5. INTO THE "DARK AGES"

BYZANTINE ROME

BYZANTINE ROME

Byzantine (Orthodox) Christianity hangs

Byzantine (Orthodox) Christianity hangson in the East

Mounting problems after Justinian

Mounting problems after Justinian

Byzantine church life - in pictures

Byzantine church life - in pictures

The textual material on the page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 185-193.

BYZANTINE

(ORTHODOX) CHRISTIANITY HANGS ON IN THE EAST |

| By

the mid-400s, the Eastern Roman Empire was distancing itself rapidly

from the Western portion of the Roman Empire (except in the Byzantine

parts of Italy and Sicily). The West's problems seemed far away

from life in the East (the Balkans, Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt).

Eastern Roman culture (actually Greek in character) seemingly continued

as usual. Meanwhile within the Eastern or Byzantine Church

itself, the patriarchs in Constantinople, Antioch and Alexandria vied

with each other for dominating role in this Eastern Christian or

Byzantine world. Struggles with heresy

For reasons that could be clear to only a Greek mind, the church in the early to mid-400s fell into deep dispute over the question of the nature of Christ. Was he of one or two "natures"? Was he in fact one or two "persons"? Nestorius, the patriarch of Constantinople and his followers (strong in Syria and Asia Minor) took a view that Jesus was really two "persons" in the form of the Son of Man and the Son of God. This view was strongly opposed by Cyril, the patriarch of Alexandria, who took the view that Jesus was not only a single person but also of a single nature. The debate grew so heated over this matter that a council was called to gather in Ephesus in 431 to decide the matter. Cyril's supporter arrived first and quickly decided in favor of their own view that Jesus was a single person – and declared "Nestorianism" a heresy. But shortly after Cyril's death another council was called at Ephesus in 449.1 It went further with the position that Jesus was "Monophysite," that is, of a single nature. But the Monophysite position in turn was condemned as a heresy at yet another council held two years later in 451 at Chalcedon, where the "Chalcedonian formula" was adopted (Christ: of two natures [truly God / truly man] coming together in one person). Thus the Byzantine church, in so tightly defining the theological details of the faith, and so rigorously rejecting all groups not able to agree in all details with the catholic or orthodox position, succeeded in alienating both the Nestorians (popular in the East) and Monophysites (popular in Egypt). This would later come to haunt the church when Islam came roaring out of Arabia – and helped by the widespread alienation by the church of many Christian groups in the East, relatively easily drove the domain of Eastern Christendom into humiliating retreat. Eastern Roman or Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II, 408-450

Musée du Louvre, Paris One of Theodosius" achievements was the creation of a Roman law code updated since the time of Constantine. He also created the University of Constantinople. 1The meeting was so violent that Flavian, at that time the patriarch of Constantinople, was attacked and died shortly thereafter of his wounds! 2They were actually reworked by the praetorian prefect Anthemius, who was the power behind the throne in the first years of Theodosius's reign ... for Theodosius was only seven years old when he was proclaimed Byzantine Augustus! Byzantine Emperors Marcian (450-457) and Leo I (457-474)

Musée du Louvre, Paris Leo I was placed on the throne by the supreme commander of the Eastern Army, an Alan named Aspar (as an Arian Christian he himself was forbidden to take the throne). Aspar thought that Leo would be a mere puppet that he could control. But Leo allied with the Isaurians (the Isaurians were a people of long standing residence in southern Asia Minor) and was able to thwart Aspar's plans. Aspar attempted to assassinate Leo in 469 and failed. He and his son were killed in 471. Leo I reversed Marcian's policy of seeming indifference to the West. He in fact organized a very expensive major assault in the West against the Vandals in 468 – which failed miserably, reducing greatly the resources of the Roman Empire in the East. Byzantine Emperor Zeno, 474-491

Originally a semi barbaric Isaurian chieftain named "Tarasicodissa," Zeno married the imperial princess, Ariadne, daughter of Byzantine Emperor Leo I. Through this marriage he eventually became elevated to the position of Eastern Roman Emperor. (The Isaurians were a people of long standing residence in southern Asia Minor). It was he that in 488 convinced the Ostrogothic leader Theodoric not to invade Eastern Roman Empire – but to invade Italy and "liberate" it from its German chieftain Odoacer, who had deposed the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus, and who had taken over as direct ruler of Italy. This effectively spared the Eastern Roman Empire from the German overlordship that was collapsing Roman society and culture in the West. But it looked as if it were confirming the shift of imperial power to the Isaurian tribes – in parallel with the power shift to the barbarians in the West. Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I, 491-518

Anastasius was a Roman civil servant who was elevated to emperorship in 491. Not only was imperial rule returned to Roman hands – unlike the developments in the West where various barbarian tribes had taken over Roman rule completely – but the Isaurians, the primary barbaric challenge to Roman rule in the East, were defeated by Anastasius in 498. Indeed, so complete was the Roman victory over the Isaurians, that the Romans had many of the Isaurians resettled in Thrace as a security measure. However Anastasius was not able to bring religious unity within his Eastern Roman domains. The split between the Orthodox and Monophysite positions on the human/divine nature of Jesus Christ deeply divided Eastern Christian society. Though Anastasius had pledged to support the Orthodox position in his accession to power, he eventually moved into the Monophysite religious camp. Also, the Eastern Empire was constantly threatened from the East by the Zoroastrian Persians – who wanted to regain Armenia and other former Persian areas that had converted to Christianity and had thus come under the Roman imperium. Nonetheless, the governance of Anastasius coincided with a period of economic growth – not only for the imperial government but for Eastern Roman society as a whole. These were relatively peaceful and prosperous times in the East – quite in contrast to the poverty and chaos that had settled over the former Roman West. Byzantine Emperor Justin I (518 to 527)

Justin was an illiterate peasant from Illyria who rose through the ranks of the Roman military because of his considerable ability as a soldier and leader. He was humble enough to recognize his limitations and gathered a circle of very capable advisors around himself. Nonetheless the latter years of his reign were marked with considerable troubles with Ostrogoths to the North and the Persians to the East. |

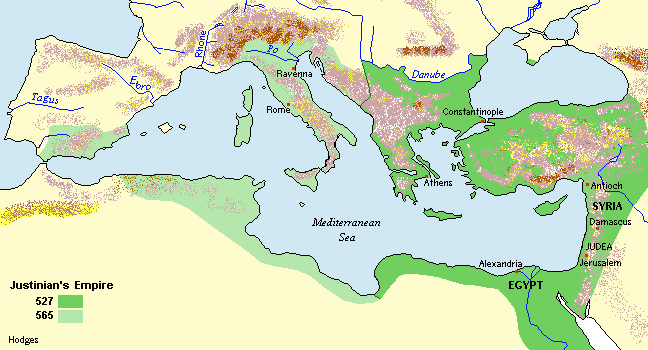

JUSTINIAN

I (527-565) |

| Justinian

was promoted to power by his uncle, the Byzantine emperor,

Justin. After a very brief co-emperorship with his uncle,

Justinian became sole Roman emperor in 527 (at this point there was no

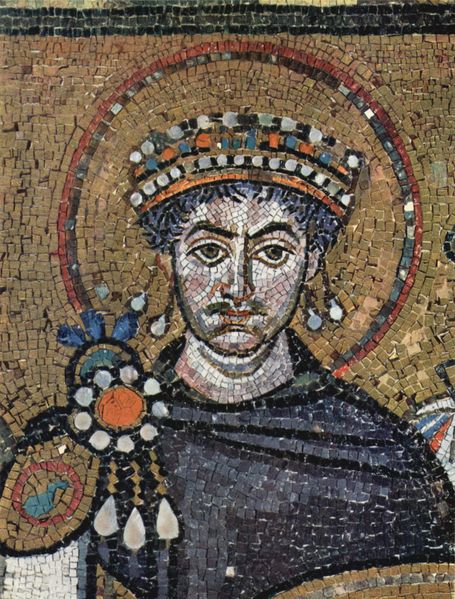

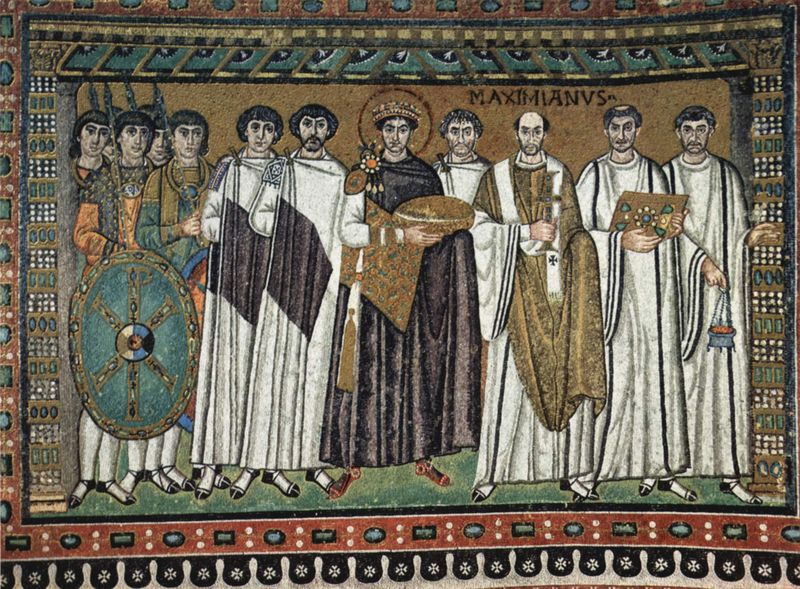

longer a Western Roman emperor). Mosaic of Justinian I

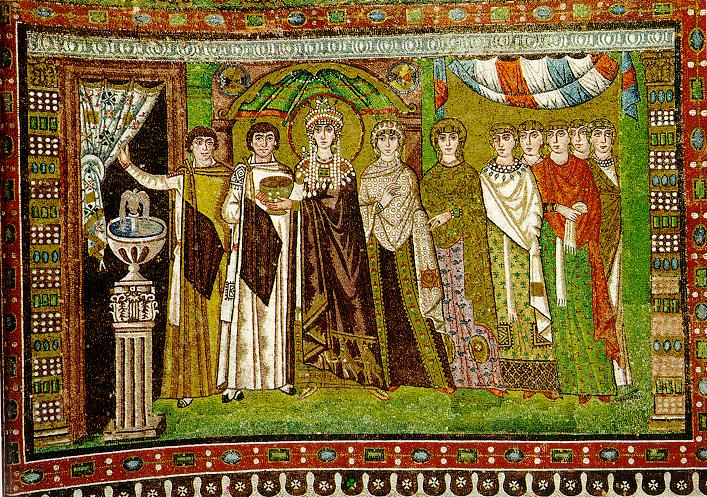

Detail of a portrait in the San Vitale, Ravenna The Nika riots (532). The first five years of his rule were uneasy. Constantinople was a rough place. Political factions confronted each other in increasingly violent fashion (something like modern urban gangs). The biggest outlet was the chariot races – which provided the opportunities for gangs (principally the Greens and the Blues – backed also by influential members of the Senate) to vent. Justinian had been trying to keep order – though he was not popular, having raised taxes in an attempt to straighten out the finances of state. His wife Theodora was an object of ridicule – having been an actress and a well known courtesan of humble birth (but as events would soon prove, was an exceptionally capable individual). In early 532, just as he was negotiating a (very expensive: a one time Roman tribute of 11,000 pounds in gold) "eternal" peace with Sassanid Persia, riots broke out in the city. This would prove to be the worst that the city was ever to see. It occurred over the arrest of two Blue and Green individuals recently involved in murderous chariot riots. The city was convulsed by even greater rioting – and the imperial palace was blocked off for five days. The crowds were taunting Justinian – who was turning to the idea of fleeing. But Theodora stiffened his resolve with her words: “those who have worn the crown should never survive its loss” and “Royalty is a fine burial shroud.” She would rather be dead than flee. And so he faced down the crowd – and unleashed his general Belisarius (who would serve him loyally during his reign) on the rioters in the Hippodrome (race track). In the end, half of Constantinople was burned to the ground and 30 thousand people killed before the riots were finally suppressed (and many Senators plus a pretender to the throne executed). But his rule was now secure. Mosaic of Theodora

Detail of a portrait in the San Vitale, Ravenna War against the Germans: First period (533 540). The next year (533) he sent Belisarius to begin the reconquest of lost Roman territory in Africa held by the Vandals. This he did fairly easily. Two years later (535) Sicily was retaken – and Belisarius (eventually joined by Narses) then turned his attention to Italy and the Ostrogoths. This took longer, five years, and involved some reverses as well as advances. But in the end (roughly by 540) he had pried Italy loose from the Gothic grip – and even held the well defended Ravenna, which became the Byzantine capital in the West. The plague of 541 543. The empire hit violently by a plague which left it greatly depleted of manpower. At its height the plague was killing 10,000 people a day in Constantinople (so the contemporary chronicler Procopius reports). The depopulation of the empire not only cut back on the empire's tax sources at a time of huge need (and saddling the survivors with huge new taxes) the loss of manpower also made the empire an easier target for its enemies. The plague would return – in wave after wave – causing in Europe a population loss of probably more than 50% over the next century (but after 750 the plague would not reappear in Europe until it broke out again in the mid-1300s as the Black Death). War against the Persians (540 562). Troubles with Sassanid Persia continued throughout this period. Seeing that the "eternal" peace was giving his Byzantine rival the opportunity to increase Byzantine power by retaking lost Roman territory in the West, Persian king Khosrau in 540 decided to end the truce with Rome. He invaded Syria – all the way up to the Mediterranean – and looted Antioch, and took its inhabitants back to Persia as prisoners. Roman Persian relations continued with periods of war, truces and then more war until 562 when Persia and Byzantium agreed to a 50 year peace (which cost Rome an annual subsidy of 5,000 pounds of gold). War against the Germans: Second Period (544 554). Meanwhile the Ostrogoths were experiencing something of a comeback in Italy. General Belisarius was sent again to Italy in 544 – with mixed results. Rome was attacked by the Ostrogoths several times, retaken by the Romans several times – and slowly reduced in population to a pathetic state. In 552 the Ostrogoths were finally defeated by a major Roman force and two years later an invasion of Italy by the Franks was turned back. Italy was thus back in Roman (Byzantine) hands – but at a cost that the Empire was not really prepared to pay. At the same time, Inter-tribal German war in Spain in 552 brought the Romans to that region, retaking for the Roman Empire a section of southeastern Spain. Then it was also during this period that Slavic and Turkic invaders began raids into the Danubian provinces (across the Danube). Finally in 559, the aged general Belisarius was able to drive back a group of Turkic Avars who attempted to occupy the area. Religious and civil activities. Both Zeno and Anastasius had been relatively tolerant of the Monophysites (condemned at the Council of Chalcedon in 451) – a matter of great irritation to the bishops of Rome. Justinian ended the toleration in an attempt to force religious unity in his empire – and peace with the bishops of Rome. His wife Theodora however was a Monophysite sympathizer and eventually, toward the end of his reign Justinian became more tolerant of them. This role of the emperor in religious affairs pointed out to a widening difference between Eastern and Western Christianity. In the West, the bishops of Rome were clearly the leading authority of the church. Their influence, and at times even dominance, over the German tribal kings was also great. But in the East, the authority of the emperor was paramount. The patriarchs of the Eastern Churches (particularly Constantinople, Antioch and Alexandria) were powerful – but not dominating. Domination belonged to the eastern emperor – in religious as well as civil policy. Justinian and Theodora were active supporters of the church, creating rules for the management of foundations, monasteries, episcopal (bishop) elections, etc. Justinian built and repaired churches (such as the burned out Hagia Sophia in Constantinople which he actually had rebuilt) at great cost to the imperial treasury. |

The Emperor Justinian I and the Empress Theodora

MOUNTING

PROBLEMS AFTER JUSTINIAN |

| By

the end of his reign in 565, Eastern Rome was at relative peace. But

beneath the surface lurked serious problems. The ancient and on

going wars with the Sassanid Persians to East had reached new levels of

violence and were draining the energies (and tax sources) of the

Byzantine Empire. [These wars were also draining the energies of

Sassanid Persia.] The state treasury was depleted, even

though taxes were enormously high. Subject peoples within the

Byzantine Empire were getting very restless under this heavy tax burden. Also, this situation was made only worse by the tendency of the imperial capital Constantinople to want to stamp out various Christian "heresies" widespread around the further reaches of the Empire – especially among the non-Greek peoples of the Eastern and Southeastern Mediterranean borderlands. The concerted effort of the authorities in Constantinople to stamp out these heresies resulted only in alienating the people of these outlying regions all the more. As a result, by the beginning of the 600s much of the Eastern Roman Empire was also exhausted and restless – physically, morally and spiritually. At the same time Rome's enemies were simply waiting for an opportunity to find a point of weakness where they could start again their assault on the empire. His immediate successors

Thus Justinian's successors had their hands full. Power changed hands fairly peacefully, to his nephew, Justin II (565-578), then to Justin's capable general Tiberius II Constantine (578-582), and his general Maurice (582-602). They attempted to restore the empire's finances, yet at the same time keep at bay the troublesome Germanics, Avars, Slavs and Persians. The Avars, Slavs and the Persians

Tiberius focused what was still available of Roman military might in Eastern Rome's on going struggle with Persia. He tried to buy peace with the Avars with extensive subsidies – but the Avars, seeing the desperate situation of the Romans, continued their expansion into the southern Balkan peninsula (just northwest of Constantinople). Tiberius's successor, Maurice, had helped a Persian claimant, Khosrau II, to the Persian throne – and thus secured something of a peace with Persia, one which lasted until Maurice's death in 602. This freed up Rome so as to be able in 602 to push the Avars and Slavs back across the Danube. Phocas (602-610), Heraclius (610-641), and the Persians

But Maurice's effort to restore state finances by cutting costs outraged his troops along the Danube, troops who felt unsupported in their efforts to hold the Avars and Slavs and who thus rose up in revolt. Under the leadership of a general Phocas they marched on Constantinople in protest. The Greens of Constantinople declared Phocas emperor and Maurice fled, was soon captured, and then executed. At first Phocas" rule was greeted with hope for an easing of the heavy financial and religious burdens felt by the ordinary citizen. But with the withdrawal of the Roman troops from the Danube area, the Avars and Slaves once again became a serious threat to Constantinople. Worse, his overthrow of Maurice offered Khosrau the pretext to renew the Persian war with the Byzantines, at a time when Byzantine power was at a very low point. Using a Persian supporter pretender to the throne, Theodosius, as the focus of their cause, Khosrau invaded Roman territory in northern Mesopotamia – and then proceeded to conquer much of Asia Minor and Syria (608). At this same time Heraclius started a revolt against Phocas originating in Africa – and then spreading to Egypt (609) and then up to Constantinople (610) – where he received little resistance and Phocas was quickly arrested and executed. But Heraclius" accession3 (he was the first of a long series of Byzantine rulers to entitle himself Basileus or "monarch" rather than Augustus or "emperor') did not shake Khosrau from his cause to install Theodosius as emperor. The Persians pressed forward against a very exhausted Rome, taking Damascus (613), Jerusalem (614) and Egypt (618). At one point they even raided all the way into Asia Minor almost just across from the city of Constantinople itself. A stunned Heraclius finally gathered a Roman army and took to the field himself against Persia in 621. He also gathered allies among the Turks and took advantage of a political division within Persia itself to weaken Persian resistance. In 627 he was able to crush the Persian army at Nineveh. Khosrau still refused to make peace and Heraclius marched onward to the Persian capital Ctesiphon (628). At this point Khosrau was deposed by his people and their newly appointed king, Kavadh II, made peace with the Romans, restoring to them the territory seized by Khosrau. But the war left the Persians exhausted. And it produced the same effect on the Romans. An exhausted peace reigned over both lands. 3Heraclius was the first of a long series of Byzantine rulers to entitle himself Basileus – meaning monarch or king – rather than Augustus or emperor.

The Church of Hagia Sophia ("Holy Wisdom") in Constantinople (today's Istanbul) built in 537 during the reign of Justinian (the minarets were added by the Muslim conquerors after the mid-1400s) Miles Hodges     The interior of the Hagia Sophia Miles Hodges

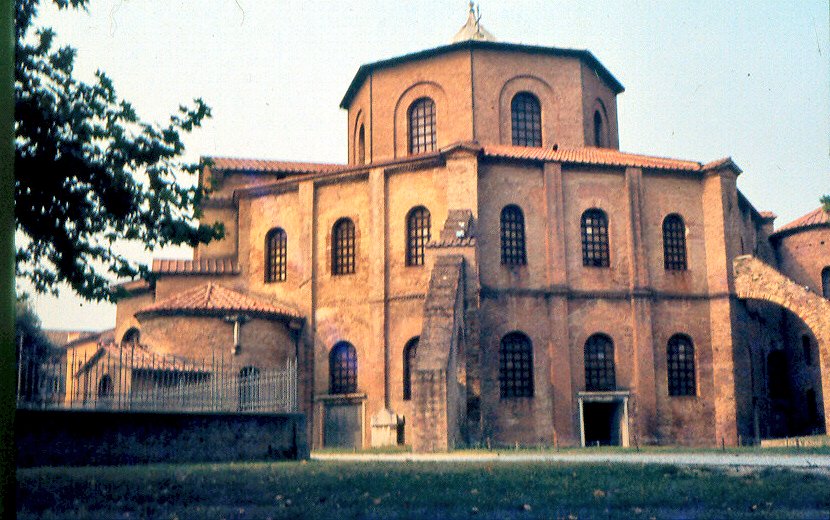

Sant'Apollinare

– Ravenna

Sant'Apollinare interior

– Roman-Byzantine style

The apse of Sant'Apollinare – Ravena

The Enthroned Christ and Four Angels

- Sant'Apollinare - Ravenna

The Three Wise Men - Sant'Apollinare –

Ravenna

Go on to the next section: Islam and the West

|