10. ENLIGHTENMENT ... AND REVOLUTION

"REVOLUTION"

CONTENTS

The American "Revolution" The American "Revolution"

(1770s-1880s)

The French Revolution (Mid-1770s to the The French Revolution (Mid-1770s to the

Early 1780s)

Napoleon Bonaparte Napoleon Bonaparte

The American and French Revolutions The American and French Revolutions

compared

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 401-415.

THE AMERICAN "REVOLUTION"

(Mid-1770s to the Early 1780s) |

|

The monarchical principle in trouble

When Prussia's popular King Frederick II (the Great) blocked an

Austrian attempt to retake Silesia with his own surprise attack on

Austria's ally, Saxony – and then treated high-handedly the

Polish-Saxon royal family (directly connected to Louis XV of France) in

their defeat – European nobility (and even French commoners) were

outraged. This was not how royalty were to be treated.

But in fact, royal absolutism was beginning to slip. Questions

were now being raised on the European continent about the divine rights

of kings. As humanist rationalism blossomed among Europe's

intellectuals and aristocrats, the very idea of God-given authority

certainly found itself losing its compelling qualities. If divine

rights lost its grip on the minds and hearts of Europeans, what then,

morally speaking, justified all this royal absolutism?

Indeed, the Enlightenment had unleashed all sorts of philosophical

conversations about reforming European governments in order to make

them more rational, more "enlightened." The debacle of the French

role in the Seven Years' War, plus the shocking state of the French

king's finances, plus rumors about the king's mistress, Madame de

Pompadour, and her role in the rapid turnover of the King's advisors,

all became topics of conversation by intellectuals and noblemen (female

as well as male) who gathered in the "salons" of fashionable French

homes to discuss the decaying state of French society. But the

conversations could also be heard in the streets of Paris by commoners,

who raised many of the same questions.

George III's royalist absolutism

During the course of the recent war George II died (1760) and his place

was taken by his 22-year-old grandson George III. However this

George was not a German ... but was fully English (he never even

visited his estates in Hanover). He was very well educated or

"Enlightened" in his youth ... and was tightly disciplined by his

mother, who took the responsibility of making sure that her son would

some day be every bit the absolutist king (that the first two Georges

were not!) that the Bourbon family of France modeled for the rest of

Europe's royalty.

For the American colonies, who under the first two Georges had been

left largely alone to conduct their own political and economic affairs,

George III's efforts to live up to his mother's expectations of him as

an absolutist king would soon enough fuel the fires of full rebellion.

Taxation without representation

Because of the Seven-Years' War, George III's debt had nearly doubled

in size and he needed new taxes to replenish his royal treasury.

His thinking was that the colonies had benefitted from his military

action in America and therefore they should pay up ... without

considering that they had carried much of the burden of the action

themselves without compensation. Worse he simply imposed new

taxes without first consulting the colonial tax payers themselves – in

direct violation of an ancient right of all Englishmen to be consulted

first. The Whigs in the English Parliament were sympathetic to

the colonials when they began to object loudly; the Tories however

supported the King's rather autocratic move. And at this point

George was relying principally to his Tory supporters.

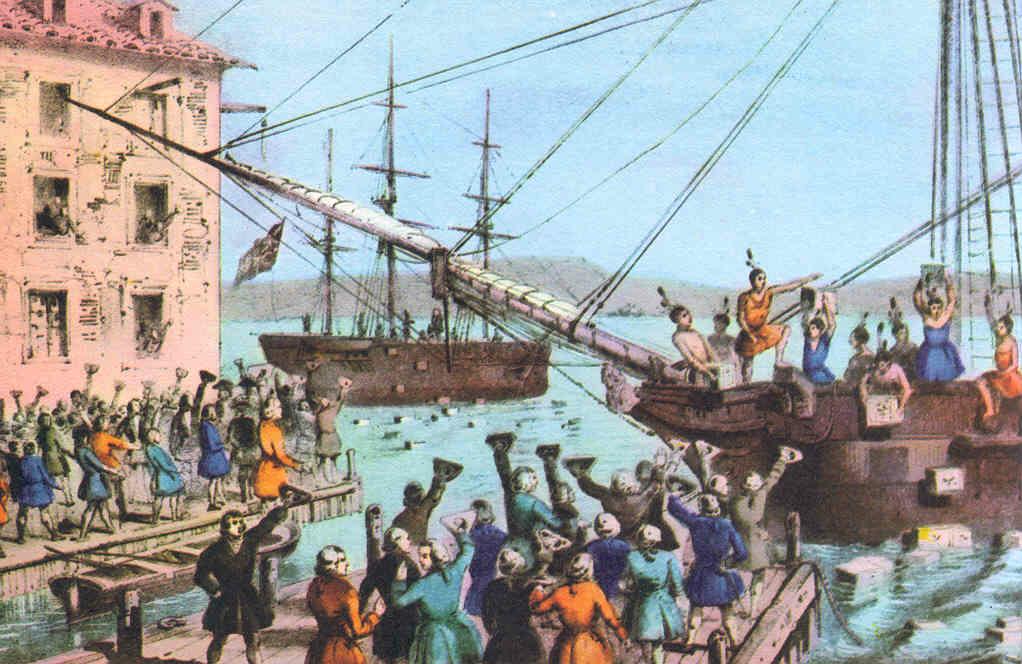

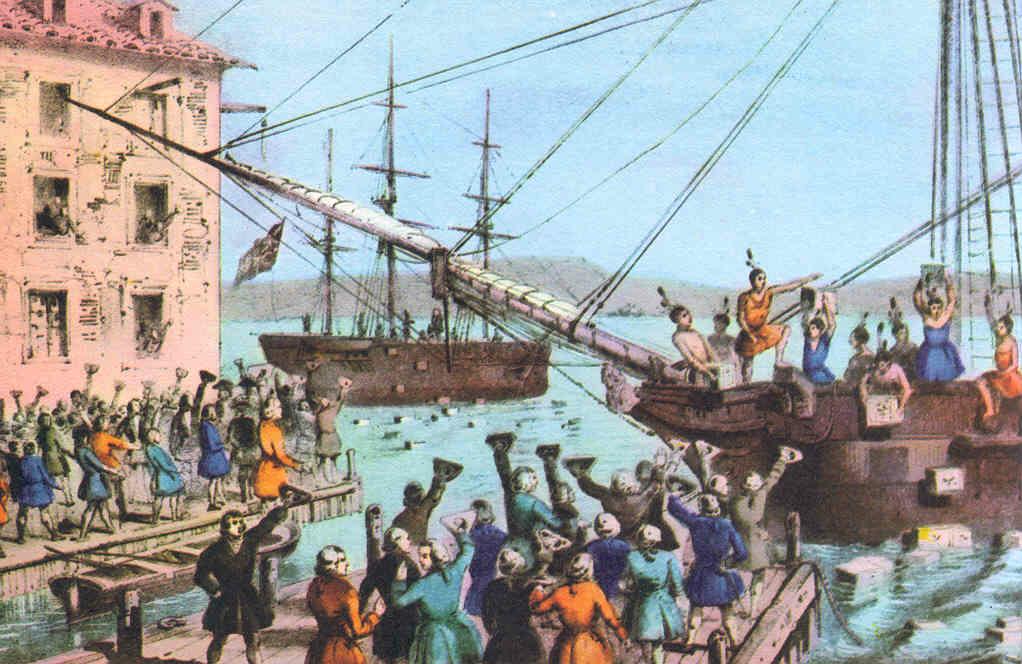

Growing conflict

Also, the King began to take the attitude that the colonials were far

too independent-minded and needed in principle to be shown who now was

in charge (unlike his immediate predecessors). Thus the King sent

soldiers to America to protect the tax collectors ... to which the

citizens of Boston reacted by dumping tea into the Boston harbor

(1773).3 George countered (1774) by shutting down the port of

Boston and forcing their citizens to house the often unruly soldiers

... to break their spirit. Then he moved to make good on his

promise to France to outlaw the further expansion of colonial

settlements westward so that the Catholic French could place their own

settlements there. Also there were the rumors that he was going

to bring the independent congregations of Protestant America under

episcopal authority (rule by bishops) ... and thus under his direct

control as head of the English Church.

War

Finally war started (1775) when he sent his troops by night to seize

the gunpowder stored in Concord ... producing actual s

hooting on both

sides (which the British received the worst of). When colonial

troops then gathered in the heights above Boston the English

counterattacked and finally after much loss of life (twice the numbers

on the British side) the colonials withdrew ... returning that winter

but this time with cannon in the heights around British-held

Boston. The British then wisely vacated Boston ... never to

return.

That next summer (1776) the colonials made formal what was clearly

evident in their behavior: they considered themselves a fully

independent people. It was a daring move. The Dutch had

performed this same feat ... but it had taken them some 80 years

(1568-1648) of agonizing war to carry off their own independence.

The colonials were considered in comparison to the sophisticated Dutch

a rather boorish people. The English expected the crushing of

this rebellion to be short work. Other Europeans stood by

wondering.

The French join the action

But the wondering ceased when in 1777 the colonials destroyed a British

army of 6,000 men at Saratoga. France now joined the war on the

American side ... the recently crowned French King Louis XVI more than

happy to make whatever trouble he could for British King George III.

The impact on French thinking

Thus the new conflict began to take shape the way dynastic conflict

typically did ... except that Louis had no idea of what he was getting

involved with. The idea of a subject people rising in rebellion

against their king was not a principle he should have been supporting

... no matter how much trouble it brought France's traditional royal

enemy England. His soldiers who served in America would certainly

become infected with the idea that the people had political rights of

their own ... and that it was okay for them to break free from their

sovereign king when they possessed the moral right to do so.

Considering that the Enlightenment conversations in the French salons

were already bringing up such questions as the right and wrong of

politics, the American rebellion was likely to prove toxic to French

politics. And indeed it did.

American victory

With key French help in the huge British defeat at Yorktown (1781), the

colonials finally broke the last of the English will to continue the

conflict ... and the English sued for peace. The Americans had

done it ... secured their independence from royal rule in basically

five (but very hard) years!

For more (much more) on America's War of Independence For more (much more) on America's War of Independence

3Actually

the reaction was not only about taxes but also about the fact that the

King was subsidizing the earnings of the struggling British East India

Company ... forcing the colonies to buy their tea when in fact Dutch

tea was much cheaper.

Bostonians reacting to the

Stamp Tax

Bostonians reacting to the

Stamp Tax

Library of

Congres

The Boston Tea Party - December

16, 1773

The Boston Tea Party - December

16, 1773

(actually a night-time

caper!)

Museum of the City of New

York

The Death of General Warren

at the Battle of Bunker Hill (Breed's Hill) - June 1775 -

by John Trumbull

Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston

Alexander Hamilton's American

Troops overrun the English Redoubt-10 at Yorktown

- October 14, 1781

Virginia State

Capitol

|

The uniting of the thirteen new states as a federation

In

coming together to fight George III's aggressions, the inhabitants of

the English colonies in America had certainly thought of themselves

quite seriously as "Americans." Otherwise they still typically

saw themselves as Georgians, Virginians, New Yorkers, etc.

Thus when the English armies were finally sent back to England at war's

end, they proceeded to look to the development of their former colonies

as newly independent states, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey,

Virginia, South Carolina, etc. Despite a continuance of the

Confederation that had held them together during the recent war, the

lack of a continuing common cause had demonstrated the weaknesses built

into this union. Thus they were beginning to compete diplomatically and

economically with each other in their ongoing relations with the Old

World of Europe. They were even erecting trade barriers against

each other's products in the hope of encouraging the development of the

industry and commerce of their particular state.

Those who had given so much of themselves during the war now grew

alarmed at where this new narrow view of patriotism was taking them.

Not only was this hurting the Americans financially, but their disunity

could give opportunity to one of the major European powers (Spain,

France or even England) to come and force them back into colonial

status.4

Particularly now choosing to work independently of each other, any one

of these small states would be an easy pickoff by the more powerful

European monarchs.

Thus delegates from twelve states (Rhode Island refused to

participate) gathered in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to put

together some kind of a stronger constitutional union that would face

them outward in common defense ... and inward with an agreement to do

away with these trade barriers they had been erecting.

But many were suspicious of a central power (they had just fought off

the power of the English King and Parliament) and would come to support

the idea of a union only under the promise of a number of guarantees

that this federal union would not compromise the powers of the states

... and the people themselves. Thus a promise was made to add a Bill

of Rights to the Constitution as soon as it was ratified and a new

government formed under its provisions.

The Constitution itself provided for a system of power distribution

that would use the natural human tendency of those in power to want to

accumulate even more power ... to have that tendency offset by other

parts of the governing system acting in the same way. This system was

well recognized at the time (thanks to the writings of the French

political philosopher Montesquieu who had studied carefully the

mechanics of the British government) and was termed the

"checks-and-balances" system. Law-making powers were assigned to a

Congress of two Houses, a Senate representing the States and a House of

Representatives representing the citizen voters. But the legislative

powers of Congress were carefully limited to only those outlined in the

Constitution itself. A President was designated as the chief executive

officer (and head of the military and the diplomatic corps) whose job

was to oversee the implementation of the laws made by Congress. And a

federal judiciary was designated to try cases coming under

constitutional law. All other powers, most particularly the laws that

guided the daily affairs of the American people were (by the Bill of

Rights) reserved to the States ... and to the people themselves. Thus

the Constitution provided for a limited government to protect the unity

of the individual states ... and little more than that lest it should

want to take upon itself ever wider powers. It was understood that

sovereignty remained with the people and the states.

Whether or not this system would continue to work as originally

intended would ultimately depend on the people themselves. The

historical record for popular vigilance in this regard was not good.

Thus when Benjamin Franklin was asked at the end of the meetings that

had been held in secret as to what kind of government they had come up

with his answer was: "a Republic ... if you can keep it."5

For more (much more) on The Birth of the American Republic For more (much more) on The Birth of the American Republic

4Treaties

in those days were indications only of a pause in a conflict ... not

its resolution. Treaties were made and unmade in rapid

succession. Thus the Treaty of Paris recognizing American

independence by the British could be broken at any time the British

noticed a weakness among any of the American states.

5Note: of critical importance.

Keeping those powers separate and not having them come – by human

instinct itself – into the hands of a smaller and more powerful group

of authorities has been very difficult, even in America, where the

national authority has slowly stripped state and local authorities of

much their power, where federal judicial authority (most notably the

Supreme Court) has taken on greater legislative powers than Congress,

and where the president employs executive power solely in accordance

with his own personal tastes … and through extensive bureaucratic

control of the nation's life – control that Congress seems unable (or

unwilling) to check.

Signing the Constitution

of the United States - by Howard Chandler Christy

Architect of the Capitol

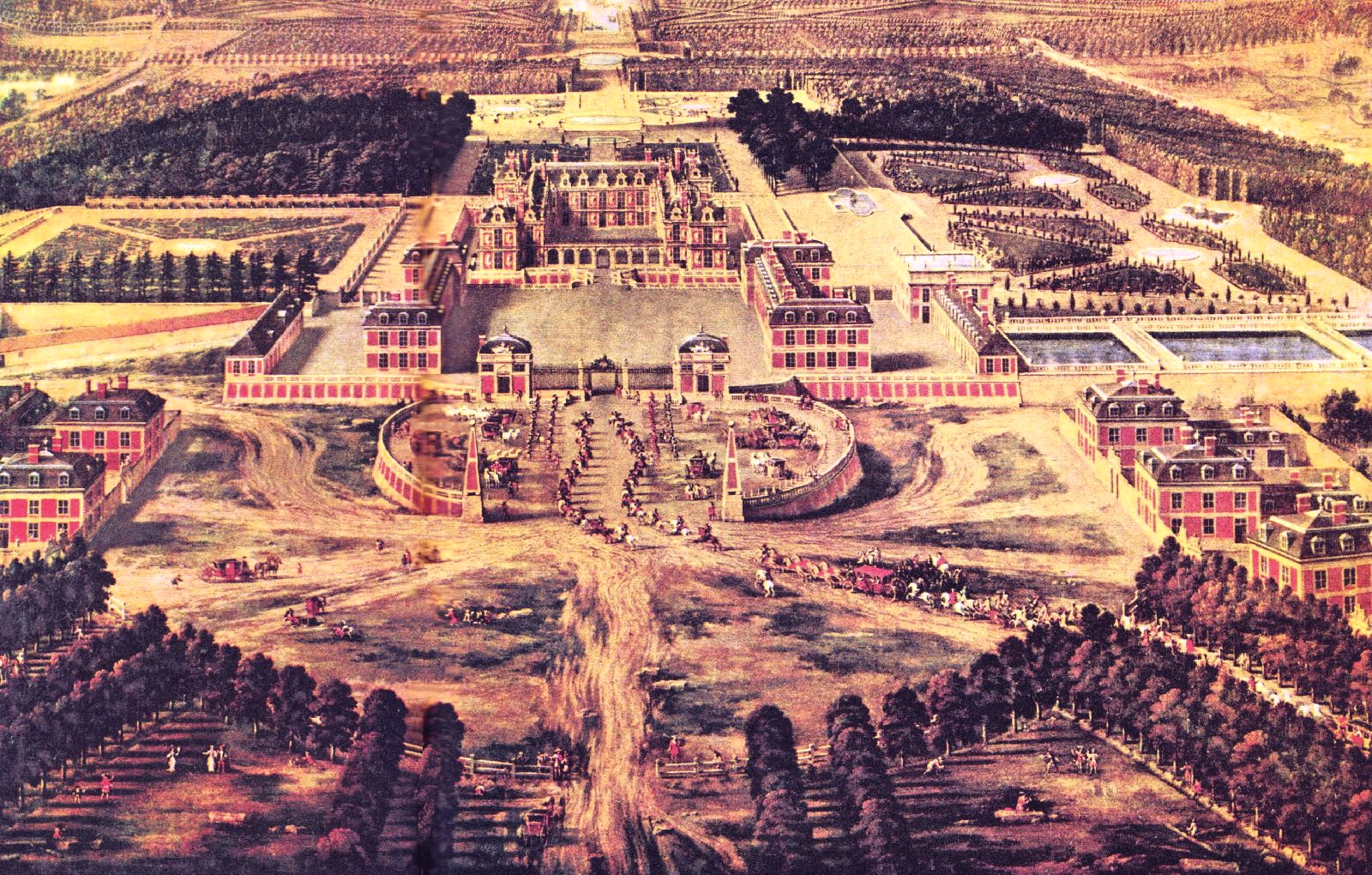

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION (1789-1799) |

|

Supporting

the war in America of course had only worsened the situation for the

French royal treasury (once again!). Taxes would have to be

raised. And because both the Church and the nobility were

exempted from taxation, this would all fall on the French tax-paying

commoners (the moneyed middle class), who were already heavily burdened

with taxes. Discussions about revising the tax system led

nowhere. Eventually the discussion moved to the idea of taxing

the nobility ... gaining opposition from that quarter... but merely

highlighting all the more the privileges of the nobility versus the

burdens of the commoners. At this point (May 1789) Louis XVI was

forced to turn to the Estates-General (a French National Assembly

representing all three estates of: church, nobility and

commoners). Because of the practice of royal absolutism, this

august body had not been convened by a French king since 1614.

With this call to assemble, French politics exploded.

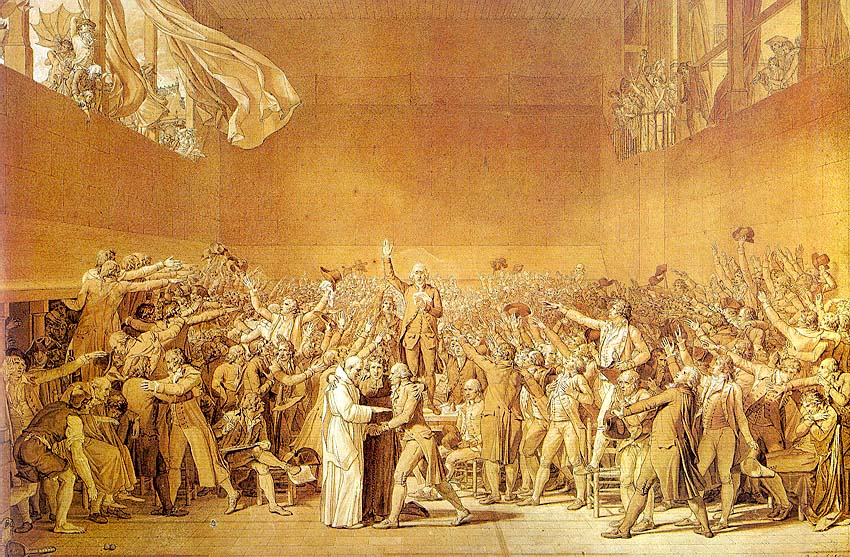

It was apparent from the beginning that the Third Estate (commoners)

was going to dominate the proceedings ... and had a number of economic

and political reforms they were demanding to be put in place or they

would not be willing to cooperate with the King. Seeing the

calling of the Estates-General as a mistake, Louis then tried to shut

down the assembly (June), only to have the members of the Third Estate

move to a nearby tennis court, and there swear an oath to not leave

until a new constitution was granted by the king.6

Indecisive behavior by the King, the arrival of troops to Paris, and

all sorts of rumors circulating around the streets of Paris, set

off rioting and looting culminating in the storming of the Bastille

castle (July) and the complete breakdown of royal authority when the

King's troops began to side with the Paris mob of sans culottes

(workers who wore trousers rather than knee-length silk breeches or

culottes).

At this point the Third Estate was now meeting as the "National

Constituent Assembly," working on a new Constitution for France, which

included the ending of all the privileges of the Church and the

nobility. Frenchmen of all classes now stood equally before the

law, stated clearly in the new Declaration of the Rights of Man (August). In one stroke, French feudalism had come to an end.

Some

noblemen were willing to go along with the new France. But many

(émigrés) showed their opposition by fleeing to other countries ... and

appealing to the rest of European nobility to form a counter-revolution

in order to restore the nobility's ancient feudal rights in

France. This merely put all the nobility (and upper-level Church

authority) in the eyes of the new French "citizen" under suspicion of

treason.

Then when the King himself attempted to escape France (June 1791) and

was caught at the border, he was returned to Paris now also under

similar suspicion.

The target of reform was not only the old royal-feudal structure of

France but also the Church organization that had long supplied it its

legitimacy. Church property was turned over to the Assembly,

which then sold the land in order to raise needed revenues.

Clergy now became civil employees paid by the State, required to swear

loyalty to the State rather than the Pope. Most clergy refused

and were treated as traitors.

The Constitution was finally approved in September of 1791, providing

for a constitutional monarchy: a single legislative body

(basically the National Assembly), a monarch with limited veto powers,

and an independent judiciary. But it was short-lived ... as the

King used his remaining powers to protect priests who had refused the

oath of loyalty to France rather than the Pope. He was also

accused of showing little interest in organizing a national army to

protect France from the larger reaction against the Revolution by the

surrounding powers. Thus when French action against the

Austrians and then the Prussians proved dispirited and unsuccessful,

the blame fell on the King.

6Certainly

influencing French thinking along these lines was the coming into full

effect of the new American Constitution, when just a couple of months

earlier (April) Washington was sworn in as the new American President.

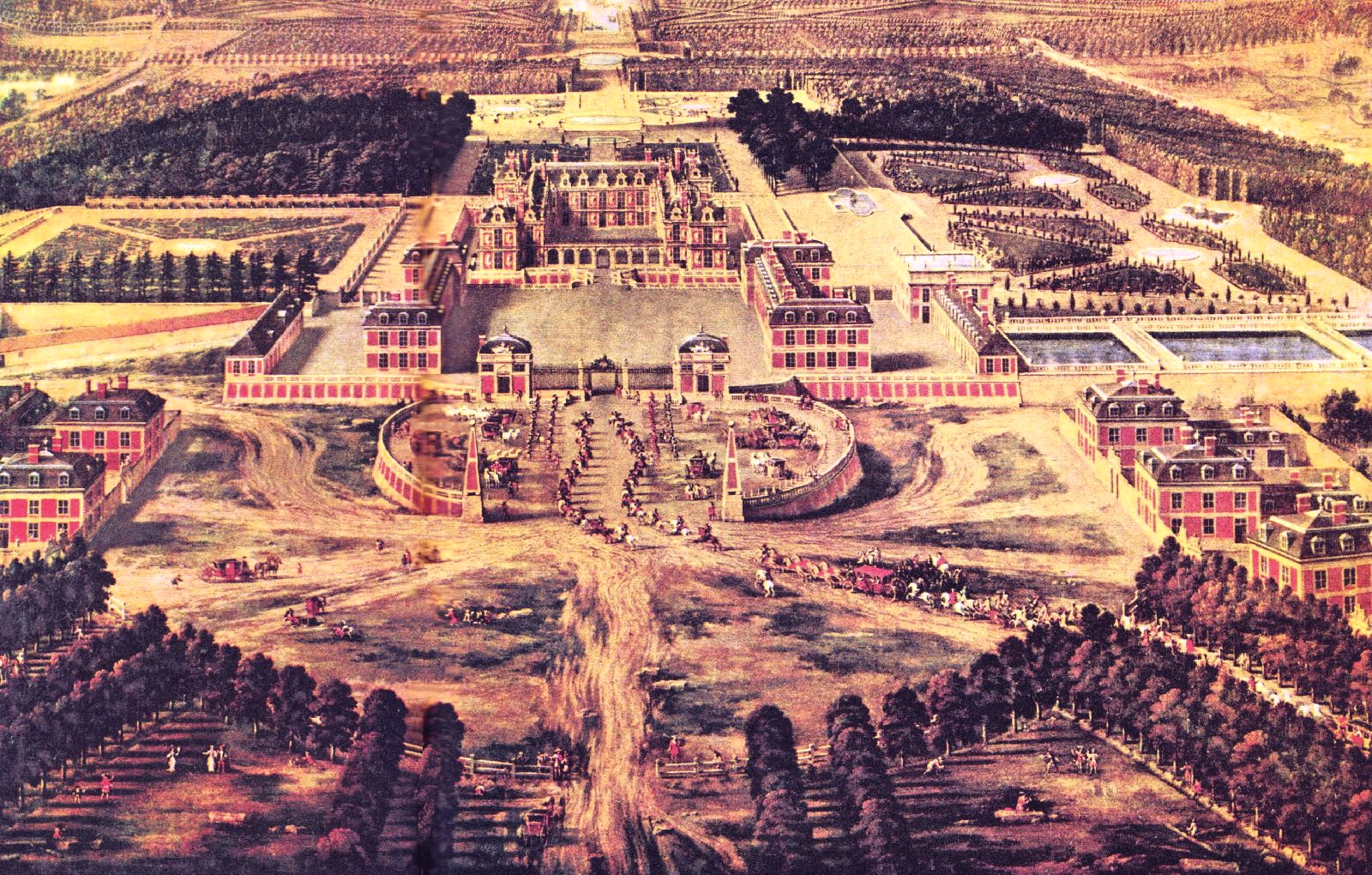

Versailles Palace in the

period just prior to the French Revolution

Musee de Versailles -

Giraudon

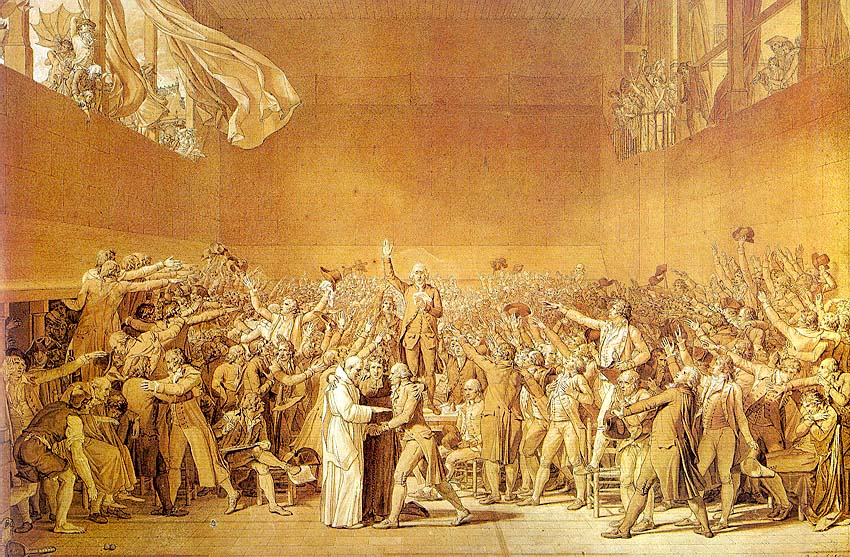

Sketch by Jacques-Louis David

of the Tennis Court Oath (French: serment de jeu de

paume)

Sketch by Jacques-Louis David

of the Tennis Court Oath (French: serment de jeu de

paume)

| A pledge signed by 567 of the 577

members of the French Third Estate (and a few members of the Second Estate)

on June 20, 1789 at a tennis court near the Palace of Versailles.

They had regrouped themselves as the National Assembly after being dismissed

from the gathering of the Estates-General -- and swore that they would

not leave until a new constitution was granted by the King (the artist Jacques-Louis David later

became a deputy in the National Convention in 1792).

|

Jean-Pierre Houël (1735-1813)

- Prise de la Bastille ("The Storming of the Bastille")

The Return of French King

Louis 16 to Paris - June 25, 1791 - colored copperplate by Jean

Duplessi-Bertaux after a drawing of Jean-Louis Prieur

|

The insurrection

The Assembly now seemed to be given over to increasingly radical voices

calling for the King's abdication. At the same time

anti-Revolutionary sentiment seemed to be spreading in the conservative

(and still quite pro-Catholic) countryside ... especially the Vendée

... adding to the nervousness of Paris. Finally in August of 1792

a bloody Paris insurrection exploded and the indecisive King lost the

last of his powers ... and was arrested and imprisoned. At this

point the Assembly (heavily represented by lawyers) also lost its

powers, as Paris came under the control of local committees made up of

a variety of radicals, some of even a working-class background.

|

The Storming of the Tuileries

Palace by members of the Paris Commune, August 10, 1792 -

by Jacques Bertaux

Palace of Versailles

|

The Convention

Elections were then called (with all adult male Frenchmen voting) to

send representatives to a new constitutional Convention. When it

met in September it decreed the end to the monarchy, the beginning of

the French (First) Republic, and a new non-Christian calendar beginning

at year 1 (1792).

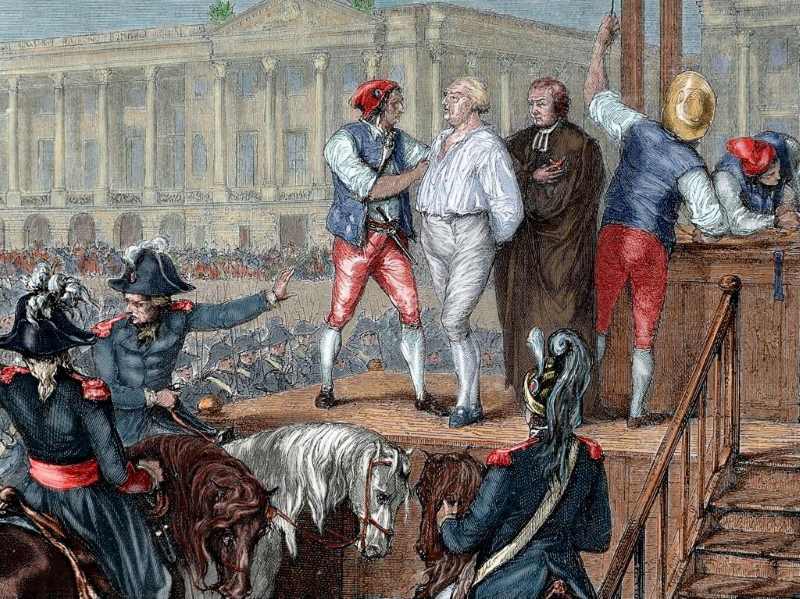

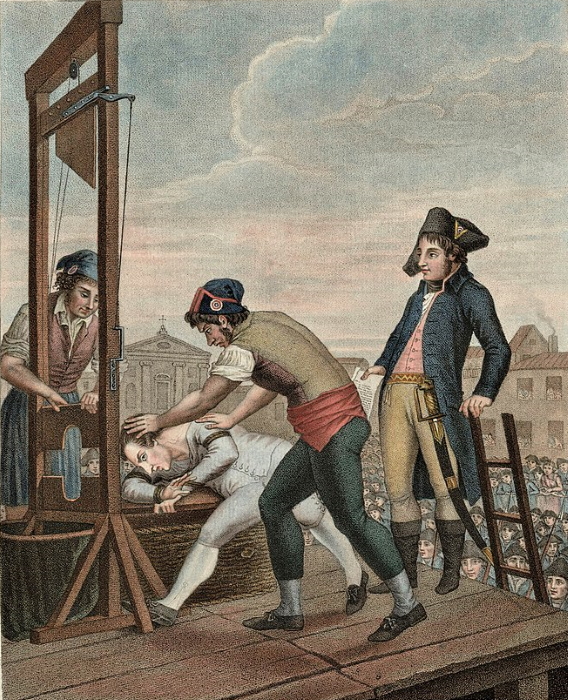

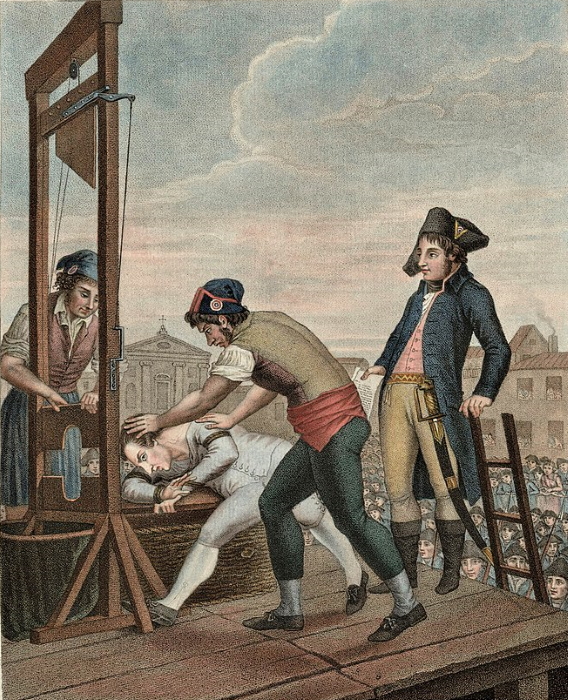

The King is guillotined

The

Girondins, led by the more pragmatic Georges Danton, were less radical

than the Jacobins. The Girondins were less interested in bringing

the King to trial than in keeping the Paris Commune from totally

dominating all aspects of the French Revolution. The Jacobins, led by

the Idealist Maximilien Robespierre – and which interestingly included

in their ranks a number of noblemen, including even the King's cousin

Louis Philippe – reflecting Paris radicalism, were in favor of the

King's death. A vote in early 1793 on the matter split the

Convention, with the Jacobins (and some Girondins) gaining a small

majority. Thus the King was executed at the guillotine like a

mere commoner three days later.

It was shocking. A king had been executed by his own people. But

this merely marked the beginning of the Republic's struggle to find

some semblance of political structure. With the King out of the

way, Girondins and Jacobins turned on each other. Robespierre's

Jacobins accused Danton's Girondins of conspiracy to betray the

Revolution ... with every attempt to answer the accusations making the

Girondins look all the more guilty. The Paris mob now was at the

door, demanding the expulsion of the traitors (the Girondins).

Twenty-nine Girondin leaders were arrested and carried off. The

Girondin party was devastated (summer 1793).

.

|

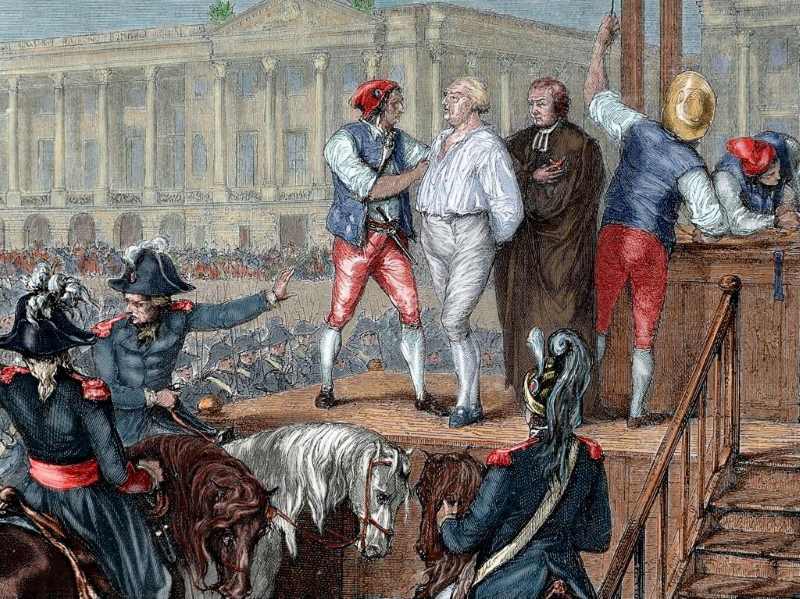

The execution of Louis XVI,

January 21, 1793

The Republican Constitution (1793)

The way was clear now for the finishing of the new Constitution.

The preamble was even more utopian than the earlier Declaration of

Human Rights.

Not only was freedom of speech and press and equality of all before the

law guaranteed, the Declaration proclaimed that all French had the

right to education, to work, to receive public assistance, even to rise

in rebellion if the government failed to deliver on these rights.

Even though the Constitution provided for a Legislative Assembly, since

the days of the Convention the real work had been performed through a

series of committees, the most important of which was the Committee of

General Security (searched for enemies of the Revolution to bring to

"justice"). With the creation of the Republic that function was

then taken over by the Committee of Public Safety.

|

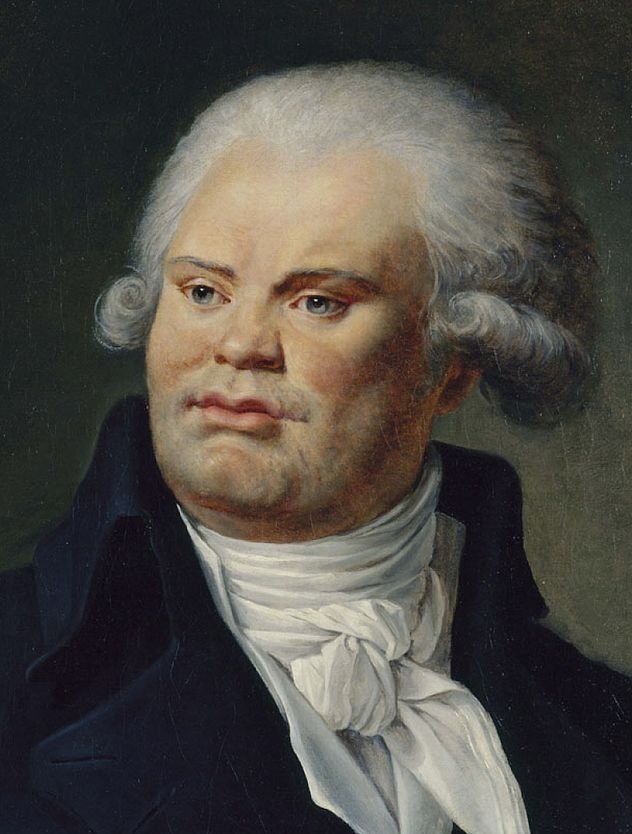

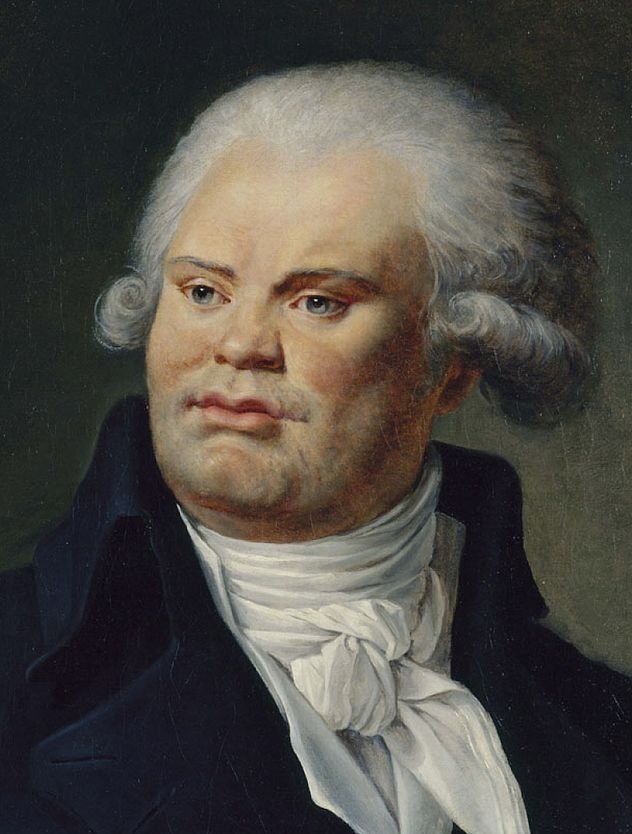

Georges-Jacques

Danton

| All executive power was conferred

upon a Committee of Public Safety (6 April 1793) made up of 9 members,

of which Danton was one. However he himself was executed April 5, 1794.

|

Maximilien Robespierre,

1758-1794

Maximilien Robespierre,

1758-1794

| It was Robespierre's belief that

political terror and virtue were of necessity inseparable. "If virtue

be the spring of a popular government in times of peace, the spring of

that government during a revolution is virtue combined with terror: virtue,

without which terror is destructive; terror, without which virtue is impotent.

Terror is only justice prompt, severe and inflexible; it is then an emanation

of virtue; it is less a distinct principle than a natural consequence of

the general principle of democracy, applied to the most pressing wants

of the country. … The government in a revolution is the despotism of liberty

against tyranny." "On the Principles of Political Morality"

(1794).

|

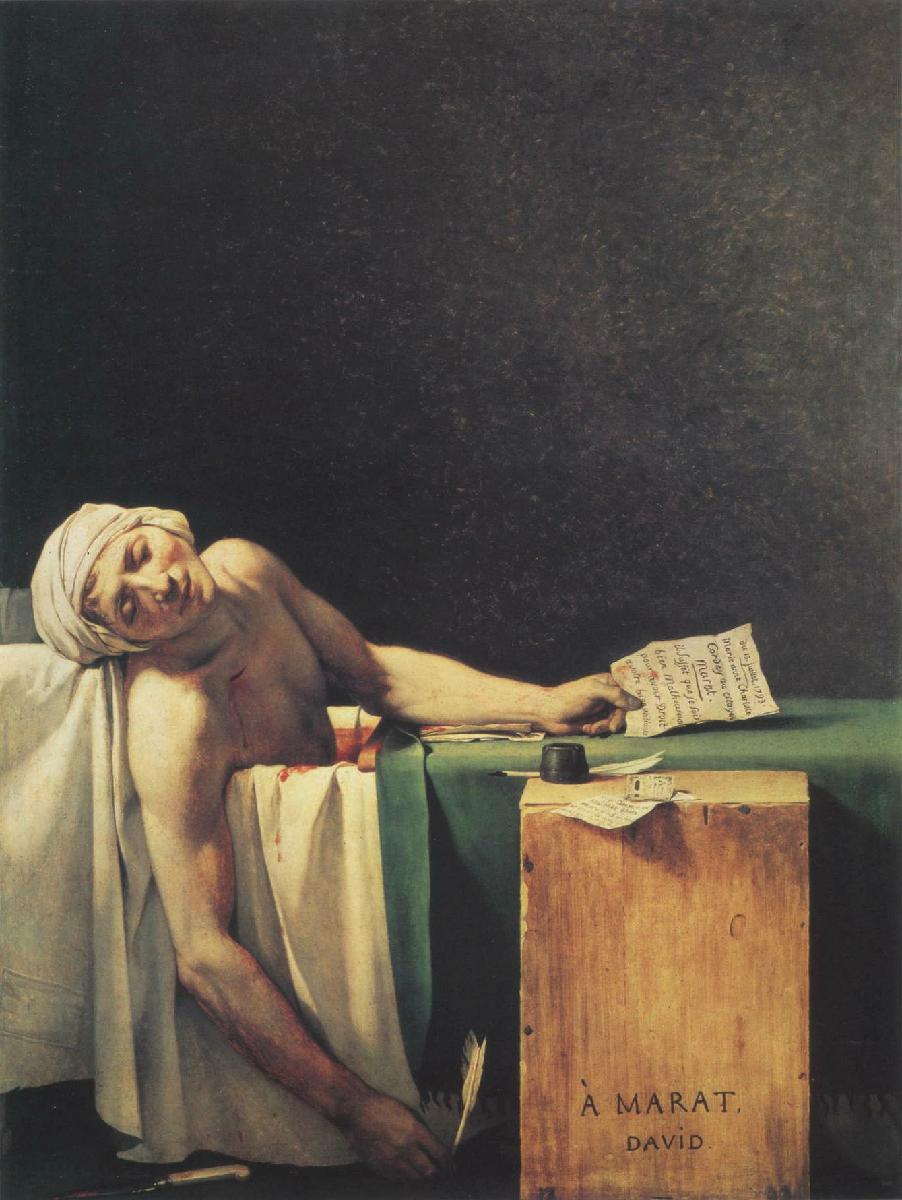

Jean-Paul

Marat

Jean-Paul

Marat

| A radical journalist, publisher

of L'Ami du peuple, who strongly supported of the September 1792

massacres and, in compiling his "dealth lists," was a strong encourager

of what was to eventually become the Reign of Terror ... though he himself

was stabbed to death in his bathtub by self-proclaimed Girondist Charlotte

Corday on July 13, 1793, just prior to the startup of the Terror.

|

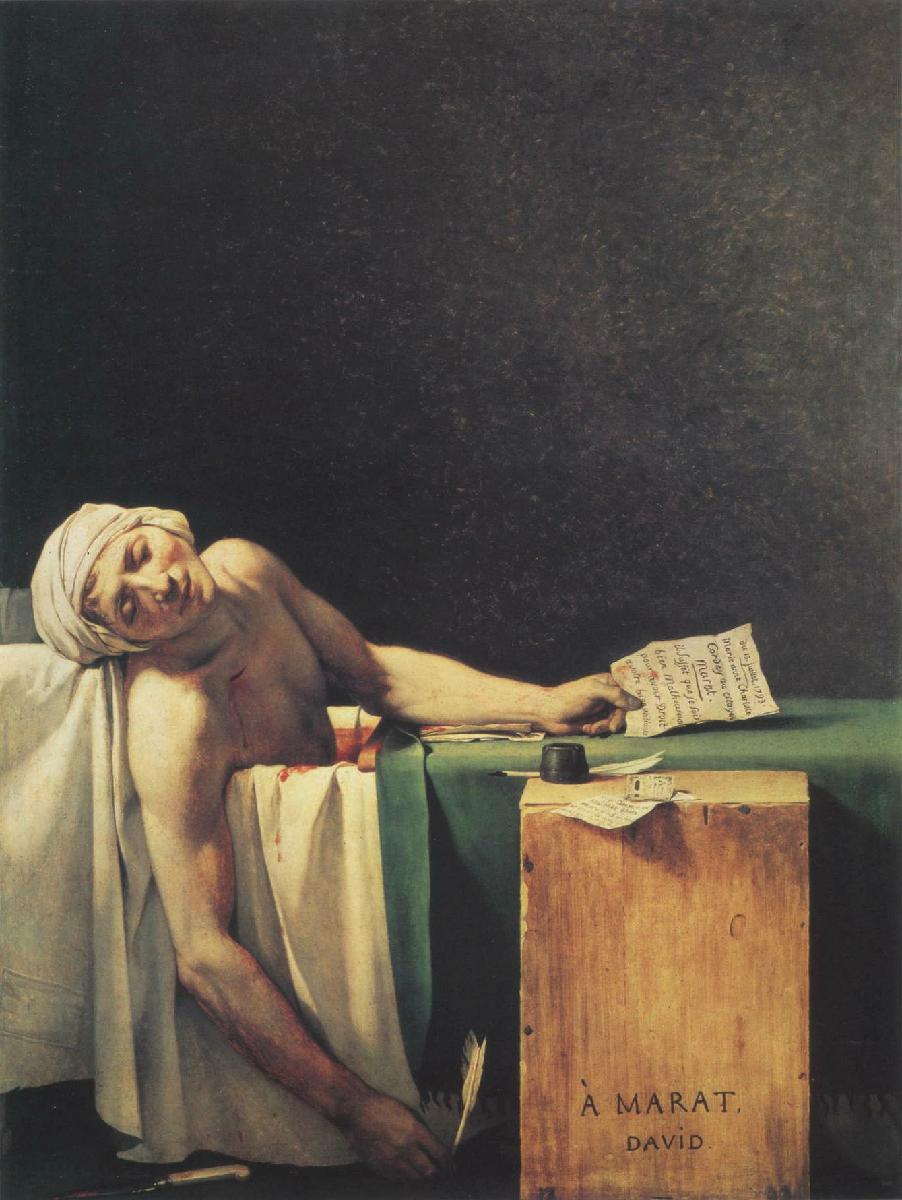

Charlotte Corday and Jean-Paul

Marat Charlotte Corday and Jean-Paul

Marat

| Repulsed by the massacre of September

1792 that Marat had encouraged, she came to his house ostensibly to report

on a Girondist plot and give Marat names for his death list. But

she stabbed him -- and was quickly apprehended and guillotined several

days later. This became a major contributing event to the Reign of

Terror as the Jacobins began their massacre of Girondists and other "enemies"

of the Revolution.

|

Jacques-Louis David – Death

of Marat (1793) oil on canvas

Jacques-Louis David – Death

of Marat (1793) oil on canvas

Brussels, Musées Royaux

des Beaux-Arts

Marie-Jeanne Roland de la

Platière (1754 - 1793) by Adelaide Labille-Guiard - 1787

| Her salon in

Paris had earlier become the rendezvous of Brissot, Pétion, Robespierre and other leaders

of the Revolution; but when she and her husband became critiques of the

cruel excesses of the Terror, she fell from favor with the radical Montagnards

or Jacobins (Danton and Robespierre). She was executed November 8,

1793.

|

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas

de Caritat, marquis de Condorcet - French mathematician and

philosopher

|

Condorcet wrote Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de

l'esprit humain

while in hiding (October

1793 - March 1794) from the Jacobins. He was arrested and died of

poisoning in prison.

His book was published the

following year by his wife.

|

|

The "Reign of Terror" (1793-1794)

In October, trials of the enemies of the Revolution began in

earnest. The Queen was guillotined, then much of the Girondin

leadership as well. As arrests began to become more widely

sweeping through French society, the Committee of Public Safety, now

headed by Robespierre, became more absolute in its control.

Indeed, by the end of 1793 Robespierre was the virtual dictator of

Republican France.

Not only did the Paris guillotine work overtime to kill thousands of

enemies of the Revolution, the French army found itself busy in the

French countryside putting down anti-Revolutionary rebellions.

Worst was in the Vendée where the army conducted something akin to

genocide in bringing the people of that province into submission.

Estimates of those who died in the Vendée range from a quarter to over

a half of the population of 800,000.

By the next summer (1794) the Revolutionary Tribunal was at its most

active in trying and executing the Republic's enemies at home.

The Jacobins were persuaded that only terror could shake the people's

feudal Catholic mindset and free them to rise fully to the rule of

human "Reason."

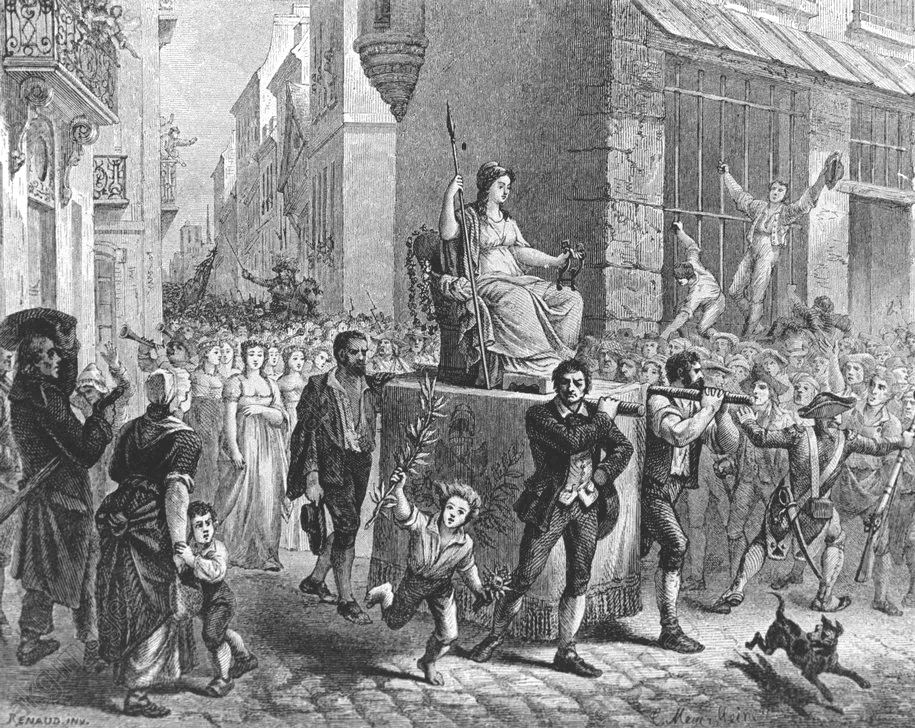

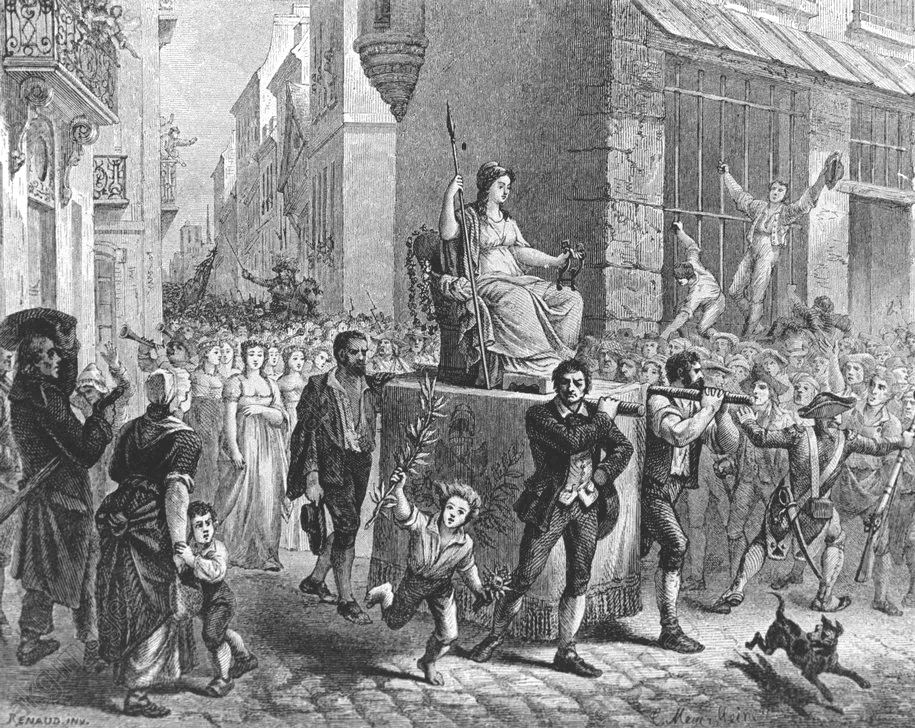

Indeed, the Cult of Reason was intentionally set forth as the new

state-sponsored atheistic worldview (or religion), designed to replace

France's long-standing Catholic foundations. As such, "Reason"

was required of all those true to French Republicanism. Thus it

was that in November of 1793, at the height of the Reign of Terror,

churches across France were forcibly transformed into Temples of

Reason, including most importantly Paris's Notre Dame Cathedral – where

a huge procession followed a newly appointed "Goddess of Reason" and

her white-clad girls into the cathedral and placed her on the altar to

be worshiped. This worship of "Human Reason" in turn merely

stirred more deeply the radical instincts of those most dedicated to

the "social cleansing" taking place in Paris and across much of France. |

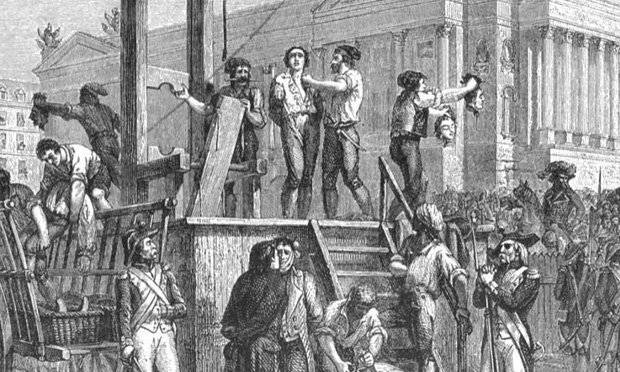

The Reign of Terror as the French revolutionaries turn on each other - 1793-1794

The Goddess

"Reason" is carried to the Notre Dame Cathedral - 10 November, 1793

The Goddess

"Reason" is carried to the Notre Dame Cathedral - 10 November, 1793

But

the public mood itself was now beginning to turn against all this

social terror, a terror that Robespierre praised as the hallmark of

true Republican Revolution. When in July (1794) 16 nuns went

singing to the Paris guillotine for the crime of choosing to remain

nuns, things took a turn for Robespierre. Political jealousy

within the Committee of Public Safety also motivated his arrest (end of

July) ... and execution the next day.

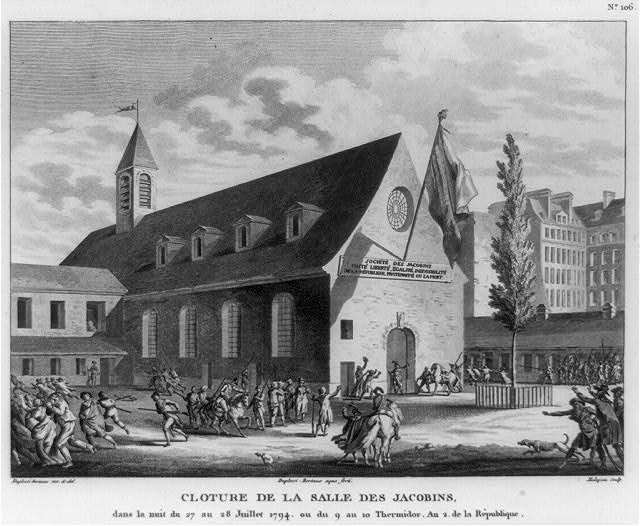

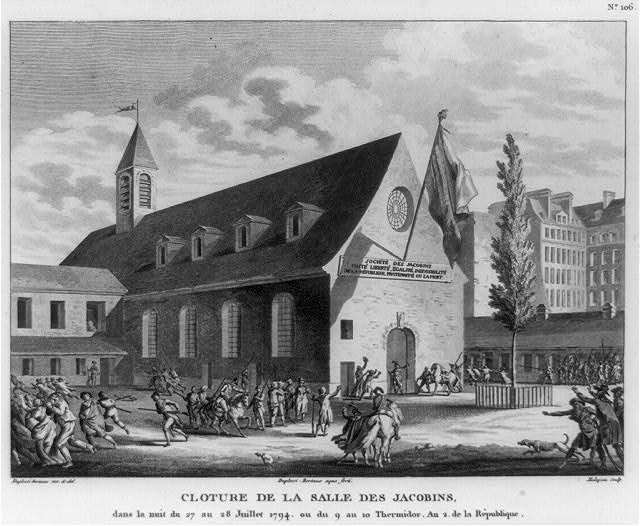

With the downfall of Robespierre (and other Jacobin leaders) the

Committee of Public Safety lost influence ... and eventually the use of

the word "terror" itself became a crime. The Thermidorian

Reaction had set it.

|

Robespierre is himself executed - July 27, 1794

Closing of the Jacobin Club,

during the night of 27-28 July 1794, or 9-10 Thermidor, year

2 of the Republic

Closing of the Jacobin Club,

during the night of 27-28 July 1794, or 9-10 Thermidor, year

2 of the Republic

Print by Claude Nicolas

Malapeau (1755-1803)

after an etching by Jean Duplessi-Bertaux

(1747-1819)

|

The Directory (1795-1799)

Surviving Girondists now took charge, wrote a new constitution and put

it before the people, who approved it overwhelmingly. The new

constitution provided for a bi-cameral legislature and a five-man

executive committee, termed the Directory. Unfortunately for

France this executive scheme proved largely unworkable (in part also

because of the poor level of political talent among the

directors). The Directory tried to step back from the excesses of

the Revolution ... and was able to do so only because politically the

country was exhausted. But these were shaky foundations.

Besides, the French government still had not solved the problem of an

empty state treasury ... and the economy in general was in very bad

shape. And corruption was a problem the new government seemed

unable to overcome.

The French army

The major difference between the French army and those of its enemies

was that the French army, by the end of 1792, was made up of masses of

conscripted or drafted commoners ... literally hundreds of thousands of

new "citizens" called on to defend their Republic ... whereas the

armies of their adversaries tended to be paid soldiers, forming smaller

armies limited in size by the size of the treasury of their royal

employers. Also the French developed the use of different

services in tactical support of each other, particularly the use of

artillery in support of the infantry (and of course cavalry for the

same purpose). Particularly skillful in this regard was a young

artillery officer, Napoleon Bonaparte ... who would soon distinguish

himself as an excellent tactician.

Advance against other European powers

The French found some degree of sympathy for the Republican cause in

other parts of Europe ... in particular among the Dutch, who in 1795

set up (with the help of the French army) a new Batavian Republic –

something of a sister republic of France's. Also Prussia turned

the west bank of the Rhine over to France ... in order to concentrate

on its war with Poland. Spain was pacified (1795). Then

Napoleon advanced into northern Italy, defeating both Italian and

Austrian efforts to block his advance (1796-1797). From Italy he

headed north to attack Austria, which soon called for a peace that

recognized the various expansions of the French borders (1797).

Napoleon was a fast-rising name in France. |

|

Rise to prominence

Napoleon had first distinguished himself by firing his cannons on

royalist uprising in Paris (1795) attempting to overthrow the new

Directory. This earned him (age 26) his appointment by the

Directory as General of the Army of Italy... which he honored with his

subsequent victories in Italy (against principally the Austrians and

the northern Italian states they dominated). As a national hero

he was able to cultivate political supporters within the Directory in

Paris ... making the Directory increasingly dependent on him personally.

The Egyptian campaign

Finding that the French navy was not ready for a direct assault on

Britain, Napoleon decided to take the war to the Middle East in order

to seize for France Britain's vital trade route to India. At

first (1798) he scored an easy victory against the Mamluk's Egyptian

Army. But Lord Nelson's British fleet soon showed up, destroyed

Napoleon's French fleet, and ended any idea of France controlling the

vital trade route to India. But Napoleon pushed on from Egypt to

Syria anyway (early 1799) ... into a world of hunger, disease (the

plague) and brutality – devastating his troops as well as the local

population.

Consul (or dictator) 1799

Hearing of mounting political confusion (and growing unpopularity of

the Directory) back in France – and finding no further opportunities

for glory in the Middle East – Napoleon decided to return to

Paris. Upon his arrival (oddly enough, to a hero's welcome) he

shut down the Council of Five Hundred and the Directorate, and named

himself Consul of France ... confirmed in a new French constitution

which in turn received in a national plebiscite almost total approval

(a rather suspicious tally of 3 million in favor, only 1500 opposed).

Emperor (1804)

There were numerous attempts to unseat, even at one point to

assassinate, Napoleon ... and he used one such incident to move (with

another highly approving plebiscite) to make himself "Emperor of

France" ... with the rights of succession to the title on the part of

any of his personal heirs. And so with the Pope in attendance,

Napoleon had himself crowned French Emperor in December of 1804.

He thus re-established in France the ancient principle of monarchy,

with himself as an imperial monarch. The First French Empire was

thus born.

Reforms

In so many ways Napoleon brought France into modern culture.

Besides modern military strategies, he introduced a new legal code –

one which would outlive him as a model followed not only in France but

widely in Europe (particularly in those countries where Bonapartist

rule once held sway) and even in many other parts of the world. It

replaced the complex mix of feudal customs with precise written rules

applied equally to all citizens regardless of social rank. He

reorganized the administration of France, ending its confusing maze of

feudal districts, instead dividing France into 80 départements of more

or less equal size, governed by prefects which he himself appointed,

thus tightening Paris's control over the rest of France ... and giving

it a truly national or French identity in replacement of the regional

loyalties characteristic of traditional France. He freed up the

sale or exchange of property ... and opened the trades or professions

to anyone trained for the work – and not just to those born to specific

guild families.

He extended to Catholic France, brutalized by the Revolution, his

Concordat of 1801 – restoring the Church and its priesthood to its

place of religious privilege ... though he did not return to the

Church properties seized during the Revolution. On the other

hand, he shut down the Catholic Inquisition and ended the restrictions

against Protestants and Jews. He liberalized France's divorce

laws. He also pushed for the development of more secular public

secondary schools (lycées). And he started France thinking in

metric terms (though full conversion to the metric system would not

take place until the mid-1800s).

Wars and more wars

However it is in the conduct of his many wars that Napoleon is largely

remembered. He was hugely successful ... most of the time.

In 1800 he pulled success out of a near disaster at Marengo (Italy) and

won overwhelmingly at Hohenlinden (Germany) against the Austrians.

In 1805, with the birth of a new round of war by a new coalition (the

"Third") of Britain, Sweden, Russia, and Austria, things got off to a

poor start for Napoleon when his own French-Spanish naval coalition was

defeated by the English at Cape Finisterre (Spain), ending his hopes

for an invasion of England by his Grande Armée. He then turned

his army east towards the Austrians, crushing them at Ulm. But in

the meantime his combined French-Spanish navies were again defeated –

decisively – at Trafalgar (Spain) by the English under Lord

Nelson. But the French were able to capture Austria's capital

Vienna ... and then move on to destroy a combined Austrian-Russian army

at Austerlitz before the end of the year. The resulting peace saw

Napoleon remaking the face of central Europe, putting to an end the

Holy Roman Empire and combining the hundreds of small but

semi-independent German states into a Confederation of the Rhine.7

Napoleon was at the height of his glory at this point.

In 1806 he marched against the ("Fourth") coalition of Prussia and

Russia, crushing Prussia at Jena and Auerstedt. He then turned to

face Russia, fighting to a stand-off at Eylau ... and then to an

overwhelming defeat of Russia at Friedland. The Prussians lost

half of their territory in Germany when Napoleon created the Kingdom of

Westphalia and placed his brother Jerôme over it as king. With

the Russian Tsar, Napoleon was kinder in his victory, hoping to create

a friendship that could serve French interests in East Europe.

He now focused his thoughts on Britain, attempting to tighten his

"Continental System" of a blocking of all commercial relations with

Britain on the European Continent in an effort to cripple the British

economy and thus force Britain to finally fall under his rule.

But his effort to discipline Portugal (which had not been honoring the

boycott) drew him into the Iberian Peninsula of Spain and Portugal ...

where Spanish sensitivities to French intervention in the region's

political affairs drew him into a draining round of local fights with

Spanish guerrilla bands. His appointing his brother Joseph as

King of Spain (1808) in the hope of getting on top of the situation

there only made matters worse. He was forced to position

permanently a huge portion of his army to hold things together in Spain

... while he faced continuing threats to France elsewhere.

Indeed, the British under Wellington would take advantage of Napoleon's

troubles elsewhere by sending their own troops to Spain and gradually

ending French control there.

At this point (1809) Austria (part of the "Fifth" Coalition) re-entered

the fight against France, actually defeating the French in a battle at

Aspern ... but then being devastated by the French in a second

engagement at Wagram. Politically this resulted in a huge loss

for Austria. But at least peace would reign in Europe for the

next few years.

But the Russian Tsar was being pressured by his nobles to join with

Britain in an offensive against the French ... in the hope of retaking

Poland. Napoleon heard of these plans and instead decided to take

the initiative. Thus in 1812 he headed a French army of nearly

half a million troops into Russia. A big mistake! The

Russians fell back instead of offering direct resistance to the

invaders (except at bloody Borodino) destroying their own crops and

animals to keep the French from securing food for their troops.

Napoleon made it all the way to Moscow just as the harsh Russian winter

set in ... finding nothing in this abandoned and burned-out city to

mark this as a victory. The Russians simply would not

surrender. After five weeks of pointless occupation, and with

political problems brewing back in Paris, Napoleon decided to

withdraw. The retreat was so ruinous that less than one-tenth of

his army made it back alive to France.

Encouraged by Napoleon's failure in Russia a Sixth Coalition was formed

against him in 1813. Once again Napoleon, with a rebuilt army,

humiliated the Coalition at Dresden. But the numbers were against

him, and a few months later at Leipzig, Napoleon's army was

crushed. Humiliating terms were put before Napoleon, which he

delayed too long in accepting. Napoleon attempted to hold off

with a number of smaller engagements ... but he was running out of

soldiers. Finally the French Sénat took action in deposing

him. Napoleon now had no choice but to accept exile to the Island

of Elba (off the Italian coast) which he was allowed to continue to

rule as "emperor."

The victorious allies then reinstated in France the Bourbon monarchy

under Louis XVIII. Their hope was to put this whole 25-year

nightmare of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire behind

them and move back to business as usual. That was not to

be.

The Battle of Waterloo (1815)

In early 1815 news reached the allied delegates to the Congress of

Vienna that Napoleon had escaped from Elba and was gathering a new

French army in order to restore his French Empire. Britain,

Russia, Austria and Prussia were determined to put to an end forever

Napoleon's efforts to undo their work. By the summer, Napoleon

was ready to act against this new coalition, moving into (today's)

Belgium where outside the village of Waterloo he met the combined army

of Britain (under Wellington) and Prussia (under Blücher) ... and went

down in defeat. This time he was exiled to a small island (St.

Helena) in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean where he would remain until

his death six years later.

For more (much more) on Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars For more (much more) on Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars

7He

had also promoted himself earlier that year from the position as

President of the Italian Republic (since 1802), to now being King of

Italy.

The Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (reigned 1799-1815) finally settles France down ... before spinning the country outward in a campaign of European conquest

Napoleon at the Pesthouse in Jaffa

Napoleon on Borodino Heights

Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau

Napoleon's retreat from Moscow - 1812

THE AMERICAN AND FRENCH REVOLUTIONS COMPARED |

|

The American Revolution

Actually the American Revolution was no revolution at all, socially and

culturally speaking. It was revolutionary only in the sense of a

people rising up against their feudal king and succeeding in the short

span of a half-dozen years in securing their full independence as a

people. But America before the war and America after the war was

pretty much the same. 150 years of colonial self-rule since the

early 1600s had taught the Americans how to take care of themselves –

from building their own communities of homes, barns, workshops, schools

and churches ... to defending themselves from their local enemies, the

Indians (and occasionally the Spanish and the French). The

American "Revolution" occurred simply because an English king decided

to take away the personal liberties to which these Americans were well

accustomed. Their "Revolution" merely confirmed those liberties

... not create them as if they were new.

Even the Constitution they drew up in 1787 was a

rather limited political document, more a treaty among thirteen

independent states providing for cooperation so as to keep them from

splitting into little contending states, vulnerable to the continuing

imperial designs of the great powers of Europe. The Constitution

did not provide for a "government" such as we think of today when we

think of an institution which governs over people. Government in

that sense remained a strictly state and local affair (except

occasionally in times of war) ... up until the mid-1960s when President

Johnson and his "Liberal"8 brain trust decided to build a "Great

Society" which would govern from Washington, D.C. on virtually every

matter affecting American life. But that took nearly two

centuries to come into existence after the American "Revolution.'

The French Revolution / Napoleonic Empire

But what happened in France in follow-up to America's Revolution was

indeed truly "revolutionary" in every social-cultural respect.

The French Revolution killed the feudal system that had governed Europe

for a thousand years. And the Napoleonic Empire put in its place

a new system by which the masses of common people, not the select lords

and ladies, formed the foundation of European social power. The

French armed their people ... and in the process of fighting their own

wars gave real strength to the notion of the "people" – or (as this new

concept would develop through the 1800s) the "nation."

It was not just France that the Coalition powers of Britain, Austria,

Prussia, Russia, Spain and Sweden were fighting. It was their

Revolution they were trying to undo. They were quick to support

the French Bourbon monarchy that the French Revolution had nearly

decapitated.

In many ways Napoleon was one of them ... another

monarch. But he was a monarch who stood for the ideals of the

European Enlightenment. They were opposed to those ideals more

than the person of Napoleon ... though it was hard to differentiate the

two, Napoleon had so completely embraced personally Enlightenment

ideals.

For this reason, at first many of the European upper-middle class

(university educated) intellectuals were very supportive of the French

Revolution ... even at first of Napoleon. But in bringing the

idea of the sovereign "people" forward, the French Revolution also

raised the question of how to define those people. Though most of

the European aristocracy spoke French among themselves, the common

people spoke a multitude of languages ... which carried the songs, the

poetry, the stories, the dreams of the common people. And thus

local language became an important factor in defining "the

people."

In this way "nationalism" was born ... aided greatly by

the cultural arrogance of the occupying French governors and their

troops. Thus the idea of "German" and "Italian" began to take

place, to be joined by the already rising sense of being English (but

also Irish), Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Swedish, Polish, etc.

Thus feudal Europe was entering a truly revolutionary social phase ...

one which would bring forth the pride of the European nation ... but

also the tragedy of the national bloodying of World War One (1914-1918)

... and the consequent undermining of European dominance throughout the

world.

8There

is considerable confusion over the term "Liberal" in today's America.

Originally the term meant liberal in the sense of being free ... in

reference to being liberated from the autocratic governments of Europe

which attempted to control all social life from above by higher

authority. Liberal meant full grass-roots self-government of the

people themselves. In America today it means almost the opposite

... where a Liberal is actually what Europeans would term a Socialist,

meaning someone who believes that society would work better (or more

"progressively") under the extensive guidance and control of high-level

government experts ... such as President Johnson proposed in the mid-1960s with his

"Great Society" – an idea which American "Liberals" have supported ever

since.

Go on to the next section: The "Modernizing" of the West

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | | |

The American "Revolution"

The American "Revolution" The French Revolution (Mid-1770s to the

The French Revolution (Mid-1770s to the The American and French Revolutions

The American and French Revolutions