7. EXPANSION ... AND DIVISION

THE GROWING CONFLICT OVER SLAVERY

CONTENTS

The Abolitionist Movement The Abolitionist Movement

The election of 1848 The election of 1848

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 261-266.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1830s |

Violence now accompanies the slavery debate

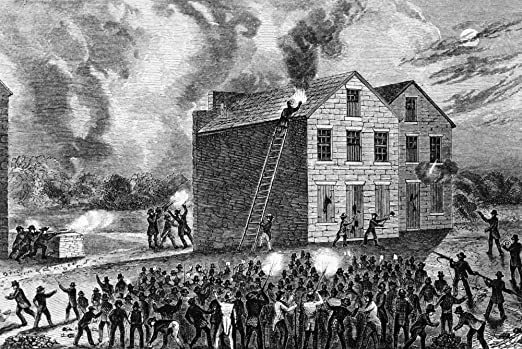

1837 Alton newspaper publisher and preacher Elija Lovejoy (Alton, Illinois) is murdered on the fourth assault on his

newspaper by a proslavery mob furious over his Abolitionism

|

| 1840s |

The Abolitionist Movement gathers strength; but the issue is still too much for most Americans

1830s-1840s The examples of Britain ending slavery in its country (1807) and then in its overseas Empire (1833) and the French doing the same in France itself (1794) and then in its overseas colonies (1848) only pushes the Abolitionists to press harder for the American abolition of slavery

For many

Americans, the ongoing Christian "Second Great Awakening" also inspires

them to take a strong anti-slavery position

1845 Frederick Douglass's autobiographies (1845 and 1855) of his life as a

slave sell big in the north

1848 However ... the tameness of the 1848 presidential elections and the victory of the Mexican warhero Taylor – whose views on the slavery issue are largely unknown – indicates a general desire of most Americans to move past the burning issue of slavery

|

THE

ABOLITIONIST MOVEMENT |

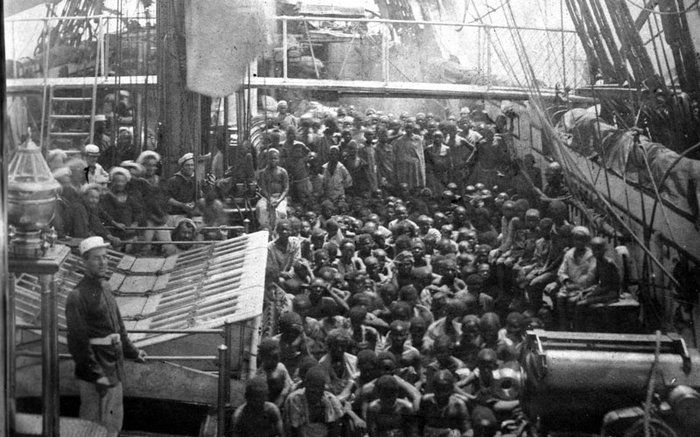

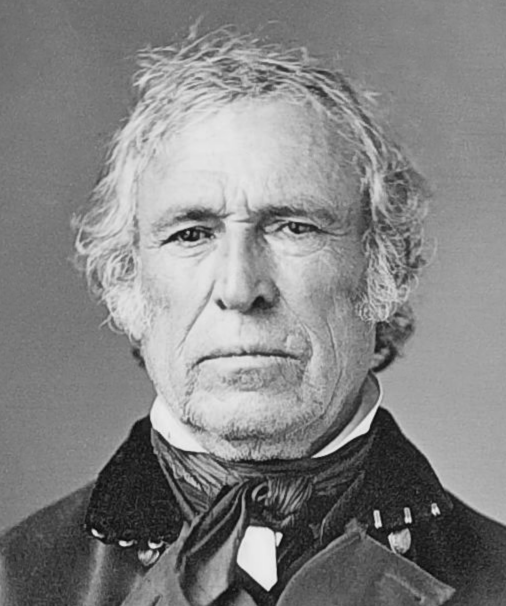

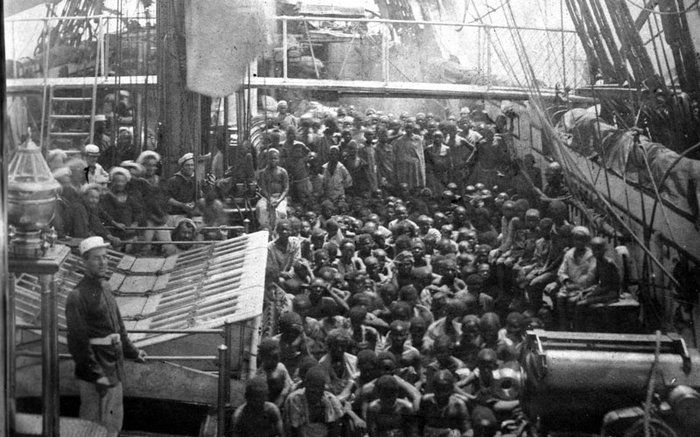

Slave ship loaded with African slaves

![]()

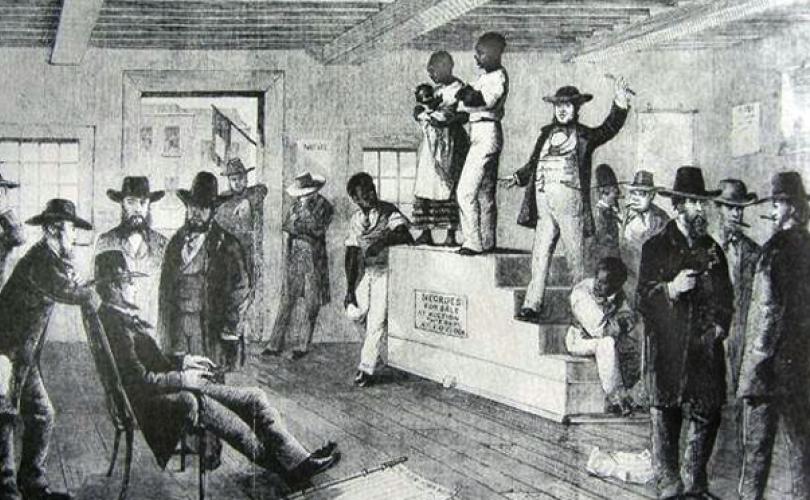

A slave auction

|

In the meantime, American culture was splitting

ever more deeply over this persistent question about Americans holding

slaves. There was no way that the problem was going to simply go away

on its own or just be avoided, as many Americans had earlier held the

hope that this might be possible. But high-sounding principle was

easier to achieve than actual plans of action.1

Unfortunately, such a large part of American culture (especially in the

South and parts of the West) was built on ideals requiring the labor

services, voluntary or involuntary, of other people. To undo such a

social system was to destroy the cultural ideals of economic and social

success themselves.

But there also was no way that the spirit

of Puritan Protestantism widespread in the North could ever come to

tolerate intellectually and emotionally this behavior in the land of

freedom. Slavery violated every Christian sensibility of the

Northerners, to a point that some in the North grew increasingly

impatient at the willingness of even their own Northern

politicians to tolerate or ignore this stain, this sin corrupting the

soul of the great American nation. Americans were understood to be a

Covenant people called to display to the world the glories of living as

Christ's people, to be a light spreading hope into the darkness of the

surrounding world. Surely slavery made a mockery of this Covenant. Some

felt very strongly that God would curse the nation for breaking this

Covenant that their forefathers had agreed to two centuries earlier.

And the Republic that had been put into place only a few generations

back, a Republic dedicated to the high calling of being a light to the

nations, would fail ... fail miserably. Thus the institution of slavery

had to be abolished immediately. And so it was that those who advocated

such action came to be called Abolitionists.

Abolitionism and the Second Great Awakening

In fact, many Abolitionists saw in

slavery the seeds of certain destruction of the American people and

society, by the hand of God no less. Indeed, the religious fervor of

the Second Great Awakening, which continued to burn forward through the

1830s, 1840s and 1850s, had made slavery its main hot-button issue.

Preachers, newspapermen, self-appointed social reformers and even a

small handful of congressmen saw this issue intimately tied up with how

God was looking in judgment at his Covenant people. America could not

afford to lose its soul over this issue.

In general however, aggressive

Abolitionists were not widely popular, not even in the North at first.

They were viewed as being dangerously disruptive of the good order of

the Republic. Those who viewed themselves as being of a wiser nature

tended to presume that the good moral sense of Americans would

eventually work this problem out. Thus it was in 1836 that Congress had

placed its gag rule on any further discussion of the slavery issue.

Nonetheless, the issue was a big part of what would go on to divide the

New School and Old School Presbyterians in the late 1830s, the division

tending to follow North-South lines. Likewise, in 1845, the Baptists

also split quite permanently along North-South lines over the matter.

Then also there was the fact that the

English had already set the noble example in 1807 by abolishing slavery

within England and then in 1833 by extending abolition to the entire

British Empire. France had outlawed slavery as far back as 1794 during

the French Republican Revolution (though Napoleon had reintroduced the

practice somewhat after 1804) and in 1848 France made the move to

abolish slavery throughout all of its colonies. Thus also to the

American Humanists, America's failure to follow the moral example of

England and France brought unbearable shame to America as the supposed

model of Enlightened Republicanism.

Most American supporters of freedom for

the slaves advocated a gradual process of emancipation. They considered

this to be the more responsible solution to the problem. Others

supported the idea of sending Blacks, both free or slave, back to

Africa where it was supposed there would be a more natural fit for

them. Thus Liberia had been established in 1820 by President Monroe

(and thus Liberia's capital Monrovia) as a resettlement colony on the

West coast of Africa.

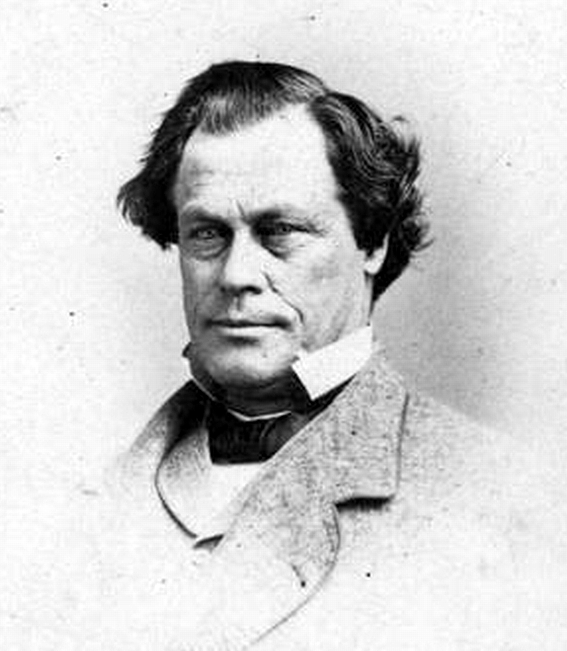

Abolitionist voices. However, the Abolitionist

William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society

and publisher of the newspaper, The Liberator,

wanted abolition to occur immediately and fully. He even went so far as

to accuse the U.S. Constitution of being a pact with slavery. This

ranked him among the most radical of the Abolitionists.

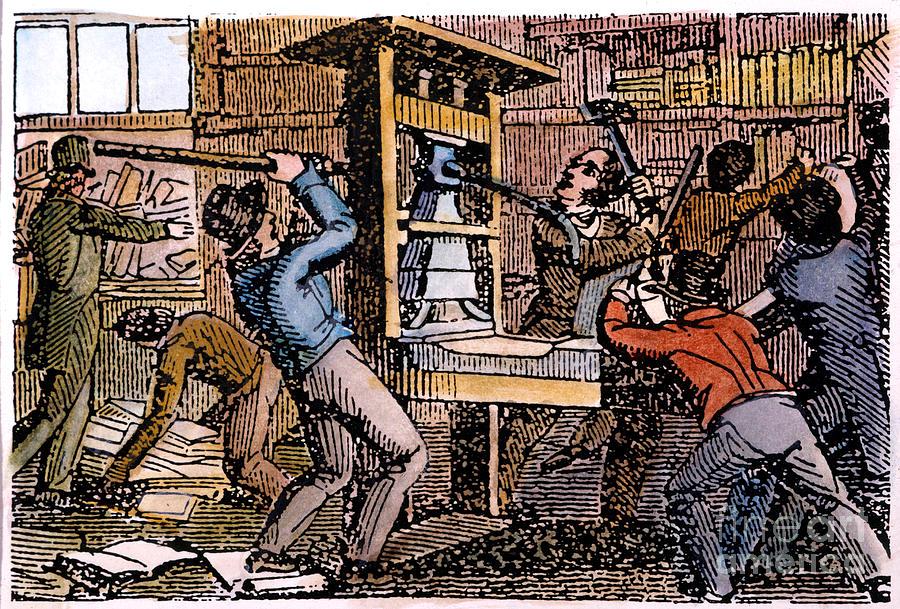

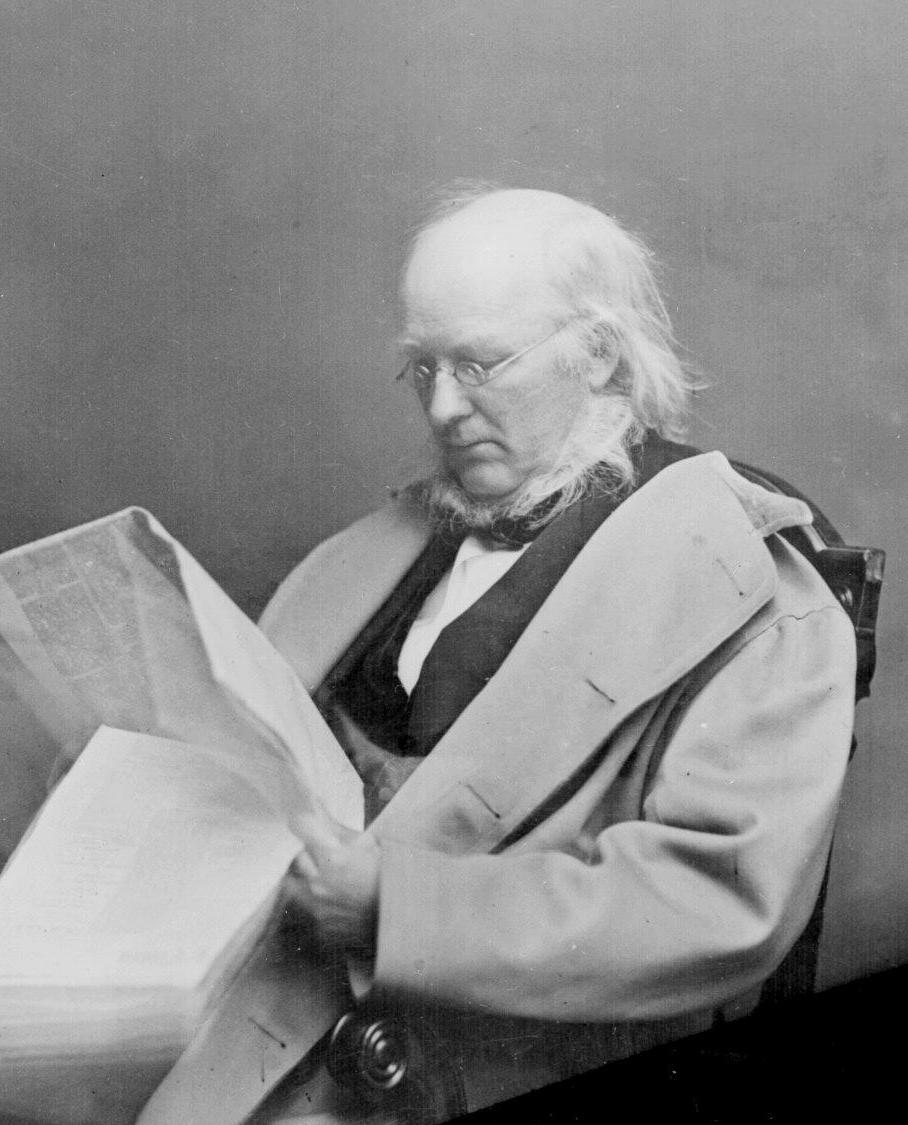

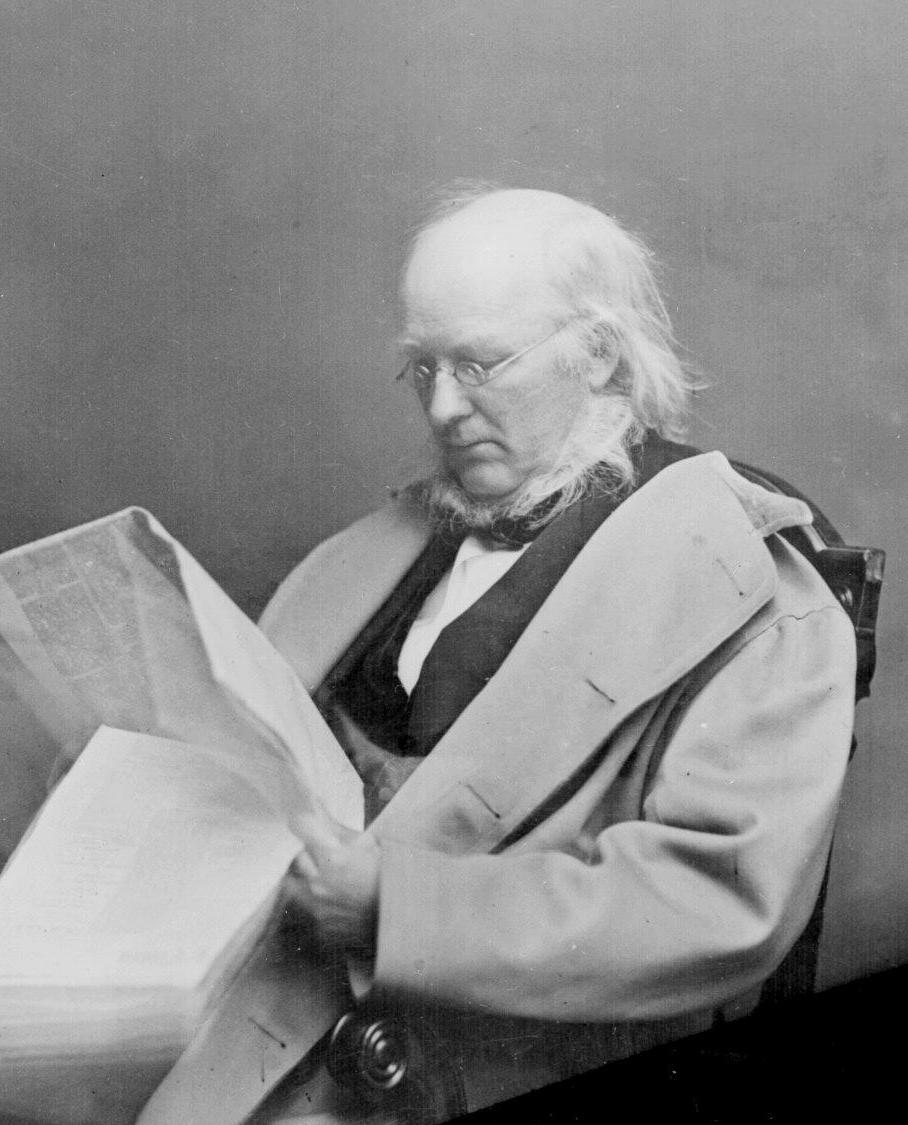

A number of other newspapermen, such as Horace Greeley, editor of The New York Tribune,

were also constant in their verbal assault on the vile practice of

slavery. But this could be a very dangerous issue for newspapermen to

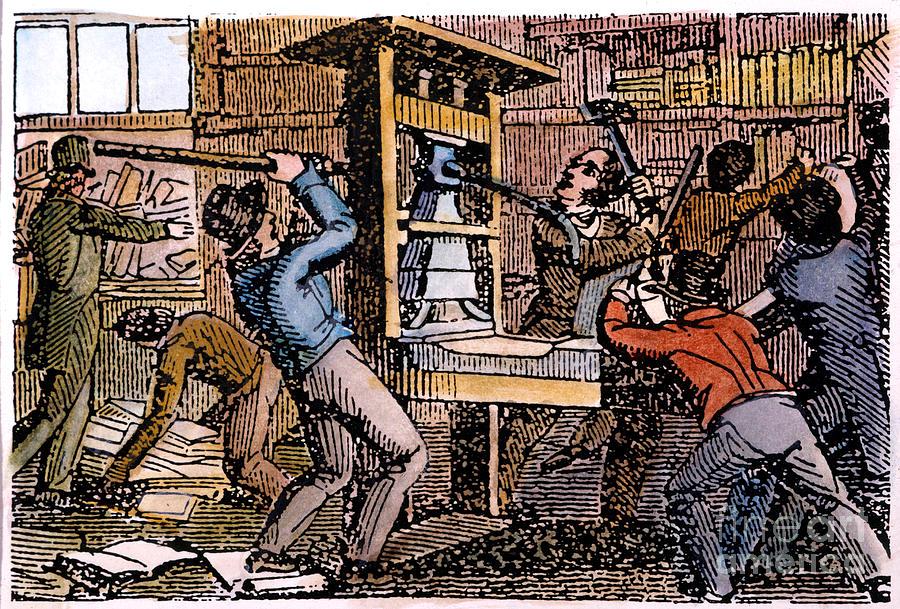

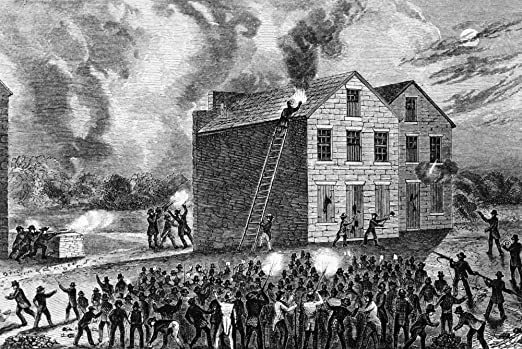

pursue. In 1837 an angry pro-slavery mob attacked the newspaper office

of the Alton (Illinois) Observer run by the Abolitionist and

Presbyterian preacher Elijah Parish Lovejoy, the fourth such attack on

him and his press. But this time they murdered him, making him a martyr

to the Abolitionist cause and pushing his brother Owen into the

leadership of the Illinois Abolitionists.

1Jefferson,

for instance, though admitting the wrong of slavery, could not bring

himself to free his slaves. Instead, in his will, he required the sale of

his slaves to other slaveholders to pay for the debts he had run up by

constantly redesigning his Monticello home in his effort to perfect it

as a miniature utopia.

|

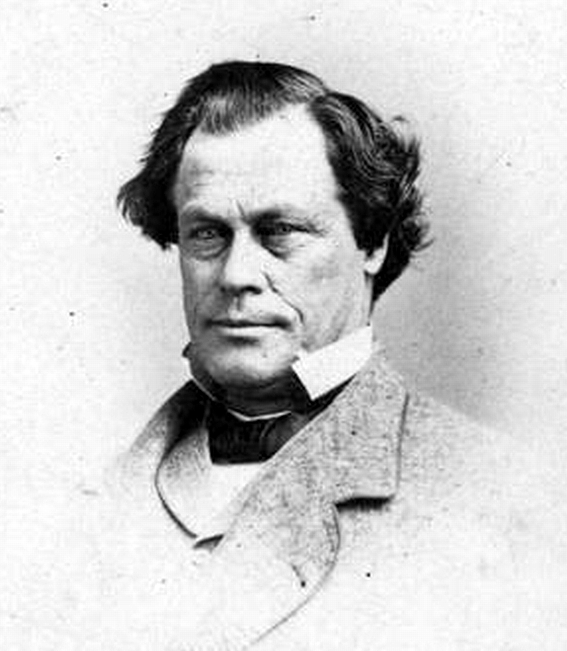

Presbyterian preacher and publisher of the Alton (Illinois) Observer had his press attacked four times because of his Abolitionist stance. Finally in 1837 a mob burned his offices, killing Lovejoy in the process. His brother Owen then took over the lead of the Illinois Abolitionists

Elijah Parish Lovejoy

his brother Owen

William Lloyd Garrison

Horace Greeley

Garrison published the newspaper The Liberator and founded the American Abolitionist Society; Greeley was editor of The New York Tribune ... and early Abolitionist

|

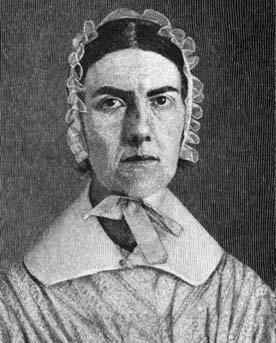

The Abolitionist cause was also moving

front and center in the midst of a growing feminist movement in

America. Alongside the temperance movement to slow down or prohibit

entirely the consumption of alcohol (Amelia Bloomer and Harriet Beecher

Stowe), the public-school movement to extend public schooling into the

poorer neighborhoods of America's fast-growing cities, and the movement

to reform prisons and insane asylums (Dorthea Dix), the call for the

abolition of slavery stirred women to tremendous public action (making

even some male social reformers nervous!). The Grimke sisters, Angelina

and Sarah, were Southerners who moved to the North to get away from the

horror of slavery. And from their new home in the North they dedicated

themselves to opposing the practice by any means possible, particularly

through the distribution of pamphlets and lecturing around the country.

As a Quaker, Lucretia Mott put her views to work in lectures enjoining

women to see it their duty to push for the immediate end to slavery.

Also joining the Abolitionist movement would be future suffragists

(demanding the right of all women to vote) Susan B. Anthony and Lucy

Stone.

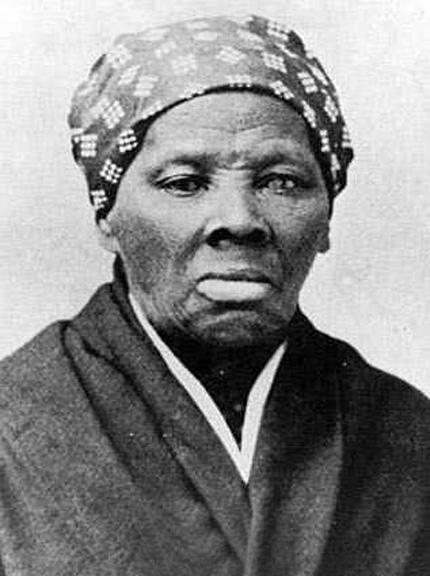

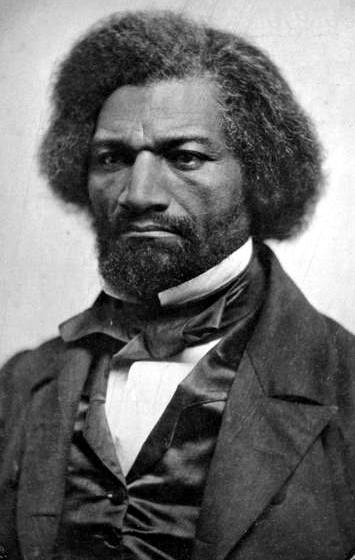

Free Blacks also joined the Abolitionist

chorus, speaking from the horror of personal experience. Thus Sojourner

Truth and Harriet Tubman worked actively in support of immediate

freedom for the slaves, Tubman becoming active in aiding escaped slaves

to head North through the Underground Railroad and Sojourner Truth

joining the speaking circuit to publicize the need for immediate action

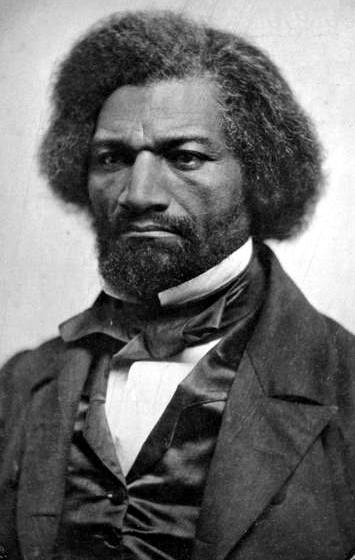

on the issue. But undoubtedly the most important voice coming from the

Black community itself was that of Frederick Douglass, whose obvious

intelligence put to lie the idea of inherent Black inferiority on which

the South built its moral case. Douglass was one of the greatest

orators and writers on the subject, his books Narrative of The Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845) and My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) both becoming best-selling works.

And working from within the political

system was once the ever-vigilant John Quincy Adams. He had taken the

bold course of presenting himself for election to the House of

Representatives in 1830, after having lost to Andrew Jackson his bid

for reelection as president in 1828. Then as a Massachusetts

representative in the House, he proved to be far more politically

effective than he had been as president. And on the basis of his strong

opposition to slavery he built an ever-growing reputation, both in

focused support and in focused opposition. He had simply ignored the

1836 gag rule and pushed the issue ever before Congress, frequently by

stirring his pro-slavery opponents to wrath and thus actionable

rebuttal. He had made dedicated enemies, of course. But he also had

begun to have his impact in Congress, as he rose higher as a clear

moral voice that constantly forced Congress to face the issue of this

vile institution. He even became close friends with his former

arch-rival within his Whig Party, Henry Clay.

|

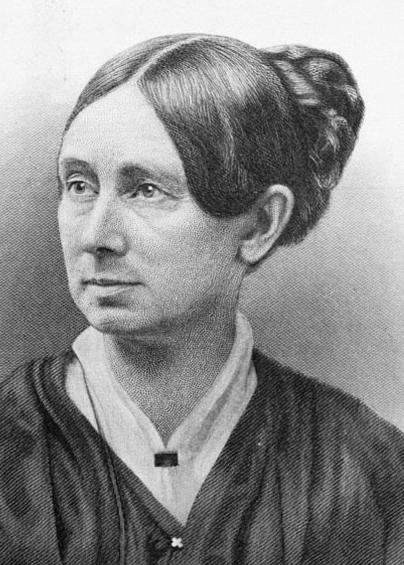

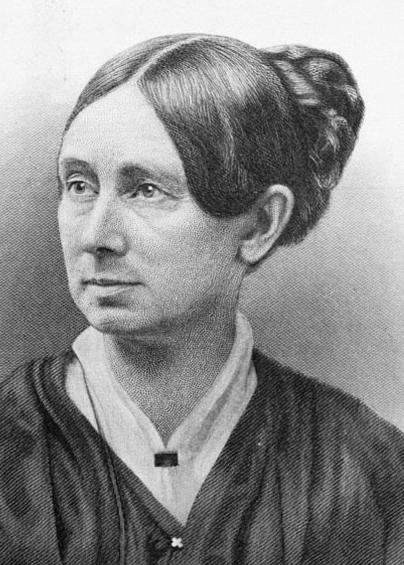

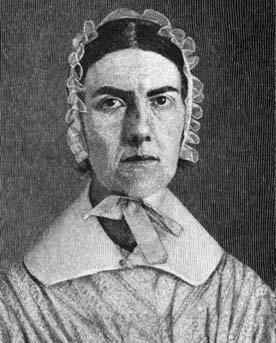

Female

voices against slavery

Amelia Bloomer

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Both were also strong anti-alcohol voices

Dorthea Dix

Dix was also a school prison reformer

Lucretia Mott

Mott was a strong Quaker Abolitionist

The Grimke sisters, Angelina

and her sister Sarah

They moved to the North to get away from the evil of slavery

Susan B. Anthony

Lucy Stone

Also strong supporters of women's voting rights (Suffragists)

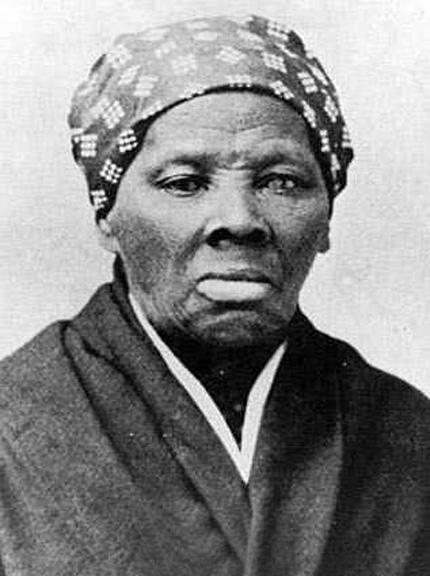

Black voices

Harriet Tubman

Tubman was very active in the "Underground Railroad" – helping slaves escape to the

North

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was very active on the speaker circuit as an Abolitionist

Frederick Douglass

Douglass was both circuit speaker and publisher of best-selling autobiographies

|

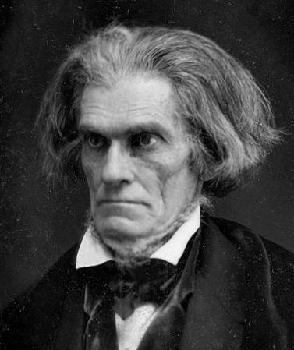

The slave-holders' moral response

Southerners, such as the fiery-tongued Calhoun of

South Carolina, were quick to react to the moral condescension coming

from the Abolitionists and soon formulated a moral reply of their own.

As the slave-holders themselves now in essence put things: slavery

existed as a divine ordinance of God himself because Blacks were unable

to function outside the system of mastery by the Whites. Thus slavery

was more than merely a legal matter. It was a racial and even religious

matter as well. Whites and Blacks were two different breeds of people,

obviously (to any reasonable observer) unequal in their nature or

character. Blacks were clearly destined by God himself to serve (as the

sons of Ham) the superior White race.2

Messing with God's ordinance, as certainly the Abolitionists were

doing, was itself going to bring on America the wrath of God.

So there it was. Two opposing viewpoints, both

enshrined with a keen sense of divine legitimacy, both employing

precise human logic to develop and deepen their two contradicting moral

positions. There was no way that the issue therefore was going to

simply go away on its own. The challenge of answering the moral

question of slavery had spun America into two moral camps with only a

small and rapidly declining moral realm still uniting them.

Once again, Human Reason was not going to

provide America with any clarity or Truth that could bring it out of

this growing hostility. Human Reason merely fortified the two bitterly

opposing social viewpoints, even at this point religious worldviews.

Conflict – vicious conflict – was increasingly the only way this

critical issue was going to be resolved.

2Because Ham saw the nakedness of his father Noah, this Biblical pronouncement

fell upon him and his descendants: "Cursed be Canaan [son of Ham]; a

servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. And he said, blessed

be the LORD God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant" (Genesis,

9:25-26 KJV). "Hamite" was a term applied to one of many African

groups, and Southerners concluded that it was through this Biblical

reference to Ham and his descendants that the curse of servanthood fell

eternally upon the Hamites, i.e., those of African descent. Clever, but

horribly flawed, logic – not to mention terrible Biblical exegesis

[analysis]! But it seemed to many Southerners to suffice as a

compelling moral argument.

Early political voices

John Quincy Adams

John C. Calhoun

After

serving as U.S. President, Adams returned to Washington in 1830 to

serve in the House of Representatives, where he became a very active

supporter of Abolitionism.

On

the other side of the issue,

Calhoun became the voice of the angry South, claiming even

Biblical support for slavery ... and supporting strongly the departure

of the South from the Union if slavery were in any way restricted or

outlawed.

|

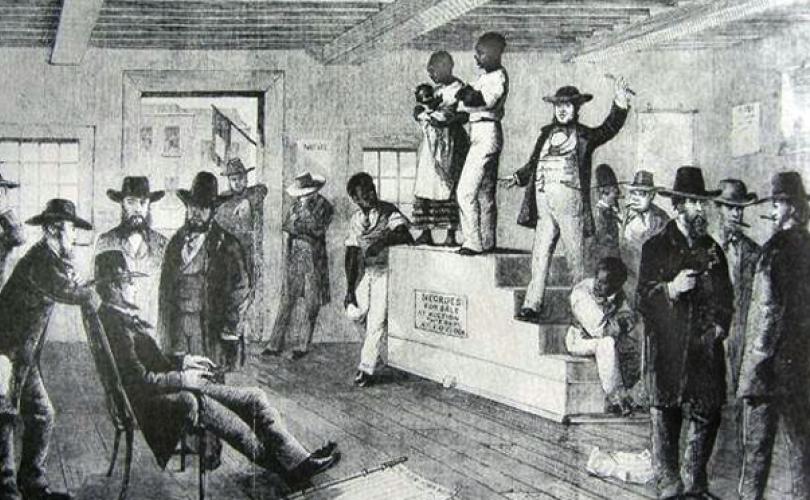

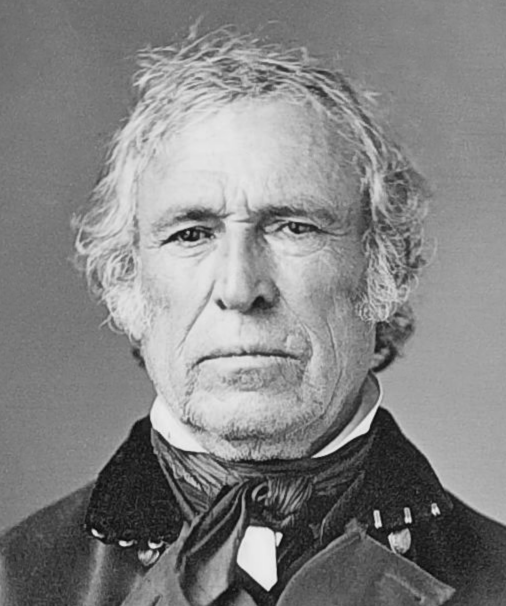

Zachary Taylor elected U.S. president (1848)

Clay now supposed that he had the Whig nomination

all sewed up as he approached the nominating convention in

Philadelphia. But the Mexican-American war had put General Taylor front

and center in the hearts of the American people, especially among a

younger generation that had less reverence for the Great Compromiser

Clay. Similarly, the long-standing political star Daniel Webster

suffered from the same loss of relevance to the younger generation.

Webster finally threw his support behind Taylor, who in turn offered

him the position as his vice presidential running mate, which Webster

declined (though when Taylor died sixteen months into his presidency,

Webster would regret not having taken up the offer). So Taylor turned

to the strongly anti-slavery New Yorker Millard Fillmore as his running

mate.

Taylor's political views were largely

unknown. He was a Kentuckian and a slaveholder (a rather unusual social

profile for one who confessed himself to be a Whig), though he seemed

to have no strongly-held views on the issue of slavery. He was a

soldier first and foremost, a strong American nationalist, and a

national hero. And that is what the American people found so appealing

about him.

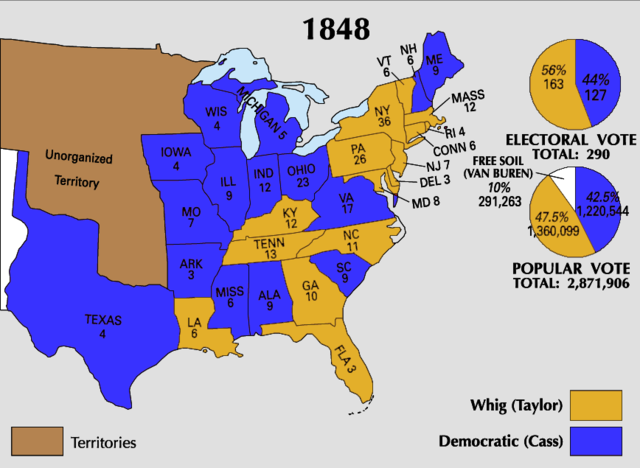

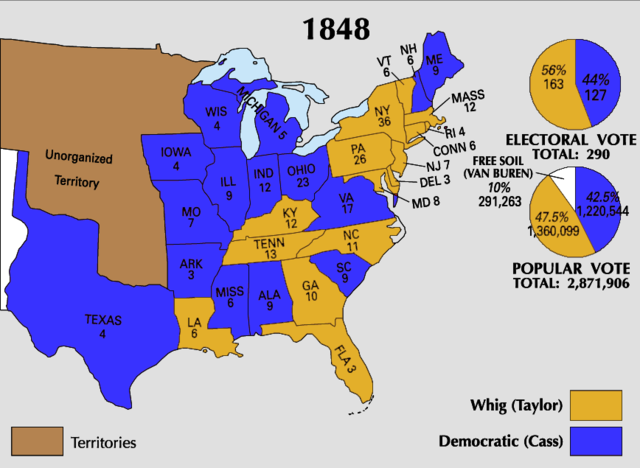

Running against the Whigs was a new face

in the competition, a new third party, the strongly Abolitionist Free

Soil Party, which ran Van Buren as its presidential candidate (actually

drawing about ten percent of the national vote). And, as usual,

opposing the Whigs – but also now the Free-Soilers as well – was the

pro-states'-rights Democratic Party, with its strong Southern support,

which ran Lewis Cass as its presidential candidate.

In the election itself, in which the

voter turnout was quite light, Taylor won a slight (five percent)

majority of the popular vote, although he ultimately received 163

electoral votes to Cass's 137 votes in securing for himself the U.S.

presidency. All in all, the election was a clear indication that the

nation was ready for a break from the tensions of the Mexican-American

war and the slavery issue. But sadly, the latter was not destined to be.

|

Zachary Taylor

Millard Fillmore

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

The Abolitionist Movement

The Abolitionist Movement