10. ENLIGHTENMENT ... AND REVOLUTION

"ENLIGHTENMENT" IN AMERICA AND EUROPE

"ENLIGHTENMENT" IN AMERICA AND EUROPE

A "Great Awakening" religiously ... and

A "Great Awakening" religiously ... andpolitically

However, the cosmological split within

However, the cosmological split within

the West also deepens

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 392-401.

A "GREAT AWAKENING"

RELIGIOUSLY ... AND POLITICALLY |

|

Christianity Under Fire

This all occurred at a time when the Western Christian world was beginning to see itself faced with an issue bigger than even the persistent animosity between Protestantism and Catholicism. What was at issue was the question: is Christianity truly an "inspired" religion – its great Truths "revealed" by God through the prophets, and through Jesus, and subsequently through the saints of the Church? Is Christianity a religion designed to bring people to live in humble submission to the historical or continuing and fully active outworking of God's will? Is Christianity a "way" for those seeking to live on eternally (thus also in the "hereafter") in the company of God? Or is Christianity essentially a moral-ethical program – useful for the orderly behavior of the citizens of this world? Is Jesus to be understood most importantly as the Good Teacher who offers outstanding moral-ethical instruction – and a lofty moral example himself – for the benefit of those choosing to live this life in dignity and with compassion? By the early 1700s the split was obvious – and profound. One the one side of the divide were ranged the "spirituals" or "pietists." On the other side were the "rationalists" or "ethicists." Both claimed to be defending the sole approach to Truth and Order. But their positions were almost mutually exclusive. There was absolutely no common ground that could pull these two "Christian" groups together. America's "Great Awakening" religiously ... and politically

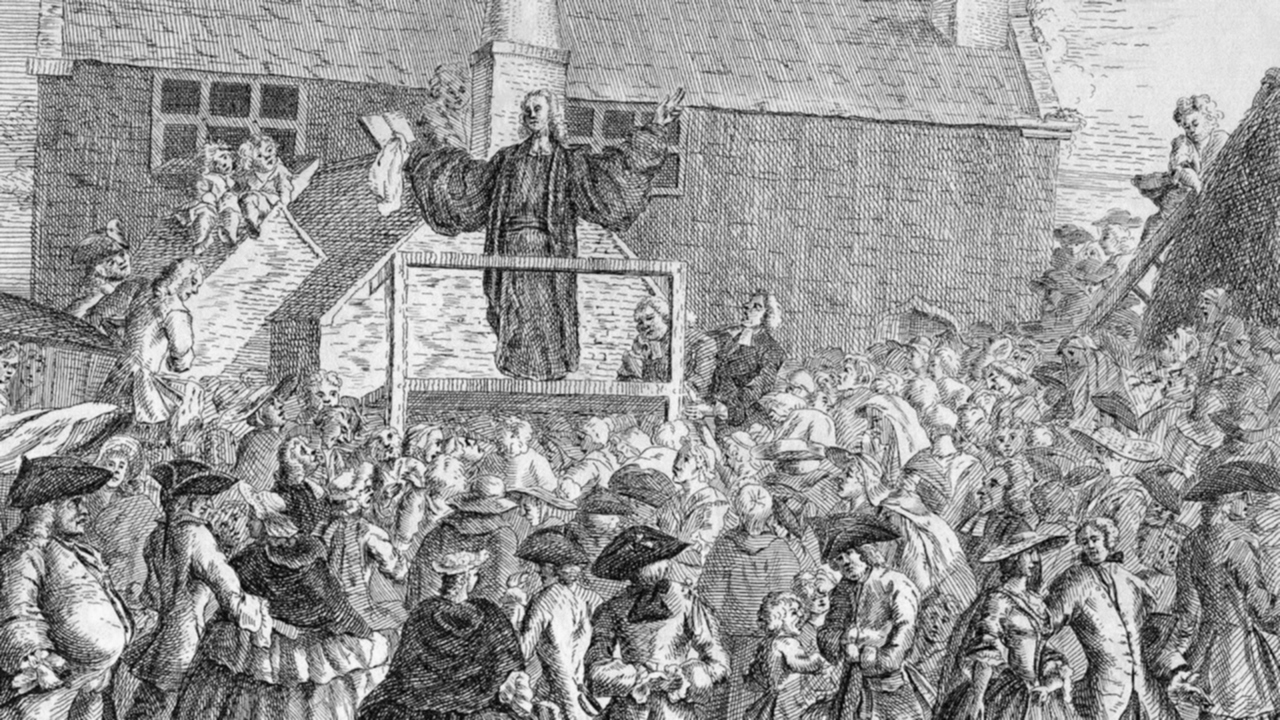

Then, in the late 1730s and early 1740s – just as it appeared that the Christian foundations of early English-America were also about to die out because of a lack of spiritual interest or even cultural support – something mysterious infected the American heart. The "Great Awakening" suddenly broke out upon the American scene ... to restore the warmth of American affection for God and Jesus – and the belief once again in God's total sovereignty in America. Actually the event first broke out in England, as a result of the evangelical ministry of the brothers John (the preacher) and Charles (the musician) Wesley ... and their "Methodist" supporters.1 On a (rather unsuccessful) missionary trip (1736) to the newly established American colony of Georgia, John came into the company of some Moravians – who modeled for him a strongly-grounded Christian faith ... one that would impact Wesley deeply. It inspired John to go about churches in Britain and Ireland – then even the streets and open fields – to call his fellow Englishmen to repentance and spiritual salvation. Thus his "Methodism" spread itself across his English world. Joining him in this effort was fellow Oxford student George Whitefield ... who also had an interest in taking the message to America. He would spend the rest of his life moving back and forth from England to America – preaching wherever he could. But the Americans put forward a number of outstanding evangelists of their own ... who had a huge impact in restoring the Christian faith in their world – for instance, Theodore Freylinghuysen, William and Gilbert Tennent, Jonathan Edwards, David Brainerd, Samuel Davies ... and others. But without a doubt the greatest impact on America came from Whitefield, who repeatedly moved north and south through the colonies, drawing hundreds of thousands to hear his preaching, calling on Americans to repent of their indifference to God and to return to live under his sovereign rule as free and equal followers of Christ.2 The net result of this grand revival was three-fold. It revived the Americans' sense of personal responsibility to serve a higher cause as a covenant people, pledged to live socially to the high standards of the Christian faith. It worked to build in the colonists a collective national spirit as "Americans" – producing an identity well beyond that of being just "Virginians," or "New Yorkers," etc. And it restored among these Americans the understanding that in crossing the great Atlantic Ocean they had cut their ties with an English political system that held millions in servitude to absolutist monarchs ... and that in America, their sole responsibility was to God and neighbor alone. They would defend that notion with their lives if need be. And just such a need there would be ... quite soon.  For more (much more) on America's "Great Awakening" For more (much more) on America's "Great Awakening" 1The term "Methodist" was originally a term of derision used by fellow Oxford University students who mocked the Wesleys and fellow members of their Holy Club for their efforts to develop a more disciplined Christian faith during their studies at Oxford. 2Estimates are that he preached over 18,000 sermons to as many as perhaps ten million people in Britain and America ... until his death in 1770 at age 50.    Theodore

Freylinghuysen

Gilbert Tennent  Jonathan Edwards

George Whitefield |

HOWEVER, THE COSMOLOGICAL SPLIT WITHIN THE WEST ALSO DEEPENS |

|

"Enlightened Despotism"!

Back in the second half of the 1600s (and into the early 1700s), French King Louis XIV had justified his heavy-handed rule along philosophical lines not unlike that which Hobbes had earlier called for: the need of the people to come under an "enlightened" Leviathan, an absolute or "despotic" father-figure who would rule the people with an iron fist for their own best interests. Louis was careful to pay close attention to all the discussions of enlightenment thinking, sponsoring scientific research (especially when it could be beneficial to his military ambitions) and giving the appearance of being an earnest contributor to the new thinking coming out of the emerging scientific age. This was what the ideal of "enlightened despotism" was supposed to be all about. But it came at a great social price to France, leaving that country after his death in 1715 in a state of economic and intellectual dependency on the massive French monarchical system, which it was unlikely that any personality less than Louis XIV's could sustain. Indeed, the French state began to slide into economic disarray shortly after him, leading to the entire collapse of the French state in the late 1780s. The Jesuits

By the time of Louis XIV, the most militant defenders of the "True Faith" (Roman Catholicism, or more particularly the authority of the Pope) – the Jesuits – had lost much of their original spiritual character ... and had become a quite thoroughly political organization. They not only linked themselves with Catholic kings who promised support of the Catholic cause, but they became closely involved in the political intrigue not only aimed against Protestants but also directed to the rise and fall of particular monarchs. They were politically astute – and dangerous to work with. Louis XIV used them to help drive the Huguenots out of France – though he was also cautious with them because of his "Gallican" policy of bringing the church in France directly under his own political supervision ... thus in political contest with the Roman Pope – whom the Jesuits were pledged to serve at all costs. Charles Louis de Montesquieu (1689-1755)

And

since human nature tends over time to like to gather into its own hands

as much power as possible, the best way to guard against this despotic

tendency was to set up a system of laws that separated the powers of

government … particularly through the separation of legislative,

executive, and judicial authority. In doing so, they would check

and balance each other in authority … so that despotic power could not

develop. Jean-Jacques Rousseau undercuts the idea of royal sovereignty

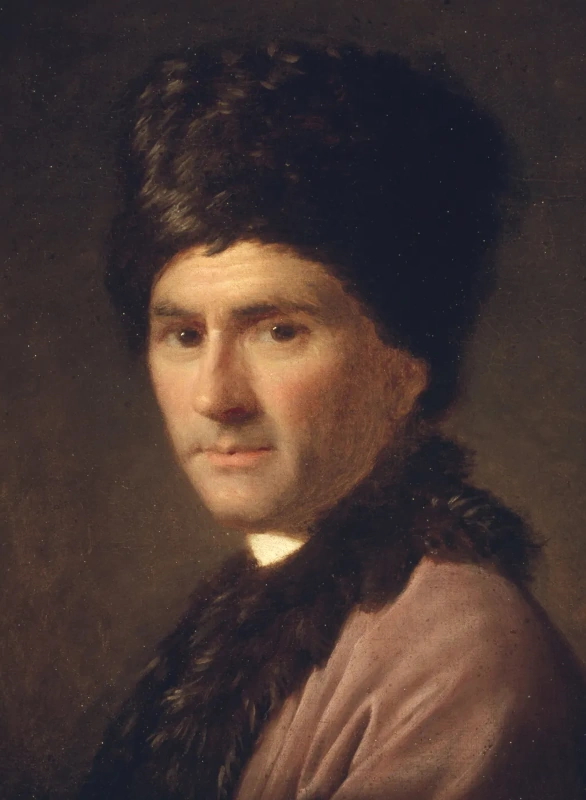

A

key individual coming onto the European political stage a generation

later was the French-cultured Swiss, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778),

whose writings, especially The Social Contract (1762), became quite

popular in France. Rousseau raised the question of political

sovereignty, where it was lodged and how it functioned to best serve

the people. A

key individual coming onto the European political stage a generation

later was the French-cultured Swiss, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778),

whose writings, especially The Social Contract (1762), became quite

popular in France. Rousseau raised the question of political

sovereignty, where it was lodged and how it functioned to best serve

the people.Rousseau claimed that originally man lived in some kind of simple natural state of harmony, without laws or government. But life had evolved over time into a more complex form – civilization – requiring as it developed greater mutual dependence among men for the orderly working of society, and thus also a more complex system of moral instruction or law to guide society. Man accordingly had to give up his total personal sovereignty to come under the protection and nurture of this more complex society. But he was giving it up not to some ruling individual but to the larger idea of the society as a whole, the general will – in particular its laws, which were the clearest expression of a people's general will. The laws, not any particular individuals, were the locus of sovereignty in the truly good society. Unfortunately, ignorance of this good had clouded people's political understanding, causing them to slip into all forms of political tyranny – absolute rule over society by particular individuals such as kings and dukes, which was the general pattern of Rousseau's day. Rousseau's hope was to open men's eyes to the understanding of what was truly right and good about society, that such knowledge would free men to usher in a good or utopian society that was truly the right of everyone to enjoy, not just the privileged few. All the superfluous fluff of decadent civilization – in particular French civilization as it was viewed in his own time – would be simply swept away by the opening of the eyes of the people to the Truth. With the Ancien Régime – the Old Order comprised of the officers of the king and church that dominated all European society in the 1700s – thus swept away, society would be free to create or contract a social system as simple and basic as possible, a social system directed by a set of basic laws that restored to man his fundamental liberties, allowing him to live as close to the original state of nature as possible. The French were strongly impacted by Rousseau's theories – as have been many revolutionary-minded secular philosophers since Rousseau (as well as modern hippies trying to go back to nature in simple communal living). Rousseau's vision of primitive society even found its way into the polite social gatherings or salons of Europe's ruling classes and their intellectual tutors. Thus it was that the future queen Marie Antoinette used to love to play in the Versailles palace gardens with fellow maidens at the French court at being a peasant girl herding her sheep. It was all so quaint, so romantic. The French monarchy was sick, very sick. Reform was needed. But by Rousseau's logic, that reform was going to have to be extensive for the good society to result. The Ancien Régime was going to have to be set aside in its entirety in order to make way for the new. Thus with Rousseau's encouragement, the French political mood was becoming increasingly revolutionary as the political debate in the late 1700s intensified in France. British Pragmatism takes a different path

British Empiricism. Across the channel in the British Isles, the British were of a more practical mindset in their love of hands-on experimentation than their continental cousins, who loved to sit at their desks or gather at polite salons to indulge themselves in the world of pure thought. During the Enlightenment the British were too busy inventing new material technologies – and developing the industries to put those technologies to practical use – to be wasting time speculating about hypothetical realities. They were all, by nature, Empiricists.  David Hume promotes Empiricism.

In the mid-1700s the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) had his own answer

to the Rationalism that infected so much of European society. As

a philosophical empiricist, the widely read and respected Hume found

sufficient Truth for life in simply observing actual behavior, and the

results it produced. Results were to Hume real Truth.

Long-abiding custom (in other words, social rules that actually worked

over the long run) were for Hume the foundations on which to build

human life. David Hume promotes Empiricism.

In the mid-1700s the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) had his own answer

to the Rationalism that infected so much of European society. As

a philosophical empiricist, the widely read and respected Hume found

sufficient Truth for life in simply observing actual behavior, and the

results it produced. Results were to Hume real Truth.

Long-abiding custom (in other words, social rules that actually worked

over the long run) were for Hume the foundations on which to build

human life.Likewise, Hume was most unimpressed by the great intellectual "spins" that philosophers wove around hypothetical behavior in building their great systems of thought. For Hume reality was in the doing, not in the hypothesizing about life. Widely studied, Hume became well-known in his time for his skepticism about speculations about God, or great systems of religious Truth, or the validity of "objective" ethical systems, even the claims of science to have established an explanation of all life in terms of cause and effect. All this was to Hume mere intellectual humbuggery. Hume's impact lived long after him. In fact it was Hume that awakened the great German philosopher Kant from his "intellectual slumber" (as Kant himself put it) and caused Kant to undertake the task of responding to the challenge that Hume had issued to those who would claim to understand human nature, even life itself.  For more on Hume For more on Hume Adam Smith explains capitalism.

In the meantime, the British were very busy inventing new material

technologies, and developing the industries to put those technologies

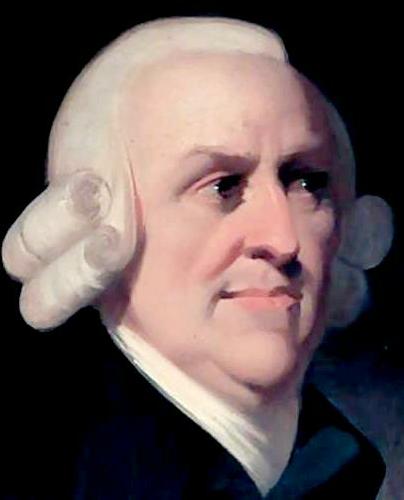

to practical use. Adam Smith explains capitalism.

In the meantime, the British were very busy inventing new material

technologies, and developing the industries to put those technologies

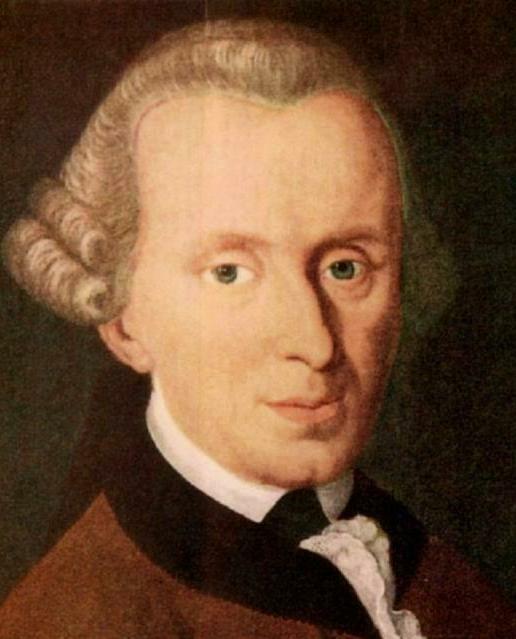

to practical use.Building on this attitude was the fellow Scot, Adam Smith (1723-1790), who in his Wealth of Nations (1776) wrote a compelling explanation of how simply letting the competitive marketplace bring forward the material blessings of life – and the pricing involved for such wealth – would also naturally bring forth human progress. He was much opposed to the idea of forcing on society the designs of utopian social planners, who would soon enough make a mess of things with their well-reasoned schemes. In fact, Smith was strongly opposed to any kind of "intervention" into this market mechanism by the government or any other outside societal institution. To Smith (and all capitalist philosophers since then) this independence of commercial action was the key doctrine of Capitalist philosophy. But at the same time, Smith was highly opposed to market insiders getting together to conspire to set prices through a withholding of goods or services to create an artificial scarcity. He was thus opposed to cartels, monopolies, and unions, of any variety. He also considered the danger of rapid population growth distorting the labor market and driving prices down to subsistence levels. But he felt that economic growth of the whole industrial sector would constantly increase the demand for labor and thus prevent such cruelties from occurring.  Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

was something of a father to German philosophy, setting out, just prior

to the French Revolution, to locate some kind of intellectual bridge

between the powerful philosophies of French Rationalism and British

Empiricism. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

was something of a father to German philosophy, setting out, just prior

to the French Revolution, to locate some kind of intellectual bridge

between the powerful philosophies of French Rationalism and British

Empiricism.Kant agreed with Hume's empiricism, namely that essential to human knowledge is our sense experience – the experience of the seeing, feeling, hearing, etc. of real material objects around us. But he also agreed with the continental Rationalists (most notably Leibniz, whose writings also were a major influence on Kant) that knowledge is also a matter of the exercise of human reason, in particular the use of innate human ideas ("categories") which we are born with and which help us to organize this empirical information. Thus Kant saw himself as closing the intellectual gap between the British Empiricists and the Continental Rationalists. Kant also saw himself as answering Hume's skepticism about ever knowing with any degree of certainty the Truth of transcendent ideas, such as moral laws or ethical principles (not to mention the idea of Heaven itself). In Kant's Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788), he proposed a new moral/ethical "categorical imperative, " one that did not require the existence of God for its validity. It involved an ingenious piece of moral logic: we ought to act in such a way that our act could become accepted as a universal principle of behavior. If it were not able to attain such a universal validity (because, for instance, of an internal contradiction in logic) then that action, by "practical reason, " was obviously not to be pursued. Taking this logic of "practical reason" a step further, he turned to the issue of the existence of God. He agreed with Hume that no rational argument could be given for God's existence – that is, "pure reason" could not build a case for God's existence. But "practical reason" could. Pursuing a traditional line of reason that went back at least as far as Ockham in the early 1300s, Kant claimed that human reason cannot establish the "fact" of God. But in observing the moral instincts of people we can see (through the eyes of faith) that there is some kind of source beyond the mere human will itself that directs life. That higher moral grounding is by definition God. Thus God exists. (This kind of theological reasoning did not impress the Prussian government, which censured his work). Finally, so impressed was Kant that we humans could live in accordance with such higher moral imperatives that in his Perpetual Peace (1795) he laid out a vision for a new world order. Here (despite the Reign of Terror going on in France) begins the utopian idealism that will absorb the thoughts and aspirations of intellectuals for generations to come.  For more on Kant For more on KantJean-Baptiste de Lamarck places the idea of "natural progress"

on a scientific basis  Change

was in the air. A sense that something new, something

revolutionary, was about to break forth seemed to be the understanding

of the times (the latter part of the 1700s). "Progress" was the

new by-word. Change

was in the air. A sense that something new, something

revolutionary, was about to break forth seemed to be the understanding

of the times (the latter part of the 1700s). "Progress" was the

new by-word.Clearly history had always been pointing toward some great new development in life on this planet ... politically, intellectually, morally, even spiritually. Reinforcing this idea was the way the new "science" itself pointed to such "progress" as the inevitable move of all history. Things had long been moving forward in a state of constant progress ... progress that now seemed about to reach its highest achievement. A big step in the early development of the theory of evolution by "natural" development was made by the French botanist, Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (1744-1829). He was concerned about the overwhelming body of empirical "facts" that were being collected by scientific observers – pointing to a need for systematization (in the manner of Linnaeus) and for the construction of theories that would make all this material speak to our sense of understanding in a useful way. Thus he began publishing a number of works of a wide scientific scope, all designed to explain the process of the earth's natural, physical life: Research on the Causes of Principal Physical Facts (1794); System of Invertebrate Animals, or General Table of Classes (1801); Hydrogeology (1802). Most importantly, in his 1809 Zoological Philosophy (which he presented to the French dictator Napoleon) he demonstrated that through chemical influences acting on organisms to create new traits and by the environmental forces shaping these traits through necessary adaptation, organisms had progressed over time. This included humans, in which human learning did not start out with a blank sheet (as per Locke's theory) but was built in part not only on the development of natural biological adaptation but also on the received aspects of learning derived by a person's ancestry. Thus learning could be understood as potentially progressive, evolving from one generation to the next, if carefully engineered with that understanding. But he then went much further ... in theorizing that life, in all its varied form, had evolved historically over the very long run of the earth's history. He conceived this evolution as a step-by-step development of plant and animal life by which ever more evolved forms replaced more primitive forms – as if life had scaled a ladder from lower to higher forms, culminating after eons of earth time in the emergence of human life. He identified the driving force behind this evolution as being that of a dynamic process by which life urges itself forward toward perfection and changes along the way of this process as organs and characteristics are either taken on or dropped on the basis of their usefulness (or lack thereof) to the species in this quest. Giraffes thus developed longer necks and legs because this proved useful to them in reaching the higher vegetation on a tree. There were, of course, many flaws in such bold, far-reaching theorizing. For instance, how such alterations in species form are preserved and passed on to a new generation was not really answered by Lamarck. Ultimately, a lot of his theorizing was overturned later with the development of genetic science. But at the time, the apparent reasonableness of his utilitarian theories gave great impetus to the notion of a "natural" development of life – one that needed no divine intervention to explain its workings. |

Go on to the next section: "Revolution"

Montesquieu,

was a well-traveled French nobleman – including time spent in England

(1729-1731), where he became impressed with the social progress

underway there since the "Glorious Revolution" of the late 1600s ...

and the growth of Parliamentary power under the Hanoverian kings.

He was to have a tremendous impact on rising political thought –

especially in America where his writings, most notably The Spirit of

the Law (1748) would eventually guide the Constitutional Framer and

future U.S. President Madison greatly in his understanding of what

constitutional law is all about: what it is to achieve, and how it is

to do that.

Montesquieu,

was a well-traveled French nobleman – including time spent in England

(1729-1731), where he became impressed with the social progress

underway there since the "Glorious Revolution" of the late 1600s ...

and the growth of Parliamentary power under the Hanoverian kings.

He was to have a tremendous impact on rising political thought –

especially in America where his writings, most notably The Spirit of

the Law (1748) would eventually guide the Constitutional Framer and

future U.S. President Madison greatly in his understanding of what

constitutional law is all about: what it is to achieve, and how it is

to do that.