7. EXPANSION ... AND DIVISION

JAMES POLK AND THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR

CONTENTS

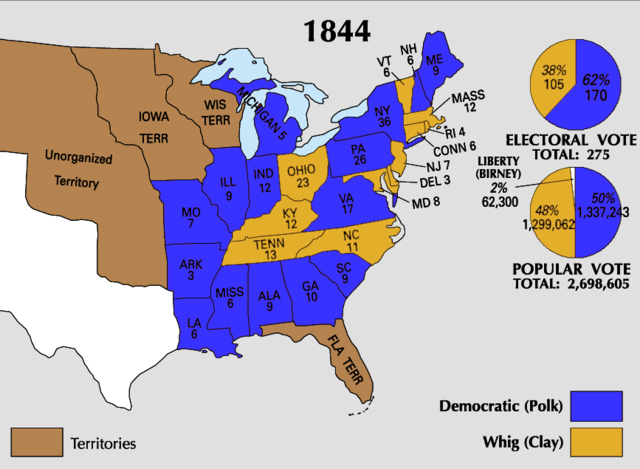

The 1844 elections The 1844 elections

The Mexican-American War The Mexican-American War

(1846-1848)

The moral impact of the Mexican- The moral impact of the Mexican-

American War

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 253-259.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1840s |

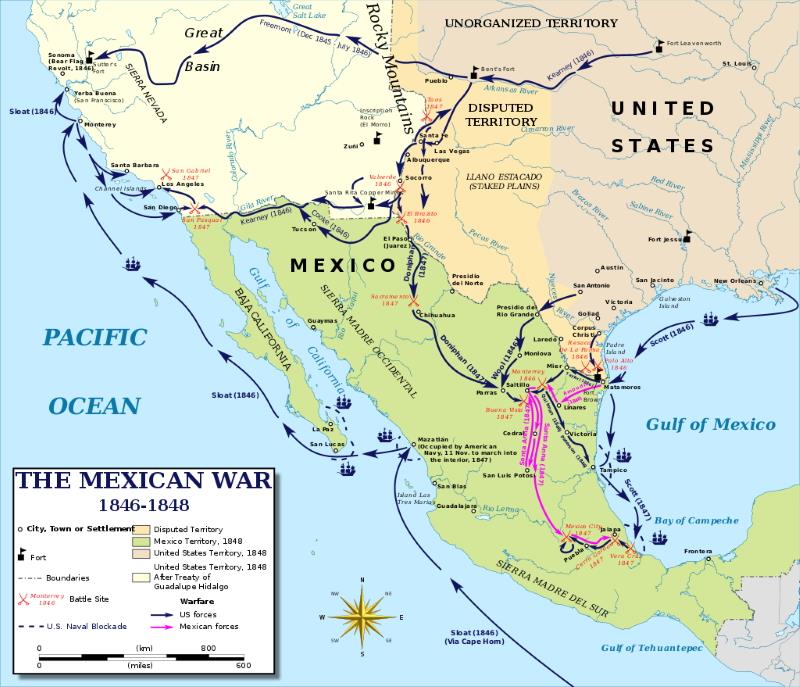

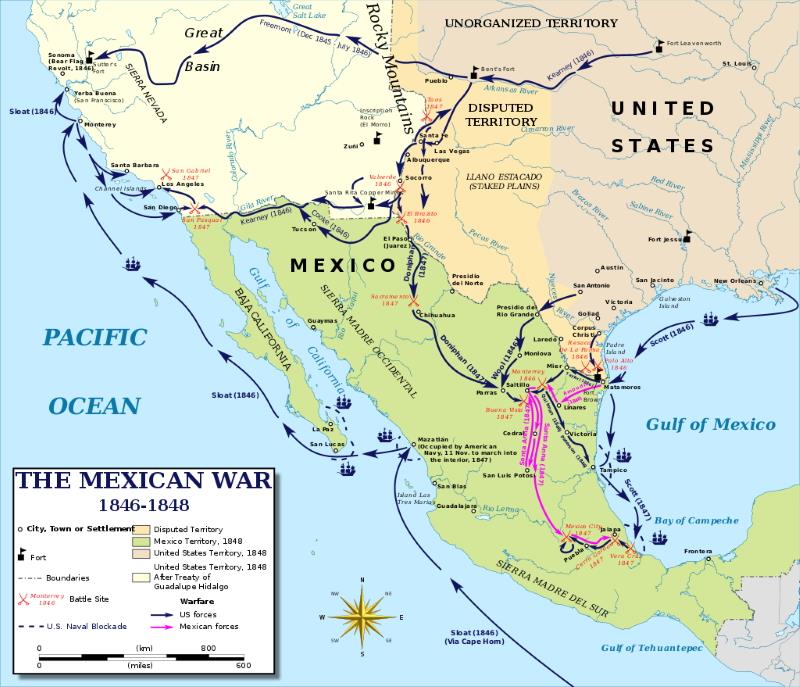

The Mexican-American War

1845 As outgoing President (Polk had just won the 1844 election), Tyler pushed Congress to invite Texas to become part

of the Federal Union; Texas agrees (Dec) ... infuriating Mexico

1846 Texas-Mexico border questions greatly complicate the issue (troops from both sides moving into the border

region) and finally Polk gets Congress to declare war (May)

Americans

are quick to seize Mexican lands West to the Pacific Ocean (June)

Then

General Zacharly Taylor moves his troops into Mexico ... joined by

Winfield Scott's troops

1847 American troops are able to enter Mexico City (Sep) as Santa Anna flees; the war is over

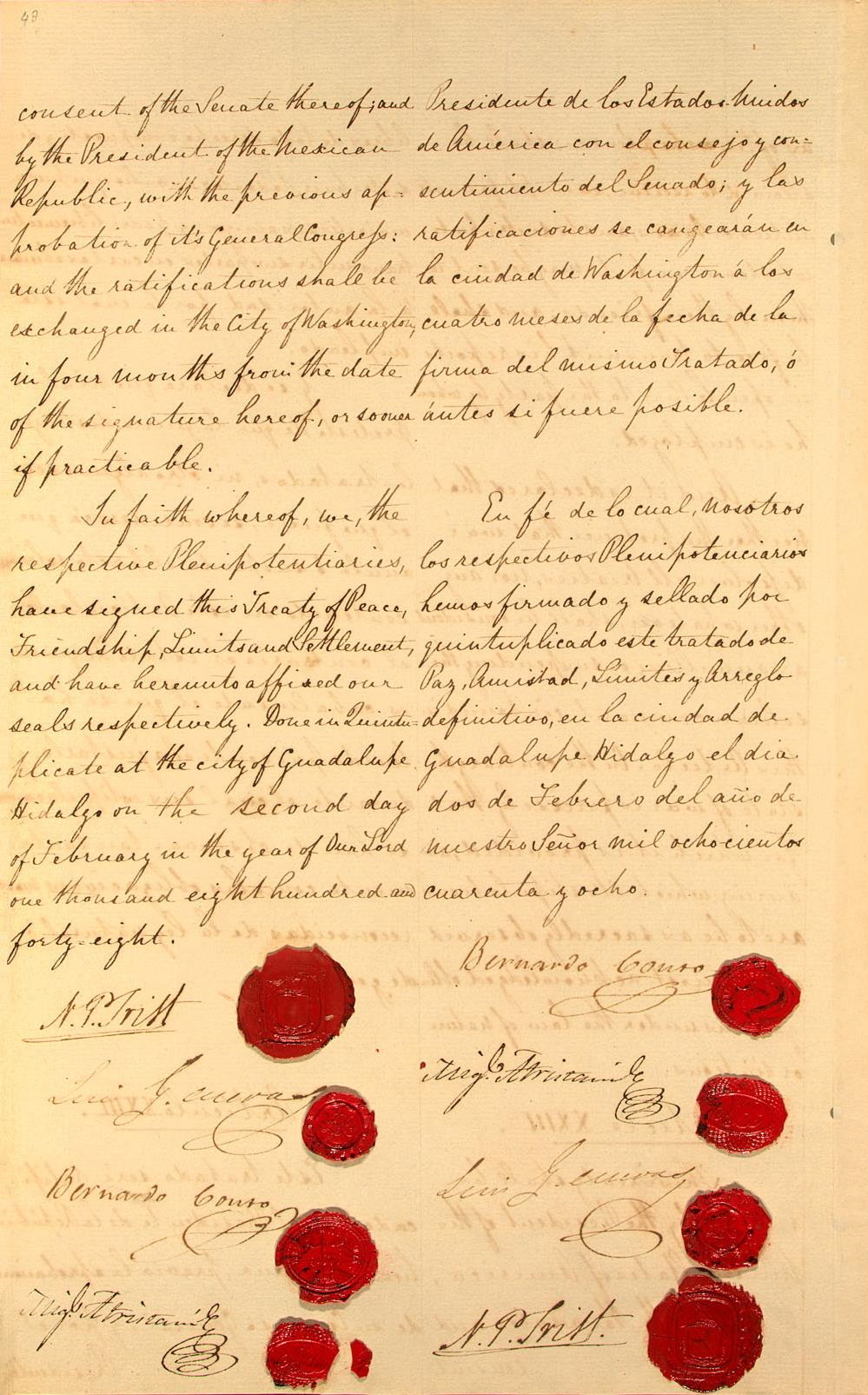

1848 America agrees (Jan – The Guadalupe Treaty) to pay Mexico $15 million for Texas and the Western lands America now possesses ... resolving the issue somewhat

|

|

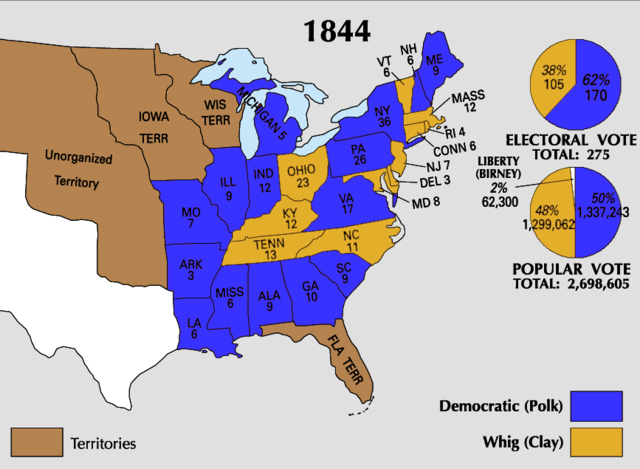

The 1844 elections: Clay vs. Polk, vs. Birney.

In the 1844 elections, the Whig nominee Clay found

himself up against the Democrat (Tennessean) James Polk. President Van

Buren had alienated so many within his own Democratic Party that the

party's presidential nomination ultimately had gone to Polk, something

of a dark horse that had not been one of the early frontrunners in the

party. Polk subsequently ran his campaign on the promise that if

elected he would admit both Texas and Free-Soil (no slavery allowed)

Oregon as new states, thus offsetting some of the northern opposition

to the admission of Texas as a slave state.

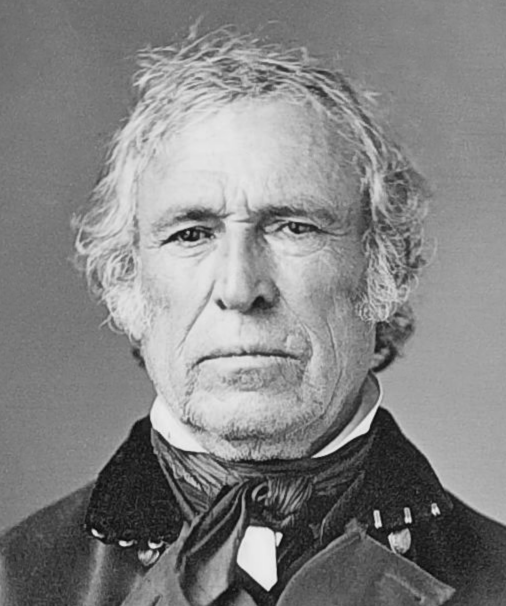

Clay, his third time as a presidential

candidate, ran on the typical Whig platform of Clay's own American

System: protective tariffs to promote American industry, a strong

central bank, and the building of the commercial infrastructure of

canals and roads. These all tended to favor the conservative interests

of the up-East financial-industrial class, and undercut his support

among Westerners and Southerners.

But a "third-party-spoiler," the Liberal

Party's James Birney, was also running, drawing support away from those

who otherwise would have voted for Clay. This would prove ruinous for

Clay. So it was that Polk handily won the electoral vote, including

even a large number of northern states.

Henry Clay – Whig

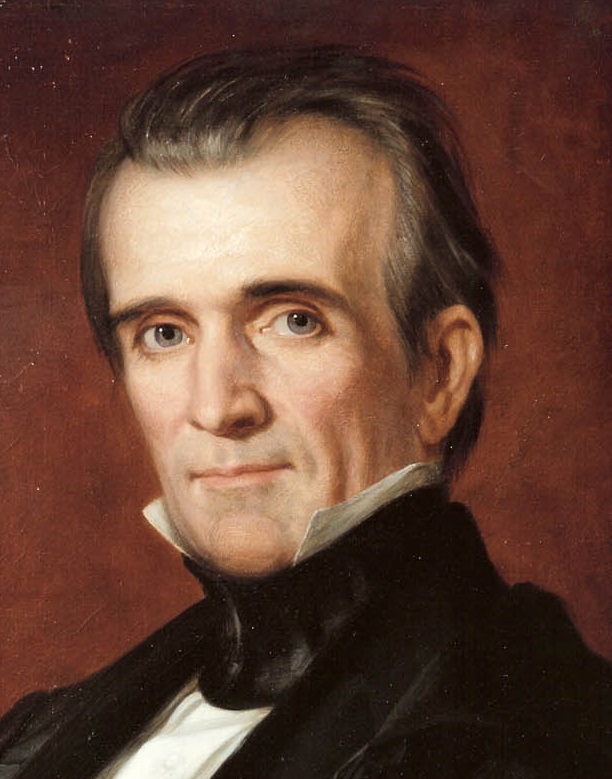

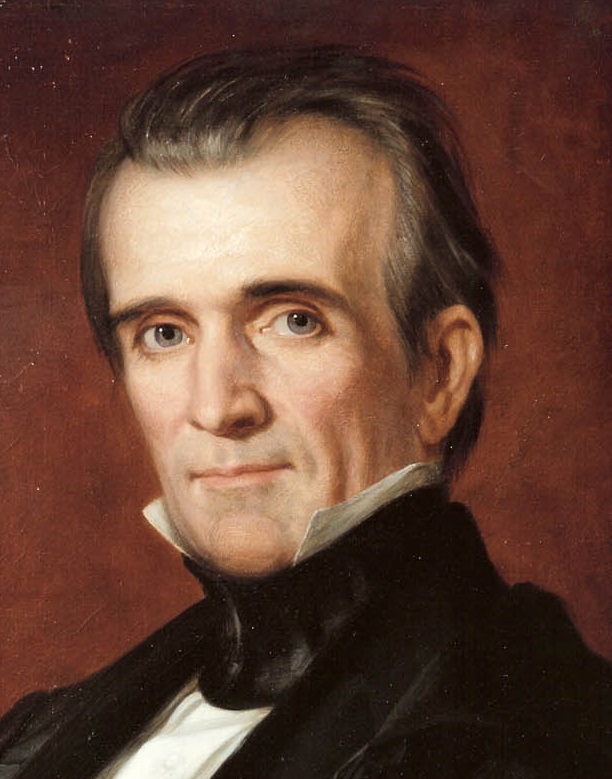

James Polk – Democrat

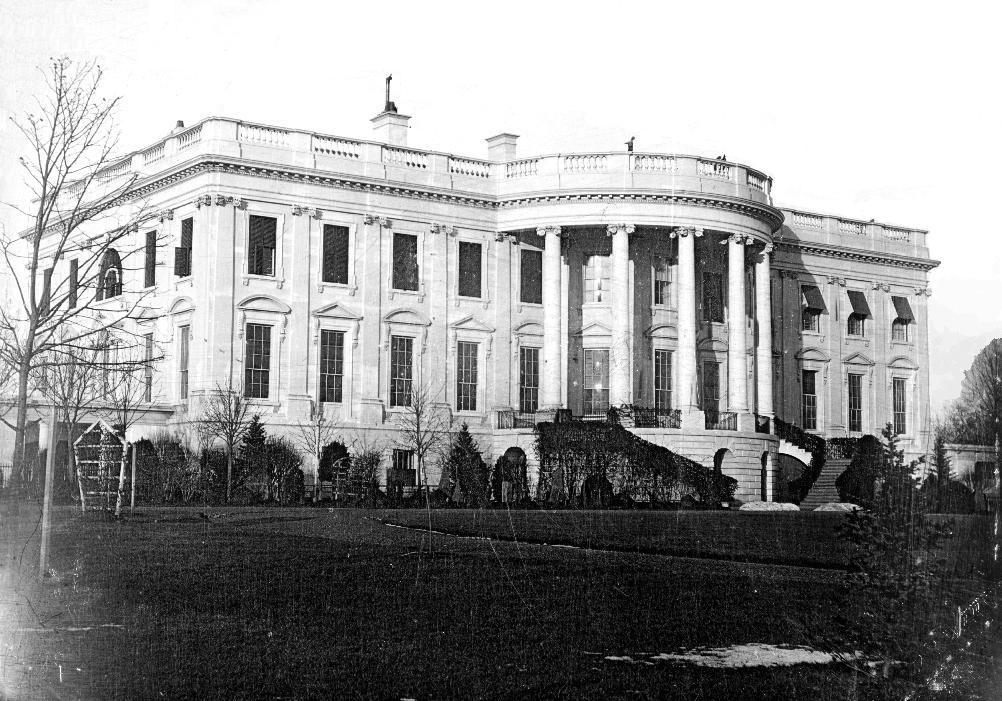

The U.S. Capitol – 1846

The White House – 1846

THE

MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR (1846-1848) |

|

The admission of Texas to the Union

But as a lame-duck president, Tyler, sensing that

the election had served as a referendum strongly supportive of the

admission of Texas as a new state, moved ahead in his last days in

office as president and proposed to Congress a resolution opening Texas

to membership in the Union. This was the final blow in undercutting his

Whig political base, causing the president to be expelled from his own

Whig party!

The Whigs fought the annexation with all

the strength they could muster. John Quincy Adams, who as a strong

anti-slavery voice in the House of Representatives had opposed bitterly

the admission of Texas as a new slave state, voiced this move as being

a devastating calamity for the Union. But like the Federalists before

them, the Whigs were up against a growing Manifest Destiny fever which

seized the country. Remembering the fate of the Federalists, they

voiced their opposition carefully.

But Whig opposition would not be enough

to stop the entrance into the Union of another, quite large, slave

state. Ultimately Tyler succeeded in getting Congress to authorize the

annexation of Texas, not by a treaty requiring a 2/3rds vote for Senate

approval (which would not have been possible due to the strong Whig

opposition) but instead by a mere joint resolution of both houses of

Congress, which required only a simple majority in both houses! Finally

the resolution providing for the annexation of Texas was signed into

law by Tyler on his last day in office.

And his presidential successor, James

Polk, would see the annexation completed when the huge slave state

Texas formally accepted the invitation to join the United States in

December of 1845 as its 28th state.

Steps toward the Mexican-American War.

Mexico had made it clear that it would

never accept the loss of its Texas province, particularly if it were

then absorbed into the United States. Then when the discussions between

the Republic of Texas and the United States started referencing as

Texas's southern border with Mexico not the Nueces River but the Rio

Grande – much further south and thus deeper into Mexico – the Mexicans

were outraged.

In many ways the new president, James

Polk, was something of another Andrew Jackson: a strong personality who

was unafraid of stepping on toes in order to get done exactly what he

wanted. He also knew that Mexico was furious enough over the admission

of Texas to the Union that war could easily develop between the two

nations. He was prepared for that possibility as well.

But also Polk was by every instinct the

lawyer who believed that it was better to work out a deal with

litigants than go to court. By those same instincts he was hoping he

could work out a deal with Mexico, perhaps purchase his way to a

settlement. He was prepared to offer Mexico millions in assistance and

even in purchase of Western territory itself.

He knew of course that the Mexicans

themselves were fired up for war and wanted satisfaction for their

bruised sense of honor. Money would not restore that sense of honor.

Americans themselves were also getting fired up for war. Thus war was

likely. But Polk wanted to make sure that if and when it occurred, it

would take place on America's terms, not Mexico's.

The situation was complicated further by

the fact that relations between the Americans and the British were

quite unresolved in the far West. The British claimed Canadian

territory along the Pacific Coast deep into the Oregon region. There

were rumors circulating that the British were interested even in

extending their imperial hold all the way into California and were

thinking about purchasing sparsely inhabited California from Mexico.

The Mexicans were possibly considering this as preferable to having as

northern neighbors more Americans, who also were eying that land. Thus

some kind of Mexican-English relationship was possibly building which

would have weakened the American hand considerably in any war with

Mexico.

Furthermore, though humiliated in the

Texas war of Independence, the Mexican military was considered to be no

joke of an army. European military experts in fact expected that in any

direct military confrontation with America, the Mexican army, huge and

well disciplined, would make quick work of the motley crew of American

militia and the rather small national army. Indeed, many were certain

that the superior Mexican army would quickly roll back the Americans

all the way to Washington, D.C.

Seeing the war clouds darken, in mid–1845

Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to move American troops into Texas

and position them on the Nueces River, waiting to see what might

develop. He also sent a small military group (sixty men) of explorers

under General John Frémont to Oregon through California (still part of

Mexico), whose larger purpose was a mystery to the Mexicans. Highly

suspicious of Frémont, the Mexicans ordered him out of California.

Then in early 1846 Polk sent an offer to

Mexico to purchase California and New Mexico. He also in April ordered

an American warship to move into the San Francisco Bay to protect

Americans living in California.

Meanwhile Mexico itself was undergoing

tremendous political turmoil (4 different individuals succeeded each

other in the Mexican presidency in 1846, 6 in the war ministry and 16

in the finance ministry). A big part of the problem was that the

Mexican leaders themselves could not agree on what to do in the face of

the growing possibility of war with America. Centralists demanded war;

Federalists requested negotiations. Back and forth the controversy

swayed, until the military party of Centralists seemed to have grabbed

firm control.

War is declared (May 11, 1846).

Polk then ordered Taylor to move his

troops all the way to the Rio Grande, where Taylor constructed a fort.

For the Mexicans this was the final insult, as they still claimed the

land south of the Nueces River and north of the Rio Grande as theirs.

In late April of 1846 they issued a declaration of intent to fight a

defensive war and sent a detachment of 2,000 Mexican soldiers to expel

the Americans from what they considered Mexican territory.

In the process, the Mexicans overwhelmed

a small patrol of seventy American soldiers in the disputed territory,

killing sixteen of the Americans. On May 11th, claiming that Mexico had

killed American soldiers on American soil (for that was the American

view on the matter of the territorial boundary), Polk asked Congress

for a declaration of war. The Democrat-dominated Congress obliged him –

though the Whigs, seeing this as playing to the advantage of the

Southern slave states, were highly opposed to this decision.

Action in Texas actually had taken place

even before the American declaration of War. Mexican and American

armies had met at the Rio Grande earlier in May, and the results were

disastrous for the Mexicans. From then on, the southern front in the

war would be fought in Mexico, not Texas.

California was next to become the scene

of battle. In June of 1846 Frémont returned to California to openly

invite a revolt (the Bear Flag Revolt) of Americans in Sonoma (northern

California). This all looked quite similar in character to the Texas

rebellion ten years earlier, except that the Californians moved

immediately to replace the California Bear Flag with the American flag.

Frémont's army moved south to capture Los Angeles, and was joined by

the army of American General Stephen Kearny, moving in from the East

across the vast southwest desert, who easily took San Diego. By January

of the following year (1847) the Mexicans were forced to surrender

their claim to California. England, meanwhile, had elected to stay out

of the conflict.

In the meantime, Taylor began to advance

his troops into Mexico from the northeast. His troops were a wild

collection of volunteers, undisciplined, and at times functioning more

like a drunken mob than an army (raping and pillaging as they went). It

took considerable effort for Taylor to finally be able to shape his gringos1 into a disciplined army.

Taylor's first major encounter with the

Mexicans was at the city of Monterey (September 1846) where his army,

unused to urban warfare, ran into stiff resistance from Monterey's

troops and citizens. Ultimately to achieve a win, Taylor had to resort

to an armistice allowing the Mexican soldiers to leave the city

peacefully. Technically this marked an American victory. But Polk was

furious about such a weak showing by Taylor.

Meanwhile Santa Anna had again seized control of the Mexican government

and had come out to fight the Americans. In February of 1847 Taylor's

and Santa Anna's armies met at Buena Vista – with the Mexican army over

three times the size of the American army. Santa Anna was able to

surround Taylor's troops and inflict huge casualties on them, though

the Americans held their position. Both sides were exhausted. But Santa

Anna got news of political troubles back in Mexico City and had to

abandon the conflict, leaving Taylor in control.2

During all of this confusion the Comanche

and Apache Indians had been conducting raids on the Mexicans. Thus as

American soldiers advanced from the northwest toward Mexico City, they

found the countryside deserted and the towns unwilling to resist the

advancing Americans.

At the same time, Americans under naval

Commodore Matthew Perry were fighting the Mexicans along the Mexican

shores and tributary rivers of the Gulf of Mexico, inflicting

humiliating defeats on the Mexicans as they went.

Polk now turned to General Winfield Scott

(working closely with Perry) to lead an assault in March of 1847 on the

Gulf of Mexico coastal town of Vera Cruz, to reduce the walls

protecting the city in preparation for a massive amphibious landing of

American troops whose ultimate destination would be Mexico City.

Seriously outnumbered by this attacking American force, the Mexicans

were only able to hold out a dozen days before having to surrender Vera

Cruz to their American attackers.

The Americans then headed west to Mexico

City and, after overcoming stiff resistance to the north of the city at

Chapultepec (including the brave fighting of the Mexican students at

the military academy located there), were able to enter the city in

mid-September. Santa Anna was overthrown and fled the country. The

Americans were now in total control of the Mexican political heartland.3

The question then arose: what to do with

Mexico? Some political voices speculated that the Mexicans themselves

might greet annexation to the United States gladly. The Whigs were

however strongly opposed to the annexation of Mexican territory,

fearing it would only expand the political weight of the pro-slavery

portion of the nation. But in fact, neither the Mexicans nor most

Americans had any interest themselves in such a union.

1There is some dispute about the origins of the term gringo. Some claim that it originated from the song that the Americans sang, "Green Grow the Lilacs," as they marched through Mexico!

2Taylor would make much of this victory in his successful bid for the U.S. presidency in 1848.

3Marines

were put on guard duty at the Mexican National Palace, the "Halls of

Montezuma," completing the opening line of the Marine's hymn: "From the

Halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli..." [from Mexico City to

the shores of the Barbary Pirates].

The Battle of Palo Alto (May 9, 1846) fought in the region between the Nueces River in the North (Mexico's understanding of the Mexican-Texas border) and the Rio Grande (the American view on where the border lay). About 2,200 U.S. forces under Zachary Taylor took on General Arista's force of 3,700 in which American artillery devastated the Mexican army.

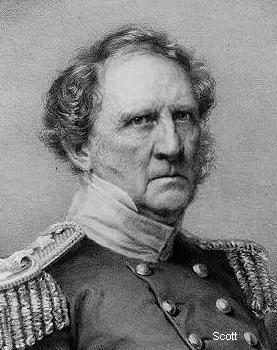

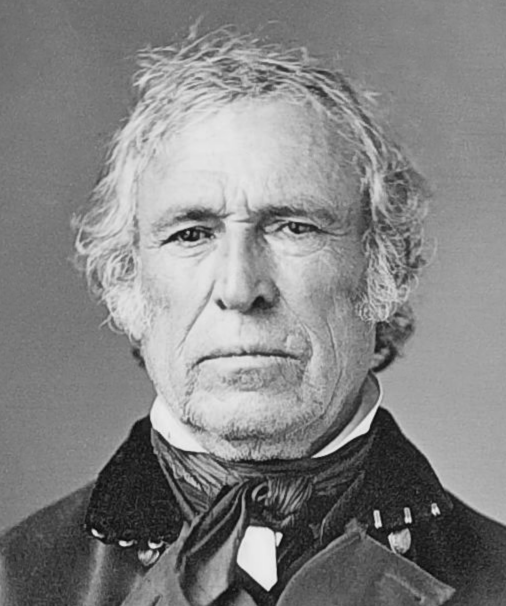

General Zachary Taylor

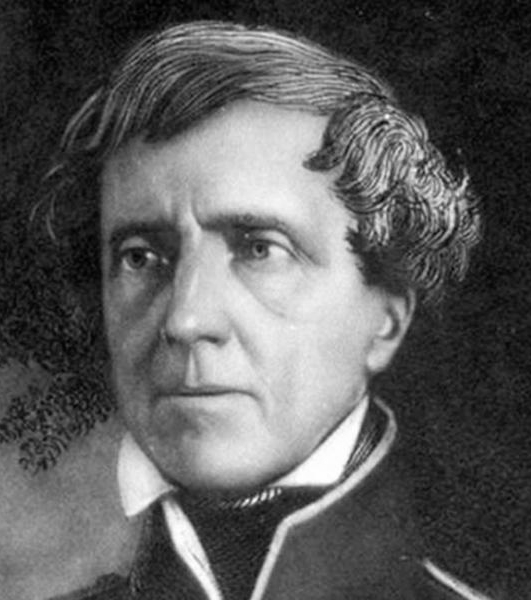

John C. Frémont

Stephen Kearny

Commodore Matthew Perry

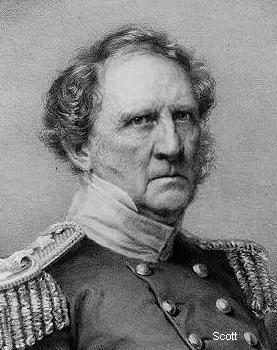

General Winfield Scott

Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright's Atlas of

the Historical Geography of the United States (1932)

Wikipedia

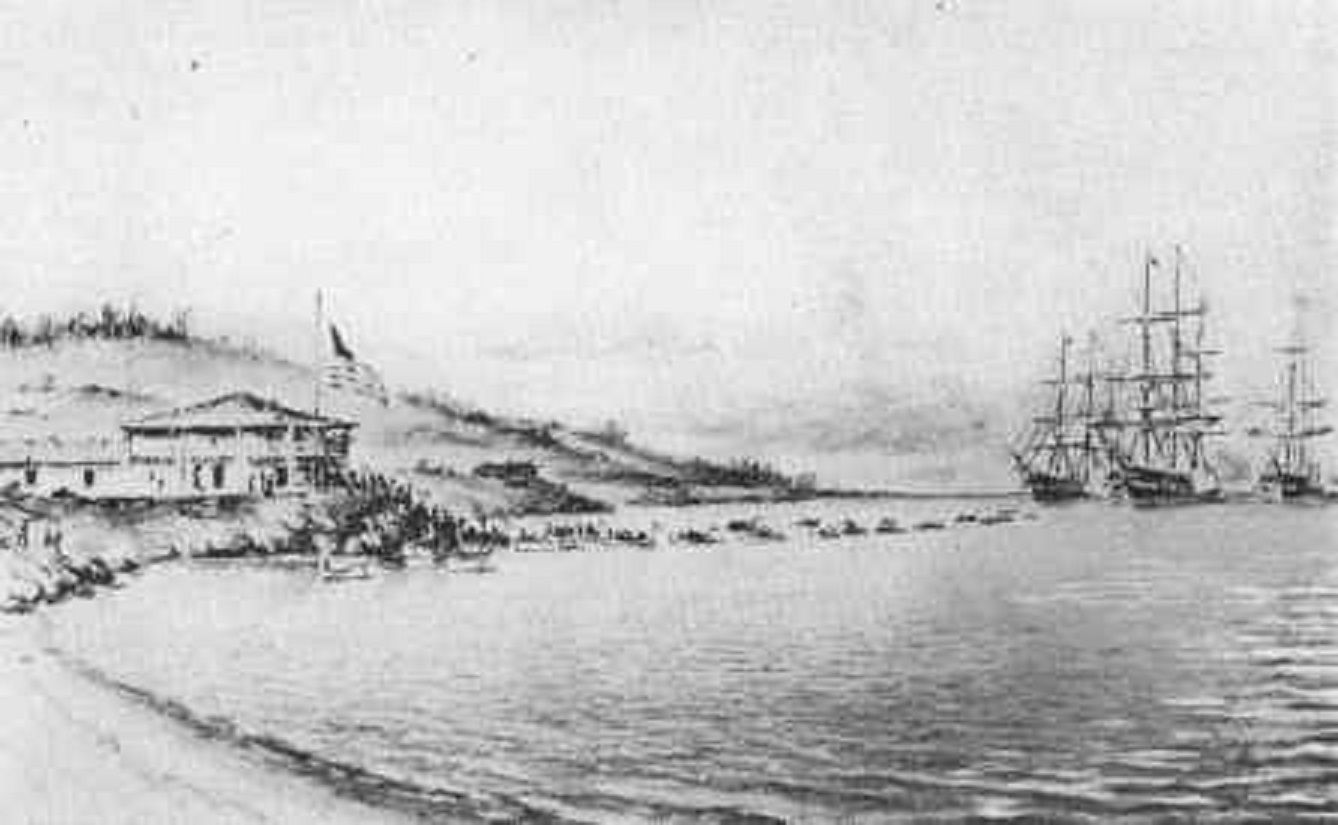

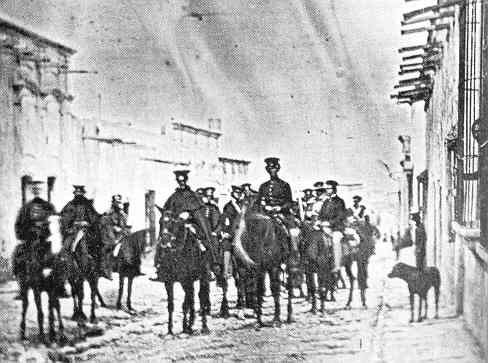

Commodore John Sloat's forces take Monterrey (July 7, 1846)

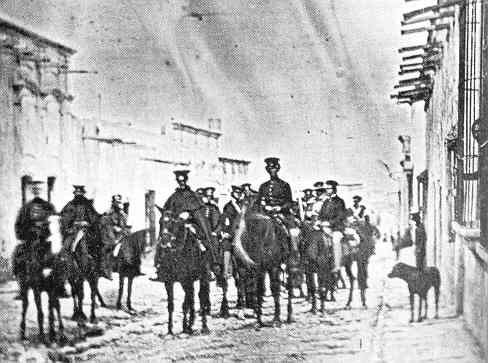

February 1847 – U.S. troops under Zachary Taylor entering Saltillo (an early

photograph)

Americans attack the Mexican position at Chapultepec (September 13, 1847). With Santa Anna fleeing, at this point the Americans were in full control of Mexico

General Scott takes command of Mexico City

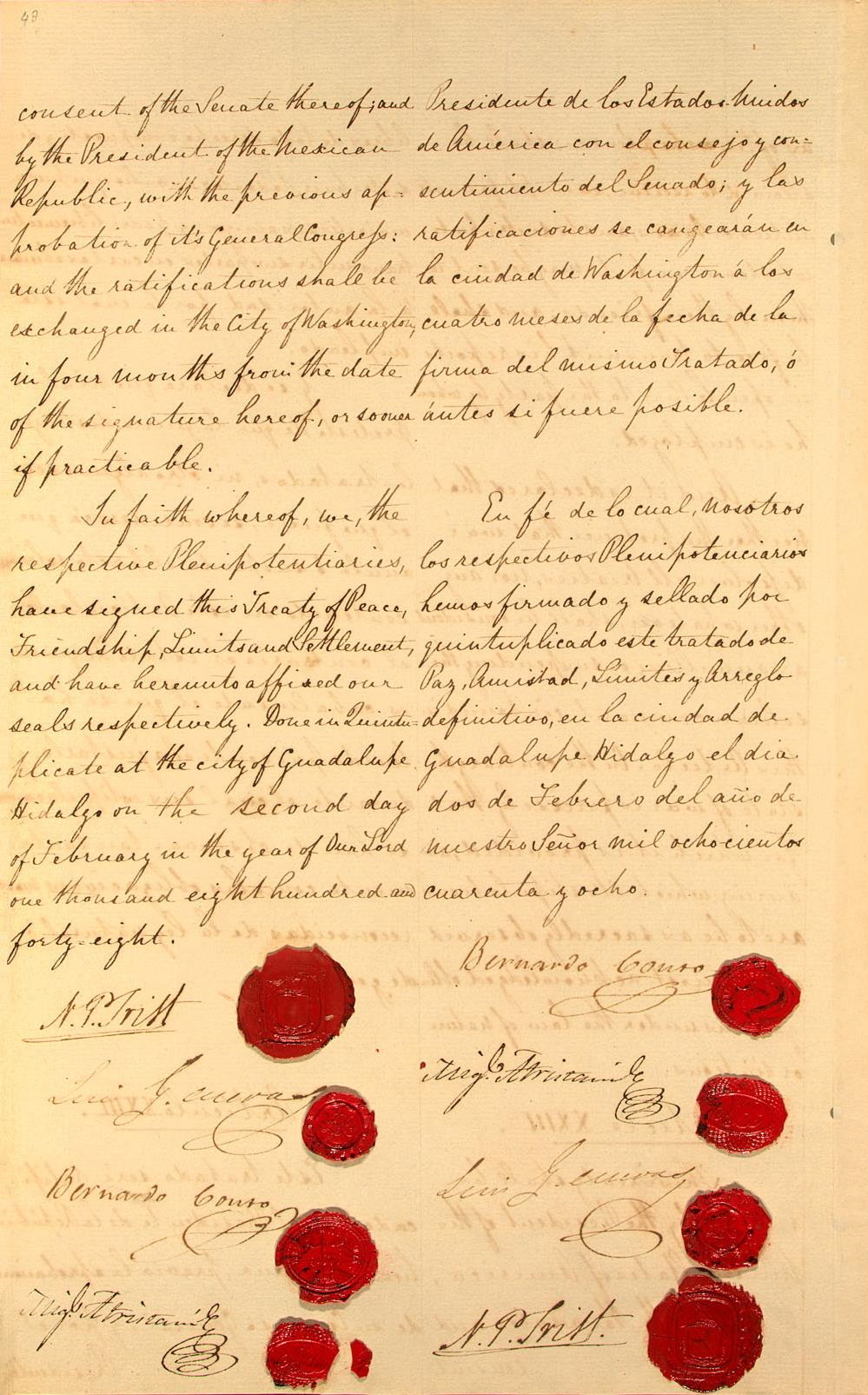

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo (February 2, 1848)

awarding Mexico $15 million for the territory lost to the United States

THE MORAL IMPACT OF THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR |

|

Many of the Whigs of the American North had viewed

the Mexican-American War as little more than an effort of the South to

strengthen its political position in Congress by adding newly conquered

territories, and thus subsequently future states, to the pro-slavery

roster. Most notable in their opposition to the Mexican-American War in

this regard had been Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams. They employed

every argument possible concerning the moral degeneracy of the

imperialism America had inflicted on its Mexican neighbors. However

most Whigs certainly encouraged the idea of American expansion westward

– as long as any newly acquired territories remained in the Free-Soil

category.

Then in August of 1846, during the debate

approving the $2 million in appropriations underwriting potential

negotiations with Mexico (which it was hoped at the time might end the

war) the gauntlet was thrown down in Congress by Representative David

Wilmot. He wanted attached to the appropriations bill the proviso that

would ban slavery in any of the lands that the Mexicans might turn over

to the Americans (the Mexican Cession) as a result of a much hoped-for

negotiated peace settlement. The bill passed in the House, but failed

in the Senate when Congress dismissed without considering the

resolution. When Polk later that year made another request for funds to

negotiate a peace settlement with Mexico the Wilmot Proviso was

reintroduced and hotly debated. However as debate developed, an

additional demand was added the following year that the prohibition of

slavery be extended to any new territory acquired by the United States.

Tempers were now hot.

Then Alabama Representatives proposed a

counter-resolution which would leave the slavery issue to the

individual territories to decide (building on the philosophy of the

sovereignty of the states, or states' rights). The measure failed to

pass, but united the Southern representatives into a strong regional

bond, one that would build and become the main political identifier

among the members of Congress.

America's major political division now followed not the more

traditional Whig/Democratic Party lines, but ominously North/South

regional lines. The parties themselves were splitting into North-South

factions, especially as the Wilmot Proviso kept getting introduced time

and again in the North's hope of finally forcing the end of slavery on

the South.

Finally, with the American military

victory in Mexico City, negotiations got underway in January of 1848 at

the town of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and within a month the two sides agreed

on terms: Mexico would receive $15 million in payment from America for

the acquisition of California, Texas to the Rio Grande, and the

territory in between (which would eventually become New Mexico, Arizona

and Utah.)

John Quincy Adams' death,

and the finalizing of the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty

When the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty was

submitted to the Senate for ratification in February, the Whigs were

bitterly opposed to any affirmation of the Mexican-American War and its

outcome because of the blatant imperialism involved. Even with the

revealing of the generous terms offered to and accepted by Mexico in

the negotiations of 1848, a storm erupted. Certainly the generosity

undercut some of the imperialist argument, though others were appalled

at just that generosity. But mostly the eruption occurred over the idea

of a number of potentially new states in the Southwest being lined up

for statehood and how this would tip the balance in the growing

North-South split over slavery. Leading the attack on the treaty was

the distinguished Whig senator from Massachusetts, Daniel Webster, the

Great Orator.

Then in the middle of discussions going

on in the House, John Quincy Adams was felled by a heart attack,

bringing the proceedings to a halt over the next days as the nation

stood watch over the last man with personal connections with the

Republic's Founding Fathers, and who himself had come to grow greatly

in the esteem of his Congressional colleagues because of his cool wit

and sharp insights. When he died on the 23rd (of February) the nation

mourned.

The effect was to sober the proceedings

in the Senate, which in early March finally moved to approve the

Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty, 38–14.

The size of the financial award offered

to Mexico for the loss of its territory still caused some to question

exactly who it was that had won, and who had exactly lost the war! But

it was a wise move, giving a degree of fairness to the war's outcome,

because Mexico might otherwise have continued to harbor a deep

resentment over a total loss – such that Mexico would have been tempted

to renew the war at a time when America was less able to fight, as

would have been the case when America fell into its savage Civil War

thirteen years later.

Adams

and Clay had been strong opponents of the war with Mexico ... seeing in

it only ugly imperialism. But in general the Whigs were

supportive of the war.

The Wilmot Proviso

Making

the situation even more complicated, in 1846 Pennsylvania

Representative David Wilmot attached his "proviso" on the bill

authorizing payment to Mexico for their loss of Western land ...

requiring any territory acquired in the war be automatically "Free

Soil" (no slavery). Tempers now got very hot.

|

David Wilmot

| Then

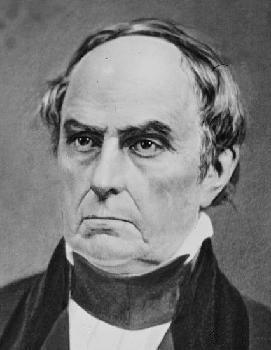

with Adam's death in 1848 ... Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts

took up the anti-imperialist role as the leading opponent of the

Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty finalizing Mexico's territorial loss (but

financial gain) in the West

|

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster

Go on to the next section: "Westward Ho!"

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | |

The 1844 elections

The 1844 elections

The Mexican-American War

The Mexican-American War The moral impact of the Mexican-

The moral impact of the Mexican-