|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

1602 The Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) is chartered ... eventually taking on Portuguese

competitors ... and Portuguese strategic positions along the East-West

trade route

1603 Pro-Protestant James I Stuart becomes King of England (already king of Scotland)

1607 The English establish the Virginia colony at Jamestown

1608 Champlain establishes a French settlement at Quebec

Deeply persecuted Protestant Separatists, under John Robinson, leave

England for the

fellow-Protestant Netherlands

1609 The Dutch hire English seaman Henry Hudson to explore a path to the East via a river

route across North America ... ultimately discovering the "North" or

Hudson River

Johannes Kepler publishes his Astronomia nova ... broadening considerably the realm

of modern astronomy ... seeing a Godly order in all of creation

1610 "Good King" Henry VI is assassinated by a Dominican monk; his very young son (only 9)

becomes French king as Louis VIII ... his mother Marie de Medici in

fact ruling France

1611 Protestant king Gustavus Adolphus (1611-1632) turns Sweden into a great military power

1615 The papal Inquisition deems Galileo's heliocentrism (sun, not earth, as center of the

universe) to be contradictory to Biblical standards

1617 Louis XIII finally takes control of France ... Cardinal-Duke Richelieu being his key advisor

1618 The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) breaks out, involving Europe's continental powers

in periods of intense conflict over religion and political jurisdiction

1619 Slaves are brought to Virginia to work the tobacco fields

1620 Sir Francis Bacon's Novum Organum employs an empirical approach to social study

Some of Robinsons' Separatists leave Europe to find refuge as "Pilgrims" in America

1621 The Pilgrims establish a Plymouth plantation or colony at Massachusetts' Cape Cod

Philip IV of Spain (1621-1665) becomes king of a fast-declining Spain ... the decline

due in part to the huge expenses involved in fighting the Thirty Years'

War

The Dutch establish the Dutch West India Company (GWC) to explore and

settle the

North American coastal region ("New Netherland") lying between the

"North" (Hudson) and the "South" (Delaware) Rivers

1622 Count-Duke Olivares becomes Philip IV's Valido or counsellor (1622-1643) ... who pushes

Philip to involve himself exhaustingly in the various wars of the day

1625 James I dies; his pro-Catholic son Charles I becomes English-Scottish king (1625-1649)

He will at first (1625-1633) try to rule without Parliament

Hugo Grotius attempts, with his On the Law of War and Peace, to apply legal reasoning

as the path to peace ... greatly needed during the Thirty Year's War

1628 The Protestant fortress at La Rochelle is finally brought down ... completing Louis and

Richelieu's program of ending all local Huguenot authority in France

1630 Under John Winthrop's leadership, a flood of Puritans to England starts (1630-1642) ... some 20,000 of them

1632 Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems defends his heleocentrism ... and ridicules the papal and Jesuit position on the subject

1633 Charles I appoints conservative William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury ... who will

use the Star Chamber to persecute Puritan opponents

1636 Roger Williams is "invited" to establish his own "pure" colony at Providence

1637 René Descartes tries to lay mathematical foundations to all truths, social as well as physical in his Discourse on Method

1638 An argumentative Anne Hutchinson is forced to leave the Massachusetts colony

1640 Archbishop Laud is arrested by British Parliament

1642 Full civil war between Charles I and Parliament breaks out (1642-1649)

This restricts greatly the flow of Puritans to New England

1643 Philip's Spanish army suffers a huge defeat by the French at the Battle of Rocroi

But Louis XIII dies a few days earlier, leaving the throne to his son

(only 4!) Louis XIV

1644 Oliver Cromwell heads the Puritan Parliamentary army

1645 Archbishop Laud is executed on Parliament's orders (Jan)

Charles I's army is defeated by Parliament's heavily Puritan New Model

Army (Jun)

Charles escapes to Scotland, but (under payment) is sent back to England

1648 The Treaty of Westphalia finally ends the European Wars of Religion (Thirty Year's War) ... all signatories agreeing to let their own authorities determine

their society's religion

In

the East, a Ukranian uprising against Polish authority begins the

"Deluge" ... the

beginning of the destruction of the huge Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

1649 Charles I is beheaded; his son Charles II escapes to France

Parliament establishes the Puritan Commonwealth ... under Cromwell's

command

|

The Wars of Religion

It is usual to caption the first half of the 1600s as the time of an

almost endless series of “Wars of Religion.” Indeed, religion

played a part ... though it was not really religion that caused these

wars. Religion only justified these wars. What this

tumultuous period was all about was the realignment of political power

caused by the collapse of Christendom. The old moral order

overseen by the Pope and Holy Roman Emperor had definitely disappeared

... and there was a scramble of rising political figures bent on

securing for themselves a stronger position in the emerging status

quo. This really was therefore a war of rising states, both

monarchical (kings) and commercial (city-states). With the

collapse of old Christendom, there were no rules in the struggle and so

it became an all-out war of player against player. Therefore the

period properly ought to be termed the “War of the Post-Christendom

States”!

The Thirty Years' War

It

is also termed the period of the "Thirty-Years' War." Actually

wars among the rising European states had been going on rather

constantly over the previous century, though they tended to reach a

particularly devastating proportion in the period 1618 to 1648.

And the exhaustion experienced by all the players in this struggle

finally brought something of a more enduring truce (though by no means

end) to the inter-state conflicts. Indeed, it seemed to mark the

beginning of a new era in European politics (and European history).

The Treaty of Westphalia (1648) and the dawn of a new era

The peace treaty of 1648 would end up not being just another one of the

many truces that had provided only a temporary pause in the

fights. Westphalia marked a deep resolve among the contenders to

accept things as they had come to be politically by 1648 ... and to

turn to something other than religion on which to guide their political

ideals and justify their ambitions. Thus it was that

non-religious or secular science would begin to take the place of

Christian theology as the new world-view undergirding the new thoughts

and dreams of political philosophers and political activists appearing

at the end of this period of war.

Indeed, at this point Christianity itself would enter into a time of

deep contempt by the more "enlightened" Europeans ... who were certain

that they were on the path of discovery of something much higher, more

noble than the worn-out moral-spiritual standards of Christianity.

Spanish power begins to slip

The wars had been costly to all of the dynastic and urban contenders,

but to Spain most of all. In all the years of Spain's great

wealth in American plunder, Spain had never put that wealth to work,

but had merely consumed it as it rolled in across the Atlantic ...

squandering that wealth in a grand display of status-enhancing material

splendor – and in a constant round of wars with other European

powers. The latter had proven costly to Spain, especially

the ones waged against both the rebellious Dutch and the piratical

English.

The drying up of the American plunder in gold

Everything

about the Spanish economy depended on the continuous flow of American

wealth. But the plunder would run out as the Spanish stripped the

Indian societies of their stock in gold. Confiscated silver would

soon be substituted ... and then slavery of the Indian population to

force them to continue to dig the precious metal from the ground – in

order to feed the material appetite of Spain. But this substitute

of silver would not permit Spain to continue to live at the material

level it had grown accustomed to when it was living on plundered

gold. The silver mines would not suffice to pay the mercenary

armies fighting the king's wars, the navy needed to protect this flow

of wealth from the Americas, and the thousands of government officials

and noble families dependent on this flow. Thus Spain would

decline ... inevitably.

Mediocre kings and royal advisors

Besides

the all-important factor of the gold flow to Spain slowing up as key to

a relentless decline that set in upon Spain in the 1600s, was that this

this process was greatly accelerated by the line of mediocre

Habsburg kings (and their advisers) who followed Charles and Philip in

the 1600s: Philip III (King of Spain, 1598 to 1621)

and his son Philip IV (King of Spain, 1621 to 1665). They were

not bad kings ... just not the caliber of leaders needed by a great

society to hold on to that greatness ... a problem common to all great

societies in decline. Both kings depended on their chief

ministers, the Duke of Lerma under Philip III and the Count-Duke

Olivares under Philip IV. Further, Philip IV was burdened

financially by the costliness of the wars on land and sea that were a

central piece in the 30 Years' War. The English and French had

allied against Habsburg Spanish power – a challenge that Philip knew he

had to answer. Under Olivares's advisement, Philip attempted to

reform Spanish government to make it more efficient so that he could

cover the costs of war (the flow of American gold and silver having

slowed up) ... but in the process only alienated the traditional

Castilian aristocracy that had been the bedrock of royal power.

Then he began to lose further control of the political situation when

in 1640 first the Catalans, supported by the French, revolted – soon

followed by the Portuguese (who sixty years earlier had been brought

into the Spanish Habsburg realm) who did likewise. Compromise

(and removing Olivares) would eventually bring some of the crisis under

control – though from 1640 on, Portugal would remain independent under

the new Braganza dynasty.

The Battle of Rocroi

But the biggest blow came in 1643 when Philip's army was sent south

from the Spanish Netherlands (Belgium) to attack France in order to

divert the French from their support of the Catalan revolt. But

the tactic turned out to be a disaster for the Spanish. It was

the first major defeat of the Spanish army since Spain's rise to power

in the 1500s (Spain's navy, of course, had already suffered its own

setback in 1588) – and clearly signaled a huge slippage of Spain as the

leading power of continental Europe. France would soon be

occupying that prestigious position.

|

The Battle of White Mountain (1620)

in which the armies of the Habsburg Emperor Ferdinand II – in alliance with the forces of the

Catholic League – defeated the Bohemian (Czech) forces ... ending Bohemian independence

and beginning the forced return of Bohemia from Protestantism (Calvinism mostly)

back into Catholicism.

The Great Miseries of War - by Jacques Callot (1632)

Cambridge University

The Battle of Rocroi (1643) - by Sauveru Le Conte

France although officially a Catholic country – opposed Catholic Spain after its many

victories against Europe's Protestant armies ... and met and soundly defeated the

supposedly unstoppable Spanish ... marking the rise to dominance of France

in European continental affairs - and Spain's rapid decline in importance

Musée Condé de Chantilly

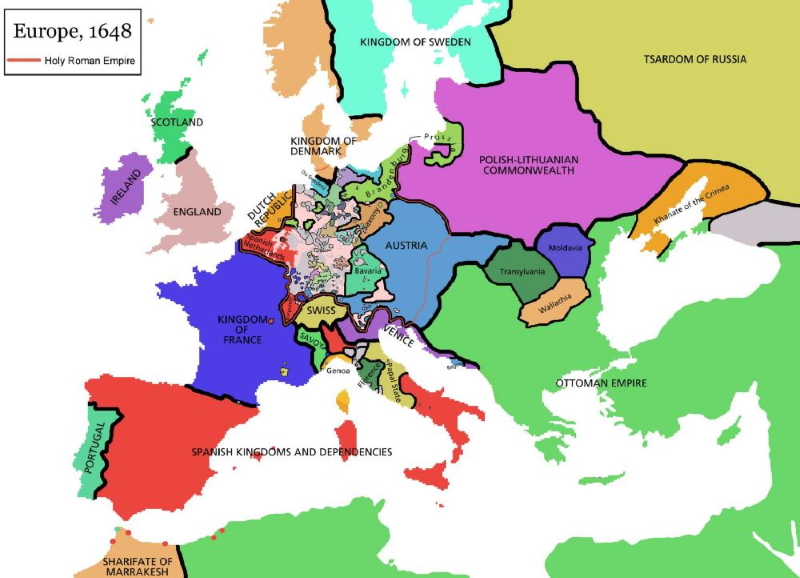

European dignitaries offering an oath in support of the "Peace of Westphalia" - 1648

The Swiss and Dutch now recognized as independent societies; Protestant German states

are recognized as independent: Sweden and France gained territory

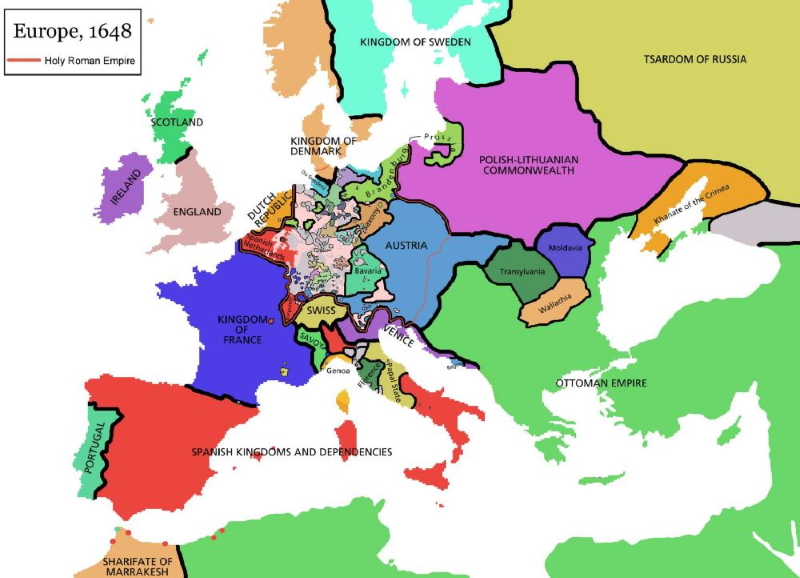

Europe in 1648 - at the time

of the Treaty of Westphalia

|

Against the French nobility

Louis had other problems at home (besides his mother and his rebellious

younger brother Gaston!): the independent-minded French nobility and

the Protestant Huguenots. Richelieu convinced Louis to order the

destruction of all the castles of the nobility, sparing only those of

clear strategic worth to the monarchy. This not only deprived the

nobility of their prestige, but also of their real power. It was

the beginning of the French monarchy as a Absolutist institution (all

power to the king ... and to him alone!). Thus he was widely

hated by the French nobility. But Richelieu was not one to be

contended with.

Against the Protestant Huguenots

Richelieu also stood at the center of the decision to bring to an end

the power and influence of the French Protestant Huguenots. Early

efforts at seizing their various strongholds located around France

(mostly in the South) met with mixed results. Finally in 1628 the

major Huguenot fortress of La Rochelle was overrun by Louis's army ...

led personally by Richelieu. The defeated Huguenots however were

still permitted to practice their religion as per Henry IV's Edict of

Nantes (which had promised certain religious freedoms to the

Huguenots). But in losing La Rochelle, the Huguenots no longer

had any muscle of their own to protect themselves against any further

attacks on their religious freedoms in France.

In the New World (New France)

Since the early 1500s France had been involved in exploring the lands

to the north of the Spanish Habsburg holdings in Central and South

America. Francis I had sent (1520s) first the Florentine

navigator Verrazzano to explore these coastal regions (the first

European to discover what is today New York) then Cartier (1530s) to

explore even further north along the St. Lawrence River (which they

hoped was a river route which would cross the Americas and permit them

to continue to sail West to Asia) laying claim to New France in the

process. But French settlements there at first failed to take

hold. Later (1564) Huguenots escaping troubles in France settled

in the area of what is today northern Florida (Jacksonville) – though

the Spanish quickly reacted and sacked the French settlement

there. Not until the early 1600s would the French under Champlain

try again to establish settlements in the New World ... at Quebec

(1608) on commanding heights above the St. Lawrence River and here and

there along the islands lying to the South of the entrance to the River

... what would eventually become French Acadia. French settlers

were encouraged to befriend the Indians ... whom the French considered

as fully French in accepting Catholicism and learning the French

language. French fur hunters and traders took Indian wives and

soon informally extended French influence deep into Canada.

But until Richelieu took a strong interest in the American project,

French settlement itself remained thin ... particularly in comparison

to New England, just to the south of New France (where by 1630

thousands of English were beginning to settle). Huguenots were

not permitted to settle in New France ... and thus just as New England

was devoutly Protestant, New France by careful design was devoutly

Catholic. Extending feudal rights to French lords or seigneurs

willing to organize and oversee communities of settlers, New France

finally began to grow (only in the second half of the 1600s however ...

and slowly at that).

Against Spain

A

continuous problem, inherited from Louis's predecessors, was Habsburg

Spain. Despite efforts to forge a friendship with Spain through

marriage (Louis was married to Anne of Austria, daughter of Philip III

of Spain), and despite both kingdoms being staunchly Catholic, the

Spanish and French kings (Louis and Philip IV) were natural contenders

for dominance in continental Europe ... especially as Spanish holdings

surrounded French holdings on virtually every front: Spain itself,

Belgium, Luxembourg, Western Germany, and Northern Italy. Thus it

was that the Catholic Cardinal Richelieu advised Louis to ally with the

Protestant Netherlands in the on-going Spanish-Dutch war which raged

during the Thirty-Years' War. But similarly, Catholic Spain sent

aid to the rebellious French Huguenots to keep Louis occupied at home

in France while the Spanish strengthened their position in Northern

Italy!

Louis did not live long enough to see the massive French victory over

the Spanish at Rocroi in 1643 (he died in Paris of tuberculosis just

days before the battle). But he left to his 4-year-old son Louis

XIV a monarchy well on the way to being the major player in the

European dynastic game.

1She

had a reputation as a schemer. It was believed by many at

the time (and by some still today) that she was somehow involved in

Henry IV's death.

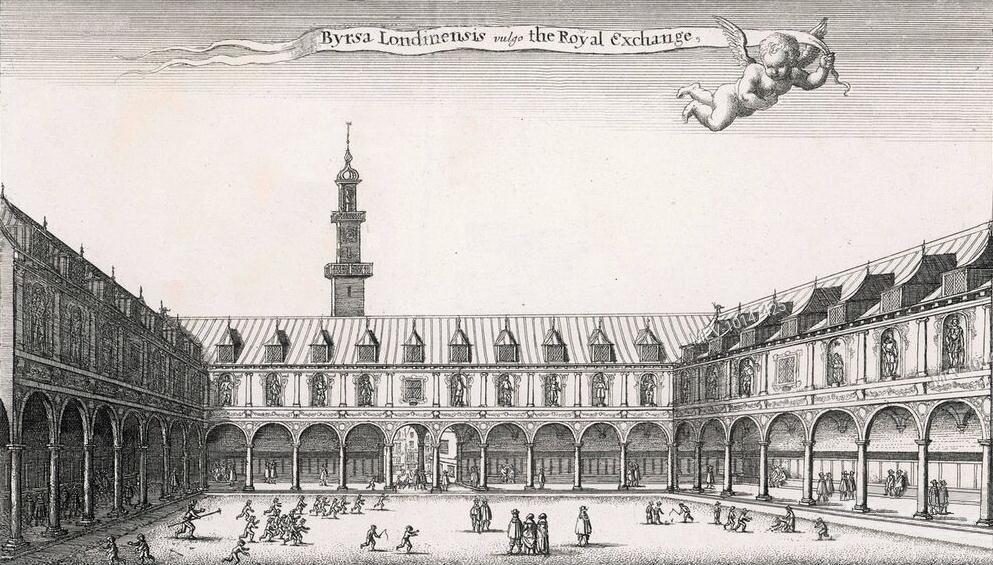

THE ONSET OF THE DUTCH "GOLDEN AGE" |

|

Cruel adversity toughens the Dutch spirit

The Dutch North or Netherlands, though tiny in size on the European

map, had turned itself into a powerful commercial center ... complete

with vast commercial empire, soon reaching around the world.

Cruel adversity had steeled the wills of the Dutch and, along with

their work ethic, had transformed them into the most industrial-minded

people of Europe. They were very creative in their

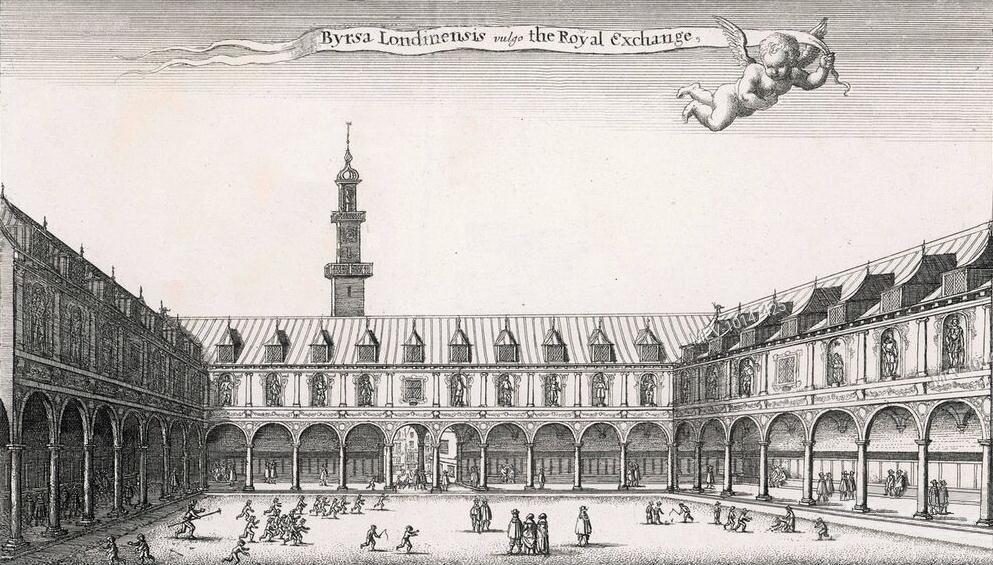

industriousness, setting up in Amsterdam the first multinational bank,

doing business with interested investors across all sorts of political

boundaries. Also at Amsterdam the first stock exchange was

established, where investors (or "adventurers') could put their money

in a new enterprise ... with the hope of making a huge profit when the

enterprise met its industrial or commercial goal. Of course there

were risks of failure. But the strong-willed Dutch were willing

to take those risks.

Dutch commercial expansion

While

they made much of their money in manufacture, the greatest portion came

through commerce or trade. The Dutch were superior tradesmen,

purchasing the goods of distant lands and returning those goods by sea

to Europe ... making huge profits in the process. They thus

developed a vast merchant fleet (the Dutch possessed more merchant

ships than all other European powers combined) protected by a very able

navy. They quickly outpaced the Portuguese in terms of their

commercial reach. Indeed, the Dutch East Indies Company soon

became the largest commercial enterprise connecting Europe with Asia.

The Dutch-Portuguese War (1598-1663)

This process of Dutch expansion – largely at the cost of the Portuguese

– did not happen overnight, but took decades to achieve. The

contest between these two commercial empires was global, from the

Americas in the West to the Indies in the East ... though the East

Indies portion of the war would prove to be the more important

engagement of the Dutch. Success in overrunning most of the

Portuguese positions there turned out to be very profitable for the

Dutch ... as the demand for the spices nutmeg, mace and cloves found in

the Spice Islands was running very high at the time.

Dutch South Africa

Although the Dutch did not succeed in displacing the Portuguese in

coastal southern Africa, when it came to the vital position at

Africa's southern-most tip at the Cape of Good Hope, the Dutch were

most focused. From that strategic point they could then proceed

directly east to the Spice Islands of the East Indies. But they

secured the area not only militarily, but also demographically ...

establishing a large Dutch settlement at what would come to be known as

Cape Town.

Local resistance from the native African population was rather

light. The San (Bushmen or Hottentots) were a very primitive

hunting society, thinly spread across the region. The more

dangerous Bantu African tribesmen had not yet reached the area in their

own expansion southward along the East African coast. In

fact, both groups, Dutch White and Bantu Black were very surprised to

run into each other a century later (1779) when the two

groups, the Dutch spreading northeastward and the Bantu (Xhosa

tribesmen) spreading southwestward, met at the Great Fish River (about

halfway across today's South Africa).

In short, the Dutch were doing in South Africa what the English were

doing at that same time in North America: extending their

population deeply into overseas lands. And – just as the English

of America were beginning to identify themselves primarily as

"Americans" – so too the Dutch of South Africa were calling themselves

"Afrikaners"! And like the English-American frontiersmen who were

largely self-sufficient Protestant farmers, so too were the Afrikaners

– identifying themselves as such also with the name "Boer" (Dutch

simply for "farmer) – and quite proud of that identity ... as these

Boer families spread themselves ever-deeper into the South African

interior.

Dutch America

Also, like the Spanish, Portuguese and French (and soon the English)

the Dutch, through their West Indies Company, got deeply involved in

opening up commerce and settlement across the Atlantic in the

Americas. They established a "New Netherlands" in the middle

reaches of North America, ranging from what is today Connecticut in the

north to Delaware in the South – with New Amsterdam (today's New York

City) as its capital. They particularly focused on the "North

River" (Hudson River) ... hoping it was the waterway that led across

the American continent to the Pacific. Eventually finding this

hope groundless, they nonetheless placed Dutch forts and numerous Dutch

settlers along the fertile shoreline of this mighty river, and opened

up trade in furs with the Indians. Here too, the Dutch population

began to grow.

Dutch independence

Meanwhile, the Habsburg Spanish were refusing to give up in their

effort to retake their ancestral northern Dutch or Habsburg lands ...

as they had so successfully retaken the southern Dutch lands (Flemish

lands actually). But besides the fact that the entrepreneurial

Dutch were quite capable at self-defense, both the English and the

French tended to ally with the Dutch against powerful Habsburg

Spain. Finally, in 1648 the Spanish had had enough of the effort

and in the Treaty of Westphalia acknowledged the independence of the

Dutch Republic.

The highly sophisticated Dutch culture

But the Dutch were not just about business. Art and architecture

flourished, with Dutch artists being some of Europe's finest (Rembrandt

and Vermeer, for instance ... among many others). Education and

science took a huge lead in the Netherlands, with the establishment of

a number of outstanding universities ... and excellent

scholarship. The practical Dutch were fascinated by the physical

world around them and studied it closely, Huygens and Leuwenhoek being

among the leading scientists of their times. But the Dutch could

also lead in the world of scholarly philosophy, Spinoza – a Dutch

Jew of Amsterdam – being an example. So free (relatively speaking

anyway) was the academic atmosphere for study and writing that other

Europeans relocated there ... such as the famous French philosopher

Descartes (from 1628 to just before his death in 1650). |

The Courtyard of the Exchange at Amsterdam

Dutch East Indies capital at Batavia (Dutch Indonesia)

Rembrandt van Rijn – The Night Watch (1642)

Amsterdam Museum

Jan (or Johannes) Vermeer – The Milkmaid (1658)

Rijksmuseum - Amsterdam

Jan (or Johannes) Vermeer – The Little Street (1657-1658)

Rijksmuseum - Amsterdam

SOME OF THE OTHER PLAYERS OF THE DAY |

|

Gustavus Adolphus's Sweden

Under the kingship (1611 to 1632) of this exceptionally talented military commander,2

Gustavus Adolphus, Sweden in short order grew in status from being

merely a regional power to being one of the major powers of early 1600s

Europe. Pressing the Protestant cause in the Thirty Years' War or

Wars of Religion, he took on most notably the very Catholic Eastern

Habsburg Empire (the Holy Roman or Austrian Empire) ... and his

Catholic cousin, Sigismund, King of Poland and Grand Duke of

Lithuania. Much of the Thirty Years" War centered on this

competition between Sweden and the two huge Eastern European states of

Austria and Poland-Lithuania. Spain, Prussia and France also

weighed in big in the War. But Gustav Adolphus" Sweden seemed to

be at the heart of things.

Under the kingship (1611 to 1632) of this exceptionally talented military commander,2

Gustavus Adolphus, Sweden in short order grew in status from being

merely a regional power to being one of the major powers of early 1600s

Europe. Pressing the Protestant cause in the Thirty Years' War or

Wars of Religion, he took on most notably the very Catholic Eastern

Habsburg Empire (the Holy Roman or Austrian Empire) ... and his

Catholic cousin, Sigismund, King of Poland and Grand Duke of

Lithuania. Much of the Thirty Years" War centered on this

competition between Sweden and the two huge Eastern European states of

Austria and Poland-Lithuania. Spain, Prussia and France also

weighed in big in the War. But Gustav Adolphus" Sweden seemed to

be at the heart of things.

Interestingly, when Gustav Adolphus was killed in battle in 1632, his

five-year old daughter (his only surviving child) Christina took over

the Swedish throne ... focusing as much on learning and culture as her

father had on warfare. Meanwhile the business of state, as well

as the excellent Swedish military, was handed over to Christina's

Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna. He effectively governed Sweden until his

death in 1654. He not only maintained the strong military

tradition of Sweden, but worked hard at developing a modern bureaucracy

by which to govern the holdings of the Swedish Vasa dynasty.

Unfortunately

at this point (1654), when Christina abdicated, Sweden fell into the

hands of a less able king, Charles X Gustav, who continued to involve

Sweden in a constant round of battles in North-central Europe (Germany

and Poland) which ravaged the cities and countryside of the

region. However, he lived only a half-dozen years before passing

on the throne to his son Charles XI, who was largely a man of peace

during the next four decades..

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

In the mid-1600s the Commonwealth was assaulted from all directions,

but principally from the East by the Russians who overran the eastern

half of the Commonwealth and from the north by the Swedes who overran

almost all of the western half of the Commonwealth (the "Swedish

Deluge") ... the latter invaders creating such mayhem that nearly a

third of the Commonwealth's population died from military action,

hunger or disease. Worst hit were the cities (Warsaw lost about

90% of its population), hundreds of which were totally destroyed by the

invading Swedes. This began the rapid decline of the once-great

Poland-Lithuania, until both societies disappeared completely in the

late 1700s, absorbed by their neighbors Russia, Austria and Prussia.

Germany

We mention Germany at this point only to make the point that Germany

really did not exist as a political player in the 1600s. Instead

Germany was a collection of a vast number of kingdoms, duchies, cities

... in theory all under the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor ...

that is, the Habsburg Emperor of Austria. The reality was however

that the Habsburg Austrian Emperor governed effectively less than a

third of Germany (in the East and South of the German region).

The rest of Germany was made up of small mini-states under one or

another local ruler. This made for such weakness that Germany typically

served as the battleground for the various contending parties during

the Wars of Religion of the first half of the 1600s.

Germany was devastated by these ongoing wars ... losing over a third of

its population (in some areas far worse than that figure) ... through

the battles, the devastation of the land (again, in great part by the

Swedes) and the resultant hunger, and the diseases which accompanied

all of that. Unfortunately for Germany, it would remain a

victim-territory until well into the 1800s ... when finally (1870) the

Prussians (led by the skillful Chancellor Bismarck) would succeed in

uniting most of Germany as the Second German Empire.

2Many

– such as the Prussian Clausewitz, the Frenchman Napoleon and even the

American Patton – considered Gustavus Adolphus a military genius, and

studied carefully his use of heavy artillery, smaller but very mobile

infantry units, and speed rather than mass in the employment of his

troops.

Axel Oxenstierna

Sigmund III Vasa

Charles X Gustav

ENGLAND OF THE STUARTS AND PURITANS |

|

James I Stuart and the Divine Rights Theory

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) there had been a

moderately tolerant working relationship between the Queen and the

Protestant (Calvinist) reformers. The burghers of London and

other English cities were for her an invaluable source of financial and

other support for her rule – which was continually on the defensive

against the likes of the "Catholic" defender Philip II of Spain.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) there had been a

moderately tolerant working relationship between the Queen and the

Protestant (Calvinist) reformers. The burghers of London and

other English cities were for her an invaluable source of financial and

other support for her rule – which was continually on the defensive

against the likes of the "Catholic" defender Philip II of Spain.

Lacking an heir of her own, it became apparent that Tudor rule would

eventually pass into the hands of the Stuarts of Scotland. Though

Mary Stuart had been an ardent Catholic, her son James had been raised

in Protestant (Calvinist) circles. In 1603 when Elizabeth died

and indeed James came to the English throne as James I, it might have

appeared that the going would henceforth be better for the Protestants

in England.

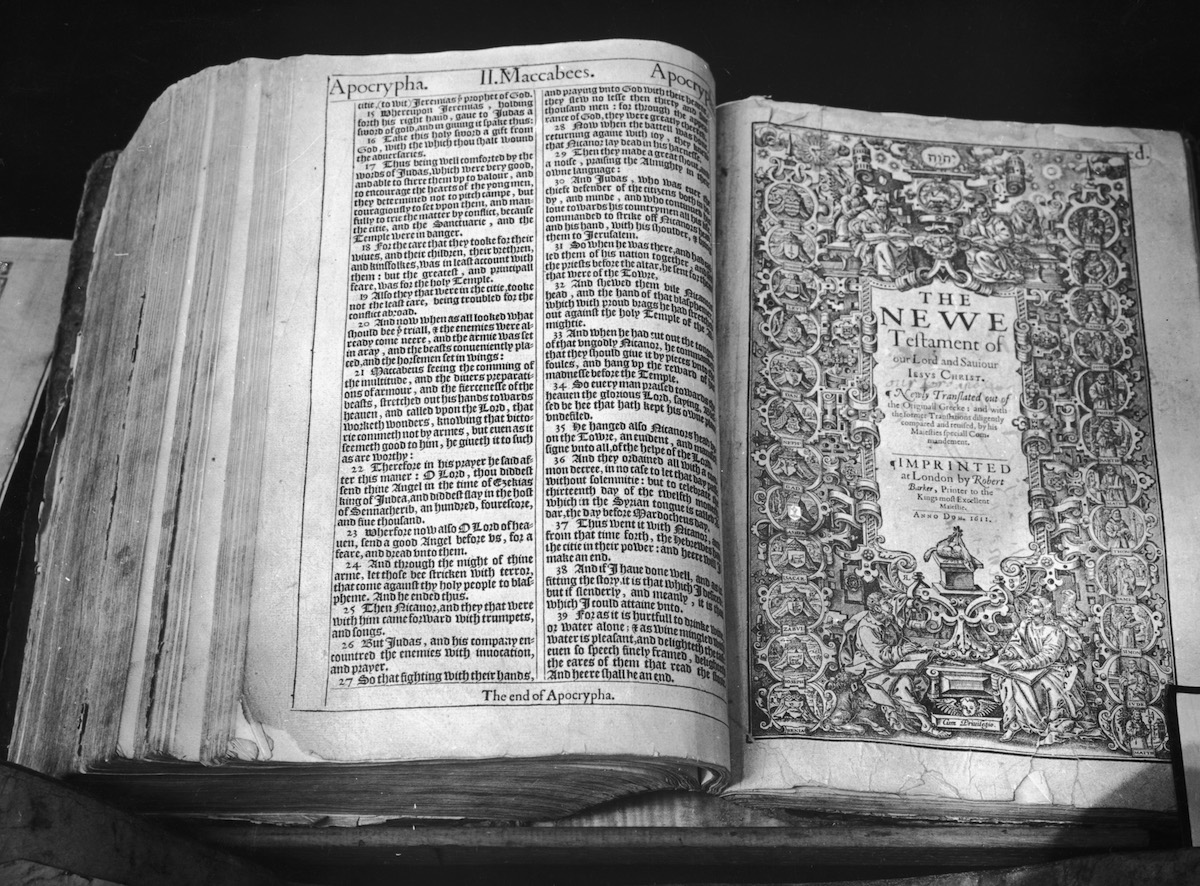

In

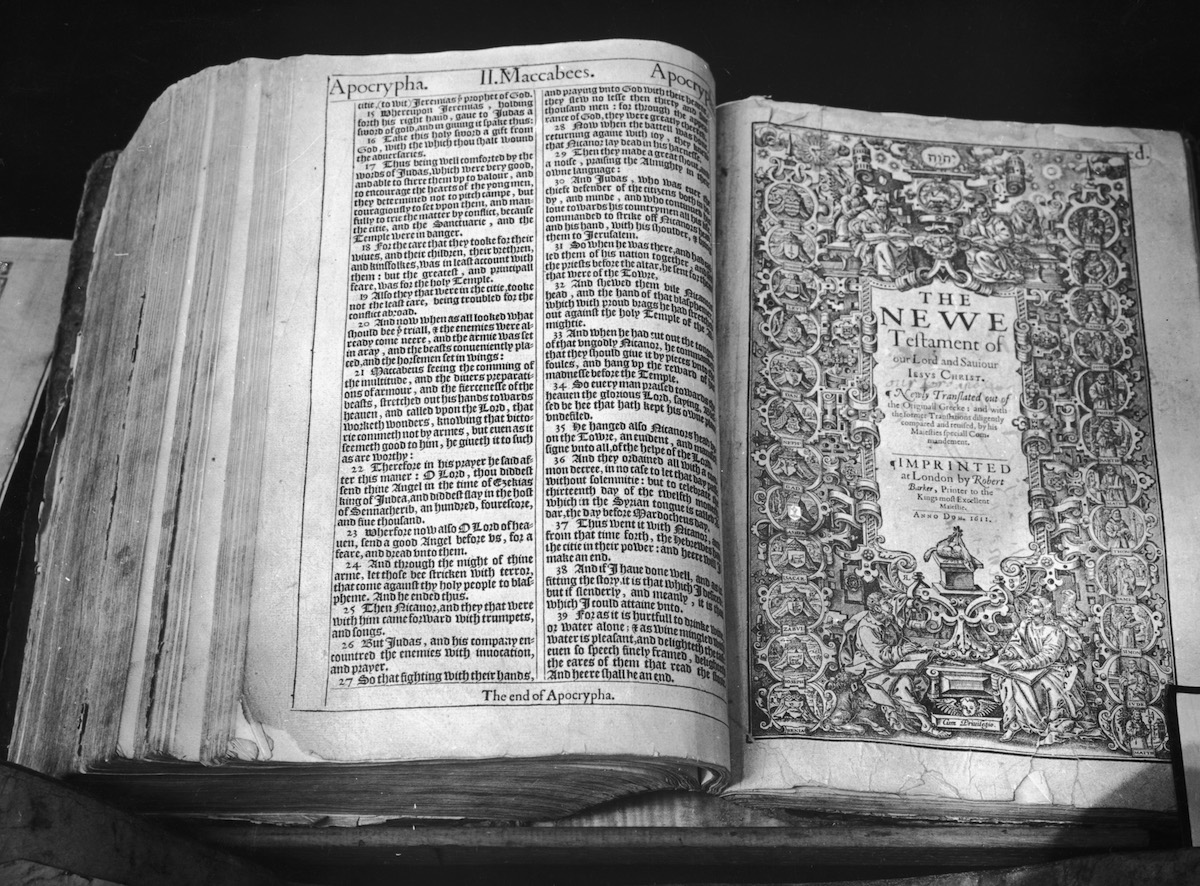

many ways James played to the Protestant reformers. He sponsored

a new English translation of the Bible (the venerable King James

version!), which pleased the reformers greatly (though the Puritans

seemed to continue to rely mostly on their beloved English-language

Geneva Bibles). He also was himself strongly opposed to the

re-opening of England to Catholicism – though mostly for political

reasons than for reasons of religious conscience.

But he also was a thorough royalist, strongly supportive of the "divine

rights" theory of monarchy by which the claim was put forth that kings

were responsible to God alone – and not to any human agency (such as

Parliament). Unfortunately, he would soon discover that

Parliament had a mind of its own and expected the king to share rule

with Parliament. Little by little tensions began to mount as the

King and Parliament came into conflict.

Part of his difficulty would be over the matter of religion. He

had during his earlier days as King of Scotland tired of the "upstart"

behavior of the Scottish Calvinists. He was now prepared to rule

directly over the Christian community in England – through an episcopal

system (a hierarchy of archbishops and bishops) that linked all the

Church of England to his personal rule as Head of the Church of

England. Thus was he much opposed to the idea of Presbyterian

government (the Calvinist idea of rule by "elders" or leaders from

among the commoner or burgher class) at the local level. During

his rule he actively discouraged the growth of independent or

"separatist" communities and congregations – that is, local communities

and churches that tried to work independently outside of the episcopal

system.

Overall, this was not a position all that different from Elizabeth's –

except that he lacked her political insights and thus found himself in

trouble on a number of fronts at the same time.

The development of Puritan power

Cambridge

University was at this time a hot-bed of Calvinist religious

thinking. Sons of prosperous English burghers came to this

venerable institution to explore a world of widening economic,

intellectual and spiritual opportunities. Here at Cambridge young

men began to fashion a purist or "Puritan" vision of a newly emerging

society, one operating directly under the sovereignty of God ... making

the place of the sovereign king a bit problematic. They supported

what was sort of a theory of "divine rights" of burghers – in

opposition to the "divine rights" theory of the monarchy. These

independent-minded scions of the burgher class came to see themselves

not as essentially subjects of the English crown, but as subjects of

God. According to their Calvinist or Puritan mindset, individuals

were to be led in living out their lives guided or governed only by

their own scripturally-disciplined minds and their own

prayerfully-cultivated Christian consciences. Nothing was to

stand between themselves and their beloved God. Not even an

English king.

Separatists and Puritans

It was not long before there was a

clash between Royalist and Puritan views – especially Separatist

views. Unlike the fellow-Calvinist Puritans, Separatists had

given up on the project of trying to reform the Church of

England. They concluded that the King was so adamantly opposed to

serious reform that there was no point in continuing to try to reform

the Church of England. Separatists were Puritans who simply were

ready finally to "separate" from the mother Church.

The other Puritans were not pleased with Separatism, considering the

Separatists as being something like traitors to the reform cause.

Puritans were not ready to give up the reform fight. Separatists

were.

One such group of Separatists, led by a Cambridge-trained pastor,

John Robinson, finally decided early on to leave England entirely and resettle

themselves in Holland (1608) where they could live in a Christian community

that operated in accordance with their Puritan principles. Some

of this same group would later (1620) make yet a second move as

"pilgrims" in pursuit of their dream, this time to the new world – to

Plymouth, Massachusetts. |

James Stuart - King of Scotland (1567-1625), and England and Ireland (1603-1625)

King James's "Authorized Version"

(actually most Puritans tended to hold on to thir beloved Geneva Bibles)

The London Royal Exchange (early 1600s) – where commercial fortunes were made (or lost)

Pastor John Robinson leading the Pilgrims in prayer

prior to their departure for America -1620

|

Charles I (1625 – 1649)

When James died in 1625, his son Charles I came to power. Generally,

policies continued much as they had under James – except that the

debate over royal power was now widening and deepening in

intensity. On the continent the doctrine of royal absolutism (all

power rightly belongs to the king) was being aggressively put forward

in the French (Louis XIII) and Spanish (Philip IV) courts.

Inevitably the issue came to England.

Charles immediately upon his accession to power brought an even more

aggressively royalist and aristocratic (or "cavalier") mood into

English politics. Charles favored the old landed families (many

of whom had Catholic sympathies) over the new independent minded

burgher (urban middle class) families in his appointments to the royal

court. In particular, he allowed himself to come under the

dominating influence of Buckingham, one of his father's advisors.

Buckingham was very much a royal absolutist – one who was inclined to

make no compromises with the burgher interests of Parliament.

Charles also stirred considerable political resentment by immediately

putting aside all the laws that had blocked Catholicism from English

politics. Likewise, his diplomacy of befriending Catholic kings

on the continent (even marrying his son to a Spanish princess) was

interpreted as the precursor of even reestablishing Catholicism in

England. This was not something that the Puritan majority in the

House of Commons would take lying down. The stage for violent

confrontation was thus being set even from the outset of Charles' rule.

Charles tried for 11 years to rule without Parliament – which meant

also ruling without the financial support of this powerful group of

English merchants. This forced him to take very contrived and

largely unsuccessful measures to raise his own monies in order to

maintain his royal courts and armies. Charles simultaneously

tried to engage in foreign ventures he hoped would rally the English to

his side. But tensions only mounted with the gentry who would not

play into his programs.

Rapidly Deteriorating Political Conditions

Charles eventually turned more and more to William Laud, archbishop of

Canterbury, for ideological support. The appointment of Laud, a

self professed Arminian,3 as Archbishop of Canterbury angered the

Calvinist Puritans enormously – who saw this as a move against their

own position (which it was!). Further, Laud's efforts to put the

entire Christian community in England under episcopal rule and in total

conformity to the Prayer Book only drove the wedge deeper between the

royal court and the Puritans in Parliament.

Charles eventually turned more and more to William Laud, archbishop of

Canterbury, for ideological support. The appointment of Laud, a

self professed Arminian,3 as Archbishop of Canterbury angered the

Calvinist Puritans enormously – who saw this as a move against their

own position (which it was!). Further, Laud's efforts to put the

entire Christian community in England under episcopal rule and in total

conformity to the Prayer Book only drove the wedge deeper between the

royal court and the Puritans in Parliament.

When a rebellion in Ireland flared up, the issue of who should control

the army came to the fore. Pym, leader of the more reformist

members of Parliament, narrowly succeeded in a vote to place the army

under Parliamentary authority. But Charles refused to

yield. With this, England found itself in a state of deep

political division between King and Parliament. It now had two

armies: the King's and Parliament's. Things were heading towards

a show-down.

But it was his Scottish subjects who would actually start the open

rebellion against Charles ... when he attempted to unite the heavily

Calvinist Church of Scotland with his Church of England. Specifically,

when Laud tried to impose the Prayer Book on the Scottish church, an

explosion in Scotland, Charles' home country, occurred. In 1639

Charles sent his ill paid royal army into Scotland to force

acceptance of this decree ... only to find himself met strongly by

Scottish forces.. A truce was agreed on, which Charles soon broke

in a second attack on Scotland the following year.

Parliament takes the initiative

Again, things went poorly for Charles in Scotland ... and desperate for

funding for his army, he called Parliament back into session in late

1640. But when Parliament put forth its own demands for the

undoing of Laud's episcopalian reforms in exchange for its cooperation

– the King dissolved Parliament (the Short Parliament)

immediately. But the king's situation only deteriorated and

soon he had to call Parliament (the "Long Parliament') back into

session. This Parliament would not be dissolved until 20 years

later. It was about to become the effective ruler of England.

Parliament now took action ... to remove (and subsequently execute)

Laud, to greatly restrict the King's ability to raise revenues, and to

make it impossible for the King to dissolve Parliament without its own

consent.

Charles at first complied ... hoping to avoid what was clearly becoming a drift toward war in England itself.

But the King fought back, especially when he saw division setting in

among the ranks of Parliament as to how to proceed, whether moderately

or radically. In early 1642 Charles moved to have five of

Parliament's leaders arrested ... but warned ahead, the five had

already fled when Charles showed up with an armed guard. This

event proved to be politically disastrous for Charles, now driving the

Parliamentary moderates into the arms of the radicals.

Fearing what might happen next, Charles immediately headed north.

But then in mid-1642 he decided to return to London. Some of the

country was coming out in support of him (basically the conservative

countryside) and he was hoping to force his way back into

supremacy. But urban England (and the navy) supported

Parliament. And thus the two sides gathered armed forces in

direct opposition to each other. The English Civil War was now

underway, initially taking the form of local battles here and there

around England.

The Civil War (1642 – 1649)

At first the war seemed that it should go in favor of Charles and his

"Cavaliers." But by 1643 the fortunes of war seemed to be turning

in favor of the Parliamentary troops and their army of "Roundheads"

(identified by their short haircuts ... in distinction to the long

curls of the Cavaliers, which was the fashion at the time in the royal

courts of Europe). Charles's army, though superior in size,

proved timid ... and gave the Parliamentary army an opportunity to

organize itself. Also, the Scottish army in 1643 came into the

struggle on the side of the English Parliamentary forces.

Finally, in 1644 the very capable Oliver Cromwell began to make his way

forward as a military leader. He mixed Puritan spiritual

discipline with incredible military discipline to produce a "New Model

Army" – which proved itself to be a powerful fighting instrument on

behalf of Parliament. In 1645, the entire Parliamentary Army,

reorganized along Cromwell's lines, met and crushed the royalist forces

at Naseby and Langport. The King escaped to Scotland,

surrendering himself to Scottish authorities, only to have them in the

following year (1646) – after receiving a huge payment from the English

– turn him over to the English Parliamentary authorities. With

Charles in prison the Civil War (at least its first phase) simply came

to a close.

Finally, in 1644 the very capable Oliver Cromwell began to make his way

forward as a military leader. He mixed Puritan spiritual

discipline with incredible military discipline to produce a "New Model

Army" – which proved itself to be a powerful fighting instrument on

behalf of Parliament. In 1645, the entire Parliamentary Army,

reorganized along Cromwell's lines, met and crushed the royalist forces

at Naseby and Langport. The King escaped to Scotland,

surrendering himself to Scottish authorities, only to have them in the

following year (1646) – after receiving a huge payment from the English

– turn him over to the English Parliamentary authorities. With

Charles in prison the Civil War (at least its first phase) simply came

to a close.

Disagreement within the Protestant ranks of Parliament

At this point a split occurred within the ranks of the Parliamentary

coalition. Most of the Protestant members of Parliament were

"Presbyterian" in persuasion and were willing to free the King in

exchange for the establishment of the Presbyterian form of church

government throughout England. But many of the English

Protestants, numerous in the Parliamentary army, were "independents" or

"congregationalists" and wanted local congregations to have the right

to organize themselves as they saw fit.4

This division led Charles to undertake from prison secret negotiations

with the very Presbyterian Scots, promising the very Presbyterian Scots

to institute Presbyterianism in England in exchange for support by the

Scottish army. Thus the character of the Civil War now shifted

into something of a nationalist struggle – an English Parliamentary

Army under Cromwell and a Scottish Presbyterian Army supporting Charles.

But again, in this second phase of the civil war (1648-1642) things did

not go well for Charles ... or the Scottish Presbyterian army.

Also Charles had been counting on his former supporters in England to

retake arms. But most refused (having previously promised under

oath not to do so). Those that did were quickly seized ...

and beheaded (for breaking their oath).

The Rump Parliament

This led to the question of what to do about the King. The matter

was quickly decided by the army itself when it marched on Parliament

("Pride's Purge") and arrested the MPs who had been willing to work out

a compromise with the King and blocked the entrance of most of the

rest. The small number of MPs remaining (only 75 of the original

470 members of the Long Parliament)5 were ordered to set up a High Court

of Justice to try the King on charges of high treason.

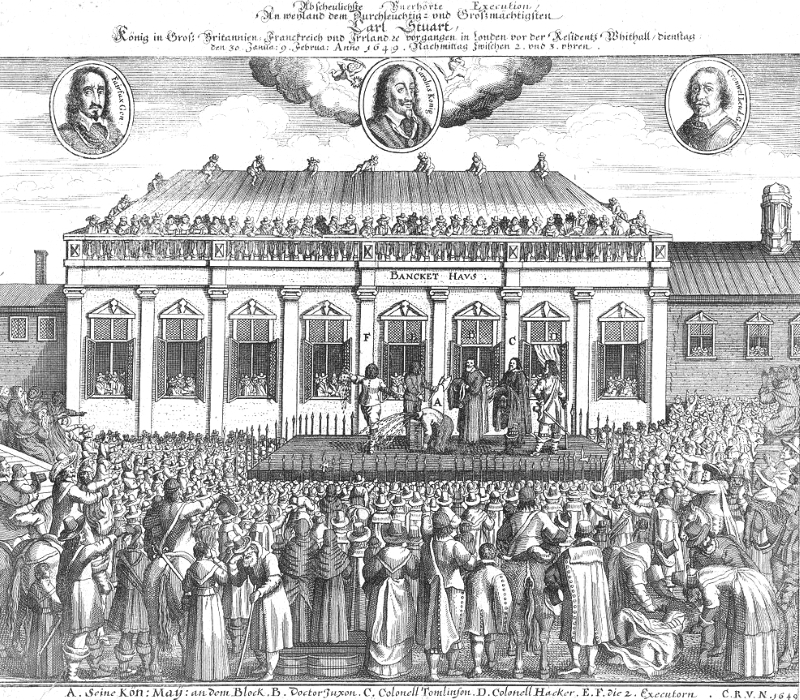

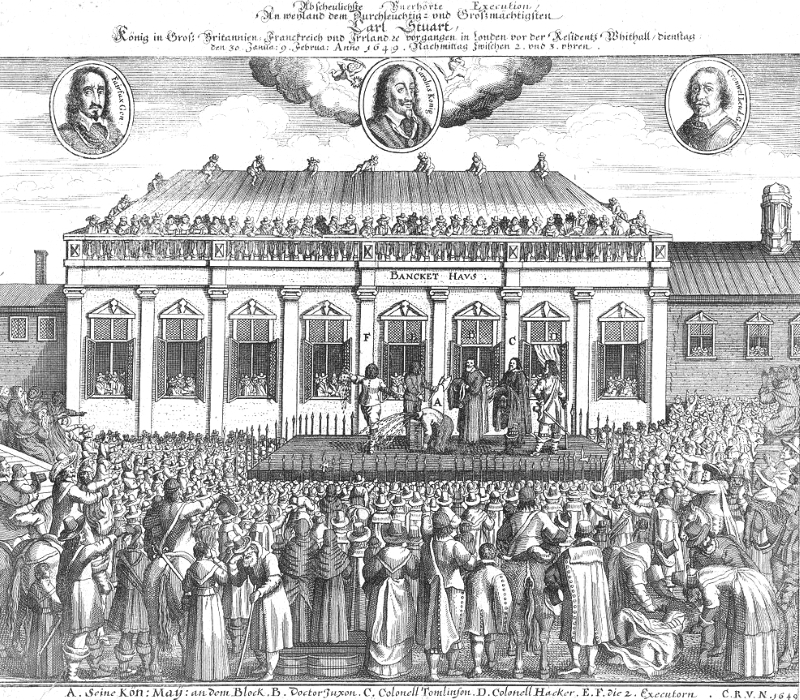

The King is beheaded (1649)

Fearing that the King and the Presbyterians might work together to

create a new pro-royalist Presbyterian Parliamentary army, there was

only one verdict likely to be forthcoming from just such a court.

Thus in January of 1649 the court found Charles guilty as charged ...

and at the end of the month the King was beheaded.

The nation was shocked – but subdued by this show of power. In

any case, this effectively removed the rallying cause for opponents of

Cromwell and his army of Independents.

Charles II is proclaimed King ... but flees to France

Nonetheless, his eighteen-year-old son (also "Charles') was immediately

proclaimed by the Royalists as King of England, Scotland and

Ireland. Royalists in all three countries attempted to take power

in the name of the new king. But all this did was to return all

three lands to violent civil war.

Reacting to the announcement of Charles II's assumption of royal rights

in Scotland, the Rump Parliament now moved to abolish the monarchy and

the House of Lords, declaring England under a newly drafted

Constitution to be a Commonwealth directed by a Council of State.

Actually it was Cromwell and his army which were in effective control

of England at this point.

3The

Dutch Reformer Jakob Arminius (1560-1609) questioned the strict

Calvinist (Pauline) understanding that salvation was by grace extended

by God alone … not by human good intentions or good works. His

supporters, the Remonstrants, insisted that salvation was at least in

part a matter of the free choosing of the individual. A Dutch

synod held at Dort in 1618-1619 – attended by Calvinists from other

parts of Europe – opposed strongly the Remonstrants and their

"Arminianism."

4As previously

explained, Presbyterians supported the idea of a system of church

unions, all the churches at the local or regional level constituting a

Presbytery, a number of Presbyteries joined together to constitute at a

higher level a Synod (Senate), and the Synods united into a General

Assembly. Positions of membership and leadership in these bodies

were entirely elective on a regular (even annual) basis by church

members ... to ensure a democratic character of the whole (unlike the

episcopal system of church appointments from the King on down to the

archbishops to the bishops). The independents or

"Congregationalists" wanted to have no part of any higher union above

the local churches, each of which was supposed to be entirely

self-running. The difference between the Presbyterian and

Congregationalists was thus political, not religious, because both

groups were strong Calvinists theologically.

5Actually

the Rump Parliament would see the gradual return of almost half of the

original Members of Parliament ... most of whom considered the other

half to be still fully Members of Parliament – and hoped to see some

kind of compromise able to bring about their return.

Charles I

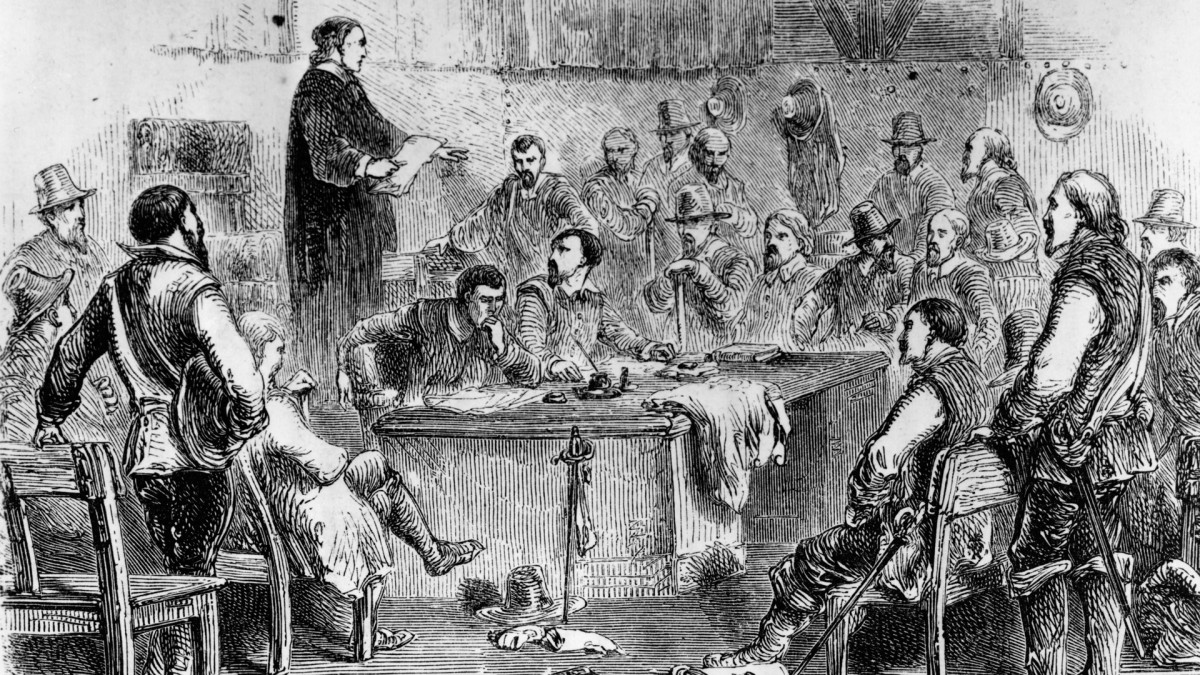

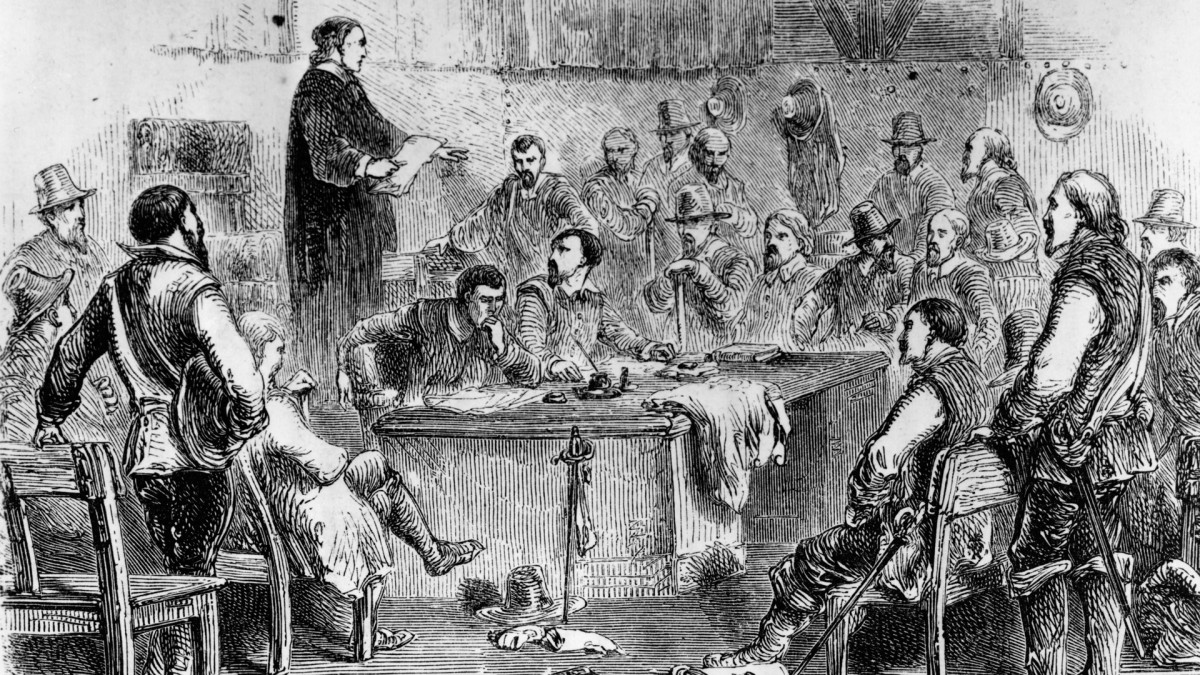

The Trial of Archbishop Laud - 1644 (he is beheaded on January 10, 1645)

Cromwell – having captured Charles's personal baggage and correspondence

at the Battle of Naseby (June 14, 1645)

Pride's Purge of Parliamentary members - December 6, 1648

Charles I is beheaded (1649)

Spain

had not appeared as interested in North America in its efforts to bring

the Western Hemisphere under Spanish control and therefore that area

seemed to offer the best possibilities for others to get in on the

act. By the beginning of the 1600s it seems that the time was

right for others to do exactly that – particularly after the Spanish

army and navy had experienced a string of disastrous setbacks trying to

keep both their Dutch subjects from breaking away from Habsburg

authority and the English privateers (actually merely pirates

officially authorized by English Queen Elizabeth) from harassing

the Spanish fleets bringing gold from America. Thus (as we have

already seen) the French sent traders to Canada to take advantage of

its great wealth in animal furs – and sent priests to Canada to bring

Indian souls to Christ. Also the commercially minded Dutch set up

a merchant orporation to bring back the wealth of the central

shores of North America – and to find passage through America to Asia,

hopefully up the Hudson River where they positioned some Dutch

settlements.

The Virginia Company

A strictly commercial venture. Likewise the English formed a similar merchant corporation, the

Virginia Company, to do the same for the area along the shores of the

Chesapeake Bay. In 1607 a small fleet set out to site a colony

named Jamestown along the James River – both named after the English

King, James I. The motif of the venture was the same as it had

been for the Spanish: for the adventurers to find Indian gold and thus

secure their positions as rising noblemen ... or at least as something

like "gentlemen."

However gentlemen did not perform manual labor – which presented a

problem for the Virginia Company, as most of the participants in this

venture were attempting to establish for themselves ratings as

"gentlemen." John Smith succeeded in making himself unpopular by

commanding his fellow merchant adventurers to take up necessary labor

if they hoped to eat. Some had brought along indentured workers

to do the work for them. But most of the adventurers attempted to avoid

the responsibility of manual labor. As a consequence the new

plantation at Jamestown suffered tremendously from the lack of

food. This, plus not taking the time to properly site the new

colony (they put it alongside a mosquito-laden swamp) caused the

adventurers to sicken and then die in droves. More workers were

brought in, but the venture had enormous difficulty trying to function

as a successful settled community.

However gentlemen did not perform manual labor – which presented a

problem for the Virginia Company, as most of the participants in this

venture were attempting to establish for themselves ratings as

"gentlemen." John Smith succeeded in making himself unpopular by

commanding his fellow merchant adventurers to take up necessary labor

if they hoped to eat. Some had brought along indentured workers

to do the work for them. But most of the adventurers attempted to avoid

the responsibility of manual labor. As a consequence the new

plantation at Jamestown suffered tremendously from the lack of

food. This, plus not taking the time to properly site the new

colony (they put it alongside a mosquito-laden swamp) caused the

adventurers to sicken and then die in droves. More workers were

brought in, but the venture had enormous difficulty trying to function

as a successful settled community.

Tobacco to the rescue.

No gold of any significance was to be found in Virginia. But an

entrepreneurial individual, John Rolf, picked up some tobacco seed when

at first stranded in Bermuda and then was able to bring his discovery

along with him to Virginia ... and start up what became a very thriving

tobacco industry. Others caught on, and soon tobacco farming and

shipping back to England became the economic mainstay of Virginia.

A Virginia aristocracy develops on the European model. However the colony began slowly to settle in ... and develop a degree

of social order. In 1619 a governing Assembly (the House of

Burgesses) representing all male landowners in Virginia gathered in

Jamestown as the first elected government in English America.

However it was understood that the representatives themselves to the

House of Burgesses were naturally to be drawn from the class of local

Virginia aristocrats or gentlemen owners of the major Virginia

plantations. Virginians held the social or cultural understanding

that it was the proper thing to do in deferring to one's social betters

– just as one did back in England.

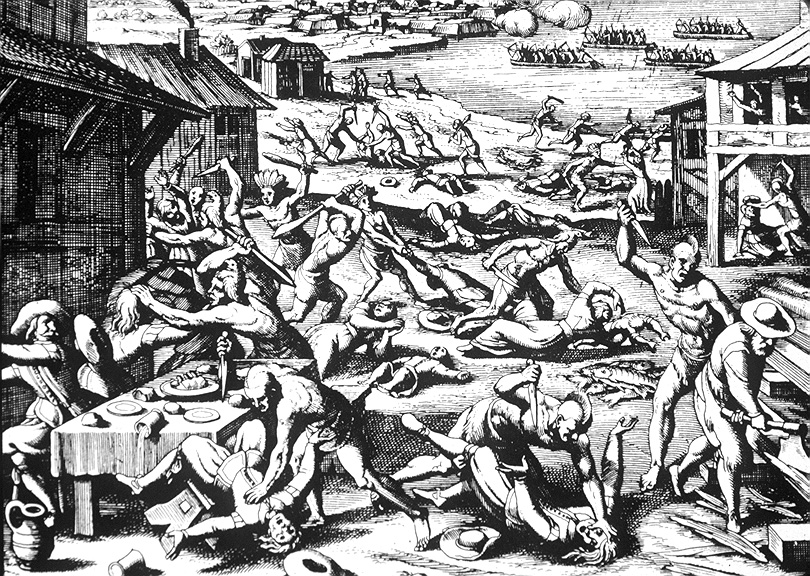

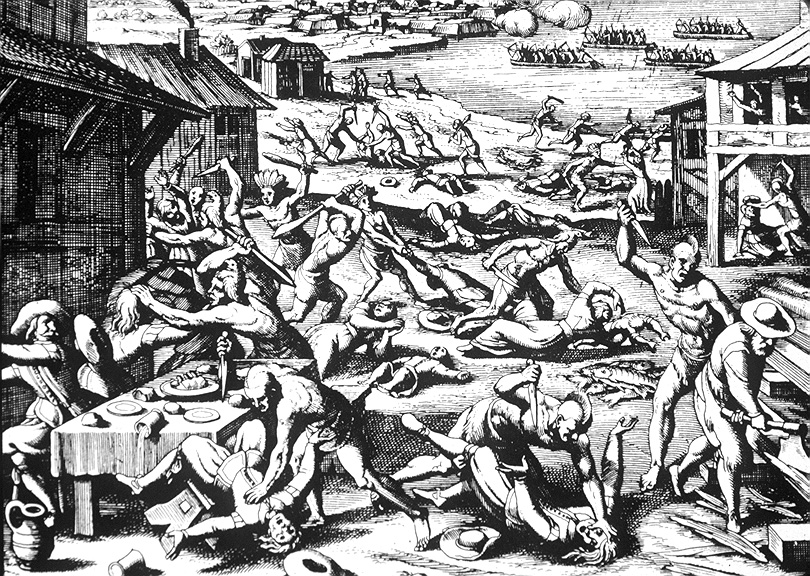

Then in 1622 a major Indian attack which resulted in the death of some

300-400 colonists – and rumors of the deputy governor's mismanagement

of the colony – caused King James to end the Virginia Company's charter

in 1624, converting it into a royal colony directly under the King

himself (but governed by a royal Governor appointed by the King.)

The House of Burgesses continued to meet, though its power was reduced

somewhat. But the real power of the royal colony was now located

in the Governor's Council consisting of the Governor and a small group

of advisors drawn from the wealthiest Virginia plantations (the

Virginia aristocracy).

Servitude and Slavery

Despite

the emphasis placed on the event of 1619 when some 20 Angolan Africans

were brought to Virginia as slaves, slavery was hardly a novel

institution in the New World. It had been going on, particularly

in the nearby Caribbean Islands, for a century. And it simply fit

right into the idea that there were two classes of people at the time,

property-owners, and those who worked that property. Indenture

and slavery had much in common, in that those who fit the category as

either indentured worker or slave had no particular rights of his or

her own under that category. Even indentured workers were

considered the "property" of the person ("master") possessing their

indenture ... an indenture that could be bought and sold to other

wealthy owners if need be. But there were some key

differences. A person usually chose to accept indenture in order

to receive funding to cover the cost of the trip to America ... and

with the understanding that at the end of the tenure of the indenture

(usually seven years) that individual would receive not only the

training developed during the indenture but also land rights and tools

to allow himself (or herself) then to set himself up independently in

the New World. Slavery had no such options ... but involved a

lifetime of service ... and a similar servitude passed on to any

offspring of such slaves.

Actually at first, slavery in Virginia was not a tightly defined

institution ... some Africans actually being classed as indentured

workers – presuming that upon attaining personal freedom, they would be

able to take on indentured workers of their own. But with time

(the later 1600s and certainly by the beginning of the 1700s) slavery

became a fully-legalized part of the Virginia social scene ... and

identified most closely with those of African origin.

Virginia's God

Despite this rather "un-Christian" picture of the very rich lording it

over the poor, both black and white – Virginia was not Godless.

Attendance at church (the Church of England directed by the King and

the bishops he appointed) was required of everyone. But there

were few pastors that accompanied the early settlers to Virginia and,

as in England, attendance at worship was viewed more as a duty than as

a right or privilege. Ultimately Virginia was no more or less

religious than most of "Christian" Europe of those days.

|

The Arrival at the future Jamestown

The Fort at Jamestown

Africans (Angolans) for sale at Jamestown – 1619

A meeting of the Burgesses at Jamestown

The Indian attack on the Virginians - 1622

|

New England

Meanwhile to the north of the Virginia colony in an area that would

come to be known as "New England" an English settlement of quite a

different character was taking shape. Whereas the Virginia colony

was from the very outset an experiment in social improvement through

the acquiring of wealth and thus status in a largely feudal cultural

setting, New England was a definite religious experiment based on the

strong religious feelings stirred by the Protestant Reformation in

England. New England was an experiment in building a "reformed"

society, from the ground up, according to strict Biblical

principles. It was an experiment in building a "New Jerusalem," a

"city on a hill," able to shed Christian light to the rest of the world.

The Separatist "Pilgrims"

The first to make the move to New England in this matter would be a

group of Separatists ... who would gain for themselves the title of

Pilgrims, for their world was indeed a world of pilgrimage – religious

pilgrimage. Under the threat of imprisonment for their religious

"treason," a small community of Separatists escaped to the Netherlands

to live among fellow Calvinists like themselves. But it was a bad

time to be looking for help in the Netherlands, as the Dutch were fully

occupied at trying to keep themselves from being destroyed by the

Spanish troops that had invaded their country. Thus economic hard

times – plus watching their children abandon their English heritage as

they began to take up Dutch culture – decided a number of these English

Separatists to make yet another move: to America.

After political and economic complications with English investors and

with royal authority, plus missteps in getting themselves across the

Atlantic so late in the season (November 1620), these Pilgrims were

able to set up a new community just opposite Cape Cod in the area known

as Massachusetts. Here with the help of friendly Indians they

were able to found the colony of "Plymouth" ... and begin to live out

the religious experiment they had long been seeking.

The Puritans join them

With so much persecution back in England after Charles took the throne

as English King in 1625 ... the Puritans who had looked down on the

Separatists as traitors to the Reformed cause now themselves realized

that "separation" was the only option available to them ... short of

civil war. Thus in 1630 and for the next ten years after that,

some 20,000 Puritans left England and sailed to America to found and

develop there the Massachusetts Bay Colony, just to the north of the

Plymouth Colony.

John Winthrop.

Organizing, leading, and serving as the spiritual mentor to this

venturesome group of Puritans, was Winthrop. He led the first

group of 1000 Puritans to the Boston area, was quick to link up with

the Plymouth Pilgrims, and thus was to learn from them some of the

secrets of survival in this strange new world. John Winthrop.

Organizing, leading, and serving as the spiritual mentor to this

venturesome group of Puritans, was Winthrop. He led the first

group of 1000 Puritans to the Boston area, was quick to link up with

the Plymouth Pilgrims, and thus was to learn from them some of the

secrets of survival in this strange new world.

These Puritans were not economic refugees or social climbing

adventurers. They came from stable Middle Class English stock

which (unlike the Virginians) had developed the Calvinist attitude

toward hard work as not only the way to please God but also the way to

build for themselves and their families fairly prosperous lives.7

They were literate (the ability to read the Bible was an absolute requirement) ... indeed, well-educated in the three "R's" (Reading, wRiting and aRithmatic),

and well led by university-educated (usually Cambridge University)

clergy, with usually just such a pastor assigned to each of the many

New England villages.8

The Massachusetts Bay Company, which sponsored this mass movement of

Puritans, carefully laid out each new village with a certain size of

population and a specific allotment of farmland, complete with a

"meeting house" at the center of each village – serving as a church on

Sundays, a school for children during the daytime on weekdays, and a

hall for town meetings as needed in the evenings.

A deep sense of the equality of all (reflective of their understanding

that all are esteemed as equals in the eyes of God) stood at the heart

of the social agenda of New England. These Puritan/Separatist New

Englanders worked together as equals, studied together, and defended

themselves together (such as the "minute men" who were trained to

assemble from their fields or homes in a moment's notice if the village

were threatened ... usually by an Indian attack).

Being able to work as a community, except for the Pilgrim's very first

winter when the Pilgrims lost half their number due to winter exposure,

there would be no "dying time" such as the Virginia Colony experienced

repeatedly. Thus the New England colony prospered well beyond the

level of the Virginia colony ... and grew accordingly.

7This was the origins of the famous "Yankee work ethic" for which Americans would become world famous.

8Thus it was that

Harvard College was founded (1636) in Boston shortly after their

arrival to America, primarily to educate just such pastors. The

heavily Episcopalian Virginia would not do the same (College of William

and Mary) until almost the end of that same century (1693).

The first Thanksgiving of the Separatist Pilgrims - 1621

Winthrop and his Puritans depart for America - 1630

Puritan worship in Massachusetts

Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson

This is not to say that New England did not have its problems. People

brought their personal issues with them to New England, such asthe

pastor Roger Williams ... for whom the Puritan settlements were never

religiously "pure" enough and who finally was invited in 1636 to take

his purity elsewhere ... though in establishing his own colony of

Providence (Rhode Island) he quickly ran into many of the same problems

himself and soon restored a close friendship with Massachusetts' leader Winthrop. This is not to say that New England did not have its problems. People

brought their personal issues with them to New England, such asthe

pastor Roger Williams ... for whom the Puritan settlements were never

religiously "pure" enough and who finally was invited in 1636 to take

his purity elsewhere ... though in establishing his own colony of

Providence (Rhode Island) he quickly ran into many of the same problems

himself and soon restored a close friendship with Massachusetts' leader Winthrop.

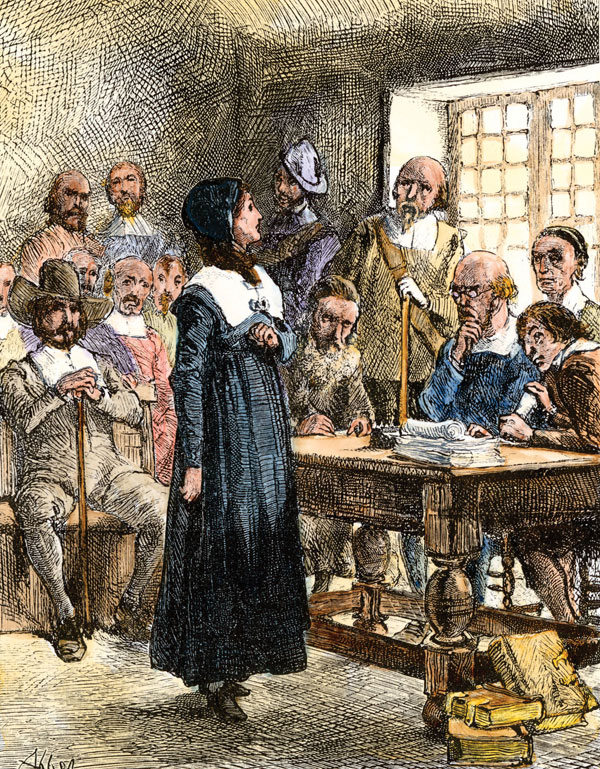

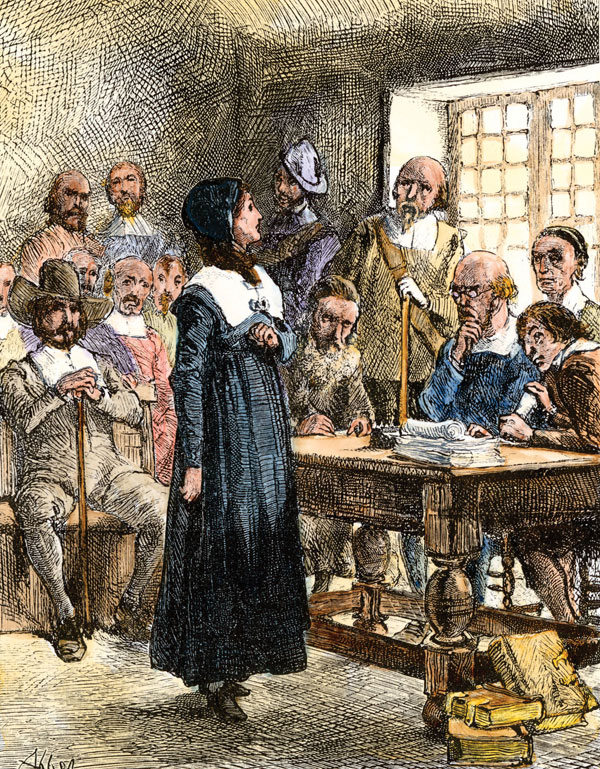

And there was Anne Hutchinson who believed herself to

be more "spiritual" than the colony's pastors – except for the pastor

John Cotton, whose favor she cultivated with breathtaking flattery.

Eventually, in 1638, she was forced to leave the colony ... before her

"prophetic pronouncements" shattered the social foundations on which

the struggling new community was built.9

9Anne

Hutchinson would become a major hero of the American feminist movement

for the way she stood up to the male authorities of the colony,

attempting merely to "exercise the right of free speech." The fact

that she created a circle of individuals who were deliberately

attacking the legitimacy of the colony's leadership with their claims

that all the pastors but Cotton were serving the Anti-Christ or Devil is a most critical social matter conveniently overlooked in the extolling of Hutchinson's "bravery."

The Trial of Anne Hutchinson - 1638

A MAJOR INTELLECTUAL SHIFT |

|

Religious Fatigue

It is impossible to overstress the importance of two factors that

played heavily in the lives of Westerners by the year 1650.

One

of these was a growing sense of relativism about revealed or divine

truth. Watching

Protestants and Catholics slaughter each other in

the name of revealed truth did nothing beneficial for cause of either

"revealed truth" in the long run. Instead it tended to scatter

the seeds of religious skepticism around the land. People were

tired of the fiercely combative religious claims on people's sense of

truth.

Consequently, the simple straightforwardness of truth built merely on

human observation and reason seemed to be a much more useful – not to

mention safer – approach to truth. The European was thus very

receptive to a worldview which grew up from the foundations of "natural

philosophy" – one that proceeded not from tradition, or scripture, or

divine revelation, but one which seemed to stand simply on observed

"fact." This was truth enough. This could even be, as in

the example of the theory of the heavens, a greater truth. The

European was thus beginning to be very open to what such natural

philosophy (the forerunner of modern science) might now be having to

say about life ... anywhere, everywhere – even in the heavens above.

The development of the secular-scientific mindset

The second factor playing a very big role in the development of Western

culture in those days was the growing interest in the immediate world

around us – the physical, secular world. Somehow there was a growing

sense that it was not a mere transient place – merely a staging area

for eternal life. Rather – it had value, great value, in and of

itself.

True, this kind of thinking had its roots as far back as the 1300s,

with its love of physical beauty found in the human form and the

natural world around us; and it developed rapidly in the 1400s during

the Renaissance in Italy and Northern Europe with the rise of the

spirit of entrepreneurship and the accumulation of personal fortunes.

But what is particularly notable about this intellectual movement of

the 1500s and 1600s was how our interest in the world around us came to

have a value in and of itself – apart from how it might help us in our

relationship with God. Not that this implied a diminished regard

for God. It's just that a new mindset was growing up – that could

consider the study of anything apart from some implicit religious

significance.

The "dethronement" of the earth

Despite the concern about the cruelty of the religious debate between

Protestantism and Catholicism, none of these new free-thinkers had any

desire to disestablish the larger matter of the Christian faith and its

general worldview. But ultimately, what they would discover in their

free-wheeling inquiry into their newly expanding universe would throw

the whole moral-intellectual-spiritual paradigm of the West into

further confusion.

The earliest upheaval came in a new view about the heavens and the

earth. But this story goes back well before 1600. Let's therefore

go back a bit and see how things evolved.

Since time immemorial it had been assumed that the earth was the fixed

center of the universe – and that the "heavenlies" (sun, moon and

stars) circled the earth – in accordance with divine law.

True – there were "fluctuations" in the heavenly movements of these

supposedly divine and thus "perfect" celestial bodies. But these

fluctuations ("imperfections") had been accounted for in numerous

sub-theories that seemed to preserve intact the original doctrine. But

these sub-theories were so complicated that it made for an almost

incomprehensible vision of the precise movements of the heavens.

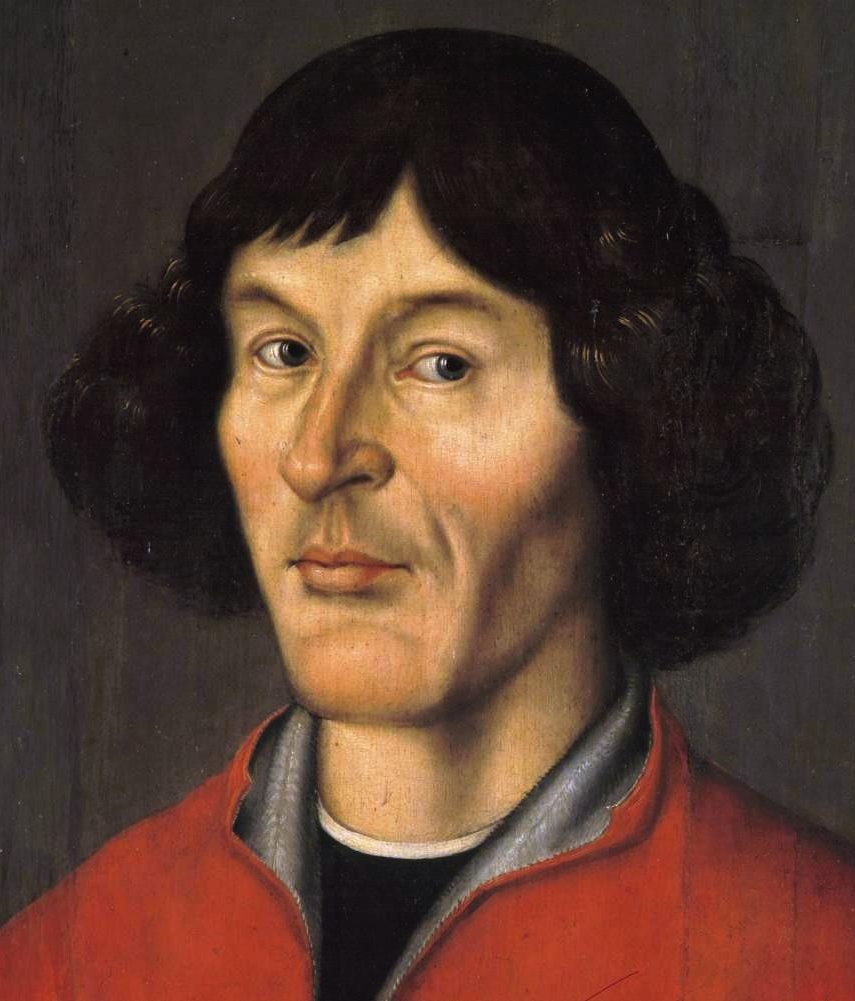

Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543) Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543)

In the mid-1500s Copernicus had come up with an alternative

theory: the sun, not the earth, is the center of the universe (he

apparently was not aware that almost 2000 years before him, Aristarchus

had also come up with such a theory).

His purpose – so his publisher states – was not to challenge the

obvious truth of the earth's centrality to the universe – but rather to

make "astrological" calculations (for the purpose of fortune-telling)

less complicated. His heliocentric (sun-centered) theory was

simply to be viewed as a hypothetical system designed to simplify

astrology. He did not intend to posit this theory as a new theory

of Truth or Reality. It was simply a device of convenience. This

anyway is what his publisher wrote in the preface, possibly to protect

Copernicus. Whether Copernicus himself thought that his theories

were or were not matters of mere convenience is much less certain.

Indeed, though his theory seemed to work, it still had many flaws – and

needed a lot of further working out before it might be significantly

better than Ptolemy's theory. As long as the motion of the

planets around the sun was seen to be perfectly circular – rather than

as was later discovered to be elliptical – Copernicus himself would

need theories and formulas and sub-theories and sub-formulas to make

his astrological calculations useful.

In his own days there seemed to be nothing particularly revolutionary

about his theories. They were interesting ... perhaps even

useful. But actually, he had put out in front of the European

mind the suggestion that the sun, not the earth, might be a better

starting point in computing the movements of the heavens. His

ideas were not forgotten.

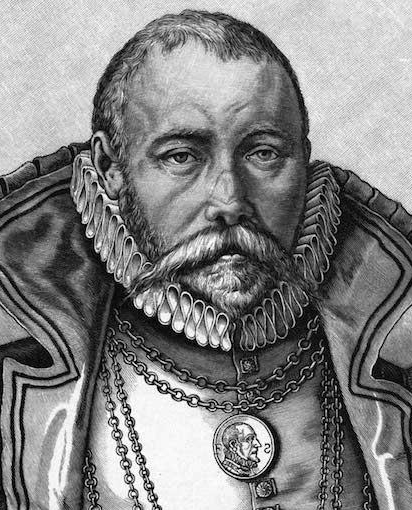

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) Tycho Brahe (1546-1601)

At the turn of that century (late 1500s/early 1600s) Tycho Brahe made

an enormous contribution to the growing field of inquiry about the

universe and the place of our world in it. He was astrologer and

mathematician for the Holy Roman Emperor. In pursuit of

astrology, he carefully collected observations about the movement of

the heavens. Though these were not intended at the time to serve

the interest of science, they would prove very useful for later

advances in the rising science of astronomy, studying the planets and

stars in order to acquire knowledge of their movements in and of

themselves – quite apart from their "fortune-telling" qualities.

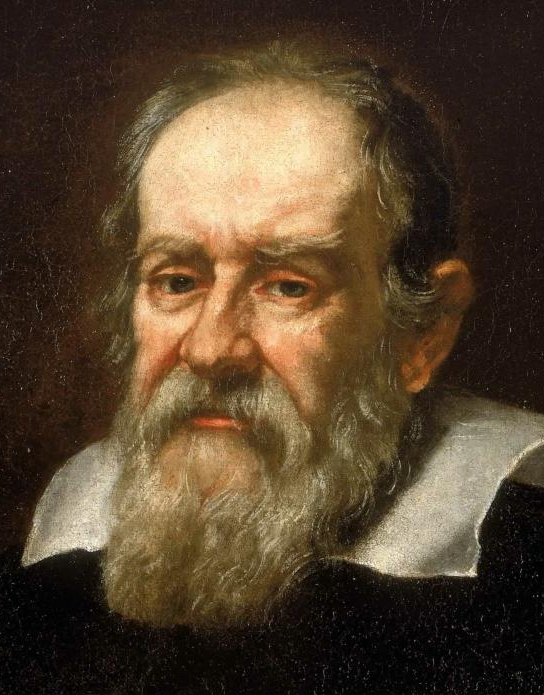

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

But still the matter was not given much weight at the time – until in

the early 1600s when it came into the hands of the Italian astronomer

Galileo Galilei. Galileo announced loudly and long that from his

direct observations of the stars, it was clear to him that the

heliocentric theory was not just a conjecture but was in fact the

Truth. Beyond a shadow of doubt, the sun – not the earth – was

the center of things.

His impact did not stop there. Galileo had been armed with a

new-fangled instrument we know as a telescope (even claiming its

invention – though it seems he fudged a bit on this truth). With

this telescope he was able to make many unprecedented observations of

the heavens beyond even the all-important fact of the earth's loss of

central position in the scheme of things. He observed the

pock-marked surface of the moon and the solar flares of the sun –

discounting the ancient Greek religious doctrine that these heavenly

bodies were the epitome of perfection (actual Platonic Ideals or Forms).

He also observed the moons of Jupiter in their regular orbit as

together they all moved about the sun – giving rise to an explanation

of how our moon could be similarly held in orbit around the earth as it

makes its way around the sun.

Also, his telescope revealed considerable mass on the part of some of

the heavenly bodies (the planets) which had appeared to the naked eye

only as points of light in the sky, demonstrating their existence as

substantial material entities: neighbors of the earth. But oddly,

even under the powerful scrutiny of the telescope, other lights in the

heavens (the stars) still remained as only points of light – giving

indication that their distance from our earth must be vastly greater

than had been previously imagined!

At first his announcement was met with much interest from the Italian

Catholic hierarchy ... which initially seemed to be quite supportive of

his studies. But Galileo was a bit of a theatrical

publicity-hound who found that his celebrity status could be greatly

enhanced by clobbering the church with the metaphysical implications of

his discoveries. In case people had not understood the

metaphysical implications of his findings, he was glad to make them

clear. Thus he was loud in his announcement that both tradition

and Scripture – hitherto considered the bedrock of all truth – seemed

to be very wrong on their placement of the earth at the center of the

universal scheme of things. Indeed, he seemed to be eager to

demonstrate every point he could find where his studies challenged

traditional authority.

But this was not a good time to insult the Church and its

truths. Europe was in the midst of the violent

Protestant-Catholic religious wars, and the Protestants were delighting

in another excuse to verbally attack the Catholic Church. As they

picked up on Galileo's threat to the traditional Christian worldview,

they attacked the Pope fiercely for his tolerance of this vile

theory. To the Protestants this was another example of how far

the leadership of the Church was willing to stray from the Truth.

As Protestant criticisms grew sharper, the Pope became increasingly

frustrated by the way Galileo's grandstanding was stirring up even more

controversy within a disintegrating Christendom. Galileo really

didn't need to press this point so much. Also the Church was

getting tired of Galileo's criticisms of its traditional

authority. A show-down between Galileo and the Church thus became

inevitable – given Galileo's personality and the Church's highly

defensive position. Eventually the Pope threatened

excommunication if Galileo persisted. For Galileo, grandstanding

was one thing, excommunication was quite another. So Galileo