11. THE "MODERNIZING" OF THE WEST

THE URGE TO RATIONALIZE AND CONTROL SOCIAL DYNAMICS

CONTENTS

Jeremy Bentham Jeremy Bentham

August Comte August Comte

John Stuart Mill John Stuart Mill

Darwinism Darwinism

Nietzsche Nietzsche

The assault on Christian morality The assault on Christian morality

Marxism Marxism

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 442-453.

A Summary of this Section

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), as a

British Liberal or "Utilitarian," sees the greatest happiness of the greatest number of people as the only measure of right and wrong.

However, he believes that only through proper moral discipline

this could all come about

August Comte (1798-1857) was

something of a French pragmatist (like the British) ... a "Positivist" – not persuaded by pure rationalism but instead by "scientific"

study – the source of "Progressivism."

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

develops his own Positivism – seeing life improved through careful intellectual development ... not by government officials but

through personal development.

But the context of that development must be carefully shaped

... including a religion that leads a person to higher thought.

Such thinking becomes the basis for the British Liberal Party's

role in British society.

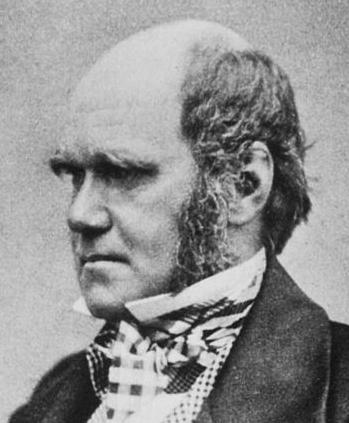

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) –

through his own biological research gives support to the growing Malthusian view that the strongest should most naturally lead society and allow the weak to simply fall away

... an idea actually begun by his grandfather, Erasmus, who published (1796)

Zoonomia on biological evolution.

Darwin's 1859 On the Origin of Species seems to lock

biological evolution in place as absolute truth.

His 1871 Descent of Man also locks in place the idea as

man evolved from a simple primate (something of the "monkey" family).

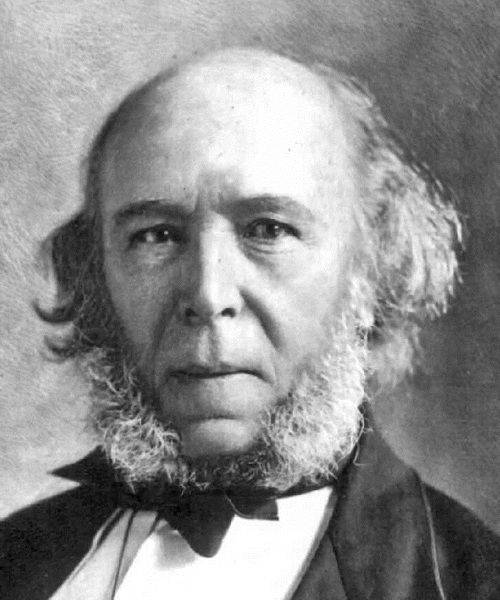

Herbert Spencer (1820-1903)

popularizes Darwinism even further.

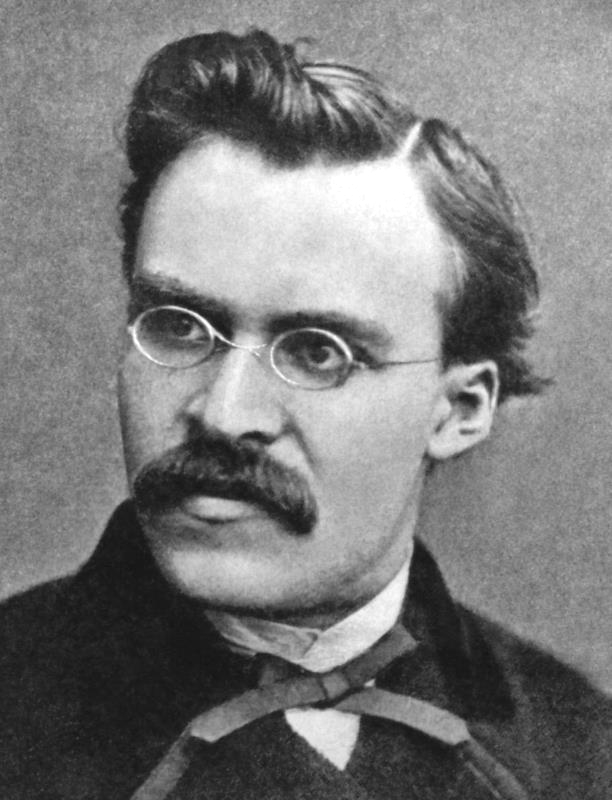

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is supportive of similar intellectual development – in the creation of the superior individual (the

Ubermensch) ... not some superor social group or nation in the Hitlerian sense of Ubermensch ...and is contemptuous of Christianity (teaches "commonness"), Heaven (no

proof) and God ("dead")

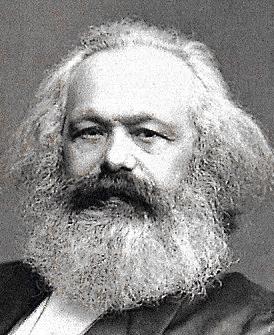

Karl Marx (1818-1883) sees

nationalist struggle as highly diversionary ... from the real class

struggle – between the wealthy owners and the impoverished creators of

society's fruits ... the coming phase of that struggle taking the form of industrial workers (the proletariat) rising

up against industrial owners (the capitalists)

He was hoping that the 1848

uprisings were the signal for this workers' revolution – publishing his Communist Manifesto in support of just

such an uprising ... and getting him in more political trouble and forcing him to move to London in 1849.

There he undertakes to make his

theories "scientific" in a Darwinian way ... history "proving" such

social evolution (his two-volume Das Kapital – published in 1867 and 1885)

Bentham's Utilitarianism.

Going back a bit in our narrative, it is important to mention the

legacy that Bentham (1748-1832) had on the development of British

social thinking at the end of the 1700s and beginning of the 1800s. Bentham's Utilitarianism.

Going back a bit in our narrative, it is important to mention the

legacy that Bentham (1748-1832) had on the development of British

social thinking at the end of the 1700s and beginning of the 1800s.

Bentham is considered to be the founder of British Utilitarianism ... a

philosophy built simply on the idea that "the greatest happiness of the

greatest number is the true measure of right and wrong." In

short, he was a strong advocate in favor of "human rights."

He was highly opposed to slavery, believed in equal rights for women,

was a strong advocate of the separation of church and state, was

opposed to physical punishment, and believed strongly that there should

be no restrictions on speech. He even supported the idea of

animal rights. But he spent his greatest energies on the matter of

prison reform. In short, he was a very "modern" philosopher and

jurist!

But he did not believe that all of these came simply by lifting

traditional Christian moral standards ... as if these "human rights"

would come into place on their own in a rather natural manner (as did

Marx and other philosophers that came after him). To him, human

rights would come only through proper moral and political reform of

society ... enlightened social reform – principally by enlightened

public authority. In short, under British utilitarianism, the

primary role of government was to oversee the process of human progress.

The

Frenchman Auguste Comte (1798-1857) reacted to the sometimes wild

speculation of French rationalists, who during the previous century had

built their philosophical theories on "reasonable" propositions –

rather than on the observation of actual phenomena. In short, he

introduced British empiricism to French or continental philosophy,

terming his approach "positivism." The

Frenchman Auguste Comte (1798-1857) reacted to the sometimes wild

speculation of French rationalists, who during the previous century had

built their philosophical theories on "reasonable" propositions –

rather than on the observation of actual phenomena. In short, he

introduced British empiricism to French or continental philosophy,

terming his approach "positivism."

He was particularly interested in seeing social philosophy built on

very careful observation of actual social behavior rather than mere

rationalist speculation ... such as Rousseau's social theories a

half-century earlier, which had helped push France towards the tragedy

of its recent Revolution. Thus Comte laid the groundwork for the

field of modern sociology with its demand for "factual" foundations for

all assertions of truth.

In his major six-volume work, Course of Positive Philosophy (published

in the period 1830-1842), he stated that human knowledge began in its

primitive stage as theology, or laying all events at the feet of divine

forces or God (related to the Divine rights claims of monarchical

authority). The next stage, the rationalist or philosophical

stage, was then characterized by broad abstract principles as the

foundation of truth or knowledge (he had in mind the rhetoric of

Revolutionary France). But the rising stage that the world found

itself entering at this point (a pragmatic, bureaucratic

post-Revolutionary France) would now be built on the works of

scientific scholars who would direct society through their knowledge of

actual fact-based science.

Most interestingly, none of Comte's Positivism or Progressivism itself

was itself based on the empirical methods he called for in his study –

but was instead a continuation of the French rationalist approach to

knowledge!

Nonetheless his ideas would catch the imagination of 19th century

Europe and help move it toward the notion that all truth is built on

fact and fact alone.

Mill

(1806-1873) was an amazing child prodigy, reading classic Greek

literature (from Aesop to Plato) by age 8, then a full array of Latin

and Greek works by age 10 ... plus history, math, physics and

astronomy. In all of this, he was carefully "home schooled" –

pruned and protected in his infancy and youth by his father, James Mill

– in order that the son would be "associated" only with the sharpest

minds (his father's and that of the family friend Jeremy Bentham) ...

and not with lower social orders of his own age ... a key part of the

educational philosophy of the British "Positivist" movement. His

father's goal was to grow his son into "a bright light of Utilitarian

philosophy that might light the world." In part the father

succeeded, though at a deeply heavy emotional and spiritual cost to the

son. Mill

(1806-1873) was an amazing child prodigy, reading classic Greek

literature (from Aesop to Plato) by age 8, then a full array of Latin

and Greek works by age 10 ... plus history, math, physics and

astronomy. In all of this, he was carefully "home schooled" –

pruned and protected in his infancy and youth by his father, James Mill

– in order that the son would be "associated" only with the sharpest

minds (his father's and that of the family friend Jeremy Bentham) ...

and not with lower social orders of his own age ... a key part of the

educational philosophy of the British "Positivist" movement. His

father's goal was to grow his son into "a bright light of Utilitarian

philosophy that might light the world." In part the father

succeeded, though at a deeply heavy emotional and spiritual cost to the

son.

Utilitarianism, Positivism, or Liberalism – all amounted to pretty much

the same thing: holding the common view that a person is born

with no a priori thoughts or abilities ... but as a thinking creature

is simply the result of careful development by guiding hands –

hopefully ones that care deeply for the happiness of those in their

care. It was all very personal. Liberals (both Americans

and British, from Jefferson to the Mills) viewed with great distrust

the intervention of public authorities in this process. In short,

"the best government is the one that governs the least!" This

would be a central tenet of Mill's Utilitarian or Liberal philosophy.

The understanding was that simply a person becomes what the surrounding

world brings to that person ... nothing more, nothing less.

Therefore that surrounding world – physical as well as social – must be

carefully shaped, engineered, protected. But this must be carried

out on a personal or individual basis ... not on a public or

Socialistic basis. Personal freedom was essential to proper development.

Thus it was that Mill would later reject deeply the ideas of his former

mentor, Bentham. Mill would disagree strongly with Bentham that

social progress would come best through the process of well-constructed

government action … Mill holding to the later developing idea that

social progress would fare better under personal or private development

than under official governmental action … which to subsequent British

Liberals was central to their idea of the critical importance of

personal freedom.

However ... Mill was closely connected with the British administration

of India – being a high-ranking official from 1823 (at age 17!) all the

way to the end of the East India Company in 1858. In this matter,

he would, take a broader view of the responsibilities that fell to

"more enlightened" social hands in face of a "barbarian" society.

Something akin to social action or "benevolent despotism" would be

required under such circumstances ... but must be carefully conducted

so as to benefit and not just merely subdue such a barbarian society.

And as far as an issue under much discussion at the time, Mill felt

that religion was the highly laudable ability of human thought to rise

above the merely physical or natural condition of life to contemplate

and be moved by ideals of excellence. But whether there was a

supreme Deity or consciousness to which human thought draws itself – or

which energizes the forces of life as Creator and Sustainer – was a

most uncertain proposition for Mill.

In any case, the very simplicity and the very attractiveness of

Utilitarian or Positivist "Liberalism" would catch on widely in the

fast-changing political setting of 19th century Britain. And

Mill, with his many publications, would be one to give great clarity

and appeal to this idea ... also helping to make the British Liberal

Party a growing force in British politics.

When

in 1859 Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his book, On the Origin of Species – the

culmination of years of research and earlier publications – he shook

the moral foundations of Western civilization. This occurred not

because Darwin invented a new worldview out of thin air. The

ideas of progress through social struggle were by this time rather

widely accepted. The British Whig party, in fact, was built on

this idea: that Britain should be run by those proven strongest

in life's competition and that no tears should be wept for the poor

swept aside by life's struggles, because that would only hinder human

progress. When

in 1859 Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his book, On the Origin of Species – the

culmination of years of research and earlier publications – he shook

the moral foundations of Western civilization. This occurred not

because Darwin invented a new worldview out of thin air. The

ideas of progress through social struggle were by this time rather

widely accepted. The British Whig party, in fact, was built on

this idea: that Britain should be run by those proven strongest

in life's competition and that no tears should be wept for the poor

swept aside by life's struggles, because that would only hinder human

progress.

No, it was not the newness of Darwin's ideas that made his works so

spectacular, but it was because he gave such precise explanation – and

justification – to these Whiggish ideas. His great contribution

to this debate of worldviews was that he built his Darwinist theory of

life on a vast field of scientific evidence, something that had by that

time become the absolute requirement for any claim to Truth.

Also, he was building his ideas on a well-established base of earlier works on this matter of evolution.

Robert Malthus … and early versions of "survival of the fittest"

Since

the publication in 1798 of the book An Essay on the Principle of

Population by the English clergyman Robert Malthus, there was

considerable discussion in England about the problems created by a

rapidly expanding human population on the earth, the issues of hunger,

disease and war that this would produce. Consequently, by the

time of Darwin's 1859 publication, a number of leading political and

intellectual figures in England had already taken the social position

that the best thing to do about the rising number of English poor was –

by a process of natural de-selection – simply to let them maintain a

natural balance with their world by the thinning of their ranks through

hunger and disease. It was thus wise not to encourage their

expansion through unnecessary charity. Since

the publication in 1798 of the book An Essay on the Principle of

Population by the English clergyman Robert Malthus, there was

considerable discussion in England about the problems created by a

rapidly expanding human population on the earth, the issues of hunger,

disease and war that this would produce. Consequently, by the

time of Darwin's 1859 publication, a number of leading political and

intellectual figures in England had already taken the social position

that the best thing to do about the rising number of English poor was –

by a process of natural de-selection – simply to let them maintain a

natural balance with their world by the thinning of their ranks through

hunger and disease. It was thus wise not to encourage their

expansion through unnecessary charity.

Charles Lyell (1797-1875)

In the early 1800s, at the same time that biology was moving toward the

development of a theory of natural evolution, similar work was moving

ahead in the area of geology. The most notable figure behind this

work was Charles Lyell.

Lyell had developed an early curiosity about different earth formations

in England into a full-blown quest to give an explanation for the

layers of the soil that he observed within the country's cliffs and

mountains. On a trip to Italy in 1828-1829 where he studied Mt.

Etna, he came up with the idea that all these geological features

(mountains, valleys, islands, deserts, etc.) did not occur abruptly –

but were the process of gradual shifts (volcanos) and decay (erosion)

in the earth's surface ... taking place naturally over a very long

stretch of time, a process continuing even into the present.

Further study in Spain the next year led him during the period

1831-1833 to publish his 3-volume work, Principles of Geology.

Loaded with supportive data for his theory, the book was to make a

tremendous impact on his time.

Overall, Lyell presented a view of the earth as being both very old

(older than the calculus of those who reckoned the earth's age on the

basis of adding up the Genesis chronologies) – possibly even millions

of years old – and very much still in the process of becoming. To

him the earth was even to be looked upon as a living organism.

An earlier Darwin

An earlier Darwin

We

have already introduced Lamarck as a major part of this dynamic.

But it is also interesting to note that Lamarck was himself influenced

by Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin

(1731-1802), who in 1796 described in his publication Zoonomia how

species had developed slowly over the generations by their abilities to

pass on from generation to generation not only their basic traits, but

also useful alterations in those traits. Thus Erasmus's grandson

Charles Darwin came from a family already securely located in the

evolutionist camp!

Darwin himself

Then what Darwin achieved in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species

was to show through actual scientific analysis how living creatures on

this planet could have evolved slowly over an enormous expanse of time

from a small number of simpler forms into a vast array of much more

complex species. All of this could have been achieved entirely

through a natural or mechanical process by which the very competitive

nature of life rewarded the stronger offspring of any species the

better chance for survival, and the privilege of birthing a new

generation that retained that superiority. Eventually this

struggle for life – and its continuation from generation to generation

– would, over time, bring into existence a distinctly new, more complex

species, one better adapted to the complexities of life.

Thus every living creature we saw around us was naturally evolved from

a less complex ancestor by a process termed "natural selection."

In short, morally speaking, life was at its core simply a matter of the

survival of the fittest.

It was Darwin's Cambridge University teacher, John Henslow, who

arranged for Darwin in 1831 to sail on the British naval ship Beagle to

the South Pacific islands just off the coast of South America ... and

who urged him to take with him a copy of Lyell's Principles of Geology.

Lyell's vision of even the earth itself as a living, developing

organism touched Darwin's thoughts deeply. With this sense of a

dynamic earth in mind he thus came up with an unprecedented (and

correct) explanation of how coral atolls were formed out on the high

sea.

Nature cooperated in the process. While he was in Chile an

earthquake took place in which he actually observed the land rise in

front of him. Thus the concept of a dynamic earth was not merely

a theoretical one for him. He also observed strata of sea shells

in the mountains at a height of 12,000 feet, lifted over time from an

earlier position as a sea bed.

What he was doing was giving further support to Lyell's view of the

earth's natural life – support so extensive that the world of learned

scholars felt themselves forced to look upon the earth in this way from

this time on.

Upon his return to England in 1836 he was greeted easily as an

accomplished colleague by the scientific community. But he was

just getting started. His thoughts returned to the questions of

why life took the shape it did – which increasingly left God out of the

picture.

Darwin was not really a radical by nature, and for years kept his

thinking to himself. But he was thinking thoughts that he knew

would not be well greeted by many in his times, including his devoutly

Christian friend, Henslow.

Actually it was in 1842 that Darwin first drafted a brief version of

his theory and then two years later a full draft version – but was

unwilling to bring it before the public because of the furor he knew it

would stir. He would show it only to close friends such as Lyell

and Thomas Henry ("T.H.") Huxley. Finally in 1858 he was inspired

to act when he received a paper from Alfred Wallace, a botanist working

in the Malayan islands, a paper which pointed to the same hypothesis he

had been developing. His friends urged him to bring out his own

thoughts on the subject in a joint paper worked up with Wallace –

presented that summer. With this he was ready to bring out his

full work, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

In November of 1859 he presented his first edition – which was bought

up immediately and quickly went to further editions (6 such editions

over the next 13 years). The English scientific community was

highly approving; the clergy were adamantly hostile, as he expected.

His friend Huxley only added fuel to the fire by extending the logic of

his friend's theories into the realm of social action, cultivating a

theory known as "Social Darwinism." It was Huxley who came up

with the idea that brutal competition in society or "survival of the

fittest," was a necessary part of the advance of mankind.

Darwin was himself not a proponent of this view – but soon became identified with it.

Other books by Darwin followed over the next years – the most important of which was The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex

(1871). Here he came out directly with what had only been implied

in his Origin, namely that even man himself was the by-product of the

evolutionary process, not only physically but also morally and

spiritually. This of course challenged the notion that man was a

very distinct part of the Creation process – but instead was merely

another, albeit a highly evolved, by-product of the on-going mechanism

of evolution. In 1872 he went a step further in his The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals,

stating the the emotions we attribute uniquely to man are in fact

shared in some less evolved ways with other members of the animal

kingdom.

Herbert Spencer

Darwinism was further buttressed by the writings

of other social philosophers of the day. Besides Darwin's pupil

Huxley, who actually coined the term "survival of the fittest,"

there was Huxley's friend Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), who had been moving in the

direction of Darwin's thinking even before Darwin published his first

work in 1859. Spencer had been working on both social theory (his

1851 Social Statistics) and personal development theory (his 1855

Principles of Psychology), his work heavily influenced not only by

Malthus but also by the theories of Lamarck. Then when Darwin's

work was published in 1859 Spencer came out full force in his support

of evolution as the basic doctrine of life, in every aspect of life on

earth. Darwinism was further buttressed by the writings

of other social philosophers of the day. Besides Darwin's pupil

Huxley, who actually coined the term "survival of the fittest,"

there was Huxley's friend Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), who had been moving in the

direction of Darwin's thinking even before Darwin published his first

work in 1859. Spencer had been working on both social theory (his

1851 Social Statistics) and personal development theory (his 1855

Principles of Psychology), his work heavily influenced not only by

Malthus but also by the theories of Lamarck. Then when Darwin's

work was published in 1859 Spencer came out full force in his support

of evolution as the basic doctrine of life, in every aspect of life on

earth.

Soon Spencer would even outdistance Darwin as the most recognized

philosopher of the late 1800s. But the very names Darwin and

Darwinism would still serve as the most powerful symbols able to raise

strong debate, pro and con, not only well into the 20th century but

still even today.

The

German philosopher and writer Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was not exactly a

Darwinist, but certainly was – or would soon become – a voice of his

times, a period deeply steeped in the Darwinist mindset. In his

multi-volume series Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra),

he gave the German culture the ideal of the bermensch – except that he

was referring to the highly achieved individual – not some racial

group, such as the Nazis would eventually use the term in reference to

the German people as a whole, seeing themselves as a superior

breed. Nietzsche was referring to the highly self-cultivated

individual who (reflective of Nietzsche's own personal struggles) had

come to put aside all other values (wealth, sex, even happiness) in

order to focus completely in meeting fully the high calling that fate

had placed on that person. Such a person strove to rise above the

mere animal call to life – to rise above ( ber) mere common existence

as a person (Mensch). The

German philosopher and writer Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) was not exactly a

Darwinist, but certainly was – or would soon become – a voice of his

times, a period deeply steeped in the Darwinist mindset. In his

multi-volume series Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke Zarathustra),

he gave the German culture the ideal of the bermensch – except that he

was referring to the highly achieved individual – not some racial

group, such as the Nazis would eventually use the term in reference to

the German people as a whole, seeing themselves as a superior

breed. Nietzsche was referring to the highly self-cultivated

individual who (reflective of Nietzsche's own personal struggles) had

come to put aside all other values (wealth, sex, even happiness) in

order to focus completely in meeting fully the high calling that fate

had placed on that person. Such a person strove to rise above the

mere animal call to life – to rise above ( ber) mere common existence

as a person (Mensch).

In fact, with respect to the ideal of the racial bermensch, he was

actually much opposed, getting himself in trouble with the German

authorities for his strong anti-nationalism. He even at one point

renounced his Prussian citizenship. No, Nietzsche was extolling

the powerful individual that he claimed should be directing human life

on this planet, not the group-think of the rising nationalist spirit

that he saw developing around him – one which would eventually lead

Europe into the disastrous national or tribal conflict known in its

time as the Great War and to us today as World War One (as well

as its continuation as World War Two a generation later).

He also was distinctly an atheist – informing the world that "God is

dead." He (like Marx) saw the Judeo-Christian religion as

offering humanity only enslavement to earthly commonness by teaching

people to aim not for greatness in this life – but instead to aim for

some supposed afterlife that Judeo-Christianity claimed awaited the

humble and faithful at death. Nietzsche was very emphatic in

stating that there was no evidence whatsoever that such a Heavenly life

actually existed.

THE ASSAULT ON CHRISTIAN MORALITY |

As

an Anglican clergyman, Malthus himself had, back in the late 1700s,

wrestled with the problem of why God would allow suffering to occur

within his creation. Malthus finally concluded that God wanted

man to rise to the challenge of life, to succeed in the face of life's

difficulties through the discipline of hard work. Those who fell

short of the challenge were simply some kind of disappointment to the

great Creator. Those who failed merely reaped that which they had

sown.1 This in essence was the British version of Sturm und Drang!

Malthus's explanation of course was a terrible reading of what the

founder of the Christian faith himself had taught the world.

Jesus put the challenge not in terms of natural selection, but quite

the opposite. According to Jesus, the challenge of life was to

find ways to help the poor in the face of the huge challenge of

survival in a competitive world of economics and politics. This

ability to do charity, when the opposite would be so much more

tempting, was for Jesus the measure of greatness of anyone in God's

kingdom.

At some point people were going to have to choose between the two,

Jesus or the Darwinists. The original Puritans had chosen Jesus, and

built an experimental society of mutual service among social equals

based precisely on the spiritual ethics of Jesus Christ. The

Virginians, not exactly Darwinists but of the same mindset, chose

instead personal success at the cost of others (the slaves). Thus

by the mid-1800s this was not a new issue. It is simply that Darwinism

finally gave aggressive selfishness the moral justification that an

increasingly aggressively selfish society seemed to require.

But Darwin himself, very sensitive to the importance of human charity

and mutual concern in human society, was quite aware of this ethical

matter, and actually troubled by how many were choosing to read cruel

ethical justification into his theories.

1It is truly amazing the extent to which man can go in rationalizing about God and God's intentions.

At

the same time that German (and other) social philosophers were

seeing in the fast-changing dynamic of their days the fulfillment

of history through the rise through struggle of the tribal nation

(France, Germany, Italy, etc.), German expatriate philosopher (in exile

in London) Karl Marx (1818-1883) headed down an entirely different road in his

explanation as to where history was headed. He saw history

fulfilled not in the struggle among nations but instead in the struggle

among economic classes, principally between the owners of wealth and

the subject classes (proletariat)2 that produced that wealth for the

owners through their labors. Marx was so insistent on this matter

that he actually despised nationalism and all the discussion going on

about nationalist struggles, seeing that as a distraction leading

people away from the real struggle that lay before them, the industrial

class struggle that was about to unfold – and lead the world into its

final stage in history. At

the same time that German (and other) social philosophers were

seeing in the fast-changing dynamic of their days the fulfillment

of history through the rise through struggle of the tribal nation

(France, Germany, Italy, etc.), German expatriate philosopher (in exile

in London) Karl Marx (1818-1883) headed down an entirely different road in his

explanation as to where history was headed. He saw history

fulfilled not in the struggle among nations but instead in the struggle

among economic classes, principally between the owners of wealth and

the subject classes (proletariat)2 that produced that wealth for the

owners through their labors. Marx was so insistent on this matter

that he actually despised nationalism and all the discussion going on

about nationalist struggles, seeing that as a distraction leading

people away from the real struggle that lay before them, the industrial

class struggle that was about to unfold – and lead the world into its

final stage in history.

The Hegelian dialectic applied to Marx's economic theory

In 1848 Marx published his famous 30-page Communist Manifesto in the hope of capitalizing on the spirit of political rebellion that was rocking continental Europe at that time.

His Manifesto outlined history

as a series of quite Hegelian dialectical struggles over time between

those who legally owned the land, tools, machinery (what Marx summed up

as social property or the "means of production") that produced the

wealth that the people of society lived off of, and the proletariat

who, though they owned none of those means of production, labored

physically in using those means of production to bring forward the

wealth that society lived off of. Typically in history, in the

distribution of the wealth that a society jointly created for its

survival and prosperity, most all of that wealth went to the class of

property owners, with very little making its way to the hands of the

proletarian workers.

This would bring tremendous tension to society,

which eventually would turn into physical conflict because of this

social injustice. Again, in Hegelian (and eventually Darwinian)

dialectical fashion, such conflict or class struggle would then move

history forward to a new, and better social system, shaped by the way

the opposing classes synthesized their social positions into a new

social structure.

Continuing his analysis in a further work, Das Kapital,3

he carefully described the situation around him in Europe where the

feudal system, once dominated by landed aristocrats, had been

challenged by a new social class of industrial and financial

capitalists, thus creating the age of capitalism. But he also saw

how capitalism in turn had created its own opposing social force in the

form of the industrial workers (the industrial proletariat) whose

labors supported the capitalist system. And he predicted that

conditions were quickly rising that would cause the industrial

proletariat in its turn to rise up against the capitalist class, and –

through the necessary historical conflict or revolution – open the way

to a new social system.

Time was on the side of the worker, because capitalism by its very

nature is highly competitive even among the capitalists themselves –

each capitalist trying to eliminate his competitors in order to gain

greater control over the market. This way they could increase

their profits, even establish total or monopolistic control over the

whole process. But of course as they drove each other out of

business, they were inadvertently thinning out their capitalist social

ranks, making their numbers smaller at the same time that the ranks of

the proletarian were growing. Thus simply the calculus of the few

against the many meant that the days of capitalism were numbered.

At that point (which supposedly was now upon them) all the proletariat

had to do was rise up and seize control of the means of production,

thus destroying the power of the capitalist class, and the public

government that had been protecting the capitalists. Thus in

rising up against their capitalist oppressors, they had "nothing to

lose but their chains."

A property-less, state-less, utopia

But, according to Marx, the resultant social system would be different,

it would be utopia itself. There would be no further class of

dominators or exploiters of the proletariat, because the new society

would be made up solely of industrial workers. There would be no

other class of people in the new society but this one single industrial

class. Everyone would now live as social equals – as comrades,

rather than as a two-class system of gentlemen lording it over a

servant class. Being equals, all would live communally, as in all land,

tools and machines being owned jointly by all – and by nobody in

particular.

Consequently, there would be no need for the political enforcing agency

of the state or government. It would simply wither away, because

the sole purpose of the state was to protect the interests of the

privileged class of property owners, whether feudal, capitalist or

whatever. In the communist society there would be no personal

property, thus no state. Something like a Rousseauian bliss would

then hold this happy world together.

Communism as the last stage of history

Also, the new society would end the long historical dialectic of a

ruling class and a proletariat class finding themselves once again in

conflict. With no division under communism between a propertied

class and a proletarian class, there would be no cause for social

conflict, no tension, no stress, only blissful peace. Thus this

last historical revolution would bring history to a completion, the

kind of millennialist completion that everyone was expecting because of

the unprecedented progress they had been observing coming forth at

mind-boggling speed. All history was supposedly about to fulfill

itself, and Marx was showing how that was to be accomplished.

All very scientific

This was all pretty powerful stuff. And it appealed to the

interests not only of European industrial workers, but also to

intellectual Progressivists – not only in Europe but also in

America. Marx's theories seemed to be irrefutable because they

were built on hard fact. Unlike the philosophical speculations of

social philosophers before him, but quite like Darwin, Marx had thrown

a lot of data into his analysis, supposedly hard economic data, thus

qualifying his theory as "scientific socialism," making him – and those

who followed his lead – "scientific socialists."

Marx's militant atheism

As all materialists or mechanists, Marx had no need of the concept of

God, or some divine hand driving forward the economic process he had

outlined. It all worked – similar to Darwin's theories – entirely

mechanically. Marx personally was an atheist. In fact he

was quite opposed to the Christian religion, or any religion that saw

history shaped and judged by a Supreme Being. As for

Christianity, he saw the religion simply as a cruel psychological tool

used by Europe's ruling classes (most lately the capitalists) that

savagely exploited their own servants or workers, by excusing their

horrible treatment of the workers under the promise that if the

oppressed workers all cooperated with the system and behaved themselves

(not rebel against their oppressors) they would be rewarded in the next

life with heaven. To Marx, such religious theory was only a form

of spiritual opium given to the masses to keep them docile.

The spread of Marxism among Europe's intellectuals

Meanwhile, as Europe headed into the Twentieth Century, clearly a

growing number of social and political philosophers were convinced

that, through some kind of Darwinian process, Western civilization

(and, via the West, also world civilization as well) was moving into a

bright future in which utopian existence for all – even (and

especially) the unwashed masses – seemed to loom into view.

Society just needed some adjustments here and there – led of course by

these political philosophers or social scientists – in order to bring

this process to completion. "Historical progress" and "democracy"

– however conceived specifically (and the variation was indeed huge)

were the bywords, the slogans, the shibboleths, of those who supposed

that they possessed special intellectual insights into where the world

was headed.

Within that group of Western social reformers was a large group of

Marxist ideologues and political activists – forming the Social

Democratic Party in a number of European countries – whose expectations

were that Marx's Communist revolution would soon break out across

Europe. This supposedly would occur naturally first in a society

experiencing the most advanced state of capitalism, probably Great

Britain or Germany. After all, Marx's scientific socialism would

not work except under the historical circumstances he had so carefully

described. Every stage of historical development had to be

completed before history would be ready to move on to the next step or

phase in its development. The dialectical method demanded that

kind of historical precision.

2A

term drawn from Roman times in reference to the members of the Roman

working class who held little or no property and thus few or no

political rights.

3Marx

was a prolific writer ... who found getting his work published

difficult because of the opposition it always faced from the

authorities. Of his multi-volume Das Kapital, the first volume

would be published in 1867. Additional volumes would be published

by his friend Friedrich Engels after Marx's death in 1883: volume

two in 1885 and volume three in 1894.

Go on to the next section: The West Since 1850: An Introduction

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | | | | | |

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham

The assault on Christian morality

The assault on Christian morality

Bentham's Utilitarianism.

Bentham's Utilitarianism. The

Frenchman Auguste Comte (1798-1857) reacted to the sometimes wild

speculation of French rationalists, who during the previous century had

built their philosophical theories on "reasonable" propositions –

rather than on the observation of actual phenomena. In short, he

introduced British empiricism to French or continental philosophy,

terming his approach "positivism."

The

Frenchman Auguste Comte (1798-1857) reacted to the sometimes wild

speculation of French rationalists, who during the previous century had

built their philosophical theories on "reasonable" propositions –

rather than on the observation of actual phenomena. In short, he

introduced British empiricism to French or continental philosophy,

terming his approach "positivism." Mill

(1806-1873) was an amazing child prodigy, reading classic Greek

literature (from Aesop to Plato) by age 8, then a full array of Latin

and Greek works by age 10 ... plus history, math, physics and

astronomy. In all of this, he was carefully "home schooled" –

pruned and protected in his infancy and youth by his father, James Mill

– in order that the son would be "associated" only with the sharpest

minds (his father's and that of the family friend Jeremy Bentham) ...

and not with lower social orders of his own age ... a key part of the

educational philosophy of the British "Positivist" movement. His

father's goal was to grow his son into "a bright light of Utilitarian

philosophy that might light the world." In part the father

succeeded, though at a deeply heavy emotional and spiritual cost to the

son.

Mill

(1806-1873) was an amazing child prodigy, reading classic Greek

literature (from Aesop to Plato) by age 8, then a full array of Latin

and Greek works by age 10 ... plus history, math, physics and

astronomy. In all of this, he was carefully "home schooled" –

pruned and protected in his infancy and youth by his father, James Mill

– in order that the son would be "associated" only with the sharpest

minds (his father's and that of the family friend Jeremy Bentham) ...

and not with lower social orders of his own age ... a key part of the

educational philosophy of the British "Positivist" movement. His

father's goal was to grow his son into "a bright light of Utilitarian

philosophy that might light the world." In part the father

succeeded, though at a deeply heavy emotional and spiritual cost to the

son. When

in 1859 Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his book,

When

in 1859 Charles Darwin (1809-1882) published his book,

At

the same time that German (and other) social philosophers were

seeing in the fast-changing dynamic of their days the fulfillment

of history through the rise through struggle of the tribal nation

(France, Germany, Italy, etc.), German expatriate philosopher (in exile

in London) Karl Marx (1818-1883) headed down an entirely different road in his

explanation as to where history was headed. He saw history

fulfilled not in the struggle among nations but instead in the struggle

among economic classes, principally between the owners of wealth and

the subject classes (proletariat)

At

the same time that German (and other) social philosophers were

seeing in the fast-changing dynamic of their days the fulfillment

of history through the rise through struggle of the tribal nation

(France, Germany, Italy, etc.), German expatriate philosopher (in exile

in London) Karl Marx (1818-1883) headed down an entirely different road in his

explanation as to where history was headed. He saw history

fulfilled not in the struggle among nations but instead in the struggle

among economic classes, principally between the owners of wealth and

the subject classes (proletariat)