4. THE FORMATION OF CHRISTENDOM

"POST-NICENE" CHRISTENDOM

"POST-NICENE" CHRISTENDOM

The follow-up on Constantine's

The follow-up on Constantine's"reforms" by subsequent emperors

The Post-Nicene church fathers

The Post-Nicene church fathers

The retreat into the deserts of the

The retreat into the deserts of the

hermits ... and the monastic movement

The textual material on the page below parallels or is drawn directly from my work found in

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 149-153.

THE

FOLLOW-UP ON CONSTANTINE'S "REFORMS" BY SUBSEQUENT EMPERORS |

THE "POST-NICENE" CHURCH FATHERS |

|

Athanasius

Athanasius (ca. 296-373) was deacon of the church at Alexandria, eventually becoming Bishop in 328. He managed to find himself in the middle of the growing Catholic Arian (or Trinitarian Unitarian) controversy that pulled at the empire. He was exiled 5 times – because of the fluidity of the court politics and the changing fortunes of this Catholic and Arian Christianity with the Roman Emperors. He first came to notice when he took up the cause of his Bishop Alexander against Arius at the Council of Nicaea (325) getting the Council to find in favor of his well argued position against the Arian position. On behalf of the Trinitarian cause he wrote profusely. Thus in his The Incarnation of the Word of God he states:

The "Cappadocian Fathers"

Three closely related individuals played a key part in refining and strengthening the Trinitarian or Nicene cause: Basil of Caesarea (ca. 330-379), his younger brother Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 335-394), and their close friend Gregory of Nazianzus (ca. 330-390). Again, their point was that the Trinity was a necessity for human salvation – for only God, not man, not even a good man, could put an end to sin. It was God, not a good man, that died on the cross. Ambrose

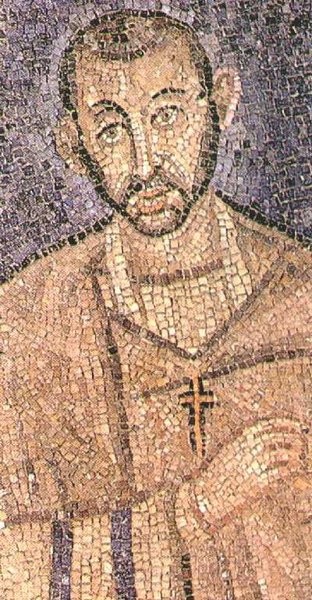

Ambrose (c. 340-397) was a Roman governor of the region centered on the key city of Milan ... who, in the midst of a tumultuous conflict between Trinitarian and Arian Christians, was called on to step into the recently vacated position as Bishop of Milan. He thus changed his role from secular to ecclesiastical governor ... and personally set a very high standard as to how the Christian life was to be lived. He gave up his fortune to the poor, and being an excellent scholar as a youth, took up the task of teaching the higher Christian life to his Christian flock in Milan by both word and example. He also became a "doctor" of the Church, writing and preaching with great skill in support of the Nicene or Trinitarian position. But this put him in a dangerous position ... as the imperial authorities of Rome were themselves still divided on the Arian or Unitarian versus the Nicene or Trinitarian issue. He however could be flexible on secondary issues, such as the proper liturgy to be followed in worship, and this probably saved him from being destroyed by the theological-political storms that constantly afflicted the times. |

– in the church of St. Ambrogio in Milan

AUGUSTINE (354-430) |

Cherbourg-Octeville, Musée Thomas-Henry

| Without

a doubt, Augustine was the most influential writer and thinker of the

late Roman Christian era. His work helped a wearied Roman Christian

culture accept the loss of its secular strength by focusing it on

transcendent "spiritual" realities. Augustinian spirituality not

only helped keep alive a certain sense of human virtue during the

coming "dark ages" but it also later served to help the church reform

itself in the 16th century. Augustine's early years

Augustine was born 354 in Thegaste in the Roman province of Africa (modern day North Africa). He had a pagan Father – but a Christian mother (Monica). He was very interested in philosophy (especially Cicero) as a youth – but also trained in Christianity. Nonetheless, he felt scandalized by the "unphilosophical" character of the Old Testament. Eventually he became Manichaean in philosophy – only later to abandon Manicheanism as being an inadequate philosophy. At age 30 (384) he became a professor of rhetoric at Milan, and delved into Neo Platonist philosophy. This he found made more sense. Evil, for instance, was not a separate "being" (as the Manichaeans professed), but rather the relative absence or lack of the Good – or something potentially Good which has been misused (such as an appetite which becomes gluttonous). At about this time, Augustine began attending the sermons of Ambrose, Bishop of Milan. Ambrose explained the Old Testament as allegory – helping answer some of the conflicts Augustine once had with the Old Testament. But he resisted Christianity because he thought that a "Good" Christian was expected to be celibate (he had a mistress and a boy by her) – but otherwise became increasingly attracted by Christian thought. In August of 386 he had a conversion experience in the garden where he lived: a childlike voice calling him to "take up and read." He took up and read Romans 13:13-14, which called for the abandonment of the urges of the flesh. From Platonic Reason to Christian Faith

This then began the journey for Augustine from personal redemption through the accumulation of intellectual knowledge (the former Platonic path) to now redemption through the simple faith in the spiritual powers emanating from God through Jesus Christ, spiritual powers that birth, direct and build the Good and True personal life – and ultimately the Good and True social life as well. The call to Christian ministry

He and a few companions formed up a study circle – to learn more of the Christian faith. But in 388 he returned to Africa – and attempted to lay low for fear of being detected – and being forced into becoming a cleric! But in 391, in a visit to Hippo, he was recognized and pressured to take up the office of presbyter or priest. Then in 396, when the bishop of Hippo died, Augustine took the position as bishop, retaining this position until his death in 430. Against Donatism

He eventually got embroiled in the Donatist controversy, still brewing since the early 300s (the Donatists continued to claim that the priests who under the pressure of the Diocletian persecution had denied their faith – and all those after them that had been brought to the priesthood under their anointing – possessed no legitimacy as priests; their priestly powers, especially in administering the sacraments, were void). By Augustine's time the on-going controversy had degenerated into a political struggle between Rome and the local purists in Africa who at that time dominated North African Christianity. Augustine employed his widely respected authority to argue on behalf of Rome against the Donatists. Ultimately he was influential in turning North African Christianity in allegiance to Rome and to Catholic or "universal" Christianity – away from local Christianity (of which there were a multitude of varieties). Augustine's main point was that the powers of the priest (the truth of the word they preached and the sacraments they administered) depended not upon the purity of the individuals holding the office but in the power of the office itself and the accompanying sacramental powers – which had God (or more specifically: Christ) as its guarantor, not man. Augustine stressed the importance of the work of the Holy Spirit – released through the power of Christ's cross – in cleansing Christian hearts. This was more important than a person's holiness achieved through self discipline. In this matter Augustine was simply reaffirming what the apostle Paul had said in the first century about similar matters. Against "Unitarian" Pelagianism

About the time Augustine managed to swing African Christianity to Rome, another major controversy was breaking hard within Christianity: the Pelagian controversy. Pelagius was a popular Christian teacher in Rome (around 400), who rather naturally stressed moral rigorousness as a necessary part of salvation. He easily gathered a group of followers who came to be identified as "Pelagians." The Pelagians – particularly those under the direction of Pelagius's rigorous disciple Coelestius – denied the doctrine of original sin and the necessity of Christ's atoning sacrifice on the cross for man's salvation. According to these Pelagians, salvation occurred through following the example of Jesus … in living by the Law. Augustine strongly countered Pelagian doctrine by stressing the divine initiative in salvation … by grace alone – because God first loved us. In short: because of our "original sin," there is nothing we can do on our own behalf for our salvation. Only by unmerited Divine grace extended by God to us – and received by us through our faith in God in Jesus Christ – are we saved.1 When the Visigoths invaded Rome in 410, Pelagius and his followers fled to Africa – though Pelagius himself soon moved on to Palestine; but many followers remained in Africa, troubling the Christian waters there. As Pelagius moved on to Palestine, Augustine sent word to Palestine to be on the lookout for Pelagius's heresy. But Pelagius denied that he held the same views as his disciple Coelestius. But the Pelagians stirred up so much trouble within Christendom that eventually the doctrine called "Pelagianism" was condemned as heresy by the Bishop of Rome in 418 and by a general council at Ephesus in 431 (the year after Augustine's death). Despite this action, Pelagianism – or "Semi Pelagianism" (through John Cassian) – continued to be very influential within Christendom. [Semi Pelagianism: God extends by His grace salvation to those who are well disposed or of good will toward Him. Thus people possess through free will the potential to choose salvation. But only God's grace, in response to this good will, can actually confer such salvation. However this still leaves man – not God – as the initiator of the act of salvation.2 The Visible and Invisible Church

In the early 400s Augustine began to develop a rather clear idea of the difference between the visible and the invisible church: the visible church included all professed Christians – some of which were Christian in name only. The "invisible" church was made up of only the true believers. And here, only God alone, who searches human hearts, knows who makes up this church.3 Human Sin/Divine Providence

In his own theology, Augustine strongly contrasted God's goodness (in creation) with human rebelliousness, man's habitual slavery to his passions. Unlike the neo-Platonists, Augustine saw sin in humans, not in the world of physical matter. Augustine had a strong sense of the total sovereignty/providence of a loving and gracious God. To Augustine, true freedom for man consists in the acceptance of God's grace – given to those whom God has called or elected to salvation (foreknown through God's eternal mind). But like the neo Platonists, Augustine understood that it is God who enlightens our souls – the portion of our being that is immortal and close to God (distinct from the body). We have no true knowledge apart from God's enlightenment or revelation. Thus, the highest act of a Christian is to lovingly desire God, to rest one's soul in Him. In God all things are to be found in truth and fulness. To focus one's desires on the world is to sell one's life short: exchanging the eternal for the temporary (amply demonstrated in his time in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 410). 1But Augustine added that only through baptism are people, even babies, saved from eternal damnation – an idea later downplayed by the Protestants of the 1500s. 2This ancient debate – divine grace versus human works as the path to salvation – already underway even before the days of Pelagius, continues to this day … in the form of "Unitarianism," which looks to man's good works to save himself, as opposed to "Trinitarianism," which sees a sinful man able to be saved only by the work of God himself in Jesus Christ … mediated by the empowering Holy Spirit – that is, by the gracious work of the Trinity: God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. 3This idea was quite novel at the time – but came to be widely accepted after Augustine. The Protestant reformer John Calvin, in the mid 1500s, pushed this concept strongly in his own doctrine of the church.

Walters Ar Museum - Baltimore

|