7. THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES

THE CLOSE OF THE MIDDLE AGES

Mid-1300s

CONTENTS

Marco Polo Marco Polo

The "Babylonian Captivity" of the popes The "Babylonian Captivity" of the popes

in France (1309-1377)

The Scots secure independence from The Scots secure independence from

England

The First Phase (1337-1360) of the The First Phase (1337-1360) of the

"Hundred Years' War"

The "Black Death" (1348-1351) The "Black Death" (1348-1351)

The rising secular spirit in urban Europe The rising secular spirit in urban Europe

... and rural serfdom

The rising threat in the East of the The rising threat in the East of the

Ottoman Turks

The Papal Schism closes out the Middle The Papal Schism closes out the Middle

Ages (1377-1418)

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 267-274.

|

Marco Polo's amazing discovery of another world to the East

Around the year 1300, Westerners were very surprised to learn from an account, The Travels of Marco Polo,

of a world in the Far East largely unknown to Westerners … in

particular, the very advanced civilization of China. Marco Polo's

tradesmen father and uncle had first made the journey east from their

home in Venice in the 1260s, meeting Chinese emperor Kublai Khan in the

process. When then in 1271 they returned to China at the

emperor's request (and Pope Gregory X's support), they had Marco with

them – the young man impressing the emperor so much that he had him

remain in China to serve as an imperial emissary. Marco thus was

sent on many diplomatic missions in and around the Chinese

Empire. Consequently, over the next 17 years he became quite

familiar with China and its ways. Then he and his father and

uncle had the additional opportunity to explore the neighboring

societies of Vietnam, Burma, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka and Persia …

before returning to Venice (in 1295) after 24 years away from their

home.

Upon their arrival back in Venice, Marco found himself involved in a

very vicious trade war going on at the time with Genoa … and got

captured and imprisoned in the process. But this did give him the

opportunity to spend that time dictating the account of his travels to

his cellmate. He was finally released in 1299 and returned

to a very palatial home – thanks to the wealth he and his family had

acquired in Eastern gems.

Very importantly, his depiction of a highly civilized China – and the

Far East in general – awakened a Western society already highly stirred

by a rising curiosity about the surrounding world … and all of its

fantastic material offerings. This would merely add to the

dynamic that was taking Europe out of its humbler Christian ways … and

ever-deeper into the world of material wealth and power.

|

THE "BABYLONIAN

CAPTIVITY" OF THE POPES IN FRANCE |

We

have seen how clearly the papal office of the Bishop of Rome had long

been the center of social-cultural politics – even military

politics. During the crusades European kings had served

essentially as military commanders for Christian armies understood to

be operating under the authority of the Pope. Only the crusading

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II acted independently of the Pope (for

which he was excommunicated not once but twice!).

With the close of the crusades in the late 1200s this dynamic

changed. Ambitious kings and princes (and even powerful Italian

families) began to operate increasingly independently in their own

territories – in disregard of the presumed unity of Christendom

represented by the Church and its papal leadership. Popes found

themselves in opposition to many of these new authorities – a situation

which politicized heavily the papal office. Excommunications were

imposed – and then lifted – against kings and ministers of state when

the interests of the papacy and these rising authorities either clashed

or conformed.

A number of diplomatic crises plus local circumstances in Rome upset

greatly the political standing of the Roman papacy: infighting between

two powerful Roman families (the Orsini and Colonna) over control of

the papacy, the increasing influence of French clergy in the Papal

Curia, the effort of French King Philip IV to have Pope Boniface

arrested and brought to France for "heresy" in 1303 (but Boniface died

soon after this assault) and finally the election of a French pope

(Clement V) in 1305. This resulted in the decision of the Curia that

year to move the papal office to France – eventually in 1309 to the

city of Avignon in southern France. Here supposedly the pope

would be under the French king's "protection." This begins the

period of the papacy often termed the "Babylonian Captivity"!

Pope Clement was clearly a tool of French king Philip IV and agreed to

the destruction of the Knights Templars, a very wealthy crusading order

whose land and financial assets in France Philip IV coveted

deeply. Clement also became deeply engaged in battles with the

growing commercial empire of Venice … and led a brutal crusade at the

beginning of the 1300s against some of the "Dulcinian heretics" whose

Franciscan-inspired spirituality was deemed offensive to the church.

Then popes after Clement integrated the papacy more and more with the

interests of the French monarchy. Thus as the 1300s rolled along

the popes gave more the appearance of being mere participants or even

pawns in the political struggles of Europe – than they did of grand

leaders of Europe's huge religious community.

Then when in 1377 the pope was finally returned to Rome, several

"popes" competed for official recognition as the supreme head of the

Roman Church. This continued to worsen the spiritual dignity of the

papacy, whose image dropped decidedly in the eyes of the faithful – and

remained at a low for quite some time.

|

The Papal Palace at

Avignon

THE SCOTS SECURE INDEPENDENCE FROM ENGLAND |

Edward

II of England (r. 1307-1327) proved inept (and corrupt) … losing

the Battle of Bannockburn (1314) to Scottish leader Robert the Bruce –

and thus securing Scotland's independence from England, with Robert now

serving as Scottish king … confirmed in 1324 by Pope John XXII's decree

and further secured with a new Scottish alliance with France in

1327.

By this time the English were so tired of Edward that they (aided by

Edward's wife Isabella … who was also French King Philip IV's daughter)

forced him to abdicate that same year in favor of his son Edward

III. He was subsequently murdered … probably under the orders of

Isabella.

|

THE FIRST PHASE (1377-1360) OF THE "HUNDRED YEARS' WAR" |

The

"Hundred Years' War" – actually a series of three wars, interspersed

with times of truce – was basically an ongoing battle between the

Plantagenet and Valois families over the question of the right to

govern France. It is often identified as a battle between the

English and the French, which is what it eventually became as

Plantagenet troops and support took on an increasingly English

nationalist character, with the Valois increasingly appearing to be the

more "French" of the two contenders.

The Plantagenet family held the peculiar position of being both

vassals or barons under the kings of France, yet – since the Norman

victory over the Saxons in England in 1066 – at the same time kings by

their own right in England. The two families were also connected

by lineage or mutual descent from the Capetian royal family ruling

France – starting up a bitter contest between the two families when the

last king of the Capetian line ruling France died without any direct

heirs. At first the Plantagenets (led by English King

Edward III) Edward III attempted to assert his right to the French

throne … he being the nearest male in line to that throne through his

mother Isabella, the only sister of the just deceased French King

Charles IV. But ultimately he acknowledged the Valois claim to

the French throne by way of his cousin, Philip VI. But in 1337,

Edward decided to press his own claim to the French throne when Philip

moved to support the Scottish in their long-standing war with the

English. Thus began the first phase of a contest that would span

five generations of these two families.

Edward III (1327-1377)

offered England another long period of rule … though he was deeply

challenged during much of that time by that "Hundred Years' War.

Initially, during the "First Phase" (1337-1360) of the war, it appeared

that Edward would succeed in his bid for the French throne – as the

fortunes of war favored his forces greatly in battle after

battle. His son, Prince Edward "The Black Prince," was given

command of his Plantagenet or "English" forces … and defeated the

Valois or "French" forces soundly at Crécy (1346) and Poitiers

(1356). And the younger Edward's path to securing his position as

Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony in the South of France involved him in

many other successful (and highly destructive) battles with the Valois

forces.

But the intervention of the Great Plague (or "Black Death") hit England

– as all of Europe – very hard … killing much of the English

momentum. But the war then resumed as England recovered …

resulting ultimately in the capture by Prince Edward in 1356 of French

King John II … who, however, was merely held for ransom. But it

was a most humiliating defeat for the French.

Then in 1360 a strange hail storm killed over 1,000 of the English

troops as they were undertaking the siege of Chartres … on their way to

then seizing Paris. But the storm so devastated the English army

(the largest loss of life in the war so far) that King Edward was

forced to accept terms of peace with France. This would bring

this first phase of the Hundred Years' War to a close.

|

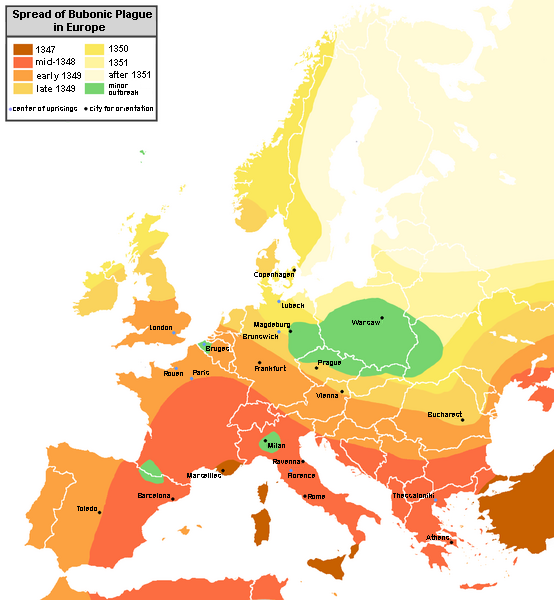

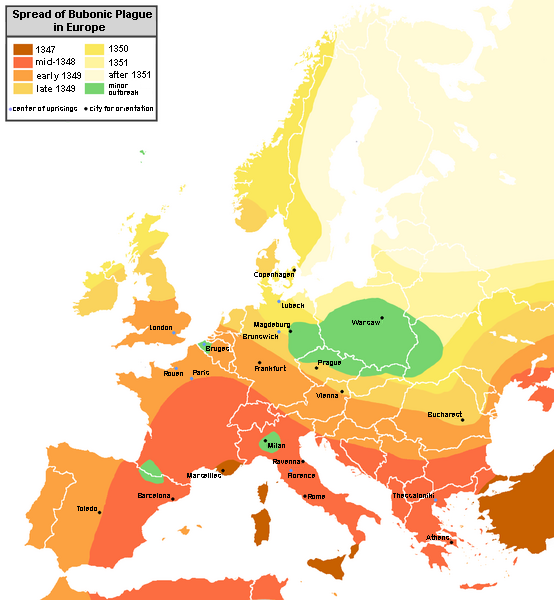

THE "BLACK

DEATH" (1348 to 1351) |

In

the mid-1300s the Black Death struck Europe – wiping out 25 million

people. It originated in Central Asia and made its way along the

silk route to Constantinople in early 1347. From there it was

brought to Sicily and Italy, spreading over Italy early the following

year, and from there quickly into France and southern England by the

summer of 1348. In Florence alone, it killed three-fourths of the

city's inhabitants. In England, in a 3-year period it wiped out

half of the population of 4 million people. After this a wave of

other epidemics swept a much-weakened Europe.1

Overall, the Black Death left Christian Europe shattered, economically,

socially, culturally … not to mention spiritually. Where was God

in all of this? Was he actually not the powerful God they had

been led to have full faith in? Or was he an angry God, angry at

the moral-political dissolution that had hit the Christian community …

especially at the level of its "Christian" leaders? What exactly

was one to make of this disastrous event?

The Church did not rebound well from the Black Death, having been able

to give neither explanation for nor relief from this mysterious

devastation. A lot of faith in the Christian cosmos was deeply

undercut by this tragedy. Worse, not able to account for the

cause of the tragedy, the Europeans’ frustration and wrath turned on

defenseless targets such as Jews, Gypsies, lepers and foreigners,

Europeans blaming them for having brought the disease. Whole

communities of European Jews were completely wiped out in the reaction.

Nonetheless Europe rebounded fairly quickly, though with a greatly depleted population.

1Waves

of attack by the plague would hit Europe again and again over the years

... though not with the severity of the 1350 Black Death ... though

very devastating and frustrating nonetheless. It would not be

until the 1600s that Europe would reach the populations size it had

before the Black Death.

The spread of the Bubonic

Plague in Europe

The spread of the Bubonic

Plague in Europe

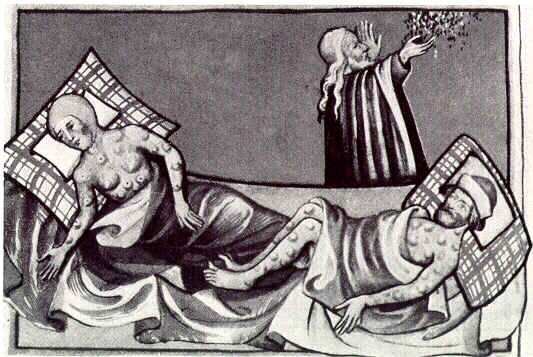

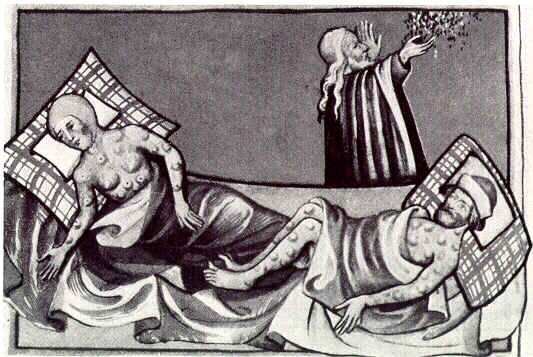

Illustration of bubonic

plague in the Taggenburg Bible

Monks, disfigured by

the plague, being blessed by a priest

From James Le Palmer, Omne

Bonum (London, 1360-1375)

THE RISING SECULAR SPIRIT IN URBAN EUROPE ... AND RURAL SERFDOM |

Urban optimism.

Indeed a secular spirit rising among the people – particularly those

living in the rapidly growing cities – was too strong to be long

intimidated by the calamities of the Black Death and the Babylonian

Captivity ... or the diminishing of sacred tradition caused by the

Papal Schism. As things actually turned out, many urban laborers

benefitted financially from the labor shortage caused by the Black

Death.

Indeed urban life tended to bounce back quickly in spirit ... and keep

moving forward, lured onward by a sense of better things lying ahead.

But rural serfdom (virtual slavery).

However, it must also be noted that in the feudal coountryside this

same labor shortage caused many feudal lords in fact to tighten up on

the ability of their peasants to shift around in the quest for better

conditions elsewhere.

In

England, efforts by landowners (including the church) to hold scarce

labor captive through a tightening of the laws permitting the peasants

to move on to new economic opportunities – instead gradually turning

the English free peasants into serfs – eventually produced a massive

uprising in East Central England known as the Peasants' Revolt

(1381). Although it was brutally suppressed, it left among the

commoners a legacy of discontent with the wealth of the landowners ...

and the church.

In Central and Eastern Europe the lords of the land now tended to lock

their vassals in place as rightless serfs ... whose social-political

status was now hardly different from that of a slave. |

THE RISING THREAT IN THE EAST OF THE OTTOMAN TURKS |

Osman I (1281-1326) founds the Ottoman Empire.

In 1281 a local Oghuz Turk took up his father’s position as bey

(governor) of a small beylic (Turkish state) in northwestern Anatolia

(modern-day Turkey) … very near the border of a weakening Byzantine

Empire. Choosing to take his aggressions out on the failing

Byzantine Empire rather than on his Turkish neighbors (the more usual

direction of Turkish military politics) he drew a large number of other

Turks to his cause – notably Ghazi warriors (volunteer militia)

abandoning what was by then a collapsing Seljuk empire – Osman building

up a very strong military in in the process. Thus he proceeded to

expand the boundaries of his own beylik … but also through diplomacy

and strategic marriages as well as by the engines of war. By 1299

he was ready to accept the title "Sultan of the Ghazis." Thus the

Ottoman Sultanate, the forerunner of the Ottoman Empire, was born (and

soon named after him).

Orhan and Murad I.

Osman’s son Orhan (1326-1362) and Orhan’s son Murad I (1362-1389)

continued the Ottoman expansion, Orhan taking Bursa with his Ghazi

troops, making it his new capital … very close to the Byzantine capital

at Constantinople. At this point the Byzantine power in Anatolia

was almost completely eradicated.

In taking power in 1362 Murad immediately conquered the city of

Adrianople, to the north of Constantinople, beginning the encirclement

of the Byzantine capital ... and the permanent move of the Ottoman

Sultanate onto the European continent. Murad turned this Balkan

city into his new capital in 1363 and renamed the city "Edirne."

He then began his expansion into neighboring Bulgarian and Serbian

lands, aided greatly by the internal divisions and infighting going on

within those two Christian societies … and by the pressures on the

Bulgarians coming from the Hungarians to the north and the Greeks

rising up in rebellion against the Serbs to the southwest. In

1387 his troops were able to seize from the Italian Venetian Empire the

strategic city of Thessaloniki sitting at the vital juncture of the

land of the Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks.

Finally in 1389 at the battle of Kosovo, Murad’s new army, now including Janissary troops,2

was able to crush the Serbian army (though the Ottoman forces

themselves were greatly devastated by the battle), weakening the Serbs

so much that they soon accepted vassalage within the growing Ottoman

domain ... though Murad himself lost his life in the battle.

Bayezid I (1389-1403).

Bayezid gathered a massive army – interestingly made up of a large

number of Serbian and Byzantine soldiers – to consolidate his hold on

the remaining independent Turkish beyliks to the south of the Anatolian

peninsula. Meanwhile (1389-1395) his troops were active to the

north in Bulgaria and Wallachia (today’s southern Romania) … although

the Wallachians were able to hold him in check. And in 1395 he

laid siege to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople … but was unable

to breach its thick walls or cut off its supplies by sea – although a

Christian relief force – another "crusade" … led by the King of Hungary

– was defeated at Nicopolis (1396).

Tamerlane - A Step backward for the Ottomans.

The Ottoman assault on Constantinople continued until 1402 … when the

Ottoman troops were called back to Anatolia to hold off the

ever-expanding central-Asian realm of Timur (or "Tamerlane") … who had

allied with the local Turkish beys that had proven resentful of

Bayezid’s domination of Anatolia. At the Battle of Ankara (1402)

Bayezid was captured … and died the following year in captivity.

For a brief period (ten years) it looked as if the Ottoman threat to

Europe had been dismissed. But that was not to be. In the

next century (and after) the Ottoman Turks would play a major role in

European affairs.

2The

Janissaries constituted something of a new personal guard, in effect

slave soldiers who had been taken from Christian homes at an early age

and trained as Muslim warriors totally dedicated in life and death to

the Ottoman sultan. They proved to be very fierce warriors … even in

taking on the Christian world they had originally been born to.

THE PAPAL SCHISM CLOSES OUT THE MIDDLE AGES (1377 to 1418) |

When

in 1377 Pope Gregory returned the papal court to Rome, he soon died ...

and the College of Cardinals elected a new pope, whom they quickly grew

to dislike, and thus elected another pope. But the first pope

refused to step down ... and now there were two popes.

European princes and kings soon lined themselves behind one or another

candidate, making the papal schism even more catastrophic to the status

of the Church. Eventually there would be even other candidates

(and their political supporters) to step forward to claim the papal

position ... before a compromise was finally achieved at the Council of

Constance (1414-1418).

But Christianity, as the spiritual underpinning of the old Christian community, by that time had lost ground badly.

|

Go on to the next section: The European Renaissance

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

Marco Polo

Marco Polo

The "Babylonian Captivity" of the popes

The "Babylonian Captivity" of the popes The Scots secure independence from

The Scots secure independence from The First Phase (1337-1360) of the

The First Phase (1337-1360) of the The rising secular spirit in urban Europe

The rising secular spirit in urban Europe The rising threat in the East of the

The rising threat in the East of the The Papal Schism closes out the Middle

The Papal Schism closes out the Middle