Britain

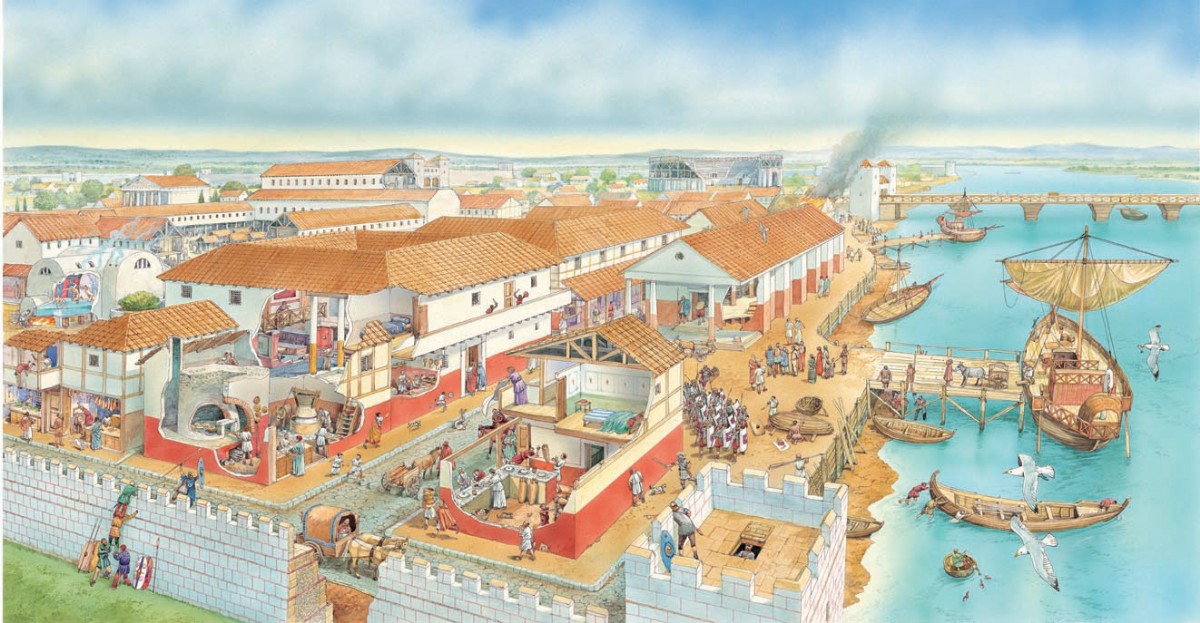

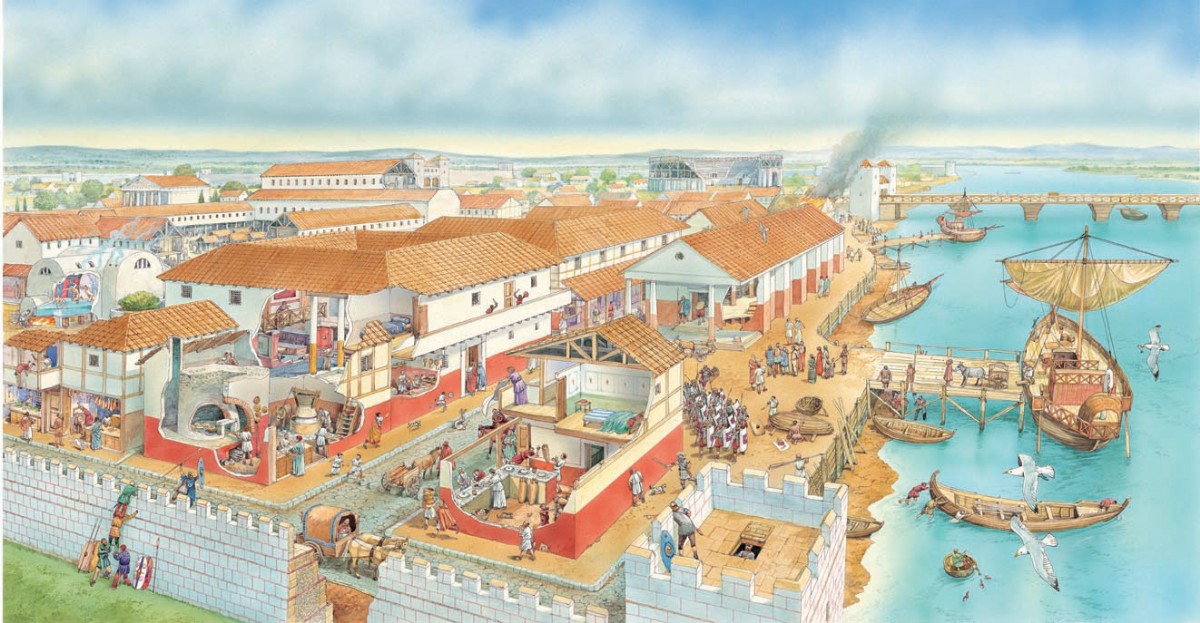

Hadrian's Wall ... designed to hold off the Picts and Scots from Roman Britain

Typical fortified urban life in Roman Britain

Map of Roman Britain

Encyclopedia Britannica

Go on to the next section: The Israelites/Jews

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | | | |

The birth of imperial Rome

The birth of imperial Rome

The height of the Roman Imperium

The height of the Roman Imperium

The intellectual culture of the Roman

The intellectual culture of the Roman The decline of the Roman Empire

The decline of the Roman Empire

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (285-305)

Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (285-305)