5. INTO THE "DARK AGES"

GERMANIC WESTERN EUROPE

CONTENTS

The invading / migrating German tribes (cl 375-568) The invading / migrating German tribes (cl 375-568)

Some of the Germanic "Greats" Some of the Germanic "Greats"

The textual material on the page below is drawn directly from my work

A Moral History of Western Society © 2024, Volume One, pages 165-179.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

258 Salian Franks invade in

the lower Rhine region …

then are permitted to settle northern Gaul as "foederati"

267 Goths cross the Danube and sack

Byzantium

The Goths are gradually Romanized and

Christianized ... but as Arian Christians

They are allowed to settle across the Danube as refuge from the Huns

378

But they are treated poorly – leading to

Fritigern's rebellion

Saxons from the shores of

northern Germany take control of the lower Rhineland from the

Franks

410 Saxons cross to Britain after Roman troops are withdrawn to fight Alaric

They then come in number to Britain under British king

Vortigern ... to help fend off the Pict invaders from Scotland (mid-400s)

After Alaric, Visigoths settle

southern Gaul with their capital at Toulouse

...

then move into northern Spain against the Suebi and

Vandals

428 Gaiseric leads thousands of

Vandals from Spain to North Africa (428-430)

"vandalizing" as they go (Augustine also dies as a result)

455

Gaiseric leads his Vandals on a similar

attack on Rome

The Roman navy is unsuccessful in

its counter-attack on the Vandals (468)

466 Under Euric (466-484) the Visigoths also rule

much of France

The Alemanni settle in today's

Alsace and the upper Rhineland

The Burgundians settle

southeastern Gaul

476 Roman "patrician" Odoacer

and his foederati bring Italy stability to

Italy

Frankish king Childeric (r.

458-481) allies with Odoacer in extending Frankish

power into Alemanni

territory (Upper Rhineland)

488 Ostrogoth Theodoric fights Odoacer

for control of Italy (488-493)

490s Theodoric murders Odoacer (493); Ostrogoths

take control of Italy

But will lose that position under

Byzantine Emperor Justinian (535-554)

All of Gaul is brought to newly

Trinitarian Frankish rule under Clovis (r. 481-511)

also establishing the Merovingian dynasty ... which rules under the feudal

system ... assisted by powerful "mayors of the

palace"

500 Saxon spread is stopped by the

Celts at the battle of Mons Badonicus (c. 500)

possibly the basis of the tale of King Arthur and his court at Camelot

565 But Saxon expansion resumes under

Aethelberht of Kent (r. 565-616),

driving the Celts into Wales and Cornwall

Papal missionary Augustine brings Aethelberht

to Trinitarianism

568 Lombards begin to migrate under

Alboin to Northern Italy

580 At this point hundreds of thousands of Lombards are in

northern and central Italy

But the pope was able to maintain his

independence …

in part due to Lombard lack of political unity

616 Northern Britain is brought under

rule of Edwin of Northumbria (616-632)

… beginning the

"Christianizing" of that huge region

THE INVADING / MIGRATING GERMAN TRIBES (c. 375 - 568) |

|

The Early days of the German intrusion into the Roman Empire

The Germanic tribes migrating into central Europe from the Northeast

(under pressure from the Asian Huns coming in from further East) had

found the eastern half of the Roman Empire a solid barrier to

expansion. But as they slid west, they found a very different

dynamic: only a very weak Rome trying to hold its own ... an easy

pickoff.

Within the Roman Empire there was very little stopping them.

Whole regions seemed largely deserted, either because the inhabitants

had fled before the approaching tribal groups, or because the owners

had abandoned their farms even earlier due to economic failure.

Other groups such as the Celts of Britain (and Gaelic Brittany) tried

to hold out from mountainous regions they had escaped to. Others

just simply allowed themselves to be integrated into the

social-political complex of the invading tribe. In any case, by

500 it was accurate to say that there was no longer a Roman Empire in

the West. Rather the region seemed to be a loose patchwork of

various tribes – themselves often in contention for dominion in the

land.

It is clear that the German "barbarians" did not produce the Roman

collapse. They merely moved into the Roman political vacuum in

the West once they understood that it was there, that there was no

longer any real Roman counter pressure to hold them back as they

scrambled for grazing and farming lands for their own growing

populations. When they did move into the Roman domains, they

attempted to capture the glory of the Rome that they once envied.

But it was no longer there to be grasped. In consequence their

own traditional ways took over where they settled.

The Goths (Visigoths and Ostrogoths)

In the East – along the Danube River near the Black Sea – it was the

Goths who first troubled Rome, crossing the Danube in 267 to sack

Byzantium (well before it became Constantine's capital city).

They were eventually driven back across the Danube – but allowed by

Aurelian to settle in the old Roman province of Dacia (north of the

Danube) which the Romans had abandoned – establishing a Gothic kingdom

there. At this point some of the Goths were entered into the

ranks of the Roman armies.

In the early 332 Constantine attacked and crippled the Gothic kingdom –

and then settled Sarmatians just north of the Danube in order to act as

a buffer to the Goths. But then two years later he expelled the

Sarmatians after they revolted against Roman authority.1

Gradually the Goths were Romanized – and brought into Christianity as

Arians. And the ranks of the Roman armies were composed heavily

of Germans.

With the appearance of the Huns into the area (376)

the Goths were given permission to settle on the south side of the

Danube. But (as we saw above) they were treated shabbily (no

famine relief) and, led by Fritigern, rose up in revolt – leading

eventually to the Battle of Adrianople in 378 in which the Emperor

Valens was killed and the Roman legions decimated.

The Franks

Actually, the first group to enter Roman territory – and take a

permanent position within the Empire – were the Franks (in particular

the Salian Franks). This name probably included a number of

separate tribes located just east and north of the lower Rhine River as

it enters the North Sea. During the 200s they raided deep within

Roman territory on several occasions (even reaching Spain during a raid

in 250) before being expelled by Roman forces. They settled the

lower reaches of the Rhine (today's Netherlands) where they raided

shipping to Britain. Finally they were settled down by the

legions – though not removed from the territory.

In 258 Salian Franks were permitted to settle in northern Gaul as

"foederati," offering military service to Rome in exchange for the

privilege of settling just within the Empire's northern borders (on the

Roman side of the Rhine River). Not much is recorded about them

as they seemed to have caused the Romans no particular concern, mostly

serving to protect the northern borders of the Empire from other

Germanic tribes (including other Frankish sub-tribes ... although more

importantly the more violent Saxons).

Mostly the resettlement program of the Salian Franks worked ... for,

like most of the German tribes, their desire was ultimately to move in

and take for themselves the benefits of higher Roman civilization – not

to destroy it.

They really come into history only with the dazzling conquests of

Childeric and his son Clovis ... who finally succeeded later in

bringing all of Gaul under Frankish rule (late 400s/early 500s)

...forcing the Visigoths to have to abandon to the Franks that portion

of their once-extensive kingdom north of the Pyrenees Mountains.

The Vandals, Alans, and Suebi

With huge pressure coming their way from the Huns – and with the

obvious deep decline of Roman military power in the West – Germanic

Vandals, allied with Iranian Alans, were able to defeat the Franks …

rendering the Franks unable at this point to be able to hold back the

Germanic pressure on the Roman borders. Thus the Vandals and

Alans were able to cross the frozen Rhine at the beginning of 406 and

head westward … plundering as they went.

They soon established themselves in what is today Southern France … but

then in 409 continued even further South into the Iberian Peninsula

(modern Spain and Portugal). Then pressure from the ever-expanding

Visigoths forced the Vandals to move again, this time across the

Straights of Gibraltar (429) … where they then spread themselves

eastward across the north African coast, taking Carthage ten years

later.

Besides the Iranian Alans, another group – the Suebi – accompanied the

Vandals in this sweep across Western Europe, the Suebi finally settling

themselves in the northwest corner of the Iberian Peninsula.

Visigoths

Following Alaric's sack of Rome in 410 the Visigoths settled themselves

in southern Gaul, first as Roman foederati and then as an independent

German kingdom (418) with their capital at the city of Toulouse (in

today's southern France). From this base they would later extend

their domain south across the Pyrenees Mountains into Hispania (Spain)

where they secured their position against the Germanic Suebi and

Vandals who had just moved there, forcing the Suebi to come under

Visigothic rule and, as we have just seen, the Vandals (those anyway

that did not submit themselves to Visigothic rule) to move out of

Hispania and into coastal North Africa.

Ostrogoths

Ostrogoths went their own way under Theodoric, who defeated Odoacer

(who himself had just overthrown the last Western Roman Emperor Romulus

Augustulus in 476) and thus took control of all of Italy and the area

across and north of the Adriatic Sea. The Ostrogoths assumed

Roman character as much as possible and brought a degree of political

strength back to the lands they ruled. But in the mid-500s they

fell before the expansionistic program of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine)

Emperor Justinian I.

The long war (535-554) with Justinian not only badly destroyed social

life in Italy, it exhausted the Byzantine Empire ... leaving the

Byzantines susceptible to conquest, first by the Persians and then by

the Arabs. And the Visigoths themselves were also thus unable to

ward off a new Germanic tribe anxious to take control of their lands:

the Lombards.

The Alemanni

Just to the north of the Alps, in the upper reaches of the Rhine River

(today's Alsace and northern Switzerland) was another Germanic tribal

confederation ... a people who suffered terribly from the cruelty of

the Emperor Caracalla who turned them into dedicated enemies of the

Romans. In the mid-200s they made raids into Roman Gaul and into

Italy north of the Po River. Finally they were defeated in battle

in 268 and driven back across the Rhine.

But they would continue to trouble Rome, fighting – but defeated – at

Argentoratum (Strasbourg) in 357 and then again in 366, after having

crossed the frozen Rhine. They remained intact as a people ...

and finally in the confusion caused by Alaric at the beginning of the

400s they were able to move successfully across the Rhine to settle the

area of Alsace. In 451 the Alemanni would be part of Attila's

alliance that was defeated by Aëtius. But they again would still

hold their position around the upper Rhineland region.

The Burgundians

The Burgundians (who might have been a sub-group of the Vandals) moved

west – possibly from the Baltic coast of today's Poland – towards the

Rhine Valley, initially locating themselves between the Franks to the

north and the Alemanni to the South. They would serve as

foederati in the Roman legions ... although Roman General Aëtius had to

call on his Hun allies to break their growing power ... killing the

majority of the Burgundian tribe in the process. But Aëtius then

resettled the remnant group ... who then became Roman allies again

(against Attila).

Then with the total collapse of Roman authority in Gaul, the

Burgundians expanded their reach south to the area that today

constitutes Southeastern France. But eventually they would be

absorbed into the Frankish kingdom (when not upon occasion also quite

independent in operation!).

The Saxons

There is some uncertainty about the name "Saxon" as to whether it

refers to a particular ethnic or tribal subgroup of the Germanic

peoples ... or whether it was simply a term applied to a group of

Germans that as fishermen and sailors (ultimately "pirates") raided

ships operating in the North Sea.

At some point "Saxons" (coming from the Baltic shores of southern

Denmark?) drove the Franks south of the Rhine basin and took control of

the coastal region along the North Sea coast of the European

continent. They are closely associated with other Germanic

peoples of the region, the Frisians, the Angles and the Jutes. It

is indeed from this broader association that they produced the label

"Anglo-Saxon."

The beginning of the Anglo-Saxon migration to Britain

Eventually this group crossed the North Sea to settle in the Roman province of Britain. Tradition2

states that Saxons led by Hengest and Horsa were invited in the

mid-400s by British (Celtic) King Vortigern to help ward off the

attacks of the Picts and Gaels ... attacks that had begun after the

withdrawal of the Roman Legions in 410 (to help fight Alaric).

However – according to some accounts – following their victory over the

Picts, a dispute arose with Vortigern about payment. They thus

felt free to take land for themselves – and thus established the

kingdom of Kent. Others hold the opinion tat the Saxons, simply

seeing how defenseless the Britons were, sent word back to their

kinsmen on the continent to come and help them take possession of the

land. In any case a mass migration of Saxons now got underway,

filling the ranks of a growing Saxon presence in Britain.

Establishing Saxon England

The advance of the Germanic Saxons against the Celtic British was

steady ... until the Battle of Mons Badonicus (c. 500) when the British3

halted the Saxon progress ... at least for a while. By the end of

the 500s the Saxon expansion resumed (aided by in-fighting among

Celts), the Saxons – particularly those under King Aetheberht and

starting from their base in Kent – drove the Celtic population further

West into Wales and Cornwall ... as well as across the water to

Brittany in France. At around this time other Saxon kings were

establishing their rule in the regions of Sussex, Wessex, Essex, East

Anglia, Mercia and Northumberland.

But they would end up fighting each other as often as they would be taking on the Celtic kings and their people.

The Saxon invasion of Britain – late 400s?

The Lombards

North German Lombards – joined by a variety of other German tribes –

migrated south at the beginning of the 500s and settled along the upper

Danube. Then in 568 under a very capable king, Alboin, they

migrated west down into a very exhausted northern Italy, greatly

weakened by the Ostrogoth-Byzantine war (the "Gothic War").

Sadly, the Roman army found itself totally unable to offer any kind of

effective defense against so large a German enemy (568-569) ... there

being perhaps as many as half a million Germans on the move.

Consequently, city after city quickly fell to them. By 580 they

occupied nearly all of northern and most of central and southern

Italy. The great Roman cities of Rome and Ravenna held out – but

little else of strategic value in Italy.

A Lombard Kingdom was immediately established ... on the basis of a

number of Lombard duchies located here and there around the Italian

peninsula ... shared with the Byzantines, with Byzantine Italian

holdings also scattered here and there – which included the city of

Rome itself.

But it was a very loose arrangement, as the Lombard dukes were careful

to protect their relative independence ... and thus Lombard kingship

was normally a very unstable political office. Also the

independence of the Popes at Rome weakened the position of the Lombard

king. And the division among the Lombards between those trying to

hold onto their traditional German gods and culture and those who had

become Christian and Latinized constantly roiled Lombard politics.

The Lombards would remain in control of Italy for the next two

centuries – although, divided into 36 duchies, the Lombards lacked the

political unity that Italy sorely needed. But this division

served to keep the city of Rome independent – and still dominant in

religious matters and influential in political affairs throughout the

West.

1The

Sarmatians were a people of northern Iranian descent that had earlier

migrated westward as far as an area reaching from Southern Poland to

Eastern Romania.

2Derived from Ecclesiastical History of the English People, composed by the English monk Bede around the year 730.

3This resistance

was most likely the basis for the medieval development of the legends

concerning King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

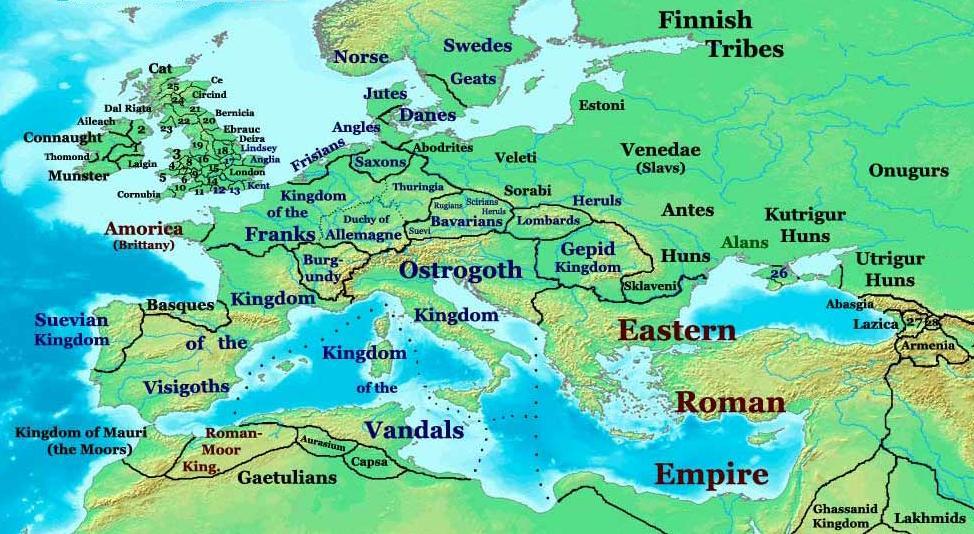

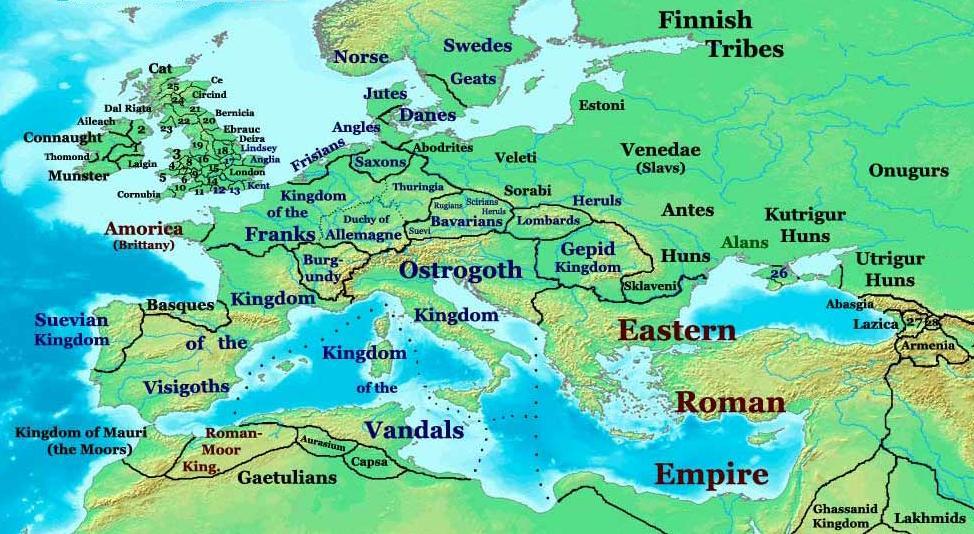

Europe and the Middle East

around 500

Wikipedia

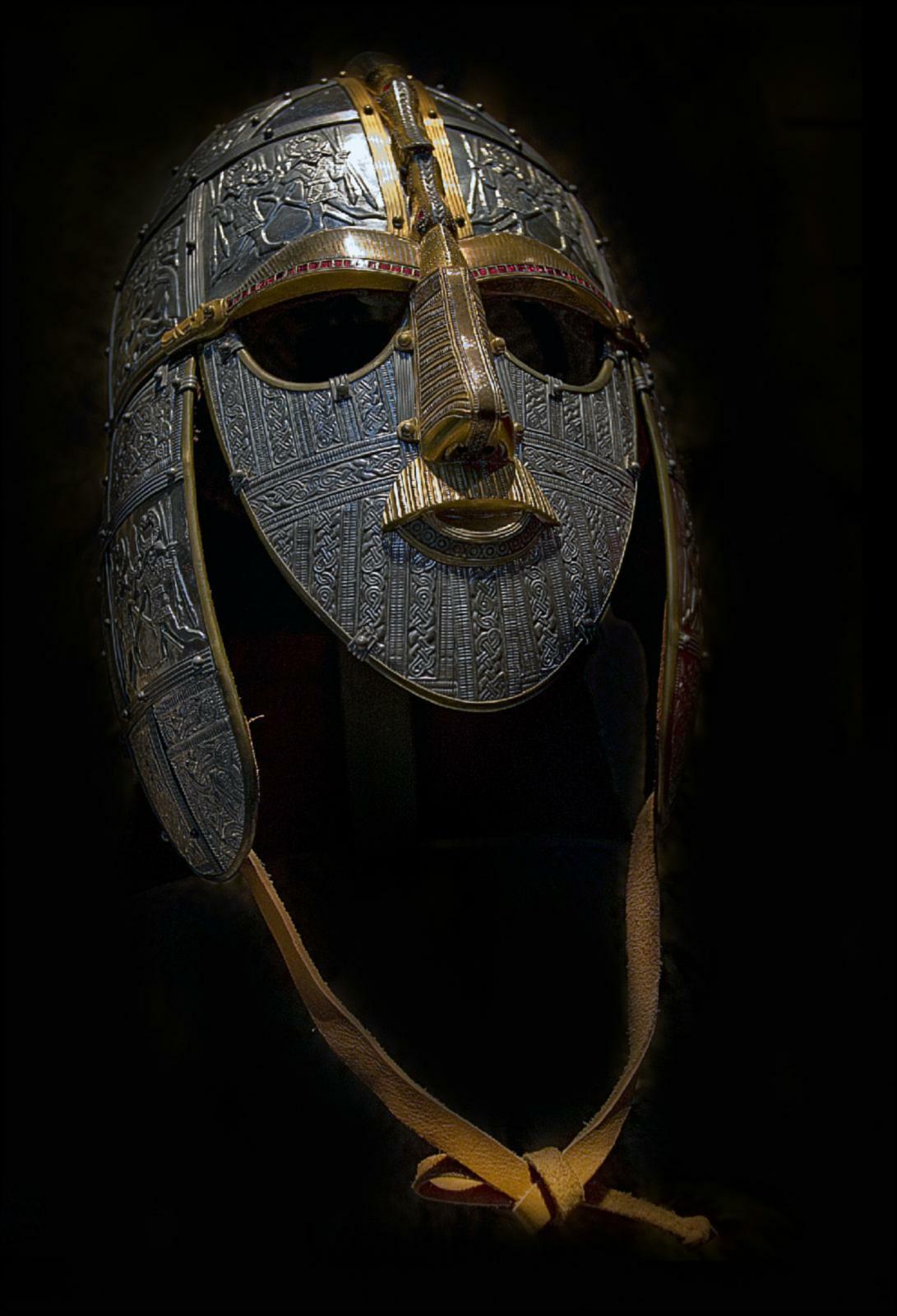

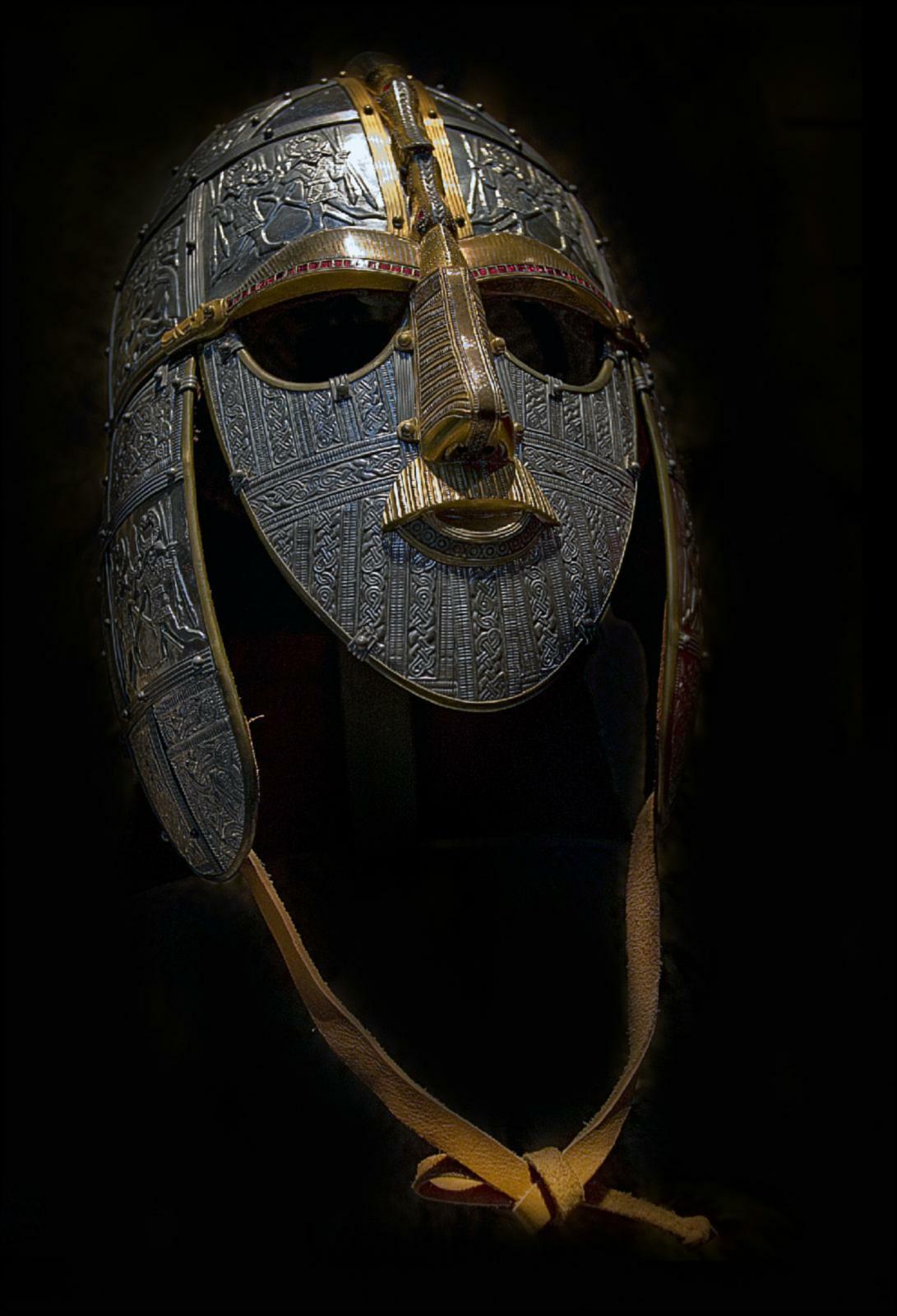

Replica of the helmet found

at Sutton Hoo (England), in the burial of

an Anglo-Saxon leader, probably

a king, about 620 in the Early Middle Ages

SOME OF THE GERMANIC "GREATS" |

|

Leadership problems

The Romans had always been fairly accommodating to non-Romans whom they

had come to have some degree of ascendancy over. It was natural

for the Romans during the 200s and 300s to suppose that they could

continue this policy with the Germans. Indeed, they found the

Germans to be excellent fighters willing to serve the interests of the

Roman imperial armies.

But what began to change this relationship was not so much a change in

the Germans themselves as it was a change in the talents of the Roman

leaders. The personal character of Roman emperors had been

variable, bad mixed in with the good. But it seems that Rome was

increasingly experiencing a long run of incompetent emperors.

Everyone sensed this.

And this in turn brought forward a number of bold leaders willing to

challenge Roman authority. We have already met Alaric and Attila

as excellent examples. But there were others.

Gaiseric (or Genseric) and the Vandal Kingdom (r. 428-477)

The Wendels or Vandals were a small tribe allied with the Alans – who

in the early years of the 400s crossed into Gaul. But the resistance of

the Franks was so intense that they moved on through Gaul and crossed

the Pyrenees into northwestern Spain. Conflicts with the Suebi

(who had also recently migrated to the area) forced the Vandals into

southern Spain. Here also troubles with the Visigoths – an even

stronger German tribe which had moved to the area – brought the death

in battle in 428 of their king Gunderic. At this point his half

brother Gaiseric (born c. 390) was named king by the Vandals and Alans.

Gaiseric had already made the decision that the Vandals had to leave

Spain – even preparing a fleet prior to the events which made him

king. Thus in around 428 or 429, Gaiseric led approximately

80,000 Wendels or Vandals from Spain to Carthage in North Africa where

he ravaged Roman power there (Augustine died during the long Vandal

siege of Hippo Regius 430 431 which subsequently became Gaiseric's

capital). Eight years later he forced Carthage to submit – and

made it his new capital. He had captured the large fleet of

Carthage – and added it to his own, giving himself a very large navy.

His intentions were to challenge Rome for control of the Western

Mediterranean. He forced Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica into

submission – and then for the next several decades raided Roman

shipping at will. Finally in 442 Gaiseric secured from

Valentinian III recognition of his kingdom as independent (not under

Roman authority) – and some semblance of peace resulted.

When in 455 Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III was murdered,

Gaiseric took the position that the peace treaty he had made with

Valentinian was no longer valid. He sent his fleet off to Rome –

which was totally unprepared to deal with the Vandal attackers.

It was only three years since Attila had ravaged Italy and nearly

assaulted Rome (Pope Leo I had persuaded Attila to leave Rome

alone). Rome was defenseless – and for two weeks the Vandals

"vandalized" Rome – although with Pope Leo's intervention (again), Rome

was spared from arson and slaughter of the population.

In 468 the Romans sent a huge fleet to attempt to crush the Vandals and

end their control (or piracy) in the Mediterranean. But instead

the Roman fleet was destroyed by Gaiseric's navy. This merely

emboldened Gaiseric – who subsequently invaded Greece. But this time

his victorious streak failed him and he had to retreat back to Carthage

(but taking 500 hostages whom he hacked to pieces and threw overboard

on the trip home). Finally in 474 he made peace with the

Byzantine Empire. Three years later he died at Carthage.

Euric and the Visigothic Kingdom (r. 466-484)

Although the Visigoths had been critical support of Aëtius in his

battle with Attila, the battle had cost the Visigoths the loss of their

king, Theodoric. His son Theodoric II took the throne in 453 by

killing his older brother, Thorismound. In 458 Theodoric lost to

the Roman Emperor Majorian much of the Visigothic territory in Spain

and in Septimania (today's French Mediterranean coastal region) but was

able to regain the territory with Majorian's assassination in

461. But then in 466 Theodoric himself was assassinated ... by

his own younger brother Euric.

As king, Euric was successful in forcing other Visigothic chieftains

under his direct rule ... and establishing the Visigothic Kingdom as

fully independent of Roman authority. To the south from his

capital at Toulouse, he drove the Suevi into the northwest corner of

the Spanish peninsula thus taking over most all of Hispania. And

he extended Visigothic control north into Gaul ... all the way up to

the borders of the Frankish kingdom in the north of Gaul. This

marked the height of the Visigothic kingdom ... for by the time of his

death in 484 he and Odoacer had come to hold much of Roman Western

Europe between the two of them. But his death would also

mark the beginning of Visigothic decline ... at the hands of the

expansive Franks.

Childeric and the Frankish Kingdom (r. 458-481)

In the continuing chaos which followed the sack of Rome by the Visigoth

leader Alaric in 410 and then the sacking again of Rome in 455 by the

Vandals, the Franks under their king Childeric I (reigned 458-481) – in

cooperation with the Gallo-Roman forces of Aegidius – were able in 463

first to fight off the Visigoths under Odoacer and then some

Saxons along the Loire River valley. Subsequently Childeric

allied with Odoacer in fighting off invading Alamanni attempting to

invade Italy. Consequently, Childeric succeeded in stretching

Salian Frank rule from the Lower Rhine in the North to the Somme River

in the South (a region eventually to be known as Austrasia).

Odoacer ... the last Roman patrician (r. 476-493)

Odoacer was born (434) along the Danube River among the Scirii

tribesmen who had just invaded the area a few years earlier. He

entered service in the Roman army in around his thirtieth year and rose

quickly within its ranks as a leader of a band of foederati.

In 475 the Western Emperor Nepos was driven from his throne by the

military commander Orestes who had built his support among thousands of

foederati with promises of good land in Italy. Orestes's son,

Romulus, was placed on the imperial throne. But Orestes did not

deliver on his promise of land. The following year Odoacer led a

group of disgruntled foederati in revolt. They captured the

imperial capital at Ravenna and forced Romulus to abdicate.

Odoacer refused the imperial title, declaring himself simply patrician

(military commander) in the "West" (at this point little more than

Italy was still under Roman control in the West).

Nepos appealed to the Eastern Emperor Zeno to restore him to the

imperial throne. But there was initially no enthusiasm from Zeno

in this matter – or from the Roman Senate which, pleased by the

stability brought to Italy by Odoacer, asked Zeno to recognize Odoacer

as a patrician entrusted with care of the "diocese" of Italy. He

created a strong Italian German army and, upon Nepos's death, brought

Dalmatia (opposite Italy) under his control. He then drove the

Vandals from Sicily – and formed an alliance with the Goths and Franks

to hold back the expansionist German Burgundians, Alemanni and Saxons

in the north.

But eventually Odoacer's power grew to the point that it embarrassed

Zeno, who then decided to deflect the growing power of the Ostrogothic

king, Theodoric, by directing him into action against Odoacer –

promising him the rule of Italy should he defeat Odoacer (a policy

designed by Zeno to move the Ostrogoths away from the Eastern Empire

and get rid of the growing power of Odoacer at the same time). In

488 Theodoric and his Ostrogoths invaded Italy and defeated Odoacer in

a series of battles. Odoacer took refuge in Ravenna where he

remained impregnable – but also hungry. When disease broke out

among the besieging Goths, a peace (493) was declared between Odoacer

and Theodoric. But Theodoric personally murdered Odoacer at a

supposedly friendly banquet the following month.

The net historical effect of Odoacer was to end for all times the

fading tradition of Roman rule in Italy and the West. The West

was no longer Roman – but instead, German (Visigoth, Frank, Alemanni,

Burgundian, Saxon, Vandal, etc.).

The Ostrogothic King Theodoric "the Great" (r. 475-526)

Theodoric was born (454) in Pannonia (today's Western Hungary), son of

Theudemir, one of the kings of the Ostrogoths (East Goths). He

was sent as a Gothic "guarantee" (hostage) of peace to the Byzantine

court in Constantinople where he lived for ten years. Upon his

return to Pannonia, he began the conquest of neighboring kings

including Macedonia. This gained him recognition as a foederati,

titled holder of Roman territory in the Balkans to which his

Ostrogothic kinsmen were entitled to settle.

This Roman privilege was intended to pacify the barbaric tribesmen,

even making them allies of the Roman imperium. But Theodoric

preferred instead to use his power to consolidate his people's hold

over his neighbors. He also attacked Roman lands at will – though

not with any definitive success.

Theodoric's murder of Odoacer meant Ostrogothic

dominion over Italy. But this proved to be a quite lasting time of peace and

stability for Italy – the first in a long time. Bureaucratic

corruption, brigandage and other social diseases were brought under

control. The Italian economy began to revive and urban life

underwent restoration. Indeed, Italy became a food exporter under

the stimulus of such peace.

But toward the end of his reign some unwise political or diplomatic

decisions began to undermine his legacy. As an Arian Christian he

had generally been tolerant, even supportive, of the Catholic

Christianity of the Italians. Yet when the Eastern Emperor

Justinian began to take action to suppress Arian Christianity in

Byzantine lands, Theodoric began to be cruelly reactive to the Catholic

Church in his own Italian lands. Unfortunately, he is also

remembered for his execution in his last years of the philosopher

Boethius.4

The Frankish King Clovis (Chlodwig) (r. 465 511)

Childeric's son Clovis I, who came to power in 481, stretched Salian

Frank rule even further than had his father, eliminating the power (and

lives) of other Frankish kings in Gaul (including his own

brothers). In 486 he defeated a Roman army under Syagrius at

Soissons, thus establishing unquestioned Frankish ascendancy over

northern Gaul. He then allied with the Ostrogoth King Theodoric

and went on to defeat the Alamanni in 496. He then secured Paris

as his own capital.

The Catholic archbishop of Reims, Remigius, was quick to recognize

Clovis as a possible solution to the anarchy that ruled over the Gallo

Roman world. Also, his Burgundian princess wife, Clotilda,

had been working to bring him from paganism to Catholic Christianity

(perhaps he himself had been considering Unitarian Christianity.

In any case, he finally decided to cooperate with the Roman church by

converting and being baptized into Trinitarian or Catholic Christianity

in 496 (or was it 507? ... accounts vary). This made him the

first of the major Germanic leaders to move to the Catholic or

Trinitarian Christian confession. His people then

followed him into a similar baptism. This gave the Salian Franks

special standing with the Catholic Church.

4Boethius

(c. 480-524) was a Roman senator and scholar who spent much of his time

translating the Greek classics into Latin … as well as demonstrate the

connection between Christianity and the works of Plato and

Aristotle. In fact, it was Boethius who was most responsible for

having the works of Aristotle preserved for later (Renaissance) study.

The Baptism of Clovis

by St. Remy - 496

Cathedral of Rheims

Meanwhile, in 500 he tried – but failed – to acquire the Burgundian

kingdom ... although he did acquire all Swabia two years

later. He then directed his attentions South to Aquitaine,

in 507 taking this huge region from the Arian Visigoths under the weak

Alaric II.

In that same year the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius I

decided to assign Clovis the old Roman title of Consul ... and then in

511 the Byzantine Emperor appointed Clovis to preside over the

Christian Council of Orleans – adding further legitimacy to his rule.

With this the Merovingian dynasty of Frankish kings was established –

to rule Frankish northern Europe5 ("Francia" … the land of the Franks)

until the dynasty was put aside by the Carolingians in 751.

The Merovingian follow-up

However, in accordance with Salian tradition, at his death in that same

year (511) Clovis's lands were divided among his sons into four smaller

kingdoms: Paris (Childebert), Orleans (Chlodomer), Soissons

(Chlotar) and Metz (Theuderic). Not surprisingly, much energy was

spent by Clovis's sons fighting each other. But they also

expanded the reach of their realms elsewhere, especially Childebert,

fighting Visigoths in Spain and Burgundians (in today's southeastern

France). But Childebert had no sons, and ultimately the youngest

of Clovis's sons, Chlothar was able to reunite Francia briefly simply

by surviving his brothers. But once again, Francia was split into

separate kingdoms among Chlotar's sons when he died in 561.

Chlotar's son Chilperic received the Frankish heartland of Neustria

(today's northwestern France) and attempted to conquer the rest of

Francia, in particular to the East against his brother Sigebert, King

of Austrasia (Eastern France and Western Germany). Family feuds

grew bitter, involving also the wives, Fredegund (Chilperic) and

Brunhilda (Sigebert). Fredegund eventually killed Sigebert (575)

and an assassin killed Chilperic (584).

Eventually feuding among the Merovingian kings would weaken the power

of the king ... and instead strengthen the powers of the local barons

and the church. In 614 Neustrian King Chlothar II – who as King

of the Franks (son of Chilperic and Fredegund) presumably ruled over

the entire Merovingian domain – was forced to recognize (Edict of

Paris) the increased powers of the local nobility.

Then in 617, hoping to rebuild royal power, Chlothar created the

position of "Mayor of the Palace" – something of a prime minister or

chancellor – given wide powers to administer the realm.

Finally Chlotar was able to unite most of Francia, (having Brunhilda

executed in 613 and thus laying claim to Austrasia) ... though spinning

off Austrasia to his young son, Dagobert in 623!

And so it went!

Merovingian government ... and the foundations of feudalism

Germanic or tribal Europe was not equipped to govern its lands and

people in the manner that the Romans had ... through a huge

bureaucratic network supported by a fairly efficient tax system.

Neither administrative expertise nor money were available to administer

the lands ruled by the Merovingian kings. So instead, key

personal supporters of the kings – family members or trusted

individuals – were assigned portions of the king's domain as "counts"

and "dukes" (from the Roman comites and duces) ... to administer the

law and protect the land in the name of the kings that appointed them.

The all-powerful mayors of the palace

But the kings would also keep some section of the larger domain as

their own personal property, the royal demesne (domain), for their own

material support. To help oversee the daily administration of the

royal domain, the kings would appoint personal assistants, "mayors of

the palace." Over time, the position of mayor of the palace grew

increasingly important, especially as Merovingian kings came to the

throne quite young and died after fairly short reigns ... thus leaving

the oversight of not only the royal domains but the entire kingdoms to

the mayors of the palace. In time dynasties would form themselves

around this key office ... more powerful in fact than the kings

themselves as the Merovingian kings increasingly slipped into the

position of being mere ceremonial figures – even rois fainéantes (weak kings).

The early rise of the Carolingians: Pepin of Herstal

In 687, Pepin II of Herstal, "mayor of the palace" in Austrasia since

680, conquered the other Frankish kingdoms of Neustria and Burgundy ...

and then awarded himself the new title "Duke and Prince of the Franks" (dux et princeps Francorum)

... declaring his own sovereign powers as Frankish leader. To

prove his point, he then went on to conquer the neighboring kingdoms of

Alemannia (today's Southwestern Germany), Frisia (Northern Netherlands)

and Franconia (Southcentral Germany).

But his conquest was intended to be as much cultural as political ...

for also as "defender of the faith" he sponsored evangelism among the

Germans to bring them to Catholic Christianity.

Then he secured the right to have his own family succeed him in office

... thereby laying the foundations for the Carolingian dynasty.

But (as was typical of the Germans at that time) he had more than one

wife ... and his first wife Plectrude (whose sons died before the

elderly Pepin finally died in 714) got Pepin to designate his grandson

Theudoald as his heir ... in opposition to his second wife Alpaida, who

had two surviving sons by him, but one in particular, Charles.

Thus when Pepin died a rather well expected civil war broke out among

Pepin's offspring.

Out of this, Charles "Martel" (the "Hammer") would emerge victorious

... and open France to a new greatness (more about this in the next

chapter).

The Anglo-Saxon World

Æthelberht of Kent (r. c. 565-6166).

Not much is known about how the Anglo-Saxon world developed – until

Æthelberht took the Saxon crown upon his father's death (in 560 or

580?). The Christian monk Bede in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People

(c. 731) mentions Æthelberht as the third of the Saxon kings to rule

over several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms – from his base in Southeastern

England (Kent). Bede also mentions his conversion to

(Trinitarian) Christianity – thanks to the mission of the monk

Augustine, sent in 597 to England by Pope Gregory to bring the area to

Christ.7

Æthelberht and Augustine would together establish a church at

Canterbury ... which eventually would become the seat of the English

Archbishops – and the starting point of bringing the Saxons to

Christianity.

Edwin of Northumbria (r. c. 616-632). Way to the North were the kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia8

– ruled by Edwin, son of a Deira king … with his base at the town of

York. Edwin managed – with the help of East Anglia's king Rædwald

– to come back from early exile and take command of the region – and be

its first Christian king.9

He would go on to conquer many of the surrounding Saxon kingdoms

(Mercia, Wessex, Anglesey, for instance) … but ultimately would die in

one of his many battles. After that, older Saxon paganism seemed

to reassert itself in the north.

5The

dynastic name is derived from a semi-mythical Salian Frank king

Merovech ... who in the mid-400s ruled what is today's Belgium and

northern France.

6These

dates are highly debated as Bede's Ecclesiastical History and the

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (late 800s) give at least a 20-year variance in

dating Æthelberht's birth, marriage, and reign.

7But

he may have already been something of a Christian … thanks to his

Frankish wife, princess Bertha – who apparently had a bishop accompany

her to England upon her marriage to Æthelberht.

8Probably

originally British (Celtic) kingdoms, conquered by the Saxons.

They would later (mid-600s) be joined as the kingdom of Northumbria …

that is, England north of the Humber River.

9This

seemingly occurred when Edwin married Æthelburh, the sister of Eadbald

of Kent … under the provision that just as Eadbald's father Æthelberht

had become Christian upon marring Bertha, so also Edwin should do the

same in marrying Æthelburh.

Go on to the next section: The Roman Church Survives in the West

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

The invading / migrating German tribes (cl 375-568)

The invading / migrating German tribes (cl 375-568)