A Summary of This Very Extensive Section

Attempts at a post-Napoleonic comeback of Europe's feudal monarchies

Post-Napoleonic monarchies worked hard to put themselves

back in charge of events (1815

Quadruple Alliance) ...

resulting in the "Concert of Europe" designed to keep things

diplomatically under reasonable control among themselves ... and a

cooperative spirit to

restore social order at home

But social reform inspired by Napoleonic France led Louis

XVIII (1814-1824) was kept in

place with a bi-cameral

legislature and freedoms of press and religion.

Metternich dominates the Austrian Empire (1815-1848) in an

effort to preserve imperial

power in a very mixed

ethnic-nationalist empire

Britain becomes rather reactionary under George IV (1820-1830)

... but largely unloved in

Britain

A New Netherlands is formed uniting the Northern Dutch provinces

with the Flemish

provinces under William I (1815-1840)

– to produce something of a buffer state amidst

Britain, France and Germany

Although William

would lose the Flemish provinces with a rebellion of 1830 ... formalized in

1839

Prussia under Friedrich Wilhelm III (1797-1840) plays a much

bigger role in the German world

... although the 39

German states of the Germanic Bund continue under Metternich's

Austrian leadership

Russia continues under Alexander I (1801-1825) – a strange

mix of mystic, reformer, and –

in his later years – reactionary; he creates a "Holy

Alliance" but only Prussia and Austria

join him

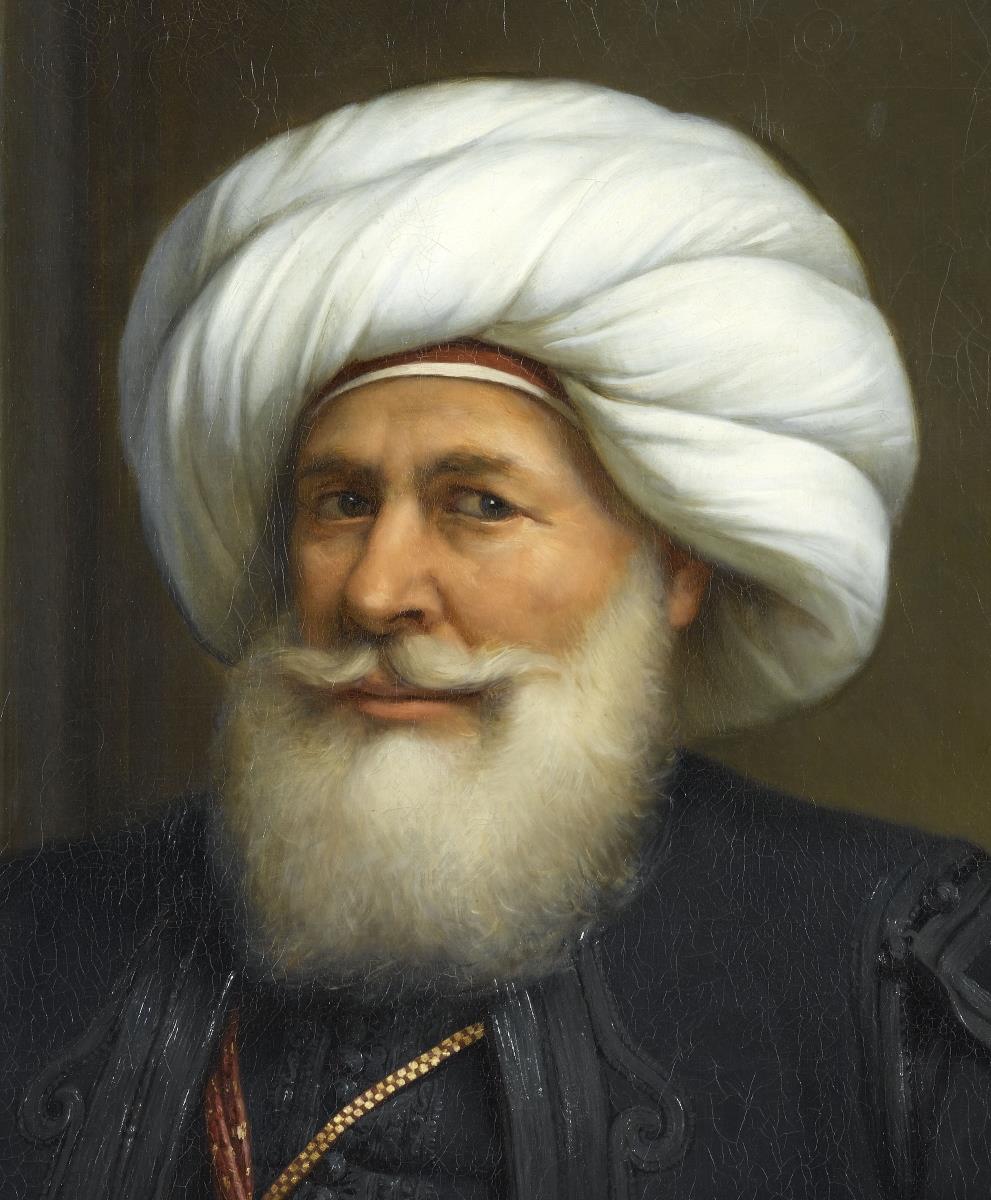

The Ottoman Turks under Mahmud II (1808-1839) find

themselves caught up in harem

politics and corruption of the

Janissary military corps ... the latter finally disbanded by

Mahmud; he institutes the Tanzimat or reorganization of his

government – to modernize

his rule. But

this merely gives more power to his regional governors or pashas

...

especially Egyptian Pasha Muhammad Ali, who works hard to modernize his Egyptian

military

and bureaucracy ... and cotton industry – thus establishing his own dynastic rule

in Egypt

(lasting until 1952)

European ethnic groups under Turkish rule attempt national

independency, the Wallachians

(Romanians) failing, but the Greeks succeeding – the

butchery involved in the Turkish

putdown of the Greeks that other Europeans

become involved in (1827); in 1832 the

Turks recognize Greek independence – under Otto of Bavaria; and

in 1830 the Turks were

forced to recognize Serbian independence – in process (with early

Russian help) since the

Napoleonic Wars

Meanwhile, Germans were trying to bring their many

independent states together into a

single political union or Bund;

but Metternich was able to hold off student demands for

such a union with the

many German princes

signing the Carlsbad Decrees (1819) – very

reactionary to the militant students

Upheaval in Latin America

Meanwhile, France had lost possession of Haiti during

Napoleon's early years (1803 – in

military defeat ... and with sickness

and other more important matters undercutting

French commitment to Haiti)

Spain was quickly losing its colonies in America – revolt

breaking out in "New Spain" in 1810

– with a

Declaration of Independence in 1813 ... although political unity would not come

to "Mexico" until 1821 under

a new monarchy, then a republic in 1824 ... while the idea of

a monarchy

remained strong in Mexico

In 1810 Bolivar leads a rebellion in "Gran

Colombia") against Spanish rule ... escaping to Haiti

– then returning in 1821 to

Venezuela to set up his new republic as its president

Brazil becomes independent only by the move of Portuguese Prince John

VI in 1807 to Brazil

to conduct Portuguese politics from there; Portuguese

politics finally leads in 1822 to

Brazilian independence under Prince Pedro (who dies in 1831)

Spanish lands in Central America declare independence as a

federation in 1823 ... but break

into separate states in

1838 – formally ending the federation in 1841

Such Hispanic independence was well supported by both

Britain (for commercial reasons)

and America (for diplomatic reasons) under the 1823

"Monroe Doctrine"

The Revolutions of 1830

The wisely cautious rule of Louis in France ends when his

reactionary brother Charles takes

control in 1824.

Charles's "July Ordinances"

of 1830 cutting back parliamentary representation sparks the

"July Revolution" in France

Talleyrand and Thiers force

Charles to abdicate ... bringing Louis Philippe of Orleans to

the throne

Louis Philippe poses as the

"people's king;" but French prosperity actually forms his rule

Dutch King William I demands

Dutch to be the royal language (exempting Wallonia) of his

realm – infuriating the French-speaking middle and upper classes of

Flanders

Inspired by French July events,

rebellion breaks out in Brussels in August (1830)

Dutch, Prussia and Russia military come

to William's aid, but France supports the Belgian

decision to secede

And a London Conference recognizes Leopold of Saxe-Coburg as

Belgium's new king

Although Poland had been

"disappeared" in the latter 1700s, Napoleon establishes a Warsaw

Duchy

But the Congress of Vienna

simply places the Duchy (now as a kingdom) under Tsar

Alexander

Tsar Alexander and then (after

1825) his brother Nicholas try to respect Polish integrity

... both however becoming more reactionary with time

Finally the spirit of 1830 hits

the Poles ... but they are not able to fend off the Russian

army and Poland is simply absorbed into Russia ... although Polish

nationalism will

only strengthen over time

Unloved British king George IV

dies and his more liberal brother William IV takes the throne,

reforming Parliament (1832) by getting rid of the "rotten

boroughs" and awarding seats to

citiesas well as increasing the suffrage to include middle class

voters (still only a minority)

And America goes through its

own "democratizing" with Jackson becoming president ... not

changing political realities (America was already fully democratic) but

heightening the

democratic "image"

And a "Second Great

Awakening" stirs new social-political fervor across America

Texas independence (1836) and

its joining the Union (1846) lead Mexico to declare war

on America – a war which the Mexicans lose most horribly... and which stretches

America to the Pacific

The Revolutions of 1848

The rapidly increasing French

industrial working class is furious about its lack of political

rights – and with the help of "Socialist" intellectuals –

begin demanding such rights ...

making King Louis Philippe and his Prime Minister Guizot reactive

A massive banquet in Paris in February

of 1848 brings reformers and military into conflict

But the soldiers refuse to fire on the crowd ... and Louis

Philippe fleas France

The French then declare a new

Republic headed by a provisional government

But the new government gets caught financially in a welfare program it can not

manage

(thousands flock to Paris) – 10,000 becoming killed or wounded under martial law

But a new constitution with

universal male suffrage leads to the election (Dec) of Louis

Napoleon as President

A similar explosion erupts at

Rome, demanding a new Roman Republic to replace the Papal

States

But Louis Napoleon sends an army to support Pope Pius IX (1849) ...

bringing the pope

back – and maintaining a protective presence there ... until conflict

breaks out again

in 1870

In Vienna in March, students

and workers march in protest against Metternich - who fleas to

England

Demands for reform then spread to Prague, Budapest

But the anti-Habsburg revolt

also spreads to Milan, Venice and other Italian city-states in

the north of Italy

The Italian city-states agree

to unite under Charles-Albert, king of Sardinia-Piedmont

But Austrian troops defeat Charles-Albert's army ... who

abdicates to his son

Victor-Emmanuel

Victor-Emmanuel however refuses to submit to Austrian authority

... and supports liberal

democracy

Meanwhile, the Habsburg empire

seemed to be crumbling everywhere

Emperor Ferdinand then (1849) simply abdicates to his

18-year-old son, Franz Joseph

And in Prussia, King Wilhelm IV

submits to the demand for liberal reforms

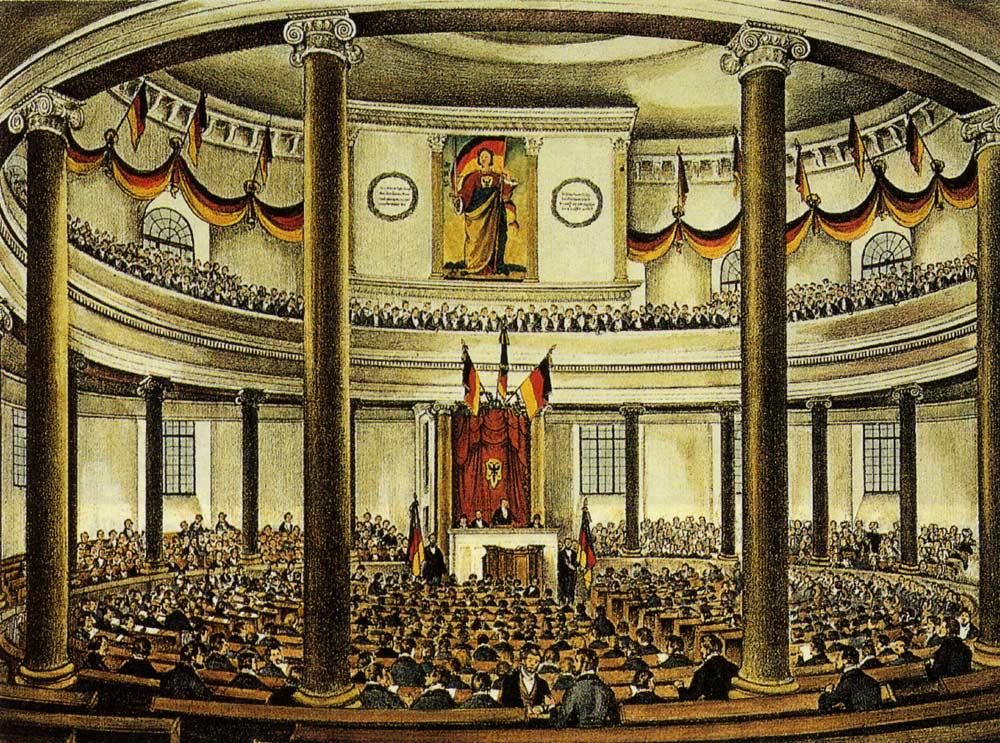

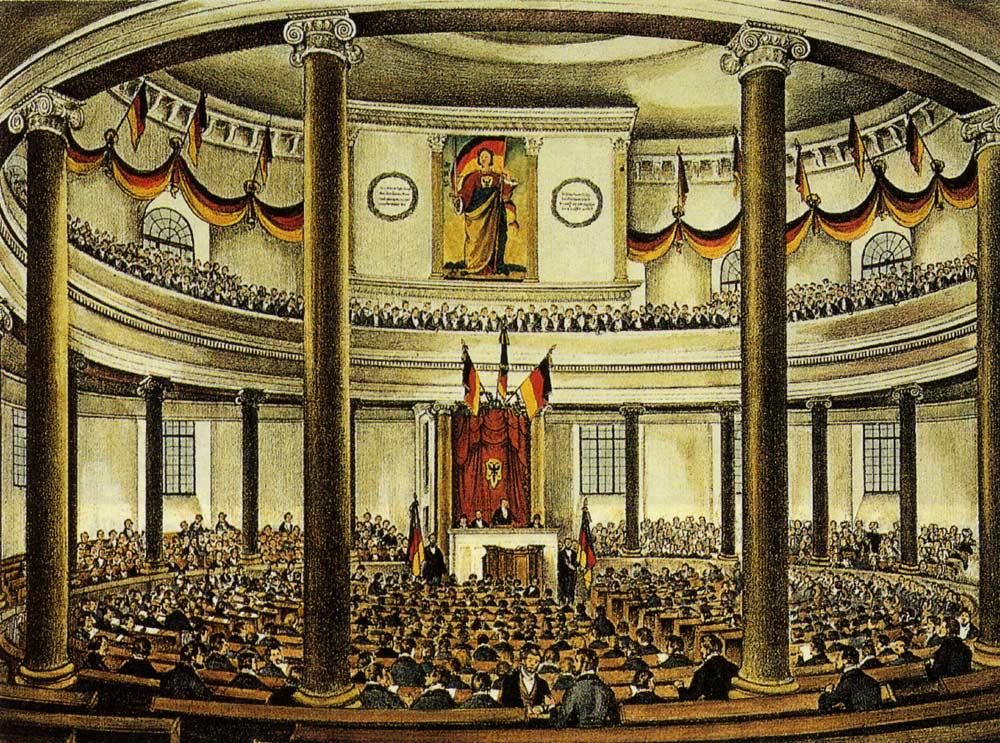

In Frankfurt, delegates to a

constitutional assembly gathered to put a German

Confederation in place

But by 1849 Germany reformers find themselves divided as to whether the Austrian or

Prussian monarchy should head their confederation

The assembly finally decides in favor of Prussia's William IV ... who, however, has

no

interest in such popular government

As the reform effort crumbles, William

sends troops to put down rebellions spreading

across the German states

And the Austrians are able to

retake much of what they so recently lost in Hungary and

Italy

From

the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 to the outbreak of World War One almost

exactly a century later (1914) Europe experienced its first long period

of relative peace in 300 years – since the onset of the Protestant

Reformation in the early 1500s marking the beginning of the break-up of

old Christendom. "Relative peace" is the correct term because

there would be European wars during the 1800s. But they would be

brief and limited in scope compared to the previous European dynastic

wars.

To a great extent this was so because the Europeans focused their

energies more on overseas opportunities for their own imperial

expansion. Also the Napoleonic wars had put such a scare in the

hearts of the European monarchs and aristocrats that they realized the

absolute importance of not letting their rivalries get out of

control. Thus was birthed the "Concert of Europe" – regular

gatherings of European heads of state to work out their differences – a

diplomatic system that guided European continental politics fairly well

during the rest of the 1800s.

It was the foolish disregarding of

this system in the early 20th century that would finally push Europe

into two tragic rounds of a devastating rivalry (World Wars One and

Two) ... which would result ultimately in Europe's fall from its

position as the political center of the world.

THE RESTORATION OF THE MONARCHIES |

|

The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815)

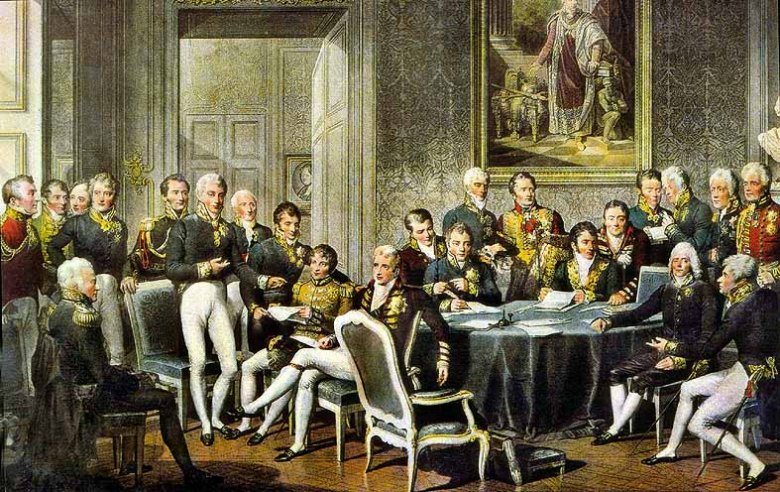

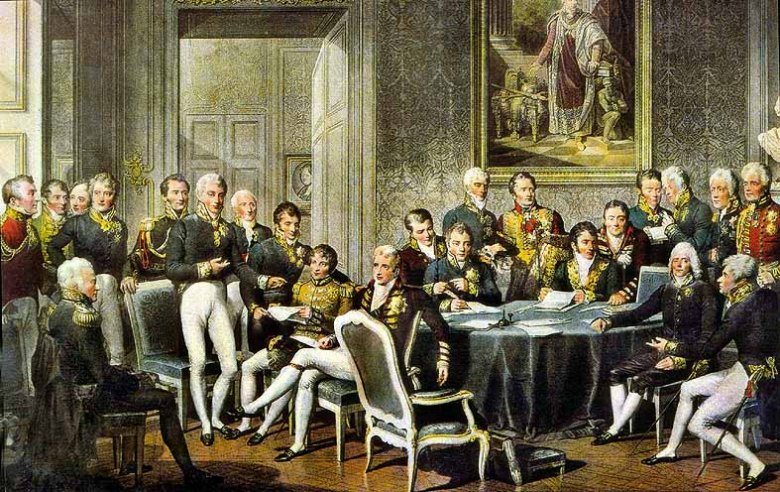

The

Congress of Vienna first assembled with Napoleon's initial defeat in

1814 ... for the purpose of putting Europe back together again in a

form as close as possible to the way it looked before the French

Revolution. Kings, emperors, and diplomatic delegates came from

all over Europe (even Turkey) to participate in this grand event.

The major concerns were what to do with a post-Napoleon France ... and

how to reorganize and distribute among the victorious European powers –

in particular Great Britain, Prussia, Austria and Russia – the various

lands (most notably the Netherlands, Italy, Poland, western Germany,

Norway and Finland) previously shaped by Napoleon's dominating

influence. A balance of power among those four major powers was

their goal. This balance was the best guarantee that their own

squabbles would not get out of hand again. They had no intention

of allowing the lower social orders or classes to get involved ever

again in any future political conflicts arising among Europe's

royalty. Thus they signed a Quadruple Alliance (1815) promising

to meet regularly (the Concert of Europe) over a period of at least

twenty years to consult on any matter affecting their relationship.1

1France would join the alliance in 1818.

The Congress of Vienna - by Jean-Baptiste Isabey

|

France

But treaties among Europe's kings and emperors would not take care of

issues brewing within each of the countries. France in particular

would have a very difficult time with lingering domestic social forces

unleashed by the Revolution.

The Bourbon dynasty was restored to

the French throne, with Louis XVIII, brother of Louis XVI, now King of

France.2 The 60-year old, gout-inflicted Louis XVIII had come to the throne after watching the butchering of the

French royalty and much of the French aristocracy during the Revolution

– and watching the success of Napoleon at the head of a popular ("the

peoples") French army. He was wise enough to draw some important

conclusions for his own tenure in office: the days of royal rule,

conducted without concern for the people, were over. Consequently, Louis issued a

very Liberal Charter of 1814, guaranteeing a bi-cameral legislature to

govern with him ... and freedom of the press and religion. He

retained most of the governmental reforms put in place by

Napoleon. He also promised the rising middle class or bourgeoisie

that he would abolish a number of key taxes. (But he would not,

could not, keep such a promise. His treasury was empty). Thus it was, nonetheless, that his reign proved to be a time of greatly appreciated peace.

2Ten year-old Louis XVII, son of Louis XVI, died in a Republican prison in 1795.

French King Louis XVIII (reigned 1814-1824)

|

Austria

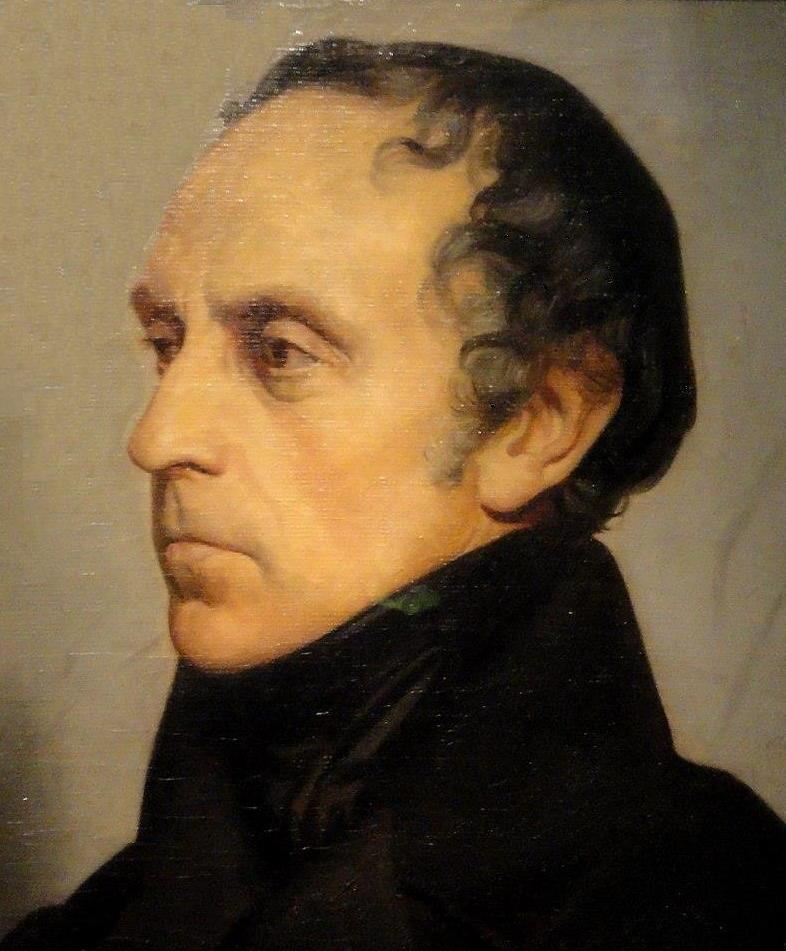

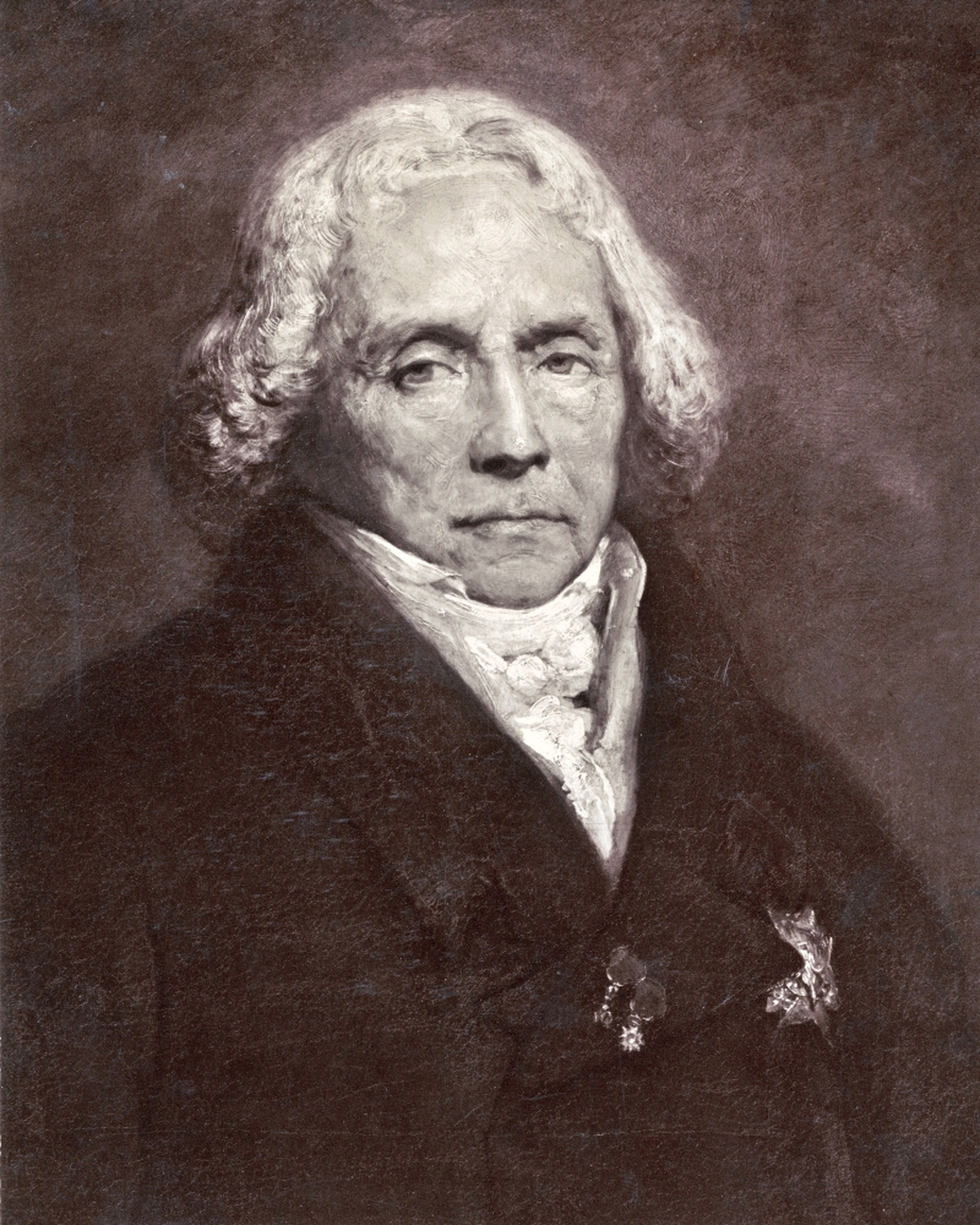

Not only was the post-Napoleonic gathering held in the Austrian

capital, Vienna, but much of its work in redrawing the post-Napoleonic

map of Europe was engineered by the Austrian Foreign Minister,

Metternich. It might even be said that the European diplomatic

era following the defeat of Napoleon was something of the "Age of

Metternich" (1815-1848).

Napoleon's politics had finished off the ancient position and title of

Holy Roman Emperor. But Austria's ruler, Francis, took for himself

the title of Francis I, Emperor of Austria. Austria was however just about

as complex a political entity as the Holy Roman Empire had been.

The Austrian Empire was German at its core, but spread widely so as to

incorporate many other ethnic or national groupings, including

Hungarians, Poles, Italians and Czechs. With the

Napoleon-inspired rise among the various ethnic groups of Europe of a

distinctly popular or "nationalist" spirit, directing Austrian politics

on a stable course was going to be extremely difficult for Austria's

Habsburg Emperor and his Foreign Minister (and, after 1821,

Chancellor) Metternich.

|

Francis I – Emperor of Austria (1804-1835)

(formerly Francis II - Holy Roman Emperor – 1792-1806)

by Joseph Kreutzinger (c. 1815)

Universalmuseum Joanneum - Graz, Austria

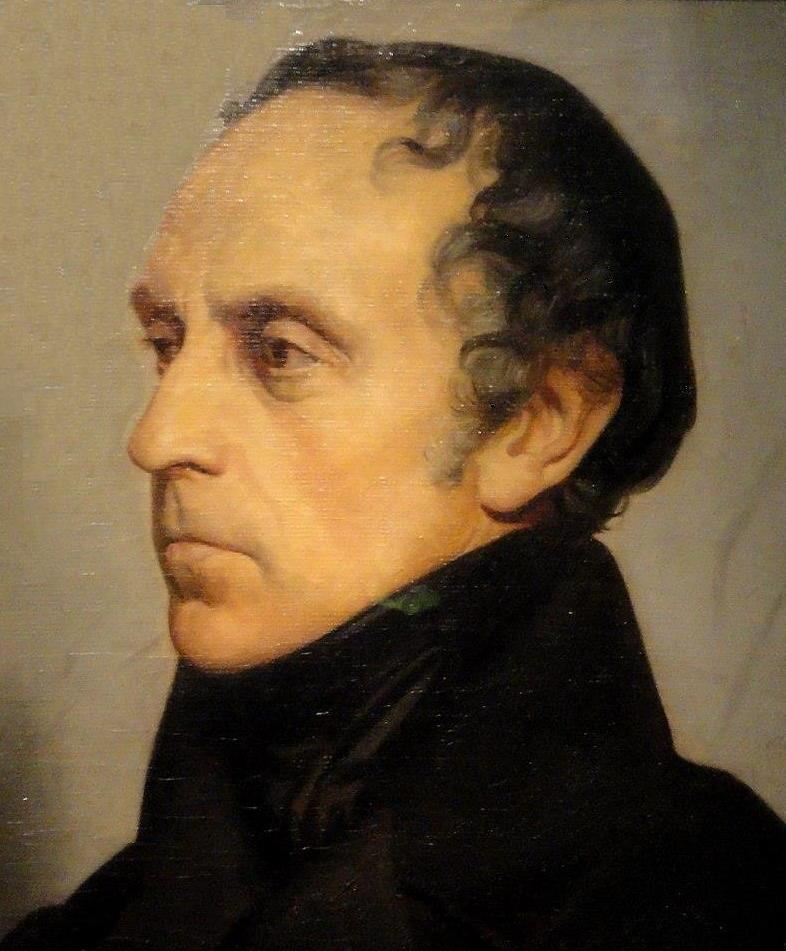

Prince Klemens von Metternich

Foreign Minister and Chancellor of the Austrian Empire (1809-1848)

|

Great Britain

Since 1810, when the British King George III had fallen rather

permanently into a state of insanity, Britain had been led by George's

son George as Prince Regent, and by a number of capable cabinet

ministers, including notably Jenkinson (Lord Liverpool), Castlereagh,

Wellington, Canning. When George finally died in 1820 his son

took the throne as George IV ... and British politics took a decidedly

more reactionary turn (1820-1830). The main issues impacting his

short reign were the Catholic Question – George IV being strongly

opposed to any loosening of the restrictions against Catholics in

office – and his scandalous efforts to divorce his wife. On both

matters he failed to get his way, diminishing his stature considerably.

Towards the end of his reign he became reclusive, being massively

overweight and nearly totally blind. When he died in 1830, there

was no sadness or regret among his people.

|

King George IV (regent 1810-1820; king 1820-1830)

Unflattering cartoon of gouty George IV ... with pictures of himself behind him

|

The Netherlands

Napoleon had replaced the Batavian Republic, established during the

French Revolution, with the Kingdom of Holland – placing his brother

Louis Bonaparte as its king. With Napoleon's downfall, William

Frederick of Orange, son of the last stadtholder, declared himself King

of the Netherlands. Then during the Congress of Vienna, the

Catholic southern provinces – that had been exchanged back and forth

among Spain, France and Austria – were combined with the northern

provinces to create a new United Netherlands ... William Frederick as

its King William I.

The logic behind the major powers creating this stronger entity was to

put some kind of barrier state or neutral territory separating Great

Britain, France and Germany from each other.

|

King William I of the Netherlands (ruled 1815-1840)

|

Prussia

Prussia continued after the war to be ruled (1797-1840) by Friedrich

Wilhelm III. He was not a particularly outstanding king, relying

on his ministers to bring Prussia her diplomatic and military

successes.3 His one burning desire personally seemed to be to

impose a rigid Protestant regime over his lands, forcing the unity of

the Lutherans and Calvinists as a single Prussian Protestant Church

(1817) ... over which he personally presided.

The Deutscher Bund (Germanic Confederation)

The 39 German states of the old Holy Roman Empire (including Prussia)

were loosely united (1815) as a Germanic Bund or union. The Bund

had its own legislature (the Diet) ... but was under the presidency of

Austria ... and thus, to the extent it had any real power at all (which

indeed was slight), was shaped by the conservative or reactionary

policies of Metternich.

3The

one diplomatic success most urgently sought by the Prussians in Vienna

was the acquisition of Saxony. But Austria and Great Britain,

seeing danger in such a growth of Prussia, blocked this move.

Ultimately the Prussians had to give up the quest.

Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia (ruled 1797-1840)

|

Russia

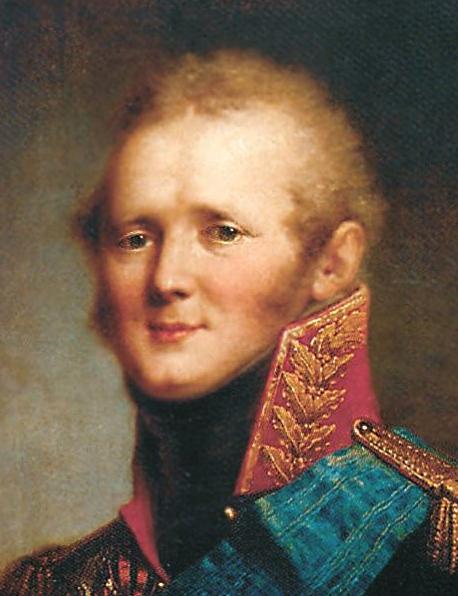

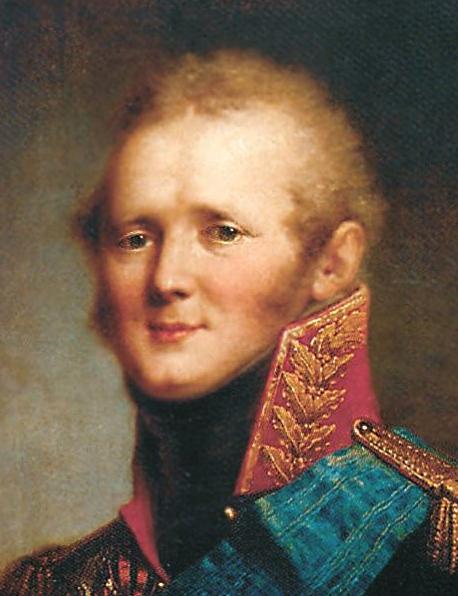

Russia continued under the rule (1801-1825) of Alexander I ... a

strange personal mix of mystic, plus sometimes liberal (the earlier

part of his reign), sometimes reactionary (the latter part of his

reign), in personality.

When he came to the Russian throne in 1801, he announced himself

as a liberal reformer ... though he was slow to act on these reforms,

and did not get far before he proved himself to be a rather traditional

autocrat. In fact by the end of his reign he had become quite a

reactionary. It was rumored that he had come under Metternich’s

powerful influence, although Napoleon’s earlier betrayal as an ally

with his attack on Russia, plus popular uprisings Alexander did not

understand or sympathize with (such as the Greek anti-Ottoman revolt)

and growing discontent among young Russian officers, unhappy over the

backwardness of Russia, played their own part in Alexander’s retreat

from liberalism.

He was the one who dreamed up the idea of

a "Holy Alliance" to which he invited all the participants at the

Congress of Vienna to join ... largely as a defensive alliance against

the kind of political culture unleashed by the French Revolution and

Napoleon. Ultimately only Austria and Prussia humored him by

joining his Alliance. France and England had no interest in

getting entangled in Alexander's religious crusade – though they did

participate in the Quadruple / Quintuple Alliances, with something of a

parallel political agenda.

|

Alexander I Emperor (Tsar) of Russia (ruled 1801-1825)

|

The Ottoman Turks

From the high point of their assault (but ultimate defeat) at Vienna in

1683, the Turkish Ottoman Empire had been on a steady path of decline –

militarily, politically, socially and morally. The quality of the

Ottoman sultans had deteriorated steadily, personal weakness and even

insanity increasingly affecting the character of the sultanate.

The Imperial Harem of Valide Sultans (mothers of the sultans) gained

dominance over the process of selecting sultans (usually minors when

sultans first took their thrones) and then the Haseki Sultans or wives

of the sultans took over the positions of dominance after that.

Consequently the objective of Ottoman rule ceased to be the welfare of

the Ottoman Empire, but instead became the advancement of the fortunes

of one or another of the harem families (run by women slaves) in

competition with each other.

Also the Janissary military corps had become highly privileged,

wealthy, corrupt ... and largely useless as a military

institution. Sultans had been made and unmade (murdered usually)

by various Janissary groups ... weakening even further the Ottoman

Empire.4

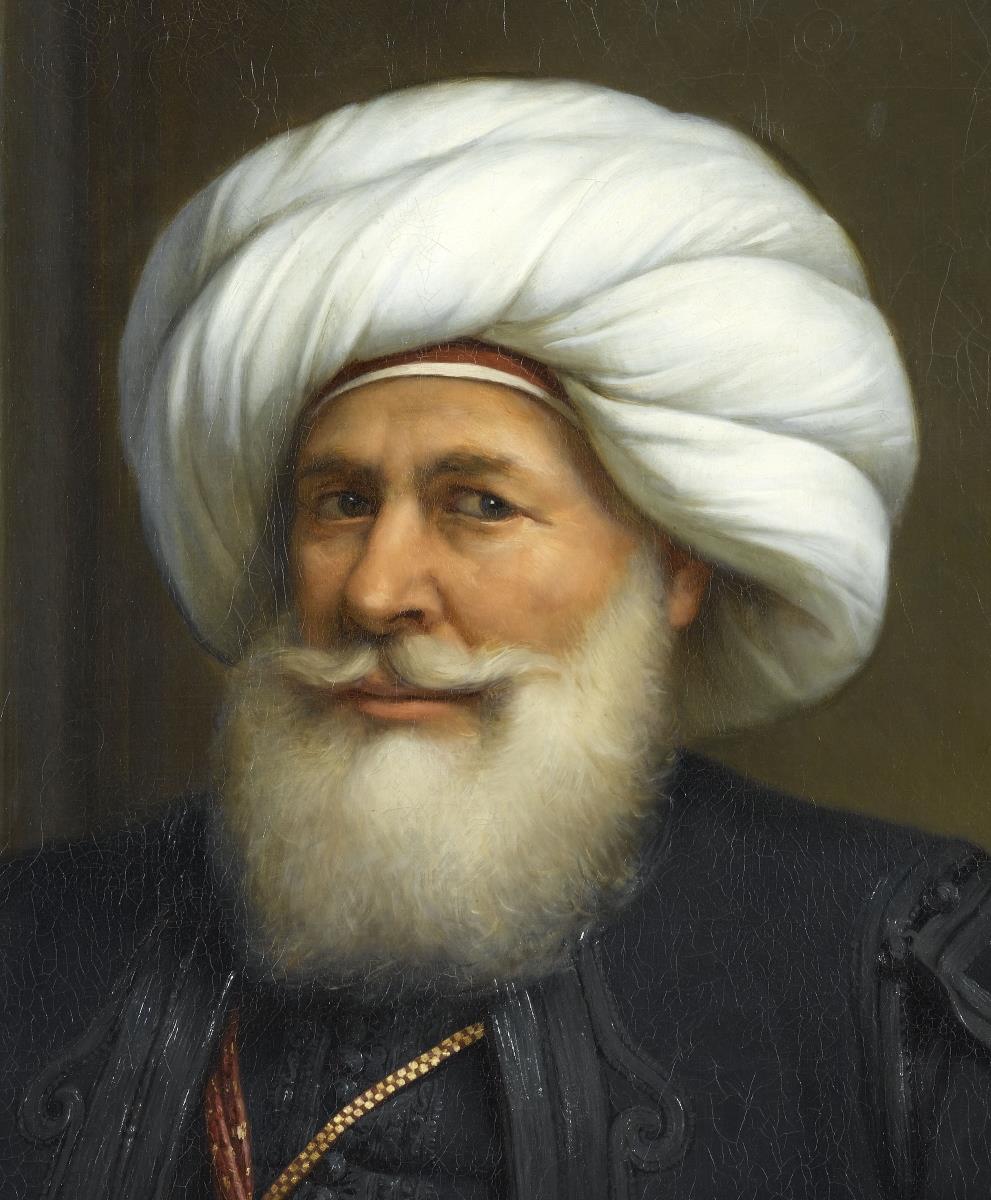

Sensing the need for deep reform, in 1826 Sultan Mahmud II (ruled 1808-1839) made the

decision to disband the Janissaries ... facing a bloody revolt from the

Janissaries in the effort. But he did succeed ... and began the

process of rebuilding Ottoman power based on a more modern army (but a

very slow process at this point).

Sensing the need for deep reform, in 1826 Sultan Mahmud II (ruled 1808-1839) made the

decision to disband the Janissaries ... facing a bloody revolt from the

Janissaries in the effort. But he did succeed ... and began the

process of rebuilding Ottoman power based on a more modern army (but a

very slow process at this point).

Then there was the matter of the pashas, Ottoman noblemen who were

given increasing responsibility in the governance of the provinces and

the Ottoman military. As the sultan's effective governance over the

empire weakened, his responsibilities were gradually taken up by a

number of the pashas, thus constituting themselves and the regions of

their governance as increasingly semi-autonomous realms within the

empire.

Quite notable in this regard was Muhammad Ali Pasha,

governor of Egypt (1805-1848). This Albanian-born Muslim reformer –

who in 1811 slaughtered off several thousand of the Mamluks who had

long governed Egypt – worked hard to bring up to European standards the

army and bureaucracy of Egypt (Napoleon’s activities in Egypt having

been the keen motivation for doing so). He also helped develop an

industrial economy able to support such an army. Soon, with the

introduction of cotton farming into Egypt, the country began to develop

independent economic and political power. Quite notable in this regard was Muhammad Ali Pasha,

governor of Egypt (1805-1848). This Albanian-born Muslim reformer –

who in 1811 slaughtered off several thousand of the Mamluks who had

long governed Egypt – worked hard to bring up to European standards the

army and bureaucracy of Egypt (Napoleon’s activities in Egypt having

been the keen motivation for doing so). He also helped develop an

industrial economy able to support such an army. Soon, with the

introduction of cotton farming into Egypt, the country began to develop

independent economic and political power.

In the process, Muhammad Ali established his own dynastic rule in Egypt

(which would last until 1952) ... creating the question of just exactly

how much was Egypt still a part of the Ottoman Empire. The British by

and large worked with his successors (now entitled "Khedives") as if

they were in fact fully sovereign heads of state, able to conduct

political policy in Egypt without consulting with the Ottoman sultan.

The Tanzimat. Meanwhile,

Sultan Mahmud II was keenly aware of the deficiencies of the Ottoman

government, and authorized a vast number of reforms of Ottoman

government and society in an attempt to modernize or reorganize

(tanzimat) the empire.5 French government provided the model for most of the reforms.

Yet whereas the hope of the sultans was to integrate more closely all

the various Ottoman sub-communities with the sultan's rule, the reforms

had something of the opposite effect, opening up to these

sub-communities the idea that they had their own sovereign rights to

develop as distinct peoples.

Thus a greatly weakened Turkey was beset by revolts of subject peoples

from within the Empire ... and assaults from without by surrounding

powers (principally Russia and Austria), attacks which steadily chipped

away at the outer borders of the Ottoman Empire.

Greece (1821-1832)

Then in 1821 it was the turn of the Wallachians (Romanians) to attempt a similar revolt. But it was put down by the Turks.

But the Wallachian uprising had inspired the Greeks of the

Peloponnesian Peninsula also to revolt at that same time. This

revolt, however, soon spread to the Greeks of Macedonia and the Island

of Crete.

Greek atrocities against Turks were answered by even greater atrocities

against the Greeks by the Turks (the Greek Patriarch hanged outside his

residence in Constantinople ... and 27,000 Greeks executed on the

island of Chios). This then prompted European involvement.6

Sultan

Mahmud then enlisted Muhammad Ali to send his army to Greece to crush

the rebellion. Muhammad Ali largely succeeded in this task (1825) ...

prompting Britain, France and Russia to intervene. In 1827 the three

powers finally sent their navies to break the Turkish-Egyptian hold on

Greece. This gave the small and struggling Greek Republic some relief.

But Mahmud would not back down ... until the Russian army took the key

town of Adrianople just north of the Ottoman capital at Istanbul ...

and a French expeditionary force was sent at the same time to the

Peloponnese (Southern Greece).

Bit by bit, protocols were signed by the Turks recognizing various

aspects of Greek independence ... until full independence was formally

acknowledged in the Treaty of Constantinople in 1832. The treaty also

established a monarchy for Greece, with Otto of Bavaria (actually a

minor at the time, and thus putting Greece under a regency until 1837)

becoming Greece's first king, replacing a short-lived Greek Republic.

His rule would face some difficulties in that Otto was a strong German

in his tendency to demand strict adherence to government rulings –

putting him in conflict with some of the more active former

revolutionary fighters – and was a strong Catholic in a very Greek

Orthodox world. But he did get Greece's independence secured for its

people ... although the Greeks could not get past the idea of

continuing the revolution until all Greek lands were out from under

Turkish rule, and the country had its capital back in Constantinople

(Turkish Istanbul). Troubles developed between the King and his very

popular former admiral Konstantinos Kanaris, with the blowup resulting

finally in Otto being forced to leave Greece in 1862.

Upon the urging of the major Western powers, the Greeks accepted Danish

prince George, who converted to Greek Orthodoxy and worked carefully to

win the support of the Greek people. He would reign as a very popular

king ... until his assassination by a crazed Socialist in 1913.

Serbia. Revolt

against the Turks had actually started earlier in Orthodox Christian

Serbia when in 1804 a peasant uprising, assisted by Christian Orthodox

Russia, was able to hold off efforts of the Turks to force Serbia

militarily back into the Ottoman fold. But in 1812, Russia was

being pressed deeply by Napoleon's army – thus pulled out of the game,

leaving the Serbs to face the Turks alone. For several years

Serbia was made to submit ... then in 1815 revolted again, this time

successful in holding off the Turks.

Finally in 1830 the Turks were forced to recognize Serbia officially as

an autonomous state, with the Serbian rebel leader Miloš Obrenović as

the new Serbian prince. ... ruling under a new constitution as of 1835.

4The

Janissaries had once (the 1400s and 1500s) been an elite fighting force

made up of slaves taken from their Christian homes as boys and raised

in both Islam and in a spirit of total devotion to the sultan.

They had no other stake in life and thus fought fiercely for the

sultan. But eventually (the late 1500s) the Janissaries were

allowed to marry, own property and have children of their own, becoming

something of an Ottoman aristocracy. They now had political

interests of their own to pursue ... and they soon became centers of

corruption rather than military discipline. The Janissaries grew

so powerful that they were able to make and depose sultans at will,

weakening greatly the sultanate.

5And

also did his sons, Abdül Mecid I (ruled 1839-1861) and Abdül Aziz

(ruled 1861-1876), who tried to keep their father's reforms moving

ahead.

6It

also inspired the British Romantic poet Lord Byron to go to Greece to

fight for its independence ... and die there of a fever in 1824!

THE GROWING SPIRIT OF REBELLION |

|

Germany

University students around Germany found themselves hopeful that a

united Germany might be established at the Congress of Vienna ... but

were disappointed at how Germany was ultimately split into three parts:

a strong Austria, strong Prussia and a weak Bund or German

Confederation. A number of student organizations (the

Burschenschaften) – calling for the creation of just such a unified

German fatherland – spread rapidly ... much to the distress of

Metternich. He called a congress of German princes to stand

together against this growing movement. They jointly issued the

Carlsbad Decrees, agreeing to curb the freedoms of the press and of the

universities ... even outlaw the use of the Burschenschaften's colors:

red, black and gold (the colors of Germany's flag today!). But

all that this achieved was the driving of the student movement underground

... which then became increasingly revolutionary. |

The march of the Burschenschaften to the Wartburg - 1817

... calling for a unified Germany

|

Spain

A similar problem developed quickly in Spain after the war.

Ferdinand VII had been removed from power by Napoleon in 1808 but

returned to his throne by Napoleon in 1813. At this point

Ferdinand turned into a bitter reactionary ... and what is considered

today Spain's worse king in its long history. He quickly

alienated the Spanish people by rejecting the liberal constitution of

1812 ... and then re-instituted the Inquisition, shut down all

newspapers except the official journal, and imprisoned or executed

every liberal voice in the country. And he seemed unable to work

with any other Spanish political figure, changing – and even arresting

– his ministers at frequent intervals.

Spanish

revolt actually started up first in the Spanish colonies in America

during the Napoleonic Era. Initially these revolts were

anti-French ... though liberal in political character. But with

the restoration of Ferdinand as Spanish king, the spirit of rebellious

liberalism began to turn against Ferdinand ... and take on the

character of independence movements aimed at securing the colonies'

freedom from Spanish authority. Then the spirit of revolt

extended to Spain itself in early 1820 among Ferdinand's troops that he

had assembled in Cadiz with the intention of sending to America to

suppress the colonial rebellions going on there. Ferdinand lost

the contest with his troops and was thus forced to accept the liberal

constitution of 1812.

But another meeting of the Concert of Europe was called by Metternich,

where it was finally decided to authorize the French to invade Spain

(1823) and restore the absolute rule of Ferdinand. In this France

succeeded, ending for a while all open talk of liberal reform of Spain.

The continuing independence movement in the Americas

Haiti. The French

Revolution and its strong political ideals infected deeply the

inhabitants of the French sugar-producing colony (known at the time as

Saint-Dominique) ... inhabitants made up mostly of slaves brought

generations earlier from Africa to work those extremely profitable

sugar plantations.

Unfulfilled promises of freedom sent back and forth between

revolutionary France and Haiti finally inspired a group of mostly Black

freedmen in 1791 to take up their own cause of liberation (ending

slavery altogether) ... beginning a revolt that would brew through the

next ten years – led by the militarily talented Toussaint

Louverture. Indeed, slavery was pronounced at an end in 1794,

confirmed by the subsequent Directorate, and then also by

Napoleon. But the actual status of the colony itself remained

uncertain ... especially as Louverture switched back and forth in his

loyalties to France (partly shaped by political intrigues going on

within Haiti itself).

Napoleon moved in 1801 to resolve the matter by sending a huge force to

Haiti to bring the colony back under full French control ... and by

having Louverture and his colleagues arrested and deported to France in

the process. But the Haitians fought on, led by Louverture's

lieutenant Jean-Jacques Dessalines ... the Haitian effort aided greatly

by a huge outbreak of yellow-fever, which decimated the French

army. When in 1803 the French were defeated in a battle at the

end of the year, it was clear that French rule in Haiti had come to an

end.

Indeed, Haiti now came under the firm rule of Dessalines, who butchered

the remaining French White and most of the freed-Black population in

Haiti (a total of 3,000 to 5,000 executed), and then became Haiti's new

emperor. But he himself was assassinated in 1806! Thus it

was that Haiti set off down its own quite peculiar path ... one often

very brutal in nature.

Mexico. When

Napoleon invaded Spain in 1808, deposed the Spanish king Charles IV and

placed his own brother Joseph over Spain as its new king, the Spanish

colonies in America found themselves in a state of political

confusion. At first it appeared that the huge viceroyalty of New

Spain (as the Spanish colony was termed at the time) was going to come

under the independent governance of a group or junta of local leaders

... except that this was blocked by those (usually those originally

born in Spain) with continuing Spanish loyalties.

But then a call to revolt issued in 1810 by a local priest, Father

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, was taken up enthusiastically by locals ...

and a contest between the pro-Spain and pro-independence supporters

broke out ... brutally – both sides executing captured opponents,

including Father Hidalgo, who was executed in 1811. A Declaration

of Independence was issued formally in 1813 ... but the civil strife

within New Spain continued nonetheless.

In 1820, when Spanish Liberals were able to take control in Spain, the

question of the status of the Catholic Church and the matter of a

republic or a monarchy to govern Spain and its overseas holdings merely

intensified the struggle in New Spain. Finally in 1821, a

compromise was agreed on in New Spain (now giving itself a local name

as "Mexico") between the leaders of the two parties – declaring Mexico

independent and all citizens now of equal status politically ... but

Catholicism still the sole religious underpinning of the country and

monarchy as the ongoing form of government. The monarchy was,

however, very soon replaced by a republic of sorts.

So Mexico was independent. But what it was beyond that was never

very clear. The military stepped in frequently to resolve

personal contests at the top of the political hierarchy – making for

very unstable governance ... a problem that seemed never to go

away!

Central America. At

the same time the Spanish lands to the south of Mexico, set themselves

up separately from Mexico as the Federal Republic of Central America

(1823). But the different regions making up the federation fell

into civil war in 1838 – liberals versus traditionalists, eventually

joined by just "separatists" in the fight. But by 1841, everyone

was exhausted ... and the federation was ended – with Guatemala,

Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Costa Rica acknowledged as fully

independent countries.

Simón Bolívar and his Republic of Colombia (Gran Colombia).

Much the same dynamic was going on further south, in Spanish

territories located in the northern part of the South American

continent. Again ... the French Revolution and Napoleon's role in

upsetting deeply Spanish government both home and abroad played majorly

in the developments in this region. But here a single individual,

Simón Bolívar, played the key role of being the central figure in these

events.

In 1810 Bolívar took up fighting in support of a Venezuelan republic

that had declared its independence from Napoleonic Spain. At one

point (1815) he was forced to flee to Haiti, but returned with Haitian

support and was eventually (1821) able to set up a new Venezuela

republic ... actually entitled the Republic of Colombia – with Bolívar

quite naturally serving as its president. But he did not stop at

that, but kept up his conquests by liberating other lands in the region

– Ecuador (1822), Peru (1824) and Bolivia (1825). These were then

merged into what was termed "Gran Colombia."

However political differences developed between Bolívar (a strong

centralist) and former supporters who wanted greater autonomy in the

regions ... ultimately even independence on the part of Venezuela,

Colombia, Ecuador, etc., that made up Gran Colombia. In the

dispute, he lost control of those regions, was nearly assassinated

(1828), and – tired of the whole mess – finally resigned (1830) ... and

soon died.

But here too what followed was simply government by various

military-supported autocrats (caudillos) ... who, however, would never

attain the respect and authority that Bolívar had possessed. But

it was all the government that these new states were to know ... for

the longest time (even up to today).

Brazil. As a

colony, Brazil played a role quite different from that of the Spanish

colonies when in 1807, to escape Napoleon's aggressions, the Portuguese

Prince Regent João (or John) VI moved himself and his court to Brazil's

Rio de Janeiro ... making Brazil the center of Portuguese

operations. And in doing so, João went on to develop Brazil's

political institutions to a rather high degree of sophistication.

And then, to the great irritation of the Portuguese back home in

Portugal, when the Napoleonic threat was over in 1815, there seemed to

be little interest in the royal court in leaving the vast lands of

Brazil to retake residence in the much smaller Portugal. The idea

of making Brazil and Portugal co-equals in the Portuguese political

system did not please the domestic Portuguese either.

But the Liberal Revolution in Portugal (1820) brought to power those

able to force João to return to Portugal to resume rule there

(1821). Nonetheless, he left his son Pedro to continue as Regent

in Brazil. Then also, when the Portuguese revolutionaries tried

to return Brazil to the status of being a mere Portuguese colony ...

the Brazilians resisted strongly – led by Pedro. The following

year (1822) the Brazilians then made their country a fully independent

"Empire" ... with Pedro as their emperor. But Portuguese military

efforts to counter this move did not work well ... and the Portuguese

court finally (1826) recognized Brazil as being fully independent.

Of course independent Brazil faced some of the same contentious issues

as the newly independent Hispanic states around them: liberalism

versus traditionalism. Keeping Brazil from falling into civil war

exhausted Pedro, who died in 1831 ... leaving Brazil in the hands of a

Regency while his son remained in his infancy. Unsurprisingly,

the political turmoil merely continued during this period.

Finally in 1841, Pedro II was crowned ... way before his adult years.

But overall, Brazil prospered and remained fairly stable politically

during the 58-year reign of Pedro II ... until in 1889 the Brazilian

military conducted a coup, establishing a Brazilian republic.

The Monroe Doctrine (1823).

Meanwhile (going back to the 1820s), during all this turmoil brought on

by the French Revolution and Napoleon's Empire, there was no way that

either Spain or Portugal were ever going to allow the independence of

their colonies ... and thus they both fought back fiercely against the

independence movements going on there.

But all of this confusion had allowed the very entrepreneurial British

to quietly slip into the American dynamic ... to develop strong

commercial ties of their own with these colonies. Thus Britain

had no intention of ever letting their American clients be drawn back

into the mercantilist privileges7 of Spain and Portugal.

But, most cleverly, the British let the American President Monroe state

the case for both Britain and America in this matter: America

would not let any European power restore its colonial empires on its

side of the Atlantic. That might have appeared as an incredibly

stupid pronouncement coming from a very recently established and

untried republic. However ... it was well understood by all that

the might of the British navy was what stood behind this "Monroe

Doctrine" (1823), giving it its muscle.

7Mercantilism: where colonies were permitted to trade only with the imperial mother country ... and no one else.

Ferdinand VII of Spain (ruled briefly in 1808 and then 1813-1833)

September 16, 1810 - Father Hidalgo begins the Mexican independence movement

(completed in 1821)

American President James Monroe - author of the "Monroe Doctrine"

protecting Hispanic-American independence from a Spanish reaction

(actually backed up by British naval power)

At

this point the sole agenda of the Congress of Europe – now including

only Austria, Russia and Prussia as its mainstay – was the defense of

the autocracy of these three powers. But that was going to come

under increasing challenge from liberal quarters.

France

Unsurprisingly, there had existed in France a very anti-Revolutionary, anti-Napoleonic mood amidst

the returned nobility ... and even in some parts of the French

countryside. Louis had tried to walk a line of moderation between

those French with fond memories of the Empire and those French with a

burning hatred for everything and everyone Napoleonic. But he was

old and sick ... and up against his younger brother, who was a leader

of the anti-Napoleonic reaction. Worse, Louis had no heirs

himself and it looked as if the throne would pass to his younger

brother upon his death.

Indeed, only ten years on the throne, Louis died in 1824 ... and his brother Charles X became France's king. Unfortunately, Charles was too thick-headed

to understand what his older brother had understood ... and proceeded to try to move the Bourbon monarchy back

to the status it possessed prior to the Revolution. The only

people this would please was the small group of ultra-royalists among

the returning émigrés. But Charles's actions greatly alienated

much of the rest of French political society – a large section of

France comprising the middle and upper middle class ... and the citizens

of Paris of all social orders.Finally bringing things to an explosive head, Charles foolishly

responded to the growing opposition to his rule by publishing the "July

Ordinances" of 1830, which dissolved a newly elected Chamber of

Deputies (which had returned an even larger number of liberals opposed

to Charles), and called for new elections ... allowing only a very

small number of voters to participate. A number of Paris

journalists protested his move ... and were soon joined by a Paris mob

filling the streets. Soldiers sent out by Charles to suppress the

mob were attacked savagely by the protesters ... with many soldiers

soon joining them.

Fearing that all of this was heading toward a restoration of Republican

France, French political leaders Talleyrand8 and Thiers put before the

Chamber of Deputies the name of Louis Philippe, Duke of Orleans, as a

new king to replace Charles X (who was forced to step down) ...

entitling him as "king of the French by the will of the people" (rather

than the old Bourbon formula: "king of France by the will of

God"). Thus the Orleanist wing of the old Bourbon monarchy took

power in France ... with Louis Philippe I posing himself as the

"bourgeois king" (mostly an act!).

The uprising (which had never extended outside of Paris) quickly

settled down. Overall the French were enjoying a period of rising

prosperity brought on by the fifteen years of peace and were now

relatively content with the shape of things politically in France.

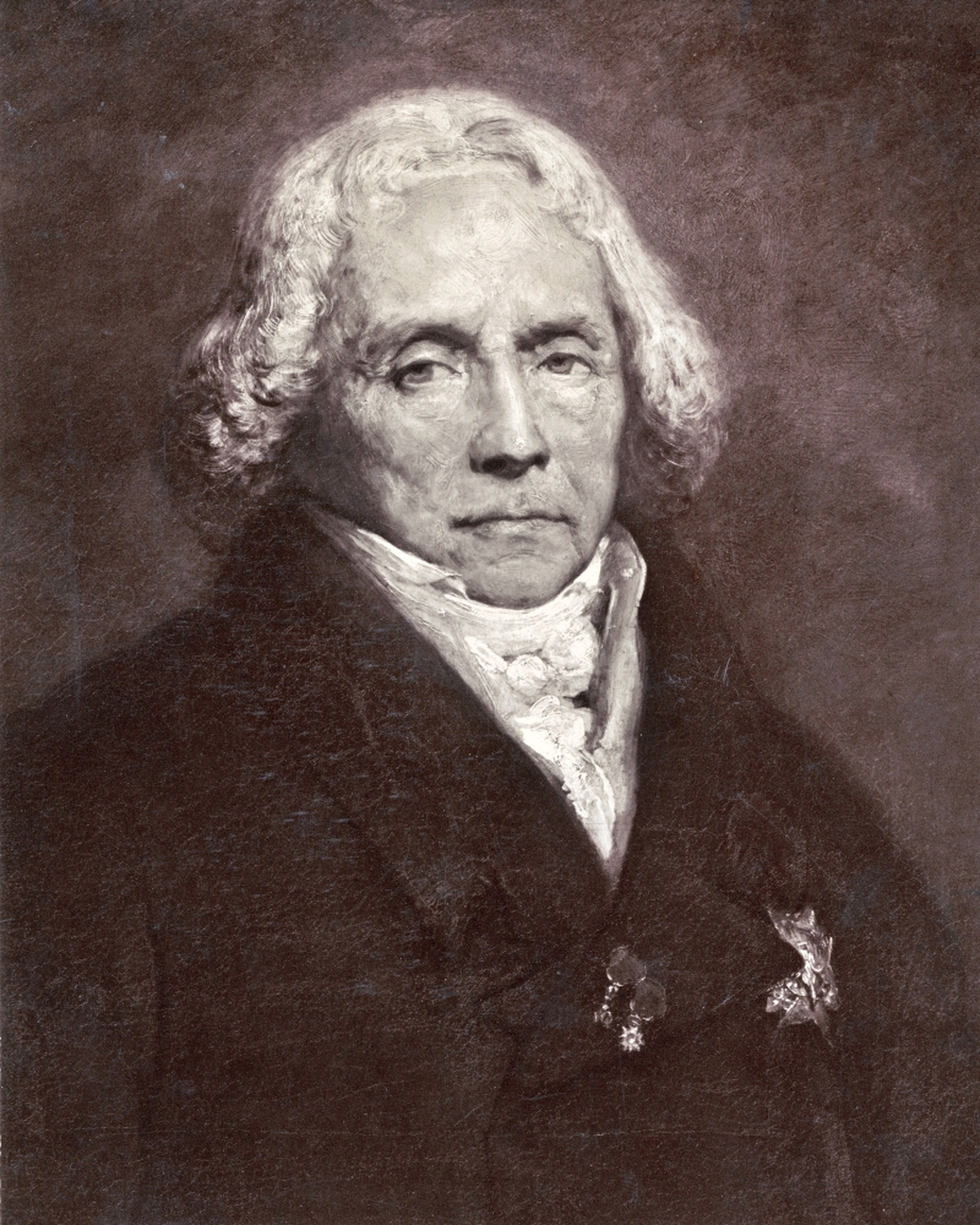

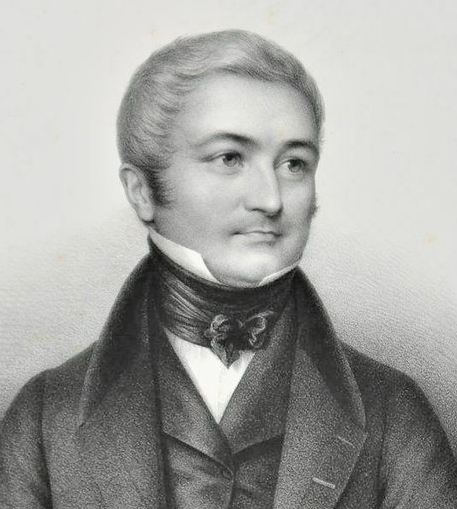

8Although

this period is known as "the Age of Metternich," Talleyrand was himself

a most outstanding individual in the field of European politics during

this same period. He began his political life as a Catholic

priest, representing the Church in the court of Louis XVI. He

represented the First Estate (Church) in the Estates-General of

1789. Then, becoming anti-clerical, he joined the Jacobins!

He was sent to England in 1792 to represent the new French Republic ...

and remained there when France began moving toward the Reign of

Terror. He was forced out of England in 1794 and went to America,

staying there for two years. The new Directorate permitted him to

return to France ... and then appointed him as its Foreign

Minister! But he soon became a supporter of Napoleon, aiding

Napoleon in taking control of France from the Directorate. And

thus he became Napoleon's Foreign Minister! But his relationship

with Napoleon cooled when he found himself disagreeing with some of the

Emperor's diplomatic decisions, and he resigned his position in

1807. Then in 1814, Talleyrand played a key part in the

restoration of the Bourbon monarchy ... and was appointed as France's

chief negotiator at the Congress of Vienna. However for the

next fifteen years he stepped out of the limelight of French

politics. But he re-entered the spotlight in arranging for

Louis-Philippe to take the French throne in 1830.

Today his name mostly evokes the image of a cynical, self-serving

politician willing to pull almost any deal that would advance his

career. But actually it was the gain of France that seemed to

inspire most of his craftiness ... behind and above all else that he

did.

French King Charles X (reigned 1824-1830)

Eugène Delacroix –

Liberty

Leading the People (1830) oil on canvas - commemorates the July Revolution

of 1830

Eugène Delacroix –

Liberty

Leading the People (1830) oil on canvas - commemorates the July Revolution

of 1830

Paris, Musée du Louvre

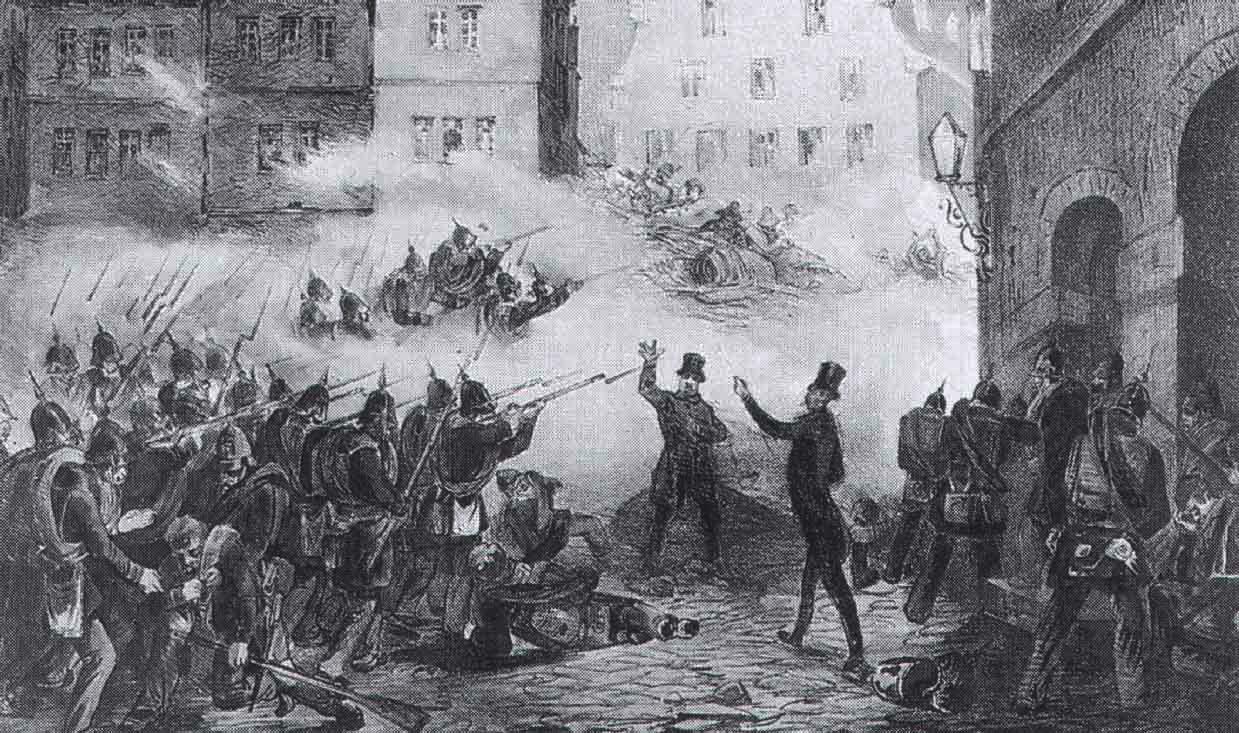

Events at

the Hôtel de Ville (left) during the July Revolution – Joseph Beaume

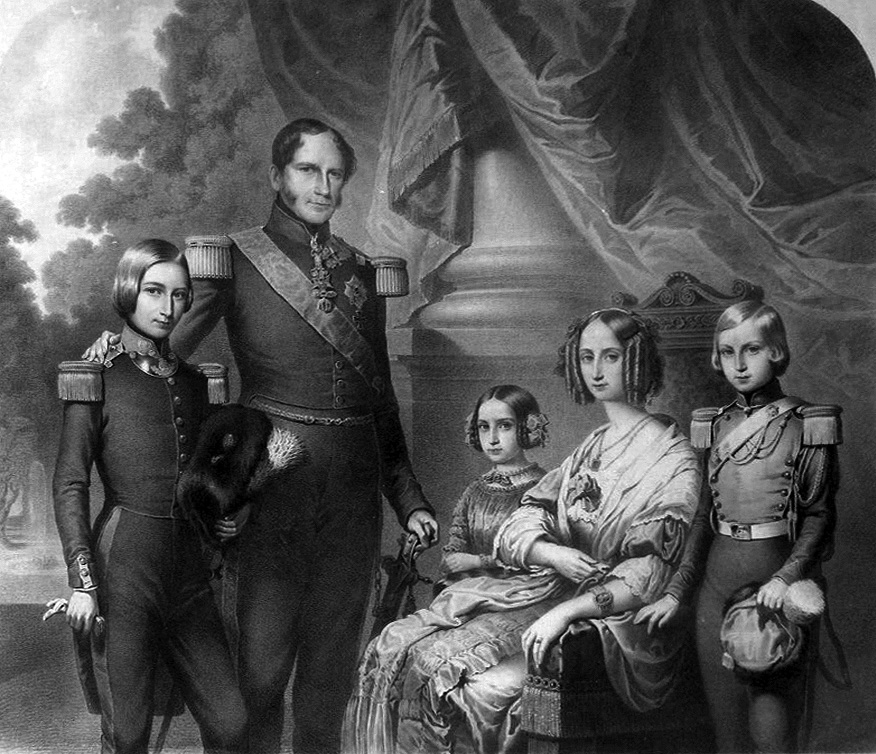

"Citizen-King" Louis-Philippe

of France (reigned 1830-1848) - by Franz Xaver Winterhalter - 1841

The King is depicted at

the entrance of the Gallerie des batailles

which he had furnished in the

Chateau de Versailles.

An older Talleyrand (Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

An older Talleyrand (Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

Adolphe

Thiers – French Prime Minister

(1836-1839)

|

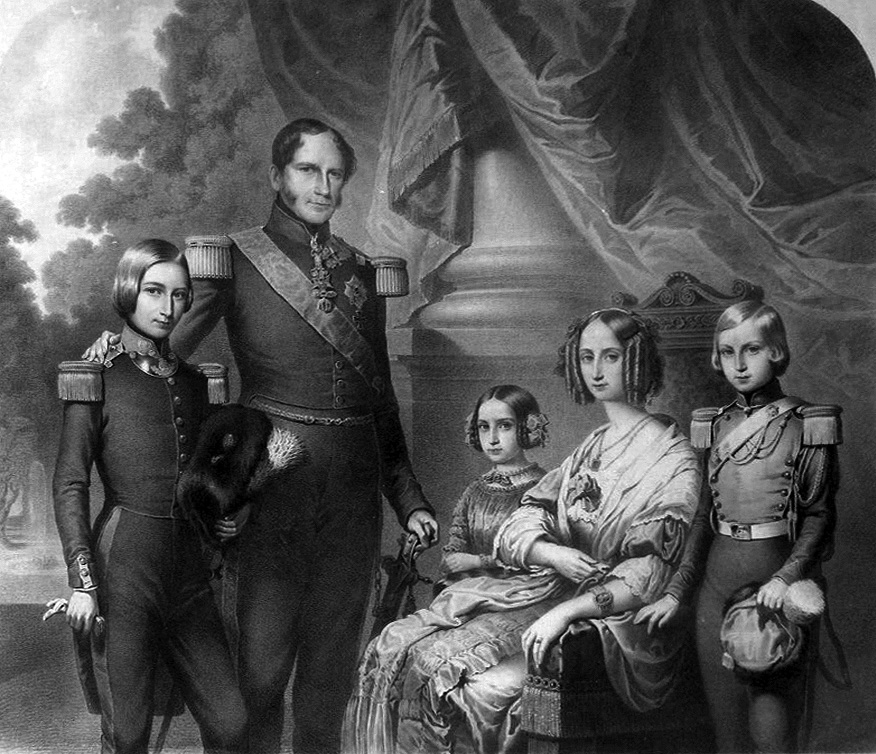

Belgium

The people of the southern provinces of the new Kingdom of the

Netherlands had, in earlier generations, been brought back forcibly to

Catholicism. This alone made them quite different from their

heavily Protestant northern neighbors. Also, the upper and middle

classes of this region spoke French rather than Dutch ... and were

greatly upset when their new king, William I, demanded that all

government work be done in Dutch (exempting only the French-speaking

Walloon districts bordering France).

William's high-handed ways so upset these "Belgians" that in August

(partially inspired by events in nearby Paris) protesters took to the

streets of Brussels as a result of an opera which stirred Belgian

feeling to a point of high indignation. Soon a street mob

developed, and began looting and pillaging the city through the

night. A group of alarmed citizens formed a Council of Regency

and proposed a separation of Belgium and Holland, with the king's

brother as viceroy of Belgium. William reacted to this challenge

by sending an army to Brussels ... which ran into such stiff resistance

that it was forced to withdraw. William was now willing to agree

to the Council's proposal. But it was too late. A

Provisional Government had been formed in Brussels.

At this point the other powers of the Concert of Europe weighed in on

the matter ... Prussia and Russia ready to invade, but France's Louis

Philippe threatened to counter their move. At a meeting in London

the Big Five powers called for an armistice ... then moved to recognize

Leopold of Saxe-Coburg as the king of Belgium. The Dutch

nonetheless sent an army to Belgium ... only to be countered by a

French army and a British-French blockade of the Dutch coast.

William now had lost the contest. But it would not be until 1839

that he would finally recognize the independence of Belgium.

|

Leopold Saxe-Coburg dressed as

a Russian general – by Geo Dawe (1823-1825).

Later, he become "Leopold I – King of Belgium" –

1831-1865;

he is also the uncle of Albert, Prince-Consort

of England (his nephew Albert is married to Queen Victoria)

St-Peterburg, Winter Palace

War Gallery

King Leopold I of Belgium

by Franz Xaver Winterhalter - 1839

Leopold I and family: Queen Louise-Marie, Crown

Prince Leopold, Prince Philippe, Princess Marie-Charlotte

|

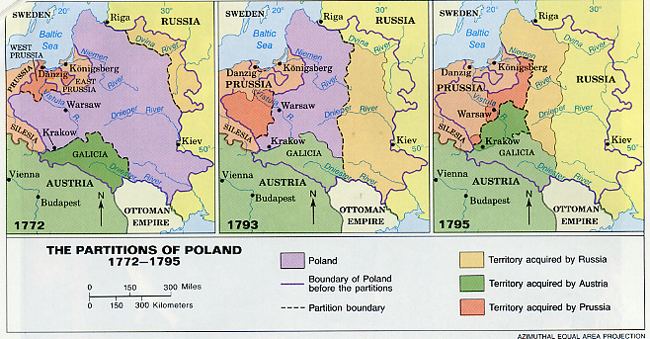

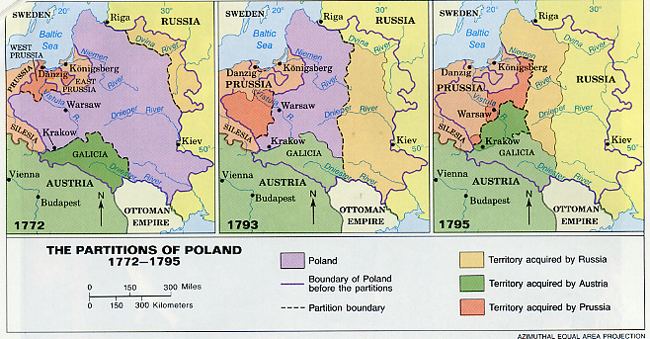

Poland

Not every such event in Europe ended up so successfully. Poland

had once been a powerful society (1500s and 1600s) but decline had set

in during the 1700s and the Poles found their society carved up in

three different stages of partition (1772, 1793 and 1795), being

completely absorbed or "disappeared" by the surrounding major powers,

Russia, Prussia and Austria with the last partition. But Polish

patriots fought alongside Napoleon in his wars against those same three

powers ... and Napoleon rewarded Polish support in 1807 by setting up a

Duchy of Warsaw. But at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 the duchy

was re-designated as a kingdom ... with the Russian Tsar as its king!

At first Alexander respected the more liberal character of the Polish

society and state, even allowing the Poles to continue to keep their

own flag, currency, military uniforms, and particular political

organization. But as Alexander turned more conservative – even

reactionary – he began placing tighter restrictions on Polish

society. When his brother Nicholas I took the Russian throne in

1825, he at first attempted to relax the restrictions ... until an

attempt on his life in 1829 turned him also towards repression of the

people under his rule.

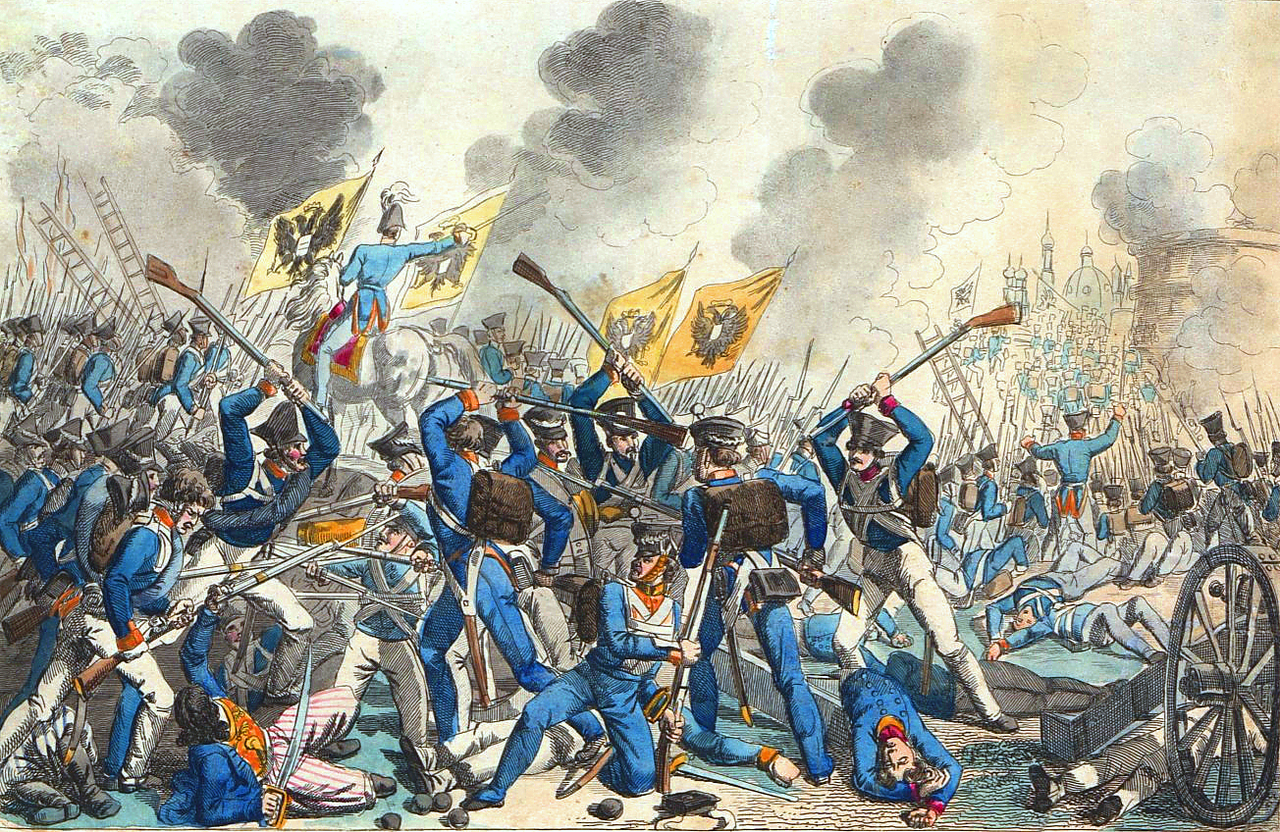

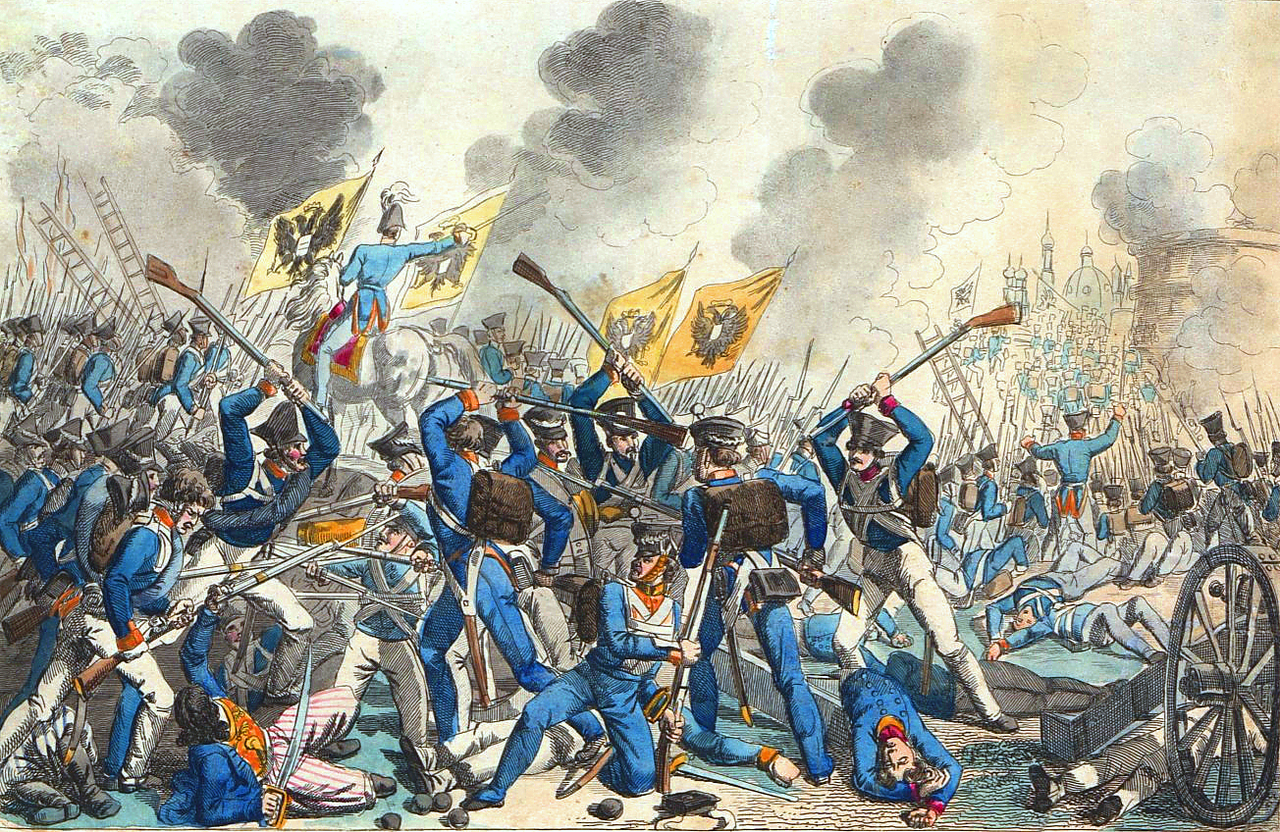

Towards the end of the following year the 1830 spirit of rebellion

spread to Warsaw, then to the whole of Poland. At first the Poles

were able to hold off an invading Russian army. But the Poles'

own lack of a unified command structure undercut their effort and in

1831 Warsaw fell to the Russians, ending the revolt. At this

point Nicholas declared the Polish monarchy expired, with Poland now

simply absorbed into the Russian state. However, although this

stopped Polish independence activity, it did not end the Polish dream

of national independence. In fact it served in the coming years

to make the dream even stronger in the hearts of Polish nationalists.

|

The Partitioning and official disappearance of Poland (in different stages)

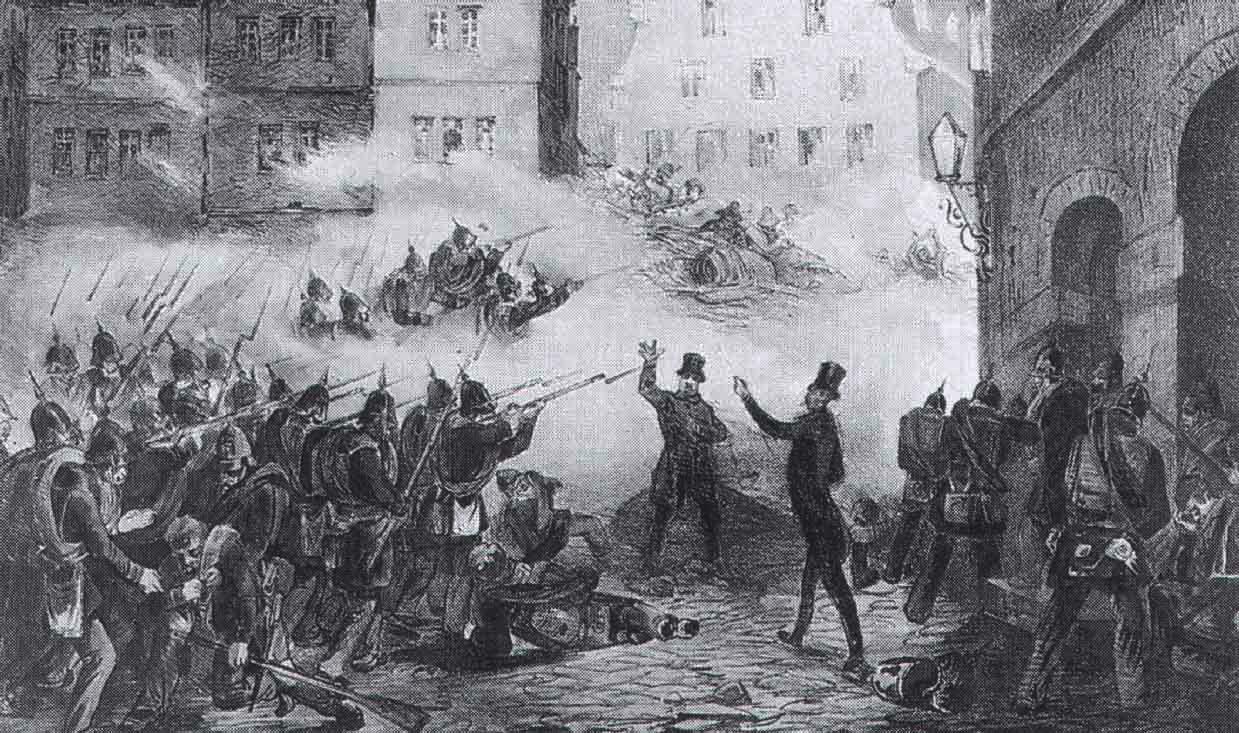

The Russian attack on the Polish forces at Warsaw - 1831

|

Political reform in Great Britain

Whereas the House of Lords was made up of high Church officials and the

British aristocracy, the House of Commons supposedly was a more

"democratic" part of the British Parliament. Since even the

Middle Ages, two members were elected from each of the counties and

towns (boroughs) making up the kingdom. But over the centuries

economic fortunes had changed and many of the towns had disappeared,

yet still sent two representatives to Parliament ... whereas major

industrial centers that had grown up in the past century (Manchester,

Birmingham, etc.) had no representation whatsoever. Furthermore a

few landowners of the empty boroughs (‘rotten boroughs') controlled a

number of seats; other seats were bought and sold like clothing

goods. The whole system therefore actually ended up representing

only a tiny portion of the entire British population.

With the democratic spirit spreading across the European continent in

1830, the mood soon reached the British shores as well. In 1830

the unloved George IV died and his place was taken by his more

liberal-minded brother, William IV ... who called for election, which

brought to power a reformist Whig majority led by Earl Grey.

After much action back and forth, a reform bill was finally passed into

law in 1832. It wiped out the rotten boroughs, gave new

representation to the industrial cities and made voting standards

uniform across the kingdom. It increased the suffrage, bringing

the comfortable middle class into the voting public ... though it still

set voting qualifications high enough that it excluded the multitudes

of industrial and farm workers making up the bulk of the British

population. Nonetheless, this marked a significant step forward

toward full democracy in Britain. |

William IV (ruled 1830-1837)

|

The expansion of "Democratic America"

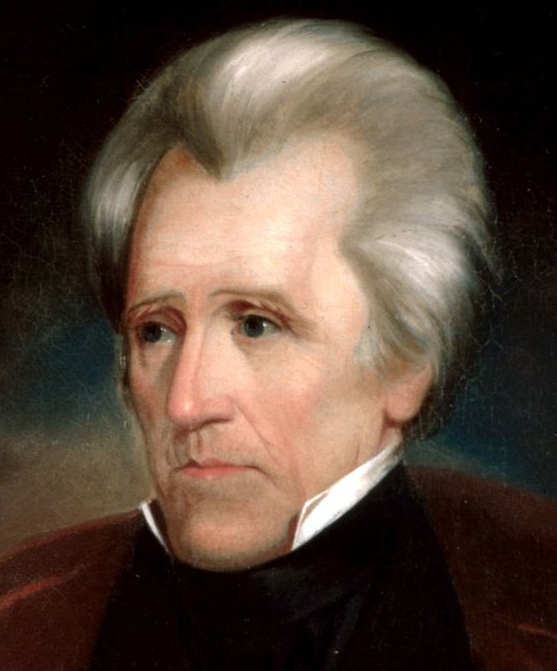

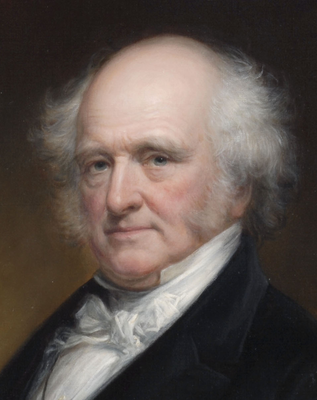

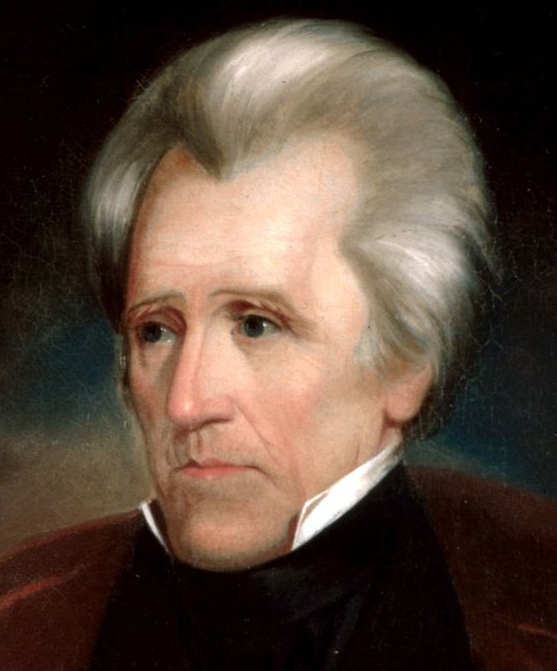

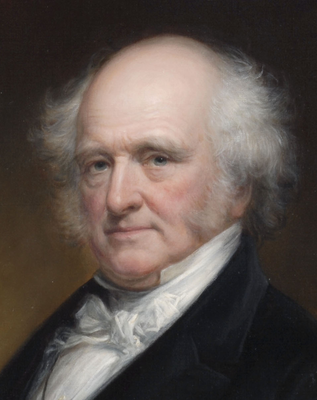

The Jacksonian "Democratic Revolution" (the 1830s).

The vote of the common people (at least for members of America's House

of Representatives) was not a new thing for the Americans. But

with the development of Andrew Jackson's Democratic Party (shaped and

directed in its activities by Jackson's assistant, Martin Van Buren),

America was understood to be led no longer by aristocrats (particularly

the Virginians – Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe) or the

Bostonians (the Adams, father and son) ... but by "one of the people" –

Andrew Jackson. Actually, Jackson was himself of aristocratic

background ... but played to the idea that he was just an ordinary

American. And indeed ... the common people, muddy boots and all,

invaded his presidential reception in 1829 (smashing dishes and

furniture in the process) to get close to their war hero and now

president, Andrew Jackson.

And so a new understanding filled the political atmosphere of America

... certifying the fact that politics belonged to the people themselves

... and not just a group of select aristocrats. Politics could

thus get very vulgar at times ... part of its being so

"democratic"! But America was very proud of itself in taking the

lead in this matter of "democratizing" their society's politics.

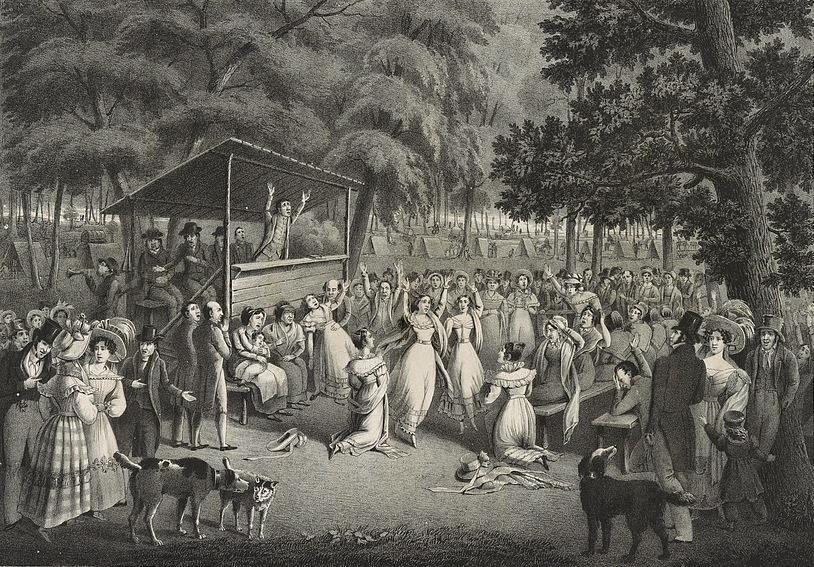

The "Second Great Awakening."

Behind this peculiar self-development of "Democratic America" was a

renewing of the popular spirit … one that had guided America through

the dark days of its war of independence from British King George

III. But this was a spirit then that had, like most things when a

crisis is over, settled back into a more mundane nature – a humanistic

spirit that sees itself guided by reason and logic rather than

unpredictable passion … and unpredictable sources, such as God himself.

The French found this American spirit most interesting, because it was

so different from what was the norm back in Europe. This

curiosity brought Alexis de Tocqueville and his associate Gustave de

Beaumont to America in 1831 to study America more closely. Then

in 1835 and 1840 Tocqueville published his two-volume findings, Democracy in America,

noting not only the basically egalitarian spirit of the American people

(easily challenging those who would take on airs of superiority),

something he understood derived from America's basically Puritan

origins. He also noted the restless and purpose-driven heart of

the American individual – who however (from his point of view) tended

to move on to new challenges before completing the old ones! He

also was most alarmed at how the slavery issue was crushing the

American soul, predicting (correctly) that failure to soon resolve this

issue would most likely lead to civil war in America.

But the American world of cool reason and logic supposedly

characteristic of the comfortable Americans soon came under

attack. A huge economic depression that hit America in the period

1837-1841 undercut deeply the idea that life basically worked along

quite rational lines. Such an event seemed at the time to be

unprecedented. Thus, even in the East, talk grew that America was

facing God's great Day of Judgment, the long-awaited return of Christ

to Earth – to judge all humankind. Americans needed to get their

act together spiritually.

Also … apparently masses of Americans, especially those that had

crossed the Appalachian Mountain Barrier and were heading ever-deeper

into Indian territory, were not seeing things in America's supposedly

humanistic fashion. Here on the Western frontier, hunger,

disease, and angry Indians awaited these bold souls willing to step

into such an unpredictable world. But comforting them was their

strong Christian faith that they were answering a call that God himself

had put on them … a covenantal call to advance their Christian realm

into the darker world of the American interior. And they

understood this challenge as one calling them to deal with this world

in front of them but also the world within themselves. They

needed to cleanse themselves of their own sins so that they could find

greater success in taking on this larger life – and ultimately get

themselves right with God.

To cultivate and direct this strong American spirit was a range of

individuals, most of them simple men who took up the call to pastor

(preach, teach, baptize, pray) the wide-ranging collection of

frontiersmen and their families. But a large number also were

just as active in the more settled East. There were also a number

of "prophets" who stepped forward to offer "updated" versions of the

Christian gospel, also collecting a huge following in the process.

By far the most active were the Methodist circuit riders, who braved

weather, hunger, and Indians to reach the scattered settlements of the

frontiersmen with their preaching and counsel. These were

ordinary men with extraordinary commitment, fueled by a religious fire

that actually started back in England at the turn of the century and

had been brought to America under the guidance of America's Methodist

Bishop Francis Asbury, a man himself who in a period of 1784-1816,

preached some 16,000 sermons over a course of as much as 275,000 miles

on horseback, and who grew the American Methodist community from 1,200

to 214,000 – with eventually 700 preachers to guide this huge

flock. He was followed by an even greater number of circuit

riders, some 3,500 of them, and nearly 6,000 Methodist pastors, who by

1840 had this community up to 750,000 members in size, the largest

denominational community in America.

Even the Black community got in on the act, with the African Methodist

Episcopal (AME) and AME Zion communities developing among free Blacks

in Philadelphia and New York City. These two groups would play a

huge role after the Civil War (1861-1865) in shaping the religious

lives of the multitudes of newly freed slaves.

And the folks back East were also invited to the world of camp

meetings, largely designed by the Presbyterian pastor Albert Finney,

who turned these meetings into well organized "revivals," ones that

would become something of a model for other revivalists – in his days

and even since then. So active was his revivalist ministry

that it seemed that there was no more work to be done in up-state New

York. It had become, what Finney himself termed, "a burned-out

district"!

Then there was the most unusual development with the up-state New

Yorker William Miller, who was able to bring a huge number of followers

to purify themselves in preparation for the "Advent" or Second Coming

of Christ ... which he predicted would bring the "Rapture" in April

(then October) of 1844. But disappointment did not discourage his

followers – who reformed themselves under the guidance of the female

prophet Ellen White as the "Seventh-Day Adventists," a group that would

grow internationally as well as nationally.

Also arising from the same "burned-out district" of New York was an

even stranger quasi-Christian movement: The Latter-Day Saints, or

"Mormons." Its founder Joseph Smith claimed angelic direction

(1827) in getting his new religious movement started up, complete with

its own Bible (The Book of Mormon)

and its own way of preparing for the second coming of Christ. But

so radically different was his "Mormonism" that his movement not only

grew monumentally in size, it succeeded in stirring up equally

monumental opposition from Christian neighbors. Thus he had to

move his huge community several times, before he himself was killed in

another such confrontation (1844). Ultimately a member of his

staff, Brigham Young, took the bulk of the Mormon community (there

would be other communities elsewhere as well) all the way to Utah, and

there set up his "Zion" headquarters for what would become a huge

international religious community.

There was, however, a calmer version of America's Second Great

Awakening, arising amidst the more traditional American denominations

... principally the Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Dutch

Reformed, although many Methodists (and Baptists) would soon join this

development. Two areas of action grew huge within these Christian

communities: the founding of colleges to further the world of

Christian knowledge and the creation of missionary societies to spread

the word – even abroad. Thus it was that jointly these

communities created the American Bible Society (to put a Bible in every

American home), the Sunday-School Union (to develop Biblical literacy

among America's children and youth), the American Tract Society

(offering an easy explanation of Christianity's basic themes and

doctrines), etc., etc. Equally amazing was the number of

Christian seminaries and colleges that were established during this

period, some 500 of them by the mid-1800s.

Literacy and knowledge were never intended to be the privilege of just

the upper ranks of society - as was the case back in Europe. This

was a privilege available to any American seeking such a goal in

life. America's democratic sense of the basic equality of all its

people depended on such opportunities being available to one and

all. You would have to work for it. Equality would not just

be handed to you on a silver platter. But it was there, freely

available to any and all who sought it. And Americans were

definitely just such seekers!

And that was America spiritually in the 1830s and 1840s!

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848).

Indeed, it was the urge of the American people themselves rather than

the designs of any government that had long been the foundation of

America's birth, growth and ultimately substantial national

power. And this democratic instinct driving America was not

likely to weaken ... as long as there was land to the West for

Americans to settle.

Texas would play a particularly key role in this matter at this point

(1830s) ... as thousands of Americans poured into what the neighboring

Mexicans viewed as a northern province of theirs (but sparsely

inhabited by Mexicans themselves at the time). Ultimately this

American "intrusion" brought war between the two groups ... with the

Texas-Americans soundly defeating the army of Mexican caudillo Santa

Anna in 1836. Mexico was thus forced to acknowledge Texan

independence.

But then the matter arose as to whether Texas would stand as an

independent nation or as an add-on to the United States, with the

Texans soon resolving the matter in favor of the latter. But this

presented a huge problem for the U.S. government... fully understanding

the outrage that Mexico would feel if Texas were to join the Union.

After being avoided as an issue by American presidents for the next ten

years, President Tyler and the U.S. Congress moved finally (1846) to

accept Texas's request for admission to the Union ... bringing Mexico

to immediately issue a formal declaration of war against the U.S.

But to the surprise of everyone (including most Europeans) the Mexicans

were quickly and decisively beaten in various battles ... not only in

Texas but in all of Mexico's northern territory – reaching even to

California. In fact, by September of 1847, American troops found

themselves fully in command of Mexico.

Thankfully both Congress and President Polk were wise finally to award

Mexico a $15 million payment for the territory taken from Mexico,

softening the blow greatly ... and gaining formal Mexican acceptance of

the transfer of lands. This piece of diplomacy would soon prove

to have been very, very important ... for in short order, defending the

American claim to these Western territories in the face of a Mexican

counter-move would have made a huge crisis hitting America at the time

(the American Civil War, 1861-1865) all the more disastrous for the

American Union.

|

Jackson (President 1829-1837)

Martin Van Buren

Jackson's presidential reception - 1829

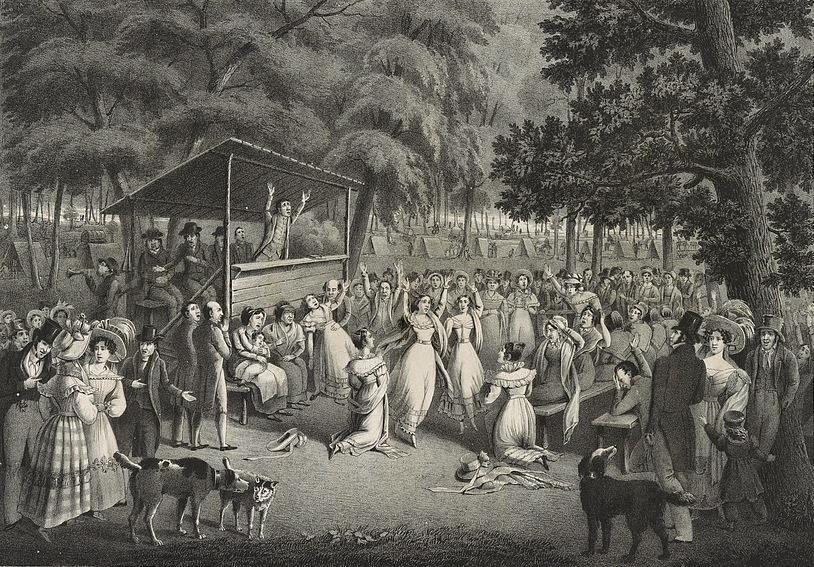

2nd Great Awakening camp meeting

2nd Great Awakening camp meeting

Santa Anna surrenders to the Texans - Battle of San Jacinto - 1836

Santa Anna surrenders to the Texans - Battle of San Jacinto - 1836

American troops in Mexico City - 1847

American troops in Mexico City - 1847

|

France

Louis-Philippe had cultivated his reputation as "citizen king" ... yet

at the same time he was as absolutist in his heart as any other

European monarch of his day. His prime minister, Guizot,

skillfully kept a working majority in the French parliament in support

of the king's increasingly restrictive policies, which clearly favored

the prosperous industrial upper middle class ... at the expense of the

French working class.

But the French working class – which had been the

backbone of the 1830 Revolution, but which had been denied any

political fruits from its sacrifices – was not unaware of its political

rights ... and importance ... in the French scheme of things.

French intellectuals attracted to the lofty ideas of "socialism" had

been clear about the key role that the working class was destined to

play in the industrial society taking shape in France. Being

hounded by the French police, secret societies began to be formed by

such socialists ... and also by republicans hoping to see France

returned to the status of a republic. All this (plus numerous

attempts at assassination of the king) made Louis-Philippe and Guizot

all the more resistant to any call for political reform.

By mid-late 1847 even members of the middle class

began to gather at special banquets to discuss the need for immediate

reform. Then in February 1848 a massive banquet was scheduled to

take place in Paris ... though Guizot convinced involved members of the

legislature to call off the event. But it was too late – for

things began to move forward anyway: the streets of Paris were

filling with people demanding Guizot's dismissal. The National

Guard was called out to disperse the rowdy crowds ... but refused to go

against the crowds, with some guardsmen even joining them. The

panicked king then dismissed Guizot ... but crowds gathered at Guizot's

home, protected by army regulars. Shots were fired and some 50

individuals were shot ... then carried through the streets on carts

that night. The next day a huge mob gathered at the king's

Tuileries Palace ... causing Louis-Philippe to flee the country in

disguise.

A new Republic was declared by a provisional

government ... and, following the lead of the socialist Louis Blanc,

the new government proposed – as a matter of the "right to work" – the

creation of workshops for the unemployed. At this, thousands of

unemployed workers gathered in Paris for jobs ... greatly exceeding the

government's real ability to set up workshops. Instead, the

government agreed to pay the unemployed a small financial compensation

... which (because of this generosity) by early summer had swelled the

ranks of the unemployed to over a hundred thousand! This not only

threatened the treasury of the new Republic, but left industries unable

to hire workers, who were content to live off the small dole rather

than the earnings of their labor.

The effort to bring some control over the program by

setting tighter qualifications for the dole now produced its own

political problems in the Paris streets. The Republic's military

was called in to disperse angry crowds, the soldiers fired on them (and

they fired back), with over ten thousand people killed or wounded in

the encounter. Martial law was extended over the country ...

while the Republican politicians quickly prepared the new Republican

constitution – which provided for universal adult male suffrage.

Finally in December of 1848 elections were held ...

and Louis Napoleon, nephew of the Emperor, was elected by a huge

majority of the French voters. A new era had begun in French life.

|

François Guizot

The Barricades at Rue Soufflot - June 25, 1848 - by Horace Vernet

The Dead at the Barricade of the Rue de la Mortellerie - June 1848 - by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier

Louis Napoleon - President of the Second French Republic (1848-1852)

|

The failed effort at Rome

In Italy, revolutionary radicals were demanding the creation of a new

Roman Republic - replacing the Papal States. In the chaos, Pope Pius

IX's Minister of Justice Peligrino Rossi was assassinated (November

1848). Also, the Pope’s protective French troops had just been

called back to France to deal with the chaos there ... leaving the

Pope’s own small army unable to hold back a much larger Italian army

intent on taking Rome. At this point Pius escaped to Naples ...

and the revolutionaries announced the formation of their Roman Republic

(also November 1848). The hope was clearly that this Roman

Republic would be the springboard for an even larger Italian Republic.

The Republicans authorized the pope to return to Rome to continue his

religious duties ... even though his political role as Head of the

Papal States was to be ended. But the pope was not interested in

the compromise. Indeed, in retaliation, Pius threatened

excommunication of those Catholics supporting the Republic ... even of

those who simply voted in the Republic’s new elections (there was a 50%

turnout however).

But newly elected French President, Louis Napoleon decided to come to

the aid of the Pope and sent a huge French army (along with some

Spanish troops) into Italy (April 1849). After a month’s siege at

Rome, the Republicans agreed to a truce ... which reestablished the

pope’s political powers - although Pius would not return to Rome until

the French troops agreed to full support of the papacy.

These troops would indeed continue in that role ... until 1870 when

another round of revolutionary events in Europe led to the creation of

the Kingdom of Italy – by many of the same individuals who had directed

the effort to establish the Roman Republic in 1848-1849.

The Austrian Empire

Meanwhile,

events in France had spread quickly eastward to Vienna, inspiring

equally dramatic events there. In March (1848) university

students and craftsmen joined forces to march on the emperor's palace

calling for Metternich's resignation. When members of the court

aristocracy joined in the demand, Metternich realized that he had lost

his political grounding ... and escaped to England. When the

Emperor agreed to institute a number of liberal reforms, the revolt

seemed to have achieved its objectives.

At the same time the French events had also stirred

up a similar spirit of revolt in Prague ... where demands for liberal

reform of the imperial government took on strongly Czech nationalist

tones. Now hard pressed by this spreading spirit of revolt, the

Emperor agreed to the demand to make Czech co-equal with German.

Hungary was next. Protesters gathered in

Budapest demanding a constitution and parliament of their own ... which

the Emperor agreed to institute. But then when other

minorities living within the Hungarian realm (Serbs, Croatians,

Rumanians) asked for similar rights, it was the Hungarians who refused

... causing war to breakout between Hungary the minorities.

In Austrian-controlled northern Italy similar events

unfolded. With the fall of Metternich in March, an Italian mob in

Milan forced the Austrian garrison to evacuate the city. Venice then

joined the revolt, then all of Lombardy and the Tuscany province ...

with Charles Albert, king of Sardinia-Piedmont, sending troops to aid

his fellow Italians. Various Italian states put themselves in the

hands of Charles Albert ... and the Italian coalition met the Austrians

in battle. The results were something of an Italian retreat ... leaving Italian

land in the hands of the Austrians. This in turned infuriated the

Italians ... and ultimately shamed Charles Albert. He then simply

abdicated, leaving his government in the hands of his son Victor

Emmanuel ... who now took a tougher stand against the Austrians.

Now the Austrians found themselves not doing very well in the contest

with the new "Italian" leader, Victor Emmanuel.

The Habsburg empire seemed to be crumbling

everywhere. So distressed was Emperor Ferdinand over all this

that he abdicated in December, elevating his 18-year-old nephew, Franz

Joseph, to the Austrian emperorship.9

9This would be the beginning of the 68-year reign of Franz Joseph, which would last until his death in 1916.

Charles-Albert of

Sardinia

(ruled

1831-1849)