9. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DYNASTIC STATE

EUROPE DURING THE SECOND HALF OF THE 1600s

CONTENTS

France under the "Sun King" Louis XIV France under the "Sun King" Louis XIV

(1643-1715)

Continuing turmoil in England Continuing turmoil in England

Secular philosophy continues to develop Secular philosophy continues to develop

Problems accompanying the "maturing" Problems accompanying the "maturing"

of Colonial America

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 363-380.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

1643 Cardinal Mazarin governs France when 4-year-old Louis XIV becomes French king

1648 The Treaty of Westphalia gives Europe's monarchs full or absolute power to assign

religious preferences to their kingdoms ... sparking resentment of the

lesser lords

1649 Puritans behead Charles I and establish a Puritan Commonwealth ... headed by Oliver Cromwell

1652 Jan van Riebeeck establishes for the VOC a Dutch Colony at the South African cape

1653 Louis XIV crowned officially as King of France (Mandarin still serving)

1653 The Russian Zemsky Sobor (parliament) declares war on the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth ... with Russia claiming the Eastern

half of Poland

1655 Sweden attacks the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ... taking the Western half of Poland

1658 Cromwell dies; his son Richard takes over ... but lacks essential military backup to his rule

1659 Richard is driven from power and George Monk works to restore Stuart rule in England

1660 The (High Anglican) Stuart monarchy is restored under Charles II

1661 Mazarin dies; Louis XIV becomes sole or absolute ruler of France

1668 The Portuguese rebel against Spanish authority, ending the Spanish-Portuguese union

1669 Locke designs for Shaftsbury Fundamental Constitutions for the colony of Carolina ... outlining a "proper" class structure and accompanying lay of the land

for the colony

1672 The French and the English engage in war against the Dutch ... William III of Orange able finally to fend off the French and English – with all parties deeply exhausted (1674)

1677 Dissatisfied Virginia frontiersmen and workers – led by Nathaniel Bacon – revolt against

the hierarchy of privilege ruling Virginia; but Bacon dies and the

revolt collapses

William marries his cousin Mary Stuart (both Charles I's grandchildren)

1685 Louis XIV revokes the Edict of Nantes ... 200,000 Huguenots soon fleeing France

Charles II dies; his pro-Catholic brother James II takes the throne

1687 Isaac Newton publishes Principia ... seeing all of life as a precise combination of tiny

atomic particles functioning fully mechanically (a Creator God no

longer involved)

1688 James II allies with Louis XIV ... sparking a Protestant reaction in England ... with William

responding by leading Dutch and English Protestants agains James ...

who flees

1689 Parliament declares William and Mary as co-regents of Great Britain

Locke's Two Treatises of Government defines a social "state of nature" in which equlity,

protected rights (life, liberty and property), and support of the

people are essential to any "good" society

1690 Locke's Essay on Human Understanding sees human thought as simply the mechanical working

of the human brain ... responding and growing in knowledge as it

encounters

the world in practical ways (empiricism)

1690s Numerous English publications presume to "save" Christianity from supestition by making it more

rational or "natural" (ending divine actions as part of the dynamic)

1692 A witch hunt breaks out in Massachusetts ... influenced by increasingly Secular thinking that can

make no sense of unresolved social problems; Puritan authorities

finally bring the witch hunt to a stop the next year (1693)

1694 Mary dies ... leaving William as sole ruler of Britain (until his death in 1702)

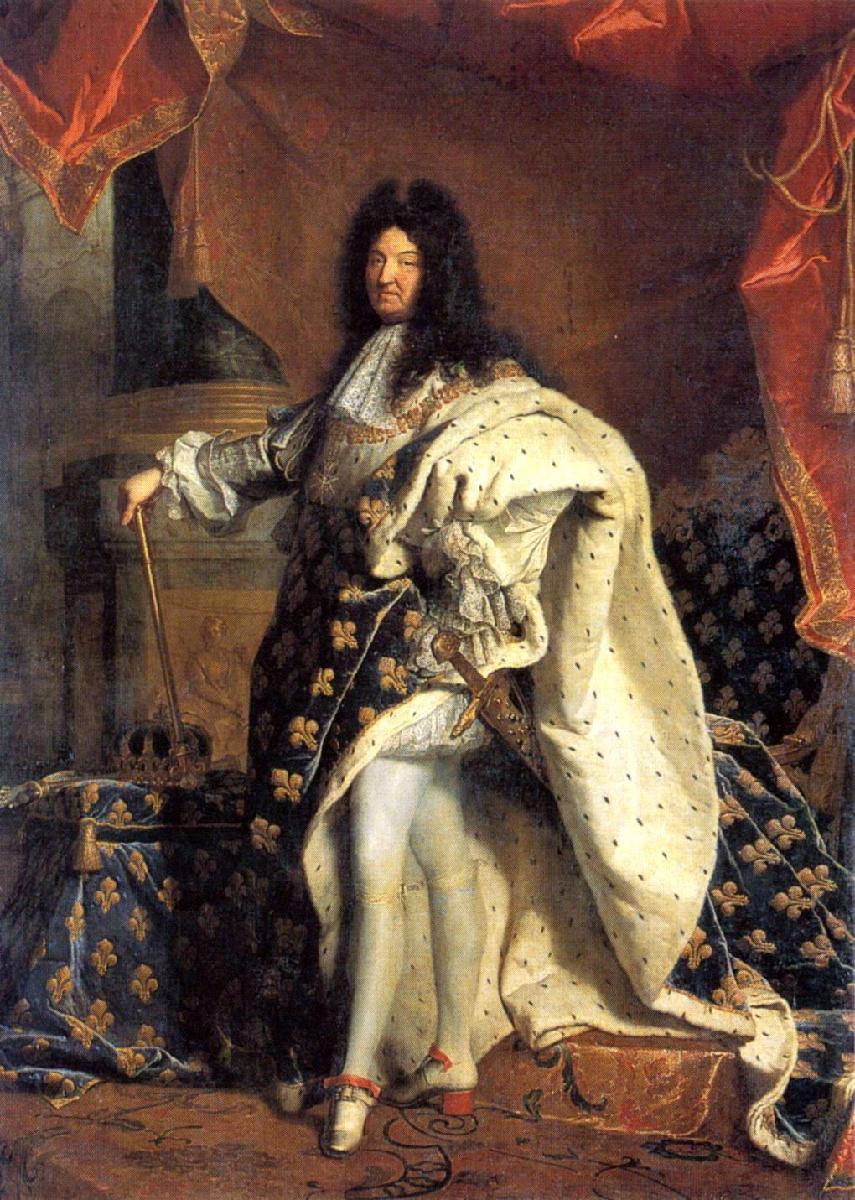

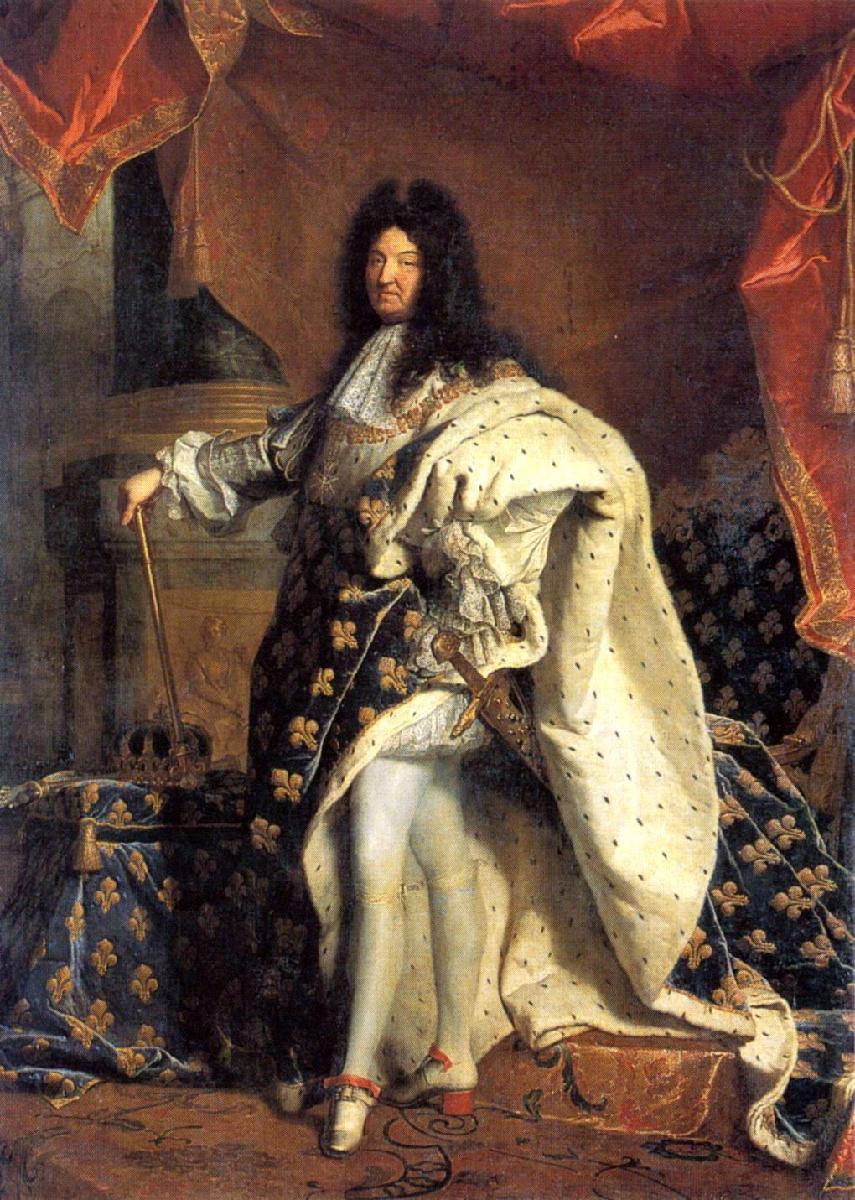

FRANCE UNDER THE "SUN KING" LOUIS XIV (1643-1715) |

As

the 1500s was clearly the age of Habsburg Spanish domination (under

Charles and his son Philip) in Europe, by the end of the 1600s it was

clear that Bourbon France under Louis XIV was the dominant power in

Europe. Not only did Louis's armies manage to hold off European

grand alliances formed against his growing power, but his court with

all its particular French refinements became the model that virtually

every other European monarch attempted to emulate in one fashion or

another. As

the 1500s was clearly the age of Habsburg Spanish domination (under

Charles and his son Philip) in Europe, by the end of the 1600s it was

clear that Bourbon France under Louis XIV was the dominant power in

Europe. Not only did Louis's armies manage to hold off European

grand alliances formed against his growing power, but his court with

all its particular French refinements became the model that virtually

every other European monarch attempted to emulate in one fashion or

another.

Louis got off to a very rough start. He was only four in 1643

when his father Louis XIII died, leaving France in the hands of a

regency under Queen Anne, who was aided greatly by another politically

skilled clergyman, Cardinal Mazarin. With the king so young there

was always political intrigue going on by various noblemen attempting

to take advantage of the situation. Twice Louis and his mother

had to flee Paris and once both of them were even put under something

like house arrest in their Paris palace (the Louvre).

Cardinal Mazarin had his hands full trying to keep Louis and his mother

from falling victim to all the political intrigue that swirled around

the two of them.

The Fronde and royal absolutism

A big part of the problem arose from the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia to

which Mazarin had been a major contributor. The Treaty contained

an agreement among European powers assigning rather absolute religious

(and thus political) powers to the ruling royal families of the various

states involved in the treaty, empowering the sovereign rulers alone to

determine which religion – Catholicism or Protestantism – would be

practiced in their lands.

The noblemen of France realized that in assigning such an important

power to the sovereign kings (and other heads of state) this took away

traditional feudal rights of the lesser nobility. Thus there was

a general revolt (the Fronde) of the French noblemen (including even

close relatives of the young king) against French royal authority,

authority promoted and protected by Mazarin. In theory the revolt

was aimed at Mazarin, not the king. But with the formal crowning

of the young king in 1654, that excuse no longer could be justified, as

Louis stood strongly with the terms of the Treaty. Thus the

revolt lost its justification and soon died away. From 1654 until

he died in 1661, Mazarin held off further attacks on the king's powers

... adding to those powers here and there as he went along.

Then with Mazarin's death, Louis was ready to take control of the

affairs of state entirely on his own. He would make all the

decisions, large and small. He made it clear that noblemen and

other court officials existed only to carry out his orders. And

thus Louis XIV began his rule of royal absolutism.

Life at the Palace of Versailles

Louis moved his court out of a dangerous Paris to the nearby suburb of

Versailles – and then required the entire French nobility to move there

with him to his new, enormous palace ... so that he could keep a close

eye on them. He lavished his "guests" with endless banquets,

balls, musical recitals, plays, etc. – to gloss over the reality that

they were in fact something like prisoners there. But since there

was little they could do to escape their situation, they made the most

of it. In fact the proceedings at the Versailles Palace were so

elaborate (and the logic behind it so very clear) that other sovereigns

began to copy closely the political and cultural style of

Versailles. And thus it was that French culture (and politics)

came to be the standard for the ruling classes in virtually all of

Europe.

The endless round of dynastic wars over European land rights

While other sovereigns honored Louis by mimicking him culturally, they

fought him fiercely politically or militarily. It was always

about land: who won it, who lost it. Land could change hands

among Europe's sovereigns peacefully, such as in marriage where the

exchange of lands accompanied the exchange of wedding vows. But

most land holdings changed hands simply through fights over it ...

territorial title changing back and forth from one sovereign to another

as the fortunes of war shifted back and forth. Louis and the

other kings were constantly involved in wars, great and small, in an

attempt to expand their territorial holdings. It was a confusing

and draining process that occupied Louis until his death in 1715.

The revoking of the Edict of Nantes (1685)

and the flight of Huguenots out of France

The ongoing existence of communities of Protestants in his Catholic

France was a major irritant to Louis. And thus he set out to

bring religious uniformity (as per the Treaty of Westphalia) to

France. He began the process almost immediately after

assuming full royal powers in 1661. He harassed the Protestant

Huguenots in every way possible, banning worship, destroying churches,

closing schools, and placing his rough-edged troops in Protestant homes in order to

break their spirit. And hundreds of thousands of Huguenots did

break, finding it prudent to convert to Catholicism.1

Finally in 1685 he made a full move against Protestantism, issuing the Edict of Fontainebleau – declaring

any further toleration to have come to an end. Although it was

also very illegal to leave his realm without royal permission, perhaps

as many as 200,000 Huguenots fled France for Protestant lands in Europe

and elsewhere ... taking with them the valuable entrepreneurial and

professional skills that naturally arose from their Calvinist

mindset. Other sovereigns (notably the Protestant variety) were

shocked by Louis's behavior. But they did little to counter

it. They were in fact quite glad to receive these talented

refugees. Nonetheless, even as cruel as it was, expelling the

Protestants finally brought religious harmony to France.

Louis's legacy

Louis came to the throne with the royal treasury virtually empty, then

under the direction of his economic advisor Colbert had it restored ...

then Louis bled it dry again over the years with his countless

wars. He refashioned French politics so tightly around his

personal will that if future kings were not made of the same grit as he

was, they would have big troubles maintaining control. And that

is exactly what happened.

On the positive side, he made French language, learning and culture the

European standard for many future generations. He also advanced

the boundaries of France all the way up to the Rhine River in Germany

and incorporated Flanders into the French kingdom, along with a number

of other smaller acquisitions. And he sponsored further French

exploration in America: through Jesuit missionaries and explorers

such as La Salle he was able to lay claim to vast amounts of American

territory from Canada in the north to the Gulf of Mexico in the South,

from the Appalachian Mountains in the East, across the Mississippi

River to its far sources in the West. The vast area below French

Canada was in fact named after him, Louisiana.

1A

group of Huguenots were able to hid themselves in the isolated

mountains of Auvergne in Southern France … and maintain their

Protestant faith in doing so. They were also the community that

was able to help over 3,000 Jews hide in their town (Chambon) and thus

avoid the Nazi deportation of French Jews (some 80,000 were deported)

during World War Two … these brave Huguenots (brave because the penalty

for helping Jews escape deportation was death) having themselves

learned how to avoid detection by the French authorities all those

years!

Louis XIV - by Hyacinth Rigaud (1701)

Louvre Museum - Paris

Cardinal Jules Mazarin - by Pierre Mignard (c. 1658)

Colbert was Queen Anne's advisor during Louis's regency (1643-1651)

and then during Louis' XIV's early years as king (1651-1661)

Musée Condé - Chantilly

Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1665) by Philippe de Champagne

Colbert was Louis's advisor (1661-1683) after Mazarin died in 1661

Metropolitan Museum of Art - New York City

The Fronde rebellion (1648-1653) ... of the nobility, courts and many commoners against the Bourbon royalty ...

because of the absolute power (political, economic as well as religious)

assigned to Europe's kings in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia

300 Huguenot families leaving La Rochelle under Louis's persecution - November 1662

La Salle claiming the lands at the mouth of the Mississippi (Louisiana) for France - 1682

CONTINUING TURMOIL IN ENGLAND |

|

The Puritan Commonwealth (1649-1653)

With the beheading of Charles I in 1649, the Rump Parliament declared

England, Scotland and Ireland to be no longer royal territories but

instead parts of a new Republic ... or in Anglo-Saxon terms, a

"Commonwealth." The House of Lords was abolished as part of

Parliament and a Council of State took over the executive

responsibilities of the new government. But actually relations

between the members of the Rump Parliament running the new government

and the army (at the time engaged heavily in putting down royalist

resistance) was not an easy one. It was, after all, the army that

had put the Rump Parliament into power in the first place ... and the

army – especially under Cromwell – seemed to take a great interest in

directing English (and Scottish and Irish) politics according to its

own interests.

Also political interests varied widely within the Rump Parliament ...

some MPs wanting a government of a most definite republican nature and

others still believing monarchy to be the most appropriate form of

government for England. But in moral and spiritual terms the Rump

Parliament was more united in wanting to see the country reformed under

Puritan ideals ... especially in the matter of closing down theaters

(considered the source of lewdness) and the requirement of Sunday

church attendance (although a variety of religious denominations was

nonetheless permitted). Neither of these moral "cleansings" of

English society however were designed to win the hearts of most

Englishmen – who enjoyed a rather looser moral life!

Domestic reforms

Actually, true political reforms proved to be few once the king had

been eliminated. It was mostly lesser gentry that stood behind

the Commonwealth ... and they were not interested in serious economic

reform, especially of the variety demanded by the "Levelers" who wanted

full equality for all, economically and politically. Mostly the changes

that could be felt through England under the Commonwealth were in the

form of the rigid moral order which descended on England, such as the

closing theaters (considered dens of lewdness by the Puritans) and the

requiring of strict Sunday observance. This was something not

likely to endear most Englishmen, who enjoyed a rather looser moral

life. Worse, heavy taxes had to be imposed on the citizenry to

pay for the wars which went on constantly during this brief time period.

The Irish Rebellion

Most importantly, Cromwell faced challenges to the Commonwealth in both

very Catholic Ireland and very Presbyterian Scotland. He set

about the task of reducing the resistance of Ireland, brutally vengeful

against Drogheda and Wexford (as revenge for the massacre of Protestant

settlers who had earlier come from Scotland in Northern Ireland) ...

though for the most part of the rest of his conquest of Ireland (and in

the context of the times of the Religious Wars) he was fairly merciful

to the towns that did not offer opposition. Nonetheless when he

was called back to England to take on the Scottish problem the next

year (1650), his subordinate officers continued the campaign – on a

much less merciful level2 – earning Cromwell the eternal hatred of the Irish.

The Scottish Rebellion

Meanwhile in Scotland things underwent confusion as at first the

Royalists tried to raise the Catholic Highland clans against the

Lowland Covenanters (Presbyterians) ... but failed miserably in the

effort. Then the Royalists joined the Covenanters under the

renewed Royalist promise of instituting Presbyterianism generally

within the royal realm.

At this point Cromwell left Ireland to deal with the Scots. Here

too he was as determined a foe ... though conducting his campaigns so

that the ravages of war there were greatly reduced. Scottish

resistance was thus less intense ... and he soon succeeded in crippling

the Royalist threat there.

But Charles II in the meantime (1651) had moved his army south from

Scotland to England. Thus Cromwell went in pursuit of Charles,

leaving George Monck to clean up the last of the Scottish resistance...

which collapsed fully in 1652.

In September of 1651 Charles's Royalist forces and Cromwell's Puritan

forces met at Worcester ... where Charles's forces were completely

routed – forcing Charles to flee to France.

Cromwell's Protectorate (1653-1659)

In 1653 Cromwell simply dismissed the Rump Parliament and took direct

control of English politics ... supported by a small "Barebones

Parliament" (composed of representatives elected by local

congregations) which he expected would come up with specific reforms –

but possessed very little political expertise and subsequently was

dismissed by Cromwell after only a few months of service.

It was at this point that a Cromwellian Constitution was put into

force, making Cromwell "Lord Protector" for life (thus something like a

king), and restoring the role of Parliament and the executive Council

of State. But the real power in England remained Cromwell's loyal

army ... and the military governors he appointed to preside over

Scotland and Ireland.

At this point peace returned to the land (though anguish in Ireland

continued ... and the Scots were always on the edge of rebellion ...

which Charles II from his exile in France was watching closely).

One of the big events of the time was in fact a commercial war with the

Dutch ... fellow Protestants, but fellow competitors in the important

world of international commerce.

Richard Cromwell ... and the demise of the Commonwealth (1659)

In September of 1658 Cromwell suddenly became quite sick and died

(urinary infection most likely) ... and – in royalist fashion – his

office as Lord Protector was directly taken up by his son

Richard. But Richard enjoyed no power base of his own (as his

father had with the army) and thus he had no leverage by which to

control the many political factions that constantly vied for power in

Parliament. Richard was soon (May of 1659) driven from power by

one of the faction leaders.

Monck takes command

With the political situation deteriorating rapidly, General George Monck left

his position as Scottish Governor and marched with his army on London

(January-February 1660) and placed the original Long Parliament back in

power. And Monck and the MPs then took up the work of negotiating

with the exiled Charles II concerning the restoration of the English

monarchy, by this time desired by most of the English. Terms of pardon

and compensation were agreed on and in May a newly reconvened

Parliament invited Charles to retake the throne of England.

The Stuart "Restoration" (1660)

By

the end of May Charles was back in England, the following April (1661)

he was formally crowned King (though in effect he had been governing

the country since his return the previous year), and in May the

Cavalier Parliament that would rule England for the next 17 years was

fully in power. The Puritan experiment was over ... as well as

England's only attempt at Republican government. Indeed, England

– like the war-weary European continent after the long period of the

Thirty Years' War – was ready to enter a new era of peace.

2Tens

of thousands of Irish were subsequently shipped off to Bermuda and the

Caribbean islands to live in servitude there; and possibly as much as

nearly half of the Irish population ultimately died of exposure, hunger

and disease because of the intentional ravaging of the Irish

countryside by Cromwell's generals (designed to break the will of the

Irish) in the years after Cromwell's departure for England.

Oliver

Cromwell - by Samuel

Cooper

Oliver

Cromwell - by Samuel

Cooper

Head of the English Puritan Commonwealth (1649-1659)

National

Portrait Gallery,

London

Cromwell's New Model Army defeats a Scottish army

twice the size of his force at the Battle of Dunbar (September 3, 1650)

General George Monck - Cromwwell's Governor of Scotland - negotiates the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy under Charles II in 1660

|

The Dutch and the English

These two societies at this point are discussed together because during

the latter part of the 1600s their destinies seemed so intertwined ...

in peace and in war. Both being rising sea-powers, their disputes were

largely commercial. Both being a mix of Protestant and Catholic the

dynastic disputes that focused on the matter of religion required them

to be very flexible in their handling of these disputes. In general,

they moved cautiously through the thicket of religious-dynastic feuds.

But when they did not, the results were calamitous.

England during the "Restoration"

The

grand experiment in Puritan republicanism had died a quiet death, with

few seeming to mourn its passing. However, Charles's situation as

"restored" king was still precarious. He had the support of the

aristocratic "High-Church" or Episcopalian Cavaliers in Parliament ...

but had to work with the Presbyterians who occupied an equally strong

position in Parliament. The

grand experiment in Puritan republicanism had died a quiet death, with

few seeming to mourn its passing. However, Charles's situation as

"restored" king was still precarious. He had the support of the

aristocratic "High-Church" or Episcopalian Cavaliers in Parliament ...

but had to work with the Presbyterians who occupied an equally strong

position in Parliament.

Political intrigue swirled around him all his

days ... in part brought on by his wanton ways. He kept a seemingly

endless string of mistresses – who bore him numerous illegitimate

children (who would become nobles of the realm nonetheless) – in

contrast to his Portuguese wife, by whom he gained valuable Portuguese

territory ... but no living offspring.

Advisors rose and fell at the rate that they succeeded or failed in

public policy, which was frequent given all of the dynastic wars going

on that invited Charles" participation. All this confusion merely

encouraged the court intrigue which Charles seemed unable to control.

He dissolved Parliament again and again to try to gain increased

support for his rule, but to no particular avail. Parliament remained

divided between Tories and Whigs3 over a piece of legislation making it

illegal for a Catholic (such as Charles" brother James) to inherit the

throne of England. Finally during the last years of his life he

attempted to rule without Parliamentary support (a difficult matter

since it was from Parliament that he received his "supply" in the form

of approved taxes).

William III of Orange and the Dutch Republic

William was the son of William II, the Dutch Prince of Orange, and

Mary, the eldest daughter of Charles I King of England. Charles II had

taken refuge in the Netherlands with his cousin William II during the

years of Cromwell's Commonwealth, and William supported him strongly in

his exile. But William II died in 1650 after only a few years of

service as Stadtholder (something like "President") of the Dutch

Republic ... one week before the birth of his son William III.

During William III's youth, the Dutch and the English engaged in

commercial conflicts4 as they both attempted to extend their commercial

privileges to various places around the globe. They also found

themselves involved in the competing dynastic alliances formed across

Europe.

William found his rise to the position of his father as Dutch

stadtholder blocked by a number of political opponents in the Holland

province, and William appealed to his English uncle Charles II for

assistance in advancing his cause. But he did not know that his uncle

had secretly agreed to an alliance with France ... directed at the

Dutch Republic. Charles actually believed that defeating the Dutch in

war was also the proper way to force the Dutch to accept William.

William would have none of it when he figured out what was going on.

In any case, the Franco-Dutch and Third Anglo-Dutch War broke out in

1672. The Dutch were at first devastated by this French-English

combination. William was finally appointed stadtholder of key Dutch

provinces, and refused to surrender to the English, even when the offer

of dynastic rule over the Netherlands was offered in compensation. The

Dutch flooded their low-lying fields ... and with that the French

overland invasion came to a halt. The English then quickly lost

interest in continuing the conflict. Thus the war ended in 1674. But

it had been very hard economically on the Dutch society.

Then William moved to marry his young English cousin Mary, daughter of

James of York, Charles II's brother (1677).5 He did so in the hope of

improving relations with the English ... and strengthening his own

claim on the English throne as Charles I's grandson.

The Glorious Revolution (1688-1689)

This question of who would inherit the throne of the childless Charles

II at his death troubled England greatly. Next in line was his

brother, James, Duke of York, an avowed Catholic. The effort to pass

an Exclusion Act had been aimed at him ... in order to prevent him from

inheriting the throne. Nonetheless when in 1685 Charles died, his

Catholic brother James became King of England as James II (and Scotland

as James VII). It was also the year that Louis XIV revoked the edict

of Nantes, driving hundreds of thousands of Huguenots from France.

This question of who would inherit the throne of the childless Charles

II at his death troubled England greatly. Next in line was his

brother, James, Duke of York, an avowed Catholic. The effort to pass

an Exclusion Act had been aimed at him ... in order to prevent him from

inheriting the throne. Nonetheless when in 1685 Charles died, his

Catholic brother James became King of England as James II (and Scotland

as James VII). It was also the year that Louis XIV revoked the edict

of Nantes, driving hundreds of thousands of Huguenots from France.

Much of Protestant Europe was up in arms about this revoking of the

Edict of Nantes – reactively forming something of a Grand Alliance

under Dutch Protestant William of Orange's leadership. When in the

spring of 1688 James II concluded a naval agreement with Louis XIV,

suspicions mounted quickly in England that this was the prelude to a

formal pro-Catholic English-French military alliance.

Then when James's

Italian-Catholic wife, Mary of Modena, delivered a baby boy in June of

that year, it appeared

that England was in line eventually to inherit a Catholic successor to

the throne. A group of English Protestants agreed with William

that it was

time to act. Soon a coalition was formed against James II and his

close ally Louis

XIV, which included, at least indirectly, the strongly anti-French Holy

Roman (Austrian)

Emperor and the Pope! Louis took the first action – which then

erupted

into full scale war.

Now it was the turn of William to act. He quickly gathered a huge

Dutch naval invasion force – to which James responded rather feebly.

With William's landing in England, noblemen began declaring themselves

as "Whigs" for William. James began to loose courage quickly, fearing

even the loyalty of his own "Tory" army. Defeat in small skirmishes

and growing anti-royalist or Whig rioting in England's cities decided

him to flee to France in mid-December. But he was caught before he

could complete his escape and was returned to London. However William

did not want the responsibility of taking personal action against his

father-in-law James. Clearly, the best strategy was to allow James to

again "escape" to France. And so at the end of December James slipped

off to France to become an exile living there as the guest of Louis XIV.

William and Mary

Parliament quickly (February 1689) empowered

William and his wife Mary to rule as joint sovereigns – under the

authority of Parliament. It also passed a Bill of Rights (December

1689) clarifying the rights and powers of Englishmen and their

government. England still had a monarchy (which it does even to this

day) but it was in fact under Parliament's unquestioned sovereignty.

Thus to the Protestant point of view, this was indeed a "Glorious

Revolution."

Only five years later (1694) Mary died childless ... and William

continued as both King of England and stadtholder of the Netherlands

until his death in 1702. The followers of the exiled James (the

"Jacobites"), encouraged by the active support of Louis XIV, refused to

accept William's title and undertook rebellions in Scotland and Ireland

– and an assassination attempt – all of which failed ... but which

nonetheless constantly troubled the first ten years of William's

reign. Along with this was an ongoing war with France that occupied

much of William's time, keeping him abroad in Europe on military

campaigns. But he succeeded importantly in blocking much of the

limitless ambition of Louis XIV which had the rest of Europe constantly

up in arms.

William III William III Mary II

Mary II

3These

were terms of contempt that one party assigned to the other:

Tories, the name for Irish Catholic bandits, assigned to those who were

opposed to anti-Catholic "Exclusion,” and Whigs, the name first for

Scottish horse thieves and then later for Scottish Presbyterian rebels,

assigned to those favoring Exclusion!

4The First

Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654) occurred during the time of the Puritan

Commonwealth. The Dutch lost over a thousand of their merchant

ships and thus sued for peace. But Dutch power was by no means

broken. The Second Anglo-Dutch War broke out in 1665 during the

early years of Charles II's reign. It was a more balanced

conflict, with the English gaining New Netherland (New York), but

losing a major naval battle, bringing the war to an end in 1667.

5Although her

father James was a Catholic, Mary and her sister Anne had been

carefully brought up under their grandfather Charles I's orders as

Protestants.

Charles II - King of England, Scotland and Ireland (1660-1685)

Charles II - King of England, Scotland and Ireland (1660-1685)

Battle of Texel (August 21, 1673) during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674)

James II of England, Scotland and Ireland (1685-1688)

William of Orange - English King as William III

1689-1702

portrait

by Sir Godfrey Kneller

National Galleries of Scotland

Mary II Stuart - by Peter Lely (1677)

The arrival of William's Dutch navy begins the "Glorious Revolution" - 1688

SECULAR PHILOSOPHY CONTINUES TO DEVELOP |

|

The Refinement of the Mechanistic/Materialistic Vision of Life

Meanwhile,

the work of studying the physical structure and behavior of the

surrounding physical world continued to move ahead – especially in

England which led the way in the new "empirical" or scientific study of

our world.

It was the age of mechanical clocks, precision telescopes and sextants,

mechanical war-machines, and other such useful instruments. It

was the age which reduced the movement of the heavenlies to a precise

mathematical formulation. It was the age which began to look at

life as a precise "natural" composite of various material elements –

physical and chemical. It was an age which was thrilled by the

idea of unlocking all the mysteries of "natural" life by bringing such

life (seen more and more in mechanical/materialist terms) under precise

intellectual formulation. It was an age of heady "natural

philosophy" and "natural philosophers" (the name given to the

scientists of the 17th century).

This was particularly the case in England which led the way in the new

"empirical" or scientific study of our world – such study eventually

termed "positivism. " In 1660 the Royal Society was founded, bringing

this new breed of "natural-philosophers" (as they saw themselves)

together to encourage each other in their work.

In the latter part of the 1600s one of these English naturalists, Isaac

Newton, picked up on Descartes' theories of motion and completed the

mechanistic vision of the universe that Descartes had laid out.

In Newton's Principia (1687)

he so thoroughly pulled the mechanistic/materialistic vision together

that it became the single most important foundation piece for the

modern world-view.

In the latter part of the 1600s one of these English naturalists, Isaac

Newton, picked up on Descartes' theories of motion and completed the

mechanistic vision of the universe that Descartes had laid out.

In Newton's Principia (1687)

he so thoroughly pulled the mechanistic/materialistic vision together

that it became the single most important foundation piece for the

modern world-view.

Following

the ancient thinking of Democritus and the atomists, he "demonstrated"

that all things within the universe were made up of minute bits of

matter. There was something absolute or eternal about the

existence of these particles: once created by God, they remained

in permanent being. They did, however, combine and recombine into

different elements, which in turn combined into different physical

forms of matter. But Newton asserted that while the larger forms

of life changed, the atoms themselves did not. They were

unchangeable, possibly even eternal in their being.

These tiny particles were held together in their shape and movement to

take the forms we see before us through the force of natural attraction

or gravity (the gravitational attraction of two bodies is equal to the

product of their mass divided by the square of the distance between

them).

This theory appeared to explain quite fully everything from the

movement of the planets through the skies, to the movements of the

tides, to the velocity of falling objects – and more.

Just as importantly – the completeness of the theory left no

possibility of seeing creation as a "living" thing. Creation was

without life of its own; it was instead mere "matter" responding

mechanically to a set of fixed mathematical laws.

Newton depicted God in such a way that God actually lost "personality"

and the realm of sovereign action. God was left a role in nature

largely as "First Mover" or original architect of this mechanistic

universe, with no further significant intervention in life. God

became identified with the eternity or infinity of the universe.

Deism was being born.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

Leibniz was a German mathematician and rationalist philosopher – who,

simultaneously with Newton, invented the differential and integral

calculus. He was a widely talented and traveled individual – and

kept up friendships and correspondences with a wide range of

scientists, philosophers and political figures of the day.

Leibniz was born and educated in Leipzig, eventually studying law at

the University of Leipzig. From 1667 to 1672, he worked for the

Elector of Mainz as a lawyer and diplomat.

He traveled widely coming into close contact with a number of political

and scientific luminaries of his day. In 1672 he traveled to

Paris where he came into contact with Huygens and Malebranche.

His travels also took him to England (1673, 1676) and to Amsterdam

(1673), where he spent time with Spinoza. During these days he

began his work on calculus.

In 1676 he went to work as a librarian to the Duke of Brunswick, and

took up work on a number of mechanical devices that utilized his

mathematical and technical talents. But he also turned his

attention to philosophy, completing works on metaphysics and systematic

philosophy during the 1680s and 1690s.

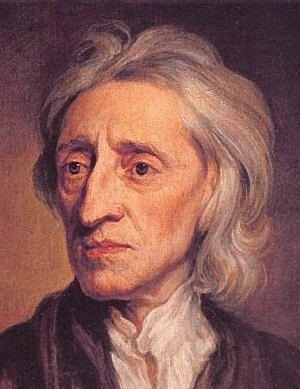

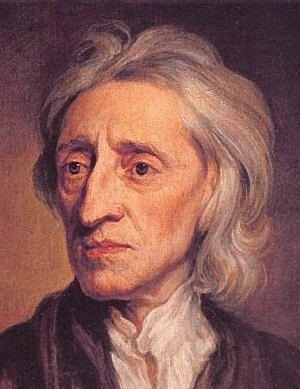

Very shortly after Newton's Principia was published, another

Englishman, John Locke, published his Essay on Human Understanding

(1690). Very shortly after Newton's Principia was published, another

Englishman, John Locke, published his Essay on Human Understanding

(1690).

Locke's psychology.

Locke brought the human mind into this mechanical world by positing a

theory of knowledge in which the mind at birth is simply a blank

receptacle, possessing no "innate" ideas. Over the years the mind

has data added to it from the outside world. This comes in the form of

"sensations" that strike this blank mind through the sensory devices of

sight, hearing, feeling, taste, and smell. These data in turn are

developed into full ideas by the mechanism of the mind, which sifts

this imported information in the search for the agreement or

disagreement of two thoughts or ideas. From this mental process

develops a well-articulated vision of the world around us – and its

causes and effects.

As far as "moral" ideas were concerned, Locke felt that prudence and

long-term self-interest would serve the rational mind as the determiner

of human action.

This theory of human knowledge stood in strong distinction to the

traditional understanding that the mind possessed fully – even at birth

– a vast store of innate understanding that was vitally a part of its

soul quality. The old theory accounted for "learning" by seeing

the task not one of inserting information from the outside (as per

Locke – and almost every Western educator since), but instead one of

drawing out (thus the ancient word "education" which means "draw out")

the wealth of innate understanding already present in the human

soul. One didn't make discoveries about things "out there."

A person made discoveries about things already located deep down inside

oneself.

Though Locke's theory could offer no hard evidence that what he

hypothesized was indeed true – the time was ripe for such a

theory. "Science" was rapidly stripping life of the sense of

"soul" or "sacredness" to it. The wars of religion had also

helped immeasurably. So Locke's theory "made sense." That

was all that was needed to leave a lasting impression on the rapidly

shifting world-view of the West.

Locke's social science.

Furthermore ... Locke employed his scientific methodology not only in

the explanation of workings of human thought and action, he employed

the same methodology in the explanation of what might be termed "social

dynamics." Locke was pleased to discover that societies too

worked according to a number of basic principles ... which careful

study revealed quite clearly to be behind all social action. And

these principles, once understood, could be used scientifically to

improve dramatically the mechanics of social behavior. In other

words, society itself could be – in fact, should be – reformed through

the rising principles of science ... obviously a process that should be

directed by those with the knowledge of just those principles (such as

Locke himself)!

Thus "social reform" by enlightened individuals came to be understood

as making much more sense than waiting patiently for God to intervene

to put troubled societies back on the road to health and progress.

Locke's "Grand Model" for the Carolina colony. So it was that

Locke was called on by his personal patron (and Britain's Chancellor of

the Exchequer – the second most important political position in the

King's cabinet) Baron Anthony Ashley to put together a structural plan

for the new Carolina colony in America. This new colony offered

the perfect opportunity to construct a society that actually worked

according to the laws of social science.

Thus it was that in 1670 Locke came up with what was termed "The Grand

Model." This plan included not only The Fundamental Constitutions

of Carolina but also the physical designs for the actual settlement of

the colony. Thus were detailed some 120 principles designed to

make the colony indeed a "Grand Model."

Basically, it followed English principles of social structuring in

terms of class, property allotments, and the political rights accorded

each level of society ... ranging from Black slaves and property-less

Whites – all the way up to the largest landowners (who were naturally

the eight Lords Proprietors themselves).

The problem was that Locke knew very little about the actual lay of the

land in the new colony, the social traits of those who would actually

be taking up residence in that colony, and the matter of the Indians

and their own sense of property rights. Needless to say, the

Model proved to be beautiful on paper ... but of limited use in

actually moving the Carolina settlement forward. Consequently,

although the Grand Model would remain in place, it would have to be

amended or updated numerous times.6

Social design for England.

But Locke would be given yet another opportunity to put forward his

views on the shaping of a more enlightened society ... when England's

Glorious Revolution broke forth in 1688. In 1689 Locke published

(anonymously at the time) his Two Treatises of Government,

the first treatise critiquing the social science of Sir Robert Filmer,

the second treatise being Locke's own "Essay Concerning the True

Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government."

Of course events in England were taking their own political course at

the time. But Locke's work would be used frequently to justify

"scientifically" some of the developments of the day. And

it would serve as something of a Bible for future "social reformers" –

such as Thomas Jefferson in his drafting of America's Declaration of

Independence.

For more on Locke For more on Locke

Benedict

(Baruch) de Spinoza (1632-1677)

Spinoza

was born of Jewish parents who had escaped the Inquisition in Portugal

by coming to Amsterdam where Baruch (Latin: Benedictus) was

born. Spinoza was a very unorthodox thinker--and his ideas

eventually got him expelled from the Jewish community (1656).

Because he saw God as present in everything – as the source and essence

of all substance – he was viewed variously as a pantheist, a

materialist, an atheist. Spinoza

was born of Jewish parents who had escaped the Inquisition in Portugal

by coming to Amsterdam where Baruch (Latin: Benedictus) was

born. Spinoza was a very unorthodox thinker--and his ideas

eventually got him expelled from the Jewish community (1656).

Because he saw God as present in everything – as the source and essence

of all substance – he was viewed variously as a pantheist, a

materialist, an atheist.

He was a moral relativist, who did not believe in some set of

transcending religious or civil laws that we ought to conform ourselves

to, but who instead believed in following out our own natural personal

imperatives – ones that no one else had a right to pass judgment on.

This was not a philosophy designed to make the religiously conservative

community around him very happy. But it certainly spoke to those

souls who were tiring rapidly of the mean spiritedness of the

religiously orthodox – a growing number of youthful minds who hoped to

rise to truths which were vastly higher than the traditional variety

that had brought Europeans to war against each other mercilessly.

The Mechanization/Materialization of the Soul

Naural Religion or Deism. Despite

the rapid secularization of Western culture, most philosophers were not

willing to give up on the all-important idea of God – not yet. It

was too soon to make an abrupt departure from the traditional

world-view in which a providential God was all-important to the Western

sense of order, predictability, security, hope.

Indeed, Newton thought of himself as being religiously quite

devout. His theory of the universe – so he thought – was intended

as a powerful tribute to the Grand Architect who designed such a

wonderfully complex yet beautiful creation.

However, the observation was unavoidable that, having created such a

masterful work, the Grand Architect was really no longer necessary to

the functioning of creation. Indeed, the view was inescapable

that, from the time of creation eons ago, creation had been completely

self-running according to God's own laws of nature. It did not

need further "intervention" from God. Truly, since that time, God

had been entirely redundant to the workings of the universe.

Reforming Christianity along more Secular lines. In fact, from this standpoint one would have to say that there was no

need to hear further from God – for God to be involved in the course of

the world's affairs. Accordingly, there was also no need to pray

to him – even to acknowledge him really – though few were yet willing

to jump to this next step in their line of logic.

Thus the feeling was growing among the "enlightened" philosophers that

those that continued to insist on the life of piety were self-deluded –

and possibly dangerous. Still fresh were the memories of the

great slaughter undertaken in the name of Protestant and Catholic piety.

So the Enlightenment was not a matter of just leaving religion alone –

and going on without it. This matter of religion too had to be

addressed.

Now the intention of the Enlightenment philosophers was not to destroy

Christianity, but to take its "best" features, particularly the high

moral-ethical character of Jesus, and focus in on that instead.

The rest, the miracle stories and the divine "revelations," all that

could be/should be carefully removed from Christianity.

Thus the West saw the publication of a mass of works at the end of the 1600s in the order of John Ray's The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of Creation (1691); Locke's The Reasonableness of Christianity (1695); and John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious (1696).

But by the 1720s and 1730s, the Deist voice was now become one of

intense criticism of traditional Christianity. Take for instance

the work of Matthew Tindal, Christianity as Old as the Creation

(1730) – which became something of the official Deist "Bible" in his

time. Here Tindal laid out the argument that all that was

valuable in Christianity was that which universal reason alone would

hold true. All else (i.e., revelation) was superstition – the most evil

form of subjugation of the human mind.

Or consider the work of Thomas Woolston, an English Deist. In his Discourse on the Miracles of Our Savior, he debunked the miracle stories of Jesus and the resurrection accounts in Scripture – on the basis of rationalist arguments.

These were not just voices "outside" the church. In fact they

were essentially voices "inside" the church, clamoring for its

"enlightenment." Even the English Archbishop Tillotson joined in

the chorus of those calling for a "natural religion," a Christianity

brought up-to-date with enlightenment thinking.

6Tragically,

there would be more than just this Ashley-Locke disappointment arising

from the effort to find the right utopian formula in the face of life’s

ever-developing challenges. In fact, failure rather than success

– and often very brutal failure at that – would be the normal outcome

of such ventures ... over and over again. But there would always

be the strong temptation to try again anyway – especially on the part

of those who made such armchair social design their main work in life,

social philosophers, social critics, journalists, progressive

politicians, government technocrats, etc. Despite the miserable

historical record of failure of such social ventures, that record would

be completely disregarded, so certain were such intellectuals that

their newest formula would finally be the one that would bring grand

social success (also making them therefore the social geniuses of their

day).

John Tillotson - Archbishop of Canterbury (1691-1694)

He portrayed Jesus as not a savior of unworthy sinners, but instead as an instructor in good (rational) moral living ... the heart of Unitarianism (even Deism)

PROBLEMS ACCOMPANYING THE "MATURING" OF COLONIAL AMERICA |

|

Social stress in Virginia

A major problem was developing in Virginia as the prime real estate

along the shores of the various rivers (James, York, Rappahannock,

Potomac Rivers) of the rich Tidewater region of coastal Virginia was

largely claimed by the earliest of settlers. Within a couple of

generations manor homes overseeing thousands of river front acres began

to be built and the "first families" began to take their place at the

head of Virginia society. A Virginia aristocracy was beginning to

take shape.

At that point, newcomers (after working off their time of

indenture) were forced to head to the mountainous interior to find land

for themselves. Besides the fact that the soil was rocky and the

distance to the ports that would ship their products back to England

great (whereas the wealthy plantations could load their products on

ocean-going ships right at the plantations docks along the river), the

"poor whites" of the interior were always faced with the problem of

very bloody Indian attacks. The lives of these later Virginians

were very hard ... their earnings marginal at best.

Bacon's Rebellion (1676)

In 1676 the frustration felt by those later arrivals exploded in a

major uprising by Virginia's Western frontier farmers and also by some

of the English indentured workers in the East ... led by a young

aristocrat Nathaniel Bacon (and thus termed "Bacon's Rebellion").

A number of grievances motivated this rebellion. Their world

stood in such stark contrast to the privileges of Governor Berkeley and

the handful of wealthy Virginians with which he surrounded himself. The

rebels were particularly furious about what they felt was the

indifference to their problems characteristic of the Jamestown

government ... and especially the lack of protection against the

Indians by that government.

Bacon's Rebellion was put down by Governor Berkeley only with much

difficulty – and only after the rebels, worked up to intense anger,

succeeded in marching on the Virginia capital Jamestown and burning it

to the ground. Then in the midst of events Bacon became sick and

died. Leaderless, the rebellion quickly collapsed.

The growth of slavery

The net result of the revolt was a deepening of the social gap between

the Virginia aristocracy and the Virginia frontiersman. But also

the aristocrats were so unnerved by the anger of the rebels at this

point that the Virginia wealthy lost interest in white indenture – and

moved to use fully slave African labor in its stead.

Slavery as an institution had been recognized as a permissible

institution only in 1654. But as slavery extended its place in

the Virginia economy, the laws regulating and controlling slavery

advanced in accompaniment. By 1705 the Virginia Slave codes

defined the institution fairly much as it would be practiced in

Virginia for the next 160 years.

Human "Enlightenment" and witchcraft in New England

Meanwhile a serious problem would gradually develop in New England

because of the very success of the colonies there. The strong

dedication arising from royal persecution that had so greatly focused

the early work of the New England colonists would soon fade away.

As it became clear that the King was far away, preoccupied with major

problems of his own brewing back in England (problems which the New

Englanders carefully stayed out of), the sense of religious-social

urgency which had originally inspired the heroic activity of the New

England colonies gradually got lost. The generations which

followed became complacent about the life that had been passed on to

them by the founding generation. Ritual and routine replaced

spirit and bravery. Human (or "secular') logic – termed at the

times as human "Enlightenment" – seemed to offer better answers to

life's ongoing issues ... much better than merely "waiting on the Lord"

(who to the original settlers had always been the moral and spiritual

guarantor of their success).

And

right along with a rising trust in purely human logic grew the illogic

of a growing acceptance of witchcraft and sorcery as a supplemental

understanding of life's dynamics ... a measure of the distance New

Englanders were beginning to put between themselves and the disciplines

of Biblical spirituality. The political-moral authorities of the

Massachusetts colony attempted to keep some degree of control over this

development.

But in the late 1600s this new mood got away from them.

Unexplained diseases, sudden Indian attacks, and quarrels over

property-rights among the English settlers themselves deeply rattled

the peace.

Finally, in February of 1692 in Salem Village, Massachusetts, an

accusation of witchcraft aimed at one individual quickly led to an

explosive claim of such practices aimed at others (tragically, the fear

of witches was common across all the Western world in the 1600s).

Some 200 individuals were accused of the crime, 30 found guilty in

trial, and ultimately 19 hanged … before the colony’s authorities could

get sentences overturned and things finally brought to a halt (April

1693). The impact of this event would forever bring deep shame to

the Puritans and their legacy … though the event itself actually had

little to do with Puritanism.

What was happening to America's covenant with God ... to make the

American settlement a "Light to the Nations," a "City on a Hill"?

As the 1600s came to a close in America, it looked as if America had

indeed fallen into the ways of Ancient Israel ... wandering from God

when life had finally become so successful that the idea of God and his

sovereignty again got lost in the process. What then would the

future hold for America ... and for the Western or Christian world in

general – which was going through a similar cooling of its Christian

spirit?

|

Bacon's rebels burn Jamestown to the ground - 1676

Bacon's rebels burn Jamestown to the ground - 1676

The 1692 Salem Witch

Trials

by

Thomkins H. Matteson - 1853

Peabody-Essex

Museum

Go on to the next section: Europe during the First Half of the 1700s

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | | | |

France under the "Sun King" Louis XIV

France under the "Sun King" Louis XIV Secular philosophy continues to develop

Secular philosophy continues to develop

Problems accompanying the "maturing"

Problems accompanying the "maturing"