9. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DYNASTIC STATE

EUROPE DURING THE EARLY TO MID-1700s

EUROPE DURING THE EARLY TO MID-1700s

The War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession1701-1714)

France during the early years of Louis

France during the early years of Louis

XV (1715-1743)

The War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession

(1740-1748)

England (now actually "Great Britain")

England (now actually "Great Britain")

during these years

The turning point: The Seven Years' War

The turning point: The Seven Years' War

(actually 1754-1763)

The textual material on page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 380-391.

THE WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION (1701-1714) |

Museo del Prado

Louis XIV was succeeded by his five-year-old great-grandson, Louis XV,1

with France thus being placed under the Regency of his great-uncle

Philippe (Duke of Orléans). Philippe reversed diplomatic course

of Louis XIV by forming a French alliance with Great Britain (England,

Scotland and Ireland were now united as a single kingdom), the

Netherlands and Austria ... aimed primarily at Spain. But Spain

was an easy mark at this point ... and this alliance thus fairly easily

brought peace to Europe. An economic catastrophe was the only

blemish in Philippe's eight-year Regency.2

Louis XIV was succeeded by his five-year-old great-grandson, Louis XV,1

with France thus being placed under the Regency of his great-uncle

Philippe (Duke of Orléans). Philippe reversed diplomatic course

of Louis XIV by forming a French alliance with Great Britain (England,

Scotland and Ireland were now united as a single kingdom), the

Netherlands and Austria ... aimed primarily at Spain. But Spain

was an easy mark at this point ... and this alliance thus fairly easily

brought peace to Europe. An economic catastrophe was the only

blemish in Philippe's eight-year Regency.2

When Louis finally reached his majority (1723) and Philippe died a few

months later Louis turned to his old tutor, the Catholic Priest Fleury,

who in 1726 became both Catholic Cardinal and Louis's first

minister. Fleury restored the royal finances that had been

exhausted by Louis XIV and guided France diplomatically in such a way

that the kingdom was largely at peace during his 17-year premiership,

which ended only upon the aged Fleury's death in 1743. At this

point Louis took full personal control of the running of his kingdom.s

1Louis XIV had ruled so long (72 years) that he outlived a whole line of successors.

2The catastrophe

resulted from a speculative investment bubble that developed as the

French followed the lead of the Scottish economist John Law, who urged

the greatly expanded use of paper money over gold to stimulate the

economy. This in turn led to wild investment in the Mississippi

Company developing land in American Louisiana. As all speculative

bubbles ultimately do, it burst in 1720, ruining financially all sorts

of investors.

When

the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI3 died in 1740, Europe got

drawn into a dispute over who should inherit the throne. When his

daughter, Maria Theresa, took the throne, fighting broke out. The

ruling families of Britain, France, Spain, the Dutch Republic, Bavaria,

Prussia, Denmark, Saxony-Poland, Russia, all got involved in one side

or another. The rising German power Prussia – under Frederick II (the

Great) – made the first move by invading Silesia (thereby doubling

Prussia's size). At this point the race was on to see what other

parts of the Habsburg holdings one or another European king could

swallow before the Habsburgs could get their act together during this

time of contested succession.

Indeed French King Louis XV jumped at the chance to move against

Austria and take portions of Bohemia; Maria Theresa's Austrian and

Hungarian troops countered with an advance against French ally

Charles of Bavaria, who was claiming the position of Holy Roman

Emperor; the Saxons joined the action as ally of the French and the

Prussians: the King of Naples, Charles (soon to be also Spanish King as

Charles III) attacked Milan in the North of Italy, drawing an Austrian

counter-move, etc., etc. Then English King George II's British

army got into the act in order to "balance" the odds, gathering a

coalition of smaller German states to support Maria Theresa, thus

pitting the English again against the French. Russia tried to get

into the action ... but troubles at home weakened the Russian

participation. Then Louis XV tried to distract the English by

supporting the exiled rebel, "Bonny" Prince Charles Stuart, who had

never given up his right as a Stuart to inherit the Scottish – and also

English – throne. So the chaos thus spread to Scotland.

With the English thus distracted, the French, and their Spanish allies,

attempted an invasion of England by sea ... which ultimately went badly

for the French and Spanish. Failing there, the French then invaded and

occupied the Austrian Netherlands (or Belgium – being held since 1714

by the Austrians rather than the Spanish) ... with the Dutch further

north being forced to respond.

Meanwhile there was also much military action overseas in North America

and India. The French and their Indian allies conducted

many raids against English settlements, which led the colonists of

Massachusetts to organize a strong countering move against the

strategic French fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.

They captured the fort (1745) ... and continued to hold it against a

French effort to retake it. But at the end of the war in 1748

English King George II returned it to the French in exchange for the

Indian port of Madras ... much to the great annoyance of the American

colonists who had sacrificed greatly for their victory.

But after

all, European wars were not understood to be fought on behalf of any

subject people like the colonial Americans ... but instead for the

personal gain of the ruling families of Europe. Nationalism,

focused on the interests of the common people, was not yet (except

among the Dutch and the colonial Americans) a driving force in European

politics. But it soon will be.

India was also brought in as a key piece in the European dynastic

competition. The French made the first move (1746) by seizing the

port city of Madras, a lightly defended commercial outpost of the

British East India Company. When the regional prince or Nawab, an

Indian ally of England, attempted to retake Madras, his army was

crushed by the French. The British then countered by attacking

the commercial settlement of the French Compagnie des Indes at

Pondicherry. But it was well fortified and the British soon

abandoned the effort. However at the end of the conflict the

British had Madras returned to them in exchange for the return of

Louisbourg to the French.

In the end, all that this long War of the Austrian Succession produced

was the entrance of Prussia into the ranks of Europe's major powers

(Prussia got to keep Silesia), the confirmation of Maria Theresa as

Austrian Archduchess and Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, France's

withdrawal from the Netherlands, France's promise to end support of the

Scottish rebellion, and the restoration of French and English overseas

territories lost during the war. To the embarrassment of the

major players themselves (except Frederick of Prussia – who emerged a

hero among his people) little else was achieved by all this military

effort ... except the depleting of the treasury of a number of royal

families of Europe ... and the disgruntlement of the civilian

populations burdened with the responsibility of replenishing the empty

royal treasuries. This would become a source of major trouble in

the years ahead.

3At

this point the lands held by the Habsburg Emperor included Austria,

Hungary, Bohemia (the land of the modern-day Czechs), Croatia, Parma

(Italy) and smaller scattered holdings in East-Central Europe.

She ruled the Austrian Empire from 1740 to 1780

Kunsthistorisches Museum - Vienna

National Portrait Gallery - London

George I with his family

The Upper Hall of the Old Royal Naval College

George I with his family - detail

The Upper Hall of the Old Royal Naval College

He directed the Scottish Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-1746 ... which failed as a result of a huge Jacobite defeat at the Battle of Culloden (April 1746)

National Portrait Gallery - London

Actually Prussia started out as two distinct principalities,

Brandenburg-Prussia, united in the person of the leading member of the

Hohenzollern family (of the Franconian branch). In 1701, the Duke

Frederick of Prussia took for himself the title of "Frederick I, King

in Prussia." His son, Frederick William, who took Frederick's

place at his death in 1713, turned out to be an ambitious reformer of

Prussian life, disciplining the Prussian bureaucracy, strengthening

considerably the Prussian military, conducting successful diplomacy in

order to keep Prussia out of any expensive wars, and leaving a surplus

in the state treasury at his death in 1740.

Frederick I

For the next 46 years (1740-1786), Prussia was under the rule of the

extremely capable Frederick II, a patron of the arts and philosophy ...

but most importantly the military. He built up a standing army

(including a very mobile cavalry) of 80,000 well trained men, able to

move quickly and decisively in action in accordance with Frederick's

own exceptionally skillful tactical and strategic direction. Thus

the War of the Austrian Succession confirmed Prussia as not only a new

"great power," but the only one to gain any real or lasting benefits

from the war.

by Johann Georg Ziesenis (1763)

Ivan had left an infirm son, Feodor, to rule after him, who in turn in

1598 had died childless, ending the Rurikid dynasty that had ruled

Moscow since the 800s. During Feodor's reign his brother-in-law and

chief minister, Boris Gudunov, had actually governed Russia ... and at

Feodor's death the Zemsky Sobor (national counsel) voted him as Tsar.

Gudunov worked hard to open up Russia to Western ways ... but was only

very partially successful. When he died in 1605 he left the Russian

throne to his son, Feodor II ... who was immediately murdered by

another claimant to the throne, throwing Russia into the "Time of

Trouble."

One individual after another rose and fell as Tsar ... and Russia

collapsed socially into devastating disorder. The 1601-1603 famine,

accompanied by the plague and the roaming of the countryside by

cutthroat brigands, killed approximately one-third of the Russian

population. Also the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth took advantage of

this time of chaos to dominate Russia.

Finally in 1613 the Zemsky Sobor turned to the 16 year old Mikhail

Romanov (whose grandfather had been a key counselor to Ivan IV),

pleading with him to become Tsar ... and bring the chaos to an end.

Actually, it was Michael's father, Feodor Romanov, who did the

governing of Russia during the first 20 years of Michael's reign.

Feodor had been a powerful military boyar (nobleman) who had been

forced by a jealous Godunov to take up monastic life ... and who now

years later had become the head of the Russian Orthodox Church as

Patriarch Filaret! Having the leader of the Orthodox Church as

co-ruler with the secular Tsar was actually quite in keeping with

Byzantine tradition!

During this period (1613-1633) of father-son governance, Russian

political power began to be drawn more closely into the hands of the

Tsar ... and economic control over the Russian populace tightened

considerably, the aristocracy finally brought under taxation ... and

the peasants locked to the land they were born to so that they could

not escape to the steppes (where they had been able to avoid taxation).

In 1645 when Michael died, his place as Tsar was taken by his son

Alexis (or Alexei) I. His 31 years of rule were marked by a

continuing and hugely financially draining war with Poland (1654-1667)

and Sweden (1656-1658); a horrible split (or Raskol) in the Russian

Orthodox Church between the "Old Believers" and the ritual reformers

following the heavy-handed lead of Patriarch Nikon; and a Cossack

rebellion (drawing the poor in revolt against the oppressive tax system

of Russia) in Southern Russia during the period 1667-1671 which had to

be put down brutally by the Tsar's streltsy.

When in 1676 Alexis died, his oldest surviving son

Feodor III took over at age 15. He was of a liberal nature ...

but also sickly and weak. He was a reformer ... but mostly

interested in matters of church rather than state reform. In any

case he ruled only 6 years before he died.

Alexis

I - 1645-1676

The

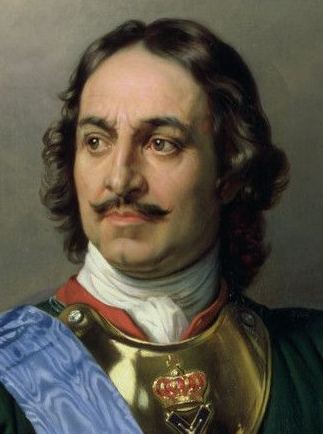

Boyar Duma (council of noblemen) turned to Feodor's half-brother Peter

to take the throne. But he was opposed by followers of another of

Alexis's sons, Ivan V – whose candidacy was pursued by Ivan's older

sister Sophia. She and her streltsy supporters murdered some of

Peter's family and friends and then forced the Duma to accept a dual

Tsardom of her brother Ivan and her step-brother Peter. Tough as

she was, over the next seven years she herself effectively

governed. Finally (1689) Peter faced down Sophia ... and had her

sent off to a convent, thus ending her political interference.

Ivan V continued formally to rule with Peter. But Ivan was

another sickly Romanov... and probably even mentally so. In any

case Peter now moved to take charge of Russia personally.4

The

Boyar Duma (council of noblemen) turned to Feodor's half-brother Peter

to take the throne. But he was opposed by followers of another of

Alexis's sons, Ivan V – whose candidacy was pursued by Ivan's older

sister Sophia. She and her streltsy supporters murdered some of

Peter's family and friends and then forced the Duma to accept a dual

Tsardom of her brother Ivan and her step-brother Peter. Tough as

she was, over the next seven years she herself effectively

governed. Finally (1689) Peter faced down Sophia ... and had her

sent off to a convent, thus ending her political interference.

Ivan V continued formally to rule with Peter. But Ivan was

another sickly Romanov... and probably even mentally so. In any

case Peter now moved to take charge of Russia personally.4

Peter had a tremendous impact on Russia in two important ways.

First of all was his modernization of the Russian military and the

creation of a Russian navy. To better inform himself of modern

Western naval matters – and to try to create an alliance for system

Russia that he could use against the Turks – Peter traveled (1697-1698)

to Western Europe to study Western ways and to meet with various

political leaders. He even worked "incognito" (how exactly could

a 6'8" Russian work "incognito'?!!!) for four months at a Dutch

shipyard studying modern shipbuilding. And though he did not

achieve his grand alliance, he picked up all sorts of key points about

diplomacy. He was an outstanding learner.

With

his navy he seized the Turkish Ottoman territory of Azov (adjoining the

Black Sea) in 1696 and built his first naval base there (1698).

He then turned his attention north to the Baltic Sea. With an alliance

of Denmark-Norway, Saxony, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, he

faced Sweden, dominators of the Baltic Sea. His first effort at

fighting Sweden (1700) proved to be largely a failure and he backed off

... but used the time while Sweden continued to fight his allies to

reorganize the Russian military. He also began to build his new

capital facing out on the Baltic Sea – St. Petersburg!

Having finally defeated Poland, Sweden now turned its attention to

Russia (1708) ... launching an invasion which now went poorly for

Sweden. The next year the two armies met further south in

Ukraine, which ended disastrously for the Swedes. Unfortunately

for Peter, pumped with his sense of military success, he decided to go

it alone against the Ottoman Turks (1710-1711). The results were

disastrous for Peter ... and he had to return the territory he had

earlier seized along the Black Sea (including valuable Azov). But

he was soon ready to resume action in the North and challenged the

Swedes on sea and on land, taking Livonia (Estonia and Latvia) and

Karelia (southern Finland), the vital territory he would need

protecting his new capital at St. Petersburg.

But besides the impact he made on Russian military organization and

strategy, he also had a huge impact on Russian culture ... having

studied culture as closely in his trips to Western Europe as he had

studied the art of Dutch shipbuilding. He was particularly

interested in West European architecture, and modeled his new capital

city after the cities of Western Europe. He even placed a heavy

tax on the wearing of the traditional beard and robe, in order to push

his noblemen to look more "modern." He did what he could as a

follower of the Western "Enlightenment" to curb the powers of the

clergy ... leaving the position of Patriarch unfilled after 1700,

replacing the Patriarchy with a Holy Synod. He personally also

saw to the naming of bishops. And he restricted entry into

monasteries until a man reached at least 50. Thus the traditional

power of the Byzantine Church in Russia was weakened deeply.

When Peter died in 1725 his position was taken up by his wife Catherine

... though she reigned only two years before she died in 1727.

She was followed by their son, Peter II whose also short rule ended in

early 1730.

His place was taken by his cousin Anna, who proved to be as

autocratic as any of the most autocratic of her predecessors. In

her ten years of rule (1730-1740) she had over 20,000 Russians arrested

and subjected to her program of cruel punishment for a variety of

political crimes. She favored Germans over Russians as counselors

– much to the irritation of her Russian subjects. And she drained

the state treasury fighting the Turks in a (successful) effort to

regain Azov. Yet despite the expense, this action demonstrated to

the world (and the Turks) that the Russians were now a serious power in

Eastern Europe.

4Ivan would die in 1696, making Peter sole ruler at that point.

Ivan

V - 1682-1696

1682-1689

by Jean-Marc Nattier (c. 1717)

Hermitage Museum

Elizabeth (1741-1762)

Once

again the dynasties of Europe fell into bitter conflict, a conflict

that raged not only across Europe, but also North America, Central

America, West Africa, India and the Philippines. It involved a

number of regional rivalries, between France and Great Britain, Prussia

and Sweden, and also Prussia and Austria ... though the greatest action

was between France and Great Britain. Alliances were formed,

quite different from the ones of the War of the Austrian Succession ...

now involving former enemies as allies. France now allied with its

traditional enemy Austria, joined by Spain, Sweden and Saxony.

England allied with Prussia and a number of smaller German states

(including naturally Hanover) ... and eventually Portugal. Russia

also got involved, at first as an ally of Austria ... then switching

sides in 1762 to becomes a Prussian ally.

The war started as a dispute over the control of Canada, with France

(and its Indian allies) fighting the British and the English-American

colonists (and their Indian allies).5 The Indians resented the

rapid expansion of the English colonists into the North American

interior and conducted bloody raids on the settlers in an attempt to

block this expansion. The French, with interests around the

perimeter of these English colonies (Canada to the north, the

Mississippi River Valley to the West and the Gulf of Mexico and Florida

coast to the South) were just as interested as the Indians in seeing

this English expansion in America halted ... even reversed. It

was the rush of the English and French to place their own forts in the

upper reaches of the Ohio River valley (beginning in Western

Pennsylvania and flowing west until it joined the Mississippi River)

that started the conflict in 1754. The action did not go well for

the English (including a young George Washington) and the next year the

English swung the action north to New France (Canada) ... though here

too the French largely held their own over the next couple of

years.6 The British immediately reacted by beginning the expulsion

(1755-1763) of some 11,000 of the French Catholic population (the

Acadians or "Cajuns") living in British Nova Scotia ... because

of their (rightly) suspected disloyalty to the British crown.

Then when the conflict spread to Europe itself, the French pulled

troops out of Canada ... and the military situation reversed itself in

America. In 1758 the English captured a number of key French

forts ... and the strategic town of Quebec. And in 1760 the

British were able to surround and capture Montreal, sealing the fate of

Canada, which was now fully in British hands.

In the Caribbean the British navy fought the French navy for the key

sugar producing islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique (considered even

more valuable to the British than the English colonies in North

America!). Then when Spain got involved, the English quickly took

Cuba.

War

in Europe itself finally broke out in 1757 when France and their allies

attacked Prussia (allied only with England and George II's German

lands). That did not go well for the French, so they attempted

instead to take the war to England. But the expanded French navy

proved no match for the British navy (the Battle of Quiberon Bay –

1759) and the French invasion of England had to be called off.

When "neutral" Spain7

finally got militarily involved in order to help the French by invading

Portugal, Spain – like France – found itself in major trouble.

Much like the alliances with the Indians in America, the French and

English had established conflicting alliance systems with the Asian

Indian princes, who had their own local conflicts to deal with.

But here too things did not go well for the French, who one by one lost

their Indian forts and trading centers to the British. Then with

the French rather completely knocked out in India, Britain turned its

attention to the Spanish Philippines, taking the capital Manila ...

humiliating the Spanish as well as the French. In 1763 an

exhausted France and Spain finally called for peace.

The war had been costly to everyone involved, but particularly to the

Spanish, who now fell even lower in political status, and the French

whose royal treasury was on the verge of bankruptcy and whose King

Louis XV had also lost major political status even among his own

people. On the face of it England had come out a big

winner. But the cost involved in victory would prove to be very

problematic ... especially in America where the colonists saw little

advantage for themselves in comparison to the burdens they themselves

had assumed in helping achieve this English victory.

5Thus the conflict and ensuing war was known in the English colonies as the "French and Indian War' (1754-1763).

6The only British success that year (1755) was their recapture of Louisbourg.

7Spain was not so

neutral when it bankrolled the French royal treasury just as its

borrowing power had become exhausted by the war. The immense

French royal debt at that point appeared to have expanded well beyond

the control of the French themselves.

French ships burned (left)

and captured (right) by the English in Louisbourg harbor - July 26, 1758

Royal Ontario Museum,

Toronto

Yale Center for British Art

New York Public

Library