5. INTO THE "DARK AGES"

THE ROMAN CHURCH SURVIVES IN THE WEST

CONTENTS

The Church survives: an overview The Church survives: an overview

Patrick: Missionary to the Irish Patrick: Missionary to the Irish

Noble Roman churchmen lay strong Noble Roman churchmen lay strong

foundations in the West

The Christian (mostly Irish) missions to The Christian (mostly Irish) missions to

the Germanic tribal nations

The textual material on the page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 179-185.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

432? Celestine sends Patrick to Ireland

after Palladius's failure

440 Pope Leo I (440-461) makes apostolic

claim to primacy ... through Peter's

having founded the church at Rome (the principle of "apostolic

succession")

500s Benedict of Nursia (early 500s)

writes the monks' Benedictine Rule

563 Irish evangelical Columba founds monastery at Iona

… starting the process of bringing Scotland to Christianity

Irish evangelical Columban (late 500s) goes to Gaul,

Switzerland and Italy

590s Pope Gregory I (590-604) organizes

church discipline and charity

But also negotiates a peace with the Lombards

597 Gregory sends Augustine to Kent

to bring Saxons to Trinitarian faith

634 Irish evangelical Aidan founds monastery at

Lindisfarne

663 The Synod of Whitby (663-664)

establishes papal (Roman Catholic) rule in Britain

Cuthbert soon changes Lindisfarne

from Irish evangelical to Roman Catholic

THE CHURCH

SURVIVES: AN OVERVIEW |

In

the West it was a very hard time. There was no reliable order in

the land, and road and sea travel became very dangerous. Trade and

industry ground to a halt. Urban life withered away to

nothing. Even the population dwindled rapidly in size.

People became dependent on a local tribal leader for protection – whose

fortified domain offered some small amount of protection against

wandering bands of trouble makers.

Politically, the city of Rome was now irrelevant, as what was left of

the Roman imperial order in the West was supervised now out of Ravenna,

in the north of Italy.

However, although Roman politics and economics collapsed under the

German conquests in the Western portions of the Empire – the Roman

religion, Catholic Christianity, did not. Indeed, Christianity

became the all important carrier in the West of what was left of Roman

civilization: in the social organization of the church, its bishops and

popes, and in its use of Latin in worship and study.

A number of Bishops of Rome (later termed “Popes”) – most notably Leo I

(pope: 440-461) and Gregory I (pope: 590-604) – managed to preserve and

strengthen what little remained of Roman or Latin moral-cultural order

in the West. Indeed, the church of Rome not only survived the

Germanic impact but converted some of the most important tribes to

Roman Christianity and

restored the city of Rome to a position of some degree of

religious-cultural importance – at least within the West itself.

Admittedly this was not very glamorous by comparison to what Rome once

was.

Closely connected with this survival of the Christian church was also

the monastic movement which at the time of the fall of Rome in the

early 400s was widespread. Numerous monks and priests at the

local level acquitted themselves fairly honorably along these same

moral-cultural lines, especially once the monastic movement had been

disciplined by Benedict (early 500s), whose rule was widely honored

throughout the West. Indeed, missionaries sent out by the Irish

monasteries (thanks to Patrick, who brought Christianity to Druid

Ireland in the early to mid-400s) helped to bring to the German (and

Celtic) tribesmen to the East of them in Great Britain and on the

European mainland important aspects of the Roman Latin Christian legacy

that otherwise would have been lost entirely to Western Europe.

|

PATRICK (389

- 461) MISSIONARY TO THE IRISH |

Patrick

served as amissionary to the Irish for some thirty years. It is

claimed that in that time he brought the nation to Trinitarian or

Catholic Christianity, establishing over 300 churches and baptizing

over 120 thousand Irishmen.1 Patrick

served as amissionary to the Irish for some thirty years. It is

claimed that in that time he brought the nation to Trinitarian or

Catholic Christianity, establishing over 300 churches and baptizing

over 120 thousand Irishmen.1

He was not himself Irish but British – developing a familiarity with

this isolated Celtic island when taken there as a young British slave

in 405. He escaped after about 6 years of hard and dangerous

service – and made his way back to his home in Britain, rejoining his

family, but shocked to find the land itself devastated by the Germans

during his absence in Ireland. He journeyed to southern France to

become a priest – and was serving there when God called him to return

to Ireland to bring that fierce Druid nation to Christ. But he

was passed over by Celestine, Bishop of Rome, recognized as the person

with the ultimate authority for such decisions. Celestine

appointed another priest to the task. But that mission was not

successful – and finally Celestine commissioned Patrick for the task.

This was a wise choice since Patrick was one who knew the Irish well,

and had an incredibly fearless heart. He well knew the power of

the Druid priests – and the importance of winning the respect of the

Irish chiefs. He also was aware of a ancient Irish prophecy well

known to all in Ireland that heralded the arrival of a small group of

foreigners attired and adorned almost exactly as he and his small group

of missionaries. He was ready to challenge the Druid priests (the

exact detailed have become so "expanded" in the retelling that it is

impossible to know what really happened). In any case he

succeeded in impressing the Irish chiefs – and was allowed to establish

himself in Armagh as the nation's first bishop.

From this key spiritual center he began to involve himself in the

political affairs of the nation – even intervening to protect Christian

Irish from raids by British Christians. But he was no less

involved in the social life of the country, establishing schools and

monasteries throughout the country to raise the level of learning of

the nation. Under his direction Irish monks began translating

works from the Greek and Hebrew and developing libraries of

considerable importance. But most of all he looked after the

spiritual needs of Ireland – leading the nation into a wholesale

embrace of Christianity.

The irony is that just as Roman Europe was undergoing a terrible

cultural eclipse caused by a general Germanic darkness – Ireland was

undergoing quite the opposite in the form of a true cultural

awakening. As the lights began to go out in the continental West,

in Ireland they began to burn – burn brightly.

Eventually it would be the Irish who would go forth as missionaries to

Germanic Europe – in an effort to restore Roman Catholic culture where

they could.

For more on Patrick For more on Patrick

1What we know of Patrick comes from parts of his personal testimony, Confessio and also from his Letter to the soldiers of Coroticus.

We do not know exactly the dates of his birth or death however ...

although certainly he flourished in the mid-400s. His name

"Patrick" came from the Latin, Patricius ... perhaps derived from the

fact of his own British-Roman ancestry.

NOBLE ROMAN

CHURCHMEN LAY STRONG CHURCH FOUNDATIONS IN THE

WEST |

|

Leo I "the Great" (pope: 440-461)

Leo

I, the bishop of Rome played the most important hand in tightening

church organization in the West at a time that Roman political order

was disintegrating there. During his tenure as Bishop of Rome he

became the unquestioned head of the Western church – that is,

"pope." The other bishops, especially the North African bishops,

simply declined in importance or even disappeared from view as the

German tribal leaders undercut the bishops" power bases. Leo

I, the bishop of Rome played the most important hand in tightening

church organization in the West at a time that Roman political order

was disintegrating there. During his tenure as Bishop of Rome he

became the unquestioned head of the Western church – that is,

"pope." The other bishops, especially the North African bishops,

simply declined in importance or even disappeared from view as the

German tribal leaders undercut the bishops" power bases.

Early on, Leo lined up the other bishops of Italy and North Africa

behind his lead in driving out of the church a number of heresies that

were drifting into the faith. Later, with the help of the Western

Emperor Valentinian III, he was able to draw a resistant church of Gaul

(France) under his authority. And when Attila and his Huns

threatened Rome it was Leo who met him and got him to withdraw his

troops, making him the primary political figure in Italy.

He was unabashed in his view that the Bishop of Rome was the head of

the church – not only in the West but in the church universal. He

based his claim on the logic of being of the apostolic line of

succession descending directly from Peter, the first Bishop of

Rome. His claim was not accepted in the East – though he

certainly was respected there. But his claim went unchallenged in

the West. From Leo's time on, the Bishop of Rome was acknowledged

in the West as the "pope," the head of the Roman Catholic Church.

|

The meeting of Pope Leo and Attila - by Raphael

the Vatican

Benedict of Nursia (480-547) Benedict of Nursia (480-547)

In

the early 500s an Italian aristocrat-turned-monk, Benedict, founded

some fourteen monasteries (the first and most important at Monte Casino

in Southern Italy) and then laid out for the good order of these

monastic communities his Benedictine "Rule." This proved so

successful that it was widely copied among abbeys or monasteries

throughout the West. His Rule served to give form and strength to

the monastic movement. Indeed, over time, resulting from such

order and discipline, these monasteries themselves grew very rich.

Gregory I "the Great" (born: 540 / pope: 590-604)

Gregory

was chiefly responsible for reorganizing the structure of the Western

Church – giving it the broad features that it would have for the rest

of the Middle Ages – and indeed, through the on going Roman Catholic

Church, even down to the present. Gregory was born of a noble or

"patrician" Roman family – a family possessing not only great wealth

but also a distinguished placement in the Christian community as a

family of deep Christian devotion. As a youth Gregory received

the typical patrician schooling at which he proved to be highly

accomplished. He eventually stepped into a public career (as

would have been expected of one with his family background) and by his

early 30s he had become the prefect of the city of Rome. Gregory

was chiefly responsible for reorganizing the structure of the Western

Church – giving it the broad features that it would have for the rest

of the Middle Ages – and indeed, through the on going Roman Catholic

Church, even down to the present. Gregory was born of a noble or

"patrician" Roman family – a family possessing not only great wealth

but also a distinguished placement in the Christian community as a

family of deep Christian devotion. As a youth Gregory received

the typical patrician schooling at which he proved to be highly

accomplished. He eventually stepped into a public career (as

would have been expected of one with his family background) and by his

early 30s he had become the prefect of the city of Rome.

But soon

thereafter he abandoned his public life and took up the vow of poverty

in becoming a monk. Eventually his family inheritance of

considerable landholding he turned to use as the site of a number of

monasteries. But Pope Pelagius II pressured him to come out of

seclusion and first had him appointed as a deacon of Rome and then as

papal ambassador to the Eastern Roman or Byzantine court in

Constantinople.

Here he revealed his highly organized mind in a

controversy he had with the Eastern Patriarch – a controversy in which

the Emperor eventually placed himself squarely on Gregory's side of the

argument. Eventually he was returned to Rome and soon became

abbot of St. Andrew's monastery – where he also became a widely

respected teacher of the Scriptures. But he became fascinated

with the idea of becoming a missionary to the Anglo Saxons of Britain –

but at the insistence of a very upset Roman populace was recalled to

Rome shortly after his departure. Under a promise never to leave

Rome, he soon became a special assistant to Pelagius II. But he

never lost his fascination for the idea of a mission to the Anglo

Saxons of Britain.

In 590, during the middle of a horrible plague which had followed upon

equally devastating floods, Pelagius II died – and the unanimous Roman

choice for pope went to Gregory – who nonetheless did what he could to

duck the responsibility. Nonetheless the Eastern Emperor

confirmed the appointment and Gregory was forced to take up the

position as bishop of Rome (pope).

Soon after his accession to the papacy, he began to demonstrate his

brilliance as a church administrator (including the management of the

vast land holdings of the church, which he used generously to support

the poor) – and as a dominating authority throughout the whole

Christian world. With respect to church organization, the

personal behavior of priests and bishops, and the handling of church

monies, he was deeply demanding of papal discipline throughout the

ranks of the church. He even claimed authority over the Patriarch

of Constantinople, insisting that the church at Rome was the true

Apostolic See.

He also drew the church into active politics – particularly when it

became evident that the Byzantine Emperor was not going to do anything

to stop the advancement of the Germanic Lombards across Italy.

Gregory not only appointed a new tribune to Naples to organize that

city's defenses against the Lombards but eventually entered directly

into negotiations with the Lombards for peace in Italy.

He finally had a chance to fulfill an old dream of sending a mission to

the Angles in Britain – sending Augustine of Canterbury to begin the

conversion of the Angles and Saxons in Britain. He also worked closely

with the monastic movement reformed by Benedict – by drawing

monasteries more closely into the ecclesiastical system that he

presided over and disciplining it according to his strict standards ...

and at the same time acting as a protector of the monasteries against

the efforts of bishops to bring these monasteries under their own

control.

|

THE CHRISTIAN

(MOSTLY IRISH) MISSIONS TO THE GERMANIC TRIBAL NATIONS |

The

monasteries (found significantly in unconquered Celtic Christian lands

in Ireland and Britain) became very important pockets of learning in

this dark Germanic world – sending out missionaries to the German

tribes, converting them to Catholic Christianity, planting new

monasteries in their midst and keeping the hope of a better world alive.

These monasteries were not under papal control – nor was there any real

"order" to them – but they provided a refuge for people who wanted to

devote themselves to God and serve their fellow man in charity

(something utterly lacking in the Roman Empire).

The most influential of these monastic havens within this darkened

Germanic world – perhaps because they were furthest removed from the

impact of the Germanic invasions – were the Irish monasteries started

up by Patrick. They not only kept the flame alive, but sent out

missionaries in the 500s and 600s to establish monasteries in the

Netherlands, France, Burgundy, Saxony, and Italy.

Columba (521-597)

Columba was a monk and missionary, known also by his Irish nickname,

Columcille (‘Dove of the church'). After his banishment from

Ireland for opposing the King he and 12 of his disciples founded in

Scotland the missionary settlement at Iona (563) – which became the

launch site for bringing Scotland into the Christian faith.

He had also been very active in shaping the Irish church in his earlier

years, founding several hundred churches and monasteries in Ireland as

well. And even after establishing himself in Iona he remained

active in Irish affairs, helping to shape the governmental structure of

Ireland at the council of Druim Cetta in 575.

Columban (c. 540-615)

Columban was another Irish monk who in 591 (at age 50+)

traveled with 12 of his disciples to the European continent, to the

Burgundian kingdom (in Southeastern Gaul or present day France) to

establish monasteries among the Celtic Gauls. But his strong

disapproval of the lax moral and spiritual conditions within the

Burgundian government and Roman church in that region brought him under

attack. In 610 (at age 70!) he was forced out of Burgundy.

He eventually settled in Switzerland to preach the faith to the pagan

Alamanni – though he was soon chased from this region as well because

of his having chopped down sacred pagan trees and because of a

continuing conspiracy against him in the courts of Theodoric II.

Thus he moved south into Italy (c. 612 614) and established a monastery

at Bobbio, where he died a short time later.

In his sermons, teachings, writings and personal example, he left a

legacy of spiritual integrity and vitality which gave inspiration to

Christians generations after him.

Augustine of Canterbury (? - c. 605)

Augustine was sent by Pope Gregory from Rome (where he had

been prior of a Benedictine abbey) to England to convert the Anglo

Saxons to Catholic Christianity. Augustine arrived in Kent in 597

accompanied by 40 monks. Kentish King Ethelbert was supportive of

Augustine's mission and gave him a place at Canterbury to base his

mission.

Augustine's mission proved to be highly successful. Ethelbert and

thousands of English were brought to the faith in the first year

alone. Within a few years a number of other missionaries were

sent to England to assist Augustine, including 12 bishops – over which

Augustine presided as archbishop. His church (Christ Church) was

recognized as the cathedral for England.

Aidan (?-651)

Aidan was a humble Irish monk at Iona, when he was

consecrated in 635 as bishop and sent to evangelize the English under

King Oswald (and King Oswin who succeeded Oswald in 642) in

Northumbria. Just off the Northumbrian coast, Aidan established

the mission center of Landisfarne for the training of more missionaries

to the English, including the brothers Chad and Cedd (missionaries to

the Mercians and East Saxons respectively) and Hilda (founder of a

number of monasteries, including the notable monastery of Whitby in

Northumbria, England).

The Synod of Whitby (663-664)

One of the growing questions of the day was whether these missions

ought to remain independent, or at least connected solely to the

sending authorities back in Ireland – or whether they ought to

affiliate themselves with the Bishop of Rome (the Pope). This was

both a cultural and political issue. Would they follow Celtic or

Roman patterns of church organization and life? Would they

preserve their autonomy or submit themselves to the Roman religious

order? Thus English Christians convened at Whitby to come to some

kind of a decision. Ultimately the decision was made in favor of

the Roman formula.

Cuthbert (634-687)

Cuthbert was profoundly spiritual and humble Celtic monk who entered

Melrose Abbey as a youth, became very close to its prior, Boisil, and

succeeded him in 661 after a plague killed Boisil. Cuthbert

quickly gained a reputation as a miracle worker after he went about the

countryside praying for and treating plague victims.

When after the decision of the Synod of Whitby to adopt Roman and drop

Celtic church traditions (a decision which Cuthbert supported) Colman,

who had been a leader of the Celtic position, resigned his post as

prior of Lindisfarne. Cuthbert was invited to take his

place. As prior of Lindisfarne, Cuthbert supervised the

changeover from the more informal Celtic to the much more highly

structured Roman church style.

But Cuthbert had more a heart for quiet piety than for administrative

duties. In 676, searching for solitude, he ventured to the Farne

Islands and established himself in a hermit's cell there.

However, his fame would not go away. He was recalled briefly as

prior of Lindisfarne and then once again retreated to the Farne Islands

where he lived out his days in prayer.

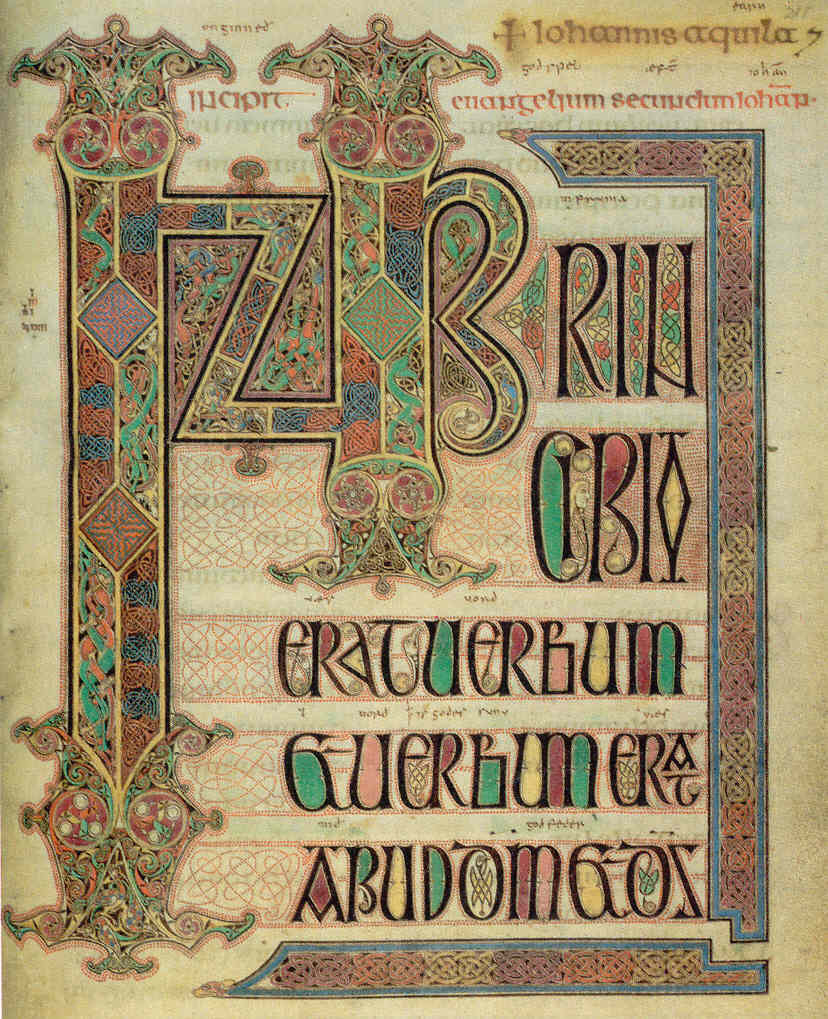

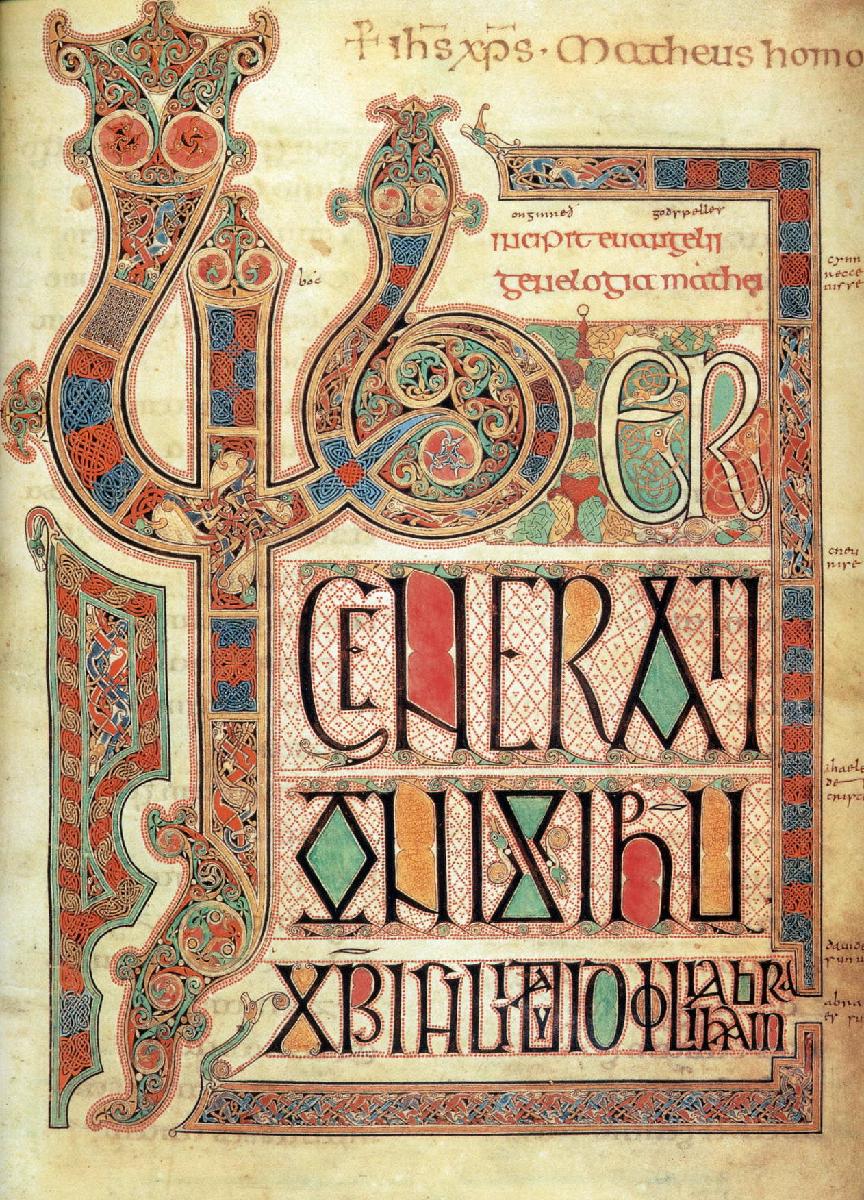

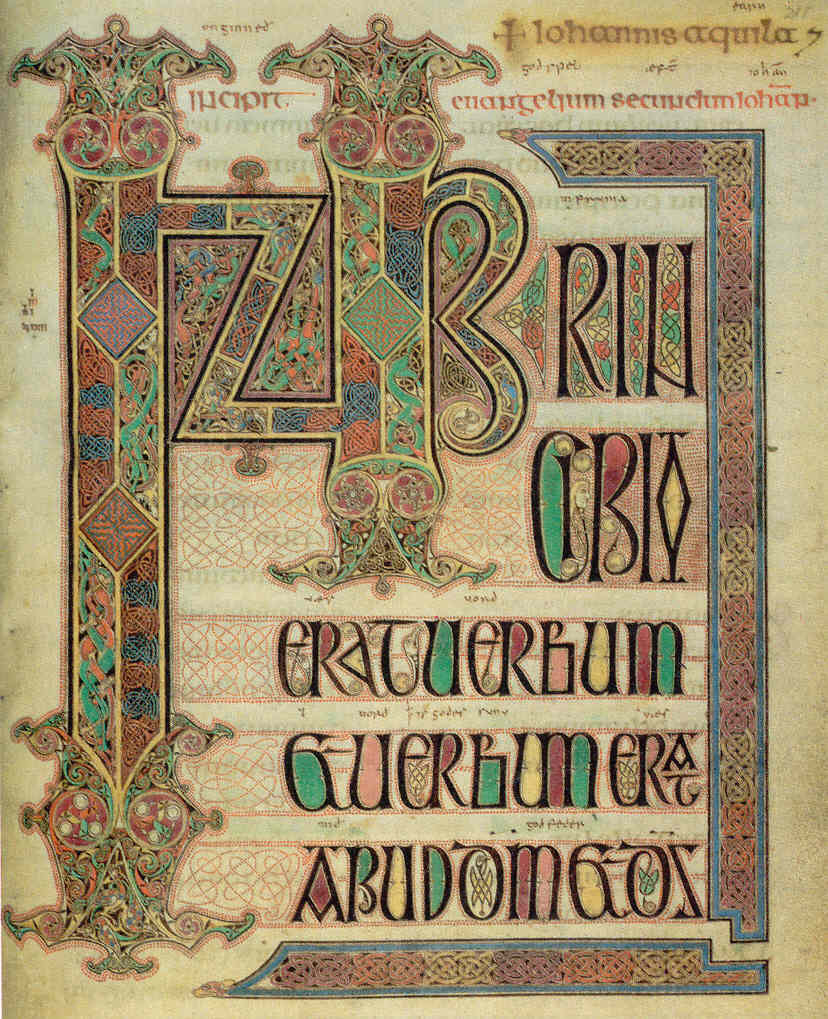

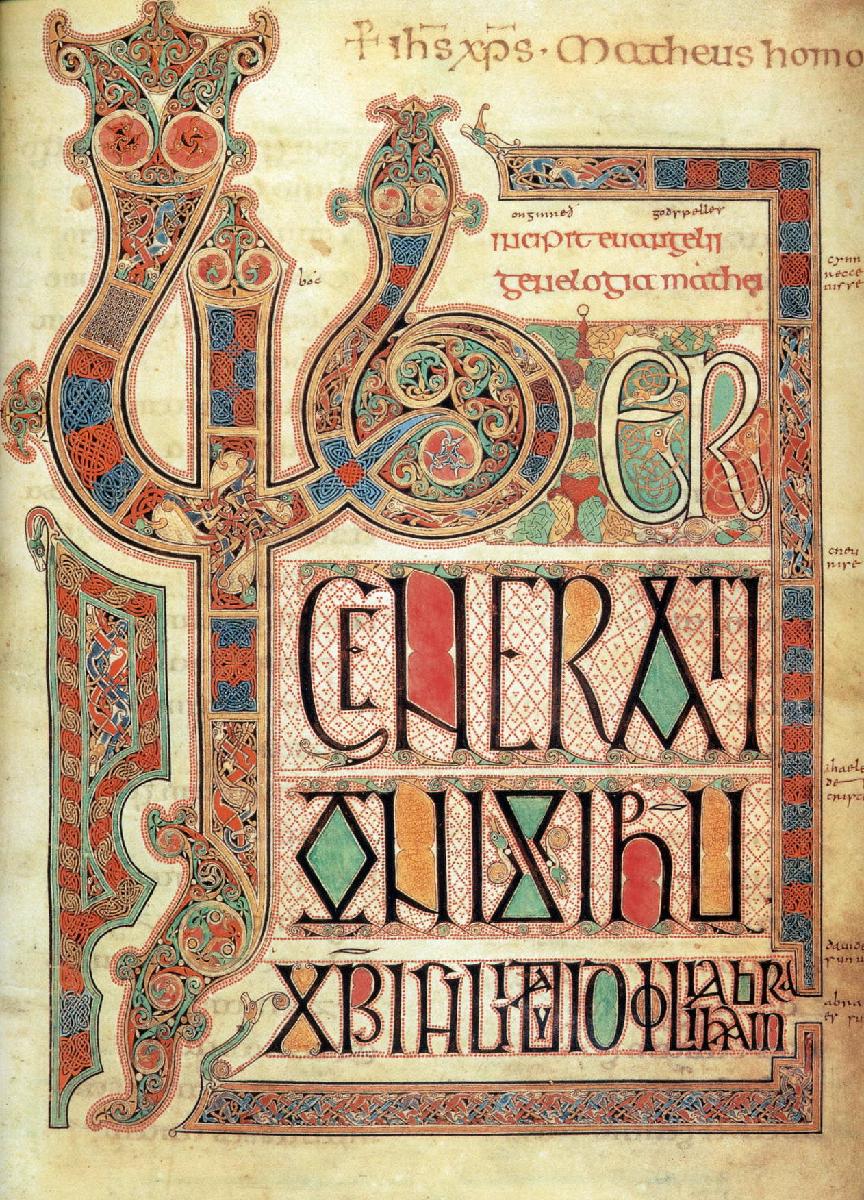

So well-loved was Cuthbert that the beautiful Lindisfarne Gospel

(a treasure today of the British Library!) was published by Bishop

Eadfrith of Lindisfarne in Cuthbert's honor shortly after his death.

|

The Lindisfarne Gospel: The beginning of the Gospel of John – c. 698-700

The British Library

Page from the Lindisfarne Gospels

London, British Museum

Silver and gold-plated bronze chalice from Ardagh (700s)

Dublin, National Museum of Ireland

Go on to the next section: Byzantine Rome

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

The Church survives: an overview

The Church survives: an overview

Patrick: Missionary to the Irish

Patrick: Missionary to the Irish

Noble Roman churchmen lay strong

Noble Roman churchmen lay strong The Christian (mostly Irish) missions to

The Christian (mostly Irish) missions to