4. THE FORMATION OF CHRISTENDOM

CONSTANTINE ... AND THE "ROMANIZATION" OF CHRISTIANITY

CONTENTS

Constantine and "imperial" Christianity: Constantine and "imperial" Christianity:

An overview

Constantine's rise to power Constantine's rise to power

Constantine takes up the Christian Constantine takes up the Christian

cause

Constantine's assistance in organizing Constantine's assistance in organizing

Christian doctrine

The Constantinian legacy The Constantinian legacy

The textual material on the page below is drawn directly from my work found in

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 140-149.

CONSTANTINE

AND "IMPERIAL" CHRISTIANITY: AN OVERVIEW |

In

312 the Roman emperor Constantine dramatically swung his support behind

the Christian faith. And soon under his successors, in accordance

with typical Roman political logic, the rest of the Roman Imperium felt

compelled to do the same. Thus Christianity moved from persecuted

status, to the position of being the official state religion of the

Roman Empire, to the point of becoming itself the source of rigorous

persecution of religious "heretics" – in the Roman urge to force even

intellectual uniformity upon its far-flung political order. In

312 the Roman emperor Constantine dramatically swung his support behind

the Christian faith. And soon under his successors, in accordance

with typical Roman political logic, the rest of the Roman Imperium felt

compelled to do the same. Thus Christianity moved from persecuted

status, to the position of being the official state religion of the

Roman Empire, to the point of becoming itself the source of rigorous

persecution of religious "heretics" – in the Roman urge to force even

intellectual uniformity upon its far-flung political order.

This event was to have a profoundly transforming impact on

Christianity. Christianity at this point (300 years after its founding)

ceased to be solely a private faith of the people before their

God. Instead it was refashioned by the imperial authorities to

serve as the moral-ethical foundation for the entire Roman

empire. Instead of Christianity being a movement of the human

heart beyond the circumstances of this life – it became a way of

disciplining the human heart to the priorities of this life –

particularly priorities as set down by the Imperial authorities.

Thus one of the major things that had made Christianity so appealing to

the multitudes was taken away from it by its being coopted into the

Roman Imperium. It no longer could serve as a direct line to God

for those who were looking in hope for a way out from under the heavy

load of the Roman social order.

Christ was now thought of more as the friend of emperors and co-regent

with them over the empire – than as the friend and personal savior of

the people. In consequence, Mary (mother of Jesus) came to fill

that role of personal friend – as the "Mother of God," (Greek:

Theotokos) in the fashion of the still-popular Earth Mother cults

that had been banned by the authorities. Likewise, the highly

venerated Christian "saints" replaced the other banned pagan gods as

special protectors of the common people in their various enterprises in

life. God and Jesus, Father and Son, had lost out in the hearts of the

people as the source of their personal hopes.

And

personal salvation was no longer a matter of personal faith in God's

son, Jesus. Instead salvation came through the ministrations,

especially of the sacraments by the priestly officers of the official

Church.

|

CONSTANTINE'S

RISE TO POWER |

We

return to the point where we left off in the earlier account of the

Roman emperors. It was 305 when Diocletian and Maximian had

stepped down as co-emperors (Augustuses) – elevating the two Caesars,

Galerius and Constantius, to the positions of Augustus. Maximian

and Constantius were expecting their sons, Maxentius and Constantine

respectively – as the generally expected heirs to power – to be named

by Diocletian as the new Caesars. But instead, apparently under

pressure from Galerius who had his own followers he was promoting,

Diocletian named Severus and Maximinus (no relation to Maximian or

Maxentius) as the new Caesars. Trouble began immediately.

Neither Constantine nor his father, Constantius, the new Augustus of

the West, were willing to accept this decision bypassing

Constantine. Constantine had been raised in the Eastern court

under Diocletian as something of a hostage to ensure Constantius's

total cooperation with Diocletian. With Galerius now occupying

the position of Eastern emperor or Augustus, Constantine knew that his

life was in great danger if he remained in the East. He escaped

to Britain in the West and joined his father (the Western Augustus),

keeping himself busy and building his own military reputation at his

father's side in fighting the troublesome Celtic Picts. But his

father shortly became sick and was clearly dying (306). Something

bold needed to take place if Constantine were to survive without his

father's protection.

Just before his death his father declared Constantine his replacement

as Augustus, angering Severus (who expected Galerius to name him as

Western Augustus) and infuriating Galerius. But Galerius knew he

had to accept some kind of legitimate place for Constantine – or face

war with a young military leader of a fast-growing reputation (the

legions not only of Britain but also Gaul now stood behind

Constantine's claim to the title of Western Augustus). Instead,

Galerius named Constantine to the lesser position as "Caesar" –

although Constantine continued to refer to himself as "Augustus."

At this point Constantine's generally recognized rule extended over

Britain, Gaul (modern France) and Spain – and put at his disposal one

of Rome's largest armies.

Constantine began an impressive series of works projects – importantly

centered on Trier, Rome's administrative center in the northwest near

the German border. From this point he put the Germans on notice

that he would tolerate no more German incursions across the border into

Gaul. He and his father had already pacified the Alamanni, the

German tribe which had been the biggest danger to Gaul during the

previous half century. Constantine then went on to crush the

Franks, who had also been a major problem along the border.

Constantine's reputation began to grow considerably.

Meanwhile Maxentius had grown resentful of Constantine's increasing

popularity – and his own failure to be named by Galerius to any

imperial title. From his position in Italy he ultimately declared

himself emperor (306) – and immediately found himself in battle against

both Galerius and Severus (Maxentius conquered and imprisoned Severus,

taking him out of the contention for emperorship). Supposedly

Constantine was to be Maxentius's ally. But Constantine carefully

avoided involvement in his rebellion – despite Maxentius's father

Maximian's efforts on behalf of his son to connect Constantine with

Maxentius (and despite Constantine's marriage to Maximian's daughter

Fausta). A compromise of sorts was finally reached when Galerius named

Maxentius and Constantine as assistants to the Augustus – but appointed

an ally, Licinius, as Augustus in the West. Constantine largely

ignored this decision, continuing to refer to himself as the Western

Augustus.

At this point (310) Maximian decided to come out of retirement – and,

claiming to a contingent of Constantine's troops (that Constantine had

assigned Maximian to lead in South Gaul while Constantine himself was

fighting Franks in the north) that Constantine had been killed in

battle, Maximian declared himself emperor again. But Constantine

was most decidedly not dead – and his troops largely declined to honor

Maximian. Now a war between two former allies swung into full

action. Maxentius joined his father. But Maximian was soon

captured – and Constantine offered him the more honorable death of

suicide – which Maximian accepted.

Meanwhile Galerius grew very sick and soon died. Into this

political vacuum in the East moved both Maximinus (Galerius's former

Caesar) and Licinius (the supposedly Western Augustus) who seemed

determined to depose each other. At the same time tensions began

to increase in the West between Constantine and Maxentius.

In all of this the Christian community was beginning to play an

increasingly important role in Roman affairs. The horrible

persecution under Diocletian – and possibly even worse under Galerius –

had simply sifted out the weak of heart among the Christians, and left

the remainder strengthened in character – and enhanced in stature among

increasingly admiring Romans. Just before his death in 311

Galerius had decreed an end to the persecution of Christians – although

Maximinus ignored the decree and continued their persecution in the

East. In Italy Maxentius attempted to woo them to his side by

allowing the Christians to elect a new Bishop of Rome. But

Constantine was not unsympathetic to the Christian cause himself.

His father had been tolerant of them as emperor in the West and his

mother Helena was a fully practicing Christian. Constantine

himself seemed to have some interest in the faith – though at what

point and how much early on is difficult today to determine.

|

CONSTANTINE

TAKES UP THE CHRISTIAN CAUSE |

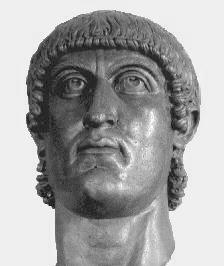

Head of Constantine's Colossial

statue - Emperor (306-337)

Musei Capitolini -

Rome

|

The Battle of Milvian Bridge

A massive civil war was shaping up as Constantine formed an alliance

with Licinius – and Maxentius formed one with Maximinus. In 312

the war broke out in full. Italy became the scene of the worst of

the encounter as Constantine crossed the Alps to attack Maxentius in

Italy. Step by step Maxentius was pushed back. Along the

Tiber in October of that year just outside of Rome at the Milvian

Bridge the two forces took their final stand.

According

to the account of the contemporary Christian historian

Eusebius (the story varies slightly from one ancient source to

another), Constantine went into battle with a distinct Christian

symbol painted on the shield of each of his soldiers, presumably the labarum, made up of the superimposed Greek letters X (Chi) and P (Rho), representing Χρίστος, that is, the name Christos

or Christ. Constantine told his troops that Christ (or a

heavenly voice) in a dream the night before the battle had instructed

him to go into battle with that painted on their shields ... under the

command Eν Toútω Nίka2 ... "in this, conquer." According

to the account of the contemporary Christian historian

Eusebius (the story varies slightly from one ancient source to

another), Constantine went into battle with a distinct Christian

symbol painted on the shield of each of his soldiers, presumably the labarum, made up of the superimposed Greek letters X (Chi) and P (Rho), representing Χρίστος, that is, the name Christos

or Christ. Constantine told his troops that Christ (or a

heavenly voice) in a dream the night before the battle had instructed

him to go into battle with that painted on their shields ... under the

command Eν Toútω Nίka2 ... "in this, conquer."

And conquer they did. The result the next day was a rout of

Maxentius's army – despite the fact that his army was twice the size of

Constantine's army. Maxentius was drowned in the Tiber amidst the

panic. And Constantine was now able to enter Rome an Augustus in

fact as well as in name.

And very importantly, this event would ultimately be interpreted as a

battle waged by the Christian God as well as by the Roman legions

themselves.

The Edict of Milan and the final path to sole rulership

The

next year Constantine and Licinius (Licinius, although actually the

Western Augustus, found himself in charge of huge regions of the

Eastern Empire as well) met in Milan and formed an alliance, sealed

with the marriage of Constantine's half-sister to Licinius (March

313). At the same time, they jointly published the Edict of

Milan, announcing the end to all religious persecution in the Empire

and restoring all the property seized during the Diocletian/Galerian

persecutions.

But Licinius had to leave abruptly

for the East as news reached him that the Eastern Emperor Maximinus was

organizing a revolt against him. Maximinus was defeated (April

313), leaving Licinius finally unchallenged in the East. With

Maximinus out of the way, Licinius was able to take full command of the

East … and agreed to let Constantine have command of the West.

But

politics being politics, it was inevitable that these two political

giants would fall into conflict. Thus over the next ten years

they fought, then found a way to peace, then returned to battle,

etc. On and on it went, one thing after another stirring a new

round in their contention. Meanwhile, Licinius also found himself

deeply caught up in battle with the Sassanid Persian Empire to the East

of the Roman Empire … and Constantine the same with the troublesome

Sarmatians and Goths to the North and East … Constantine going after

them into territory that Licinius considered to be his realm.

This then provoked an all-out war between the two emperors (324) …

fought at the very walls of Byzantium and then at Chrysopolis … where

Licinius was defeated and imprisoned – and executed the following

year. Constantine was thus the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

The first Christian emperor – and the foundation of "Christendom"

But

Constantine's interest in Christianity now became a much greater matter

than mere toleration of the faith. Clearly, Constantine saw in

this faith the foundations of a revitalized moral order that had been

lacking in Rome for centuries … and that Diocletian's recent efforts to

put a stronger order under Rome through political reform at the top had

brought no particular improvement – perhaps even a worsening of the

very divisive political situation Rome had been experiencing for

decades … even centuries. No … Constantine was deeply determined

to bring Rome back to good order through the virtues of the Christian

faith. And basically he succeeded.

That meant having to decide what parts of the widely diverse doctrines

associated with Christianity were to be upheld as critical to this new

Roman-Christian order … and what parts were to be dismissed – even

suppressed. After all … the central issue for Constantine was

about social order.

But other influences that came from outside of the original founding of

the faith in Jewish Palestine should possibly be accommodated –

especially in the way they spoke clearly to the hearts of the commoner

Christians. While these stood outside of the canon of Scripture,

they certainly could be accommodated by some degree of religious

"expansion" of the original faith.

Constantine as Pontifex Maximus.

Constantine made it very clear early on in his rule that he was to be

seen as more than just a political ruler. He took for himself the

title Pontifex Maximus ("High

Priest") – not however as someone intending to lead in some form of

traditional temple sacrifices … but simply and clearly as the ultimate

"Protector of the Faith." If Rome was to be a religious empire as

well as a political empire, it would have to be made clear that he was

as much the head of the religious portion as he was of the political

portion of the Empire. That was very Roman of him. But what

that had to do with Jesus was not entirely clear.

2En touto Nika ... later translated into Latin as, in hoc signo vinces.

From an 800s Byzantine manuscript showing Constantine at Milvian Bridge

conquering under the sign of the cross ... engraved with the Greek inscription ἐν τούτῳ νίκα

(En touto Nika – "In this conquer" ... its Latin equivalent: In hoc signo vinces)

CONSTANTINE'S

ASSISTANCE IN ORGANIZING CHRISTIAN DOCTRINE |

|

The Donatist controversy

Within six months of his victory at Milvian Bridge Constantine was

asked by the Donatists in North Africa to intervene in their dispute

with "apostate" bishops (ones who under the pressure of the Diocletian

persecutions had denied their faith). The Donatists refused to

recognize the authority of these bishops to administer the sacraments

(ordination, baptism, the eucharist or Lord's Supper, etc.). In a

way the question was one of works versus grace, or successful

self-discipline versus the forgiveness for failure. The vast

majority of the catholic ("universal") or orthodox ("correct-thinking") bishops3 were opposed to the stance of the Donatists.

The Catholic/Orthodox view favored the forgiveness of the fallen

bishops. This was, after all, one of the key principles of the

faith.

Constantine

finally did intervene in 314 – but took the Catholic/Orthodox position

and found in favor of the compromised but restored bishops against the

Donatists, and ordered the Donatists to submit to the authority of

these bishops.

But the Donatists would have none of it. The Donatists had,

after all, stood the test of persecution and could see no reason to bow

to the authority of those they saw as having conveniently (albeit

briefly) denied their faith in order to save themselves from the wrath

of Diocletian. Moreover, the Donatists had faced the

hostility of emperors before without yielding – and they felt no need

to start doing so at this point.

The results of defying the emperor – even a Christian emperor – had

predictable results. In 317 Constantine sent troops to North

Africa to force the Donatists into submission to his decision, thus

setting off the first instance of Christians persecuting other

Christians because of differences in the way they interpreted their

faith. A large number of Donatists were banished – though

ultimately even this did not bring the Donatists into compliance, so

tough was their stance. Indeed, it was not until the Muslim

conquest of North Africa in the 600s that the Donatist movement finally

died out!

The Arian controversy – and the "Nicene" decision

Then

there was the matter – one that would never really go away over

Christianity's long history – of Trinitarianism versus Unitarianism.

A works-versus-faith dispute had developed between Alexander, Bishop

of Alexandria, and a presbyter (priest) of his, Arius. Arius was

a strong advocate of the Monarchian or "Unitarian" position … which saw

Jesus as attaining divine or godly status only upon his arrival in

heaven – as something of a reward for his Messianic work while on

earth. In other words, while on earth Jesus was not part of the

godhead, not really the Logos of John – but simply a Messiah or Christ

called by God to exemplify the perfect Christian life. Jesus was

therefore not a God fully able to pay for the sins of all humankind on

a Roman cross – but simply an outstanding moral example. True, he

now could be considered something of a god … although of derivative or

lesser standing than the sole eternal God of heaven. And as for

the Holy Spirit … Arius as a Unitarian had little thought on the matter

– since it was by man's own decision, rather than by some kind of

intervention of a Holy Spirit, that the test of faith was to be lived

out. Righteous works of a holy man or woman – following the high

moral example set by Jesus as the Christ – was, to the Unitarian such

as Arian, what Christianity was ultimately all about.

In response to Arius, Alexander requested a hearing on the matter

before Constantine, resulting in the Council of Nicaea of 325 …

Constantine presiding. Alexander and the "Trinitarians" saw

"God" in three different manifestations or "persons": God the

Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit – "Three in One" … all of

a single God-nature, but relating to humankind in three different ways

or roles.

Thus the Jesus that died on the cross was not merely a morally perfect

individual but indeed God himself. The sins of a good man – even

a perfect man – could possibly atone or pay for the sins of others … at

least a few others. But only a God dying on that cross could pay

for the sins of all humankind.

And as all humans are guilty of "original sin" – inherited from their

ancient ancestors – sin would be a problem they would struggle with all

their lives on earth. No one was perfect … as Christ made clear

when he rescued the woman purposely caught in the act of adultery (John

8:1-11) by challenging those without sin to throw the first stone in

her death sentence. But recognizing their own sinfulness, the

accusers, starting with the oldest and wisest of the gathered

"enforcers" quietly exited from the scene. Thus to the

Trinitarians – we are all sinners … despite our efforts to atone for

our sins or redeem ourselves through our good works. Only God can

offer such atonement.

Furthermore, faith itself is not earned or achieved through human

effort … but solely as a gift of God given to us … a wonderful mystery

of God's pure grace (Romans 8). Claiming that such faith is a

human achievement is a sad attempt to substitute human works for God's

grace.

In any case, there was no way that Arius was going to win that contest

… for the vast majority of the Christian bishops and presbyters or

priests were strongly supportive of the Trinitarian view. And for

good reason. Holy Scripture (the Bible) clearly supported the

Trinitarian understanding of the Divine Dynamic!

Thus resulted the Nicene decision … and its Nicene Doctrine – and what

is often described as "Nicene Christianity" … another term for

Trinitarianism.

But the problem was that while the better-instructed of the Christian

community (the priests or clergy) would be able to come to such a

complex Trinitarian understanding of things, many of the commoner

Christians could not – or even would not. To them, religion was a

social duty … necessary for the good order in their lives.

Anything beyond that was too "intellectual," too lofty, for serious

usefulness in a person's daily life.

And being either of Greek, Roman, or even Semitic cultural background

would also play a role in this Trinitarian-versus-Unitarian

contest. The Greeks, already of something of a mystic mindset,

had less difficulty following Trinitarian logic. The Romans

perhaps had some difficulties in understanding such matters … but since

their ruling authorities supported the Trinitarian doctrine, being good

Romans, they did so as well. But the Semitics of Syria, Palestine

and Arabia would find themselves highly resistant to the complexities

of Trinitarianism (also too "Greek" for their tastes). And later,

when the German tribes would be absorbed into the Roman order, at first

they readily accepted Christianity – but in the simpler Unitarian

form. It would take some time before their tribal leaders

converted to Trinitarianism – with their tribes then being brought into

Trinitarianism along with them.

3Both

terms, "catholic" and "orthodox," were originally more or less

interchangeable – until gradually the term "catholic" tended to refer

to the Roman church in the West and the term "orthodox" tended to refer

to the Roman church in the East.

|

Constantine's impact on Christianity

Certainly it was Constantine that forged the "synthesis" between Rome

and Christianity that became Christendom. Whether or not he was

doing Christianity any great favor is a matter of great debate.

His own spiritual commitment to Christianity is itself debatable.

He continued to honor the Sun god, the Sol Invictus (understood at that

times as Helios or Mithras – or even Jesus), establishing Sunday as a

religious day of rest in honor of the Unconquerable Sun. He and

his mother Helena were builders of many churches – though they did so

in the fashion of those who built pagan temples: honoring them with the

name of some great saint – just as the pagans had done with their

gods. Constantine also found ways of honoring the old pagan gods

– for instance setting up a statue of himself in honor of Helios in the

Forum of Constantinople.

Church worship itself took on a more regal character under Constantine,

with worship services started up with elaborate processions into the

basilica-styled churches, complete with chanting and the burning of

incense by lavishly dressed officials. All worship was focused

forward – toward the elevated altar and chairs on which sat the

presiding priests or bishops, who performed most of the religious

duties in front of a passively arrayed congregation (much as the pagan

priests had operated).

His Christianity personally did not seem to have any softening effect

on some of the more chilling features of imperial rule: in the summer

of 326, for reasons not clear to us today, he had his oldest son

Crispus and his wife Fausta murdered.

His real impact however was in how his designation as a Christian made

the Christian faith now "politically correct." It made sense for

those seeking court favors and appointments from Constantine to also be

"Christian." Thus the church, once thinned down in membership by

intense persecution to only the most stalwart of the faith, was now

filled with multitudes whose motivation for being "Christian" was more

social or political than spiritual.

The episcopacy

For the first 300 years of its existence Christian communities had

remained small (usually even secretive) and organized only at the local

level under local elders or pastors and teachers ... much like the

Jewish communities from which Christianity was originally drawn.

But with Constantine's official Romanization of Christianity, a

bureaucratic structure was built over the Christian world ...

officiated by priests, led themselves by bishops, and the bishops

directed by archbishops or patriarchs. Eventually of the last

group, five would emerge to dominate the array of bishops and

archbishops: the patriarchs4

of: 1) Rome (also known as the inheritor of the Keys of St. Peter and

thus the Father of the faith), 2) Constantinople, 3) Alexandria, 4)

Antioch and 5) Jerusalem. Every effort of the five was made to

keep their responsibilities cooperative ... although different

political priorities in different parts of the Empire would eventually

cause these five religious bureaucracies to move along more independent

lines.

A shift in the sense of the nature and consequence of Jesus's ministry

A slow and almost imperceptible shift was also taking place in the

understanding of the significance of Jesus's death and

resurrection. In the early days of the church, the understanding

was that Jesus's death and resurrection – but particularly the latter,

his resurrection – was a very strong indicator of the end of the old

life … and the beginning of a new era: one produced by the Parousia

or coming of a new heaven and a new earth … supposedly in the very near

future. This is what emboldened early Christians in the face of a

world that proved not very accommodating to the Christian mission and

ministry. But … supposedly what the world took as its

justification in persecuting Christianity was ultimately of little

consequence to the Christian believer – because all of that was soon to

be swept away with Christ's second coming.

But with the "delay" of the Parousia

– generations now passing on without that all-critical second coming

taking place – a more tired or resigned spirit characterized the

Christian view of life's dynamics. The "evil" of the surrounding

world weighed ever-heavier on the Christian heart … more noticeable as

to being "the" problem that Christianity faced.

The cruelty of the world was very evidently well-symbolized by Jesus

nailed on the cruel Roman cross. And thus the crucified Christ,

rather than the resurrected Christ, became the image that Christians

increasingly held before them. Christ's larger purpose now seemed

to be to continuously suffer on that cross for the sins of humankind,

rather than lead or free people from those sins … like the Christ

rising from the grave.

Salvation through the priestly powers of the Roman Church

The burden of sin thus grew ever heavier as something that the

believers found themselves struggling with – something that their mere

personal faith no longer seemed to lift them above. They would

need help from some other source.

And that source increasingly became the Church itself.

Salvation once offered by Jesus Christ through the faith of the

believer, was now replaced by the idea that the priestly church,

through ritualized confession, formalized prayers, and ultimately the

dispensation of its seven sacraments by the hands of the officers of

the church (priests and bishops), was the source of a person's

salvation … and ultimately heavenly reward at death. So it was

that the Church and its religious offerings – and not the personal

faith of the believer – came to be understood as to what "saved" souls.5

The Blessed Virgin and the Saints

Also … an interesting Christian impulse that has no support in the

Christian Scriptures is the veneration of the saints – and the

veneration of Jesus's mother, Mary. As with the Greco-Roman

impact of Platonism on the Christian faith, so also some of the pagan

practices of the times of the Church's early formation seemed to have

helped early to shape features of Christian life and practice.

This became especially so after the outlawing by Roman authorities of

prayers to the pagan deities and the outlawing of the very widespread

Eastern worship of "Earth Mother" (Isis, Demeter, Astarte, Aphrodite,

etc.) in the 300s

.

The early Christian martyrs naturally stood as heroes – saints of a

special caliber – that naturally would be venerated for their

exceptional lives (and deaths). But the practice of praying to

them to intercede in performing special favors (safety in travel,

protection of the home, support in romance, etc.) also tended to mirror

the pagan practice of praying to certain deities known to have special

powers in these particular matters. So too now the saints were

prayed to – saints who were recognized to have particular powers in

this or that matter. Indeed, very early on, praying to the saints

became a quite common Christian practice.

Then

Mary began to loom large in the Christian heart … approached much

more often than Jesus in prayer for this matter or that. This practice

actually had an early start … as early as the time of Irenaeus (late

100s), who mentioned her important role in the act of salvation.

Little by little Mary gained importance as an intercessor between the

ordinary Christian and the awesome Jesus Christ … Jesus now seen as

Christus Rex – Christ the King – that is, as Jesus becomes loftier and

more distant. This becomes especially the case as Jesus takes on

the role of protector of the Roman imperium ... and of the emperors

themselves. Thus the common people's prayers are directed not to

Jesus but to Mary … especially when those prayers arise from concerns

and burdens brought on by Roman imperial authority itself.

Mary is soon even accorded the role as "co-redeemer" with Christ

… able of her own to bring salvation to the Christian. Then

finally, as a decision of the Council of Ephesus in 431, she was

recognized as not merely Christotokos – Mother of Christ – but even

Theotokos – Mother of God.

Soon churches were dedicated to Mary. And pictures of her – with

a sweet but rather helpless baby Jesus in her arms – hung at church

altars and in the homes of the faithful everywhere. It was thus

that she, not Jesus, became the primary redipient of the Christian's

prayers and praises.

This occurred throughout all Christendom, the Western or Catholic

("Universal") part of Rome … as well as in the Eastern or Byzantine or

Orthodox ("Socially or Legally Correct") part of Rome.

The division of Rome permanently into an "East" and "West"

Soon after Constantine's defeat of Licinius he began the work of

redeveloping the town of Byzantium, located at a very strategic point

along the narrows where the Black Sea begins to connect with the

Mediterranean, into a new imperial capital. This capital was not

intended to rival the old city of Rome (which was suffering terribly

from "inner-city" decay) – but to greatly exceed it. In a way

this brought the Roman command center closer to its border problems

with the Germans to the north (across the Danube) and the Persians or

Sassanids to the East. Strategically this made a lot of sense.

But this move to the East also worsened the status of the old city of

Rome all the more. About the only thing of note that still gave

some importance to old Rome was that its bishop located there typically

commanded the voice of all of Western Christianity ... something that

would come to have increasing importance to "Western Civilization" in

the centuries to follow.

4Also known as Fathers of the faith ... although the Father or Papa

or "Pope" of Rome was considered the "first among equals" – because he

was supposedly the inheritor of the legacy or "keys" of the first

bishop of Rome, Saint Peter – Jesus's preeminent disciple.

5This matter of

salvation offered by the priestly Church rather than through the simple

faith of the individual believer would ultimately surface a thousand

years later as a very divisive issue, splitting the Church into two

brutally hostile communities, the "Catholics" and the "Protestants."

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

Constantine and "imperial" Christianity:

Constantine and "imperial" Christianity: Constantine takes up the Christian

Constantine takes up the Christian Constantine's assistance in organizing

Constantine's assistance in organizing

According

to the account of the contemporary Christian historian

Eusebius (the story varies slightly from one ancient source to

another), Constantine went into battle with a distinct Christian

symbol painted on the shield of each of his soldiers, presumably the labarum, made up of the superimposed Greek letters X (Chi) and P (Rho), representing Χρίστος, that is, the name Christos

or Christ. Constantine told his troops that Christ (or a

heavenly voice) in a dream the night before the battle had instructed

him to go into battle with that painted on their shields ... under the

command Eν Toútω Nίka2 ... "in this, conquer."

According

to the account of the contemporary Christian historian

Eusebius (the story varies slightly from one ancient source to

another), Constantine went into battle with a distinct Christian

symbol painted on the shield of each of his soldiers, presumably the labarum, made up of the superimposed Greek letters X (Chi) and P (Rho), representing Χρίστος, that is, the name Christos

or Christ. Constantine told his troops that Christ (or a

heavenly voice) in a dream the night before the battle had instructed

him to go into battle with that painted on their shields ... under the

command Eν Toútω Nίka2 ... "in this, conquer."