7. THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES

THE CRUSADES

1095 to the Late 1200s

CONTENTS

The First Crusade (1095-1098) The First Crusade (1095-1098)

Efforts to consolidate the victory Efforts to consolidate the victory

Mixed success Mixed success

The textual material on the page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 229-234.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

1071 Seljuk Turks defeat the Byzantine Army at the Battle of Manzikert, cutting off access by

Christian pilgrims to the Holy Lands

1095 Pope Urban II supports Byzantine Emperor Alexios Komnnos's request for help in warding

off the

Seljuk Turk threat ... declaring a "crusade" to help the Byzantine

Empire

1096 Peter the Hermit, with as many as 100,000 commoner men, women and even children,

head off on such a crusade (slaughtering Jews along the way) ... which

ends in

disaster at the Battle of Nicaea

Meanwhile a number of princes organize their own crusading groups ...

and the "First

Crusade" (1096-1099) brings the Holy Lands under crusader

control;

Then most of the princely crusaders go home ... though some Normans

establish their

own personal rule in the cities taken from the Muslims

1118 An order of military monks (the Knights Templar) is founded in Jerusalem ... soon

becoming very powerful and very wealthy

1124 The crusaders add Tyre to their holdings of Antioch, Tripoli, Jerusalem, and Edessa

1144 But Edessa falls to the Muslim governor of Mosul, Zangi

1147 Pope Eugene III and Bernard of Clairvaux call the Second Crusade (1147-1150) to stop a

Muslim

revival

Numerous European kings now "take up the cross" (join the

crusade)

Also

Christian warriors take Lisbon from the Muslims as part of the 2nd

Crusade

1150 The Second Crusade ends up in failure ... but awakens European monarchs to the glory

of Muslim culture ... stirring a new materialistic cultural spirit in

Europe

1171 Sunni Muslim warrior Saladin seizes control of Egypt (taken from the Fatamid Muslims)

1182 Saladin takes control of Syria (taken from the Crusaders)

1187 Saladin takes similar control of Palestine ... including, most importantly, Jerusalem

1191 Crusaders are able to take the strongly fortified city of Acre ... and (along with some other

such

fortified positions) are able to hold on to those fortresses for

another century

But otherwise, for all practical purposes, the crusading is done

THE FIRST

CRUSADE (1095-1098) |

|

The call to crusade

It was actually an event in the year 1095 that was to signal the beginning

of a great material (especially military) rise of Western Europe that

would bring it to roughly total world domination eight centuries

later.

While new social-cultural stirrings were taking place in the

European West, Islamic power was undergoing a period of decline in the

East. This became an opportunity for Europeans to redirect some

of these contentious instincts away from West Europe itself. It

gave free-booting princes the promise of plunder – and the popes a way

of getting a lot of these same princes out from under them so that they

could continue in their restructuring of the church around Roman rule.

It was also a euphoric time. Christians in the West were very

self aware of their own growing power – and were desirous of putting it

to good use. In particular they were easily stirred by the idea

of retaking from the infidel Muslims the most holy sites of all

Christendom: Jerusalem and Palestine.

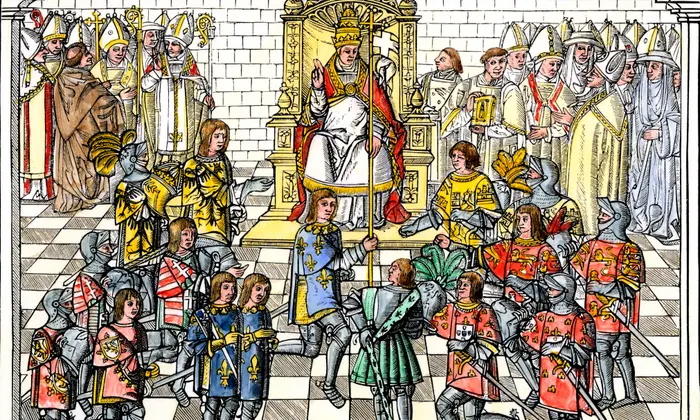

The Council of Clermont (1095)

There were a number of factors that came together in 1095 to cause Pope

Urban to call for a great crusade to liberate Jerusalem and the

surrounding Holy Land. Most directly was the appeal issued during the

Council of Clermont held that year by the visiting Byzantine emperor

(1081-1118) Alexius Comnenus. He asked the Pope and other nobles who

were present at this Council to send aid to the East to deliver the

Holy Land from the grip of the Seljuk Turks. Since the military defeat

of the Byzantine army by these Turks at the Battle of Manzikert in

1071, these Muslim Seljuk Turks had seized Antioch, had pushed deeply

into Asia Minor, and had cut off or badly disrupted the important paths

of Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

This came at a time when the population of Europe was expanding

rapidly, not only among the common peasantry but also among the

nobility, whose third and fourth sons were promised no inheritance or

income – outside of what they personally could gain through battle or

military service to another, wealthier noble. It was also a time of

pilgrimage, enabled by more stable political conditions in Europe, and

favored by the Christian as a means of receiving special grace or favor

in the reducing the penalty of one's sins. Also, Pope Urban made it

very clear at the Council that if the French knights were to devote

their energies to fighting the Turkish Muslim infidels rather than each

other, God would be greatly pleased. In fact, God willed it (Deus

vult). And thus the Pope declared a full indulgence (forgiveness of

sins) for those who took up the call to this "crusade."

So it was that the idea of a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, especially to

free Christ's lands from the infidel Muslim, seemed to be a highly

rewarding proposition to many of Europe's young, devout adventurers.

The result was an enthusiastic response which hugely exceeded the

expectations of both the Roman Pope and the Byzantine Emperor.

|

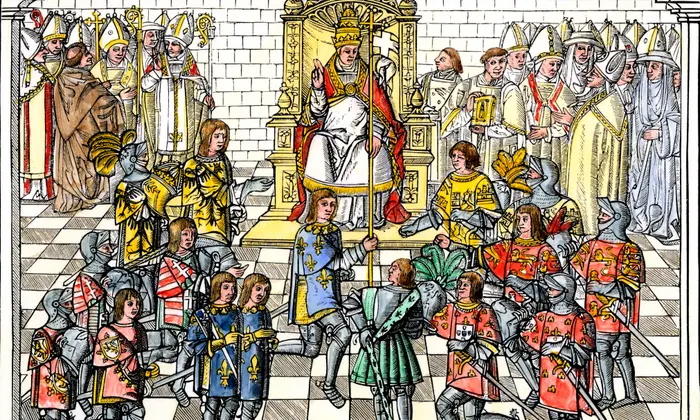

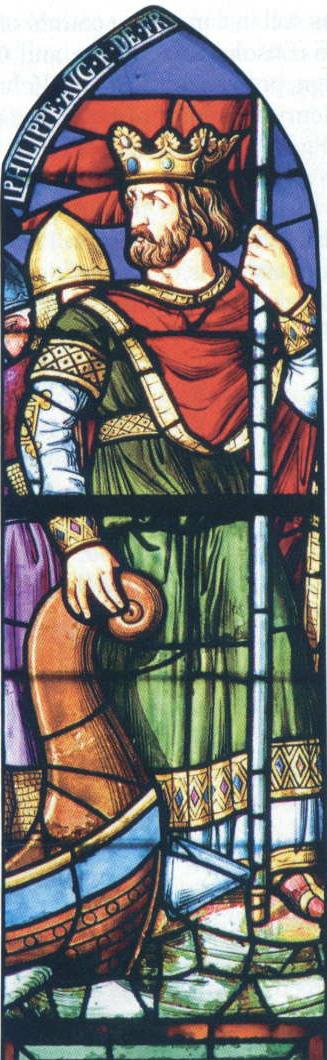

Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont (1095) calling for a crusade

against the Muslims ruling the Eastern Holy Lands

|

The First Crusade (1096-1099)

Planning and organizing such a major undertaking fell to a number of

individuals, mostly European noblemen of fairly high rank (kings,

however, did not participate in this first crusade).

An exception

was Peter the Hermit, who organized a huge band of common soldiers and

peasants, and marched them through southeastern Europe to

Constantinople. Rather than await the rest of the crusader force,

Peter's soldiers insisted on pushing on ahead toward their goal of

Jerusalem – so confident were they that God was going to bless their

rather unruly undertaking with glorious victory. But instead of

victory, they walked into a Turkish ambush at Cibotus (August 1096) and

were annihilated.

There were other rather spontaneous massings of commoner crusaders, but

most of those failed even to reach Constantinople. A much more

organized undertaking originating in the French-German borderlands was

led by Duke Godfrey of Bouillon and his brothers Baldwin and Eustice

and their cousin Baldwin of Le Bourg. Another group, mostly

Norman in character, was organized in Southern Italy by Bohemond, son

of the notorious Norman raider Robert Guiscard. Another largely

Norman group was led by Robert of Flanders, his cousin Robert of

Normandy, Stephen of Blois and Tancred, nephew of Bohemond. A

fourth group from southern France was led by Count Raymond of St.

Gilles and Bishop Adhemar – who together had been commissioned by the

Pope to be the overall leaders of the crusade. All of these

French speaking noblemen would set an indelible mark on the crusading

tradition, in that the crusaders' land holdings in the Holy Lands would

eventually become known as "Frankish" domains.

With about 4,000 knights and 25,000 foot-soldiers they left

Constantinople for the Holy Lands in May of 1097. With the

assistance of Greek warriors, they began to throw back the Turks that

came out to meet them as they advanced through Asia Minor. By

October they reached Antioch. (Baldwin broke company with the

crusaders to join the Armenians and take command of the all important

city of Edessa in eastern Syria) Not until next June did their

siege of Antioch finally bring the collapse of the city, as Bohemond

was finally able to breach the walls and lead his troops – to a

massacre of the Muslim inhabitants of the city. But the Antioch

citadel held out – though a relief force of Muslims was thrown back by

the crusaders. At the end of the month the Muslim defenders

surrendered the Antioch citadel under a promise of safe conduct if they

left the city. So the city was delivered into the hands of

Bohemond. But the victory was spoiled by an epidemic that broke

out among the crusaders, taking the life of Bishop Adhemar.

Early the following year (1098) the other crusader leaders and their

armies set out for Jerusalem (accompanied by the fiery preacher, Peter

the Hermit). Here they encountered not the Seljuk Turks (Sunni

Muslims) but the Fatimids (Shi'ite Muslims) from Egypt, who had

recently seized Jerusalem from the Turks. Despite the crusaders'

greatly reduced numbers (about half of what they had left

Constantinople with) they were able to breach the walls of Jerusalem in

mid-July – and proceeded to massacre the city's Muslim and Jewish

inhabitants – despite Tancred's efforts to hold the crusaders to a

promise of safe conduct he had given the city's leaders.2

2The

sheer barbarity of the crusaders shook the Muslim sense of religious

toleration of the Christian communities in their midst ... and

eventually the word "crusader" would become for the Muslim a term of

sheer ugliness and spite, representing in the mind of the Muslim the

lurking danger of barbarity in the Christian heart.

EFFORTS TO

CONSOLIDATE THE VICTORY |

Soon

thereafter most of the crusaders, having completed their "pilgrimage,"

departed for home, including the crusade's leader, Raymond.

Godfrey was then elected to serve as Jerusalem's new ruler. But

Godfrey's death two years later brought his brother Baldwin from Edessa

to take the position, now termed "king" of Jerusalem (he turned Edessa

over to his cousin Baldwin of Le Bourg).

Within the next ten years, aided in part by more crusaders coming from

Europe, Baldwin was able to extend the crusader holdings up and down

the Eastern Mediterranean coast (except Ascalon and Tyre). Then

in 1109 a fourth crusader state, Tripoli, was added to the crusader

states of Edessa, Antioch and Jerusalem. Tripoli was led by a

descendant of Raymond of St. Gilles (who had died in 1105). With

the acquisition of Tyre in 1024, this would be the greatest extent of

the crusader holdings in the Holy Land.3

Whereas the strong competition between the Sunni Turks to the North and

the Shi'ite Fatimids to the South allowed the crusaders to use

diplomacy to fend off Muslim threats from these two directions, a new

challenge arose from the East in the 1130s from the Muslim governor of

Mosul, Zangi. Improved diplomatic relations with the Muslims of

Damascus allowed the next generation of crusaders (who were quickly

adapting themselves to the political style of the surround Muslim

world) to prevent Zangi from achieving a strategic advance against

nearby Damascus. But the crusaders were unable to stop his

assault on Edessa, which fell to Zangi in 1144. This was huge

loss for the crusaders – and a shock to the Christians of Western

Europe when news of the loss reached them.

Meanwhile a similar crusade was undertaken in Spain and Portugal

against the Umayyads, taking a number of key cities (importantly,

Lisbon and numerous Spanish cties) also around the mid-1100s.

3The promise of the crusaders to restore to the Byzantine emperor land taken from the Muslims was completely ignored.

Of

course the Crusaders were not finished ... and fought back, recovering

some of the lost territory. Needless to say, there would be

little peace in the land between the Crusader Kingdoms and the Muslim

principalities. Thus more crusades were commissioned by future

popes, involving now German and French kings and even the Holy Roman

(Western) Emperor.

The crusaders fared poorly in their efforts to expand their conquest to

Fatimid Egypt, thanks largely to the military skill of Saladin, a Sunni

Kurd serving as vizier to the Shi’ite caliph al-Adid. With

al-Adid’s death in 1171 Saladin took personal control of Egypt,

submitted his territory to Sunni Abbasid authority (stirring Fatimid

revolts, which he crushed) ... and then took on the crusader states,

regaining control of Syria for Islam in 1182 and Palestine in 1187.

The crusaders, however, were able to take the strongly fortified city

of Acre in 1191 and hold that position – along with similar fortresses

in Palestine – for another century. But they would actually

exercise little control beyond the walls of those fortresses.

Of course further efforts (additional crusades) were made to restore

the lost crusader kingdoms, engaging now even the royalty of

Europe. But the efforts came to little ... except to introduce

European courts to the wealth and splendor of the Muslim courts, which

now became something of cultural models to the primitive Europeans.

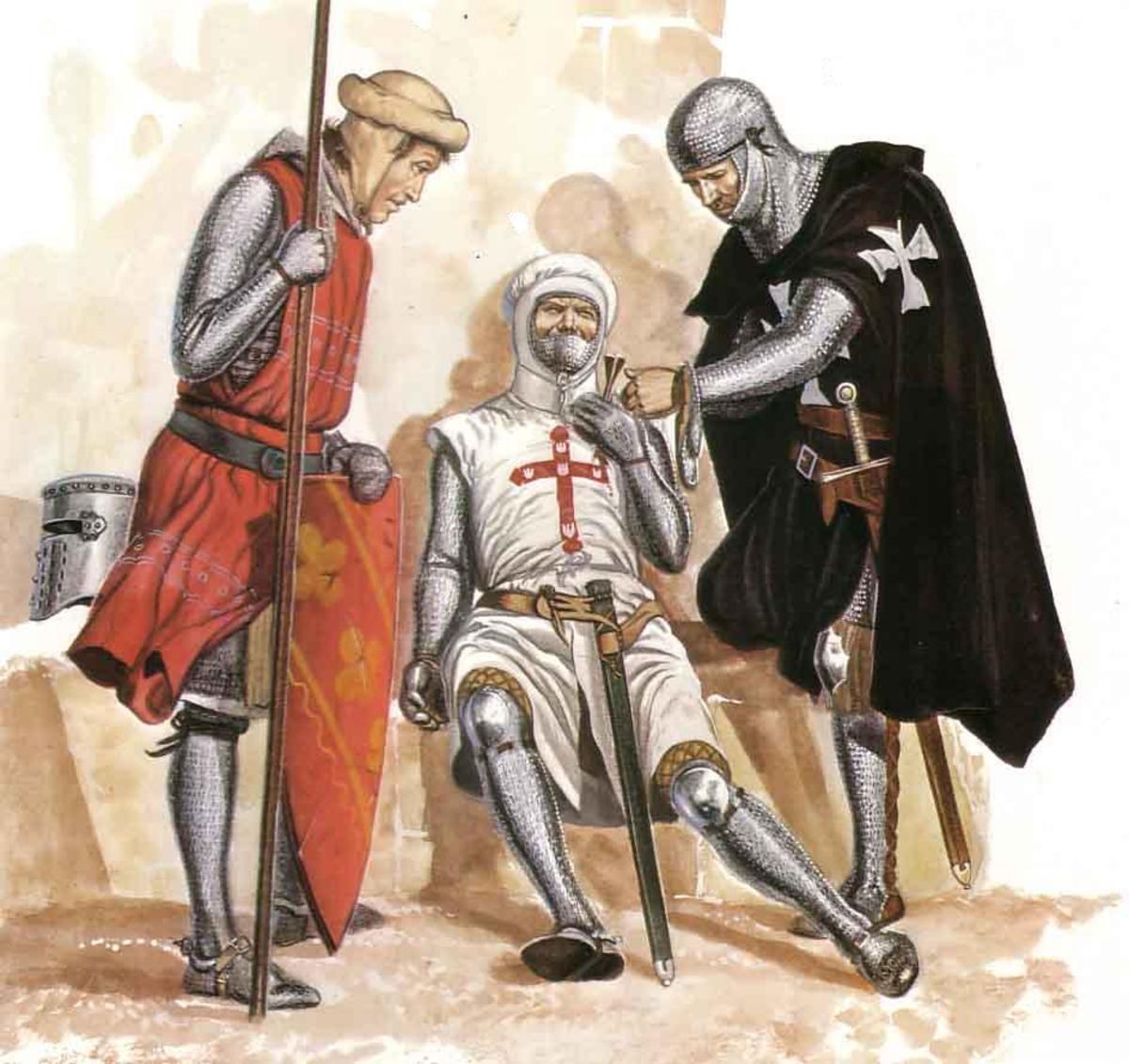

The crusading monks

Interestingly, the crusades also brought the creation of

religious-military orders (such as the Knights Templar and the Knights

Hospitaller) ... something like fighting monks, or at least warriors

who had taken a solemn vow of a life of service to the cause.

These military-priest orders would become wealthy and powerful in their

own right ... so much so that they drew the ire and eventually

persecution of a number of suspicious or envious European kings and

dukes.

The Knights Templar, founded in 1118 in Jerusalem, was a holy order of

knights (soon ordained even by Pope Honorius II in 1128), involved not

only in fighting the Muslim "infidel" in the Holy Land (only about 10%

of their order was actually engaged this way) but in collecting monies

for various charities. They became so skilled in this latter

venture, developing sophisticated banking techniques and placing

themselves strategically all across Christendom (Europe plus the

crusader holdings in the Middle East) that the Knights Templar order

became vastly rich.

This then began to stir the envy and fear of Europe's various dukes and

princes … who became increasingly resentful of the Templars.

Finally in 1307, using the secrecy by which they operated as his

excuse, French King Philip IV (deeply in debt to the Templars) had the

leaders of this order arrested, tortured (seeking to get "proper"

confessions out of them), and burned at the stake. Then five

years later he pressured Pope Clement V to officially disband the order.

Surviving the realm of European politics better than the Templars was

the Order of the Knights Hospitaller, formed actually a bit earlier in

Jerusalem – even before the first of the crusades – from the

foundations of a Benedictine hospital located in Jerusalem … by monks

who had committed themselves to taking care of the sick and poor who

came to Jerusalem as pilgrims. Then with the conquest of

Jerusalem in 1099 by the crusaders, the monks were joined by various

knights in forming a new order (also chartered by the pope), the

Kinghts Hospitaller, dedicated to defending and caring for the

Christian community in the Holy Land.

The order was ultimately forced to move to the island of Rhodes when Muslims first retook the Holy Lands in the late 1100s.

But the order continued to survive as the ruling authority in Rhodes

and then later at Malta … then eventually in Sicily as a vassal state

under Spanish authority. The Hospitallers would not draw the

resentment of Europe's monarchs … and would continue to serve Europe

charitably. However, the split in the Church that occurred

during the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s would also divide the

order – portions of which still survive down to today.

The urban Republic of Venice gets in on the act

Included (from the 1120s onward) in this great crusading venture were

also soldiers and sailors from the rising city-state (or Republic) of

Venice, strategically located at the top of the northeastern coast of

Italy. This just happened to be the best jumping off point for

central Europeans to reach the Holy Lands by water rather than the long

and hazardous overland journey through the unfriendly Balkans and the

wary Byzantine lands. It also happened to be well protected

by the fact that Venice was actually a maze of offshore islands,

virtually impossible to reach by a land army ... and well protected by

a massive navy.

The ongoing crusading effort

Times of truce between Christians and Muslims would occur ... followed

by the resumption of fighting, frequently as a result of a call of a

pope to yet another crusade (4th, 5th, 6th) ... on into the mid

and late 1200s.

Even the Byzantines got caught on the wrong end

of the crusades, especially the 4th (1202-1204) which seems to have

been waged only against the fellow-Christian Byzantine Greeks under the

orders of the Venetian authorities for whom the sacking of

Constantinople was the price exacted on the crusaders in order to have

Venice's ships then take them on to the Holy Lands (they never made it

there ... but did cripple Byzantine power greatly.

|

The Siege of Acre (Third Crusade) 1187-1191

The crusaders bring Acre to surrender when a Muslim relieving force

under Saladin fails to drive off the crusaders

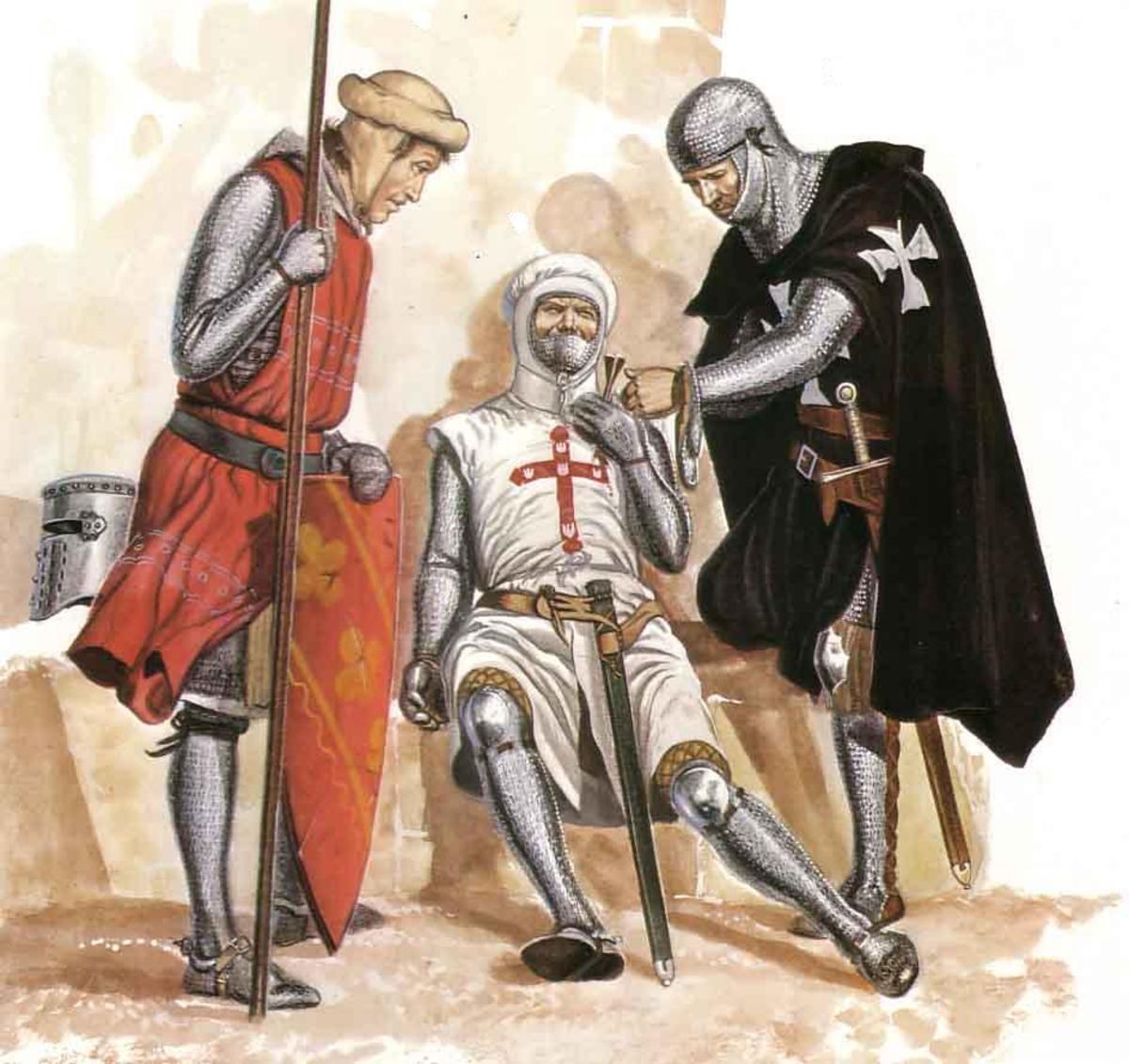

Knights Templar

Knights Hospitallers taking care of fellow crusaders

A knight Hospitaller caring for a wounded fellow crusader

Knights Hospitaller could also fight

Knights Hospitaller fighting Muslim troops in Jerusalem

Krak des Chevaliers - Fortress of the Knights Hospitallers in

Syria

Built by the Knights

Hospitallers beginning in 1140

and held by them until the castle fell to the

Mamluks in 1271

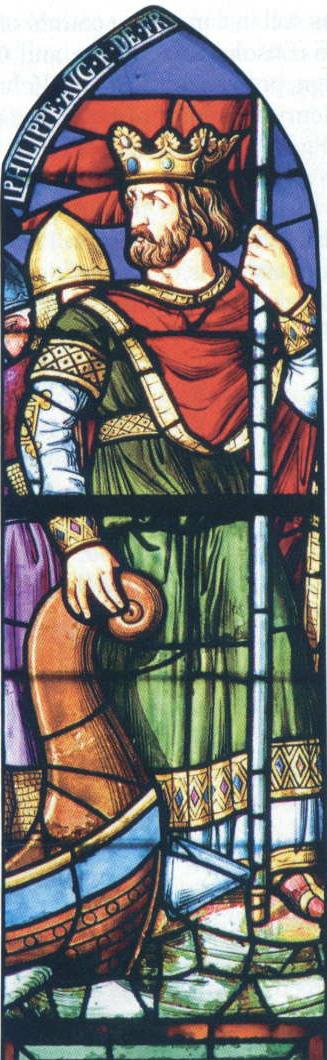

King Philip II Augustus of

France fighting Richard

(Plantagenet) the

Lionhearted

(In France, Richard was merely the Duke of Normandy ... but in England,

the country's king) - 1198

Philip II Augustus

Richard the Lionheart

Go on to the next section: Growing Urban Power

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

The First Crusade (1095-1098)

The First Crusade (1095-1098)

Efforts to consolidate the victory

Efforts to consolidate the victory