5. INTO THE "DARK AGES"

THE COLLAPSE OF ROME IN THE WEST

CONTENTS

The weakening and collapse of the The weakening and collapse of the

Roman imperial order

The Germanic flood begins The Germanic flood begins

The textual material on the page below is drawn largely from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 158-165.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

364 Valentinian is chosen by his troops

as emperor

375 The beginning of the Germanic threat

... with an angry Valentinian dying

378 His brother Valens is killed in a battle

with Visigoths at Adrianople

379 Theodosius rules (379-395) ...

at which point Rome becomes oficially Trinitarian

390 Ambrose of Milan faces down

Theodosius over the latter's brutality

395 Honorius and Arcadius follow father

Theodosius to office

Honorius is seated at well-protected

Ravenna

11-year old Honorius depends on

Stilicho to govern for him

Stilicho and Visigoth Alaric are in

constant contention

408 Jealous Honorius and others foolishly execute Stilicho

410 This opens the way for Alaric to

crush Rome (408, 409, 410)

But Alaric dies at sea

Augustine begins writing his The

City of God (ca. 410)

423 Honorius dies … with only

weak emperors to follow him

433 Aetius is the last great Roman

leader in the West (433-454)

Aetius holds off the various

Germanic tribes in numerous battles

452 But Atilla and his Huns finally slip past

Aetius and his worn-out army (452)

Pope Leo persuades Atilla to return north; Atilla soon dies

454 But a very paranoid Valentinian III kills

Aetius

455

But Valentian is then killed by

jealous Maximus (455)

But at this point, for all practical purposes, the

Empire is dead in the West

THE WEAKENING AND COLLAPSE OF THE ROMAN IMPERIAL ORDER |

|

The Valentinian dynasty (364-392)

Valentinian and Valens (364-378).

With Julian the "Apostate" dying childless, the military took the

initiative once again to choose their emperor, a Pannonian officer

named Valentinian. But they also demanded a co-regent so as to

assure a more secure political succession. Consequently,

Valentinian was elected to be western Augustus – and named his younger

brother Valens as Eastern Augustus.

But these would be very troubled times for Rome. By

the early 370s, the Germanic tribes were starting to act very nervous

along the Roman borders. A group of fierce central Asian nomads –

called "Huns"1 by the

Romans – had pushed westward into Germanic lands, driving the Germanic

tribes up against Rome's Rhineland border … which the tribes then

attempted to cross. So angry was Valentinian during a meeting

with a delegation of Germanic tribesmen that he suffered a stroke and

died (375).

Meanwhile in the East, Valens finally agreed to allow Germanic tribes

to settle in Roman lands along the Danube as foederati – groups who by

treaty or foedus agreed to serve as soldiers in exchange for land

rights within the Roman Empire. But these soldiers and their

families were actually treated rather contemptuously … forced to pay

high taxes and unable to afford the food they needed.

The Battle of Adrianople (378)

Thus

in 378, the Visigothic tribesmen under their leader Fritigern rose up

in revolt. Then when Valens went out to put down their revolt, he

and most of his troops were killed in the battle … and the rest

completely routed.

And this defeat would result in the loss of Rome of most of its

capable officers and veteran soldiers – and would now find it

impossible to rebuild the ranks with Romans. The Romans would

instead have to resort to the use of Germanic mercenaries to man their

legions – a difficult (and expensive) situation considering the fact

that Germanic tribes were also their natural enemies. This would

mark an important turning point in the relations between the Roman

Empire and their Germanic neighbors.

Theodosius (379-395)

Theodosius

I

from the Missorium of

Theodosius

With

Valentinian's death in 375, the Western emperorship had gone to his

cousin Gratian. And upon Valens' death in 378, Gratian then chose

Theodosius (of a Roman family of former military leaders) as Augustus

for the East. For a while this arrangement worked fairly

well. But soon Gratian began to lose effectiveness as a Western

Augustus. His friendship with the tribesmen and his allowing

Bishop Ambrose of Milan and the Frankish (another Germanic tribal

group) general Merobaudes to actually run the Empire in the West all

acted to alienate his troops. Gratian was finally challenged by

his own troops and defeated and killed in battle.

Theodosius now co-ruled the Empire, first with one then another

individual, until 392 when his young co-ruler Valentinian II was found

hanged in his home (possibly a suicide; more probably as a result of a

fight with Arbogast, the Germanic Frankish leader who was at this point

the effective military governor in the West). Theodosius was now

the sole ruler of all the Empire, both East and West … but only for

three more years.

Rome is now officially "Trinitarian."

One of the critical developments under Theodosius's rule was the

establishment of Trinitarian Christianity as the official religion of

Rome. Up to this point, Christianity had been strongly favored

but not yet Rome's official religion. But now, under Theodosius's

orders, Trinitarian or Catholic/Orthodox Christianity became the sole

religion supported by the state. All pagan worship was to be shut

down, the Temples closed, pagan holidays ended2 … and the Vestal Virgins – the most ancient and most revered of the pagan religious icons – disbanded.

However … Theodosius's relationship with Ambrose, bishop of Milan, is

indicative of the new dynamics emerging within Christendom at that

time. In 390 Ambrose excommunicated (cut off from the privilege

of receiving the Christian sacraments) Theodosius for his massacre of

7,000 inhabitants of Thessalonica after his military governor stationed

there had been assassinated. As directed by Ambrose, Theodosius

underwent several months of public penance for this deed.

Theodosius was of course no wimp. But neither was Ambrose.

The church was in fact coming to be led increasingly by such figures of

power and authority.

Meanwhile in the East, the Germanic tribesmen continued to give Theodosius considerable trouble.

Religious troubles brewed, as there was an attempt by Eugenius, a

military usurper who seized control in the West and then – though a

Christian himself – sought to build popular support for himself there

by restoring some of Rome's pagan practices. Theodosius and

Eugenius met in battle at the Frigid River in 394, and with the help of

a "divine wind" (which turned a near defeat of Theodosius into a grand

victory) Eugenius was defeated and executed. Thus again, the

entire Empire found itself under the sole rule of Theodosius … at least

briefly. Early the next year Theodosius died of natural causes.

Honorius (nominal Western Emperor 395-423)

and Arcadius (Eastern Emperor 395-408)

The Empire now passed to his two sons, Honorius ruling in the West

(with his capital at Milan, and then later Ravenna)3 and Arcadius ruling

in the East (from Constantinople). The Roman Empire was again

divided ... never to be united again. Actually from this point on

the Western Empire fell increasingly under the control of the Bishops

of Rome and various semi Roman / semi German or even fully German

military strongmen or "patricians" (such as Arbogast – and subsequently

Stilicho). The Western emperors would rule in name only.

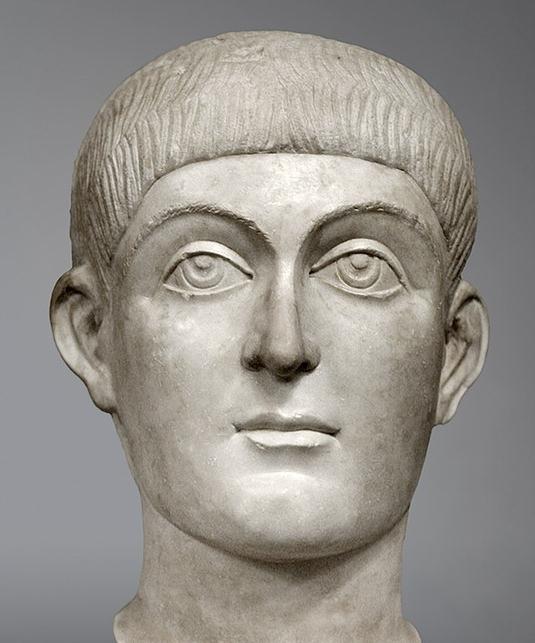

Honorius (W. Emperor 395-423)

and Arcadius (E. Emperor 395-408)

Honorius - Western Emperor Honorius - Western Emperor

(395-423)

Arcadius

- Eastern Emperor

(395-408)

Silver siliqua coin glorifying

Honorius

Stilicho the "Patrician" versus Alaric the Visigoth

As

the 11-year-old Honorius became officially emperor of the Western

Empire, Flavius Stilicho became de facto governor of the West.

Stilicho was born a Roman mother, but a Germanic Vandal father.

In his upbringing he was treated entirely as "Roman." He rose

quickly within Theodosius's army and ultimately was given the task by

the emperor of defending the Empire against the Visigoths. In the

battle between Theodosius and Eugenius in 394, Stilicho was one of the

generals who – along with a major storm (the "divine wind") – helped

turn the battle in favor of Theodosius. Theodosius was so

impressed by Stilicho's performance that he appointed him guardian of

his son Honorius just prior to his death in 395

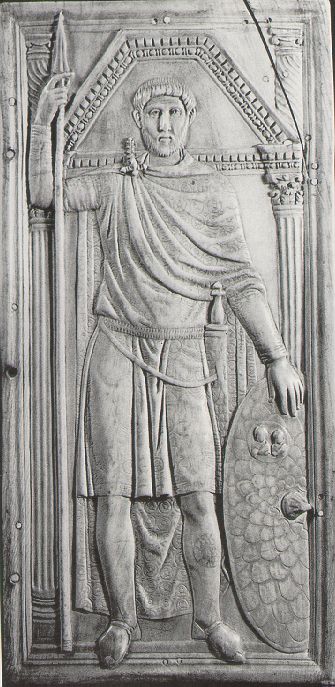

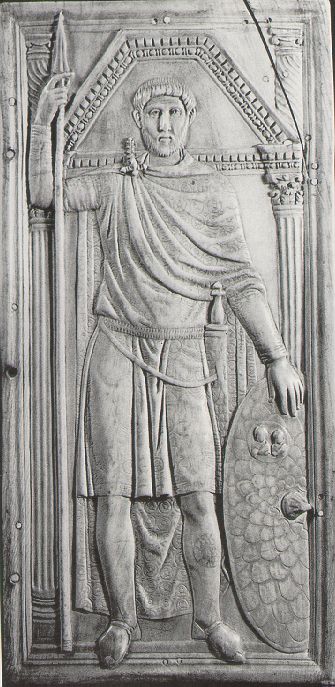

German-Roman general Stilicho

Copy of an ivory carving.

The original diptych, carved circa 395, is in Monza (Italy)

Römisch-Germanisches

Zentralmuseum,

Mainz, Germany

Holding off Alaric and his Visigoths

As Honorius became officially emperor of the Western Empire, Stilicho

became de facto governor of the West. His main task would be to

stop the rise of his former colleague, the Visigothic foederati

commander Alaric, who had replaced Fritigern as leader of the

Goths. With Alaric threatening the Eastern Empire in Thrace in

395, and the Eastern Roman army fully occupied further east in battle

against the Huns, this left Stilicho the full responsibility of

stopping Alaric.

Alaric

Alaric was a Visigoth chieftain principally interested in becoming

recognized within the Roman Empire as a military "protector" over the

imperial household. He was rebuffed in his effort to do this

through a normal rise up the ranks of the military – and thus Alaric

took to conquering. Recognition, not plunder, seemed consistently

to remain his aim in life.

Alaric was born around 370 to a noble Gothic (Western Gothic or

Visigoth) family, who had just fled south to the mouth of the Danube

River at the Black Sea to escape the invasion of Eastern Europe by the

Asian Huns. As a young man Alaric served in the army of the

Gothic foederati – becoming a general in 394 and serving under the

Emperor Theodosius. At this point he began to take note of the

weakness of the Roman hold over northeastern Italy.

When he was later bypassed by Theodosius's sons, Arcadius and Honorius,

in their distribution of imperial offices, Alaric made the decision to

act on his own political behalf. Gathering disgruntled foederati

(for whom tribute payments from Rome had been slacking off) he had

himself proclaimed Gothic king. He then moved his troops on

Constantinople itself. But unable to take this well defended city

(stopped by Stilicho), he turned his troops towards Greece

proper.

The battle between Alaric and Stilicho intensifies

Then he found himself trapped in Greece by Stilicho. But just as

Stilicho was in a position to destroy Alaric and his army, Arcadius

(the eastern emperor) strangely ordered Stilicho back to the

west. This allowed Alaric to pillage the lands of Thrace and

Greece for almost two years (395 396) – though he spared Athens.

In 397 Stilicho again moved against Alaric – crushing his army

(although Alaric himself escaped into the mountains) – but managed to

escape to the north along the eastern Adriatic Sea (Illyricum), where

he was welcomed as a liberator, king of the lands that reach even up to

the middle Danube River.

Then Stilicho was sent that same year to put down rebellion in

Africa. His reputation now was so great that in 400 the Senate

named him "consul."

In the meantime, Alaric conducted a devious diplomacy with the Eastern

and Western branches of the Roman Empire – swearing fealty to one or

another as he felt it opportune to do so. At the same time he

began to equip his troops with the finest of Imperial weapons.

The next year (401) Alaric broke a treaty with Stilicho and arranged an

alliance with Radagaisus, chief of a number of German tribes, with the

intention of raiding and pillaging Italy. He spread terror

through northern Italy – until in 402 he and the German coalition were

met and defeated by Stilicho along the Danube (Radagaisus) and at

Polentia (Alaric) – which Alaric had laid siege to. Again, Alaric

escaped. They met again in 403 and again Alaric was defeated –

but escaped.

1The

precise origins of the Central Asian Huns remain a mystery … though the

Huns certainly came to Europe by way of the steppes of Southern Russia

– possibly fleeing an extensive drought that hit central Asia about

this time.

2The

ones anyway that had not yet turned themselves into Christian holidays

… such as the year's end celebration of Saturnalia – which turned

itself into Christmas!

3Honorius had ultimately moved the Western capital from the besieged

city of Rome … to the well protected town of Ravenna – well-protected

because of the surrounding swamps which made siege by any enemy almost

impossible. Ravenna – not the declining city of Rome – would

serve as the capital of the Western half of the Roman Empire for quite

some time.

THE GERMANIC FLOOD BEGINS |

But at the end of 406 Stilicho was unable to stop a massive raid of

German tribesmen across the frozen Rhine – and the subsequent

widespread pillaging of Gaul. Stilicho's army had become depleted

by its several battles with Alaric and he could offer no serious

resistance to the raiding parties which were running wild across Gaul.

Also, though defeated, Alaric was not considered out of the political

picture. Indeed, in the mounting tensions between the Eastern and

Western Imperial governments, he was called in for support by even

Stilicho ... a development that Stilicho's enemies would soon use to

bring him down.

Also Alaric, who had moved his armies into Greece, seeing mounting

weakness in Rome's (Stilicho's) defensive forces became so bold as to

demand a huge tribute payment as the price of peace. Stilicho

recommended payment ... and the Senators refused to go along with the

idea ... although they had no alternative plan to deal with the

mounting German problem.

Stilicho's fall (408)

Instead Stilicho's political opponents (which now included Honorius),

who had become very jealous of Stilicho's popularity and fearful of his

support among the Roman troops began to spread wild rumors about his

complicity with Alaric – which successfully alienated sections of

Stilicho's army which rose up in revolt against Stilicho.

Stilicho's enemies now felt that they had good ground to have Stilicho

arrested ... and executed (408). Stilicho's son was soon executed

after him.

Confusion now reigned as Roman troops went on a rampage ...with Roman

soldiers turning on the German foederati soldiers and their families in

Roman cities. The slaughter was extensive, and the German

survivors fled the Empire ... added enormously to the ranks of Alaric's

army.

Alaric's first attack on Rome (408)

Now Alaric struck back ... and laid siege to Rome. Finally, with

hundreds of thousands of Romans trapped inside the city ... and slowly

starving, and no signs of help coming from the Eastern Empire – or even

the Western imperial authorities in Ravenna – Alaric was bought

off by the citizens of Rome themselves with an impossibly high ransom,

which stripped the city of most of its wealth ... and certainly its

honor.

But Alaric still pressed for Roman recognition of some kind of official

position within the Empire: rule over the lands between the

Northern Adriatic and the Middle Danube and the command of the Imperial

army. Failing satisfaction in this, he besieged Rome a second

time (409) – and gained the position from the Senate as unofficial

overlord of an imperial usurper, Attalus.

But Attalus proved not to be a compliant vassal – and not greatly

competent. He brought Rome to defeat in Northern Africa where

Rome depended heavily for its grain imports. The Romans began to

complain bitterly about this new regime of Alaric and Attalus.

Alaric consequently dumped Attalus (who nonetheless years later would

reappear as an imperial claimant and thus greatly trouble Roman

politics) and attempted to negotiate a deal with Honorius – but was out

trumped diplomatically with the intervention of a Gothic rival, Sarus.

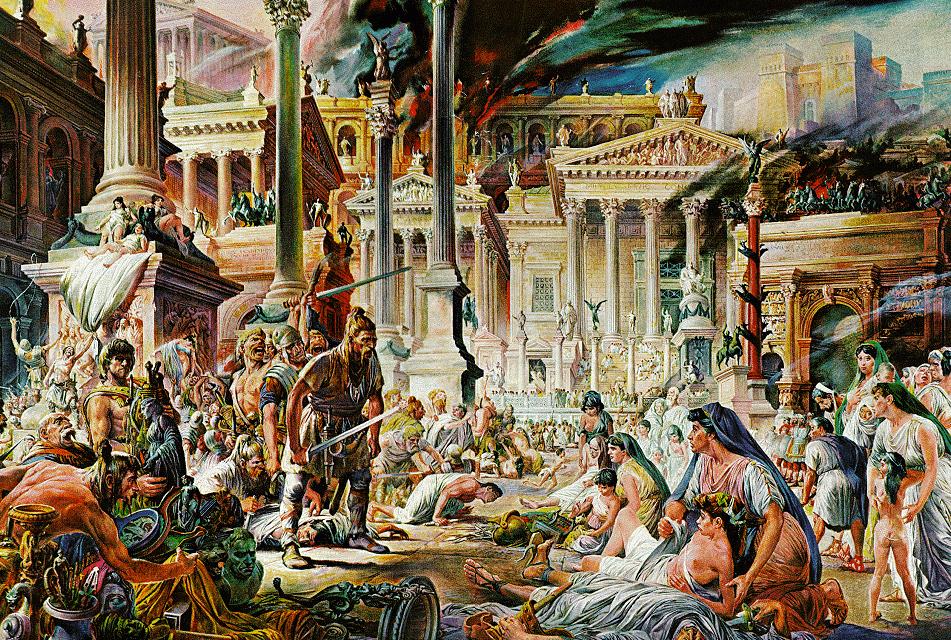

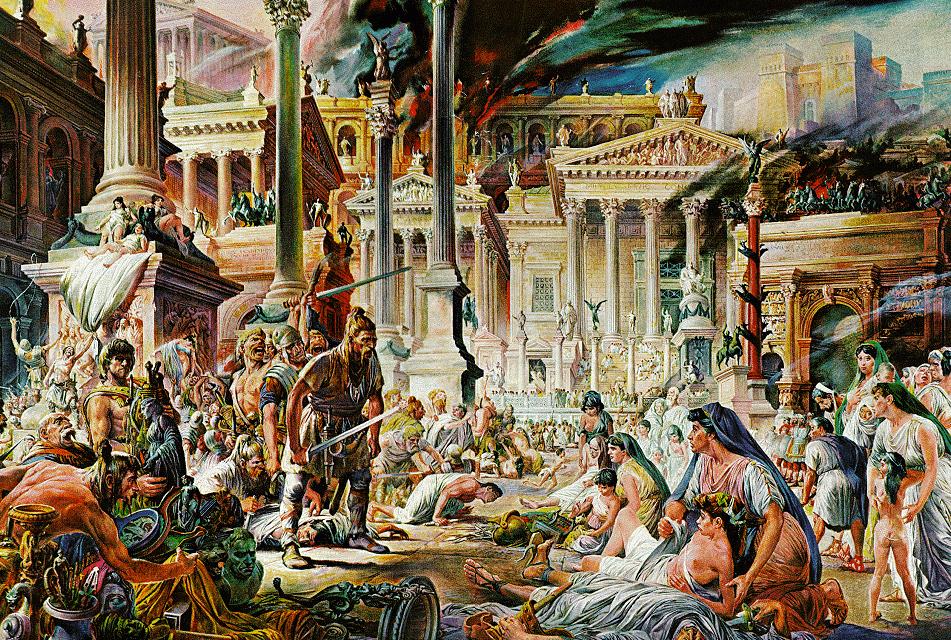

Alaric sacks Rome (410)

But the Roman authorities in Ravenna still could not or would not meet

Alaric's political demands ... which included the removal from power of

Honorius. Failed negotiations and treachery on all sides finally

determined Alaric to once again move on Rome. Alaric's troops

broke through one of the gates ... and for the next three days

plundered Rome ... sending Roman citizens scattering around the rest of

the Empire as refugees, where often an even worse fate (slavery,

prostitution, etc.) awaited many of them.

Having taken what he wanted in wealth from the city of Rome, Alaric

then headed south through the rest of Italy, with the intention of

taking by force the grain lands of North Africa – thus bringing some

contentment to his Roman subjects. But storms destroyed his navy

– and Alaric himself was struck by fever and died in the effort (also

410), bringing to an end the life of this amazing self defined

adventurer.

Overall – despite his ultimate failure at establishing some kind of

Gothic regime of his own, Alaric left an huge mark on his age.

Principally, he had exhausted the Roman resistance in the West, and

opened the way for the various German tribes to invade Gaul and

Spain. It was his marauding of Rome that also caused the

withdrawal of the Roman legions from Britain in 410 (to protect the

Italian homeland from Alaric) – leaving Britain vulnerable to the

invading Picts and Scots to the North and the Saxons to the East.

Passing around the blame

Paganism had by no means been eradicated in Rome with its embrace of

Christianity ... and immediately the two religious groups laid blame

for the city's humiliation at the feet of their opponents, each

claiming that it was the failure of the other's God or gods that had

brought this curse on Rome ... with the stronger argument seeming to

lie with the pagans (though Augustine would offer a very effective

answer of his own with his work, The City of God, written at this time.)

Whatever was the "divine cause," the net effect was a sense of curse

that had fallen on Rome. Its centuries-old image as the power

center of Western Civilization was shattered ... and in its place Rome

now appeared to be a poor, broken city, a mere shadow of its former

greatness.

And such an image of weakness would become simply an invitation for

other rising powers beyond the Empire to see the Roman Empire – at

least in the West – as an easy target. For the German tribes of

north central Europe (Goths, Franks, Alemanni, Burgundians, Angles,

Saxons, Frisians, Thuringians, Vandals, etc.), the rush to move into

the western half of the Roman Empire now began in earnest.

|

Alaric sacking Rome - by Andre Durenceau

The Empire exhausts itself in foolish in-house power struggles The Empire exhausts itself in foolish in-house power struggles

These

were times of tremendous turmoil for the Empire. Various

claimants to imperial power (Constantine III, Sebastianus, another

Maximus, – and, again, Attalus) drained away Roman power as they fought

each – at a time when Rome needed all the resources it could muster

just to control the influx of Germans. Honorius kept himself in

power with the help of some able generals – and a lot of

negotiating. Finally he died in 423, leaving no heir. The

eastern emperor Theodosius III named his six year old cousin Valentinian III as Western emperor.

Flavius Aëtius: the last great Roman leader in the West (433-454)

In

its continuing struggle for survival, the Western Empire was well

served for twenty years by the Roman general Aëtius, born of an

aristocratic Italian mother and a Roman general of German

ancestry. Aëtius began his career as a general commanding Hun

troops and supporting an unsuccessful contender to the imperial

throne. But his arrival before Rome with his Hun army was so

impressive that Valentinian's mother, Galla Placidia, the effective

ruler of Western Rome (or whatever was left of it) agreed to name him

head of the Roman army in Gaul if he sent his Huns back outside Rome's

borders. This he did. In

its continuing struggle for survival, the Western Empire was well

served for twenty years by the Roman general Aëtius, born of an

aristocratic Italian mother and a Roman general of German

ancestry. Aëtius began his career as a general commanding Hun

troops and supporting an unsuccessful contender to the imperial

throne. But his arrival before Rome with his Hun army was so

impressive that Valentinian's mother, Galla Placidia, the effective

ruler of Western Rome (or whatever was left of it) agreed to name him

head of the Roman army in Gaul if he sent his Huns back outside Rome's

borders. This he did.

He then turned his attentions to the Visigoths, forcing them to retreat

to southwestern Gaul, and the Franks, retaking some of the land along

the Rhine which they had seized. One by one he faced other German

tribes – forcing them also into submission.

Meanwhile he had battles of his own within the Roman political circles

– principally against Boniface, his primary military commander.

He eventually defeated Boniface, and was declared supreme military

commander (patrician) in the West. The he turned his attentions

again to the Germans: the Burgundians (whom he decimated), the Suebi,

the Visigoths, the Alans – settling each of them in more or less stable

situations around the Western Empire under some form of treaty

arrangement.

Attila and the Huns

Meanwhile another problem presented itself ... this time in the form of the Huns, and their leader Attila. Meanwhile another problem presented itself ... this time in the form of the Huns, and their leader Attila.

Attila was born near Budapest in Central Europe to the royal family of

Huns. In 433 he became king of the Huns and began the process of

turning his tribesmen into a powerful fighting instrument. With

his new army he brought the German tribes (Ostrogoths) around the Huns

under their sway.

Then in 448 452 Attila, having reorganized the Huns of Central Europe

into a new fighting machine, marched into the very heart of the Roman

Empire. Claiming to defend the honor of Honoria, granddaughter of

the Eastern Emperor Theodosius II, he pressed her cause all the way up

to the gates of Constantinople. He attacked Constantinople in 448

and was bought off with ransom money.

Then he turned westward in 451 with his huge Hunnic Germanic army

against the Emperor of the West, Valentinian III – again claiming to

defend Honoria's honor. He ravaged Gaul (France) and was about to

lay waste to Orleans along the Loire River when a huge coalition of

Romans, Visigoths, Franks and Alemanni led by Aëtius gathered to fend

off Attila at the Battle of Châlons. The devastation was vast on

all sides of the conflict. Theodoric, king of the Visigoths, was

killed. But Attila was also forced to retreat back behind the

Rhine.

But the next year (452) Attila slipped past Aëtius in the Alps and

descended down upon northern Italy – to burn and pillage city after

city. Aëtius, with a greatly depleted army, did what he could to

slow up Attila's advance. Attila stopped at the Po River and

received a Roman delegation (including Pope Leo I) – which convinced

him to return north of the Alps (hunger among his troops and an attack

on his homebase in the north by other Roman legions also contributing

factors). Then before the waiting world could see what he would

do next, he died suddenly at the feast celebrating his marriage to

Ildico.

Valentinian III brings the Roman Empire to its death

in the West (454-455)

Meanwhile Valentinian was growing paranoid about Aëtius's popularity

and power and was easily convinced by ambition conspirators (Maximus

and Heraclius) of the need to assassinate Aëtius, which in 454

Valentinian did by his own sword – thus eliminating the one source of

strength Rome possessed during his emperorship. But then when

Maximus found that Valentinian did not name him as Aëtius's

replacement, he turned against Valentinian and his co-conspirator

Heraclius and had them both murdered … while soldiers who had come to

love Aëtius, though standing close at hand, did nothing to stop the

murders.

Valentinian would be followed by a rapid succession of Roman emperors,

each reigning for only a few years, some only for months or even

days. Finally, only two decades later, the fiction of a Roman

ruling as Western Emperor was brought to an end. The Western

Empire was gone.

|

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

The weakening and collapse of the

The weakening and collapse of the