6. ISLAM AND THE WEST DURING THOSE DARK DAYS

DECLINE ... AND RECOVERY IN THE WEST

CONTENTS

The Carolingian legacy is carved up – The Carolingian legacy is carved up –

according to Salian law (mid 800s)

The Holy Roman Empire ... and the The Holy Roman Empire ... and the

Papacy

The Viking onslaught The Viking onslaught

French Normans bring Saxon England French Normans bring Saxon England

under feudalism

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 216-226.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

1. The Carolingian Empire breaks up / Islam in Spain / Investiture Controversy

814 Charlemagne dies ... bringing his son Louis the Pious to power as emperor

840 Louis dies and his sons now fight over the Carolingian Empire

843 With the Treaty of Verdun, Louis's sons divide up (and

weaken) the Carolingian Empire

Charles

gets the Western portion (future France),

Louis gets the eastern

portion (future Germany)

The "primary" central

portion (Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy) or "Lotharingia"

– and the emperorship – goes to his eldest son Lothair

But Lotharingia will be the least easy to unite and

govern

912 Abd al-Rahman III is able to unify al-Andalus and NW Africa

The region

comes to greatness … even Christian admiration

962 Saxon king Otto I the

Great is awarded the imperial title by the pope

after having

defeated the Magyars (Hungarians) and then taken control in Italy

... ending the reign of successive Carolingians

This now raises the question of how the imperial title is

to be awarded …

and by whom (the "Investiture Controversy"

of the 1000s)

1002 After al-Mansur died (1002) al-Andalus begins a

steady decline

1031 Al-Andalus breaks into a number of competing taifa

and the

Umayyad caliphate comes to an end in Spain

The Spanish Reconquista gathers momentum

El Cid (al Sayid) Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar serves both Muslim

and hristian lords

(second half of the 1000s)

1077 Pope Gregory VII takes the power of investiture against Henry IV

…

forcing him

to submit most humiliatingly at the Castle of

Canossa

1122 Finally with the Concordat of Worms, emperor

Henry V

agrees to leave the appointment

of church officers

to the church ... ending the Investiture Controversy

2. The Vikings (or

"Northmen" … or "Normans")

793 A Viking raid, destruction and slaughter at

Lindisfarne Abbey (northern England)

begins the Northman terror of the coastal

Christian West

835 A second Danish Viking attack takes place ... bringing Danish

settlers to central Saxon

England (the Danelaw) and making such attacks now a regular feature

of English life

840 Carolinian infighting gives the Danes opportunity to

attack France

… even send

longboats up the Seine to burn Paris

876 One of these raiders, Rollo,is able to take control

of Rouen in the heartland of what will

become "Normandy",

Rollo marries a local French aristocrat … at the

same time

working

with

Guthrum in England – becoming a powerful local warlord in the process

878 Wessex king Alfred the Great (871-899) rallies the

Saxons against Guthrum's Danes

(878-880) … Guthrum finally agreeing

to peace

But other Viking attacks continue … keeping Alfred

busy preserving

and uniting

Saxon England – both the North

(Northumbria) and the South

of England

885 The Daneshit France (885) with a huge army … but the

French hold them off at Paris

888 Count Odo (888) becomes King of West Francia … ending

Carolingian rule there

911 West Francia King Charles III decides to accept

Rollo's rule in coastal France

(Normandy) … understanding that

"Duke" Rollo would

then

protect that

strategic eastern coast from further Viking raids.

Thus the "Normans" of Normandy are quickly Romanized (Christianized) – and

brought into Western political-military

service

988 Off in the East, Viking (Rus) leader Vladimir of Kiev

converts to Byzantine Christianity

Vladimir dominates

East Europe

1000 Sweyn Forkbeard is able to regain his position as

Danish king

against the opposition

of the kings of Sweden

and German

Saxony …

1003 Sweyn then take on English king Aethelred

the Unready

for his attacks on Danes

in the Danelaw

(1003-1013) …

1013 Sweyn is so successful that the English recognize him as their king

1014 Sweyn soon dies

1016 Sweyn's son Cnut the Great eventually takes over his father's extensive kingdom

…

including England (1016)

and Norway and southern Sweden (1018-1028)

1035 Cnut dies peacefully ... having assembled a major kingdom

1042

But his huge kingdom is divided into

smaller units, allowing a Saxon of Wessex,

Edward the

Confessor, to become

English king … though Edward was more interested

in piety rather than

power … weakening his 24-year rule (1042-1066)

1066 Edward's place is taken by Saxon Earl Harold Godwinson …

challenged by

Norman Duke

William of Normandy ... who sends a huge fleet to England to

defeat an

exhausted

Harold at the Battle of Hastings ...

bringing England under French

Norman rule (and feudalism)

|

THE CAROLINGIAN

LEGACY IS CARVED UP IN ACCORDANCE WITH SALIAN LAW (mid-800s) |

Europe at the time of Charlemagne's death in

814

Wikipedia - "Treaty

of Verdun"

|

Louis the Pious (814-840)

In 813 Charlemagne had his only surviving son Louis the Pious (king of

Aquitaine) elevated to the position of co-emperor with himself ...

shortly before he died at the beginning of 814. Louis had gained

a lot of experience holding the Carolingian line against the rather

rebellious Basques and the expansive Islamic Moors of Spain ... Louis

even led the Carolingian expansion across the Pyrenees in Northeastern

Spain (Catalonia ... or the "Spanish March"). He also was

redirected at one point to fight alongside his father at Beneventum in

Italy.

Nonetheless, Louis grew up understanding that he was to share his

father's empire with his brothers, Charles the Younger, who was

expected to take the emperorship and the heart of the Empire, and

Pepin, who would rule over the Carolingian lands in Italy. But

both brothers died just shortly before their father did (Pepin in 810

and Charles in 811) ... leaving Louis little time to get ready to take

over his father's huge realm.

Upon arriving at Aachen to take over the realm, one of the first things

he did was move swiftly to remove potential sources of challenge to his

rule – relatives mostly, and women was well as men – largely by forcing

them to take monastic orders and sending them to nunneries and

monasteries ... or at least priestly positions within the Church.

But he would still have problems ... not only among independent-minded

dukes but over the question of inheritance among his sons –

particularly after he nearly died in an accident in 817, and decided to

publish a will outlining his inheritance among his three sons.

His oldest son Lothair was to receive the imperial title and the

greatest portion of the Empire. Pepin was assigned Aquitaine and

Louis was assigned Bavaria. Furthermore, in accordance with

Salian law,1 the

children of his own sons were then to receive the right to their

fathers' lands. Supposedly all this then provided for an orderly

transfer of the realm in case of his own death.

That was not to be. It became virtually the declaration of war

among his sons as they maneuvered to improve their inheritance ...

mostly against Lothair and his privileged position in all this.

But in fact the first person to rebel against this assignment was a

nephew Bernard, who realized that he was destined to lose his position

as King of Italy (received from his deceased father Pepin). When

Louis moved his army toward Italy, Bernard surrendered to his uncle ...

only to have himself tried and condemned to death for treason ...

although Louis had the sentence reduced to blinding – which nonetheless

caused Bernard to die from his wounds a few days later.

Subsequently (822), Louis became extremely penitent for his actions

against his nephew and appeared before the Pope and a gathering of

bishops and noblemen to repent of this great sin. His penitence

included the release of noblemen sent to monasteries ... sources of

future problems. The act of "piety" also made him appear merely

weak in the eyes of his people.

In 820 he remarried after the death of his wife two years earlier ... and soon (823) had a fourth son, Charles,

from this marriage. He thus revised his will, granting Alemannia

to Charles in 829 ... taking it from Lothair's inheritance. At

this point his empire fell into civil war, the brothers, joined by

other political and ecclesiastical (Church) figures, maneuvering to

improve their positions in this scramble for position in the

empire. When Louis promised greater portions of the empire to his

sons Louis and Pepin (also taken from Lothair's designated portion) the

brothers then joined him against Lothair ... and Louis was finally able

to end the rebellion (830).

But the "peace" was shaky ... and war broke out again in 832 ... with

Louis reassigning lands in an attempt to control the conflict – merely

making things worse for himself. He was finally defeated by his son

Lothair (833) ... and forced again to do penance when Louis was

abandoned by his supporters. He thus also was forced to give up

his throne. But Louis's humiliation brought out his supporters in

force, and the next year (834) Lothair was forced to step aside to let

his father resume his throne. Lothair ended up losing all but

Italy as his realm ... but the family finally was reconciled (836) ...

just in time to meet a new problem: Viking attacks coming from the

North (beginning in 837). Louis was quick to construct a new navy

... to protect Frankish interests in the North Sea.

Another effort by Louis to reapportion the inheritance of his realm in

837 brought forth yet another or "third civil war." Louis's

massive increase in Charles's inheritance once again sparked rebellion

among Charles's brothers (and opened the way for more Viking

mischief). This time, with Lothair's help, Louis was able to put

down the rebellion (840) ... not that Louis was able to long enjoy the

fruits of his victory, for he died that same year.

The Treaty of Verdun (843) dividing the empire

With their father dead, the three surviving brothers – Lothair, Charles,2

and Louis (Pepin had died in 838) – once again turned on each

other. Lothair claimed the entire inheritance ... minus

Aquitaine, which he assigned to his nephew Pepin II. But neither

Charles nor Louis acknowledged Lothair's claim and war broke out again

among the brothers. In 841 Charles and Louis defeated Lothair at

the Battle of Fontenay ... and the following year (842) they were so

bold as to declare Lothair unfit as emperor. At this point

Lothair was willing to yield to negotiations held at Verdun.

The results of the negotiations were that Louis was awarded

sections of the Empire East of the Rhine River, Charles the Western

sections of the Empire, and Lothair a central strip of land – one

reaching from the Netherlands in the North, then south along the

Western bank of the Rhine ("Lotharingia" or "Lorraine"), then

Burgundy and Italy in the South … plus the right to keep his imperial

title.

Whereas Lothair's territory lacked any centralizing tendency (plus

having the grand impediment of the Swiss Alps positioned in the

middle), Louis was able to take control of a land that would remain

culturally largely "German" (thus his title, "Louis the German').

At the same time Charles's more Latin-based Western territory would

become the foundation for the country of France.

This division would weaken greatly the peace, stability and prosperity

of the Carolingian Empire ... gradually driving Northern Europe back

into something of another "Dark Age" ... especially with the Vikings

taking advantage tremendously of the disunited and thus greatly

weakened Empire.

1On

the other hand, in England the Saxons practiced primogeniture, in which

the oldest son inherited all of the father’s lands. That

certainly was viewed as unfair by the other sons ... but it kept the

work and thus inheritance of the father intact from one generation to

the next. The Salian law of the Franks was "fairer" to the sons

... but left the father’s legacy greatly weakened when it was divided

fairly equally among his sons. However, the Franks eventually

were forced to adopt primogeniture as the only serious solution to the

problems caused by a constant dividing of the family’s feudal

inheritance.

2He would

eventually come to be known as Karolus Calvus, Charles the Bald ...

although it had nothing to do with his hair ... of which he always had

plenty! Speculation today is that instead it was in reference to

the fact that at one time he was a son without any holding of

land. But no one knows for sure why the title.

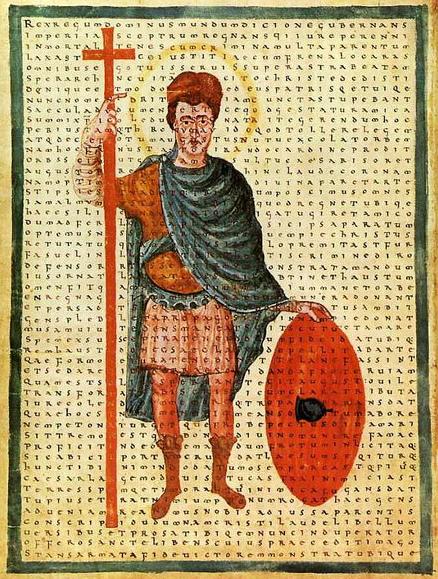

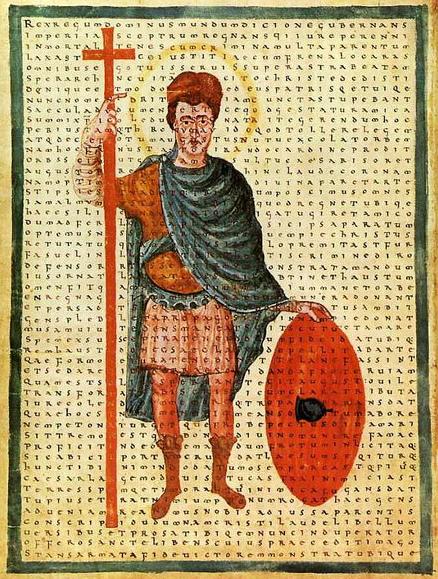

Louis the Pious -

Charlemagne's

son and successor - ruled: 814-840 ... contemporary depictions from 826

as a miles Christi (soldier of Christ) with a poem of Rabanus Maurus

overlaid

The three-part division of

Charlemagne's Empire in the 843 Treaty of

Verdun

Wikipedia - "Treaty of

Verdun"

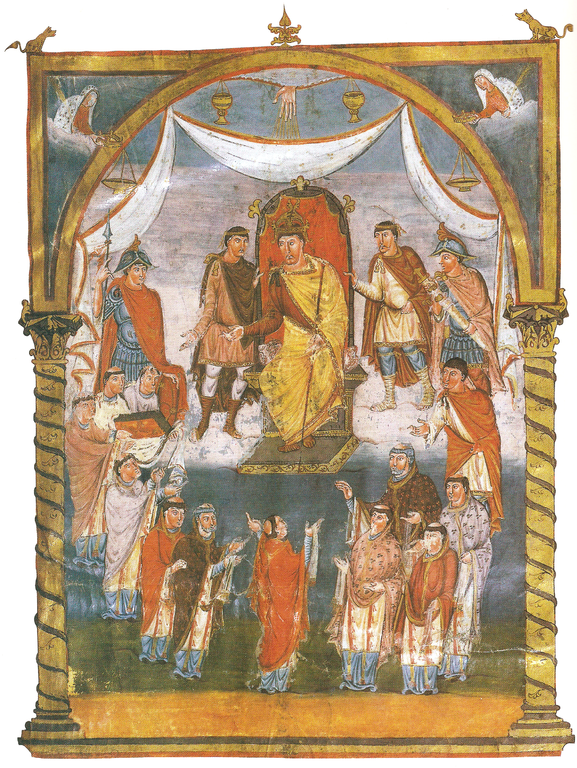

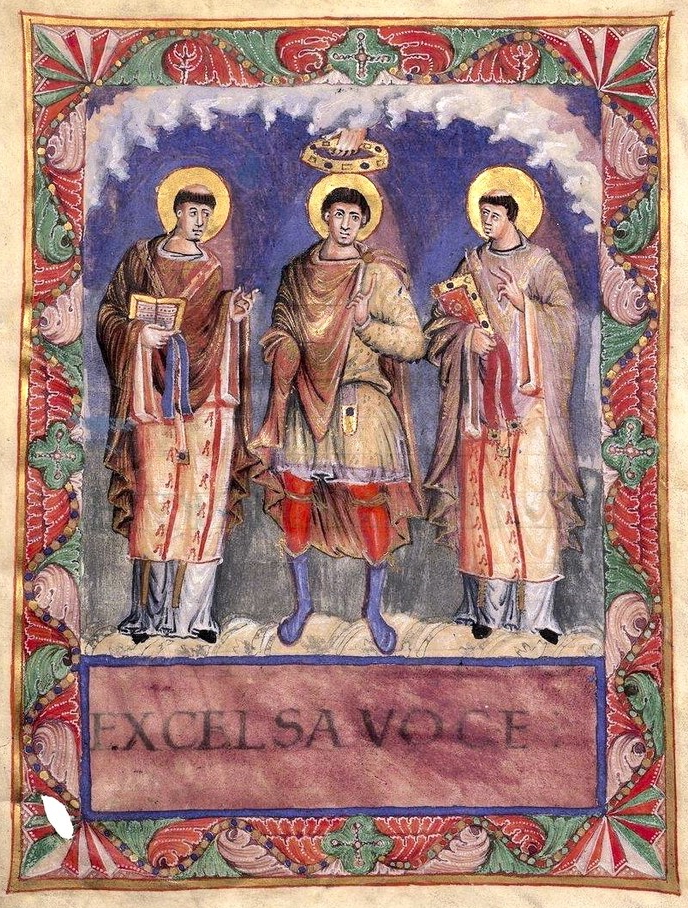

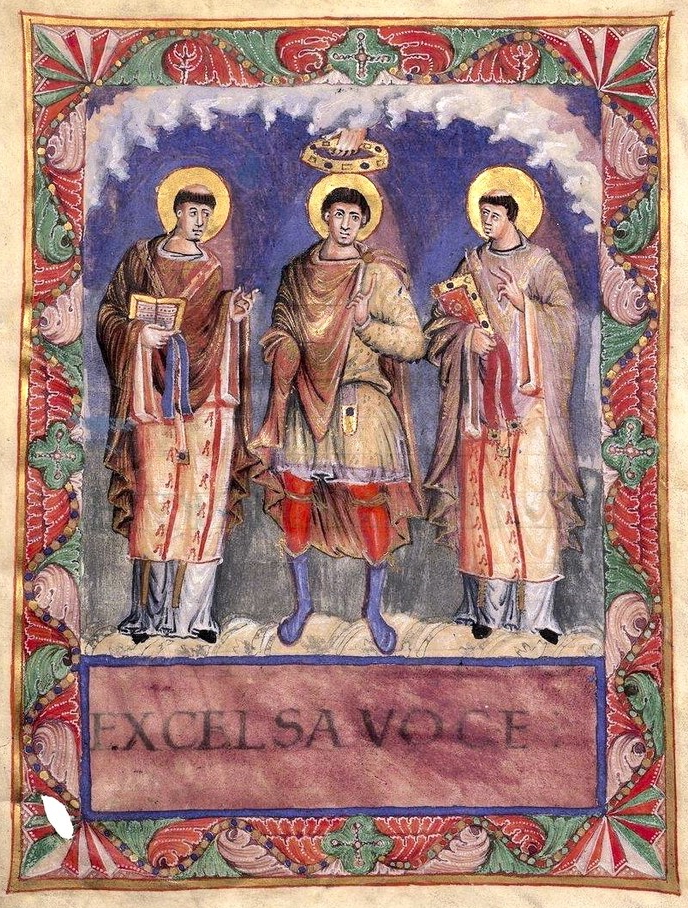

Charles the Bald (grandson

of Charlemagne) - King of France - 843-877. An illustration in the First

or "Vivian' Bible of Charles the Bald, painted ca. 845-851 (the Bible was the

sole surviving manuscript of a Viking raid in 853)

Paris - Bibliothèque Nationale

Charles the Bald with

Popes Gelasisus I and Gregory I – from the sacramentary

of Charles the Bald (ca. 870)

Charles the Bald

enthroned - King of France

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale

THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE ... AND THE PAPACY |

|

The loss ... and then the restoration of the imperial title

The imperial title was passed through future generations of the

Carolingian dynasty ... then placed under challenge by Vikings from the

north and then a mass of dynastic contests, enfeebling the dynasty

greatly. The imperial title got lost, was restored again, then

just passed out of existence as the Carolingians lost their political

positions in most places.

Then the Italian King Berengar came forward to claim the imperial title

finally in 915 ... holding onto that claim until his death in

924. Then the title fell into disuse.

Otto I the Great

In 962 Saxon3 King Otto I – who had succeeded in bringing a number of

German duchies under his rule, who then in 955 decisively defeated

invading Magyars (Hungarians) from the east, and who then in 961

absorbed the Kingdom of Italy – was crowned in Rome as Roman Emperor4 by

Pope John XII.

This Germanic central European (and northern Italian) imperial state –

the "Holy Roman Empire" – would remain intact through many centuries –

in fact all the way up to 1806, when the French Emperor Napoleon

formally put an end to the title and position.

The elective nature of the imperial position

At first the title was hereditary, with a series of Ottos (II and III)

and a cousin Henry inheriting the position and title after Otto

I. But with Henry's death in 1024 the position became elective

among a group of prominent dukes and other noblemen – constituting a

College of Electors. Dynasties would subsequently come and go in

the imperial position ... but because of the ultimately elective nature

of the office the Emperor would seldom enjoy full power.

3The continental Saxony located in the German Southeast ... not the Saxony established in Britain.

4The formal imperial title would become that of "Holy Roman Emperor" by the 1200s.

|

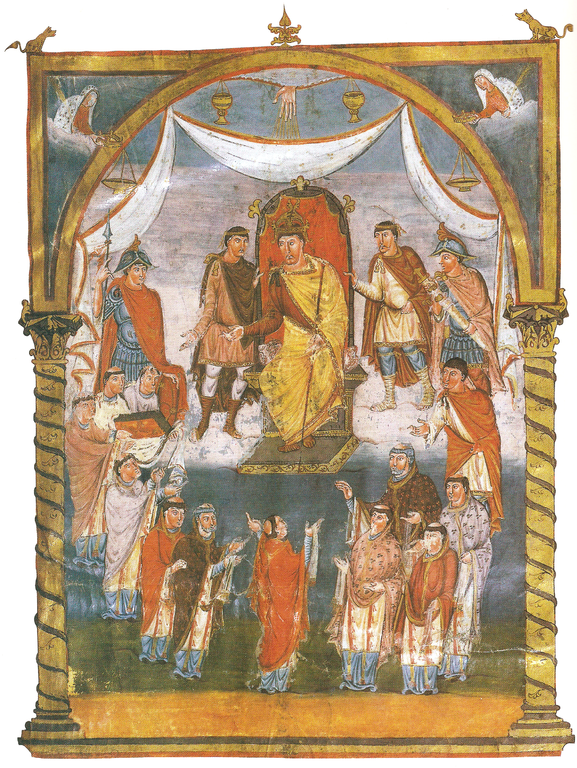

Otto III from the Gospels

of Otto III (reigned 996-1002)

Munich, Bayerische

Staatsbibliothek

|

The Investiture Controversy

At the same time, the rise of emperors, kings and dukes under the new

"imperial" (and feudal) system now posed a new problem for Western

society. The working relationship between the secular rulers

(dukes, kings and emperors) with their military power and the Church

with its absolute religious authority left unanswered the question that

would dog the Western political system for centuries: of the two, who

had the greater authority, the secular or the religious leaders of

Europe?

This question centered particularly on the question of naming local

bishops (the process of investiture), where kings and dukes wanted to

name members of their own families (upper-level church officials were

almost always drawn from the aristocratic class) to the cathedrals

located in their feudal districts ... as well the Popes and archbishops

who felt that this was strictly the Church's prerogative.

Compromise usually worked. But sometimes not. And the

stress on medieval Christendom would become murderous when a deadlock

over the matter occurred.

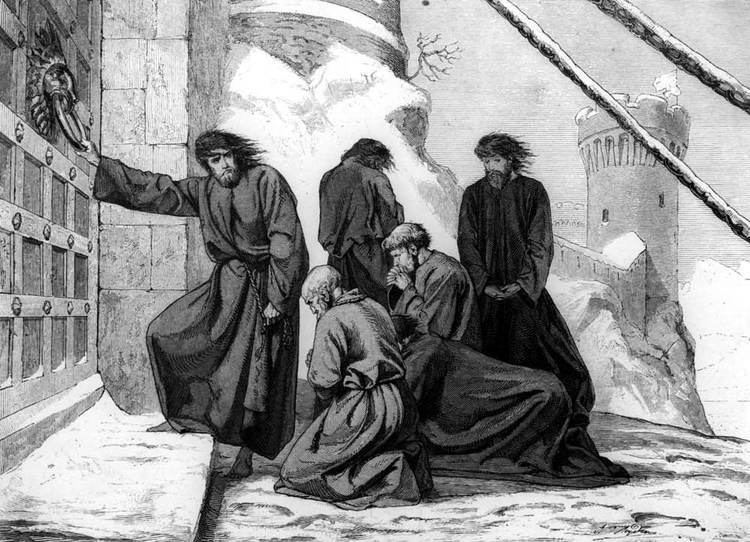

Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII

A

particularly famous blowup occurred between the German King (and

subsequently Holy Roman Emperor) Henry IV and the Roman Church and its

officials, particularly Pope Gregory VII. In 1059, Church

reformers moved swiftly during Henry's infancy to take the appointment

of the Roman bishop (Pope) out of imperial hands and place that

responsibility fully in the hands of a newly created College of

Cardinals made up solely of church officials. Then in 1075, a new

pope, Gregory VII, went even further to declare that the appointment of

the Emperor could be done only by the Pope. But at this point

Henry was an adult ... and fought back and proceeded to appoint his own

bishops ... and even called for the election of a new pope (which Henry

fully expected to control).

Henry's humiliation

Pope Gregory retaliated by excommunicating the emperor. Jealous

German princes were more than happy to see Henry thus humiliated ...

and defeated his army and seized the imperial lands for

themselves. At this point (1077) Henry had no recourse but to

make amends with Gregory ... and went before the pope at the castle of

Canossa in the dead of winter, barefoot and wearing the penitent's

hair-shirt.

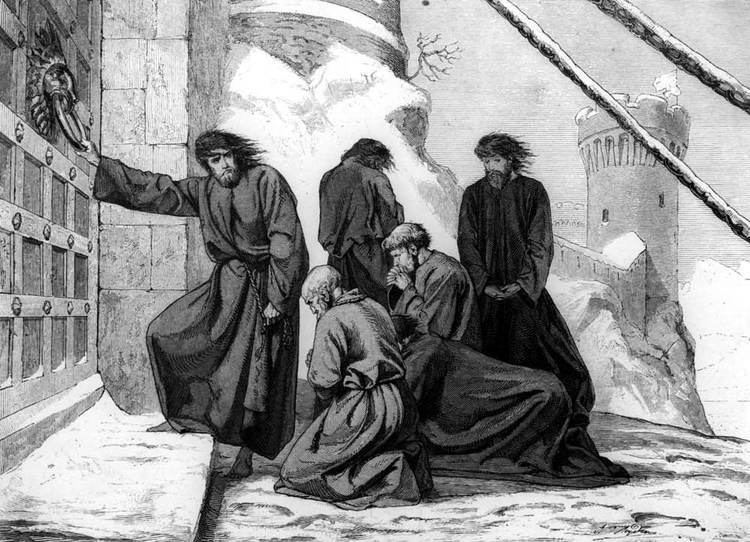

|

Pope Gregory VII

Emperor

Henry IV

Henry at the Gate of Canossa - August von Weyden (1882)

Gregory

ultimately forgave Henry ... but the princes did not. They elected a

rival, Rudolf, to Henry's place as emperor ... and Gregory then also

moved his support to Rudolf and once again excommunicated Henry.

Henry then proclaimed Clement III to be the pope and moved on Rome with

his army ... only to be faced by Normans called out by Gregory to

support him.

But the Normans instead sacked Rome ... causing the Roman citizens to

rise up in revolt against Gregory and his Normans ... who were then

forced to flee. Gregory, however, died soon after. But the controversy

continued.

The Concordat of Worms

Then in 1106 Henry's son, Henry V, supporting the papal party, took

over his father's throne ... but then he too appointed his own

candidate Gregory VIII as pope, starting the whole investiture

controversy up again. However eventually (after much back and forth

struggle between the emperor and various popes and anti-popes), with

the signing of the Concordat of Worms in 1122, Henry V abandoned his

papal candidate and agreed to end the emperor's right of investiture of

church officers.

But this would not end the issue ... for it would spread elsewhere

(England for example) and be a constantly troubling issue involving the

relationship between church and state in Christian Europe.

|

The

sacking, burning (of its immense library) and slaughter in 793 of the

wealthy and famous monastery and its monks at Lindisfarne (coastal

Northeast Britain) was the announcement that a new, crude, and

extremely violent set of players had emerged out onto the European

political stage. The Vikings had finally made their appearance

... and would terrorize Europe for the next several centuries.

Behind this activity were factors similar to the Germanic incursions

into the Roman Empire: land hunger. The population of

Scandinavia had been expanding in a land that is mountainous and cold

... and thus not well suited to bringing new lands under cultivation to

feed a growing population.

In their forays out of the North, they were determined and focused ...

and learned quickly how defenseless the Christians to the South of them

were to unexpected surprise attacks coming from these warriors in their

longboats. These longboats were an amazing piece of naval

technology, one that allowed them to go most anywhere on the high seas,

yet move deeply upriver along any of the European tributaries to those

high seas.

They ventured far and wide, settling Iceland and reaching North

America in the West ... in the East venturing deep into the Slavic

lands of what would eventually (under their domination) become Russia

... and in the South venturing into the Mediterranean and even

establishing Viking or Northmen (simplified to "Norman")

settlements on the strategic island of Sicily.

The Vikings in England

For the next 40 years following the sack of the abbey at Lindisfarne

little would be heard from these Nordic marauders ... until around 835

when Viking raids resumed ... and became a regular feature of English

life.

For the next 40 years following the sack of the abbey at Lindisfarne

little would be heard from these Nordic marauders ... until around 835

when Viking raids resumed ... and became a regular feature of English

life.

By the 860s raids had become complete invasions by Danish Viking armies

accompanied by Danish settlers (the "Great Heathen Army"). One by

one (865-875) the Saxon kingdoms fell before the Danish invaders ...

until Wessex, the western portion of Mercia and the northern portion of

Northumbria remained as the only Saxon kingdoms still intact. In

the middle of what had once been the Saxon heartland, the Danish

established a Viking state operating under Danish custom ... eventually

known as the Danelaw.

Alfred the Great (r. 871-899)

Alfred was the fourth in a line of brothers to come to rule Wessex

("West Saxony") after their father, Aethelwulf died in 858. He

fought alongside his older brother Aethelred against the Vikings in a

series of battles that varied between Saxon victories and Viking

victories. Then when his brother died in 871, Alfred found

himself at age 23 as the new leader of Wessex.

But things got off to a bad start for Alfred ... even though he was

able to get the Danes to leave Wessex ... probably at some great cost

in tribute. For the next five years the situation stabilized

around this arrangement.

Then in 876 the Danes came under an ambitious leader, Guthrum, who

disregarded truces and agreements in the attempt to spread his personal

rule deeper into Saxon England. Alfred fought back fiercely ...

but in January of 878 he barely escaped with a small group of followers

when Guthrum suddenly attacked and slaughtered the inhabitants of a

town where Alfred had been staying for Christmas. At this point Alfred

went into hiding.

In May of that year he emerged to rally again a Saxon army ... and then

at the Battle of Edington was able to deliver the Danes such a blow

that they retreated to a position that Alfred then encircled ... and

slowly pushed the defending Danes to a point of starvation.

Guthrum's Danes surrendered ... and as part of the terms of surrender

had Guthrum and his court baptized.

Eventually (880?) a treaty was agreed on between Alfred and Guthrum,

respecting Alfred's sovereignty over Wessex and the western part of

Mercia with Guthrum acknowledged as ruler of East Anglia and the

eastern portion of Mercia ... the foundation of the Danelaw

.

This did not end the Viking threat ... for not all Vikings were in

agreement with this arrangement – and a number of them crossed to the

European continent to raid and sack towns there. Also independent

Viking bands continued to descend from Denmark to raid the shores of

England ... although they presented themselves more as a bloody

nuisance than as a serious political threat – except for one Danish

attack in Kent (885) which weakened but did not undo Alfred's position

there.

But with Guthrum's death in 889 the Saxon-Dane truce began to

disintegrate as local Danish warlords went to battle to claim

ascendancy in Guthrum's place.

Then in 892 (or 893) a large fleet of Danes crossed from the European

continent to invade Kent ... with the obvious intent of seizing and

settling the land there. As Alfred was confronting this group of

Danes, others arrived at other parts of England, requiring Alfred to

keep his troops constantly on the move ... forcing the Danes back here

and there (the Danes, being mostly raiders rather than settlers, and

thus lacking their own food and supplies, were not prepared for long

encounters).

And thus he busied himself protecting (rather successfully) his domain

... reclaiming even much of what the Vikings had taken from the Saxons

– including the strategic city of the north, York. For this he

was well-beloved by his people ... some who considered him to be

virtually a saint!

Alfred was remembered not only for his fighting skills but also for

building the a small but effective navy, for his hard work at

organizing his Saxon domain into effective political units, structured

by a law code of his own making, and for his efforts to raise the level

of learning within his kingdom (abysmally low given the damage the

Vikings had done to the monasteries which had long served as England's

educational centers). Of particular importance was his effort to

promote such educational improvement in terms of the English language

rather than the usual Latin.

He died in 899, having given Saxon England a relative degree of peace

in the face of the constant Viking threat ... a threat that was still

making life in coastal Europe miserable.

The Vikings in France

Charlemagne's feuding grandsons gave the Danes next door to the north

the opportunity in the 830s and 840s to conduct raids of Frankish

coastal cities (while they were doing the same across the channel in

Saxon England). In 850 a huge Viking raiding party (5,000 men)

under Ragnar sailed all the way up the Seine River to attack the

strategic city of Paris ... sacking and slaughtering in the

process. Only a major plague – and Carolingian King Charles the

Bald's payment of 7000 livres (pounds) of silver and gold, and the

promise of continuing payments after that (eventually termed the

Danegeld) cause the Danes to leave.

Vikings would return again and again ... but encountering much more secure town walls guarding Paris.

Then in 885 the Danes returned with hundreds of ships and tens of

thousands of warriors to attack Paris but even then found the

Parisians, led by Count Odo, able to hold out against this massive

onslaught. Months went by (Vikings venturing from there to sack

and plunder in the region). Only the next summer did the

Carolingian King Charles the Fat arrive ... not to fight the Vikings

but to let them continue upriver to attack the rebellious Burgundians,

and to offer a huge payment in silver. This was hardly a

satisfactory solution to the Parisians ... and when in 888 Charles

died, the stronger Odo was elected King of West Francia – the first

non-Carolingian to take that title.

Also of note was the last Viking leader to vacate the siege of Paris

was Rollo ... who would come to play a huge part in the rise of these

Vikings or "Northmen" (or "Normans") in France.

Rollo

Rollo in 876 had already taken control of the city of Rouen (downriver

from Paris) and the coastal city of Bayeux probably prior to even that

... where he captured, married and had a son, William, by the daughter

of the local Frankish count. He also seems to have had some kind

of working relationship with Guthrum, the Danish king of East Anglia

across the channel. In short, Rollo was busy establishing himself

as something of a local lord in northwestern coastal Francia.

In 911 French king Charles III of West Francia (France) finally came up

with the brilliant idea of negotiating a deal with Viking leader Rollo

after he and his Vikings had burned and sacked Paris (again). He

gave formal recognition by Rollo and his Norman warriors and their

families (after being baptized) of the ducal rule (under the

sovereignty of the king himself, however) of the region at the mouth of

the Seine River (eventually "Normandy"), understanding that with a

vested interest in the peace of the region, Viking military prowess

would be the best way of keeping Paris from being regularly sacked and

burned by future Viking predators. It worked. And

eventually the Norman Vikings were assimilated into French culture.

|

Grip of a Viking processional

cudgel (800s)

Oslo, Universitets

Oldsaksamling

A finely constructed Viking ship

used for the burial of possibly a king

FRENCH NORMANS

BRING SAXON ENGLAND UNDER FEUDALISM |

|

Continuing Viking attacks on England

Viking raids on England never really ceased. But it was not until

947 that they were truly threatening to the Saxon kingdom – for in that

year Erik Bloodaxe was able to take York and add it and the region of

Northumbria to his Norwegian kingdom. But actually this was only

part of the ongoing relationship (peaceful and warlike) that united the

destinies of England and Scandinavia.

Sweyn Forkbeard

Another challenge to Saxon England began to brew in the mid-980s when

Sweyn Forkbeard seized the Danish throne from his father Harald

Bluetooth ... but was driven into exile for the next fourteen years by

his father's allies (including the kings of Sweden and German

Saxony). But by the year 1000 Sweyn rebuilt his power base ...

and then led a series of attacks on England – off and on between the

period 1003 and 1013 – in retaliation for Saxon king Aethelred the

Unready's savage attacks on Danes living in the Danelaw. Sweyn

was so successful that even the Saxons of England were ready to

acknowledge him as the King of England in late 1013.

Cnut the Great takes the English throne

But Sweyn died only a few weeks later in early 1014. At this

point his sons took over, Harald in Denmark and Cnut in England ...

although it took a long struggle against Aethelred's son Edmund

Ironside for Cnut to achieve this position (finally in 1016). In

1017 the Saxon Archbishop of Canterbury officially crowned Cnut as King

of England. To further secure this throne Cnut had most of the

Saxon nobility and the sons of Aethelred executed – but married

Aethelred's widow, Emma ... eventually elevating as royal heir his son

by her, Harthacnut, above his sons by his first (Danish) wife. He

extracted a huge indemnity from the English in order to pay off his

troops – most of whom he then dismissed – but retained a large navy

(presumably to protect his kingdom from other Viking invaders).

He reorganized the lay of his kingdom into a group of four earldoms,

appointing key supporters to each as Earl ... some of these earls

eventually drawn from the ranks of noble Saxons.

When his brother Harald died soon thereafter (1018) Cnut then moved to

take the position as King of Denmark (converting it into another of his

earldoms). But his greatest work was in the way he united the

English Saxons and Vikings of the Danelaw into a single society ...

joined together in a military expedition into the Baltic and then to

Norway, where he took position there as King of Norway (including part

of southern Sweden).

By 1026 Cnut was the ruler of a vast kingdom. And so well established

was he that he dared to take a trip (or pilgrimage) all the way to Rome

in 1027, to attend the coronation of Conrad as Holy Roman Emperor ...

indicating Cnut's own rank among the Christian "greats" of his day.

But aside from the successful challenge to his rule in Norway by

Norwegian nobility Cnut's rule was quite stable until the year of his

death in 1035.

The Norman conquest of England

Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066).

But that stability was not to last long. Upon his death his huge

kingdom was divided up into a number of smaller kingdoms … with his

descendants fighting among themselves for supremacy. Ultimately

in England, actually a Saxon nobleman of the House of Wessex, Edward

"the Confessor" was able peacefully to take the position as England's

new king. However, Edward seemed more interested in piety than in

political power … thus the name "the Confessor." This tended to

weaken greatly the 24-year rule of Edward … to the advantage of local

Saxon lords. This proved to be especially the case for the house

of Godwin … earls of the powerful Wessex domain.

Harold Godwinson – the last Anglo-Saxon king (1066).

Then as death approached, Edward named the well-proven warrior Harold

Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, to be his successor. But the

Norman-French Duke William of Normandy then claimed that earlier, on a

trip to the continent, Harold had sworn fealty to William – in support

of William's claim to the English throne. Supposedly also, the

childless Edward the Confessor had earlier named his cousin William to

be his heir in England.

So then, who had actually the right to the English throne upon Edward's

death? Ultimately, the contest between Harold and William for

this position would prove to be deeply life-changing for English

society.

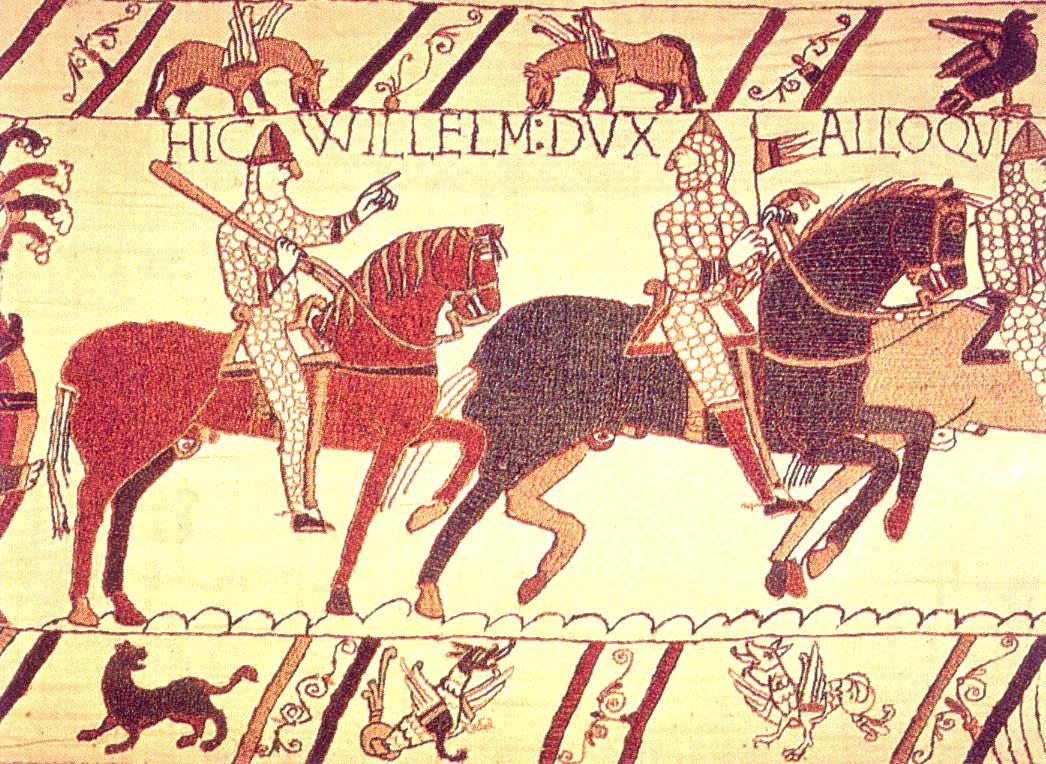

The Battle of Hastings (October 1066).

At the time, Harold was engaged in a fierce conflict with his brother

Tostig … while over in France, William was assembling a huge navy (700

ships), ready to convey a massive army across to England and seize

control (and the throne) there. Furthermore, Pope Alexander

II took the side of William, claiming that he did so because Harold had

broken his earlier oath to William. Hearing this, other English

noblemen also took William's side. Things were not looking good

for Harold.

Then things got much worse in mid-September, when Norwegian king Harald

Hardrada – joined by Harold's brother Tostig – invaded Northumbria and

defeated the English earls there. This forced Harold to have to

move his troops quickly to the north … where the invading troops were

defeated and Hardrada and Tostig were killed (late September).

But at the same time, William of Normandy's huge navy and army arrived

at England’s southern shores in East Sussex. Thus Harald had to

quickly force-march his army 240 miles back to the south. Then on

14 October the two sides went to battle. The Saxon lines held

over the course of most of the day. And then a retreat by the

Normans Harold interpreted as the path to victory … only to find that

his army had just marched into a trap. Harold was then killed …

and the Saxon effort fell apart. It was a huge victory for the

Normans.

The larger outcome.

This, of course, established a Norman-French feudal rule over the

English-speaking Saxon commoners. By doing so, it established a

strict class-based society, with French-speaking Norman families now

ruling over the English-speaking Saxon commoners … and with a class

barrier erected between the two groups that was almost totally

unbridgeable. And it would be lasting.

However also, with this event, Britain was now finally closely linked to continental European affairs.

|

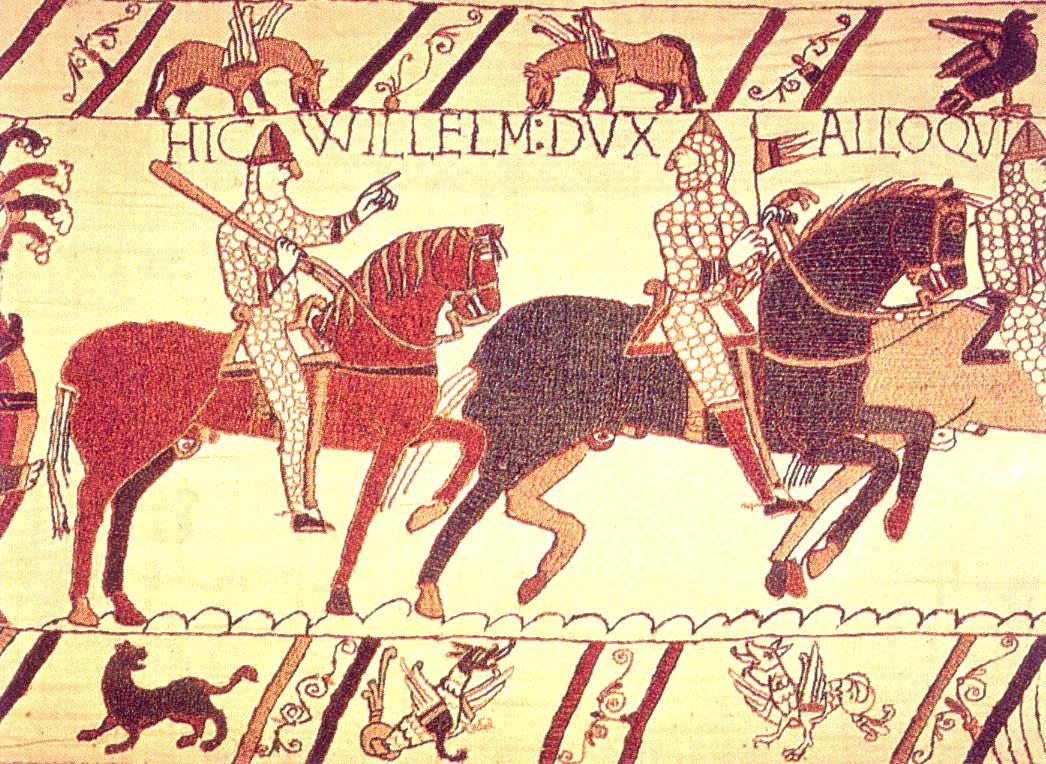

Detail from the Bayeux tapestry

– William, Duke of Normandy, haranguing his troops (1070 - 1080)

Bayeux, Musée de

la Tapisserie

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| |

The Carolingian legacy is carved up –

The Carolingian legacy is carved up – The Holy Roman Empire ... and the

The Holy Roman Empire ... and the French Normans bring Saxon England

French Normans bring Saxon England