7. EXPANSION ... AND DIVISION

AMERICA AT MID-CENTURY

CONTENTS

The widening social-cultural gap The widening social-cultural gap

between the North and the South

The North The North

The South The South

The Compromise of 1850 The Compromise of 1850

Glimpses of mid-century life in America Glimpses of mid-century life in America

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 174-191.

THE WIDENING SOCIAL-CULTURAL GAP

BETWEEN THE NORTH AND THE SOUTH

|

|

Behind the moral-legal battle in Congress, in the

press, and in the pulpit stood a stark social reality that was forcing

both North and South into ever more inflexible positions as the two

sections of the country faced each other. A big part of the problem was

of course the slavery issue. But there were other issues that were

pushing the two sections of the country further and further apart –

also in part related to the slavery issue but more importantly related

to the way that the social-cultural dynamics of the two regions (with

the young West beginning to form a third part of the social-cultural

distinction) were rapidly unfolding. Both key sections of the country

were heading down very different socio-economic paths. This would only

add to the inability of the two main sections of the country to

understand or even just work with each other.

|

|

The North was prospering in a way that the South,

despite all its romantic ideas of the elegance of Southern plantation

life, could not match in terms of economic achievement. An observer of

life in the North would have been quick to note all the infrastructure

recently completed or under construction in the North: roads, canals

and railroads. True, these were also developing in the South, but at a

much slower rate than in the North. For each mile of track laid out for

railroads in the South, three miles were being constructed in the

North. And even at that, the Northern lines tended to run East and West

linking the industrial East closely with the expanding Western

frontier. Comparatively few of the roads ran north and south to link

more closely the Northern half of the country with the South.

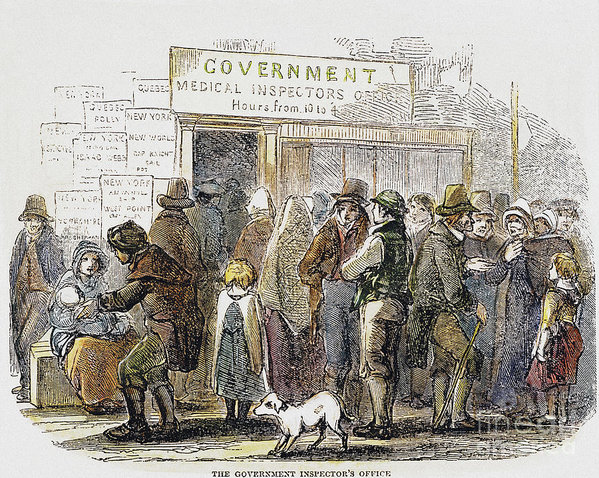

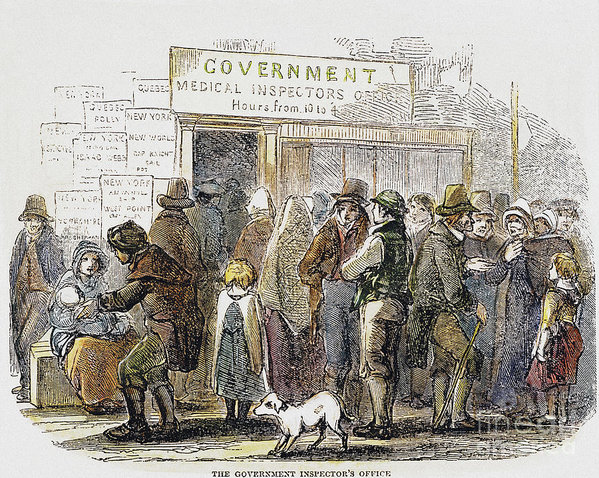

The coastal cities of the North (Boston,

New York, Philadelphia and even Baltimore) were bustling with new life,

much of it from European immigrants – who knew of the lack of economic

opportunity in the American South and thus headed from Europe to

America's Northern coastal cities.

Much of this new life coming to the North

was chaotic, fueled by a mass of Irish coming in from Ireland to escape

the horrible 1840s potato famine which was devastating their country.

The Irish came to all of the major cities of the North (but also the

rather Catholic New Orleans in the South), disrupting the calm

composure of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) America with their

Irish Catholicism and defiant Irish attitudes (they disliked the Anglo

world intensely for the highhanded ways the English had dealt with the

Irish crisis). Under the impetus of this Irish invasion, New York City,

for instance, became a very vibrant but also a rough place in which to

live and do business, with its tough neighborhoods, its Irish gangs,

and its corrupt political wheeling and dealing.

To the Irish, as would also be the case

for the Southern Italians and Sicilians who would flock to the country

early in the next century, social justice or law had little to do with

abstract Constitutional principles and political offices developed in

the long English tradition of both England and America. Instead, they

saw justice as vested in local urban bosses whose job in government was

to use the public treasury to take care of their own people. This Irish

paternalism was something the WASPs called corruption, but something

the Irish instead looked upon as being simply what any person had the

right to expect from government.

Further West into the heartland of the

American North were a large number of prosperous towns and cities –

large and small – and a multitude of small and well-kept farms dotting

the Northern landscape, from upstate New York and Pennsylvania in the

East to the fields of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and Kansas in the

West. All of this seemed to evidence solid success, even if only on a

small scale. There was a sense of inventiveness, of activity, of

progress, of confidence, of accomplishment, energizing the average

Northerner, who looked with pride on his or her work in the home, in

the field, in the shop.

Here too immigrants added to this picture

of vitality, notably the Germans and Scandinavians, who however blended

into the American Midwestern landscape more readily than did the Irish

in the American urban East. These northern Europeans were a more

communal group, especially the Mennonites and the Amish among them,

with a communal work ethic in many ways even more rigorous than the

highly individualistic Yankee work ethic of the Anglo North. Very

obvious material success followed their efforts, adding considerably to

the picture of rural prosperity in the North.

With the opening of the West all the way

to California, the Northern pattern tended to be the one that reached

into the new western territories. There were slaves that accompanied

some of the White newcomers to the West, though they constituted only a

small part of the population that crowded West to lay claim to the new

land. Slavery was not very useful in terms of the types of challenges

these newcomers faced in the new West. Indeed, frontiersmen were very

much the same individualists as the American Northerners, depending on

their own talents to survive and prosper in a highly competitive world.

|

The South could easily sense that the social

dynamics of a rapidly growing America were not going its way. A mood of

defensiveness was settling in on the South, still proud of its own

distinct cultural traditions – and the peculiar institution of slavery

that Southerners understood as constituting the foundation of it all.

The more the North pressed them on this matter of slavery the more

defensive they became in asserting the correctness of Southern social

values.

But sadly, despite all the romantic

swooning about the aristocratic plantation life in the rural South, the

material reality was not quite so elegant. To be sure there were

endless rounds of social visits (in the style of the British

aristocracy that Southerners attempted to duplicate), fancy balls, fox

hunts, etc. to occupy the privileged members of the plantation class.

But behind this pleasant facade stood a troubled reality. All of this

style stood on very shaky economic ground.

Cotton was king in the South, so much so

that for a long time there had been little interest in the production

of anything else. The amount of cotton that was produced was truly

vast, which meant that the price per bale produced would remain

competitively low. And it would reach an even lower low when cotton

production from India began to hit the world market. The plantations,

despite all the flow of cotton from their vast fields, were stretched

greatly to make an adequate profit able to sustain this luxurious lifestyle.

Urban life of course existed in the

South, but not generally of the bustling industrial variety found in

the North. Urban life was largely an extension of the all-prevailing

cotton economy. Towns such as Richmond, Columbus and Atlanta existed

mostly to collect and market the cotton of the rural areas immediately

around them (plus buy and sell slaves as an accompanying activity). On

the Atlantic and Gulf coasts cities such as Baltimore, Charleston,

Savannah, Mobile and New Orleans1 served as points of departure in the shipment of cotton to both British and New England textile mills.

Beyond cotton, the South was slow in its

uptake of the new industrial revolution. Steel was manufactured in the

South as well as the new tools and equipment to aid the economy of the

Cotton South, but not at the rate that it was being produced in the

North. Nonetheless, despite the smaller scale of the industrial

revolution in the South, rather substantial profits were to be had by

those who ventured into the competitive world of industry. Yet, the

status and prestige that Southerners sought was not assigned by

Southern culture to the world of capitalism. It belonged largely to the

romanticized world of the rural plantation. This was what truly slowed

the South in its economic development, at least in comparison to the

rapid industrial growth of the North.

Worse, no industrial invention had

provided an alternative to the hard reality that cotton was still

picked by hand. Cotton picking or chopping was a painful

finger-bleeding and exhausting back-breaking labor as well as often a

spirit- breaking activity, especially when accompanied by the whip of a

White overseer who had the responsibility of making sure that the Black

slaves under his charge met high-reaching production quotas.

Cotton farming did not make for much

happiness, not just for the slave but also for the White farmer who

could not afford slaves – as indeed the vast majority could not. The

Southern dirt farmer was by economic reality reduced to a material

standard of living hardly better than that of the slave, often

occupying shacks no more comfortable than the ones the slaves occupied

on the plantations. Of course the White farmer was free and the Black

slave was not. And on that difference the poor-White farmer staked his

entire self-image, to ensure that at least that small achievement would

not be taken from him by freeing the slaves and thus putting him on a

par with them. To protect that slim social distinction, he would be

willing to fight fiercely. Beyond that he dreamed the Cinderella dream

that he someday might find himself elevated to the social level of the

plantation elite whom he admired greatly (when he was not resenting

them). The dream sustained him somehow, even though there was virtually

no likelihood of it ever coming true.

As for the slaves, the tragedy of the

lives of the masses of these captive workers was almost beyond

endurance. It was not just that they were worked to exhaustion daily

but that they had no sense of the future ever holding anything positive

for them. In fact the future held the agonizing possibility of their

much-loved spouses or children being taken from them by a cash-strapped

owner who needed to sell them to pay off mounting debts. They were

treated like commodities, similar to cattle, and even bred like cattle

in order to build up their numbers as an economic asset, averaging in

value at that time around $1000 apiece if they were young, strong and

of a fertile age. And of course there were the young masters who could

not keep their hands off of attractive female slaves, humiliating both

slaves and White family at home with their sexual adventures, which no

one dared talk about even though it was widely practiced.

And connecting the slave and the slave

owner besides the whip was the regime of fear produced by the whip.

Although to ease its conscience White society attempted to dehumanize

the African slave, there was no way that the Whites could get past the

understanding of exactly how the slaves must truly feel about their

White masters. That link of fear was based heavily on the constant

concern about the possibility of a slave rebellion (such as the

successful slave rebellion in Haiti or the failed one of Nat Turner in

Virginia in 1831). The White South did not know what to do. To keep the

slaves in submission they would have to be unflinching in their harsh

discipline, which they knew darkened ever deeper the slave heart. Yet

to try to win slave hearts was to have to release that grip, which

could then explode the very social foundations of the South.2

1New

Orleans was actually the third largest city in America at the time.

Being the primary port of the huge Mississippi River watershed region,

its economy was much broader, of course, than just the cotton trade.

2White

Southerners were keenly aware of what had occurred in the French colony

of Haiti in which in 1791 the African slaves successfully rose up

against their French masters, defeated an effort in 1803 by Napoleon's

military to bring the slaves back into submission and ultimately in

1804 butchered thousands of French, forcing the French to finally

acknowledge the obvious: Haiti was free of White oppression.

|

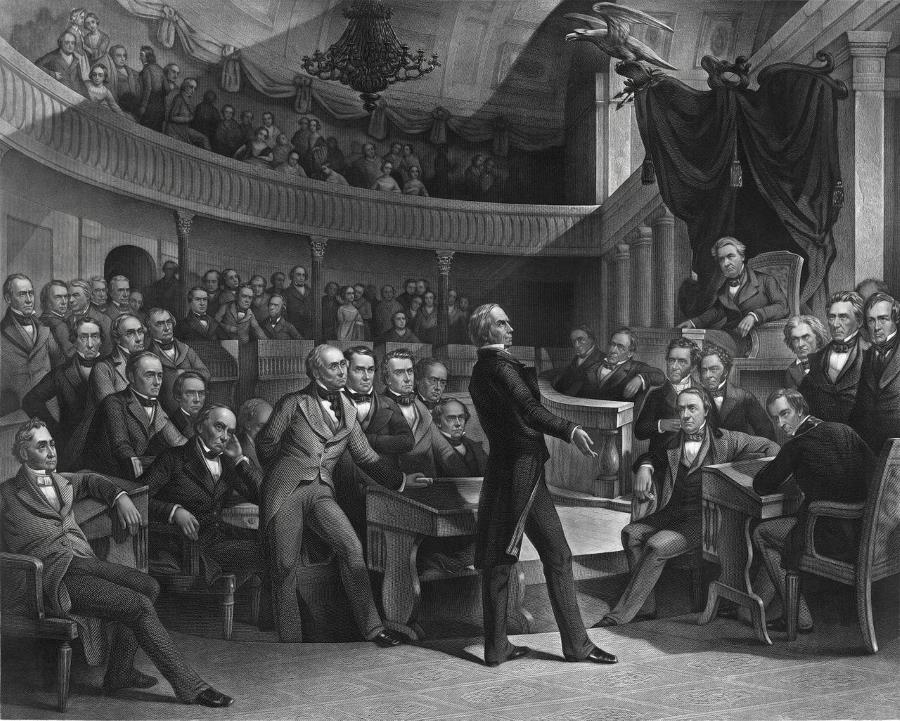

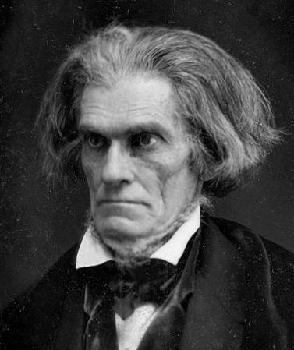

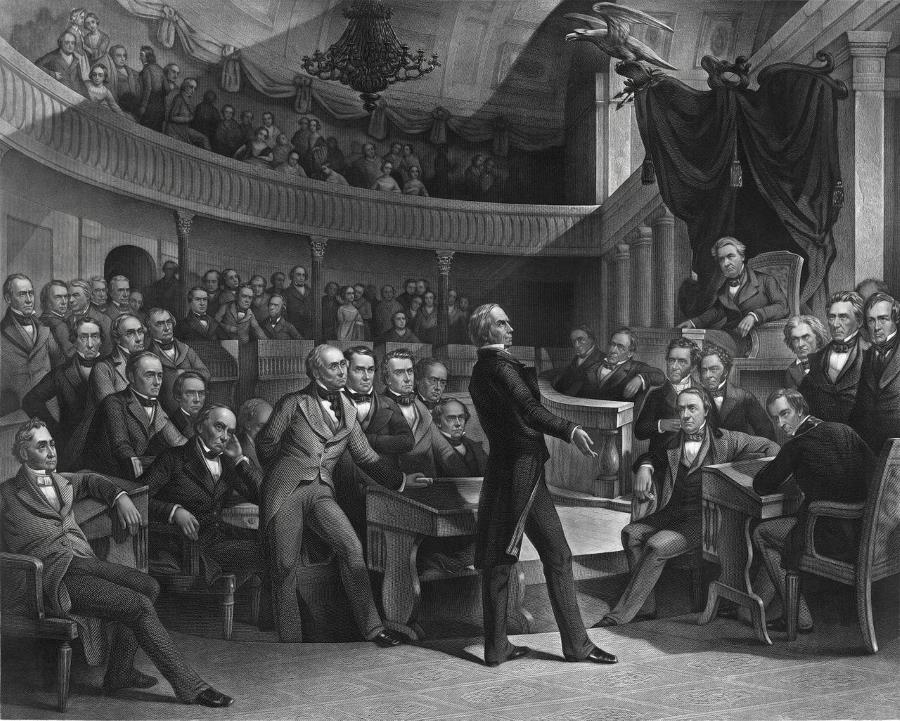

Henry Clay offering his 1850 compromise on the

slavery / statehood issue

|

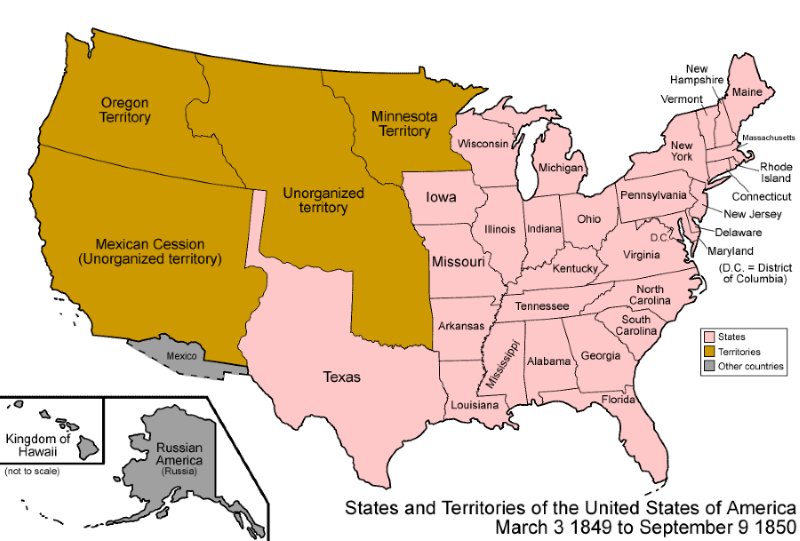

The American acquisition of the Western

territories resulting from the Mexican-American War had sadly and even

tragically merely presented another round in the North-South contention

over slavery and its extension westward. Promoted strongly by former

General and now President Zachary Taylor was the idea that California,

New Mexico and Utah should be brought directly into union with the

U.S., and not go through the stage of first being territories prior to

statehood. Furthermore all three future states had expressed the

intention of being brought into the Union as Free-Soil states. This was

not going to please the South.

At the same time, Southerners were

already talking about disunion. In late 1849 Mississippi called for

Southern representatives to meet the following year in Nashville. The

purpose of this meeting though unstated was obvious. They were going to

be gathering to discuss this very possibility. Needless to say, all

this created quite a stir in Washington.

When the candidacy of California was put

forward for statehood at the very end of 1849 tempers in Congress

flared. California was going to be admitted as a free state, ending the

tradition of maintaining a balance in the number of slave and free

states. The speeches for and against grew hotter as they took on very

biting moral accusations and moral justifications concerning the

central issue of slavery. One vote followed another as the two sides

deadlocked over the issue.

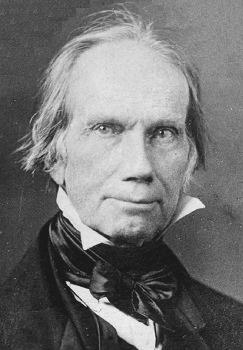

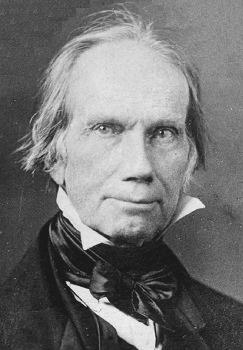

Once again the Great Compromiser Henry Clay (but now also a very weak old man) stepped forward in the Senate3

at the end of January (1850) to offer a set of proposals that he hoped

would smooth feelings on both sides, and ease the way for California to

achieve full statehood. The bill authorized the admission of California

to the Union as a Free-Soil state; it set the Western boundaries of

Texas, thus ending the contention Texas had with New Mexico; it

designated both Utah and New Mexico as territories, with each

possessing the right to determine how they would eventually enter the

Union, as free or slave states; it called for the end of slave sales

within the Washington, D.C. capital (though not the end of slavery

itself in the nation's capital); it required Congress to drop any claim

of authority to regulate the interstate trade in slaves; and it

required the North to return escaped slaves to their owners in the

South, a measure that was designed to calm the fears of the South about

Northern Abolitionist ambitions.

As compromises typically fare, it pleased

the moderates of both the North and the South but also succeeding in

angering the extreme wings of the Abolitionist Northerners and

increasingly independence-minded Southerners. Particularly upset were

the Northern Abolitionists to whom the idea of the forced return of

slaves that had escaped to the North was an abominable idea. They would

have none of it, even if it meant defying the nation's laws.

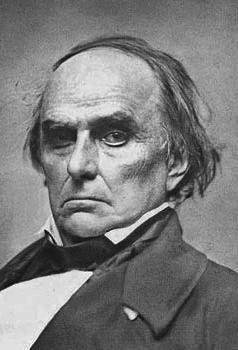

But not everyone in the South was

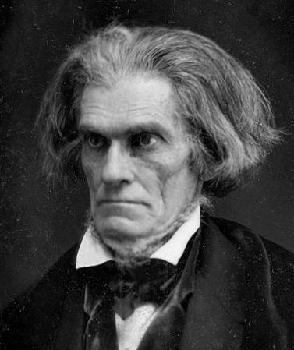

appeased by this compromise either. At the beginning of March, Calhoun,

too weak to deliver his speech himself to the Senate, had someone read

for him the biting accusations about the rising tyranny of the North,

and his call for an amendment to the Constitution that would give the

nation a dual presidency and the right of each state to veto any act of

Congress. Also, Southerners should be able to go anywhere in the Union

without the fear of having their property confiscated. Slavery must be

protected throughout the Union. Anything less than that would be

answered with the secession of the Southern states.

The speech shocked everyone, yet had the

effect of emphasizing even more the importance of compromise in order

to save the Union from dissolution.4

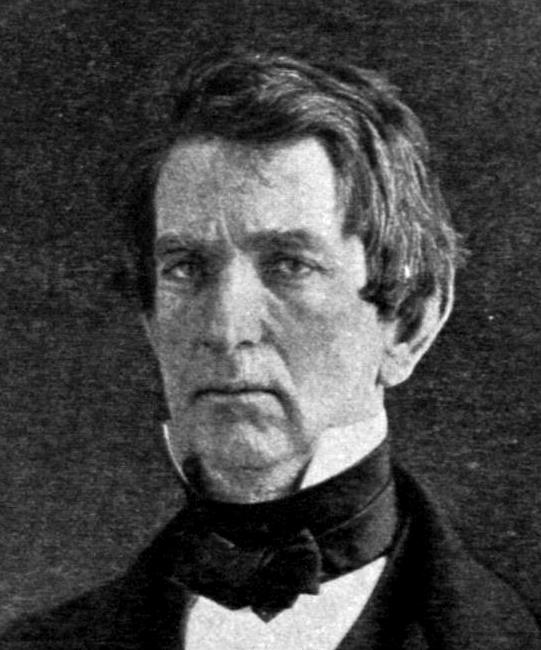

Several days later it was the turn of the

third elderly member of the Great Triumvirate, Daniel Webster, to

address the issue in the Senate. In his three-hour speech, he recalled

the history of the slavery issue as it had taken on ever greater

importance to the nation, the efforts to bring the issue to compromise,

and the overriding importance of maintaining the Union. He also

projected that any move to disunion would throw America into chaos, and

ultimately murderous conflict. With this he was stating what was

becoming increasingly obvious to all, that if America continued to

behave as it had been recently, there would be no escaping some

horribly violent outcome. The nation had to come together.

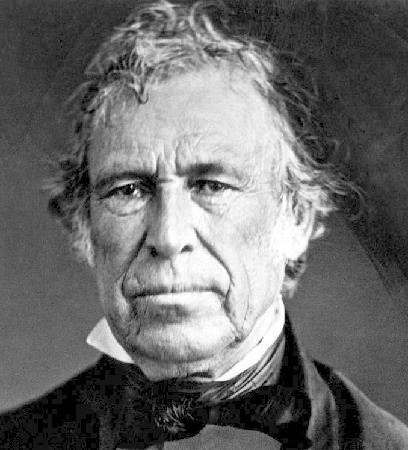

Then four days after Webster's speech, it

was the turn of a rising star within the Senate, William Seward of New

York, an Abolitionist Whig, to be heard. He put forward the claim that

there was a higher law than even the Constitution that he answered to,

the Law of God. That higher law would never permit him to return an

escaped slave back into the arms of immoral, illegal servitude.

Southerners were furious. Even Northerners were stunned. But Seward had

laid the seeds of an argument that would gather force among the

Northerners.

A Congressional committee was set up to

consider Clay's proposals and finally in May these proposals were

brought before Congress in the form of an omnibus5 bill: all measures to be voted up or down jointly in a single vote.

Meanwhile tensions were growing between

(slavery) Texas and (free) New Mexico, as Texas claimed that the

eastern half of what was being designated as New Mexico territory was

in fact an integral part of Texas. Texas was willing to enforce that

claim by military action if necessary.

But President Taylor weighed in against

Texas and demanded immediate accession of New Mexico as a new state,

and as an old soldier was willing also to enforce his viewpoint by

military action if necessary. Southerners then were quick to join Texas

in their outrage over this move by the president because the accession

of New Mexico would mean one more free state being added to the Union.

War clouds began to gather in the West.

Then in the midst of the furor, President

Taylor got sick attending a long, hot 4th of July ceremony in the

capital, worsened (by the help of doctors who bled him extensively and

pumped him with narcotics), and died five days later. The nation was

stunned.6

But this automatically elevated Vice

President Millard Fillmore to the presidency. And he was willing to

take a more centrist position, consulting both Clay and Webster, both

well known as willing to compromise on this matter.

But at this point it was time for yet

another key figure to take center-stage: Illinois Democrat Senator

Stephen A. Douglas. Though Douglas was a major slave owner (thanks to

his wife's inheritance of a 2500-acre plantation in Mississippi, which

he rarely visited but which was for him a constant source of revenue)

he was a Democratic Party moderate on the slavery issue. He proposed

that the various portions of the omnibus bill be broken out into their

different parts and be considered separately. This lowered the tension

about the all-or-nothing character of the legislation.

Also with the radical pro-slavery Calhoun

gone from the scene and with the death of the strongly Free-Soil Taylor

also no longer in the picture, tensions eased. Talk of war subsided.

Now a new mood opened the opportunity for compromise.

An exhausted Clay called on Stephen Douglas to run his measure through

the Senate again. This time the Compromise made its way successfully

through Congress in September in the form of a number of pieces of

legislation. Texas was willing to give up its claim on New Mexico (and

adjust its territorial boundaries elsewhere as well) with the

assumption of $10 million in Texas debt by the federal government. And

the part that the Abolitionists hated so fiercely, the promise of the

North to return all escaped slaves to the South (coupled with massive

fines slapped on anyone aiding and abetting any escape of a slave), was

finally passed as the Fugitive Slave Act.

Now the thought arose that the slavery

issue had been resolved once and for all. The Union was saved. But

Southerners remained skeptical. To them, whether the Union held or not

depended on how faithfully the North enforced the Fugitive Slave Act.

They were soon to find out.

3Of

course both houses of Congress were debating the same issue, but the

nation's eyes tended to be turned more to the Senate where debate was

viewed as having more of a strategic nature, especially when it

involved an address to the Senate of one or another of the Great

Triumvirate of Senators Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun.

4John

C. Calhoun died some four weeks later. With Calhoun dead, the Nashville

conference got put aside, and the secessionist mood in the South

subsided, for a while anyway.

5This

was a term that Taylor came up with, unhappy at how all these measures

had been thrown together, like being put in an omnibus, a large city

carriage that anyone could ride for a fee. The term stuck and is now

used regularly in Congressional legislation.

6Rumors

persist to this day that Taylor may have been poisoned. In 1991 tests

were made that said no, but even the tests have been contested.

| With the idea of

bringing California, New Mexico and Utah into the Union as "Free

States," things heated up, leading Henry Clay to offer a "compromise"

... admitting those states but enforcing the return of escaped slaves back

to their Southern masters.

|

A

very sickly Calhoun had a speech read in the Senate ... calling for a

change in the U.S. Constitution providing for a dual presidency... one

representing the North, one the South ... and the right of the states

to veto any act of Congress.

At this point, sectional tensions were heating up greatly.

|

| Then

Daniel Webster spoke up ... warning that sectional division would throw

the Union into deep chaos ... and ultimately bloody conflict. The

nation needed to come together.

|

Then

a young William Seward spoke up, stating that the Law of God would

never permit him to return anyone who had escaped slavery back into

such immoral servitude.

Meanwhile Texas (Slave) and

its neighbor New Mexico (Free) not only were engaged in a border

dispute ... but New Mexico's admission to the Union would strengthen

the Northern or Free position in the Senate.

|

| Then in the

midst of the furor, President Zachary Taylor got sick attending a long, hot 4th

of July ceremony in the capital, worsened, and died five days

later. The nation was stunned.

|

At this point the young Senator Stephen A. Douglas stepped forward to suggest a number of compromises.

Also,

with the death of both Calhoun (strongly pro-slavery) and Taylor

(strongly anti-slavery) tensions seem to subside. The hope was

that America could now get past the issue.

|

|

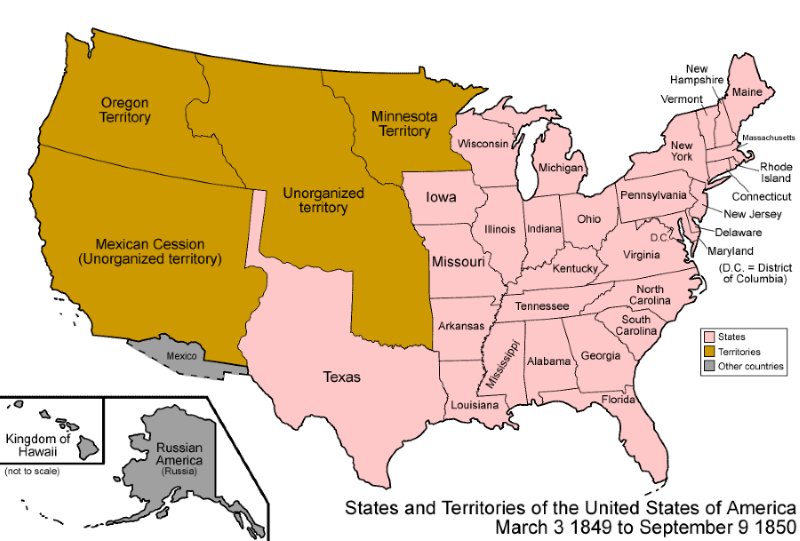

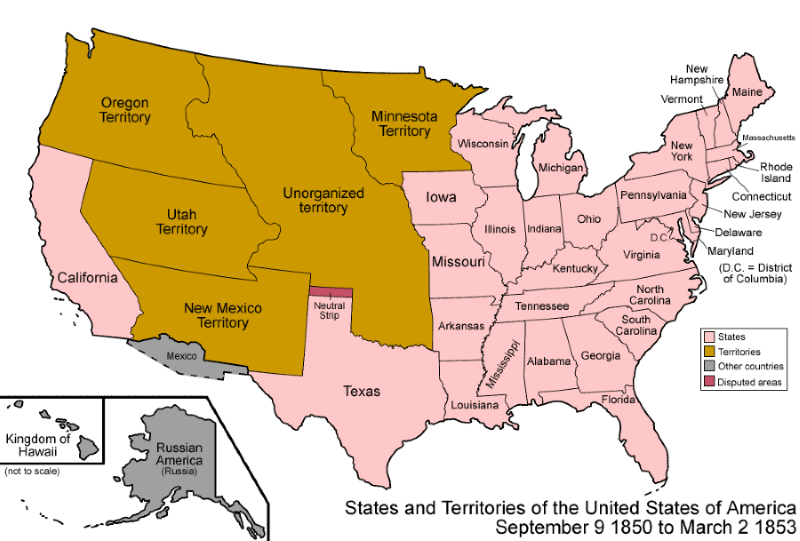

Territorial claims prior to the

Compromise of 1850

Wikipedia – "Compromise of

1850"

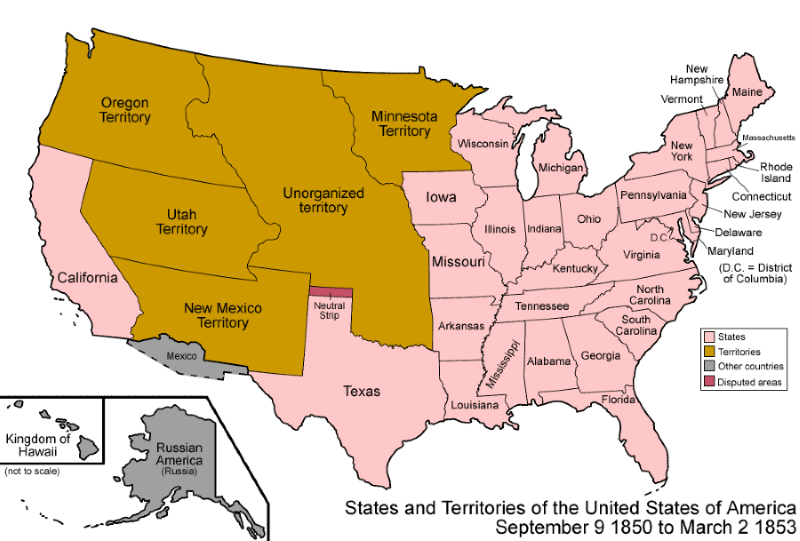

Territorial claims after the Compromise of 1850

Wikipedia – "Compromise of

1850"

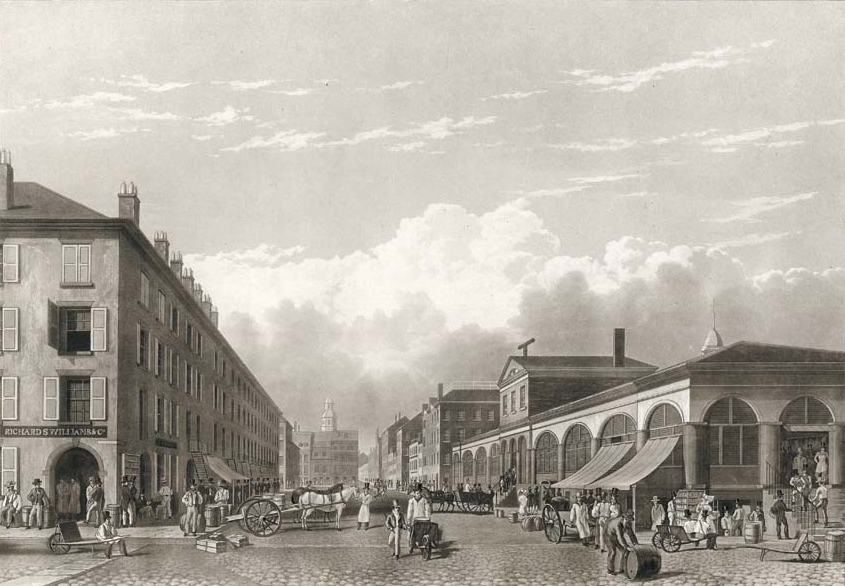

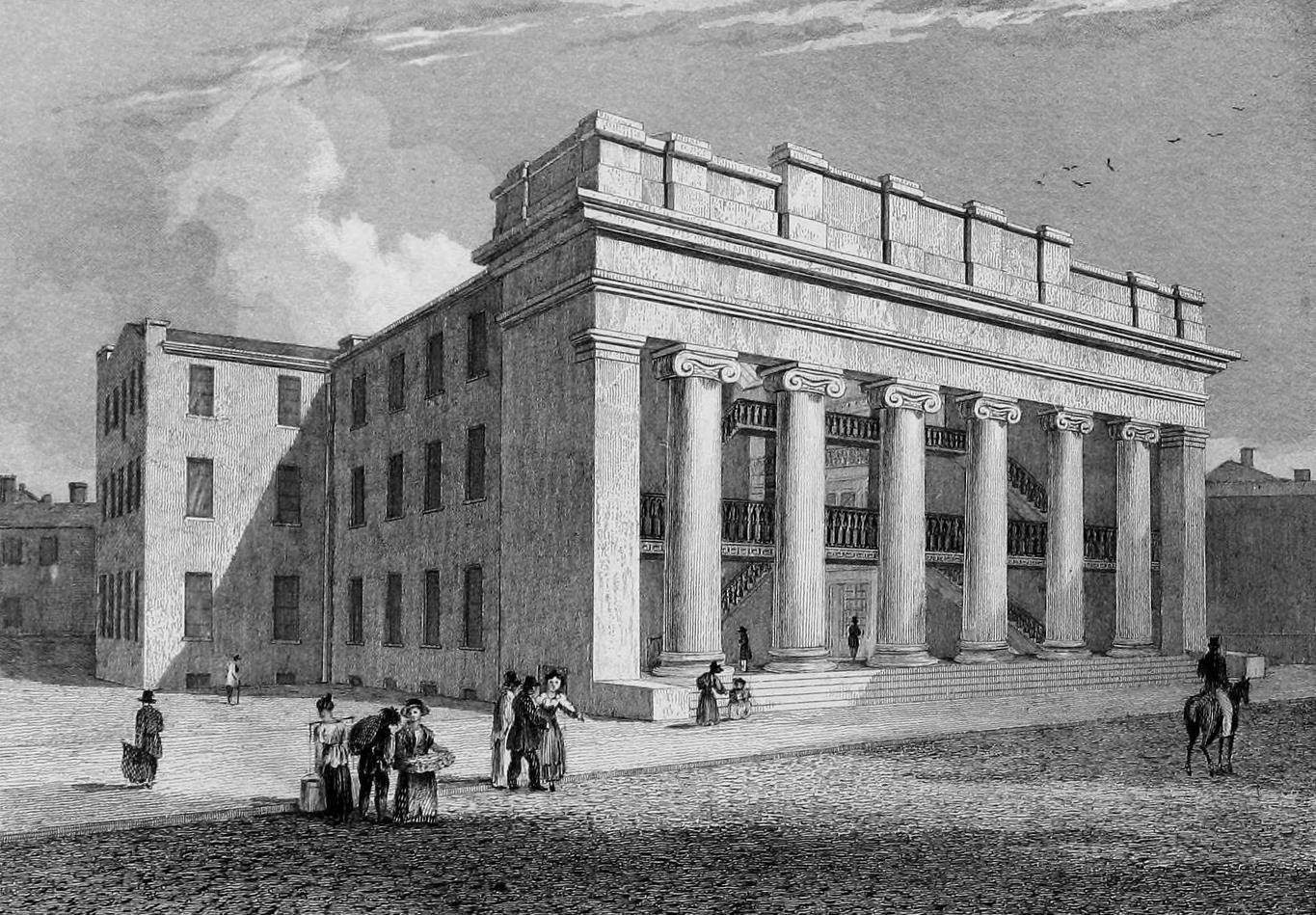

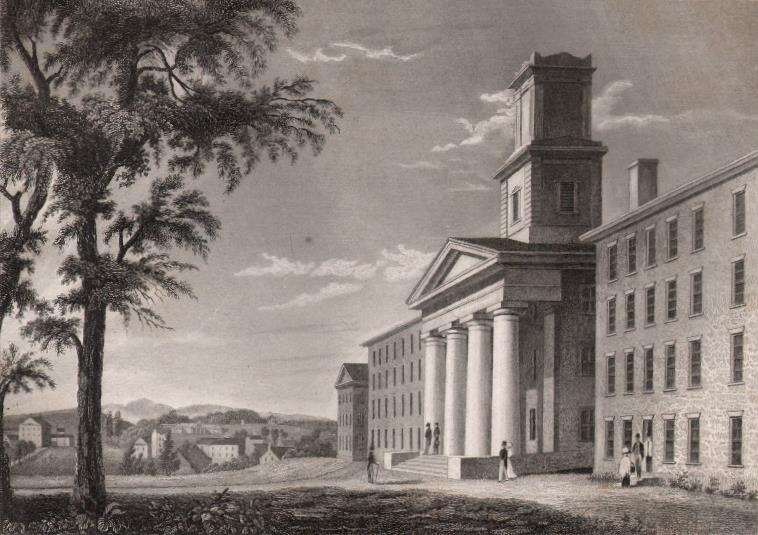

GLIMPSES OF MID-CENTURY LIFE IN AMERICA |

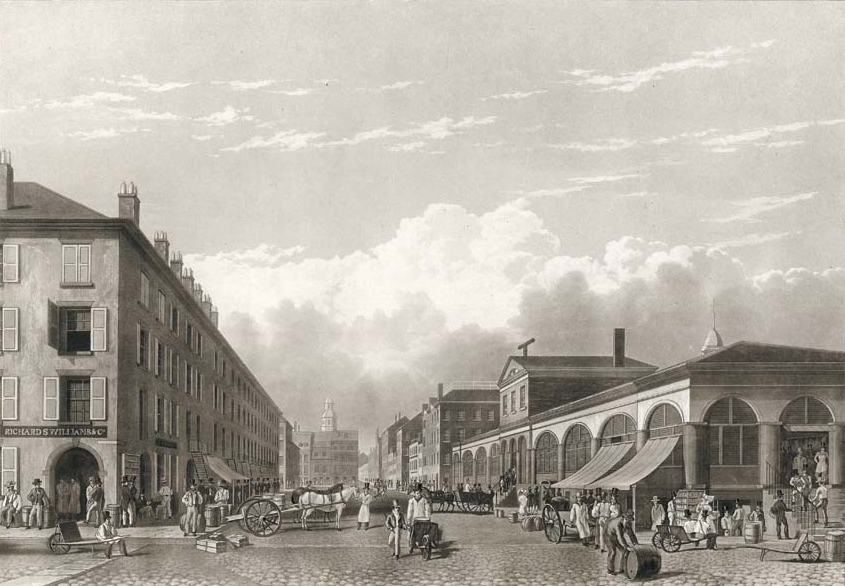

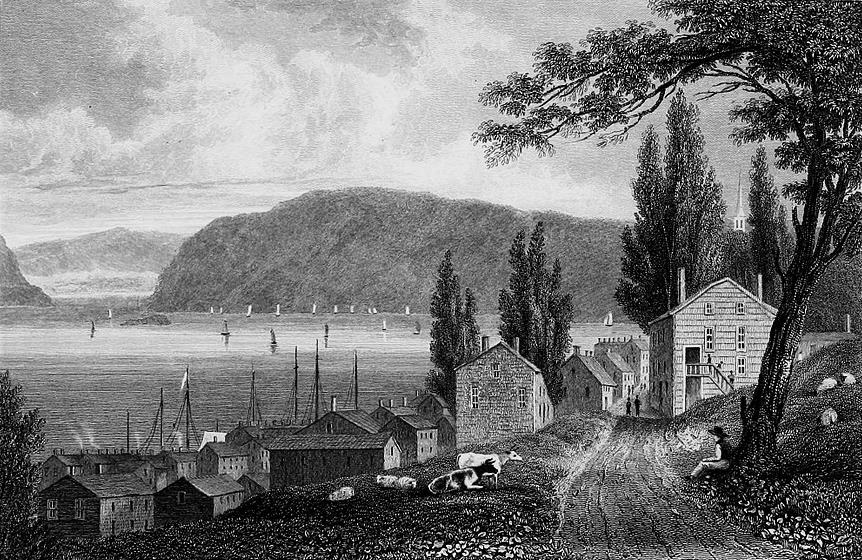

1833 – Boston Harbor – William Bennett

1833 – Boston Harbor – William Bennett

1834 – New York City – Fulton Street & Market – William Bennett

1837 – Detroit (viewed from neighboring Canada) – William Bennett

1841 – New Orleans – William Bennett

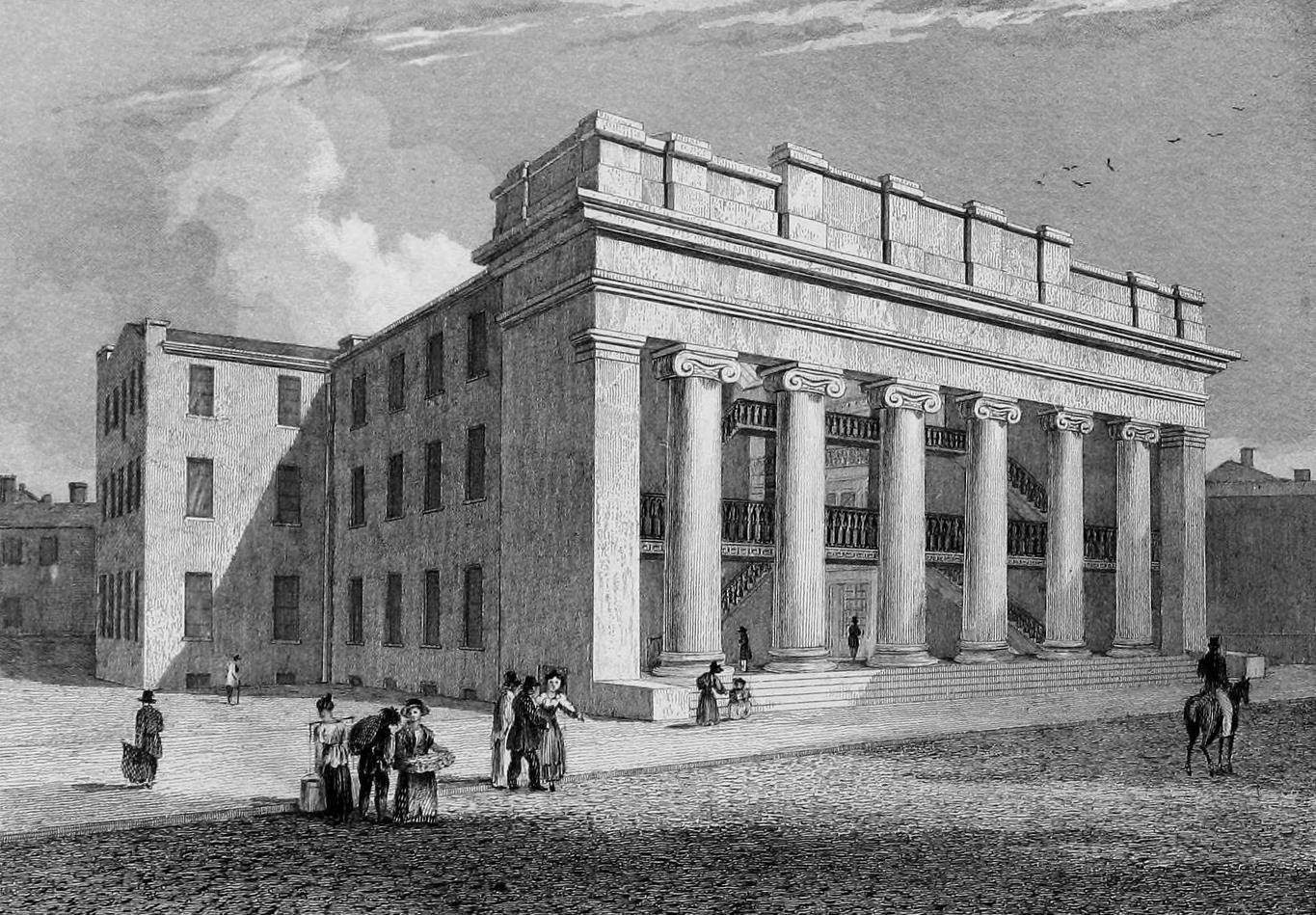

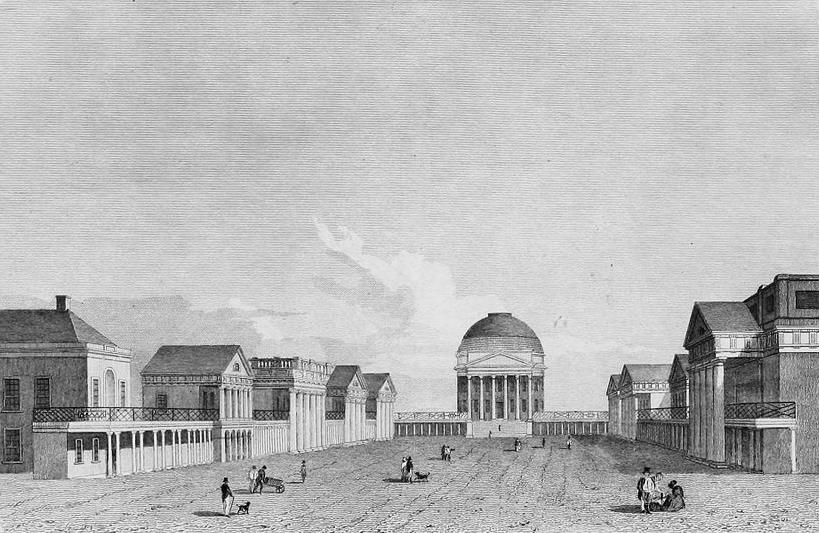

1850 – Providence, Rhode Island – The Arcade

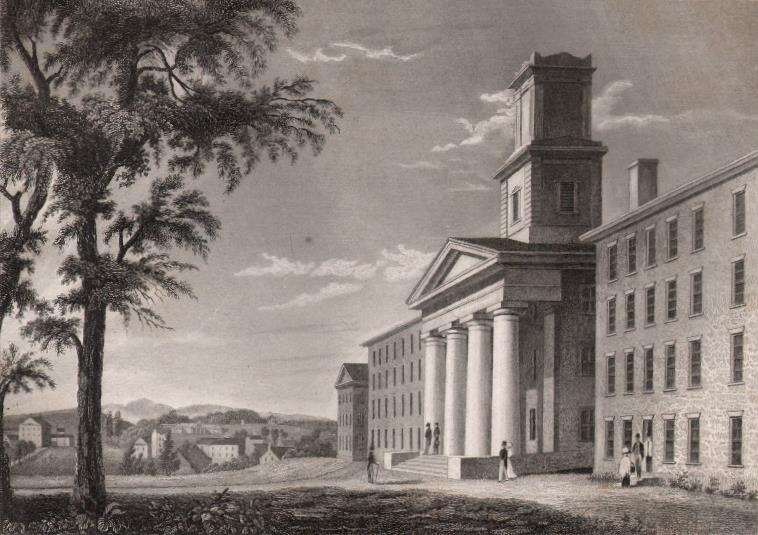

1850 – Amherst, Massachusetts – Amherst College

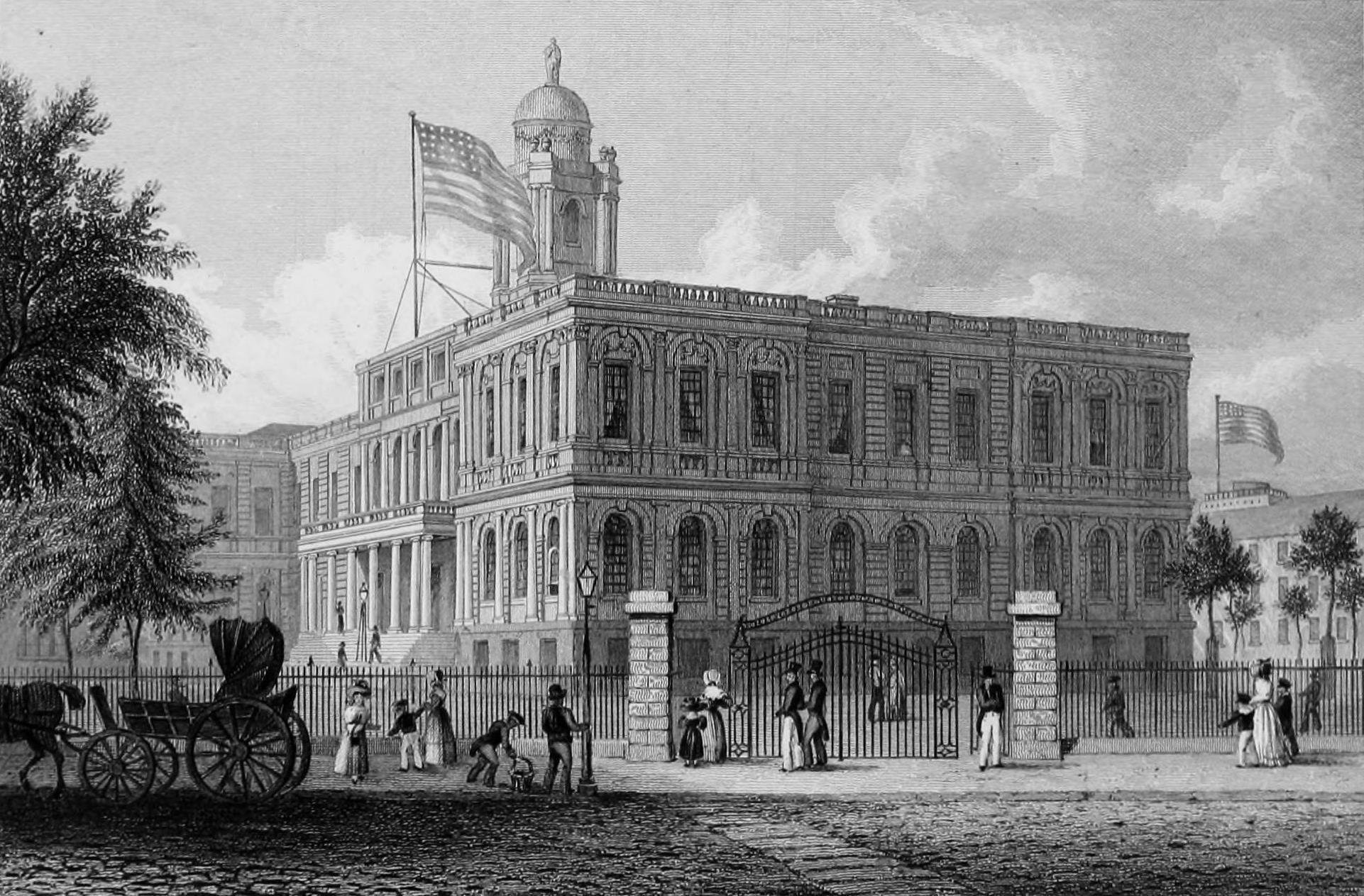

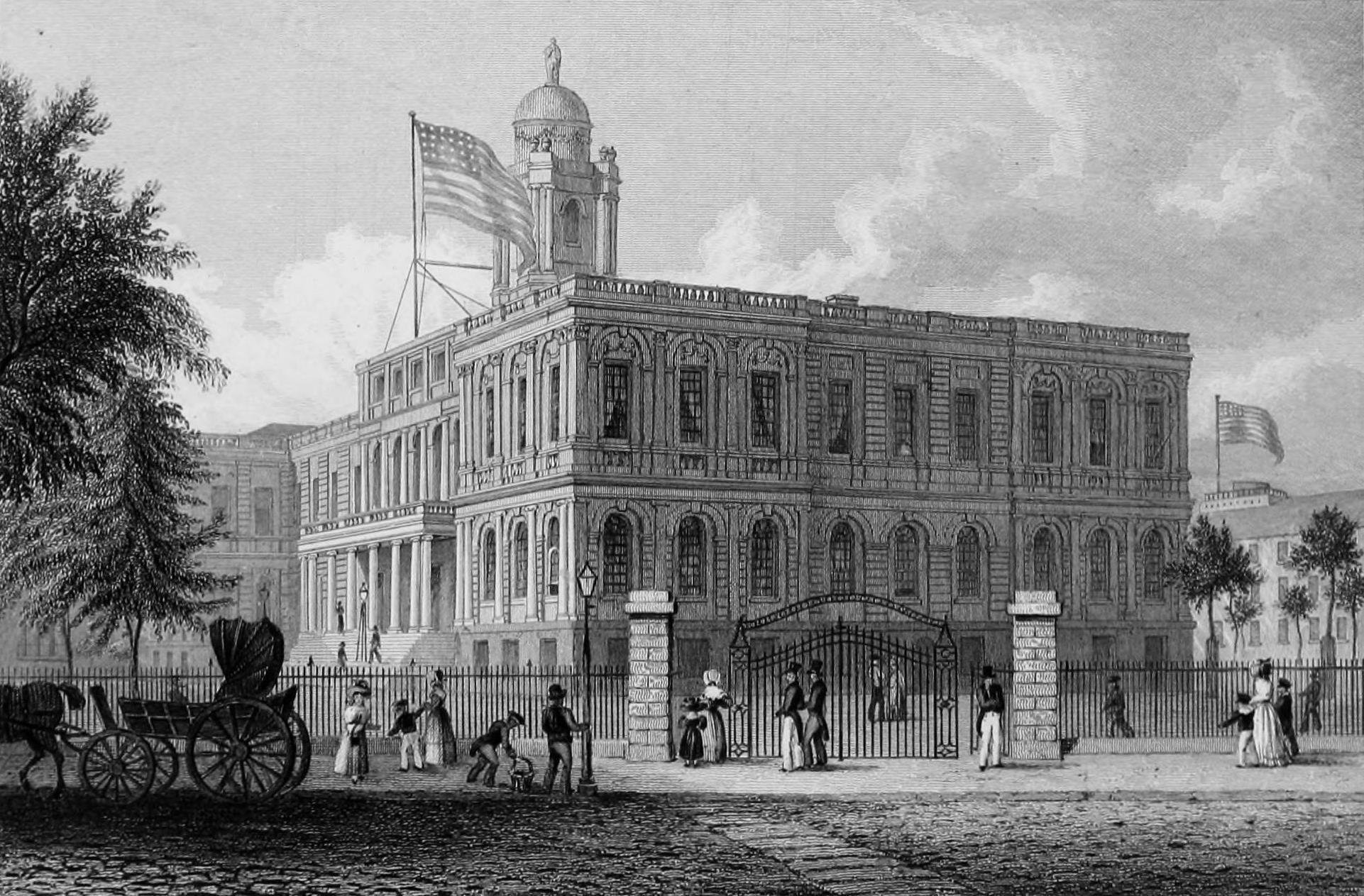

1850 – New York City Hall

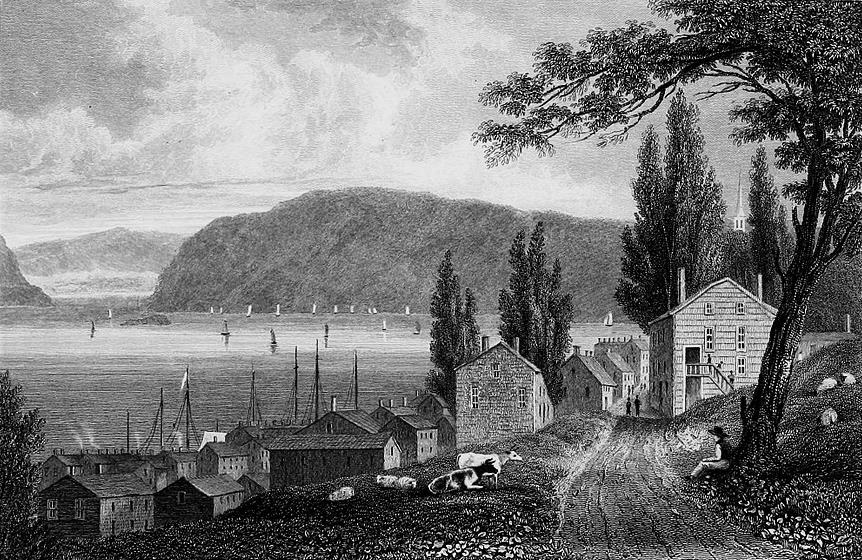

1850 – Newburgh, New York

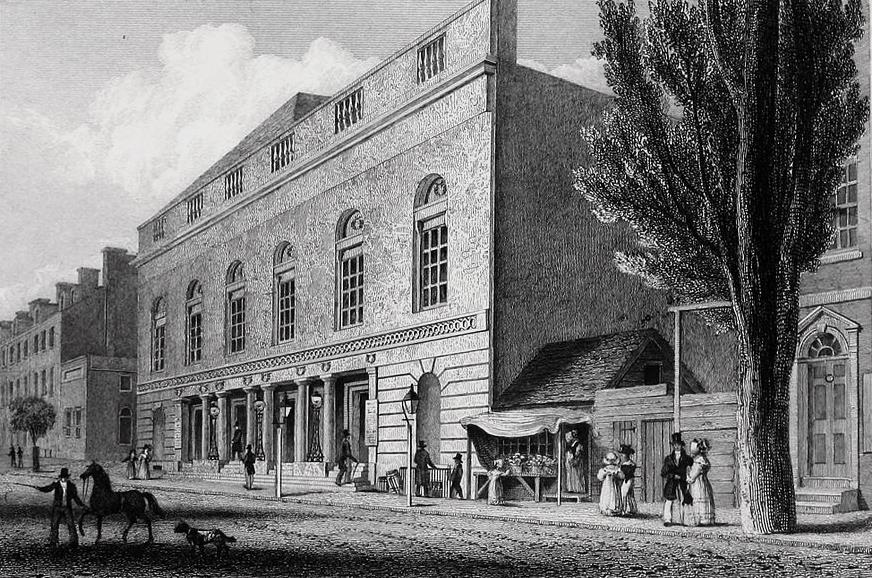

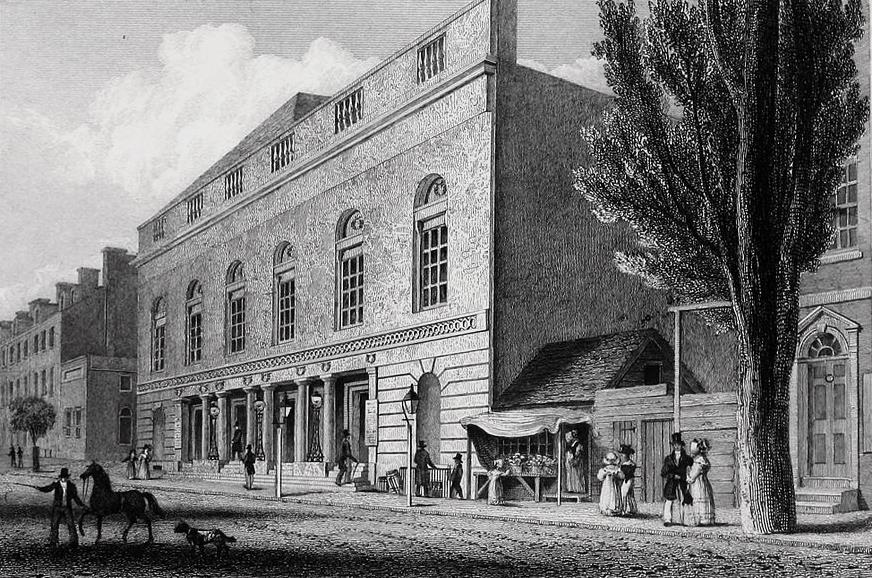

1850 – Philadelphia – The Walnut Street Theater

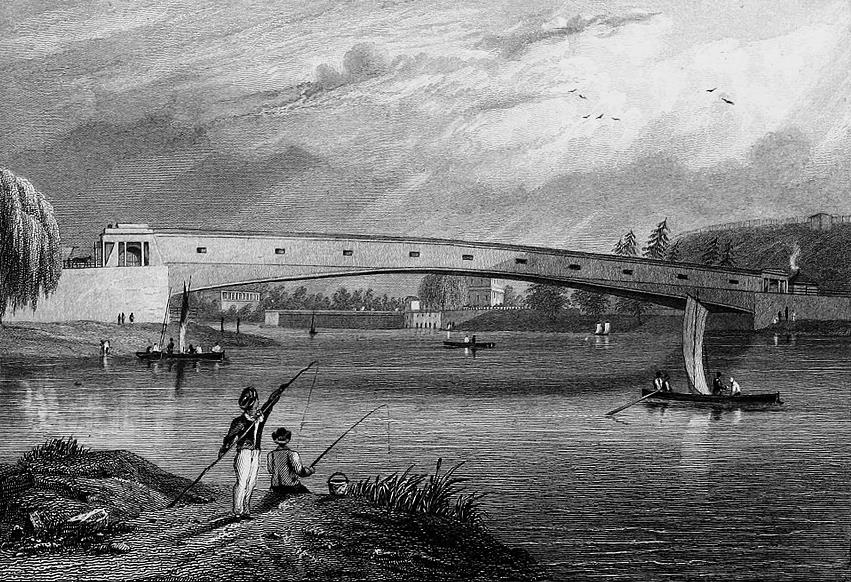

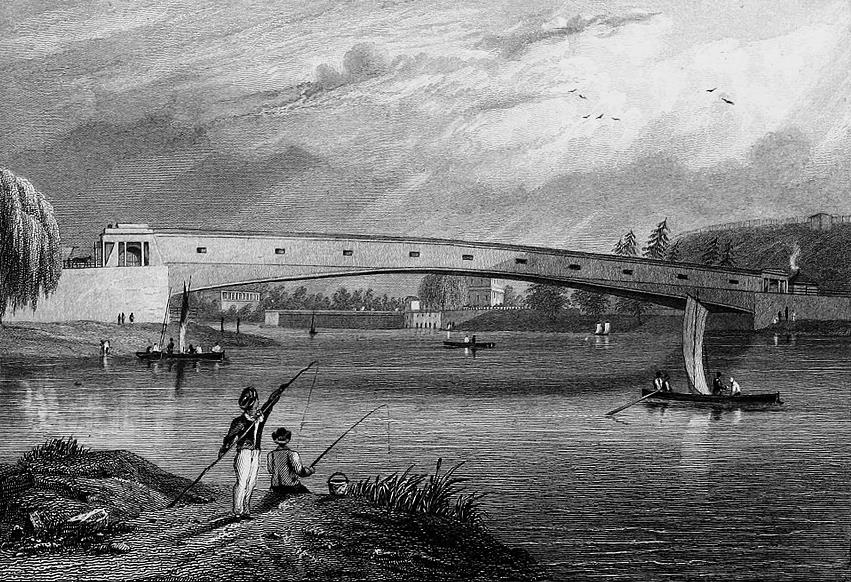

1850 – Philadelphia – Upper Ferry Bridge and Fair Mount Water Works

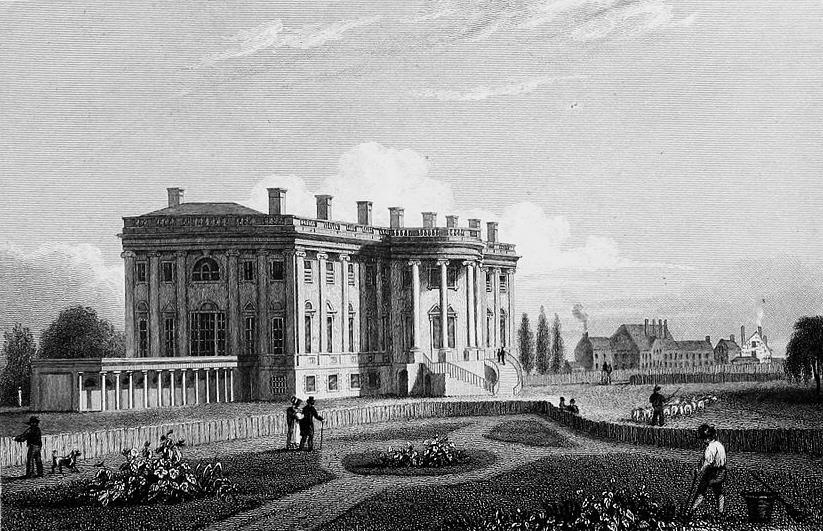

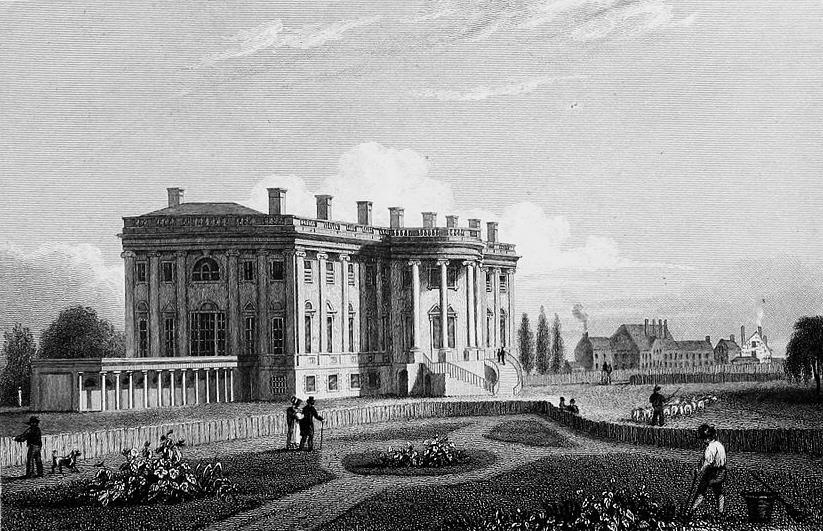

1850 – Washington, D.C. – The "President's House" (today's White House)

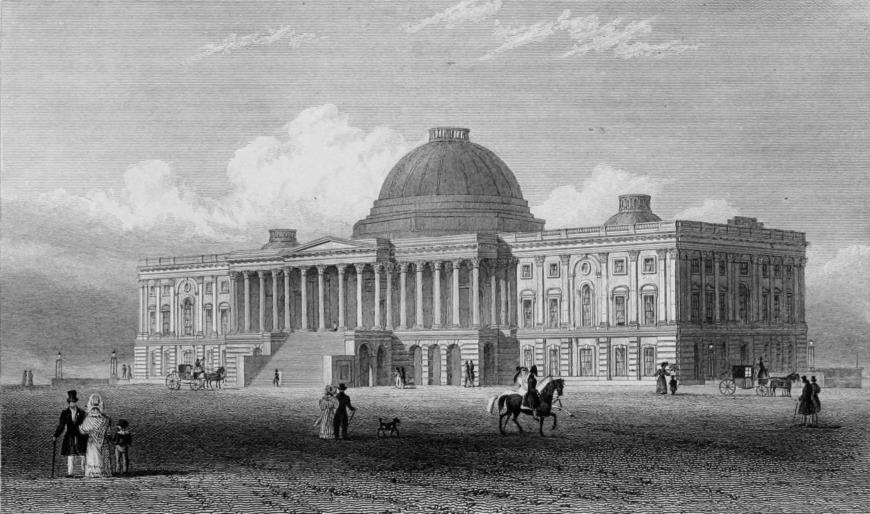

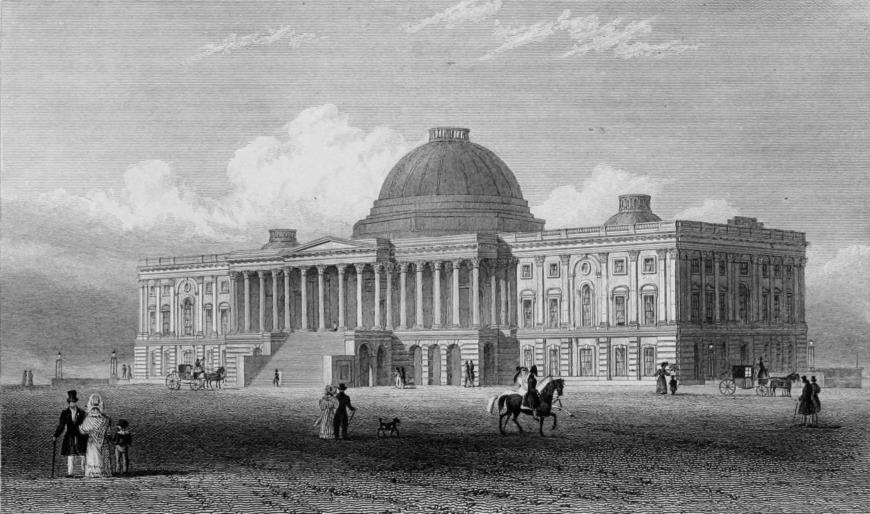

1850 – Washington, D.C. – The U.S. Capitol Building

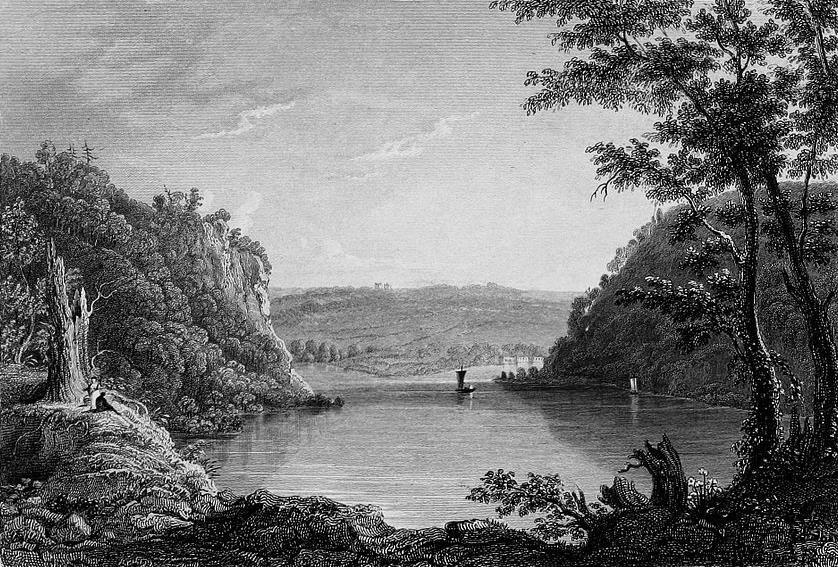

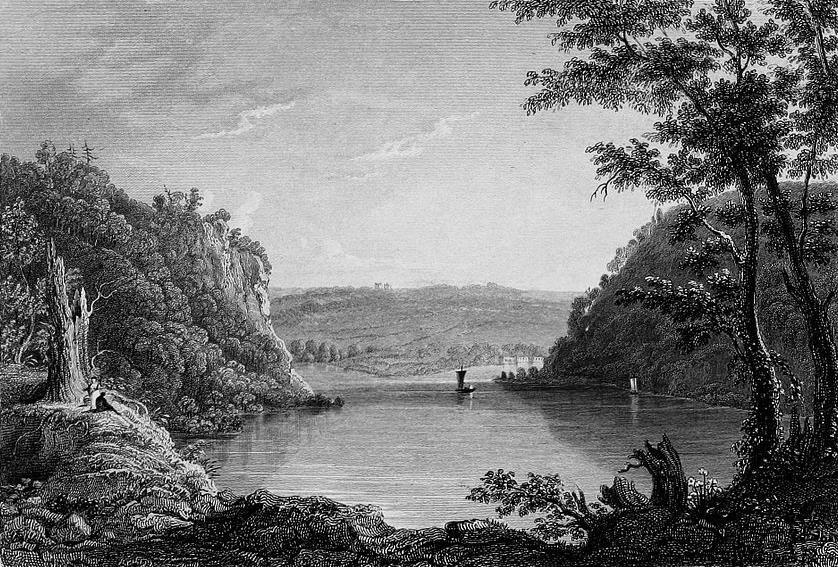

1850 – Harpers Ferry ... along the Potomac River

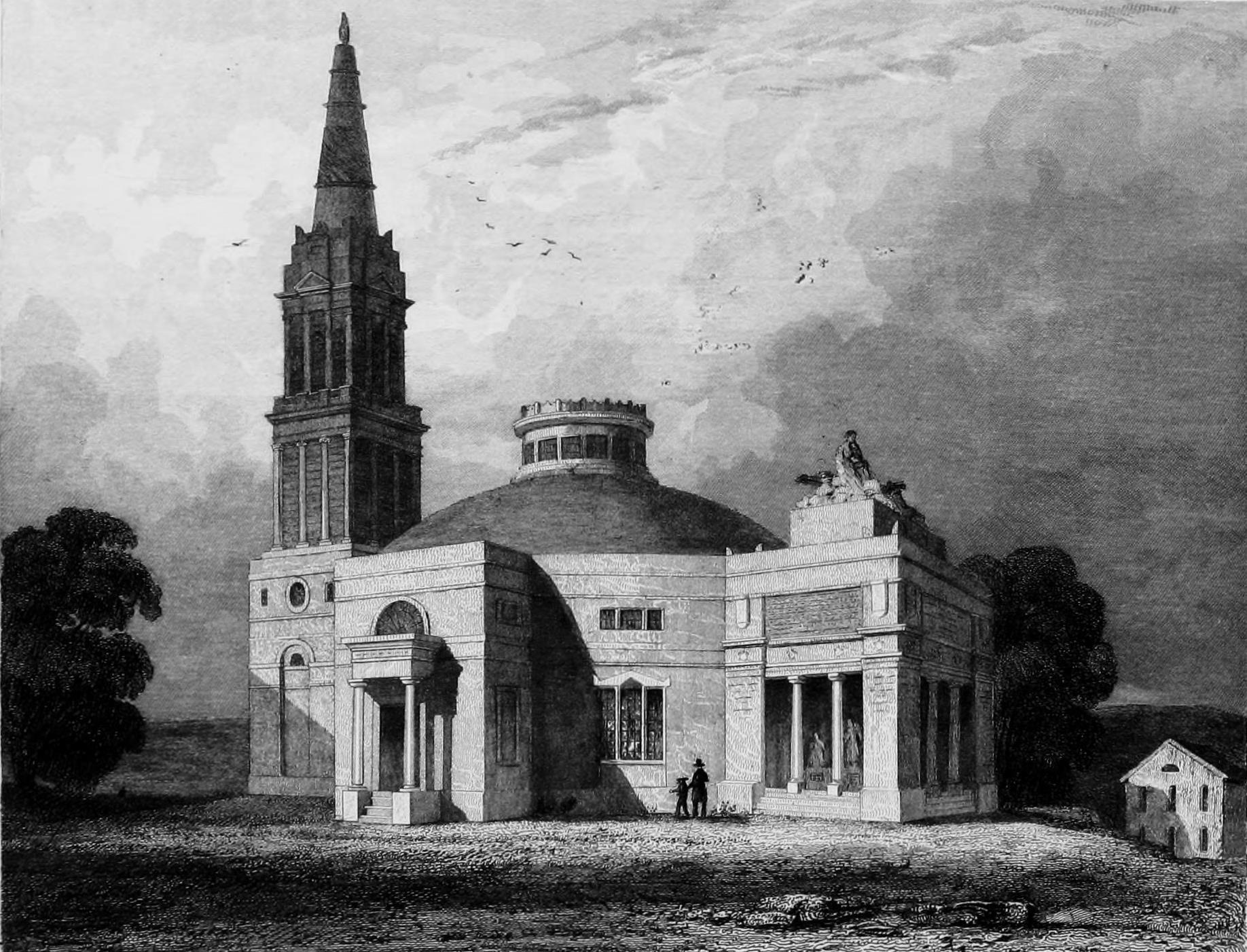

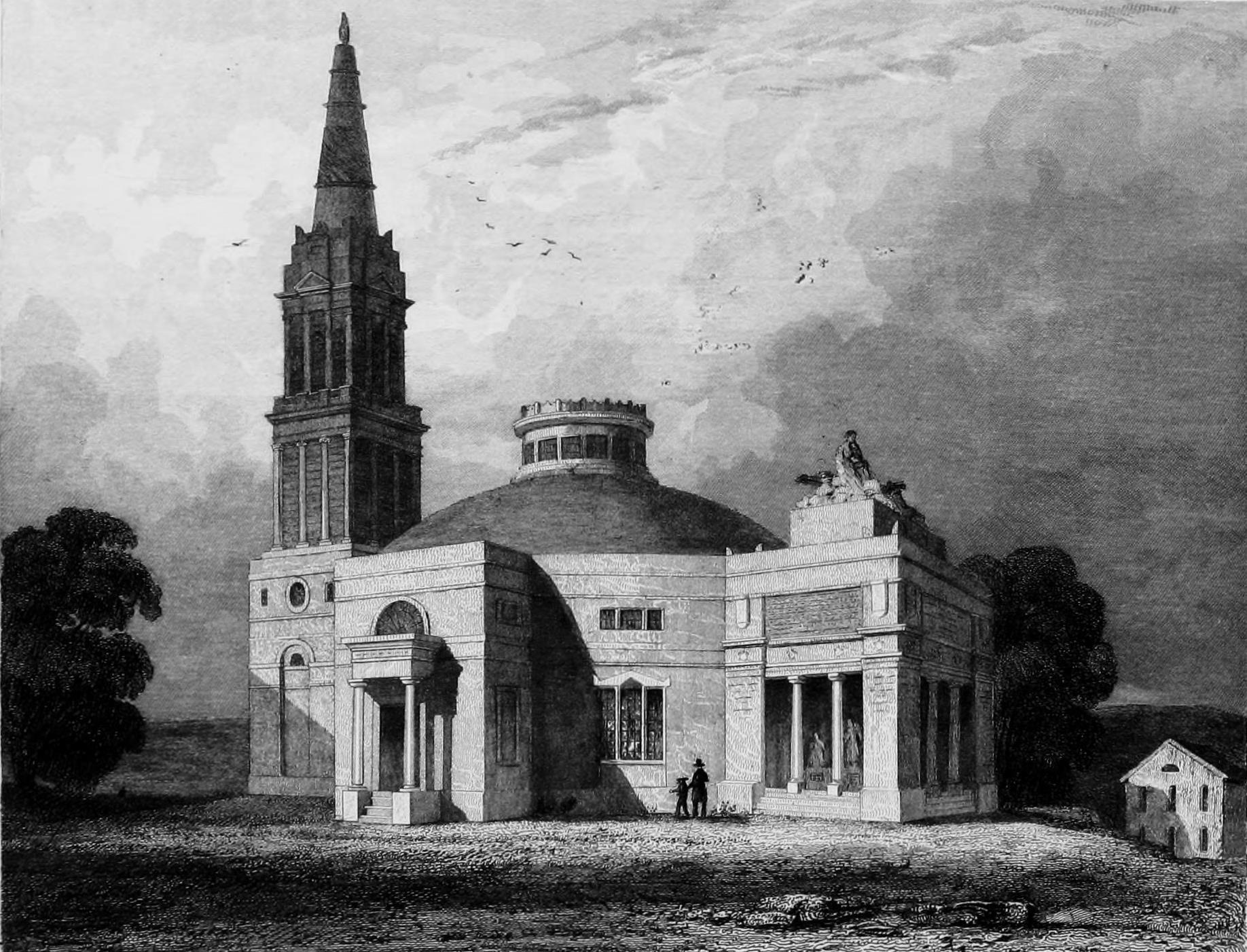

1850 – Richmond – The Episcopal Church

1850 – Charlottesville – The University of Virginia

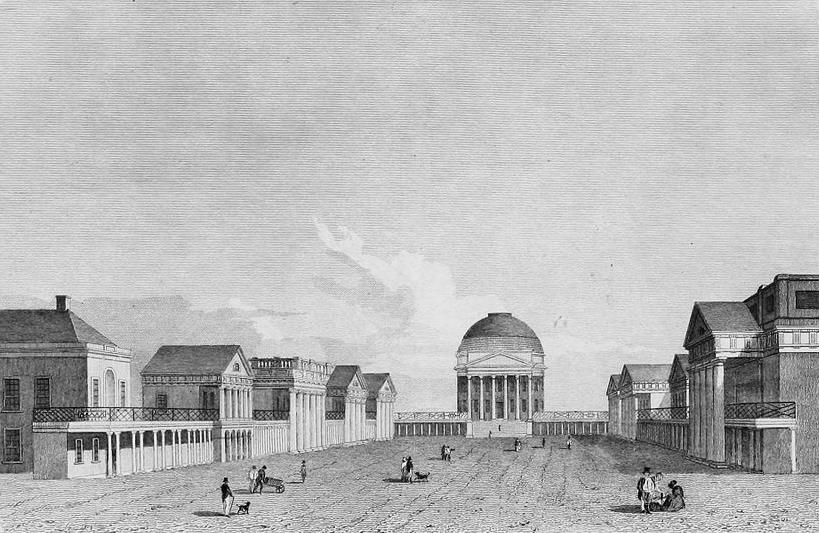

1850 – Raleigh, North Carolina – Capital building

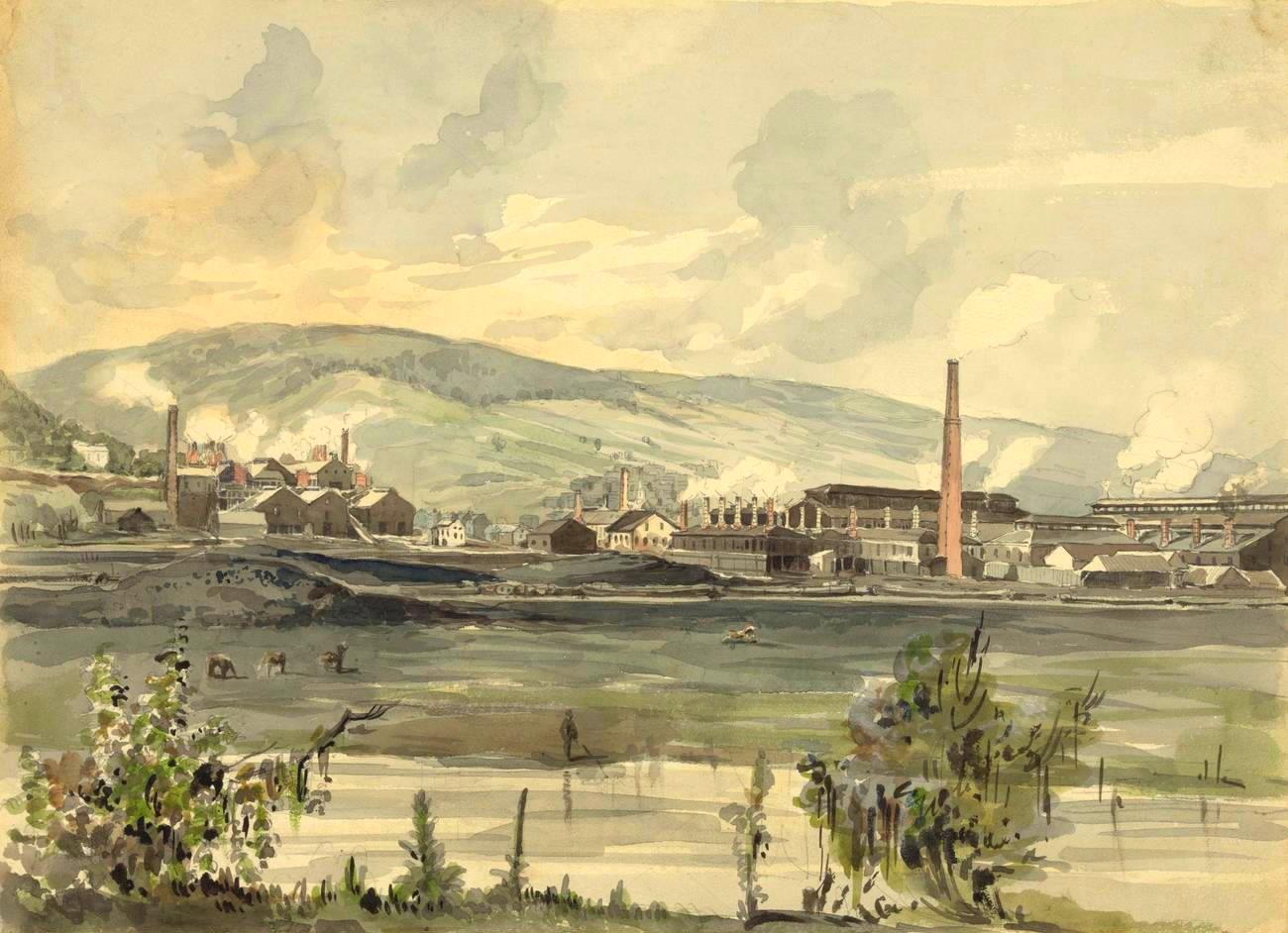

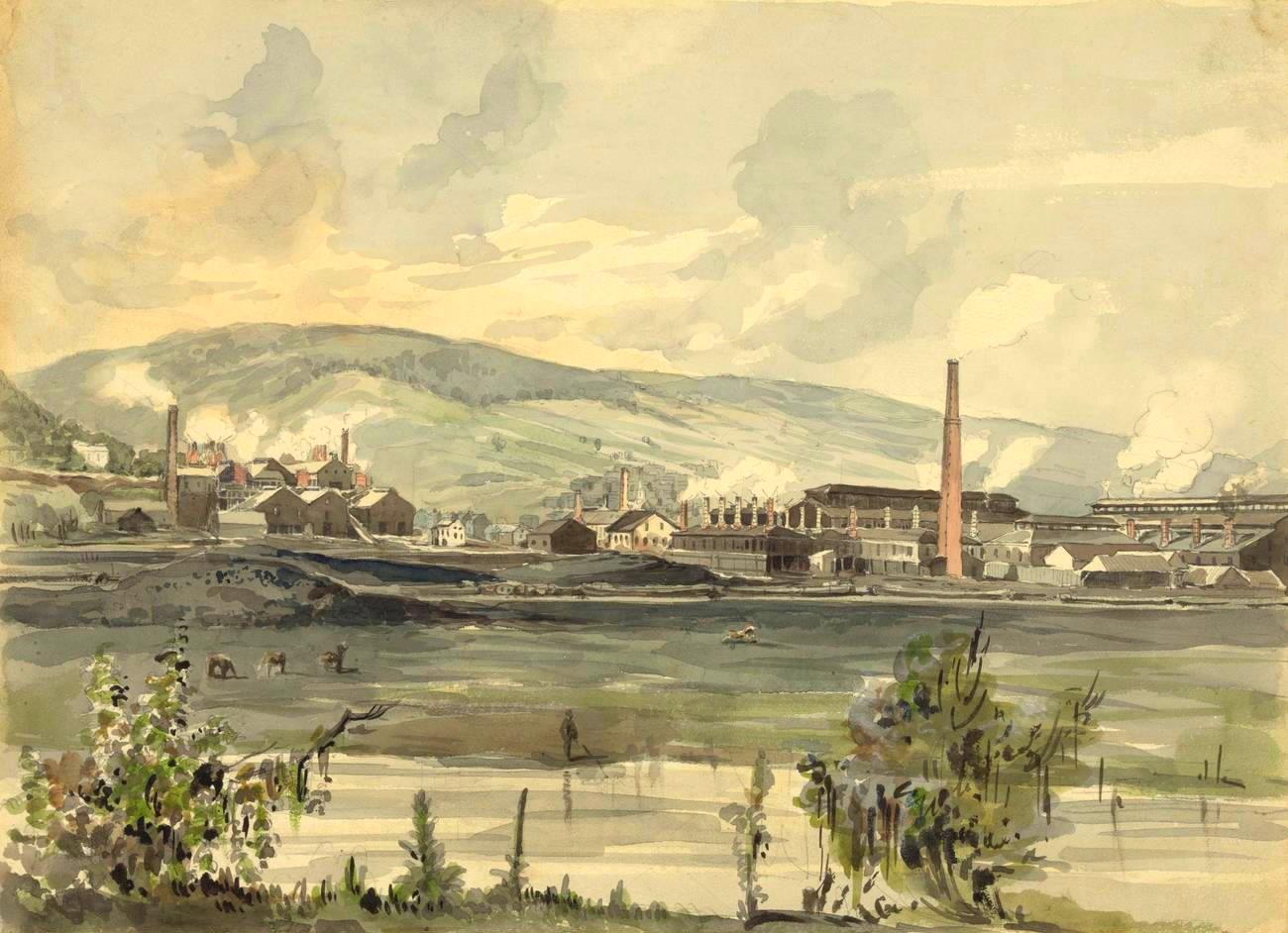

1857 – Factory on a river in Pennsylvania – James Fuller Queen

George Caleb Bingham

– Stump Speaking (1853)

oil on canvas

Saint Louis Art Museum

George Caleb Bingham – The County Election (1852)

oil on canvas

Saint Louis Art Museum

George Caleb Bingham

– The Boatmen

Saint Louis Art Museum

1850 – Irish Immigrants

Go on to the next section: The Steps towards War

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

The widening social-cultural gap

The widening social-cultural gap Glimpses of mid-century life in America

Glimpses of mid-century life in America